Abstract

The prediction of corrosion resistance in High-entropy alloys (HEAs) faces challenges due to previous machine learning methods not fully capturing the interdependencies between composition, processing, and crystal structure. This study proposes the Composition and Processing-Driven Two-Stage Corrosion Prediction Framework with Structural Prediction (CPSP Framework), which first predicts crystal structure and then combines composition and processing data for corrosion current prediction. A deep learning model, Mat-NRKG, is developed based on the CPSP framework, efficiently integrating composition, processing, and crystal structure data through a knowledge graph and graph convolutional network. Evaluations using the HEA-CRD dataset show that the CPSP Framework outperforms the Composition-Only Prediction Framework (CP Framework) and the Composition and Processing-Based Prediction Framework (CPP Framework). The Mat-NRKG model demonstrates the best performance on the HEA-CRD dataset. Its generalization capability is validated through experiments on five laboratory-synthesized HEAs, highlighting the effectiveness of incorporating prior knowledge into model design for performance prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs)1,2 represent an emerging class of metallic materials, characterized by their disordered chemical environments and high mixed entropy. These characteristics contribute to their exceptional mechanical properties3,4, oxidation resistance5,6, and corrosion resistance7,8,9,10,11. Corrosion resistance, plays a crucial role in the performance and lifespan of HEAs in harsh environments12. While chemical composition is a key factor, corrosion resistance is, in many cases, also influenced by microstructure and processing techniques13,14,15. In particular, the crystal structure influences elemental distribution and phase stability, which in turn affects localized corrosion behavior16.

Due to the vast compositional space17,18, developing HEAs using traditional experimental approaches often face high costs and time constraints19,20. Although computational simulations21,22,23 can provide theoretical guidance for materials design, they typically require extensive computational resources24 and are limited to small scales, making it difficult to fully capture the effects of composition, structure, processing conditions, and complex environmental effects on the corrosion resistance of HEAs25.

Machine learning (ML) techniques have capability of uncovering underlying patterns from experimental data and predicting material properties26,27,28, offering an effective approach to HEA design and optimization29,30,31,32. Although some ML-based studies have been conducted on HEA performance prediction, limitations remain in current methods. Some studies13,33,34 focus solely on the chemical composition’s effect on corrosion resistance, neglecting the influence of non-compositional factors such as processing techniques and crystal structure. The study35 has integrated composition, processing, and structure into machine learning models. This integration of prior knowledge enhances the interpretability of the predictive models36,37. However, using structural information as an explicit input often limits the model’s engineering applicability, since obtaining such data typically requires experimental preparation and characterization38,39, theoretical modeling40,41,42, or simulation43,44. Therefore, building models that can simultaneously capture the complex relationships among composition, processing, and structure, while maintaining high interpretability, predictive performance, and practical usability, remains a significant challenge.

To address this challenge, an innovative the Composition and Processing-Driven Two-Stage Corrosion Prediction Framework with Structural Prediction (CPSP Framework) is proposed for the first time, which hierarchically models the composition – processing – structure – performance relationships. By first predicting the crystal structure and then integrating it with composition and processing data, CPSP eliminates the need for experimentally obtained structural input during the inference stage, thereby improving its engineering applicability. Furthermore, the framework is compatible with various ML models capable of both classification and regression, ensuring broad adaptability. Building upon the CPSP framework, a specialized deep learning model, Mat-NRKG, is proposed, leveraging knowledge graph techniques45 for enhanced predictive capabilities. The knowledge graph organizes and models unstructured process-related data from the literature in a flexible graph structure46, which facilitates the capture of capturing complex relationships among composition, processing, and structure-performance correlations. The Mat-NRKG model leverages the TransE algorithm47 for knowledge graph completion to predict crystal structure, while integrating compositional and processing information through a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)48 augmented with a Deep Taylor Block (DTB)49 module. Ultimately, this end-to-end approach predicts corrosion current. In this study, we focus on improving precision, referring to the consistency of our model’s predictions, rather than accuracy, which is influenced by the quality of the input data. By leveraging a knowledge graph to encode the interactions among composition, processing, and predicted structure, Mat-NRKG enables more transparent reasoning and provides a certain level of interpretability, while also improving prediction precision. Compared to the original NRKG model, which requires crystal structure as an input, Mat-NRKG incorporates a structure prediction step based on composition and processing information, making it more applicable in practical settings where structural data may be unavailable, and thereby potentially increasing its engineering utility. The Composition-Only Prediction Framework (CP Framework) and the Composition and Processing-Based Prediction Framework (CPP Framework) are constructed as baselines to evaluate the CPSP Framework and Mat-NRKG model. The HEA-CRD dataset35 is used to compare the corrosion resistance prediction performance of these models, where CPSP demonstrates consistent improvements over CP and CPP, while Mat-NRKG further enhances performance, reducing MSE by at least 25%. Additionally, five HEAs were synthesized to validate generalization, demonstrating robustness of the CPSP framework and Mat-NRKG method.

Results and discussion

HEA corrosion resistance dataset and statistical analysis

The existing literature provides extensive data on the corrosion resistance of HEAs, but typically reports only the corrosion current for a single alloy or a specific alloy category. The dataset used in this study is the HEA Corrosion Resistance Dataset (HEA-CRD)35, which was curated by combining large language models with manual inspection to select 151 corrosion resistance records extracted from the literature. These data encompass the composition, processing techniques, and crystal structures of HEAs within the Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Cu-Ni-Mn system. Corrosion current densities were measured at 25 °C (or room temperature) in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution using polarization experiments.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of alloy compositions for Al, Co, Cr, Fe, Cu, Ni, and Mn. Alloys containing Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu, or Mn typically have atomic percentages of these elements ranging from 10 to 30%, while the atomic percentage of Al is generally below 20%. Additionally, Al, Cu, and Mn often exhibit distinct bimodal distributions in many HEAs.

This figure shows the distribution of elemental content (in atomic percent, a.t. %) for six elements: Al, Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu, and Mn. The violin plots illustrate the range and distribution of each element across the dataset, with the central box indicating the interquartile range (IQR) and the black line representing the median. The individual data points are shown as dots. The x-axis represents the different elements, while the y-axis corresponds to the atomic percentage of each element.

Figure 2 shows the Spearman correlation analysis50 between elements and material properties. It indicates that Cr and Cu exhibit correlation coefficients (absolute value) with corrosion current (\(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\)) greater than 0.3, suggesting moderate correlation with \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\)51. In contrast, other elements show weak correlations with \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\). It should be noted that compositional data derived from literature sources generally do not include detailed quantification of trace impurities. Thus, nominally reported zero concentrations may not reflect absolute absence, potentially introducing uncertainty into correlation analyses and model interpretations. The weak correlations, coupled with uncertainties arising from data quality, can complicate model convergence and reduce predictive precision, posing a challenge for the ML process.

Density estimated using Gaussian kernel density estimation. This figure shows the correlation between elemental content (in atomic percent, a.t. %) and corrosion resistance (represented by the logarithm of the corrected current, ln(I_corr)). Each panel presents a scatter plot for a specific element (Al, Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu, Mn), with the x-axis corresponding to the elemental content and the y-axis to the logarithm of the corrosion current. A linear regression line is included to indicate the trend of the correlation. The color density, estimated using Gaussian kernel density estimation, represents the concentration of data points at specific locations within each plot. Correlation coefficients are displayed in each panel.

Figure 3 presents the distribution of different processing techniques and crystal structures in the HEA-CRD dataset, the distribution of literature on processing techniques in HEA research is uneven, leading to a pronounced long-tail distribution in the data. The terms and phrases in the dataset were directly extracted from the original sources. To avoid improper modifications of the original content and considering the automation requirements of the ML extraction process, no denoising, imputation, or alignment was performed on the extracted data. Due to the lack of standardized descriptions for processing techniques and crystal structures in the literature52, the dataset contains noise, coreference issues53, and missing information in these descriptions.

This figure shows the frequency distribution of processing technique and crystal structure-related terms. a displays the frequency of various processing technique words, with the x-axis representing the terms and the y-axis showing the count of their occurrences. The colors of the bars represent different categories of processing techniques. Abbreviations used in the figure are listed in the Supplementary Material, Table S1. b shows the frequency of crystal structure-related terms, with the x-axis representing crystal structure types and the y-axis showing the occurrence counts.

Overall, HEA-CRD does not impose restrictions on the processing techniques of HEAs, allowing for a larger dataset and greater diversity in processing methods. Training ML models using HEA-CRD facilitates the construction of intricate relationships among composition, processing, and corrosion resistance, contributing to the broader application of ML in engineering contexts by improving model generalizability and predictive precision. However, this diversity, along with the complexity of element distribution, poor correlation between elements and performance, and the variability in process descriptions, presents challenges for ML modeling54.

Evaluation of the precision of models

We implemented three frameworks using scikit-learn library55, with Random Forest (RF) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) as base models, and developed Mat-NRKG using the PyTorch library56. To evaluate the contribution of the structure prediction module in Mat-NRKG, we developed Mat-NRKGCPP, in which this module was omitted for comparison. All codes were implemented in Python. To enhance the reliability of experiments with small sample sizes, the data were split into training, validation, and test sets in a 4:1:1 ratio. Six random splits were performed, and the statistical results from these six experiments are reported.

The comparison of experimental results is shown in Table 1. Based on the MSE, MAE, and \({R}^{2}\) metrics, the results from the RF and MLP models across three frameworks indicate that the CPSP framework outperforms the CPP framework, which in turn performs better than the CP framework. This suggests that incorporating processing information and predicted crystal structure data enhances the model’s performance in predicting the corrosion resistance of HEAs, indirectly supporting the hypothesis that corrosion resistance is influenced by the combined effects of composition, processing, and crystal structure. Regarding the base models, RF generally performs better than the MLP model. A possible reason for this is that RF, as an ensemble learning method, exhibits stronger generalization capabilities in small-sample scenarios, effectively handling noise and complexity in the data. Compared to RFCPP, the inclusion of structural information in RFCPSP leads to a 3.1% improvement in \({R}^{2}\). For the MLP-based models, the improvement is more pronounced: MLPCPSP improves \({R}^{2}\) by 35.3% over MLPCPP. These results quantitatively shows the benefit of incorporating crystal structure information into the corrosion resistance prediction process.

In contrast, the Mat-NRKG model performs the best among all the compared models, particularly achieving a 25% improvement in the MSE metric over the best-performing comparison model (RFCPSP). This improvement further validates the effectiveness of integrating composition, processing information, and predicted crystal structure. Compared to its ablated version Mat-NRKGCPP, incorporating structure prediction in Mat-NRKG improves \({R}^{2}\) by 15.1%, showing its effectiveness in enhancing predictive precision. Additionally, the Mat-NRKGCPP model still performs slightly worse than the Mat-NRKG but surpasses all comparison models in precision. This indicates that the application of knowledge graphs and GCN-DTB module effectively combines numerical and semantic modalities, establishing correlations between the data and enhancing prediction performance in small-sample scenarios.

Figure 4 compares the predicted \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\) from the crystal structure prediction-based CPSP framework models and the Mat-NRKG model with experimental \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\) for the test set data. The results show that the predicted points from the Mat-NRKG model are more concentrated near the ideal prediction line, indicating superior performance in predicting corrosion current compared to the CPSP framework models.

Plots comparing predicted and experimental values of ln(Icorr) on the testing set using three different models: a RFCPSP, b MLPCPSP, and c Mat-NRKG. Each blue dot represents a data point from the testing set. The dashed diagonal line indicates the ideal case where predicted values exactly match experimental values. Points closer to the diagonal represent better predictive performance. Mat-NRKG shows a stronger alignment with the ideal line, suggesting improved predictive precision over RFCPSP and MLPCPSP.

Figure 5 shows histograms of the absolute error distributions for all test data, with the range covering the central 90% of the errors indicated. As shown, with the progressive inclusion of relevant information, the error distributions for the CP, CPP, and CPSP frameworks become more concentrated, indicating that the prediction errors for most data points decrease as more information is incorporated. Notably, the error distribution for the Mat-NRKG model is the most concentrated, with a shape approaching a normal distribution, further confirming the reliability and stability in predictions.

This figure shows the distribution of prediction errors for various models: a RFCP, b RFCPP, c RFCPSP, d MLPCP, e MLPCPP, f MLPCPSP, and g Mat-NRKG. The histograms illustrate the errors of each model, with the x-axis representing the errors in µA/cm² and the y-axis showing the density. The shaded regions indicate the central 90% of the data for each distribution. A smoothed probability density curve is overlaid on each histogram for better visualization of the distribution shape. The error range for the central 90% is listed for each model in the top of the respective plots.

Evaluation of the precision of structure prediction

To evaluate the modeling mechanisms of the CPSP framework and the Mat-NRKG model, this study assesses the crystal structure prediction as an intermediate stage in the overall framework

As shown in Table 2, for the crystal structure prediction task, the Mat-NRKG performs better than the CPSP framework in MRR, MR, and Hit@1 metrics. This demonstrates that the graph structure of the knowledge graph effectively captures and integrates unstructured process information, providing a advantage in crystal structure prediction. Additionally, all models achieve a Hit@1 score above 85%, indicating that the CPSP framework also yields promising results in crystal structure prediction task. Although both the CPP and CPSP frameworks take composition and processing information as inputs, the CPSP framework introduces an intermediate crystal structure prediction step, incorporating this structural information into subsequent property predictions. Embedding qualitative domain knowledge into data-driven models is inherently challenging, as such knowledge often involves complex causal relationships that are difficult to quantify. By leveraging the knowledge graph, the CPSP framework integrates explicit instances of how composition and processing influence corrosion resistance through modifications in crystal structure. This structured representation enables the model to learn not only the correlation but also the underlying mechanistic pathways linking material feature variables to performance. As a result, the model demonstrates improved performance on small-sample datasets, better alignment with real-world physical phenomena, and enhanced interpretability.

Validation of the generalizability of models

To further validate the model’s generalization ability, electrochemical tests were conducted on five HEAs synthesized in our laboratory using a casting process. Unlike the literature dataset used for model training, these samples were specifically prepared to provide independent experimental data, enabling an assessment of the model’s performance beyond the original dataset. The electrochemical measurements followed the procedures outlined in Sec. 3.8. The material composition, polarization curves, and electrochemical data extracted from the curves are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 6.

This figure presents the polarization curves for five synthesized HEAs, showing their electrochemical properties. The x-axis shows the corresponding current density (I) in milliamps, and the y-axis represents the potential (E) in millivolts. Each curve corresponds to a different HEA: HEA 1 (purple), HEA 2 (orange), HEA 3 (red), HEA 4 (green), and HEA 5 (blue).

To assess the suitability of the synthesized HEAs for generalization testing, we performed a t-SNE analysis on the compositional data. As shown in Fig. 7, the synthesized samples form a distinct cluster that deviates from the main distribution of the HEA-CRD dataset. This indicates that they represent unseen regions in the composition space, making them appropriate for evaluating the model’s generalization capability.

This figure presents a t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) visualization of the compositional distribution for High Entropy Alloy (HEA) data. The blue dots represent data points from HEA-CRD, while the red dot indicates a data point from HEA prepared in the lab. It shows how the data points from different sources are distributed in the compositional space and capture the similarity between data points. The clustering of data points suggests the similarity in compositional characteristics within each group.

Using the models trained in Sec. 2.2, the synthesized HEAs were tested, and the results are shown in Table 4. The CP framework, CPP framework, and CPSP framework demonstrate progressively improved predictive performance, with Mat-NRKG surpassing the other models, showing generalization ability.

Figure 8 presents a comparison of the CPSP framework models and the Mat-NRKG model for the predicted and experimental values of synthesized HEAs. The predicted values of the HEAs fall within the error range observed for both models on the test set, suggesting that both CPSP and Mat-NRKG models exhibit some level of generalization ability. Notably, the Mat-NRKG model shows good consistency with the testing on HEA-CRD, providing more accurate predictions of corrosion current densities for five different HEAs, and better reflecting the differences in corrosion resistance among the alloys, thus demonstrating superior performance.

Plots comparing predicted and experimental values of on the testing set using three different models: a RFCPSP, b MLPCPSP, and (c) Mat-NRKG. Each blue dot represents a data point from the testing set, while the red stars indicate data points for HEAs prepared in the lab. The dashed diagonal line represents the ideal case where the predicted values match exactly with the experimental values. Points that are closer to the diagonal line represent better predictive performance. Among the three models, Mat-NRKG exhibits a stronger alignment with the ideal line, indicating better predictive precision compared to RFCPSP and MLPCPSP.

Computational resource requirements are provided in the Supplementary Material, see Table S2.

Interpretability analysis

The CPSP framework and Mat-NRKG enhance interpretability by incorporating crystal structure as a physically meaningful intermediate variable that reflects part of the underlying material mechanisms. As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, the models with higher crystal structure prediction precision tend to yield better performance in corrosion resistance prediction, indicating that the inclusion of structure as an intermediate variable contributes to the model’s prediction process.

To further evaluate interpretability in the Mat-NRKG model, the learned embeddings of processing technique nodes were analyzed, and their pairwise similarities were visualized. As shown in Fig. 9, these embeddings were initialized randomly and trained without any explicit semantic labeling. After training, several meaningful similarities emerged. For example, processes such as laser re-melting, laser melting, laser cladding, and laser direct deposition showed strong similarity, corresponding to shared laser-based mechanisms. Other groups included coating-related techniques, casting-related operations such as argon gas atmosphere, arc re-melting, vacuum arc, arc furnace melting, casting, and argon gas casting, as well as cooling methods like furnace cooling, slow cooling, and water-cooled copper crucible furnace. These associations are consistent with established domain knowledge and suggest that the model has internally captured relevant relationships among processing techniques. Importantly, such learned associations help mitigate the “coreference issue”, where semantically identical or similar processing terms are written differently in the literature. By embedding these variations into a continuous representation space, the model reduces redundancy and noise caused by inconsistent terminology. Such representations may provide additional context for predicting material properties and support the model’s ability to generalize from diverse input data.

This figure visualizes the embedding similarity between processing technique nodes in a canonical knowledge graph. The nodes represent various processing techniques, with node size proportional to the frequency of occurrence of the techniques. The edges between the nodes indicate cosine similarity in their embedding space, with edge thickness reflecting the magnitude of the similarity. Red edges represent positive similarity, while blue edges correspond to negative similarity.

Significance and limitations of the framework

CPSP framework illustrates approaches to embedding domain knowledge—such as the intricate relationships between composition, processing, and crystal structure—into ML models. Capturing these dependencies within an ML framework is inherently challenging due to the qualitative nature of materials science knowledge and the complexity of composition-structure-processing-performance relationships. By leveraging diverse data and integrating structured prior knowledge, these frameworks establish a more unified and consistent predictive model, enhancing the interpretability and reliability of predictions.

Building upon this foundation, this study proposes the Mat-NRKG method, which advances this integration by explicitly utilizing a knowledge graph to encode composition and processing information. By aligning these features with crystal structure prediction, Mat-NRKG enables a more structured learning paradigm, improving the model’s ability to forecast HEA corrosion resistance. Compared to existing models, the Mat-NRKG model demonstrates superior predictive precision in evaluating HEA corrosion resistance, providing value for the rapid screening of materials in engineering applications.

It should be noted that the models are trained and evaluated using the logarithm of corrosion current density, \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\), which is a common practice in corrosion science due to the wide dynamic range and its alignment with electrochemical kinetics. However, even small deviations on the ln-scale may correspond to large absolute errors in linear scale, potentially impacting alloy screening in practical applications. Therefore, future work may consider incorporating dual-scale error control or calibration schemes for practical use.

Currently, the proposed models are limited to HEA corrosion resistance data measured under conditions of 25 °C (or room temperature) and 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Future work will focus on developing a dataset that includes corrosion resistance data under various experimental conditions. Additionally, the use of hyper-relational knowledge graphs will be explored to model data under different testing conditions, facilitating the development of an end-to-end predictive model that integrates composition, processing, and experimental conditions to further improve the model’s applicability and prediction precision.

Methods

Overview of HEA corrosion resistance prediction frameworks

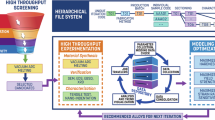

The Composition and Processing-Driven Two-Stage Corrosion Prediction Framework (CPSP Framework, Fig. 10c, details in Sec. 3.5) is proposed to predict the logarithm of corrosion current density \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\) of HEAs. This framework first predicts the crystal structure based on composition and processing information, and subsequently utilizes the predicted structure along with composition and processing conditions to estimate corrosion current. Building upon the conceptual foundation of CPSP, the NRKG-S method (Fig. 11, details in Sec. 3.6) is further developed, integrating knowledge graph technology45 to enhance predictive precision and improve model interoperability.

This figure presents three different frameworks for predicting the corrosion resistance of High Entropy Alloys. a Composition-Only Prediction Framework (CP Framework): The framework incorporates composition data, which is vectorized and fed into a base model to predict the logarithmic corrosion rate ln(Icorr). b Composition and Processing-Based Prediction Framework (CPP Framework): In addition to the composition data, this model integrates processing data. Processing techniques are represented as multi-hot encoded vectors, and the composition and processing data are merged before being passed to the base model for prediction. c Composition and Processing-Driven Two-Stage Corrosion Prediction Framework with Structural Prediction (CPSP Framework): This model further extends the framework by incorporating a prediction structure that accounts for crystal structure. Composition and processing data are merged, and the model predicts the corrosion resistance based on this extended input. Each model progressively adds more variables to improve the prediction of HEA corrosion resistance, with the final output being the predicted logarithmic corrosion rate ln(Icorr).

This figure shows the Mat-NRKG method for predicting HEA corrosion resistance. It integrates composition and processing data through separate encoders, uses a knowledge graph to predict crystal structures with the TransE algorithm, and then predicts the corrosion current (ln(Icorr)) using a GCN-DTB decoder.

To establish comparative baselines, two conventional frameworks are designed: the Composition-Only Prediction Framework (CP Framework, details in Sec. 3.3), which estimates corrosion current based solely on composition, and the Composition and Processing-Based Prediction Framework (CPP Framework, details in Sec. 3.4), which incorporates both composition and processing conditions as input features. The CP, CPP, and CPSP frameworks allow flexibility in the selection of ML models as base model, theoretically accommodating most regression and classification methods. For implementation, Random Forest (RF)57 and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)58 are chosen as the base models (details in Sec. 3.2), given their widespread application in materials property prediction. The subsequent sections provide a comprehensive description of each framework and method.

Base model

The Random Forest (RF) model57 is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees on randomly sampled data subsets. The final prediction is obtained by averaging individual tree outputs:

where \(n\) is the number of trees and \(x\) is the input feature vector. RF is effective for high-dimensional, noisy data due to its robustness and interpretability.

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)58 is a feedforward neural network that learns complex feature interactions through multiple nonlinear transformations:

where, \({{\bf{h}}}^{(l)}\) is the output of layer \(l\), and \(f(\cdot )\) is the activation function. MLP excels in capturing nonlinear patterns, making it suitable for intricate prediction tasks.

Composition-only prediction framework

As shown in Fig. 10a, the Composition-Only Prediction Framework (CP Framework) directly predicts the corrosion current \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\) using only the compositional information of HEAs. The atomic percentages of Al, Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Cu, and Mn in the HEA composition are represented as a 7-dimensional vector (compositional features), which is normalized before being input into the base model for training and prediction. In this study, RF and MLP are employed as the base models. Serving as a baseline, the CP Framework provides a fundamental assessment of the predictive capability of compositional features alone, facilitating comparison with more advanced frameworks.

Composition and processing-based prediction framework

As shown in Fig. 10b, the Composition and Processing-Based Prediction Framework (CPP Framework) integrates compositional and processing information of HEAs to enhance the prediction of corrosion current \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\). Processing information, described by phrases, cannot be directly input into the model due to the variability in the number of processing associated with each HEA. To address this, all possible processing conditions are listed as a feature set. For each HEA, a fixed-length vector is maintained, where each position corresponds to a specific processing condition. If a particular processing method is applied, the corresponding position in the vector is marked as “1”; otherwise, it is marked as “0”. This approach constitutes a multi-hot encoding scheme59, enabling the transformation of categorical processing information into a structured numerical format suitable for ML models. The advantage of multi-hot encoding lies in its ability to represent multiple processing conditions simultaneously while maintaining a consistent input size across all samples. After concatenating compositional features (consistent with Sec. 3.3) and processing encodings, the combined input is fed into the base model for training and prediction. By incorporating processing information, the model captures the relationships between composition, processing, and corrosion current. In this study, the base model is implemented using RF and MLP. As an extension beyond the CP Framework, the CPP Framework serves as another baseline, allowing evaluation of the impact of both compositional and processing information on corrosion prediction.

Composition and processing-driven two-stage corrosion prediction framework with structural prediction

Given that processing can influence the crystal structure, which in turn affects corrosion resistance, yet directly including structure as an input parameter limits the model’s engineering applicability due to the need for experimental or computational determination, Fig. 10c shows the Composition and Processing-Driven Two-Stage Corrosion Prediction Framework with Structural Prediction (CPSP Framework). In the first stage, the framework takes compositional and processing information as inputs (consistent with Sec. 3.3) and uses a multiclass classifier to predict the crystal structure type of the multi-hot encoded material. Crystal structure labels extracted from the literature are used to supervise the training of this stage, and also serve as ground truth for evaluating prediction precision during testing. In the second stage, compositional and processing features, along with the predicted crystal structure from the first stage, are concatenated and input into the base model to further predict corrosion current. This method, by introducing the intermediate variable predicted crystal structure, may be able to capture the indirect effects of composition and processing on corrosion resistance performance. The first stage is a multiclass classification task, and the base model selected is a classifier such as RF or MLP. To ensure comparability, the same base model (RF or MLP) is used in both stages of the framework.

Mat-NRKG

While the CPSP framework incorporates a physically meaningful intermediate step by introducing crystal structure prediction, which reflects how composition and processing affect material behavior, its two-stage design results in a gap between the first stage and corrosion resistance performance. To bridge this gap and further build upon the CPSP framework, inspired by Song et al.45 the Mat-NRKG method is proposed. Additionally, the compositional complexity of HEAs, along with the impact of composition and processing techniques on crystal structure and corrosion resistance, poses challenges for accurate property prediction. The numerical reasoning method for material knowledge graphs (NR-KG)45 was the first to construct a cross-modal knowledge graph, integrating heterogeneous numerical and semantic representations of composition, processing, and crystal structure into a unified modeling framework. However, NR-KG relies on crystal structure as an explicit input, limiting its applicability in scenarios where structural data is impractical to obtain through experiments or simulations. To address this limitation, the CPSP framework’s concept of predicting crystal structure is leveraged to enhance NR-KG, allowing structure prediction from composition and processing information while maintaining a unified knowledge-driven reasoning process. This modification has the potential to improve model generalizability and reduce dependency on explicit structural data, thereby potentially enhancing its applicability in engineering applications for corrosion resistance prediction.

As shown in Fig. 11, the canonical knowledge graph encodes numerical (composition) and semantic (processing, crystal structure) data in a graph structure. Specifically, the composition, processing, and candidate crystal structures of HEAs are modeled as nodes in the knowledge graph. The relationships between nodes are constructed based on the compositional ratios, processing techniques, and their potential impact on crystal structure. Compared to multi-hot encoding method, the topological structure of the knowledge graph allows for a more flexible capture of multidimensional semantic information46, especially in cases where processing techniques are complex and variable. Each node in the canonical knowledge graph records relevant feature information: composition data is extracted by the Composition Encoder, which uses an MLP-based embedding network to map the 7-dimensional atomic percentage vector to a low-dimensional feature vector. Specifically, this process effectively performs an embedding transformation, projecting the original composition data into a continuous vector space while aligning it with the dimensionality of node embeddings. This transformation enhances feature expressiveness and facilitates integration with the overall knowledge graph representation. Processing data is handled by the Processing Embedding module, which uses an embedding lookup method60 to learn optimizable embeddings for each processing parameter. Specifically, since processing nodes are inherently discrete, this module follows a strategy inspired by natural language embedding techniques: it first initializes feature embeddings randomly and then refines them through iterative optimization during the training process. This approach ensures that the learned embeddings capture meaningful relationships among different processing techniques, improving the knowledge graph’s ability to encode process-related semantics.

The crystal structure prediction task for HEAs is modeled as a link prediction task within the canonical knowledge graph, where the goal is to determine the probability of a connection between an HEA node and a candidate crystal structure node. Specifically, this involves assessing the likelihood that a given HEA composition adopts a particular crystal structure, based on the relationships encoded in the knowledge graph. To achieve this, the TransE algorithm47 is employed to model these connections and predict potential structural configurations. For a triplet in the knowledge graph, \((h,r,t)\), where \(h\) is the head node, \(r\) is the relationship, and \(t\) is the tail node, the TransE algorithm optimizes the following objective function:

where \({\bf{h}}\), \({\bf{r}}\), and \({\bf{t}}\) are the embedding vectors for nodes \(h\), relationship \(r\), and node \(t\), respectively, and \({\Vert \cdot \Vert }_{2}\) denotes the \({L}_{2}\) norm. By minimizing the distance \({\mathcal L}\), the TransE algorithm effectively integrates both node features (such as composition information) and the knowledge graph’s topological structure (which encodes the semantic similarity between processing techniques). This enables the model to capture the potential influence of composition and processing parameters on the resulting crystal structure, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to reproduce and learn complex structure-related patterns, which contributes to improved predictive performance in downstream tasks such as corrosion resistance prediction.

After the structure prediction, the model further utilizes a GCN-DTB module, which combines a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)48 decoder with a Deep Taylor Block (DTB) module49, to aggregate multi-layered information from the HEA node and its neighboring nodes (processing and structure nodes) in the canonical knowledge graph. This captures the complex effects of composition, processing, and structure on corrosion performance to predict the corrosion current. The GCN-based prediction expression is given by:

where \({h}_{u}^{(l-1)}\) represents the feature of the neighboring node \(u\) at layer \(l-1\), \({c}_{uv}\) is the normalization factor for adjacent nodes, \({W}^{(l)}\) is the weight matrix, and \(\sigma\) is the activation function. The DTB module helps reduce the impact of data noise on the modeling process.

Mat-NRKG adopts the core concept of the CPSP framework, where compositional and processing information is first used to predict crystal structure, followed by the integration of all information for corrosion resistance prediction. Compared to CPSP, Mat-NRKG transforms the two-stage prediction process into an end-to-end prediction within the knowledge graph framework. By modeling semantic relationships in the knowledge graph, the framework improves the fusion of composition and processing data and leverages the GCN’s neighborhood aggregation mechanism to capture complex multi-factor interactions.

Evaluation metrics

This study uses the polarization method to measure \(\mathrm{ln}({I}_{corr})\) as an indicator of the corrosion resistance of HEAs, which is considered a standard approach in corrosion science for evaluating electrochemical behavior16,61,62. Accordingly, we use regression-based metrics including Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (\({R}^{2}\)) to evaluate model performance, as they are widely adopted in the literature for assessing predictive precision in materials informatics63,64. The metrics are defined as:

where \({y}_{i}\) and \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) are the true and predicted values for sample \(i\), \(\bar{y}\) is the mean of the true values, and \(N\) is the total number of samples.

Additionally, the CPSP framework and Mat-NRKG method proposed here can predict the crystal structure. To evaluate the effectiveness of this task, we use the Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), Mean Rank (MR), and Hit@1, defined as:

where \(ran{k}_{i}\) denotes the rank of the correct answer for sample \(i\), and \({\rm{Correct}}@1\) is the number of correct predictions at rank 1.

Electrochemical measurements

To validate the model performance, electrochemical measurements were conducted on five laboratory-synthesized HEAs prepared by a casting process. Electrochemical tests were performed using a Gamry Reference 600+ electrochemical workstation. The HEA samples were fabricated via a casting process and subsequently cured at room temperature for 24 h. Prior to testing, the samples were sequentially polished with 400#, 800#, 1600#, and 3000# sandpaper to achieve a uniform surface finish. The samples were then cleaned ultrasonically in anhydrous ethanol for 5 minutes and dried with cold air.

Electrochemical measurements were conducted in a 3.5% NaCl solution at room temperature using a conventional three-electrode setup. The working electrode (WE) was the synthesized HEA, embedded in epoxy resin with a single exposed surface of 1 \({{\rm{cm}}}^{2}\). A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as the reference electrode (RE), and a platinum plate (2 cm \(\times\) 2 cm) was used as the counter electrode (CE). The SCE was commercially pre-calibrated, and its stability was confirmed by repeated open-circuit potential (OCP) measurements and comparison with a standard redox couple.

Prior to polarization testing, the samples were immersed in the NaCl solution for 4 h to stabilize the surface condition and reach electrochemical equilibrium. The OCP was then monitored, and once it remained within ±2 mV for at least 10 min, the polarization scan was initiated. The potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) test started at –0.2 V relative to OCP and proceeded to +2 V versus the reference electrode, with a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s and a termination current of 1 mA/cm2.

The corrosion current density \({I}_{corr}\) and corrosion potential \({E}_{corr}\) were extracted from the polarization curves using EC-Lab software (Version 9.32). To minimize the influence of passivation behavior observed in the anodic branch, only the cathodic Tafel region was selected for extrapolation. A linear fit was performed on the cathodic branch within the region that exhibited a clear Tafel slope. The \({I}_{corr}\) value was obtained by extending the fitted cathodic line to intersect the potential corresponding to the minimum current on the polarization curve. \({E}_{corr}\) was determined as the potential at which the anodic and cathodic branches intersected. This cathodic extrapolation method was adopted to improve the precision and stability of the electrochemical parameter extraction in HEAs exhibiting partial anodic passivation.

Data availability

The data is publicly available at https://github.com/MatrixBrain/NR-KG/tree/main/dataset.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tung, C.-C. et al. On the elemental effect of AlCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system. Mater. Lett. 61, 1–5 (2007).

Birbilis, N., Choudhary, S., Scully, J. & Taheri, M. A perspective on corrosion of multi-principal element alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 14 (2021).

Kim, J. H., Lim, K. R., Won, J. W., Na, Y. S. & Kim, H.-S. Mechanical properties and deformation twinning behavior of as-cast CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy at low and high temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 712, 108–113 (2018).

Bae, J. W. et al. Trade-off between tensile property and formability by partial recrystallization of CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 703, 324–330 (2017).

Kim, Y.-K., Joo, Y.-A., Kim, H. S. & Lee, K.-A. High temperature oxidation behavior of cr-mn-fe-co-ni high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 98, 45–53 (2018).

Wang, Y., Zhang, M., Jin, J., Gong, P. & Wang, X. Oxidation behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy after plastic deformation. Corros. Sci. 163, 108285 (2020).

Kai, W. et al. The corrosion of an equimolar FeCoNiCrMn high-entropy alloy in various CO2/CO mixed gases at 700 and 950°. Corros. Sci. 153, 150–161 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Influence of plastic deformation on the corrosion behavior of CrCoFeMnNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 891, 161822 (2022).

Wang, Z., Li, D., Yao, Y.-Y., Kuo, Y.-L. & Hsueh, C.-H. Wettability, electron work function and corrosion behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 400, 126222 (2020).

Torbati-Sarraf, H., Shabani, M., Jablonski, P. D., Pataky, G. J. & Poursaee, A. The influence of incorporation of mn on the pitting corrosion performance of CrFeCoNi high entropy alloy at different temperatures. Mater. Des. 184, 108170 (2019).

Jin, Z. et al. Effect of annealing temperature on the microstructure evolution and corrosion behavior of carbon-interstitial FeMnCoCrNi high-entropy alloys. Corros. Sci. 228, 111813 (2024).

Sasidhar, K. N. et al. Deep learning framework for uncovering compositional and environmental contributions to pitting resistance in passivating alloys. Npj Mater. Degrad. 6, 71 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Interpretability study on prediction models for alloy pitting based on ensemble learning. Corros. Sci. 228, 111790 (2024).

Sathiyamoorthi, P. & Kim, H. S. High-entropy alloys with heterogeneous microstructure: Processing and mechanical properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 123, 100709 (2022).

Sonar, T., Ivanov, M., Trofimov, E., Tingaev, A. & Suleymanova, I. An overview of microstructure, mechanical properties and processing of high entropy alloys and its future perspectives in aeroengine applications. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 7, 35–60 (2024).

Fu, Y., Li, J., Luo, H., Du, C. & Li, X. Recent advances on environmental corrosion behavior and mechanism of high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 80, 217–233 (2021).

Xu, W., Diesen, E., He, T., Reuter, K. & Margraf, J. T. Discovering high entropy alloy electrocatalysts in vast composition spaces with multiobjective optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7698–7707 (2024).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater.122, 448–511 (2017).

Rao, Z. et al. Machine learning–enabled high-entropy alloy discovery. Science 378, 78–85 (2022).

Liu, M., Lei, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, B. & Qu, X. High-throughput preparation for alloy composition design in additive manufacturing: a comprehensive review. Mater. Genome Eng. Adv. 2, e55 (2024).

Ji, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence combined with high-throughput calculations to improve the corrosion resistance of AlMgZn alloy. Corros. Sci. 233, 112062 (2024).

Vitos, L. Computational quantum mechanics for materials engineers: the EMTO method and applications (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Lee, C. et al. Temperature dependence of elastic and plastic deformation behavior of a refractory high-entropy alloy. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4748 (2020).

Schleder, G. R., Padilha, A. C., Acosta, C. M., Costa, M. & Fazzio, A. From DFT to machine learning: Recent approaches to materials science–a review. J. Phys.: Mater. 2, 032001 (2019).

Yip, S. & Short, M. P. Multiscale materials modelling at the mesoscale. Nat. Mater. 12, 774–777 (2013).

Ward, L., Agrawal, A., Choudhary, A. & Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 1–7 (2016).

Ren, F. et al. Accelerated discovery of metallic glasses through iteration of machine learning and high-throughput experiments. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq1566 (2018).

Mamun, O., Wenzlick, M., Sathanur, A., Hawk, J. & Devanathan, R. Machine learning augmented predictive and generative model for rupture life in ferritic and austenitic steels. Npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 20 (2021).

Ren, J.-C. et al. Predicting single-phase solid solutions in as-sputtered high entropy alloys: high-throughput screening with machine-learning model. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 138, 70–79 (2023).

Wei, Q. et al. Discovering a formula for the high temperature oxidation behavior of FeCrAlCoNi based high entropy alloys by domain knowledge-guided machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 149, 237–246 (2023).

Jin, X. et al. Data mining accelerated the design strategy of high-entropy alloys with the largest hardness based on genetic algorithm optimization. Mater. Genome Eng. Adv. 2, e49 (2024).

Zhao, X., Huang, H., Su, Y., Qiao, L. & Yan, Y. Exploring high corrosion-resistant refractory high-entropy alloy via a combined experimental and simulation study. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 77 (2024).

Qiao, L., Ramanujan, R. & Zhu, J. Machine learning accelerated design of a family of AlxCrFeNi medium entropy alloys with superior high temperature mechanical and oxidation properties. Corros. Sci. 211, 110805 (2023).

Dong, Z. et al. Machine learning-assisted discovery of cr, al-containing high-entropy alloys for high oxidation resistance. Corros. Sci. 220, 111222 (2023).

Song, G. et al. Bridging the semantic-numerical gap: a numerical reasoning method of cross-modal knowledge graph for material property prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09744 (2023).

Beckh, K. et al. Explainable machine learning with prior knowledge: an overview. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.10172 (2021).

Oviedo, F., Ferres, J. L., Buonassisi, T. & Butler, K. T. Interpretable and explainable machine learning for materials science and chemistry. Acc. Mater. Res. 3, 597–607 (2022).

Luo, H. et al. A strong and ductile medium-entropy alloy resists hydrogen embrittlement and corrosion. Nat. Commun. 11, 3081 (2020).

Miracle, D. B. et al. Exploration and development of high entropy alloys for structural applications. Entropy 16, 494–525 (2014).

Takeuchi, A. et al. Entropies in alloy design for high-entropy and bulk glassy alloys. Entropy 15, 3810–3821 (2013).

Yang, X. & Zhang, Y. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 132, 233–238 (2012).

Ye, Y., Wang, Q., Lu, J., Liu, C. & Yang, Y. Design of high entropy alloys: A single-parameter thermodynamic rule. Scr. Mater.104, 53–55 (2015).

Gao, M. C. et al. Computational modeling of high-entropy alloys: structures, thermodynamics and elasticity. J. Mater. Res. 32, 3627–3641 (2017).

Wu, M., Wang, S., Huang, H., Shu, D. & Sun, B. CALPHAD aided eutectic high-entropy alloy design. Mater. Lett. 262, 127175 (2020).

Song, G., Fu, D. & Zhang, D. From knowledge graph development to serving industrial knowledge automation: A review. in 2022 41st chinese control conference (CCC) 4219–4226 (IEEE, 2022).

Hogan, A. et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–37 (2021).

Bordes, A., Usunier, N., Garcia-Duran, A., Weston, J. & Yakhnenko, O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 26, 1–9 (2013).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2017).

Song, G., Fu, D., Qiu, Z., Meng, J. & Zhang, D. Taylor-sensus network: Embracing noise to enlighten uncertainty for scientific data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.07942 (2024).

Wissler, C. The spearman correlation formula. Science 22, 309–311 (1905).

Iversen, G. R. & Gergen, M. (eds.) Statistics, the Conceptual Approach. (Springer, New York, 1997).

Hill, J. et al. Materials science with large-scale data and informatics: Unlocking new opportunities. Mrs Bull. 41, 399–409 (2016).

Peng, H., Khashabi, D. & Roth, D. Solving hard coreference problems. Proc. Conf. North Am. Chapter Assoc. Comput. Linguist. Hum. Lang. Technol. 809–819 (2015).

Kumar, P., Bhatnagar, R., Gaur, K. & Bhatnagar, A. Classification of imbalanced data: review of methods and applications. In IOP conference series: Materials science and engineering vol. 1099 012077 (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Paszke, A. Pytorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 32, 8024–8035 (2019).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: a review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Heidari, A. A., Faris, H., Aljarah, I. & Mirjalili, S. An efficient hybrid multilayer perceptron neural network with grasshopper optimization. Soft Comput. 23, 7941–7958 (2019).

Li, B. et al. EMU: Effective multi-hot encoding net for lightweight scene text recognition with a large character set. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 5374–5385 (2022).

Church, K. W. Word2Vec. Nat. Lang. Eng. 23, 155–162 (2017).

Qiu, Y., Thomas, S., Gibson, M. A., Fraser, H. L. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion of high entropy alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 1, 15 (2017).

Qiu, Y., Gibson, M., Fraser, H. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion characteristics of high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1235–1243 (2015).

Xu, P., Ji, X., Li, M. & Lu, W. Small data machine learning in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 42 (2023).

Hart, G. L., Mueller, T., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. Machine learning for alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 730–755 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFF0728900) and the National Environmental Corrosion Platform of China (KXJS2023002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, conducted data curation, and drafted the original manuscript. D.F. oversaw project administration, provided supervision, and contributed to conceptualization. Y.L. was responsible for resources and data curation. L.M. and D.Z. supervised the study and contributed to writing, review, and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, G., Fu, D., Lin, Y. et al. Corrosion resistance prediction of high-entropy alloys: framework and knowledge graph-driven method integrating composition, processing, and crystal structure. npj Mater Degrad 9, 81 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00632-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00632-4