Abstract

We introduce a novel stretchable photodetector with enhanced multi-light source detection, capable of discriminating light sources using artificial intelligence (AI). These features highlight the application potential of deep learning enhanced photodetectors in applications that require accurate for visual light communication (VLC). Experimental results showcased its excellent potential in real-world traffic system. This photodetector, fabricated using a composite structure of silver nanowires (AgNWs)/zinc sulfide (ZnS)-polyurethane acrylate (PUA)/AgNWs, maintained stable performance under 25% tensile strain and 2 mm bending radius. It shows high sensitivity at both 448 and 505 nm wavelengths, detecting light sources under mechanical deformations, different wavelengths and frequencies. By integrating a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) model, we classified the light source power level with 96.52% accuracy even the light of two wavelengths is mixed. The model’s performance remains consistent across flat, bent, and stretched states, setting a precedent for flexible electronics combined with AI in dynamic environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flexible and stretchable photodetectors are indispensable for the advancement of optoelectronic devices, encompassing foldable displays, environmental monitoring systems, and bio-imaging applications1,2,3,4,5,6. Extensive research efforts have been dedicated to the development of these photodetectors through the utilization of diverse materials, structures, and mechanisms7,8,9. Typically, such research endeavors concentrate on optimizing the wavelength range and light intensity to maximize the responsivity of photodetectors, thereby evaluating their characteristics under these optimal conditions10,11,12. However, in practical applications, photodetectors frequently encounter light sources with a broad spectrum of wavelengths. While general wavelength detection may suffice for certain applications, others, such as object recognition in autonomous vehicles, necessitate the precise identification of specific wavelengths for accurate object detection. For example, to respond to information provided by traffic lights, you must accurately distinguish the displayed colors to make appropriate decisions (stop or drive). In addition, confusion caused by other objects with similar wavelengths to the colors of traffic lights can lead to accidents, so you should be able to accurately respond to specific wavelengths provided by traffic lights. Consequently, for flexible photodetectors to be effectively integrated into next-generation systems, they must possess the capability to accurately distinguish the constituent wavelengths of incident light.

However, as previously elucidated, light sources inherently comprise a mixture of various wavelengths. When these wavelengths are combined and irradiated onto a photodetector, a single element within the device is constrained to detect and process a composite light signal. This presents a formidable challenge, as it necessitates the capability to discern individual wavelength components from a combined signal. Consequently, while it is paramount to enhance the intrinsic properties of the photodetector, it is equally critical to develop an integrated system that incorporates an additional wavelength classification mechanism. In recent advancements, the application of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, to photodetectors has emerged as a promising solution to this challenge13,14,15,16,17. Deep learning models, trained on extensive datasets of signals detected by the devices, possess the ability to recognize and distinguish complex signal patterns under various conditions. These models employ sophisticated algorithms to process vast quantities of data, enabling the identification of subtle differences in wavelength and intensity that are imperceptible to traditional detection methods18,19,20. For a deep learning model to operate effectively, it is imperative that the photodetector outputs stable and consistent signals over an extended period. This stability is crucial because the model’s ability to recognize patterns and make accurate classifications is heavily dependent on the quality and reliability of the input data. In the case of stretchable photodetectors, which are susceptible to deformation due to external stress, achieving uniform signal output under mechanical strain is particularly challenging. High-quality data collection can only be ensured if the photodetector maintains its performance and signal consistency even when subjected to such deformations21,22. For example, if the photodetector is bent or stretched, its responsiveness may change, leading to the signal input into the deep learning model deviating from the learned pattern and misclassification. This is because light is incident with the same wavelength and intensity, but the area or electrical characteristics of light detection may vary depending on the deformation state of the photodetector. Therefore, the development of photodetectors capable of withstanding mechanical stress while delivering consistent and accurate signals is critical for the successful integration of AI-driven wavelength classification systems.

To date, various photoactive and substrate materials have been employed to evaluate the properties of photodetectors, with the objective of maintaining their mechanical stretchability and performance under deformation23,24,25. Semiconductor materials are typically utilized as photoactive components due to their high photoconductive properties. However, their inherent brittleness and rigidity present significant challenges in achieving diverse mechanical deformations26. One proposed solution to this issue involves the fabrication of devices based on a capacitive mechanism by incorporating semiconductor particles within a polymer matrix27,28,29. This approach leverages the theory of composite materials, wherein the mechanical properties of the polymer (elasticity and flexibility) are combined with the electrical properties of the semiconductor particles (photoactivity). By utilizing a capacitive sensing mechanism, the device operates based on changes in capacitance induced by incident light. When light irradiates the photodetector, electron-hole pairs are generated within the semiconductor particles, leading to a change in the dielectric properties of the composite. This alteration in dielectric constant affects the overall capacitance of the device, which can be measured and correlated to the light intensity. This principle is grounded in Maxwell’s equations, which describe the behavior of electric fields in materials30. The fabrication of a composite film involves dispersing semiconductor particles in a transparent polymer matrix. The polymer provides the necessary flexibility and stretchability, while the semiconductor particles retain their photoreactive properties.

In this study, we elucidate the characteristics of light intensity and wavelength detection utilizing a stretchable photodetector integrated with deep learning algorithms. Polyurethane acrylate (PUA) polymer, esteemed for its exceptional elasticity and light transmittance, was employed as a photosensitivity agent through the dispersion of copper-doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu), a semiconductor material. PUA with high dielectric constant compared to widely used stretchable polymers induces significant capacitance, making it particularly suitable for flexible capacitive photodetector applications. A standalone ZnS:Cu-PUA film was meticulously fabricated, with silver nanowire (AgNW) electrodes deposited on both surfaces to form a capacitor. These AgNW electrodes efficiently transmitted irradiated light to the ZnS:Cu composite layer. The photodetector, structured with the configuration AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs, exhibited its wavelength discrimination capabilities by comprehensively evaluating its sensitivity to light at wavelengths of 448 nm and 505 nm. Under optimized conditions, the photodetector demonstrated a linear response to variations in capacitance corresponding to light intensity, achieving a maximum photosensitivity rate of 120%. The utilization of stretchable PUA polymer facilitated mechanical deformation without substantial degradation in photosensitivity, as the AgNW electrodes maintained stable electrical characteristics throughout the stretching process. The fabricated photodetector effectively distinguishes between different wavelengths and light intensities, maintaining consistent capacitance change patterns even under mechanical deformation. This capability is ideal for high-quality data collection suitable for deep learning applications. To demonstrate this, a 1-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D CNN) model was employed. The photodetector, subjected to 20% strain and tested with two types of light sources under five conditions, produced data consistent with initial levels, even under mechanical deformation. The 1D CNN model achieved over 94% accuracy in classifying light sources and intensities under most conditions. In addition, the photodetector integrated with the same deep learning model successfully recognized the flickering frequency of the emitted light and even possessed the signal detection characteristics for communication. The developed photodetector’s signal classification function will be applied to smart road traffic systems or light-based information transmission and reception environments to play a groundbreaking role in increasing stability and accuracy.

Results

Fabrication of polymer body based stretchable photodetector

Figure 1a illustrates a schematic representation of the manufacturing process for the stretchable photodetector. Initially, the glass substrate was cleaned to ensure complete removal of contaminants. Subsequently, AgNWs were deposited onto the cleansed glass substrate to serve as the lower electrode of the device. Fluorescent ZnS:Cu semiconductor particles were uniformly dispersed within the synthesized PUA solution, which was subsequently coated onto the AgNWs layer. The characterization details of synthesized PUA are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. The ZnS:Cu-PUA composite was then underwent a soft-baking heat treatment to achieve the requisite surface hardness. To fabricate the upper electrode of the photodetector, an AgNW layer was deposited onto a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) temporary substrate. This electrode layer was then carefully transferred from the hydrophobic PDMS temporary substrate to the adhesive surface of the ZnS:Cu-PUA composite film. Following the formation of both electrode layers, the samples were fully cured through ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and subsequently exfoliated delicately from the glass substrate. During this process, the AgNWs layer initially deposited on the glass substrate was completely transferred to the surface of the ZnS:Cu-PUA film. The further details of fabrication process and conditions are described in the Experimental section. Figure 1b, c presents field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) images depicting the surfaces of the upper and lower AgNWs electrodes, respectively, on the ZnS:Cu-PUA film. These images confirm the successful formation of both electrode layers on the ZnS:Cu-PUA film surface via the transfer process. The presence of faint spherical particles in the center of the images substantiates the incorporation of ZnS:Cu particles within the PUA matrix.

a Schematic illustration of the fabrication process for the stretchable photodetector. b FESEM image depicting the top surface of the AgNWs electrode. c FESEM image exhibiting the bottom AgNWs electrode. d High-resolution FESEM image providing a detailed view of the AgNWs network structure on the surface of the ZnS:Cu-PUA film. e Cross-sectional FESEM image of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs composite film.

a Digital images of the fabricated ZnS:Cu-PUA film including bending, stretching, and twisting. b Stress-strain curve of the ZnS:Cu-PUA composite. c Transmittance spectra of the top and bottom AgNWs electrodes. d Resistance variation of the top AgNWs electrode during mechanical deformation tests conducted over 1000 cycles, subjected to stretching strains of 5%, 10%, and 20%. e Resistance variation of the bottom AgNWs electrode under stretching strains of 5%, 10%, and 20%. f Resistance variation of the top AgNWs electrode during mechanical deformation tests conducted over 1000 cycles, subjected to outward bending with curvature radii of 10 mm, 5 mm, and 2 mm. g Resistance variation of the bottom AgNWs electrode during mechanical deformation tests conducted over 1000 cycles, subjected to outward bending with curvature radii of 10 mm, 5 mm, and 2 mm.

Figure 1d presents a high-magnification image, confirming that the AgNW electrode layer was thoroughly impregnated onto the film surface. This impregnation occurred because the PUA was in contact with the electrode layer while in a liquid state or only partially cured, followed by complete curing through UV irradiation. In contrast to merely coating the electrode onto a pre-cured film, this approach results in a more robust bonding between the electrode and the substrate, significantly diminishing the likelihood of the electrode layer detaching, even under mechanical deformation. Fig. 1e depicts a cross-sectional image of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs composite, revealing that the total thickness of the composite film is 80 μm, with ZnS:Cu particles uniformly dispersed throughout the matrix. Notably, even with a ZnS:Cu content of 70 wt%, the phosphor particles do not protrude from the film; rather, they remain well-embedded within the matrix. This ensures that the AgNW electrode layers can be transferred seamlessly, facilitated by interfacial interactions solely with the exposed PUA surface. An image illustrating the surface roughness of the silver nanowire electrode is provided in Supplementary Fig. 3. The root-mean-square roughness (RRMS) values of the upper and lower AgNW-based electrodes were exceptionally flat, measuring 4.245 nm and 4.689 nm, respectively. This notable flatness is attributed to the electrode layer being transferred from flat substrates, specifically glass and PDMS

Evaluation of mechanical characteristics of stretchable photodetector

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive evaluation of the mechanical and electrical stability of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs structure, assessing its suitability for application as a photodetector. Owing to the exceptional elasticity of the PUA polymer, the fabricated photodetector demonstrated the capability to endure various mechanical deformations, including bending, twisting, and stretching, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. This flexibility indicates the potential for the device to be conformally mounted on objects or equipment with complex geometries and multi-bending characteristics. The composites, containing 70 wt% ZnS:Cu particles in the synthesized PUA, were prepared with a uniform thickness of 80 μm, and their strain-stress curves are depicted in Fig. 2b. The composite film exhibited a tensile strength approaching 40 MPa, which is approximately 1.3 times greater than that of the bare PUA film, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 2a. This enhancement in tensile strength can be attributed to the distribution hardening effect of the ZnS:Cu particles within the polymer matrix, which align along the direction of applied stress31. Additionally, the composite film withstood tensile strains exceeding 200%, indicative of the superior elasticity imparted by the PUA substrate. Although the tensile strain experienced a slight reduction due to the incorporation of ZnS:Cu particles, likely attributable to fracture induction at the particle-polymer interface caused by the high concentration of micro-sized fillers, a tensile strain exceeding 200% still guarantees significant elasticity. Thus, the composite film exhibits mechanical properties that are highly suitable for application in stretchable electronic devices. Figure 2c presents the transmittance spectrum as a function of wavelength, evaluating the optical properties of the top and bottom electrodes. Given that the device features a sandwich structure with a photosensitive film interposed between two electrode layers, the transmittance of the electrodes is crucial for ensuring that light irradiated from the exterior can penetrate the device with minimal loss. As evidenced by the transmittance graphs, the top AgNWs electrode, formed on the PUA layer via the transfer method, and the bottom AgNWs electrode, formed via the embedding method, exhibited transmittance values of 94.7% and 94.8%, respectively, at a wavelength of 550 nm. Considering that the transmittance of bare PUA was previously measured at 97.1% (Supplementary Fig. 2b), it is evident that the AgNWs electrodes induced a transmittance reduction of less than approximately 3%.

While exhibiting a high level of transmittance, the sheet resistance of both electrodes was low, measured at 16.3 ohm/sq. This is attributable to the network structure formed by the AgNWs, which possess a high aspect ratio, allowing for high transmittance while maintaining satisfactory electrical characteristics even at a low density. Furthermore, tests were conducted to evaluate the suitability of the AgNWs electrode for application in stretchable devices. Repeated stretching and bending tests were performed up to 1000 cycles, with variable resistance recorded; the results are depicted in Fig. 2d–g. Stretching and bending tests of the top and bottom electrodes were conducted separately. To prevent the peeling of the electrode layer, an additional PUA-based encapsulation layer was formed prior to conducting the tests. Both electrodes exhibited an increasing trend in resistance as the tests progressed. This phenomenon was exacerbated under harsher test conditions, such as increased applied stretching strain or decreased radius of curvature. However, during the bending test, a low resistance change rate of less than 1% was observed under all conditions. In the stretching test, a relatively low change rate of 40% was recorded at a 30% strain. Supplementary Fig. 4 elucidates the effect of enhancing the stability of the electrode through the encapsulation strategy, demonstrated by the results of the stretching and bending tests on an electrode without an encapsulation layer. The unencapsulated electrode exhibited a resistance change rate of up to 400% at 20% strain after 1000 repeated stretching cycles. In the bending test, a resistance change rate exceeding 1% was observed, signifying a significantly worsened outcome compared to the encapsulated sample. Consequently, it was confirmed that the stability of the electrical properties under repeated mechanical deformation was effectively secured by forming the encapsulation layer using PUA. These results were fundamentally due to the excellent elasticity and mechanical rigidity of PUA, and since the film recovers quickly even after repeated deformation, no phenomena such as peeling of phosphor particles were found.

Optical and bandgap comparison of ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu-Cl materials

In order for a stretchable photodetector to be utilized in real-world environments, it must possess the capability to detect multiple wavelength regions. To fabricate a device capable of extending the detectable wavelength range, two types of ZnS:Cu phosphor particles were prepared to explore this potential. Prior to device fabrication, the characteristics of both Cu and Cl-doped ZnS (ZnS:Cu,Cl) particles, as well as ZnS:Cu particles, were thoroughly analyzed. The crystal structure and phase of the phosphors used were examined by XRD, and the results are presented in Fig. 3a, e. Both phosphors exhibited primary diffraction peaks corresponding to the (111), (220), and (311) planes of the cubic zinc-blende phase of ZnS. The positions of these diffraction peaks are critical for phase identification and analysis, as they provide insights into the crystallographic structure of the material. The Bragg’s Law, \(n\lambda =2d\sin \theta\), where n is the order of reflection, λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray, d is the interplanar spacing, and θ is the angle of incidence, governs the diffraction process. For ZnS:Cu, the diffraction peaks appeared at 2θ = 28.65°, 47.39°, and 56.23°, respectively. These peaks correspond to the interplanar spacings characteristic of the cubic zinc-blende phase. In the case of ZnS:Cu,Cl, the main diffraction peaks were observed at 2θ = 28.46°, 47.39°, and 56.40°. The slight shifts in peak positions can be attributed to the incorporation of Cl ions, which slightly alter the lattice parameters due to differences in ionic radii and bonding characteristics. These diffraction peaks are in agreement with the data reported in the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) Card No. 80-002032,33. The agreement with JCPDS standards confirms the phase purity and crystallinity of the synthesized phosphors. This analysis confirms that the crystal structures of the prepared phosphors are consistent with the expected cubic zinc-blende phase, validating their suitability for application in stretchable photodetectors with expanded wavelength detection capabilities.

Comprehensive characterization of two types of phosphor powder (ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl) (a, e) XRD patterns. b, f Color coordinates evaluated from the measured transmission spectra, plotted on the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram. c, g Absorbance spectra peak ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu-Cl phosphors, respectively. d, h Tauc plot graphs of the optical band gap energy, thus determining the band gap energies of ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl to be 2.12 eV and 2.56 eV, respectively.

Figure 3b, f depicts the color spaces (x,y) obtained from the spectral curve of the measured transmittance, which allow for the estimation of the purity of the transmissive color of the structural color filter. The color spaces for ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl phosphors were found at the coordinates (0.366, 0.449) and (0.347, 0.409), respectively. These coordinates are based on the CIE 1931 color space, a colorimetric system widely used to represent colors numerically. The position of these coordinates indicates the dominant wavelength and purity of the color perceived by the human eye. The coordinates for ZnS:Cu are closer to the green region, whereas those for ZnS:Cu,Cl are relatively biased towards the blue region. This distinction highlights the specific wavelengths of light to which each phosphor is more sensitive. The green-shifted coordinates of ZnS:Cu suggest it is more efficient in transmitting green light, while the blue-shifted coordinates of ZnS:Cu,Cl indicate a higher sensitivity to blue light. Figure 3c, g displays the absorbance spectra of the phosphor powders. The absorbance peaks for ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl were observed at 510 nm and 467 nm, respectively. These peaks correspond to the wavelengths at which each phosphor exhibits maximum absorption, indicating the wavelengths of light to which the phosphors are most reactive. The absorbance spectra provide critical information about the electronic transitions within the material, which are associated with the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands. The band gap energy (Eg) of each phosphor can be estimated using the Tauc plot method, which involves plotting (αhν)2 against the photon energy hν, where α is the absorption coefficient, ℎ is Planck’s constant, and ν is the frequency of the incident light. The linear portion of the plot is extrapolated to the x-axis, and the intercept gives the band gap energy. This method is commonly employed for direct band gap semiconductors. Figure 3d, h illustrates the Tauc plots for ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl, respectively. By applying the Tauc relation34,35:

where A is a constant, the band gap values can be derived. These band gap energies are indicative of the electronic properties of the materials and play a crucial role in determining their optical behavior. The band gap energies of ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl, as determined by the Tauc relationship, were 2.12 eV and 2.56 eV, respectively. The distinct band gap energies indicate that ZnS:Cu,Cl has a wider band gap compared to ZnS:Cu, suggesting it is more responsive to higher energy (shorter wavelength) photons. Supplementary Fig. 5 presents the shape images and particle size distribution of the phosphor particles. Both types of phosphors, ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl, exhibited similar morphologies, indicating that the synthesis processes yielded particles with consistent shapes. The average particle sizes were also comparable, measured at 24.1 μm for ZnS:Cu and 24.4 μm for ZnS:Cu,Cl. The negligible difference in particle size distribution implies that the physical dimensions and shapes of the particles do not significantly influence the performance variations observed in the photodetectors.

Photoswitching characteristics of capacitive photodetectors

Before verifying the photo-switching characteristics of the fabricated stretchable AgNWs/phosphor-PUA/AgNWs composite, a comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the performance of photodetectors incorporating ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Cu,Cl phosphors. The ultimate goal of the developed photodetector is to be integrated into a system capable of detecting and differentiating changes in capacitance in response to varying light sources and intensities. To explore this potential, we conducted a series of evaluations. The photodetectors were fabricated with varying phosphor contents of 40, 50, 60, and 70 wt%. Phosphor concentrations exceeding 70 wt% were excluded from performance evaluation due to the observed heterogeneous particle distribution within the composite, attributed to particle aggregation. This aggregation leads to non-uniform dispersion and adversely affects the overall performance of the photodetector. The sensitivity characteristics of the photodetectors were evaluated under illumination with two different light sources, characterized by wavelengths of 448 nm and 505 nm, and power densities of 53.5 mW/cm2 and 137.1 mW/cm2, respectively. In addition, in order to optimize the sample fabrication process that can derive the maximum photoresponse characteristics, the tendency of capacitance change according to the thickness of the composite was investigated (Supplementary Fig. 7). Since the PUA-ZnS:Cu composite was formed through spin coating, the thickness was adjusted by varying the coating speed. A cross-sectional image of the optical microscope collected to measure the composite thickness for each coating condition is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7a. The thickness of the composite was increased based on the minimum thickness of 80 μm, which does not protrude to the outside even when ZnS:Cu particles are loaded up to 70 wt% inside the composite. As the thickness increased, the rate of change of the capacitance gradually decreased because the thickness and capacitance of the dielectric layer were inversely proportional to each other (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Based on these findings, the device manufacturing conditions representing photosensitivity of up to 85% were optimized.

Overall, the light sensitivity of the photodetectors increased with the phosphor content; however, a significant difference in sensitivity to light of the same wavelength was observed depending on the type of phosphor utilized. Figure 4a, b illustrates that the photodetector incorporating ZnS:Cu phosphor exhibited capacitance change rates of 129.3% and 65.7% when exposed to light with wavelengths of 448 nm and 505 nm, respectively. In contrast, the photodetector embedded with ZnS:Cu,Cl phosphor demonstrated capacitance change rates of 84.75% and 34.35% under the same conditions. Notably, the photodetector embedded with 40 wt% ZnS:Cu,Cl phosphor failed to detect light altogether, as depicted in Fig. 4c, d. These results substantiate that ZnS:Cu phosphor exhibits higher sensitivity to light compared to phosphor doped with additional Cl. Semiconductor materials are excited by photons with energies exceeding their bandgap energy, resulting in electron-hole pair generation. The bandgap energies of the phosphors, as estimated in Fig. 2d, h, align with the observed photosensitivity. ZnS:Cu, with a narrower bandgap, responds more efficiently to lower energy photons compared to ZnS:Cu,Cl, which has a wider bandgap and is more responsive to higher energy photons. In addition, the photodetection ability was also evaluated with samples fabricated using the orange phosphor ZnS:Cu-Cl-Mn. The basic characteristics of this phosphor are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, and the XRD spectrum, the peaks corresponding to (111), (220), and (311), like the other two species, were all identified. The absorption peak of ZnS:Cu-Cl-Mn-based phosphor appeared at 740 nm, and the bandgap energy calculated by Eq. (1) was 1.60 eV. The photodetector applying it showed a capacitance change rate of up to 28% in light with a wavelength of 505 nm (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, it was not at all sensitive to light with a wavelength of 448 nm because it is a category outside the wavelength range that ZnS:Cu-Cl-Mn-based phosphor can respond to. Putting these results together, we conclude that it is appropriate to make a photodetector that can react sensitively to both light sources with a 70 wt% ZnS:Cu phosphor. Therefore, we have evaluated in depth the characteristics of the photodetector that introduces ZnS:Cu, which can be used as a device with multi-light source detection capabilities. Therefore, the characteristics of the photodetector introduced with ZnS:Cu, which can be used as a device with multiple light source sensing capabilities, were evaluated in depth. The data indicate that the photodetector’s light sensitivity improves with increasing phosphor content, yet the type of phosphor significantly influences sensitivity at specific wavelengths. The enhanced sensitivity of ZnS:Cu phosphor is attributed to its optimal electronic structure, which facilitates efficient charge carrier generation and transport under light irradiation. Based on these findings, it was concluded that a photodetector designed to respond sensitively to both 448 nm and 505 nm light sources is optimally fabricated using 70 wt% ZnS:Cu phosphor. Consequently, an in-depth evaluation of the photodetector’s characteristics was conducted, focusing on its potential application as a device with multiple light source sensing capabilities.

a, b Capacitance variation of the photodetector with ZnS:Cu phosphor: a when illuminated with light of 448 nm wavelength and (b) under illumination with light of 505 nm wavelength. c, d Capacitance variation of the photodetector with ZnS:Cu,Cl phosphor: c when illuminated with light of 448 nm wavelength and (d) under illumination with light of 505 nm wavelength. e Dynamic capacitance trends of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector in response to varying light intensities. f Capacitance values recorded as the light source is moved away from the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector. g Digital images depicting the experimental setup used to perform the measurements. h The photoresponse time of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector. i Capacitance change of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector in a bent state, with curvature radii of 10 mm, 5 mm, and 2 mm. j Capacitance change of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector in a stretched state, with stretching strains of 5%, 20%, and 30%. k Real-time recording of the capacitance values as the applied stretching strain on the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector increases. l Real-time recording of the resistance values corresponding to the increasing stretching strain applied to the photodetector.

Figure 4e presents the evaluation of the sensing characteristics of the photodetector based on the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs structure when exposed to varying amounts of light. The data indicate that as the optical power increased, the rate of change in capacitance output by the detector also increased. This observation demonstrates that the fabricated photodetector is capable of responding to changes in light intensity. This relationship between optical power and capacitance change can be explained by the photoconductive effect, wherein increased light intensity generates a greater number of electron-hole pairs in the ZnS:Cu phosphor, thus enhancing the device’s capacitance. However, it is important to note that even when light of the same wavelength and intensity is irradiated onto the device, the sensitivity can vary depending on the distance from the light source. To analyze this effect, the capacitance change was recorded while incrementally increasing the distance between the light source and the device from 100 mm to 120 mm, as illustrated in Fig. 4f. This experiment was conducted by fixing the light source to a mobile motor, programmed to move away from the photodetector at a constant speed of 100 mm/min. The results demonstrated a decreasing trend in the overall capacitance change rate as the distance increased, which can be attributed to the inverse square law of light intensity, indicating that light intensity diminishes with the square of the distance from the source. A digital image illustrating the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 4g. This setup is crucial for understanding the practical implications of photodetector deployment in real-world applications, where the distance between the light source and the detector may vary.

Figure 4h details the photoreaction time of the capacitive photodetector, with a rise time and delay time measured at 102 ms and 498 ms, respectively. The rise time corresponds to the time taken for the photodetector’s output to increase from 10% to 90% of its final value upon light exposure, while the delay time represents the time taken for the output to decrease from 90% to 10% of its initial value after the light is turned off. These response times are influenced by the material properties and the internal mechanisms of the photodetector. Typically, stretchable photodetectors are based on elastic substrates, and the carriers generated upon light exposure can become trapped by the internal molecular chains of the elastomer. This carrier trapping phenomenon reduces the mobility of the charge carriers within the photodetector, thereby slowing down the photo-switching process. Compared to conventional diode-based photodetectors, this results in slower response speeds. However, the response speed of this study was found to be faster than those of other stretchable photodetectors utilizing elastic substrates36,37,38,39,40. Furthermore, the differences between the rise time and delay time can be explained as follows: Upon light irradiation, electrons and holes are separated at the interface between the ZnS:Cu particles and the polymer, forming an interfacial dipole. This increases the dielectric permittivity of the ZnS:Cu-PUA composite film, which in turn proportionally increases the capacitance. The light is detected through the electrical signals generated from this process. When the light is removed, the separated electrons and holes recombine. However, if defects exist at the interface or the separated charges are stabilized within the polymer matrix, the energy required for recombination decreases, leading to a longer recombination time. As a result, the delay time is typically longer than the rise time. This improvement can be attributed to the high concentration (70 wt%) and uniform dispersion of ZnS:Cu particles within the PUA matrix, which mitigates the trapping phenomenon by providing more pathways for carrier movement and reducing the potential barriers within the composite material. The high concentration of ZnS:Cu particles enhances the photoconductive properties of the composite by facilitating efficient charge carrier generation and transport, leading to improved performance metrics such as faster response times. Furthermore, the dielectric constant of the PUA used in this study was measured to be 4.67 at 100 kHz as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. This value is significantly higher than the dielectric constants of widely used polymers such as PDMS, which has a dielectric constant of 2.54, and polyurethane, which has a dielectric constant of 1.61. This substantial difference contributed to the enhanced sensitivity of the capacitive photodetector. The dielectric constant, or relative permittivity, is a measure of a material’s ability to store electrical energy in an electric field. A higher dielectric constant indicates a greater capacity for charge storage. In the context of capacitive photodetectors, a higher dielectric constant material like PUA enhances the device’s ability to detect changes in capacitance when exposed to light. This improvement is due to the increased polarization within the PUA, which results in a more pronounced response to incident light. These findings underscore the potential of the AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetector for applications requiring high sensitivity and rapid response to varying light intensities, even in flexible and stretchable configurations.

The characteristics of the photodetector under mechanical deformation were systematically analyzed to elucidate its performance in various operational states. Fig. 4i presents a graph illustrating the rate of change in capacitance during bending operations. Remarkably, the photodetection characteristics of the bent photodetector remained virtually identical to those of the device in a flat state, even when the bending radius was reduced to 2 mm. This sustained performance is attributable to the composite’s substantial flexibility, the stable adhesion between the polymer surface and the AgNW electrode, and the formation of an additional encapsulation layer that mitigates electrode layer delamination. Fig. 4j delineates the results of the capacitance change rate when the photodetector is exposed to light irradiation while being subjected to tensile strain. The electrical signal output characteristics were maintained up to a 20% tensile strain. However, the sensitivity diminished to approximately 70% when a 30% tensile strain was applied. To investigate the underlying cause of this sensitivity reduction under 30% strain, the tensile strain was progressively increased, and the changing capacitance value was recorded under ambient conditions without additional light irradiation. The capacitance value of the device remained stable up to a change rate of 25%, but a precipitous decline was observed at approximately 27% strain (Fig. 4k). As can be seen in Fig. 3d, e, the electrode showed an increase in resistance value when stretched, but the encapsulated electrode recorded a relatively relaxed trend of resistance change. Figure 4k suggests that encapsulation alleviated the tendency of resistance to increase to a level where the capacitance value did not significantly decrease up to 25% of the tensile strain. However, it was found that the device lost the ability to accurately output the capacitance value when the tensile strain exceeded 25%.

This limitation is primarily due to the mechanical endurance thresholds of the AgNW-based electrode. Although the electrode surface is encapsulated with a PUA layer to prevent delamination during stretching, exceeding the material’s ductility limit inevitably leads to the rupture of the nanowire strands. Figure 4l presents a graph of the change in electrode resistance due to tensile strain, corroborating that resistance increased markedly at the same strain levels as the observed capacitance changes. Consequently, when elongation surpasses a specific threshold, the ability of the electrode to output the electrical signal generated within the device diminishes. However, within a strain range of up to 25%, the capacitance changes and the electrode resistance remained stable. This stability is the reason why the fabricated photodetector operated reliably within this strain range. The observation that the capacitance change rate was approximately 94% of the initial performance under a 20% tensile strain substantiates this conclusion. These findings underscore the critical interplay between mechanical deformation and the electrical characteristics of the photodetector, emphasizing the importance of material selection and structural design in maintaining performance under strain.

Assessment of the feasibility of artificial intelligence for light source and intensity classification

A deep learning algorithm was integrated into the device to exploit the superior mechanical stability and dual light source detection capabilities of the developed flexible photodetector. Deep learning algorithms possess the capacity to learn from data and classify input values based on discerned patterns, thereby facilitating the classification and prediction of detection patterns output by the photodetector under various conditions. For the deep learning model to achieve high learning efficiency and reliable test accuracy, it is imperative that the patterns corresponding to each condition exhibit a high degree of consistency. To evaluate the applicability of deep learning, an extensive dataset was collected, comprising over 11,138 samples. Each data point represented the rate of change in capacitance output by the photodetector when exposed to two types of light sources (448 nm and 505 nm) at varying power levels (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the maximum values). The photodetector was subjected to light irradiation under these conditions while in flat, bent, and stretched states. The deep learning model considered only the wavelength and power of the light irradiation as variables, without distinguishing between the different mechanical states of the device. This approach ensured that the classification accuracy of the deep learning model was contingent upon the uniformity of the patterns output by the device in response to light under consistent conditions, irrespective of the mechanical deformation state.

To ensure robustness and reliability, the deep learning model employed a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, which is particularly efficacious for pattern recognition tasks. The CNN was trained on the extensive dataset to classify the light source conditions based on the capacitance change patterns produced by the photodetector. The high level of consistency in the output patterns across various mechanical states was critical for the model’s performance. The integration of deep learning algorithms with the photodetector facilitates sophisticated analysis and prediction capabilities, thereby augmenting the device’s functionality in practical applications. By reliably classifying and predicting the photodetector’s response to different light sources, the system demonstrates its potential for deployment in advanced optical detection systems, where accurate and consistent performance under mechanical deformation is paramount41.

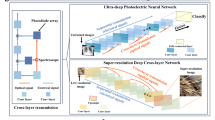

Figure 5a illustrates a schematic diagram depicting the process of applying data to a deep learning model and the architecture of the one-dimensional CNN (1D CNN) model employed in this study. The model architecture comprised a total of 29,850 parameters, which included two convolutional layers and two fully connected (dense) layers, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 10. Given the variability in initial data values across classified cycles, a normalization process was implemented to facilitate the learning of graphical patterns by the computer. To enhance the model’s learning rate, comprehensive preprocessing was performed using a quantile transformer. This technique transformed the data into values within the range of 0 to 1, effectively mitigating the impact of outliers. Subsequently, the dataset was augmented by duplicating the existing data through horizontal flipping, resulting in a total of 22,276 samples. These samples were then distributed across training, testing, and validation sets in a 3:1:1 ratio. To prevent overfitting, dropout layers were strategically inserted between the dense layers, and early stopping with a patience parameter of 10 was employed to halt training when the validation loss ceased to decrease. The dataset was divided into three subsets based on wavelengths (448 nm, 505 nm, and both) for separate training.

a Schematic representation of the data collection process involving two light sources (448 nm and 505 nm) and five levels of light intensity, along with the architecture of the 1D CNN deep learning model used in this study. b Confusion matrix illustrating the classification accuracy for the photodetector data under 448 nm light. c Confusion matrix for the photodetector data under 505 nm light. d Combined confusion matrix for data involving both 448 nm and 505 nm light sources. e Training and validation loss curves plotted against the number of epochs. f Accuracy curves for the training and validation datasets.

The confusion matrix results for each subset are presented in Fig. 5b, c. These matrices revealed that high accuracies exceeding 98% were achieved for the majority of classes. The confusion matrices provided a visual representation of the model’s performance in classifying the different light source conditions, indicating the effectiveness of the model. Supplementary Fig. 11 presents the loss and accuracy curves during the training process, demonstrating substantial similarity between the curves for the training and validation sets. This similarity indicates that the model selection was appropriate, as it effectively learned the patterns without overfitting. Finally, the model trained on data encompassing both light sources and varying luminous intensities (Fig. 5d) yielded impressive accuracies of 97.31%, 96.50%, and 96.52% on the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. The close resemblance between the loss and accuracy curves in Fig. 5e, f further supports the assertion that the proposed model effectively mitigates overfitting, ensuring robust performance across different datasets. These results underscore the efficacy of the 1D CNN model in accurately classifying the photodetector’s responses to various light sources and intensities. The comprehensive preprocessing, strategic use of dropout layers, and the implementation of early stopping were pivotal in achieving high accuracy and preventing overfitting.

Evaluation of deep learning models and comparison of AI-integrated capacitive type flexible photodetector for multi-wavelength detection

To rigorously evaluate the performance of our deep learning models for classification, we utilized the precision, recall, and F1 score metrics, which are critical for assessing the models’ accuracy and reliability. These metrics are derived from the fundamental outcomes of True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) classifications. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are calculated using Eqs. (2), (3), (4), and (5), respectively. Table 1 presents the precision, recall, and F1 scores for each model, thereby elucidating their efficacy in accurately identifying True Positives while minimizing both False Positives and False Negatives. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of the models’ performance, with the F1 score offering a balanced consideration of both precision and recall. This balance is essential for determining the overall effectiveness of the models in classification tasks42.

An important observation from the deep learning results is that the high classification accuracy can be attributed to the consistency of condition-specific data. The data were randomly collected from photodetectors in flat, bent, and stretched states, and it is a significant finding that when these datasets were combined, the deep learning model demonstrated a high degree of consistency in recognizing the patterns as similar. This indicates that the manufactured photodetector, as a stretchable electronic device, possesses highly stable light-sensing characteristics across different mechanical deformations. Furthermore, the introduction of deep learning models facilitated the accurate classification of light intensities from each light source, even in environments where two light sources were combined. This achievement is particularly noteworthy as it addresses a challenge that has not been extensively explored in the context of stretchable photodetectors. The ability of the deep learning model to maintain high accuracy under these conditions underscores the robustness and reliability of the photodetector’s performance.

In order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the fabricated AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs photodetectors, characteristic comparisons were made with the capacitive photodetectors reported so far27,28,43,44,45. The main parameters that the photodetector should have were extracted and summarized in Table 2, and very interesting differences were found. All capacitive photodetectors were tested under either single wavelength light or white light, meaning that the possibility of detecting multiple wavelengths was not considered at all. The rate of change in capacitance, which means sensitivity, was also at a high level, thanks to the good dielectric constant of PUA. Another notable point is that the response time belonged to a fast axis, due to the structure in which the electrodes were brought into direct contact with the photoactive layer. The path through which the generated carriers were moved was minimized, so the other photodetectors that responded relatively quickly were also cases in which two electrodes were formed directly in the photoactive layer. All of the flexible capacitive photodetectors introduced ZnS:Cu phosphor, which demonstrates that the particulate phosphor is easy to cope with the flexible deformation of the polymer support. Above all, it is important that no research results have been proven to be integrated with AI, indicating that no attempts have been made to classify the constituent wavelengths of incident light. Putting together the information obtained through this comparative analysis, it is confirmed that the manufactured AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs composite shows excellent performance for use as a flexible photodetector, and that it even has a unique light source classification ability through integration with AI. This shows the scalability of the functions that flexible photodetectors can express.

Evaluation of the cognitive ability of signal systems

Figure 6 presents the results of an experiment designed to determine whether the manipulated photodetector used as a prototype can effectively recognize the signal system in an environment where light is actually irradiated. The photodetector’s ability to distinguish the wavelength of light has been improved through integration with artificial intelligence. It can also be utilized in visual light communication (VLC) systems if it has the ability to identify signals in communication environments that are delivered at blinking frequencies. A typical VLC is the sharing of information between infrastructures through the flickering of traffic lights in road traffic systems. To verify this capability, the photodetector was attached to an electric kickboard, and a device mimicking an actual traffic light was introduced to collect the electric signal generated by blue light irradiation (Fig. 6a). The fabricated sensor, exhibiting excellent stretchability, adhered well to the curved surface of the kickboard. During the experiment, the flashing frequency of the signal was adjusted to 0.5 Hz, 1.0 Hz, and 1.5 Hz, and the corresponding data were recorded. Typically, a shorter flashing cycle of the blue signal indicates an imminent change to a red signal, necessitating a reduction in driving speed to prepare for stopping. This capability is crucial for ensuring safety in advanced driver protection and autonomous driving systems, where the ability to recognize flashing frequencies is essential. Furthermore, in real-world environments, the distance between the vehicle and the traffic light changes dynamically, affecting the amount of light reaching the photodetector. To account for these variables, an experiment was conducted to detect the signal by varying the linear distance between the photodetector and the traffic light to 1 m, 2 m, and 3 m. As illustrated by the various graphs in Fig. 4, the capacitance value gradually increases or decreases to a fully saturated state over time. The rise time and delay time are 102 ms and 498 ms, respectively, which indicates that it takes a considerable amount of time for the capacitance to change from 10% to 90% (or 90% to 10%). If the flash rate is too fast, the capacitance value may not fully recover to its initial state after the light is removed. Consequently, the flashing frequency causes subtle differences in the achieved capacitance values. Additionally, the distance between the traffic light and the photodetector results in greater changes in the capacitance values. This is because the intensity of light reaching the photodetector decreases as the distance increases. By analyzing the differences in the data under these conditions, we have successfully secured the cognitive ability of the signal system. The experiment was conducted outdoors, as shown in the digital image, with natural light interference affecting the light emitted from the traffic light. Despite the reduced capacitance change rate of 5.7% due to natural light interference (Supplementary Fig. 12), the signal was still clearly distinguishable.

a A digital image illustrating the experimental setup designed to assess the cognitive ability of the stretchable photodetector in recognizing the flash frequency of light emitted from traffic lights. b The deep learning model’s loss curves. c The accuracy curves of the deep learning model. d A confusion matrix summarizing the model’s classification accuracy under various conditions.

A total of 4561 data points were collected under nine different conditions, incorporating variations in flashing frequency and distance. The same deep learning model and pre-processing techniques described in Fig. 5 were employed in this analysis. The entire dataset underwent 100 epochs of training, with each epoch representing a complete pass through the dataset. As training progressed, the accuracy function exhibited a consistent increase, while the loss function demonstrated a corresponding decrease, as depicted in Fig. 6b, c. Notably, both the accuracy and loss curves for the validation set closely mirrored those of the training set, indicating a well-generalized model. Upon completion of the training process, the model demonstrated an impressive accuracy of 93.32% in randomly classifying the input signal patterns. The confusion matrix, presented in Fig. 6d, further corroborates these findings by illustrating that the signal was classified with high accuracy across nearly all classes. The confusion matrix serves as a visual representation of the model’s performance, showing the number of correct and incorrect predictions for each class, thereby highlighting the model’s efficacy in distinguishing between different signal patterns. These results conclusively demonstrate that the developed stretchable photodetector is capable of accurately recognizing the signal flashing system. This capability underscores the potential application of the photodetector as an intelligent sensing device in real-world scenarios. Its ability to perform advanced driver protection functions across various forms of mobility, including autonomous driving systems, is particularly noteworthy. The high accuracy and robust performance of the photodetector suggests that it can be reliably used in dynamic environments, enhancing safety and efficiency in transportation systems. The successful implementation of this deep learning architecture, combined with the photodetector’s mechanical flexibility and sensitivity, paves the way for its integration into intelligent photodetection systems. This advancement holds significant promise for improving the functionality and reliability of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and other mobility-related applications, thereby contributing to the development of safer and more intelligent VLC solutions.

Discussion

We have successfully developed a stretchable photodetector with enhanced multi-light source detection capabilities through the integration of artificial intelligence. The photodetector, fabricated using a composite structure of AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs, demonstrated exceptional mechanical stability, maintaining its photodetection characteristics under up to 25% tensile strain and a 2 mm bending radius. This robust stretchability ensures reliable performance under various mechanical deformations, making it suitable for flexible and stretching applications. The device exhibited high sensitivity to light at both 448 nm and 505 nm wavelengths, a critical feature for accurate and versatile light detection. By incorporating a 1D-CNN deep learning model, we achieved precise classification of light source power levels, even in mixed states. The consistency of data patterns across flat, bent, and stretched states contributed to the deep learning model’s impressive classification accuracy of 96.52%. This high sensory performance underscores the potential of our photodetector in applications requiring precise and reliable light detection. The straightforward manufacturing process and simple structural design of the photodetector enhance its practicality and scalability. The integration of deep learning algorithms with the stretchable photodetector not only enhances its functionality but also enables sophisticated capabilities, such as the classification of both wavelength and flashing frequency of light sources. This smart functionality demonstrates the potential for the photodetector to be utilized in advanced driver assistance systems and intelligent mobility solutions. One of the most significant applications of our developed photodetector is its potential use as a deep learning-enhanced traffic light detector. The photodetector’s ability to accurately recognize and classify signal patterns, even under mechanical deformation, enables it to detect and interpret traffic light signals reliably. This capability is crucial for ensuring safety and efficiency in autonomous driving systems, where accurate signal recognition is paramount.

Methods

Materials

Polyester diol (with a number-average molecular mass of approximately 1000) was acquired from Songwon (Korea). Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI), dibutyltin dilaurate, and 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich Chemicals (USA). Dipentaerylthritol-hexaacrylate (DPHA) and Irgacure 784 were purchased from SK Entis (Korea) and Shinyoung Rad. Chem. (Korea), respectively. C3 Nano (USA) provided a dispersion of AgNWs, featuring an average diameter of 21 nm and a mean length of 21 μm, suspended in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) at a concentration of 0.5 wt%. Temporary PDMS substrates utilized to transfer AgNWs as upper electrodes were fabricated with a sylgard 184 elastomer kit (Dow Corning, USA). All the mentioned chemical reagents were employed in their original state, without undergoing additional purification processes. Stringent precautionary measures and the use of personal protective equipment were strictly observed during the handling of these chemical substances to minimize potential risks, especially when dealing with hazardous acids.

Synthesis of PUA

Following the clear solution formation through heating at 70 °C in a flask containing polyester diol (25 g) and MEK (21 ml), the addition of IPDI (8.33 g) and dibutyltin dilaurate (catalyst) took place. The mixture was then heated at 60 °C for a duration of 3 h. Subsequently, HEA (2.90 g) and inhibitor were introduced at 0.1 wt.%, and the stirring process continued at 60 °C for an additional 3 h. The resulting mixture was cooled at room temperature for a sufficient period.

Fabrication of AgNWs/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNWs-based stretchable photodetector

After 2 ml of AgNW solution was dropped on a washed glass substrate, it was spin-coated at 1000 rpm for 30 s. The phosphor particles were evenly dispersed in the PUA solution through chemical and physical interactions. phosphor particles used as phosphors are usually non-polar or weakly polar materials, and when mixed with highly polar solvents, they may not mix well or may cause agglomeration. MEK, used as a solvent for PUA solutions, is an organic solvent with moderate polarity, which allows proper interaction with the phosphor particles, so that they can be evenly dispersed within the solvent. In addition, the amount of MEK was optimized to achieve the viscosity condition, which facilitates dispersion. In order to induce uniform distribution by the physical method, vortex mixing was performed for 10 min with high intensity and ultrasonic treatment was applied to prevent the aggregation of fine particles in the solution. In addition, when dispersion occurs, the polymer solution itself is absorbed onto the surface of the phosphor particles, improving the electrical or three-dimensional stability between the particles, thereby improving the dispersibility. The fabricated composite solution was applied over the AgNW electrode and spin-coated at 500 rpm for 1 min to form a uniformly thick film. Before achieving the last layer, AgNW-based upper electrode, UV irradiation was performed with a luminosity of 98.2 mW/cm2 and a distance of 110 mm between the lamp and the sample in a UV irradiation chamber (RX-CB400, Rainix, Korea) to induce complete curing of the PUA. On the surface where solidification was achieved, an AgNW-coated PDMS film was attached. The AgNW electrode formed in the PDMS layer was also implemented under the same spin coating conditions as previously mentioned, and oxygen atmospheric pressure plasma was performed for 5 min to temporarily hydrophilize the hydrophobic PDMS surface (Oxygen flow rate: 20 ml/min, power: 150 W). Over time, the transient hydrophilic properties disappear and the adhesion between the PDMS and AgNW electrodes weakens again. Rather, since AgNW electrodes have a high adhesion to the sticky ZnS:Cu-PUA surface, removing the attached film will ensure that the AgNW layer is well transferred back to the ZnS:Cu-PUA layer without any residue on the hydrophobic PDMS surface. Finally, we gently peeled off the AgNW/ZnS:Cu-PUA/AgNW film, which stands freely in water on a glass substrate.

Characterization of materials and devices

The crystal structure and phases of phosphors were examined via XRD analysis (XRD-6100, Shimadzu, Japan). 700 MHz 13C neuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; Oxford 700 NMR, VARIAN, Germany) was utilized for examining the formation of carbamide during PUA synthesis reaction. The surface microstructure of the sensor underwent meticulous analysis through field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; PE-300, Korea) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Multimode-8, Bruker, Germany). Additionally, optical characteristics were assessed using UV-visible spectroscopy (V-750, JASCO Corp., Japan). Tensile strength evaluations were conducted utilizing a universal testing machine (34SC-1, Instron Corp., USA). In order to perform photoswitching characterization, a photodetector was placed in a simple darkroom, and an electrical signal by light emitted from the light source was detected by the LCR meter (LCR-6100, GwINSTEK, Taiwan). A digital image depicting the experiment is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Yang, G., Li, J., Wu, M., Yu, X. & Yu, J. Recent Advances in Materials, Structures, and Applications of Flexible Photodetectors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2300340 (2023).

Chang, S. et al. Flexible and Stretchable Light-Emitting Diodes and Photodetectors for Human-Centric Optoelectronics. Chem. Rev. 124, 768 (2024).

An, C. et al. Two-Dimensional Material-Enhanced Flexible and Self-Healable Photodetector for Large-Area Photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100136 (2021).

Kim, H. J. et al. Detection of cracked teeth using a mechanoluminescence phosphor with a stretchable photodetector array. NPG Asia Mater. 14, 1 (2022).

Lee, H.-Y., Lu, G.-Z., Shen, J.-L., Lin, H.-Y. & Chen, Y.-F. Wrinkled 2D hybrid heterostructures for stretchable and sensitive photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 1637 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Flexible and stretchable photodetectors constructed by integrating photosensor, substrate, and electrode in one polymer matrix. Chem. Eng. J. 490, 151534 (2024).

Anabestani, H., Nabavi, S. & Bhadra, S. Advances in Flexible Organic Photodetectors: Materials and Applications. Nanomaterials 12, 3775 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Manipulating Nanowire Structures for an Enhanced Broad-Band Flexible Photothermoelectric Photodetector. Nano Lett. 22, 5929 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Perovskite photodetectors for flexible electronics: Recent advances and perspectives. Appl. Mater. Today 28, 101509 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Junction Field-Effect Transistors Based on PdSe2/MoS2 Heterostructures for Photodetectors Showing High Responsivity and Detectivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2106105 (2021).

Kuo, L. et al. All-Printed Ultrahigh-Responsivity MoS2 Nanosheet Photodetectors Enabled by Megasonic Exfoliation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203772 (2022).

Li, X. et al. High performance visible-SWIR flexible photodetector based on large-area InGaAs/InP PIN structure. Sci. Rep. 12, 1 (2022).

Deng, S. et al. NIR-UV Dual-Mode Photodetector with the Assistance of Machine-Learning Fabricated by Hybrid Laser Processing. Chem. Eng. J. 472, 144908 (2023).

Liu, R., Liang, Z., Yang, K. & Li, W. Machine Learning Based Visible Light Indoor Positioning With Single-LED and Single Rotatable Photo Detector. IEEE Photonics J. 14, 1 (2022).

Cao, W., Huang, Y., Fan, K.-C. & Zhang, J. A novel machine learning algorithm for large measurement range of quadrant photodetector. Optik 227, 165971 (2021).

Jiang, B. H. et al. Efficient, Ambient-Stable, All-Polymer Organic Photodetector for Machine Learning-Promoted Intelligent Monitoring of Indoor Plant Growth. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2203129 (2023).

Baek, K., Shin, S. & So, H. Decoupling thermal effects in GaN photodetectors for accurate measurement of ultraviolet intensity using deep neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 123, 106309 (2023).

Shin, H. S., Choi, S. B. & Kim, J.-W. Harnessing highly efficient triboelectric sensors and machine learning for self-powered intelligent security applications. Mater. Today Adv. 20, 100426 (2023).

Rajawat, A. S. et al. Fog Big Data Analysis for IoT Sensor Application Using Fusion Deep Learning. Math. Probl. Eng. 1, 6876688 (2021).

Lu, Y. et al. Decoding lip language using triboelectric sensors with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 1 (2022).

Bai, L., Han, Y., Lin, J., Xie, L. & Huang, W. Intrinsically stretchable conjugated polymers for flexible optoelectronic devices. Sci. Bull. 66, 2162 (2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Standalone real-time health monitoring patch based on a stretchable organic optoelectronic system. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg9180 (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Photoactive materials and devices for energy-efficient soft wearable optoelectronic systems. Nano Energy 110, 108379 (2023).

Yan, K. et al. Advanced Functional Electroactive and Photoactive Materials for Monitoring the Environmental Pollutants. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008227 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Manipulation of Photo-Active Ultralong Organic Phosphorescence in Host-Guest System. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2303099 (2024).

Tien, H.-C. et al. Intrinsically stretchable polymer semiconductors: molecular design, processing and device applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 2660 (2021).

Hwang, Y. et al. Highly stabilized flexible transparent capacitive photodetector based on silver nanowire/graphene hybrid electrodes. Sci. Rep. 11, 1 (2021).

Lim, H. S., Oh, J.-M. & Kim, J.-W. One-Way Continuous Deposition of Monolayer MXene Nanosheets for the Formation of Two Confronting Transparent Electrodes in Flexible Capacitive Photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 25400 (2021).

Li, R., Tang, L., Zhao, Q., Teng, K. S. & Lau, S. P. Facile synthesis of ZnS quantum dots at room temperature for ultra-violet photodetector applications. Chem. Phys. Lett. 742, 137127 (2020).

Ma, X., Dai, Y., Lou, Z., Huang, B. & Whangbo, H.-W. Electron–Hole Pair Generation of the Visible-Light Plasmonic Photocatalyst Ag@AgCl: Enhanced Optical Transitions Involving Midgap Defect States of AgC. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 12133 (2014).

Lebar, A., Aguiar, R., Oddy, A. & Petel, O. E. Particle surface effects on the spall strength of particle-reinforced polymer matrix composites. Int. J. Impact Eng. 150, 103801 (2021).

Mondal, D. K., Phukan, G., Paul, N. & Borah, J. P. Improved self heating and optical properties of bifunctional Fe3O4/ZnS nanocomposites for magnetic hyperthermia application. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 528, 167809 (2021).

Khan, A. et al. Effect of Sintering Time and Cl Doping Concentrations on Structural, Optical, and Luminescence Properties of ZnO Nanoparticles. Inorganics 12, 53 (2024).

Wang, H., Liu, Z., Zhou, Y. & Yang, R. The electronegativity modulation of rutile TiO2 nanorods by phosphate and its photocatalytic hydrogen production performance. Mater. Lett. 307, 131056 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. A Solar and Seawater Co-Involved Durable Rechargeable Battery Enabled by Crown Ether-Rich Polymer-Mediated Photoelectrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312729 (2024).

Ou, Z. et al. Enabling and Controlling Negative Photoconductance of FePS3 Nanosheets by Hot Carrier Trapping. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2000201 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Flexible, Low-Voltage, and n-Type Infrared Organic Phototransistors with Enhanced Photosensitivity via Interface Trapping Effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 36177 (2018).

Shakthivel, D., Nair, N. M. & Dahiya, R. Nanowire-Based Stretchable Photodetectors for Wearable Applications. IEEE Sens. Lett. 7, 1 (2024).

Trung, T. Q. et al. An Omnidirectionally Stretchable Photodetector Based on Organic–Inorganic Heterojunctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 35958 (2017).

Kumaresan, Y. et al. Kirigami and Mogul-Patterned Ultra-Stretchable High-Performance ZnO Nanowires-Based Photodetector. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2100804 (2021).

Kang, M. et al. High Accuracy Real-Time Multi-Gas Identification by a Batch-Uniform Gas Sensor Array and Deep Learning Algorithm. ACS Sens. 7, 430 (2022).

Kumer, J., Rajendran, B. & Sudarsan, S. D. Zero-Day Malware Classification and Detection Using Machine Learning. SN Comput. Sci. 5, 93 (2024).

Qasuria, T. A. et al. Stable perovskite based photodetector in impedance and capacitance mode. Results Phys. 15, 102699 (2019).

Shauloff, N. et al. Multispectral and Circular Polarization-Sensitive Carbon Dot-Polydiacetylene Capacitive Photodetector. Small 19, 2206519 (2023).

Shauloff, N. et al. Carbon dot / thermo-responsive polymer capacitive wavelength-specific photodetector. Carbon 213, 118211 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants (Number RS-2023-00247545) funded by the Korean government (MSIP). This research was also funded and conducted under the Competency Development Program for Industry Specialists of the Korean Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), operated by Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) (No. P0023704, Semiconductor-Track Graduate School (SKKU)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.C.: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. J.S.C: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, J.-W.Y.: Supervision, Project administration. Y.K.: Supervision, Project administration. J.-W.K.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. All the authors read and revised the manuscript. S.B.C., J.S.Choi. and H.S.S. Contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, S.B., Choi, J.S., Shin, H.S. et al. Deep learning-developed multi-light source discrimination capability of stretchable capacitive photodetector. npj Flex Electron 9, 44 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00400-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00400-z