Abstract

This study investigates the long-term corrosion behavior of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi MPEAs over 28 d in 1 M H2SO4. Corrosion progression and passive film evolution were analyzed using open circuit potential measurements, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy. Unlike short-term polarization tests, where CrCoNi exhibited intergranular corrosion, long-term immersion resulted in a stable, Cr-rich passive oxide layer. In contrast, CrMnFeCoNi formed a porous mixed oxide layer, increasing its susceptibility to degradation and revealing a distinct corrosion mechanism. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy tracking at weekly intervals showed that prolonged immersion led to the transformation of sulfide/sulfite species into a sulfate-containing surface film. This effect was only detectable in long-term corrosion studies. These findings provide new insights into the time-dependent degradation mechanisms of MPEAs and demonstrate that corrosion mechanisms differ significantly from short-term polarization tests. This highlights the need for long-term studies to properly assess material stability in practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, multi-principal element alloys (MPEAs) have gained significant attention in materials science due to their unique combination of properties, including high corrosion resistance, wear resistance, thermal stability, and hardness1. MPEAs, also referred to as high-entropy alloys (HEAs) and medium-entropy alloys (MEAs), are defined by their composition of three or more principal elements in nearly equal atomic concentrations2. Their ability to form single-phase solid solutions without intermetallic phases contributes to their robustness, making them promising candidates for industrial applications that demand high durability and resistance to harsh environments3,4,5. While most studies on MPEAs have focused on synthesis, crystallization processes, and their mechanical and physical properties6,7,8, their corrosion behavior is gaining increasing scientific and industrial interest, particularly for applications as bulk materials9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and protective coatings18,19,20. Compared to conventional stainless steels (SS), MPEAs offer several key advantages and have demonstrated unconventional behavior. For example, while structural heterogeneity in SS often increases corrosion susceptibility, MPEAs have been observed to maintain their resistance despite their heterogeneous microstructure21,22.

Although extensive research has shown that MPEAs generally exhibit good initial corrosion resistance, systematic studies on their long-term performance, passive film evolution, and degradation mechanisms remain scarce23,24,25. This lack of long-term understanding limits the reliable application of MPEAs in service environments. Rodriguez et al.24 provided key insights into the corrosion behavior of CrMnFeCoNi by comparing it to SS 316 L using both long-term immersion tests and electrochemical polarization measurements in a Cl-containing electrolyte solution. During long-term corrosion testing, CrMnFeCoNi alloys with higher Cr content exhibited lower corrosion rates, while those without Cr underwent severe metal dissolution. In contrast, electrochemical polarization measurements showed that all CrMnFeCoNi alloys - except those with no Cr - were susceptible to pitting corrosion, whereas the Cr-free alloy experienced general corrosion. A recent study by Wu et al.26 further demonstrated that a non-equiatomic FeNiCoCr alloy exhibited superior corrosion resistance in both electrochemical polarization and long-term immersion tests compared to CrMnFeCoNi and 316 L stainless steel in 0.1 M H₂SO₄ solution. However, the immersion tests provided stronger evidence of its passive film stability over time. In contrast, CrMnFeCoNi, which initially showed passivation in polarization tests, suffered severe degradation after prolonged exposure. These results highlight that short-term electrochemical tests alone are not sufficient for the elucidation of the corrosion resistance of alloys and long-term studies are crucial for understanding passive film stability and material degradation under real-world conditions.

Furthermore, the results of Wu et al.26 suggest that compositional tuning, particularly the elimination of Mn, plays a crucial role in enhancing the stability of the passive film and mitigating corrosion-related degradation. This is consistent with previous findings that Mn has a destabilizing effect on passive films in CrMnFeCoNi alloys, leading to reduced overall corrosion resistance27. The competitive oxidation between Mn and Cr lowers the Cr₂O₃ content in the passive film, resulting in weaker, porous oxides that compromise passivity28. In contrast, Cr is well known for its ability to form stable passive films in various transition metal alloys, including conventional Ni-Cr alloys and stainless steel29,30. Cr-containing MPEAs often form Cr(III)-enriched passive layers, which serve as protective barriers against aggressive species31,32. However, in some cases, Cr-containing MPEAs have even exhibited inferior corrosion resistance compared to stainless steels. A study by Chen et al.33 found that the as-cast Cu₀.₅NiAlCoCrFeSi alloy demonstrated superior general corrosion resistance compared to 304 stainless steel in H₂SO₄ electrolyte. However, it lacked the capacity to form a passive film and thus was more prone to corrosion in 0.1 M NaCl.

Recent studies have also explored the role of Mo in enhancing the corrosion resistance of Cr-containing HEAs. Wang et al.34 demonstrated through CALPHAD-based simulations and electrochemical experiments that Mo additions up to 10 at% significantly improve passivity and resistance to chloride-induced breakdown in CrFeCoNi-based single-phase FCC alloys. The beneficial effect is attributed to the stratified passive film structure, where Mo oxides enrich the outer layer while Cr oxides form a protective inner barrier. Similarly, Czerski et al.35 found that in AlCrFe2Ni2Mox alloys, moderate Mo additions (up to x = 0.3) improve corrosion resistance by promoting mixed (Cr, Mo)-based passive layers, whereas excessive Mo leads to phase segregation and the formation of σ-phase, degrading corrosion resistance. These findings highlight that moderate Mo additions can complement the passivating role of Cr, provided the alloy maintains a single-phase microstructure and avoids Mo-rich intermetallic precipitates.

In a recent study36, we reported that the equiatomic CrCoNi alloy exhibited higher corrosion resistance in 0.1 M H2SO4 (pH < 1) than both CrMnFeCoNi (Cantor alloy) and AISI 304 SS. Cyclic potentiodynamic polarization (CPP) measurements confirmed this by revealing that CrCoNi had the lowest current densities in the passive region, indicating the formation of a more stable oxide layer compared to the other alloys. Under these conditions, intergranular corrosion was observed. The oxide layer on CrCoNi after anodic passivation consisted primarily of Cr oxides, providing a robust protective barrier. In contrast, the passive film on CrMnFeCoNi is composed mainly of Cr and Fe oxides, leading to a less stable and porous passive film.

Several studies have emphasized the need for deeper investigations into the mechanistic aspects underlying the corrosion resistance of MPEAs37,38,39. However, research on these mechanisms is still in its early stages. Luo et al.39 compared the corrosion behavior of CoCrFeMnNi and stainless steel in 0.1 M H2SO4, demonstrating that both materials form passive films and follow similar corrosion mechanisms. Their study employed X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze the passive film composition, yet the use of this technique in MPEA research has remained limited40,41,42,43. This is primarily due to the strong interference of various Auger transitions with the 2p core-level peaks of transition metals, making the analysis particularly challenging36,41. To address this issue, Wang et al.41 proposed the use of 3p photoelectron lines, such as Cr 3p, which offer improved resolution and reduced spectral overlap. This methodological refinement enables more reliable surface analysis and supports a more accurate interpretation of passive film composition in complex alloys. Together, these insights underscore the need for advanced and carefully selected surface analysis techniques when studying passive films in MPEAs.

Technical applications in areas currently dominated by the use of stainless steels require long-term corrosion resistance and electrochemical stability under service conditions. However, despite the promising properties of MPEAs, systematic long-term corrosion studies are still limited. To address this gap, this study provides a detailed analysis of the long-term corrosion behavior of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi MPEAs in 1 M H2SO4, with particular focus on passive film evolution and degradation. Through a combination of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), XPS, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), we demonstrate the superior corrosion resistance of CrCoNi, attributed to the formation of a stable Cr-rich passive layer. Additionally, we clarify the differences in corrosion mechanisms between CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi by comparing their behavior in 0.1 M H2SO436 to their response under the more aggressive conditions in 1 M H2SO4 examined in this study.

Results

Long-term corrosion studies

The long-term corrosion behavior of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi was assessed through immersion tests in 1 M H2SO4 over a period of 28 d, with open circuit potenital (EOCP) and EIS measurements conducted 56 times at regular intervals. The EIS data were fitted using the electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) shown in Fig. 1. To effectively convey the time-dependent evolution of the electrochemical behavior, the EIS results are displayed as two-dimensional color maps. Figures 2a, b plot frequency on the y-axis and immersion time on the x-axis, with the color scale representing either the impedance magnitude (Fig. 2a) or the phase angle (Fig. 2b). The impedance magnitude is shown using a color gradient ranging from red (high impedance) to purple/blue (low impedance). High-frequency responses are primarily associated with solution resistance, while changes at low frequencies reflect interfacial processes at the electrode surface. In Fig. 2b the phase angle is similarly visualized, where values near −90° are shown in purple/blue and indicate capacitive behavior while shifts toward 0° are shown in red and suggest a more resistive or charge-transfer-dominated response. This representation offers an intuitive overview of changes in the impedance spectrum over time and is particularly useful for identifying trends such as the formation or degradation of passive films across a broad frequency range.

For CrCoNi, the maps clearly demonstrate the formation of a highly stable passive layer, as evidenced by the consistently high impedance values and phase angles close to −90° in the frequency range of 103 < f < 10−1 Hz, reflecting nearly perfect capacitor-like behavior. This suggests that the passive layer serves as an effective barrier to charge transfer, significantly reducing the corrosion rate of the alloy. This pronounced capacitive response highlights the ability of the passive film to suppress metal dissolution, thereby enhancing the overall corrosion resistance of CrCoNi during prolonged exposure to the acidic environment. Figures 2c, d present selected EIS data from the impedance and phase shift maps in Fig. 2a, b, showing measurements at 7 d intervals throughout the immersion period of 28 d, including 0 d (initial immersion). The data reveal that during the first 7 d the impedance at 10 mHz stabilized at 530 kΩ cm². Additionally, the phase shift minima exhibited a slight increase, starting at −84° initially and reaching −87° by the end of the experiment after 28 d.

The corresponding Nyquist diagram for all immersion times in Fig. 2e reveals oblique lines whose magnitude increases with immersion time. Employing the EEC in Fig. 1, data fitting (with χ2 values of the order of 10−3) indicates that the surface processes can be modeled with one constant phase element (CPEf) with αf = 0.95 to 0.97 representing a non-ideal capacitor, and one CPEdl, which functions as a Warburg element with αdl = 0.5. High-frequency responses are attributed to electrode and electrolyte resistance, while low-frequency responses are associated with diffuse layer resistance44. At initial immersion (0 d), CrCoNi exhibits a relatively shallow Nyquist plot, whereas the plots for subsequent immersion times show similar extents. This consistency in the impedance of CrCoNi, as also shown in the Bode and Nyquist diagrams (Fig. 2c, d), indicates a stable system with minimal change after 7 d of immersion.

Electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) employed to fit the EIS data of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi. Rs is the resistance of the electrolyte. A constant phase element CPEf and a resistor Rf are used to model the resistance of the passive film. CPEdl represents the constant phase element for the electric double layer, while Rct accounts for the charge transfer resistance. RE and WE denote the reference and working electrode, respectively.

Development of impedance and phase shift of CrCoNi during 28 d of immersion in 1 M H₂SO₄, showing (a) a color map of impedance magnitude as a function of frequency (y-axis) and time (x-axis), and b the corresponding phase shift map as a function of frequency (y-axis) and time (x-axis). Selected measurements after 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 d are shown in: c impedance magnitude, d phase shift, and e Nyquist representation, illustrating the changes in the electrochemical response. In (c–e), the original measured data are marked with crosses, while the fitted data are shown as straight lines. f EOCP development throughout the immersion period of 28 d, starting from 150 mV.

The corrosion resistance of CrCoNi is further illustrated by the development of the EOCP over the time of immersion. Each EOCP measurement was taken for 1800 seconds, and a value from the stable range was selected and plotted against the immersion time in Fig. 2f. For CrCoNi, the EOCP increased from 150 mV to 325 mV during the first 7 d, indicating the formation of a passive layer (Fig. 2f). From 8 d onwards, the EOCP stabilized at approximately 335 mV, which is in good agreement with the EIS data and further confirms the protective nature of the passive film.

The bar graph in Fig. 3 illustrates the fraction of dissolved metal ions of CrCoNi in a 1 M H2SO4 electrolyte solution, analyzed by ICP-MS. Generally, the analysis of dissolved metal species for CrCoNi shows dissolved concentrations ≤ 1 µmol L−1. The relative amount of dissolved Cr, Co, and Ni ions was calculated as xi = ci/(cCr + cCo + cNi) with i = [Cr, Co, Ni]. A lower fraction of Cr ions (19.9%) was released compared to Co (31.1%) and Ni (49.0%).

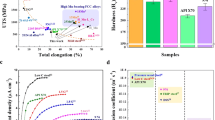

The results of the EIS analysis of CrMnFeCoNi are presented in Fig. 4, using the same time-resolved map format as described for Fig. 2a, b to enable direct comparison. Figure 4a, b illustrate the evolution of impedance and phase angle across the full frequency range over the 28-day immersion period. The significant increase of impedance on day 2 suggests initial passive film formation. However, both impedance and phase angle steadily decrease afterwards, indicating progressive degradation of the surface film over time.

Development of impedance and phase shift of CrMnFeCoNi during 28 d of immersion in 1 M H₂SO₄, showing a a color map of impedance magnitude as a function of frequency (y-axis) and time (x-axis), and b the corresponding phase shift map as a function of frequency (y-axis) and time (x-axis). Selected measurements after 0, 2, 7, 14, 21, 23, and 28 d are shown in (c) impedance magnitude, d phase shift, and e Nyquist representation, illustrating the changes in the electrochemical response. In (c, d), the original measured data are marked with crosses, while the fitted data are shown as straight lines. f EOCP development throughout the 28 d immersion period, starting from 350 mV.

Selected EIS data (Fig. 4c, d) extracted from the impedance and phase shift maps further illustrate this trend, showing measurements taken at 7 d intervals throughout the 28 d immersion, including 0 d (initial immersion), as well as 2 d and 23 d to capture the dynamic changes more precisely. The electrochemical data show a large dynamic of changes in the interfacial properties of CrMnFeCoNi, and therefore additional data points for 2 d and 23 d were included in the analysis to explain the corrosion mechanism. At low frequencies (f < 1 Hz), the impedance of the CrMnFeCoNi sample increased during the first 2 d of immersion, reaching ~2 kΩ cm2. However, the phase shift minimum at medium frequencies (10 Hz < f < 103 Hz), decreased from −76° at 0 d to −73° at 2 d, indicating a poor capacitor-like behavior and reduced protectiveness of the passive film. During prolonged immersion (7-20 d), the impedance stabilized at ~300 Ω cm2 at 10 mHz, before dropping further to 25 Ω cm2 after 23 d, as shown in Fig. 4c. These values are up to four orders of magnitude lower than those observed for the CrCoNi sample, indicating lower corrosion resistance and higher reactivity of CrMnFeCoNi in 1 M H2SO4. The phase shift minimum varies with frequency, showing the most significant changes within 10 < f < 103 Hz (Fig. 2b, d). Over time, the phase shift increases at a given frequency, with the phase minimum reaching −50° after 21 d and −43° after 28 d. This progression indicates that the passive film formed on CrMnFeCoNi lacks capacitor-like behavior and provides only transient, limited protection against corrosion, in stark contrast to the stable passivation observed for CrCoNi in 1 M H2SO4.

The decreasing protective properties of the passive film on CrMnFeCoNi are further confirmed by the Nyquist plots shown in Fig. 4e. At initial immersion (0 d), the Nyquist plot displays a depressed capacitive semicircle followed by a clear inductive loop at low frequencies and suggests that the native passive film formed on CrMnFeCoNi rapidly becomes unstable and starts to degrade. Between 2 d and 14 d of immersion, the Nyquist plots change, displaying a straight line after the semicircle. This shift reflects mass transport limitations, where the corrosion rate depends on the transport of ions or species to and from the surface rather than on the reaction itself. This behavior is attributed to active surface dissolution and the formation of a dense, diffusion-limiting layer. Interestingly, after 21 d of immersion, the inductive loop reappears, once again pointing to interfacial instabilities dominating the corrosion mechanism. Such behavior indicates that the passive layer continues to deteriorate, and the surface undergoes dynamic changes, with the intermittent adsorption of corrosion intermediates influencing the charge transfer processes. This dynamic behavior complicates mechanistic interpretations and highlights that CrMnFeCoNi undergoes active corrosion, resulting in continuous interface changes during EIS measurements. While fitting the CrCoNi EIS data was straightforward, describing the corrosion mechanism for CrMnFeCoNi proved more challenging due to its greater complexity and variability. The same EEC (Fig. 1) was applied, but when the inductive loop was present, αdl was adapted to −1 to account for inductance45. However, reasonable χ2 values (of the order of 10−3) were achieved after 21 d of immersion.

For the CrMnFeCoNi sample, EOCP varies over the 28 d of the experiment as shown in Fig. 4f. During the first day of immersion, EOCP increased from -350 mV to -310 mV, suggesting the formation of a protective film. This observation correlates with the noted increase in impedance at 10 mHz after 2 d in Fig. 4a, c. However, EOCP of CrMnFeCoNi decreased to −370 mV within the first 7 d of immersion, indicating that the initially formed passive layer cannot provide adequate corrosion protection. From 7 to 21 d, EOCP decreased at a slower rate to −380 mV and reached a steady-state value of −388 mV by the end of the 28-d period. A continuous decrease in EOCP over time is characteristic for a system that does not reach steady state, suggesting that the surface is actively corroding within the 28 d of the experiment. The results of the EOCP analysis are in good agreement with the EIS findings presented in Fig. 4a–d. For CrMnFeCoNi, EOCP was 500–700 mV more negative than that of CrCoNi (Fig. 2f), which can be attributed to its higher susceptibility to corrosion. In contrast to CrCoNi, the rapid deterioration of CrMnFeCoNi highlights the critical role of alloy composition in long-term corrosion resistance and emphasizes the need for careful material selection when designing for extreme service conditions.

The CrMnFeCoNi alloy dissolved an average of 77 mmol L−1 of ions over the immersion period of 28 d, compared to only 0.002 mmol L−1 for CrCoNi. The relative amount of metal ions released from CrMnFeCoNi in 1 M H2SO4 was determined from the ion concentration in the corrosion medium after 28 d, as measured by ICP-MS, and is summarized in the bar graph in Fig. 5. The dissolution was nearly stoichiometric, with a distribution closely matching the bulk composition of CrMnFeCoNi, which aligns well with the XPS depth profiles discussed below.

Chemical composition of the MPEA surfaces

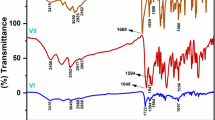

The ion concentrations in the solution suggest different surface compositions of the oxide layers formed on the CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi surfaces. The composition of each surface layer of the CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi samples was studied by XPS after preparation and after immersion in 1 M H2SO4 for 28 d. In our previous study involving CrCoNi samples after cyclic potentiodynamic polarization, the higher surface concentration of metallic species allowed us to successfully apply 3p XPS analysis to distinguish metallic and oxidized species36. However, in the present long-term immersion study, the significantly lower metallic signal rendered the 3p region unsuitable for reliable evaluation. Although the 3p region typically offers less spectral overlap and better resolution in complex alloys, it was not applicable in this case. Therefore, the 2p core levels were used to evaluate the oxidation states, despite their known spectral complexity and limitations46. Figure 6 compares the high-resolution 2p spectra of Cr, Co, and Ni after 28 d of the corrosion experiment with the spectra of the as-prepared CrCoNi alloy. Cr0, Co0, and Ni0 are the main components of a freshly polished CrCoNi surface47. In the freshly prepared sample, the deconvolution of the 2p3/2 lines gave the following lines: Cr(0) at Eb = 573.8 eV (full width at half maximum, FWHM = 0.93 eV), Co(0) at Eb = 778.2 eV (FWHM = 0.72 eV), and Ni(0) at Eb = 852.8 (FWHM = 0.89 eV) (Fig. 6 upper panel). Note that the Cr 2p3/2 line has a second component around 576 eV (broad line) which points on the existence of oxide species48. Similarly, the Co 2p3/2 line exhibits a weak peak around 780 eV which may be associated with oxide species. The Ni 2p3/2 peak observed at binding energies around 860 to 863 eV corresponds to a satellite feature, characteristic of Ni²⁺ species49,50,51.

High-resolution 2p XP spectra of Cr, Co, and Ni in a CrCoNi alloy in the as-prepared state (top row) and after immersion in 1 M H2SO4 for 28 d (bottom row). The gray bar indicates the 2p3/2 binding energy Eb range of the metallic state, the blue marks the Eb range of metal oxides, and the yellow bar the region of metal sulfates.

After 28 d of immersion, the XP spectra of the three metallic components changed significantly. The signals from Cr0, Co0, and Ni0 decreased in intensity. The largest decrease was observed for the Cr 2p3/2 signal at Eb = 574.4 eV. The 2p lines are shifted to higher binding energies indicating that all metals are involved in oxidation reactions. Cr gives a strong 2p3/2 line at Eb = 578.7 eV which is associated with Cr2(SO4)3 species48,52,53. Co and Ni give two 2p3/2 lines which are associated with oxidized metals. The two Co 2p3/2 lines appear at Eb = 782.6 and Eb = 786.8 eV which are ascribed to oxide and sulfate species, separately47,54. The Ni 2p3/2 line appears at Eb = 857.4 and can be assigned to sulfide as well as oxide species54.

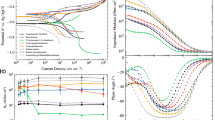

The O 1 s and S 2p high-resolution XP spectra of the as-prepared CrCoNi surface are presented in Fig. 7a. The O 1 s spectra have three components at binding energies Eb = 529.9 eV, 530.9 eV, and 533.5 eV, reflecting the composition of oxidized metals. The peaks at Eb = 529.9 eV and 530.9 eV are assigned to metal oxides and sulfates54,55. The third O 1 s peak at Eb = 533.5 eV is due to water present on the CrCoNi alloy surface. Similar to CrCoNi, the O 1 s XP spectrum of a freshly polished CrMnFeCoNi sample indicates the presence of metal oxides and water bound on the alloy surface46,56 (Fig. 7b).

a High-resolution O 1 s and S 2p XP spectra of the CrCoNi and b CrMnFeCoNi alloys: as-prepared (top row) and after 7 d of immersion in 1 M H2SO4 solution (middle row) and 28 d of immersion (bottom row). The same sample was studied after reimmersion in the corrosion medium. The assignment of the deconvoluted XP lines is given at the top of the figure. Red arrows indicate the direction of peak shifts.

No S-species were detected on the freshly polished sample (Fig. 7). The peaks found after 7 d of immersion of the CrCoNi alloy in 1 M H2SO4 at Eb = 162.3 eV and 168.5 eV were assigned to S2− and SO32− species, respectively52,53,57. Such composition of the corrosion product layer was already observed in our previous study on CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi after anodic polarization in 0.1 M H₂SO₄36. This result indicates the progress of redox reactions in which the metals are oxidized, and sulfate ions are reduced, as described already by Ouarga et al.54. However, after 28 d of the corrosion experiment, new lines Cr 2p3/2 at Eb = 578.6 eV, Co 2p3/2 at Eb = 782.9 eV, and Ni 2p3/2 at Eb = 857.2 eV were found in the spectra (yellow marked regions in Fig. 6). These 2p lines appeared together with a strong S 2p3/2 line at Eb = 169.5 eV and O 1 s at Eb = 532.6 eV (Fig. 7a), indicating that sulfates of the corresponding metal ions are present on the CrCoNi surface.

In the as-prepared CrMnFeCoNi sample, the atoms are present in the metallic state (M0) and in their oxides (Mox), as shown in Fig. 8 (upper panel). The deconvolution results gave the following 2p3/2 lines for the metals: Cr(0) at Eb = 573.8 eV (full width at half maximum, FWHM = 0.90 eV), Mn(0) Eb = 638.6 eV (FHWM = 0.79 eV), Fe(0) at Eb = 706.8 eV (FWHM = 0.70 eV), Co(0) at Eb = 778.2 eV (FWHM = 0.79 eV) and Ni(0) at Eb = 852.8 (FWHM = 0.89 eV) (Fig. 8 upper panel). In this sample, the 2p3/2 lines, at Eb higher than respective M0 signals, exhibit a broad line which is assigned to oxidized metallic species46,58.

High-resolution 2p XP spectra of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni of a CrMnFeCoNi alloy in the as-prepared state (top row), after immersion of 7 d (middle row) and of 28 d (bottom row) in 1 M H2SO4. The gray bar indicates the Eb region of the metallic state, the blue bar the region of metal oxides, and yellow bar the region of metal sulfates.

During the first 7 d of corrosion in 1 M H2SO4, the overall intensity of the metallic 2p lines decreases (Fig. 8 middle panel). Moreover, the intensity ratio of the Mn+/M0 signals increases due to the formation of the oxide/sulfite/sulfate film (middle row of Figs. 8, 7b). Figure 8 (middle panel) shows that broad Cr 2p3/2 (Eb = 576 eV) and Mn 2p3/2 line (Eb = 641 eV) lines originating from the oxidized metals are dominant and stronger in intensity than the metal lines. The Fe 2p3/2 line (Eb = 711 eV) an Co 2p3/2 line (Eb = 780 eV) are assigned to the oxidized species, but their intensities are lower than those of the metallic forms. Furthermore, oxides (O 1 s) and sulfites and sulfides (S 2p) (Fig. 7b) are detected after 7 d of the corrosion experiment. Thus, the metal ions are involved in the formation of different kinds of compounds. The metal oxides (e.g., CrOx, CoOx, or FeOx) give complex, broad, and multicomponent 2p3/2 signals. Because the corroded surface contains a mixture of oxides, sulfites, and sulfides, the XPS peaks can only be deconvoluted into one or two broad components. Therefore, the precise identification of individual compounds is not possible.

After 28 d of immersion in 1 M H2SO4, the signals of the metallic state of all elements disappear completely, and instead, oxide and sulfate species are detected at higher binding energies. The O 1 s and S 2p high-resolution spectra of the CrMnFeCoNi alloy are similar to those from the CrCoNi sample (Fig. 7). Briefly, the initial oxide-hydroxide layer is enriched with sulfides and sulfites after 7 d of corrosion in 1 M H2SO4. Similar to CrCoNi, prolonged immersion results in the conversion of the sulfide/sulfite species to a sulfate-containing surface film. The corrosion layer is a multicomponent mixture of oxide and sulfate species of all five metal cations present in the alloy. After 7 d of the corrosion experiment, redox reactions yielding insoluble metal sulfites and sulfides accumulate on the surface of both alloys. Within the next three weeks, a sulfate-rich layer deposits on the surface.

To investigate the surface layers composition, sputtering experiments (Ar ions with E = 4000 eV) were conducted. Quantification of the 2p lines of the metals is a complex task that potentially bears errors. First of all, due to the presence of different compounds such as oxides, sulfides, and sulfates on the alloy surfaces, the deconvolution of the 2p metal lines increases in complexity. In addition, the Fe 2p line is overlapped with the Co LMM (∼713 eV) and Ni LMM (∼712 eV) line47. The low binding energy side of the Co 2p line is overlapped with a Ni LMM (∼778 eV), while the Mn 2p line with Auger NiLMM line. In the CrMnFeCoNi sample, the Ni 2p is overlapped with the Mn LMM (∼852 eV) Auger line. Figure 9 shows the results of the quantitative analysis of the surface composition of the CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi as the function of sputtering time. Note that the content of Fe is higher than that of other metals and may indicate a systematic error in the quantitative analysis due to the overlap of the Fe 2p3/2 lines with Co LMM and Ni LMM Auger lines. Due to the fact that the 3p and 3 s lines of the metals present in the alloys in the corroded sample have extremally low intensities (not distinguishable from the background), the quantitative analysis is based on the deconvolution results of the 2p lines of the metals.

XPS depth profiles demonstrating the elemental composition of CrCoNi (right) and CrMnFeCoNi (left) corroded for 28 d in 1 M H2SO4 after different times of Ar ions sputtering. The error bars correspond to uncertainty in the content of a given element in the sample obtained in three independent deconvolutions. The larger error of 15% was obtained for Fe. The uncertainty of the determination of the content of other elements was 6-10%.

The surface layer was removed from the CrCoNi alloy within 14 min of sputtering with Ar ions with energy of 4 keV, while to remove the surface layer of the CrMnFeCoNi alloy, 45 min were needed. Even though both layers develop in a similar way and are composed of a rather thick sulfate layer followed by a mixed sulfite—sulfides, and oxide layers they differ in thickness. Both samples contain organic contaminations (C 1s). Carbon constitutes approximately 18% on the CrCoNi and 26% on the CrMnFeCoNi surface. At the beginning of the sputtering experiments, the surface of CrCoNi contains a higher content of Cr, suggesting that oxidation products of this metal accumulate preferentially on the alloys surface. This result is in agreement with the ICP-MS data as they revealed a lower Cr content in the electrolyte after corrosion for CrCoNi (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the content of O (52-54%) is originally approximately 4 times larger than S (13-15%), indicating that the outer corrosion layer contains predominantly sulfates. With increasing sputtering time, the [O]:[S] ratio equals 4.2:1 for CrCoNi at t = 11 min while 5.1:1 for CrMnFeCoNi at t = 14 min. The increased content of O indicates that less sulfate is incorporated at the deeper located corrosion layers. After further sputtering of 3 min the signals from S on the CrCoNi surface are removed, indicating that the sulfate species are predominantly incorporated in an outer layer of the corrosion layer, while an oxide layer is present close to the alloy surface. The oxygen content was approximately 11%, and the three metallic components showed similar concentrations (Cr: 28%, Co: 32%, Ni: 26%), which closely matches the composition of the as-prepared CrCoNi sample (Cr: 29%, Co: 32%, Ni: 28%). XPS measurements on the as-prepared samples were conducted after sputtering the surface for 30 s.

On the CrMnFeCoNi alloy, approximately 40 min of sputtering were required to remove the signals of S, indicating that the mixed sulfate-oxide layer is much thicker on the CrCoNi surface. Fe and Co were detected at around 21% and 20%, respectively, while Mn, Cr, and Ni were present at approximately 19%, 15%, and 15%, aligning well with the nominal composition of the as-prepared CrMnFeCoNi alloy (Fe: 21%, Co: 21%, Mn: 18%, Cr: 15%, Ni: 16%). The high content of Fe may be falsified by the complexity of deconvolution and overlap with the Auger lines. The large content of Co and Fe on the CrMnFeCoNi surface also suggests that metal ions of both elements accumulate preferentially on the oxide surface. The study by Wu et al.26 provides additional evidence for this, showing that Co interacts with other elements in the passive film of a non-equiatomic FeNiCoCr high-entropy alloy, leading to the formation of complex oxides such as Co(Fe, Cr)2O4.

Most likely a water-insoluble, mixed Cr(II/III) and Co(II) sulfide-sulfite layer grows on the oxide/atomic metal surface of the CrCoNi alloy and is converted to a sulfate layer during prolonged corrosion. XPS studies by Keller and Strehblow52 on Fe20Cr and Fe15Cr alloys support these findings. Their research explored the pre-passive, passive, and transpassive potential ranges by anodic polarization in 0.5 M H2SO4, showing that the passive layers predominantly consist of Cr(III) compounds, such as Cr(III)-hydroxide and Cr(III)-sulfate in the pre-passive state, transitioning to Cr(III)-oxides in the passive state. They also observed the formation of a bilayer structure, with an outer sulfate/hydroxide layer and an inner oxide layer. The binding energy of Cr2(SO4)3 at Eb = 578.6 eV in their study aligns closely with our findings.

The increased Cr concentration leads to the development of a more compact and thicker Cr-rich passive film, significantly enhancing the alloy’s ability to resist corrosion. Studies, such as those conducted by Wan et al.59, demonstrate that as the Cr content increases, the corrosion resistance improves, primarily due to the formation of this stable passive layer. The ICP-MS experiments indicate a preferential dissolution of Ni and Co and a lower Cr concentration in the electrolyte, which supports the Cr enrichment in the passive film.

Morphology of the corroded sample surfaces

The morphology of the corroded sample surfaces was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in the secondary electron (SE) mode. The SEM images illustrate the surface topography of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi samples before and after immersion tests in a 1 M H2SO4 electrolyte solution for 28 d (Fig. 10). The polished CrCoNi surface (Fig. 10a) exhibits a smooth topography with Cr oxide inclusions, which remain visible after 28 d of immersion (Fig. 10b), indicating the formation of a compact and stable passive film. The examinations indicate that a thin, passive layer has formed on the CrCoNi alloy, containing mainly Cr, Co, Ni, O, and S species, as demonstrated by the corresponding elemental assignments by electron dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy in Fig. 10c.

a SEM image of the polished CrCoNi surface before the long-term immersion. b SEM image of the CrCoNi surface after 28 d of immersion in 1 M H2SO4 with intact inclusion (yellow square) and residual electrolyte (orange arrow). c EDX maps from the area shown in the frame of (b), displaying Cr, Co, Ni, O, and S.

Similarly to CrCoNi, the SEM images in Fig. 11a reveal an initial smooth topography of the CrMnFeCoNi sample with Cr oxide inclusions. However, after 28 d of immersion, the surface of CrMnFeCoNi exhibits significant changes, including the formation of a rough, porous, and loosely adherent layer of corrosion products, as shown in Fig. 11b. These observations indicate that the corrosion product layer formed on CrMnFeCoNi is significantly less stable than that on CrCoNi, with higher porosity and reduced mechanical integrity.

Additionally, the EDX mapping (Fig. 11c) reveals the presence of all five metals (Cr, Co, Ni, Mn, Fe) along with O and S species on the surfaces. This observation aligns with the XPS results, which indicate the formation of a mixed oxide/sulfate layer containing significant amounts of Fe and Mn. Unlike the behavior observed during short-term electrochemical polarization tests, the entire long-term study revealed distinct corrosion mechanisms for both alloys. In contrast to our previous findings, where CrCoNi exhibited intergranular corrosion after anodic polarization in 0.1 M H2SO436, no intergranular corrosion was observed after 28 d in the more concentrated 1 M H2SO4 solution, further indicating the stability of the Cr-rich passive layer. For CrMnFeCoNi, pitting corrosion was previously identified after anodic polarization in 0.1 M H2SO436, long-term immersion in 1 M H2SO4 resulted in the formation of a fragile and porous corrosion layer, reflecting significant material degradation. Although CrMnFeCoNi initially demonstrated corrosion behavior comparable to AISI 304 SS in 0.1 M H2SO4, it shows markedly reduced resistance under the harsher conditions of 1 M H₂SO₄. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating long-term immersion studies for a more comprehensive assessment of material durability, particularly in aggressive environments.

Discussion

This study highlights significant differences in the long-term corrosion behavior of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi alloys in 1 M H2SO4. The consistently high impedance and positive EOCP values shown in Fig. 2 confirm the exceptional stability of the CrCoNi passive film over extended exposure times, positioning CrCoNi as a promising candidate for applications in highly aggressive environments. The low content of Cr ions in the solution, as revealed by ICP-MS measurements in Fig. 3, suggests that Cr is enriched in the passivation layer and most likely crucial for the formation of a stable and protective passive layer. The pronounced dissolution of Ni observed here is consistent with previous studies on stainless steels and CrMnFeCoNi alloys, where Ni was found to preferentially dissolve and to be enriched in its metallic form beneath the surface oxide layer, while Cr accumulated in the passive film36,41,60. This behavior contrasts with CrMnFeCoNi, which exhibited a continuous decrease in open circuit potential (Fig. 4f), lower impedance values (Fig. 4e), and higher rates of metal ion dissolution, indicative of a less protective mixed oxide layer dominated by Fe and Mn species.

Notably, long-term immersion tests revealed key differences from polarization corrosion tests. The detailed SEM and EDX analyses provide a comprehensive understanding of the morphological changes and lateral elemental distribution on the alloy surfaces, correlating with their respective corrosion behaviors. While CrCoNi showed intergranular corrosion during polarization in our previous study36, this was absent in immersion tests, where a stable Cr-rich passive film formed, explaining its superior corrosion resistance in acidic environments (Fig. 10). In contrast, CrMnFeCoNi, which exhibited pitting corrosion in polarization tests, developed a loose, porous surface layer during immersion, indicating greater but less localized material degradation (Fig. 11). The inductive feature displayed in Fig. 4e is typically associated with interfacial instabilities or delayed interfacial processes, such as the adsorption and desorption of intermediate species during corrosion. As reported by Keddam et al.61, inductive loops at low frequencies can arise from the progressive weakening of the protective surface layer, leading to a transient relaxation of active surface sites. Ma et al.62 further showed that such behavior is linked to the accumulation and delayed release of soluble species at the metal/electrolyte interface, contributing to transient changes in double-layer capacitance and surface coverage.

The observed transformation of sulfide/sulfite species into a sulfate-containing surface film after prolonged immersion provides new insights into the dynamic surface chemistry of MPEAs under harsh acidic conditions (Fig. 7). This corrosion mechanism has been previously reported for Fe- and Ni-based alloys54 but, to our knowledge, has not been observed in multi-principal element alloys (MPEAs) until now. The formation of NiSO4 is more likely in concentrated H2SO4 solutions, as higher acid concentrations suppress oxide formation in favor of NiSO4. When the H2SO4 concentration exceeds 2.5 M, Ni dissolves rapidly, inhibiting oxide formation and leading primarily to the production of NiSO4. Surface passivation occurs because NiSO4 has a low solubility, forming a compact, adherent film with high corrosion resistance54,63,64. Kish et al.65 detailed a corrosion mechanism for Ni in hot, highly concentrated sulfuric acid (93 wt%), where rapid dissolution of Ni results in the release of H2S, facilitating the formation and growth of NiS. NiS then dissolves, leading to the precipitation of a stable, insoluble NiSO4 film on the surface. Sulfide species are present after 7 d of corrosion but dissipate after 28 d, suggesting a gradual transformation into a sulfate layer over time. This transformation is not observable in short term experiments and electrochemically induced corrosion of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi36, highlighting the importance of long-term surface analysis for understanding passivation and degradation pathways that remain undetected in short-term electrochemical tests.

The detailed structure and chemical composition of corrosion layers forming on MPEAs is difficult to analyze experimentally, particularly due to their layered nature and the involvement of multiple redox active elements. Oxide layer formation can be modeled using the Point Defect Model (PDM), originally developed by Macdonald et al.66,67 to support experimental analysis of passive films on conventional alloys. Chen et al.68 were the first to use modeling to better understand the growth of oxide layers on MPEAs. In their study, they applied the PDM to simulate oxide layer formation on CrMnFeCoNi in acidic media and experimentally confirmed the model predictions using XPS, EIS, time-of-fight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). They proposed a two-layer structure consisting of a compact, Cr rich inner region and an outer region enriched in Fe, Co, and Mn, which contains a higher density of point defects such as oxygen vacancies and cation interstitials. These defects govern ionic transport and film permeability and thus directly affect the protective quality of the passive film. However, their approach was limited to oxide formation under polarization conditions and does not reflect the time-dependent changes observed during long-term immersion. Moreover, the model does not account for the transformation of sulfur-containing species such as sulfides, sulfites, and sulfates. These gaps highlight the need for future modeling approaches that incorporate both sulfur chemistry and the long-term effects of realistic service environments in order to better understand passive film formation on MPEAs.

While the chosen corrosion conditions involving static immersion in 1 M H2SO4 at room temperature allowed for controlled mechanistic investigation, they represent an idealized laboratory scenario. To fully assess material performance, the behavior of these alloys under real-world service conditions, such as dynamic flow, temperature fluctuations, and the presence of oxygen or chloride species, needs to be investigated in future studies.

In summary, this study advances the fundamental understanding of passive film evolution and degradation mechanisms in MPEAs, demonstrating the necessity of long-term evaluations for reliable performance predictions. The superior performance of CrCoNi highlights its potential for corrosion-critical applications, while the inferior stability of CrMnFeCoNi underscores the influence of alloying elements on long-term durability. Future investigations could further explore the relationship between alloy composition, corrosion morphology, and complex environmental conditions to support the development of more durable materials.

Methods

Sample preparation

The Laplanche group at Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany, produced the vacuum-melted ingots of CrMnFeCoNi and CrCoNi according to published procedures39. The CrMnFeCoNi and CrCoNi alloys underwent homogenization and recrystallization for 1 h at temperatures of 1020 °C and 1060 °C, respectively. Both alloys demonstrated a single-phase face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure with an average grain size of 50 µm69. Table 1 presents the chemical compositions of the alloys as determined by X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRFA)69.

For subsequent investigations, the alloy samples were initially wet ground using SiC paper with grits ranging from 600 to 4000 (ATM GmbH, Germany). They were then polished sequentially with 3 µm and 1 µm diamond pastes on appropriate polishing cloths (ATM GmbH, Germany). Following the final polishing step, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic P) with deionized water (0.055 µS cm−1, Evoqua, USA) and then with acetone (ChemSolute, min. 99.5%, Germany) for 5 min at 80 kHz to remove any surface residues. The specimens were then dried using an oil-free compressed air stream.

Electrochemical studies

The electrochemical experiments were carried out in a 20 mL 1 M H2SO4 (AppliChem, Germany) electrolyte prepared with deionized water. Measurements of EOCP and EIS were conducted at room temperature with a Gamry Reference 600+ potentiostat (C3 Prozess- und Analysentechnik GmbH, Haar b. München, Germany) and the Gamry Framework data acquisition software (version 7.8.2) in a three-electrode configuration. The alloy sample served as the working electrode (WE), with an exposed surface area of 0.57 cm². A graphite rod was used as the auxiliary electrode (AUX), and an Ag/AgCl electrode (3 M NaCl, ALS Co., Tokyo, Japan) functioned as the reference electrode (RE). The experimental sequence included EOCP measurements for 1800 s, followed by EIS within a frequency range of 100000 Hz to 0.01 Hz. The EIS measurements were conducted using an AC voltage amplitude of 10 mV. The sample surfaces were measured twice a day over a period of 28 d. Data analysis and fitting of EEC in Fig. 1 for the EIS spectra were performed using Gamry EChem Analyst (version 7.8.2).

In thet EEC model (Fig. 1) the resistor Rs represents the resistance of the electrolyte solution which is in series with a parallel combination of constant phase element CPEf and a resistor Rf70. This combination is incorporated to address the heterogeneous and potentially porous nature of the passive film. The constant phase element CPEdl and resistor Rct account for the electrical double layer and the charge transfer occurring at its interface with the electrolyte.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

XPS measurements were conducted on the CrMnFeCoNi and CrCoNi samples using an ESCALAB 250 Xi spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, East Grinstead, UK) with a monochromatic Al Kα radiation (hv = 1486.6 eV). Charge compensation was applied for samples corroded for longer than 14 d. Argon cluster ion sputtering (Ebeam = 2 keV) was applied for 60 s to remove organic surface contamination before each measurement. High-resolution Cr 2p, Mn 2p, Fe 2p, Co 2p, Ni 2p, S 2p, O 1 s XP spectra were acquired with pass energy Epass = 10 eV, step size ΔE = 0.1 eV, and dwell time τ = 50 ms. Ten scans were accumulated for Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, S lines, and 8 scans for C and O. The survey spectra were recorded using Epass = 100 eV, ΔE = 1.0 eV, and τ = 50 ms (1 scan). The binding energy scale was referenced to the C 1 s photoelectron line at Eb = 285.0 eV. Alloy samples corroded for 28 d were sputtered with Ar+ ions with an energy of 4 eV.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

ICP-MS was utilized to monitor and determine the concentrations of dissolved metal ions in the corrosion medium after a 28-d immersion period. The analysis was performed using an iCAP Q ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) with an autosampler (ESI SC 4 DX Fast, Elemental Scientific, Omaha, USA) and the QtegraTM software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, version 2.10.4345.64). The MS system was tuned daily according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. A 10 µg L−1 rhodium solution (prepared from 1000 mg L−1 Certipur, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was mixed on-line into the samples via the autosampler at a ratio of approximately 1:10 for drift corrections. External calibration was done using a multi-element standard (ICP-multi-element standard IV, Certipur, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Preparation of the standards and sample dilution involved Type I reagent-grade water (18.2 MΩ cm) from a Milli-Q-System (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and HNO3 (65% p.A., Chemsolute, Th Geyer, Germany, double sub-boiled).

Scanning electron microscopy/electron diffractive X-ray spectroscopy

A VEGA3 TESCAN system equipped with an EDX detector operated at 20 kV was used to record all SEM images and EDX data.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings will be made available on request.

References

Han, L. L. et al. Multifunctional high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 846–865 (2024).

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Yeh, J. W. Alloy design strategies and future trends in high-entropy alloys. JOM 65, 1759–1771 (2013).

Kosec, T. & Milosev, I. Comparison of a ternary Cu-18Ni-20Zn alloy and binary Cu-based alloys in alkaline solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 104, 44–49 (2007).

Gao, L. B. et al. Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of CoCrFeNiAl0.3 high entropy alloy (HEA) films. Coatings 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings7100156 (2017).

Huang, S. et al. Twinning in metastable high-entropy alloys. Nat. Commun. 9, 2381 (2018).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016).

Yang, T. et al. Multicomponent intermetallic nanoparticles and superb mechanical behaviors of complex alloys. Science 362, 933–937 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nanoscale origins of the damage tolerance of the high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi. Nat. Commun. 6, 10143 (2015).

Zhao, R.-F. et al. Corrosion behavior of CoxCrCuFeMnNi high-entropy alloys prepared by hot pressing sintered in 3.5% NaCl solution. Results Phys. 15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102667 (2019).

Zhang, B. L., Zhang, Y. & Guo, S. M. A thermodynamic study of corrosion behaviors for CoCrFeNi-based high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 14729–14738 (2018).

Wei, L., Liu, Y., Li, Q. & Cheng, Y. F. Effect of roughness on general corrosion and pitting of (FeCoCrNi)0.89(WC)0.11 high-entropy alloy composite in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 146, 44–57 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Tribocorrosion behavior of high-entropy alloys FeCrNiCoM (M = Al, Mo) in artificial seawater. Corros. Sci. 218 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111165 (2023).

Sun, Y., Lan, A., Wang, Z., Zhang, M. & Qiao, J. Effect of sulfuric acid concentration on corrosion behavior of Al0.1CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 161 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110397 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Homogenization of Al CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys with improved corrosion resistance. Corros. Sci. 133, 120–131 (2018).

Muangtong, P., Rodchanarowan, A., Chaysuwan, D., Chanlek, N. & Goodall, R. The corrosion behaviour of CoCrFeNi-x (x=Cu, Al, Sn) high entropy alloy systems in chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 172 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108740 (2020).

Gaber, G. A., Abolkassem, S. A., Elkady, O. A., Tash, M. & Mohamed, L. Z. ANOVA and DOE of comparative studies of Cu/Mn effect on corrosion features of CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy immersed in different acidic media. Chem. Pap. 76, 1675–1690 (2022).

Ye, Q. F. et al. Microstructure and corrosion properties of CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloy coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 396, 1420–1426 (2017).

Xing, B. W. et al. Influence of microstructure evolution on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of (CoCrFeNi)TiAl high entropy alloy coatings. J. Therm. Spray. Technol. 31, 1375–1385 (2022).

Popescu, A. M. J. et al. Influence of heat treatment on the corrosion behavior of electrodeposited CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy thin films. Coatings 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12081108 (2022).

Qiu, Y., Gibson, M. A., Fraser, H. L. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion characteristics of high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 1235–1243 (2015).

Qiu, Y., Thomas, S., Gibson, M. A., Fraser, H. L. & Birbilis, N. Corrosion of high entropy alloys. npj Mater. Degrad. 1, 15 (2017).

Moon, J. T., Schindelholz, E. J., Melia, M. A., Kustas, A. B. & Chidambaram, D. Corrosion of additively manufactured CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy in molten NaNO3-KNO3. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 081509 (2020).

Rodriguez, A., Tylczak, J. H. & Ziomek-Moroz, M. Corrosion behavior of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloys (HEAs) under acidic aqueous conditions. ECS Trans. 77, 741–752 (2017).

Bogdanov, R. I. et al. Corrosion and electrochemical behavior of CoСrFeNiMo high-entropy alloy in acidic oxidizing and neutral chloride solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 295, 127123 (2023).

Wu, P., Gan, K., Yan, D., Fu, Z. & Li, Z. A non-equiatomic FeNiCoCr high-entropy alloy with excellent anti-corrosion performance and strength-ductility synergy. Corros. Sci. 183, 109341 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Effects of Mn on the electrochemical corrosion and passivation behavior of CoFeNiMnCr high-entropy alloy system in H2SO4 solution. J. Alloy. Compd. 819, 152943 (2020).

Hsu, K.-M., Chen, S.-H. & Lin, C.-S. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of FeCrNiCoMnx (x = 1.0, 0.6, 0.3, 0) high entropy alloys in 0.5 M H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 190, 109694 (2021).

Cwalina, K. L. et al. In operando analysis of passive film growth on Ni-Cr and Ni-Cr-Mo alloys in chloride solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, C3241–C3253 (2019).

Hamm, D., Ogle, K., Olsson, C. O. A., Weber, S. & Landolt, D. Passivation of Fe-Cr alloys studied with ICP-AES and EQCM. Corros. Sci. 44, 1443–1456 (2002).

Li, T. S. et al. Localized corrosion behavior of a single-phase non-equimolar high entropy alloy. Electrochim. Acta 306, 71–84 (2019).

Quiambao, K. F. et al. Passivation of a corrosion resistant high entropy alloy in non-oxidizing sulfate solutions. Acta Mater. 164, 362–376 (2019).

Chen, Y. Y., Hong, U. T., Shih, H. C., Yeh, J. W. & Duval, T. Electrochemical kinetics of the high entropy alloys in aqueous environments—a comparison with type 304 stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 47, 2679–2699 (2005).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Enhanced passivity of Cr-Fe-Co-Ni-Mo multi-component single-phase face-centred cubic alloys: design, production and corrosion behaviour. Corros. Sci. 200, 110233 (2022).

Czerski, J. et al. Corrosion and passivation of AlCrFe2Ni2Mox high-entropy alloys in sulphuric acid. Corros. Sci. 229, 111855 (2024).

Wetzel, A. et al. The comparison of the corrosion behavior of the CrCoNi medium entropy alloy and CrMnFeCoNi high entropy alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 601, 154171 (2022).

Shi, Y. Z., Yang, B. & Liaw, P. K. Corrosion-resistant high-entropy alloys: a review. Metals 7, 7020043 (2017).

Scully, J. R. et al. Controlling the corrosion resistance of multi-principal element alloys. Scr. Mater. 188, 96–101 (2020).

Luo, H., Li, Z. M., Mingers, A. M. & Raabe, D. Corrosion behavior of an equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy compared with 304 stainless steel in sulfuric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 134, 131–139 (2018).

Jayaraj, J., Thinaharan, C., Ningshen, S., Mallika, C. & Kamachi Mudali, U. Corrosion behavior and surface film characterization of TaNbHfZrTi high entropy alloy in aggressive nitric acid medium. Intermetallics 89, 123–132 (2017).

Wang, L. T. et al. Study of the surface oxides and corrosion behaviour of an equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy by XPS and ToF-SIMS. Corros. Sci. 167, 108507 (2020).

Qiu, Y. et al. Microstructural evolution, electrochemical and corrosion properties of Al CoCrFeNiTi high entropy alloys. Mater. Des. 170, 107698 (2019).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Origin of enhanced passivity of Cr-Fe-Co-Ni-Mo multi-principal element alloy surfaces. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 13 (2023).

Li, C. K., Peng, Z. Q. & Huang, J. Impedance response of electrochemical interfaces: part IV-lowfrequency inductive loop for a single-electron reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 16367–16373 (2023).

Yen, C. C. et al. Corrosion mechanism of annealed equiatomic AlCoCrFeNi tri-phase high-entropy alloy in 0.5 M H2SO4 aerated aqueous solution. Corros. Sci. 157, 462–471 (2019).

Biesinger, M. C. et al. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 2717–2730 (2011).

Moulder, J. F., Stickle, W. F., Sobol, P. E. & Bomben, K. D. Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. 1 edn, (Perkin-Elmer-Corporation, 1992).

Payne, B. P., Biesinger, M. C. & McIntyre, N. S. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of reactions on chromium metal and chromium oxide surfaces. J. Electron. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 184, 29–37 (2011).

Lei, Y., Wang, Y. Y., Yang, W., Yuan, H. Y. & Xiao, D. Self-assembled hollow urchin-like NiCo2O4 microspheres for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors. Rsc Adv. 5, 7575–7583 (2015).

Pang, M. J. et al. Mesoporous NiCo2O4 nanospheres with a high specific surface area as electrode materials for high-performance supercapacitors. Rsc Adv. 6, 67839–67848 (2016).

Grosvenor, A. P., Biesinger, M. C., Smart, R. S. & McIntyre, N. S. New interpretations of XPS spectra of nickel metal and oxides. Surf. Sci. 600, 1771–1779 (2006).

Keller, P. & Strehblow, H. H. XPS investigations of electrochemically formed passive layers on Fe/Cr-alloys in 0.5 M H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 46, 1939–1952 (2004).

Park, S. A., Lee, S. H. & Kim, J. G. Effect of chromium on the corrosion behavior of low alloy steel in sulfuric acid. Met. Mater. Int. 18, 975–987 (2012).

Ouarga, A. et al. Corrosion of iron and nickel based alloys in sulphuric acid: Challenges and prevention strategies. J. Mater. Res Technol. 26, 5105–5125 (2023).

Biesinger, M. C., Brown, C., Mycroft, J. R., Davidson, R. D. & McIntyre, N. S. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of chromium compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 36, 1550–1563 (2004).

Wurzler, N., Sobol, O., Altmann, K., Radnik, J. & Ozcan, O. Preconditioning of AISI 304 stainless steel surfaces in the presence of flavins-Part I: effect on surface chemistry and corrosion behavior. Mater. Corros. Werkst. Korros. 72, 974–982 (2021).

Audi, A. A. & Sherwood, P. M. A. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of sulfate and bisulfate interpreted by Xa and band stucture calcualtions. Surf. Interface Anal. 29, 265–275 (2000).

Laplanche, G. et al. Reasons for the superior mechanical properties of medium-entropy CrCoNi compared to high-entropy CrMnFeCoNi. Acta Mater. 128, 292–303 (2017).

Tian, W. et al. The effect of chromium content on the corrosion behavior of ultrafine-grained CrxMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloys in sulfuric acid solution. Microstructures 3, 2023014 (2023).

Olsson, C. O. A. & Landolt, D. Passive films on stainless steels*chemistry, structure and growth. Electrochim. Acta 48, 1093–1104 (2003).

Keddam, M., Kuntz, C., Takenouti, H., Schuster, D. & Zuili, D. Exfoliation corrosion of aluminium alloys examined by electrode impedance. Electrochim. Acta 42, 87–97 (1997).

Ma, H. Y., Li, G. Q., Chen, S. C., Zhao, S. Y. & Cheng, X. L. Impedance investigation of the anodic iron dissolution in perchloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 44, 1177–1191 (2002).

Gilli, G., Borea, P. & Zucchi, F. & Trabanel.G. Passivation of Ni caused by layers of salts in concentrated H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 9, 673 (1969). &.

Ebersbach, U., Schwabe, K. & Ritter, K. On the kinetics of the anodic passivation of iron, cobalt and nickel. Electrochim. Acta 12, 927–938 (1967).

Kish, J. R., Ives, M. B. & Rodda, J. R. Corrosion mechanism of nickel in hot, concentrated H2SO4. J. Electrochem. Soc. 147, 3637 (2000).

Zhang, Y., Macdonald, D. D., Urquidi-Macdonald, M., Engelhardt, G. R. & Dooley, R. B. Passivity breakdown on AISI Type 403 stainless steel in chloride-containing borate buffer solution. Corros. Sci. 48, 3812–3823 (2006).

Macdonald, D. D., Sun, A., Priyantha, N. & Jayaweera, P. An electrochemical impedance study of alloy-22 in NaCl brine at elevated temperature: II. Reaction mechanism analysis. J. Electroanal. Chem. 572, 421–431 (2004).

Chen, M. Z. et al. Insights into the passivity and electrochemistry of CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy fabricated by underwater laser direct metal deposition. Corros. Sci. 237, 112289 (2024).

Laplanche, G. et al. Phase stability and kinetics of a σ-phase precipitation in CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 161, 338–351 (2018).

Chen, Y. M., Rudawski, N. G., Lambers, E. & Orazem, M. E. Application of impedance spectroscopy and surface analysis to obtain oxide film thickness. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, C563–C573 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Prof. Guillaume Laplanche and co-workers from Ruhr-University, Bochum, Germany for providing the alloy materials. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Michaela Buchheim for the scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy measurements. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung (BAM), Berlin, Germany through the PhD and PostDoc Program. The acquisition of the XP spectrometer at the University of Oldenburg was partially funded by the DFG through its Major Research Instrumentation Program (INST 184/144-1 FUGG). We also acknowledge funding for open access publication provided through the DEAL agreement.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., A.W., and O.O. conceived and designed the study. A.W. performed and validated the electrochemical experiments. A.-K.H. and I.B. conducted the XPS measurements, with I.B. contributing to data evaluation. M.v.d. Au carried out the ICP-MS measurements. J.W., A.W., O.O., I.B., and G.W. were involved in data analysis and result interpretation. A.W. prepared the initial draft with input from all authors. J.W., O.O., I.B., and G.W. provided critical feedback, refined the analysis, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wetzel, A., Hans, AK., von der Au, M. et al. Long-term corrosion studies of CrCoNi and CrMnFeCoNi in sulfuric acid. npj Mater Degrad 9, 86 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00637-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00637-z

This article is cited by

-

Effect of laser power on microstructure and hardness of a Cr-Co-Ni medium-entropy alloy

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)