Abstract

The HHSAMed 5A06 deposition, produced through hybrid heat-source solid-state additive manufacturing (HHSAM), demonstrates a more uniform microstructure and enhanced microhardness, with a measured value of 89.9 HV0.5. Additionally, it exhibits superior mechanical properties, including increased yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation (EL) in both the longitudinal direction (YS-238.3 MPa, UTS-358.1 MPa, EL-27.5%) and the building direction (YS-184.0 MPa, UTS-324.5 MPa, EL-25.7%).The heat-source enhances the material flow behavior and the interlayer bonding strength among the stacking layers, excluding the effects of grain refinement and precipitate strengthening. It demonstrates superior corrosion resistance relative to the AFSD deposition and 5A06 feedstock, attributed to the most stable passive film, a greater concentration of Al6(Fe,Mn) and the lack of Al3Mg2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

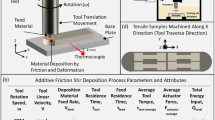

Addition friction stir deposition (AFSD), an innovative solid-state metal additive manufacturing (AM) technology, has been extensively utilized to deposit aluminum1,2, magnesium3, Inconel 6254,5 and copper alloys6. A feedstock is applied as feed material to a hollow tool operating at a set rotation speed, resulting in plastic deformation due to frictional heat at the interface, followed by the construction of the required height through a layer-by-layer stacking process. It may offer distinct benefits, including reduced oxidation, refined equiaxed grains, absence of residual stress-induced cracking and facilitation in composite development7,8.

Recently, the 5A06 alloy (5-series aluminum alloys, Al-Mg alloy), characterized by its lower density, better mechanical properties, and excellent corrosion resistance, has been widely applied in the AM fields and marine engineering. However, due to the material being a non-heat treatment element, its mechanical properties could not be improved by heat treatment process9. It has been confirmed that the corrosion of 5-series aluminum alloy in seawater showed local corrosion characteristics in the early stage while uniform corrosion in the later stage. The local corrosion primarily manifests as pitting corrosion, crevice corrosion and the inter-crystalline corrosion10. Consequently, it is necessary to effectively improve the corrosion resistance of 5A06 deposition while concurrently maintaining its mechanical properties. The pitting resistance of the AFSDed 5A06 has been enhanced thanks to the diminishment of the secondary phase11 during the AFSD process, successfully disperses the phase structure and dissolves a portion of the precipitated phase, hence enhancing the corrosion resistance of the component. Neverteless, it does not concurrently preserve the requisite mechanical strength. Therefore, it is imperative to devise an effective strategy to optimize the precipitation phase distribution, ensuring a simultaneous and stable balance between strength and corrosion performance.

The viability of the technology known as hybrid heat-source solid-state additive manufacturing (HHSAM), which employs induction heating to deposit the uniform Al 6061 component with the enhanced overall performance, has been demonstrated12. The induction-heating is a potential candidate to obtain auxiliary heat source effect with the benefits of being cost-effective, high stability and less environment sensitivities. This investigation further verifies the efficiency of enhancing the mechanical and electrochemical properties of the fabricated 5A06 specimen. The thermal evolution and the plastic deformation mechanism are directly examined using the in-situ monitoring data, including the real-time temperature, force and torque collected from the self-developed in-situ process monitoring kit. Simultaneously, the microstructure, microhardness, tensile properties and electrochemical behaviors of the HHSAM deposition in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution have also been compared to those of the 5A06 feedstock and the AFSDed deposition. The findings of the present work serve as a valuable reference for the solid-state additive manufacturing of 5-series aluminum alloys and offer a novel approach for obtaining high-quality 5A06 deposition.

Results

Monitoring data analysis

The development of real-time signals, including temperature (T), upsetting force (Fups), spindle force (Fspi), spindle torque (Mspi) and bending (Fbend), gathered by the self-developed in-situ process monitoring kit during the fabricating process are exhibited in Fig. 1. All the signals initially exhibit an increasing trend when the hollow tool head penetrates the substrate while rotating, akin to the plunging stage in the friction stir welding (FSW) process12. The initial feedstock feeding process involves the extrusion of softened material, which is generated by friction heat, from the hollow tool. The softened material is then deposited onto the substrate to improve metallurgical bonding between the deposited layers. This results in an increase in all measured parameters, with particular emphasis on Fups (Fig. 1b) and Mspi (Fig. 1c). Subsequently, all the signals stabilize and attain the steady state of the producing process. The stable part is utilized for comparing and assessing the difference between AFSD and HHSAM deposition to prevent the inclusion of data associated with the transient portion of the signal, with the relevant average values compiled in Table 1.

The effectiveness of the additional induction heating could be verified by the observed temperature progression (Fig. 10), where the initial T corresponds to the pre-determined value of the heating device. The HHSAM exhibits a higher T (253.9 °C) at the steady-state deposition condition compared to the AFSD (213.6 °C), meaning that the induction-heat makes up the previous insufficient heat input generated by the severe plastic deformation only. The elevated Fups of HHSAM (20.8 kN) might be significantly associated with to the heating process. The rise in temperature during HHSAM results in swift softening and plastic deformation of the material at the tip of the feedstock. The material flow behavior could be constrained by the hollow tool, resulting in the generation of a reaction force. The reaction force transfers to obstruction force for the feeding of feedstock. Then, the larger Fups is needed to push the feedstock to be deposited on the substrate, which is about 2.2 times larger than that of the AFSD deposition (9.4 kN).

The force exerted by the spindle (Fspi) is the resultant force in the axial direction, which consists of the positive friction force (along ‘+BD’) caused by the pushing the feedstock and the negative drag force induced by the softened material on the spindle (along ‘−BD’). As the hollow tool was firmly pressed against the deposited layer, the tool’s interface limited the flow of plastic deformation flow and compressed it to a fixed layer thickness, resulting in an upward reaction force on the tool’s interface, which subjected the spindle to be undergone to positive pressure. At the same time, the plastic deformation flow at the tip of the 5A06 feedstock generated a substantial static friction force against the inner wall of the hollow tool head during the expansion and deformation of the material. As the feedstock moved downward, leading to the hollow tool to be subjected to a downward drag force, and the spindle could be subjected to the reverse force. The synergistic impact of the aforementioned factors influences the evolutionary behavior of Fspi. For the AFSD specimens, the heat is insufficient to adequately soften the feedstock to complete plastic deformation flow, causing the positive friction force to be the main force and the positive value of Fspi (9.0 kN). While, for the HHSAM specimen, the material at feedstock tip was subjected to elevated temperature, rendering it more susceptible to plastic deformation and improving its material flow behavior. The negative drag force becomes the predominant force, with the corresponding Fspi value for HHSAM specimen being −4.4 kN (Table 1).

Additionally, the HHSAM deposition exhibits a lower Mspi (115.1 Nm) and slightly higher Fbend (4.0 kN) compared to the AFSD deposition (166.9 Nm and 3.4 kN). The use of induction heating thoroughly softens the feedstock and enhances the material flow. Simultaneously, it effectively reduces the viscosity and strain rate of the material, ultimately leading to a decrease in Mspi13. For the HHSAM specimen, the higher heat causes the material to soften and plastically deform. The softened material could be squeezed out of the hollow tool during the machining process and wrapped around the outside of the kit. On the one hand, the sufficient material flow subjects the spindle to a significant drag force (Fspi: −4.4 kN). Otherwise, since the Fbend quantifies the force applied by the extruded material on the tool during processing, elucidating the material flow behavior, the above-mentioned softened material could hinder the lateral machining (along TD) of the kit, which directly increase the value of Fbend (4.0 kN, Table 2).

Microstructure observation

Figure 2 displays the cross-sections of the deposited AFSD and HHSAM depositions, respectively. It both indicates that relatively homogenous structure devoid of pores and cracks attributable to the merits of the AFSD process. In the AFSD deposition (Fig. 2a), notable oscillations, shown by white arrows, reveal the inhomogeneity of the plastic flow during AFSD, where diminished fluidity leads to an uneven stress distribution and a comparatively weak interlayer bonding. The HHSAM deposition presents a denser interlayer structure (Fig. 2b), with each stacked layer remaining mostly linear in the TD direction. It further indicates that the softened material is consistently preserved beneath the hollow tool, thereby promoting a stable deposition process.

Figure 3 presents the EBSD results (3*3 mm2) of the depositions, together with the associated grain size distribution and the pole figures exhibiting the ideal texture. The refined equiaxed grains formed in all deposition, owing to the dynamic recrystallization (DRX). Meanwhile, and the grains orientation presents periodic distribution, each stacked layer presents a uniform and similar structure, which can be inferred that the deposited materials achieve metallurgical bonding. Both the AFSD and HHSAM depositions exhibit homogeneous equiaxed grains, owing to the heat input and the intense plastic deformation produced by the stirring hollow tool14. It is found that the average size of the 5A06 feedstock was about 21.6 ± 0.91 μm (Fig. 3c), indicating that the grain structure of the obtained specimens is significantly refined, owing to the high shear stress and serious plastic deformation15,16. Upon comparison the grain size of the two specimens, it is seen that the HHSAM exhibits marginally bigger grains (12.5 ± 1.01 μm, Fig. 3b) than those of the AFSD deposition (10.6 ± 0.47 μm, Fig. 3a). The phenomenon is attributable to the elevated degree of continuous dynamic recrystallization (CDRX) of the HHSAM specimens17. The incorporation of the induction heating process induces a greater thermal evolution, promoting CDRX and leading to the growth of grain structure.

The 5A06 feedstock has a pronounce B texture ((\(1\bar{\,1\,}1\))[1 1 0]), with a maximum texture intensity of 7.94 (Fig. 3c). The two specimens have a comparable textural pattern (Fig. 3(3)), indicating that the AFSD deposition possessed stronger shearing textures but a diminished RTc texture as compared with HHSAM specimen. According to the standard FCC ideal textures over (111) pole figures, which represent specific crystallographic orientations, it is found that the main texture components of the AFSD is A ((\(1\bar{\,1\,}1\))[1 1 0]). Nonetheless, in the HHSAM deposition, the proportion of B textures noticeably rises, with A and B textures being the predominant textures. It has been confirmed that stronger B components were produced in the friction stir welding based 6061 alloy because of the higher plastic strain18. So, the plastic flow behavior in AFSD deposition undergoes the more serious shearing deformation than HHSAM specimen. Moreover, the texture, which is related to grain recrystallization, is stronger in HHSAM specimen (texture intensity = 1.65) as compared to the AFSD deposition (texture intensity = 1.63). It has been confirmed that the higher temperature always promotes DRX19. Consequently, the texture analysis proves that the heat generation is greater in HHSAM than that in the AFSD specimen. Therefore, the interface bonding strength in HHSAM deposition is anticipated to surpass that of AFSD deposition.

The high magnification (1000X) EBSD maps and the elements distribution of the AFSD and HHSAM depositions are exhibited in Fig. 4. The angle between 2° and 15° are defined as the low-angle grain boundary (LAGBs), and the angle bigger than 15° belongs to the high-angle grain boundary (HAGBs). For the 5A06 feedstock (Fig. 4c), the fractions of the LAGBs and HAGBs are 41.7% and 58.3%, respectively. Meanwhile, it is found that the fractions of the LAGBs and HAGBs of the AFSD and HHSAM depositions are 13.2%/16.5% and 86.8%/83.5% respectively (Fig. 4(2)). The induction heating process induces enough heat input to multiply the dislocations, leading to the formation of a dislocation wall through the sliding of dislocations, which further induces the more fraction of LAGBs20,21. Besides, it has been proven that the fraction of LAGBs is tightly related to the change of dislocations, the added enough hybrid heat-source induces the movement and redistribution of the dislocations among the HHSAM specimen, leading to the higher fraction of LAGBs22.

Upon examining the EDS mapping of the specimens, it is observed that the 5A06 feedstock (Fig. 4(3)) contains two types of particles, Al3Mg2 (marked by the white arrows) and Al6(Fe,Mn) phases (marked by the red arrows). In accordance with the findings of Gao and the co-workers23, Al6(Fe,Mn) in disk shaped and Al3Mg2 in rod shaped were identified using EDS analysis and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns. For the AFSD specimen (Figs. 4(a-3)), the above particles were likewise seen, indicating that the AFSD process could not clearly change the type and the morphology of the second phase in the corresponding deposition. However, the volume fraction of those particles is reduced. The difficulty in dissolving these hard particles into the Al-based matrix during the AFSD process is due to the comparatively inadequate heat. The above second phase particles could be randomly distributed with the material flows. Different from the AFSD specimen, there are no Al3Mg2 phases induced, and only the particles with the enrichment of Al, Fe and Mn elements, i.e., Al6(Fe,Mn) phase that marked by the red arrows, are formed in the HHSAM deposition (Figs. 4(b-3)). It largely depends on the effect of temperature evolution behavior. Higher heat causes the two types of precipitates to be re-dissolved into the Al-based matrix24. Meanwhile, as proven by the finding of Machado et al. 19, the heat-treated Al-based alloy contained lower amount of Mg element, and the mobility of grain boundaries could be increased as lowering of Mg content, thereby causing the reduction of the growth rate of the Al3Mg2 phase at the grain boundaries25. Furthermore, according to the related study26, a small amount of Al3Mg2 phase were observed when the processed temperature in the range of 100 ~ 250 °C.The monitored temperature during HHSAM process is about 200 °C, but the temperature at the actual interface is higher. Hence, it could be explained that there are almost no Al3Mg2 phases among the HHSAM specimen. Besides, it is noticed that the volume fraction of the Al6(Fe,Mn) phases is increased in the HHSAM specimen. It is due to the higher heat input, Fe and Mn atoms desolation reaction from the α(Al) matrix through the reaction α(Al)′ → α(Al) + Al6(Fe,Mn)27. The synergistic effect of sufficient heat and plastic deformation is beneficial for the heterogenous nucleation of Al6(Fe,Mn) phase at the grain boundaries/ phase boundaries, leading to the enrichment of the Al6(Fe,Mn) among the HHSAM deposition. Consistent with the previous findings of Chen et al. 26, the Al6(Fe,Mn) particles, displayed in a small rod around 200 nm in size, were situated across dislocations lines and dislocation arrays in the FSWed 5A06 alloy, as observed by the TEM analysis.

Mechanical properties

Figure 5 exhibits the microhardness distribution mapping of the 5A06 feedstock and the depositions. In comparison to the 5A06 feedstock (88.1 ± 0.7 HV0.5), the deposited samples exhibit the similar microhardness with the average values of 88.7 ± 2.1 HV0.5 and 89.9 ± 2.1 HV0.5 for the AFSD and HHSAM depositions. Firstly, the marginal increase in microhardness could be explained by the solid solution strengthening and grain refinement effects. The solid solution strengthening effect of the 5A06 feedstock primarily depends on the solid solution of Mg element, whereas the solid solution strengthening effect of other elements is extremely limited due to their low concentrations. Secondly, the grain structure is clearly refined compared to 5A06 feedstock, which could increase the value of the microhardness28. Additionally, as previously notes, the precipitations designated as Al6(Fe,Mn) and Al3Mg2 phases are identified in the 5A06 feedstock, the AFSD and HHSAM depositions, with significant variations in their respective concentrations (Fig. 4). However, the disparity in the impact on micro-hardness distribution is not reflected, suggesting that these particles do not have a clear strengthening effect on the micro-hardness properties of the specimens, which agrees with the results of Chen et al. and Gao et al.23,29. While the microhardness values of the AFSD and HHSAM deposition is almost the same, it is observed that the microhardness distribution mapping of the HHSAM specimen is more uniform without the formation of regions where the microhardness suddenly decreases, as shown in the AFSD deposition (Fig. 5a). It means that the incorporation of the hybrid heat-source plays a decisive role in the uniformity of the performance of the fabricated component.

Figure 6a shows the engineering stress-stain plots of various specimens after the tensile experiments along LD and BD, and the related tensile properties, including ultimate tensile strength (UTS), the yield strength (YS) and elongation (EL) are listed in Fig. 6b. For the 5A06 feedstock, the values of YS, UTS and EL are 268.9 ± 4.1 MPa, 396.6 ± 3.4 MPa and 21.9 ± 2.2%, respectively. It is reasonable for the fabricated specimens has the lower tensile properties than the 5A06 feedstock, which is due to the dissolution of the particles under the high thermal evolution30. While it is noticed that the HHSAM deposition demonstrates superior tensile performance no matter along LD and BD. Along LD, the values of YS, UTS and EL of HHSAM are slightly increases to 238.3 ± 2.2 MPa, 358.1 ± 2.7 MPa and 27.5 ± 1.9% as compared to that of the AFSD deposition (187.1 ± 4.7 MPa, 355.9 ± 3.4 MPa and 27.2 ± 2.6%). The improvement of the tensile properties along BD of the HHSAM specimen is more significant, values of YS, UTS and EL are increase to 184.0 ± 3.5 MPa, 324.5 ± 2.9 MPa and 15.7 ± 2.2%. However, the AFSD deposition along BD presents the low tensile performance (YS = 179.6 ± 3.7 MPa; UTS = 302.4 ± 3.5 MPa), especially the EL is very low with the value of 4.9 ± 1.4%. Hence, in conjunction with prior research12, it is determined that the use of hybrid heating process increases the heat input, allowing adequate material flow behavior. The improved thermal cycles directly contribute to the enhancement of interface bonding strength and the associated tensile properties (i.e., YS and UTS) of the HSSAM deposition. The notable enhancement in tensile strength along BD further underscores the need of induction heating process, particularly for materials like the 5-series Al-based alloys that cannot undergo heat treatment.

Electrochemical behavior

Figure 7a, b indicates the Eocp and PD plots of the 5A06 feedstock, AFSD and HHSAM depositions, and the corrosion parameters based on the PD curves are summarized in Table 2. It is found that the depositions exhibit the nobler Eocp and Ecorr than that of 5A06 feedstock (−1003.6 mV and −995.2 mV). It might be related to the various distribution of the induced precipitation in the specimens (Fig. 4). As displayed in Table 2, the Icorr ranking of the testing specimens is as follows: 5A06 feedstock (0.6 μA/cm2) > AFSD deposition (0.5 μA/cm2) > HHSAM deposition (0.3 μA/cm2), meaning that the HHSAM deposition exhibits the better corrosion resistance. Meanwhile, it is found that the pitting corrosion behavior is clearly modified, and the Epit is increased to −769.3 mV and −740.4 mV for the AFSD and HSAM depositions as compared to 5A06 feedstock (−779.9 mV). Then, it could be deduced that the HHSAM is easier to reach the passive region, forming the passive film to inhibit the pitting corrosion. The HHSAM also shows the lowest Ipass (1.1 μA/cm2) than the AFSD deposition (1.3 μA/cm2) and 5A06 feedstock (1.4 μA/cm2), further indicating that the induced passive film on the HHSAM deposition is more protective to curb the attack of the NaCl solution.

In order to examine the properties of the induced passive film, the Nyquist and Bode plots of the 5A06 feedstock, the AFSD and HHSAM depositions are fitted by the model, i.e., Rs(Qb(Rb(QfRf))) as inset in Fig. 7c. Rs is the solution resistance, and it often indicates a little change for different specimens31. Rb the Qb represent the resistance and capacitance of the double-layer, and the Rf the Qf are the resistance and capacitance of the induced passive film, respectively32. The fitted parameters are organized in Table 3, showing that the chi-square (\({\rm X}\)2) is in the 10-3 level and means that the fitted results are reliable. Firstly, it is found that the HHSAM exhibits the lowest values of Qb (0.1*10-5 F·cm2) and Qf (1.2*10-5 F·cm2) than the AFSD deposition (0.4*10-5 F·cm2and 4.2*10-5 F·cm2) and 5A06 feedstock (0.5*10-5 F·cm2and 6.2*10-5 F·cm2), as well as the highest values of Rb (0.3*105 Ω⋅cm2) and Rf (3.0*105 Ω⋅cm2) as compared to that of the AFSD deposition (0.3*105 Ω⋅cm2 and 2.3*105 Ω⋅cm2) and 5A06 feedstock (0.2*105 Ω⋅cm2 and 1.7*105 Ω⋅cm2), respectively. As confirmed by the previous findings of Orlikowski et al.33, the values of the above-mentioned parameters are tightly related to the thickness and the uniform degree of the induced passive film. Therefore, it indicates that the formed passive film on the HHSAM deposition is more stable and thicker, with a higher Rf and a lower Qf. The nf of HHSAM is close to 1 (0.997) as compared to that of 5A06 feedstock (0.832) and the AFSD specimen (0.920), which further suggests that the more integrated the film is formed on the surface of the HHSAM deposition.

The scanning results of SECM, as shown in Fig. 8, can help to verify the characteristics of passivation films formed on these three specimens. It is found that the 5A06 feedstock has the highest scanned current with the average value of 7.89 nA (Fig. 8a), indicating that the corresponding surface is active for the regeneration of Fe(CN)64− from the Fe(CN)63− at the Pt probe, and leads to the availability of Fe(CN)64− at the probe. The current of the tested area is in the range of 7.79 ~ 7.96 nA, and it shows that the regeneration reaction activity is clearly enhanced on the 5A06 feedstock due to the faster dissolution of the formed passive film. As exhibited in Fig. 8b, the average current of the AFSD deposition is about 6.35 nA, meaning that the surface activity is decreased. The drop in electrochemical activity shows the regeneration of the electro-active species is hindered, which is due to the protective character of the oxide layer produced on the surface during the immersion experiment34. While it is noticed that the current range of the HHSAM deposition is from 5.75 nA to 6.71 nA with the average current of 6.16 nA (Fig. 8c), meaning the induced passive film on the HHSAM specimen is the densest, and it can better act as a barrier against the attack of corrosive NaCl solutions.

Discussion

Based on the above results and analysis, the corrosion mechanism of the 5A06 feedstock, the AFSD and the HHSAM depositions are explained as following. According to reaction (1), the protective performance of the passivation film formed by the 5A06 feedstock during the first stage of corrosion is poor. Under the continuously attack of the Cl− ions, the passive film is damaged and could be dissolved based on reaction (2), leading to the further dissolution of the 5A06 matrix. So, the 5A06 feedstock possesses lowest corrosion resistance (Fig. 7)35.

For the AFSD deposition, the formation of the precipitation, i.e., Al3Mg2 and Al6(Fe,Mn) phases, plays an important role in affecting its electrochemical behaviors (Fig. 4). The increase in the proportion of particles increases the active degree of metal ions, promotes the formation of passivate film. And the types of passivation film also become diversified, forming oxides containing Mg, Fe and Mn simultaneously, i.e., Mg(OH)2, Fe(OH)2 and Mn(OH)2, as given from reaction (3-5)36. Though the high-resolution XPS spectra results of the 5A06 feedstock, AFSD and HHSAM depositions (Fig. 9), the formation of the passive film after the SECM experiments could be confirmed. Figure 9a displays the full spectrum of the specimens, allowing the main elements present on the specimen covered by the passive film to be identified, i.e., Al, Mg Fe and O. The high-resolution Al 2p, Mg 1 s, Fe 2p core level spectra are exhibited in Fig. 9I-III. From the fitted XPS spectrum of the corroded 5A06 specimen (Fig. 9b), the Al 2p peak, i.e., Al(OH)3 (75.4 eV), Al2O3 (74.5 eV) and metallic Al peaks (74.0 eV), the Mg(OH)2 (1305.5 eV) and MgO peak (1304.3 eV) and the Fe2O3 (723.1 eV) and metallic Fe peak (709.7 eV) are detected, meaning that the formed passive film consists of Al(OH)3, Al2O3, Mg(OH)2, MgO and Fe2O336.

While, for the AFSD specimen, the intensity of the Al2O3 and MgO peaks is markedly improved and the FeO peak (724.9 eV) is also observed in the associated passive film (Fig. 9c). Duan and the co-workers reported the detection of MgO and FeO peaks in the corroded 5A06 alloy using the XPS method37. The fitted spectrum suggests that the newly produced passive film on the AFSD specimen is more stable and could not directly damaged, which helps to curb the corrosion behavior, as proven by the higher Rf than that of the 5A06 feedstock (Table 3). However, the presence of Al3Mg2 phases in AFSD deposition adversely affects the corrosion process. The corrosion potential of the Al3Mg2 phase (−1.29 V) was lower than the Al matrix (-0.73 V), indicating that the Al3Mg2 could be dissolved as an anode under the micro-galvanic corrosion process. The enhancement of corrosion resistance resulting from the creation of a passivation film is diminished.

For the HHSAM deposition, the absence of Al3Mg2 particles effectively avoids the influence of the micro-galvanic corrosion effect on the corrosion process (Fig. 4). The induced diversified and dense passivation film could be confirmed by the corresponding XPS results. The intensity of the Al2O3, MgO, FeO and Fe2O3 peaks are the strongest for the HHSAM depositions (Fig. 9d). The developed passive film could fully protect the matrix from Cl− ion erosion, leading to optimal corrosion resistance, as seen by the lowest Icorr, the highest Rf and the lowest Qf values (Table 2 and Table 3). Moreover, aside from the influence of the formed passive film, the increased volume fraction of the Al6(Fe,Mn) particles among the HHSAM deposition significantly enhances the associated corrosion resistance. It has been reported that Al6(Fe,Mn) particle itself is a stable phase, which effectively resist corrosion processes when dispersed within the microstructure38. Therefore, based on the above analysis, it is concluded that the synergistic effect of the denser passive film and the higher proportion of the Al6(Fe,Mn) phase result in the excellent corrosion resistance of the HHSAM deposition.

Methods

Fabrication process

Detailed composition of the applied feedstock and the substrate, Al 5A06 alloy, were list in Table 4. The AFSD and HHSAM depositions were both fabricated by a modified FSW machine (Aerospace Engineering Equipment (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. China), and the additional heat was provided by the heat supply device (PPC100, Shuangping, China) as in-depth indicated by the previous work39. For AFSD and HHSAM depositions, the processing parameters were the same as follows: 270 rpm rotation speed (Ω), the traverse speed (V) at 60 mm/min and the layer thickness (t) is 1.5 mm. HHSAM was conducted based on the induction heating (Fig. 10a), and the temperature-constant mode was chosen with the set values of 220 °C. Meanwhile, the corresponding power, current and frequency were 1.81 kW, 19.7 A and 28.7 kHz respectively. For the subsequent analysis, the self-developed in-situ process monitoring kit with a 40 mm diameter hollow tool (with two drop-shape protrusions) was applied to monitoring the real time temperature (T), upsetting force (Fups), spindle force (Fspi), spindle torque (Mspi) and bending (Fbend) with a highly frequency (1024 Hz) and an accuracy of 0.5%39,40,41. Figure 10b provides an overview of the parameter monitoring methodology employed during the fabrication process. The monitored Fups function as the force of the spindle, while the measured values of Fspi and Mspi correspond to the force and torque of the deposited specimen14. As the kit moves along TD, friction between the rotating-translating kit and the deposited layer induced additional heat. The softened material was extruded from the advancing side of the kit to the retreating side, where it merged with the material displaced from the retreating side. The Fbend quantifies the force applied by the extruded material on the tool during processing, hence elucidating the material flow behavior. As state in the prior study, the position of the thermocouple was 15 mm above the bottom of the hollow tool, while the induction coil was inserted 3 mm below the thermocouple’s location. Meanwhile, it is necessary to apply a proper amount of lubricating grease to the surface of the feedstock. As shown in Fig. 10c, the AFSD and HHSAM depositions with the desired height of about 50 mm were fabricated. It shows that the HHSAM has less flash as well as material redundancy at the edge of the component, and the forming quality is better compared to the AFSD deposition. The surface is more refined and devoid of minor flaws and imperfections, indicating an enhancement in the fluidity of plastic flow throughout the HHSAM process. The analysis of the performance of the specimens acquired was displayed in the subsequent sections of this work.

Microstructure observation and mechanical property tests

Figure 10d exhibits the sampling locations for the microstructure observation, microhardness test, tensile test, and the electrochemical test, and all the tested specimens were acquired by wire-electrical discharge machining (EDM). For observing the microstructure of the 5A06 feedstock, the AFSD and HHSAM depositions, the cut specimens were ground, polished with polycrystalline diamond suspension and colloidal silica suspension (0.5 μm). After that, the optical microscope (OM, GX71, Olympus, Japan) was applied to examine the corresponding microstructure. Then, the grain structure, texture evolution and the chemical composition were observed by electron back scattered diffraction (EBSD, Symmetry S2, Oxford, UK) equipped with an electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, GeminiSEM 500, Zeiss, Germany). The EBSD data was post-processed through software ‘Aztec-Crystal 2.1’ basing on the ASTM Standard 2627-13 before analyses42.

Microhardness experiments were conducted with a Vickers micro-hardness tester (Qpix Control2, Qness, Austria) which tested the cross-section of the 5A06 feedstock and the depositions (Fig. 10d) at a load of 100 g, a dwell time of 15 s and a step size of 0.5 mm. The tensile properties were evaluated by analyzing specimens oriented in the longitudinal direction (LD) and building direction (BD) of the 5A06 feedstock, as well as the AFSD and HHSAM depositions. Testing was conducted using a universal tensile machine (WDW-20, Shanghai Bairoe Test Instrument Co., Ltd., China) at a strain rate of 2 mm/min under quasi-static conditions43. Detailed dimensions of the testing samples are displayed in Fig. 10d.

Electrochemical measurement

The general corrosion test of the samples, including the 5A06 feedstock, AFSD and HHSAM depositions were carried out with a potentiostat (Versastat-3F, Princeton, USA) surrounding the environment of 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. The saturated calomel electrode (SCE, +0.244 V vs. SHE at 25 ◦C) and a pair of graphite rods were applied as reference electrode (RE) and counter electrode (CE) respectively. After the open-circuit potential (OCP) measurement for 1 h, the potential was stable, and then the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were performed at open circuit potential (Eocp) with a voltage perturbation amplitude of 10 mV at a frequency range from 10 mHz to 100 kHz. Lastly, the potentiodynamic polarization (PD) tests were conducted began at 0.25 VSCE below Eocp with the scanning rate of 1 mV/s. To ensure the creditability of the results, at least three replicas of each specimen were repeated. When analyzing the general corrosion results, the Nyquist and Bode plots were fitted by impedance spectrum data using the software ‘ZsimpWin’. Additionally, the corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (Icorr) were extracted from the PD plots by Tafel extrapolation through software ‘PowerCorr V.2.42’.

The scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM, PAR VersaScan, Princeton, USA) measurements of 5A06 feedstock, AFSD and HHSAM depositions were also performed using Pt microelectrode probe (10 μm diameter). The SCE and a graphite rod were set as RE and CE respectively. Expect for the 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, 2 mMol K3FeC6N6 was added as the electrochemical mediator at the tip44. It has been proved that the inert and stable Fe(CN)63−indicated the fast kinetics at the Pt probe, which was widely applied for conducting feedback mode during SECM test45. The distance between the tip and the substrate of the specimen was controlled at about 10 μm after the Z-approach testing towards the surface. The Pt probe was kept at the potential of + 0.51 VSCE to ensure the diffusion-limited oxidation of the mediator, and a 100 × 100 μm2 area of the specimens was scanned with a scanning rate of 1 μm/s.

Compositions of the induced passive films on the surface of 5A06 feedstock, AFSD and HHSAM depositions after the SECM measurements were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Escalab 250XI, USA) with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source of 1468.6 eV. The survey spectra of the specimens were determined in the range of 0–1200 eV with step size of 0.1 eV. The binding energy was calibrated with the C1s peak (284.6 eV), and all the peaks were fitted by the software ‘ORIGIN’.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Phillips, B. J. et al. Microstructure-deformation relationship of additive friction stir-deposition Al-Mg-Si. Mater 7, 100387 (2019).

Griffiths, R. et al. A perspective on solid-state additive manufacturing of aluminum matrix composites using MELD. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 28, 648–656 (2018).

Robinson, T. W. et al. Microstructural and mechanical properties of a solid-state additive manufactured magnesium alloy. J. Manuf. Sci. 144, 061013 (2022).

Rivera, O. G. et al. Microstructures and mechanical behavior of Inconel 625 fabricated by solid-state additive manufacturing. Mate. Sci. Eng. A 694, 1–9 (2017).

Avery, D. Z. et al. Fatigue behavior of solid-state additive manufactured inconel 625. Jom 70, 2475–2484 (2018).

Griffiths, R. J. et al. Solid-state additive manufacturing of aluminum and copper using additive friction stir deposition: Process-microstructure linkages. Materialia 15, 100967 (2021).

Yu, H. Z. et al. Non-beam-based metal additive manufacturing enabled by additive friction stir deposition. Scr. Mater. 153, 122–130 (2018).

Khodabakhshi, F. & Gerlich, A. P. Potentials and strategies of solid-state additive friction-stir manufacturing technology: A critical review. J. Manuf. Process. 36, 77–92 (2018).

Du, J. et al. Effect on microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir welded 5A06 aluminum alloy joints by deep cryogenic treatment. Mater. Res. Express 11, 046514 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Corrosion mechanism of 5083 aluminum alloy in seawater containing phosphate. J. Ocean U. China 20, 372–382 (2021).

Li, S. M., Li, Y. D., Zhang, Y., Liu, J. H. & Yu, M. Effect of intermetallic phases on the anodic oxidation and corrosion of 5A06 aluminum alloy. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 22, 167–174 (2015).

Ambrosio, D., Wagner, V., Dessein, G., Vivas, J. & Cahuc, O. Machine learning tools for flow-related defects detection in friction stir welding. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 15, 1–15 (2023).

Sun, Y. F., Shen, J. M., Morisada, Y. & Fujii, H. Spot friction stir welding of low carbon steel plates preheated by high frequency induction. Mater. Des. 54, 450–457 (2014).

Gotawala, N. & Hang, Z. Y. Material flow path and extreme thermomechanical processing history during additive friction stir deposition. J. Manuf. Process. 101, 114–127 (2023).

Chen, S., Li, X., Jiang, X., Yuan, T. & Hu, Y. The effect of microstructure on the mechanical properties of friction stir welded 5A06 Al Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 735, 382–393 (2018).

Li, H., Lin, J., Dean, T. A., Wen, S. W. & Bannister, A. C. Modelling mechanical property recovery of a linepipe steel in annealing process. Int. J. Plast. 25, 1049–1065 (2009).

Avery, D. Z. et al. Influence of grain refinement and microstructure on fatigue behavior for solid-state additively manufactured Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 51, 2778–2795 (2020).

Sundar, A. S., Kar, A., Mugada, K. K. & Kumar, A. Enhancement of microstructure, microtexture, and mechanical properties of Al6061 friction stir welds using the developed static shoulder welding tool. Mater. Charact. 203, 113148 (2023).

Machado, D. C. et al. Influence of processing temperature on microhardness evolution, microstructure and superplastic behaviour in an AleMg alloy processed by high-pressure torsion. J. Mater. Res. Texhnol. 24, 2867 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Effects of different friction stir welding processes on residual stress and deformation of Ti62A alloy joints. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 26, 6096–6107 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of multilayer AA6061 alloy fabricated by additive friction stir deposition. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 16, 1–16 (2024).

Liu, D., Lai, X., Huang, Z., Yang, L. & Zhou, K. Study on hot deformation behavior and processing maps of cobalt-based superalloy GH5188. Adv. Eng. Mater. 26, 230167 (2024).

Gao, J. et al. Improving the weld formation and mechanical properties of the AA-5A06 friction pull plug welds by axial force control. Acta Metall. Sin. 33, 828–838 (2020).

Gao, W. et al. Precipitation Behavior and Corrosion Properties of Stirred Zone in FSWed AA5083 Al-Mg Alloy after Sensitization. Metals 13, 1618 (2023).

Huang, Y. & Humphreys, F. J. The effect of solutes on grain boundary mobility during recrystallization and grain growth in some single-phase aluminium alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 132, 166–174 (2012).

Chen, R. Y., Chu, H. Y., Lai, C. C. & Wu, C. T. Effects of annealing temperature on the mechanical properties and sensitization of 5083-H116 aluminum alloy. P. I. Mech. Eng. L, 229, 339–346 (2015).

Tian, N. et al. The formation of three phases containing Fe and Mn in 5182 aluminum alloy. Mater. Character 207, 113497 (2024).

Zhou, X., Zhao, Y., Tian, S., Liu, T. & Zhan, X. Investigation on laser-MIG hybrid-welded joint for 5A06 aluminum alloy: effect of the laser heat input on grain size and microhardness. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 36, 437–452 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. Improving the weld formation and mechanical properties of the AA-5A06 friction pull plug welds by axial force control. Acta Metall. Sin.-Engl. 33, 828–838 (2020).

Reilly, A., Shercliff, H., Chen, Y. & Prangnell, P. Modelling and visualisation of material flow in friction stir spot welding. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 225, 473–484 (2015).

Pan, J., Thierry, D. & Leygraf, C. Hydrogen peroxide toward enhanced oxide growth on titanium in PBS solution: blue coloration and clinical relevance. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 30, 393–402 (1996).

de Assis, S. L., Wolynec, S. & Costa, I. Corrosion characterization of titanium alloys by electrochemical techniques. Electrochim. Acta 51, 1815–1819 (2006).

Orlikowski, J., Ryl, J., Jarzynka, M., Krakowiak, S. & Darowicki, K. Instantaneous impedance monitoring of aluminum alloy 7075 corrosion in borate buffer with admixed chloride ions. Corros 71, 828–838 (2015).

da Silva, R. M. P. et al. The local electrochemical behavior of the AA2098-T351 and surface preparation effects investigated by scanning electrochemical microscopy. Surf. Interface Anal. 51, 982–992 (2019).

Jafarzadeh, K., Shahrabi, T. & Hosseini, M. G. EIS study on pitting corrosion of AA5083-H321 aluminum-magnesium alloy in stagnant 3.5% NaCl solution. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 24, 215–219 (2008).

Ji, Y., Hu, Q., Xia, D. H. & Luo, J. L. Corrosion susceptibility of passive films on 1060, 2024, and 5083 aluminum alloys: experimental study and first-principles calculations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170, 041505 (2023).

Duan, T. et al. Long-term localized corrosion behaviors of 5A06 aluminum alloys exposed in the natural deep-sea environment of South China Sea. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 20, 4597–4607 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Thermal stability of refined Al6 (Fe,Mn) phase formed in laser powder bed fusion process. J. Alloy. Compd. 17, 174593 (2024).

Qiao, Q. et al. Hybrid heat-source solid-state additive manufacturing: A novel method to fabricate high performance AA6061 deposition. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 228, 107–124 (2025).

Qiao, Q. et al. A comparative study of machine learning in predicting the mechanical properties of the deposited AA6061 alloys via additive friction stir deposition, MGEA 31, (2024).

Qiao, Q. et al. In-Situ monitoring of additive friction stir deposition of AA6061: Effect of layer thickness on the microstructure and mechanical properties. Addit. Manuf. 84, 104141 (2024).

ASTM. Standard Practice for Determining Average Grain Size Using Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) in Fully Recrystallized Polycrystalline Materials; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1–5 (2014).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Strain-Controlled Fatigue Testing; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1–16 (2017).

Filot´as, D. et al. Double barrel microelectrode assembly to prevent electrical field effects in potentiometric SECM imaging of galvanic corrosion processes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, C270 (2018).

Polcari, D., Dauphin-Ducharme, P. & Mauzeroll, J. Scanning electrochemical microscopy: a comprehensive review of experimental parameters from 1989 to 2015. Chem. Rev. 116, 13234–13278 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the financial support received from the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macau SAR (0110/2023/AMJ), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFE0205300) and the Joint Fund of Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund of Guangdong Province (No. 2021B1515130009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q. Qiao: Methodology, Writing - Original Draft and Writing - Review & Editing; X. Chen and W.I. Lam: Investigation; Y. Lin and H. Wang: Validation; H. Qian and Z. Li, D. Zhang and C.T. Kwok: Formal analysis; D. Guo: Resources, Conceptualization and Writing - Review & Editing; L.M. Tam: Funding acquisition, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiao, Q., Chen, X., Lam, W.I. et al. Hybrid heat-source solid-state additive manufacturing of 5A06 deposition with favorable mechanical and electrochemical performance. npj Mater Degrad 9, 58 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00595-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00595-6