Abstract

Diamane, a two-dimensional diamond-like carbon phase, illustrates how computational materials science can anticipate structures and transformations later verified experimentally. This Perspective summarizes theoretical predictions and experimental observations of its stability, chemically driven diamondization, and property modulation through functionalization and orientation. We highlight how atomistic simulations refine the understanding of formation pathways and guide potential applications in electronics, photonics, and energy systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of two-dimensional (2D) materials has redefined the frontiers of materials science, with graphene1,2 catalyzing the pursuit of other ultrathin layers endowed with special properties. Among these, diamane3—a 2D diamond—stands as a paradigm-shifting candidate, marrying the superlative mechanical, thermal, and electronic qualities of bulk diamond with the exotic quantum confinement and flexibility, intrinsic to nanoscale architectures4,5,6,7. Yet, the realization of diamane remains hindered by synthesis challenges, as traditional high-pressure routes falter under surface-driven graphitization. Herein lies the leading role of computational materials science: theoretical frameworks have not only illuminated the basic physics of diamane but also charted viable pathways toward its experimental actualization.

While experimental efforts remain predominantly focused on synthesis, theoretical studies have laid the ground for understanding diamane’s stability, phase transitions, and property modulation. This review highlights the key role of computational approaches—including density functional theory (DFT), molecular dynamics (MD), and modern machine-learning potentials such as moment tensor potentials (MTPs)8—in understanding the thermodynamics, kinetics, and structure–property relations of diamane. Crucially, such simulations have unraveled the delicate interplay between surface functionalization (e.g., hydrogenation, fluorination), crystallographic orientation, and layer thickness of diamane in dictating mechanical stability, thermal transport, and electronic band structure as presented in the Fig. 1.

The model here is a (111)-oriented diamane, while other surface orientations are discussed in the text. The upper surface is depicted with several functional groups commonly considered in theoretical and experimental studies: hydrogen (cyan spheres), hydroxyl groups (red and cyan spheres), fluorine (light yellow), and substitutional nitrogen or boron atoms (blue and green spheres). The carbon atoms are depicted by yellow spheres. The lower surface can be either passivated by similar groups or supported by typical metal substrates such as cobalt, nickel, copper, or platinum (cyan rectangle). The substitutional dopants, nitrogen (N) and boron (B), etc., further enhance diamane electronic tunability. The number of atomic layers (L) defines the film thickness, which, together with surface chemistry and doping, determines the structural stability and physical properties of 2D diamond films.

Central to this discourse is the chemically induced phase transition9,10, a computational prediction now substantiated by experiment, wherein functionalized few-layer graphene transforms into diamane under modest pressure or even ambient conditions. We summarize and analyze the thermodynamic phase diagrams governing these transitions, emphasizing how surface passivation surmounts the nucleation barriers intrinsic to ultrathin systems. Experimental results, from Raman spectroscopy to nanoindentation, are compared with theoretical predictions to demonstrate the connection between simulation and synthesis.

As the field strides toward wafer-scale diamane, this review sums up atomistic insights while touching on open questions of quantum confinement, optoelectronic tunability, and heterostructure design. Bridging computational foresight with empirical validation charts a roadmap for harnessing diamane’s full potential in next-generation nanoelectronics, quantum photonics, and ultrahard coatings—a testament to the transformative power of theoretical ingenuity in materials discovery.

For a coherent narrative, this review is organized as follows. Section “Structural landscape of diamane” discusses the structural definition and classification of diamanes, emphasizing the effect of surface functionalization, doping, crystallographic orientation, and film thickness on their properties. Section “Thermodynamics and mechanisms of formation” addresses thermodynamic aspects and phase transitions leading to diamane formation, including chemically induced routes and substrate effects. Section “Experimental validation” summarizes experimental evidence supporting theoretical predictions. Finally, Section “Prospects of applications” outlines the emerging applications of diamane.

Structural landscape of diamane

Before the thermodynamics of diamane formation, one should address its structural and functional diversity, underpinning all following aspects of stability and applications.

This section follows the historical developments of the field. Hydrogenated diamane was the first structure proposed and studied theoretically and experimentally, becoming an archetype for all subsequent functionalized variants—fluorinated, oxidized, and other modified diamanes explored further as derivatives. Pristine diamanes—films with unsaturated surfaces—have been considered only in a few works and are discussed at the end of this section.

Terminology and classification

While delving into a discussion of few atoms-thick diamond films, commonly referred to as diamanes, it is helpful to choose a consistent nomenclature, as the existing terminology remains somewhat erratic. Numerous names have been proposed for atomically thin diamond films, including diamane3, diamene11, diamondol12, diamondene13, (lonsdaleitene14), and 2D diamond15, while bilayer diamond films have been variously termed bilayer diamond16, bilayer graphane17, diamond-like bilayer graphene18, and diamondized bilayer graphene14. In this review, we adhere to the original term diamane, introduced by Chernozatonskii3 to denote a hydrogenated bilayer diamond film in his pioneering work. This terminology follows the precedent set by Sofo’s graphane19 (hydrogenated monolayer graphene), appropriately placing diamane within the family of alkane-saturated hydrocarbons, characterized by exclusively single C–C bonds. While this reasoning is somewhat imprecise for the films functionalized by elements other than hydrogen, we still call those diamanes, to not proliferate unnecessary terminology, adopting the Occam’s razor.

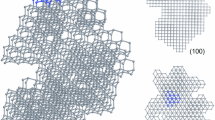

Beyond nomenclature, defining diamane necessitates a conceptual framework for atomic-thick films, an area of elusive consensus. Diamane occupies an intermediate place between a true monoatomic film, whose structure is best described through conformers, and a crystalline solid, whose surface is classified by Miller indices. Consequently, the films may adopt cubic diamond lattice in the limit of large thickness or hexagonal diamond (lonsdaleite). In the cubic phase, the most common surface orientations are (111), (110), and (100); while in the hexagonal phase they are \((10\bar{1}0)\), \((\bar{2}110)\), and (0001). In this classification, surfaces with orientations (111) and (110) correspond to the chair1 and chair2 conformers, while orientations \((10\bar{1}0)\), \((\bar{2}110)\), and (0001) correspond to the boat1, boat2, and chair1 conformers, respectively. Notably, the (100) surface does not align with any conformer, underscoring the limitations of a conformer-based classification. Given these ambiguities, we adopt a crystallographic convention, specifying diamanes by their surface orientation.

Another aspect of characterizing diamane is its surface functionalization, defined here explicitly by the terminating chemical elements (and if distinct elements cap opposing surfaces, both are specified). For oxidized films, whose structural irregularities preclude precise characterization, the broad designation is o-diamanes.

Finally, the films’ thickness. By convention, the term diamane denotes a bilayer structure unless explicitly stated otherwise. Accordingly, a bilayer hydrogenated diamane film with a (111) surface orientation will be an H-diamane(111).

Hydrogenated diamane

Hydrogenated diamane is a 2D diamond lattice passivated by hydrogen. It shows outstanding mechanical, thermal, and electronic properties compared to bulk diamond and other carbon nanomaterials. H-diamane inherits the extraordinary stiffness of diamond, with computations predicting longitudinal (νLA) and inplane-transverse (νTA) acoustic wave velocities approaching those of bulk diamond14,20,21. These velocities, calculated from the elastic constants and the areal density, highlight its strong in-plane rigidity. Some studies suggest that the in-plane stiffness of diamane exceeds that of graphene; however, we caution on the ambiguity of such conclusions. This discrepancy arises from the well-documented challenge of estimating the nanomaterial’s elastic moduli, inherently tied to the definition of cross-section or volume—entities lacking an unambiguous interpretation22. This issue dates back to the earliest studies on carbon nanotubes, culminating in the so-called “Yakobson’s paradox”23,24,25.

One way to resolve this is by employing effective elastic constants of lower dimensionality. In the case of 2D structures, 2D elastic constants’ calculations are based not on volume but on the well-defined area of the material, yielding units of N/m (the inherent trade-off being the linear rise of the elastic constant with the number of the film’s atomic layers).

Thus, to fairly compare the elastic constants of bilayer diamane and graphene, the former must be divided by two (2 L —2 layers), yielding a value of C11 = 232–251 N/m/L20,21,26,27,28,29,30, for H-diamane(111)—significantly lower than that of graphene (349 N/m20) and close to graphane’s 242 N/m20. However, we note that (111) diamane is not the stiffest among the bilayer hydrogenated diamond films. The highest elastic constant is predicted in H-diamane\((10\bar{1}0)\) (267–270 N/m/L21,29), reflecting the superior mechanical properties of hexagonal diamond (lonsdaleite).

Experimental nano-indentation studies11,31,32 confirm the very high stiffness of bilayer diamane, with measured indentation moduli of ~1000 GPa (~237 N/m/L)32, ~ 1079 ± 69 GPa (~256 ± 16 N/m/L), 11 ~ 1200 GPa (~285 N/m/L)31. These values exceed those of sapphire (412 ± 36 GPa) and even chemical vapor deposition (CVD) diamond (923 ± 78 GPa). Bending simulations demonstrate that bilayer diamane exhibits a bending stiffness of ~41 eV Å2 33,34, and displays high flexibility (Fig. 2a) while thicker configurations (3 L- and 4 L-diamane) display significantly enhanced bending stiffness (103.42 and 208.6 eV Å2, respectively)34. Notably, under bending, thicker diamane (≥3 layers) undergoes tension-induced brittle fracture, with cracks initiating at the tensile side and propagating layer-by-layer, governed by a critical von Mises stress threshold of ~112 GPa, slightly exceeding the ultimate tensile strain34.

a Mechanical flexibility calculated from the simulated indentation3 (top) and uniform bending33 (bottom). b Spatial division of electronic states. Band gaps for surface carbon atoms and for inner carbon atoms in H-diamane(111), marked by solid and empty circles. Inset shows 5L-H-diamane(111) with inner carbon circled39. c The semiconducting electronic structure with direct band gap of 2L-H-diamane(111), Fermi level is placed at zero3. d Temperature-dependent κ(T) of graphene, H-diamane(111), N-diamane(111) and bulk diamond43.

Electronically, H-diamane has a band gap that depends on both layer thickness and surface orientation. The gap can also be controlled by an external electric field applied perpendicular to the plane35. The diamane band gap decreases with greater thickness but doesn’t seem to tend to bulk diamond’s value20,21,36,37,38. This effect is caused by the contribution of surface states. Varlamova et al.39 revealed that the band gap of surface atoms gradually decreases with increasing layer number, tending toward 2.4 eV for thicker H-diamane(111) films, while the inner carbon layers do exhibit a band gap approaching the bulk diamond value of 4.2 eV (at GGA-PBE of DFT level), see Fig. 2b. This spatially divides electronic properties, in surface states (dominating in thinner films) and bulk-like behavior. Calculations show a direct band gap in ultrathin films (Fig. 2c), which becomes indirect as thickness increases due to Brillouin zone folding. 2 L-H-diamane displays the isotropic optical absorption peaks in the ultraviolet spectrum, positioning it as a robust candidate for optoelectronic applications27. Carrier effective masses in H-diamane remain comparatively low (see Table 1). This, combined with the high elastic modulus and moderate strain potential constant, contributes to the extraordinary hole mobility in the H-diamane(111), of about 1565 cm2/V s26, much higher than in bulk silicon (<450 cm2/V s40), suggesting H-diamane(111) as attractive alternatives to conventional semiconductors in electronics.

Thermally, H-diamane demonstrates remarkable conductivity, with theoretical estimates reaching 2 × 103 W/m K at room temperature: 1960 W/m K41,42, 2033 W/m K43 for H-diamane(111) (Fig. 2d), whereas H-diamane(0001) displays even larger values 2236 W/m K41 or 2240 W/m K42, due to the restricted phonon scattering phase space imposed by the horizontal reflection symmetry. Along zigzag and armchair directions, the thermal conductivity differs by a small amount below 4%44. Such high conductivity is linked to a hydrodynamic phonon transport regime with reduced Umklapp scattering and strong contribution from out-of-plane acoustic modes18,42. Comparative studies indicate that hydrogen’s low atomic mass preserves phonon group velocities, whereas heavier functional groups (e.g., fluorine) introduce scattering mechanisms that degrade thermal transport41,45.

For context, diamane’s thermal conductivity values place it among the best heat conductors known in the 2D family. Graphene, with reported room-temperature thermal conductivities in the range of 2000–5300 W/m K46, surpasses diamane, while 2D hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) typically exhibits 230–1100 W/m K depending on layer number47. In contrast, MoS2 and MoSi2N4 show much lower thermal conductivities (10–100 W/m K48 and 220 W/m K49, respectively), and graphyne has an even lower value less than 10 W/m K50,51. Overall, diamane combines high stiffness and thermal conductivity comparable to graphene and much higher than other semiconducting 2D materials such as MoS2 or graphyne. This makes it promising for thermal management and nanoelectronic devices.

Fluorinated diamane

Theoretical studies show that F-diamane has special electronic, mechanical, and thermal properties, determined by its sp3-hybridized carbon network and polarized C–F bonds. Notably, F-diamane shows higher oxidation resistance than H-diamane. The adsorption energy of atomic oxygen on fluorinated surfaces (−0.09 eV) is much lower than on hydrogenated ones (−6.02 eV), indicating strong chemical stability and potential use in high-temperature electronics52.

F-diamane retains remarkable in-plane stiffness, though its tensile strength and fracture strain exhibit anisotropy dependent on crystallographic direction. Simulations show that the elastic modulus of F-diamane (239–243 N/m/L26,45,53 for 2L-F-diamane(111) and 275 N/m/L53 for 2L-F-diamane\((10\bar{1}0)\)) is close to that of H-diamane. However, fluorination slightly reduces the fracture strain along the zigzag direction because of steric effects54.

The thermal conductivity of F-diamane is lower than that of H-diamane because the heavier fluorine atoms cause stronger phonon scattering. MD simulations report more than 80% reduction in thermal conductivity for F-diamane, at 360–400 W/m K41,42,45,55.

For the (111), (110), and \((10\bar{1}0)\) surfaces, the calculated direct band gap of F-diamane is about 30% larger than that of H-diamane (see Table 2). This increase is caused by the strong electronegativity of fluorine, which enhances quantum confinement. It is complemented by isotropic optical absorption peaks in the ultraviolet spectrum, positioning it as a robust candidate for optoelectronic applications27. In GGA-PBE calculations, the band gap of F-diamane(111) and F-diamane(110) does not monotonically approach the bulk diamond value with increasing thickness. The dependence shows a minimum before converging to the bulk limit. In contrast, the LDA56, PBEsol, HSE0654, and GW53 methods predict a steady convergence of the diamond film band gap toward the bulk value with increasing thickness (Fig. 3a). Although all methods acknowledge the nonlinear dependence in few-layer films, the thickness at which the extremum occurs varies—four layers for LDA56, PBE53, and PBEsol54, three for HSE0654, and two for GW53. This is because few-layer films manifest a direct band gap (Fig. 3a, inset), while an increase in layer number precipitates a lowering of the bands in the Γ−M direction, thereby transforming the direct band gap into an indirect one53. Furthermore, F-diamane\((10\bar{1}0)\), examined via both PBE and GW approaches53, and F-diamane(100), analyzed through PBE and HSE0638, similarly display a tendency to approach the bulk band gap with increasing thickness but with indirect band gap.

a Computed at the GW level band gap of F-diamane(111), F-diamane(110) and F-diamane\((10\bar{1}0),\) versus the number of layers. Red and blue horizontals are the band gaps of bulk diamond and lonsdaleite53. Inset: band projections in the first Brillouin zone for the conduction band minimum and valence band maximum26. b Correlating the computed carrier mobility μ (blue or red for e− or h+)26 and band gap Eg for F-diamane and H-diamane; bulk III-IV semiconductors (μ = 0.83 × 104 × Eg―3/2, solid line148), monolayer MoS2 and bulk Si shown for comparison. c Schematic of the double-gated F-diamane MOSFET61. d Comparison of the power-delay products versus τ relationship of the sub-7 nm F-diamane with other 2D materials-based MOSFETs for high performance applications. The solid and hollow symbols denote n- and p-type MOSFETs61.

The band gap of F-diamane varies almost linearly with applied strain. The slope coefficient varies significantly between different theory approaches. The PBE method predicts non-monotonic behavior of the coefficient with thickness, showing both maximum and minimum values at certain layer counts. In contrast, the GW approach suggests a consistent monotonic behavior of the incline coefficient with respect to the number of layers53. Machine-learning simulations show that F-diamane has almost no in-plane piezoelectricity in centrosymmetric AB stacking, but a linear response appears for asymmetric AA stacking. In contrast, H-diamane shows no piezoelectricity in either stacking. Under bending, F-diamane demonstrates flexoelectricity with a coefficient 153 pC/m, attributed to strain-gradient-induced polarization from π–σ and σ–σ electron interactions57. This value is higher than the flexoelectric coefficient of BN (2.93 D/rad = 85 pC/m)58, graphene (2.34 D/rad = 70 pC/m)59 and MoS2 (1.82 pC/m)60, underscoring F-diamane’s superior strain-gradient responsiveness and potential for nanoscale energy harvesting applications.

F-diamane(111) has an isotropic electron effective mass and modest anisotropy in the hole effective mass—attributes vital for a field effect transistor (FET) operation, in particular for a balanced n- and p-type MOSFET performance61. In ultrathin F-diamane(111) films, the electron effective masses can be lower than in bulk diamond (see Table 2); conversely, other effective mass values in F-diamane(111), as well as both the hole and electron effective masses in F-diamane(110) and F-diamane\((10\bar{10})\), exceed their bulk counterparts and increase monotonically with film thickness53.

It is supposed that carrier mobility is typically reduced with the increase of the band gap. An example of this is the data on bulk III-IV semiconductor compounds, where mobility depends inversely on the band gap. The calculated electron mobility in bilayer F-diamane (111) is as high as 2730 cm2/V s, about ~7 times larger than in the bulk III-IV semiconductors (extrapolated to the same band gap)26, see Fig. 3b. For F-diamane(0001) even larger value 16,550 cm2/V s was predicted27. Notably, the simulations incorporating full elastic and inelastic phonon scattering reveal room-temperature e− and h+ mobilities of 4390 and 10,100 cm2/V s, at 1014 cm−2 carrier density—exceeding most semiconductors61. This high mobility, despite the large band gap, arises from very low deformation potentials and suppressed ZA (flexural acoustic) phonon scattering in clamped device configurations. Simulations predict that F-diamane-based MOSFETs can reach subthreshold swings (SS) of ≈61 mV/dec for p-type devices at 7 nm channel length which suggests its superiority over H-diamane and most other 2D semiconductors61.

First-principles quantum transport simulations of sub-7 nm F-diamane MOSFETs (Fig. 3c) demonstrate on-currents (Ion) of 3084 μA/μm (n-type) and 1891 μA/μm (p-type) at channel length 7 nm, meeting ITRS high-performance applications requirements with intrinsic delay times τ ~ 0.017–0.024 ps and power-delay products of 0.012–0.107 fJ/μm, Fig. 3d. These metrics surpass the MoS2, GaAs, and Bi2O2Se-based devices, owing to F-diamane’s high mobility and low dielectric constant (1.75 ε0), which enhances gate electrostatic control. At channel length 3 nm, p-type devices achieve Ion = 1306 μA/μm with SS = 115 mV/dec, outperforming InSe and tellurene counterparts61. Comparative analyses with H-diamane remain limited, but F-diamane’s suppressed ZA phonon scattering and superior electrostatic integrity suggest a clearer pathway for sub-5 nm nodes.

Oxidized diamane

The formation of oxidized diamane (o-diamane)—a functionalized diamond film terminated by –O–, –H, and –OH groups—is relatively straightforward, as corroborated by experimental evidence. However, determining its precise atomic structure remains difficult because functional groups are distributed irregularly across the surface, similar to graphene oxide62. Models propose that these functional groups adopt non-stoichiometric arrangements, with their density and orientation contingent on the crystallographic facet of diamane. This surface-dependent functionalization generates a mosaic of local bonding configurations, complicating efforts to derive universal structural descriptors.

In cubic diamond–based films, o-diamane(111) with –OH and –H terminations forms a symmetric AB stacking stabilized by interlayer bonds39. In contrast, (100)-oriented surfaces favor ether (–O–) or methoxyacetone (–C = O/–O–) terminations, with ether groups displaying C–O bonds and methoxyacetone configurations featuring shorter C = O bonds, Fig. 4a63. Hexagonal lonsdaleite-derived o-diamane adds complexity: o-diamane\((\bar{2}110)\) with OH coverage and o-diamane\((10\bar{1}0)\) with OH coverage exhibit lattice distortions due to steric repulsion, while o-diamane(0001) with OH coverage mirrors cubic symmetry but with slight deviations in –OH orientation27. Stability thresholds vary significantly; (100)-oriented films require ≥6 layers to suppress phonon instabilities63, Janus-type architectures, such as o-diamane(111) with OH and H coverage (asymmetric –OH/–H termination), appear universally unstable due to interfacial strain and positive decomposition enthalpies39.

a Structure of o-diamane(100) with ether (-O-) and methoxyacetone (–C = O/–O–) terminations. The carbon and oxygen atoms are depicted by blue and red spheres, respectively63. b Structure of N-diamane(111). The carbon and nitrogen atoms are depicted by yellow and blue spheres, respectively43. c Structure of N-diamane(110). The carbon and oxygen atoms are depicted by black and green spheres, respectively66. d Structure of 3 L-B-diamane(111). The carbon and boron atoms are depicted by brown and green spheres, respectively67. e Structure of pyrimidinyl-substituted H-diamane(111). The carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen atoms are depicted by dark brown, light brown, and blue spheres, respectively30.

The mechanical response of o-diamane depends on both crystal orientation and surface termination. Cubic o-diamane(111) with OH coverage exhibits isotropic in-plane stiffness (~225–250 N/m/L), while hexagonal does display marked anisotropy. o-diamane(111) with –OH termination has a stiffness of about 262 N/m per layer, slightly higher than H-diamane(111)27. Parity-dependent oscillations in elastic constants emerge in (100)-oriented films63.

The electronic properties strongly depend on surface functionalization. (100) films terminated by methoxyacetone display larger indirect gaps (~3.1–3.3 eV) due to flat bands near the Fermi level, while ether-terminated analogs show smaller direct gaps (~1.3–1.8 eV, by GGA-PBE)63. o-diamane(111) with OH coverage direct gap is 3.1 eV, while o-diamane(0001) with OH coverage direct gap is 3.3 eV, by GGA-PBE27. Hydroxylation strongly affects the electronic structure. In o-diamane(111), the band gap changes from 3.0 eV (fully hydrogenated) to 3.5 eV (fully hydroxylated) and reaches 4.2 eV for mixed H/OH coverage (GGA-PBE). The electron effective mass decreases from 1.1 m0 in H-diamane(111) to 0.6–0.7 m0 in the hydroxylated form27,39. Carrier mobility varies dramatically: H-diamane(111) electron mobility is 137–144 cm2/V s, while the hydroxylated variant, OH-coated o-diamane(111), has a much lower e-mobility of 15–23 cm2/V s, influenced by electron-phonon coupling27. Hydroxylated films remain stable up to about 900 K owing to hydrogen bonding, while hydrogenated ones begin to degrade above 400 K39.

Other functional groups

While H–, F–, and O–based groups are the most common surface terminations, other types of functionalization have been studied to a lesser extent. Below, we summarize several computationally validated examples.

Nitrogen substitution in diamane introduces distinct stabilization mechanisms for its bilayer sp3-hybridized carbon lattice. Nitrogen substitution, particularly in the (111) surface orientation, stabilizes diamane without requiring further surface passivation. In single-sided nitrogenated diamane (π-C3N), Pandey π-chain reconstruction on the unpassivated side reduces dangling bonds and stabilizes the structure64. In contrast, double-side nitrogenated diamane N-diamane(111), with a vertical NCCN stacking configuration in Fig. 4b, achieves dynamic stability without surface reconstruction. The nitrogen substitution induces local sp2-sp3 rehybridization, modulating bond angles and interlayer interactions while preserving the diamond-like framework64,65. The work66 extends this stabilization principle to the “washboard” N-diamane(110) in Fig. 4c, where full nitrogen substitution (C4N4) achieves dynamic stability with no imaginary phonon frequencies, contrasting partially substituted C6N2/C5N3 phases. The washboard conformation arises from alternating surface ridges aligned along [110], stabilized by N-induced lone-pair electron redistribution. Things are quite different with boron, a naturally present counterpart of nitrogen. B-diamane(111) exhibits distinct layer-dependent stability: trilayer (Fig. 4d) or thicker films are dynamically and thermally stable, whereas bilayer configurations collapse via imaginary-frequency phonon modes and structural disintegration67. Recent study30 have extended diamane functionalization to organic groups such as methyl, pyrrolyl, triazolyl, phenyl, pyridinyl, and pyrimidinyl attached to H-diamane(111). These organically substituted variants retain structural integrity nearly invariant to type or surface coverage30. In contrast, logical in a series of functional groups of diamane, Cl-diamane exhibits low thermal resilience compared to H- and F-diamanes54.

N-diamane suggests exceptional mechanical resilience, N-diamond(110) displaying unparalleled in-plane rigidity among all 2D films, with normalized 2D elastic constants C11 = 323 N/m/L66, surpassing N-diamane(111) (284 N/m/L64, 308 N/m/L65), N-diamond(0001) (305 N/m/L65) and other diamane films like H-diamane(111) (232–251 N/m/L20,21,26,27,28,29,30). This orientation-dependent enhancement arises from the washboard-like sp3 lattice, where symmetric N substitution optimizes bond angles and minimizes surface reconstruction energy. Notably, N-diamond(110) approaches graphene’s in-plane stiffness 349 N/m20. Organically substituted H-diamanes exhibit mechanical properties close to H-diamane(111) which elastic constant C11 = 248–251 N/m/L consistent with covalent bonding dominance30.

Nitrogen functionalization induces wide band gaps, sensitive to computational methodologies. In N-diamane(111) a PBE-calculated indirect gap is 4.47 eV43, while HSE06 yields 6.1 eV64. For N-diamane(110), the HSE06-computed indirect gap is 3.5 eV, smaller than in its (111) counterpart66. Organic groups allow fine tuning of the band gap. HSE06 calculations30 give values from 2.1 to 4.9 eV depending on group electronegativity and surface coverage. For example, pyrimidinyl substitution (Fig. 4e) gives a gap of about 2.1 eV, triazolyl about 4.9 eV, while methyl and pyrrolyl groups keep it near-pristine value 3.8 eV. Mutual substituent orientation weakly perturbs band structures.

Cl-diamane(111) shows a direct band gap 2.48 eV by HSE0654, with valence band maxima dominated by Cl lone-pair electrons and conduction band minima arising from antibonding σ∗(C-Cl) states.

Reported thermal conductivities of N-diamane(111) differ between studies. Wang et al.43 predict a room-temperature thermal conductivity of 2288 W/m K (using machine-learning interatomic potentials) exceeding H-diamane(111) values 1960 W/m K41,42, or 2033 W/m K43, see Fig. 2d. This contrasts with refs. 68,69. value ~ 1540 W/m K at 300 K, obtained for N-diamane(111) and an even higher, 1626 W/m K at 300 K for N-diamane(0001)69, which may be related to some of the setting details used during the interatomic force constants extraction process43. The superior value of thermal conductivity of N-diamane(0001) is due to the increased relaxation time of the ZA mode and suppressed phonon scattering42,69. Cl-diamane(111) shows markedly lower thermal conductivity (146 W/m K, at 300 K), caused by heavier functional groups as well as increased optical mode contributions45.

Twisted diamane

The interplay between stacking order and interlayer bonding in twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) may offer a fertile platform for engineering diamond-like films. Twisted diamanes derived from TBG show different structures at various twist angles, θ. At small twist angles (θ < 13°), moiré superlattices with periodic AA and AB domains form, separated by AA′ interphase. These regions enable the growth of ordered nanodiamond clusters (Fig. 5a)70,71. At larger twist angles the structure develops fullerene-like regions (Fig. 5b)71,72. At 30°, the loss of lattice commensurability produces a 2D quasicrystal with irregular bonding73.

a Atomic structure of superlattice of (cubic) diamond-like interlayer-bonded domains embedded in a 9.43° twisted bilayer71. b Atomic structure of caged fullerene-like interlayer-bonded domains embedded in a 30° twisted bilayer71. c Atomic structure of fully diamondized bilayer bigraphene with twisted angle close to 30° (27.8°)76. d Dependence of the formation energy on the number of attached H atoms on the surface of the bigraphene island with 5° misoriented layers; insets illustrate the growth stages of 2D diamond: for the bigraphene structure with the maximum number of hydrogen atoms the local crystal lattice is analyzed; carbon atoms having the environment as in the cubic diamond phase are shown by blue, those in the hexagonal diamond phase are shown by orange; insets show the side view of the structures70. e Structure of the diamane quasicrystal cluster C516H32873.

The thermodynamic mechanisms governing diamane formation in TBG remain unclear. Some works28,71,74 suggest that only limited formation of diamond domains occurs in the graphene structure, accompanied by the graphene/diamond interfaces. The possibility of complete transformation of graphene into diamond has been postulated in other works55,73,75,76, including the cases at large twists (Fig. 5c). To clarify this issue, a comprehensive thermodynamic model of the diamane nuclei is needed, one attempt in ref. 70, considered a twisted angle of 5°. The model shows that larger diamane nuclei become more stable, forming connected regions of cubic and hexagonal diamond (Fig. 5d).

MD simulations74 elucidate the mechanical behavior of low-angle twisted diamanes (5.086° ≤ θ ≤ 9.43°) under nanoindentation. At sp3 bond densities below a critical threshold \({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\) < 4.1%, these structures exhibit nonlinear inelastic deformation mediated by the torsional reconfiguration of nanodiamond clusters beneath the indenter. This nondissipative stiffening mechanism, absent in high-\({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\) regimes, leads to pronounced hysteresis. Remarkably, the deformability (δmax ≈ 45–55 Å) remains robust across \({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\), values while the elastic modulus (275 N/m/L at \({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\) = 22.13%) and strength declines at greater diamond content, in accord with MD of tensile loading in low-angle twists (θ = 9.43°, 13.17°)28. In contrast, interlayer shear modulus of low-angle diamanes rises with \({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\), reaching 170 GPa for ordered superlattices—nearly triple the values in randomly bonded systems—due to the synergistic rigidity of clustered sp3 bonds28. Fracture initiates mostly at nanodiamond-graphene interfaces, propagating via bond rupture and forming monatomic carbon chains74. Notably, fully interlayer-bonded structures (\({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\) = 1) have higher fracture strains than hybrid sp2/sp3 systems, suggesting that interfacial defects in partially bonded superlattices accelerate crack nucleation28. The dependence of mechanical properties on sp3 bond density allows one to obtain intriguing mechanical behavior, e.g., by adjusting the \({f}_{s{p}^{3}}\), to achieve zero thermal expansion of twisted diamane over a wide temperature range77.

Functionalization with hydrogen or fluorine enables control of the electronic structure, including the band gap and Fermi velocity. These parameters also depend on the arrangement of interlayer-bonded domains in TBG71. First-principles calculations confirm that fluorination transforms TBG’s Dirac semimetal-state into a semiconductor, with flat bands emerging across the spectrum. The electronic states of these covalent moiré superlattices are localized at AB/BA domain walls, akin to quantum defect centers75. Such atomic-scale tailoring, with twist engineering, positions low-angle diamanes as versatile platforms for advanced nanoelectromechanical systems.

High-angle twists (θ ≈ 13–30°) leads to distinct structures characterized by fullerene-like interlayer bonding patterns. Ab initio studies of H- and F-diamanes at θ = 27.8° and 29.4° reveal wide band gaps of 3.3–3.6 eV and 4.1–4.5 eV (GGA-PBE theory level). As Table 1 (H-diamane) and Table 2 (F-diamane) shows, these are larger than in non-twisted diamonds calculated using the same approach. These gaps arise from a combination of strained sp3 networks and hybridized 3–3’ and 5–5’ carbon rings, which induce localized states near the band edges76.

Thermal conductivity at 300 K of the high-angle twist diamanes reveals a paradoxical trend: moiré H-diamanes at θ = 27.8° having ultra-low κ = 32 W/m K, while F-counterparts have higher κ = 90 W/m K, both much lower than non-twisted diamanes. The anomalous-low κ in high-angle systems (θ = 21.8°–27.8°) H-systems correlates with heightened anharmonicity (seen in Grüneisen parameter exceeding it in F-variants) which amplifies phonon scattering and suppresses thermal transport. Another noteworthy observation is the distinct dependence of κ on the moiré angle. Consequently, while the thermal conductivity of F-diamane changes with angle monotonously, a discontinuity (occurring between 13.2° and 21.8°) is observed in H-diamanes55.

At the high-angle twists (θ ≈ 30°), F- and H-diamanes adopt a quasiperiodic structure of diamane quasicrystals (DnQC), of six-fold rotational symmetry but non-repeating translational order73. These intrinsic 2D quasicrystals, formed from 30°-twisted bilayer graphene, exhibit reconstructed Stampfli tiling with rhombuses, triangles, and squares arranged in aperiodic yet symmetric patterns, Fig. 5e. From a simulation perspective, the lack of periodicity makes accurate modeling difficult. Researchers typically address this by introducing artificial strain72 or by modeling large isolated clusters73. The DnQC’s MD-simulated response to nanoindentation reveals a stiffness 16% higher than AB-stacked diamanes, due to a 19% denser C–C bond network (1.88 vs. 1.57 bonds/Å2), despite having similar sp3 hybridization73. This contrasts with prior discussed stiffness reduction in low-angle systems under tensile strain28,74, highlighting the unique resilience of quasicrystalline architectures.

Electronic structure calculations for DnQC clusters (θ = 30°) demonstrate band gaps of ~3.5 eV for hydrogenated variants and >4 eV for fluorinated ones, surpassing AB-diamane (3.1 eV) and approaching bulk diamond (4.2 eV at GGA-PBE level)73. Fluorination further stabilizes DnQC, reducing formation energies to −0.28 eV/atom—comparable to diamond—while hydrogenated DnQC remains less stable (0.13–0.14 eV/atom). The coexistence of ultrawide band gaps and quasi-amorphous bond length distributions (1.50–1.66 Å) positions DnQC as a bridge between crystalline diamond and disordered carbon phases.

Diamane with pristine surface

Diamane films with pristine surfaces are metastable systems, due to destabilizing unsaturated bonds, causing pronounced interfacial stress. This stress can trigger structural instability through two main pathways: surface reconstruction or graphitization. Ultrathin diamond films, especially bilayer diamane, are highly susceptible to this degradation because reduced thickness intensifies strain propagation. Even in thicker films, residual surface stress persists, though mitigated by bulk rigidity. Stability also depends on crystallographic orientation. For example, the (100) surface tends to reconstruct through π-bonded chains, while the (111) is prone to graphitization, meaning orientation-dependent (anisotropic) stability. Theory models and recent experiments suggest that a thick enough pristine-surface diamane becomes thermodynamically stable, and may be realized in experiment.

The structural integrity of pristine diamane depends on layer number and crystallographic orientation. For (111)-oriented films, a critical threshold of L ≥ 5 stabilizes the diamond lattice10,15,37, suppressing graphitization. The (110) surface, inherently stable against reconstruction due to its lower surface energy, avoids graphitization even at elevated temperatures, distinguishing it from (111)-oriented systems. Only the thinnest bilayer (110) diamane reconstructs into planar graphene, while thicker films retain the diamond lattice with minimal surface relaxation37. In contrast, (100)-oriented films exhibit distinct stabilization mechanisms. Pristine (100) films exhibit stability even at minimal thickness, undergoing surface reconstruction solely to mitigate dangling bond instabilities15,78, reaching a 2 × 1-reconstruction with characteristic C = C dimers, akin to bulk diamond surface79. Notably, two additional dynamically stable configurations emerge: 5–7-membered ring assemblies and hybrid 5/5–7-membered ring architectures78. In a pristine diamane derived from hexagonal diamond (lonsdaleite), stability is achieved at atomic layer counts L = 2, 3, and 6 for \((\bar{2}110)\), \((10\bar{1}0)\), and (0001) surfaces, respectively. Consequently, the (0001)-oriented film emerges as the least stable within this structural hierarchy21.

Motivated by the synthesis of 2D diamond inclusions within graphene matrices under rapid heavy ion irradiation (see the Diamondization under electron and ion irradiation section), a hybrid carbon model was thoroughly investigated via MD simulations80. It suggests that only (100)- and (110)-surface diamond films are attainable by this method, with other orientations prone to graphitization via surface-mediated mechanisms. Clusters with (100) surfaces become stable only if thicker than six atomic layers; thinner ones turn amorphous. Conversely, (110)-surfaced clusters stabilize at L ≥ 4 thicknesses, with ultrathin configurations always yielding to graphitization. Lateral dimensions of pristine diamane clusters do influence their stability within graphene hosts. Sub-5 nm clusters display marked susceptibility to amorphization, driven by interfacial strain disparities between the sp3-hybridized diamond core and the sp2-graphene envelope. Clusters exceeding 5 nm, however, attain thermodynamic equilibrium, as volumetric bonding energetics supersede interfacial strain perturbations.

The mechanical response of pristine diamane is intricately linked to its crystallographic orientation and hybridization state. For (111)- and (100)-oriented films, theoretical elastic moduli approach ~1 TPa, as for 3D diamond. Simulation indentation studies on irradiated graphene/diamond hybrids reveal extraordinary local stiffness: for (100)-oriented clusters, a Young’s modulus of ~8.9 TPa, while (110)-oriented regions reach ~4.3 TPa, surpassing pristine graphene (~1 TPa). This enhancement arises from covalent sp3-bonded networks within diamond domains, which resist deformation more effectively than sp2-rich matrices. However, the hybrid structures display increased brittleness, with critical indentation depths reduced to 7.5 Å (100) and 17.3 Å (110), compared to 23.3 Å for 9-layer graphene80.

The apparent contradiction between the hybrid’s high local stiffness and its slightly reduced in-plane elastic modulus (0.9 TPa) stems from measurement methodology. During uniaxial stretching, the graphene matrix dominates the composite’s macroscopic response, as its sp2 network accommodates strain more readily than the rigid diamond clusters. Conversely, nanoindentation probes localized regions81,82, where the diamond phase’s covalent bonds resist deformation, yielding anomalously high stiffness values. This dichotomy underscores the importance of measurement technique in interpreting mechanical properties: while in-plane stretching reflects bulk-averaged behavior, indentation highlights the superior rigidity of embedded diamond domains.

Layer- and orientation-dependent electronic transitions underscore the structural evolution of pristine diamane. For (111)-oriented films of L ≥ 12 reach a wide indirect band gap ~4.1 eV, while surface states introduce mid-gap levels83. Conversely, (100)-oriented films exhibit reconstruction-dependent band gap engineering: 2 × 1-reconstructed surface patterns (L ≥ 6) display small band gap of 1.02–1.40 eV (PBE) or 2.09–2.40 eV (HSE06), suitable for visible-light photocatalysis. The 5–7-membered ring configurations yield narrower gaps (0.32–0.55 eV), while 5/5–7-membered ring structures are metallic due to surface-state hybridization78. For (110)-oriented films, pristine configurations also exhibit metallic behavior driven by unsaturated dangling bonds on the surface. Density of states analysis confirms that p-orbital electrons dominate near the Fermi level, while s-orbital contributions are negligible37.

Diamane doping

Unlike bulk diamond, whose dense 3D lattice resists doping, diamane’s nearly 2D structure allows controlled functionalization through substitutional, interstitial, or surface doping. Examples include fluorinated (F-diamane), hydrogenated (H-diamane), and oxygenated (O-diamane) forms. Computations show that dopants such as B84,85,86,87, N84,85,87,88, S88, Si16, P89, Li89, Cu90, and Sc91 as well as molecular adsorbates92, can significantly tune diamane’s electronics. This makes doped diamanes promising for quantum and nanoelectronic applications.

The electronic structure of doped diamane is sensitive to the choice of dopant and defect engineering. Substitutional B or N doping causes minimal lattice distortion (<2% bond elongation) and slightly reduces the LDA band gap from 4.05 eV (pristine H-diamane(111)) to 3.71 eV (B-doped) and 3.99 eV (N-doped)88. Nitrogen behavior depends on its site. External substitutional N (without hydrogen) increases the GGA-PBE band gap to 3.43 eV in cubic diamane, whereas internal N creates metallic states because of unpaired electrons87. Boron doping in H-diamane(111) introduces substantial electronic modulation. Substitutional B atoms preferentially form vertical B–B dimers. The GGA-PBE band gap of B-doped H-diamane is concentration-dependent, decreasing from 1.82 eV (3.125 mol%) to 1.44 eV (6.25 mol%) in H-diamane(111) due to enhanced B–B dimer interactions. Certain metastable B configurations produce metallic states with superconducting transitions near 4 K, similar to bulk B-doped diamond86. Codoped B-N systems exhibit tunable band gaps (2.27–2.82 eV, GGA-PBE), intermediate between pristine H-diamane and metallic N-doped variants87. In F-diamane, B-N codoping also reduces the band gap from 4.04 eV (pristine F-diamane, GGA-PBE) to 3.03–3.98 eV depending on mutual arrangement of B and N atoms85.

Sulfur doping strongly distorts the lattice because of its larger atomic size. The S atom shifts to a quasi-threefold position about 2.9 Å from the lattice, reducing the LDA band gap to 1.4 eV88. Phosphorus, despite its larger atomic radius (1.10 Å vs. 0.77 Å for C), stabilizes substitutionally in H-diamane as an n-type dopant, though it induces significant bond elongation (1.721 Å vs. 1.540 Å for C–C) and reduces the GGA-PBE band gap to 2.30 eV89. Lithium, conversely, adopts stable interstitial configurations with minimal lattice distortion (bond angles ~111.89°) and acts as a shallow n-type donor, further narrowing the GGA-PBE band gap to 2.0 eV89. Silicon, despite its larger atomic radius (1.18 Å vs 0.77 Å for C), can be stably incorporated into H-diamane. It forms substitutional sites with only a small band gap reduction (2.92–2.98 eV compared with 3.04 eV in pristine H-diamane at GGA-PBE level). This resilience underscores diamane’s capacity to host oversized dopants, a feat unattainable in bulk diamond due to steric constraints16. In F-diamane, fluorination stabilizes surface N atoms via polar covalent B-F bonds, suppressing lone-pair electron localization and enabling isotropic electronic behavior85. In the context of B-N-codoped diamane, the presence of B and N atoms in adjacent positions, with a B-N distance of approximately 1.6 Å, results in structures exhibiting comparatively lower energies. Conversely, structures with significantly greater B-N distances exhibit higher energy characteristics. The configuration with a direct B–N bond is the most stable because of the attraction between the electron from N and the hole from B. The lowest-energy structure has N at the external substitutional site and B at the internal site, forming a nearest-neighbor B–N pair. Band gaps in codoped systems are tunable between 2.27 and 2.82 eV (GGA-PBE), intermediate between insulating pristine diamane and metallic N-doped variants, rendering them ideal for broadband optoelectronic applications87.

Vacancy–dopant complexes further tune electronic behavior. In H-diamane, intrinsic vacancies \({V}_{C}\) create mid-gap states and reduce the band gap to about 1.8 eV, with charge states \({V}_{c}^{+1}\), \({V}_{c}^{-1}\). Small shifts in ionization energies (0.002–0.011 eV) indicate that these defects act mainly as acceptors89. Charged states (NV−, NV0, NV+) exhibit distinct electronic behaviors: NV− introduces mid-gap states localized at defect sites, reducing the LDA band gap to 0.61 eV, while NV0 and NV+ yield gaps of 0.67 eV and 0.95 eV, respectively. Having NV centers in diamane always near the surface is promising for nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging and qubit applications. 2D geometry avoids the depth-related limits of bulk diamond NV centers88. The paramagnetic NV center shows a radiative transition rate of about 1 GHz at 2.02 eV—much higher than the ~97 MHz rate in bulk diamond. This improvement results from smaller Bohr radii (≈5.5 Å vs 7 Å) and higher photon extraction efficiency93,94. These defect-engineered states enhance optical absorption in the visible and infrared regions (1–3 eV), a stark contrast to pristine H-diamane’s UV-dominated spectrum, thereby broadening applications in photodetection and quantum sensing16,89. Phosphorus-vacancy (P-V) complexes in H-diamane shift the Fermi level into the valence band, converting n-type to p-type semiconductivity with a collapsed band gap of 0.50 eV. Similarly, lithium-vacancy (Li-V) interactions destabilize interstitial configurations, emphasizing the delicate balance between dopant placement and defect proximity in modulating carrier types89. Such defect-mediated transitions in diamane highlight its potential for bifunctional electronics, spanning both hole- and electron-dominated conduction regimes.

Silicon-vacancy SiCVC centers introduce localized electronic states within the band gap, enabling spin-dependent functionality. In paramagnetic SiCVC configuration, two spin-split intermediate bands emerge near the Fermi level, yielding a magnetic moment of 2 μB and enabling selective optical transitions. Nonmagnetic SiCVC variants retain flat intermediate bands but lack spin polarization, illustrating the critical role of vacancy-dopant spatial arrangement in defining magnetic ground states16.

Because substitutional doping often causes scattering and reduces carrier mobility, near-surface transfer doping has become an effective alternative for diamond. Already accepted for the latter95,96 this subsurface doping must be even more applicable to the “all-subsurface” diamanes. Indeed, transfer doping occurs via molecular adsorption, enabling degenerate p- and n-type doping in H-diamane and F-diamane, respectively. Organic acceptors (e.g., tetracyanoethylene, TCNE) and transition-metal oxides (e.g., MoO3) adsorbed on H-diamane induce hole accumulation, achieving degenerate p-type conductivity with carrier concentrations of 1.91–3.96 × 1013 cm−2. Conversely, donor molecules like decamethylcobaltocene (DMC) on F-diamane facilitate electron injection, yielding degenerate n-type doping with concentrations up to 1.96–3.38 × 1013 cm−2 92. This approach avoids lattice distortion and allows precise control of carrier density, complementing traditional substitutional doping.

Doped diamane exhibits tunable optical properties distinct from bulk diamond. The static refractive indexes of H-diamane with intrinsic defect (Vc0, Vc+1 and Vc−1), interstitial P-V and interstitial Li are 1.73 (1.75, 1.74 for \({V}_{c}^{+1}\) and \({V}_{c}^{-1}\)), 1.72, and 1.70, respectively. These values are markedly lower than that of bulk diamond (2.20)89. Adsorbed molecules increase visible-light absorption, e.g., H-diamane with tetracyanoquinodimethane shows new peaks at 1.1–1.4 eV and 2.5–2.9 eV, while F-diamane with decamethylcobaltocene adsorbate exhibits stronger absorption at 2.7–3.1 eV92.

Thermodynamics and mechanisms of formation

The remarkable properties of diamane, discussed so far—structural, electronic, mechanical—motivate the quest for its syntheses, through better understanding of thermodynamic factors controlling 2D-diamond formation. This section explains how ultrathin diamond-like films form from graphene through chemistry-driven transformations, at moderate pressure.

Pressure-driven formation

The equilibrium phase diagram of bulk carbon, defined by pressure and temperature, determines the stability of its main allotropes: graphite, diamond, and carbyne. At ambient pressure, graphite is the stable phase. Diamond becomes thermodynamically favorable above about 2 GPa at moderate temperatures. The graphite-diamond-liquid triple point resides near 12 GPa and 4500 K, with the diamond-liquid boundary exhibiting a positive slope in the P-T plane, reflecting diamond’s higher density and entropy upon melting97.

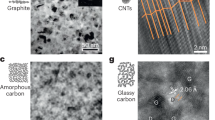

At the nanoscale (<10 nm), carbon’s phase behavior deviates markedly from bulk predictions due to surface energy dominance and curvature-induced strain. The lack of surface passivation leads to formation of hybrid “bucky-diamond” structures—comprising a diamond-like core encased in fullerene-like shells—as intermediaries during phase transitions98. These configurations alleviate surface strain, stabilizing nanodiamonds down to ~1.8 nm, consistent with experimental observations99. These findings challenge classical thermodynamic frameworks, necessitating atomistic descriptions of surface reconstructions and interfacial kinetics in nanoscale phase diagrams.

Similar to nanodiamonds, the graphene–diamane transition is strongly influenced by dimensional effects and surface energy. Monolayer graphene transitions to diamane—a bilayer diamond film—under compressive strain, but intrinsic stability limits arise from the dominance of surface energy in ultrathin systems. For unpassivated diamane, the critical pressure p required for graphene-to-diamane conversion follows \(p > \delta +\sigma /h\), where δ and σ represent bulk and surface energy contributions normalized per volume reduction, and h is the film thickness4. For few-layer graphene, the surface term σ becomes dominant, necessitating enormous pressures to stabilize diamane10. Thus for few-layer graphene this equation predicts a sharp rise in required pressure as h decreases (Fig. 6a, b). It consists with experimental observations of few-layer graphene diamondization at 15–50 GPa100,101,102, while bilayer systems demand from 160100 to 240 GPa103(Fig. 6c). High-pressure Raman studies confirm the reversible transitions without permanent diamondization when using inert pressure-transmitting medium (PTM)13,104. These facts highlight the absence of a practical P-T window for equilibrium coexistence. Although bulk diamond is strikingly-well metastable, preserved by kinetic barriers, its ultrathin films do favor sp2-bonding. This shift toward graphene highlights how dimensionality destabilizes sp3-bonded 2D phases.

a The dependence of the phase transition pressure P on the inverse film thickness h at T = 0 K and 1000 K (solid and thin lines) for films with pristine surfaces. b The phase diagram P(T) for the n-layer graphene to a diamane(111) with pristine surface, for a different number of layers10. c Left: pressure-dependent number of sp3-hybridized atoms in a bilayer graphene film, utilizing inert atoms (red line) and TaC surfaces (blue line) as PTMs. Right: the initial structure of bigraphene (prior to pressure application) and the subsequent structure following pressure application, employing inert atoms (illustrated by a red box) and TaC surfaces (illustrated by a blue box)116. d The dependence of the phase transition pressure on the inverse film thickness h at T = 0 K and 1000 K (solid and thin lines) for films with hydrogenated surfaces. e The phase diagram P(T) for the transitions from a multilayer graphene to a H-diamane(111), for different number of layers10. f Potential energy curves show the transition from bilayer graphene with complete coverage with atoms from H2, F2, H2O, and NH3 into diamond films (chosen as zero energy level). All energies are plotted versus the average length of surface bonds. The schematics at the inset illustrate the initial and final structures. The potential energies for binding the molecular and atomic form are marked by solid and dashed lines, respectively110.

These results agree with theoretical predictions: few-layer graphene (L ≥ 3) reaches critical pressures near 15 GPa due to a lower surface-to-volume ratio (Fig. 6b)10,21. Only bilayer diamane with the surface orientation \((\bar{2}110)\) is predicted to remain stable21. While certain bilayer diamond films with other specific surface orientations demonstrate stability (see Diamane with pristine surface paragraph), their atomic structure precludes the prospect of their formation through the connection of graphene sheets due to incompatible atomic geometry.

Chemically induced phase transition

The stability of nanodiamond structures is intrinsically linked to surface passivation, which suppresses reconstructions and preserves sp3 hybridization. Hydrogenation eliminates dangling bonds, preventing delamination of surface facets and inhibiting transitions to graphitic or onion-like carbon phases105. First-principles and semiempirical studies reveal that the thermodynamic preference for hydrogenated sp3 configurations over sp2 is size-dependent, with stability reversal occurring 3–7 nm106,107.

The transition from graphene to diamane under chemical passivation represents a distinct class of phase transformations, termed chemically induced phase transitions. In contrast to pressure- or temperature-driven transitions, chemical functionalization with reference atoms (e.g., H, F) modifies the thermodynamic balance by stabilizing sp3-bonded networks. Theoretical frameworks reveal that the stabilization arises from the passivants’ ability to saturate dangling bonds, thereby reducing the surface energy of the system and shifting the phase boundary toward diamane formation at ambient or modest pressures10.

Central to this phenomenon is the interplay between passivant binding energy and film thickness. For fully passivated systems, the Gibbs free energy difference between graphene and diamane phases predicts spontaneous diamondization for ultrathin films (h < |σ | /δ), see Fig. 6d4. Early models posited that complete surface functionalization could stabilize diamane in films up to ~30 layers (~10 nm) without external pressure (Fig. 6e)10. However, this idealized scenario neglects the kinetics of stepwise passivation and interlayer bonding dynamics. Detailed first-principles studies demonstrate that the sequential adsorption of passivants on bilayer graphene induces a barrier-free sp2→sp3 transition, driven by the exothermic binding of H9,10,17,21,108,109,110 or F9,109,110,111 atoms (~6 eV per atom54). The process propagates coherently across the bilayer, forming AB, AA, AA’-stacked diamane with minimal energy penalties, as the absence of interlayer stacking mismatches allows uniform hybridization. A similar effect can be observed in other stackings allowing diamond films with other surfaces. Moreover, studies based on MTP8 demonstrate that hydrogenation of TBG (exemplified by 5°-twisted graphene) increases formation energy with H coverage, stabilizing diamond nuclei and driving interfacial bond propagation with formation of coexisting (111), \((10\bar{1}0)\), and (0001) diamane regions together (see Fig. 5d)70. Such coexistence can also be achieved by hydrogenating grain boundaries, which seeds hydrogenation fronts that propagate anisotropically, yielding chemically bonded grains with distinct crystallographic orientations (e.g., cubic (111) and hexagonal \((10\bar{1}0)\) surfaces) and interfacial energies comparable to graphene-graphane boundaries (~1.3 eV/Å)112.

Note that the process of chemical-induced phase transition can be achieved not solely through the utilization of hydrogen and fluorine. It is imperative to acknowledge the potential of oxide groups39,109,110, ammonia110, as well as other groups that possess the capacity to form robust sp3 bonds with the diamond surface. These groups must also exhibit a steric radius that is sufficiently diminutive to facilitate dense packing on the diamond surface.

For thicker films (L > 2), nucleation barriers appear because of geometric constraints on interlayer bonding. Functionalization induced diamondization starts at the outer layers, while the inner ones remain sp2-hybridized. This creates a metastable state where partial sp3 domains coexist with unreacted graphene regions. The energy needed to extend the diamond phase increases with thickness because interlayer bonding requires simultaneous rehybridization of several carbon layers. This process is additionally hindered by stacking faults and van der Waals gaps. Overcoming these barriers requires localized pressure to compress interlayer distances, facilitating covalent bond formation between adjacent graphene sheets9. For instance, trilayer graphene functionalized with hydrogen achieves partial diamondization under mild pressures (~10 GPa)9, whereas unpassivated systems require pressures 15–50 GPa100,101,102. This synergy between chemistry and mechanics underscores the necessity of combined stimuli for thicker films, distinguishing the process from the purely chemical pathway viable in bilayers.

Moreover, the process of functionalizing the graphene surface requires energy (if we do not assume the use of cold atomic plasma) for the breakdown of the adsorbent molecule. For example, in the case of a hydrogen molecule, 2.29 eV/H is required hindering graphene hydrogenation113.

Thus, even bilayer diamond formation faces an energy barrier related to molecular dissociation. This phenomenon was demonstrated in the complete coverage of graphene with atoms derived from H2, F2, H2O, and NH3 (Fig. 6f)110. Since diamond formation proceeds from nucleation, additional constraints arise for initiating the process. Investigations into defective graphene systems elucidate the critical role of structural imperfections in ameliorating nucleation barriers. Monovacancies, Stone–Wales defects, and grain boundaries act as preferential sites for passivant adsorption, lowering the barrier for initial hydrogenation by 1–2 eV compared to pristine regions112. This defect-assisted pathway is especially important when hydrogen is supplied as H2. In pristine graphene, nucleation requires adsorption of over 70 H atoms, but vacancies and grain boundaries reduce this barrier112.

Substrate interactions play a pivotal role in modulating the chemically induced phase transition from graphene to diamane, with metal surfaces acting as both structural templates and chemical stabilizers. Early theoretical studies by Odkhuu et al.114 demonstrated that the hybridization between sp3 carbon orbitals and metal d-orbitals—particularly in transition metals like cobalt (Co) and nickel (Ni)—enables the stabilization of diamane films. These studies emphasized the critical role of hydrogen or fluorine coverage in triggering the transition from sp2 to sp3 hybridization, with Ni and Co substrates offering superior stabilization due to their strong interfacial bonding and lattice compatibility. Copper (Cu), while less reactive, was shown to stabilize sp3 configurations at higher reference atom coverages, albeit with reduced efficiency compared to Ni.

Varlamova et al.115. provide a granular analysis of nucleation dynamics and substrate-specific energetics during diamane formation. Their work corroborates the superiority of Ni as a substrate, attributing its efficacy to a near-perfect lattice match with diamond (2.49 Å vs. 2.52 Å) and robust interfacial C–Ni bonds (2.1 Å). These factors significantly lower nucleation barriers, enabling spontaneous diamane formation at pressures as low as 3 GPa. For Cu, however, inherent limitations were revealed: lattice mismatch (3%) and weaker C–Cu interactions lead to structural buckling and elevated energy barriers during compression, consistent with ref. 114 that Cu necessitates higher reference atom coverage for stabilization.

In contrast, platinum (Pt) exhibits a pronounced lattice mismatch (6%) with graphene, resulting in partial interfacial bonding and corrugated graphene layers. However, Pt can store atomic hydrogen in its lattice. On heating, this hydrogen desorbs and passivates the graphene surface, promoting interlayer bonding115.

The compression simulations in ref. 115 further elucidate substrate-dependent behaviors. Whereas the surface convergence of Ni, Cu and Pt does not result in the formation of a stable diamond film between the metal surfaces, Ni forms strained diamond films under compression (C–C bonds elongated by 14%) but Cu exhibits no stable diamond nucleation within the studied pressure range due to its pliable C–Cu bonds (compressing from 3.04 to 1.98 Å without structural coherence).

The findings116 resolve a critical limitation in the former study: TaC not only reduces the conversion pressure to 22.2% of pure compression thresholds (55–60 GPa vs. 210 GPa for helium-mediated systems) but also stabilizes the diamond structure post-decompression (Fig. 6c). Charge-density analysis shows strong Ta–C and C–C interfacial bonds that remain after pressure release. These bonds saturate sp3 sites and prevent re-graphitization. In contrast, TiC-mediated systems mirror the behavior of pure metal substrates in ref. 115, reverting to graphene below 15 GPa due to weaker Ti–C interactions and insufficient bond saturation.

Theoretical insights from ref. 117 introduced a novel pathway for stabilizing diamane through substrate-derived chemical functionalization. The study proposed that focused electron beam irradiation liberates hydrogen from PMMA and oxygen from the langasite (La3Ga5SiO14, LGS) substrate which functionalize opposing surfaces of bilayer graphene. Oxygen atoms from LGS form covalent bonds with interfacial carbon atoms, inducing localized sp3 hybridization and interlayer C–C bonding. The optimized hexagonal diamane structure \((10\bar{1}0)\) surface is hydrogen-terminated on the outer side and anchored to LGS-derived oxygen at the interface. This stability arises from oxygen’s strong electronegativity and directional bonding, which mitigate lattice strain and suppress re-graphitization.

Experimental validation

What started from the theoretical-computational analyses, offering insight into chemically induced phase transformations, is now supported by multiple experimental reports, reviewed in this section.

Experimental evidence for H-diamane, F-diamane, o-diamane

Piazza et al.118 reported pressureless conversion of ultrathin carbon films into sp3-bonded structures through controlled hydrogenation. Raman and FTIR spectroscopy revealed vibrational modes characteristic of diamond-like ordering. The process avoided extreme pressures by using precise thermal and chemical control to promote interlayer bonding. Follow-up studies by ref. 119 further corroborated these findings, revealing that hydrogenation of bilayer graphene produced coherent diamane domains, as evidenced by sharp diffraction patterns and appearance of peaks associated with sp3-hybridized bonds.

The role of substrate interactions in facilitating hydrogenation-driven diamondization was elucidated in ref. 120, an observation of hydrogen adsorption on Pt(111)-supported graphene to prompt localized sp2-to-sp3 transitions. This highlighted the importance of metal substrates in stabilizing intermediate states during chemical functionalization, though the resulting films exhibited only partial crystallinity.

Notwithstanding, most of the successful experiments to date have been on diamane formation via fluorination, a consequence of the relative simplicity of this process in comparison to hydrogenation. A seminal work by Bakharev et al.121, demonstrates not only the feasibility of the chemically induced phase transformation but also provides unprecedented structural validation through high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Bakharev et al.121, employed xenon difluoride (XeF2) as a fluorinating agent to convert CVD grown bilayer graphene on a CuNi(111) substrate into a fluorinated diamane structure. The transformation was corroborated by a suite of spectroscopic and microscopic techniques. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed the formation of C–F bonds, while Raman spectroscopy exhibited characteristic peaks consistent with sp3 hybridization. Crucially, TEM imaging unveiled a highly ordered atomic arrangement, with interlayer distances and diffraction patterns aligning precisely with DFT predictions for F-diamane(111), see Fig. 7a. This congruence between experimental observations and theoretical models marked a milestone in the field.

The inner area of the figure shows schematics of approaches: chemically induced phase transition (functionalization of graphene12,13,31,104,117,118,119,120,121,129, exfoliation of diamane layers from functionalized (fluorinated) graphite123,124 and indentation of bigraphene which is transformed into diamane due to chemical binding with indenter and substrate11,32,131, as well as diamondization of graphene under the influence of high-energy ion irradiation80,134. Also shown are the most striking manifestations of these approaches: a cross-sectional TEM image of F-diamane(111) obtained by fluorination of bilayer graphene121. b TEM image of an exfoliated F-diamane(111)124. c The current drop in 2 L graphene films on SiC during the indentation, indicating that at loads >260 nN, bigraphene transforms to a structure with a larger sp3 content, more resistive (in the 5 L film, the current only rises with larger normal load, consistent with the increase in contact area and hence the electrical contact between tip and film without the diamondization)32. d TEM images of nanosized diamonds embedded in few-layer graphene films irradiated with high-energy Xe ions80.

Substrates further modulate fluorination efficacy, as shown by Son et al.122, where bilayer graphene on hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) underwent selective top-side fluorination, whereas rough SiO2 substrates permitted bilateral functionalization. Despite these achievements, challenges persist in achieving uniform diamondization across multilayer systems. Recent work123 introduced a scalable top-down approach utilizing expandable graphite as precursors. Fluorination with molecular fluorine (F2) at optimized temperatures (380–430 °C) yielded graphite fluoride (C2F)n. Subsequent mild sonication in chloroform exfoliated the material into F-diamane-like nanosheets, hundreds of nanometers to micrometers wide and less than 10 nm thick. The expanded graphite’s vermicular structure facilitated homogeneous fluorine dispersion, as evidenced by XPS and solid-state 19F NMR, which revealed predominantly covalent C–F bonding (688.7 eV) and minimal residual sp2 carbon. TEM and selected-area electron diffraction confirmed hexagonal symmetry and ~0.9 nm interlayer spacing consistent with F-diamane. EELS showed suppressed π* transitions, confirming the shift from graphitic to diamond-like bonding. This methodology fulfilled the earlier efforts124(Fig. 7b), who exfoliated fluorinated graphite but required high-power sonication, risking defluorination and fragmentation. The expanded graphite’s low coherence length along the c-axis reduced exfoliation barriers, enabling the production of larger, defect-minimized nanosheets—a critical advancement for scalable synthesis. It is imperative to acknowledge that the presented works reflect older studies125,126,127 on graphite fluorination, in which stacked “diamane” C2F layers were identified.

Ref. 128 studied fluorination mechanisms using nanographene molecules such as hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene (HBC), pyrene, and perylene to model the free-radical cross-linking process. Direct fluorination of HBC with F2/N2 mixtures induced covalent intermolecular bonds without substrate mediation, as evidenced by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry revealing oligomeric masses and XPS confirming sp3 C–C bonds. Electron paramagnetic resonance detected transient carbon radicals during fluorination, while DFT calculations identified low-energy pathways for fluorine attack at aromatic carbons, culminating in radical coupling between π-stacked molecules.

Martins et al.13, employed Raman spectroscopy to monitor the pressure-induced transformation of bilayer graphene encapsulated in water, a reactive PTM. The G band frequency obtained with excitation laser energy 2.33 eV and 2.54 eV splits for P ≥ 7.5 GPa. The blueshift of the G band with increasing excitation energy suggests the occurrence of a system in which the sp2 and sp3 phases coexist. Critically, the authors emphasized that water’s hydroxyl groups covalently bonded to carbon atoms, stabilizing the metastable diamane phase.

Earlier, Barboza et al.12 demonstrated the room-temperature diamondization of few-layer graphene, observed as a compression-induced charging inhibition in bilayer and multilayer graphene. Using electric force microscopy (EFM), it was found that the efficiency of charge injection decreased significantly with increased pressure for bilayer and few-layer graphene, indicating a gap opening in these structures. Additionally, the presence of water on the graphene surface was shown to enhance the diamondization process, as evidenced by the reduced EFM response when the samples were subjected to higher humidity conditions.

Tao et al.104, have traced the evolution of the Raman G peak of suspended bilayer graphene in water PTM and found signs of sp2 to sp3 transition between layers. The disappearance of the G peak of bigraphene under pressures higher than 37 GPa, together with the vanishing of the 2D peak after pressure release, may indicate that the bilayer graphene has experienced a transition to metastable sp3 bonding and then a collapse after pressure release. This chemically activated transition contrasted with inert PTMs, where no diamondization occurred, underscoring the indispensability of surface functionalization.

Expanding to thicker systems, Martins et al.31, observed that few-layer graphene (2–5 layers) under aqueous compression formed transparent, sp3-rich films with hardness comparable to bulk diamond. The diamondization pressure was found to be around 6 GPa for bigraphene and between 4 and 7 GPa for five-layer graphene and graphite. A significant aspect of this study was the systematic loading of 2D materials into diamond anvil cells using a novel method, which facilitated high-pressure experiments. The characterization of the material was performed using Raman spectroscopy, which indicated phase transitions through changes in the G and 2D bands, as well as atomic force microscopy (AFM) to observe indentation marks on the substrate, confirming the hardness of the new phase. Subsequent work by Rajaji et al.129, expanded this paradigm by elucidating the critical role of chemical activation with biaxial strain in lowering the transition pressure to 7 GPa for few-layer graphene on compressible SiO2/Si substrates. Their in situ Raman and optical absorption studies revealed that substrate-transmitted strain (via SiO2/Si’s low bulk modulus) reduced C–C in-plane distances, while water ice VII at the graphene interface provided hydroxyl groups to stabilize sp3 bonds—a chemo-mechanical interplay absent in rigid diamond substrates or h-BN-passivated FLG.

Collectively, these experiments underscore water’s pivotal role as both a PTM and chemical agent. By passivating reactive carbon edges and surfaces, hydroxyl groups suppress graphitization, enabling the synthesis of ultrathin diamond films under experimentally accessible conditions. The utilization of water as a PTM appears to be the optimal method for the experimental preparation of ultrathin diamond films. Conversely, the irregular arrangement of passivating atoms and atomic groups on the surface of the formed o-diamane does not allow one to be confident of the stable electronic properties of such materials. It is clear that further detailed theoretical studies are required, similar to those already done for graphene oxide.

AFM-induced diamondization

The prospect of attaining diamond film through the direct compression of graphene layers during indentation, a needle-prod9, appears to be a compelling proposition. It is evident that the absence of chemical interaction with the indenter precludes the establishment of a stable diamond structure (and even hinders the connection of layers in the case of bilayer graphene), as demonstrated in theoretical study130. Nevertheless, experimental findings reported below indicate that this chemical interaction did indeed occur, thereby facilitating the formation of a diamond layer between the indenter and the substrate.

A seminal studies11,32 employed modulated nano-indentation AFM on epitaxial bilayer graphene grown on SiC(0001), achieving reversible transformation into a diamond-like structure at remarkably low pressures (1–10 GPa), see Fig. 7c. Crucially, this process relied on the chemical interaction between graphene and the SiC substrate, which passivated the lower surface, thereby stabilizing the diamane phase upon pressure application. Post-indentation AFM topography revealed no residual deformation, indicative of recovery akin to bulk diamond’s elastic response, underscoring the structural integrity of the synthesized film. Nano-indentation experiments revealed a layer-dependent phase transition: bilayer systems transformed completely, whereas thicker films exhibited partial diamondization due to stacking mismatches. This substrate-mediated chemical activation effectively lowered the energetic barrier for interlayer bonding, enabling nucleation of the sp3 phase without requiring prohibitively high pressures.

A subsequent analysis131 of the AFM data was conducted in order to investigate the correlation between the number of layers in graphene and its mechanical properties. Machine learning was utilized primarily to identify and classify graphene domains based on their layer number in both epitaxial and exfoliated graphene films. Through the analysis of the number of graphene layers and detailed Å-indentation experiments, they demonstrated that the formation of diamane is exclusively found in bilayer case in full accordance with theoretical predictions.

Therefore, the experimental diamondization of graphene via indentation hinges on a delicate balance between applied pressure and surface chemical activation. Substrate effects, reactive PTMs, and controlled passivation (e.g., H or F adsorption) together stabilize the forming diamane phase and allow synthesis at moderate pressure. These advances underscore the centrality of chemo-mechanical synergy in realizing ultrathin diamond films, charting a pragmatic path toward scalable diamane fabrication.