Abstract

Electron diffraction(ED) often used to solve for unknown structures or refine existing ones. Existing methods for automated ED analysis often struggle with challenges such as computational expense and experimental noise. This study introduces a deep learning framework to accelerate and improve crystal structure determination from diffraction patterns. The methodology treats each diffraction pattern as a relational graph of Bragg spots. Spot features are encoded using a 1D convolutional network, from which a relational attention aggregator constructs an orientation-agnostic graph. This graph is processed by a Graphormer encoder enhanced with Mixture-of-Experts layers, allowing the model to learn complex crystallographic relationships efficiently. Trained and tested on a large dataset of simulated diffraction patterns, the model achieved a crystal system classification accuracy of 89.2% and a space group accuracy of 70.2% from single patterns, significantly outperforming a state-of-the-art random forest baseline (74.2% and 57.8%, respectively). By aggregating predictions across multiple zone axes, these accuracies improved to 96.5% and 79.5%. The model also demonstrated robust performance on experimental data of gold nanoparticles, producing plausible classifications consistent with known orientation degeneracies. By unifying relational graph reasoning with specialized expert networks, this work presents a robust and automated framework for high-throughput materials characterization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Material properties such as magnetism, conductivity, and mechanical strength are intrinsically governed by crystal structure1,2. While traditional techniques like X-ray diffraction3 and electron backscatter diffraction4 have long been used to probe crystal structure, they often face limitations in spatial resolution and the ability to characterize local heterogeneity.

Four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D-STEM)5 is a powerful technique where a focused electron probe is scanned across a sample, and a complete diffraction pattern is recorded at each probe position. While this method yields rich, spatially-resolved information about the local crystal structure, it also generates terabyte-scale datasets that pose a significant analysis bottleneck. The complexity of these datasets is compounded by experimental factors, such as noise and multiple electron scattering, which render manual interpretation impractical and demand automated analysis pipelines6,7,8,9,10.

In classical template matching, crystal orientation is assigned by maximizing the cross-correlation between the experimental spot pattern and precomputed theoretical templates, leveraging sparse reflection sets and simple intensity estimates for fast, robust indexing11. Automated crystal orientation mapping12 in 4D-STEM is commonly carried out through template matching of diffraction pattern libraries, where experimental patterns are compared to simulated ones to assign orientations. This approach has been widely applied in ED studies to improve the interpretability of diffraction patterns. More recently, a sparse correlation framework13 has been introduced to speed up orientation mapping by restricting template comparisons to populated radial bands of the reciprocal lattice and by directly sampling the first two Euler angles before resolving the in-plane rotation via FFT correlation. This method reduces the search space, allows efficient analysis of polycrystalline nanostructures. These template-based methods struggle as chemical compositions become novel, specimens grow thicker (introducing dynamical scattering), or detector noise increases. Furthermore, exhaustive searches over all possible orientations can become prohibitively slow, especially in high-throughput experiments14,15,16,17.

Machine learning alternatives18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 address some of these bottlenecks. Unsupervised clustering and dimensionality reduction27 group millions of patterns into orientation or phase domains but leave clusters unlabeled. Variational autoencoders (VAEs)28 learn smooth latent spaces correlated with thickness or strain, yet do not output symmetry directly. Supervised convolutional neural networks (CNNs)29 can map sub-pixel strain and predict crystal symmetry under known orientations, but fail under arbitrary tilts, and majority voting reduces throughput. Multiview opinion fusion frameworks19 extract symmetry information through a multi-step process by simulating multiple views and aggregating their predictions. While powerful, their complexity makes them difficult to adapt to novel or unconventional crystal systems.

A recent benchmark model, the Hierarchical Random Forest20, demonstrated that classic ensemble methods can offer transparent uncertainty estimates. Trained on a dataset of 3.6 million diffraction patterns generated from Bloch-wave simulations6 spanning 100 unique orientations, the model encodes each pattern as a fixed complex radial basis function and predicts crystal system, space group, and lattice constants in a cascading fashion. Aggregating votes across 10 patterns raised crystal system accuracy to around 75%, but performance degraded for low-symmetry systems and for lattices whose large parameters pushed spot spacings beyond the radial bin resolution, a limitation of the static, hand-engineered feature space.

In this work, we leverage graph neural networks (GNN)30,31,32,33,34,35,36 and attention mechanisms37 to determine crystal structure from diffraction patterns. Self-attention37 and graph transformers34 offer several advantages over more commonly used convolutional encoders and VAEs38,39 in the context of diffraction analysis. CNNs are powerful local feature extractors that treat diffraction patterns as dense images on a regular grid. Their inductive bias is toward local, translationally equivariant features, so long-range correlations between diffraction spots remain hard to infer. VAEs, in turn, are optimized to reconstruct images and produce smooth latent spaces, but they are not explicitly designed to encode pairwise relations between diffraction. In contrast, GNNs and graph transformers represent each diffraction spot as a node and explicitly model the symmetry and relative intensities of diffraction spots via attention over edges, enabling the network to reason about variable sized, sparse sets of diffraction patterns in a permutation-invariant manner. Self-attention layers can directly capture long-range dependencies between distant diffraction spots, while relational encodings injected into the attention mechanism allow the model to incorporate crystallographic priors that are difficult to express in standard CNN or VAE architectures.

We design an attention based GNN to infer crystal structure directly from diffraction patterns. Each diffraction spot is represented as a node whose coordinates and intensity are embedded by a 1D convolutional network. A Relational Attention Aggregator40 then infers pairwise weights and constructs a weighted graph, seeding crystallographic priors directly into the attention matrix. The core of the model is a Graphormer encoder34, selected for its ability to propagate long-range dependencies, and each feed-forward block is replaced by a parameter-efficient shared Mixture-of-Experts41 (see https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-4-multimodal-intelligence/, accessed 11 June 2025). This design allows different experts to specialize in distinct symmetry regimes while maintaining a shared representation. The end-to-end differentiability enables the model to learn subtle intensity correlations while remaining agnostic to the crystal’s orientation. We trained our model on the same 3.6 million diffraction pattern dataset used for the random forest (RF) baseline, ensuring a head-to-head comparison. We further validated the trained network on a held-out test set as well as on experimental 4D-STEM scans of gold nanoparticles, recorded on a conventional 200 kV instrument. Our GNN model with an attention mechanism, Pointlist Encoder—Attention Graph - Graphormer Mixture of Experts (PE-AG-GMoE) significantly improved crystal system prediction accuracy, reducing classification error by over 10% compared to the random forest model.

Results

PE-AG-GMoE performance overview

Our proposed PE-AG-GMoE model achieves a test accuracy of 89.2% on single zone axis diffraction patterns from the dataset described in Section “Dataset” (2,765,943 training and 921,888 test patterns at 20 nm thickness). On the same dataset, the RF baseline20 reaches 74.2% accuracy. Multiview opinion fusion machine learning (MVOF-ML)19, developed for a simulated dataset of 119,000 training and 329,000 test patterns, reports an overall accuracy of 0.55 using single zone axis diffraction patterns. Together, these results highlight the substantial performance gain of PE-AG-GMoE over both RF and MVOF-ML (Table 1), despite the increased dataset size and structural diversity.

Crystal system accuracy

Our model outperforms the RF baseline20 by a wide margin, achieving an overall crystal system classification accuracy of 89.2% on 921,888 diffraction patterns from 9170 unique materials (baseline RF: 74.2%). Class-level accuracies range from 97.8% for cubic and 93.0% for hexagonal down to 64.5% for triclinic, with mid-symmetry systems also performing strongly (orthorhombic: 92.3%, tetragonal: 93.3%, monoclinic: 84.9%, and trigonal: 84.6%).

We also report per crystal system precision, recall (accuracy), and F1-scores together with the number of test patterns, unique materials, and distinct space groups. As summarized in Table 2, precision and F1 remain high for the higher-symmetry systems (cubic, tetragonal, and orthorhombic) despite differences in the number of materials and space groups represented in the test set.

Crystal system accuracy of aggregate predictions

Evaluating predictions after pooling ten randomly selected zone axis patterns per material sharpens the performance of both models. However, the performance gap between the learned graph model and the descriptor-based baseline widens further (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

a A confusion matrix from individual diffraction pattern predictions reveals the distribution of class assignments across symmetry groups, b aggregated predictions across multiple zone axes show a more consolidated assignment pattern with reduced inter-class confusion, c confidence scores for individual predictions reflect varying levels of certainty across different symmetry types, and d aggregated confidence scores demonstrate enhanced prediction consistency after multi-view integration.

The majority-vote scheme raises the overall accuracy of our PE-AG-GMoE model to 96.5% on 9170 materials, a gain of 7% over its single-pattern score (Table 3). The RF model also benefits, improving to 85.5%.

Space group accuracy

The distribution of space groups is highly imbalanced and long-tailed, as discussed in Section “Dataset” and shown in Fig. 4, which makes space group prediction a significantly harder task than crystal system classification.

Despite this challenge, the PE-AG-GMoE model achieves a space group classification accuracy of 70.2% on single zone axis patterns, outperforming the descriptor-based RF model by 12% (Table 4). As with crystal systems, cubic lattices are the most distinguishable (86.0%), followed by hexagonal (77.5%) and tetragonal (70.2%).

Experimental data analysis

To assess our model’s performance on real data, we applied it to a 4D-STEM scan of gold nanoparticles (Au NPs). Probe positions with fewer than five diffraction spots were removed, and a 5 × 5 median filter was applied to smooth the predictions. Finally, pixels with a confidence score below 0.005 were excluded to ensure reliable results20.

As shown in Fig. 2c, 48% of probe positions are classified as cubic, 44% as hexagonal, and 8% as tetragonal. This distribution aligns with the known orientation degeneracy in FCC Au: specifically, the [111] zone axis produces diffraction patterns that are often indistinguishable from those of hexagonal structures42.

Discussion

The PE-AG-GMoE architecture is specifically designed to process multiple scattering in electron diffraction and to recover crystal systems reliably. Accuracy (Table 3) declines steadily as symmetry decreases, consistent with the increasing structural diversity represented by each label. For cubic crystals, the model achieves near-ideal precision-recall balance (F1 ≈ 97%; Table 2), indicating that in the highest-symmetry case the learned graph representation closely tracks the symmetry even in the presence of dynamical scattering. Tetragonal and orthorhombic systems show only a modest degradation in F1 (still in the low 90% range), with precision and recall remaining well matched, suggesting that the network continues to exploit the characteristic multiplicities of Bragg reflections as symmetry is lowered. Taken together, these high and mid symmetry classes show that the joint behavior of precision, recall, and F1 is consistent with the underlying diffraction complexity. Labels are rarely assigned in directions incompatible with the expected symmetry, and most genuine instances are recovered despite intensity variations arising from multiple scattering effects.

In contrast, the steepest degradation appears for triclinic patterns, where recall drops to 64.5% and F1 to 72.6% despite a relatively high precision of 83.0%; this combination suggests that, while predicted triclinic labels are usually correct when they occur, a substantial fraction of true triclinic instances are still being absorbed into neighboring symmetry classes. Because triclinic lattices have no right angles and unequal axes, their 2D Bragg spot geometry lacks simple inter-spot angles, making single-projection indexing more sensitive to noise and dynamical effects. Given that the dataset contains nearly as many triclinic as trigonal samples (Fig. 3), class imbalance is an unlikely explanation. Instead, many triclinic crystals are only slightly distorted from monoclinic lattices, with diffraction spots that differ by subtle reciprocal lattice tilts that are difficult to resolve in a single 2D projection. Consequently, the model most often misclassifies triclinic samples as monoclinic, reflecting their physical proximity in reciprocal space. These trends are clearly visible in the single-pattern confusion matrix and confidence distributions (Fig. 1a and c), where triclinic predictions show both enhanced leakage and lower confidence relative to the high-symmetry classes. These types of confusion are consistent with known challenges in crystal system classification. For instance, the previous work using random forest classifiers also excluded triclinic labels due to their frequent confusion with monoclinic patterns. In our case, we retain all crystals but acknowledge that model accuracy for low-symmetry systems may be improved further. A smaller but related confusion exists between trigonal and hexagonal systems (Fig. 1a and c), whose six-fold zone axis patterns differ mainly by inversion symmetry. One promising direction is to incorporate multiple views of reciprocal space during training or inference, enabling the model to distinguish subtle symmetry-breaking features that are otherwise ambiguous in a single projection. In particular, adding MicroED43 tilt-series provides the true 3D reciprocal-space coverage (each frame captures a wedge), which reduces projection and pseudo-symmetry ambiguities under noise and dynamical scattering. This challenge is partially addressed in our approach by aggregating predictions across multiple zone axes.

To quantify the benefits of the PE-AG-GMoE model, we compare our model performance metrics against the RF model trained on handcrafted static descriptors. The RF achieves an overall accuracy of 74.2%, and performance on systems of lower symmetry, only 62% for monoclinic and 57% for orthorhombic (Table 3). It approaches parity only on trigonal systems (86% vs. 84.6%), suggesting that static descriptors may capture some rotational motifs but fail to represent the symmetry and diversity learned by our model. Overall, these results demonstrate that a model architecture designed around specific aspects of electron scattering provides a significant improvement for classifying crystal systems. This is especially true for low-symmetry systems, where elements such as expert ensembles may identify the subtle distinctions necessary for accurate classification.

Evaluating predictions after pooling ten randomly selected zone axis patterns per material sharpens the performance of both models, but the performance gap between the learned graph model and the descriptor-based baseline widens further (Table 3, Fig. 1b and d). At the class level, every crystal system except triclinic now exceeds 90% accuracy. Orthorhombic accuracy jumps from 92.3 to 99.0%, and monoclinic from 84.9 to 96.2%. These gains affirm that the relational attention aggregator and mixture-of-experts blocks capture robust, symmetry-specific features that become more evident when stochastic orientation effects are removed.

The aggregated confusion matrix and confidence distributions (Fig. 1b and d) show that nearly all off-diagonal mass collapses onto the main diagonal and that prediction confidences become more sharply peaked compared with the single-pattern case (Fig. 1a and c). The triclinic-to-monoclinic leakage observed in single-pattern analysis is reduced to below 1%, and the misclassification between hexagonal and trigonal systems is virtually eliminated. In the row-normalized view (Fig. 1d), every class except triclinic achieves recall above 90%, while triclinic itself retains a strong 83.8%. These patterns are consistent with the high precision and F1 values reported for most crystal systems (Table 2), and the remaining errors are concentrated in the most structurally ambiguous regimes. In contrast, the RF model performs unevenly across classes. While it exceeds 90% only on trigonal and cubic systems, it hovers near 70% for monoclinic and orthorhombic patterns (Table 3). These results indicate that the simple angular and distance-based descriptors used by RF cannot distinguish the patterns that define mid-symmetry systems, even when multiple patterns are available. Overall, aggregating diffraction evidence at the material level magnifies the strengths of the graph-based architecture, its ability to form robust relational embeddings, and benefits from expert specialization while exposing the limitations of static features. The remaining classification errors are confined almost entirely to the lowest-symmetry class and trigonal materials, reinforcing the conclusion that further gains will likely require richer 3D structural information rather than additional in-plane modeling capacity.

The distribution of space groups is highly imbalanced and long-tailed (Fig. 4), which makes space group prediction a significantly harder task than crystal system classification. The model performance shows a clear dependence on the number of space group labels within each crystal system. For example, triclinic crystals have only two space groups. Once the model learns their distinct spot splitting patterns, it achieves 70.2% accuracy, increasing to 79.5% when predictions are aggregated across ten randomly selected zone axis patterns per material. In contrast, orthorhombic crystals span nearly 60 space groups. This higher label entropy makes them more difficult to classify, the model starts at 63.5% and improves to 71.8% with aggregation. The same trend holds for other systems (i.e., hexagonal, tetragonal, and monoclinic), where aggregation consistently boosts performance.

Aggregating predictions across ten orientations raises the overall space group accuracy of the PE-AG-GMoE model to 79.5%. The RF model also improves with aggregation but reaches only 68.5%. These gains suggest that viewing each material from multiple directions helps expose additional extinction features. Both the Relational Attention Aggregator and the expert sub-networks benefit from this extra information, with monoclinic accuracy rising to 76.6% and cubic reaching 91.6%. In contrast to the RF baseline, which requires a separate model for each crystal system, our approach performs the joint prediction of both crystal systems and space groups within a single model. The shared Mixture-of-Experts block allows the network to capture common structural patterns across symmetry types without increasing model size. Most remaining errors occur in monoclinic and orthorhombic systems, where the number of possible space groups is highest. It suggests that further improvement may depend on models that explicitly incorporate hierarchical structure, where space group predictions are conditioned on crystal system predictions. Such models could better reflect the nested nature of crystallographic symmetry and improve interpretability.

On experimental Au nanoparticle data (Fig. 2), the model’s predictions reflect both its strengths and remaining limitations. The observed 48% cubic, 44% hexagonal, and 8% tetragonal fractions align with the known orientation degeneracy in FCC Au, where the [111] zone axis can mimic hexagonal diffraction patterns42. Many misclassifications can be attributed to multiply-twinned particles, whose overlapping diffraction signals were not represented in the training data. When compared with a baseline random forest model, which yielded a roughly 40%–40%–20% split between cubic, hexagonal, and tetragonal classifications, our graph-based model significantly reduces the tetragonal predictions. This suggests that the model is learning to exploit symmetry features present in the training data, even under limited zone axis views. While twinning artifacts remain a challenge, these improvements indicate better discrimination between true symmetry classes and spurious symmetry artifacts. The model relies on Bragg peak coordinates as input. Therefore, errors or inaccuracies in peak detection can propagate and adversely affect the downstream prediction of crystal systems and space groups. Incorporating simulated patterns of twinned and polycrystalline structures in future training data should further enhance robustness under experimental conditions. Another potential solution to these ambiguities is to construct physics-informed crystal-symmetry-aware neural networks and train them on datasets with multiple sample thicknesses. This strategy may enable the model to learn 3D structural context that is otherwise inaccessible in the current training dataset.

From a hardware perspective, our current implementation processes 10,000 diffraction patterns in approximately 120 s on a single 16 GB NVIDIA RTX A4000 GPU with a batch size of 4, and larger batch sizes or multi-GPU parallelism can further improve throughput. In contrast, the RF baseline is evaluated on CPUs and is effectively constrained to a single host, making it harder to exploit modern accelerator hardware. As a result, the PE-AG-GMoE model is not only more accurate but also better aligned with real-time or near-real-time 4D-STEM5 data streams in practical electron diffraction experiments.

As a conclusion, in this study we introduced a hierarchical attention-graph transformer, PE-AG-GMoE, that models diffraction patterns as relational graphs and leverages conditional experts to specialize in distinct symmetry regimes. Compared with a state-of-the-art random-forest pipeline trained on identical Bloch-wave simulations, the proposed network achieves substantially higher accuracy for both crystal systems (89.2% vs. 74.2%) and space groups (70.2% vs. 57.8%) on single zone axis. It further improves to 96.5% (crystal systems) and 79.5% (space groups) when predictions from ten zone axis views per material are aggregated. It is also compatible with high-throughput 4D-STEM workflows.

Methods

Dataset

We use a simulated electron diffraction dataset originally introduced in Gleason et al.20, which was constructed from experimentally observed structures in the Materials Project44. After filtering for physically realistic unit cell volumes and simulating 100 unique zone-axis patterns per structure, the dataset contains over 3.6 million diffraction patterns across approximately 36,000 materials.

For this work, we use the 20-nm thickness simulations and split the dataset into 75% for training and 25% for testing. The dataset was randomly split at the material level, ensuring no material appears in both training and test sets. In total, the training split contains 2,765,943 diffraction patterns from 27,511 unique materials, while the held-out test split contains 921,888 diffraction patterns from 9170 unique materials. All seven crystal systems are represented, though the distribution is naturally imbalanced due to their frequency in real materials, as summarized in Table 5. The percentage of patterns from each system is shown in Fig. 3, with orthorhombic and monoclinic systems being the most common, followed by tetragonal and hexagonal. Trigonal and triclinic crystals account for smaller portions of the dataset.

Out of the 230 crystallographic space groups, 197 are represented in the full diffraction dataset. The held-out test set contains 182 of these space groups; the remaining, extremely rare groups occur only in the training split. The long-tailed nature of this distribution is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Model Architecture

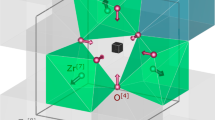

Our PE-AG-GMoE model maps a raw diffraction pattern to crystal system and space group predictions by encoding Bragg spots into pointwise embeddings, assembling them into an attention-weighted graph, and processing this graph with a graphormer mixture-of-experts backbone; a schematic of this end-to-end workflow is shown in Fig. 5.

A raw diffraction pattern is converted into a set of Bragg spots, which are embedded by the Bragg spot encoder. A multi-head attention graph aggregator then constructs an attention-weighted graph over the spots and produces structural descriptors. The graphormer mixture-of-experts module operates on this attention graph and outputs probabilities over crystal systems.

Each diffraction pattern is represented as a collection of Bragg spots, with each spot described by its cartesian coordinates (qx, qy) and intensity I. Each spot is transformed to polar coordinates, with radial distance \(r=\sqrt{{q}_{x}^{2}+{q}_{y}^{2}}\) and angle \(\theta =\arctan 2({q}_{y},{q}_{x})\). These features are concatenated to form the input vector:

For each spot i, the features are then normalized across each channel to promote stable learning dynamics.

These normalized vectors are passed through a series of pointwise linear transformations and nonlinear activations (Fig. 6), resulting in a learned feature embedding for each spot.

Specifically, the encoded representation is given by:

where d denotes the final feature dimension. The resulting set of learned embeddings provides a rich representation of the diffraction pattern.

To enhance the representational capacity and enable conditional computation, we incorporate a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) design inspired by LLaMA 4’s shared expert routing architecture (see https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-4-multimodal-intelligence/, accessed 11 June 2025). block as a replacement for the conventional feed-forward network. Each input embedding xi is routed through a set of K local experts, with a gating mechanism dynamically selecting the most appropriate experts for each token.

The gating logits are computed as:

where Wgate is the learnable gating matrix and gi contains the unnormalized routing scores for the K experts.

The routing probabilities are then obtained via softmax normalization:

For each input, the top-k experts are selected based on the highest routing probabilities. Each expert is parameterized by a set of weight matrices and implements a SwiGLU transformation. For expert k, the output for a given token is:

where \({W}_{1}^{(k)},{W}_{2}^{(k)},{W}_{3}^{(k)}\) are the expert-specific parameters, SiLU( ⋅ ) denotes the sigmoid-weighted linear unit activation, and ⊙ is elementwise multiplication.

The expert outputs are weighted by their respective gating probabilities and aggregated:

where \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{i}\) is the set of top-k experts assigned to token i.

Additionally, all tokens are processed through a shared expert to promote regularization and ensure coverage. The final output of the MoE block is given by:

where \({y}_{i}^{({\text{shared}})}\) is the output from the shared expert.

This architecture enables adaptive, expert-driven transformations for each input, significantly improving the model’s expressiveness and computational efficiency.

Following the extraction of high-dimensional spot-wise feature vectors from the pointlist encoder (Eq. (1)), we construct a relational graph representation using a stack of attention-based transformations (Fig. 7). Each feature vector is first projected through a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to enhance its expressive capacity, then normalized and processed via a multi-head self-attention (MHA) mechanism.

The self-attention operation computes contextualized embeddings for each spot by aggregating information across all other spots. The updated features hi after the first attention block are given by:

where MHA( ⋅ ) denotes the multi-head attention block and Norm1 is the first layer normalization.

These contextual embeddings are then passed through the MoE block described in Eq. (6), leading to:

where Norm2 is the second layer normalization.

After the second attention layer, we aggregate the pairwise attention matrices40 from both layers to construct a weighted adjacency matrix, encoding the emergent relational structure among all Bragg spots:

where Attn(1) and Attn(2) are the attention weight matrices from the first and second multi-head attention blocks, respectively.

This aggregated adjacency matrix serves as a learned graph structure that reflects both local and global interactions, facilitating relational reasoning among Bragg spots.

To enrich the graph representation with structural information, we compute two key descriptors directly from the learned adjacency matrix A (Eq. (9)): the shortest path distances and node degrees.

For a batch of graphs, the shortest path distance dij between each pair of nodes i and j is computed by iteratively identifying new paths that represent increasing path lengths. From this, we construct the shortest path matrix D ∈ ZN×N, where each element dij encodes the minimal number of edges needed to traverse from node i to node j.

Additionally, we define a path data tensor P ∈ RN×N×L, where:

The degree of each node is computed as the sum of its connections (i.e., the row-wise sum of the binary adjacency matrix). Formally, for node i, the degree is defined as:

where \({1}_{{A}_{ij}\, > \,0}\) is an indicator function denoting whether an edge exists between nodes i and j. These structural descriptors serve as the basis for the subsequent embedding layers that encode graph topology into learnable representations.

We make the structural descriptors learnable by encoding them using three types of embedding layers: path encoding, degree encoding, and spatial encoding.

For every pair of nodes, we encode information about the shortest path connecting them by aggregating edge features along these paths. Given the shortest path distance matrix D and the corresponding path feature tensor P, a learnable embedding table is applied to capture path-specific biases for the attention mechanism. The resulting path encoding for a node pair (i, j) is computed by projecting the edge features along the shortest path through the embedding table and normalizing by the path length:

where Embedl denotes a learnable embedding for each step along the path.

Each node’s degree, representing its number of direct neighbors, is encoded via a learnable embedding. For a node i with degree ki, the degree embedding is given by:

where Embeddeg is an embedding table indexed by node degree. This encoding allows the model to capture local connectivity patterns and differentiate nodes based on their structural roles.

To provide an explicit notion of geometric separation, we introduce a spatial encoding that assigns a learnable embedding to each possible shortest path distance between node pairs. For nodes i and j separated by a path of length dij, the spatial encoding is:

where Embedspatial is a learnable embedding table indexed by path length. This spatial bias is added to the attention computation, enabling the model to modulate interactions based on topological separation within the graph.

Together, these structural encodings equip the graph transformer with rich, learnable representations of path structure, local connectivity, and spatial context, thereby enhancing its ability to model the complex relational patterns present in diffraction-derived graphs.

The Graphormer34 architecture (Fig. 8) processes each input graph by first projecting node features into a latent space of dimension d and enriching these representations with learnable degree embeddings (Eq. (11)), yielding the updated node encodings:

where hi is the original node feature vector and Embeddeg is the learnable degree embedding.

The Graphormer mixture-of-experts model operates on the attention graph using biased self-attention informed by structural descriptors. Node and graph-level representations are refined through expert routing and residual connections, yielding a final representation used for crystal system classification.

A virtual graph-level token is then prepended to each graph’s node embedding sequence, serving as a global summary representation. Pairwise structural relations between nodes, including shortest path and spatial information from Eq. (10) and Eq. (12), are encoded into the attention mechanism via a multi-head bias tensor:

where \({Q}_{i}^{(h)}\) and \({K}_{j}^{(h)}\) are the query and key vectors for head h, and \({b}_{ij}^{(h)}\) is the structural bias derived from path and spatial encodings.

The resulting attention outputs are aggregated and passed through residual connections, dropout, and a layer-normalized MoE block (Eq. (6)):

Each node’s representation is conditionally routed through multiple expert subnetworks. After passing through all stacked Graphormer layers, the graph-level token is extracted as the final graph representation. This token is further refined using a separate MoE block specialized for graph-level tasks.

The processed graph token is then passed to task-specific linear heads. The crystal system head maps from dimension d to 7 classes, while the space group head maps to 230 classes. This hierarchical flow ensures that both node-level and global relational information, along with adaptive expert-driven transformations, are systematically integrated to achieve robust graph classification.

Training Details

The model was trained using a supervised classification objective with a dataset split of 75% for training and 25% for testing. Hyperparameter tuning was performed manually, with a focus on stabilizing convergence and avoiding overfitting. Training was conducted on eight NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40 GB of memory in a distributed data-parallel configuration, with gradient accumulation used to manage memory usage effectively. A single model was trained jointly for both crystal system and space group prediction, leveraging shared architectural components to maintain parameter efficiency. In total, the training consumed approximately 480 GPU-hours (60 h per GPU), but the use of a MoE architecture with only k = 2 experts active per forward pass reduced the effective compute time to nearly \(\frac{k}{N}\approx \frac{2}{6}\) of the full cost, leading to a substantial gain in training efficiency.

The training objective comprises Eq. (16), standard cross-entropy losses for both crystal system classification and space-group classification. We apply equal weighting to both loss components with an auxiliary load balancing loss inspired by the Switch Transformer architecture45. The load balancing term encourages uniform expert utilization across tokens and is weighted by a tunable hyperparameter α = 0.01. This loss penalizes routing imbalance by computing the product of the fraction of tokens assigned to each expert and the average routing probability, scaled by the number of experts.

Table 6 summarizes the key hyperparameters used during training.

Data availability

The diffraction dataset, trained model checkpoints, experimental data, and test-time prediction files are available in the google drive at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1q0ZtQn8rW76dRiEmV7NKzzbP9VgoBubN?usp=sharing.

Code availability

The code base for this study, including training and evaluation scripts for the PE-AG-GMoE framework, is available at https://github.com/amdlou/PE-AG-GMoE.git.

References

Müller, U. Symmetry Relationships between Crystal Structures: Applications of Crystallographic Group Theory in Crystal Chemistry (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Kittel, C. & McEuen, P. Introduction to Solid State Physics (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Epp, J. X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques for materials characterization. in Materials Characterization Using Nondestructive Evaluation (NDE) Methods (eds Hübschen, G., Altpeter, I., Tschuncky, R. & Herrmann, H.-G.) 81–124 (Woodhead Publishing, 2016).

Schwartz, A. J., Kumar, M., Adams, B. L. & Field, D. P. (eds.) Electron Backscatter Diffraction in Materials Science (Springer, 2009).

Ophus, C. Four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D-STEM): from scanning nanodiffraction to ptychography and beyond. Microsc. Microanal. 25, 563–582 (2019).

Savitzky, B. H. et al. py4DSTEM: a software package for four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy data analysis. Microsc. Microanal. 27, 712–743 (2021).

Gruene, T., Holstein, J. J., Clever, G. H. & Keppler, B. Establishing electron diffraction in chemical crystallography. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 660–668 (2021).

Zeltmann, S. E. et al. Uncovering polar vortex structures by inversion of multiple scattering with a stacked Bloch wave model. Ultramicroscopy 250, 113732 (2023).

Stach, E. et al. Autonomous experimentation systems for materials development: a community perspective. Matter 4, 2702–2726 (2021).

Diebold, A. C. et al. Template matching approach for automated determination of crystal phase and orientation of grains in 4D-STEM precession electron diffraction data for hafnium zirconium oxide ferroelectric thin films. Microsc. Microanal. 31, ozaf019 (2025).

Rauch, E. Rapid diffraction patterns identification through template matching. Arch. Metall. Mater. 50, 87–89 (2005).

Jeong, J., Cautaerts, N., Dehm, G. & Liebscher, C. H. Automated crystal orientation mapping by precession electron diffraction-assisted four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy using a scintillator-based CMOS detector. Microsc. Microanal 27, 1102–1112 (2021).

Ophus, C. et al. Automated crystal orientation mapping in py4dstem using sparse correlation matching. Microsc. Microanal 28, 390–403 (2022).

Price, C., Takeuchi, I., Rondinelli, J., Chen, W. & Hinkle, C. AI-accelerated electronic materials discovery and development. Comput. 58, 98–104 (2025).

Chen, K. & Barnard, A. Advancing electron microscopy using deep learning. J. Phys. Mater. 7, 022001 (2024).

Kalinin, S. V. et al. Machine learning for automated experimentation in scanning transmission electron microscopy. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 227 (2023).

Levine, D. S. et al. The open molecules 2025 (omol25) dataset, evaluations, and models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.08762 (2025).

Yoo, T. J. Leveraging multimodal data analytics with advanced electron microscopy to obtain quantitative structural insights into complex materials. Ph.D. thesis, University of Florida (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Automated crystal system identification from electron diffraction patterns using multiview opinion fusion machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2309240120 (2023).

Gleason, S. P. et al. Random forest prediction of crystal structure from electron diffraction patterns incorporating multiple scattering. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 093802 (2024).

Mika, M., Tomczak, N., Finney, C., Carter, J. & Aitkaliyeva, A. Automating selective area electron diffraction phase identification using machine learning. J. Materiomics 10, 896–905 (2024).

Tomczak, N. & Kuppannagari, S. Automated indexing of tem diffraction patterns using machine learning. In 2023 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC), 1–7 (IEEE, 2023).

Tiong, L. C. O., Kim, J., Han, S. S. & Kim, D. Identification of crystal symmetry from noisy diffraction patterns by a shape analysis and deep learning. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 196 (2020).

Aguiar, J. A., Gong, M. L. & Tasdizen, T. Crystallographic prediction from diffraction and chemistry data for higher throughput classification using machine learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 173, 109409 (2020).

Aguiar, J., Gong, M. L., Unocic, R., Tasdizen, T. & Miller, B. Decoding crystallography from high-resolution electron imaging and diffraction datasets with deep learning. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw1949 (2019).

Mortazavi, B. Recent advances in machine learning-assisted multiscale design of energy materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2403876 (2025).

Martineau, B. H., Johnstone, D. N., van Helvoort, A. T., Midgley, P. A. & Eggeman, A. S. Unsupervised machine learning applied to scanning precession electron diffraction data. Adv. Struct. Chem. Imaging 5, 1–14 (2019).

Bridger, A., David, W. I., Wood, T. J., Danaie, M. & Butler, K. T. Versatile domain mapping of scanning electron nanobeam diffraction datasets utilising variational autoencoders. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 14 (2023).

Ra, M. et al. Classification of crystal structures using electron diffraction patterns with a deep convolutional neural network. RSC Adv. 11, 38307–38315 (2021).

Corso, G., Stark, H., Jegelka, S., Jaakkola, T. & Barzilay, R. Graph neural networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 4, 17 (2024).

Bruna, J., Zaremba, W., Szlam, A. & LeCun, Y. Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs. In Proc. 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations (2014).

Kipf, T. N. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proc. 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. In Proc. 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (2018).

Ying, C. et al. Do transformers really perform bad for graph representation? In Proc. 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Curran Associates Inc., 2021).

Yang, H. et al. Mattersim: a deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.04967 (2024).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 93 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. In Proc. 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations (2014).

El, B., Choudhury, D., Liò, P. & Joshi, C. K. Towards mechanistic interpretability of graph transformers via attention graphs. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12352 (2025).

Lepikhin, D. et al. Gshard: scaling giant models with conditional computation and automatic sharding. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Curran Associates Inc., 2020).

Ponce, A., Aguilar, J. A., Tate, J. & Yacamán, M. J. Advances in the electron diffraction characterization of atomic clusters and nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 3, 311–325 (2021).

Mu, X., Gillman, C., Nguyen, C. & Gonen, T. An overview of microcrystal electron diffraction (MicroED). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 90, 431–450 (2021).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 1002 (2013).

Fedus, W., Zoph, B. & Shazeer, N. Switch transformers: scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 23, 120 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NSF grant 2320468, supported by the Research Council of the University of Oklahoma and the Samuel Roberts Noble Microscopy Laboratory at the University of Oklahoma. A.R.C.M. and C.O. acknowledge support from Stanford University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.O. and I.G. conceptualized the study and supervised the project. C.O. provided the dataset for the analysis. A.N. developed the necessary code, performed the analysis, and wrote the original manuscript draft. A.M. provided regular support in code development and data analysis. Y.L., H.D., P.K., and S.X. contributed to valuable scientific discussions and provided feedback on the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nathani, A., McCray, A.R., Liu, Y. et al. Accelerating electron diffraction analysis using graph neural networks and attention mechanisms. npj Comput Mater 12, 56 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01927-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01927-5