Abstract

Modeling the response of material and chemical systems to electric fields remains a longstanding challenge. Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) offer an efficient and scalable alternative to quantum mechanical methods, but do not by themselves incorporate electrical response. Here, we show that polarization and Born effective charge (BEC) tensors can be directly extracted from long-range MLIPs within the Latent Ewald Summation (LES) framework, solely by learning from energy and force data. Using this approach, we predict the infrared spectra of bulk water under zero or finite external electric fields, ionic conductivities of high-pressure superionic ice, and the phase transition and hysteresis in ferroelectric PbTiO3 perovskite. This work thus extends the capability of MLIPs to predict electrical response –without training on charges or polarization or BECs– and enables accurate modeling of electric-field-driven processes in diverse systems at scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The polarization P of a system underlies many electrical response properties including capacitance, dielectric constant, ferroelectricity, piezoelectricity, ionic conductivity, and infrared (IR) spectra. The Born effective charge (BEC) tensor Z* quantifies the variation in P due to an atomic displacement at position ri of atom i1:

where α and β label Cartesian directions. The second part of Eq. (1) links the electrostatic force \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{i}\) on atom i resulting from an external electric field \({\boldsymbol{\mathscr{E}}}^{0}\) to the system.

Modeling electrical response properties has long been a challenge. The Berry phase definition of the polarization2,3 of periodic insulators can be obtained from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Density-functional perturbation theory (DFPT)4 or the finite field method5 can be used to compute BECs and other derivatives of the polarization. However, the computational costs associated with such ab initio methods limit their applications to large systems or long timescales. On the other hand, fixed-charge or polarizable empirical force fields are cheap but may lack quantitative accuracy or transferability6,7.

Standard machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs)8,9, which learn surrogate potential energy surfaces from quantum mechanical reference calculations, are typically short-ranged and do not explicitly consider electrostatics. Several approaches have been developed to incorporate long-range interactions, such as learning DFT-derived partial charges10,11,12,13 or maximally localized Wannier centers14,15, or employing long-range descriptors16,17 or long-range message-passing18. Latent Ewald Summation (LES)19,20 is a recent method that learns a long-range energy contribution Elr by fitting to the total potential energy E and atomic forces F of configurations:

where k is the reciprocal wave vector and V is the cell volume. The structure factor S(k) given by

and the LES charges \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{les}}}\) are predicted using a neural network based on local invariant features Bi of atom i. LES can be combined with any short-ranged MLIP architecture, such as descriptor-based21,22,23 or message-passing neural networks24,25.

However, a natural inclusion of electric response directly within the MLIP frameworks is missing. Currently, P and BEC have to be learned separately as tensorial properties26,27, e.g., directly predicting BEC tensors28,29 or local contribution to the dipole moment of a molecule26,27,30 based on atomic environments, the charge response kernel31, or as the response of the potential energy to an external field32,33,34. These advances enable simulations under an electric field and the extraction of electrical response properties. Conceptually, however, such approaches are in contrast with the electronic structure picture of matter: nuclear positions and electronic wavefunctions fully determine how the system will interact with an electric field.

Here, we show that polarization and BEC tensors can be naturally derived from long-range MLIPs within the LES framework. This enables accurate predictions of electrical response properties, such as IR spectra and conductivity, solely by learning from energies and forces. Importantly, it is straightforward to add an external electric field to MLIP-driven molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling the exploration of electric-field-driven phenomena in various materials and molecules. We demonstrate this method on a range of complex bulk systems, including molecular liquids, ionic liquids, superionic crystals, and ferroelectric materials.

Results

Theory

Building on the pioneering Molecular Dynamics in Electronic Continuum (MDEC) model6,7,35,36, the Coulomb interactions between the “free charges” of atoms are explicitly considered, while the rapidly responding background electrons are treated as a dielectric medium. The electrostatic field produced by the free atomic charge qi of atom i can then be expressed as

and the resultant electric force between two atoms is given by:

where ε0 represents the vacuum permittivity, and ε∞ is the high-frequency relative permittivity (also known as the static or electronic dielectric constant). For each bulk system under a given thermodynamic condition, ε∞ is a constant value that can be determined experimentally (e.g., from the square of the optical refractive index) or calculated from a snapshot using DFPT with frozen nuclei37. Moreover, ε∞ or refractive index of non-plasmonic materials is mostly related to the density, and typically insensitive on the pressure or temperature.

We interpret the LES charges \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{les}}}\) as scaled charges, \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{les}}}={q}_{i}/\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{\infty }}\), acting both as the sources and the receivers of the electric field:

In the LES algorithm, \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{les}}}\) are optimized to effectively describe the long-range component of the total potential energy and atomic forces. For modeling the energetics and dynamics of a system under no external field, these LES charges provide a self-contained description of electrostatic interactions, with no further adjustment needed. To model electrical response, however, the LES charges can be unscaled to recover the atomic charges qi.

The polarization (dipole moment) of a finite system such as a gas-phase molecule is

and the BEC Z* can be obtained by taking its derivative with respect to r:

As shown in the second part of Eq. (8), the BEC tensor \({Z}_{i}^{* }\) comes from two contributions: the charge qi, and the dependence of the charges on atomic positions.

For modeling either crystalline or disordered bulk systems, it is almost mandatory to apply periodic boundary (PBC) conditions. Importantly, the value of P cannot be uniquely defined for systems with PBC, according to the modern theory of polarization2,3. To circumvent such ambiguity, we propose a generalized formulation of polarization P(k) under PBC:

where Pα(k) is the polarization along the α direction, k = 2π/Lα, and Lα is the length of a periodic cubic cell, while the extension to triclinic cells is straightforward. Eq. (9) has close connection with existing approaches in related fields: the response of the system to adding an electric field of finite wave vectors in the classic electrostatics picture; the Berry phase definition of the polarization in electron structure methods2,3, the exploitation of periodic coordinates or twisted boundary conditions in Quantum Monte Carlo methods38. The Pα(k) is complex valued, and has no direct correspondence with multivalued DFT polarization2. At the limit of k → 0, P(k) becomes the finite-system expression in Eq. (7). The BEC tensor Z* of atom i can then be evaluated as

The prediction of BEC enables the calculation of several electrical response properties. For instance, the current of the polarization of the system can be obtained as \({\bf{J}}(t)={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{Z}_{i}^{* }(t)\cdot {{\bf{v}}}_{i}(t)\). The current-current autocorrelation function encodes the ionic electrical conductivity σ via the Green-Kubo formula,

and the IR spectra via Fourier transform,

Moreover, once BEC are computed using Eq. (10), one can apply a real-valued constant electric field \({\boldsymbol{\mathscr{E}}}^{0}\) to the system by adding the electrostatic force \({\boldsymbol{\mathscr{F}}}_{i}\) on each atom using the second part of Eq. (1) for the linear response regime, thus enabling constant-electric-field simulations under PBC.

Example: Water

The theoretical prediction for the IR spectrum of water is a classic problem but still not fully resolved, and more so with the presence of external electric fields39. We used the Cartesian Atomic Cluster Expansion (CACE)40 potential as the short-ranged MLIP and LES19,20 as the long-range part, and thereafter refer to this combination as CACE-LR. The RPBE-D3 bulk water dataset from ref. 28 contains energies and forces of 654 configurations (90% train/ 10% test split) each of 64 water molecules. Even though we used a compact CACE model with a cutoff of 4.5 Å and no message passing, the test root mean square errors (RMSEs) of energy and forces (0.25 meV/atom and 21 meV/ Å) are smaller compared to the errors in ref. 28 (0.8 meV/atom and 60 meV/ Å) and ref. 41 (0.3 meV/atom and 27 meV/ Å) that uses converged DFT setting and more kernels in MLIP fitting.

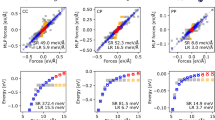

Figure 1a compares the BEC tensor elements predicted by LES and calculated by the reference DFT for 100 water configurations at experimental density and room temperature28. We used the high-frequency permittivity ε∞ = 1.83, which was computed from DFPT calculations28. Only one snapshot is needed to estimate ε∞ here, as the standard deviation of σ(ε∞) = 0.008 from different snapshots at the same thermodynamic condition is negligible. Alternatively, one could obtain ε∞ based on the experimental refractive index of water.

a compares the Born effective charge tensors (Z*) computed from DFT and predicted using the LES method. The CACE-LR was trained on the energies and forces of the RPBE-D3 bulk water dataset28. The main panels compare the diagonal elements of BEC (\({Z}_{\alpha \alpha }^{* }\)), and the insets show the off-diagonal elements (\({Z}_{\alpha \beta }^{* }\) with α ≠ β). The left panel (no PBC) corresponds to the LES BECs calculated assuming no periodic boundary condition using Eq. (8), and the right panel (PBC) shows PBC obtained using the generalized polarization form in Eqs. (9) and (10). b shows the infrared (IR) absorption spectra of bulk liquid water in the absence of an external field (black line) and under varying external field intensities (colored lines) as indicated in the legend. The experimental IR spectrum in the absence of an external field42 (gray shading) is included for reference.

If neglecting PBC and naively using Eq. (8), the predicted BEC exhibited significant discrepancies from the DFT reference values, particularly for atoms near the edge of the simulation cell. In contrast, by properly accounting for PBC using Eq. (9) and Eq. (10), the LES BECs agree well with DFT for both diagonal and off-diagonal components. This shows that it is necessary to resolve the ambiguity of P for periodic systems using a scheme like Eq. (9). Compared with the reference model that directly learns BEC tensors (training RMSE 32 me from ref. 28), the LES model yields a test RMSE of 51 me on the same dataset, demonstrating comparable accuracy without explicitly training on the tensorial quantities.

We performed MLIP-driven NVT simulations of bulk water (0.25 fs timestep and 200,000 MD steps) under the Nosé-Hoover thermostat, at 300 K and experimental density, and extracted the IR spectra using Eq. (12) based on the LES BEC tensors. As shown in Fig. 1b (black curve), not only are the predicted shapes and positions of the intramolecular vibrational modes such as OH stretching band (≈ 3400 cm−1) and bending (≈ 1640 cm−1) mode band in excellent agreement with experiment42, but also the intermolecular low-frequency libration mode band position43 (≈ 650 cm−1) and the hydrogen-bond translational stretching mode44 (≈ 200 cm−1) are well captured. Notably, it is necessary to use the time-dependent BEC tensors to compute the IR: if using the fixed nominal charges of qH = + 1 for hydrogen and qO = − 2 for oxygen (see Fig. 6 in Methods), the shape of the predicted IR is much worse, and the hydrogen-bond translational stretching band is completely absent.

We then performed NVT MD simulations for bulk water under static constant external fields \({\boldsymbol{\mathscr{E}}}^{0}\) (0.05 V/ Å, 0.1 V/ Å, or 0.15 V/ Å) along the z-direction, by adding electrostatic forces on all atoms according to the second part of Eq. (1). As shown in Fig. 1b (colored curves), at higher electric field intensities, the intermolecular librational band (≈ 650 cm−1) blue shifts and the intramolecular OH stretching band (≈ 3400 cm−1) red shifts. These trends are consistent with previous studies using DFT molecular dynamics39,45. The red-shift of the OH stretching band is generally associated with stronger hydrogen bonding46 and with more ice-like structures47. The blue shift of the low-frequency libration mode can be attributed to the enhanced restrictions on the rotational motion of water molecules imposed by the H-bonds39. Overall, these shifts under the electric field agree well with the predictions using previous approaches based on the direct learning of BEC tensors or dipoles27,34, suggesting that our approach, that only learns from energy and forces, can achieve similarly quantitative predictions of IR spectra.

Example: Superionic water

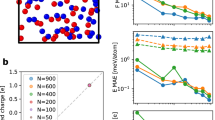

This example aims to illustrate the capability of our BEC inference method for ionic and superionic systems, and its generalizability across a wide range of conditions. Water at megabar pressures and thousands of Kelvins exhibits diverse structural and dynamical behaviors: ionic water with partially dissociated hydrogen atoms (Fig. 2a), the face-centred cubic (FCC) superionic phase (ice XVIII) with liquid-like hydrogen atoms while oxygen atoms remain on the crystalline lattice48,49 (Fig. 2b), and ice X with a body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice of oxygen atoms50 (Fig. 2c).

a corresponds to partially ionic liquid water, b shows face-centred cubic (FCC) superionic phase (ice XVIII), and c is ice X. The oxygen-hydrogen bonds are drawn with a cutoff of 1.1 Å. d compares the BEC tensors (Z*) computed from DFT and predicted using the LES method, for 100 configurations of each phase at the specified condition. The CACE-LR was trained based on the energies and forces from the superionic water dataset49. The main panels compare the diagonal elements of BEC (\({Z}_{\alpha \alpha }^{* }\)), and the insets show the off-diagonal elements (\({Z}_{\alpha \beta }^{* }\) with α ≠ β). e illustrates the correlation between the mean diagonal values of Z* of all hydrogen atoms, and the distances to their nearest two oxygen atoms.

We trained the CACE-LR model using 5000 configurations (90% train/ 10% test split), randomly selected out of the 17,516 structures in the original MLIP training set that was compiled for predicting the phase diagram of superionic water spanning a wide range of thermodynamic conditions up to thousands of kelvin and megabar pressures49. Despite the smaller training set and a relatively light-weight architecture choice of the CACE-LR model, the test errors on energies and forces are halved compared to the original study: 7 meV/atom in energy RMSE and 327 meV/ Å in force RMSE, compared to 14 meV/atom and 740 meV/ Å of the original MLIP49, respectively.

Figure 2b shows that the predicted LES BEC tensors agree well with the ground-truth DFT values for three distinct phases (illustrated in Fig. 2a–c) under different thermodynamic conditions. We computed the high-frequency relative permittivity from DFPT calculations on a single snapshot at each of the three conditions: ε∞ = 3.1 at 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K, ε∞ = 4.2 at 3 g/cm3 and 3000 K, and ε∞ = 3.7 at 4 g/cm3 and 1000 K. These values were used to infer the BEC tensors.

At 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K, the liquid water is partially molecular and partially dissociated with frequent proton jumps. The diagonal BEC values for hydrogen atoms (\({Z}_{\alpha \alpha }^{H}\)) can sometimes exceed the nominal charge of + 1. In Fig. 2e, we correlate the distances between all H atoms and their nearest two oxygen atoms with the mean BEC diagonal values(\(3| {Z}_{\alpha \alpha }^{H}{| }^{2}={({Z}_{xx}^{H})}^{2}+{({Z}_{yy}^{H})}^{2}+{({Z}_{zz}^{H})}^{2}\)). This shows that the anomalously large BEC diagnoal values occurs when a hydrogen atom breaks the bond with its nearest oxygen and forms a bond with the second nearest oxygen, analogous to the Grotthuss mechanism. At 3 g/cm3 and 3000 K, the FCC superionic ice exhibits even larger fluctuations of BECs for both hydrogen and oxygen. The anomalous BECs of hydrogen are again correlated to the O-H bond breaking and formation, and such events are more frequent. At 4 g/cm3 and 1000 K, the stable phase is ice X with a BCC lattice of oxygen atoms, and hydrogen atoms are evenly positioned between two neighboring oxygen atoms with straight O-H-O bonds. The diagonal values of BEC tensors have very small fluctuations and are centered around the oxidation numbers of + 1 for hydrogen and − 2 for oxygen ions (shown as crosses in the right panel of Fig. 2d). Intriguingly, the off-diagonal elements of BEC for H show two separate clusters at positive and negative values.

The ionic electrical conductivity σ is crucial for characterizing ionic and superionic systems. To compute σ at 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K, we employed a CACE-LR model that was finetuned using energy, forces, and BEC tensor values of 100 configurations at the same condition. We performed an equilibrium MD simulation of 120 ps duration with 54 water formula units, and such system size was selected to be directly comparable to the previous DFT MD simulation from ref. 51. we calculated the current-current correlation functions C(t) = 〈J(0)J(t)〉/3e either using the time-dependent BEC tensor Z*(t) or the fixed nominal charges of qH = + 1 and qO = − 2. These correlation functions are shown in Fig. 3a, and at short times they are in perfect agreement with a tour-de-force DFT MD and BEC tensor calculation of 15 ps from ref. 51. Figure. 3b shows the σ values computed by integrating the corresponding C(t) functions using the Helfand-Einstein formula52, a reduced-variance form of the Green-Kubo relation in Eq. (11). Interestingly, the estimated σ with time-dependent BEC tensors (32 ± 2 S/cm) is similar to the estimate of σ = 37 ± 2 S/cm with the constant qH = + 1 and qO = − 2. Such observation was also made in ref. 51, and was rationalized in ref. 53 from a topological quantization argument albeit only for atomic liquids with all species adiabatically staying in the same motifs without changing oxidation states.

a shows the current-current correlation functions C(t) computed using either time-dependent Born effective charge tensors Z*(t) or fixed normal charges. b plots the corresponding time integrals for estimating the ionic electrical conductivity σ. In a and b, the DFT molecular dynamics results are from ref. 51. c illustrates the time-dependent charge displacement from CACE-LR molecular dynamics simulations under constant external electric fields with the specified intensities. The colored lines show the displacements along the direction of the applied field, and gray lines show the displacements along the other orthogonal directions.

One can also compute σ from non-equilibrium MD simulations under external electric fields. Figure 3c shows the total displacement of charges in the system over time under different values of the external field \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{0}\) along the z direction, \(D(t)={\sum }_{i}^{N}{q}_{i}({z}_{i}(t)-{z}_{i}(0))\), computed using the constant charges qH = + 1 and qO = − 2. σ can be estimated from the slope of D(t) as \(\sigma =\langle dD(t)/dt\rangle /V{{\mathcal{E}}}^{0}\). Such σ values from these finite-electric-field simulations, as displayed in the legend of Fig. 3c, are consistent with the equilibrium results, but have better statistical convergence and also avoid the problems associated with the Green-Kubo integration to the infinite time limit (Eq. (11)).

Example: Ferroelectric perovskite

Ferroelectric materials are unique in that they exhibit spontaneous and permanent electric polarization, and this polarization can be reversed by applying an electric field54. Anomalously large BECs that exceed the nominal charges of ions are often considered hallmarks of ferroelectric materials55,56,57. Here, we demonstrate that our method can predict the anomalous BECs and model the characteristic P-\({\mathcal{E}}\) hysteresis loop in the prototypical PbTiO3 ferroelectric perovskite. At T = 300 K, PbTiO3 exhibits a tetragonal phase characterized by a short axis a and a long axis c, with the ratio c/a correlated with the polarization magnitude (see Fig. 4a).

a A snapshot of equilibrated PbTiO3 at T = 300 K. b The BEC tensors (Z*) computed from LES versus from PBE-DFT calculations for 45 randomly selected configurations. The + symbol indicates the nominal charge of Pb/Ti/O in black/blue/red color. c P-\({\mathcal{E}}\) hysteresis loop computed from CACE-LR MD simulations under different external electric fields. d Time evolution of the total polarization during the non-equilibrium MD with \({\mathcal{E}}=-0.06\) V/ Å applied. e Local dipole spatial distributions through the polarization reversal event. Each voxel represents a Ti-centered unit cell.

We trained the CACE-LR model using the energies and forces of the PbTiO3 dataset from ref. 58, computed using SCAN DFT. The potential achieved test RMSEs of 0.4 meV/atom in energy and 79.8 meV/ Å in forces, much reduced from the original model with 1 meV/atom in energy RMSE and 350 meV/ Å in force RMSE from ref. 58.

Without explicitly learning the BEC tensors, Fig. 4b compares them for 45 atomic configurations (including both cubic and tetragonal phase) predicted using LES and computed using PBE DFT. Not only do the LES predictions agree well with the DFT reference, the anomalously large diagonal values of BECs (\({Z}_{\alpha \alpha }^{* }\)) relative to the nominal ionic charges (indicated by the plus signs in Fig. 4b) for qPb = + 2, qTi = + 4, and qO = − 2 are captured. The anomalous diagonal BECs in ferroelectrics are typically considered to come from a complex interplay of global charge transfer, mixed ionic-covalent bonding, and the hybridization between oxygen and transition metal orbitals56. The successful prediction of the BEC tensors here thus not only showcases the expressiveness of the LES method, but also indicates that CACE-LR is able to capture the intricate long-range electrostatic interactions in ferroelectric materials59. Unlike previous approaches27,58,60 that employ separate models for potential energy surfaces and polarization, CACE-LR properly embeds the latter into the former and does not explicitly train on polarization.

To characterize the spontaneous polarization of PbTiO3 in the absence of an external electric field, we performed equilibrium NPT simulations at T = 300 K (see Methods). Because SCAN-DFT overestimates c/a = 1.14 for the ground state tetragonal PbTiO3 structure compared to c/a = 1.06 from experiments, we applied an isotropic external pressure of 2.8 GPa in the NPT simulations as used in ref. 58, yielding c/a = 1.07 for the equilibrated structures in MD. We then calculated the total polarization of the material as61:

where Δuiβ indicates the atomic displacement from the non-polar centrosymmetric reference state. The polarization predicted based on the LES BEC tensors is P = 82 ± 2 μC/cm2, consistent with the experimentally reported polarization P(25∘C) = 81 μC/cm2 62.

We then simulated the P-\({\mathcal{E}}\) hysteresis loop of PbTiO3 at T = 300 K, by applying an electric field \({\mathcal{E}}\) along and against the polarization direction of the equilibrated structure with a magnitude ranging from 0.02 to 0.08 V/ Å. A constant value of ε∞ = 7.532 was used here, with detailed in the Methods section. The analogous simulations for the paraelectric phase at 1000 K are presented in Fig. 8 of the Methods. Figure. 4c presents the time-averaged polarization at various external field strengths after equilibration, demonstrating polarization reversal to a negative value at \({\mathcal{E}}=-0.06\) V/ Å. Starting from the MD structure at \({\mathcal{E}}=-0.08\) V/ Å, we simulated the reverse polarization process by varying the electric field from −0.06 to 0.08 V/ Å (blue line in Fig. 4c), which exhibits the expected reverse transition behavior and completes the ferroelectric hysteresis loop. Note that the width of the hysteresis loop will be dependent on the system size and simulation time, as phase transition is an activated event, and the hysteresis loop in Fig. 4c aims to demonstrate the existence of hysteresis in the ferroelectric PbTiO3. In contrast, the paraelectric phase (see Fig. 8) exhibit no hysteresis.

Figure 4d illustrates the time evolution of the total polarization during the non-equilibrium MD trajectory after applying \({\mathcal{E}}=-0.06\) V/ Å to the original equilibrated structure at T = 300 K. The polarization drops rapidly from its spontaneous value to negative values, followed by fluctuations before equilibrating to the new field-induced equilibrium state. To visualize the atomic-level process for the polarization reversal, we computed the local dipole moment p for each Ti-centered unit cell using \({p}_{\alpha }=e{\sum }_{j}{w}_{j}{Z}_{j\alpha \beta }^{* }\Delta {u}_{j\beta }\), where the sum runs over all atoms j in the unit cell, and wj represents the weighting factor (1 for Ti, 1/8 for Pb, 1/2 for O). Figure 4e shows the spatial distributions of p from representative MD snapshots, with the color of each voxel corresponding to the magnitude of p along the c axis. Snapshots (2)–(4) reveal the initial stage of the reversal: domains of opposite polarization nucleate, grow, coalesce, and ultimately form a uniformly negatively polarized state.

Discussion

The central thesis of the present paper is that MLIPs can infer the response of a material or chemical system to an external electric field, by fitting latent charges (qles) just from the energies and forces of atomic configurations. Although previous works provide some hints on such a connection, e.g., by showing that machine-learned charges are correlated with DFT charges20,63, this paper provides a clear physical picture and provides convincing demonstrations on diverse systems. Compared with previous approaches that directly learn either BEC tensors or electrical response properties27,28,29,32,33,34,64, our method embeds these properties in the MLIP itself and provides a unified framework.

Our approach involves several conceptual advances. First, we recognize that free atomic charges can be determined by fitting to the energies and forces, and that it is neither necessary nor advantageous to explicitly fit to the semiclassical partial charges from DFT20. Indeed, the DFT partial charges are not physical observables, and they depend on the specific partitioning strategy used65,66,67 and are less indicative of atomic charge states in oxides with charge transfer effects68. Our approach of not fitting to the DFT partial charges is in contrast with several other existing long-range MLIP methods11,12,13,14.

Second, we incorporate the background fast-responding charges into the high-frequency relative permittivity ϵ∞, while explicitly accounting for the Coulomb interactions between the atomic charges. This is similar to the concepts of screened Coulomb interactions and the scaled ion charge in the MDEC model35,36. MDEC is foundational for designing and justifying non-polarizable force fields using scaled ion charges6,7, including the popular SPC-type water models69,70. The accuracy of the LES BEC based on \({q}_{i}=\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{\infty }}{q}_{i}^{{\rm{les}}}\) provides a “smoking-gun” validation of the MDEC theory. In addition, our approach is a cleaner way to use the charge scaling framework, as the flexible charges are learned from ab initio data. In comparison, the empirical force fields have the scaled charges and other parameters fitted at the same time to experimental data, which means the errors in describing the electrostatic interactions can be partially canceled by tuning other non-bonded parameters and vice versa, so the resulting charges are less reflective of the true underlying electrostatics. Moreover, the LES framework assigns flexible charges based on local atomic environments. Such environment-dependent charges are more expressive than the fixed charges in empirical force fields. For example, the same LES model is capable of predicting BEC tensors for dramatically different phases of water, including isolating ice, superionic ice, and ionic water (Fig. 2). It is difficult to imagine a fixed-charge model to match this level of expressiveness.

Third, we derive the Born effective charge tensor \({Z}_{i}^{* }\) of each atom from the predicted unscaled charges q, by taking the derivative of the total polarization P with respect to atomic positions. For periodic-boundary-condition systems, where P is not well-defined, we develop a generalized formulation (Eq. (9)). Unlike the DFT partial charge, which suffers from the lack of a unified definition, the BEC tensors are physical observables. The physicality of the BECs and the value of their predictions are already recognized in previous machine learning studies that directly fit to this tensorial quantity28,29. The fact that the LES BEC tensors align well with the DFT values proves that the LES charges are physical and capable of capturing the electric response of the system. Moreover, the link between q and \({Z}_{i}^{* }\) gives the option to train or finetune the MLIP using DFT BECs, e.g., as we did for the water, the superionic water, and the PbTiO3 system in the Methods section. Successful prediction of BECs is also practically useful, as it can be used to predict a number of electrical response propertie,s such as IR and conductivity. It also provides the linear response of forces to an applied electric field (Eq. (1)), enabling straightforward incorporation of external fields in MLIP molecular dynamics simulations.

We demonstrated the framework on a diverse set of complex bulk systems, including liquid water, ionic high-pressure water, superionic water ice, insulating ice X, and ferroelectric PbTiO3. The LES predicted Z* are largely in good agreement with DFT, even when trained only on energies and forces, with further improvement possible by explicitly finetuning on DFT dipoles or BEC tensors during the training. While this inference-based approach may result in a higher prediction error for the BEC tensors compared to models that directly predict these tensorial quantities28,29,64, it provides a more unified framework by demonstrating that electrical response is fundamentally encoded within the potential energy surface and can be learned solely from energies and forces. As the electrical response predictions come solely from the long-range LES augmentation, any short-range MLIP architecture can be used. The possibility to predict BEC tensors might also extend to other long-range MLIP methods that rely on atomic partial charges10,11,12,13, although this remains to be tested.

Moreover, the avoidance of training on DFT BEC tensors, which need to be computed from costly DFPT calculations, makes our approach feasible for any standard MLIP training set with only energy and force labels. This is particularly convenient for building universal MLIPs that are generally applicable across the periodic table. Notably, the model generalizes well across different phases and thermodynamic conditions, as seen in high-pressure water (Fig. 2). The framework also enables quantitative predictions of key electrical response properties, such as the IR spectra of water, ionic conductivity in high-pressure water, and the P-\({\mathcal{E}}\) hysteresis loop in PbTiO3.

To conclude, this paper resolves a critical limitation of state-of-the-art machine learning interatomic potentials: their inability to intrinsically predict electrical response properties. By rigorously linking the latent charges to the experimentally measurable BECs, we bridge the gap between MLIPs and the electrostatics in quantum mechanical systems. Extensions to interfacial systems are possible and will be a part of our future work71. Our framework provides a systematic approach to develop and refine MLIPs for modeling polarizable systems under external fields that can be time or space-dependent, unlocking numerous applications such as electrolyte design, modeling electrochemical interfaces, piezoelectrics, and pyroelectrics.

Methods

Water

The RPBE-D3 bulk water dataset contains energies and forces of 654 configurations (64 water molecules in each snapshot), which were generated via an on-the-fly learning scheme from MD trajectories at different temperatures28. The original MLIP trained on this RPBE-D3 data from ref. 28 has an RMSE of 0.8 meV/atom and 60 meV/ Å for energies and forces, respectively. Reference 28 also provided an additional RPBE-D3 dataset of 100 configurations that were separately collected from NVT simulations at experimental density, and 298.2 K. This set includes Born effective charges in addition to energies and forces. We will refer to this set as RPBE-D3 + BEC.

We trained four versions of CACE-LR: (1) trained solely on energies and forces with a cutoff radius rcut = 5.5 Å using RPBE-D3 data, (2) trained solely on energies and forces with rcut = 4.5 Å using RPBE-D3 data, (3) trained solely on energies and forces with a smaller dataset and rcut = 4.5 Å using RPBE-D3 + BEC data, and (4) trained on energies, forces, and Born effective charges with a smaller dataset and rcut = 4.5 Å using RPBE-D3 + BEC data. For the CACE representation, we used 6 trainable Bessel radial functions, c = 12, \({\ell }_{\max }=3\), \({\nu }_{\max }=3\), Nembedding = 2, no message passing, 1-dimensional hidden variable, σ = 1 Å, and kc = π (dl = 2 Å).

Table 1 summarizes the number of configurations in each dataset, along with the applied cutoff settings and the corresponding test RMSE values for energies, forces, and Born effective charge (BEC) tensors. BEC metrics were evaluated on the same 100 water configurations used in Fig. 1.

DFPT calculations with the RPBE-D3 functional using VASP predict the high-frequency permittivity (ε∞) of water at experimental density and room temperature to be 1.83. We use this value when converting LES charges qles to the free atomic charges q. Such value is very close to the experimental value of 1.78 for water (with the refractive index of water of 1.333 being the square root of this value).

Figure 5 compares the reference DFT and LES BEC predicted by the model trained on BEC (version 4) for the same 100 water configurations used in Fig. 1. As expected, training directly on BEC data improves agreement between LES and reference DFT results, although the improvement is modest. This indicates that while prediction accuracy can be further enhanced by training with BEC data, the potential trained exclusively on energies and forces (version 2, Fig. 1) already exhibits sufficiently high accuracy. In the main text, all the reported results are from the version 2).

We performed equilibrium NVT simulations in ASE at a density of 0.997 g/cm3 and 300 K for a system of 64 water molecules, employing the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. The finite-field MD simulations followed the same setups. As the sum of Z* is not exactly zero due to the small residual prediction errors, in the finite-field MD simulations, the total mean forces on all atoms were removed every step to eliminate the non-zero center-of-mass velocities arising under the electric field. Although such mean forces do not affect any physical observables, they can interfere with the thermostat and the visualization of the trajectories. In all cases, MD simulations were conducted for 50 ps with a time step of 0.25 fs. IR spectra were calculated from the MD trajectories employing Eq. (12), which involves computing the polarization current of the system, \({\bf{J}}(t)={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{Z}_{i}^{* }(t)\cdot {{\bf{v}}}_{i}(t)\). A Gaussian filter was applied following the Fourier transform, and each IR spectrum was normalized by its integrated area.

Figure 6 shows that the IR spectrum calculated using fixed nominal charges does not reproduce peak intensities and shapes well. Moreover, it completely fails to capture the hydrogen-bond stretching mode at approximately 200 cm−1. These results highlight the importance of accurately predicting Born effective charges to obtain detailed and reliable IR spectra.

The experimental IR spectrum42 is included as gray shading for reference.

Figure 7 presents computational IR spectra of liquid water obtained using four differently trained potentials (Table 1). All four versions of the CACE-LR potentials exhibit consistent peak positions and intensity trends, closely matching the experimental IR spectrum. Notably, these potentials differ in training dataset size, cutoff radius, and inclusion of Born effective charges, demonstrating robustness and reliability across varying training conditions.

Comparison of computational IR spectra of liquid water obtained from four differently trained MLIPs based on RPBE-D3 data. The experimental IR spectrum42 is included as gray shading for reference.

Superionic water

The original training set of superionic water has 17,516 configurations (90% train/10% test split), spanning a wide range of thermodynamic conditions (300 K-15,000 K, 1 g/cm3-7 g/cm3), and it was trained using N2P272 with a cutoff of 12 Bohr, yielding test RMSE errors of 14 meV/atom i n energy, and 740 meV/A in forces49.

We randomly selected 5000 configurations (90% train/10% test split) from the original dataset. For the CACE-SR part, we used rcut = 3.5 Å, 6 Bessel radial functions, c = 12, \({\ell }_{\max }=3\), \({\nu }_{\max }=3\), Nembedding = 3, and 1 message passing layer. The LES model uses a one-dimensional hidden variable, σ = 1 Å, and kc = π (dl = 2 Å). The test RMSEs are 7 meV/atom in energy, and 327 meV/A in forces.

For comparing BECs, we randomly selected 100 configurations of 54 water molecules at 3 g/cm3 and 3000 K from DFT MD trajectories from ref. 51. We also selected 100 uncorrelated configurations of 54 water molecules from MLP MD simulations at 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K, and at 4 g/cm3 and 1000 K. We employed VASP to calculate the Born effective charge tensor for these configurations using DFPT, with a plane-wave cutoff of 400 eV at the Baldereschi point, consistent with ref. 51.

We further finetuned the CACE-LR model using the energy, forces, and BEC values of the 100 configurations (90% train/10% test split) at 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K. Before the finetuning, the RMSE errors in energy, forces, and BEC are 4.5 meV/atom, 103 meV/A, and 0.136 e, respectively. After the finetuning, the test RMSE errors reduced to 0.67 meV/atom and 101 meV/A, and 0.09 e, respectively.

For computing conductivities, we used this finetuned model to perform equilibrium NVT simulations in ASE at 2 g/cm3 and 2000 K for a system of water molecules, employing the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. The timestep was set to 0.3 fs, and the simulation length is 120 ps (400,000 steps) following 3 ps of equilibration. The finite-field MD simulations follow a similar setup, except that a shorter simulation time of 30 ps (100,000 steps) was used.

PbTiO3 perovskite

To fit the CACE-LR potential, we used the original training (4432 configurations) and test datasets (600 configurations) from ref. 58 and randomly allocated 10% of the original training data as the validation set. Both the training and test datasets contain the SCAN-DFT calculated energy and forces of PbTiO3 atomic configurations from DP-GEN MD simulations at 300/600/900 K, covering the cubic (ferroelectric) and tetragonal (paraelectric) phases in 3 × 3 × 3 PbTiO3 unit cells (135 atoms). For the CACE-SR part, we used rcut = 6.0 Å, 6 Bessel radial functions, c = 12, \({\ell }_{\max }=3\), \({\nu }_{\max }=3\), Nembedding = 3, and 1 message passing layer. The LES model uses a one-dimensional hidden variable, σ = 1 Å, and kc = π (dl = 2 Å). The CACE-LR potential trained only on SCAN DFT energy and forces denotes E + F model.

To evaluate the LES BECs against DFT BECs, we randomly selected 443 atomic configurations from the training set for DFT calculations. These configurations were further split into train/val/test sets with a ratio of 8:1:1 for fine-tuning purposes. The test set comprised 45 atomic configurations and was used for comparison in Fig. 4. For computing LES BECs, we replicated the supercells of these configurations 3 × 3 × 3, to eliminate the finite-size effects due to finite k. As a proof of concept, we performed DFPT calculations for the BEC tensors at the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) level of accuracy. Given that BECs are physical observables and the SCAN functional is not currently supported for DFPT, we believe using the PBE functional for the reference calculation is a rational and practical choice under these constraints. According to our test, the LEC-BEC derived from SCAN-DFT demonstrates good agreement with the PBE-DFT BEC. The E + F model was further fine-tuned with the PBE-DFT energy, forces, and BEC. Figure 8 displays the comparison after fine-tuning, which demonstrates a marginal improvement from an RMSE of 0.586 e to 0.384 e for diagonal components and from 0.257 e to 0.254 e for off-diagonal components of the BEC tensors when comparing the E + F model to the fine-tuned model. The DFPT calculations were performed using VASP with the PBE functional73, a Gamma-centered k-point, and a plane-wave energy cutoff of 680 eV. The DFT calculations were performed on 3 × 3 × 3 the PbTiO3 unit cell, with a convergence of 10−6 eV in total energy.

For computing the ferroelectric properties of PbTiO3, we employed the E + F model to perform equilibrium NPT simulations using ASE at P = P0 + Pa with the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Here, P0 represents the ambient pressure (1 bar) and Pa = 2.8 GPa is an applied correction to compensate for the DFT overestimation of the c/a ratio as suggested in ref. 74. The simulation structure was initialized with a 9 × 9 × 9 supercell of the cubic PbTiO3 unit cell (space group \(Pm3\bar{m}\)). The MD simulations were conducted with a timestep of 2 fs. For simulations without external electric fields, we performed 100 ps production runs following 10 ps of equilibration. The finite-field MD simulations followed a similar protocol, except that a shorter simulation time of 50 ps was used.

To estimate the high-frequency dielectric constant ε∞, we performed small-scale MD simulations with a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell at T = 300 K to sample equilibrated structures. These atomic configurations were subsequently analyzed using DFPT to obtain the microscopic dielectric constant. We calculated the averaged diagonal value ε∞ = 1/Niα∑iαεαα = 7.532 of the dielectric constant tensor, where the standard deviation of σ(ε∞) = 0.1 from different snapshots at the same thermodynamic condition is small. Note that although we used 50 snapshots to obtain the average ε∞, one snapshot would have been sufficient due to the small σ(ε∞) This pre-computed, averaged scalar value was then used as the fixed scaling factor of \(\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{\infty }}\) for computing the polarization of PbTiO3 in the large-scale MD simulations presented in Fig. 4a, c, d, e, and no additional DFPT calculation is needed.

For the plots in Fig. 4b–e, a parity transformation of −1 was applied to align the BEC and polarization direction with conventional notation.

In addition, we calculated the P-\({\mathcal{E}}\) curve for the paraelectric phase at T = 1000 K. The MD simulations revealed the absence of spontaneous polarization at zero electric field, and no hysteresis was observed for the paraelectric phase (see Fig. 8b).

Notes on implementation

The LES method was implemented in the CACE code, https://github.com/BingqingCheng/cace. In practice, we use an Atomwise module to predict an internal hidden charge \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{raw}}}={Q}_{\phi }({B}_{i})\) based on a set of local invariant representations Bi. The long-range energy is then computed using an Ewald module as

To obtain the LES charges qles in the unit of [e], the internal hidden charges qraw should be scaled by a factor of 1/9.48933, due to the internal normalization factor used (1/2ε0 = 1).

We then use a Polarization module to compute the polarization of the system based on \({q}_{i}^{{\rm{raw}}}\). If the system is finite, the non-periodic expression (Eq. (7)) is used, and if the system is periodic, the generalized polarization in Eq. (9) is used. One can add a normalization factor in this module. The default setting is to remove the mean average charge before computing the polarization. If the factor of \(\sqrt{{\epsilon }_{\infty }}/9.48933\) is used, the correct magnitude of the polarization will be recovered.

We then use the Grad module to take the derivative of polarization with respect to atomic positions using autograd (see Eq. (8)). For finite systems, this step already provides the BECs. For periodic systems, however, we need to use the Dephase module to remove the complex phase factor in Eq. (10), in order to get the real-valued BECs. Example scripts for computing BECs are provided in the SI repository.

Data availability

The training sets, training scripts, BEC inference scripts, and trained CACE potentials are available at https://github.com/BingqingCheng/LES-BEC.

Code availability

The CACE package is publicly available at https://github.com/BingqingCheng/cace.

References

Wang, C.-Y. u, Sharma, S., Gross, E. K. U. & Dewhurst, J. K. Dynamical born effective charges. Phys. Rev. B 106, L180303 (2022).

Resta, R. Macroscopic polarization in crystalline dielectrics: the geometric phase approach. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 899 (1994).

Resta, R. & Vanderbilt, D. Theory of polarization: a modern approach, in Physics of ferroelectrics: a modern perspective (Springer, 2007) 31–68.

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355 (1997).

Zhang, C., Sayer, T., Hutter, J. ürg & Sprik, M. Modelling electrochemical systems with finite field molecular dynamics. J. Phys.: Energy 2, 032005 (2020).

Kirby, B. J. & Jungwirth, P. Charge scaling manifesto: A way of reconciling the inherently macroscopic and microscopic natures of molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7531–7536 (2019).

Jorge, M. Theoretically grounded approaches to account for polarization effects in fixed-charge force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 180901 (2024).

Keith, J. A. et al. Combining machine learning and computational chemistry for predictive insights into chemical systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 9816–9872 (2021).

Unke, O. T. et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Unke, O. T. & Meuwly, M. Physnet: A neural network for predicting energies, forces, dipole moments, and partial charges. J. Chem. theory Comput. 15, 3678–3693 (2019).

Ko, T. szW. ai, Finkler, J. A., Goedecker, S. & Behler, J. A fourth-generation high-dimensional neural network potential with accurate electrostatics including non-local charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 12, 398 (2021).

Gong, S. et al. A predictive machine learning force-field framework for liquid electrolyte development. Nat. Mach. Intell. 7, 543–552 (2025).

Shaidu, Y., Pellegrini, F., Küçükbenli, E., Lot, R. & de Gironcoli, S. Incorporating long-range electrostatics in neural network potentials via variational charge equilibration from shortsighted ingredients. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 47 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. A deep potential model with long-range electrostatic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 124107 (2022).

Gao, A. & Remsing, R. C. Self-consistent determination of long-range electrostatics in neural network potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 1572 (2022).

Grisafi, A. & Ceriotti, M. Incorporating long-range physics in atomic-scale machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 204105 (2019).

Faller, C., Kaltak, M. & Kresse, G. Density-based long-range electrostatic descriptors for machine learning force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 214701 (2024).

Kosmala, A., Gasteiger, J., Gao, N. & Günnemann, S. Ewald-based long-range message passing for molecular graphs, in International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2023) 17544–17563.

Cheng, B. Latent ewald summation for machine learning of long-range interactions. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 80 (2025).

King, D. S., Kim, D., Zhong, P. & Cheng, B. Machine learning of charges and long-range interactions from energies and forces. Nat. Commun. 16, 8763 (2025).

Behler, J. örg & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: A class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

Batzner, S. et al. E (3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G., Ortner, C. & Csányi, G. ábor Mace: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 11423–11436 (2022).

Grisafi, A., Wilkins, D. M., Csányi, G. ábor & Ceriotti, M. Symmetry-adapted machine learning for tensorial properties of atomistic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 036002 (2018).

Stocco, E., Carbogno, C. & Rossi, M. Electric-field driven nuclear dynamics of liquids and solids from a multi-valued machine-learned dipolar model. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 304 (2025).

Schmiedmayer, B. & Kresse, G. Derivative learning of tensorial quantities-predicting finite temperature infrared spectra from first principles, J. Chem. Phys. 161, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0217243.

Schienbein, P. Spectroscopy from machine learning by accurately representing the atomic polar tensor. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 705–712 (2023).

Gastegger, M., Schütt, K. T. & Müller, K.-R. Machine learning of solvent effects on molecular spectra and reactions. Chem. Sci. 12, 11473–11483 (2021).

Shao, Y., Andersson, L. innéa, Knijff, L. & Zhang, C. Finite-field coupling via learning the charge response kernel. Electron. Struct. 4, 014012 (2022).

Falletta, S. et al. Unified differentiable learning of electric response. Nat. Commun. 16, 4031 (2025).

Zhang, Y. & Jiang, B. Universal machine learning for the response of atomistic systems to external fields, Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42148-y.

Joll, K., Schienbein, P., Rosso, K. M. & Blumberger, J. Machine learning the electric field response of condensed phase systems using perturbed neural network potentials, Nat. Commun. 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52491-3.

Leontyev, I. V., Vener, M. V., Rostov, I. V., Basilevsky, M. V. & Newton, M. D. Continuum level treatment of electronic polarization in the framework of molecular simulations of solvation effects. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 8024–8037 (2003).

Leontyev, I. & Stuchebrukhov, A. Accounting for electronic polarization in non-polarizable force fields. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 2613–2626 (2011).

Farahvash, A., Leontyev, I. & Stuchebrukhov, A. Dynamic and electronic polarization corrections to the dielectric constant of water. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 9243–9250 (2018).

Calcavecchia, F. & Kühne, T. D. Metal-insulator transition of solid hydrogen by the antisymmetric shadow wave function. Z. Naturforsch. A 73, 845–858 (2018).

Cassone, G., Sponer, J., Trusso, S. & Saija, F. Ab initio spectroscopy of water under electric fields. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 21205–21212 (2019).

Cheng, B. Cartesian atomic cluster expansion for machine learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 157 (2024).

Montero de Hijes, P. et al. Comparing machine learning potentials for water: Kernel-based regression and behler-parrinello neural networks, J. Chem. Phys. 160, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0197105.

Bertie, J. E. & Lan, Z. Infrared intensities of liquids xx: The intensity of the oh stretching band of liquid water revisited, and the best current values of the optical constants of H2O (l) at 25∘c between 15,000 and 1 cm-1. Appl. Spectrosc. 50, 1047–1057 (1996).

Silvestrelli, P. L., Bernasconi, M. & Parrinello, M. Ab initio infrared spectrum of liquid water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 277, 478–482 (1997).

Heyden, M. et al. Dissecting the THz spectrum of liquid water from first principles via correlations in time and space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 12068–12073 (2010).

Futera, Z. & English, N. J. Communication: Influence of external static and alternating electric fields on water from long-time non-equilibrium ab initio molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 031102 (2017).

Ojha, D., Karhan, K. & Kühne, T. D. On the hydrogen bond strength and vibrational spectroscopy of liquid water. Sci. Rep. 8, 16888 (2018).

Wang, Z., Pakoulev, A., Pang, Y. & Dlott, D. D. Vibrational substructure in the OH stretching transition of water and HOD. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 9054–9063 (2004).

Millot, M. et al. Nanosecond X-ray diffraction of shock-compressed superionic water ice. Nature 569, 251–255 (2019).

Cheng, B., Bethkenhagen, M., Pickard, C. J. & Hamel, S. Phase behaviours of superionic water at planetary conditions. Nat. Phys. 17, 1228–1232 (2021).

Reinhardt, A. et al. Thermodynamics of high-pressure ice phases explored with atomistic simulations. Nat. Commun. 13, 4707 (2022).

French, M., Hamel, S. & Redmer, R. Dynamical screening and ionic conductivity in water from ab initio simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 185901 (2011).

Grasselli, F. & Baroni, S. Invariance principles in the theory and computation of transport coefficients. Eur. Phys. J. B 94, 1–14 (2021).

Grasselli, F. & Baroni, S. Topological quantization and gauge invariance of charge transport in liquid insulators. Nat. Phys. 15, 967–972 (2019).

Rabe, K., Dawber, M., Lichtensteiger, C., Ahn, C.H. & Triscone, J.-M. Modern physics of ferroelectrics: Essential background, in Physics of Ferroelectrics: A Modern Perspective (Springer, 2007) 1–30.

Resta, R. & Sorella, S. Many-body effects on polarization and dynamical charges in a partly covalent polar insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4738 (1995).

Ghosez, P., Michenaud, J.-P. & Gonze, X. Dynamical atomic charges: The case of ab o 3 compounds. Phys. Rev. B 58, 6224 (1998).

Filippetti, A. & Spaldin, N. A. Strong-correlation effects in born effective charges. Phys. Rev. B 68, 045111 (2003).

Xie, P., Chen, Y., E, W. & Car, R. Thermal disorder and phonon softening in the ferroelectric phase transition of lead titanate. Phys. Rev. B 111, 094113 (2025).

Zhong, W., King-Smith, R. D. & Vanderbilt, D. Giant lo-to splittings in perovskite ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3618–3621 (1994a).

Gigli, L. et al. Thermodynamics and dielectric response of batio3 by data-driven modeling. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 209 (2022).

Rabe, K. M. & Ghosez, P. First-principles studies of ferroelectric oxides, in Physics of Ferroelectrics: A Modern Perspective (Springer, 2007) 117–174.

Burns, G. & Scott, B. A. Lattice Modes in Ferroelectric Perovskites: PbTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 7, 3088–3101 (1973).

Song, Z., Han, J., Henkelman, G. & Li, L. Charge-optimized electrostatic interaction atom-centered neural network algorithm. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 2088–2097 (2024).

Yu, H. et al. Prediction of Room Temperature Ferroelectricity in Subnano Silicon Thin Films with an Antiferroelectric Ground State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 156801 (2025).

Weinhold, F., Landis, C. R. & Glendening, E. D. What is NBO analysis and how is it useful? Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 35, 399–440 (2016).

Verstraelen, T. et al. Minimal basis iterative stockholder: atoms in molecules for force-field development. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 3894–3912 (2016).

Marenich, A. V., Jerome, S. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Charge model 5: An extension of Hirshfeld population analysis for the accurate description of molecular interactions in gaseous and condensed phases. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 527–541 (2012).

Wolverton, C. & Zunger, A. First-principles prediction of vacancy order-disorder and intercalation battery voltages in LixCoO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 606–609 (1998).

Leontyev, I. V. & Stuchebrukhov, A. A. Electronic polarizability and the effective pair potentials of water. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 3153–3161 (2010).

Izvekov, S., Parrinello, M., Burnham, C. J. & Voth, G. A. Effective force fields for condensed phase systems from ab initio molecular dynamics simulation: A new method for force-matching. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 10896–10913 (2004).

Wang, X. et al. Ion-modulated structure, proton transfer, and capacitance in the Pt (111)/water electric double layer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.13727 (2025).

Singraber, A., Morawietz, T., Behler, J. & Dellago, C. Parallel multistream training of high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Chem. theory Comput. 15, 3075–3092 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Zhong, W., Vanderbilt, D. & Rabe, K. M. Phase Transitions in BaTiO3 from First Principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1861–1864 (1994b).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank for valuable discussions with Pinchen Xie, David Limmer, Jeff Neaton, and Greg Voth. The authors thank Sebastien Hamel for providing the DFT MD trajectories for superionic water, and help clarifying questions related to the pseudopotentials. The authors thank Federico Grasselli and Stefano Baroni for providing data and notebooks for computing the conductivity of a molten salt. This research used the Savio computational cluster resource provided by the Berkeley Research Computing program at the University of California, Berkeley (supported by the UC Berkeley Chancellor, Vice Chancellor for Research, and Chief Information Officer). D.S.K. and P.Z. acknowledge funding from the BIDMaP Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C conceived the idea; P.Z., D.K., D.S.K., and B.C. designed and performed the research, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.C. has an equity stake in AIMATX Inc. The University of California, Berkeley, has filed a provisional patent for the Latent Ewald Summation algorithm.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, P., Kim, D., King, D.S. et al. Machine learning interatomic potential can infer electrical response. npj Comput Mater 11, 384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01911-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01911-z

This article is cited by

-

Charge integrated graph neural network-based machine learning potential for amorphous and non-stoichiometric hafnium oxide

npj Computational Materials (2025)