Abstract

The durability of copper (Cu) canisters against corrosion is critical for the licensing of deep geological repositories. Assessing oxic corrosion, a primary degradation mechanism, is essential for ensuring the reliability of such repositories. Due to the complex interactions influencing oxic corrosion, a comprehensive model is necessary for evaluating Cu canister corrosion. This study develops a model for the KAERI Reference Disposal System (KRS), incorporating mixed-potential theory with key O2 consumption reactions, including Cu corrosion, Cu(I) oxidation, FeS2 oxidation, aerobic microbial activity, and O2 dissolution and consumption. Simulation of 11 scenarios revealed that the representative KRS case would experience a maximum corrosion depth of 9.3 μm on the Cu canister after 2.3 years due to oxic corrosion, under conditions that are unfavorable for the initiation of pitting corrosion. These results suggest that oxic corrosion is not a threat to the isolation of spent nuclear fuels in KRS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

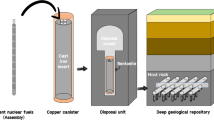

Deep geological repositories (DGRs) are attracting widespread interest as they offer a permanent disposal solution for hazardous spent nuclear fuels (SNFs) from operational nuclear fission power plants, contributing significantly to the achievement of net-zero emissions. To enhance safety, a DGR typically incorporates two main barrier systems: an engineered barrier and a natural barrier1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The engineered barrier consists of canisters for containing SNFs and a bentonite backfill to seal the disposal holes and tunnels. Within these canisters, SNF is secured in a cast iron insert, while the outer shell is covered with Cu. These canisters are then placed into disposal holes and sealed with bentonite, which is surrounded by host rock serving as the natural barrier. Failure of the DGR system can arise from corrosion. Given long enough time required to isolate high-level wastes safely, preventing Cu canister corrosion indefinitely without human intervention is impractical. Consequently, corrosion emerges as a critical concern in the licensing and construction process of DGRs.

Recent literature has successfully evaluated the integrity of Cu canisters in DGRs against corrosion processes1,8,9. However, despite these efforts, the precise impact of various reactions on oxic corrosion of Cu canisters remains partially understood. Such reactions include FeS2 oxidation, Cu oxidations, Cu(I) oxidations, aerobic microbial activity, and the dissolution of O2 in groundwater5,7,9,10,11,12. It was reported that the Cu(I)-species oxidation rate is governed by a minor portion of Cu(I)-species, such as Cu+ free, CuCl, CuCl3-2, and CuClOH-11. Also, the consumption of FeS2 on the FeS2 oxidation rate was not considered in the existing models which may lead to underestimating the corrosion depth of the Cu canister1,9.

Additionally, there are remaining questions about the interaction of corrosion products with bentonite. Maintaining bentonite performance is one of the top priority for deep geological repositories, and there has been a lot of research to investigate the alteration of bentonite13,14,15. Despite of these efforts, there are no models or experiments reporting the distribution of Cu corrosion products in the bentonite which is fundamental to analyze and predict the alteration of bentonite performance.

Simultaneously, the importance of pitting corrosion cannot be ignored and has received considerable attention in different national programs (Sweden, Finland, and Canada)5,16,17. For the initiation of pitting corrosion, there are pre-requisites which are the formation of a passivation film and the breakage of the passivation film18. Hence, if the model can predict the corrosion potential, then it will be a valuable tool to evaluate the possibility of pitting corrosion through a comparison of predicted corrosion potential and the reported pitting corrosion potential.

These complicated interaction phenomena are challenging to assess through experimental methods alone, requiring a numerical model that can consider multiphysics effects simultaneously. Therefore, this research introduces a new multiphysics model to evaluate the effects of various reactions on the oxic corrosion of Cu canisters while calculating the corrosion potentials and distribution of corrosion products in bentonite. This model is focused on the early oxic period in a deep geological repository. This model incorporates Cu(I) oxidation, FeS2 oxidation, aerobic microbial activity, and the removal of O2,gas by groundwater via dissolution and consumption at the interface of engineered barrier and host rocks. Simultaneously, the corrosion potential of the Cu canister is calculated by Mixed-potential theory. Also, the new oxidation kinetics of Cu(I) and FeS2 were implemented and validated with the literature data while considering the minor portion of Cu(I)-species and the consumption of FeS2. Applied to the KAERI Reference disposal System (KRS), this model aims to elucidate the evolution of O2 and its effects on Cu corrosion from the perspectives of corrosion potential and corrosion depth1.

Results and discussion

Fate of O2 in the near-field

As shown in Table 1, a total of 11 cases were simulated for KRS. The CnSm cases (where n represents the weight contents of FeS2 in bentonite, and m represents the size of FeS2 particles) were designed to evaluate the effects of FeS2 contents and particle size on corrosion. Figs. 1 and 2 present the depletion time of O2 in the engineered barrier system (bentonite and backfilled materials) and the O2 consumption ratio by the five reactions, respectively. The depletion time was calculated for when less than 0.1%v/v of O2 remained in the engineered barrier system, allowing comparison with the Mont Terri Full-scale Emplacement experiments12. Because the Mont Terri experiments as detector with a detection limit of 0.1%v/v to quantify the remaining O2 in the near-field, which only can measure the O2,gas12. The depletion times ranged from 0.4 to 22.4 years for 9 cases (Except C0S0 and C0S0React). These 9 cases exhibited faster depletion times of O2 with higher FeS2 contents (wt%) and smaller FeS2 particles due to the more rapid FeS2 oxidation kinetics, as described in Table 2. These cases show the FeS2 oxidation can be the primary reaction for O2 depletion, where 79.3–96.0% of O2 was reacted with FeS2.

Interestingly, the predicted depletion times of O2 for C0.1S0.5 and C1S0.5 (5.6 and 1.4 years, respectively) are longer than the Mont Terri Full-scale Emplacement (FE) experimental data (a half year)12,19. The Mont Terri used MX-80 bentonite, and the FeS2 contents and particle sizes (see Table 1) are situated between the C0.1S0.5 and C1S0.5 cases. This discrepancy could be attributed to faster flow rates of gas and groundwater and the composition of groundwater in Mont Terri. The Mont Terri Full-scale experiments were conducted in more porous host rock types (Opalinus Clay with 0.13-0.16 porosity) compared to these model cases (granite with 0.01 porosity)19. Additionally, the groundwater may contain some other oxidizing agents, such as HS-, which can rapidly consume the O220,21. Tomonga et al. also pointed out that the fast depletion of O2 could be due to gas exchange from the engineered barrier to host rocks during the Mont Terri experiment19. This comparison highlights the influence of host rock types and groundwater composition on the oxic corrosion of Cu canisters, though further research is necessary for a full comparison the Mont Terri experiment and the numerical model.

The C0S0 and C0S0React cases simulated 0 wt% FeS2 (KJ-II bentonite). In these two cases, the depletion times of O2 are 124.7 and 2.3 years, respectively. The C0S0 case shows that Cu and Cu(I) oxidations are the predominant reactions (>94.7%), while C0S0React demonstrates that the dissolved O2 reacted with reducing agents (such as HS-) in the ground water as the primary reaction (> 98.6%). The aerobic microbial activity contributes only 2.6 and 0.1% of the total O2 consumption, respectively. The consumption of O2 in the groundwater shows a significant difference between the C0S0 and C0S0React cases. This difference arises because the C0S0React case accounts for the consumption of O2 at the interface between the engineered barrier and host rocks, assuming that the groundwater of DGR contains other oxidizing agents (such as HS-) which react with O21,22,23,24.

Among these two cases, the C0S0React case is considered as the representative case for KRS by including the consumption of O2 in the groundwater. This case suggests that the oxic period (O2 depletion time) can be shorter than 2.3 years for KRS, though it necessitates additional analysis through the combination of numerical models and field experiments. This is because the C0S0React case assumes that the oxidizing agents (HS-) do not migrate into the engineered barrier system. The movements of oxidizing agents can induce faster depletion of O2 in the engineered barriers23,25.

In the previous research, we predicted that the O2 depletion time would require at least 100 years, consistent with the expectation of CSM1,9. However, by incorporating the several different O2 consumption reactions, this model now predicts an O2 depletion time of 2.3 years. Due to this short period (2.3 years), this model indicates that the long-cell action suggested by the previous research (Chae et al.) in the deep geological repository can be ignored1. Previous research suggested that the long-cell action could accelerate the corrosion of Cu canister by less than 1 μm under conditions of 100 years of O2 remaining. This implies that the long-cell action cannot be sustained beyond 2.3 years, and any resulting acceleration in corrosion depth should be even smaller than the previous research1.

Corrosion depth of Cu canister

Figure 3 presents the calculated maximum corrosion depths (oxic phase) on the surface of the Cu canister from each case. The deepest corrosion depths, observed in each case, originate from the canister’s top corner surface, exemplified by Case C0.1S0.5 (as depicted in Fig. 4). These corrosion depths vary from 1.8 to 531.7 μm, demonstrating a correlation with the O2 depletion times illustrated in Fig. 1. This suggests that longer O2 depletion times promote increased O2 transport to the Cu surface. A significant portion of Cu corrosion is caused by O2 reduction, with over 99.7% oxidation observed in all cases (see Fig. 3). Conversely, the majority of Cu(II) precipitates in the bentonite as CuO, rather than contributing to the further corrosion of the Cu canister.

For the KRS scenario, the expected maximum corrosion depth of the Cu canister is 9.3 µm for the oxic phase, which closely aligns with the findings from the C0S0React case. This case simulates O2 consumption in the presence of dissolved HS- species at the interface between engineered barrier and granite host rock. The corrosion depth of 9.3 μm is comparable to the best-estimate case for the KBS-3 deep geological repository, which is 6.4 um, and closely matches the 10 μm depth estimated for the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) deep geological repository, despite variations in conditions and geometries, as noted in refs. 9, 22. Such comparisons highlight the minimal impact of uniform oxic corrosion on Cu canister integrity in the KRS, KBS-3, and NWMO deep geological repositories. This is further quantified by the respective corrosion percentages of only 0.02, 0.01, and 0.03% for Cu thicknesses of 50 (for both KRS and KBS-3) and 30 mm (for NWMO).

Figure 4 demonstrates that the maximum corrosion depths on the Cu canister predominantly occur at the top edge, where corrosion is significantly more extensive compared to the sides and bottom. This is attributed to the prolonged availability of O2 in the disposal tunnel, which ensures a continuous supply of O2 to the top surface. As corrosion progresses, the side and bottom surfaces exhaust their O2 supply, whereas the top surface continues to receive O2 from the disposal tunnel. Although the top edge may appear more susceptible to oxic corrosion, its greater thickness (~74 mm), although this value can be changed in the future, suggests a reduced susceptibility over time, mitigating concerns regarding the canister’s structural integrity3.

Corrosion potentials of Cu canister

Figure 5 illustrates the calculated corrosion potentials, highlighting the impact of various reactions on the likelihood of localized corrosion on the Cu canister. The corrosion potentials begin at -0.31 VSCE, decreasing to below -0.5 VSCE for all cases except for the C0S0 case. This observed trend towards low corrosion potentials, similar to those recorded in experiments conducted at approximately 50 °C with low O2 levels, was documented by He and Ahn26,27. They reported notably lower corrosion potentials, ranging from -0.7 to -0.8 VSCE, under high temperature conditions (50 °C), elevated chloride concentrations (282 – 2820 mol·m-3), and extremely low O2 concentration conditions (below 6E-6 mol·m-3). These experimental conditions closely mirror those in the simulated cases of this study, where the average temperature of the canister surface exceeds 50 °C most of the time, as depicted in Fig. 5.

An initial decrease in corrosion potentials (from -0.3 to -0.4 VSCE) coincides with O2 depletion (Fig. 5). The O2 concentration near the canister becomes exceedingly low, resulting in a drop in the corrosion potential to between -0.3 to -0.4 VSCE. At approximately -0.4 VSCE, the corrosion potential is maintained through the backward diffusion of Cu2+ from the bentonite, as demonstrated in Fig. 6 for the C0.01S0.1 case. While the reduction of Cu2+ ions could provide electrons for Cu oxidation, the resultant cathodic currents are insufficient to sustain higher corrosion potentials throughout the simulation period. The second decline in corrosion potentials (-0.4 to -0.7 VSCE) results from the depletion of Cu2+, leading to a further reduction in potential.

The C0S0React case, representing the KRS condition, shows a corrosion potential below -0.5 VSCE after 50 years, significantly lower than the experimentally determined pitting corrosion potentials. Previous studies by Allah et al. and Sridhar and Cragnolino reported pitting corrosion potentials ranging from 0.2 to 1 VSCE (30–3160 mol m-3 Cl-, pH 7.26 – 13.0, 25 °C) and -0.024 to 0.628 VSCE (95 °C Cl-, 0.169 – 28.206 mol·m-3, pH 6.8 – 8.3)28,29. All simulated cases in this study exhibit the corrosion potentials below these pitting corrosion potentials, suggesting a low likelihood of pitting corrosion occurring. This finding aligns with other modeling studies, indicating that pitting corrosion is unlikely to pose a significant risk in deep geological repositories30,31. However, there can be more variation cases and it requires analyzing more cases with meso-scale modeling to fully understand and predict the pitting corrosion of Cu canisters, incorporating the formation of oxide films.

Corrosion products distribution in bentonite

Figure 7 presents the mass fraction of corrosion products distribution in the bentonite after 10 years of oxic corrosion. In Fig. 7, the calculated mass fractions of corrosion products in the bentonite (KRS case – C0S0React) from the five different orientations (top, top-edge, side, bottom-edge, and bottom surface of Cu canister) are compared with experimentally reported values from KURT (Kong et al.) for 10 years aerobic corrosion tests with 30 °C32. Interestingly, the model shows quite good agreement with the reported values, except for the data for 0.5 mm. This trend indicates that corrosion products can diffuse out from the Cu surface by Cu(I)- and Cu(II)-chloride complexes. Besides, the higher contents of Cu at the 0.5 mm position could occur by the detached Cu oxide layers from the Cu specimen, although the sampling method was not properly described in Kong et al. Also, Cu(I) and Cu(II) portions are calculated to be 29 and 71% in bentonite from the simulation results. This trend also agrees with the trend of 10 years of experimental results from Kong et al, which show that Cu(II) is a major portion of Cu corrosion products.

Figure 8 shows the calculation results of corrosion products distribution in the bentonite after 50 years, where the oxic corrosion progress has ceased, for the KRS case. As can be seen in Fig. 8, the precipitated Cu(I) and Cu(II) amount to 0.45 wt% at maximum in the fully saturated bentonite. Also, the distributed total corrosion products (Cu(I) and Cu(II)) and Cu(I) are gradually decrease and become less than 0.1 wt% after 15 mm of bentonite. In contrast, the shape of Cu(II) distribution shows a peak around the 8 mm position in the bentonite. This unique shape of Cu(II) distribution can be explained by the reaction of Cu(II) in eq. 2. As stated in eq. 2, Cu(II) can be formed by the oxidation reaction of Cu(I) by O2. In the bentonite, the Cu(I) source originates from the oxidation of the Cu canister surface, and O2 is supplied from the bulk of the bentonite. Therefore, these two chemical species can have the highest reaction rates somewhere in the middle of the bentonite.

Highlights from model results

This study assessed the oxic corrosion of Cu canisters within the KRS concept through 11 cases, considering various O2 consumption reactions in the near-field. The numerical simulations highlight the crucial role of O2 consumption reaction, particularly the interaction between the groundwater and other oxidants. This interaction may account for the swift O2 depletion observed in the Mont Terri full-scale experiments, although further research is essential to accurately replicate the conditions of Mont Terri full-scale experiments. Future studies should include an analysis of groundwater composition and accessory minerals in the host rocks to better understand the mechanisms behind the rapid consumption of O2 in the Mont Terri experiments.

The C0S0React case has been identified as representative of the KRS concept. According to its findings, the expected corrosion duration is approximately 2.3 years, with a maximum Cu canister corrosion depth of 9.3 μm in KRS, closely aligning with the depths recorded for KBS-3 and NWMO deep geological repositories (6.4 and 10 μm, respectively). Also, the long-cell action cannot be sustained for more than 2.3 years, and this have a very negligible effect on corrosion depth compared to previous research (Chae et al.)1. Additionally, the oxic phase of KRS conditions does not show a higher corrosion potential than the experimentally reported film breakage potential, which is one of the important factors for the initiation of pitting corrosion. These findings indicate that oxic corrosion may not pose a significant threat to the structural integrity of Cu canisters, suggesting that validation of the Cu canister’s integrity in oxic conditions could be achievable within a few years under the KRS concept.

The distribution of corrosion products has been suggested based on the developed model, and it was compared with experimental data. This result can be useful for evaluating the alteration of bentonite properties through interaction with corrosion products. Also, it can be used for evaluating the efficiency of retarding radionuclides from spent nuclear fuels. We believe this finding can support the understanding of oxic corrosion of the Cu canister and its interaction with bentonite which is an important research topic to guarantee the performance of bentonite.

Also, this model was independently developed by the authors in South Korea considering the new kinetics equation for Cu(I) oxidation, FeS2 oxidation, and O2 consumption in groundwater. Nonetheless, this model shows a similar corrosion depth of the Cu canister as the other national programs (SKB and NWMO). Therefore, we believe this model confirms corrosion damage on the Cu canister in the oxic phase. We believe that this independent model can be a reference for other countries to compare with their own results. Long-term corrosion of the Cu canister can only be compared with numerical results due to the required time of corrosion experiments.

Throughout the analysis of this model, a pH-changing model that considers corrosion film formation is required to reduce the uncertainty of the results while avoiding the underestimation of the corrosion of the Cu canister. However, this model does not currently predict pH value and the formation of a corrosion film on the Cu surface. These pH and formation of passivation film may lead to localized corrosion through the film breakage with local acidic condition on the surface of the Cu canister due to hydrolysis of Cu(I) species. In such cases, localized corrosion might occur and affect the performance of the Cu canister. This remaining challenge can be overcome by combining a meso-scale model for pH changes with Cu corrosion. Therefore, it is recommended to develop such a model in the future to evaluate the corrosion of the Cu canister.

Despite these reassuring outcomes, uncertainties persist, primarily due to the absence of designated KRS sites, necessitating reliance on data and conditions from KBS-3 for bridging some gaps. The potential influence of host rocks, acknowledged as significant, remains underexplored due to current data limitations, particularly concerning comprehensive applications and validations with granite host rocks in KRS settings. The effects of microbiological organisms are quite complex, as suggested by Lee et al.33 and Little et al.34. These authors have shown the effects of microbiological activity on corrosion potential and rates, and these aspects should be addressed in more detail to avoid underestimating the corrosion depth of Cu canister33,34. Therefore, conducting future field experiments is crucial for refining the models with accurate conditions, thus bolstering the reliability of predictions regarding the extent of Cu canister corrosion damage from oxic processes.

Methods

Considered reactions between chemical reagents in deep geological repository

The overall reactions (chemical, electrochemical, and aerobic microbial activity) during the oxic period are summarized in Fig. 9. Trapped O2 acts as the major oxidizing agent of Cu corrosion for the oxic period17,22,35. Simultaneously, the trapped O2 can react by the following reactions: Cu(I) oxidation, FeS2 oxidation, aerobic microbial activity, and dissolution in groundwater. The model considers these reactions comprehensively.

Unlike the existing corrosion models, this model implemented the contribution of a minor Cu(I)-species on Cu(I) oxidation kinetics based on Yuan et al. 11.The source term for Cu(I)-species is the corrosion of Cu by the trapped O2, which is reduced while oxidizing the Cu to form Cu2O and Cu(I)-Cl- complexes in the Cl- containing ground water. Additionally, the Cu(I)-Cl- complex can be further oxidized to form Cu(II) species, which can then be reduced back to Cu(I), perpetuating the cycle. During this cycle, minor species of Cu(I) can significantly contribute to the overall kinetics due to their higher accessibility to O2 molecules as reported by Yuan et al.11. Thus, the minor Cu(I) species like Cu+ free, CuCl, CuCl3-2, and CuClOH- are also considered in this model. The overall Cu(I) oxidation can be generalized into the reaction show as (1).

FeS2, present in bentonite as one of several accessory minerals, can alter geochemical environments through its reaction with O2, producing the formation of acid mine tailings10,36,37,38. The oxidation of FeS2 involves multiple electrochemical steps, transitioning from -1 to +6 oxidation states of sulfur, forming various intermediate species. The overall FeS2 oxidation can be generalized into the reaction shown as (2)10,39. Improvements have been achieved from the previous studies by incorporating a new approach to consider the consumption effects of FeS2 on the kinetics of FeS2 oxidation37,38,40,41,42,43,44. This model adopts the kinetics parameters of FeS2 oxidation systematically suggested by Williamson and Rimstidt10.

Deep geological repository systems have alkaline groundwater. Under the alkaline solution, numerous studies have identified sulfate ion (SO42-) as the thermodynamically stable chemical species of sulfur45,46,47,48,49. Also, Manaka recently showed that sulfate ion is the stable form of pyrite oxidation after 3 years of pyrite oxidation in bentonite49. Hence, we have considered SO42- as the final products of HS- oxidation.

The bentonite and backfilled materials are porous mediums that contain aerobic microbes12,50,51. The activity of these aerobic microbes can consume the trapped O2 in the near-field, eventually leading to the depletion of O2. Simultaneously, some of the O2 can dissolve in the groundwater1,12,19,24,52. The dissolved O2 can be consumed by stronger oxidizing agents, such as HS-, from the host rocks. This model incorporates these phenomena, providing a comprehensive view of the reaction processes.

The explained reactions were incorporated in the model by using the kinetics equations in the section Kinetics of reactions. The Kinetics of reactions section also includes all the parameters required for kinetics reactions, and the supplementary validation includes the validation of these kinetics reactions by comparing with literature data. The given reaction kinetics equation in the Kinetics of reactions section is combined in the generalized reactive-transport equations which are provided in the Generalized governing equations section.

Generalized governing equations

In our model, the authors employed a thermal-hydraulics-chemical (T-H-C) coupled model, which was developed by Chae et al. based on the MOOSE framework1,53,54. A sequential coupling between thermal-hydraulics and chemical reactions was utilized to analyze the effects of thermal-hydraulic (T-H) conditions on chemical reactions. Additionally, the chemical reactions were represented through Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) to integrate with the transport equations of chemical species.

The governing equations for T-H behaviors are based on mass and energy conservation principles. The thermal governing equation is expressed as follows:

where \(\phi\) is the porous medium porosity (dimensionless), \({\rho }_{{solid}}\) and \({\rho }_{{liquid}}\) are the densities of the solid and liquid parts of the porous medium (dimensionless), csolid and cliquid are the heat capacities [J· kg-1K-1], S is the degree of saturation in the porous medium (dimensionless), T is the system temperature [K], t is simulation time [year], \(\lambda\) is the thermal conductivity of the porous medium or target system [W·m-1·K-1], \(h\) is the specific enthalpy of a single phase (e.g., solution or porous fluid) [J·kg-1], and \(F\) is the advective Darcy flux of a porous fluid [m·yr-1], which can be calculated by Darcy velocity of fluid in the hydraulics governing equations.

The hydraulic behavior within the porous medium (bentonite and backfilled materials) is modeled by the following equation:

where M is the mass density of the fluid [kg·m-3], \(\rho\) is the fluid density [kg m-3], \(k\) is the porous medium (bentonite and backfill) permeability [m2], \(\mu\) is the fluid viscosity [N·m-2yr-1], P is the porous medium pore pressure [Pa], and \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration [m s-2].

The reactive transport equation (chemical), representing conservation of mass during chemical reactions and transports, is given by:

where \(\phi\) is the porous medium porosity (dimensionless), \(S\) is the degree of saturation in bentonite and backfill materials (dimensionless), Caq,i is the concentration of dissolved chemical species i [mol·m-3], Daq,i is the diffusion coefficient of dissolved chemical species i [m2·yr-1], Rj is the reaction rate for reaction j, [mol·m-3·s]. Also, the concentration of gas phase of O2 is considered by the similar equation:

where \({O}_{2,{gas}}\) is the concentration of O2 in the gas phase [mol·m-3], \({D}_{{O}_{2,{gas}}}\) is the diffusion coefficient of O2 in the gas phase [m2·yr-1], and Rk is the dissolved reaction from gas to aqueous [mol·m-3·s].

Kinetics of reactions (FeS2 oxidation, Cu(I) oxidation, and microbial activity)

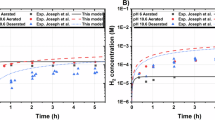

Cu(I) and FeS2 oxidation were considered as the chemical reaction terms (Rj) in eq. 5. The equation for Cu(I) oxidation was adopted from Yuan et al.

where k1,0 is a function of Cl- and pH [m3·mol-1·s-1], EA,1 is the activation energy of the Cu(I) oxidation reaction, [J mol-1], R is the ideal gas constant, T is the temperature of the bentonite or backfill materials [K], Cu(I) is the concentration of all Cu(I) species [mol·m-3], and O2 is the concentration of O2 [mol m-3]11.

The k1,0 function was fitted by the following equation:

where k1,0 is kinetics constant [m3 mol-1 s-1], C is log10Cl- and Cl- is the Cl- concentration [mol m-3] unit, and I is the ionic strength of ground water [M]. All the parameters are given in Table 3, and eq. 8 is valid for Cl- 0.1 M–0.7 M, pH 6.5–10, and ionic strength 0.7 – 5 M range. This equation was derived by combining kinetic constants (Table 4) of Cu+, CuCl, CuCl2-, CuCl3-2, and CuClOH- with chemical speciation distributions by the following equation:

where k is the kinetics constant of the corresponding Cu(I) chemical species [m3 mol-1 s-1], f is the fraction of the corresponding Cu(I) chemical species Cu(I) among soluble Cu(I) species [mol·m-3]. The chemical speciation calculation was done by considering the Cu reactions as listed in Tables 4 and 5 through Specific Interaction Theory (SIT)55.

The FeS2 oxidation reaction rate was considered by:

where k2,0 is the kinetics constant 1E-8.19 [mol0.61 kg0.39 m-2 s-1], O2 is the concentration of O2 [mol∙m-3], and H+ is the concentration of H+ [mol∙m-3]10. Here, the authors converted the concentration unit from mol∙kg-1 to mol∙m-3 by dividing it by 1000 (water density 1000 kg m-3). Williamson and Rimstidt demonstrated that the FeS2 oxidation rate depends only on the concentration of O2 and H+ 10. In a deep geological repository, the oxidation kinetics of FeS2 can be influenced by its consumption since significant amounts of FeS2 can be oxidized over the geological timescale used for simulation. The authors derived the following kinetics equation to account for the effects of FeS2 consumption during oxidation:

where \({A}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\) is the specific surface area of FeS2 [m2 g-1], \({m}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\) is the total mass of FeS2 in the system [g], V is the total volume of the system that containing FeS2 [m3], \({\rho }_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\) is the density of FeS2 [g mol-1], \({c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)\) is the concentration of remaining FeS2 at the calculation time t [mol m-3], and \({c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}\) is the concentration of the initial FeS2 [mol m-3]. The term \(\frac{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)}{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}}\) is implemented to reflect the total mass reduction of FeS2 as it is consumed by the oxidation reaction, equating the total mass change ratio to the concentration change for the same volume of solution.

The specific surface area of FeS2 particles was assumed to be spherically shaped, and the calculation of this area used the following equation:

where \({S}_{{{FeS}}_{2}}\) is the surface area of the sphere geometry [m2], \({\rho }_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\) is the density of FeS2 5.01E6 [g m-3], \({V}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\) is the volume of FeS2 [m3], \({c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)\) is the concentration of remaining FeS2 at the calculation time t [mol m-3], and \({c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}\) is the concentration of initial FeS2 [mol m-3]. The term \({\left(\frac{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)}{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}}\right)}^{\frac{2}{3}}\) on the right side of eq. 12 was implemented to account for the surface area reduction as FeS2 is consumed during the oxidation reactions. This term \({\left(\frac{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)}{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}}\right)}^{\frac{2}{3}}\) is derived from a constant density of FeS2 which is

where \({m}_{1}\) is initial mass, \({m}_{2}\) is changed mass after the oxidation reaction, \({r}_{1}\) is radius of initial FeS2, \({r}_{2}\) is radius of FeS2 after the oxidation reaction. Therefore, the surface area change can be derived from eq. 13 into the following equation:

where \({m}_{1}\) and \({m}_{2}\) can be calculated by concentration of FeS2:

The \({\left(\frac{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2}}\left(t\right)}{{c}_{{Fe}{S}_{2},0}}\right)}^{\frac{2}{3}}\) term can express the surface change ratio during the oxidation reaction. Also, FeS2 is insoluble in ground water pH range as can be seen in Fig. 10. FeS2 can be dissolved in three ways: oxidative dissolution, reductive dissolution, and chemical dissolution. Among these, the oxidative dissolution is described as eq. 11. The other dissolution mechanisms are not possible or negligibly small for pH 8 – 10 and low temperature conditions (under 100 °C). The reductive dissolution is only possible for high temperature (over 90 °C) with high H2 partial pressure (over 0.8 MPa) conditions which is impossible for the DGR case56,57. Therefore, in this model, the authors neglect HS- producing from FeS2 in the ground water.

The aerobic microbial activity was implemented as the pseudo first order reaction:

where k3 is the kinetic constant of aerobic microbial activity [mol m-3yr-1], O2,aq is the concentration of dissolved O2. The kinetic constant of aerobic microbial activity (k3) was set to 6.94E-3 [yr-1]9.

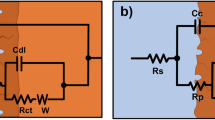

Here, the authors adopted electrochemical reactions on the Cu surface using Butler-Volmer equations, which were suggested by King and Kolář (CSM) and adopted in the previous research of the authors1,9. The sum of the total currents (in Ampere unit) of anodic and cathodic currents follows the mixed-potential theory. The densities of cathodic currents and anodic currents (A m-2) were calculated at each quadrature point and multiplied by the surface area of each element (four or three quadrature points in each element). This is where the local partial differential solutions were estimated for calculating the global solution (numerical results) by combining the local solutions to calculate the total currents (net zero). In this model, if the total charge rate becomes lower than 10 C yr-1, then the model determines that the calculation results satisfy the mixed-potential theory and display the corrosion potential. The Butler-Volmer equations (17–21) are summarized in Table 6, with the definitions of variables and parameters in Table 7 and Table 8.

The overall corrosion depth was calculated by the corrosion of Cu by O2 and Cu2+ as the following equation:

where d is the corrosion depth of Cu [m], \({\varnothing }_{{ben}}\) is the porosity of bentonite, \(\tau\) is the tortuosity of bentonite, \(D\) is the diffusion coefficient of the chemical species O2 and Cu2+ [mol∙m2 ∙ s-1], S is the degree of saturation in the bentonite, EA is the activation energy for the diffusion of chemical species O2 and Cu2+, T is the temperature of bentonite [K], \(\rho\) is the density of Cu [mol∙m-3], and \(n\) are number of electrons transferred from a single O2 and Cu2+ species which are 4 and 1 respectively.

Application in deep geological repository system

The developed model was applied to the KAERI Reference disposal System (KRS) under oxic conditions to evaluate the integrity of the Cu canister2. As shown in Table 1, a total of 11 cases covered the possible combinations of FeS2 content and particle sizes as described in Table 958,59,60. The removal of O2,gas by dissolving in groundwater was simulated in this model using eq. 5, 6. This approach was based on reports that the removal of O2 by dissolving it in groundwater enhances the depletion of O2 inside bentonite and backfilled materials12,19. Moreover, the C0S0React case assumed that the dissolved O2 (O2,aq) was consumed in the groundwater by reacting with other oxidizing agents (such as HS-) to simulate a more realistic case7,9,17,23,25,61. In this case, the concentration O2,aq was set to 0 mol∙m-3 at the interface of the engineered barrier and natural barrier (granite host rock), which acts as the source term for oxidizing agents. The details of the initial conditions are provided in Table 10.

The KRS was selected to simulate the corrosion of Cu canisters under oxic corrosion conditions. Table 11 presents the physical properties of the bentonite and backfill materials, as well as the host rock for KRS52. The geometry and mesh, illustrated in Fig. 11, depict a single disposal unit. The overall calculation was conducted for the single disposal unit in 2-Dimensions to save on computational costs. In the model, rectangular meshes were employed to control mesh quality, especially the size of meshes perpendicular to the surface of the Cu canister. This perpendicular mesh size on the Cu surface to the bentonite can influence the corrosion rate by altering the flux of chemical reagents. This approach allowed us to control the mesh quality on the Cu canister surface while also saving computational costs. Additionally, the Cu corrosion rate was evaluated using mixed potential theory via Butler-Volmer equations, with further consideration given to Cu(II) reduction on the Cu surface, as can be seen in Table 6. The derived equation 7 and 11 were applied to the KRS unit to analyze the overall effects of FeS2 and Cu(I) oxidation. The groundwater pH was set to nine and remained constant throughout the simulation, following the conditions in DGR cases from Sweden and Finland (Olkiluoto and Forsmark), due to the absence of specific data for KRS9,62,63.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study validation datasets is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Chae, N. et al. Coupled mixed-potential and thermal-hydraulics model for long-term corrosion of copper canisters in deep geological repository. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 26 (2023).

Lee, J., Cho, D., Choi, H. & Choi, J. Concept of a Korean reference disposal system for spent fuels. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 44, 1565–1573 (2007).

Choi, H.-J., Lee, J. Y. & Choi, J. Development of geological disposal systems for spent fuels and high-level radioactive wastes in Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 45, 29–40 (2013).

Briggs, S., McKelvie, J., Keech, P., Sleep, B. & Krol, M. Transient modelling of sulphide diffusion under conditions typical of a deep geological repository. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 52, 200–203 (2017).

Hall, D. S., Behazin, M., Jeffrey Binns, W. & Keech, P. G. An evaluation of corrosion processes affecting copper-coated nuclear waste containers in a deep geological repository. Prog. Mater. Sci. 118, 100766 (2021).

Briggs, S., McKelvie, J., Sleep, B. & Krol, M. Multi-dimensional transport modelling of corrosive agents through a bentonite buffer in a Canadian deep geological repository. Sci. Total Environ. 599–600, 348–354 (2017).

King, F., Hall, D. S. & Keech, P. G. Nature of the near-field environment in a deep geological repository and the implications for the corrosion behaviour of the container. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 52, 25–30 (2017).

Rashwan, T. L. et al. Exploring the governing transport mechanisms of corrosive agents in a Canadian deep geological repository. Sci. Total Environ. 828, 153944 (2022).

Svensk Kärnbränslehantering A. B. Copper Sulfide Model (CSM)-Model improvements, sensitivity analysis, and results from the integrated sulfide project inter-model comparison exercise. Technical Report SKB TR TR-18-04 (2019).

Williamson, M. A. & Rimstidt, J. D. The kinetics and electrochemical rate-determining step of aqueous pyrite oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 5443–5454 (1994).

Yuan, X., Pham, A. N., Xing, G., Rose, A. L. & Waite, T. D. Effects of pH, chloride, and bicarbonate on Cu(I) oxidation kinetics at circumneutral pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1527–1535 (2012).

Giroud, N. et al. On the fate of oxygen in a spent fuel emplacement drift in Opalinus Clay. Appl. Geochem. 97, 270–278 (2018).

Marty, N. C. M., Fritz, B., Clément, A. & Michau, N. Modelling the long term alteration of the engineered bentonite barrier in an underground radioactive waste repository. Appl. Clay Sci. 47, 82–90 (2010).

Goo, J.-Y., Kim, J.-S., Kwon, J.-S. & Jo, H. Y. A literature review on studies of bentonite alteration by cement-bentonite interactions. Econ. Environ. Geol. 55, 219–229 (2022).

Manjanna, J., Kozaki, T. & Sato, S. Fe(III)-montmorillonite: basic properties and diffusion of tracers relevant to alteration of bentonite in deep geological disposal. Appl. Clay Sci. 43, 208–217 (2009).

European Commission. State of the Art document on the corrosion behaviour of container materials. European Commission (2004).

Svensk Kärnbränslehantering A. B. An Update of the State-of-the-Art Report on the Corrosion of Copper under Expected Conditions in a Deep Geologic Repository. SKB TR-10-67 (2010).

Obeyesekere. Trends in Oil and Gas Corrosion Research and Technologies: Pitting corrosion. Woodhead Publishing. 215–248 (2017).

Tomonaga, Y. et al. On-line monitoring of the gas composition in the Full-scale Emplacement experiment at Mont Terri (Switzerland). Appl. Geochem. 100, 234–243 (2019).

Vinsot, A. et al. CO2 data on gas and pore water sampled in situ in the Opalinus Clay at the Mont Terri rock laboratory. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C. 33, S54–S60 (2008).

Office fédéral des eaux et de la géologie. Mont Terri Project - Geochemistry of Water in the Opalinus Clay Formation at the Mont Terri Rock Laboratory. Report No. BWGG-5-E (2003).

Keech, P. G., Behazin, M., Binns, W. J. & Briggs, S. An update on the copper corrosion program for the long-term management of used nuclear fuel in Canada. Mater. Corros. 72, 25–31 (2021).

Chae, N., Park, S. & Choi, S. Cross-verified Measurement of Sulfide Concentration in Anaerobic Conditions Using Spectroscopic, Electrochemical, and Mass Spectrometric Methods. J. Nucl. Fuel Cycle Waste Technol. 21, 43–53 (2023).

King, F., Chen, J., Qin, Z., Shoesmith, D. & Lilja, C. Sulphide-transport control of the corrosion of copper canisters. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 52, 210–216 (2017).

Chen, K. Y. & Morris, J. C. Kinetics of Oxidation of Aqueous Sulfide by O2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 6, 529–537 (1972).

He, X. & Ahn, T. Effects of chloride on copper corrosion in extremely low-oxygen concentration conditions. in NACE CORROSION NACE-2019 (NACE, 2019).

He, X., Ahn, T. & Gwo, J.-P. Corrosion of Copper as a Nuclear Waste Container Material in Simulated Anoxic Granitic Groundwater. Corrosion 74, 158–168 (2017).

Allah, A. G. G., Abou‐Romia, M. M., Badawy, W. A. & Rehan, H. H. Effect of halide ions on passivation and pitting corrosion of copper in alkaline solutions. Mater. Corros. 42, 584–591 (1991).

Sridhar, N. & Cragnolino, G. A. Effects of Environment on Localized Corrosion of Copper-Based, High-Level Waste Container Materials. CORROSION 49, 967–976 (1993).

Briggs, S., Lilja, C. & King, F. Probabilistic model for pitting of copper canisters. Mater. Corros. 72, 308–316 (2021).

Nuclear Waste Management Organization. Review of the NWMO copper corrosion allowance. NWMO TR-2013-04 (2013).

Kong, M., Lee, M., Kim, G.-Y., Jang, J. & Kim, J.-S. Characterization of Compacted Ca- and Na-Bentonite with Copper Corrosion Products in the KAERI Underground Research Tunnel. Minerals 13, 898 (2023).

Lee, J. S., Ray, R. I., Little, B. J. & Lemieux, E. J. Evaluation of Deoxygenation as a Corrosion Control Measure for Ballast Tanks. Corrosion 61, 1173–1188 (2005).

Little, B. J., Lee, J. S. & Ray, R. I. The influence of marine biofilms on corrosion: A concise review. Electrochim. Acta 54, 2–7 (2008).

King, F., Litke, C. D., Quinn, M. J. & LeNeveu, D. M. The measurement and prediction of the corrosion potential of copper in chloride solutions as a function of oxygen concentration and mass-transfer coefficient. Corros. Sci. 37, 833–851 (1995).

Salmon, S. U. Geochemical modelling of acid mine drainage in mill tailings: Quantification of kinetic processes from laboratory to field scale. Doctoral Dissertation, KTH Royal Institute of Technology (2003).

Xu, T., White, S. P., Pruess, K. & Brimhall, G. H. Modeling of Pyrite Oxidation in Saturated and Unsaturated Subsurface Flow Systems. Transp. Porous Media 39, 25–56 (2000).

Xu, Y. et al. A hydro-thermal-geochemical modeling framework to simulate reactive transport in a waste coal area under amended and non-amended conditions. Heliyon 6, e02803 (2020).

Dos Santos, E. C., De Mendonça Silva, J. C. & Duarte, H. A. Pyrite Oxidation Mechanism by Oxygen in Aqueous Medium. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 2760–2768 (2016).

Alakangas, L., Lundberg, A. & Nason, P. Simulation of pyrite oxidation in fresh mine tailings under near-neutral conditions. J. Environ. Monit. 14, 2245–2253 (2012).

Molson, J. W., Fala, O., Aubertin, M. & Bussière, B. Numerical simulations of pyrite oxidation and acid mine drainage in unsaturated waste rock piles. J. Contam. Hydrol. 78, 343–371 (2005).

Tabelin, C. et al. Prediction of acid mine drainage formation and zinc migration in the tailings dam of a closed mine, and possible countermeasures. MATEC Web Conf. 268, 6003 (2019).

King, F. & Behazin, M. A Review of the Effect of Irradiation on the Corrosion of Copper-Coated Used Fuel Containers. Corrosion and Materials Degradation 2 678–707 at https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd2040037 (2021).

Jodeiri Shokri, B., Doulati Ardejani, F., Ramazi, H. & Moradzadeh, A. Predicting pyrite oxidation and multi-component reactive transport processes from an abandoned coal waste pile by comparing 2D numerical modeling and 3D geo-electrical inversion. Int. J. Coal Geol. 164, 13–24 (2016).

Todd, E. C., Sherman, D. M. & Purton, J. A. Surface oxidation of pyrite under ambient atmospheric and aqueous (pH = 2 to 10) conditions: electronic structure and mineralogy from X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 881–893 (2003).

Bonnissel-Gissinger, P., Alnot, M., Ehrhardt, J.-J. & Behra, P. Surface Oxidation of Pyrite as a Function of pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 2839–2845 (1998).

Moses, C. O., Nordstrom, D., Herman, J. S. & Mills, A. Aqueous Pyrite Oxidation by Dissolved Oxygen and by Ferric Iron. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 51 (1985).

Guilinger, T. R., Schechter, R. S. & Lake, L. W. Kinetic study of pyrite oxidation in basic carbonate solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 26, 824–830 (1987).

Manaka, M. Extent of pyrite oxidation by dissolved oxygen in alkaline solutions including purified sodium bentonite. Appl. Geochem. 148, 105548 (2023).

Martinez-Moreno, M. F. et al. Impact of compacted bentonite microbial community on the clay mineralogy and copper canister corrosion: a multidisciplinary approach in view of a safe Deep Geological Repository of nuclear wastes. J. Hazard. Mater. 458, 131940 (2023).

Burzan, N. et al. Growth and Persistence of an Aerobic Microbial Community in Wyoming Bentonite MX-80 Despite Anoxic in situ Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 13, (2022)

Lee, C., Cho, W.-J., Lee, J. & Kim, G. Y. Numerical Analysis of Coupled Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical (THM) Behavior at Korean Reference Disposal System (KRS) Using TOUGH2-MP/FLAC3D Simulator. J. Nucl. Fuel Cycle Waste Technol. 17, 183–202 (2019).

Permann, C. J. et al. MOOSE: Enabling massively parallel multiphysics simulation. SoftwareX 11, 100430 (2020).

Park, S. et al. Coupled 3D thermal-hydraulic code development for performance assessment of spent nuclear fuel disposal system. Nucl. Eng. Technol. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2024.04.043.

Adjustment, Estimation, and Uses of Equilibrium Reaction Constants in Aqueous Solution. Chemistry International -- Newsmagazine for IUPAC. 29, 14–15 (2007).

Truche, L., Berger, G., Destrigneville, C., Guillaume, D. & Giffaut, E. Kinetics of pyrite to pyrrhotite reduction by hydrogen in calcite buffered solutions between 90 and 180 °C: Implications for nuclear waste disposal. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 2894–2914 (2010).

Svensk Kärnbränslehantering A. B. A Review of the Properties of Pyrite and the Implications for Corrosion of the Copper Canister. SKB TR-13–19 (2013).

Svensk Kärnbränslehantering A. B. Mineralogy and sealing properties of various bentonites and smectite-rich clay materials. SKB TR-06-30 (2006).

MalGoBalGaeBitNaLa, Y., Heui-ju, C., Min-soo, L. & Seung-yeop, L. Measurement of Properties of Domestic Bentonite for a Buffer of an HLW Repository. J. Nucl. Fuel Cycle Waste Technol. 14, 135–147 (2016).

Nuclear Waste Management Organization. Review of the THMC Properties of MX-80 Bentonite. Nuclear Waste Management Organization. NWMO TR-2019-07 (2019).

Lefers, J. B., Koetsier, W. T. & Van Swaaij, W. P. M. The oxidation of sulphide in aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 15, 111–120 (1978).

Posiva Oy. On the Origin and Chemical Evolution of Ground Water at the Olkiluoto Site. POSIVA 96-04 (1996).

Gimeno, M. J., Tullborg, E.-L., Nilsson, A.-C., Auqué, L. F. & Nilsson, L. Hydrogeochemical characterisation of the groundwater in the crystalline basement of Forsmark, the selected area for the geological nuclear repositories in Sweden. J. Hydrol. 624, 129818 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Institute for Korea Spent Nuclear Fuel (iKSNF) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2021M2E1A1085194), and Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20224000000120).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C. developed the numerical model and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. S.S. contributed to the multi-threads calculation of the developed model for reactive-transport phenomena. R.I.F. was data curation with a major contributor in writing the manuscript. S.C. supervised the research and reviewed and edited the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chae, N., Seo, S., Foster, R.I. et al. Oxic corrosion model for KAERI Reference disposal system via O2 consumption reactions and mixed-potential theory. npj Mater Degrad 8, 80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00497-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-024-00497-z

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating radiation-induced corrosion depths in copper canisters of varying thicknesses for KAERI reference disposal system

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Effects of environmental factors on copper corrosion in an aerobic deep geological repository

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Advancements in Long-term Safety Evaluation Technology for Engineered Barrier System (EBS): A Comprehensive Review of Korea’s High-Level Waste Disposal R&D Program

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2025)

-

Corrosion processes affecting copper-coated used fuel containers for the disposal of spent nuclear fuel: critical review of the state-of-knowledge

npj Materials Degradation (2024)