Abstract

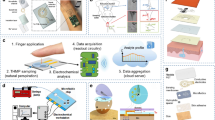

The identification of novel physiological biomarkers in sweat requires real-time sampling and analysis. Here, we present the microfabrication of epidermal microfluidics within textiles via stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing. Flexible SLA resin defines impermeable fluid-guiding microstructures in textile microfluidic modules. Their vertical stacking reduces device footprint and required sample volume, and facilitates on-body fluid collection, storage, and transport. Embedded internal modules act as a reservoir and injection valve, releasing a defined volume of sweat to the sensing unit. The pressure gradient across the modules provides a vertically distributed, capillary-driven sweat flow, guided by the wicking power of the textile structure. Their full integration into apparels offers non-cumulative flow through an extended air-liquid interface, ensuring continuous sweat transfer and evaporation. For real-time sweat analysis, we use a remotely screen-printed potassium (K+) ion detector. This modular approach provides fabric-integrated, mechanically ergonomic microfluidics with multi-parameter detection through rapid additive manufacturing for advanced point-of-care diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The understanding and manipulation of fluid transport at the micron scale have driven the development of microfluidic biosensors, providing precise analytical control across fields such as environmental monitoring, food safety, and healthcare diagnostics1,2. These advances have paved the way for point-of-care (POC) devices, yet the challenge of non-invasive, real-time monitoring remains significant. Among body fluids, sweat is a particularly attractive candidate for wearable sensors, offering a non-invasive, portable and personalized solution for tracking health biomarkers3. However, the inherent limitations of sweat—namely low sample volumes easily subject to contamination and evaporation—pose formidable obstacles4.

Wearable microfluidic devices have emerged to address this, utilizing soft, flexible, and hypoallergenic materials like PDMS and polyurethane to facilitate sample handling in sweat-sensing patches5,6. Commonly used materials are elastomers, yet more recently, alternative materials such as paper, yarns, and fabrics have demonstrated potential for capillary-based fluid management in microfluidic circuits7. Capillary flow in natural or synthetic threads is exploited for functional components (e.g. microvalves, fluid velocity control elements, micromixers, and microfilters), which are later combined into textile architectures by waving, knotting, knitting, or stitching yarns8,9. Yarns have been successfully exploited for precise manipulation of body fluids using external electric fields in low-cost electrophoretic diagnostic assays, for wound treatment by in-situ drug delivery, or for DNA extraction from biological samples10,11,12. Recent efforts report utilizing gold threads, functionalized with glucose oxidase, which serve as inexpensive, disposable, wearable sweat collectors with electrochemical sensing capabilities13. Furthermore, thread-based multiplexed sensing patches have been demonstrated14. Despite promising developments and advances, these examples demonstrate multiple issues: device scalability, one-dimensional fluid movement limitations along the threads and labor-intensive fabrication processes, requiring stitching and pre- and post-varnishing steps15.

Instead, fabric scale integration can provide two-dimensional flows over larger areas for simplified architecture and fabrication. Collectors, channels and reservoirs can be obtained by selectively patterning hydrophobic barriers on fabric substrates by altering the surface chemistry or depositing water-repellent materials (e.g. PDMS, waxes, tapes)16,17. This approach has enabled fabrics to have integrated digital wearable droplet flowmetry18, fractal-based sweat collection structures19, and multimodal platforms able to monitor sweat rate and skin temperature wirelessly20, reproducing planar devices configuration. Given the demand for non-invasive, real-time health monitoring, wearable devices that leverage sweat as a biofluid for continuous analysis have gained significant attention. Key questions that stand today in wearable biosensing is how can we harness the natural wicking properties of textiles to design scalable, cost-effective, and efficient sweat collection systems that seamlessly integrate into garments for on-body, continuous monitoring. Addressing this challenge, recent developments have explored integrating microfluidics with textiles, though progress remains constrained by fabrication complexity and performance trade-offs21. The emerging field of 3D printing has shown promise for precision manufacturing, but its potential in wearable textiles remains largely underutilized22,23. Continuous progress in this field with regards to printing technology and materials chemistry, brings the current printing resolution to within dimensions comparable to, and even below, fabric thicknesses. Moreover, several studies have been carried out to better understand how to control and optimize the liquid absorption in porous wearable materials, which is governed by complex phenomena that can be beneficial from the point of view of fluid dynamics and significantly influence the sensing outcomes. The full potential of structural relationships in the integration capability and devices performance in the field of e-textile biosensors have not been exploited yet. Computational analysis of a modeled knitted fabric can quantify the concentration of sweat biomarkers at the level of a garment’s absorbing surface24, numerical models can describe the interfacial transport on super-hydrophobic fabrics, and theoretical derivations allowing to calculate the minimum flow resistance and nodal distance to design a fractal fabric sweat collector19. By leveraging the power of simulation tools, it is possible to reveal the fundamental mechanisms of capillary-driven flows and guide the design thinking process for next generation wearable microfluidics fully integrated in our garments. Therefore, an emerging need for accurate prediction of capillary imbibition requires further studies by considering additional factors, such as tortuosity, dynamic contact angle, and pore shape25.

This study proposes three innovative components to address actual challenges to build next generation wearable biosensing through an innovative and scalable way of fabrication, integration and sensing. In this study, we present a wearable sweat sensing manufacturing that leverages state-of-the-art stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing to embed microfluidic modules within wicking textiles. Using photopolymerizable resins, we form impermeable microchannel boundaries inside porous fabric, creating a system capable of guiding sweat flow precisely. Our design introduces a vertical microfluidic architecture inspired by origami folding, enabling a compact, multi-layered design that efficiently manages sweat collection, storage, and transport all in one. This vertical configuration not only minimizes the device footprint but also eliminates the need for adhesives, making it ideal for ergonomic and unobtrusive wear. Furthermore, we engineered an integrated inner module that functions as a sweat reservoir and valve, using capillary pressure gradients to regulate fluid movement and optimize sample delivery. Supported by analytical modeling and 3D numerical simulations, we reveal how the intricate interplay of capillary forces, flow resistance, and textile tortuosity governs sweat dynamics in our system. The designed differences in the wicking power generate a capillary pressure gradient along the referred modules, allowing a programmed and continuous sweat sampling, storing, and sensing specific to the traditional 2D microfluidic chips. To validate our model, we integrate a flexible, screen-printed organic electrochemical transistor for in-situ potassium ion (K+) sensing. The sensor demonstrates high sensitivity and selectivity, which is key for monitoring dehydration, electrolyte balance, and cardiovascular health26,27. This proof of concept highlights the potential for multi-parametric monitoring through adaptable and scalable epifluidic designs. By uniting advanced 3D printing techniques with the intrinsic capillary properties of textiles, our research offers an ergonomic and skin respecting approach to wearable, real-time sweat on-body sampling and analysis, capable of revolutionizing personalized health diagnostics.

Results

Making 3D textile microfluidics with high resolution 3D SLA printing

The following part details the fabrication process of multi-layer textile microfluidics created by SLA 3D printing and its functional design. This is followed by an in-depth characterization of the system’s physical properties, including resolution, flexibility, and fluid transport behavior. To build a model textile microfluidics we used three commercially available fabrics: woven polyester, nonwoven cellulose and nonwoven cellulose/polyester.

Our fabrication process introduces a novel approach to textile microfluidics manufacturing through the direct use of SLA 3D printing. By successfully utilizing flexible resin with braided fibers, we selectively create impermeable regions and shape hydrophilic microchannels boundaries within the textile substrate. Although previous research has demonstrated proof-of-concept 3D printing using resins or fused deposition modeling on textiles28, this study applies SLA printing directly to various textile samples, laminated onto the printer stage’s building platform. Then during printing, the textile is immersed in a vat of liquid resin. A critical aspect of the process lies in the resin’s capillary absorption into the textile structure, allowing for its precise micropatterning. This resin impregnation step strongly depends on the textile’s structure (e.g., knitted, woven) and its inherent wicking properties. It is necessary to ensure homogeneous impregnation of the resin, a preconditioning step of the textile is required. A detailed process is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Using a UV laser source, the resin is selectively polymerized within the textile layer by layer, beginning at the focal plane of the initial stage until the design is complete (Fig. 1A). The thickness of each layer determines the printed feature dimensions, automatically calculated based on the digital model, resin properties, and the tool’s resolution (in this case, 50 µm). Once the printing is completed, post-processing steps involve washing out un-polymerized resin and curing the polymerized structures. This approach achieves high-precision resin and resin-free patterns, as shown in the light-blue and white-colored regions in Fig. 1A. Solidified resin structures result in integrated 3D channels within textile fibers rather than simply atop the fabric (Fig. 1A), with resin-free areas serving as fluidic channels for sweat transport. This flexible, elastomeric resin provides an ultimate tensile strength of 8.9 MPa29 contributing to the microfluidic structure’s flexibility and user comfort (Supplementary Fig. 2, demonstrating both pristine patterned resin (A,B) and textile-embedded configurations (C,D)).

A SLA 3D printing with textile integration: the fabric is fixed to the building platform and immersed in liquid photosensitive resin, selectively photopolymerized by a UV light source following a multi-layered 3D digital model. B Origami-inspired assembly of microfluidic modules. On the left: overall assembly utilizing origami-inspired folding. Upper-right: top view of the top microfluidic module with integrated OECT sensor. Lower-right: cross-sectional view illustrating vertical sweat flow through modules. C Exploded view of cloth-integrated sweat platform, depicting the vertical arrangement sequence of collection, storage, and sensing modules within designated garment space.

Following the printing process, individual microfluidic modules are vertically stacked in an origami-inspired fashion, as depicted in Fig. 1B. This folding technique allows for a diverse variety of easy-to-achieve polyhedric device configurations thanks to configurable and assisted assembling. To date, previous research groups have exploited this approach for 2D and 3D sensor assemblies involving enzymatic, DNA, immuno-, molecular imprinting, cell-based sensors, and pH and Na+ sweat monitoring on paper substrates30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Here, the origami-like folding transitions planar configurations into three-dimensional ones, enabling a hybrid lateral and vertical microfluidic flow through a module’s self-alignment.

To develop a precise sweat analysis platform, the sensor unit should be integrated directly with the textile microfluidic module (Fig. 1B, upper-right). The top microfluidic lateral module design supports direct printing or lamination of a prefabricated electronic sensing device. The cross-sectional view of the assembled 3D textile microfluidics (Fig. 1B, lower-right) illustrates the vertical sweat flow path through the modular layers toward the sensing unit and ultimately to an outlet for evaporation. Once assembled, the platform integrates seamlessly into clothing due to its flexible and monolithic structure (Fig. 1C). With the advances in digital textile design and apparel production, such module assembly can be achieved through self-folding behavior of weft-knit or knit stitch fabrics at their design step38,39. The resulting garment-integrated system provides efficient sweat collection, storage, and biochemical sensing of sweat directly from the human body.

The vat polymerization SLA process offers exceptionally high resolutions and enables the digital fabrication of geometrically complex structures, paving the way for sustainable, personalized, and accessible point-of-care devices. However, integrating porous textile materials as an inherent component of 3D-printed objects presents a novel challenge that requires a dedicated investigation of this approach’s possibilities. The role of the textile substrate is decisive, as its characteristics define achievable microfluidic channel resolutions and suction capabilities. Specifically, the pores between the fibers must be adequately filled with resin while continuing to allow the UV light to pass through the targeted voxel in order to implement accurate photopolymerization.

Unlike standard SLA processes, our technique involves textile lamination onto the build platform, introducing potential deviations due to light scattering and diffraction effects. We therefore assess the versatility and possibilities of our approach by defining the printing outcome with different types of textiles. The primary metric for microfluidic channel fabrication is the channel width (i.e., the space between printed regions) which defines the handling volumes and flow dynamics. We investigated the 3D printing outcomes on four textile samples varying in thickness, structure, composition, pore size, wicking properties, water capacity, and flow speed as representative samples. To assess the achievable resolution for each of the substrates, we designed a series of channels with widths ranging from 0.1 to 2.0 mm (Supplementary Fig. 3) and measured the resulting dimensions post-fabrication.

As anticipated, our results indicate a reduction in actual channel width compared to the CAD design. We ascribe this discrepancy to the light scattering phenomenon. Unlike the standard SLA process, in our setup the incident laser beam encounters the laminated textile at the level of the resin layer to be polymerized. We believe that the fibers and irregularities between the build stage and the fabric cause diffraction of light causing over-polymerization at the channel edge40. Despite the textile’s relatively low thickness, this effect can slightly disturb the incident light trajectory and amplify the light scattering compared to when no substrate is present. The observed reduction in channel widths ranged from 21.1% to 43.9% (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 3). The reported values in Fig. 2A represent the correction factor one has to consider when designing microfluidics channels for specific substrates. We obtained comparable values for the textiles III and IV (24.7 and 23.3%) that have similar thicknesses (~153 and 162 μm respectively), the same structure (nonwoven) but different compositions. Whereas we observed a slightly lower value in the woven textile II (21.1%) which is ~150 μm thick and we got the highest value in the knitted textile I (43.9%) which has a thickness of around 350 μm. This suggests that textile structure and, most notably, thickness play critical roles in light scattering. Thicker textiles cause greater beam interference and ultimately lead to reduced patterning precision. This can be balanced by the choice of the materials (both resin and fabric) in combination with the process parameters adjustment.

A Measured reduction in channel width (expressed as a percentage) relative to the CAD design across different textile types. B 3D- printed resin elements embedded within various textiles: woven (top left), knitted (bottom left), and nonwoven (right). C Unfolded view of the 3D textile microfluidics showing the 5 different modules: sweat collector (module A), sweat storage (module C), sensing unit (module E), and connecting in-hole bridges (modules B and D). The textile sample shown is cut from a larger piece of fabric for better visualization. D Proposed all-in-one assembly of a proof-of-concept wristband sweat platform.

It is worth mentioning that these edge effects, inherent to various 3D printing processes, do not compromise overall fabrication. The achievable resolution is adequate for microfluidics purposes, as will be detailed bellow. Adaptation in CAD design to obtain the desired outcome on a specific textile proves to be a relatively straightforward and reliable strategy needed to account for over-polymerization. In all tested cases, we successfully embedded flexible resin into different textiles (Fig. 2B) with high resolution, comparable to or surpassing established processes used to pattern hydrophobic materials into textiles for fluid-handling purposes17,41,42.

As a representative result, microchannels obtained in textile IV must have a width range of 500–600 μm to ensure continuous and regular fluid flow while guaranteeing a miniaturized, low-volume fluid-handling device (Fig. 2B). Our approach offers rapid (one microfluidics device printing time equal to 5–15 min) and digital manufacturing, showcasing the high versatility and precision of the innovative use of SLA 3D printing.

Microfluidic modules operation and integrability

To provide a comprehensive overview, Fig. 2C demonstrates the unfolded 3D-printed textile-microfluidics modules, with 5 distinct designs tailored for specific fluid-handling tasks. The modular series begins with the sweat collector (module A), which interfaces directly with the skin over a large contact area to collect sweat through eight circular inlets along radially arranged channels. On its opposite side, module A is connected to module B, which features a single, centrally-located circular design that facilitates the collection and transfer of the fluid. This structure acts as an in-hole vertical bridge between modules A and C.

Module C functions as a defined-capacity sweat reservoir, featuring a spiral pattern, which releases toward the sensing module when full. It is designed to store up to 100 μl of sweat – an intermediate volume needed as indicated within the literature-reported range of 10–200 uL43. This reservoir module is a key innovation that minimizes variations in the sweating rate, evaporation, and premature drying, which can lead to salt crystal formation and fluidic circuit blockage before sensing. Moreover, module C represents a critical solution in this work for the analysis of precise sweat volumes, independently of the user’s sweat rates, inter- and intra-subject variability, thus ensuring accurate quantitative detection.

Module D functions analogously to module B by connecting module C’s reservoir with the sensing unit, module E. This final module allows for the fluid’s lateral transport to the sensor interface (not shown in Fig. 2C), enabling in situ, real-time sweat analysis. After, the analyzed sweat sample is then pulled toward a high-surface-area disposal zone for evaporation. This expanded shape maximizes the surface area exposed to the air, boosting evaporation and reducing the viscous resistive force of fresh sweat thereby facilitating adequate sample renewal. Additionally, partial contact with the air allows this area to act as the principal air vent required for textile-microfluidics to operate. Its dimension plays a key role in controlling the capillary wicking and evaporation rates44. This microfluidics element is designed to enable continuous and long-term fluid withdrawal without requiring external pumping systems. The mechanisms governing fluidic flow are described in Capillary-driven flow control within textiles section.

The proposed SLA 3D printing technique permits the fabrication of microfluidics on large-area textile samples. This allows for precise resin patterning on a designated portion of a textile specimen, which can be later shaped and assembled into wearable garments through standard cloth manufacturing techniques. Examples of potential applications includes headbands, wristbands, chest straps, socks, and t-shirt patches. To validate this concept, Fig. 3D illustrates the monolithic assembly and integration of the textile microfluidics into a wristband where the sweat sensing platform is assembled only through folding, eliminating the need for stitching or sewing. This process involves cutting away the excess textile where the microfluidics modules need to be stacked while retaining plain textile portions to be wrapped around the wrist forming the band. This design ensures that module A is in close contact with the skin for optimal sweat collection, while a snap button secures the wrist device to the wearer.

A Schematic representation of microfluidic channel thickness variation, with images of a cut channel profile from a front and tilted perspective. The scale bar is 200 μm. B Schematic (top) and pictures of an in-hole fluidic module cross-section in its dry state (middle) and upon water absorption (bottom), illustrating increased textile thickness after swelling. C Lateral fluid dynamic along the A module’s inlets and channels, and subsequent flow along the C and E channels as a result of the vertical fluid passage through modules B and D. D Microfluidics top and bottom views where the modules’ aligned stacking and fluid passage are visible. E Image of module A folded around a 2.5 mm Ø cylinder showcasing its conformability over high-curvature surfaces.

The presented manufacturing process detailed herein establishes compatibility with a variety of textile-like materials where resin is selectively patterned between the fiber gaps. Effective fluid handling and confinement strictly depend on accurate channel definition. The high-precision light source process reveals a sharp and defined interface between the resin (w/ resin) and the resin-free textile (w/o resin) as depicted in Fig. 3A (top). Cross-sectional imaging of microchannels (Fig. 3A, middle) shows that the w/ resin textile portion exhibits a thickness equal to 283 ± 9 μm, nearly double that of the plain textile thickness, measured at 162 ± 4 μm. Moreover, the cross-section displays a uniform assembly of the patterned channels into the textiles, resulting in a robust and compact, yet flexible microfluidic device. The tilted view (Fig. 3A bottom) illustrates a well-defined edge front line essential for fluid regular flow and confinement. High-resolution digital microscopy of the resin-textile surface reveals a uniform material integration, with overall planarity of the stacked modules further guaranteed by the swelling, due to water uptake, at the level of circular in-holes. Indeed, the thickness difference between the portions of fabric w/ and w/o resin, shown in Fig. 3A, is compensated by the thickness increase (+35%) when hydrophilic in-holes are wet (Fig. 3B). By optimizing the thickness of the printed resin layers with those of the textile, the resulting embedded fluidic modules achieve excellent planarity.

Following the fabrication flow, fluid dynamics tests validate the liquid wicking and guiding capability of textile-microfluidic conduits. As depicted in Fig. 3C, precise lateral fluid flow is indicated by black arrows; when liquid is dispensed from the module A inlets, it travels laterally along the radially arranged channels (also see Supplementary Video 1). The liquid progresses through the internal in-hole module B bridge, seamlessly transitioning to module C, where both lateral and vertical flows are maintained. Here, we can appreciate the successful lateral and vertical flows from module A to C. Likewise, the fluid reaches module E, traveling from the inlets, then laterally along the 90° turn, and toward the rectangular sensing chamber, without any fluid leakage (see Fig. 3C and Supplementary Video 2). The successful coordination of lateral and vertical flow within the origami-stacked modules is illustrated in Fig. 3D, where fluid fills module A (top), flows through module C (visible with backlighting in a spiral pattern), and reaches module E (180° flipped view). Moreover, Fig. 3D highlights the precise alignment of all modules assisted by the origami-like pre-programmable folding; the in-hole bridges are superimposed to vertically connect the stacked microfluidics modules. The system planarity, in combination with a precise origami-assisted alignment and the natural fluid flow through the hydrophilic channels, provides adequate inter-module physical contact to ensure autonomous, uninterrupted fluid passage across the modules. The whole system results in a compact in size, fully integrated and ergonomic system due to the textile and resin flexible properties. The module’s bendability is demonstrated in Fig. 3E where, for illustrative purposes, module A is folded around a cylinder with a 2.5 mm radius showing excellent resilience to the applied bending stress on non-woven textile. In addition, Supplementary Video 3 confirms a reliable and straight integration of the printing process in the development of vertical wearables microfluidic module. Even if the final assembled module is less flexible than a single layer, presented in Fig. 3E, it is still mechanically bendable to ensure comfortable on-body wearing. Ultimately, the robust bonding between modules, obtained through a pressure-sensitive double-sided tape, is evidenced by its structural integrity after 16 h of immersion in stirred water (Supplementary Video 4). Additional stitching can be envisioned in the garment finishing step for further consolidation preventing misalignment or detachment of the origami structure.

This novel process offers a robust pathway for the integration of flexible microfluidic functionality within textiles, setting a new standard for wearables manufacturing.

Capillary-driven flow control via gradient generation within textiles

The 3D textile microfluidic system described above allows for passive fluid flow across its modules. However, a reliable sweat analysis requires a controlled unidirectional fluid sampling at the sensing module. This is accomplished by leveraging the capillary action gradient, generated through materials of varying porosity levels (e.g., textile, paper). We outline the methodology for establishing a capillary pressure gradient, theorize the implicated pressures and viscous forces, and experimentally describe them to provide criteria guidelines on how to conceive and optimize a controlled sweat-handling platform on textile substrates.

To develop a semi-controlled sweat-handling system, we combine the hydrophilic and hydrophobic patterned textile with three materials of different porosity (PMs). Thus, PMs with intrinsically different hydrophilic degrees offer solutions for a fully textile- or paper-based microfluidic platform generation. As a feasibility study, we used both textiles and paper to stress the versatility and compatibility of the fabrication method for a variety of porous substrates. The PMs specifications are reported in Supplementary Table 1. This principle is schematically illustrated in Fig. 4A, which reproduces the pathway described in Fig. 1B. Modules A and B were constructed from a textile with medium wicking power (1, 100% woven polyester), modules C and D from high wicking power paper (2, 100% cellulose), and module E and the evaporation pad from super-hydrophilic textile (3, non-woven 50% cellulose/50% polyester). The 3D printing into different PMs at once is achieved by laminating the PM samples onto the build platform and making sure to align them with the CAD design positions (Supplementary Fig. 4). By combining PMs with increasing wicking properties, sweat travels in a semi-controlled manner from the skin toward the sensing chamber through modules A-B, C-D, and finally E.

A Schematic of a 3 porous materials approach to develop a controlled sweat flow. B Equivalent electronic circuit scheme of forces involved when the fluid flows within PM 1, and the respective photograph. C Equivalent electronic circuit model when the fluid is pulled from PM 1 to PM 2, with a photograph showing the fluid front. D Equivalent electronic circuit when the fluid passes from PM 2 to PM 3, and a photograph demonstrating the total fluid accumulation and spreading in the PM 3.

The generated capillary gradient was further evaluated and reproduced in a simplified experimental set-up in which a dispensed fluid travels along three rectangular modules. For better understanding, the system can be likened to an equivalent electronic circuit where fluid flow represents an electric current driven by a capillary pressure differential (akin to a potential difference) and opposed by viscous forces (analogous to a resistive element). Fig. 4B shows water (of light blue color) being absorbed once dispensed on the bottom module composed of PM 1. The capillary-driven flow in PM 1 is therefore represented by a resistor (R1) and a capacitor (P1) in series (Fig. 4B, left). R1 is oriented against the flow direction and it counteracts the capillary pressure P1 at the fluid meniscus45,46,47.

By analogy to the general microfluidic circuits that are based on the hydrophilic microchannel elements48, a hydrophilic textile generates a suction pressure at its wetting front, allowing for a flow with a velocity that is proportional to the pressure magnitude and inversely to the resistance. Once the first module is filled with fluid, it goes to the second one (Fig. 4C). Similarly, PM 2 is represented by a different resistance R2, and capillary pressure P2; P2 is bigger than P1 and it actively pushes the fluid into the accumulation module C. Subsequently, PM 3 generates a P3 > P2 creating a sufficiently large capillary pressure gradient able to quickly empty the C module, channeling the sweat sample towards the E module. From the photograph of Fig. 4D, the fluid accumulation in module 3 and toward the large waste/evaporation pad is confirmed. Inversely, if the system was a single PM channel, we would observe an evenly spread fluid all along. This is confirmed in the control experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5) in which none of the single low/medium/high wicking textile channels can be drained as the capillary pressure does not change (ΔP = 0). The liquid is spread over the channel with no gradient and it stays at the level of the inlet. Thus, we created a gradient system in which P3 > P2 > P1 allows for fine-tuning of the fluid collection, storage, and transport. As the presented system does not employ valves, the approach here responds to our need for simplified, but semi-controlled, fluid handling. Additionally, the on-cloth integration, particularly of the E module, allows for continuous fluid withdrawal, as its volumetric capacitance is not limited by a defined surface. In this way, the fluid spreads over an air-liquid interface with a large surface area, offering its fast evaporation and consecutive flow maintenance in the microfluidic sensing system.

As outlined in the previous section, P and R are the driving forces that generate the flow gradient that we experimentally assessed through the analysis of the capillary pressure, the viscous forces, and the substrate tortuosity. We first built a setup, schematized in Fig. 5A, to quantify the generated capillary pressure (PC) of each studied porous material (P1, P2, P3). In this setup, the dispensed water (20 μl) is pulled inside the 500 μm microchannel by the capillary pump of the porous material. We can then calculate the microchannel PC by using the Young-Laplace equation (Eq. (1)) In relation to contact angle, channel size, and surface tension49:

where h and w are the microchannel height and width, respectively, and ϴ is the contact angle of the four microchannel walls. This calculation allows for the estimation of the textile’s PC value and its comparison with other similarly tested porous materials. When the system reaches a no-flow balanced-force static state (fluid held in place with no net flow), the PM and the microchannel generate a comparable PC. We experimentally tried to reach the no-flow balanced-force static state by changing the retention channel size ( = h or w) and the contact angles of the top channel, left, and right walls (in our system θbottom is kept ≈ 90°, while θtop = θleft = θright). Figure 5B shows photographs of the setup for the studied PM and the respectively calculated PC values through sequential tests described in Supplementary Note 1. We quantified a PC gradient of ≤873 ≤ 1496 < 1624 Pa, estimating a ΔPC > 600 Pa necessary for successful fluid drain control, described in Capillary-driven flow control within textiles section.

A Schematics of fluidic channels setup built to estimate the PC. B Photographs of the fluidic setup and the reporting of estimated PC values that each PM generates. Abbreviations: c.a = contact angle. C Spread kinetics of 50 μl of water flowing in 10 × 50 cm closed PM channels. The bold lines are the average values over three measurements and shaded areas are the corresponding standard errors. Inset: spread kinetics of water when flowing in a composite closed channel. D Textile-based closed fluidic channel model used to simulate the water flow. Green and red shaded pipe-like elements represent the woven textile’s threads, the square-section channel stands for the textile pores, and the yellow meniscus represents the water-air interface movement. E Time frames of the simulation taken at 18, 59, and 150 μs. F Fluid imbibition vs. time graph generated from the simulated fluid front. ax-regions correspond to high flow velocity, while bx-regions highlight when the flow slows down due to the resistance caused by the change in the direction of pores.

Next, we examined the viscous forces (R) as a factor that regulates the flow rate (Q). Fig. 5C shows the imbibition distance within closed channels for the PM 1, 2, 3. This graph shows the fluid velocity as the slope of the tangent to the curve at each instant. Three different capillary flow rates are visible with a relation Q1 < Q2 < Q3. The inset of Fig. 5C shows the traveling distance of fluid flowing in a composite channel; a sudden increase in the flow velocity is observed at each fluid passage from one material to the next one (more hydrophilic one). Considering the inverse relation between viscous forces R and flow rate Q, we therefore experimentally found that R1 > R2 > R3, consistent with gradient generation theory.

Furthermore, from the data in Fig. 5C, we also identified that the velocity is inversely proportional to the pore size50 and is not constant. The non-linearity of the PM1, PM2, PM3 curves suggests that the liquid filling might follow Lucas-Washburn behavior (Supplementary Eq. (3) in Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. 6), resulting in a decreasing flow rate over-time due to intramolecular friction within the liquid25. However, the Lucas-Washburn equation does not satisfactorily fit the experimental data, as the capillary coefficient reduces as the flow marches downstream through the textile. This is because the different pores shapes and orientation cause a tortuous flow whose impact is excluded from the equation. We also report the presence of tortuosity through computational fluid dynamics (CFD). The numerical simulation of the water passage through a woven textile section is modeled as a porous structure with simplified 10 × 10 μm rectangular pores (Fig. 5D). From the transient simulation phase tracer (Supplementary Video 5) also shown in Fig. 5E, we can follow the liquid-air interface (in yellow) that propagates into the pores at different moments, which are parallel or perpendicular to the upstream-downstream directions. From the imbibition vs. time plot (Fig. 5F), extrapolated from the simulation, we observe not only the progressing flow rate decrease (Lucas-Washburn behavior), but we also distinguish the tortuosity thanks to the short time window (160 μs). In Fig. 5F, regions a and b identify 2 main behaviors: when liquid is quickly wicked into pores parallel to the thread’s direction (a1 = curve’s steep slope), and when liquid slows down (b1) due to a tortuous change in direction to travel into perpendicular pores which require more time to be filled. By continuing marching downstream, this behavior repeats (a2, b2). Moreover, we can identify the relationship, in terms of duration, for which a1 < a2 < a3 < ..<an and b1 < b,<..<bn that expresses the flow rate delays due to the progressive increase in resistance. Figure 5F summarizes the combination of both the classic Lucas-Washburn relationship and the tortuosity effect that regulates the flow in the presented microfluidics system. The model greatly explains leading mechanisms in our application, therefore needs to be further evaluated in more complex porous structures and geometries beyond the directionality aspect of the flow including non-linearities with dominant behaviors, liquid-textile molecular affinities etc.

A Screen-printed OECT device integrated into the microfluidics’ E module. Inset: the magnified image of the channel and gate electrodes of the OECT, scale bar represents 1 mm. B Picture of the microfluidics analytical module while twisting to appreciate its conformability and mechanical stability. C Graphical representation of the OECT device architecture, operation, and functionalization as a K+ sensor. D Transfer sweeps of the non-functionalized OECT (ISM-free) and of the functionalized (ISM) recorded at VD = −0.4 V. E I-V output curves of the ISM and ISM-free OECTs. F Current modulation curves where the data points represent the measured current at the equilibrium of real-time measurements (inset) upon the addition of NaCl and KCl concentrations. The calibration curves are obtained by the linear fitting (R2(K+) = 0.96, R2(Na+) = 0.91); error bars represent the standard errors over three measurements on three different devices.

As a result, based on the analysis above, we quantified and compared the capillary pressure gradient and the fluid resistances, in terms of ΔPC and flow rates respectively, with consistency between expected phenomena and experimental results. Altogether, the capillary-driven flow study across textile-based microfluidics elucidates the forces at work and provides insights into how the choice of materials and their combination with the design significantly affect fluid handling.

Vertical textile microfluidic sweat OECT-based sensing platform

The 3D-printed textile microfluidics fluid analytical platform is combined with remotely fabricated sensors. To showcase the compatibility and scalability of various additive manufacturing techniques, we employed screen-printing as a fabrication method for sensor integration. This technique aligns well with the platform’s aim of achieving low-cost, scalable, and efficient production. As proof of concept, we chose K+ as a target analyte, since its deviation from sweat’s physiological range (1–18.5 mM)51 is a sign of electrolyte imbalance and body fatigue, making it a valuable biomarker for non-invasive body status monitoring52.

OECTs are three electrode terminal devices with outstanding performances in biosensing53, due to the high signal amplification, stable operation in aqueous environments and low operation voltages. Their reliable screen-printing fabrication features low-cost, fast, and scalable patterning of functional inks on flat rigid or flexible surfaces, with a great spatial resolution54. Similarly printed OECTs demonstrated high performance and versatility in uric acid sensing for wound monitoring on thin flexible polyethylene terephthalate (PET) foils55. A photograph of the OECT channel and gate electrodes is presented in Fig. 6A (inset). The resulting PEDOT:PSS-based channel thickness (d) is estimated at ≈340 nm (d), with geometry (W, L) of ≈2 mm (W), and ≈0.5 mm (L); the channel/gate area nominal ratio is 0.1. The exposed channel and C-shaped gate of the planar OECT denote the sensing area of the transistor to the analyte. The sensing area here consists of 0.22 cm2, including the gate, the channel, and the gate-channel gap distance areas. With this configuration, the collected 100 μL volume is enough to cover the sensing area, creating an electrical connection between the gate and the channel, and to regularly submit the same amount of sweat to achieve a reproducible and accurate analysis. This rationale also underpins the precise capacity design of Module C.

Figure 6A depicts the screen-printed OECT after its lamination onto the textile-microfluidics top module. The sensing area is aligned with the rectangular area and the PET substrate conformably laminates it to avoid any fluid evaporation during the sensing. The three contact pads of the OECT are designed to extend outside of the fluidics module borders to facilitate an easy plug-in to the acquisition system. Additionally, the OECT lamination on top of the origami-folded microfluidics offers the option for easy removal, for example, when the microfluidics-equipped cloth requires washing or when the sensor reaches its term and must be replaced. As shown in Fig. 6B, the highly flexible, screen-printed OECT seamlessly conforms to the textile-microfluidics, following the bending curvatures. With this approach, the thin OECT shows high compatibility for wearable applications and is combined with the textile-based system providing low-cost, plug-and-play biosensing capabilities. Detailed fabrication steps are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Ion-selective membranes (ISMs) are well-known for their use in the measurement of target ions in complex electrolyte solutions56,57 and are adapted to the K+ sensor layout here. Actual wearable ion sensing is performed by measuring the open circuit potential between an ISM-modified electrode and a chloride-saturated polyvinyl butyral (PVB)-Ag/AgCl reference electrode (potentiometric sensing)58,59,60. However, this sensing approach shows two main issues over time when applied in wearables: 1) a portable solid-state Ag/AgCl-PVB is a pseudo-reference electrode that loses its stability; 2) the ISM can delaminate from the electrode, resulting in the formation of a thin layer of water, which irreversibly impairs the sensing capability61. As a solution, we propose an alternative approach that: 1) employs a transistor architecture62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69 eliminating the need for a pseudo-reference electrode; 2) uses a stable ISM sealing method.

We first functionalized the OECT channel with the ISM: any change in the ISM phase-boundary potential will cause a compensating redox reaction in PEDOT:PSS (doping/de-doping)56 resulting in variations of the transistor’s channel current70. Moreover, we introduced the ISM deposition step prior to the insulator layer’s printing (Supplementary Fig. 7). In this way, the insulator seals the ISM borders to enhance its adhesion to the substrate. Secondly, during the OECT fabrication we introduced the deposition of a NaPSS polyelectrolyte layer that yields mobile Na+ cations that de-dope PEDOT:PSS-based channels before the ISM casting, as schematized in Fig. 6C. More details on its functions are reported in Supplementary Fig. 6. The functionalized ISM-OECT shows a good current modulation with an on/off current ratio of >103 in the transfers curve reported in Fig. 6D, resulting in an order of magnitude lower than the ISM-free OECT, and it reveals the de-doped state (drain current (ID) < 9 10−7 A) at gate biases higher than 0.8 V. The ISM-free OECT shows a high transconductance value of 2.7 mS at VD = −0.4 V while the ISM-OECT experiences a transconductance decrease (~1 mS) due to the expected lower ion mobility. Nevertheless, a significant current modulation and an accurate transistor behavior is also observed from the output curve in Fig. 6E, where the ID current modulation dependency on the applied gate voltage is typical of a depletion mode OECT.

To perform the sensing, we exposed the ISM-functionalized OECT to electrolytes, from the 3D textile microfluidics, with different concentrations of the target K+ and interfering Na+ ions, while recording the real-time OECT current response. Figure 6F inset reports the real-time OECT response that shows a stepwise current decrease or increase upon the addition of increasing or decreasing K+ concentration, respectively. The sensor exhibits a current variation of ~600 μA and ~200 μA over a K+ and Na+ range of 10−4 M – 10−1 M, both from low-to-high and high-to-low molarities. The resulting calibration curves in Fig. 6F report the ID values at an equilibrium extracted from measurements on 3 different devices; the linear fitting confirms a linear response towards K+ concentrations with a sensitivity of −119 μA/dec, while the sensitivity of Na+ is significantly reduced (−29 μA/dec). It is important to mention that the response with Na+ is not completely suppressed, as expected, due to current changes associated with Cl- anions when using KCl and NaCl testing solutions. Indeed, the Ag/AgCl intrinsically senses the Cl- variation; therefore, the Ag/AgCl gate undergoes a potential (V) change due to its redox activity with Cl- anions, ultimately causing an ID variation. It is also possible to take into account the signal coming from Cl- ions and remove it from the calibration curve by simply normalizing the signal accordingly63. The OECT device sensitivity and its selectivity result in consistent, and even improved output, with respect to comparable sensors in the literature65,66,68. These results support that the OECT-integrated microfluidics shows a great potential for monitoring in real-time the concentration of K+ in the sweat range of interest.

Discussion

This study introduces SLA 3D printing as a novel approach for the precise fabrication of wearable textile-based microfluidic devices, offering a breakthrough in rapid prototyping of hybrid 3D fluid-handling systems with unparalleled design and material flexibility. By leveraging SLA technology, we achieved the first successful integration of impermeable and mechanically stretchable barriers patterned directly within textile substrates, allowing to create fluidic channels with critical resolutions down to 500 μm. Compared to other existing techniques such as wax printing and direct microchannels stitching, the SLA 3D printing is considered as an advanced technology with significant precision, efficiency and versatility. However, as it is an emerging technological approach, the industrial scalable feasibility needs to be evaluated in traditional textiles manufacturing routes. As an example, it is compatible with the large-area roll to roll integration of microfluidic devices within textiles sheets, enabling direct assembly of wearable sweat-sensing bands and establishing a foundation for scalable manufacturing via digitally programmed, self-foldable textile architectures38,39. Our approach to incorporating textiles with diverse wicking properties facilitated the development of microfluidic modules that employ capillary pressure gradients to controllably channel sweat flow from the skin to a biosensor.

To optimize this system, we applied model supported studies and simulations of textile fluid dynamics through numerical calculations allowing for prototyping of a semi-controlled textile-microfluidics platform. By employing origami-like folding techniques, we combined microfluidic modules with the fluid collection, storage, and transport capabilities in ergonomic and cloth-integrated wearable devices. Based on the analysis of these results, unprecedented continuous flow generation is not only possible but assured by the unlimited textiles surface area for constant liquid evaporation. More extended studies on the surface and wicking properties of commercial or chemically functionalized textiles will offer fine-tuning of their physical properties, which govern the textile fluidic dynamics and performance of the proposed capillary-driven microfluidics platform. Such studies will allow the design of intrinsically hybrid textiles with multifaceted wicking properties with single plane microfluidics integration, as in traditional state-of-the-art biosensing systems. While the vertical assembly of microfluidic modules may initially appear more complex than traditional planar designs, it offers a compact footprint, minimizing impermeable skin contact areas - one of the main causes of epidermal patch-device delamination and skin rash. The tradeoff between the flexibility and structural robustness in the stacked configuration can be advanced through the modular miniaturization and design optimization between resin coated and uncoated areas. In addition, textiles with the microfluidic filtering properties of the intrinsic porous materials offer a beneficial pre-sample treatment that could lead to, analytically, more specific biosensing.

The integration of an OECT-based K+ sensor within our textile microfluidic system highlights the compatibility of organic electronic biosensors with textile-based sweat collection systems. The flexible K+ sensor showed a reversible, and reproducible K+ ion sensitivity (−119 μA per decade of K+ molarity) and strong selectivity in standard solutions. As already reported71, ISM is also a robust system when tested with more complex artificial sweat solutions. Therefore, we believe in employing our sensing platform on-body for further evaluations. Its remote fabrication by screen-printing resulted in an advantageous low-cost and reliable strategy, with easy sensor removal and substitution. The planar design of the OECT device allows for its simple lamination and plugging into the data acquisition system, as well as the use of different multiplexed sensing devices for multiparametric detections.

Further development of miniaturized portable power and data transmission units will enable the development of fully wearable systems. Although some commercial electronic solutions show promise, maintaining sensor and electronic module portability continues to be a priority, particularly for washable garments. This will remain a reality unless battery-free or safe power supply solutions become largely available. Recently developed battery-free power supply, based on the perovskite solar cell, for autonomous wearable biosensors demonstrated great promise72. To incorporate such technology, textile integration and materials stability in washing require further assessment.

In summary, this work demonstrates that combining additive manufacturing, rapid prototyping, and textile fluidic property optimization provides a transformative approach to the development of advanced wearable sweat-sensing platforms. Our methodology aligns with human-oriented design principles and scalable, accessible, cost-efficient processing, paving the way for direct technological transfer toward industrialization. The presented modular approach permits us to overcome basic limitation issues that exist in traditional devices. It also accommodates the technological gap between the development of different technological building blocks in wearable electronics, such as smart textiles, embedded microfluidics, and novel biomarkers sensors. Such platforms will democratize and transform point-of-care diagnostics, enable non-invasive physiological biomarkers sampling in sweat or other biofluids, and provide more specific, personalized, follow-up, and treatment of individuals.

Methods

Textile materials

Textiles used in this work are detailed in the Supplementary Table S1 and include 100% knitted polyester, woven polyester/cotton, 100% nonwoven cellulose, non-woven 50% cellulose/50% polyester. Samples were purchased from a local creativity store. Fabrics underwent pre-washing prior to use to ensure consistent performance and remove any residues that might interfere with subsequent processes.

3D printing of textile microfluidics

The microfluidics system, consisting of 5 modules, was designed using CAD software (Fusion 360). The design comprises: a sweat collector with inlets arranged in a radial pattern (Module A), a spiral-shaped sweat reservoir (Module C), a sensing module for planar sensor integration (Module E), and two bridging modules (Modules B, D) to connect the entire system. To perform the printing, the tissue substrate is first affixed to the stage of the 3D SLA printer. Given that the printing occurs with the stage facing downward, we fixed the substrate by spraying replaceable glue (Repositionable 75 Spray Adhesive, 3M) to prevent its detachment during the printing process. Replaceable glue acts as a stable but temporary adhesion layer during the 3D printing of a flexible UV curable resin (Flexible 80A, Formlabs) and can be replaced by other physical fastening solutions (presented in Supplementary Fig. 1). Once printing is completed, the fabric is then carefully peeled away from the printer stage, and washed for 30 min in an isopropanol bath to remove the excess of non-polymerized resin. Post-curing is then carried out using UV exposure for 10 min at 60 °C. To permanently assemble the microfluidic modules in an origami-like structure, silicone pressure-sensitive adhesive squares (ARclear 93495), each measuring 2 × 2 cm and laser-patterned with a 2 mm central hole, were employed as bonding layers between the microfluidic modules. This ensures a robust yet flexible integration of the microfluidic system.

Fluid dynamic tests

To assess the fluid transport within the patterned channels, water stained with a food colorant was dispensed at the microfluidic inlets to enhance flow visualization. Fluid transport was monitored using a stereo microscope (Leica MZ10F), with snapshots captured to document and analyze the fluid dynamics throughout the system.

Capillary flow control in textile-microfluidics

A microfluidics channel is formed by gluing, in sequence, rectangular channels made from PM 1 (100% woven polyester), PM 2 (100% cellulose), PM 3 (50% cellulose, 50% polyester), on a plastic foil substrate as depicted in Fig. 4B–D. Except for the inlet and air-vent outlet, the composite textile channel is insulated with a transparent tape cover. To measure flow rates, microfluidics channels were obtained by cutting 2 mm × 2 cm stripes of each studied textile substrate; 50 μl of water was dispensed from the channel inlet and the fluid wicking video recording was used to calculate the fluid travel distance over time. Gerris open-source code was used for computational fluid dynamic (CFD) analysis using the adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) technique and Semi-Structure Quad/Octree spatial cells. The AMR technique was used with the maximum level of refinement at 4 and 5. A cell of level n generally has a resolution in each coordinate. Also, 0 and n are the refinement levels of the root cell and the recursive descendant cells, respectively. The liquid-air interface at the expanded pore areas varied by less than 10% on average, with one level increase in the superlative refinement from 4 to 5. Therefore, the grid refinement levels from 3 to 5 were used from the least to the highest phase gradient. The height function method accounted for surface adhesion effects through contact angle considerations, incorporating interfacial tension in the volume-of-fluid approach.

Zero Neumann velocity and zero Dirichlet pressure were considered as boundary conditions at both upstream and downstream ends, with gravity opposing the flow direction, ensuring capillary action as the primary driver of fluid movement.

Screen-printed ISM-OECT fabrication

The fabrication process was performed under controlled conditions (~22 °C and ~50% RH). The polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrates (Polifoil, 50 µm thick, purchased from Policrom) were preheated at 120 °C for several minutes prior to printing of the first layer. Devices were fabricated on DEK Horizon 03iX screen printing equipment. The manufacturing of the respective co-planar OECT comprised 6 sequential deposition steps. Step 1 – Ag-based electrodes (Ag 5000 paste, purchased from DuPont), to create contact pads and connections with the source and drain (S and D) electrodes. Step 2 – PEDOT:PSS-based semiconductor channels (Clevios S V4 paste, purchased from Heraeus). Step 3 – carbon-based S and D electrodes (7102 paste, purchased from DuPont). Step 4 – Ag/AgCl gate electrodes (CI-4025 paste, purchased from Engineered Materials Systems). Step 5 – drop casting of ion-selective membranes prepared as described below. Step 6 – insulating layer to prevent short-circuits and undesired electrochemical reactions (UVSF, purchased from Marabu). Each of the first four screen-printing steps was followed by thermal treatment using convection or conveyor belt ovens. The final layer applied in Step 6 was cured using ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation. The post-treatment conditions, including temperature, duration, and UV dose, were paramount to the functionality and stability of the screen-printed inks and the overall device functionality.

OECT functionalization with ISM

To monitor the potassium ions (K+) concentration in sweat, the screen-printed OECT device was functionalized by depositing an ionic selective membrane onto the screen-printed OECT’s channel. Following the printing of the PEDOT:PSS layer, a polyelectrolyte gel was prepared by dissolving Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (15 wt%) in deionized water. This solution was stirred for 2 h, after which the Polyethylene glycol, a high boiling point solvent, was added to achieve a 90:10 wt% ratio. A 3 μl gel drop was cast onto the OECT’s channel and allowed to dry at ambient temperature. The ISM cocktail was prepared by following an established protocol62. Briefly, high molecular weight PVC, diisodecyl adipate (60.5 wt.%), potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)-borate (0.5 wt.%) and potassium ionophore III (2.5 wt.%) were dissolved in 1.5 ml of THF. 1 μl of the mixture was drop cast onto the PEDOT:PSS channel and left to dry for 4 h under a fume hood. The ISM-functionalized OECT was preconditioned overnight in 10 mM of KCl solution to stabilize its sensing performance.

OECT characterization

To evaluate the functionality of the integrated OECT, the source, drain, and gate terminals were connected to a National Instruments PXIe-1062Q system. Transfer and output curves, representing the key OECT performance metrics, were recorded in a phosphate-buffered saline solution at pH 7.4.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Battat, S., Weitz, D. A. & Whitesides, G. M. An outlook on microfluidics: the promise and the challenge. Lab Chip 22, 530–536 (2022).

Cong, H. & Zhang, N. Perspectives in translating microfluidic devices from laboratory prototyping into scale-up production. Biomicrofluidics 16, 021301 (2022).

Ghaffari, R. et al. State of Sweat: Emerging Wearable Systems for Real-Time, Noninvasive Sweat Sensing and Analytics. ACS Sens. 6, 2787–2801 (2021).

Jo, S., Sung, D., Kim, S. & Koo, J. A review of wearable biosensors for sweat analysis. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 11, 117–129 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Soft, skin-interfaced microfluidic systems with integrated immunoassays, fluorometric sensors, and impedance measurement capabilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 27906–27915 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Passive sweat collection and colorimetric analysis of biomarkers relevant to kidney disorders using a soft microfluidic system. Lab Chip 19, 1545–1555 (2019).

Zhang, C., Su, Y., Liang, Y. & Lai, W. Microfluidic cloth-based analytical devices: Emerging technologies and applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 168, 112391 (2020).

Xiao, G. et al. Facile and Low-Cost Fabrication of a Thread/Paper-Based Wearable System for Simultaneous Detection of Lactate and pH in Human Sweat. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2, 265–278 (2020).

Tan, W., Powles, E., Zhang, L. & Shen, W. Go with the capillary flow. Simple thread-based microfluidics. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 334, 129670 (2021).

Cabot, J. M., Breadmore, M. C. & Paull, B. Thread based electrofluidic platform for direct metabolite analysis in complex samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 1000, 283–292 (2018).

Cabot, J. M. et al. Electrofluidic control of bioactive molecule delivery into soft tissue models based on gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels using threads and surgical sutures. Sci. Rep. 10, 7120 (2020).

Chen, L., Cabot, J. M. & Paull, B. Thread-based isotachophoresis for DNA extraction and purification from biological samples. Lab Chip 21, 2565–2573 (2021).

Piper, A., Öberg Månsson, I., Khaliliazar, S., Landin, R. & Hamedi, M. M. A disposable, wearable, flexible, stitched textile electrochemical biosensing platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 194, 113604 (2021).

Terse-Thakoor, T. et al. Thread-based multiplexed sensor patch for real-time sweat monitoring. npj Flex. Electron. 4, 18 (2020).

Farajikhah, S., Cabot, J. M., Innis, P. C., Paull, B. & Wallace, G. Life-Saving Threads: Advances in Textile-Based Analytical Devices. ACS Comb. Sci. 21, 229–240 (2019).

Owens, T. L., Leisen, J., Beckham, H. W. & Breedveld, V. Control of Microfluidic Flow in Amphiphilic Fabrics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 3796–3803 (2011).

Takamatsu, S. et al. Direct patterning of organic conductors on knitted textiles for long-term electrocardiography. Sci. Rep. 5, 15003 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Wearable microfluidics: fabric-based digital droplet flowmetry for perspiration analysis. Lab Chip 17, 926–935 (2017).

Chen, Y.-C., Shan, S.-S., Liao, Y.-T. & Liao, Y.-C. Bio-inspired fractal textile device for rapid sweat collection and monitoring. Lab Chip 21, 2524–2533 (2021).

Kwon, K. et al. An on-skin platform for wireless monitoring of flow rate, cumulative loss and temperature of sweat in real time. Nat. Electron 4, 302–312 (2021).

Shajari, S. et al. MicroSweat: A Wearable Microfluidic Patch for Noninvasive and Reliable Sweat Collection Enables Human Stress Monitoring. Adv. Sci. 10, 2204171 (2023).

Kalkal, A. et al. Recent advances in 3D printing technologies for wearable (bio)sensors. Addit. Manuf. 46, 102088 (2021).

Padash, M., Enz, C. & Carrara, S. Microfluidics by Additive Manufacturing for Wearable Biosensors: A Review. Sensors 20, 4236 (2020).

Stephenson, T. et al. Numerical modelling of the interaction between eccrine sweat and textile fabric for the development of smart clothing. IJCST 32, 761–774 (2020).

Cai, J. et al. Lucas–Washburn Equation-Based Modeling of Capillary-Driven Flow in Porous Systems. Langmuir 37, 1623–1636 (2021).

Brasier, N. & Eckstein, J. Sweat as a Source of Next-Generation Digital Biomarkers. Digital Biomark. 3, 155–165 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Sweat as a source of non-invasive biomarkers for clinical diagnosis: An overview. Talanta 273, 125865 (2024).

Grothe, T., Brockhagen, B. & Storck, J. L. Three-dimensional printing resin on different textile substrates using stereolithography: A proof of concept. J. Engineered Fibers Fabr. 15, 1558925020933440 (2020).

Formlabs. Flexible 80A Resin Technical Data Sheet (Formlabs, 2020).

Li, M. et al. A highly integrated sensing paper for wearable electrochemical sweat analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 174, 112828 (2021).

Arduini, F. et al. Origami multiple paper-based electrochemical biosensors for pesticide detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 126, 346–354 (2019).

Teengam, P. et al. Electrochemical impedance-based DNA sensor using pyrrolidinyl peptide nucleic acids for tuberculosis detection. Analytica Chim. Acta 1044, 102–109 (2018).

Jiang, H., Guo, Q., Zhang, C., Sun, Z. & Weng, X. Microfluidic origami nano-aptasensor for peanut allergen Ara h1 detection. Food Chem. 365, 130511 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Growth of gold-manganese oxide nanostructures on a 3D origami device for glucose-oxidase label based electrochemical immunosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 61, 76–82 (2014).

Qi, J. et al. The strategy of antibody-free biomarker analysis by in-situ synthesized molecularly imprinted polymers on movable valve paper-based device. Biosens. Bioelectron. 142, 111533 (2019).

Jiang, D. et al. A novel electrochemical mast cell-based paper biosensor for the rapid detection of milk allergen casein. Biosens. Bioelectron. 130, 299–306 (2019).

Fiore, L. et al. Wearable electrochemical device based on butterfly-like paper-based microfluidics for pH and Na+ monitoring in sweat. Microchimica Acta 191, 580 (2024).

Amanatides, C., Ghita, O., Evans, K. E. & Dion, G. Characterizing and predicting the self-folding behavior of weft-knit fabrics. Text. Res. J. 92, 4060–4076 (2022).

Knittel, C. E., Nicholas, D. S., Street, R. M., Schauer, C. L. & Dion, G. Self-Folding Textiles through Manipulation of Knit Stitch Architecture. Fibers 3, 575–587 (2015).

Waheed, S. et al. 3D printed microfluidic devices: enablers and barriers. Lab Chip 16, 1993–2013 (2016).

Wu, P. & Zhang, C. Low-cost, high-throughput fabrication of cloth-based microfluidic devices using a photolithographical patterning technique. Lab Chip 15, 1598–1608 (2015).

Nilghaz, A. et al. Flexible microfluidic cloth-based analytical devices using a low-cost wax patterning technique. Lab Chip 12, 209–218 (2012).

Legner, C., Kalwa, U., Patel, V., Chesmore, A. & Pandey, S. Sweat sensing in the smart wearables era: Towards integrative, multifunctional and body-compliant perspiration analysis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 296, 200–221 (2019).

Shay, T., Saha, T., Dickey, M. D. & Velev, O. D. Principles of long-term fluids handling in paper-based wearables with capillary–evaporative transport. Biomicrofluidics 14, 034112 (2020).

Yafia, M. et al. Microfluidic chain reaction of structurally programmed capillary flow events. Nature 605, 464–469 (2022).

Azizian, P., Casals-Terré, J., Ricart, J. & Cabot, J. M. Diffusion-free valve for preprogrammed immunoassay with capillary microfluidics. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 91 (2023).

Mikaelian, D. & Jones, B. Modeling of capillary-driven microfluidic networks using electric circuit analogy. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 415 (2020).

Azizian, P., Casals-Terré, J., Ricart, J. & Cabot, J. M. Capillary-driven microfluidics: impacts of 3D manufacturing on bioanalytical devices. Analyst 148, 2657–2675 (2023).

Olanrewaju, A., Beaugrand, M., Yafia, M. & Juncker, D. Capillary microfluidics in microchannels: from microfluidic networks to capillaric circuits. Lab Chip 18, 2323–2347 (2018).

Songok, J. & Toivakka, M. Enhancing Capillary-Driven Flow for Paper-Based Microfluidic Channels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 30523–30530 (2016).

Bariya, M., Nyein, H. Y. Y. & Javey, A. Wearable sweat sensors. Nat. Electron. 1, 160–171 (2018).

Cheuvront, S. N., Carter, R. I. & Sawka, M. N. Fluid Balance and Endurance Exercise Performance. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2, 202–208 (2003).

Sophocleous, M., Contat-Rodrigo, L., García-Breijo, E. & Georgiou, J. Organic Electrochemical Transistors as an Emerging Platform for Bio-Sensing Applications: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 3977–4006 (2021).

Zabihipour, M. et al. High yield manufacturing of fully screen-printed organic electrochemical transistors. npj Flex. Electron. 4, 15 (2020).

Galliani, M. et al. Flexible Printed Organic Electrochemical Transistors for the Detection of Uric Acid in Artificial Wound Exudate. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7, 2001218 (2020).

Zhai, J., Yuan, D. & Xie, X. Ionophore-based ion-selective electrodes: signal transduction and amplification from potentiometry. Sens. Diagn. 1, 213–221 (2022).

Bühlmann, P. & Chen, L. D. Ion-Selective Electrodes With Ionophore-Doped Sensing Membranes. Supramolecular Chem. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470661345.smc097 (2012).

Sempionatto, J. R. et al. Skin-worn Soft Microfluidic Potentiometric Detection System. Electroanalysis 31, 239–245 (2019).

Parrilla, M., Cánovas, R., Jeerapan, I., Andrade, F. J. & Wang, J. A Textile-Based Stretchable Multi-Ion Potentiometric Sensor. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 5, 996–1001 (2016).

Guinovart, T., Bandodkar, A. J., Windmiller, J. R., Andrade, F. J. & Wang, J. A potentiometric tattoo sensor for monitoring ammonium in sweat. Analyst 138, 7031–7038 (2013).

Parrilla, M., Cuartero, M. & Crespo, G. A. Wearable potentiometric ion sensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 110, 303–320 (2019).

Schmoltner, K., Kofler, J., Klug, A. & List-Kratochvil, E. J. W. Electrolyte-Gated Organic Field-Effect Transistor for Selective Reversible Ion Detection. Adv. Mater. 25, 6895–6899 (2013).

Melzer, K. et al. Polymeric ion-selective membrane functionalized gate-electrodes: Ion-selective response of electrolyte-gated poly (3-hexylthiophene) field-effect transistors. Org. Electron. 15, 595–601 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Ion-Selective Organic Electrochemical Transistors: Recent Progress and Challenges. Small 18, 2107413 (2022).

Sessolo, M., Rivnay, J., Bandiello, E., Malliaras, G. G. & Bolink, H. J. Ion-Selective Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Mater. 26, 4803–4807 (2014).

Coppedè, N. et al. Ion selective textile organic electrochemical transistor for wearable sweat monitoring. Org. Electron. 78, 105579 (2020).

Han, S., Yamamoto, S., Polyravas, A. G. & Malliaras, G. G. Microfabricated Ion-Selective Transistors with Fast and Super-Nernstian Response. Adv. Mater. 32, 2004790 (2020).

Pierre, A., Doris, S. E., Lujan, R. & Street, R. A. Monolithic Integration of Ion-Selective Organic Electrochemical Transistors with Thin Film Transistors on Flexible Substrates. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800577 (2019).

Meng, X. et al. Selective Ion Sensing Organic Electrochemical Transistors Suitable for Blood Analysis. Adv. Sens. Res. 3, 2300097 (2024).

Rivnay, J. et al. Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17086 (2018).

Furlan de Oliveira, R. et al. Selective Ion Sensing in Artificial Sweat Using Low-Cost Reduced Graphene Oxide Liquid-Gated Plastic Transistors. Small 18, 2201861 (2022).

Min, J. et al. An autonomous wearable biosensor powered by a perovskite solar cell. Nat. Electron. 6, 630–641 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was performed with the support of ID Fab at the Centre Microélectronique de Provence (Project funded by the European Regional Development Fund, the French state and local authorities). This research contributes to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: Health. E.I. and M.G particularly thank Francois Bernier for the experimental setting up and training on the SLA 3D printer and his valuable expertise in fast prototyping. M.G. wishes to thank P. Andersson Ersman for advice concerning the OECT manufacturing process. E.I and M.G thank Hajar Mousavi for mechanical test of 3D printed textiles. E.I. and M.G. thank Prof. Sabine Szunerits and Prof. Christian Müller for their fruitful discussions during the paper’s revisions, as part of the M.G. PhD thesis committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: M.G. and E.I. conceived the study. M.G., P.A. and E.I. developed and performed the 3D printing experiments. P.A., M.G. and J.M.C. designed and performed microfluidics studies. M.G. and A.M. designed and fabricated the OECT biosensors. All authors contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Galliani, M., Ismailova, E., Azizian, P. et al. Vertical textile microfluidics: advancing on-garment sweat sampling for real-time biosensing. npj Flex Electron 9, 38 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00416-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00416-5