Abstract

This study assessed osteointegration and degradation of 3D-printed porous pure iron (Fe) versus titanium (Ti) interference screws in porcine anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction over 12 months. Twelve pigs were assigned to Fe (experimental) or Ti (control) groups and euthanized at 3-, 6-, or 12-month post-surgery. Osteointegration was evaluated via micro-computed tomography, biomechanical tests measured ACL failure load, and histology examined bone and tissue integration. No significant differences in ACL failure load were noted between groups. Fe implants showed significantly greater bone volume fraction, bone surface density, and intersection-to-total surface area (P = 0.025, 0.047, 0.021). Minimal degradation of Fe implants was observed, with stable implant volumes and histological confirmation of osteoid attachment. Median ambulation time was shorter with Fe implants (5 weeks) than with Ti implants (11 weeks; P = 0.075). Findings demonstrate Fe implants’ biocompatibility and enhanced peri-implant osteogenesis, though improved degradation rates are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries occurred at a rate of approximately 23.3 per 100,000 person-years, with surgical reconstruction via arthroscopy performed in 67% of these cases1. Among surgical techniques, interference screws provided superior initial stability and minimal “windshield wiper effect” during graft fixation, making them the predominant choice2. Traditionally, these screws were crafted from titanium for durability or polymers for biodegradability and improved bone ingrowth3. However, polymer-based alternatives had limitations, including increased inflammatory response, pseudo cyst formation, and bone tunnel enlargement4,5.

Biodegradable implants have a degradation rate of 0.2–0.5 mm per year6,7. In vivo data indicate a significantly slower degradation rate than in vitro conditions, and there is an established correlation between these two environments for different materials8 Common biodegradable metals explored include magnesium (Mg)9, zinc (Zn)10, and iron (Fe)11. The rapid degradation and hydrogen gas production posed challenges for Mg-based implants12. Zinc and its alloys offered a slower degradation rate, between 0.02 and 0.05 mm per year13, and exhibited lower mechanical strength14. The in vitro corrosion rate of pure Fe implants varies from 0.049 to 0.23 mm per year15,16,17,18, while Fe-alloys demonstrate a higher corrosion rate, ranging from 0.13 to 1.1 mm per year18. Fe-based materials demonstrated comparable bony mechanical properties and good cytocompatibility. Recent research has focused on controlling the degradation rate of Fe-based implants by employing porous structural designs and surface modifications to accelerate corrosion19 while maintaining adequate mechanical strength15,20.

Pure Fe biodegradable implants have demonstrated slow in vivo degradation rates, which may limit their clinical applicability. However, alloying and surface modifications have been explored to accelerate degradation while preserving mechanical stability21. Studies using rabbit models have shown that Fe-based biodegradable implants exhibit good osteointegration and minimal inflammatory response, although the prolonged presence of degradation products remains a concern15. Larger animal studies, such as those conducted in sheep, have provided valuable insights into the long-term behavior of Fe-based biodegradable implants, highlighting their potential as viable alternatives for load-bearing orthopedic applications22.

This study compared commercial Ti interference screws with innovative biodegradable 3D-printed Fe interference screws. A porcine model was utilized for ACL reconstruction due to the structural and mechanical properties of the porcine ACL closely resembling those of humans23, with observations conducted for up to 12 months post-surgery. Analyses evaluated the biosafety, biomechanical strength, and biodegradability of the Fe interference screw. The novelty of this is in using a porcine model to evaluate the long-term in vivo degradation and performance of a 3D-printed porous Fe interference screw. These key insights into the clinical feasibility of biodegradable Fe implants by employing a weight-bearing model with human-like biomechanics. The primary outcome was peri-implant bone growth, while the secondary outcomes assessed implant degradation, ACL failure load, safety following iron degradation, and post-surgical recovery of normal ambulation.

Results

Radiograph

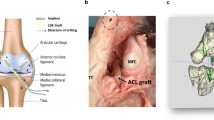

Radiographic examinations at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively confirm that the screws remain in their original positions without evidence of migration or loosening (Fig. 1).

In vivo biomechanical analysis

The ultimate in vivo biomechanical analysis results revealed no significant difference in the ultimate failure load between Fe and Ti interference screws at 3 months: 262 [205, 319] newtons (N) vs. 333 [333, 333] N (P = 0.564). At 6 months, there was also no significant difference: 481 [332, 630] N vs. 142 [142, 142] N (P = 0.248). At 12 months, there was also no significant difference: 406 [293, 950] N vs. 311 [311, 311] N (P = 0.564).

Histology of Bone Growth

Mineralized bone formation was observed in the Fe and Ti groups, with a progressive increase noted from 3 to 12 months (Figs. 2 and 3). Histological analyses consistently revealed mineralized osteocytes in regions near the interference screw. Furthermore, a greater accumulation of degradation products was noted around the Fe interference screw at 12 months than at 3 months.

Histological examination of bone and interference screws stained with Sanderson’s rapid bone stain, located in the porcine femur and tibia at 12 months post-operation, reveals a higher proportion of osteoid around and within the central portion of the Fe interference screws. M months, DP degradation products, O osteoid, Fe iron, Ti titanium, I interference screw.

Histopathology of visceral organ

The histopathological examinations of the liver, spleen, heart, lungs, and kidneys revealed no significant differences between the Fe and Ti interference screws at the 3-month and 12-month intervals (Fig. 4). Prussian blue staining specifically targets ferric iron; Fig. 5 shows no significant difference in iron deposits between the Ti and Fe groups in the liver and spleen over time.

Histological examination of porcine liver and spleen tissues stained with Prussian blue iron, following the implantation of titanium and iron interference screws for periods of 3 months and 12 months. The column bar plot illustrates the semi-quantitative analyses of the stained areas of the liver and spleen in both groups—error bars, median, and interquartile range. M months, Fe iron, Ti titanium.

Micro-computer tomography

Micro-CT analytical results for external and internal BV/TV, BS/TV, is/TS are presented in Fig. 6. Generally, these variables are comparable between the Ti and Fe groups. The BV/TV values were higher in the Fe and Ti groups over time (P = 0.025). The BS/TV values were higher in the Fe and Ti groups over time (P = 0.047). The is/TS values were higher in the Fe and Ti groups over time (P = 0.021) Table 1.

Micro-computed tomography analysis was conducted on the peri-implant bone around titanium (Ti) and iron (Fe) interference screws at 3-, 6-, and 12-month post-implantation. Spectral analysis was used to visualize bone density, with red and black indicating lower bone mass and blue and white indicating higher bone mass. Results are presented as column bar plots depicting bone volume fraction (BV/TV), bone density, and Intersection Surface/Tissue Surface ratio—error bars, median, and interquartile range. M month. * indicated P < 0.05.

The analytical results of micro-CT to detect the Fe interference screw degradation over time are presented in Table 2. The micro-CT did not find statistical differences in the implant volume, surface, or thickness over time.

Micro-CT analytical results measured bony tunnel morphometric indices for Fe and Ti groups (Fig. 7). The total CSA values were no different in the Fe and Ti interference screws at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months (P = 0.11).

The cross-sectional micro-computed tomography images illustrate no significant obvious difference in the osseous tunnel formation (white arrows) around the implant over time. The column bar plot depicts the cross-sectional area of tunnels in both groups at three time points—error bars, median, and interquartile range. Ti titanium, Fe iron, M months, CSA cross-sectional area.

Return to ordinary ambulation

Compared with the control group undergoing ACL reconstruction with Ti interference screws, the median time to return to ordinary ambulation was shorter in the biodegradable Fe group (5 [3, 13] weeks) than in the Ti group (11 [6, 13] weeks), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.075) (Supplementary Video).

Complete blood test and serum biochemical analysis

Most of the complete blood count and serum chemistry levels showed no significant changes across all time points, as shown in Fig. 8. The only difference is detected in the glucose level between immediately (120.5 [71, 171] mg/dL) and one month (93.0 [64, 125] mg/dL) postoperatively (P = 0.0071).

The column bar plot illustrates the complete blood count and serum blood chemistry changes over time—error bars, median, and interquartile range. RBC, red blood cell; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, CK-MB creatine kinase-MB, TIBC total iron binding capacity, CPK creatine phosphokinase. ** indicated P < 0.01.

Discussion

In this one-year observational study, we investigated biodegradable porous Fe interference screws compared to Ti interference screws in ACL reconstruction using a porcine model. Our findings suggest potential benefits of Fe interference screws, notably a trend towards faster recovery of normal ambulation and significantly improved peri-implant bone growth without compromising biomechanical stability or systemic safety. However, the anticipated degradation of the Fe interference screws was minimal over 12 months, indicating a slower-than-expected corrosion rate.

The observed superior peri-implant bone formation associated with Fe interference screws, demonstrated by increased bone volume fraction, bone surface density, and intersection-to-total surface area, could be attributed to several mechanisms. First, the porous architecture of Fe implants likely facilitated enhanced osteogenic cell infiltration and vascularization, fostering an environment conducive to accelerated bone remodeling and integration11,24. Previous studies have similarly reported that specific pore sizes, ranging from 210 to 390 μm, and designs significantly influence osteointegration and subsequent bone formation25. Second, Fe degradation products, such as iron oxide and hydroxides, may play an active role in osteogenesis by providing a bioactive interface promoting cellular adherence and proliferation26.

Despite these promising results, the minimal degradation rate of the Fe implants in vivo remains a critical challenge. Several factors might explain the slow degradation observed. Biological environments, characterized by lower oxygen concentrations and limited fluid circulation compared to in vitro conditions, significantly reduce the corrosion rate of Fe-based implants27. Additionally, the accumulation of degradation products and mineralized tissues on the implant surface may have created a protective barrier, further inhibiting corrosion28. Previous literature has also reported slower in vivo corrosion rates of pure Fe compared to its alloys, highlighting the potential necessity of alloying or surface modifications to achieve clinically meaningful degradation rates29,30,31.

Furthermore, this study did not observe late complications such as inflammatory responses or tunnel widening, shared concerns for biodegradable implants5. The histological findings indicate favorable osteointegration, further stabilizing the implant within the bone. As a result, despite a certain degree of degradation, the in vivo biomechanical analysis demonstrated that the Fe interference screw exhibited no significant difference in mechanical stability compared to commercialized implants. Future research should focus on continuously fine-tuning the degradation rate to an optimal level while ensuring that chronic inflammatory reactions, potential systemic effects of iron degradation, and the safety of degradation products do not compromise long-term biocompatibility. Under these conditions, Fe interference screws could evolve into a viable alternative for human ACL reconstruction.

Pure Fe biodegradable implants have demonstrated excellent biocompatibility in various studies15,20,32,33. This favorable biocompatibility can be evaluated from several aspects, including cytocompatibility, compatibility with local and distant organs, and hemocompatibility. Histological analysis at 12 months revealed no significant aggregation of inflammatory cells and a substantial attachment of osteoid to the implant. In the previous report, some iron deposition was observed at 3 months of pure implant suture anchor in the spleen of a rabbit model20. The existing literature rarely addresses the impact of pure Fe implants on systemic inflammation beyond 12 months. Importantly, the absence of local inflammation, tunnel widening, or systemic toxicity emphasizes the high biocompatibility of Fe implants observed in this study. Although earlier studies have raised concerns regarding iron overload and inflammatory reactions with Fe-based implants, our histological and biochemical analyses revealed no significant systemic or local adverse effects over the 12-month period. These findings align with previous research demonstrating the safety and biocompatibility of pure iron implants.

Our biomechanical evaluations found comparable ACL graft fixation strength between Fe and Ti interference screws, despite structural and surface differences. This biomechanical stability underscores that the porous Fe interference screw provided sufficient mechanical support throughout the healing process, potentially enhancing clinical outcomes by maintaining implant stability until complete tissue integration is achieved.

The study has several limitations: First, while the porcine model resembles the human body, pigs are quadrupeds with different knee biomechanics than humans. This study focused on the static biomechanics of the reconstructed ACL graft, testing the maximum failure load only under translational load, which may not fully reflect real-life conditions34. Second, the surface roughness and porous structure of Fe interference screws differed from Ti implants, contributing to improved bone ingrowth. Additionally, the structural differences between Ti and Fe implants may enhance osteointegration and increase maximum pullout strength, as ACL ultimate failure load measurements indicate. Third, pigs in the Fe group had a marginally shorter recovery time to normal ambulation than those in the Ti group. Still, this study did not include a sham procedure group, preventing an accurate assessment of the ACL reconstruction’s impact on walking ability. Fourth, a 12-month follow-up observed iron degradation without significant complications in large animals, but longer observation periods are needed to ensure long-term biocompatibility. Lastly, the study was limited by a relatively small sample size, which may impact the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. These limitations highlight areas for future research and improvement.

This porcine model study demonstrated the biocompatibility of biodegradable porous pure iron implants, showing no local inflammation or systemic toxicity. The Fe interference screws exhibited better peri-implant bone growth and bone quality than the Ti implants over 12 months. However, no significant volume changes in Fe implants were found. Future biodegradable Fe medical devices could increase degradation rates through enhanced porosity, alloying, and other advanced processing techniques.

Methods

Implant design

The biodegradable Fe implant scaffold (Model S0001, dimensions: 7 × 19.5 mm) was fabricated using the Laser Powder Bed Fusion technique on an AM100 3D metal printer (ITRI, Taiwan). High-purity Fe powder (≥99.5%) was processed through selective laser melting as the raw material. It includes both solid and non-solid parts. The pore size of metallic porous implants, ranging from 100 µm to 700 µm, and scaffold porosity exceeding 40% are considered effective for promoting bone ingrowth and vascularization35. The solid part has an internal support structure and an external threaded design. The non-solid part has quadrangular pores ranging from 210 to 390 μm. The porosity of the non-solid part, defined as the ratio of pore volume to screw wall volume, is 44%. Specifications of the Fe interference screw and the control group, the commercial titanium (Ti) interference screw (Guardsman®, 7 × 20 mm, CONMED, USA), are shown in Fig. 9.

Specifications of (A) pure iron interference screw and (B) titanium interference screw. The porous outer layer, composed of quadrangular poles ranging from 210 to 390 μm, is designed to promote osteointegration. Microscopic examination revealed the rough surface of the iron interference screw, and a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) view of the implant was provided. The scale bar in the SEM image represents 50 µm.

In vivo animal study design

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Biomedical Technology and Device Research Laboratories (ITRI-IACUC-2021-051FV1) in line with national welfare legislation and NIH guidelines. Twelve Lanyu miniature pigs (Pigmodel Animal Technology Co., Ltd) with a median weight of 69.9 kg (range 63–80 kg) at 4.6 years (range 4.0–4.9 years) were selected. Each minipig hindfoot joint was randomly assigned to the experimental or control group. In the control group, titanium screws were implanted in 3 hind feet; in the experimental group, iron screws were implanted in 9 hind feet using the same procedure. At each study endpoint, pigs were sedated via intramuscular injection of Telazol (tiletamine-zolazepam, 4.4 mg/kg) and euthanized by intravenous administration of a saturated potassium chloride solution (2 mEq/kg) through the auricular vein. Death was confirmed by the absence of cardiac and respiratory activity and the loss of corneal reflex, following the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020). Euthanasia was performed at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively, involving one pig from the control group and three pigs from the experimental group at each time point. Radiographic imaging verified screw positioning before further examination. All specimens were included except those excluded due to hindfoot injuries or death before sacrifice (Supplementary Figure 1).

Surgical methods

Experimental animals were fasted for at least 12 h before surgery, but water was allowed. After cleansing and drying, the pigs received an intramuscular (IM) injection of azaperone (0.3–0.5 mg/kg) and atropine (0.03–0.05 mg/kg). The respiratory rate was monitored. After 20–30 min, anesthesia was induced using an IM tiletamine-zolazepam mixture (Zoletil® 50) at 3–5 mg/kg. After 5–10 min, the pigs were moved to the surgical table, positioned in sternal recumbency, and intubated. Anesthesia was maintained with a mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide (2:1) at 2–3 L/min with 0.5–2% isoflurane. The depth of anesthesia was monitored. Preoperative IM injections included cefazolin (15 mg/kg) and meloxicam (0.4 mg/kg).

A bone-patellar tendon autograft was harvested, with a median length of 95 mm (range 80–100 mm) and a median width of 5.5 mm (range 5–8 mm). The bony portion had a median length of 15.0 mm (range 10–20 mm). The tibial tunnel was prepared using a 7 mm reamer. An inside-out technique was used for the femoral tunnel, which was 8 mm wide and 20 mm deep. The bony autograft was fixed in the femoral tunnel and secured with an interference screw. The tendon portion was pulled through the tibial tunnel and secured with another interference screw at the outer orifice.

Postoperative analgesia included an initial IM injection of meloxicam (0.1–0.4 mg/kg) preoperatively and immediately postoperatively, followed by IM ketoprofen (1–3 mg/kg) once daily and oral meloxicam (0.1–0.4 mg/kg) daily for seven days. Prophylactic antibiotics included preoperative and immediate postoperative IM cefazolin (15 mg/kg), supplemented with IM penicillin (10,000 units/kg) and oral cephalexin (30 mg/kg twice daily) and amoxicillin (20 mg/kg twice daily) for seven to fourteen days, depending on the minipig’s appetite and activity level.

Functional outcome

Animal care personnel conducted daily close observations of the minipigs and meticulously documented the standing posture of each animal. The caregivers identified ‘return to regular walking’ as the primary functional outcome independent of the type of interference screw used in the surgical procedures. This outcome was defined as the ability to walk normally, which in the minipig is characterized by walking over five or more steps with alternating hind limbs and coordinated fore-hind limb movement, demonstrating good knee flexion and without a biased center of gravity favoring the limb, not subjected to surgery36.

Biomechanical analysis

Based on the protocol described by Paschos et al.37, the biomechanical tests were conducted using an Instron 5900 R Tensile Compression Test Machine (Instron, USA) equipped with a 5-kN load cell. The specimen was secured within a custom clamping device. One side of the specimen (the femur) was attached to the load cell, while the other (the tibia) was connected to the actuator of the materials testing machine. The exam was performed at 25 °C.

To ensure the integrity of the biological specimens, the displacement rate was directly controlled during the tensile tests, with a consistent 10 mm/min rate applied until failure. The experiment aimed to evaluate the ultimate failure strength, so the influence of initial biological conditions, such as viscoelastic or pre-conditioning effects, was intentionally excluded to maintain uniform testing conditions. This approach focused on obtaining reproducible results for the maximum failure load under consistent mechanical testing parameters.

No pre-tensioning was applied, as the secure fixation in the clamps ensured proper alignment with the loading axis. This configuration led to a measurable delay in load transfer, as evidenced by the load-elongation curves. The maximum failure load (N) was determined by Bluehill® 4.03 (Instron, USA).

Micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) analytic protocol

After the euthanasia of the minipigs, femoral and tibial specimens (12 from each group) were harvested and scanned using a multi-scale nano-CT system (Skyscan 2211, Bruker Micro-CT, Belgium) at a resolution of 30 μm per pixel across a 360-degree rotation. Imaging parameters included a voltage of 150 kVp and a current of 80 μA, producing 5.7 watts with a 0.25 mm Cu filter. Image reconstruction was performed using Instarecon and NRecon software to correct ring artifacts and beam hardening15. Reconstructed images were reoriented, and regions of interest (ROIs) were identified and analyzed in 5 mm sections comprising 168 slices. Bone growth assessments were done using Bruker CTAn Assay software after segmenting the 7 mm diameter ROI around the implant. The 0–1000 μm perimeter surrounding the implant was defined for bone growth analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Tissue volume (TV), bone volume (BV), and bone surface area (BS) within this region were quantified in mm3 and mm2. New bone formation was either external (adhering to the implant) or internal (proliferating into the interference screw central hollow). BV fraction (BV/TV) was expressed as a percentage, and BS density (BS/TV) as 1/mm. The intersection to the total surface (is/TS) ratio (%) was also calculated. Implant volume, surface area, and structural thickness were measured in mm3, mm2, and mm to assess degradation over time. Tunnel morphometric indices, mean total cross-sectional area (CSA), were quantified in mm2.

Histological analysis of bone ingrowth

Twelve specimens from each group were collected for macroscopic and histological examination. Each sample was fixed in 10% formalin for 14 days, then dehydrated using ethanol concentrations of 70%, 95%, and 100% for at least one day. The specimens were infiltrated with polymethylmethacrylate over 5 days15. The samples were embedded and cut vertically for histological sectioning at the bone-implant interface. Sections were sliced to approximately 150 μm with a low-speed saw (IsoMet, Buehler, USA) and ground to 60 μm using a grinding and polishing machine15. These sections were stained with Sanderson’s rapid bone stain (Dorn & Hart Microedge Inc., USA) and counterstained with acid fuchsin. The bone-implant interfaces were examined under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-series, USA).

Histological analysis of visceral organs

Additionally, twelve sets of visceral organs from each group, specifically the liver, kidney, heart, and spleen, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The remaining sets were stained with Prussian blue to visualize iron metabolism in visceral organs, specifically the spleen and liver28. The Prussian blue-stained samples were analyzed semi-quantitatively using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The percentage area (%) was calculated by dividing the stained area on the slide by the total specimen area on the same slide.

Complete blood count and serum biochemical analysis

Blood samples were collected preoperatively from all minipigs and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively for analysis. Serum processing was performed in a medical laboratory accredited by ISO 15189:201238, utilizing the ADVIA Chemistry XPT System (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) automated spectrophotometer. The analyses included complete blood count parameters (red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit), blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, creatine phosphokinase, total iron binding capacity, creatine kinase MB, iron, and iron saturation.

Statistics

All experimental data are presented as median and range [min, max]. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare two independent groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare three or more independent groups. Both non-parametric tests analyze ordinal data or data not meeting parametric test assumptions. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. A two-sample, two-sided t-test calculated post hoc power to determine if it exceeded 80% by comparing BV/TV values between Fe and Ti interference screws at 12 months. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1 and R 4.3.3, with part of the data visualized using PRISM GraphPad 10.2.3.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in this article's main text.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Weitz, F. K., Sillanpaa, P. J. & Mattila, V. M. The incidence of paediatric ACL injury is increasing in Finland. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol., Arthrosc.: Off. J. ESSKA 28, 363–368 (2020).

Zhu, J. et al. ACL graft with extra-cortical fixation rotates around the femoral tunnel aperture during knee flexion. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. Off. J. ESSKA 30, 116–123 (2022).

Papalia, R. et al. Metallic or bioabsorbable interference screw for graft fixation in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction? Br. Med. Bull. 109, 19–29 (2014).

Martinek, V. & Friederich, N. F. Tibial and pretibial cyst formation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy 15, 317–320 (1999).

Barber, F. A. Complications of biodegradable materials: anchors and interference screws. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 23, 149–155 (2015).

Niinomi, M., Nakai, M. & Hieda, J. Development of new metallic alloys for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 8, 3888–3903 (2012).

Oriňák, A. et al. Sintered metallic foams for biodegradable bone replacement materials. J. Porous Mater. 21, 131–140 (2014).

Sanchez, A. H. M., Luthringer, B. J. C., Feyerabend, F. & Willumeit, R. Mg and Mg alloys: How comparable are in vitro and in vivo corrosion rates? A review. Acta Biomater. 13, 16–31 (2015).

Xue, J. et al. A biodegradable 3D woven magnesium-based scaffold for orthopedic implants. Biofabrication 14, https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5090/ac73b8 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Additively manufactured biodegradable porous zinc. Acta Biomater. 101, 609–623 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Additively manufactured biodegradable porous iron. Acta Biomater. 77, 380–393 (2018).

Wang, J. L., Xu, J. K., Hopkins, C., Chow, D. H. & Qin, L. Biodegradable magnesium-based implants in orthopedics-a general review and perspectives. Adv. Sci. 7, 1902443 (2020).

Mostaed, E., Sikora-Jasinska, M., Drelich, J. W. & Vedani, M. Zinc-based alloys for degradable vascular stent applications. Acta Biomater. 71, 1–23 (2018).

Bowen, P. K. et al. Evaluation of wrought Zn-Al alloys (1, 3, and 5 wt % Al) through mechanical and in vivo testing for stent applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl Biomater. 106, 245–258 (2018).

Liu, W. C. et al. 3D-printed double-helical biodegradable iron suture anchor: a rabbit rotator cuff tear model. Materials 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15082801 (2022).

Schinhammer, M., Steiger, P., Moszner, F., Loffler, J. F. & Uggowitzer, P. J. Degradation performance of biodegradable Fe-Mn-C(-Pd) alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 33, 1882–1893 (2013).

Zhu, S. et al. Biocompatibility of pure iron: in vitro assessment of degradation kinetics and cytotoxicity on endothelial cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 29, 1589–1592 (2009).

Hermawan, H., Dube, D. & Mantovani, D. Degradable metallic biomaterials: design and development of Fe-Mn alloys for stents. J. Biomed. Mater. Res A 93, 1–11 (2010).

Sharma, P. & Pandey, P. M. Corrosion rate modelling of biodegradable porous iron scaffold considering the effect of porosity and pore morphology. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl 103, 109776 (2019).

Tai, C. C. et al. Biocompatibility and biological performance evaluation of additive-manufactured bioabsorbable iron-based porous suture anchor in a rabbit model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147368 (2021).

Khan, A. R. et al. Recent advances in biodegradable metals for implant applications: exploring in vivo and in vitro responses. Results Eng. 20, 101526 (2023).

Wegener, B. et al. Development of a novel biodegradable porous iron-based implant for bone replacement. Sci. Rep. 10, 10 (2020).

Bascunan, A. L., Biedrzycki, A., Banks, S. A., Lewis, D. D. & Kim, S. E. Large animal models for anterior cruciate ligament research. Front Vet. Sci. 6, 292 (2019).

Wegener, B. et al. Development of a novel biodegradable porous iron-based implant for bone replacement. Sci. Rep. 10, 9141 (2020).

Murphy, C. M., Haugh, M. G. & O’brien, F. J. The effect of mean pore size on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 31, 461–466 (2010).

Salama, M., Vaz, M. F., Colaco, R., Santos, C. & Carmezim, M. Biodegradable iron and porous iron: mechanical properties, degradation behaviour, manufacturing routes and biomedical applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb13020072 (2022).

Han, H.-S. et al. Current status and outlook on the clinical translation of biodegradable metals. Mater. Today 23, 57–71 (2019).

Vogt, A. S. et al. On iron metabolism and its regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094591 (2021).

Wermuth, D. P. et al. Mechanical properties, in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility analysis of pure iron porous implant produced by metal injection molding: A new eco-friendly feedstock from natural rubber (Hevea brasiliensis). Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 131, 112532 (2021).

Cheng, J. & Zheng, Y. F. In vitro study on newly designed biodegradable Fe-X composites (X = W, CNT) prepared by spark plasma sintering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl Biomater. 101, 485–497 (2013).

Tong, X. et al. Microstructure, mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and in vitro corrosion and degradation behavior of a new Zn–5Ge alloy for biodegradable implant materials. Acta Biomater. 82, 197–204 (2018).

Lin, W. et al. Long-term in vivo corrosion behavior, biocompatibility and bioresorption mechanism of a bioresorbable nitrided iron scaffold. Acta Biomater. 54, 454–468 (2017).

Tai, C. C. et al. Biocompatibility and biological performance of additive-manufactured bioabsorbable iron-based porous interference screws in a rabbit model: a 1-year observational study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314626 (2022).

Woo, S. L. et al. The effectiveness of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with hamstrings and patellar tendon. A cadaveric study comparing anterior tibial and rotational loads. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 84, 907–914 (2002).

Li, J. P. et al. Bone ingrowth in porous titanium implants produced by 3D fiber deposition. Biomaterials 28, 2810–2820 (2007).

Kuluz, J. et al. Pediatric spinal cord injury in infant piglets: description of a new large animal model and review of the literature. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 33, 43–57 (2010).

Paschos, N. K. et al. Cadaveric study of anterior cruciate ligament failure patterns under uniaxial tension along the ligament. Arthroscopy 26, 957–967 (2010).

Zima, T. Accreditation of medical laboratories—system, process, benefits for labs. J. Med. Biochem. 36, 231–237 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Industrial Technology Research Institute M356EX3100 and Kaohsiung Medical University KMU-QA114001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-C.L., P.-I.T., and C.-Y.C. conceptualized the study. W.-C.L., H.-W.C., S.-I.H., C.-H.M., and K.-Y.Y. curated the data. Formal analysis was conducted by W.-C.L. and S.-I.H. H.-W.C., S.-I.H., C.-H.M., K.-Y.Y., C.-H.C., Y.-H.W., and C.-Y.C. carried out the investigation. Funding acquisition was led by K.-Y.Y., P.-I.T., and C.-Y.C. Resources were provided by P.-I.T. S.-I.H. developed the software. W.-C.L. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. C.-H.C., Y.-H.W., C.-Y.C., and Y.-C.F. reviewed and edited the manuscript. Supervision was provided by Y.-C.F. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, WC., Chang, HW., Huang, SI. et al. Biodegradable porous iron versus titanium interference screws in porcine ACL reconstruction model: a one-year observational study. npj Mater Degrad 9, 77 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00602-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00602-w