Abstract

Antibiotic administration is the mainstay for treating bacterial infections, but multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria jeopardize its effectiveness. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) offers a promising strategy with less risk of inducing resistance, yet the lack of a suitable wearable light source limits its widespread adoption. Here, we design flexible quantum dot light-emitting diodes (F-QLEDs) for effective aPDT treatment of MDR bacteria. By simultaneous optical, thermal, and reliability management, we achieved F-QLEDs with emission spectrum matching the photosensitizer absorption, physiologically safe surface temperature (<41 °C), enhanced operating lifetime (7.5X), and ambient shelf life > 1 month. Subsequently, aPDT testing demonstrated a ~ 9-log reduction of Staphylococcus aureus and ~2-3 log reduction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa compared to controls. Additionally, testing with different photosensitizers confirmed F-QLED versatility for targeted aPDT. These results showcase the potent antimicrobial efficacy of F-QLEDs and their potential as wearable optical platforms for point-of-care treatment of MDR infections and broader photomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread use and misuse of antibiotics have propelled the development of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria to a critical juncture, posing a formidable threat to public health and imposing a substantial economic burden on society1,2. In the United States alone, the staggering toll of MDR infections is stark, with over 2.8 million people afflicted annually and a tragic toll of 35,000 lives lost, accompanied by an economic burden reaching upwards of $55 to $70 billion annually3. Multidrug resistance in bacteria tends to manifest through different mechanisms, including reduced drug internalization, overexpressing drug efflux pumps, sequestration of entered drugs, modifying drug targets, and biofilm formation, whereby clusters of bacteria stick to each other, producing an extracellular matrix that could prevent the penetration and uptake of antibiotics. There is an urgent unmet need for an alternative or adjunctive therapy that can target the MDR bacteria itself and/or help antibiotics synergistically to overcome the MDR mechanisms for enhanced treatment efficacy.

Antimicrobial PDT (aPDT) has recently emerged as a promising strategy to treat MDR bacterial infections by the synergistic effect of light, oxygen, and drug molecules called photosensitizers (PSs)4, illustrated in Fig. 1B. During aPDT, the PSs are excited by light at a specific wavelength in the presence of oxygen, leading to the production of reactive molecular species (RMS). RMS can kill bacteria by oxidatively damaging their biomolecules, especially those constituting the external structures of bacteria, such as the cell membrane and cell wall, which are well-accepted as the major targets of aPDT. Moreover, RMS can impair the protein synthesis process, induce DNA mutation, and activate pro-cell-death factors when they penetrate the internal structures of bacteria. This multitargeted mechanism enables aPDT to inactivate bacterial strains regardless of their MDR levels or mechanisms, while also presenting a lower risk of inducing resistance compared to antibiotics. Notably, aPDT has been shown to disrupt a wide range of antibiotic resistance mechanisms, effectively “priming” bacteria for subsequent antibiotic treatment. These mechanisms include biofilm formation, efflux pump overexpression, production of antibiotic-degrading enzymes, and the reduced permeability of bacterial outer membranes5. Due to these attributes, aPDT is particularly well-suited for treating refractory chronic infections, such as diabetic foot infections, wound infections, and burn infections. These conditions are common causes of preventable disabilities and impose a significant health and economic burden on society.

A Engineering process of the flexible QLEDs (F-QLEDs), entailing optical management via emission tuning, and thermal/barrier management via material engineering. B Schematic representation of the aPDT mechanism, illustrating the interaction of red light, oxygen, and photosensitizers. C Biological evaluation of F-QLED-based aPDT efficacy in killing MDR bacteria, including S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli.

Despite its promise, the clinical adoption of aPDT for managing MDR infections has encountered formidable challenges, chiefly attributable to limitations inherent in existing medical light source systems, predominantly lasers or LEDs6. Lasers and LEDs are inherently hot, rigid point-specific light sources. To ensure effective, homogeneous delivery of light to the treatment site, complicated cooling elements, additional optical fibers, and diffusing optics are necessary, which make these light source systems bulky and expensive, usually costing >$10,000. As an example, two laser light sources were guided through numerous leaky optical fibers that were woven into a light-emitting fabric for flexible, homogeneous light delivery for aPDT7. Integrating such systems into routine clinical practice of chronic infection management poses logistical and financial hurdles, compounded by patient discomfort and safety concerns associated with high temperatures and high-intensity light regimens. Taken together, these light source limitations have constrained the accessibility of aPDT and its potential as an alternative or adjunctive strategy to standard antibiotic therapy for refractory MDR infections.

A light source that can simultaneously offer tunable emission wavelengths with a narrow spectral bandwidth, sufficient optical power density (OPD) while maintaining low surface temperature, a scalable and homogeneous emission area, and wearable form factors holds significant potential to improve the accessibility and efficacy of phototherapy, particularly aPDT. The rationale for these design attributes is multi-faceted. First, narrowband emission with wavelength tunability facilitates compatibility with a variety of PSs, enabling high overlap between the device emission and the PS absorption spectra. This enhances photon utilization efficiency, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy at specific excitation wavelengths while minimizing heat generation due to off-target photon absorption, which is important for mitigating patient discomfort and tissue damage. Second, achieving high OPD while maintaining a low device surface temperature ensures adequate excitation energy for effective PS activation, patient safety and reliable device operation, respectively. Third, a light source with a scalable, homogeneous emission area ensures uniform irradiance across treatment sites of varying sizes, enabling accurate light dosing for better reproducibility and eliminating the need for repeated repositioning over large targets. Finally, wearable characteristics—such as flexibility, lightweight design, and minimal thickness—are essential for ergonomic integration with the human body, allowing conformal contact with anatomically curved or irregular surfaces, such as skin or intraoral tissues. This makes the device particularly well-suited for practical “at-home” or ambulatory treatment applications.

To meet these ideal characteristics, we aimed to develop a flexible quantum dot light-emitting diode (F-QLED) platform tailored for aPDT applications against MDR infections (see Fig. 1). QLEDs are multilayered light-source devices similar to organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) whose main difference from OLEDs is the use of colloidal quantum dots (QDs) as the emissive materials8. QDs, semiconductor nanocrystals that have gained widespread recognition, were the subject of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their revolutionary impact9. These nanocrystals possess radii smaller than the Bohr radius, and their optoelectronic properties vary with size due to the quantum confinement of charge carriers. Their properties include tunable emission wavelength, high photoluminescence quantum yield, high color purity, solution processability, and the ability to function in photoluminescence (PL) or electroluminescence (EL) modes, depending on the type of excitation9,10. Due to these unique properties, QDs are helping the next-generation display technologies achieve a wide color gamut and high energy efficiency simultaneously11,12,13,14. To date, QD materials have been widely commercialized via PL-based display technologies13; these are the quantum dot enhancement film (QDEF) and the quantum dot color-conversion (QDCC) layer technologies, with Samsung’s QD-OLED TV being the first QDCC-based display product. QD EL-based devices, originally named QLEDs, were once perceived as the ultimate display technology, offering printable, ultra-thin, and flexible form factor features in addition to superior color and efficiency. Despite decades of dedicated efforts from academia and industry to push the performance limits of QLEDs8,15,16,17, achieving reliable full-color QLED displays remains a significant challenge18,19, largely due to difficulties in developing efficient and reliable blue QLEDs20. On the other hand, QLEDs also show great potential in other areas beyond display, such as lighting for healthcare, potentially marking a first market entry for QLEDs. Our group pioneered the research and development of QLEDs as photomedical light sources11,14,21,22, showcasing ideal characteristics for the widespread adoption of phototherapies.

F-QLEDs possess features and properties that can overcome the main limitations of current LED- and laser-based phototherapies. In particular, the flexibility and emission tunability of F-QLEDs allow them to target various infection sites and bacteria, with their light and thin structure enabling portable use for both ambulatory and “at home” applications, thus extending the reach of aPDT. Additionally, F-QLEDs can be fabricated using techniques similar to flexible OLEDs commonly used in the display industry. However, while the operating lifetime of F-QLEDs required for a phototherapy session—ranging from several minutes to a few hours—is less stringent than that for display technologies, aPDT necessitates other crucial features. These include high overlap between the emission spectrum of the light source and the absorption spectrum of the PS, and OPD typically an order of magnitude higher than that required for display applications. Tuning the peak emission of the QLED to match the PS absorption peak, combined with a narrow emission bandwidth, significantly enhances spectral overlap, thereby enhancing photon utilization and improving the phototherapy efficacy at the desired excitation wavelengths. Moreover, a high spectral overlap minimizes thermal photon losses, which in turn avoids overheating of the target tissue. Meanwhile, achieving a high OPD for simultaneous deep tissue penetration and sufficient PS excitation typically requires driving the QLED at high current densities. This, in turn, generates excess Joule heat that polymeric substrates and encapsulation layers in F-QLEDs cannot effectively dissipate, leading to elevated device temperatures. Prolonged operation under such thermal stress accelerates morphological degradation of the organic layers in QLEDs, substantially reducing device lifespan or causing failure. Additionally, surface temperatures ≥ 42–45 °C23 may cause user discomfort or superficial burns. Therefore, achieving a high OPD while maintaining low temperature and stable operation is crucial for the effective, safe, and reliable implementation of aPDT. It is important to note that healthcare applications prioritize radiometric over photometric parameters, as light delivery is quantified based on energy rather than human visual sensitivity. Consequently, in this study, the OPD was adopted as the primary figure of merit for evaluating QLED performance, rather than luminance.

Herein, we first evaluated and confirmed rigid, on-glass QLEDs as efficient light sources for aPDT, demonstrating their ability to effectively activate PSs and generate sufficient RMS to combat MDR bacteria. Then, building on this confirmation, we focused on three major technical developments of F-QLEDs: 1) optical management by precise emission tuning for targeted aPDT and efficient photon use, 2) thermal management for safe and reliable operation at high OPD and current density, and 3) barrier management for enhanced operational stability and reliability in ambient conditions. For thermal and barrier management, an experimental study was conducted to select the best option among suitable commercial materials. Specifically, the selection was made by evaluating the performance of conductive substrates and adhesive barrier films in terms of the device heat dissipation and encapsulation. In particular, the top barrier film of the device was evaluated as a dual-function film: heat sink and encapsulation material. In the same order, this multilateral approach effectively resulted in F-QLEDs with (1) emission spectra largely overlapping the absorption of two classical PSs, including 96% for methylene blue (MB) and 69% for protoporphyrin IX (PpIX), (2) physiologically safe surface temperature (<41 °C) up to a high OPD of ~18 mW cm−2 (212 mA cm−2), and (3) enhanced operating lifetime—7.5 times that of the F-QLEDs using flexible transparent barriers (FTBs) for top encapsulation—and stable shelf life in ambient air (>1 month), making it well-suited for real-world applications. These developments significantly improved the performance and suitability of F-QLEDs for targeted antimicrobial applications (Fig. 1A).

Lastly, the aPDT efficacy of these F-QLEDs was evaluated through carefully designed in vitro studies (Fig. 1C), using wavelength-tuned F-QLEDs combined with the two classical PSs, i.e., MB and PpIX, to assess the killing of multiple representative MDR bacteria (e.g., S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli). Notably, significant bacterial killing (>90%) was achieved with F-QLED-based aPDT, compared to control groups receiving no treatment, PS alone, or F-QLED illumination alone. With further technical advancements and pre-clinical studies, our F-QLEDs offer a practical solution to the limitations of conventional light sources, presenting a promising avenue for advancing aPDT as an effective intervention against MDR infections.

Results

Suitability of QLEDs as Efficient Light Sources for aPDT

Before developing F-QLEDs for aPDT, we evaluated the suitability of QLEDs as light sources for aPDT with rigid prototypes. We aimed to determine whether QLEDs could effectively activate the most common PS and induce sufficient RMS to eradicate bacterial pathogens. Therefore, we fabricated a rigid on-glass QLED tailored to the excitation requirements of methylene blue (MB) (see Fig. 2A). As can be seen in Figure S1A (see Supplementary information), the QLED exhibited a peak emission wavelength of 651 nm closely matching the 660 nm peak absorption wavelength of MB.

A Rigid QLED device with illumination pixels used for aPDT. B, C In-vitro aPDT efficacy of QLEDs against MDR S. aureus (gram-positive) and E. coli (gram-negative) showing significant bacterial reduction with photosensitizer (MB) and QLED light combination (MB + QLED). Asterisks (*) indicate cases where bacterial survival was undetectable. The mean of each treatment group was compared to the control group using a t-test. Statistical significance is shown as follows: NS (not significant), * (P < 0.05), and ** (P < 0.01). D Schematic of an ex-vivo pig skin infection model with a skin burn inoculated with MDR bacteria, including MDR S. aureus (gram-positive) and P. aeruginosa (gram-negative). E Bioluminescence imaging results demonstrating the killing efficacy of QLED-based aPDT in ex-vivo models, comparing untreated, MB-only, light-only, and MB + light treatment groups for MDR S. aureus and P. aeruginosa strains.

Then, the irradiated optical power from the QLED as a function of voltage was measured to ensure its compatibility with clinical applications, as shown in Figure S1B. Additionally, we conducted stability tests, demonstrating that the irradiance decay of the QLED remained minimal (within 0.1 mW) over a 1-hour period, suitable conditions for the performed aPDT sessions (Figure S1C). Encouraged by these favorable characteristics of the QLED, we proceeded to investigate its efficacy in aPDT using an in vitro infection model. The results indicated that under clinically safe conditions (MB concentration of 100 μM, QLED voltage of 4.5 V, and 1-h illumination time), the QLED achieved approximately 9-log and 5-log reductions in the viability of representative MDR gram-positive (S. aureus) and gram-negative (E. coli) pathogens, respectively (Fig. 2B, C).

Furthermore, the aPDT efficacy of the rigid on-glass QLED was validated using a pig skin burn infection model (Fig. 2D). The bioluminescence emitted by MDR bacteria, indicative of bacterial load at the infection location, was markedly diminished following aPDT treatment with the QLED (Fig. 2E), affirming its potential as an effective antimicrobial intervention.

Development and Engineering of Flexible QLEDs for aPDT Application

Following the demonstration of the potent efficacy of QLEDs in aPDT against MDR pathogens using rigid on-glass QLEDs, we advanced to the next phase: developing F-QLEDs using a multilateral approach. Such development aims to enable the use of QLEDs for aPDT treatment of infection sites with diverse shapes and locations. Therefore, a reengineering process is essential to replace the rigid substrates and encapsulation covers with flexible materials, while maintaining safe/reliable device operation and aPDT efficacy comparable to that of on-glass QLEDs.

As described in the introduction, to enable the practical application of F-QLEDs in real-world settings, the following key characteristics must be met in addition to the wearable form factors: (1) High overlap of the device emission spectrum with the absorption spectrum of the photosensitizer; (2) Low-temperature device operation at high optical power density (OPD); (3) Sufficient device shelf life and operational lifetime to ensure reliability in ambient conditions and stable performance during aPDT sessions, respectively. To achieve these characteristics, two main engineering steps were implemented, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Optical device management was employed to address the requirement in (1), while the characteristics in (2) and (3) were simultaneously addressed through a comprehensive experimental study. The results of the optical management and the experimental study corresponding to the thermal/barrier management are detailed in the following sections.

A Controlled tunning of device emission leading to F-QLEDs with EL peaks centered at 629 and 651 nm for targeted aPDT. The EL spectra were measured at low voltage (3.5 V). B Experimental study based on a 22 design and the best-performing F-QLED selected in terms of operating temperature (T), operational lifetime, and shelf life. Inset: photographs of the best-performing F-QLED powered at 3.5 V in room light, and under flat or bent conditions in the dark. *FTB: flexible transparent barrier; S.: substrate; MG: moisture getter; Al: aluminum foil.

Optical Management: Emission Tuning for Targeted aPDT

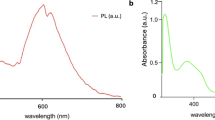

At first, to enable targeted aPDT, controlled spectral overlap between F-QLED emissions and the absorption of photosensitizers was achieved as illustrated in Fig. 3A. For high spectral overlap with the absorption of photosensitizers protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) and methylene blue (MB), the peak electroluminescence (EL) wavelengths of the tailored F-QLEDs need to be near 630 and 655 nm, respectively. This was accomplished by controlling the precursor infusion time and monitoring the photoluminescence (PL) peak emission wavelength of the quantum dots (QDs) during their synthesis to achieve PL peaks at 625 and 646 nm (as described in the ‘Methods’ section). The PL peaks were also tuned to account for the ~4-5 nm redshift we previously observed between the PL peaks of QD dispersions and the EL peaks of the QLED devices under moderate voltage. This redshift is primarily attributed to two mechanisms: Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and the electric-field-induced Stark effect. In densely packed QD solids, FRET facilitates energy transfer to neighboring QDs with smaller bandgaps (i.e., larger size) through dipole-dipole interactions, leading to a redshift of the emission spectrum24. Additionally, during EL operation under applied bias, the internal electric field can induce a Stark shift in the energy levels, further contributing to redshifted emission25. By incorporating this shift into the design, F-QLEDs with tailored EL spectra were obtained, exhibiting emission peaks at 629 nm and 651 nm, as shown in Fig. 3A.

Following the device’ emission tuning (illustrated in Fig. 3A), the EL spectra of the F-QLEDs and the absorption spectra of the corresponding photosensitizers were plotted on the same graphs as shown in Fig. 4A, B, and quantitative estimation of the overlap was performed. In addition, for comparative analysis with commercial counterparts, the spectral overlap of a commercial red-emitting flexible OLED from Konica Minolta (see the ‘Methods’ section) against the absorption spectra of the same photosensitizers were estimated (see Figure S2A and S2B). The emission peak and bandwidth of the OLED were 633 nm and 46 nm, respectively. In summary, the EL spectrum of the 651 nm F-QLED exhibited a significant spectral overlap of ~96% with the absorption spectrum of methylene blue (MB), promising effective excitation and high aPDT efficacy. This overlap was considerably high compared to the 70% overlap between the 633 nm OLED and the MB. Meanwhile, the EL spectrum of the 629 nm F-QLEDs closely matched the fourth absorption Q-band of PpIX, as shown in Fig. 4B. A moderate spectral overlap of 69% was achieved due to the very narrow absorption Q-band of PpIX, but this overlap was still higher than the 48% overlap between the 633 nm OLED and PpIX. Subsequently, the high advantage of the tunability and narrow emission of QLEDs for targeted aPDT was evidenced for both settings, when compared with the commercial OLED with a fixed and broader emission spectrum. Lastly, it is also important to note that the estimated spectral overlaps were comparable in terms of the wavelength range covered, but not in terms of intensity. Therefore, both the absorption and electroluminescence intensities – which depend on multiple factors – were normalized.

A Overlap between EL spectrum of 651 nm F-QLED and absorption spectrum of Methylene Blue (MB); B overlap between EL spectrum of 629 nm F-QLED and absorption spectrum of protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). The overlapping % corresponds to the % of the light source EL spectrum that overlaps with the PS absorption spectrum.

Experimental Study for Thermal and Barrier Management of the F-QLEDs

Subsequently, an experimental study was conducted to achieve F-QLEDs with high OPD while operating at low temperatures, as well as a good gas barrier. The F-QLEDs of the study were bottom-emitting devices with the following bottom-to-top structure: FTB-b/PEN S – ITO/ QLED/MG/ top barrier film. Where FTB-b, PEN S, ITO, and MG are flexible transparent barrier on the bottom, polyethylene naphthalate substrate, indium tin oxide, and moisture getter, respectively. QLED represents the device functional structure, ZnO NPs/646 nm QDs/Spiro-2NPB/HAT-CN/Al (as described in the ‘Methods’ section), which was the same for the F-QLEDs of this experimental study and for the rigid on-glass QLED used in the preliminary aPDT tests. For the experimental design, the effect of two structural variables in the device performance was examined. As shown in the table of Fig. 3B, these variables were the thickness of the PEN substrate and the material of the top barrier film; the corresponding levels were 50 or 125 µm for the PEN substrate thickness, and FTB or aluminum foil (Al) for the material of the top barrier film. Importantly, these levels were defined according to suitable and commercially available materials—conductive substrates and adhesive barriers—so the study aimed to provide the best combination among these materials in terms of the device output variables indicated in Fig. 3B: operating temperature, operational lifetime, and shelf life.

Accordingly, the schematic diagram in Fig. 3B shows the 22 design of the experimental study and the four F-QLED types made and named for abbreviation as follows: (1) 50 μm S/FTB; (2) 125 μm S/FTB; (3) 50 μm S/Al; and (4) 125 μm S/Al. Since the four devices were made with the same QLED functional structure and 646 nm QDs, they all exhibited similar EL spectra with a 651 nm peak and a 30 nm bandwidth at low voltage ( ~ 3.5 V, see EL spectrum of 651 F-QLED in Fig. 3A). As discussed below, after characterizing the four devices, the influence of the selected input variables on the operating temperature, operational lifetime, and shelf life was confirmed. Furthermore, the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED exhibited the best results for each output variable and was consequently selected as the best performing device, as indicated in Fig. 3B—pictures of this device powered at 3.5 V in room light and under flat and bent conditions in the dark are also shown.

Both the optoelectrical and thermal properties of the F-QLEDs were characterized to determine the best thermal performance, particularly at high OPD. The current density (J)—voltage (V), optical power density (OPD)—J, and external quantum efficiency (EQE)—J curves obtained for the four F-QLEDs are shown in Fig. 5A–C, respectively. Instead of using scan-mode measurements, the current density was allowed to stabilize before recording key parameters—an approach essential for accurate steady-state values in continuous aPDT treatment. Moreover, to enable accurate measurements and valid comparisons between devices, we followed standard protocols for QLED characterization and for the estimation of the OPD and EQE26, as detailed in Notes 1 and 2 of the Supplementary Information. In the first instance, the highest OPD and EQE peak corresponding to 21.9 mW.cm−2 (at 293 mA.cm−2) and 4.8% (112-140 mA.cm−2) were observed for the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED. Notably, as observed in the EQE - J curve, the 125 μm S/ Al F-QLED also experienced a low efficiency roll-off as its EQE remained very stable (max. variation of 10%) in a wide current density range (5.4 - 235 mA.cm−2). In contrast, the 50 μm S/FTB, 125 μm S/FTB, and 50 μm S/ Al F-QLEDs experienced earlier decay as they reached their EQE peak of 3.9, 3.7, and 3.9% at 65, 122, and 153 mA.cm−2, respectively. Importantly, although all F-QLEDs had the same functional structure sandwiched between ITO and Al electrodes, their J – V curves showed an increasing divergence between them with the increase of the voltage, which is mainly attributed to different heat dissipation and resulting operating temperature. At higher voltages, the curves diverge due to increased contact resistance and reduced carrier mobility in cooler devices. Consistently, the 125 μm S/ Al F-QLED, which operated at the lowest temperatures, also exhibited the most pronounced rightward shift in the J-V curve. Meanwhile, the divergence observed in the OPD-J and EQE-J curves is attributed to both the different heat dissipation and light outcoupling between devices. Both processes are influenced by the input variables of the experimental study, i.e., the PEN substrate thickness and the top barrier film material, as it will be analyzed in detail later. Overall, the superior performance and reliability of the 125 μm S/ Al F-QLED can be anticipated from the electro-optical characterization due to its superior heat dissipation, which mitigates thermally induced emission quenching and delays efficiency roll-off at high current densities. It is important to note that to further improve the EQE of the best F-QLED is necessary to implement additional engineering beyond thermal management. In particular, engineering the optical and electrical properties of the conductive substrate (PEN/ITO in this work) can substantially increase light outcoupling and reduce lateral resistance, ultimately leading to EQE enhancement. Lateral resistance leading to exciton quenching can become more pronounced in larger area QLEDs (16 mm2 pixel in this work) compared with QLEDs used for display (pixel area usually ≤ 1 mm2)27. Therefore, while EQE optimization is guaranteed for further development of the F-QLEDs, the priority of this work section was to obtain sufficient OPD for aPDT sessions while maintaining low device temperature to ensure safe and reliable operation.

A Current density vs voltage (J-V), B optical power density vs current density (OPD-J), C external quantum efficiency vs current density (EQE-J) curves of the four 651 F-QLED types. D Heat generation rate vs current density (Q-J), and E temperature vs heat generation rate (T-Q) curves of the F-QLEDs; F Thermal evolution comparison of the four 651 nm F-QLEDs under different heat generation rates. *The maximum F-QLED surface temperature is again indicated above each thermal photo. A temperature scale bar is included beside each thermal image for reference.

To evaluate the thermal performance, the heat generation rate (Q) vs current density (J) and the operating temperature (T) vs Q curves were obtained and plotted in Fig. 5D, E, respectively. The operating temperature corresponded to the maximum temperature measured on the emitting surface of the F-QLEDs, i.e., on the bottom surface of the devices. As observed in these graphs, the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED can withstand high current densities and subsequent high heat rates by keeping a moderate increase of the temperature over the operating range. Specifically, while the device’s current density was increased up to 300 mA.cm−2, the resulting maximum temperature was only 49.5 °C, approximately 18 to 28 °C below the maximum temperature measured for the other F-QLEDs. According to the T vs Q curves in Fig. 5E and the thermal pictures in Fig. 5F, when similar heat rates were generated in two or more of the devices, the degree of heat dissipation led to different device temperatures. The 50 μm S/FTB F-QLED exhibited the highest temperature immediately followed by the 125 μm S/FTB F-QLED. An almost intermediate temperature was observed for the 50 μm S/Al F-QLED, and the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED exhibited the lowest temperature across the operating range. It is also worth noting that mild pixel burning was consistently observed when the surface temperature of the F-QLEDs with 50 μm PEN substrates increased above 70 °C.

Overall, the most uniform thermal distribution and lowest surface temperature observed in the 125 μm S/Al F-QLEDs is attributed to the enhanced heat dissipation resulting from the combined effects of the thick PEN substrate and the top aluminum film. On one hand, both 50 and 125 μm PEN substrates had the same specific heat capacity \(({C}_{p})\), but the heat capacity \((\rho {C}_{p}V)\) of the 125 μm substrate was ~2.5 times that of the 50 μm substrate. Therefore, the more massive 125 μm substrate required more heat to raise its temperature and also stored more thermal energy away from the QLED functional layers. As for the top films, intended as both barrier and heat sink films, the thermal conductance \(\left(G\right)\) of the aluminum foil was much higher than that of the FTB film. Since the area of the two top films was the same but the Al foil was thicker than the FTB film\(,G\) is a more suitable parameter to compare the heat conduction ability of two materials with different geometries. To quantify this difference, we measured the thermal conductivity \(\left(k\right)\) of the FTB film as explained in the ‘Materials characterization’ section. The \(k\) of \(0.5{\rm{W}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-1}.{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}\) measured for the FTB film was consistent since it was in the same order of magnitude as that of the \(k\) for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) \(\left(0.14\,{{\rm{W}}.{\rm{m}}}^{-1}.{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}\right)\)28, which is the material of the supporting substrate in the FTB film. On the other hand, the \(k\) of aluminum, which is the main component of the aluminum foil, is approximately \(237\,{{\rm{W}}.{\rm{m}}}^{-1}.{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}\) based on reported data28. Subsequently, using the dimensions of each film, the \(G\) calculated for the aluminum film \(\left(447.9\,{\rm{W}}.{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}\right)\) was nearly two orders of magnitude higher than that of the FTB film \(\left(5.8\,{\rm{W}}.{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}\right)\), confirming that the aluminum film transferred the heat from the device bulk to the surroundings at a much higher rate. Consistently, the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED combining the two mentioned effects led to the best heat dissipation, as opposed to the 50 μm S/FTB F-QLED, which exhibited the worst thermal distribution and highest temperatures. Furthermore, the T vs Q curves from Fig. 5E evidence that the thermal conductance of the top film had a more important effect on the resulting heat dissipation compared to the effect of the PEN substrate thickness.

Importantly, as previously mentioned, the variations in EQE behavior and optical output among the four F-QLEDs can be primarily attributed to different heat-dissipation and light-outcoupling efficiencies. The observed EQE decline at high current densities—commonly referred to as efficiency roll-off—is generally governed by two principal mechanisms: Auger recombination and thermally-induced emission quenching29. Non-radiative Auger recombination is caused by charge injection imbalance and subsequent excessive QD charging. However, within the operational range evaluated in this study, the contribution of Auger recombination is presumed minimal compared to the effect of non-dissipated heat. This is justified by the use of QDs with an engineered core/shell/shell architecture and high photoluminescence quantum yield at room temperature, which inherently mitigate Auger-related losses30. On the other hand, thermally-induced emission quenching is likely dominated by the formation of thermal trap states at the QD surfaces as device temperatures rise29. Notably, while the EQE of the 125 μm S/ Al F-QLED remained highly stable across the tested operating range, the other devices exhibited a pronounced EQE decay at elevated temperatures. This indicates that insufficient heat dissipation—resulting in operating temperatures approaching or exceeding 70 °C—is the principal factor driving early efficiency roll-off in the 50 μm S/FTB, 125 μm S/FTB, and 50 μm S/Al F-QLEDs. In contrast, the 125 μm S/Al F-QLED maintained low operating temperatures (max. of 49.5 °C) and demonstrated exceptional EQE stability, with only a 10% decline across the 5.4–235 mA cm⁻² range.

It is also worth noting that the stable on-off operation observed in all devices below 70 °C suggests a thermal quenching largely reversible, implying that most of the thermal traps generated in this regime were temporary trap states. On the other hand, the mild pixel burning observed when the surface temperature of F-QLEDs with 50 μm PEN substrates approached 80 °C can be consistently correlated with the glass transition temperature of PET (80 °C), which was the substrate material of the FTB films. As indicated in Table S1 of the Supplementary Information, PET has the lowest Tg among the organic materials of the F-QLEDs in this study, i.e., below the Tg of the hole transport layer (Spiro 2NPB), the hole injection layer (HAT CN), and the polymer of the conductive substrate (PEN). Therefore, the onset of pixel burning near 80 °C in the 50 μm S/F-QLEDs was ascribed to the inferior thermal stability of PET, triggering a degradation cascade initiated by PET softening and deformation (particularly the PET substrate of the FTB-b), and followed by increased gas permeation and pixel burning. Moreover, the thinner PEN substrate of the 50 μm S/F-QLEDs likely exacerbated this effect by facilitating gas permeation through the bottom of the devices at temperatures near 80 °C.

As for the light outcoupling, the following optical characterization was performed to elucidate its effect on the performance of the devices. The transmittance of both bare PEN and PEN/ITO substrates was also measured, and the resulting spectra were plotted in Figure S3. As for the bare substrates, the transmittance of the 50 μm PEN substrate was 3.5% higher than that of the 125 μm PEN substrate at the QLEDs peak emission of 651 nm. Meanwhile, the transmittance of the 50 μm PEN/ITO substrate was 7.4% higher at the onset (~575 nm), 8.6% higher at 651 nm, and 9.6% higher at the end of the EL spectrum (~725 nm) as compared to the 125 μm PEN/ITO substrate. Therefore, considering that the ITO nanolayer should be similar in both substrates, the higher EQE peak of the 50 μm S/FTB F-QLED (5.4% higher) compared with the 125 μm S/FTB F-QLED can be explained by the higher transmittance observed for the 50 μm PEN/ITO substrate along the emission wavelength range of the QLEDs. Moreover, the smaller drop in the transmittance of the 50 μm PEN substrate after ITO addition can be attributed to better outcoupling of the light scattered at the PEN/ITO boundary, due to the shorter light pathway in 50 μm PEN substrates. This is supported by the reflectance spectra also shown in Figure S3. Finally, when comparing the 50 μm and 125 μm S/FTB F-QLEDs, the light outcoupling effect on the EQE could be more important than the thermal effect, since the difference in temperature between these two devices was not significant (see T vs Q Fig. 5E).

To finish the experimental study, reliability under storage conditions and stability during the operation of the F-QLEDs were evaluated by conducting shelf life and lifetime tests, respectively. For these tests, described in the ‘QLED/OLED characterization’ section, only the effect of the top barrier film was analyzed since all four F-QLEDs of the experimental study had the same encapsulation for the bottom, i.e., an FTB film laminated to the PEN/ITO substrate. While the FTB film is highly transparent to visible light, the metal foil cannot be used as the bottom barrier since the F-QLEDs were bottom-emitting devices. Therefore, the comparative analysis was only performed between FTB F-QLEDs and Al F-QLEDs, corresponding to devices with FTB and Al top barriers, respectively. Briefly, no dark spots appeared on the emitting area of both types of F-QLEDs after nearly a 1-month period, and only physical defects typical of the fabrication process (e.g., comet-like defects) were present from day 0, as can be seen in Fig. 6A. As for the optical power (OP) evolution, shown in Fig. 6B-left, the OP variation between day 0 and the last day was minimal for both devices, 1 and 12% for the Al F-QLED and the FTB F-QLED, respectively. In addition, the Al F-QLED exhibited a marked increase in OP in the first days and then dropped to nearly its initial value. This trend is more typical in stored QLEDs and can explain the different contrast between the first and last images in Fig. 6A. Lastly, both F-QLEDs are expected to have longer shelf life since these devices were powered on after the testing period and showed no alterations in OP or the appearance of dark spots.

A Dark spot monitoring and B(left) optical power (OP) evolution of the FTB F-QLED and Al F-QLED in air. The temperature and relative humidity of the chamber’s air during the monitoring period were ~22 °C and 28–30%, respectively. B(right) Normalized OP vs time curve to test the operating lifetime of the FTB F-QLED and Al F-QLED devices at 4 V for 5 h.

On the other hand, the lifetime test simultaneously confirmed superior heat dissipation and barrier property under thermal stress—subsequently better thermal stability—of the top Al barriers in the Al F-QLEDs.

While both F-QLEDs were driven at a constant voltage of 4 V and their initial current density was similar (78–84 mA cm−2), there was a marked difference in temperature and OP decay rate between the devices (see Fig. 6B-right). Remarkably, the maximum surface temperature measured at the beginning of the lifetime test was much lower for the Al F-QLED (~33 °C) than the corresponding temperature of the FTB F-QLED (~52 °C), as shown in Figure S6. Subsequently, a moderate OP decay of 22% was observed for the Al F-QLED after 5 h of continuous operation, as compared to a high decay of 70% (3.2X) for the FTB F-QLED. In lifetime terms and using L80 as the period when the optical power dropped to 80% of its initial value, the Al F-QLED (~4.5 h) improved the lifetime by 7.5X compared to the FTB F-QLED (~0.6 h). Overall, both F-QLEDs showed successful encapsulation in terms of shelf life under ambient conditions, but the performance of FTB F-QLEDs was inferior to that of Al F-QLEDs in terms of operating lifetime, further confirming the selection of the 125 μm S/ Al F-QLED as the best-performing device of the experimental study.

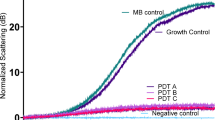

Evaluation of the F-QLED-based aPDT Efficacy in Killing MDR Pathogens

After the engineering process of the previous experimental study, the antimicrobial activity of the best-performing F-QLEDs (125 μm S/ Al F-QLEDs) was evaluated against different MDR bacteria and the cell survival fractions are represented in the bar charts of Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 7A, under treatment conditions similar to those used with the rigid on-glass QLED – an MB concentration of 100 μM and 1-hour illumination – the 651 nm F-QLED demonstrated significant aPDT efficacy by achieving a 9-log reduction in MDR S. aureus. Meanwhile, the assessment of the 651 nm F-QLED against a more resistant gram-negative MDR pathogen, i.e., MDR P. aeruginosa, resulted in a ~ 2-log reduction of the bacterial load under equivalent treatment conditions, as shown in Fig. 7B.

A Efficacy of F-QLED651nm tested against MDR S. aureus under MB concentration of 100 μM and 1-h illumination. B Efficacy of F-QLED651nm against MDR P. aeruginosa under MB concentration of 100 μM and 1-h illumination. C Efficacy of F-QLED629nm against MDR S. aureus under PpIX concentration of 1 mM and 36-min of illumination. D Efficacy of F-QLED629nm against MDR E. coli under PpIX concentration of 1 mM and 2-h illumination. The tested F-QLEDs include the best-performing 651nm F-QLEDs (F-QLED651nm) and 629nm F-QLEDs (F-QLED629nm), while the photosensitizers were MB for the F-QLED651nm and PpIX for the F-QLED629nm, respectively. All tests were performed by driving the F-QLEDs at a constant voltage of 4.5 V. Asterisks (*) indicate cases where bacterial survival was undetectable. The mean of each treatment group was compared to the control group using a t-test. Statistical significance is shown as follows: NS (not significant), * (P < 0.05), and ** (P < 0.01).

Subsequently, to demonstrate the versatility of the developed F-QLEDs for aPDT, we evaluated the aPDT efficacy of an F-QLED made with the configuration of the best-performing devices (125 μm S/ Al F-QLEDs) and peak emission wavelength of 629 nm. This 629 nm F-QLED was expected to be more effective for the other classic antimicrobial PS, PpIX (see Fig. 4B). Approximately a 2-log reduction was achieved in S. aureus under a PpIX concentration of 1 mM and 36-min illumination (Fig. 7C). Meanwhile, nearly 1-log reduction was obtained for the more resistant gram-negative E. coli strain under a PpIX concentration of 1 mM and 2-h illumination (Fig. 7D). As indicated in Fig. 7, all the aPDT in vitro tests were performed by driving the F-QLEDs at the same voltage (4.5 V).

Discussion

The primary goals in developing F-QLEDs ideal for aPDT are to overcome the limitations of current light source technologies and the urgent need for effective treatments against MDR bacteria. Despite their presence in the photomedical market, existing lasers and LED systems have inherent limitations that hinder their widespread and routine clinical application. These limitations include rigidity and bulkiness, inhomogeneous irradiation, high operating temperature requiring cooling systems, and additional accessories such as optical fibers. Such drawbacks lead to costly equipment and operation, safety risks, and patient discomfort. We aimed to overcome these hurdles by developing F-QLEDs tailored for aPDT. F-QLEDs not only offer the same features of commercial flexible OLEDs, i.e., wearable form-factors (flexibility, lightness, and thinness), a scalable emission area for homogeneous light delivery, and practical use; F-QLEDs can also offer high OPD under safe conditions, cost-effectiveness, and versatility for targeted aPDT. These additional features stemmed from their solution-process capability and tunability of pure and intense emission over a wide wavelength range.

Tailored QD synthesis for emission tunning can be achieved with high precision, however, some challenges need to be overcome for the development of F-QLEDs as ideal light sources for effective targeted aPDT. Rigid QLEDs with thick glass substrates have good barriers against moisture and oxygen and relatively good heat dissipation. The reason for this decent heat dissipation, regardless of the intrinsically low thermal diffusivity \(\left(\alpha \right)\) of glass \(\left(8.1{\rm{x}}{10}^{-7}{{\rm{m}}}^{2}.{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\right)\)28, is the high heat capacity \((\rho {C}_{p}V)\) of the massive glass substrates and covers. Particularly, the thickness of the glass substrates can be as thick as 1 mm, resulting in heat capacities approximately 11 and 27 times that of the 125 and 50 μm PEN substrates used in the present study, respectively. Rigid QLEDs with large thermal storage in glass substrates/covers can then withstand higher current densities without undergoing a significant temperature rise, unlike polymer-based F-QLEDs without thermal management. Effective material engineering is crucial to transition from rigid QLEDs to F-QLEDs without compromising thermal and barrier performance. Therefore, the engineering process of the F-QLEDs focused on (1) tuning the device emission to ensure a high overlap for targeted aPDT and efficient photon use; (2) achieving high OPD (enough for aPDT treatment) while maintaining a low and safe device temperature; and (3) enhancing operational stability and reliability in ambient conditions.

The tailored QD synthesis and proposed experimental study described in the previous section effectively led to F-QLEDs with a finely tuned emission spectrum, enhanced stability and reliability, and high OPD with low operating temperature without the need for extensive cooling mechanisms. The 125 μm S/Al F-QLED demonstrated the best performance, maintaining significantly lower temperatures at high OPDs and current densities compared to the other F-QLEDs. Specifically, its maximum surface temperature did not exceed 49.5 °C across the entire operating range, but most importantly, the device achieved an OPD as high as 18 mW·cm⁻² (at ~212 mA.cm−2) while keeping the surface temperature below 41 °C, which can be regarded as a physiological upper limit23. Consequently, the device can operate safely at high OPD (up to 18 mW·cm⁻²) while preventing burns or discomfort during extended phototherapy sessions. Overall, the superior heat dissipation and consequent low temperature of the 125 μm S/Al F-QLEDs were achieved due to the synergistic effect of the high heat capacity and thermal conductance of the 125 μm PEN substrate and the Al top barrier, respectively. The 125 μm S/Al F-QLED also exhibited the best EQE, OPD, and operating lifetime among all the studied F-QLEDs, reaching a peak OPD of 21.9 mW·cm⁻² (at 293 mA.cm−2) and a lifetime (L80) 7.5 times longer than that observed for the FTB F-QLEDs. The best performance of these parameters and the low efficiency roll-off (max. of 10% up to 235 mA.cm−2) are ascribed to the mitigation of thermally-induced emission quenching under low operating temperatures. Meanwhile, the enhancement of the operating lifetime is also attributed to the better barrier protection of 125 μm S/Al F-QLEDs, consisting of the FTB film and 125 μm PEN substrate on the bottom and the Al barrier film on the top. Finally, the emission spectra of the best-performing F-QLEDs highly overlapped the absorption spectra of methylene blue (MB, 96% overlap) and protoporphyrin IX (PpIX 69% overlap). All these technical developments were crucial for ensuring reliable and sustained aPDT performance, as discussed in the following section.

The promising results shown here open several avenues for further development to advance the application of F-QLEDs in aPDT for MDR infections and beyond. Key future directions include further advancements in wearability and efficiency of the devices, potentially involving the use of thinner top barrier films with higher thermal conductance and diffusivity, and conductive substrates with lower sheet resistance/roughness and more efficient driving patterns, as explained before. Scaling up the manufacturing of cost-effective F-QLEDs will also be crucial for the commercial viability and broad accessibility of this emerging technology. While existing OLED panel manufacturing infrastructure is compatible for the upscaling of F-QLED fabrication, the solution-processed layers of F-QLEDs require the integration of solution-based deposition under inert atmosphere to maintain material stability. Additionally, the conventional encapsulation used in rigid on-glass QLEDs and OLEDs – typically involving rigid glass covers and UV-cured epoxy resins – are unsuitable for flexible devices due to their lack of mechanical compliance. Currently, no standard encapsulation method exists for F-QLEDs that meets the dual demands of flexibility and suitable protection against oxygen and moisture. In this context, the lamination-based encapsulation approach proposed in this work offers several advantages: low material and processing costs, ease of implementation, and compatibility with high-throughput roll-to-roll manufacturing. Collectively, these advances will support improved device durability, user comfort, regulatory compliance, and production scalability, thereby accelerating the path toward real-world deployment.

aPDT is a potential strategy to address the global crisis of antibiotic resistance, and here we developed F-QLEDs capable of efficient, wavelength-tunable aPDT. These F-QLEDs overcome multiple limitations of the currently existing aPDT light sources, such as lasers and LED systems. Our F-QLEDs demonstrated outstanding efficacy in reducing the viability of representative MDR bacteria, such as MDR S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa, confirming the potential of F-QLEDs as a potent light source for aPDT. These results, consistent with previous studies6,31, show that a higher overlap between the emission spectra of F-QLEDs and the absorption spectra of photosensitizers (PSs) is crucial to ensure more effective PS excitation and higher aPDT efficacy. Our 651 nm QLEDs have a 96% overlap with methylene blue’s (MB) absorption spectra, while current state-of-the-art OLEDs only achieve a 70% overlap. Consequently, under identical test conditions, these OLEDs are 10-1000 times less effective than our QLEDs in killing MDR wound pathogens (see Figure S4 of the Supplementary Information). This underscores the importance of two key characteristics of the light source for high aPDT efficacy: tunable emission wavelength and narrow bandwidth, both of which our QLEDs possess.

In this study, MB was chosen as a PS due to its extensive history, widespread availability, and FDA approval for treating methemoglobinemia32. Additionally, we used PpIX to extend our biological study4. The inclusion of both MB and PpIX demonstrated the versatility of our F-QLED platform for targeted aPDT treatment, achieved by successfully tuning its emission spectrum within the 629-651 nm wavelength range.

Our aPDT results with QLEDs are consistent with studies using traditional light sources like lasers, showing that different pathogens have varying susceptibilities to the same PS, and different PSs have distinct effects on the same pathogen33. For example, under equivalent light conditions, MB at a lower concentration (100 μM) achieves a 5-8 log reduction in MDR S. aureus, while PpIX at a higher concentration (1 mM) results in a 1-2 log reduction for the same strain. This underscores the need to tailor PS choices to the specific pathogen. This can only be accomplished if the wavelength of the light source can be adjusted per the choice of PSs, further highlighting the importance of the wavelength tunability of QLEDs for the effectiveness of aPDT. It is worth noting that for negative strains, such as E. coli and P. aeruginosa, that are in general refractory to all the antimicrobial therapies34, tailoring the choice of PS and tuning the light source wavelength might not be effective enough, combining aPDT with antibiotic therapy may be an effective solution.

Integrating F-QLEDs into standard infection management tools, such as Solventum Tegaderm™ transparent dressings for wound infections, could further enhance the efficacy and convenience of aPDT. Lastly, extensive pre-clinical studies in various infection models, including complex wound and burn infections where MDR pathogens are common, followed by large clinical trials, will be necessary to establish the practical utility and benefits of F-QLEDs in real-world medical settings.

In conclusion, the F-QLED platform developed in this study for aPDT represents a promising solution for addressing the global crisis of MDR infections. With its wearability, high OPD at low device temperature, and affordability, this platform could be seamlessly integrated into clinical infection management resources, such as being incorporated into wound dressings as a bandage. Such applications are expected to provide significant benefits to patients suffering from MDR infections, such as refractory wound infections, burn infections, and diabetic foot infections. By effectively treating these infections, the platform could not only reduce their prevalence but also prevent their progression into long-term disabilities or life-threatening conditions. Furthermore, the F-QLED platform’s affordability, all-in-one design, user-friendliness, portability, and low power requirements make it versatile for use both in clinical settings and outside the clinic. For example, it could be deployed on battlefields as a mobile, wearable device to disinfect wounds and prevent infections in injured soldiers. This innovative approach holds immense potential to revolutionize infection management, extending its impact beyond traditional healthcare facilities.

Methods

Device fabrication

QD synthesis and emission tuning

Core/shell/shell (C/S/S) quantum dots (QDs) with a CdSe/ZnS/ZnCdS composition were synthesized via a two-step hot injection method using a nitrogen-filled Schlenk line system27,35. The first step involved nucleation and growth of the CdSe cores, followed by a second step for shelling the cores with ZnS and ZnCdS layers, sequentially. Emission tuning was achieved during the shelling step by controlling the precursor infusion time and monitoring the photoluminescence (PL) peak emission wavelength. Small aliquots were periodically extracted from the QD dispersion, and their PL spectra were immediately measured to track the emission peak as a function of time (λ vs. t). Precursor infusion for shelling was halted once the desired peak emission wavelength was reached. A longer infusion time resulted in a redshift of the emission peak, corresponding to increased QD size.

Pre-fabrication steps for rigid QLEDs

The ITO/glass substrates were cleaned by sequential sonication in the following solutions for 15 minutes each: (1) 2% v/v Hellmanex III in milli-Q water, (2) milli-Q water, (3) a 1:1 mixture of isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and acetone, and (4) ethanol. After solvent cleaning and drying with compressed N₂, the substrates were placed on a hot plate at 140 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, they underwent plasma cleaning for 10 min using an oxygen plasma ETCH chamber.

Pre-fabrication steps for F-QLEDs

Prior to F-QLED fabrication, the PEN/ITO substrates (50 and 125 μm thick) and encapsulation materials were subjected to thermal treatment for degassing and water removal within a vacuum oven located inside an N2-filled glove-box. Two 3M commercial materials were used for final encapsulation, a flexible transparent barrier (3M FTB3-50a, referred here as FTB) and an aluminum(Al) foil tape (3M 2552). The FTB sheet was composed of a 50 μm PET substrate, a thin multi-layer coating made of polymer (non-halogenated cross-linked resin) and metal oxide (barrier) layers, and a 12-μm pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) layer. Meanwhile, the Al foil sheet had a PSA layer and a total thickness of 381 μm. Before baking, liners were removed from all materials, then, the PEN/ITO substrates were placed inside the oven keeping the ITO side up, while the FTB and Al sheets were placed keeping the adhesive side up. Subsequently, baking under vacuum (-27 kPa) at 80 °C was conducted for a period ≥ 16 hours. Right before layer deposition, the PEN/ITO substrates were treated in an oxygen plasma ETCH chamber to eliminate organic impurities and enhance surface hydrophilicity.

Device layers deposition

The layer deposition of the devices was performed within an N2-filled glove-box by solution processing and vacuum evaporation of the lower and upper layers, respectively. Then, two different dispersions, ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) in Cs2CO3/methoxyethanol solution and QDs in chlorobenzene were filtered (0.2 μm pore size) and sequentially spin-coated onto the ITO substrates. The ZnO NPs were also synthesized in-house using a precipitation method27,36,35. After spin-coating, substrates were transferred to a thermal evaporation chamber for deposition of organic layers and top metal contacts. This involved thermal evaporation of a 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis[N-naphthalenyl(phenyl)-amino]-9,9-spirobifluorene (Spiro-2NPB) layer (100 nm), a 1,4,5,8,9,11- hexaazatriphenylene-hexacarbonitrile HAT-CN layer (20 nm), and Al electrodes (100 nm) under high vacuum (6 ×10-7 – 1×10-6 mbar).

Rigid QLED encapsulation

After completing the layer deposition, the rigid devices were transferred to a separate glovebox for encapsulation. A moisture getter was first attached to the cavity side of a clean glass cover, which was subsequently baked at 80 °C. UV glue was then applied along the edges of the cover, which was placed onto the top of the rigid QLED. UV curing was carried out for 2 minutes on each side of the device. Finally, thermal curing was performed by placing the device on a hot plate at 80 °C for 1 hour to complete the encapsulation.

F-QLED encapsulation

Once all functional layers were deposited, the flexible devices were transferred to another glove-box for encapsulation by film lamination. Prior to lamination, all the barrier sheets processed in step 1 were baked again on a hot plate at 80 °C, along with flexible moisture getters. Encapsulation of the devices entailed lamination of a flexible moisture getter on top of the Al electrode contacts, followed by lamination of barrier sheets on the top and bottom of each device. Two different top encapsulations were performed by laminating either an FTB sheet or an Al sheet at the top of the devices. Lamination of transparent FTB sheets on the bottom of all F-QLEDs was performed to finish the encapsulation. Summarizing, four different F-QLED types were made for the experimental study depending on the top-encapsulation material and the PEN/ITO substrate thickness, as follows: 1) F-QLED with 50 μm PEN/ITO and top FTB; 2) F-QLED with 125 μm PEN/ITO and top FTB; 3) F-QLED with 50 μm PEN/ITO and top Al; and 4) F-QLED with 125 μm PEN/ITO and top Al (see Fig. 3B).

QLED/OLED characterization

After fabrication and encapsulation, the devices were transferred out of the glove box for characterization.

J-OPD-V and thermal characteristics

The characteristic curves of the F-QLEDs were built by fixing the device driving voltage (V) to different values with a Bo-Test source meter. After applying a specific voltage, the current vs. time curve shown by the Bo-Test meter was monitored to allow time for stabilization, then, when the current was approximately constant, the current density (J), the luminance (L), and the surface temperature (T) were measured in dark conditions. The L was measured with a Konica Minolta LS-110 meter, while the T was taken from thermal images captured by a Perfect Prime IR0019 thermal camera on the device bottom side, i.e., the emitting side. The procedures to obtain the optical power density (OPD), the external quantum efficiency (EQE), and the heat generation rate (Q) are described step by step in Notes 1-3 of the Supplementary Information, respectively. Once the OPD, EQE and Q were calculated at each measuring point (voltage), all the J-V, OPD-J, EQE-J, Q-J, and T-Q curves were plotted as shown in Figs. 5A to 5E.

The EL spectra of the F-QLEDs and the commercial OLED from Konica Minolta (module A9F4C0A) were measured using an Ocean Optics USB 2000+ spectrometer, by placing the optical fiber in the normal direction of the emitting surface of the devices.

Device reliability and stability tests

For the shelf-life test, the F-QLEDs were stored along with a humidity/temperature (H/T) meter inside a small antechamber filled with room air. Storage in the sealed antechamber enabled better control and low variation of the air conditions in the interior, as observed for the humidity and temperature monitored over the full test period. In intervals of time, the chamber was opened to record the H/T conditions and to transfer out the devices for quick testing. For each test, the same voltage (3.5 V) was used to power the devices, then, the luminance was recorded using the Konica Minolta LS-110 meter, while pixel pictures were taken with a hi-res cellphone camera.

The device lifetime curves were obtained by driving the F-QLEDs at a constant voltage with the Bo-Test source meter and recording the optical power (OP) with a Thorlabs PM121D power meter. The power meter was connected to an S121D power head with a silicon detector, which was taped on top of the devices after aligning the sensor active area with the emitting pixel. During the test in dark conditions, the current was also monitored with the Bo-Test meter system. Given that a QLED is a non-coherent light source and that there is a distance between the detector surface and the emitting surface, the recorded OP can’t be absolute, so the measured OP was relative but useful for lifetime tests. Finally, the OP vs t curves were plotted by normalizing the measured OP with respect to its initial value.

Materials characterization

QD dispersions

Measurement of the photoluminescence (PL) spectra for QD dispersions was performed with the Ocean Optics USB 2000+ spectrometer. A vial with the QD dispersion was placed on top of a flat 365 nm UV lamp, then, the optical fiber tip was positioned close and perpendicular to the vial wall to measure the PL spectrum.

Solid films

The transmittance spectra of the 50 and 125 µm PEN and PEN/ITO substrates were measured under normal mode with an Evolution 220 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Meanwhile, the reflectance spectra of 50 and 125 um PEN/ITO substrates were obtained by coupling an ISA-220 integrating sphere accessory to the spectrophotometer. The thermal conductivity of the FTB films was measured by the Modified Transient Plane Source (MTPS) technique using a C-Therm Trident instrument. Then, the thermal conductance was calculated as described in Note 4 of the Supplementary Information.

QLED biological tests

Bacterial strains and their growth conditions

Three MDR bacterial human isolates were used in this study, including S. aureus collected by US military hospitals37, E.coli by US CDC & FDA Antibiotic Resistance Isolate Bank38, and P. aeruginosa (from Emory University School of Medicine39. The S. aureus and P. aeruginosa are bioluminescent among these strains, allowing real-time infection monitoring via bioluminescence imaging in the pig skin burn infection model described below. All strains were preserved at -80°C and revived when needed by streaking out the cells on the brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultivating them in an incubator at 37°C. The bacterial suspension, whenever needed, was obtained by cultivating the single colony of bacteria in BHI broth (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in the shaker at 200 rpm.

QLED-based aPDT against bacterial infection in vitro

Bacterial cells grown to log phase (OD = 1) were harvested by centrifuging at 10 K rpm 3 times and then washed two times with PBS to halt their growth. These cells in a volume of 20 μl were then subject to QLED-based aPDT treatment in a glass-bottom dish (35 mm).

The aPDT was initiated by incubating the bacteria with the specified concentration of MB or PPIX for 15 mins. Afterward, a QLED device (651 nm for MB and 629 nm for PPIX) was used to illuminate the bottom of the glass dish with the specified voltage and time length. The antimicrobial effects of aPDT were evaluated by counting the bacterial cells surviving the treatments on antibiotic-free agar plates after dilution.

QLED-based aPDT against pig skin burn infections

A pig skin burn infection model was created as previously described37 using the bioluminescent S. aureus or P. aeruginosa strain. The porcine skin was provided by Wellman Center for Photomedicine as waste tissue from other experiments. Its utilization was compliant with relevant USA legislation and approved by the MGH biosafety committee (2017B000062). When freshly collected, the skin was washed, disinfected, and dried in a laminar flow cabinet. This skin tissue was then cut into pieces using sterile biopsy punches (0.6 cm in diameter) and burned by a block preheated to 100°C. These burned skin pieces were transferred to individual wells of a 24-well plate, then infected by spreading 5 µL of S. aureus or P. aeruginosa suspension at a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL over the center of the burned area. Once infected, the specimens were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min or 24 h to evaluate the antimicrobial effect of the QLED-based aPDT for the immediate or the established bacterial infections.

During aPDT, MB at the specified concentration was applied to the infected area of pig skin. After an incubation period of 15 min, the bacterial infection was illuminated using a rigid QLED with a peak wavelength of 651 nm. The illumination was conducted under the specified voltage and for a specific duration. The resulting treatment efficacy was evaluated by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS Spectrum), where the bioluminescence signal from the luminescent S. aureus or P. aeruginosa strain is proportional to the number of live bacteria, thus allowing real-time monitoring of the therapeutic efficacy of the tested conditions. The data acquired through IVIS was further validated by the bacterial viability cell counting (CFU/mL), during which the treated tissue was homogenized within a FastPrep lysing matrix tube A (MP Biomedicals) in a FastPrep-24 Classic Instrument (MP Biomedicals) and then spread and grown on the BHI agar plates.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. The raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. World Health Organization, 2014.

Ventola, C. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm. therapeutics 40, 277 (2015).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019.

Hamblin, M. R. & Hasan, T. Photodynamic therapy: a new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease?. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 3, 436–450 (2004).

Feng, Y., Tonon, C. C., Ashraf, S. & Hasan, T. Photodynamic and antibiotic therapy in combination against bacterial infections: efficacy, determinants, mechanisms, and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 177, 113941 (2021).

Piksa, M. et al. The role of the light source in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 1697–1722 (2023).

Mordon, S. et al. Light emitting fabric technologies for photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 12, 1–8 (2015).

Shirasaki, Y., Supran, G. J., Bawendi, M. G. & Bulović, V. Emergence of colloidal quantum-dot light-emitting technologies. Nat. Photonics 7, 13–23 (2013).

Sanderson, K. & Castelvecchi, D. Tiny ‘quantum dot’particles win chemistry Nobel. Nature 622, 227–228 (2023).

Murray, C., Norris, D. J. & Bawendi, M. G. Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E= sulfur, selenium, tellurium) semiconductor nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 8706–8715 (1993).

Triana, M. A., Hsiang, E.-L., Zhang, C., Dong, Y. & Wu, S.-T. Luminescent nanomaterials for energy-efficient display and healthcare. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1001–1020 (2022).

Hartlove, J. Looking Ahead to the Next Decade of Quantum-Dot Displays. Inf. Disp. 39, 10–10 (2023).

Bourzac, K. Quantum dots go on display. Nature 493, 283 (2013).

Triana, M. A., Restrepo, A. A., Lanzafame, R. J., Palomaki, P. & Dong, Y. Quantum dot light-emitting diodes as light sources in photomedicine: photodynamic therapy and photobiomodulation. J. Phys.: Mater. 3, 032002 (2020).

Shen, H. et al. Visible quantum dot light-emitting diodes with simultaneous high brightness and efficiency. Nat. Photonics 13, 192–197 (2019).

Won, Y.-H. et al. Highly efficient and stable InP/ZnSe/ZnS quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nature 575, 634–638 (2019).

Kim, D. C. et al. Intrinsically stretchable quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nat. Electron. 7, 365–374 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Development of the ink-jet printing technology for 55-inch 8K AMQLED display. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 31, 355–362 (2023).

Ishida, T., Nakanishi, Y., Iwata, N. & Izumi, M. How NanoLED Will Enable Next-Generation Displays. Inform. Disp. 39, 26–31 (2023).

Kim, T. et al. Efficient and stable blue quantum dot light-emitting diode. Nature 586, 385–389 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Quantum dot light emitting devices for photomedical applications. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 25, 177–184 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Flexible quantum dot light-emitting devices for targeted photomedical applications. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 26, 296–303 (2018).

Spranley, T. J., Winkler, M., Dagate, J., Oncale, D. & Strother, E. Curing light burns. Gen. Dent. 60, e210–e214 (2012).

Kagan, C., Murray, C. & Bawendi, M. Long-range resonance transfer of electronic excitations in close-packed CdSe quantum-dot solids. Phys. Rev. B 54, 8633 (1996).

Caruge, J.-M., Halpert, J. E., Bulović, V. & Bawendi, M. G. NiO as an inorganic hole-transporting layer in quantum-dot light-emitting devices. Nano Lett. 6, 2991–2994 (2006).

Jin, W. et al. On the accurate characterization of quantum-dot light-emitting diodes for display applications. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 35 (2022).

Dong, Y. et al. Ultra-bright, highly efficient, low roll-off inverted quantum-dot light emitting devices (QLEDs). SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 46, 270–273 (2015).

Triambulo, R. E. & Park, J.-W. Heat evolution and dissipation in organic light-emitting diodes on flexible polymer substrates. Org. Electron. 28, 123–134 (2016).

Sun, Y. et al. Investigation on thermally induced efficiency roll-off: toward efficient and ultrabright quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. ACS nano 13, 11433–11442 (2019).

Bae, W. K. et al. Controlling the influence of Auger recombination on the performance of quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 4, 2661 (2013).

Kim, M. M. & Darafsheh, A. Light sources and dosimetry techniques for photodynamic therapy. Photochemistry Photobiol. 96, 280–294 (2020).

Cardozo, A. P. M. et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with methylene blue and its derivatives in animal studies: Systematic review. Photodermatol., Photoimmunol. Photomed. 40, e12978 (2024).

Ghorbani, J., Rahban, D., Aghamiri, S., Teymouri, A. & Bahador, A. Photosensitizers in antibacterial photodynamic therapy: An overview. Laser Ther. 27, 293–302 (2018).

Sperandio, F. F., Huang, Y. Y. & Hamblin, M. R. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to kill Gram-negative bacteria. Recent Pat. anti-infective drug Discov. 8, 108–120 (2013).

Dong, Y., Chen, H., Wu, S.-T. & He, J. Quantum dot light emitting devices (QLEDs) and method of manufacture. US Patent 10,593,902 (2020).

Mashford, B. S. et al. High-efficiency quantum-dot light-emitting devices with enhanced charge injection. Nat. photonics 7, 407–412 (2013).

Feng, Y., Tonon, C. C. & Hasan, T. Dramatic destruction of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections with a simple combination of amoxicillin and light-activated methylene blue. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 235, 112563 (2022).

Feng, Y., Swain, J. W., Palanisami, A., Ashraf, S. & Hasan, T. One-step detection and classification of bacterial Carbapenemases in 10 min using fluorescence identification of β-lactamase activity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59, 02517–02520 (2021).

Damron, F. H. et al. Construction of mobilizable mini-Tn 7 vectors for bioluminescent detection of gram-negative bacteria and single-copy promoter lux reporter analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4149–4153 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support for this work from DoD Army STTR Award No. W911NF-22-P-0018, the Florida High Tech Corridor Council (FHTCC) matching grant, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research FA9550-20-1-0063 and FA9550-23-1-0656. We extend our gratitude to Mark Roehrig of 3M for supplying the barrier films used in this study and to Dawn Muyres and Max Nagarajan of Solventum for their valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.T., Y.F., Y.D., and T.H. conceived the concept. M.A.T. and Y.F. planned and conducted the major experiments. S.J.S. and Y.T. assisted in the fabrication of QLED devices for additional testing under M. A. T.’s supervision, while R.J.L. provided clinical guidance for QLED design. N. K.E. and S.K. performed part of the QLED antimicrobial tests under the supervision of Y.F. M.A.T. and Y.F. prepared and revised the manuscript. Y.D. and T.H. provided overall guidance for the experimental design, the execution, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.A.T., R.J.L. and Y.D. are employees of QLEDCures LLC. The company had direct involvement in study design, data collection, or analysis. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Triana, M.A., Feng, Y., Saiji, S.J. et al. Advancing flexible quantum dot light-emitting diode technology for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. npj Flex Electron 9, 110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00481-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00481-w