Abstract

Polygenic embryo screening (PES) is used to screen embryos for their genetic likelihood of developing complex conditions and traits. We surveyed 152 U.S. reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) on their views of PES. While most respondents (97%) were at least slightly familiar with PES, general approval of PES was low (12%), with the majority expressing disapproval (46%) or uncertainty (42%). A majority (58%) believed risks outweigh benefits, while only 16% felt benefits outweigh risks. Most clinicians (85–77%) were very or extremely concerned about low accuracy, confusion over results, false expectations, and eugenics. Nonetheless, when asked to vote on whether PES should be allowed, 44% would vote to allow it, 45% would vote to disallow it, and 10% would abstain from voting. REIs showed more support for PES when used to screen for physical and psychiatric health conditions (59–55% approving) rather than behavioral or physical traits (7–6% approving).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is a biotechnology used to test embryos and prevent the implantation of embryos with aneuploidies and monogenic disease-causing alleles1,2. Polygenic embryo screening (PES), also known as PGT-P, is an emerging biotechnology, commercially offered alongside in vitro fertilization (IVF) to screen embryos’ DNA for their future likelihood of developing physical health conditions (e.g., cancer), psychiatric health conditions (e.g., schizophrenia), physical traits (e.g., height), and behavioral traits (e.g., intelligence) using polygenic scores3,4,5,6,7,8. A condition is typically understood as a diagnosable health-related issue, such as cancer or schizophrenia, whereas a trait refers to an observable or latent characteristic like height or cognitive ability. However, the line between the two can often be ambiguous9. Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) are calculated by summing the effects of many genetic variants to estimate an individual’s genetic likelihood for a given condition or trait. Because these genetic variants are fixed from conception, they can be used for genetic screening of embryos, and parents can use these polygenic scores to prioritize and select an embryo that they would like to transfer for implantation. Although studies have shown that computing polygenic scores for embryos is technically possible, the relatively small number of embryos, the scores’ inconsistent performance across different populations and environments, and their low predictive accuracy remain practical limitations4,6,8,10. In our recent qualitative work, we observed that IVF patients and reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists (REIs) in the U.S. hold noticeably different attitudes towards PES, with REIs typically having more reservations about the technology than patients9. REIs are not ready to directly offer PES to patients, and those who are, typically are only willing to do so under certain circumstances9. Qualitative interviews with European and U.S. healthcare professionals suggest that there are concerns about the socio-ethical implications of PES, possibly resulting in stigmatization of phenotypes and increased commercialization of reproduction and health11. Furthermore, interviews of European patients undergoing PGT suggest that they perceived little added value in using PES and were concerned about it increasing anxiety12. However, research findings from U.S. samples suggest that patients view PES for health conditions in a more positive manner9,13,14,15. Similarly, three survey studies focused on public attitudes indicate significant public approval for PES, with two of the studies examining and finding significantly lower approval for screening for traits compared to screening for conditions16,17,18.

Multiple professional societies focused on genetics and reproductive medicine have issued statements declaring that PES is not ready for clinical use19,20,21,22,23,24. In the U.S., there are limited regulations on the use of PES and no regulatory guidance on which genetic conditions or traits may be screened for in embryos. As such, REIs are positioned as gatekeepers of this emerging technology, and their views, in large part, determine access to PES. It is therefore critical to understand REI attitudes, interests, and concerns regarding PES. This survey is designed to better understand U.S. REIs’ views on PES, and it is particularly important given qualitative studies in the U.S. indicating a divide between clinicians’ reluctance to offer PES and patients’ and the public’s relatively higher approval of PES9,13,14,15,16,17,18.

Results

Demographics

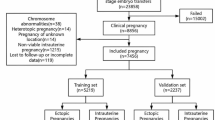

A total of 183 REIs accessed the survey. Of these, 38 did not answer any questions, and 3 participants answered more than two comprehension checks incorrectly and were therefore removed. In total, 152 REIs met the eligibility criteria and answered our survey questions. Of the 152 REIs who took the survey, between 122 and 129 answered each demographic question. The number of years of practice ranged from 1 to 42 years, with a mean of 17.59 years and a standard deviation of 11.52 years. 71 (57.72%) respondents self-identified as female and 52 (42.28%) self-identified as male. See Table 1 for additional demographics.

Clinicians’ familiarity and perceived patient perspectives on PES

Despite PES being an emerging technology, 148 of 152 (97%) REIs responded that they were at least slightly familiar with it. Only 8 respondents (5%) reported being extremely familiar with PES (see Fig. 1). When asked about their experience with patients initiating a discussion about PES, 93% of REIs reported that they had never (74%) or rarely (19%) experienced this, 6% reported that they had sometimes experienced this, and 1% indicated that they had often experienced this. Similarly, REIs reported they had never (53%) or rarely (35%) initiated a discussion about PES with a patient, while 11% reported they had done so sometimes and 1% often. Additionally, 86% of REIs reported that their patients had never (47%) or rarely (39%) requested PES, while 13% reported sometimes and 1% had often done so. Of this sample of REIs, 89% reported having never offered PES to a patient, while 7% reported having rarely done so, 3% sometimes, and 1% often (see Fig. 2). When asked to estimate their patients’ interest in PES and pursuit of PES after genetic counseling, on average clinicians estimated that 30% of their patients would be interested in PES, but 17% of their patients would ultimately pursue PES after undergoing genetic counseling (see Fig. 3). REIs’ estimate of patients pursuing PES was significantly reduced between before (M = 29.9, SD = 22.83) and after genetic counseling (M = 17.00, SD = 18.13); t(142) = 8.86, p < 0.001; cohen’s d = 0.74 [0.55, 0.93].

REIs were asked to “Please estimate what percentage of your patients would be interested in using polygenic embryo screening” (average seen on left). The sample size of respondents was n = 144. REIs were also asked to “Please estimate what percentage of your patients would ultimately pursue polygenic embryo screening after genetic counseling” (average seen on right). The sample size of respondents was n = 143.

General approval of PES

Results in Fig. 4 demonstrate that none of the REIs strongly approved (0%) of PES, 17 (12%) approved, 61 (42%) neither approved nor disapproved, 46 (32%) disapproved, and 20 (14%) strongly disapproved (n = 144). When asked whether they would vote to allow or disallow PES, 64 (44%) reported they would vote to allow it, 65 (45%) to disallow it, and 15 (10%) would not vote (n = 152). Furthermore, 83 (58%) REIs indicated that they felt the risks of PES outweighed its benefits, 23 (16%) indicated that they felt the benefits outweighed the risks, and 38 (26%) indicated that they felt the risks and benefits were equal (see Fig. 4).

There was little variance in REIs’ approval for using PES for specific purposes (i.e., information, preparation, embryo selection, and embryo selection based on family history). However, when asked about using PES to screen specific outcomes, the majority of REIs reported disapproval for embryo selection based on screening for physical traits (83%) and behavioral traits (81%), while close to a third disapproved of embryo selection based on screening for physical (31%) and psychiatric health conditions (35%) (see Fig. 5).

REIs were asked to answer the following prompt: “I approve/disapprove of people using polygenic embryo screening for the following purposes” when used to screen embryos for physical or psychiatric conditions or physical or behavioral traits. Purposes (embryo selection with family history, embryo selection, preparation, information) were presented to participants in the following way: Information: People using PES to know more about their future child. Preparation: People using PES to prepare (resources) for their future child. Embryo Selection: People use PES to select embryos to use with their preferred genetic chances. Embryo Selection given family history: People using PES to select embryos to use with their preferred genetic chances for traits or conditions that run in their family. The sample size of respondents varied from n = 125–127.

Approval of PES purposes: information and selection

The responses were aggregated across outcomes (see Fig. 5) to assess whether there were significant differences in approval for the following purposes (presented in descending mean order with higher means indicating higher approval): preparation (mean [SD], −0.68 [2.42]), embryo selection based on family history (−0.84 [2.38]), information (−0.83 [2.33]), and general embryo selection (−1.02 [2.32]). The Mauchly test of sphericity was significant, so Huynh-Feldt corrections were applied. A repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant differences in approval across purposes (partial η² = 0.01; P = 0.16).

Approval of PES outcomes: traits and conditions

The responses were aggregated across purposes to examine differences in approval for the following outcomes (presented in descending mean order with higher means indicating higher approval): physical health conditions (mean [SD], 1.21 [3.18]), psychiatric health conditions (1.01 [3.23]), physical traits (−2.82 [2.27]), and behavioral traits (−2.83 [2.09]). Since the Mauchly test of sphericity was significant, Huynh-Feldt corrections were applied. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant differences in approval across outcomes (partial η² = 0.63; P < 0.001). Post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections showed significant differences between each of the physical and psychiatric health conditions and each of the behavioral and physical traits (P < 0.001 for each of the four comparisons), but no significant differences were found within conditions (physical vs. psychiatric) or within traits (behavioral vs. physical) (P = 1.00 for both tests).

PES concerns

When asked how concerned, if at all, they were about 14 potential concerns, 83% to 99% of REIs indicated being at least slightly concerned with each. Across all concerns presented, 42% (for reduced diversity) to 85% (for false expectations) reported being very or extremely concerned. As depicted in Fig. 6, the concerns in order of greatest concern to least concern based on mean REI response were: false expectations about the future child, low accuracy of genetic estimates for conditions/traits, promoting eugenic thinking/practices, parents’ confusion over how to interpret test results and use the information, cannot be applied equally to all ethnicities, stigmatization of certain conditions and traits viewed as less desirable, treating embryos like a product by selecting them based on preferred genetic chances for conditions/traits, unequal access to PES due to cost, parents feeling obligated/pressured to use PES, parents shaping their child’s environment based on the embryo’s genetic estimates, discarding (usable) embryos, medical liability, guilt over embryo screening decisions if the child develops a particular condition/trait, and reduced human diversity (see Fig. 6).

REIs were asked to answer on a 5-point Likert scale: “How concerned, if at all, are you with the following 14 potential concerns that have been raised about polygenic embryo screening (PES)?” The 14 concerns are ranked in descending order according to mean concern. Sample size varied from n = 126–128 across concern items. *Nurtured genetics refers to “Parents shaping their child’s environment based on the embryo’s genetic estimates34.

Discussion

The present results suggest that REIs are reluctant to use PES. Such a stance is consistent with prior qualitative findings9, and guidelines issued by professional societies stating that PES is not ready for clinical use19,20,21,22,23,24. Results indicate that most clinicians surveyed are aware of PES, with only 3% of clinicians reporting not being familiar with it at all. However, the level of familiarity remained low among the other clinicians, with only 29% being very to extremely familiar with PES. Our findings suggest there is considerable disapproval (46%) and uncertainty (42%), as well as low approval of PES in general (12%), and the majority believed that the risks of PES outweigh its benefits. However, REIs were roughly split if required to vote against or for allowing PES. These findings suggest that despite low approval and perceived risks of PES, REIs are reluctant to prohibit its use. This reluctance may reflect the complexity of weighing multiple factors, such as professional ethical standards, patient autonomy, and navigating the pressure to adapt to patient requests. Further research into the factors influencing these views could provide deeper insight into how REIs navigate these complex issues.

Results suggest that 7% of REIs reported having sometimes or often had a patient initiate a discussion about PES, and 14% reported a patient sometimes or often requesting PES. In contrast, 12.3% of REIs initiated discussion about PES, and 4% sometimes or often offered PES. These findings suggest that at present, there is relatively low demand for PES. However, as the technology develops commercially, REIs may feel pressured to accommodate patient requests, even when conflicting with their professional medical judgment and professional societies stating that PES is not ready for clinical use19,20,21,22,23,24. Debates around PGT-A for sex selection offer insights into what may unfold, where clinics, despite disagreement among REIs, end up providing sex selection services amidst a lack of clear guidelines and increased patient demand25. Furthermore, a survey of IVF clinics conducted in 2008 found that “nearly half (47%) of the directors who offered PGS agreed with the statement that ‘the push to offer PGD for aneuploidy screening is more about market pressure than medical evidence’”26. Similar commercial pressures could also push providers and clinics to adopt PES to stay competitive in the ART industry, raising questions about whether the lack of consensus and slow development of guidelines can keep pace with these market-driven pressures.

REIs estimated that 30% of their patients may be interested in PES, but that only 17% would pursue PES after undergoing genetic counseling. This finding suggests that REIs believe that patients who undergo genetic counseling may be dissuaded by the technology’s limitations and/or view it as less valuable or desirable than they initially thought. This finding speaks to the importance of informed consent, which respects patients’ autonomy by providing relevant details about PES in an accessible manner to help promote decisions that align with patient values27,28.

The present results also indicate a stark contrast with the U.S. public attitudes of PES16. Findings from our U.S. public survey revealed that 72% approve of PES, 77.5% would vote to allow it, and 67% believe benefits outweigh risks. In contrast, the clinician survey reveals that 12% approve, 44% would vote to allow it, and 16% believe the benefits outweigh risks. Furthermore, while both groups are concerned about the potential for “confusion over how to interpret the test results and use the information,” it appears to be of greater concern for U.S. clinicians (77% very or extremely concerned) than it is for the U.S. public (36% very or extremely concerned). Similarly, only 46% of the public sample reported being very or extremely concerned about “low accuracy” of PES, compared to 81% of clinicians. Such differences likely stem from different levels of understanding PES’s limitations in predictive accuracy and point to a need for developing educational materials that enhance the public and patient statistical literacy.

One point of similarity between clinicians and the public, although of varying degrees, is that both had a minority that reported approving of screening for physical traits (clinician: 7% approving; public: 30% approving) and behavioral traits (clinician: 6% approving; public: 34% approving) for the purpose of embryo selection. When asked about approval for screening health conditions, both clinicians and the public had a majority approving for physical health conditions (clinician: 59% approving; public: 77% approving) and psychiatric health conditions (clinician: 55% approving; public: 72% approving). The small majority of clinicians approving of embryo selection specifically for health conditions may appear at odds with the initial finding that only 12% approved of polygenic embryo screening in general. Such a divergence is suggestive that the general perception of PES evokes concern, while specifically using PES to screen for health conditions is perceived as legitimate (see Barlevy et al. for stakeholder perceptions on screening traits versus conditions29). These findings reflect a nuanced position among clinicians: while there is high overall skepticism toward polygenic embryo screening, there is also selective acceptance in about half of clinicians when the focus is on health outcomes. Furthermore, the fact that 85% and 81% of clinicians reported being very or extremely concerned about false expectations and low accuracy further reflects skepticism about the clinical utility of PES, which corroborates qualitative findings and professional societies statements on PES not being ready for clinical implementation. Finally, ethical and social concerns likely play a role in clinicians’ stances, considering that 77% of clinicians were very or extremely concerned about PES promoting eugenic thinking/practices. Overall, this suggests that opposition is not absolute, but rather conditional, grounded in concerns about validity, ethics, and scope of use.

The present analysis includes responses of REIs who agreed to voluntarily participate in the survey. Despite similar demographic results to other research surveying U.S.-based REIs,30,31 generalizability from results may be limited due to self-selection. The development of this survey followed qualitative research on the perspectives of U.S.-based REIs9. Similarly, qualitative findings have been recently reported for European REIs32. It would be valuable to conduct quantitative analysis of Europe-based REIs to test previous qualitative findings and compare clinician perspectives cross-culturally. Clinician attitudes in other regions are entirely unknown. Additionally, it would be valuable to survey other professional perspectives involved throughout various stages of the PES process, including those of embryologists and genetic counselors.

Overall, the present findings suggest that U.S. REIs are presently reluctant to use PES. Such a stance is consistent with other studies9,33 and the guidelines of professional societies19,20,21,22,23,24, which suggest that PES is not ready for clinical use. These findings highlight the importance of educating clinicians and patients on the potential benefits and limitations of PES. Such education is essential for REIs due to their current limited experience with PES and unique position as gatekeepers of this technology, yet potentially vulnerable to its commercial pressures. Moreover, if REIs offer PES to their patients, it is vital to respect patients’ autonomy by informing them of relevant information in an accessible manner to allow them to make informed decisions that align with their values.

Methods

Participants

The study examined U.S.-based REIs’ views on PES. REIs were recruited from the Society for Endocrinology and Infertility’s member list (n = 731 were emailed), at its annual scientific congress, an REI journal club (prior to discussing the technology), and snowball sampling via REI contacts. Recruitment began in October 2023 and concluded in July 2024.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants indicated informed consent to participate by selecting the “I agree to participate” option at the start of the survey. Participating REIs had the choice to skip questions on the survey. All study participants were offered a $10 gift card.

Survey design

The survey was programmed using the Qualtrics software and distributed to REIs online. The survey was pre-registered: https://aspredicted.org/NCF_JXG. First, each survey participant was asked if they are currently practicing as an REI in the United States. If participants were not a practicing REI in the U.S., they were routed out of the survey. Subsequently, participants were asked to indicate their level of familiarity with PES. Participants were then given a brief introduction to PES technology, which focused on its purpose and uses, and described IVF, monogenic testing, and polygenic testing16. In parallel, they were asked to answer seven comprehension checks regarding PES capabilities and limitations. Those who answered more than two comprehension checks incorrectly did not meet the study participant eligibility criteria, so their data were excluded from this study. After the comprehension checks, REIs reported their experience with patients using PES and how much they estimated U.S. IVF patients, as well as their specific patient population, may be interested in using PES. To explore REIs' subjective perception of patient demand for PES, and how they believe genetic counseling may influence that demand, they were asked what percentage of their patients they estimated would be interested in using PES both before and after receiving genetic counseling.

Thereafter, we asked participants about their general approval of PES, their views on the risk/benefit ratio of PES, and their hypothetical vote on whether or not PES should be allowed. Risks and benefits were undefined in the survey in order to allow REIs to make their own assessments based on their clinical judgment. Additional questions gauging medical decision-making were asked, but extend beyond the scope of this paper. REIs were then presented with a 4 × 4 matrix (used in Furrer et al., 2024 for public attitudes16) and indicated whether they approved of, disapproved of, or did not have an opinion on using PES for the following purposes: information, preparation, embryo selection, and embryo selection based on family history (i.e., “People using PES to select embryos to use with their preferred genetic chances for traits or conditions that run in their family”). For each purpose, participants rated their approval for 4 screened outcomes: physical health conditions, psychiatric health conditions, physical traits, and behavioral traits. Subsequently, participants assessed their level of concern regarding 14 distinct concerns related to PES that were identified in interviews with U.S. REIs9. Finally, standard demographic information was collected.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Baylor College of Medicine (BCM; protocol H-49262). It complies with the ethical standards for research involving human participants as established by BCM and adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The IRB of Harvard Medical School ceded review to the BCM IRB. All participants were presented with information about the study prior to beginning the survey. Informed consent to participate was indicated by clicking the ‘I agree to participate’ option or by proceeding to complete the survey after viewing the information in accordance with a waiver of documentation of written consent from the BCM IRB.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics using frequency counts in percentages were provided for all questions described in the methods. To analyze the 4×4 approval matrix, responses were totaled across either outcomes or purposes to perform two exploratory repeated-measures ANOVAs. Approval responses were numerically coded as 1 (approve), -1 (disapprove), and 0 (no opinion). The Mauchly test of sphericity was conducted, and Huynh-Feldt corrections were applied where necessary. Post hoc analyses were also performed using Bonferroni corrections to adjust for multiple comparisons. We also conducted dependent sample t-tests to examine whether REIs’ estimate of patient approval varied depending on whether or not patients underwent genetic counseling. Statistical analyses were performed using JASP (version 0.19.1) and SPSS (version 29.0.2.0).

Survey materials

Survey materials for the full study are available at: https://researchbox.org/2101.

Data availability

The full dataset is currently part of ongoing research efforts. We will make this data publicly available upon completion of the full set of studies. In the meantime, data will be shared upon reasonable request for the purpose of verification or collaboration.

References

ESHRE PGT Consortium Steering Committee et al. ESHRE PGT Consortium good practice recommendations for the organisation of PGT. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, hoaa021 (2020).

Cimadomo, D. et al. The dawn of the future: 30 years from the first biopsy of a human embryo. The detailed history of an ongoing revolution. Hum. Reprod. Update 26, 453–473 (2020).

Capalbo, A. et al. Screening embryos for polygenic disease risk: a review of epidemiological, clinical, and ethical considerations. Hum. Reprod. Update 30, 529–557 (2024).

Lencz, T. et al. Utility of polygenic embryo screening for disease depends on the selection strategy. eLife 10, e64716 (2021).

Devlin, H., Burgis, T., Pegg, D. & Wilson, J. US startup charging couples to ‘screen embryos for IQ’. The Guardian (2024).

Turley, P. et al. Problems with using polygenic scores to select embryos. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 78–86 (2021).

Lázaro-Muñoz, G., Pereira, S., Carmi, S. & Lencz, T. Screening embryos for polygenic conditions and traits: ethical considerations for an emerging technology. Genet. Med. 23, 432–434 (2021).

Karavani, E. et al. Screening human embryos for polygenic traits has limited utility. Cell 179, 1424–1435.e8 (2019).

Barlevy, D. et al. Patient interest in and clinician reservations on polygenic embryo screening: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 41, 1221–1231 (2024).

Martin, A. R. et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 51, 584–591 (2019).

Siermann, M. et al. “Are we not going too far?“: Socio-ethical considerations of preimplantation genetic testing using polygenic risk scores according to healthcare professionals. Soc. Sci. Med. 343, 116599 (2024).

Siermann, M. et al. Perspectives of preimplantation genetic testing patients in Belgium on the ethics of polygenic embryo screening. Reprod. Biomed. Online 49, 104294 (2024).

Neuhausser, W. M. et al. Acceptance of genetic editing and of whole genome sequencing of human embryos by patients with infertility before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod. Biomed. Online 47, 157–163 (2023).

Eccles, J., Marin, D., Duffy, L., Chen, S. H. & Treff, N. R. Rate of patients electing for polygenic risk scores in preimplantation genetic testing. Fertil. Steril. 116, e267–e268 (2021).

Katz, M. et al. Patient perspectives after receiving simulated preconception polygenic risk scores (PRS) for family planning. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 42, 997–1013 (2025).

Furrer, R. A. et al. Public attitudes, interests, and concerns regarding polygenic embryo screening. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2410832 (2024).

Meyer, M. N., Tan, T., Benjamin, D. J., Laibson, D. & Turley, P. Public views on polygenic screening of embryos. Science 379, 541–543 (2023).

Zhang, S., Johnson, R. A., Novembre, J., Freeland, E. & Conley, D. Public attitudes toward genetic risk scoring in medicine and beyond. Soc. Sci. Med. 274, 113796 (2021).

Forzano, F. et al. The use of polygenic risk scores in pre-implantation genetic testing: an unproven, unethical practice. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 30, 493–495 (2022).

Wand, H. et al. Clinical genetic counseling and translation considerations for polygenic scores in personalized risk assessments: A Practice Resource from the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 32, 558–575 (2023).

Abu-El-Haija, A. et al. The clinical application of polygenic risk scores: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 25, 100803 (2023).

Ethics Committee of the AmericanSociety for Reproductive Medicine. Use of preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic adult-onset conditions: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 122, 607–611 (2024)

Grebe, T. A. et al. Clinical utility of polygenic risk scores for embryo selection: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 26, 101052 (2024).

Klitzman, R. Struggles in defining and addressing requests for “Family Balancing”: Ethical issues faced by providers and patients. J. Law. Med. Ethics 44, 616–629 (2016).

Baruch, S., Kaufman, D. J. & Hudson, K. L. Preimplantation genetic screening: a survey of in vitro fertilization clinics. Genet. Med. 10, 685–690 (2008).

Moulton, B. & King, J. S. Aligning ethics with medical decision-making: the quest for informed patient choice. J. Law. Med. Ethics 38, 85–97 (2010).

Paterick, T. J., Carson, G. V., Allen, M. C. & Paterick, T. E. Medical informed consent: general considerations for physicians. Mayo Clin. Proc. 83, 313–319 (2008).

Barlevy, D. et al. Eugenics and polygenic embryo screening: Public, clinician, and patient perceptions of conditions versus traits. Genet. Med. 101507 (2025)

Barnhart, K. T. et al. Practice patterns, satisfaction, and demographics of reproductive endocrinologists: results of the 2014 Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Workforce Survey. Fertil. Steril. 105, 1281–1286 (2016).

Stadtmauer, L., Sadek, S., Richter, K. S., Amato, P. & Hurst, B. S. Changing gender gap and practice patterns in reproductive endocrinology and infertility subspecialists in the United States: a Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility report. Fertil. Steril. 117, 421–430 (2022).

Siermann, M. et al. Limitations, concerns and potential: attitudes of healthcare professionals toward preimplantation genetic testing using polygenic risk scores. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 31, 1133–1138 (2023).

Shah, S., Cantor, R. M., Quinn, M., Shamshoni, J. & Palmer, C. G. S. Preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disorders: Viewpoints of reproductive genetic counselors and reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialists in the United States. J. Genet. Couns. 34, e70072 (2025).

Furrer, R., Carmi, S., Lencz, T. & Lázaro-Muñoz, G. Nurtured genetics: prenatal testing and the anchoring of genetic expectancies. Am. J. Bioeth. 23, 42–44 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by the United States National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant #NIH R01MH011711).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.F., D.B., G.L.M., S.P., S.C., T.L.: Conceptualization: R.A.F., D.B., G.L.M., S.P., S.C., T.L.: Methodology, Survey Design: R.A.F., A.G.: Formal Analysis: R.A.F., A.G., D.B.: Writing – Original Draft: All authors: Writing – Review & Editing: G.L.M., S.P.: Co-supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Funding Acquisition: T.L., S.C., G.L.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Shai Carmi receives personal fees from MyHeritage for work unrelated to this paper. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furrer, R.A., Barlevy, D., Gandhi, A. et al. Survey of U.S. reproductive medicine clinicians’ attitudes on polygenic embryo screening. npj Genom. Med. 10, 79 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00530-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-025-00530-3