Abstract

The effects of multilayer sea sand particles of varying sizes and Shewanella algae (S. algae) on the corrosion behavior of 316 stainless steel (SS) were investigated. The findings reveal that in a sterile environment, sand hinders the diffusion of dissolved oxygen, thereby impeding the growth of the passive film and enhancing the corrosion of 316 SS. The promotion effect intensifies as the particle size of the sand decreases. In a non-sterile environment, in the absence of sand, S. algae accelerates the corrosion by consuming dissolved oxygen, and expediting the breakdown of passive film. The corrosion acceleration caused by S. algae is markedly greater than that induced by sand. When sand is present, it markedly reduces the effective attachment of S. algae, thereby mitigating the corrosion-accelerating effect of S. algae. Additionally, a reduction in sand particle size leads to a decrease in S. algae attachment and an enhancement in corrosion inhibition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In marine environments, it is common for the surfaces of structures to be covered with sediments such as sea sand, which provides conditions for the attachment and proliferation of marine microorganisms, thus leading to a severe risk of under-deposit microbiologically influenced corrosion (UD-MIC) for the structures1. UD-MIC is not only related to the geometric morphology of sea sand (such as particle size and thickness), but also closely associated with the types of microorganisms2,3,4. Shewanella algae (S. algae) is a rod-shaped, facultatively anaerobic microorganism capable of forming brown colonies, as a typical iron-reducing bacteria (IRB), possesses a special metabolic mechanism and is widely present in marine environments. IRB have two opposite effects on metal corrosion behavior under different growth conditions: they reduce dissolved oxygen or hinder the diffusion of dissolved oxygen to carbon steel through respiration under aerobic conditions, thereby inhibiting the corrosion of carbon steel5,6; under anaerobic conditions, they use H2 generated on Fe as a source of electrons and energy7,8,9, producing H+ and releasing electrons. The production of H+ leads to local acidification of the biofilm environment, and the released electrons are transferred to corrosion products on the surface of carbon steel, reducing insoluble Fe(III) compounds to soluble Fe(II) compounds. This prevents the formation of a complete protective layer of corrosion products on the surface of carbon steel, thereby promoting the corrosion of Fe10,11,12,13. In recent years, the problem of metal corrosion caused by S. algae has attracted increasing attention from scholars13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Gaps formed by sea sand covering metal surfaces serve not only as shelters for S. algae but also modify its adsorption and reproduction patterns on metal surfaces22,23. Moreover, the metabolic activities of S. algae can affect the local environment inside these gaps, including pH and dissolved oxygen concentrations. We have previously examined the effects of a single layer of sea sand and S. algae on the under-deposit corrosion of 316 stainless steel (SS)24. Our results showed that the grain size of sea sand has a notable impact on the adsorption of S. algae on 316 SS surfaces and the local environment within the gaps between sand grains, leading to a complex relationship between the UD-MIC rate of 316 SS and the size of sea sand grains. This is closely tied to the diffusion of S. algae and related metabolic substances through the single layer of sea sand. However, due to the complex and variable nature of the marine environment, the geometric configurations (such as grain size and thickness) of sea sand deposited on structure surfaces are diverse, potentially altering the interactions between sea sand and S. algae. As a result, the local environment beneath the sea sand and the UD-MIC mechanisms become complex and variable25,26,27. It is reasonable to expect that when the sea sand layer is thicker, the adsorption of S. algae on 316 SS surfaces and the diffusion of related metabolic substances will differ from those under a single layer of sea sand. Thus, the influence of multilayer sea sand grain size on the UD-MIC mechanism of 316 SS deserves further study.

In light of this, this paper employs electrochemical methods (OCP, EIS, and potentiodynamic polarization curves), composition analysis (XPS), and morphological characterization (SEM, CLSM) to investigate the influence of multilayer sea sand of different particle sizes interacting with S. algae on the under-deposit corrosion behavior of 316 SS in a marine environment. The aim is to establish the mechanism of UD-MIC of 316 SS under the combined effects of multilayer sea sand and S. algae. Simultaneously, a comparison is made with the influence of single-layer sea sand and S. algae on the MIC behavior of 316 SS24, elucidating the differences in the UD-MIC mechanisms of 316 SS when covered with multilayered versus single-layer sea sand.

Results

Characterization of biofilms

The 316 SS bare metal and 316 SS samples covered with multilayer sea sand of different particle sizes were immersed in a simulated seawater medium solution containing S. algae for three days. The attachment of microorganisms on the sample surfaces was observed using SEM, and the corresponding images are shown in Fig. 1. As can be seen from the figure, in the absence of sand, S. algae cells were evenly distributed on the sample surface (Fig. 1a). When covered with multilayer sea sand, Fig. 1b–d show a sharp decrease in the attachment of S. algae, and the attachment amount decreased successively with the reduction of sea sand particle size. In addition, compared with the bacterial attachment on the 316 SS surface when covered with a single layer of sea sand24, the bacterial attachment on the 316 SS surface covered with multilayer sea sand was significantly reduced. These results indicate that the multilayer sea sand may hinder the migration of microorganisms to the metal surface on the one hand, and on the other hand, also obstruct the migration of nutrients to the metal interface, leading to the inability of microorganisms to proliferate in large numbers on the metal surface.

The 316 SS bare metal and 316 SS covered with multilayer sea sand of different particle sizes were immersed in simulated seawater medium inoculated with S. algae for 3 days. The viability of microorganisms attached to the 316 SS surface was assessed using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM). The results are shown in Fig. 2. Green, red, and yellow represent live cells, dead cells, and partially damaged/dead cells, respectively. As seen in Fig. 2a, a large number of live cells are uniformly attached to the bare 316 SS metal surface without sand coverage. When covered with multilayer L-type sand (Fig. 2b), the number of cells attached to the 316 SS surface decreases sharply, with sporadic dead cells present on the surface. With multilayer M-type sand coverage (Fig. 2c), the number of cells attached to the 316 SS surface further decreases, and the number of dead cells attached to the surface increases further. When covered with multilayer S-type sand (Fig. 2d), very few cells are attached to the 316 SS surface, and a considerable proportion of them are dead cells. These results indicate that multilayer sea sand effectively inhibits the attachment and growth of S. algae on the 316 SS surface, exerting a stronger inhibitory effect on the transport of S. algae and substances than single-layer sea sand24. This leads to unsatisfactory adsorption and growth of S. algae on the 316 SS surface, with the inhibitory effect becoming more significant as the particle size of the sea sand decreases.

Analysis of pit depth

The 316 SS samples were immersed in different experimental systems for 7 days, and after removing the sea sand and biofilm, the pitting corrosion on the surface of the 316 SS samples was observed and statistically analyzed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM). Figure 3 and Fig. 4 present the three-dimensional morphologies of the largest pitting corrosion under different experimental conditions. Table 1 shows the pitting parameters (maximum pitting depth, average pitting depth ± standard deviation, maximum pitting diameter, and average pitting diameter ± standard deviation) obtained from the statistical analysis. According to the results shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, and Table 1, in a sterile environment, the maximum pitting depths on the surfaces of bare 316 SS and 316 SS samples covered with L-type, M-type, and S-type sea sand were 1.2, 1.6, 2.1, and 2.9 μm, respectively. The average pitting depths ± standard deviations were 0.9 ± 0.2, 1.1 ± 0.3, 1.6 ± 0.3, and 2.5 ± 0.6 μm, respectively. The maximum pitting diameters were 3.5, 4.6, 7.3, and 13.9 μm, respectively. The average pitting diameters ± standard deviations were 3.2 ± 0.3, 4.1 ± 0.5, 6.5 ± 0.8, and 13.1 ± 0.8 μm, respectively. This indicates that in a sterile environment, sea sand promotes pitting corrosion on 316 SS, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the more severe the pitting corrosion. However, in a bacterial environment, the maximum pitting depths were 9.6, 5.3, 4.1, and 3.6 μm, respectively. The average pitting depths ± standard deviations were 8.9 ± 0.7, 4.9 ± 0.4, 3.7 ± 0.4, and 2.9 ± 0.7 μm, respectively. The maximum pitting diameters were 40.3, 29.9, 22.6, and 17.8 μm, respectively. The average pitting diameters ± standard deviations were 38.7 ± 1.6, 28.8 ± 1.1, 21.7 ± 0.9, and 16.8 ± 1.0 μm, respectively. This suggests that, on the one hand, S. algae promote pitting corrosion on 316 SS both with and without a sea sand layer. On the other hand, multilayer sea sand inhibits the pitting corrosion caused by S. algae on 316 SS, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the stronger the inhibition.

Composition analysis of passivation film

Figure 5 presents the distribution of Fe, Cr, and O element contents in the passive film formed on the surface of 316 SS under different experimental conditions, as measured by XPS, plotted against sputtering time (representative thickness). As seen from the figure, the concentration of chromium in the passive film on the 316 SS surface is higher in the bacterial environment compared to the sterile environment. This is primarily attributed to the preferential dissolution of iron catalyzed by S. algae, leading to the accumulation of chromium. Literature28,29 indicates that the relative thickness of the passive film can be determined by using 50% of the maximum oxygen content. Therefore, the sputtering time indicated by the “squares” in Fig. 5 can be used to compare the relative thickness of the passive films. The corresponding sputtering times for each experimental condition are listed in Table 2. It can be observed that, under sterile conditions, the thickness of the passive film on 316 SS covered with sea sand is reduced compared to that without sea sand coverage, and the smaller the sea sand particle size, the thinner the passive film. In the bacterial environment, the thickness of the passive film on 316 SS covered with sea sand is increased compared to that without sea sand coverage, and the smaller the sea sand particle size, the thicker the passive film. Furthermore, regardless of the presence or absence of sea sand or the particle size of the sea sand, the thickness of the passive film in the bacterial environment is less than that in the sterile environment, and as the sea sand particle size decreases, the thickness of the passive film on 316 SS in both sterile and bacterial environments gradually converges. This is entirely consistent with the pattern presented by the pitting statistics parameters shown in Table 1, indicating a correspondence between the thickness of the passive film and the size of the pitting corrosion pits.

The surface of 316 SS exhibited four distinct states of marine sand coverage: “(a, b) uncovered, and covered with (c, d) L-type, (e, f) M-type, (g, h) S-type sand. The simulated seawater medium presented two conditions concerning S. algae inoculation: (a, c, e, g) non-inoculated and (b, d, f, h) inoculated with bacteria. The samples were immersed for 7 days.

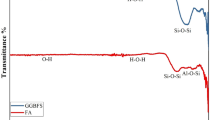

Figure 6 presents the high-resolution XPS spectra of Cr 2p3/2 for 316 SS immersed in simulated seawater medium under different conditions for 7 days. In a sterile environment, the Cr 2p3/2 XPS spectrum can be resolved into three distinct peaks with binding energies (B.E.s) of 573.8, 575.7, and 577.1 eV, attributed to Cr, Cr2O3, and Cr(OH)3, respectively. However, in a bacterial environment, the Cr 2p3/2 XPS spectrum can be resolved into four distinct peaks with B.E.s of 573.8, 575.7, 577.1, and 579.0 eV, attributed to Cr, Cr2O3, Cr(OH)3, and CrO3, respectively, which is consistent with the literature29,30,31,32,33,34,35. This indicates that the presence of S. algae leads to the formation of CrO3 in the passive film. It has been reported that P. aeruginosa and sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) exhibit similar bacterial activity30, promoting the formation of Cr(VI), which makes the passive film more soluble and accelerates the removal of chromium from the 316 SS surface, thereby promoting pitting corrosion of 316 SS36,37. Based on the peak fitting results shown in Fig. 6, the relative atomic percentage contents of chromium species in the passive film were calculated and listed in Table 3. It can be seen that in a sterile seawater environment, the Cr2O3/Cr(OH)3 ratio in the passive film of 316 SS covered with sea sand is lower than that of bare 316 SS without sand, and further decreases with decreasing sea sand particle size. However, in a bacterial environment, the Cr2O3/Cr(OH)3 ratio in the passive film of 316 SS covered with sea sand is higher than that of bare 316 SS, and further increases with decreasing sea sand particle size. It is generally believed that Cr2O3 has better corrosion resistance than Cr(OH)331. The higher the Cr2O3 content in the passive film, the more stable and protective the passive film is. Obviously, the above results are in good agreement with the corrosion behavior of 316 SS reflected by the passive film thickness and pitting statistical parameters.

The surface of 316 SS exhibited four distinct states of marine sand coverage: (a, b) uncovered, and covered with (c, d) L-type, (e, f) M-type, (g, h) S-type sand. The simulated seawater medium presented two conditions concerning S. algae inoculation: (a, c, e, g) non-inoculated and (b, d, f, h) inoculated with bacteria. The samples were immersed for 7 days.

Electrochemical analyses

Figure 7 presents the variation of OCP of 316 SS in simulated seawater medium over time under different experimental conditions. As shown in the figure, in a sterile seawater environment, the OCP of 316 SS decreases when covered with sea sand compared to that without a sand layer, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the lower the OCP. However, in a bacterial environment, the OCP of 316 SS increases when covered with sea sand compared to that without a sand layer, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the higher the OCP. For 316 SS with no sand cover or covered with sea sand of the same particle size, the OCP in the bacterial environment is lower than that in the sterile environment, and as the particle size of the sea sand decreases, the OCP of 316 SS in both sterile and bacterial environments gradually converges. It can be seen that the variation pattern of OCP is consistent with the thickness pattern of the passive film obtained from XPS tests, indicating a good correlation between the two. This suggests that in a sterile seawater environment, the coverage of sea sand leads to slower growth of the passive film and a decrease in OCP; whereas in a bacterial environment, the coverage of sea sand reduces the extent of S. algae coverage on the surface of 316 SS, weakens the inhibition of passive film growth, and results in an increase in OCP.

Figure 8 presents the polarization curves of 316 SS in simulated seawater medium under different experimental conditions. As shown in the figure, in a sterile environment, the cathodic region exhibits a cathodic reduction reaction of oxygen (the equilibrium electrode potential in this study system is 0.472 VSCE). This reaction is controlled by charge transfer in the potential region deviating from the OCP and by limiting diffusion in the lower potential region (−0.5 VSCE). The limiting diffusion current density of oxygen decreases with the reduction of sea sand particle size, indicating that sea sand has a blocking effect on oxygen transport, and the smaller the sea sand particle size, the stronger the blocking effect. When the potential is below −0.8 VSCE, a hydrogen evolution reaction controlled by charge transfer begins to occur (the equilibrium electrode potential in this study system is −0.734 VSCE). In a bacterial environment, the cathodic region does not exhibit characteristics of oxygen reduction controlled by limiting diffusion. In the potential region deviating from the open-circuit potential (OCP ~ −0.8 VSCE), possible processes at the cathode include: (1) a transition from oxygen reduction controlled by charge transfer to hydrogen evolution reaction controlled by charge transfer, (2) S. algae taking electrons at the cathode for intracellular metabolism before transitioning to the hydrogen evolution reaction, and (3) S. algae catalyzing the cathodic reduction of O2, shifting from limiting diffusion control to charge transfer control. When the potential is below −0.8 VSCE, a hydrogen evolution reaction controlled by charge transfer begins to occur. For the biofilm/metal interface region, bacterial respiration consumes a portion of O2; the process of Fe oxidation to Fe2+ and subsequent oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ by O2 also consumes a portion of O2. Additionally, microbial respiration can directly provide electrons to Fe3+ and reduce it to Fe2+, which is then oxidized back to Fe3+ by residual oxygen. This repeated cycle can lead to a further reduction in dissolved oxygen. Under the combined effects of these three processes, anaerobic zones can form within the biofilm/metal interface. Literature38,39,40,41 has used microelectrodes to test the dissolved oxygen content within biofilms, and the results also support that the metal interface is in an anaerobic zone. Therefore, in a bacterial environment, it is more likely that S. algae take electrons at the cathode for intracellular metabolism before transitioning to the hydrogen evolution reaction in the potential region deviating from the open-circuit potential.

The pitting potential (Eb) and corrosion potential (Ecorr) obtained from Fig. 8 are listed in Table 4. In a sterile seawater environment, compared to 316 SS without a sand layer, the Eb and Ecorr of 316 SS covered with multilayer sea sand are reduced to a certain extent; moreover, as the particle size of the sea sand decreases, the Eb and Ecorr decrease further in sequence. This indicates that in a sterile environment, sea sand promotes the pitting corrosion of 316 SS to some extent. In a bacterial environment, compared to 316 SS without a sand layer, the Eb and Ecorr of 316 SS covered with sea sand are slightly increased, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the higher the Eb and Ecorr. This suggests that in a bacterial environment, on the one hand, the Eb and Ecorr of 316 SS are significantly lower than those in a sterile environment, indicating that S. algae significantly promotes the pitting corrosion of 316 SS. On the other hand, sea sand has a certain inhibitory effect on the acceleration of pitting corrosion caused by Shewanella to 316 SS.

Figure 9 presents the Nyquist plot of EIS for 316 SS in simulated seawater medium under different experimental conditions. As seen from the figure, the impedance of 316 SS exhibits distinct capacitive characteristics42. According to the polarization curves shown in Fig. 8, 316 SS is in a self-passivating state under all experimental conditions, with a passivation film formed on its surface. Therefore, the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 10 is used to fit the impedance data of the corresponding experimental system, and the fitting results are listed in Table 5. Herein, Rs, Rs-b, Rpf, and Rct represent the resistance of solution, sand and/or biofilm (sand, biofilm or mixture of sand and biofilm), passive film and charge transfer, respectively. The polarization resistance Rp can reflect the susceptibility of metal electrodes to corrosion42,43, and its value is the sum of Rs-b, Rpf, and Rct. CPEs-b, CPEpf and CPEdl represent the capacitive properties of sand and/or biofilm, passive film and electric double layer, respectively; Ysb, Ypf and Yct are the conductance of sand and/or biofilm, passive film and electric double layer; nsb, npf and ndl are the coefficients of dispersion for sand and/or biofilm, passive film and electric double layer, which are related to the roughness of the electrode surface.

The surface of 316 SS exhibited four distinct states of marine sand coverage: (a, e) uncovered, and covered with (b, f) L-type, (c, g) M-type, (d, h) S-type sand. The simulated seawater medium presented two conditions concerning S. algae inoculation: (a–d) non-inoculated and (e–h) inoculated with bacteria. The samples were immersed for 7 days.

As can be seen from Table 5, the values of Rs-b are relatively small under various experimental conditions, indicating that the multilayer sea sand and S. algae have little resistance to the electrode reaction. The polarization curves and XPS results show that both sea sand and S. algae have significant effects on the formation and properties (such as thickness and composition) of the 316 SS passive film: multilayer sea sand reduces the concentration of dissolved oxygen at the electrode interface, inhibiting the growth of the passive film, while S. algae can directly extract electrons from the passive film to oxidize Cr(III) to Cr(VI), leading to the destruction of the passive film24. This means that the environmental changes brought about by multilayer sea sand and biofilm have a significant time-dependent influence on the film resistance of the passive film, and the changes in film resistance caused by this influence will further affect the corrosion rate. Therefore, even though the Rs-b values are small, the damage to stainless steel under different biofilm-sand environmental conditions can still be discussed through changes in Rpf, Rct, and Rp. To facilitate the explanation of the effects of bacteria and sea sand on the passivation evolution behavior of 316 SS, Rpf, Rct, and Rp are plotted in Fig. 11. As can be seen from the figure, in a sterile environment, the Rpf of bare 316 SS and 316 SS covered with L-type sea sand gradually increases during immersion, while the Rpf of 316 SS covered with M- and S-type sea sand first decreases and then gradually stabilizes. Covering 316 SS with sea sand results in a decrease in Rpf, and as the particle size of the sea sand decreases, Rpf gradually decreases (Fig. 11a). In a bacterial environment, the Rpf of bare 316 SS rapidly decreases and then slowly increases during immersion, while the Rpf of 316 SS covered with different particle sizes of sea sand remains relatively stable during immersion. In addition, in a bacterial environment, covering 316 SS with sea sand significantly increases Rpf, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the greater the Rpf (Fig. 11b). Compared with a sterile environment, the Rpf of 316 SS in a bacterial environment is reduced. These results indicate that in a sterile environment, sea sand has a certain destructive effect on the 316 SS passive film, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the stronger the destructive effect. However, in a bacterial environment, sea sand enhances the ability of 316 SS to maintain passivity.

In a sterile environment, the Rct and Rp of 316 SS covered with sea sand are lower than those of bare 316 SS, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the lower the Rct and Rp. This indicates that sea sand promotes the corrosion of 316 SS to some extent in a sterile environment. However, in a bacterial environment, the Rct and Rp of 316 SS covered with sea sand are higher than those of bare 316 SS, and the smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the higher the Rct and Rp. This suggests that in a bacterial simulated environment, sea sand inhibits the corrosion of 316 SS caused by S. algae to some extent. Corresponding to bare 316 SS or 316 SS covered with sea sand of the same particle size, the Rct and Rp in a bacterial environment are lower than those in a sterile environment. However, as the particle size of the sea sand decreases, the Rct and Rp of 316 SS in sterile and bacterial environments gradually converge.

Discussion

In a sterile simulated seawater medium, the multilayer sea sand covering on 316 SS resulted in a decrease in the cathodic limiting diffusion current density, and the smaller the particle size of the multilayer sea sand, the lower the cathodic limiting diffusion current density (Fig. 8a). This indicates that the multilayer sea sand hinders oxygen diffusion, and the smaller the particle size, the stronger the hindrance, leading to a lower concentration of dissolved oxygen reaching the stainless steel surface. Under open circuit potential, the cathodic process is controlled by the charge transfer process of oxygen reduction, which may cause a decrease in the pH at the surface of 316 SS. Consequently, it inhibits the cathodic process but accelerates the anodic process, resulting in a decrease in the pitting potential of 316 SS (Table 4), an increase in the size of pitting corrosion pits, and a reduction in corrosion resistance. This is consistent with the influence pattern of single-layer sea sand particle size on the corrosion behavior of 316 SS24.

In a bacterial-containing simulated seawater medium, S. algae significantly reduced the dissolved oxygen concentration in the solution24, and even created anaerobic zones at the metal interface beneath the biofilm38,39,40,41, which is detrimental to the growth of the passive film (Table 2). Furthermore, S. algae utilizes H2 in the anaerobic zone beneath the biofilm10 for respiration, generating H+ 20, which further leads to the acidification of the local environment within the biofilm, making the passive film more susceptible to damage. Combined with XPS results, the presence of CrO3 in the passive film of 316 SS under bacterial conditions suggests that S. algae oxidizes trivalent Cr compounds to hexavalent Cr compounds24, thereby thinning the passive film and reducing its corrosion resistance. The combined effects of these factors are the main reasons for the significant decrease in the pitting potential of 316 SS (Table 4), the marked increase in pitting pit size, and the substantial reduction in the corrosion resistance of 316 SS caused by S. algae.

Compared to the corrosion of 316 SS in sand-free and bacteria-free seawater, both multilayer sea sand and S. algae promoted the corrosion of 316 SS, with S. algae accelerating corrosion to a much greater extent than multilayer sea sand of different particle sizes. However, when multilayer sea sand and S. algae were present simultaneously, they did not synergistically accelerate the corrosion of 316 SS; instead, the corrosion rate was intermediate between that of the system with only S. algae and that with only multilayer sea sand. This was primarily because multilayer sea sand significantly reduced the effective attachment of S. algae to the surface of 316 SS, and this reduction trend increased with decreasing particle size of the multilayer sea sand (Fig. 1), thereby inhibiting the corrosion of 316 SS. This corrosion behavior was markedly different from that observed with single-layer sea sand24, possibly due to the fact that single-layer sea sand of different particle sizes not only affected the adsorption behavior of S. algae on the surface of 316 SS but also altered the local pH value on the surface, leading to distinct corrosion behaviors under single-layer sea sand coverage compared to multilayer sea sand environments of different particle sizes.

In conclusion, the effects of multilayer sea sand particles of varying sizes and S. algae on the corrosion mechanism of 316 SS were investigated. The conclusions are drawn as follows:

-

1.

Multilayer sea sand with different particle sizes hinders the diffusion of dissolved oxygen to the metal interface, inhibits the growth of the passive film, and thus promotes the corrosion of 316 SS.

-

2.

S. algae promotes the corrosion of 316 SS by consuming dissolved oxygen, facilitating local acidification, and accelerating the destruction of the passive film, and its accelerating effect on the corrosion of 316 SS is much stronger than that of multilayer sea sand.

-

3.

Multilayer sea sand significantly reduces the effective attachment of S. algae on the surface of 316 SS, thereby effectively attenuating the corrosion-accelerating effect of S. algae on 316 SS. The smaller the particle size of the sea sand, the stronger the inhibitory effect, and the more the corrosion rates of 316SS in sterile and bacterial environments converge.

-

4.

The influence of sea sand particle size on the MIC behavior of 316 SS under deposit is closely related to the number of sea sand layers. When covered with multiple layers of sea sand, the smaller the sea sand particle size, the lower the MIC rate of 316 SS under deposit; whereas, when covered with a single layer of sea sand, the MIC rate of 316 SS under deposit exhibits a maximum value as the sea sand particle size decreases.

Methods

Preparation of steel samples and sand

The stainless steel used in this study is 316 SS produced by Shanxi Taigang Stainless Steel Co., Ltd. of Taiyuan Iron & Steel (Group) Co., Ltd. Its chemical composition is listed in Table 6. The bulk 316 SS sheets were processed into 10 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm specimens by wire cutting, and then polished with silicon carbide paper of different grit sizes up to 1000#. Copper wires were welded on the back and the specimens were encapsulated with epoxy resin, leaving an area of 1 cm2 as the working area.

The particle size of ordinary iron ore and coal in contact with the cargo hold ranges from 0.6 mm to 2.4 mm44. The typical particle size for sand is between 0.05 mm and 2 mm, while silt ranges from 0.002 mm to 0.05 mm45. Studies46,47 have categorized sand with a particle size less than 2 mm into four or three grades for experimentation. For this study, sediment was collected from the tidal area of a shallow sea located in Qingdao, China, at low tide. The sediment was then drained and dried in an oven. To acquire three distinct sand fractions with roughly equal volumes, a screening process was implemented. Standard sieves with apertures of 5 mesh (4000 μm), 8 mesh (2500 μm), and 20 mesh (900 μm) were utilized to separate the sand into three particle size categories: 4000 to 2500 μm (denoted as L), 2500 to 900 μm (denoted as M), and below 900 μm (denoted as S).

Bacterial culture and sterilization method

S. algae MCCC 1A11468 was purchased from the Marine Culture Collection of China (MCCC). In this study, S. algae was cultivated using the standard 2216E medium, the composition of which is presented in Table 7. Bacteria were inoculated in the medium and placed in a constant temperature shaker at 37 °C and incubated with shaking at 150 rpm for 24 hours until the bacteria reached the logarithmic growth phase. After being cultured and subcultured twice, it was utilized for electrochemical and immersion experiments. The initial concentration of the bacteria was 106 cells/L, and the cultivation temperature was 37 °C.

The simulated seawater medium used in electrochemical experiments and immersion tests is an artificial simulated seawater as shown in Table 8, supplemented with 1 g/L peptone and 0.2 g/L yeast extract. The artificial simulated seawater was prepared using the ASTM D1141-1998 (2013) standard method, and the pH was adjusted to 8.2 with diluted NaOH solution.

The items including Standard 2216E culture medium, simulated seawater culture medium, and electrolytic cells need to be autoclaved at 121 °C for a duration of 20 minutes. Both electrochemical and immersion samples should be immersed in 75% ethanol for a minimum of 1 h, followed by exposure to ultraviolet light for at least 1 h.

Biofilm characterization

To observe the biofilm formed on the sample surface, the samples, which had been immersed in simulated seawater medium containing S. algae at 37 °C for 3 days, were fixed with 2.5% (volume fraction) glutaraldehyde solution at 4 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, they were dehydrated with a series of ethanol solutions/absolute ethanol at volume fractions of 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100% for 10 min each. After drying, a layer of gold film was sputtered onto the sample surface to enhance the conductivity of the biofilm. The biofilm was then observed using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM).

The viability and thickness of the adherent cells were assessed using a live/dead cell staining method. The 316 SS coupons were exposed to artificial simulated seawater medium with an initial S. algae concentration of 106 cells/mL for 3 days. The coupons were then removed and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, the air-dried coupons were immersed in 1 mL of PBS and incubated with 25 μL each of SYTO-9 and PI dyes (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) for 20 min. SYTO-9 and PI are green and red fluorescent dyes, respectively, with different abilities to penetrate bacteria. When used alone, SYTO-9 stains all bacteria regardless of membrane integrity, while PI only enters bacteria with damaged membranes, causing a reduction in SYTO-9 fluorescence. Therefore, live and dead bacteria can be distinguished based on membrane integrity. SYTO-9 dye emits green fluorescence at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm, used to detect live cells, while PI dye emits red fluorescence at an excitation wavelength of 559 nm, used to stain dead cells. The viability of the bacteria adherent to the coupons was observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (Zeiss Imager.Z2). For each experimental condition, three parallel coupons were set up to ensure the accuracy of the experimental data.

Surface analysis

After immersing 316 SS specimens in simulated seawater medium at 37 °C under different conditions for 7 days, the biofilms and corrosion products on the surface were removed using an eraser and an ultrasonic bath (with anhydrous ethanol). The pit depth was measured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Zeiss Imager.Z2). For each experimental condition, three parallel specimens were prepared, and a total of ten areas, each with an area of 0.1 mm², were randomly selected from the three specimens to calculate the maximum and average pit depths. Additionally, after immersing 316 SS specimens in simulated seawater medium at 37 °C under different experimental conditions for 7 days, the samples were removed, gently rinsed with distilled water, dried in a nitrogen stream, and finally subjected to XPS analysis (ESCALAB250 surface analysis system, Thermo VG, Waltham, MA, USA).

Electrochemical testing

The electrochemical experiments were conducted using a conventional three-electrode system, as illustrated in Fig. 12. The reference electrode was a saturated calomel electrode (SCE), the counter electrode was a pure platinum plate with dimensions of 10 mm × 10 mm × 0.3 mm, and the working electrode was a 316 SS sample encapsulated in epoxy resin with an exposed area of 1 square centimeter. A 200 ml simulated seawater medium solution was placed in a 500 ml electrolytic cell, and the electrodes were fixed in the middle of the solution (in the vertical direction). A hole with a diameter of 16 mm was retained at the top of the electrolytic cell to serve two purposes: firstly, to add sea sand of different particle sizes into the electrolytic cell through the hole using a funnel (the sea sand was filled to 2 cm above the upper edge of the working electrode), and secondly, to seal the hole with a 0.22 μm microporous membrane filter during the experiment to ensure air diffusion into the electrolytic cell and prevent external bacteria from entering. The electrochemical workstation used was the Gamry Reference 600 Plus. Open circuit potential (OCP), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were performed on the electrochemical samples daily for 7 days. The frequency range for the EIS test was 10−2 ~ 105 Hz, with a perturbation amplitude of 10 mV, and the EIS data was analyzed using ZSimpwin 3.6 software. Potentiodynamic polarization curves were tested on the 7th day, with scans in both the cathodic and anodic directions from the OCP, at a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s. Each set of electrochemical experiments was repeated at least three times to ensure the reliability of the experimental results.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Obot, I. B. Under-Deposit Corrosion on Steel Pipeline Surfaces: Mechanism, Mitigation and Current Challenges. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 7, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-021-00485-9 (2021).

Hoseinieh, S. M., Homborg, A. M., Shahrabi, T., Mol, J. & Ramezanzadeh, B. A Novel Approach for the Evaluation of Under Deposit Corrosion in Marine Environments Using Combined Analysis by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Electrochemical Noise. Electrochim. Acta 217, 226–241, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.08.146 (2016).

Standlee, S., Efird, K. D. & Spiller, D. Under Deposit Corrosion From Iron Sulfide. Paper presented at the CORROSION 2011, Houston, Texas, March, Paper Number: NACE-11266 (2011)

Kagarise, C., Vera, J. R. & Eckert, R. B. The Importance of Deposit Characterization in Mitigating UDC and MIC in Dead Legs. Paper presented at the CORROSION 2017, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, March, Paper Number: NACE-2017-9128 (2017)

Dubiel, M., Hsu, C. H., Chien, C. C., Mansfeld, F. & Newman, D. K. Microbial iron respiration can protect steel from corrosion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 1440–1445 (2002).

Little, B. et al. The role of biomineralization in microbiologically influenced corrosion. Biodegradation 9, 1–10 (1998).

DawoodBrozel Corrosion-enhancing potential of Shewanella putrefaciens isolated from industrial cooling waters. J. Appl Microbiol 84, 929–936 (1998).

De Windt, Wim, Boon, Nico, Siciliano, StevenD. & Verstraete, Willy Cell density related H2 consumption in relation to anoxic Fe(0) corrosion and precipitation of corrosion products by Shewanella oneidensis MR‐1. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 1192–1202 (2003).

McLeod, E. S. et al. Isolation and Identification of Sulphite- and Iron Reducing, Hydrogenase Positive Facultative Anaerobes from Cooling Water Systems. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21, 297–305 (1998).

Schütz, M. K. et al. Combined geochemical and electrochemical methodology to quantify corrosion of carbon steel by bacterial activity. Bioelectrochemistry 97, 61–68 (2014).

Schütz, M. K., Schlegel, M. L., Libert, M. & Bildstein, O. Impact of iron-reducing bacteria on the corrosion rate of carbon steel under simulated geological disposal conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7483–7490 (2015).

Jiang, Z., Shi, M. & Shi, L. Degradation of organic contaminants and steel corrosion by the dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganisms Shewanella and Geobacter spp. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 147, 104842 (2020).

Jo, Philips et al. A Novel Shewanella Isolate Enhances Corrosion by Using Metallic Iron as the Electron Donor with Fumarate as the Electron Acceptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e01154–18 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Synergistic effect of chloride ion and Shewanella algae accelerates the corrosion of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 71, 177–185 (2021).

Kalnaowakul, P., Xu, D. & Rodchanarowan, A. Accelerated Corrosion of 316L Stainless Steel Caused by Shewanella algae Biofilms. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 2185–2192 (2020).

Wurzler, N. et al. Abundance of Fe(III) during cultivation affects the microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) behaviour of iron reducing bacteria Shewanella putrefaciens. Corros. Sci. 174, 108855 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. Sharing riboflavin as an electron shuttle enhances the corrosivity of a mixed consortium of Shewanella oneidensis and Bacillus licheniformis against 316L stainless steel. Electrochim. Acta 316, 93–104 (2019).

Miller, R. B., Lawson, K., Sadek, A., Monty, C. N. & Senko, J. M. Uniform and Pitting Corrosion of Carbon Steel by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 under Nitrate-Reducing Conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e00790–18 (2018).

Miller, R. B. et al. Use of an electrochemical split cell technique to evaluate the influence of shewanella oneidensis activities on corrosion of carbon steel. PLoS ONE 11, e0147899 (2016).

Konishi, Y. et al. Microbial deposition of gold nanoparticles by the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella algae. Electrochim. Acta 53, 186–192 (2007).

Herrera, L. K. & Videla, H. A. Role of iron-reducing bacteria in corrosion and protection of carbon steel. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 63, 891–895 (2009).

Bowerman, C., Lucus, B. & Mattox, M. Under Deposit Corrosion Mitigation And Ili Accuracy Improvement In A Sour Crude Gathering And Transportation System Accomplished Using Novel Chemistry. Paper presented at the CORROSION 2012, Salt Lake City, Utah, March, Paper Number: NACE-2012-1113.(2012)

Smart, J. & Pickthall, T. W. Internal Corrosion Direct Measurement Enhances Pipeline Integrity. Paper presented at the CORROSION 2004, New Orleans, Louisiana, March, Paper Number: NACE-04177.(2004)

Shen, Y. et al. Influence of sea sand and Shewanella algae on the corrosion behavior of 316 stainless steel in marine environment. Corros. Sci. 235, 112200 (2024).

Wang, X. & Melchers, R. E. Long-term under-deposit pitting corrosion of carbon steel pipes. Ocean Eng. 133, 231–243 (2017).

Machuca, L. L., Lepkova, K. & Petroski, A. Corrosion of carbon steel in the presence of oilfield deposit and thiosulphate-reducing bacteria in CO2 environment. Corros. Sci. 129, 16–25 (2017).

Liu, H., Zhong, X., Liu, H. & Frank Cheng, Y. Microbiologically-enhanced galvanic corrosion of the steel beneath a deposit in simulated oilfield-produced water containing Desulfotomaculum nigrificans. Electrochem. Commun. 90, 1–5 (2018).

Mischler, S., Vogel, A., Mathieu, H. J. & Landolt, D. The chemical composition of the passive film on Fe·24Cr and Fe·24Cr·11Mo studied by AES, XPS and SIMS. Corros. Sci. 32, 925–944 (1991).

Jiang, R., Wang, Y., Wen, X., Chen, C. & Zhao, J. Effect of time on the characteristics of passive film formed on stainless steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 412, 214–222 (2017).

Xu, D. et al. Accelerated corrosion of 2205 duplex stainless steel caused by marine aerobic Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Bioelectrochemistry 113, 1–8 (2017).

Yuan, S. J. & Pehkonen, S. O. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of 304 stainless steel by aerobic Pseudomonas NCIMB 2021 bacteria: AFM and XPS study. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 59, 87–99 (2007).

Wang, K., Wang, J. & Hu, W. Evaluation of temperature effect on the corrosion process of 304 stainless steel in high temperature water with electrochemical noise. Mater. Des. 82, 155–163 (2015).

Jung, R.-H., Tsuchiya, H. & Fujimoto, S. XPS characterization of passive films formed on Type 304 stainless steel in humid atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 58, 62–68 (2012).

Shintani, D. et al. XPS studies on passive film formed on stainless steel in a high-temperature and high-pressure methanol solution containing chloride ions. Corros. Sci. 50, 2840–2845 (2008).

Wu, C. et al. Influence of crevice width on sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB)-induced corrosion of stainless steel 316L. Corros. Commun. 4, 33–44 (2021).

Antony, P. J., Raman, R. S., Raman, R. & Kumar, P. Role of microstructure on corrosion of duplex stainless steel in presence of bacterial activity. Corros. Sci. 52, 1404–1412 (2010).

Chen, G. & Clayton, C. R. The Influence of Sulfate‐Reducing Bacteria on the Passivity of Type 317L Austenitic Stainless Steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145, 1914–1922 (1998).

Lewandowski, Z., Lee, W. C., Characklis, W. G. & Little, B. Dissolved Oxygen and pH Microelectrode Measurements at Water-Immersed Metal Surfaces. Corrosion 45, 92–98 (1989).

Costerton, J. W., Lewandowski, Z., Caldwell, D. E., Korber, D. R. & Lappin-Scott, H. M. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49, 711–745 (1995).

Lee, A. K. & Newman, D. K. Microbial iron respiration: impacts on corrosion processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 62, 134–139 (2003).

Kiamco, M. M., Atci, E., Mohamed, A., Call, D. R. & Beyenal, H. Hyperosmotic Agents and Antibiotics Affect Dissolved Oxygen and pH Concentration Gradients in Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e02783–16 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Beneficial effect of heat input to improve microbial corrosion resistance of welded joint in X80 steel pipeline. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 223, 217–234 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Atmospheric corrosion of tin coating on T2 copper in Xiangtan, China. Corros. Commun. 16, 52–60 (2024).

Gardiner, C. & Melchers, R. Corrosion of mild steel by coal and iron ore. Corros. Sci. 44, 2665–2673 (2002).

Petersen, R. B. & Melchers, R. E. Development of pitting corrosion for mild steel exposed to particulate media and natural and nutrient-dosed seawaters. Corrosion 79, 121–131 (2023).

Burns, R. M. & Salley, D. J. Particle size as a factor in the corrosion of lead by soils 1. Ind. Eng. Chem. 22, 293–297 (1930).

Jizhou, D. et al. Corrosion of mild steel in different granularity seabed sediment saturated with seawater. Mater. Corros. 53, 845–849 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52201094, U2106206), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0907300), Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program (XLYC2203137), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515240066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and R.M. conceived and planned the experiments. Y.S. carried out the experiments. C.W. contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.S. writing the manuscript. R.M. reviewed and helped write the manuscript. J.D. and D.X. got funding and supervised the work. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Ma, R., Wang, C. et al. Influence of multilayer sea sand and Shewanella algae on the corrosion behavior of 316 SS. npj Mater Degrad 9, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00575-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00575-w