Abstract

The stacking fault energy (SFE) in concentrated alloys is highly sensitive to the local atomic environment. Understanding this relationship necessitates extensive sampling of configurations, which significantly increases computational demands. To address this challenge, we propose a graph neural network (GNN)-based framework utilizing unrelaxed bulk and stacking fault structures as inputs to directly predict SFE. We first investigate two key extrapolation capabilities for bulk formation energy prediction: scale extrapolation (predicting formation energy in larger supercells) and compositional extrapolation (predicting formation energy for compositions beyond the training set). Leveraging the validated model, we concurrently predict formation energies of both bulk and stacking fault configurations to compute the SFE. The structural similarity between these configurations enables efficient parameter sharing, accelerating model convergence. The framework demonstrates excellent interpretability and robust compositional extrapolation capabilities in predicting SFEs. Furthermore, leveraging its exceptional compositional extrapolation, we integrate the model with Monte Carlo simulations to successfully predict ordering behavior and solute segregation at stacking faults. Finally, we introduce a hierarchical training strategy that further reduces data requirements. Collectively, our work establishes a unified and efficient framework for robust prediction of planar fault energies in complex concentrated alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stacking faults (SFs) play a crucial role in determining the mechanical behavior and deformation mechanisms of alloys1,2,3. Experimentally, stacking fault energy (SFE) can be calculated by measuring the distance between paired partial dislocations that connect to the fault plane. However, Shih et al.4 demonstrated that in concentrated alloys, local compositional changes introduce additional forces on the dislocations, making SFE measurement in these alloys unreliable. SFEs can also be calculated through atomic simulations, such as first-principles calculations and empirical potentials2,5,6,7,8,9. A distinct feature of SFE in concentrated alloys is that it is a statistical quantity, requiring sampling across many configurations. This characteristic significantly increases the computational difficulty of first-principles calculations, especially since calculating SFE often demands larger supercells to avoid SF interactions. While empirical potentials can efficiently compute SFEs, they rely on accurate atomic interaction descriptions, limiting their applicability in complex alloy systems.

To accelerate SFE calculations, several surrogate models have been proposed. Vamsi et al.10 proposed a model that approximates the energy of each layer in SF structures by identifying reference structures with similar bonding environments. These reference structures, typically having smaller supercells, can be used to estimate the layer energies and are computationally easier to calculate. However, the model faces two main challenges: the complexity of composition and disorder, which makes it difficult to identify suitable reference structures, and the fact that different SFs require specific reference structures, limiting the model’s applicability across various SF types. LaRosa et al.11 used bonding energy instead of layer energy to calculate SFE. Their model proposes that the total energy of a configuration is the sum of the first-nearest neighbor (1NN) bond energies, with SFE determined by the bond energy difference between the bulk and SF structures. However, this model overlooks variations in bond energy arising from local chemical and structural differences. Sun et al.12 developed a statistical method to efficiently sample SFEs in NiFe and NiCoCrW systems, employing small supercells with large vacuums to reduce interactions between SFs. They found that the mean SFEs correlate with valence electron concentrations. Machine learning methods have also been applied to predict SFEs, typically relying on human-designed descriptors6,13,14,15. However, there remains a critical need for a simple, unified, and system-independent approach that can be easily extended to other types of planar faults.

Recently, graph neural networks (GNNs)16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 have become increasingly popular in materials science due to their ability to extract features from crystal structures without human intervention. Unlike traditional methods, the GNN-based approach can efficiently handle large-scale, complex systems without relying on human-designed descriptors, offering a more robust and system-independent framework for SFE prediction. GNNs have demonstrated excellent predictive capabilities for formation energies, band gaps, elastic properties, and more. Witman et al.25 showed that GNNs can predict formation energies directly from unrelaxed crystal structures, offering advantages over traditional methods like cluster expansion (CE)25,26,27. Unlike CE, which can only be used for energy predictions in a given crystal lattice26,28,29, GNNs can predict energies for different crystal lattice types using a single model17,23,30. This makes GNNs well-suited for predicting SFEs. As the atomic bonding environment farther from the SF resembles that in the bulk, it is expected that bulk and SF data can be mutually utilized, enhancing the prediction of SF structures while reducing data requirements.

In this study, we employ a crystal graph convolutional neural network (CGCNN) model23 to predict formation energies and SFEs in concentrated alloys using unrelaxed bulk and SF structures as input. To comprehensively explore the model performance, we generate datasets with varying supercell sizes and compositions using a widely validated Al–Cr–Co–Fe–Ni empirical potential31. The supercells used in the training process are limited to sizes below 300 atoms, ensuring that this method is compatible with datasets typically used in DFT calculations. We first investigated the model’s extrapolation capabilities using bulk structures. Specifically, we focused on two aspects: scale extrapolation ability (the model’s performance in predicting the formation energies of larger supercells), and composition extrapolation ability (the model’s ability to predict the formation energies of different compositions when trained on a single composition). Next, we extended the model to simultaneously predict the formation energies of bulk and SF structures, enabling the successful prediction of SFE. The contributions of different elements across various layers can be easily visualized, demonstrating the model’s excellent explainability. We also showed the model’s excellent compositional extrapolation ability, which benefits from the fact that the prediction bias for out-of-train formation energies is dependent only on the composition. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the characteristics of this bias can be leveraged in conjunction with Monte Carlo (MC) simulations to investigate ordering behavior and segregation at SFs. Finally, we proposed a hierarchical training strategy, which enables the model to efficiently capture interactions at varying distances, significantly reducing the amount of training data required. The method used in our research can be extended to other types of planar faults, offering a powerful tool to accelerate the development of concentrated alloys.

Results

Formation energy prediction of bulk structures

It has been reported that the supercell size strongly affects the model’s performance on predicting large systems32. Small supercells are limited to capturing only local interactions. While large supercells can account for a greater range of long-range interactions, they come at the cost of significantly increased computational demands. Therefore, choosing an appropriate supercell size is crucial to strike a balance between atomic randomness and computational efficiency.

To illustrate this, we generated four datasets using supercells of different sizes. The 2 × 2 × 2 (\(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{16}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{8}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{2}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{6}\)), 2×2×3 (\(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{24}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{12}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{3}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{9}\)), and 4×4×4 (\(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{128}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{64}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{16}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{48}\)) supercells have the same composition, while the 3 × 3 × 3 (\(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{32}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{16}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{4}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{12}\)) supercell differs due to limitations on the number of atoms. Additionally, two more datasets were created using 6 × 6 × 6 supercells, corresponding to the two compositions. These larger datasets were used to evaluate the extrapolation capabilities of models trained on smaller supercells. For convenience, the 2 × 2 × 2, 2 × 2 × 3, 3 × 3 × 3, and 4 × 4 × 4 supercell datasets are referred to as Dataset-1 to Dataset-4, respectively.

We conducted the learning process on four datasets, which were divided into training, validation, and test sets using an 80/10/10 split ratio. Figure 1a–d shows the trend in mean absolute error (MAE) on the test set as the training set size increases. Larger supercells lead to faster convergence, requiring fewer training samples to achieve high accuracy. All models converge to an MAE below 0.5 meV/atom with approximately 400 training samples, demonstrating excellent predictive performance. Notably, the model trained on the 4 × 4 × 4 supercell achieved the lowest MAE, suggesting that larger supercells further reduce prediction errors. In our study, we consider an MAE below 0.5 meV/atom to indicate sufficient accuracy. Figure 1f–h shows the parity plots for the test set of the four models, each trained with 400 samples.

However, as shown in Fig. 1i–l, the model trained on the 2 × 2 × 2 supercell fails to predict formation energies for the 6×6×6 supercell. This limitation likely arises because smaller supercells restrict atomic arrangement flexibility, preventing them from capturing the true randomness of atomic distributions. Performance on the 6×6×6 supercell improves as the training supercell size increases, with the 3×3×3 supercell already demonstrating reliable predictive capability.

Although datasets based on large supercells can offer better scalability and faster convergence, the computational complexity increases significantly with the number of atoms in DFT calculations. Therefore, using smaller supercells to generate datasets is more resource-efficient. It is important to note that the preparation of the SF dataset requires large supercells to avoid interactions between SFs. Thus, combining bulk data from smaller supercells with SF data from larger supercells may be a more efficient data preparation strategy. We will further discuss this strategy in the section “Discussion”.

Next, we examine the model’s performance in predicting the formation energy of compositions not included in the training set. Since Dataset-3 (3×3×3 supercell) already demonstrates excellent scale extrapobility, we use the model trained on Dataset-3 for this analysis (referred to as Model 1). We prepared a new dataset (Dataset-5), which differs from Dataset-3 in terms of Ni/Co concentrations. Each composition in Dataset-5 contains 100 data points, with Ni varying from 10 to 46 in 4-atom increments, while Co decreases accordingly. For simplicity, the concentrations of Al and Cr are kept constant. The distributions of formation energies of Dataset-3 and Dataset-5 are shown in Fig. 2a. Due to compositional variation, the formation energy distribution in Dataset 5 is more diverse. We directly applied Model 1 to predict the formation energy of Dataset-5. Notably, while the model accurately captured the overall trend of formation energy variation for each composition (with slopes close to 1), a composition-dependent bias relative to the true values was observed. This phenomenon, also noted by Witman et al.25, can be mitigated by including more diverse compositions in the training set, as shown in Fig. 2c

a Formation energy distributions for Datasets-3 and 5; b Predictions of Model 1 (trained on Dataset-3) for Dataset-5. c Parity plot of the model trained directly on Dataset-5, evaluated on its test set. The “…” indicates that, with Al fixed at 8 and Cr at 24, the number of Ni atoms varies as 14, 18, 22, …, up to 46.

Here, we provide a more detailed analysis of this phenomenon. First, recall the formula for formation energy:

where \({E}_{\mathrm{tot}}\) can be further decomposed into two parts: \({E}_{{\rm{tot}}}={E}_{{\rm{avg}}}+{E}_{\mathrm{var}}\). Here, \({E}_{{\rm{avg}}}\) represents the average total energy, which is composition-dependent, while \({E}_{\mathrm{var}}\) accounts for the energy fluctuations due to different atomic arrangements within the same composition. Additionally, the potential term \({\sum }_{i}{\mu }_{i}{c}_{i}\) depends only on the composition. These three components of Dataset-5 are shown in Fig. 3a. Therefore, if the model’s training set includes only a single composition, both \({E}_{{\rm{avg}}}\) and \({\sum }_{i}{\mu }_{i}{c}_{i}\) related to the composition remain constant during training. As a result, when model 1 extrapolates to other compositions, the source of the bias ΔE can be expressed as follows:

where \({E}_{{\rm{avg}}0}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{avg}}1}\) denote the average \({E}_{{\rm{tot}}}\) for Dataset-3 and each composition in Dataset-5, respectively, while \({\sum }_{i}{\mu }_{i}{c}_{i0}\) and \({\sum }_{i}{\mu }_{i}{c}_{i1}\) correspond to the chemical potentials for Dataset-3 and Dataset-5. To validate the reliability of our analysis, we subtracted ΔE from the formation energies predicted by Model 1 on Dataset-5. The results, shown in Fig. 3b, are excellent, with an of 0.994 and an MAE of 0.599 meV/atom, providing strong evidence for the accuracy of our analysis.

SFE prediction

In this section, we expand the application of our model to predict the SFE. According to Eq. 2, calculating SFE requires the formation energies of both the bulk and SF structures. To generate these, we created 1000 bulk structures using a supercell with 192 atoms (1×2×4, Co96Ni48Al12Cr36, the same composition as Dataset-1) along the \(\left[112\right],\) \(\left[1\bar{1}0\right]\) and \(\left[11\bar{1}\right]\) direction. The corresponding SF structures were obtained by tilting the bulk structure by a/12 along the \(\left[112\right]\) direction. In total, we generated 1000 data points for both the bulk and SF structures, which we refer to as the Dataset-Bulk and Dataset-SF, respectively.

While the model can, in principle, predict the SFE directly, calculating the formation energies of the bulk and SF structures separately offers several advantages. First, using SFE as the direct target property often necessitates substantial modifications to the model architecture, such as implementing multi-target learning frameworks with additional MLP layers after the convolutional blocks. Such adjustments increase model complexity, enlarge the number of trainable parameters, and thus raise computational costs, prolong training, and heighten the risk of overfitting, particularly when datasets are limited. Moreover, because the structural differences between SF and bulk configurations are largely confined to the vicinity of the fault while atomic environments further away remain nearly unchanged, the model can exploit their similarity and effectively learn from bulk structures, thereby reducing its reliance on SF data. This is especially advantageous since accurate SF calculations demand large supercells to minimize interactions. Finally, predicting formation energies provides enhanced interpretability, as atomic-level energy contributions can be directly compared between bulk and SF configurations, yielding deeper insights into the microscopic origins of SFE.

Three sets of experiments were conducted to evaluate the model’s performance in predicting the formation energy of SF structures under different training sets. For each experiment, Dataset-Bulk and Dataset-SF are divided into training, validation, and test sets using an 80/10/10 split ratio. When selecting training samples from both Dataset-Bulk and Dataset-SF, it is important to ensure that if a bulk structure is included in the training set, its corresponding SF counterpart should also be included, and vice versa. This is to ensure that during SFE validation, the data used has not been previously trained on.

In the first experiment, we used only the Dataset-SF for training, as seen in Fig. 4a. The model converged to below 0.5 meV/atom after approximately 300 training samples, demonstrating its ability to accurately predict the formation energy of SF structures. In the second experiment, we incorporated 100 additional bulk samples selected from Dataset-1. This reduced the model’s reliance on SF data, with about 250 SF samples required to achieve convergence below 0.5 meV/atom. Furthermore, calculating the SFE requires the corresponding Bulk structure for each SF structure. Therefore, this Bulk data is essential and should be included in the training process. Ultimately, the model achieved high accuracy with just 150 SF samples and their corresponding Bulk counterparts. The model trained with this sample size is referred to as Model 2. Figure 4b, c shows Model 2’s performance on the test sets of Dataset-Bulk and Dataset-SF, respectively, demonstrating high accuracy. Using the predicted formation energies, the SFE can be calculated. For simplicity, we neglected the minor variations in the SF area (Fig. 4d), as they have a negligible impact on the SFE (though lattice constants can also be predicted if necessary23,30). Figure 4e presents a comparison between the predicted and true SFE values. The model achieved a final MAE of only 5.315 mJ/m², indicating its ability to accurately predict the SFE.

a The variation in mean absolute error (MAE) with the number of training samples (x-axis represents the number of SF samples used for training. “SF+Dataset-1” refers to SF samples combined with an additional 100 samples from Dataset-1, while “SF+Dataset-1+Bulk” includes SF samples, 100 samples from Dataset-1, and an equal number of Bulk samples as SF. b, c Predicted results using the “SF+Dataset-1+Bulk” training set, with the sample sizes of SF and Bulk being 200, respectively; d The distribution of stacking fault area in the SF dataset; e Predicted stacking fault energies (SFEs) based on Eq. 2.

We have analyzed the biases when the model predicts formation energies for compositions outside the training data. These biases were found to depend solely on composition. Leveraging this characteristic, we aim to predict the SFE for out-of-training compositions. This is feasible if the bias is solely composition-dependent, meaning that the biases in the predicted SF and bulk formation energies for the same composition are identical. In such a case, the biases can be canceled out when calculating the SFE. To validate this, we prepared four additional datasets with compositions distinct from those used to train Model 2. Each composition includes 200 pairs of bulk and SF formation energies. As shown in Fig. 5a–d, the biases in the predicted bulk and SF formation energies for each composition are identical. Figure 5e compares the prediction errors between SF and bulk structures. \(\Delta {E}_{f,{\rm{Bulk}}}\) represents the difference between the predicted and actual formation energies for bulk structures, while \(\Delta {E}_{f,{\rm{SF}}}\) is defined similarly for SF structures. This finding demonstrates that, although the model cannot accurately predict absolute formation energies for these new compositions, the accurate prediction of \({E}_{\mathrm{var}}\) ensures reliable SFE calculations. This is illustrated in Fig. 5f, where the computed SFEs align closely with the true values despite the biases in individual formation energy predictions.

After the model successfully predicted the SFE, we further demonstrate its superior interpretability. We use the SF structure of pure Co as an example to visualize both the node features and the predicted formation energies for each atom, as shown in Fig. 6. After Convolutional Layer 1, the features of atoms in the 1NN and 2NN layers show distinct differences. As the model advances through Convolutional Layers 2 and 3, atoms across the entire structure begin to capture the influence of the SF (Fig. 6a). The final predicted formation energies are obtained after the MLP Layer 3, as seen in Fig. 6b. For comparison, the predicted formation energy per atom in the bulk structure is also shown, where all Co atoms share identical atomic environments, resulting in the same atomic formation energies. We can clearly observe that the formation energies of the atoms in the two central layers of the SF structure are very similar to those in the bulk structure. As the atomic layers approach the SF, significant variations in formation energy become evident, which contribute primarily to the SFE.

a The variation in the magnitude of the node features in the SF structure after each convolutional layer. b The final predicted formation energy per atom for both bulk and SF structures in pure Co. The orange box in the SF structure highlights regions where the formation energy per atom is similar to that of the bulk structure.

By calculating the formation energy differences for each atom between the SF and bulk structures, we can easily assess the contribution of each element at different positions to the SFE. To illustrate this, we selected three pairs of structures with varying SFE from the Dataset-Bulk/SF, showing the atomic energy differences between the bulk and SF structures. As seen in Fig. 7a, Cr and Al contribute significantly more to the SFE than Co and Ni, with Co having a weak contribution. This is reasonable, as Co stabilizes in an HCP structure at low temperatures. From Fig. 7b, a higher number of Cr atoms in the SF region contributes significantly to the SFE. In Fig. 7c, it is evident that the higher SFE originates from the formation of additional Al–Al bonds in the SF region, which have higher energy, a result consistent with findings from previous studies31,33. The average values of the atomic energy difference for each element at each crystal plane in the Bulk4/SF4 dataset are shown in Fig. 7d. It can be observed that the contribution to the SFE mainly comes from the four atomic layers closest to the SF, with the contribution to the SFE following the order: Al > Cr > Ni > Co.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the successful application of CGCNN in predicting SFE and further explored its capability to predict SFE across different compositions. Building on this, we highlight that through MC simulations, composition-dependent biases can be leveraged to investigate changes in ordering and elemental segregation behavior at SF regions. During the MC simulations, a pair of atoms from different species is randomly selected and swapped. The energy of the new configuration is then calculated as \({E}_{f}^{i+1}\). The swap is accepted with a probability determined using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm:

where \({E}_{f}^{i}\) and \({E}_{f}^{i+1}\) are the total energies before and after the swap, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. Similar to SFE, the composition remains constant before and after each swap. Consequently, the composition-dependent bias is eliminated, enabling the seamless application of the MC algorithm.

As a first example, we demonstrate that Model 2 accurately captures the equilibrium ordering in alloys with different compositions. To test this, we selected a composition outside the training set, \(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{414}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{173}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{70}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{207}\) (6×6×6 supercell with 864 atoms), where all atoms were initially randomly distributed. MC simulations were conducted at 500 K, with Fig. 8a showing the evolution of formation energy and the number of Al–Al bonds as MC simulation progressed. As the simulation progressed, the formation energy significantly decreased, accompanied by a substantial reduction in Al–Al bonds. In Fig. 8b, we compare the formation energies predicted by Model 2 with those calculated using the EAM potential every 50 steps. Despite a bias, Model 2 accurately captures the energy variation trend, highlighting its feasibility in MC simulations. Finally, Fig. 8c presents the Warren–Cowley parameters (WCPs) for the final configuration, where the strong repulsion between Al–Al bonds and the strong attraction of Ni-Al bonds are effectively captured, which is consistent with Farkas et al.’s results31.

a Predicted formation energy and the variation in aluminum–aluminum (Al–Al) bond count as a function of MC steps. b Comparison of predicted formation energies at every 50 MC steps with the formation energies calculated using the embedded atom method (EAM). c Warren–Cowley parameters (WCPs) for configurations obtained at the last MC step.

In the second example, we investigate the elemental segregation behavior at the SF. MC simulations were performed on the SF structure (\(\text{C}{\text{o}}_{384}\text{N}{\text{i}}_{192}\text{A}{\text{l}}_{48}\text{C}{\text{r}}_{144}\), 768 atoms). Figure 9a, b illustrates the evolution of formation energy during the MC process and compare the results from the EAM potential with those predicted by Model 2. Similarly, Model 2 successfully captures the energy variation trend. In Fig. 9c–f, we plotted the number of elements in the nearest-neighbor (1NN) and next-nearest-neighbor (2NN) regions at the SF throughout the simulation. The results show that Co and Cr gradually segregate to the SF region, while Ni and Al experience depletion in the SF region. In Ni/Co-based alloys, previous studies9,34,35 have reported Co segregation and Ni/Al depletion at the SF, and a co-segregation behavior between Co and Cr has been observed, which is in excellent agreement with our results.

From the above two examples, it can be observed that although our model exhibits a bias when predicting the formation energies of out-of-train compositions, many properties do not require an accurate prediction of the absolute formation energy. Instead, they only depend on the energy differences between different configurations. In such cases, the GNN demonstrates strong capabilities, effectively exploring certain properties of alloys in a broader compositional space, even with limited data.

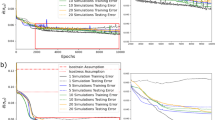

In DFT calculations, the supercell size plays a crucial role in determining computational complexity. Therefore, reducing data calculated on large supercells and learning as much as possible from data of smaller supercells is highly valuable. We have already demonstrated the feasibility of using data from small supercells to reduce the amount of SF data. Here, we take it a step further by proposing a hierarchical training strategy designed to further reduce the data requirements for model training. The training workflow is illustrated in Fig. 10. During the first training phase, our objective is to enable the model to learn to learn both elemental representations (Embedding) and 1NN interactions (Convolutional Layer 1 and MLP Layer 1). Thus, the training set consists of only small supercell data. For bulk structures, we employ 4-atom and 8-atom supercells. For SF structures, supercells with the same grain orientation as the dataset-SF are used, but with only 3 atomic layers along the <111> direction, representing the 1NN environment of the SF region. This supercell contains 12 atoms. We generate 100 configurations for the 4-atom, 8-atom, and 12-atom structures, resulting in a total of 300 data points, denoted as Dataset-6. We first attempt to accelerate the model’s convergence on Dataset-1 (32-atom supercell) using Dataset-6. The model trained on Dataset-6 (split 80/10/10) is frozen at the Embedding layer, Convolutional Layer 1, and MLP Layer 1, and then retrained on Dataset-1 (split 80/10/10). For comparison, we also train a model from scratch by directly incorporating the entirety of Dataset-6 into the training process. The test result with different amounts of training data from Dataset-1 is shown in Fig. 11a. Compared to training solely on Dataset-1 (Fig. 1a), directly incorporating Dataset-6 into the training process (denoted as “mix” in Fig. 11a) results in inferior performance. This degradation may be attributed to the fact that the inclusion of Dataset-6 distracts the model’s attention from Dataset-1. In contrast, our hierarchical training approach exhibits exceptional effectiveness. Remarkably, the hierarchical training strategy achieves an MAE below 0.5 meV/atom using only 100 training samples from Dataset-1, significantly surpassing the performance of the baseline model trained solely on Dataset-1.

The training procedure uses small supercell datasets (4-atom and 8-atom supercells for bulk, and 12-atom supercells for stacking fault (SF) structures) to train the embedding layer, convolutional layer 1, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layer 1. These layers are then frozen during the second training step, which uses medium supercell datasets (32-atom supercells for bulk and 24-atom supercells for SF) to train the remaining layers. In the third training step, datasets of large supercells are used to optimize the remaining parameters.

a, b Mean absolute error (MAE) on the test set as a function of the number of training samples for Dataset 1 and the stacking fault (SF) dataset, respectively. c The computational complexity of the hierarchical training strategy compared with the training strategy used in Fig. 4.

Subsequently, a complete training pipeline is implemented to rapidly predict the formation energy of Dataset-Bulk and Dataset-SF. During the training of Convolutional Layer 2, and MLP Layer 2, an additional set of 100 SF structures (Dataset SF, with the same grain orientation as the SF structure but 6 atomic layers along the <111> direction, representing the 2NN + 3NN structure of the SF, 24 atoms) is prepared and mixed with 100 randomly selected samples from Dataset-1 for training. After further freezing Convolutional Layer 2 and MLP Layer 2, the model is fine-tuned on Dataset-SF and Dataset-Bulk. The MAE as a function of the number of training samples is shown in Fig. 11b. Again, our hierarchical training strategy greatly enhances convergence speed. Notably, compared to Fig. 4, only 50 samples from the Bulk and SF datasets are required to achieve an MAE below 0.5 meV/atom. Moreover, the “mix” training strategy shows worse convergence. Because in DFT calculations, the computational complexity is cubic to the supercell size (\(O\left({N}^{3}\right)\), where N is the number of atoms), the hierarchical training strategy demonstrates a significant advantage. In our case, we simply calculated the computational complexity of the data used in the hierarchical method and compared it with the complexity of the dataset required for direct training shown in Fig. 4. We found that the computational cost is reduced by more than two-thirds compared to the original method.

In summary, this study establishes a GNN framework capable of simultaneously predicting formation energies and SFEs for Co–Ni–Al–Cr concentrated alloys, using solely unrelaxed bulk and stacking fault structures as input. First, we investigated the model’s predictive capabilities on bulk formation energies. Our findings reveal that supercell size critically influences the model’s scale extrapolation performance. Specifically, training on larger supercells substantially enhances prediction accuracy for larger lattice systems. Importantly, integrating data from a limited number of smaller supercells with data from larger ones significantly enhances prediction accuracy while reducing computational costs. Furthermore, we demonstrated the model’s robust compositional extrapolation capabilities. A model trained on a single composition accurately captured the formation energy trends of other, untrained compositions, despite the presence of composition-dependent biases. Critically, we successfully extended the model to predict formation energies for both bulk and stacking fault (SF) structures with a single architecture, enabling accurate SFE predictions.

A key observation is that the composition-dependent bias exhibits consistency between bulk and SF structures for the same composition. This consistency directly leads to the cancellation of the bias in SFE calculations. Consequently, this feature enables efficient and reliable SFE predictions across a range of compositions. Building on this capability, we showed that integrating our model with MC simulations provides a powerful tool for investigating alloy ordering behavior and elemental segregation at SFs. To further mitigate the computational burden of data preparation, we introduced a novel hierarchical training strategy. This approach maximally utilizes data from small supercells to train the lower-level feature extraction layers, thereby significantly reducing computational costs without compromising predictive accuracy. Notably, while the present work focuses on SFEs, the proposed framework is inherently generalizable and can be readily adapted to predict energies of other planar fault types without modification.

Methods

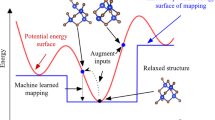

CGCNN model

In this study, we employ the CGCNN model proposed by Xie et al.23 to predict the formation energies of both bulk and SF structures, which allows for a straightforward calculation of the SFE (Fig. 12a). In the CGCNN framework, the crystal is naturally represented as a graph, where nodes correspond to atoms and edges represent chemical bonds (Fig. 12b). The precise definition of bonds in a crystal is often ambiguous and is typically characterized by the interactions between two atoms within a specified cutoff radius. In the CGCNN architecture, both node and edge attributes are encoded as vectors. Node features are initially represented using one-hot encoding based on element types, resulting in an 8-dimensional feature vector. Edge features are embedded via a 6-dimensional Gaussian expansion. In each convolutional layer, the model refines the node attributes by incorporating both node and edge information, as described by the following equation:

where \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{{\left({\boldsymbol{i}},{\boldsymbol{j}}\right)}_{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^{\left({\boldsymbol{t}}\right)}={{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}^{\left({\boldsymbol{t}}\right)}}{\boldsymbol{\oplus }}{{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{j}}}^{\left({\boldsymbol{t}}\right)}}{\boldsymbol{\oplus }}{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_{{\left({\boldsymbol{i}},{\boldsymbol{j}}\right)}_{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\) represents the concatenation of the representations of two nodes and the edge connecting them. The symbol \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication, while σ and g represent the sigmoid and ReLU activation functions, respectively. After N convolution layers, the node representation \({{{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}^{\left({\boldsymbol{N}}\right)}\) encapsulates information from both the node itself and its surrounding environment. Finally, by feeding all node representations into a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) and averaging, the formation energy \({E}_{f}\) of the structure is obtained. In our study, the model architecture includes three convolutional layers, and the cutoff is set to 5 Å. The dimensions of the vector and edge representations are 8 and 6, respectively. An MLP with two hidden layers is then applied to obtain the formation energy. The detailed description of the hyperparameters is described in Table 1.

It is noteworthy that more advanced models incorporating additional geometric information, such as angles and dihedrals, have been developed to yield more accurate representations of crystal structures24,30. However, Witman et al.’s25 study demonstrated that even the minimal-complexity CGCNN architecture performs well in predicting formation energies using unrelaxed structures. Therefore, we adopted the original CGCNN architecture, which contains only 1857 parameters. A detailed description of the CGCNN model can be found in ref. 23.

Data preparation

While our ultimate objective is to develop a model based on DFT data, in this study, we have opted to use results derived from the empirical potential. This significantly reduces the computational cost of data collection while preserving the qualitative characteristics of atomic interactions. We used the FCC-structure Co–Ni–Al–Cr alloys as a representative example and generated data using the EAM potential developed by Farkas et al.31, which has demonstrated high accuracy in predicting formation energies and SFEs4,8,36,37. Geometry optimization was performed on the initially randomly generated face-centered cubic crystal structures, with the formation energy calculated at the final optimization step, all executed using the LAMMPS code38. The supercell size used for generating the bulk data can be chosen arbitrarily. To calculate the SFE, the supercell was oriented in the \(\left[112\right],\) \(\left[1\bar{1}0\right]\) and \(\left[11\bar{1}\right]\) direction and the tilt model33 was used to generate the SF structure. The SFE is calculated by:

where A is the faulted area, and \({E}_{{\rm{f}},{\rm{SF}}}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{f}},{\rm{b}}{\rm{ulk}}}\) is the formation energy of the SF and Bulk structures. Supercells with random distributions of atoms are generated by the ASE39 and Pymatgen40 codes. Vesta41 and ASE are used to visualize the supercells. Notably, the supercells used for training in this study contain no more than 300 atoms (the training process involved structures containing up to 192 atoms, while larger supercells with up to 256 atoms were used only to validate the model performance). As a result, this approach is directly applicable to datasets commonly generated by DFT calculations, which typically involve 100 to 200 atoms. The cell size, orientations, and number of atoms in the datasets are summarized in Table 2.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are based on the EAM potential available at https://www.ctcms.nist.gov/potentials/Download/2020–Farkas-D-Caro-A–Fe-Ni-Cr-Co-Al/1/FeNiCrCoAl-heaweight.setfl. This potential enables the efficient generation of large datasets, facilitating the rapid validation of the reliability of our method. The CGCNN model can be accessed at https://github.com/txie-93/cgcnn.

References

Feng, L. et al. Localized phase transformation at stacking faults and mechanism-based alloy design. Acta Mater. 240, 118287 (2022).

Vamsi, K. V., Charpagne, M. A. & Pollock, T. M. High-throughput approach for estimation of intrinsic barriers in FCC structures for alloy design. Scr. Mater. 204, 114126 (2021).

Arora, G. & Aidhy, D. S. Machine learning enabled prediction of stacking fault energies in concentrated alloys. Metals 10, 1072 (2020).

Shih, M., Miao, J., Mills, M. & Ghazisaeidi, M. Stacking fault energy in concentrated alloys. Nat. Commun. 12, 3590 (2021).

Mooraj, S. & Chen, W. A review on high-throughput development of high-entropy alloys by combinatorial methods. J. Mater. Inform. https://doi.org/10.20517/jmi.2022.41 (2023).

Li, C. N., Liang, H. P., Zhao, B. Q., Wei, S. H. & Zhang, X. Machine learning assisted crystal structure prediction made simple. J. Mater. Inform. https://doi.org/10.20517/jmi.2024.18 (2024).

Zhao, S., Osetsky, Y., Stocks, G. M. & Zhang, Y. Local-environment dependence of stacking fault energies in concentrated solid-solution alloys. NPJ Comput. Mater. 5, 13 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. A statistics-based study and machine-learning of stacking fault energies in HEAs. J. Alloy. Compd. 966, 171547 (2023).

Wen, D. & Titus, M. S. First-principles study of Suzuki segregation at stacking faults in disordered face-centered cubic Co-Ni alloys. ACTA Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2021.117358 (2021).

Vamsi, K. V. & Karthikeyan, S. High-throughput estimation of planar fault energies in A3B compounds with L12 structure. Acta Mater. 145, 532–542 (2018).

LaRosa, C. R. & Ghazisaeidi, M. A “local” stacking fault energy model for concentrated alloys. Acta Mater. 238, 118165 (2022).

Sun, H. et al. An efficient scheme for accelerating the calculation of stacking fault energy in multi-principal element alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 175, 204–211 (2024).

Song, L., Wang, C., Li, Y. & Wei, X. Predicting stacking fault energy in austenitic stainless steels via physical metallurgy-based machine learning approaches. J. Mater. Inform. https://doi.org/10.20517/jmi.2024.70 (2025).

Zhang, X., Dong, R., Guo, Q., Hou, H. & Zhao, Y. Predicting the stacking fault energy in FCC high-entropy alloys based on data-driven machine learning. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 4813–4824 (2023).

Khan, T. Z. et al. Towards stacking fault energy engineering in FCC high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 224, 117472 (2022).

Lu, T., Li, M., Lu, W. & Zhang, T. Y. Recent progress in the data-driven discovery of novel photovoltaic materials. J. Mater. Inform. https://doi.org/10.20517/jmi.2022.07 (2022).

Witman, M. D., Goyal, A., Ogitsu, T., McDaniel, A. H. & Lany, S. Defect graph neural networks for materials discovery in high-temperature clean-energy applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 675–686 (2023).

Gong, S. et al. Examining graph neural networks for crystal structures: limitations and opportunities for capturing periodicity. Sci Adv. 9, eadi3245 (2023).

Cheng, J., Zhang, C. & Dong, L. A geometric-information-enhanced crystal graph network for predicting properties of materials. Commun. Mater. 2, 92 (2021).

Kolluru, A. et al. Transfer learning using attentions across atomic systems with graph neural networks (TAAG). J. Chem. Phys. 156, 184702 (2022).

Lupo Pasini, M., Jung, G. S. & Irle, S. Graph neural networks predict energetic and mechanical properties for models of solid solution metal alloy phases. Comput. Mater. Sci. 224, 112141 (2023).

Nishio, K., Shibata, K. & Mizoguchi, T. Lightweight and high-precision materials property prediction using pre-trained Graph Neural Networks and its application to a small dataset. Appl. Phys. Express 17, 037002 (2024).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 93 (2022).

Witman, M. D. et al. Phase diagrams of alloys and their hydrides via on-lattice graph neural networks and limited training data. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 1500–1506 (2024).

Nataraj, C., Borda, E. J. L., van de Walle, A. & Samanta, A. A systematic analysis of phase stability in refractory high entropy alloys utilizing linear and non-linear cluster expansion models. Acta Mater. 220, 117269 (2021).

Nataraj, C., Sun, R., Woodward, C. & van de Walle, A. First-principles study of the effect of Al and Hf impurities on Co3W antiphase boundary energies. Acta Mater. 215, 117075 (2021).

Natarajan, A. R. & Van Der Ven, A. Machine-learning the configurational energy of multicomponent crystalline solids. NPJ Comput. Mater. 4, 56 (2018).

Cao, L., Li, C. & Mueller, T. The use of cluster expansions to predict the structures and properties of surfaces and nanostructured materials. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 2401–2413 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Element-wise representations with ECNet for material property prediction and applications in high-entropy alloys. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 253 (2022).

Farkas, D. & Caro, A. Model interatomic potentials for Fe–Ni–Cr–Co–Al high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. 35, 3031–3040 (2020).

Lupo Pasini, M., Karabin, M. & Eisenbach, M. Transferring predictions of formation energy across lattices of increasing size*. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 5, 025015 (2024).

Zhang, J., Ma, S., Xiong, Y., Xu, B. & Zhao, S. Elemental partitions and deformation mechanisms of L12-type multicomponent intermetallics. Acta Mater. 219, 117238 (2021).

Feng, L., Rao, Y., Ghazisaeidi, M., Mills, M. J. & Wang, Y. Quantitative prediction of Suzuki segregation at stacking faults of the γ’ phase in Ni-base superalloys. Acta Mater. 200, 223–235 (2020).

Eggeler, Y. M. et al. Planar defect formation in the γ’ phase during high temperature creep in single crystal CoNi-base superalloys. ACTA Mater. 113, 335–349 (2016).

Stewart, C. A. et al. Predicting yield stress in a nano-precipitate strengthened austenitic steel by integrating multi length-scale simulations and experiments. Acta Mater. 272, 119918 (2024).

Hasan, M. A. A., Shin, S. & Liaw, P. K. Short-range order effects on the thermodynamic behavior of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 239, 112980 (2024).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 653–658 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52371007) and the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2024J01038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization was carried out by Youheng Chen, Chen Yang, and Jiajia Han. Methodology and investigation were performed by Youheng Chen. Data curation was done by Youheng Chen and Jiajia Han. Visualization was prepared by Youheng Chen. Supervision was provided by Xingjun Liu and Cuiping Wang. The original draft was written by Youheng Chen, and review and editing were contributed by Youheng Chen, Jiajia Han, Xingjun Liu, and Cuiping Wang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to improve the readability and language clarity of the manuscript. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Han, J., Yang, C. et al. A crystal graph convolutional neural network framework for predicting stacking fault energy in concentrated alloys. npj Comput Mater 12, 47 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01915-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01915-9