Abstract

Driven by innovations in the form factor of organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays, the application scope of OLED technology now encompasses the biomedical field, in addition to its existing application domains of mobile phones, televisions, and lighting. This paper introduces an ultrathin, ultraflexible, and high-power bio-OLED patch with perfect waterproofing and an elongation of 2.04% through material and structural design. Furthermore, the OLED patch with a parallel-stacked OLED delivers a high output of 100 mW/cm2, achieves a 40% power density improvement compared to glass-based OLEDs using optimized encapsulation, and is suitable for photodynamic therapy owing to its lifetime of 183 h at an intensity of 35 mW/cm2. Since OLED patches are required for long-term stable operation in various biomedical applications, we developed an OLED patch with an outcoupling structure using a simple method. The improved OLED patch achieved a 35% increase in light extraction compared to the original OLED patch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are driven by their advantageous characteristics, such as providing self-luminous lighting, serving as surface light sources, low weights, low thicknesses, and excellent mechanical flexibility, which have led to the emergence of flexible-display technologies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The recent development of high-performance encapsulation barriers and high-efficiency OLEDs has spurred research on free-form displays, such as foldable, wearable, and stretchable devices. With the advent of next-generation displays, the OLED technology, which has been pivotal in revolutionizing traditional household electronics such as smartphones, personal computers, and televisions, has been extended to biomedical systems11,12,13,14,15,16.

The potential of OLEDs in the field of phototherapeutics has been reported. Jeon et al. realized transferable OLEDs using attachable polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as wearable photobiomodulation (PBM) patches13. The wearable PBM patch exhibited excellent wound healing effects, with fibroblast proliferation in over 58% of control and fibroblast migration in over 46% of control, providing evidence for its potential in epidermal healing. Choi et al. demonstrated the textile-based medical applications of blue OLEDs for neonatal jaundice17. Textile-based blue OLEDs have demonstrated lower voltage operation compared to traditional blue LEDs, as well as human body-burn stability, excellent operational lifetime, and therapeutic efficacy. This study confirmed the potential application of OLEDs in treating neonatal jaundice. In addition, research on OLED-based biomedical applications is being conducted; however, previous research has shown that the mechanical and chemical stabilities of OLED systems are limited because of the lack of in-depth consideration of the material and structural design, and complex planarization processes for very rough wearable textiles are required. The surface of an OLED system attached to the human body is not composed of biocompatible materials, which may cause adverse effects.

Thin-film encapsulation (TFE), achieved by alternately stacking inorganic and organic films, is a key technology for implementing highly reliable free-form displays18,19,20,21,22,23. Accordingly, TFE technology can achieve significant improvements in performance and functionality when fabricated based on material and structural designs21,24,25,26,27. Atomic layer deposition (ALD) allows the fabrication of high-density, pinhole-free inorganic barriers and thin-film structures called nanolaminates. As these ALD-based inorganic barriers have a very low water vapor transmission rate (WVTR), even with a thickness of several tens of nanometers, they have contributed significantly to improving the lifetime of organic devices28,29,30,31. However, previous inorganic barriers are highly vulnerable to mechanical stress, and their barrier properties easily degrade in hygrothermal environments25,32,33. In addition, the ALD process at temperatures above 70 °C is difficult to use for some organic devices or causes residual stress within the entire structure, requiring a lower temperature ALD barrier process34. Therefore, improving the mechanical and environmental durability of low-temperature TFEs is important for developing highly reliable OLEDs. However, facile methods and systematic analyses of the material and structural design of organic/inorganic encapsulated multibarrier structures to improve key encapsulation properties have been rarely reported.

Among the various therapeutic patch platforms, optical-based devices have been developed for applications in the biomedical fields, offering the advantages of noninvasive and safe use35. In particular, applications of flexible OLEDs are increasing in the biomedical field36,37. The key technology for such OLED applications is the development of biocompatible, ultrathin barriers and substrates. Among barrier and substrate materials, parylene-C is a biocompatible material exhibiting a high visible-light transmittance and good compatibility with OLEDs for biomedical applications1,14. Parylene-C is a low-temperature-processed material, whose thickness can be easily controlled via chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Keum et al. fabricated an OLED device, utilizing parylene-C and Al2O3/ZrO2 nanolaminate, with a total thickness of approximately 12 μm1. The OLED device exhibited no degradation in performance for over 70 d, demonstrating operational stability in water and cell culture media and unchanged current density–voltage–luminance characteristics even after 5000 bending cycles at a bending radius of 1.5 mm. However, previous studies on OLED systems utilizing parylene-C had several limitations. The WVTR values of the fabricated thin-film barriers are not provided. Additionally, only the root-mean-square roughness (Rrms) of the parylene-C film was presented, and the planarization of parylene-C surfaces with high peak-to-valley roughness (Rp-v), which is necessary to stably operate OLEDs with thicknesses of hundreds of nanometers, was not addressed. An analysis of the mechanical behavior of the barrier films and the entire structure constituting the device was not presented using high-reliability mechanical analysis methods, and systematic studies for the optimization of the mechanical and environmental durability of the barrier films were not presented.

This study presents ultrathin, ultraflexible, and high-power OLED patches with strong resistance to air, water, and chemical solvents, achieved by TFE fabricated at a low temperature of 40 °C through advanced material and structural design. These OLED patches feature a unique TFE barrier made of ALD-based inorganic nanolaminates, silane-based inorganic/organic hybrid polymer (silamer), and parylene-C, eliminating the need for a flexible substrate and resulting in a device thickness of ~10 µm. The symmetric TFE/OLED/TFE structure positions the OLEDs in a neutral plane, shielding them from mechanical stress. The OLED patches maintained their electrical performance after 32 d in ambient air, remained stable in water for two weeks, and endured mechanical stress with a bending radius of 5 mm. For biomedical applications, including photodynamic therapy (PDT), the study introduces structurally optimized red-emitting parallel-stacked OLEDs (PAOLEDs) that achieve power values exceeding 100 mW/cm² at voltages below 8 V. Our OLED patches achieve an additional 40% power density improvement compared to glass-based PAOLEDs, by suppressing total internal reflection, induced by minimizing the difference in refractive index between the encapsulation barriers. Furthermore, we developed a facile method to improve light outcoupling while maintaining the structure of the developed OLED patch, achieving a 35% increase in efficiency compared to bare OLED patches.

Results

Fabrication of ultrathin, ultraflexible, and reliable OLED-based patches

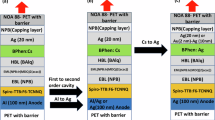

Figure 1a shows a schematic of the 10-μm-thick bio-OLED patch developed via material and structural design for effective PDT treatment. First, biocompatible barriers are used as the outermost layer of the OLED patch, and their chemical stability is evaluated. Second, functional encapsulation barriers for high-reliability OLEDs are developed by introducing ALD inorganic films and solution-processed organic films to assess environmental and mechanical robustness. These encapsulation barriers were symmetrically structured above and below the OLED device, creating a mechanically stress-free ultrathin OLED patch. For the OLED devices, a high-power PAOLED capable of long-term operation at an optical output of 35 mW/cm2 or higher for PDT applications is introduced. Two red OLEDs were vertically stacked to achieve a long-life, high-power OLED through efficient current distribution. The operational stability, mechanical robustness, and water resistance of PAOLED-based OLED patches were systematically evaluated. Figure 1b illustrates the fabrication process of the highly reliable, ultrathin, and ultraflexible PAOLED-based biopatch. The CVD-based parylene-C, widely recognized as an ecofriendly and biocompatible material, was designed to be positioned in the outermost layer of the biopatch structure. Parylene-C is an optimal material for replacing polymer substrates because its thickness can be easily controlled and it is transparent. To ensure the stable separation of parylene-C from the glass substrate, a hydrophobic film was first coated to make the glass substrate hydrophobic. Since the glass surface is generally hydrophilic, it is difficult to cleanly peel off parylene-C, but a hydrophobic glass surface enables stable peeling of parylene-C (Supplementary Fig. 1). We used 3 M™ Novec™ 1700 solution to coat a transparent film with excellent hydrophobic properties to make the glass surface hydrophobic. The coated glass surface was strongly hydrophobic with a water contact angle of 87°. Then, 3-μm-thick parylene-C was coated. The WVTR was evaluated according to the pyrolysis temperature to form an optimized parylene-C film in terms of the gas diffusion barrier. Although parylene-C is formed at low temperature below 30 °C in the deposition chamber, the powder-state dimer is evaporated by heat, and the evaporated dimer is converted into a gaseous monomer by applying high heat between 650 °C and 710 °C in a pyrolysis furnace. Temperature-dependent WVTR measurements were performed from 650 to 710 °C to identify the optimal temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). As the temperature gradually increased from 650 °C, the WVTR of parylene-C tended to decrease and showed the lowest WVTR in the range of 670–680 °C. Interestingly, the WVTR tended to increase at excessive temperatures above 690 °C. Similar to the WVTR trend, the water contact angle (WCA) of the surface of parylene-C gradually increased as the pyrolysis temperature increased up to 680 °C and then showed a tendency to decrease after 690 °C. The parylene dimer must surpass a specific barrier to cleave into monomers. Increased temperature enhances pyrolysis activity, improving the quality and water resistance of the polycondensation film. However, if the temperature exceeds a critical point, further bond breaking of the cleaved monomers may occur, degrading the film’s quality and water resistance. As a result, the parylene-C thin film exhibited the best gas barrier performance in the range of 670–680 °C, leading to its fabrication at a pyrolysis temperature of 680 °C. However, parylene-C has a very rough surface for the direct formation of OLED and is insufficient to satisfy the required barrier performance; therefore, an additional encapsulation process must be applied. Rrms and Rp-v of parylen-C were 6.75 and 70.75 nm, respectively, showing a rough surface that makes it difficult for OLEDs with only a few hundred nanometers thick, to operate stably (Fig. 2a). Therefore, a ~ 1-μm-thick silamer layer was formed by spin-coating for effective surface planarization (Rpv changed from 70.75 nm to 2.5 nm). Although ALD provides excellent step coverage performance, it is not effective in improving surface roughness. Even after ALD coating on parylene-C, its surface roughness still remained at the same level (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then, a 60-nm-thick Al2O3/TiO2 nanolaminate (ATN) barrier was deposited using ALD to achieve the WVTR of 10−6 g/m2/d required for OLEDs. ALD is reportedly the most effective deposition technique for fabricating high-performance gas barriers. To achieve a WVTR of ~10−6 g/m2/d, the silamer/ATN structure was deposited twice on the parylene-C thin film. As a result, Fig. 2a shows that the surface of the parylene-C/silamer/nanolaminate/silamer/nanolaminate (PSNSN) structure exhibits sufficient planar roughness. Furthermore, the PSPSN structure achieved a visible light transmittance (λ = 400–720 nm) of 84.63% and a transmittance (λ = 600–660 nm) of 85.43% (Supplementary Fig. 4). These values are comparable to or higher than the transmittances of polymer substrates such as PET, polyethylene naphthalate, and polyimide. High-power OLEDs are required to replace inorganic LEDs and lasers in terms of their optical output for various biomedical applications. The red-emitting PAOLEDs exhibited a radiant emittance of more than 100 mW/cm² at low voltages (<8 V). After forming the PAOLED, the top encapsulation process was performed in reverse order of the bottom encapsulation process to create a symmetrical patch structure based on the PAOLED. Finally, when the OLED patch of the PSNSN/PAOLED/NSNSP structure was stably separated from the glass, a highly efficient, reliable, and flexible bio-OLED patch was obtained.

a Changes in surface roughness due to the addition of each encapsulation barrier. b AFM images of parylene-C barriers exposed to 85 °C/85% RH for different durations. c AFM images of parylene-C barriers immersed in water for different durations. d AFM images of parylene-C barriers immersed in an acidic solution for different durations. e AFM images of parylene-C barriers immersed in developer solution for different durations. f Optical transmittance of NSNSP structure according to exposure time in 85 °C/85% RH. g Optical transmittance of NSNSP structure as a function of time immersed in water.

Structural and material design for developing a mechanically and environmentally robust encapsulation barrier

To develop the OLED patch with TFT and solar cell devices, the barrier film and PAOLED, encased by parylene-C films, must be protected from chemical solutions like strong acids, developers, and water used in the lithography process for electrode and insulator patterning, to validate its use as an encapsulation barrier in the semiconductor and display industries. Therefore, the chemical stability of the outermost parylene-C barrier is vital for the bio-OLED patch’s reliability. The fabrication process of the parylene-C films was optimized to achieve optimal barrier properties regarding pyrolysis temperature. The environmental degradation of the thin films was confirmed by observing changes in their surface roughness. First, parylene-C did not show any change in surface roughness even after being exposed to 85 °C/85% RH and water for 30 h (Fig. 2b). This indirectly confirms that it stably maintains its properties without undergoing chemical reactions in water (Fig. 2c). Next, the wet etching of the thin film was measured at 10-min intervals for 30 min in acidic solutions (nitric and sulfuric acid), considering the etching time (Fig. 2d). Surprisingly, parylene-C did not show any change in the surface roughness, even in strongly acidic solutions, when considering both the roughness deviation and surface image. In addition, the surface of parylene-C showed the same Rrms and Rp-v values as the initial values, even after exposure for 10 min in the immersion test in the commonly used AZ 300 MIF developer (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, a comparison of the optical transmittance and atomic force microscopy (AFM) results confirmed that the NSNSP structure exposed to a harsh environment of 85 °C/85% RH and water for 30 h exhibited its same initial transmittance (Fig. 2f, g). Therefore, through immersion tests in various solutions, we verified that the chemical stability of parylene-C is excellent, making it an effective material for protecting the internal encapsulation barrier and OLED structures.

We developed a 40 °C low-temperature ALD barrier process for encapsulating organic devices that are easily thermally degraded, such as perovskites and OLEDs. Conventional OLEDs, made of organic materials with a higher glass transition temperature (Tg) compared to perovskite solar cells, can undergo encapsulation at 70 °C25,38. Conversely, high-efficiency perovskite solar cells are highly heat-sensitive due to the use of doped spiro-OMeTAD (Tg ~50 °C) as a hole transfer layer39. Each constituent barrier film was fabricated at temperatures below 40 °C to facilitate the future development of a self-powered OLED patch integrating solar cells and OLEDs. For a low-temperature ALD inorganic barrier with high impermeability, excellent mechanical properties, and superior environmental stability, the WVTR and flexibility were optimized through material and structural design. Among various ALD-based oxides, Al2O3 is a common insulator in electronic devices but degrades under high temperatures and humidity25. Furthermore, lower temperatures increased defects and porosity in Al2O3 due to low precursor reactivity, resulting in lower density40. To enhance the low-temperature ALD barrier, a nanolaminate structure with alternating thin layers of Al2O3 and TiO2 (denoted as ATN previously) was introduced. In this study, the fabricated ATNs are formed by repeatedly stacking Al2O3 and TiO2 sublayers of the same thickness multiple times, and the sublayer thickness value is indicated after the ATN name to distinguish various types of ATNs. Figure 3a shows the WVTR values of Al2O3, TiO2, and ATN3 barrier at a fixed thickness of 30 nm. The WVTR of ATN3 was (9.02 ± 2.74) × 10−4 g/m2/d, which is much lower than the respective WVTRs of Al2O3 ((7.12 ± 1.35) × 10−2 g/m2/d) and TiO2 ((5.76 ± 1.29) × 10−3 g/m2/d). In the nanolaminate structure, the improvement in barrier performance is attributed to defect-decoupling effects that suppress the growth of defects and bonding at the multi-interface between Al2O3/TiO240.

a Comparison of WVTR of Al2O3, TiO2, and ATN3. b Changes in WVTR before and after bending of various barriers. c Residual stress and calculated membrane force of each encapsulation barrier. d Changes in membrane force due to addition of an encapsulation barrier. e Comparison of WVTR of NSNSP and ASASP. f Changes in WVTR with exposure time under 85°C/85% RH of ATN3 and NSNSP. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

The structural advantages of the ATN regarding WVTR were confirmed, leading to its adoption as an ALD barrier. ATN3 showed improved barrier performance as thickness increased, but the rate of increase gradually slowed down. This trend is likely due to the higher probability of film cracks caused by increased membrane force, which is the product of the measured stress values and thickness of each barrier41. Given the high tensile stress of the ALD film, cracks can occur even at low thicknesses, and this likelihood increases with thickness. Figure 3b compares the WVTR of various types of 60-nm-thick ATN films before and after 0.42% bending. As the thickness of the sublayers constituting the ATN decreased, not only did the WVTR of the ATN decrease, but the increase in WVTR after bending decreased in terms of mechanical flexibility. The ATN10, ATN3, and ATN1 barriers composed of a sufficient number of Al2O3/TiO2 pairs achieved a WVTR of the order of 10−4 g/m2/d and showed a similar level of WVTR increase after bending. In contrast, ATN30 had a WVTR of the order of 10−3 to 10−2 g/m2/d and showed a WVTR increase of more than 10 times after bending. Therefore, the ATN3 barrier, which exhibited excellent robustness to mechanical stress while recording the lowest average WVTR, was used as the ALD barrier.

The ALD nanolaminate process can separate pinhole-type defects throughout the film’s thickness due to the newly formed interfaces between Al2O3 and TiO2 sublayers. This process results in a defect-sealing effect, where pinhole defects are covered by another sublayer, reducing defect severity and offering advantages under tensile loading. Additionally, inhibiting the growth of pinhole defects may reduce stress concentration at the defect edges. According to the Griffith model which assumes the presence of numerous elliptical defects in real materials, the maximum stress at the defect edge is applied.

The radius of an elliptical defect’s corner can be as small as the interatomic spacing, leading to high stress concentration at the defect edge. During ALD nanolaminate process, natural defects may arise at the Al2O3 and TiO2 layer interface due to inadequate reactions at low temperatures. Consequently, the radius of curvature (ρ) at the corners of the elliptic defect can significantly increase as circular-type defects, rather than elliptical ones, form, blunting defect edges and substantially lowering the stress intensity factor. In an ATN structure, assuming a similar ρ value, reducing the sublayer thickness results in shorter pinhole defects, thereby enhancing mechanical robustness.

We sought to reduce membrane force as an additional strategy to enhance the mechanical robustness of bio-OLED patches. The residual stress of each encapsulation barrier was measured via the wafer curvature method to calculate membrane force (Fig. 3c). The organic barriers, parylene-C and silamer thin films, recorded compressive stresses of −1.34 and −10.78 MPa, respectively, and the ALD-based ATN3 barrier recorded a tensile stress of 230.98 MPa. The ATN3 barrier was formed with an equal ratio of Al2O3 (301.1 MPa) and TiO2 (200.7 MPa); thus, the measured stress showed an intermediate value. The membrane force value also showed a similar trend. Figure 3d shows the changes in the total membrane force with the formation of each film. Although the ALD barrier itself exhibits a high positive membrane force and is susceptible to stress, the resulting overall membrane force of the PSPSN structure was 21.37 GPaÅ by counteracting the negative membrane force of parylene-C and silamers. Thus, the developed encapsulation barriers are highly impermeable and mechanically reliable based on the structural design for stress engineering. Figure 3e shows the WVTR of the NSNSP and ASASP structures. The synergistic combination of ATN, silamer, and parylene-C based on optimization achieved a WVTR of ~10−6, which is the barrier required for OLEDs, whereas the ASASP with poor gas barrier properties showed a WVTR of only 10−4g/m2/d due to the poor gas barrier properties of Al2O3. The environmental stability of the encapsulation barrier is a key performance factor for OLED reliability. This is important for the long-term use of organic electronic devices in various environments where the barrier function is not lost, even when exposed to harsh environments. Figure 3f shows the WVTR changes of ATN3 and NSNSP with respect to exposure time in a harsh environment of 85 °C /85% RH. The ATN3 improved the poor environmental stability of Al2O3 by the chemical bonding of Al–O–Ti at the interface of Al2O3 and TiO2. Supporting data for the formation of the aluminate phase of ATN barrier was presented using XPS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5). It seems most likely that the core-level shifts resulted from the formation of an aluminate phase, where Al tended to gain an electron and Ti tended to donate an electron, owing to the difference in the electronegativities between Al (1.61) and Ti (1.54)42. The ATN3 showed an 18.3-fold increase in WVTR after 30 h of exposure to a harsh environment, whereas the NSNSP showed a 7.68-fold increase in WVTR after 30 h of exposure, confirming that it had considerable environmental stability because of the organic capping layers. This is because parylene-C protects the SNSN structure by preventing direct exposure to a harsh environment based on its considerable environmental stability. Second, the silamer additionally forms Al–O–Si through interfacial bonding with the ATN, which imparts strong moisture resistance. This further delays the degradation of the ATN. Thus, we designed an encapsulation multibarrier with excellent mechanical and environmental stability by combining functional polymers with the optimized ATN. Analyzing the mechanical behavior of versatile encapsulation barriers and actual devices is essential for predicting their performance and optimizing structural design. We employed a tensile test on water (TOW) to ensure a reliable mechanical evaluation by measuring the stress–strain curve of nanoscale thin films on water with high surface tension43,44,45,46. This method reliably assesses the pure mechanical properties of thin films with several tens of nanometers. A thin film was formed on a copper-coated wafer and patterned into a dogbone shape using a femtosecond laser (Fig. 4a). The Cu/barrier sample was then floated on water and transferred to a copper etchant ((NH4)2S2O8). After the bottom copper film was completely etched, the copper etchant was rapidly diluted with an additional supply of deionized water. Finally, the freestanding barrier film was pulled in the tensile direction on the water surface using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-coated aluminum grips, which enabled the gripping of the specimen via van der Waals adhesion between the PDMS and the specimen. In the TOW method, the elongation is measured up to the point of fracture when crack branching occurs. First, the mechanical properties of 3-μm-thick parylene-C films and 1-μm-thick silamer films used as organic barriers were evaluated by TOW. The elongation values of parylene-C and silamer films were 32.27% and 6.25%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). Although parylene-C is highly ductile, the elastic range showing linear behavior is very short, up to 2.7% strain, and plastic deformation behavior is observed in most of the strain ranges. On the other hand, the silamer layer exhibited linear behavior up to failure at 6.25% strain, despite its elongation being only one-fifth that of parylene-C. Second, the TOW method was applied to various ALD barriers (Fig. 4b). For a stable and reliable evaluation, the thickness of all barrier films was fixed at 90 nm. As a result, ATN barriers exhibit significantly superior mechanical properties compared with single-layer films. Notably, the 40 °C Al2O3 film not only exhibited poor gas barrier performance but also exhibited extreme brittleness with an elongation of only 0.053%. Although TiO2 showed a relatively moderate elongation of 0.31%, its barrier and mechanical properties still did not meet the requirements for a flexible barrier. Interestingly, the ATN exhibited a variety of mechanical behaviors depending on the thickness of its sublayers. ATN1, ATN3, ATN5, ATN10, and ATN15 achieved excellent elongation, exceeding 0.45%, consistent with the results of the bending test shown in Fig. 3b. By contrast, ATN10 exhibited the highest elongation of 0.52%, indicating superior mechanical properties. ATN3 was identified as the most balanced barrier film when considering both barrier performance and mechanical characteristics. Additionally, the environmental stabilities of ATN10, ATN3, and ATN1 were evaluated using freestanding tensile tests before and after exposure to 60 °C/90% RH (Fig. 4c). Hygrothermal degradation occurs mainly because of an increase in hydroxide(–OH) groups due to exposure to hygrothermal environments. This higher OH concentration, along with the increased porosity caused by hygrothermal degradation, resulted in stress concentration, which negatively affected both the elongation and tensile strength. Notably, we found that the impact of hygrothermal degradation on elongation can be significantly reduced using nanolaminate system, especially in the case of the ATN3 structure, which showed the smallest reduction level of approximately 11.5% for elongation. This reduction level aligns closely with the results of WVTR measurements, indicating that the ATN3 barrier is an effective strategy for highly reliable low-temperature-processed organic devices. The ATN3 barrier is an effective strategy for achieving highly reliable low-temperature-processed organic devices. Figure 4e shows the TOW results verifying the capping effect of the silamer layer in the environment of 85 °C/85% RH. To demonstrate the protective effect, 70 °C Al2O3 films, which are easily degraded in harsh environments and have sufficient elongation, were used. The silamer-coated Al2O3 sample (A/S) recorded an elongation of 0.53 ± 0.03%, which is slightly higher than the elongation of Al2O3 (0.46%), even though it contained silamer with high elongation. However, the aged A/S structure exposed to the harsh environment of 85 °C/85% RH for 10 h achieved an elongation of 0.48 ± 0.05%, which was ~10% lower than that observed before exposure, confirming the excellent environmental stability of A/S. To enhance the reliability of our analysis, we also evaluated the (aged A)/S structure where the Al2O3 thin film underwent environmental aging before the silamer layer was formed, given that the high-elongation silamer barrier showed almost no reduction in elongation under these conditions. The (aged A)/S structure achieved an elongation of 0.24 ± 0.04%, which confirmed that the elongation of the entire barrier structure significantly decreases when the Al2O3 is environmentally degraded. This protective effect is due to the formation of strong Al–O–Si bonds created during the silicification process at the interface between Al2O3 and the silamer layer34.

a Sample preparation and transfer process for freestanding tensile on water. b Elongation of various ATN barriers. c Changes in average elongation before and after exposure under 60 °C /90% RH for ATN10, ATN3, and ATN1 barriers. d Comparison of elongation of A/S, aged A/S, and (aged A)/S samples to verify improvement in environmental stability by silamer. e Maximum elongation values of various encapsulation multi-barrier structures. f Stress-strain curves of PSNSN/OLED/NSNS and OLED patch structures. g A schematic explaining the mechanical behavior of SNSNS and SNS structures after post-crack onset strain. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3) or as averages of three results.

While the mechanical properties of single organic and inorganic layers are well-documented, there is limited research on multilayer structures43,45,47. Assessing the mechanical behavior of organic/inorganic multilayer barriers or encapsulated organic devices is difficult due to the constraints of traditional analysis methods. Consequently, to improve the mechanical elongation of these multilayer barrier structures, we experimentally verified and suggested a straightforward design rule based on mechanical properties. Figure 4e shows the maximum elongation of the multibarrier structures fabricated using the organic barrier silamer and the inorganic barrier ATNs. Surprisingly, despite incorporation of two layers of silamer, which exhibited elongation exceeding 6%, the SNSN structure showed an elongation of only 0.52%, similar to that of the NSN structure. In other words, the elongations of the SNSN and NSN structures were only slightly higher than that of the ATN, indicating that these barrier structures were not effective in improving the mechanical properties. By contrast, the SNS and SNSNS structures achieved remarkable elongations of 1.79% and 2.74%, respectively. Notably, the SNSNS structure exhibited an elongation 6.37 times greater than that of multibarrier structures, such as SNSN and NSN. These remarkable mechanical properties result from the fabrication of a symmetric multibarrier structure with an outermost organic layer in which brittle thin films are surrounded by ductile organic layers. The structural design rules for fabricating high-elongation multilayered structures can be summarized as follows. The first design rule is to ensure that the multilayer structure is symmetrical overall, with ductile organic layers as the outermost layers (e.g., SNSN, NSN vs. SNS). Encapsulating brittle layers above and below with organic ones above and below is essential for dispersing strain energy from fractures in both directions. The second design rule involves positioning organic layers as the outermost layers in a symmetric structure and increasing the number of alternating inorganic/organic pairs (e.g., SNS vs. SNSNS) to enhance elongation. Therefore, the intrinsic mechanical properties of a bio-OLED patch based on these design rules were evaluated. Figure 4f shows the stress–strain curves of PSNSN/OLED/NSNS and PSNSN/OLED/NSNSP (our symmetrical OLED patch structure). Remarkably, the asymmetric PSNSN/OLED/NSNS structure exhibited an elongation of 0.69%, whereas the fully symmetric OLED patch structure exhibited an elongation of 2.03%. We propose a mechanism for the major improvements observed in tensile tests on multi-barrier encapsulation and bio-OLED patches and verify the mechanism using finite element analysis (FEA) simulations. SNSNS with higher crack density exhibits more delayed fracture resistance than SNS structures with lower crack density, as the strain energy generated by cracking of the brittle film is effectively distributed among the many cracks that have already been formed (Fig. 4g). In other words, this is because more brittle layers result in higher crack density after the crack-onset strain, reducing stress at crack tips and preventing through-thickness crack propagation. To compare the crack density between multilayer structures, the elastic modulus of ATN calculated in the elastic region of SNSNS and SNS before and after applying 1% tensile strain can be compared. (Supplementary Fig. 7). A detailed explanation of the tensile experiments conducted to indirectly compare the crack density of the multibarrier structures is provided in the Supporting Information. These mechanisms underscore the significant impact of crack density and stress management on the mechanical durability of multibarrier systems. To further verify the proposed mechanism, FEA simulations were performed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a, the findings reveal that with an increase in crack density, the stress near the ATN3 crack tip reduces. This stress reduction consequently diminishes the stress within the silamer layer, effectively inhibiting the development of through-thickness cracks. Moreover, Supplementary Fig. 8b illustrates that the stress intensity factor (SIF), which defines the stress field near the crack tip, also decreases as crack density rises. Interestingly, the NSN structures demonstrated higher SIF values than the SNS structures, aligning with their reduced elongation. Additionally, it was observed that the Young’s modulus of ATN3 declined as crack density increased, further supporting the proposed mechanism. These FEA outcomes affirm that higher crack density alleviates stress concentration and promotes increased elongation by impeding through-thickness crack propagation, thus corroborating the enhanced mechanical performance of the SNS structure as previously discussed.

Therefore, the developed encapsulation barrier was fabricated to have ultrahigh gas barrier characteristics and excellent environmental stability by combining each functional barrier based on material design, and the ultrathin and symmetrical OLED patch structure was fabricated to be ultraflexible based on structural design.

Performance and reliability of the fabricated bio-OLED patches

High-power and high-efficiency OLEDs are essential for phototherapeutics and other optical healthcare applications. OLED patches need to be lightweight, low operational temperature, operational reliability, durable, and exhibit high brightness at low voltages. Bio-OLEDs, when attached to the human body, require an output that is dozens of times stronger than OLEDs used in traditional displays. Therefore, implementing a low-voltage, high-efficiency Bio-OLED patch is essential to achieve operational reliability and low temperature at high output12,48. We propose a high-power PAOLEDs to achieve both low voltage and high brightness. The reliability of the fabrication process (Fig. 1b) was validated by comparing the electrical characteristics of the glass-based reference OLED and the OLED patches after delamination (Fig. 5a). The OLED patch, formed by perfectly flattening rough parylene-C, showed identical electrical characteristics to the glass reference PAOLED, confirming no physical damage occurred during detachment from the guide glass, attributed to a symmetrical structure that positions the OLED on the neutral axis while also designing an ultrathin thickness of less than 10 μm. Another important feature of our OLED patch is that it exhibited significantly higher average luminance across the entire voltage range compared to the glass reference PAOLED. Generally, when considering efficiency from a display perspective, performance may be evaluated based on criteria like luminance (cd/m²) and cd/A, which reflect output intensity and current efficiency from the human visual perception standpoint. Therefore, instead of comparing performance using the traditional display metrics of cd/m² and cd/A, it is necessary to compare using mW/cm² and mW/A49. This trend is naturally also confirmed in electroluminescence spectra, current efficiency, and power density (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Fig. 9). Notably, the OLED patch exhibited approximately 40% and 50% improvements in current efficiency and power density, respectively, compared to the glass-based reference OLED. To investigate the light extraction efficiency (LEE) of glass and PSNSN, finite-difference time- domain (FDTD) simulations were performed using commercial Lumerical FDTD (Ansys, Inc.). The refractive index values of each encapsulation barrier are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. Light emitted from the EML layer of an OLED undergoes complex interference phenomena as it passes through various layers within the device including encapsulation layers. To induce resonance at specific wavelengths, the thicknesses of layers through which light passes are carefully designed. However, the electrical characteristics of the OLED limit the degree of freedom in this design. Therefore, we utilized encapsulation layers outside the electrode, which are external to the OLED’s electrical driving region, to achieve desired optical properties. In a NSNSP structure, by adjusting the thickness of the high-index ATN layer (n ~ 1.95), resonance can be induced at specific wavelengths to enhance constructive interference. Through FDTD simulations, we determined the optimal thickness of the ATN layer to achieve constructive interference in the 620-640 nm wavelength range. To replicate the red-emitting OLED source, the mean electromagnetic field intensity of incoherent, isotropic dipole emitters is calculated using electromagnetic fields generated by single dipole along the x, y and z axes. The simulations revealed that the glass surface facilitates light reflection at the glass/air interface, whereas the NSNSP exhibits enhanced light extraction by inducing light resonance as reflected light interferes with each other when passing from a high-refractive-index ATN (n ~ 1.95) to a low-refractive-index silamer (n ~ 1.50), which occurs through constructive interference (Fig. 5d). As a result, the 60-nm-thick ATN not only serves as excellent gas diffusion barrier but also enhances the LEE of red wavelengths through the interference effect.

a Electrical-optical characteristics, b current efficiency, and c power density of glass reference PAOLED and OLED patches. d FDTD simulation to compare the light extraction efficiency of NSNSP and glass. e Operational lifetimes of various OLED devices under driving conditions of 35 mW/cm2. f Shelf-lifetime over time in air at a luminance corresponding to a power density of 35 mW/cm2. g Shelf-lifetime of OLED patches over time in air. Shelf-lifetime of OLED patches according to (g) curvature radius and h bending cycle. i Luminance variation of an OLED patch over time when stored in water. (j) photographs demonstrating the excellent mechanical robustness and water resistance of the OLED patch. Data are presented as averages of three results.

The operational lifetime of OLED patches is important for long-term reuse rather than disposable use. The operational lifetime of the OLED patches was evaluated by constant current driving at a fixed current density, which can output a power density of 35 mW/cm2. The LT50, which is the time over which the initial luminance declines to 50% in air, was measured for the evaluated samples. As reference devices, single OLEDs with indium tin oxide (ITO) electrodes and microcavity structures showed 13 h and 29 h, respectively. This is because they are under considerable electrical stress to sustain a high output of 35 mW/cm2. The LT50 of an unencapsulated PAOLED was ≈89 h despite continuous exposure to moisture and oxygen, whereas that of our OLED patch was ≈183 h (Fig. 5e). The results show that PAOLED significantly reduces the electrical stress applied on each OLED by distributing the current equally to two devices. Therefore, in addition to the high output aspect, PAOLED shows to be an excellent strategy for OLED patches in terms of operational reliability. To verify the lifetime and mechanical and chemical stability of the OLED patch, shelf-life tests were performed in various environments. The OLED patch maintained a luminance of 35 mW/cm2 for 32 d at room temperature, confirming that the encapsulation barriers functioned effectively. In contrast, the PSNSN/PAOLED without top encapsulation showed continuous luminance degradation over time, and numerous dark spots were observed in the cell image after 17 d (inset of Fig. 5f). To verify the mechanical stability of the OLED patch, luminance changes were assessed based on bending radius and cycles (Fig. 5g, h). The neutral-axis-engineered ultrathin OLED patch displayed no luminance degradation after 100 bends with a 0.5 mm radius. Additionally, it exhibited excellent fatigue resistance, enduring 10,000 bends with a 1 mm radius. Thus, the OLED patches demonstrated outstanding mechanical durability due to their material and structural design. Finally, to confirm the feasibility of a patch that is washable and can be used underwater, luminance changes were evaluated based on immersion time in water. The highly water-resistant encapsulation barrier completely protected the OLED from water, and no signs of degradation were observed even after 14 d of exposure. In contrast, the PAOLED encapsulated with only the NS structure showed stable operation for 2 d but then showed an exponential decrease in luminance owing to moisture permeability. The 3-μm-thick parylene-C layer exhibits excellent hydrophobicity and thus plays an important role in the waterproofness of the encapsulation barrier. Figure 5j shows photographs demonstrating the excellent mechanical robustness and water resistance of the OLED patch. The OLED patch operated stably both when perfectly folded on 500 μm-thick glass (r ≈ 250 μm) and when rolled around a 3-mm diameter fiber, demonstrating an extreme form factor and confirming its potential for future wearable and stretchable devices requiring larger strains. Furthermore, extreme water resistance was confirmed by stable operation even after two weeks of storage in water. In addition, heat generation in OLEDs affects the lifespan and usability of patches, which should thus be operated at <42 °C for attachment to or insertion into the human body to minimize low-temperature burns. Therefore, we measured the surface temperature of the OLED patch at a high power of 35 mW/cm2, viz., the minimum power required for various PDT applications, and detected a drive temperature of 53.1 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11). This low temperature that could cause burns was mitigated by using an attachable 50-μm-thick graphite sheet as an effective heat sink. After attaching the heat dissipation sheet on the top encapsulation, the drive temperature is reduced to 39.6 °C by widely spreading heat through the graphite sheet and saturated at less than 40 °C such that the OLED patch can safely be used in applications involving body attachment and transplantation. Since the thickness of the graphite sheet is about 5 times that of the OLED patch, the flexibility of the OLED patch may be reduced when combined with the graphite sheet. However, our patch achieved elongation of 2%, and in experiments for actual biomedical applications, it was effectively fixed by the transparent Tegaderm film when fabricating the OLED patch platform, so that the mechanical stress applied to the OLED patch could be alleviated. The photographs of the OLED patch with the graphite sheet attached and the bio-medical patch platform are shown in the Supplementary Fig. 12. Since an adhesive graphite sheet is attached to the top of the OLED patch and the bottom encapsulation is attached to the skin, it can be used for biomedical applications. And, as long as strong pressure is not applied to the OLED patch during the process of attaching the graphite sheet, the electrical characteristics of OLED patches with graphite sheets were not degraded (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Furthermore, the proportion of singlet oxygen produced when light was irradiated on the photosensitizer using an OLED patch was measured using a single oxygen sensor green (SOSG). The SOSG test demonstrated that singlet oxygen reacts to produce fluorescent endoperoxide, which exhibits absorption at 504 nm and emission at 525 nm12. Results indicated that the singlet oxygen generation rate increases proportionally with both the power and duration of OLED patch irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 14). Specifically, when exposed to light intensities of 35 and 45 mW/cm² for 35 min, the singlet oxygen generation rate increased by 3.56-fold and 4.31-fold, respectively, compared to the control group. These findings confirm that the OLED patch effectively generates singlet oxygen at an intensity of 35 mW/cm². The bio-OLED patch developed in this study demonstrated outstanding performance, exhibiting the low voltage (<8 V), high output (>100 mW/cm²), and efficiency (>300 mW/A) among the near-infrared OLEDs applied in biomedical fields reported to date12,50.

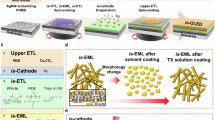

Fabrication of a highly efficient bio-OLED patch

In order to use bio-OLED patches for diseases such as cancer, a light output of more than 100 mW/cm2 is required. Although the developed bio-OLED patch showed a radiant emittance of 70 mW/cm2 at 7 V, additional outcoupling technique must be applied to stably achieve 100 mW/cm2. Therefore, we fabricated an ultra-high-output OLED patch by easily incorporating light extraction technology during the fabrication of the bio-OLED patch. Figure 6a shows the fabrication process of a highly efficient bio-OLED patch. This process is identical to that shown in Fig. 1b except that the substrate for forming the initial parylene-C is different. In other words, the proposed process technology is to form various nano- and micro-structures on the parylene-C surface using a CVD technique for parylene-C coating. Parylene-C is formed on the prepared epoxy mold, and a 2-dyad silamer/ATN process is performed for effective planarization. Two layers of spin-coated silamers effectively planarized the parylene-C surface as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. After fabricating the OLED and the top encapsulation layer, the bottom parylene-C surface of the peeled OLED patch transferred the roughness of the epoxy mold as it was, and it was confirmed through AFM measurement that micro-dimple arrays were generated. The parylene-C single layer on which micro-dimple arrays were generated showed 40% optical haze (Fig. 6b). It shows similar diffuse transmittance across the entire visible light wavelength, making it effective for use in all red, green, and blue OLED devices. As a result, the bio-OLED patch with dimple array pattern achieved a 30% increase in light extraction by effectively suppressing total reflection caused by the difference in refractive index at the parylene-C/air interface by the micro-dimple pattern (Fig. 6c)51,52. Furthermore, the external quantum efficiency (EQE) was calculated based on the EL spectrum, luminance, and current density, assuming Lambertian emission. The OLED patch with the micro-dimple array exhibited an EQE of 20.38% at a current density of 1 mA/cm², compared to 13.58% for the glass reference OLED (EQE of bio-OLED patch: 20.38%; EQE of glass reference OLED: 13.58%). To investigate the light extraction effect of the parylene-C with micro-dimple array, FDTD simulation was conducted. Although the actual system comprises a 2D square lattice of microlenses, simulating a 1D array in 2D space is sufficient to analyze the improvement in extraction efficiency resulting from reduced total internal reflection. In the simulation, the dimple structure was modeled as a concave hemiellipse. The lateral diameter of the hemiellipse was set to 80% of the period, based on the AFM measurements of the micro-dimple array, while the vertical radius was adjusted to match the peak depth of the dimple depression. To replicate the OLED source, incoherent, isotropic dipole emitters are modeled by averaging the results of three simulations, each using a single dipole along the x, y, and z axes. Light extraction simulations were performed at the peak wavelengths of red, green, and blue OLEDs (629 nm, 535 nm, and 460 nm, respectively). To investigate the effects of the dimple array’s period and depth, simulations were conducted for depths ranging from 1 to 10 μm and periods ranging from 1 to 20 μm. The enhancement (%) is defined as the light extraction of the dimpled structure divided by that of the reference (no pattern), minus 100%. Figure 6d presents color maps representing the enhancement of LEE for red, green, and blue OLEDs, respectively, as functions of the dimple array period (y-axis) and depth (x-axis). For the fabricated red OLED-based patch with a period of approximately 13 μm and a depth of 7 μm, an enhancement close to the maximum is shown. Depths greater than 7 μm showed no significant improvement in LEE. A depth of 7 μm was chosen as it provides both high extraction efficiency and a favorable aspect ratio, forming a nearly spherical shape (radius ~7 μm) that is advantageous for mold fabrication. To examine this more closely, the field profiles of the dimple structure were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 16). For comparison, a reference structure without any pattern was also simulated. The source was positioned at coordinates (0, -15.5). The results indicate that light, which would otherwise be trapped due to total internal reflection (TIR), escapes as a result of the dimple array.

a Fabrication process of a highly efficient bio-OLED patch with an external scattering structure. b Optical properties of parylene-C single layer on which micro-dimple arrays. c Current efficiency of OLED patch with micro-dimple arrays and OLED patches. d Color maps representing the enhancement in light extraction efficiency for red, green, and blue OLEDs using FDTD simulation.

Discussion

In conclusion, we developed ultrathin, ultraflexible, high-power OLED patches for biomedical applications. The OLED patch, mechanically robust, featured a high-performance encapsulation barrier symmetrically surrounding the OLED, using vertically stacked red OLEDs. An electrically parallel-stacked PAOLED achieved a high-power output of >100 mW/cm² at a low voltage of 8 V. For reliability, biocompatible parylene-C was applied to the bottom and top of the patch to prevent side effects from human body attachment and insertion, ensuring its usability as a bio-OLED patch. Despite parylene-C’s poor gas barrier performance, it exhibits high resistance in harsh environments (e.g., 85 °C/85% RH, water, acid, developers) and functions as a light-extraction layer to enhance the OLED patch light output. However, because the surface of parylene-C is quite rough, surface planarization is required for a stable OLED operation. The surface of parylene-C was smoothed using a silamer, a functional polymer. The silamer layer also enhanced the environmental stability of the ALD barrier through the chemical bonding of Al–O–Si at the interface. To create a low-temperature encapsulation barrier suitable for heat-sensitive perovskite and organic devices, as well as OLEDs, the primary gas barrier, an ALD barrier, was produced at a process temperature below 40 °C, along with the organic barrier.To develop a high-performance ALD barrier, nanolaminate formed by alternating multilayers of Al2O3 and TiO2 sublayers was introduced, and the ATN3 barrier was developed by optimizing the thickness of the sublayer in terms of WVTR and elongation. The ATN3 barrier exhibited a WVTR of 5.34 × 10−4 g/m2/d and an elongation of 0.46%, which are remarkable improvements compared to the 40° Al2O3 barrier of 0.03 × 10−2 g/m2/d and 0.05%, respectively, based on structural optimization. Furthermore, the ATN3 barrier exhibited excellent environmental stability, maintaining an elongation of 0.41% even under 85 °C/85% RH, and it was experimentally verified that the silamer containing SiO2 was effective in preventing environmental degradation through interfacial bonding with the ALD barrier. Therefore, the PSNSN structure fabricated by combining each functional barrier achieved a WVTR on the order of 10−6 g/m2/d and secured significant mechanical stability by achieving a membrane force of 21.37 GPaÅ through stress engineering. We optimized encapsulation barriers and patch structures, proposing a robust design rule for high-strength barriers using an innovative tensile analysis. The OLED patch designed per this rule demonstrated elongation exceeding 2%, marking the first measurement of an encapsulated OLED device’s elongation. This indicates that the elongation limit of a brittle film can be exceeded through structural optimization. For a reliable OLED patch, systematic analysis of mechanical and environmental stability is crucial. PAOLED-based OLED patch achieved not only a high output of 100 mW/cm², but also an additional 50% improvement in power density compared to a glass substrate by alternately stacking high- and low-refractive-index layers within the encapsulation structure to induce a micro-cavity effect. From a device reliability standpoint, performance was maintained even under extreme bending, demonstrating excellent mechanical stability and fatigue life due to a very low membrane force. Moreover, the OLED patch proved to be perfectly waterproof, passing an immersion test in water for over two weeks. To significantly expand the biomedical applicability of OLED patches, a simple process was developed to exhibit improved light output while maintaining the existing optimized OLED patch structure. CVD-based parylene-C was formed on the epoxy mold on which the microlens array was formed, and the roughness of the mold was copied as it was onto the parylene surface. In addition, the OLED patch could be easily removed from the mold by utilizing the poor adhesion between the epoxy mold and parylene-C. Due to the parylene-C with such a microstructure, the improved OLED patch showed a 30% increase in light extraction, demonstrating that light extraction can be easily improved. Developed through material and structural optimization based on systematic analysis, the high-power OLED patch is lightweight, ultrathin, ultraflexible, and environmentally reliable, indicating significant potential for biomedical applications. In the future, we aim to develop an ultrahigh-power OLED fiber by winding a robust, ultrathin, and transparent OLED onto a fiber to create an insertable OLED system. These OLED fibers are expected to exhibit excellent performance in PDT applications that require high powers of more than 100 mW/cm2 for long periods of time, such as cancer treatment.

Methods

Fabrication of highly impermeable, mechanically robust, and environmentally stable TFE

The TFE process has been optimized from a material perspective so that it can be manufactured at temperatures below 40 °C. Parylene-C was deposited by using a parylene coater (OBT-PC300, OBANG TECHNOLOGY). The parylene-C powder was vaporized at 80–175 °C and the gaseous parylene dimer was pyrolyzed into a monomer at 690 °C. Subsequently, parylene-C in the form of a polymer was coated onto the surface of the substrate in the deposition chamber at room temperature. The silamer layer is synthesized by the sol–gel method using Si:glycidoxy-propyl trimethoxysilane and tetraethyl orthosilicate, then coated via spin-coating and cured in a vacuum chamber at 40 °C. AT nanolaminate was deposited at 40 °C using thermal ALD. Al2O3 was used as a precursor by cooling trimethylaluminum to 10 °C, and TiO2 was used as a precursor by heating tetrakis(dimethylamino)titanium to 60 °C. H2O is commonly used as the reactant for reactions with precursors. The deposition process was performed at a base pressure of 3.1 × 10−1 Torr, and Ts1, Tp1, Ts2, and Tp2 of Al2O3 were 0.2, 10, 0.2, and 10 s, and that of TiO2 was 0.5, 10, 0.2, and 10 s, showing growth rates of 1.03 Å/cycle and 0.84 Å/cycle, respectively. where Ts1 and Ts2 are the exposure times of the precursor and reactant, respectively, and Tp1 and Tp2 are the purge times for the exporting precursor and reactant, respectively.

Fabrication and characterization of PAOLED devices

First, the ITO (150 nm) as the anode was grown by radio frequency magnetron sputtering at room temperature film on the bottom encapsulation. And then, the remaining thin films that make up the PAOLED device were coated using thermal evaporation in a vacuum environment of 10−6 Torr. The first OLED was constructed with the following layer sequence: molybdenum trioxide (MoO3, 5 nm) as the hole injection layer (HIL), NPB (67.5 nm) as the hole transport layer (HTL), bis(10-hydroxybenzo[h]quinolinato)-beryllium:tris[1-phenyl-isoquinoline-C2,N]iridium(III) (bebq2:Ir(piq3), 8 wt%, 70 nm) as the emission layer (EML), and cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 1 nm) as the electron injection layer (EIL). A common cathode (Ag, 30 nm) was then deposited to allow parallel electrical deposition with the second OLED. The second OLED was formed by the sequential deposition of Cs2CO3 (1 nm) as the EIL, bebq2:Ir(piq3) (8 wt%, 70 nm) as the EML, NPB (67.5 nm) as the HTL, MoO3 (5 nm) as the HIL, and aluminum (Al, 100 nm) as the anode. The J–V–L characteristics of the PAOLED were measured using a source meter (Keithley 2400, Keithley Inc.) and a spectroradiometer (CS-2000, Konica Minolta Inc., Japan). The operational lifetimes of the PAOLED were measured under constant-current operation in air (Polaronix M9000S, McScience Inc., Korea).

Preparation of the epoxy mold with micro-dimple array

First, the photoresist (PR) was coated on the glass at a spin speed of 1000 rpm for 1 min, then baked on a hot plate at 100 °C for 3 min. The sample was exposed to an exposure device with a wavelength of 465 nm for 2 min using a mask, and developed for 1 min to remove the PR at the edges. Next, the photomask with the microlens pattern was brought into full contact with the PR, and exposure was carried out for 2 min, followed by development for 30 s. The PR reflow process was performed in an oven at 170 °C for 10 min. Next, PDMS Sylgard 184 was poured onto the glass substrate with the microlens structure and cured in an oven at 120 °C for 1 h. Finally, after curing, the PDMS mold was removed, filled with epoxy on PDMS mold, and cured in an oven at 120 °C for 1 h to create the final epoxy mold.

Electrical Ca test

The WVTRs of encapsulation barriers were measured using an electrically Ca corrosion test in an environment of 30 °C/90% RH. The Ca sensor was fabricated by sequentially depositing patterned Al (100 nm) and Ca (250 nm) films onto a glass substrate via thermal evaporation. The barrier-coated polymer film was attached to a Ca sensor cell using a UV-curable sealant (XNR5570, Japan). At least three calcium sensors were fabricated for each type of barrier sample to increase the reliability of the WVTR values calculated using the following equation53:

Here, n represents the stoichiometric coefficient (set as 2 for water); M(H2O) and M(Ca) denote the molar masses of water and Ca, respectively; δ stands for the density of Ca; ρ represents its resistivity; and l and b denote the length and width of the active Ca layer, respectively.

Freestanding tensile testing on water

First, dogbone-shaped samples were fabricated from a barrier film on a Si/SiO2/Cu substrate using a femtosecond laser (Pharos, L2K Co., Korea). The laser was operated at a 10-mW pulse power and 100-kHz repetition rate to carefully ablate both the multilayer and sacrificial Cu layer beneath, ensuring the complete detachment of the dogbone-shaped sample from the Si/SiO2 substrate. The specimens measured 17.2 mm in total length, with grip sections of 5 mm in both length and width, and gauge lengths and widths of 3 mm and 0.8 mm, respectively. Second, a water surface with high surface tension (73 mN m−1) and low viscosity (1.002 mPa s−1) was used as a support for tensile testing in a freestanding configuration. Precise measurements were performed using a high-resolution load cell (model LTS-50GA, KYOWA, Japan) and a linear actuator (model M-111.1DG, Physik Instrumente, Germany), both mounted on an anti-vibration table and aligned symmetrically with a freestanding multilayer thin film. The tensile properties were measured by recording the load values with a load cell, whereas the in-situ strain was tracked using a digital image correlation system with a charge-coupled device camera. The multilayer thin film was held in place using PDMS-coated Si grips, and the tensile tests were conducted at a controlled strain rate of approximately 5.8 × 10−5 s−1. Testing was performed under standardized conditions of 25 °C/20% RH. From a batch of 10–20 fabricated specimens, three to five samples were tested to produce stress–strain curves that were highly reproducible, indicating consistent mechanical behavior among the samples.

Characterization of encapsulation barriers

The surface roughness of the encapsulation barriers formed on the glass substrates was measured using AFM (Park Systems, XE-100, Korea). Cross-sectional SEM images of the OLED patches were obtained using a FIB-SEM (Helios G4 CX, FEI, USA).

Singlet oxygen sensor green test

The singlet oxygen generation rate of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) as a photosensitizer was measured using an SOSG (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc., USA) kit. Since 5-ALA, a precursor which is used commonly for PDT therapy, is converted to PpIX, which acts as a photosensitizer of actual photodynamic therapy in the body, test was conducted using PpIX rather than 5-ALA in the singlet oxygen measurement. The photosensitizer (40 μM) and SOSG in methanol were mixed and exposed to the OLED patch depending on duration and power. The fluorescence intensity of the activated SOSG was immediately detected using a spectrophotometer (excitation/emission: 504/525 nm). The singlet oxygen generation ratio was calculated as “x-%” in relation to the fluorescence intensity at “0” min irradiation.

Optical properties of encapsulation barriers

The spectral transmittance of the encapsulation barrier was measured using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (UV 2600i, SHIMADZU, Japan).

FDTD simulation

FDTD simulation was conducted using commercial Lumerical FDTD (Ansys, Inc.). The simulation utilized perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions to minimize reflections from boundaries. A frequency-domain profile monitor was used to obtain the electric field distribution around the device and its surroundings. The refractive indices of Al2O3, TiO2, parylene-C, and silamer were measured using a spectroscopic ellipsometer (SFX-200, KLA-Tencor, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Keum, C. et al. A substrateless, flexible, and water-resistant organic light-emitting diode. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020).

White, M. S. et al. Ultrathin, highly flexible and stretchable PLEDs. Nat. Photonics 7, 811–816 (2013).

Kim, S. H. et al. A compact polymer–inorganic hybrid gas barrier nanolayer for flexible organic light-emitting diode displays. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 1–6 (2022).

Choi, S. et al. Highly flexible and efficient fabric-based organic light-emitting devices for clothing-shaped wearable displays. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8 (2017).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Design of highly water resistant, impermeable, and flexible thin- film encapsulation based on inorganic / organic hybrid layers. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 11, 3251–3261 (2019).

Kang, K. S. et al. Enhancing flexibility and reliability in wearable OLEDs through silbione-blended hybrimer-based encapsulation. npj Flex. Electron. 9, 49 (2025).

Choi, D. K. et al. Highly efficient, heat dissipating, stretchable organic light-emitting diodes based on a MoO3/Au/MoO3 electrode with encapsulation. Nat. Commun 12, 2864 (2021).

Hu, S. et al. Exciton control enables high-performance colloidal quantum well light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, 21428 (2024).

Liu, B. et al. An ideal host-guest system to accomplish high-performance greenish yellow and hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes. Org. Electron 27, 29–34 (2015).

Luo, D., Yang, Y., Huang, L., Liu, B. & Zhao, Y. High-performance hybrid white organic light-emitting diodes exploiting blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent dyes. Dyes Pigments 147, 83–89 (2017).

Jeon, Y. et al. Sandwich-structure transferable free-form OLEDs for wearable and disposable skin wound photomedicine. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 114 (2019).

Jeon, Y. et al. Parallel-stacked flexible organic light-emitting diodes for wearable photodynamic therapeutics and color-tunable optoelectronics. ACS Nano 14, 15688–15699 (2020).

Jeon, Y. et al. A wearable photobiomodulation patch using a flexible red-wavelength OLED and its in vitro differential cell proliferation effects. Adv. Mater. Technol. 3, 1700391 (2018).

Sim, J. H. et al. OLED catheters for inner-body phototherapy: A case of type 2 diabetes mellitus improved via duodenal photobiomodulation. Sci. Adv. 9, 1–13 (2023).

Kim, Y. W. et al. Wearable blue OLED patch using natural antibacterial phytochemicals for non-antibiotic treatment against staphylococcus aureus. Nano Res. https://doi.org/10.26599/NR.2025.94907409 (2025).

Shin, Y. J. et al. Stretchable fabric organic light-emitting diodes based on transferable laser pattern for wearable photodiagnostic applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42765-025-00532-x (2025).

Choi, S. et al. Wearable photomedicine for neonatal jaundice treatment using blue organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs): Toward textile-based wearable phototherapeutics. Adv. Sci. 9, 1–10 (2022).

Seo, S.-W., Chae, H., Joon Seo, S., Kyoon Chung, H. & Min Cho, S. Extremely bendable thin-film encapsulation of organic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 161908 (2013).

Kang, K. S., Jeong, S. Y., Jeong, E. G. & Choi, K. C. Reliable high temperature, high humidity flexible thin film encapsulation using Al2O3/MgO nanolaminates for flexible OLEDs. Nano Res 13, 2716–2725 (2020).

Jeon, Y., Lee, H., Kim, H. & Kwon, J. H. A review of various attempts on multi-functional encapsulation technologies for the reliability of OLEDs. Micromachines (Basel) 13, 1478 (2022).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Functional design of dielectric-metal-dielectric-based thin-film encapsulation with heat transfer and flexibility for flexible displays. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 9, 27062–27072 (2017).

Kwon, J. H., Jeon, Y., Choi, S., Kim, H. & Choi, K. C. Synergistic gas diffusion multilayer architecture based on the nanolaminate and inorganic-organic hybrid organic layer. J. Inf. Disp. 0, 1–8 (2018).

Nam, M. et al. Highly reliable and stretchable OLEDs based on facile patterning method: Toward stretchable organic optoelectronic devices. npj Flexible Electr. 8, 17 (2024).

Kwon, J. H., Jeon, Y. & Choi, K. C. Robust transparent and conductive gas di ff usion multibarrier based on Mg- and Al-doped ZnO as indium tin oxide-free electrodes for organic electronics. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 10, 32387–32396 (2018).

Lee, S. et al. Study of mechanical degradation of freestanding ALD Al2O3 by a hygrothermal environment and a facile protective method for environmentally stable Al2O3: toward highly reliable wearable OLEDs. Mater. Horiz. 10, 4488–4500 (2023).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Low-temperature and corrosion-resistant gas diffusion multi-barrier with UV and heat rejection capability—a strategy to ensure reliability of organic electronics. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 11, 16776–16784 (2019).

Lee, S. W. et al. Highly reliable and ultra-flexible wearable OLEDs enabled by environmentally and mechanically robust hybrid multibarrier encapsulation layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2411802, 1–16 (2024).

Park, S.-H. K. et al. Ultrathin film encapsulation of an OLED by ALD. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 8, H21 (2005).

Hoffmann, L. et al. Gas diffusion barriers prepared by spatial atmospheric pressure plasma enhanced ALD. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 4171–4176 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. A low-temperature thin-film encapsulation for enhanced stability of a highly efficient perovskite solar cell. Adv. Energy Mater. 1701928, 1–8 (2017).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Low-temperature fabrication of robust, transparent, and flexible thin film transistor with nano-laminated insulator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 15829–15840 (2018).

Jen, S.-H., Bertrand, J.A., & George, S.M. Critical tensile and compressive strains for cracking of Al2O3 films grown by atomic layer deposition. J. Appl Phys. 109, 084305 (2011).

Rückerl, A. et al. Characterization and prevention of humidity related degradation of atomic layer deposited Al2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 025306 (2017).

Jeon, Y. et al. Highly efficient and reliable organic light–emitting diodes enabled by a multifunctional hazy substrate for extreme environments. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2310268, 1–15 (2023).

Yun, S. H. & Kwok, S. J. J. Light in diagnosis, therapy and surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0008 (2017).

Cho, E. H. et al. Wearable and wavelength-tunable near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes for biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c12016 (2023).

Park, Y., Choi, H. R., Shin, J. W., Huh, C. H. & Choi, K. C. A wearable OLED medical device for enhanced cutaneous wound healing and patient comfort: revolutionizing dermatology. J. Inf. Disp. 25, 151–156 (2024).

Kwon, J. H. et al. Functional design of highly robust and flexible thin-film encapsulation composed of quasi-perfect sublayers for transparent, flexible displays. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 9, 43983–43992 (2017).

Nakka, L., Cheng, Y., Aberle, A. G. & Lin, F. Analytical review of spiro-OMeTAD hole transport materials: Paths toward stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Sustainability Res. 3, 2200045 (2022).

Oh, S. J. et al. Nanolaminate-induced mechanically and environmentally robust Al2O3/TiO2 thin film encapsulation by low-temperature atomic layer deposition: Toward Flexible and wearable OLEDs. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2400381, 1–12 (2024).

Behrendt, A. et al. Stress management in thin-film gas-permeation barriers. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 8, 4056–4061 (2016).

Kim, L. H. et al. Al2O3/TiO2 nanolaminate thin film encapsulation for organic thin film transistors via plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 6, 6731–6738 (2014).

Kim, J.-H. et al. Tensile testing of ultra-thin films on water surface. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–6 (2013).

Oh, S. J., Ma, B. S., Yang, C. & Kim, T. S. Intrinsic mechanical properties of free-standing SiNxthin films depending on PECVD conditions for controlling residual stress. ACS Appl Electron Mater. 4, 3980–3987 (2022).

Oh, S. J., Kwon, J. H., Lee, S., Choi, K. C. & Kim, T. S. Unveiling the annealing-dependent mechanical properties of freestanding indium tin oxide thin films. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 16650–16659 (2021).

Oh, S. J., Lee, S., Choi, K. C., Kwon, J. H. & Kim, T. S. Elucidating the effect of Ag interlayer formation on the intrinsic mechanical properties of free-standing ITO/Ag/ITO thin films. J. Mater. Chem. C. Mater. 11, 7262–7271 (2023).

Koo, J. et al. Evaluating mechanical properties of 100nm-thick atomic layer deposited Al2O3 as a free-standing film. Scr. Mater. 187, 256–261 (2020).

Woo, Y. et al. Wearable quantum dots organic light-emitting diodes patch for high-power near infra-red photomedicene with real-time wavelength control. Chem. Eng. J. 499, 156121 (2024).

Murawski, C. & Gather, M. C. Emerging biomedical applications of organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100269 (2021).

Cho, Y. et al. Wavelength-tunable textile-based organic light-emitting diode for multifunctional wearable photomedical applications and display with cool white to warm white light. ACS Photonics 11, 5418–5429 (2024).

Gather, M. C. & Reineke, S. Recent advances in light outcoupling from white organic light-emitting diodes. J. Photonics Energy 5, 057607 (2015).

Shinar, R. & Shinar, J. Light extraction from organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs). JPhys Photonics 4, 0–29 (2022).

Paetzold, R., Winnacker, a, Henseler, D., Cesari, V. & Heuser, K. Permeation rate measurements by electrical analysis of calcium corrosion. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 5147 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (20018379, Development of high-reliability light-emitting fiber-based woven wearable displays) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea). In addition, this work was supported by the Technology development Program (RS-2024-00469790) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.K., Y.J. and T.-Y.L. contributed equally to this work. J.H.K. mainly conducted the experiments and analyses, and prepared the manuscript. Y.J. performed device fabrication and characterization. T.-Y.L. interpreted the theoretical and experimental results. Y.H.S. and H.L. analyzed the experimental data and organized the manuscript contents. D.-H.B. fabricated an epoxy mold substrate for the experiment. S.-W.L. and T.-S.K. analyzed the mechanical behavior of thin films. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, J.H., Jeon, Y., Lee, TY. et al. Highly efficient, reliable, and ultraflexible bio-organic light-emitting diode patch. npj Flex Electron 9, 55 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00428-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00428-1