Abstract

Chiral spin textures in ferromagnetic materials with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions (DMIs) have attracted significant interest in recent years owing to their potential applications in nanodevices. This work focuses on describing stable conical-helix configurations hosted in ultrathin films with DMI and perpendicular anisotropy. These states are studied for different kinds of DMIs, including symmetry classes \({\mathcal{T}}\), \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\), isotropic and anisotropic \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\), \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{n}\), \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\), and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{4}\). A parameterised analytical model of these configurations is proposed, enabling the determination of optimal parameters characterising the magnetic texture, such as the pitch vector or nucleation field. To substantiate the results, micromagnetic simulations are developed for comparison with the theoretical solutions. Numerical solutions are optimised by implementing finite-difference codes that use next-nearest neighbours and explicit Robin boundary conditions stemming from symmetric exchange and DMI. It is shown that these numerical enhancements decrease anisotropic effects in helical solutions. This study establishes a method to analyse conical-helix textures in thin-film systems with any DMI, which can be simulated with higher precision using the open-access codes developed here.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formation and stability of chiral magnetic textures in ferromagnets is an old problem that has gained significant traction in recent years. This renewed interest is fuelled by contemporary experimental observations of these textures using advanced microscopy and magnetometry techniques, and the synthesis of novel ferromagnets exhibiting Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions (DMIs), a type of chiral antisymmetric exchange coupling arising from a broken symmetry in the material1,2. The stability of helical and conical orders in chiral magnets3,4,5,6,7 is of particular interest, where the DMI favours a definite handedness or chirality in the magnetic configurations. This preferred rotation sense has consequences for the dynamics of spin waves in these states, such as the splitting of spin excitation modes8,9,10,11,12.

Based on the phenomenological deductions of Dzyaloshinskii13, Bogdanov and Yablonskii proposed different types of DMIs based on the crystallographic class of ferromagnetic materials with broken inversion symmetry14. Among the considered DMIs are the noncentrosymmetric \({\mathcal{T}}\) (tetrahedral) and \({\mathcal{O}}\) (orthorhombic) classes (in Schoenflies notation15), which arise in the cubic B20 compounds MnSi and FeGe3. These materials have been widely studied since the early development of DMI theory in micromagnetics16,17,18,19,20,21. Because the interaction arises in the whole bulk crystal structure, it is now referred to as bulk DMI. Recent developments have found that bulk DMI can be induced in a broad class of crystals22 and even in noncentrosymmetric superlattice arrangements23. Also included in the list of crystallographic classes is the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) type, with n > 2, whose mechanism coincides with the antisymmetric exchange found at a ferromagnet/heavy metal interface24,25,26,27. With the flourishing of research on low-dimensional systems, including the design of multilayered structures with mixed materials, this kind of DMI has been studied substantially, and is currently known as interfacial DMI27,28,29,30,31,32. Other point groups of asymmetric crystals leading to particular forms of DMI, include the classes \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\)33,34,35, \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{4}\)21,33, \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\)35,36,37,38, \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{n}\)28, and \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\)27,28,29,30,31,32 and anisotropic39.

Depending on the nature of the interface and the symmetry of the underlying materials, a large family of DM materials emerges, which can be described using a DM tensor Dijk whose components arise from the symmetry of the crystal, as supported by Neumann’s principle40,41. The DMI can also involve boundary effects42,43,44,45. Similarly to the case of the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) class, other DMI types arise at interfaces with specific atomistic crystal lattices, such as a bcc(110) surface found in Fe on W(110) layers. These classes of DMI have been investigated through symmetry arguments26,29, and lately from a modern perspective39. It has been demonstrated how an anisotropic DMI can be induced in crystals belonging to any symmetry class if they are under the influence of strain fields46, as demonstrated later in centrosymmetric LaSrMnO3 exposed to graded strain47. Standard forms of DMIs are described by energy terms proportional to first-order spatial derivatives of the magnetisation, known as Lifshitz invariants (LIs)13,14,48. A theory framework to describe DMIs that cannot be expressed solely in terms of Lifshitz invariants has been proposed, predicting chiral magnetic states in DMI materials where LIs terms are forbidden, and where spin interactions of fourth order in the magnetisation contribute to the DMI35,49. However, this new formalism still requires determining appropriate magnetic parameters for non-Lifshitz-invariant terms that can be compared to experimentally observed configurations.

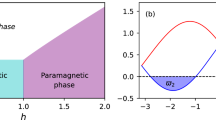

Multiple works have shown that magnetic materials exhibiting DMIs of type \({\mathcal{T}}\) (bulk) and \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) (interfacial) exhibit stable complex magnetic orderings, including helical, conical, bimeron, skyrmion, antiskyrmion, toron, and hopfion textures50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. Helices, in particular, are fundamental orderings that constitute the ground state of a system with only competing exchange and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya energies21, which determine a helical length scale. These modulations are affected differently by dipolar interactions depending on the DMI type28. Under the influence of an external field, a conical spiral propagating along the field direction becomes the lowest energy configuration below a critical saturating field. Simple models have been used to predict the period and nucleation field Hn at which the conical-helix magnetic texture emerges from saturation16,17,18,19,20,66. The pitch vector q and the cone angle θ characterise the helical magnetisation texture, where its magnitude (q) is proportional to the DMI strength D and gives the helix period λ ∝ 1/D. At the same time, the type of DMI uniquely determines the nonzero tensor elements Dijk and thus the orientation of the pitch vector with the applied magnetic field H66. For bulk DMI, q and H are parallel. For interfacial DMI, they are perpendicular, while for the DMI type arising in \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry, which has two DMI constants in a plane, D1 and D2, q points at an angle according to the ratio among them14,33,34, as shown in Fig. 1 which illustrates a helix oriented at an angle φq respect to the in-plane magnetic field.

It has been demonstrated that the formation of the periodic order relates to the spin-wave instability of the homogeneous state67,68,69. When the magnetic field is reduced from saturation, a second-order phase transition occurs as the spin-wave frequency approaches zero at a critical field that coincides with the helix’s nucleation field. The minimum frequency in the dispersion occurs at a finite wave vector that matches the helical pitch vector70. Therefore, the instability threshold of the magnonic excitations coincides with the formation of the spin texture, where the underlying mechanism involves the softening of spin-wave modes (also known in the literature as Goldstone magnons) and subsequent crystallisation into a magnetically ordered state in the film70,71,72. In thin films, the competition between the dipolar and perpendicular anisotropy fields critically affects the nucleation of the conical-helix textures, which is reflected in the change of the dynamic magnetisation orbit from circular to elliptical as the anisotropy/dipole quality factor \(Q=2K/{\mu }_{0}{M}_{s}^{2}\) deviates from unity, where K is the perpendicular anisotropy strength and Ms the saturation magnetisation70. These concepts are further developed in the present study to include finite planar films with unconventional Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya couplings, which are expected to exhibit conical-helix states36,37.

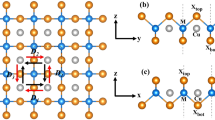

Micromagnetic simulations based on finite differences have been an optimal computational tool for modelling nano- to micro-scale ferromagnetic systems with planar geometries. This numerical method usually discretises the micromagnetic fields into a regular rectangular lattice of cells that can be parallelised, where the demanding calculation of the demagnetising field can be optimised using Fourier methods. Standard micromagnetic codes usually describe the symmetric exchange energy and field using three-point central finite differences of second-order accuracy in the mesh spacing, which, in three dimensions, is equivalent to using six neighbours per mesh site to calculate second-order derivatives. An early study73 discussed higher-order discretisation schemes for computing the symmetric exchange interaction, where the associated Neumann boundary condition is considered, which are implemented in the well-established OOMMF code74. Nevertheless, in practice, it has been customary to utilise the six-neighbour approximation, where the calculation error has been sufficient to describe several magnetic phenomena. Later implementations of the asymmetric-exchange DMI in different codes have followed the same approach, where MuMax375 was the first to explicitly consider boundary conditions, using a linear extrapolation of the magnetisation near edge sites. Recently, Müller76 has explored, using higher-order finite differences, a systematic approach to improve the accuracy at the bulk and boundaries, applying it to describe effects such as skyrmion strings77 and singular Bloch points78. Formulating this method is not trivial, as DMI imposes additional boundary conditions on the exchange field, resulting in mixed Robin boundary conditions. On the other hand, declaring these edge conditions can be circumvented by considering free spins at the boundaries. To address the lack of openly available higher-order finite difference micromagnetic implementations, and test their numerical precision in the simulation of helical textures, in the present work, open-source 12-neighbour finite-difference extensions are developed for the OOMMF74 and Ubermag79 codes, for the calculation of exchange and DMI, and for multiple DMI symmetry classes. The accuracy of these extensions is tested at the boundaries of a one-dimensional state, demonstrating that errors can be significantly reduced, enabling the highly accurate simulation of systems using larger mesh cells with a smaller memory footprint. It is further proved that these higher-order schemes reduce the artificial anisotropies arising in helical solutions due to the finite-difference meshing.

In summary, this work theoretically analyses helical states for different kinds of DMI in thin films, describing magnetic materials with various noncentrosymmetric crystal structures and thin ferromagnetic films coupled to a heavy metal. The theory allows the calculation of nucleation fields for conical-helical order, which are found for every type of DMI, beyond the standard interfacial and bulk types. The theoretical results are compared with micromagnetic simulations in finite-sized systems, with improved accuracy for the calculation of DMI and exchange. Discrete jumps are observed in the pitch-vector magnitude and the helix period, both in the simulations and the theoretical model. Since edge effects are not considered in the latter, the present study attributes this discrete behaviour to the nature of the DMI itself. Simulations are based on finite differences, and open modules are developed, tested, and analysed in this work, using higher-order finite-difference stencils. The newly developed codes improve the accuracy for the simulation of helical textures, enabling the study of more complex magnetic configurations and magnetic phenomena in nanomagnets with exotic DMI classes.

Results

Micromagnetic model

Helical textures are investigated in ultrathin ferromagnetic films with different types of DMI, and including dipolar interactions, surface anisotropy, and exchange coupling. Previous models have considered an in-plane field applied along y, such that after saturating the sample and reducing the field, a conical-helix texture, akin to a spin wave, starts forming66,70. Below a critical (nucleation) field Hn, a noncollinear texture, dependent on the DMI type, is nucleated. This field coincides with the spin-wave instability threshold, at which the frequency vanishes due to the incoming texture. To describe this process, a one-dimensional modulation model is proposed using the magnetisation field M(r) in the micromagnetic limit, as

This equation employs a phase angle ψ, such that for Q < 1, i.e., when dipolar demagnetisation dominates, ψ = π/2. Alternatively, for Q > 1, when normal anisotropy dominates, ψ = 0. Other parameters characterising the conical-helix are the in-plane pitch vector \({\bf{q}}=q({\sin} {\varphi}_{q},{\cos} {\varphi}_{q},0)\), at an angle φq with the applied field H; the cone angle θ; and the nucleation field Hn at the onset of the conical-helix formation. These quantities are obtained by minimising the free energy for each DMI type. The calculation of all energy terms is performed for a volume \({\rm{V}} = {\rm{L}}_{{\rm{x}}} {\rm{L}}_{{\rm{y}}}{\rm{d}}\), where \({\rm{L}}_{{\rm{x}}}\), \({\rm{L}}_{{\rm{y}}}\) are the film size lengths, and \({\rm{d}}\) is the film thickness, shown in detail in the Supplementary Material, allows obtaining the nucleation fields using the condition (∂2ε/∂θ2)∣θ=0 = 0. Setting φq = π/2 (or q = qx), which minimises the DMI for the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetry class, the nucleation field is

where the first term comes from interfacial DMI, the second from Exchange with \(\rm{A}\) the exchange constant, the third from perpendicular anisotropy, and the last two terms from dipolar coupling. This nucleation field at the onset of the conical-helix formation agrees with Eq. (8) in ref. 70 in the limit qL ≫ 1. As the film thickness decreases, qd ≪ 1, and the dipolar term reduces to a local anisotropy. As the dipolar interaction is considered in its nonlocal form, the quality factor depends on the pitch vector and the DMI symmetry. For the symmetry class \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\), where the pitch vector is perpendicular to the field, in the limit qLx,y ≪ 1, the nonlocal quality factor is given by

which matches the common expression of the quality factor \(Q=2K/({\mu }_{0}{M}_{s}^{2})\) in the ultrathin film limit. For the \({\mathcal{T}}\), \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\) and \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{n}\) symmetries,

For the symmetry classes with two or more DMI strengths, \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{4}\), the expressions for the nonlocal Qnl cannot be obtained in a closed mathematical form.

The DM energy expressions for every symmetry class are specified in Table 1, and their corresponding nucleation fields are specified in the Supplementary Material. The similarity of the Lifshitz invariants of the energy densities wdm for certain classes is reproduced in the energy term Edm for the conical-helix. For instance, classes \({\mathcal{T}}\) and \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\) include similar quantities, but with an opposite sign in the term proportional to qx. From the literature, it can be seen that this negative sign in \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\) differentiates the formation of Bloch skyrmions in \({\mathcal{T}}\) class materials from reported anti-skyrmions in \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{2d}\) crystals36,37.

The other symmetry classes preserve the same structure for the conical-helix energy, interchanging the qx,y components of the pitch vector. Unconventional symmetry classes include the types \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{n}\), \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{4}\), which have two or even three DM constants. In particular, for \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\), its energy expression is a combination of the \({\mathcal{T}}\) and \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) classes because in a thin film regime, the effect of out-of-plane derivatives in \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{xy}^{z}\) is discarded. The \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry exhibits a nucleation field (see Supplementary Material) that has a similar structure to the interfacial DMI case, but including the components of the pitch vector qx and qy that depend on D1 and D2.

Helical states in thin films

Minimising the total energy and analysing the orientation and magnitude of the helical pitch vector as a function of the film size for different symmetries produces different pitch-vector angles, as shown in Table 1. For bulk DMI (\({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry) φq = 0, and for interfacial DMI (\({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\)) φq = π/2, which has been proved in refs. 66,70. In the case of the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry, the pitch vector points in a direction given by \({\varphi }_{q}={\tan }^{-1}({D}_{1}/{D}_{2})\), depending on the relative magnitude of the two DMI constants that characterise this symmetry, a result that is consistent with previous works14,33,34.

Once the orientation of the pitch vector is known, their magnitudes can be obtained by minimising the total energy with respect to q for different film lengths L. The total energy for the symmetry class \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) is displayed in Fig. 2a, where it can be seen that for most of the values of L, there is a single well-defined energy minimum. At the same time, for L = 1000 nm, two possible values for the pitch vector minimise the degenerated energy, indicating that the wavelength of the helical structure oscillates and undergoes a discontinuous transition between the two q values. This is shown in the inset of Fig. 2b, where the minimised pitch vector is calculated as a function of L, with the coloured dots indicating the value plotted in Fig. 2a. It is found that the oscillation of the helix pitch vector results mainly from the effect of the DMI in a finite square film, which is discussed in the following by examining the pattern of the wavelength curve. In Fig. 2b, the horizontal black line represents the average of the oscillating pitch vector (blue line) \(\overline{q}\), which is significantly close to the value of the bulk solution, q0 = D/(2A), obtained considering exchange and DMI only. The results converge to this average value for larger film lengths, which coincides with those obtained for infinite films70. The oscillation period is approximately equal to the average wavelength \(\overline{\lambda }=2\pi /\overline{q}\) of the conical-helix (inset of Fig. 2), and is inversely proportional to the strength of the DMI. This behaviour is observed for all symmetries.

a Energy of a helical texture as a function of the pitch vector q for different film sizes L considering a \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetry with D = 1.5 mJ/m2 and Q = 0.92. b Pitch vector as a function of the film size (blue curve). The black line represents the average value \(\overline{q}\), and the purple line represents the bulk solution, q0 = D/(2A), accounting for exchange and DMI. The inset shows a zoomed-in view of a shorter range of the film length, where the coloured dots depict the values obtained for the corresponding L values used in (a), and \(\overline{\lambda }\) is the average period of the oscillation obtained from \(\overline{\lambda }=2\pi /\overline{q}\).

The wavelength of the helical textures for symmetries \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\) is plotted as a function of the film length in Fig. 3a, b, where analytical and simulation results are compared. Additionally, the number of wavelengths fitting into the sample is shown in Fig. 3c, d. These quantities are obtained after calculating the phase ψ, obtained by solving the minimum condition ∂ε2/∂ψ2∣ψ=0,π/2 > 0, where two possible values of the wavelength that minimise the energy are achieved. These values depend on the competition between superficial anisotropy and dipolar coupling given by the limiting quality factor Q for qd → 0. For symmetry classes \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\), the blue curves obtained with the model (Fig. 3a–d) deviate from the simulation data (stars and filled dots), and exhibit jumps that differ in size depending on the DMI type. For the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) case, a quality factor Q = 0.92 is chosen, which corresponds to a nonlocal value of \({Q}_{nl}^{\perp }(\overline{q})=0.98\) [see Eq. (3)] using the average pitch vector magnitude. The reason is to avoid a sharp transition at \({Q}_{nl}^{\perp }=1\) that changes ψ = π/2 to 0. In this regime, when \({Q}_{nl}^{\perp }\to 1\), the surface anisotropy energy in the calculations is close to cancelling the dipolar coupling, and, consequently, the energy dependence on the sample length is lost. In contrast, for the symmetry class \({\mathcal{T}}\), its different dipolar coupling expression (which depends on a different φq) changes the behaviour of Q, thereby producing a \({Q}_{nl}^{\parallel }(\overline{q})=0.95\), which is farther away from the critical point than for the interfacial DMI. As a result, the fit of the \({\mathcal{T}}\) class analytical curve to the simulation data is more optimal. In the case of the simulations, the anisotropy value does not affect the results as significantly as for the theoretical model, and ψ does not change critically close to Q = 1. Therefore, simulations exhibit a more stable behaviour because the phase is fixed by the boundary conditions, which are accounted in the numerical calculations.

In (a–d), the blue line represents the theory predictions, the black dots indicate the mumax+ simulation results, and the green stars symbolize the OOMMF simulation results. a and c correspond to the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetry, with the dashed lines denoting integer multiples of the average wavelength \(\overline{\lambda }\). b and d correspond to the \({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry. a and b show the wavelength as a function of film length for their respective symmetries, while c and d display the number of wavelengths as a function of film size for the corresponding symmetries. e illustrates how the helical texture accommodates to an increasing sample length L, where roman number labels correspond to the states marked in the \({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry class panels (b) and (d).

From the theoretical model, Fig. 3a, d indicates that jumps of the helical wavelength appear at sample sizes \(L=p\overline{\lambda }-\overline{\lambda }/4\), where p is an integer and \(\overline{\lambda }\) the average wavelength. These critical L values represent a threshold size where the energy becomes degenerated between two states with either a semi-integer or integer number of wavelengths. The DMI causes these discontinuities, and to explain its effect, a simplified representation of the helix, as the sample size L increases, is depicted in Fig. 3e for the \({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry class. Every snapshot illustrates the cases marked in the theoretical curve (Fig. 3b), where both the size of the sample L and the helical wavelength λ are specified. Over an increment of the sample size close to a full wavelength (cases I-III in Fig. 3e), the sample’s helical wavelength will adapt by slightly increasing in size. This means that the rotation between neighbouring spins is smoother, i.e., they align more parallel, which is preferred by the symmetric exchange and opposed by the DMI. When L reaches a critical value to accommodate an additional wavelength (case IV), the magnetisation abruptly changes to favour the DMI energetically. The influence of dipolar and anisotropy fields is not significant in this process, as evidenced by removing any of them from the model and observing the same results. In contrast to the analytical model, the simulation data exhibit jumps at integer multiples of the average wavelength. This discrepancy can be attributed to the edge effects in the simulations, where the spin orientations are determined by the exchange boundary conditions, which are challenging to implement in a realistic theoretical model.

A possible extension of the present formalism is to describe skyrmion solutions using a triple-q model, by superimposing three helices at 120∘. However, it will be necessary to verify the effectiveness of this approach against confinement effects.

Nucleation fields for the helical states

The nucleation field of a given reversal path is defined as the field value at which the saturated state becomes unstable. The most relevant nucleation field is the largest among the possible reversal modes, since once the nucleation of a magnetisation texture is triggered, the system will follow this transition path, losing the possibility to access other reversal modes80. This mechanism is instrumental in predicting the reversal mode that minimises the energy (and maximises the nucleation field)81,82,83. Mathematically, for the simplest case of a reversal path that depends on a single parameter, such as θ for the conical-helix texture, the nucleation field Hn can be obtained from (∂2ε/∂θ2)∣θ=0 = 0. Then, employing Eq. (2) for the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetry, the magnitude of the pitch vector can be determined by identifying the maximum value of the nucleation field as q varies. In Fig. 4, Hn is plotted as a function of q for different sample lengths L. The value of q that maximises the nucleation field coincides with that minimising the energy, a result that is consistent with the definition of the effective field: H = −(1/μ0)δε/δM. For L = 1000 nm, the curve exhibits two maxima corresponding to the pitch vectors at which the helix wavelength jumps in Fig. 3.

In the case of the less-reported DMI associated with the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry class, the wavelengths do not exhibit the jumps shown in Fig. 3 for the bulk and interfacial DMIs. As this symmetry class includes two DMI constants, the nucleation field is examined in detail. By fixing the value of D2, Fig. 5a–c shows phase diagrams of the magnetic state for Q = 1.1 and parameterised by the field strength and D1, and for three specific D2 magnitudes. For sufficiently strong fields, the system remains field-polarised. By decreasing the field, the magnetisation will nucleate to either an out-of-plane configuration (since Q > 1) via coherent rotation, or to a conical-helix texture, depending on a critical D1 value, D1c, below which the coherent reversal is energetically preferred (to the left side of the dashed vertical line in Fig. 5a, b). For the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) DMI type, the pitch vector direction is given by the arctangent of the ratio between the two DMI constants [\({\varphi }_{q}={\tan }^{-1}({D}_{1}/{D}_{2})\)]. Hence, the φq angle is depicted through the gradient colour in the coherent rotation region, as the DMI constants vary. In Fig. 5a, where D2 = 0, the direction is fixed at φq = π/2 for all values of D1, corresponding to the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) case. For both D2 = 0.5 mJ/m2 and D2 = 1 mJ/m2, values of D1 near zero yield φq ≈ 0, and φq increases progressively with D1, up to a value of φq ≈ 4π/9 for D2 = 0.5 mJ/m2, and φq ≈ 7π/18 for D2 = 1 mJ/m2. This transition is indicated by the higher nucleation field of the coherent reversal process for D1 < D1c. In contrast, for Q < 1, the system would be driven into an in-plane configuration owing to the stronger effect of the dipolar field. Accordingly, nucleated-state phase diagrams as a function of Q and D1 are depicted in Fig. 5d–f, where, above a critical D1 value, a conical-helical texture is nucleated after field sweep from a saturating field. At the limiting Q = 1 value (where anisotropy and dipolar field energies are equivalent), it can be seen that a conical-helix is always formed because its nucleation field is always larger, as in the case of Fig. 5c. Interestingly, by increasing the D2 value, a gap arises around this critical Q, which allows tuning the region of conical-helix formation.

The upper-row panels show the magnetic states after a field sweep from a saturating field, as a function of the applied field and DMI strength D1, for different values of D2 (in every column) and Q = 1.1. In (a) and (b), a D1c value determines the critical constant D1, above which the nucleation field for a conical-helix configuration is larger than that of a coherent rotation (given by the horizontal line). d–f The lower-row panels show phases of nucleated states (below a nucleation field, as computed in the upper-row plots), in the D1 versus Q diagram, for three values of D2. The phase regions are delimited by curves of the critical constant D1c as Q changes. Colouring in conical-helix phases indicates the associated pitch vector direction.

Further simulations were performed to compare the nucleation field and helix angle φq of the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) crystal class against the theory. In this case, a perfect agreement of the nucleation field was observed. The helix angle was computed using the peaks of a two-dimensional Fourier transform of the helix pattern after nucleation. Calculations via mumax+, using the 1 nm-sided discretisation cells, were consistent with the model down to zero magnetic fields. In contrast, the angles computed using OOMMF exhibited an excellent agreement just below the nucleation field. They slightly deviated from the predicted values when approaching zero fields for both the same and larger cell sizes. It was observed that during this process, the helix rotates at weak fields to minimise the demagnetising energy. The discrepancy between the codes is primarily due to the larger default error tolerance in mumax+ when computing the demagnetising tensor for the stray field calculation. Specifying the same error tolerance set by default in OOMMF, mumax+ solutions successfully reproduce the edge effects. Further details of these results are shown and discussed in the Supplementary Material.

Numerical methods for DMI

For this study, codes to simulate DMI for all the crystal classes shown in Table 1 have been developed as new modules for the OOMMF software and the micromagnetic platform Ubermag79,84. The calculations in these modules employ a 12-neighbour finite-difference approach73, which involves a 5-point central-difference approximation of the first- and second-order derivatives for each Cartesian direction. The numerical computation combines both exchange and DM interactions within a single module and uses free boundaries (see Methods) for spins located one or two sites from the edges. The following subsection demonstrates how these new implementations improve the simulation of the magnetisation at the sample boundaries, analysing a one-dimensional uniform state. To further validate the 12-neighbour implementation, the motion of a current-induced skyrmion in a nanotrack was studied, following the work of Sampaio et al.51. The higher-order finite-difference simulations reproduced their results and achieved higher accuracy when computing the skyrmion velocity as a function of current density, as discussed in detail in the Supplementary Material. Investigating more complex topological textures is beyond the scope of this work. Thus, in the following, the focus is kept on helical textures. Accordingly, the final subsection discusses how artificial anisotropies arise in helical solutions from the finite-difference discretisation and the role of the new codes in reducing these numerical effects.

Improving simulations at the boundary

In addition to the 12-neighbour codes with free boundaries, an explicit implementation of the Robin boundary condition at the sample surfaces was developed for interfacial DMI. This is given by the combined boundary conditions of the exchange and DMI in the variational minimisation of the micromagnetic energy functional85. To accurately represent these Robin boundary conditions, it is necessary to consider a fictional mesh site sitting exactly at the mesh edges73,76, and to decide on the (likely asymmetric) finite-difference schemes for the mesh sites near the boundary. This implementation is discussed in detail in Methods and in ref. 76.

The accuracy of the numerical methods implemented here is tested by analysing the error at the boundary of a one-dimensional system of length ℓ with only exchange and interfacial DM couplings. The fifth column in Table 1 gives the corresponding boundary condition. The simulation error is compared to an analytical kink-soliton solution at the edge of the sample after variational minimisation of the system’s energy functional86. Equivalently, a semi-analytical solution can be obtained via the shooting method87,88. Since edge mesh points do not lie exactly at the boundary, a third-order spline interpolation of mz is used to extrapolate the magnetisation to the edges. In Fig. 6, it is shown that the 12-neighbour numerical schemes are nearly of order \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{-3})\) in discretisation error concerning the number of discretisation cells N = ℓ/h used for the meshing of the system. This trend is clearly evident for explicit Robin conditions and supports the formulation of the procedure described in Methods. For free boundaries, the 12-neighbour method loses accuracy after a sufficiently large number of cells, where it matches the \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{-2})\) trend of the commonly used 6-neighbour approximation. Nevertheless, the free-boundaries 12-neighbour method is highly precise for coarse-mesh discretisations, h ≳ 2 nm, where it can achieve an order-of-magnitude improvement in precision compared to the 6-neighbour approach. The solutions obtained via OOMMF are compared to codes optimised in graphics processing units, amumax89 and mumax+90, which implement a linear approximation of the spins at the virtual mesh sites next to the boundary, and apply the Robin conditions for the inner mesh site closest to the boundary. This approximation closely matches the free boundary approach for six neighbours. A strong feature of the mumax+ code is that any DMI, as discussed in this work, can be specified via numerical tensor forms associated with Lifshitz invariants (see Supplementary Material). This implementation can potentially be extended in the future to achieve higher accuracy of the solutions at the sample edges.

The system includes exchange and DM interactions only. The error is computed as a function of the number of mesh discretisation sites N = ℓ/h, where h is the distance between mesh sites. The numerical solution is compared to a kink-soliton solution at the sample edge86. The mz curve is extrapolated to x = − ℓ/2 and x = ℓ/2 since the mesh points at the domain extrema do not lie exactly at the mesh boundaries. The one-dimensional system is simulated using different approximations of the exchange interactions: 6-neighbour (6 Nb) and 12-neighbour (12 Nb) stencils, and free (no label) or Robin boundary conditions (BC), as well as various finite-difference micromagnetic codes, as specified in the legend. The faded dashed line serves as a reference for inverse cubic scaling of the error with the number of mesh points.

Finite difference anisotropy

To numerically solve the continuous micromagnetic equations, the magnetisation must be discretised. This discretisation inherently breaks the symmetry of the micromagnetic equations, introducing numerical errors known as discretisation anisotropy91. In finite difference simulations, the system is discretised onto a cuboidal grid, enabling derivatives, and thus Lifshitz invariants, to be calculated via finite difference approximations. Consequently, this discretisation impacts all energy terms involving spatial derivatives, including the exchange and DMIs. For example, when employing a six-neighbour finite-difference approximation for an infinite sample and the above ansatz (This means, for a first order derivative at mesh site, \(i,{\partial }_{\alpha }{m}_{i}\approx (1/(2{h}_{\alpha }))[{m}_{i}({\bf{r}}+{h}_{\alpha }{\widehat{x}}_{\alpha })-{m}_{i}({\bf{r}}-{h}_{\alpha }{\widehat{x}}_{\alpha })]\), and for a second order derivative, \({\partial }_{\alpha \alpha }{m}_{i}\approx {h}_{\alpha }^{-2}[{m}_{i}({\bf{r}}+{h}_{\alpha }{\widehat{x}}_{\alpha })-2{m}_{i}({\bf{r}})+{m}_{i}({\bf{r}}-{h}_{\alpha }{\widehat{x}}_{\alpha })]\), with \(\alpha \in {x,y,z}\), and m is given in Eq. (1)), the terms in the mean DMI energy density undergo the following transformation:

where hη is the discretisation cell size along the η = x, y axis. Specifically, for the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) crystallographic class [Eq. (11)], this discretisation modifies the DMI energy density term from:

which introduces artificial discretisation anisotropy by underestimating the effect of the DMI pitch vector q in the x direction.

Similarly, for the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) crystallographic class, the transformed DM energy becomes:

Increasing the finite-difference stencil size from 6 to 12 points significantly reduces the discretisation error from \({\mathcal{O}}({h}^{2})\) to \({\mathcal{O}}({h}^{4})\). The resulting modified energy expression becomes:

Additionally, discretisation anisotropy can be reduced by increasing the number of cells per wavelength. A finer grid more accurately approximates continuous derivatives as the sinc function approaches unity and the discretisation length approaches zero.

Figure 7 shows the energy density for the interfacial \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) type DMI computed using eight cells per wavelength. The continuous approximation produces a periodic sine wave with an energy minimum at φq = π/2. The six-neighbour finite-difference approximation exhibits a similar overall shape but introduces significant discrepancies of up to 10% in magnitude compared to the continuous case. However, employing the twelve-neighbour finite-difference approximation substantially improves accuracy, more closely matching the continuous approximation curve and significantly reducing discretisation errors.

Discussion

In the present work, conical-helix magnetic textures in thin ferromagnetic films with asymmetric exchange interactions (i.e., DMIs) have been described by defining a suitable magnetisation ansatz. This model contains a series of parameters, including the helix pitch vector and cone angle, that can be determined by minimising the micromagnetic energy functional for the ultrathin planar geometry considered here. Moreover, this technique enables the calculation of the nucleation field of a conical-helix texture when a magnetic field is decreased after saturating the sample. The obtained helix pitch vector and nucleation field can be compared with the critical wave vector and critical magnetic field at the threshold of the spin-wave instability in the saturated state of thin magnetic films, indicating texture formation below the critical field.

The method employed in this study has been applied to systems with different crystal symmetry classes, which are described by DMI expressions given by different combinations of Lifshitz invariants. This analysis allowed the comparison of the helix parameters obtained from theory and simulation for all these symmetry classes. The model fully accounts for dipolar coupling in the thin-film regime, providing an accurate description of these nonlocal interactions, which are often difficult to formulate mathematically. Therefore, the developed formalism serves as a solid foundation for the micromagnetic modelling of helical spin textures in thin films with any type of antisymmetric exchange interactions. Furthermore, spin wave modes, which encode the properties of helical textures, can be obtained via linearisation of the LLG equation.

The theoretical model was validated against micromagnetic simulations using the novel finite-difference code mumax+ and the well-established code OOMMF to support the results. Although the analytical model does not account for finite-size effects at the sample boundaries, excellent agreement was observed between the analytical solutions and the numerical calculations. A series of code implementations was developed for the OOMMF platform to simulate all the different DMI classes shown in this work. These codes use high-order finite differences, and it has been demonstrated in detail how they can reduce anisotropy artifacts arising from the discretisation method. In addition, they improve the accuracy of the magnetisation behaviour at the sample boundaries. These modules are fully open and can be extended in the future to support a broader set of symmetry classes and finite difference schemes.

Methods

Calculation of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya energy

Using the magnetisation ansatz of Eq. (1), the total energy, Etot = Eex + Ean + Eze + Edip + Edm, can be calculated analytically for each DMI symmetry class. In this expression, Eex is the exchange interaction, Eze the Zeeman coupling due to the external magnetic field, Edip the dipolar interaction, Ean the superficial (perpendicular) anisotropy, and the last term represents the DMI. For simplicity, we use a normalised energy expression \(\varepsilon =E/({\mu }_{0}{M}_{s}^{2}V)\), where V = LxLyd is the volume of the film, with Lx and Ly as the film side lengths, and d as the film thickness. In the micromagnetic limit, the energy due to the DM coupling is Edm = ∫wdm dV, where wdm is the energy density. Depending on the crystal symmetry, wdm is described by a specific combination of Lifshitz invariants35,48, which are defined as

For example, the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetry with n > 2 leads to interfacial DMI27,28,29,30,31,32, where the energy density is

By integrating the energy density within the volume, and then normalizing it by \({\mu }_{0}{M}_{s}^{2}V\), it is obtained

Here, the first term originates from \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{yz}^{y}\), while the second one arises from \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{xz}^{x}\), and depends on

where \({\text{sinc}}(x)=\frac{\sin x}{x}\) is the cardinal sine function. As expected, the DM energy is proportional to qD and depends on the angle between q and H, which determines the components of the pitch vector \({q}_{x}=q\sin {\varphi }_{q}\) and \({q}_{y}=q\cos {\varphi }_{q}\). This energy term also depends on the phase ψ and cone angle θ. Notice that if the applied field is higher than the nucleation field \({H}_{n}^{i-dm}\), then θ = 0 and the magnetisation is saturated. The calculation of the other energy terms is performed in the Supplementary Material.

Boundary conditions

The analytical model presented here neglects boundary effects resulting from exchange and DM interactions. Due to the nonlocal dependence of the dipolar energy on the magnetisation, incorporating this term into the micromagnetic energy functional makes the minimisation problem highly nontrivial87. Therefore, a parameterised model for the magnetisation is assumed, which allows finding an energy minimum by varying the model parameters, albeit without accounting for edge conditions. Accordingly, the model in this study is valid for helices in an infinitely extended sample but becomes less accurate near the edges in a confined system. Several formalisms modelling boundary conditions have been proposed for quasi-uniform magnetic textures (uniform in the bulk), where it is possible to obtain a Sine-Gordon differential equation that effectively describes the spin canting at the edges86,92,93,94. Nonetheless, this kind of description becomes significantly more complex when the system hosts a confined helix, where the helical length is adapted to the system size. To validate the proposed helical solutions, they are compared with numerical simulations in extended samples in the Results section. Because simulations include boundary effects, numerical techniques are analysed to optimise simulation accuracy, thereby improving the magnetisation solution at the sample boundaries and reducing anisotropic effects on helical energy when using finite differences.

Micromagnetic simulations

Micromagnetic simulations were performed using the GPU-accelerated package mumax+ 90, and the solutions were validated using the OOMMF software74 via the micromagnetic platform Ubermag79,84. The simulated system consists of a square film of size L × L with a thickness of 1 nm. The discretisation cell is defined with a cubic volume of 1 nm3 for mumax+, and a larger cell size of 2.5 nm in the xy plane for OOMMF. Magnetic interactions include symmetric exchange, DMIs (\({\mathcal{T}}\), \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\), and \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetries), dipole-dipole interactions, uniaxial anisotropy along the z-axis, and the Zeeman interaction. Free boundaries are used in both codes. Calculation of exchange interactions utilises a 6-neighbour stencil in mumax+, whereas a 12-neighbour stencil is implemented in OOMMF. Energy minimisation is performed using the steepest descent method with a modified Barzilai-Borwein step scheme in mumax+, and OOMMF follows a conjugate gradient scheme with a Fletcher-Reeves direction update. For further details, refer to Numerical methods for DMI and the Supplementary Material. Simulation scripts can be found in the repository associated with this paper95.

The model magnetic parameters correspond to those of Permalloy70, including a saturation magnetisation Ms = 658 kA/m, exchange stiffness A = 11.1 pJ/m, uniaxial anisotropy K = 0.25 MJ/m3 and an external field applied along the y − direction. These parameters define a quality factor of Q = 0.92. For \({\mathcal{T}}\) and \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{nv}\) symmetries, the DMI strength was set to D = 1.5 mJ/m2. In contrast, for the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry, which involves two distinct DMI values, one was varied between 0 and 3 mJ/m2, while the other was kept fixed. The same parameters were used in the analytical calculations to enable a direct comparison with the micromagnetic simulations. The simulations are based on a gradual decrease in the magnitude of the external magnetic field, starting from a saturated state at 1 T and decreasing to zero in steps of 5 mT. At every field stage, the energy is minimised. This field sweep passes through the critical field at which the conical-helix texture begins to nucleate. At zero field, the texture period is extracted, enabling the calculation of the pitch vector magnitude (q) for each system size L, ranging from 900 nm to 1100 nm in steps of 10 nm. This procedure is carried out for both bulk and interfacial DMI. In the case of the \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{n}\) symmetry, the system size is kept fixed, and the critical field is determined. During the nucleation process, and down to zero field, both the pitch vector magnitude (q) and its orientation with respect to the external field direction (φq) are evaluated.

Finite difference implementation

The Robin boundary condition for interfacial DMI is given by

where q0 = D/(2A) and the DMI tensor is

The following discussion will focus on the leftmost mesh site in the x-axis. For a system defined in the domain [0, ℓ] in the x-direction, a finite-difference mesh discretisation of N-sites means mesh sites are separated by a distance h = ℓ/N, with the first mesh site (at the centre of the mesh cell), indexed by i = 0, located at a distance x0 = h/2 from the sample boundary. The implementation for free boundaries is straightforward, as it is set m−2 = m−1 = 0, if we index the virtual sites to the left by negative integers. Similarly for the next site, m1, where it is set m−1 = 0.

To explicitly implement the Robin conditions, this paper uses an asymmetric central finite-difference scheme for the m0 site, with one neighbour to the right and one virtual neighbour to the left. These neighbours are indexed by i = { − 1/2, 1}. The virtual mesh site with coordinates x−1/2 = 0 is located exactly at the left boundary of the system73,76. Its derivative normal to the x-boundary is computed as the finite difference,

where the prefactors to the right-hand side are − 8/3h, 3/h, and − 1/3h, respectively. The Robin condition is employed to compute the derivative term in Eq. (14), yielding an expression for the virtual site i = − 1/2 as

using the inverse of the matrix \({\mathbb{A}}=(-{q}_{0}\,{\mathbb{D}}-{a}_{-1/2}^{-1/2}{\mathbb{I}})\), with \({\mathbb{I}}\) as the identity matrix.

This approximation of the boundary point is used to estimate the first and second derivatives at the first mesh site, ∂xm0 and ∂xxm0. A similar derivation is used for the last mesh site in the x-direction and the extrema sites next to the boundaries normal to the y- and z-directions. The derivative approximations are applied to the calculation of the exchange and DMI effective fields and energy, with errors \({\mathcal{O}}({h}^{3})\). For the sites next to the first mesh site, in every direction, m1, the neighbours chosen in the approximation are i = {0, 2}, which also produces an error of order \({\mathcal{O}}({h}^{3})\). The Robin condition is not used for this site, as imposing it was found to affect the convergence of the energy minimisation. For the inner mesh sites, two neighbours per side are used (central differences with 5 points), yielding errors of \({\mathcal{O}}({h}^{4})\). A systematic derivation of these finite-difference schemes, considering the Robin boundary conditions, has been developed by Müller76, where errors can be controlled by increasing the number of neighbouring mesh sites used.

Data availability

The dataset with the simulations and data analysis of this study can be accessed in the open repository95.

References

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–255 (1958).

Moriya, T. New mechanism of anisotropic superexchange interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 4, 228–230 (1960).

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Tokunaga, Y. et al. A new class of chiral materials hosting magnetic skyrmions beyond room temperature. Nat. Commun. 6, 7638 (2015).

Qian, F. et al. New magnetic phase of the chiral skyrmion material Cu2OSeO3. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat7323 (2018).

Bannenberg, L. J. et al. Multiple low-temperature skyrmionic states in a bulk chiral magnet. npj Quantum Mater. 4, 11 (2019).

Fujishiro, Y. et al. Topological transitions among skyrmion- and hedgehog-lattice states in cubic chiral magnets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1059 (2019).

Janoschek, M. et al. Helimagnon bands as universal excitations of chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 81, 214436 (2010).

Schwarze, T. et al. Universal helimagnon and skyrmion excitations in metallic, semiconducting and insulating chiral magnets. Nat. Mater. 14, 478–483 (2015).

Ogawa, N. et al. Nonreciprocity of spin waves in the conical helix state. PNAS. 118, e2022927118 (2021).

dos Santos, F. J., dos Santos Dias, M. & Lounis, S. Nonreciprocity of spin waves in noncollinear magnets due to the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 102, 104401 (2020).

Brevis, F. et al. Toroidal moments in confined nanomagnets and their impact on magnonics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 24, 024058 (2025).

Dzyaloshinskii, I. Theory of helicoidal structures in antiferromagnets. I. Nonmetals. Sov. Phys. JETP 19, 960–971 (1964).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Yablonskii, D. A. Thermodynamically stable vortices in magnetically ordered crystals. the mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 68, 101–103 (1989).

Grenier, B. & Ballou, R. Crystallography: Symmetry groups and group representations. EPJ Web Conf. 22, 00006 (2012).

Bak, P. & Jensen, M. H. Theory of helical magnetic structures and phase transitions in MnSi and FeGe. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 13, L881–L885 (1980).

Nakanishi, O., Yanase, A., Hasegawa, A. & Kataoka, M. The origin of the helical spin density wave in MnSi. Solid State Commun. 35, 995–998 (1980).

Maleyev, S. V. Cubic magnets with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction at low temperature. Phys. Rev. B 73, 174402 (2006).

Rößler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Wilson, M. N., Butenko, A. B., Bogdanov, A. N. & Monchesky, T. L. Chiral skyrmions in cubic helimagnet films: The role of uniaxial anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 89, 094411 (2014).

Leonov, A.Twisted, localized, and modulated states described in the phenomenological theory of chiral and nanoscale ferromagnets. Dissertation, Technische Universität Dresden https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa-83823 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Topological magnetism: Materials and devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2425483 (2025).

Ham, W. S. et al. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in noncentrosymmetric superlattices. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 129 (2021).

Fert, A. & Levy, P. M. Role of anisotropic exchange interactions in determining the properties of spin-glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1538–1541 (1980).

Fert, A. Magnetic and transport properties of metallic multilayers. In Metallic Multilayers, vol. 59 of Materials Science Forum, 439–480 (Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 1990).

Crépieux, A. & Lacroix, C. Dzyaloshinsky-moriya interactions induced by symmetry breaking at a surface. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 182, 341–349 (1998).

Kuepferling, M. et al. Measuring interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in ultrathin magnetic films. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 015003 (2023).

Bogdanov, A. & Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 138, 255–269 (1994).

Fert, A., Chshiev, M., Thiaville, A. & Yang, H. From early theories of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions in metallic systems to today’s novel roads. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 081001 (2023).

Gallardo, R. A., Cortés-Ortuño, D., Troncoso, R. E. & Landeros, P. Spin waves in thin films and magnonic crystals with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions. In Gubbiotti, G. (ed.) Three-dimensional magnonics: layered, micro-and nanostructures, 121–160 https://www.crcpress.com/Three-Dimensional-Magnonics/Gubbiotti/p/book/9789814800730 (Jenny Stanford Publishing, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2019).

Borisov, V., Salehi, N., Pereiro, M., Delin, A. & Eriksson, O. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions, Néel skyrmions and V4 magnetic clusters in multiferroic lacunar spinel GaV4S8. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 53 (2024).

Li, X., Wang, Z., Chen, Z., Yu, Z. & Xu, C. Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction manipulation in multiferroic Janus monolayers. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 123 (2025).

Leonov, A. O. et al. The properties of isolated chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films. N. J. Phys. 18, 065003 (2016).

Rowland, J., Banerjee, S. & Randeria, M. Skyrmions in chiral magnets with Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 93, 020404 (2016).

Ado, I. A., Qaiumzadeh, A., Brataas, A. & Titov, M. Chiral ferromagnetism beyond Lifshitz invariants. Phys. Rev. B 101, 161403 (2020).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Magnetic antiskyrmions above room temperature in tetragonal Heusler materials. Nature 548, 561–566 (2017).

Jena, J. et al. Evolution and competition between chiral spin textures in nanostripes with D2d symmetry. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0723 (2020).

Ga, Y. et al. Anisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction protected by D2d crystal symmetry in two-dimensional ternary compounds. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 128 (2022).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Antiskyrmions stabilized at interfaces by anisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions. Nat. Commun. 8, 308 (2017).

Birss, R.Symmetry and Magnetism. Selected topics in solid state physics https://books.google.cl/books?id=Iz5RAAAAMAAJ (North-Holland Publishing Company, 1964).

Landau, L. D. et al. Electrodynamics of continuous media, vol. 8 (Elsevier, 2013).

Rybakov, F. N., Borisov, A. B., Blügel, S. & Kiselev, N. S. New spiral state and skyrmion lattice in 3D model of chiral magnets. N. J. Phys. 18, 045002 (2016).

Hals, K. M. D. & Everschor-Sitte, K. New boundary-driven twist states in systems with broken spatial inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 127203 (2017).

Mulkers, J. et al. Effect of boundary-induced chirality on magnetic textures in thin films. Phys. Rev. B 98, 064429 (2018).

Turnbull, L. A. et al. X-ray holographic imaging of magnetic surface spirals in FeGe lamellae. Phys. Rev. B 106, 064422 (2022).

Kitchaev, D. A., Beyerlein, I. J. & Van der Ven, A. Phenomenology of chiral Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions in strained materials. Phys. Rev. B 98, 214414 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Strain-driven Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction for room-temperature magnetic skyrmions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 117204 (2021).

Togawa, Y., Ovchinnikov, A. S. & Kishine, J. -i Generalized Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and chirality-induced phenomena in chiral crystals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 081006 (2023).

Ado, I. A., Tchernyshyov, O. & Titov, M. Noncollinear ground state from a four-spin chiral exchange in a tetrahedral magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 127204 (2021).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Finocchio, G., Büttner, F., Tomasello, R., Carpentieri, M. & Kläui, M. Magnetic skyrmions: From fundamental to applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 49, 423001 (2016).

Jiang, W. et al. Skyrmions in magnetic multilayers. Phys. Rep. 704, 1–49 (2017).

Cortés-Ortuño, D. et al. Nanoscale magnetic skyrmions and target states in confined geometries. Phys. Rev. B 99, 214408 (2019).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Panagopoulos, C. Physical foundations and basic properties of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 492–498 (2020).

Göbel, B., Mertig, I. & Tretiakov, O. A. Beyond skyrmions: Review and perspectives of alternative magnetic quasiparticles. Phys. Rep. 895, 1–28 (2021).

Raftrey, D. & Fischer, P. Field-driven dynamics of magnetic hopfions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 257201 (2021).

Kent, N. et al. Creation and observation of hopfions in magnetic multilayer systems. Nat. Commun. 12, 1562 (2021).

Sapozhnikov, M., Tatarskiy, D. & Mironov, V. Creating and detecting a magnetic bimeron by magnetic force microscope probe. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 549, 169043 (2022).

Camley, R. E. & Livesey, K. L. Consequences of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Surf. Sci. Rep. 78, 100605 (2023).

Kuchkin, V. M. et al. Heliknoton in a film of cubic chiral magnet. Front. Phys. 11, 1201018 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Li, S., Liang, X. & Zhou, Y. Topological spin textures: Basic physics and devices. Adv. Mater. 37, 2312935 (2025).

Cai, M. et al. Stabilization and observation of large-area ferromagnetic bimeron lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 116703 (2025).

Castro, M. et al. Bimerons as edge states in thin magnetic strips. Nano Lett. 25, 7249–7257 (2025).

Shimizu, K., Okumura, S., Kato, Y. & Motome, Y. Current-induced motion of nanoscale magnetic torons over the wide range of the hall angle. Commun. Phys. 8, 69 (2025).

Garst, M., Waizner, J. & Grundler, D. Collective spin excitations of helices and magnetic skyrmions: Review and perspectives of magnonics in non-centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 293002 (2017).

Leaf, G. et al. Dynamic origin of stripe domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 017201 (2006).

Montoncello, F. et al. Soft spin waves and magnetization reversal in elliptical permalloy nanodots: Experiments and dynamical matrix results. Phys. Rev. B 76, 024426 (2007).

Suszka, A. K. et al. Field angle dependent change of the magnetization reversal mode in epitaxial Co (0001) films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 222402 (2014).

Ríos-Venegas, C., Brevis, F., Gallardo, R. A. & Landeros, P. Dynamic origin of conical helix magnetization textures stabilized by Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 105, 224403 (2022).

Kisielewski, J., Gruszecki, P., Krawczyk, M., Zablotskii, V. & Maziewski, A. Between waves and patterns: Spin wave freezing in films with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 107, 134416 (2023).

Grassi, M. et al. Higgs and Goldstone spin-wave modes in striped magnetic texture. Phys. Rev. B 105, 094444 (2022).

Donahue, M. & Porter, D. Exchange energy formulations for 3D micromagnetics. Phys. B Condens. Matter 343, 177–183 (2004).

Donahue, M. & Porter, D.OOMMF User’s Guide, Version 2.1a0. Gaithersburg, MD (2023).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Müller, J.Magnetic Skyrmions and Topological Domain Walls. Ph.D. thesis, Universität zu Köln https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/8140/ (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Real-space observation of topological defects in extended skyrmion-strings. Nano Lett. 20, 7313–7320 (2020).

Yasin, F. S. et al. Bloch point quadrupole constituting hybrid topological strings revealed with electron holographic vector field tomography. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311737 (2024).

Beg, M., Lang, M. & Fangohr, H. Ubermag: Towards more effective micromagnetic workflows. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58, 1–5 (2022).

Aharoni, A. Introduction to the Theory of Ferromagnetism (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Usov, N. A., Chen, A. P., Zhukov, A. & González, J. Nucleation field of a soft magnetic nanotube with uniaxial anisotropy. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 083902 (2008).

Landeros, P., Suarez, O. J., Cuchillo, A. & Vargas, P. Equilibrium states and vortex domain wall nucleation in ferromagnetic nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 79, 024404 (2009).

Gutierrez-Guzman, D. F., Lizardi, L. I., Otálora, J. A. & Landeros, P. Hyperthermia in low aspect-ratio magnetic nanotubes for biomedical applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 133702 (2017).

Fangohr, H. et al. Vision for unified micromagnetic modeling (UMM) with ubermag. AIP Adv. 14, 015138 (2024).

Abert, C. Micromagnetics and spintronics: Models and numerical methods. Eur. Phys. J. B 92, 120 (2019).

Müller, J., Rosch, A. & Garst, M. Edge instabilities and skyrmion creation in magnetic layers. N. J. Phys. 18, 065006 (2016).

Rohart, S. & Thiaville, A. Skyrmion confinement in ultrathin film nanostructures in the presence of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 184422 (2013).

Cortés-Ortuño, D. et al. Proposal for a micromagnetic standard problem for materials with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. N. J. Phys. 20, 113015 (2018).

Moalic, M. & Zelent, M. Mathieumoalic/amumax: 2025.01.07 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14609867 (2025).

Moreels, L. et al. mumax+: extensible GPU-accelerated micromagnetics and beyond https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.18194 2411.18194 (2024).

Holt, S. J. R., Petrocchi, A., Lang, M., Pathak, S. A. & Fangohr, H. Discretization anisotropy in finite difference micromagnetic simulations. IEEE Trans. Magn. 61, 1–5 (2025).

Meynell, S. A., Wilson, M. N., Fritzsche, H., Bogdanov, A. N. & Monchesky, T. L. Surface twist instabilities and skyrmion states in chiral ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014406 (2014).

Raeliarijaona, A., Nepal, R. & Kovalev, A. A. Boundary twists, instabilities, and creation of skyrmions and antiskyrmions. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 124401 (2018).

Sandhoefner, S., Raeliarijaona, A., Nepal, R., Snyder-Tinoco, D. & Kovalev, A. A. Regular and in-plane skyrmions and antiskyrmions from boundary instabilities. Phys. Rev. B 104, 064417 (2021).

Cepeda-Arancibia, M. et al. Dataset for: “Conical-helix magnetic textures stabilized in thin films with different kinds of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction” Github: https://github.com/Micromagnetics-Chile/paper_2025_conical_helix_dmi. (2025).

Cortés-Ortuño, D. et al. Micromagnetics Chile: oommf_dmi_extensions Github: https://github.com/Micromagnetics-Chile/oommf_dmi_extensions (2025).

Acknowledgements

Fruitful discussions with Dr. Rodolfo Gallardo are highly acknowledged. S.J.R.H. acknowledges support under the Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No 101152613. F.B. acknowledges support from the ANID National Doctoral scholarship 2021-21211469. D. C.-O. acknowledges the support from DGIIE (UTFSM) through the Postdoctoral initiative, and ANID Fondecyt de Iniciación en Investigación grant 11240429. We acknowledge financial support from Fondecyt grants 1241589 and Basal Program for Centers of Excellence CIA250002 (CEDENNA).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. C.-A. and P. L. developed the micromagnetic theory of conical-helix states. M. C.-A. conducted the theoretical analysis and prepared the related figures. F.B. performed the micromagnetic simulations and data analysis. D. C.-O. implemented the higher-order finite-difference schemes and boundary conditions in OOMMF. S. J. R. H. and H. F. implemented the Ubermag extensions and investigated the effect of finite-difference anisotropies in helical states. D. C.-O. and P. L. devised the main topic of this investigation. All the authors contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cepeda-Arancibia, M., Brevis, F., Holt, S.J.R. et al. Micromagnetics of conical-helix textures in thin films with different kinds of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions. npj Comput Mater 12, 55 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01926-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01926-6