Abstract

The microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) of mild steel 1010 caused by Vibrio injensis VS1, which was isolated from the industrial cooling tower system (CTS). The dual anticorrosion and biocidal properties of synthesized three molecules of N-substituted tetrabromophthalic inhibitors (N-TBI) were evaluated against corrosion and MIC. Among them, the 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2- octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) exhibited the superior performance against the corrosion and inhibition of MIC. The icorr was decreased by 95% and 90% under abiotic and biotic conditions, respectively. Further the increasing of Rct 1972.4 Ω cm2 and 1157.9 Ω cm2 in abiotic and biotic conditions. The synergistic effects of TOID adsorption on metal surface, suppressed the iron oxide layer formation and bacterial colonization as confirmed by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray Diffraction (XRD). This study highlights the potential of N-TBIs for environmentally friendly MIC control in CTS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) refers to the form of corrosion induced or caused by microorganisms, due to the physicochemical characteristics of the material interface in contact with the medium are altered as a result of the growth and metabolic activities of corrosion-inducing microorganisms within it1,2. The metabolic secretions, intermediates, or end products of microbial cells can all contribute to the degradation of materials, leading to failure and corrosion3,4,5. Numerous industries, including the gas and oil pipeline sectors, as well as the power, chemical, pharmaceutical, and effluent treatment industries, depend heavily on cooling tower systems (CTS). Furthermore, the metal deterioration as a result of microbial activity in CTS may lead to affect the cooling efficiency and also affect the heat exchange performance6. Thus, physicochemical factors, including alkalinity, electrical conductivity, temperature, and total dissolved solids can also affect the development of scaling and biofouling in CTS and the presence or absence of microorganisms. Cooling towers predominantly promote pitting corrosion due to microbial adhesion and the subsequent development of biofilm on metal surfaces7. Mild steel (MS) is the most important material utilized by industries, is typically utilized in cooling towers because of its high conductivity, availability, affordability, and strong mechanical properties8. MIC cannot be eliminated in CTS due to the appropriate temperature condition (25–35 °C), which promotes microbial growth9. Bacterial proliferation can lead to biofilm formation, which impacts heat transfer efficiency and promotes metal surface corrosion. Within a biofilm, bacteria produce an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that acts as for microbial attachment, influences the diffusion of gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, controls pH, and acquires both organic and inorganic nutrients. The microbes can act as both anode and cathode inside the biofilm, which creates a potential difference that initiates and accelerates the corrosion process10,11. Organic-based synthesized inhibitors are widely used in corrosion prevention because of their eco-friendly nature, renewable origin, low toxicity, and non-hazardous characteristics. In many industrial applications, organic corrosion inhibitors are essential for reducing the negative consequences of corrosion12.

The developments of an effective corrosion inhibitor were essential for protecting materials against corrosion. The effectiveness of the tetrabromophthalic inhibitor in corrosion control in CTS has been shown in our recent research13, For instance, demonstrated that tetrabromophthalic derivatives exhibit effective inhibition properties for carbon steel in acidic media due to their ability to form protective films through electron donation and adsorption mechanisms14. Moreover, investigated a bromine-containing hybrid epoxy inhibitor in acidic medium, reporting significant inhibition efficiency attributed to the synergistic effect of bromine atoms enhancing surface interaction and film formation on steel surfaces15. Numerous organic compounds were successfully employed in control of corrosion in different medium. Based on the literature survey, structurally modified tetrabromophthalic (TBP) based molecular materials were very limited14. Interestingly, reactions of substituted amine with tetrabromophthalic anhydride are facile and get high yield in short reaction time. Then obtained structurally modified TBP is become an one of the attractive molecular materials which possess O, Br, N and multiple bonds (aromatic ring) are considered to be an effective corrosion control.

In our previous study, synthesis of N-substituted tetrabromophthalic as corrosion inhibitor and its inhibition of microbial influenced corrosion in cooling water system was reported, Vignesh et al.13. In brief, synthesis of series of different structurally modified TBP with methoxy substituted aromatic compounds and amino acids N-substituted tetrabromophthalic inhibitor was synthesized and evaluated as a cathodic inhibitor for carbon steel API 5LX used in crude oil reservoir’s CTS. The weight loss results showed that 79% inhibition efficiency against chemical corrosion and 63% MIC against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In the current study, we design and synthesized the alkyl and aromatic substituted amine with tetrabromophthalic anhydride to explore the maximum inhibition efficiency of corrosion and MIC.

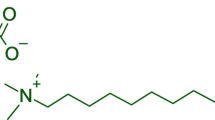

In this context, N-substituted tetrabromophthalic inhibitor (N-TBI) have become promising solutions. From the MS 1010 metal surfaces, these inhibitors form a stable protective layer that inhibits corrosion-causing anodic and cathodic reactions. They also have an effective adsorption capacity. Bromine atoms had isolated pairs of electrons that were capable of transmitting them to the d orbital of the Fe and provided the highest inhibition efficiency16. The advantages of organic corrosion inhibitors remain an effective approach in various industrial applications due to their ability to reduce metal degradation or deterioration by forming protective barriers on the metal surface and reducing the microbial colonization. In the present study, the corrosion-causing bacteria were isolated from cooling tower biofilm in the effluent treatment industry and then analyzed for their corrosion-causing ability for the synthesis of cost-effective and efficient corrosion inhibitors to analyze the CTS biocorrosion issues commonly encountered in industrial systems. To achieve this, the N-TBI was synthesized and characterized.

Results and Discussion

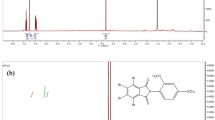

FT-IR spectrum of compounds (I –III)

Compound -I: 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) balletwhite solid.1713 (-C=O-) ;1337 (-C-N-); Aromatic ring:1379 (-C=C) ;2929 (C-H), sp2hybridized, 1125 (C-Br); aromatic). Compound -II: 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID): shiny white crystalline solid.1713 (-C=O-) ;1337 (-C-N-); Aromatic ring:1379 (-C=C) ;2929 (C-H), sp2hybdridized, 1125 (C-Br); aromatic). Compound – III:4,5,6,7 - tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID): white solid.1717 (-C=O-); 1337 (-C-N-); Aromatic ring: 1407(-C=C); 2958 (C-H; sp2 hybridization), 1120 (C-Br; aromatic) showed in Fig. 1.

1HNMR spectrum of compounds (I –III)

Compound -I: 1HNMR (CDCl3; 400 MHz); the terminal methyl group (-CH3-) present in the 4 4-butylaniline gives a signal of 0.9 ppm, and the methylene groups (-CH2-) present in the compound give signals in 1.3–1.6 ppm, respectively. The magnetically and chemically equivalent protons attached to the aromatic ring are arranged in the range of 7.0–7.3 ppm shown in Fig. 2. Compound -II: 1HNMR (CDCl3; 400 MHz); the methyl groups (-CH3-) present in the compound give signals in 1.0–1.7 ppm respectively shown in Fig. 3. Compound – III: 1HNMR (CDCl3; 400 MHz); the methyl group present in the compound gives signals in 1.0 ppm respectively. All the protons in the aromatic ring are equally arranged in the range of 7.0–7.6 ppm shown in Fig. 4.

Powder X-ray Diffraction analysis of compound (I–III)

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) is a versatile technique to determine the phase, size, composition, purity, qualitative and quantitative analysis, lattice parameters, and has recently been used for the structure morphology of the materials17. The obtained PXRD diffraction was analyzed by using an X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα(1.54 Å) radiation operating at 30 kV and 20 mA in the range of 10–90 (2θ) with of 2 min. The PXRD pattern for synthesized compounds (I–III) is shown in Fig. 5. The PXRD pattern of all the compounds (TBID, (TOID), and (TDID) shows the crystalline character in nature. Usually, the crystalline nature of compounds improves their stability and solubility and also enhances their applications in the fields of biological, pharmaceutical, material sciences, and electronics18.

Physicochemical parameters analysis of CTS water

The cooling tower system (CTS) water had a turbidity of 6.16 ± 0.4 NTU and an acidic pH of 5.73 ± 0.1. A chloride content of the CTS water at 631 ± 1.5 mg/L, high conductivity of 2374 ± 0.9 µS/cm, high concentration of TSS (953 ± 7 mg/L) was observed, and TDS at 834 ± 3 mg/L were noted. Alkalinity of the CTS water at 1617 ± 2.7 mg/L, sulfate content (835 ± 0.7 mg/L), hardness (985 ± 2 mg/L), and COD all reached 2512 ± 4.5 mg/L. The results of these physico-chemical properties indicate significant risks of corrosion for the components of the CTS water19.

Biofilm inhibitory assay

The biofilm assay was performed to analyse the inhibition efficiency of the synthesized N-substituted Tetrabromophthalic inhibitors against corrosive bacteria V. injensis isolated from the cooling tower biofilm. The biofilm inhibition analysis using the synthesized inhibitor at different concentrations of 100, 200, and 300 ppm, as shown in Fig. 6. Because of biofilm stacking, the biofilm retains crystal violet dye, as seen by the violet color variations, indicating the inhibitor’s potential to prevent EPS formation. The results showed that biofilm development was significantly reduced at all tested concentrations20. The highest inhibition efficiency (IE) was observed at 300 ppm of inhibitor TBID, showing 39%, TOID, 77%, and TDID, 63% in 300 ppm of inhibitor. The finding suggests that the synthesized inhibitor was effectively preventing biofilm development. The biofilm inhibitory results were used to determine which of the inhibitor concentrations would be used to assess the biocorrosion analysis of mild steel 101021,22.

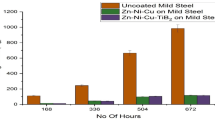

Weight loss analysis

The weight loss analysis was performed to analyse the mass loss of mild steel 1010 with the presence of V. injensis, corrosion-causing bacteria isolated from the CTS after incubation for 14 days. Over all the weight loss results before and after 14 days of incubation were shown in Table 1 and Fig. 7. S1 served as the abiotic control, containing only the corrosion test solution (CTS water) without any bacterial inoculum or corrosion inhibitor. Mild steel 1010 coupons were immersed in 400 mL of this CTS water in 500 mL conical flasks, and the system was incubated at 37 °C for 14 days under static conditions. This setup was used to assess the baseline corrosion behavior of the metal in the absence of microbial or chemical influences. The mass loss of the control system 1 (S1) was 87.4 ± 0.3 mg, and the biotic system 2 (S2) was 106.2 ± 0.5 mg of mass loss, these results indicate that the V. injensis strain was vigorously causing corrosion compared to S1. The systems without V. injensis S3-S5 were used to assess the chemical corrosion mass loss in the presence of inhibitors. The mass loss recorded was 44.7 ± 0.2 mg for inhibitor TBID (system 3), 13.2 ± 0.5 mg for inhibitor TOID (system 4), and 21.4 ± 0.1 mg for inhibitor TDID (system 5), followed by the corrosion rate of this system recorded as 0.59, 0.17, and 0.27 mm/year respectively23. However, the system’s presence of V. injensis with the inhibitor S6–S8 was used to assess the biocorrosion mass loss. The mass loss recorded was 57.2 ± 0.3 mg for inhibitor TBID (system 6), 25.7 ± 0.5 mg for inhibitor TOID (system 7), and 40.4 ± 0.2 mg for inhibitor TDID (system 8), followed by the corrosion rate of this system recorded as 0.75, 0.33, and 0.53 mm/year, respectively. Weight loss analysis offers a cumulative and long-term measure of corrosion inhibition performance, reflecting the actual mass loss over time due to metal dissolution. It validates the inhibitor’s performance under prolonged exposure and mimics real-world conditions. Among the three inhibitors, the highest inhibition efficiency (IE) was found at 85% for the TOID inhibitor and 71% for the TOID inhibitor in the presence of V. injensis. Fig. S1 revealed that the 14 days growth pattern of the V. injensis in CTS water corrosion medium and in presence inhibitor substantially suppressed bacterial growth. Overall, the weight loss data highlighted the effectiveness of inhibitors for decreasing corrosion while also decreasing the MIC24,25.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

EIS analysis showed the different corrosion behaviors in various systems. The Nyquist plot of the mild steel 1010 with absence and presence of inhibitor and V. injensis were presented in Fig. 8, and the EIS circuit were shown in Fig. 9, and the EIS parameters including constant phase element (CPE), solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), surface coverage (θ), dispersion coefficient (n), and inhibition efficiency (ɳ%) were shown in Table 2. The control system (S1) had an Rct of 684.94 ± 1.5 Ω cm2 and a CPE of 8.0 ± 0.3 × 104 F, reflecting moderate corrosion resistance. The biotic control (S2) revealed the remarkable lowering of Rct to 310.98 ± 1.2 Ω cm2 and an increase in CPE (2.05 ± 0.1 × 10−2 F), which confirms that the V. injensis corrosion-causing bacteria isolated from CTS water were active nature in causing microbial corrosion. The presence of inhibitors without bacteria showed a very significant improvement in Rct, where TOID (S4) exhibited the maximum corrosion resistance (Rct = 1972.4 ± 2.9 Ω cm2, ɳ% = 65%), than TDID (S5) (Rct = 1625.5 ± 2.0 Ω cm2, ɳ% = 57%), and TBID (S3) (Rct = 1537.6 ± 3.6 Ω cm2, ɳ% = 55%). The occurrence of inhibitor with V. injensis (S6–S8) led to an increase in Rct values with respect to their abiotic control, which was confirmed by the inhibitor interference with the bacterial metabolism, the TOID (S7) showed Rct = 1157.9 ± 1.7 Ω cm2, the TDID (S8) shows Rct = 1070.1 ± 1.5 Ω cm2, and the TBID (S6) shows Rct = 856.69 ± 1.3 Ω cm2, respectively. The inhibition efficiency with TOID (S7) showing the highest inhibition efficiency (ɳ% = 73%), followed by TDID (S8) (ɳ% = 70%) and TBID (S6) (ɳ% = 63%). The downturn in the Rs values in inhibited systems compared to S1 and S2 abiotic and biotic control sysytems represents enhanced charge transfer behavior at the metal-electrolyte interface due to likely inhibitor adsorption. The EIS analysis helps to understand the surface interactions and protective film formation on the metal surface. In this study, the presence of an inhibitor leads to a significant increase in Rct, indicating that a stable and well-adhered protective film formed on the metal surface. This film serves as both a physical and electrochemical barrier, preventing corrosive ions from reaching the metal and reducing electron transfer reactions responsible for corrosion. Variation in the value of charge transfer resistance and CPE was clear evidence that the inhibitor established the strongest protection barrier against MIC due to their good adsorption and film-forming properties26. Overall, these findings confirm that whereas microbial activity contributes to causing corrosion, the investigated inhibitors successfully offset MIC, with TOID and TDID possessing the greatest corrosion resistance and inhibition efficiency27,28.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

The θ and η% parameters were calculated using the following equations29 with specified Rct values:

In Eq. (2) \({R}_{{Ct}}^{({Control})}\) and \({R}_{{Ct}}^{({inhibitor})}\) represent the Rct in the absence and presence of inhibitors, respectively.

Tafel polarization

Figure 10 shows the potentiodynamic polarization, the Tafel curves for mild steel 1010 under conditions with and without the inhibitor and V. injensis after 14 days of immersion. The potentiodynamic polarization parameters, including cathodic Tafel slope (βb), anodic Tafel slope (βa), corrosion potential (Ecorr), and corrosion current density (icorr) were presented in Table 3. The potentiodynamic polarization analysis carried out through different systems (S1–S8) provides profound insight into the electrochemical performance and effectiveness of the corrosion inhibitors within sterile as well as biotic conditions. The corrosion current density (icorr) was at (8.96 ± 0.01) × 10−5 A/cm2 while Ecorr was at −0.75986 ± 0.01 V within the control system (S1), giving rise to a corrosion rate of 1.04 ± 0.002 mm/year. Introduction of a biotic medium with V. injensis in S2 resulted in a higher icorr of (1.07 ± 0.02) × 10−4 A/cm2 and a higher Ecorr of −0.7357 ± 0.02 V, which represents an enhanced corrosion process with a corrosion rate of 1.24 ± 0.003 mm/year. This increased rate of corrosion in biotic conditions emphasizes the corrosive nature of microbiologically induced corrosion. In addition of 300 ppm of inhibitors TBID, TOID, and TDID in the sterile conditions (S3, S4, and S5) showed a significant reduction of icorr values to (7.94 ± 0.02) × 10−6 A/cm2, (4.39 ± 0.01) × 10−6 A/cm2, and (5.71 ± 0.01) × 10−6 A/cm2, respectively. Parallelly, the values of Ecorr moved to −0.7143 ± 0.01 V, −0.7167 ± 0.01 V, and −0.7269 ± 0.03 V. These changes reflect more noble-like behavior and an immense decrease in the corrosion rates to 0.09 ± 0.001 mm/year, 0.05 ± 0.002 mm/year, and 0.06 ± 0.001 mm/year, respectively. While using inhibitor alone, it can be observed the reduction of corrosion current. It is due to the inhibiting effect of synthetic compounds. The estimated θ and η% for such inhibitors were significantly high, with S4 (TOID) being the highest at 95 ± 1.0%. Nevertheless, the occurrence of corrosion-promoting bacteria in systems S6–S8 with the same concentrations of the inhibitors led to higher icorr values of (3.10 ± 0.01) × 10−5 A/cm2, (1.05 ± 0.01) × 10−5 A/cm2, and (1.90 ± 0.01) × 10−5 A/cm2, respectively, Ecorr readings in such biotic-inhibited systems were found to be −0.62808 ± 0.02 V, −0.6828 ± 0.02 V, and −0.66731 ± 0.02 V. While these systems continued to show lower corrosion rates than the biotic control (S2), with the rates being 0.36 ± 0.001 mm/year, 0.12 ± 0.001 mm/year, and 0.22 ± 0.001 mm/year, the inhibition efficiencies fell to 71 ± 1.0%, 90 ± 3.0%, and 82 ± 2.0%, respectively. The structural features of TOID is quite interesting in comparison with TBID and TDID. TOID possess long octyl chain, which could facile the solubility in all solvents. Further, the linkage of tetrabromophthalic moiety of -N- with 4- butyl aniline and 2,5 -di -tert- butyl aniline could leads to form rigid structure TBID and TDID where as TOID having linkage with octyl chain. These structural features influences the inhibition efficiency. Although S7 (TOID with V. injensis) exhibits a negative Ecorr (−0.6828 ± 0.02 V) than S6 (−0.62808 ± 0.02 V) and S8 (−0.66731 ± 0.02 V). In electrochemical corrosion studies, Ecorr only cannot be directly interpreted as a measure of inhibition efficiency, especially in complex environments like MIC. The icorr and corrosion rate are more definitive indicators of corrosion severity. Shifting of Ecorr value in presence of inhibitor with bacteria can be observed in polarization. It can be assumed that inhibitor with available bacteria forms passivation on mild steel 1010. It is due to the adsorption of inhibitor and bacteria on the steel coupons. While using inhibitor also, shifting to positive side was also noticed. These results suggest that the inhibitors TOID and TDID are most effective against corrosion in the CTS water environment30,31.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

The θ and η% parameters were calculated using the following equations29 with specified icorr values:

In Eq. (4) \({i}_{{corr}}^{({Control})}\) and \({i}_{{corr}}^{({inhibitor})}\) represent the icorr in the absence and presence of inhibitors, respectively.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The FTIR spectroscopy analysis of mild steel 1010 is shown in Fig. 11. The corrosion products of mild steel 1010 in the presence of inhibitors TBID, TOID, and TDID reveal that distinct interactions between these inhibitors and the metal surface. The spectral peaks that correspond to the inhibitors’ functional groups such as aromatic C-Br stretching (TBID: 1125 cm−1; TOID: 1069 cm−1; TDID: 1120 cm−1), C=O stretching (TBID: 1713 cm−1; TOID: 1703 cm−1; TDID: 1717 cm−1), C-N stretching at 1337 cm−1, aromatic C=C stretching (TBID: 1379 cm−1; TOID: 1393 cm−1; TDID: 1407 cm−1), and =C-H stretching (TBID: 2929 cm−1; TOID: 2920 cm−1; TDID: 2958 cm−1) were observed in the spectra of the corrosion products, indicating adsorption of these inhibitors onto the mild steel 1010 surface. The adsorption is most probably due to the lone pairs of electrons on the nitrogen atoms of the C-N groups and the π-electrons of the aromatic rings, which coordinate with the empty d-orbitals of iron atoms to form a chemisorbed protective film. Shifts in the stretching frequencies of the inhibitor’s functional groups indicate the strong coordination between the inhibitors and the mild steel 1010 metal surface32. Electrons from functional groups like C=O, C–N, and aromatic systems are transferred to the iron metal surface during this coordination, which is related to the chemisorption process. The results of the electrochemical investigations showed a significant increase in Rct. The FTIR and electrochemical analyses confirm that TBID, TOID, and TDID form a protective layer by chemisorbing onto the mild steel 1010 metal surface33.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

X-ray diffraction spectroscopy

X-ray diffraction (XRD) scan of mild steel 1010 corrosion by V. injensis induced MIC with and without inhibitor demonstrated the presence of various corrosion products shown in Fig. 12. The control sample showed strong peaks of Fe3O4 and Fe2O3, indicating the existence of oxidized iron phases due to significant chemical corrosion. For biotic control, increased peaks of hematite and lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) confirm aggressive microbial corrosion caused by V. injensis that accelerates the oxide development. The inhibitor system exhibited strong decreases in intensities of such phases, displayed weak peaks of Fe3O4, indicating formation of a strong protective film with restricted oxidation, which indicates that TBID, TOID, and TDID successfully suppressed the corrosion. When the corrosive bacteria V. injensis were inoculated in the inhibitor system, corrosion product development was reported; however, the inhibitors reduced their intensity, indicating efficient inhibition of the microbial corrosion. The occurrence of goethite (α-FeOOH) and iron chloride (FeCl2) phases under biotic-inhibitor conditions indicates microbial interaction with inhibitor molecules, with possible modification of biofilm adhesion and EPS synthesis. TOID showed better inhibition by significantly reducing the Fe3O4 and Fe2O3 intensity, followed by TBID and TDID, which also showed good corrosion resistance ability. The results confirm that the evaluated inhibitors effectively mitigate MIC by modifying electrochemical and biological corrosion pathways, decreasing the oxide formation, and supporting the passivation34,35.

S1 abiotic control. S2 biotic control. S3 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID). S4 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID). S5 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID). S6 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-(4-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TBID) with V. injensis. S7 4,5,6,7 -tetrabromo-2-octylisoindoline-1,3-dione (TOID) with V. injensis. S8 tetrabromo-2-(2,5-di-tert-butyl phenyl) isoindoline-1,3-dione (TDID) with V. injensis.

Toxicity analysis

The predicted acute and chronic toxicity data for the starting material of synthesized corrosion inhibitor were summarized in Table S1. Overall, the compounds exhibited relatively low to moderate level of aquatic and terrestrial toxicity, with distinct variations in their toxicological profiles according to their chemical structure. The TBPA showed, lower LC50 and chronic (ChV) values which was demonstrated that the moderate predicted toxicity in the aquatic species was observed36. In contrast, 4-butyl aniline, octyl amine, and 2,5-di-tert-butyl aniline, showed the higher LC50 and ChV values, suggesting that lowering acute and chronic toxicity in the aquatic species. These compounds showed the lesser environmental, ecological hazard. The terrestrial organism earthworm, all the compounds exhibited higher LC50 values, ranging from 1.79 × 102 to 3.39 × 102 mg/kg, reveals that lower toxicity in soil environments compared to aquatic systems37.

Proposed inhibition mechanism of MIC by N-TBI

Inhibition of MIC in mild steel 1010 immersed in CTS water with V. injensis encompasses a multi-component mechanism enabled by N-TBIs. The physicochemical characteristics of the CTS water, such as an acidic pH of 5.73 ± 0.1, high turbidity 6.16 ± 0.4 NTU, high total suspended solids 953 ± 7 mg/L, and high chloride content 631 ± 1.5 mg/L, and thus promote a corrosion-favorable environment. Biofilm assay revealed that the N-TBIs at 300 ppm concentration significantly reduce the biofilm formation caused by V. injensis, with inhibitory efficacy up to 77%, and successfully reduce the production of EPS on the mild steel 1010 surface. TOID inhibitors significantly reduced the weight loss of 25.7 ± 0.5 mg/cm2 than the biotic control system S2 (106.2 ± 0.5 mg) with an inhibition efficiency of 71%. In the EIS results findings, the Rct increases from 310.98 ± 1.2 Ω·cm2 in biotic control to 1157.9 ± 1.7 Ω·cm2 in the TOID-inhibited system, indicating increased corrosion resistance in the mild steel 101027. The potentiodynamic polarization experiments showed the icorr to reduce from 1.07 ± 0.02 × 10−4 A/cm2 in biotic control to 1.05 ± 0.01 × 10−5 A/cm2 with TOID inhibitor-treated system, indicating that effective decrease in corrosion rate30. The FTIR spectroscopy analysis confirmed the adsorption mechanism of N-TBIs on the steel surface, showing characteristic peaks for functional groups like aromatic C-Br stretching, C=O stretching, and C-N stretching, the structural differences among the compounds are responsible for the observed inhibitory efficiencies. TBID contains a 4-butylphenyl group that offers moderate hydrophobicity38. However, the limited chain length and the presence of the phenyl ring restrict optimal surface adsorption, leading to moderate inhibition performance. In contrast, TOID, which features a linear octyl chain directly bonded to the isoindoline nitrogen, demonstrates superior inhibition. The extended alkyl chain enhances hydrophobic character and promotes stronger van der Waals interactions with the metal surface, allowing the formation of a more compact and uniform passive film. TDID, while containing two tert-butyl groups that increase hydrophobicity, suffers from significant steric hindrance due to their structure. This interferes with effective adsorption and leads to a loosely packed inhibitor layer, reducing its protective performance compared to TOID39. Shifting of Ecorr value in presence of inhibitor with bacteria can be observed in polarization. It can be assumed that inhibitor with available bacteria forms passivation on mild steel 1010. It is due to the adsorption of inhibitor and bacteria on the steel coupons. While using inhibitor also, shifting to positive side was also noticed, which are indicative of chemisorption interactions that create a protective barrier against corrosive agents, the halogen atoms further improve the inhibition efficiency by encouraging strong interactions that support the metal surface’s protection23. The XRD analysis supports these findings by demonstrating corrosion product phase depletion, such as Fe3O4 and Fe2O4334, in inhibited samples, indicating N-TBIs effectively prevent microbial-induced corrosion through the alteration of electrochemical pathways and prevention of biofilm growth. All the experimental measurements, including Tafel polarization results and EIS, weight loss and biofilm assay showed that TOID consistently performed better than TBID and TDID. It showed higher charge transfer resistance and lower corrosion current density, indicating more effective inhibition under microbial corrosion conditions. Additionally, TOID exhibited enhanced biofilm inhibition, which supports its application as a dual-function inhibitor.

Overall, in this study, three N-substituted tetrabromophthalic compounds such as TBID, TOID, and TDID were successfully synthesized and structurally characterizedhree by FTIR, 1HNMR spectroscopy, and XRD. These compounds have a crystalline nature, indicating increased physicochemical stability and potential use in corrosion protection. The study also analysed the physicochemical parameters of CTS water, which has high acidity, turbidity, and high ionic concentration, this condition favors the development of MIC caused by V. injensis isolated from CTS. Based on the biofilm assay, the synthesized inhibitors, TOID, demonstrated the maximum inhibition efficiency (77%) at 300 ppm concentration. Weight loss results showed that TOID and TDID significantly inhibited corrosion rates in abiotic and biotic systems, with TOID exhibiting maximum inhibition efficiency of 85% under sterile and 71% under microbial conditions. EIS further confirmed these findings, with TOID representing the higher Rct 1972.4 ± 2.9 Ω cm2 in abiotic and 1157.9 ± 1.7 Ω cm2 in biotic conditions, confirming its greater adsorption efficiency. Potentiodynamic polarization studies supported these findings by showing significant reductions in icorr and corrosion rates across all systems containing inhibitors. Surface corrosion product FTIR and XRD analysis showed efficient chemisorptions of inhibitor molecules on the mild steel 1010 surface, creating stable, protective films that inhibit both cathodic and anodic processes, prevent oxide growth, and minimize microbial biofilm formation. TOID and TDID are effective and environment-friendly molecules to fight against the MIC in CTS.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

The starting materials, tetrabromophthalic anhydride (TBPA) (98%), 4-butyl aniline (98%), n-octyl amine (99.9%), and 2,3-ditert-butyl aniline (99%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, India. Solvents and required reagents of analytical grade were used in synthesis and purification. 1H NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker 400 spectrometer using CDCl3 as solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal reference, and units are measured in ppm. FT-IR spectrum was recorded by using the KBr pellet method using an FT-IR spectrometer JASCO in the spectral region of 4000–400 cm−1.

Synthesis of N-substituted Tetrabromophthalic compounds (I–III)

The compounds (I–III) were prepared based on the reported procedure18. The measured quantity of Tetrabromophthalic anhydride (TBPA) suspended in glacial acetic acid was taken in a two-necked RB flask equipped with a condenser. Then the respective amines, (2) 4-butyl aniline (0.1492 g 0.3 mL); (3) n-octyl amine (0.1291 g); and (4) 2,3 di-tert butyl aniline (0.2053 g) were dissolved in approximately 5 mL of glacial acetic acid. The amine was added to the TBPA mixture drop by drop using a funnel. After completion, the reaction mixture was gently refluxed overnight. The reaction is monitored by thin layer chromatography. Then the solid compound was subsequently cooled to RT, filtered, and then extracted with ethyl acetate. Further, the evaporation of the ethyl acetate layer gives the product, and the obtained product was recrystallized with ethanol. The yield of the product (I–III) was 80%. The molecular structures of starting materials, general synthetic scheme and obtained molecular structure of the compounds was given in the Scheme 1–318.

Sample collection

The biofilm samples were obtained from the inner surface of the cooling tower system (CTS), and water was collected from the CTS at Ranipet Tannery Effluent Treatment Limited, Ranipet, Tamil Nadu, India (latitude 12.920435° and longitude 79.348974°). The sterile plastic container was used to collect the biofilm sample and CTS water, which were then stored at 4 °C until they were processed in the laboratory.

Physicochemical parameters of CTS water

The key parameters of the collected CTS water samples were analysed, including color, conductivity, total suspended solids (TSS), chloride (Cl−), pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and temperature. Potassium dichromate method was used to analyse the COD content of the collected CTS water using Merck Spectroquant TR 320 thermo reactor40,41.

Isolation and culture condition of the bacteria

The 1 gram of the CTS biofilm sample was aseptically collected and accurately weighed using a sterile spatula. The sample was then transferred into a sterile container containing sterile double-distilled water and homogenized thoroughly to dislodge the microbial cells from the biofilm matrix. Serial tenfold dilutions were prepared under aseptic conditions using sterile double-distilled water as the diluent to reduce the microbial load to a countable range. From each appropriate dilution, a 0.1 ml aliquot was aseptically pipetted and inoculated onto sterile Petri plates by the pour plate method42,43. The plates were poured with iron bacteria isolation medium, consisting of (g/L): dextrose (0.150), calcium nitrate (0.010), dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (0.050), ammonium sulphate (0.500), calcium carbonate (0.100), cyanocobalamin (0.00001), magnesium sulphate heptahydrate (0.050), potassium chloride (0.050), thiamine (0.0004), agar (10.0), respectively. The plates were further incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colonies with distinct morphologies were randomly selected from all selective plates, and a single colony was further purified using the streak plate method44. The robust bacterial inoculum was cultivated from individual colony in LB broth, placed in an orbital shaker and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with a speed of 150 rpm45.

Identification of the bacteria

The selected bacterial DNA was extracted using a modified salting-out approach that included SDS and Proteinase K digestion as described by 46, followed by ethanol precipitation and purification. The DNA quality and concentration were analysed using Nanodrop 2000, with an optimal 260/280 ratio, and the integrity was validated using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The 16S rRNA was amplified using the universal primers 27 F and 1492 R, and the PCR products were analyzed 1.5% agarose gel. The sequencing was done using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) in a PCR thermal cycler, followed by sequence alignment and editing were carried out in MEGA 7 software. The Species identification was confirmed using NCBI BLAST analysis based on sequence similarities. The 16S rRNA sequence was 100% identical to Vibrio injensis (VS1) and has been submitted to the NCBI GenBank, and obtained the accession number is PQ432486. The phylogenetic tree of the identified Vibrio injensis VS1 was shown in Fig. 1347,48.

Biofilm inhibition assay

The biofilm inhibitory assay was assed using microtiter plate method, the overnight grown culture in Luria Bertani (LB) broth were dilated 1:20 ratio using sterile LB medium. The sterile polystyrene microtiter plate was filled with 100 µl of diluted bacterial suspension and various dosages of the inhibitor (100 ppm, 200 ppm, and 300 ppm). The identical, inhibitor-free culture broth was used in the control wells, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, the media was removed from the plates and rinsed with PBS, and then each well was loaded with 120 µL of crystal violet, which was left there for 20 min. Then, the acetic acid 125 µL was added per well and incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes. Biofilm formation was finally quantified by a microplate reader at OD 595 nm49,50.

Coupon preparation

Weight loss was used to assess the corrosion behavior of mild steel 1010 in the presence of bacteria. The mild steel sample had the dimensions of 2.5 cm2 and a thickness of 1 mm with the following chemical composition (wt%): C 0.2, P 0.50, Mn 0.2, S 0.03, and Fe 99.04. Tafel polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) studies were performed with rectangular coupons with 1 cm2 exposed surface area, while coupons with 2.5 cm2 surface area were used for weight loss respectively. Specimens were sequentially polished with silicon carbide metallurgical papers with 600, 800, 1000, and 1200 grit, thoroughly rinsed with Milli-Q water, cleaned using acetone to remove grease, and dried under a nitrogen gas stream. They were kept in a desiccator until they had to be utilized again after drying. Before immersion, the coupons were weighed and subjected to ultraviolet radiation for 30 minutes51,52.

Weight loss analysis

The different grade sandpaper were used to polish the mild steel 1010 coupons to achive mirror finish, the sterile polished coupons were immersed in 400 ml of sterile CTS water pH of 5.93 ± 0.1 in 500 ml conical flasks, which were done in triplicate and the system was incubated at 37 °C for 14 days under static conditions. The initial mass of the triplicate coupons was measured before immersion in the corrosion system. The system 1 served as the abiotic control, this setup was used to assess the baseline corrosion behavior of the metal in the absence of microbial or chemical influences, while system 2 acted as the biotic control, inoculated with V. injensis VS1 (~1.2 × 104 CFU/mL). The systems 3, 4, and 5 contain 300 ppm concentration of inhibitors, whereas the systems 6, 7, and 8 consist of 300 ppm of inhibitors with V. injensis at a range of around 1.2 × 104 CFU/mL. All the systems were incubated at 37 °C for a period of 14 days41,53. After 14 days the exposed with corrosion medium, the coupons were taken out and pickled in Clark’s solution, which was made up of 5% stannous chloride with 2% antimony trioxide mixed in strong hydrochloric acid (HCl), while continually stirred for five to ten minutes at room temperature. After being cleaned using deionised water, using an air drier, the specimens were dried. Following the guidelines established by the National Association of Corrosion Engineers, the weight of each coupon was noted, and the corrosion rates were determined using Eq. (5).

where K = 8.76 × 104, Wl = Weight loss (g), mmy = corrosion rate (millimeter per year penetration), D = density of metal (g/cm3), A = exposure area (cm2), T = exposure time (hrs).

Electrochemical analysis

The electrochemical analysis, open circuit potential (OCP), Tafel polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were performed Metrohm Autolab (PGSTAT204) with the NOVA software were used (Version 2.1.7, https://www.metrohm.com/en_in/service/software-center/nova.html). Platinum mesh served as the counter electrode, silver chloride (Ag/AgCl with 3 M (KCl)) was selected as the reference electrode, and the working electrode was mild steel 1010 with a surface area of 1 cm2. The EIS was performed under stable OCP, a 10 mV sinusoidal voltage signal with a frequency range of 10−2–105 Hz54, and a scan rate is 0.010 V/min was used. The tafel polarization was carried out, with positive potential sweep was conducted up to +200 mV and the negative potential sweep was conducted up to −200 mV about the Ecorr at a scanning rate of 0.002 V/s55.

Surface analysis

The corrosion product of mild steel 1010 was completely dried and further mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) as pellets with a consistent composition. KBr pellets were analyzed by using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) model of (PerkinElmer Spectrum IR, Version 10.6.0) within the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 8 cm−1 and 64 scans per spectrum for the characterization56,57. The mild steel 1010 corrosion products that were collected from systems S1 to S8 were analyzed via X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis utilizing a Bruker D8 equipment that was configured with a scintillation counter detector in combination with a LynxEye. The investigation used X-ray tube settings of 40 kV and 30 kV and covered an angular range of 5–140° 58.

Toxicity analysis

The ECOSAR (version 2.0) was used to estimate the aquatic toxicity for starting material of the synthesized corrosion inhibitors. The model estimates a chemical’s acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic organisms, including fish, Daphnid, Green Algae, Mysid and aquatic invertebrates. Specifically, the median lethal concentration (LC50), median effective concentration (EC50), and chronic value (ChV) for various species are predicted36.

Statistical analysis

All the experiment experiments were conducted in triplicate and appropriate data are presented as standard deviation (mean±). The values of the difference was analysed by the one-way variance (ANOVA) test (p < 0.05).

Data availability

The relevant data previously unpublished and discussed herein are available from the corresponding authors.

References

Moradi, M., Ghiara, G., Spotorno, R., Xu, D. & Cristiani, P. Understanding biofilm impact on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analyses in microbial corrosion and microbial corrosion inhibition phenomena. Electrochim. Acta 426, 140803, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2022.140803 (2022).

Fu, Q. et al. Corrosion mechanism of Pseudomonas stutzeri on X80 steel subjected to Desulfovibrio desulfuricans under elastic stress and yield stress. Corr. Sci. 216, 111084, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111084 (2023).

Madirisha, M., Hack, R. & Van Der Meer, F. Simulated microbial corrosion in oil, gas and non-volcanic geothermal energy installations: the role of biofilm on pipeline corrosion. Energy Rep. 8, 2964–2975, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.01.221 (2022).

Rajala, P., Nuppunen-Puputti, M., Wheat, C. G. & Carpen, L. Fluctuation in deep groundwater chemistry and microbial community and their impact on corrosion of stainless-steels. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153965, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153965 (2022).

Shrestha, R. et al. Anaerobic microbial corrosion of carbon steel under conditions relevant for deep geological repository of nuclear waste. Sci. Environ. 800, 149539, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149539 (2021).

Touir, R. et al. Corrosion and scale processes and their inhibition in simulated cooling water systems by monosaccharides derivatives. Desalination 249, 922–928, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2009.06.068 (2009).

Pramanik, S. K. et al. Bio-corrosion in concrete sewer systems: mechanisms and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 921, 171231, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171231 (2024).

El-Shamy, A., Soror, T., El-Dahan, H., Ghazy, E. & Eweas, A. Microbial corrosion inhibition of mild steel in salty water environment. Mater. Chem. Phys. 114, 156–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2008.09.003 (2008).

Purwasena, I. A., Karima, A., Asri, L. A. T. W. & Setiawan, A. R. The potency of spores and biosurfactant of Bacillus clausii as a new biobased sol-gel coatings for corrosion protection of carbon steel ST 37 in water cooling systems. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 18, 100452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100452 (2023).

Lomakina, G. Role of biofilms in microbiologically influenced corrosion of metals. Herald of the Bauman Moscow State Technical University Series Natural Sciences 1, 100–125, https://doi.org/10.18698/1812-3368-2020-1-100-125 (2020).

Telegdi, J., Shaban, A., & Trif, L. Review on the microbiologically influenced corrosion and the function of biofilms. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhibit. 9. https://doi.org/10.17675/2305-6894-2020-9-1-1 (2020).

Maleki, B. et al. Facile synthesis and investigation of 1,8-dioxooctahydroxanthene derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. New J. Chem. 40, 1278–1286, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nj02707a (2015).

Vignesh, K. et al. Synthesis of novel N-substituted tetrabromophthalic as corrosion inhibitor and its inhibition of microbial influenced corrosion in cooling water system. Sci. Rep. 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76254-8 (2024).

Fouda, A., Desoky, A. & Ead, D. Anhydride derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solutions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 8, 8823–8847, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1452-3981(23)12931-2 (2013).

El-Aouni, N. et al. Hybrid epoxy/Br inhibitor in corrosion protection of steel: experimental and theoretical investigations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 1033–1049, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31171-7 (2023a).

Tan, L., Li, J. & Zeng, X. Revealing the correlation between molecular structure and corrosion inhibition characteristics of N-Heterocycles in terms of substituent groups. Materials 16, 2148, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16062148 (2023).

Bunaciu, A. A., Udriştioiu, E. G. & Aboul-Enein, H. Y. X-Ray diffraction: instrumentation and applications. Critic. Rev. Anal. Chem. 45, 289–299, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2014.949616 (2015).

Swathi, K. et al. A solution processed ultrathin molecular dielectric for organic field-effect transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 1, 485–493, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.8b00109 (2019).

Asgari, G., Khazaei, M., Seidmohammad, A., Mansoorizadeh, M. & Talebi, S. Reclamation of treated municipal wastewater in cooling towers of thermal power plants: determination of the wastewater quality index. Water Resou. Industry 29, 100207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wri.2023.100207 (2023).

Caigoy, J. C., Xedzro, C., Kusalaruk, W., & Nakano, H. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antimotility signatures of some natural antimicrobials against Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 369. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnac076 (2022).

Kokilaramani, S. et al. Bacillus megaterium-induced biocorrosion on mild steel and the effect of Artemisia pallens methanolic extract as a natural corrosion inhibitor. Archiv. Microbiol. 202, 2311–2321, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-020-01951-7 (2020).

Kanwal, M., Khushnood, R. A., Adnan, F., Wattoo, A. G. & Jalil, A. Assessment of the MICP potential and corrosion inhibition of steel bars by biofilm forming bacteria in corrosive environment. Cement Concrete Composites 137, 104937, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.104937 (2023).

Ituen, E., Ekemini, E., Yuanhua, L. & Singh, A. Green synthesis of Citrus reticulata peels extract silver nanoparticles and characterization of structural, biocide and anticorrosion properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1207, 127819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127819 (2020).

Narenkumar, J., Ramesh, N., & Rajasekar, A. Control of corrosive bacterial community by bronopol in industrial water system. 3 Biotech 8, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-1071-4 (2018).

Berrissoul, A. et al. Assessment of corrosion inhibition performance of origanum compactum extract for mild steel in 1 M HCl: weight loss, electrochemical, SEM/EDX, XPS, DFT and molecular dynamic simulation. Ind. Crops Prod. 187, 115310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115310 (2022).

Qian, H. et al. Accelerating effect of catalase on microbiologically influenced corrosion of 304 stainless steel by the halophilic archaeon Natronorubrum tibetense. Corrosion Sci. 178, 109057, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.109057 (2020).

Sayed, M. Y. E. et al. Steel Anti-Corrosion behavior for pure and MG-doped CUO nanoparticles in different media: RAMAN, potentiodynamic polarization and electrochemical impedance analysis. J. Bio- and Tribo-Corrosion, 10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-023-00807-z (2023).

Gerengi, H. et al. Dynamic Impedance-Based monitoring of ST37 carbon steel corrosion in sterilized manganese broth medium. Electrochim. Acta 525, 146011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2025.146011 (2025).

Majidi, H. J. et al. Fabrication and characterization of graphene oxide-chitosan-zinc oxide ternary nano-hybrids for the corrosion inhibition of mild steel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 148, 1190–1200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.060 (2019).

Messinese, E., Ormellese, M. & Brenna, A. Tafel-Piontelli model for the prediction of uniform corrosion rate of active metals in strongly acidic environments. Electrochim. Acta 426, 140804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2022.140804 (2022).

Sargolzaei, B. & Arab, A. Synergism of CTAB and NLS surfactants on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel in sodium chloride solution. Mater. Today Commun. 29, 102809, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102809 (2021).

Ouakki, M. et al. A study on the corrosion inhibition impact of newly synthesized quinazoline derivatives on Mild Steel in 1.0 M HCl: experimental, surface morphological (SEM-EDS and FTIR) and computational analysis. Int. J. Electrochem.Sci. 100795, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoes.2024.100795 (2024).

Timothy, U. J. et al. Assessment of Berlinia grandiflora and cashew natural exudate gums as sustainable corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in an acidic environment. Jo. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111578, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.111578 (2023).

Dalhatu, S. N. et al. L-Arginine grafted chitosan as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel protection. Polymers 15, 398, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15020398 (2023).

Verma, D. K. et al. Investigations on some coumarin based corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in aqueous acidic medium: electrochemical, surface morphological, density functional theory and Monte Carlo simulation approach. J. Mol. Liquids 329, 115531, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115531 (2021).

Massarsky, A. et al. Critical evaluation of ECOSAR and E-FAST platforms to predict ecological risks of PFAS. Environ. Adv. 8, 100221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2022.100221 (2022).

Singh, A. K., Bilal, M., Barceló, D. & Iqbal, H. M. A predictive toolset for the identification of degradation pattern and toxic hazard estimation of multimeric hazardous compounds persists in water bodies. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153979, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153979 (2022).

Verma, C., Quraishi, M. & Rhee, K. Hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity consideration of organic surfactant compounds: effect of alkyl chain length on corrosion protection. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 306, 102723, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2022.102723 (2022).

Wu, Q., Jia, X. & Wong, M. Effects of number, type and length of the alkyl-chain on the structure and property of indazole derivatives used as corrosion inhibitors. Mater. Today Chem. 23, 100636, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2021.100636 (2021).

Papp, L. A., Rodrigues, F. A., De Souza Júdice, W. A. & Araújo, W. L. Onsite wastewater treatment upgrade for water reuse in cooling towers and toilets. Water 14, 1612, https://doi.org/10.3390/w14101612 (2022).

Kokilaramani, S. et al. Application of photoelectrochemical oxidation of wastewater used in the cooling tower water and its influence on microbial corrosion. Front. Microbiol. 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1297721 (2024).

Pedramfar, A., Maal, K. B. & Mirdamadian, S. H. Phage therapy of corrosion-producing bacterium Stenotrophomonas maltophilia using isolated lytic bacteriophages. Anti-Corrosion Methods Mater. 64, 607–612, https://doi.org/10.1108/acmm-02-2017-1755 (2017).

Rajasekar, A., Anandkumar, B., Maruthamuthu, S., Ting, Y. & Rahman, P. K. S. M. Characterization of corrosive bacterial consortia isolated from petroleum-product-transporting pipelines. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1175–1188, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2289-9 (2009).

Liu, H. et al. Characterizations of the biomineralization film caused by marine Pseudomonas stutzeri and its mechanistic effects on X80 pipeline steel corrosion. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 125, 15–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2022.02.033 (2022).

Parthipan, P., AlSalhi, M. S., Devanesan, S. & Rajasekar, A. Evaluation of Syzygium aromaticum aqueous extract as an eco-friendly inhibitor for microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel in oil reservoir environment. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 44, 1441–1452, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-021-02524-8 (2021).

Javadi, A. et al. Qualification study of two genomic DNA extraction methods in different clinical samples. PubMed 13, 41–47, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25852760 (2014).

Lutz, Í. et al. Quality analysis of genomic DNA and authentication of fisheries products based on distinct methods of DNA extraction. PLoS ONE 18, e0282369, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282369 (2023).

Elumalai, P. et al. Characterization of crude oil degrading bacterial communities and their impact on biofilm formation. Environ. Pollut. 286, 117556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117556 (2021).

Pipattanachat, S., Qin, J., Rokaya, D., Thanyasrisung, P., & Srimaneepong, V. Biofilm inhibition and bactericidal activity of NiTi alloy coated with graphene oxide/silver nanoparticles via electrophoretic deposition. Sci. Rep. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92340-7 (2021).

Parthipan, P. et al. Neem extract as a green inhibitor for microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel API 5LX in a hypersaline environments. J. Mol.Liquids 240, 121–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2017.05.059 (2017).

Narenkumar, J. et al. Bioengineered silver nanoparticles as potent anti-corrosive inhibitor for mild steel in cooling towers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 5412–5420, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0768-6 (2017b).

Pakiet, M. et al. Gemini surfactant as multifunctional corrosion and biocorrosion inhibitors for mild steel. Bioelectrochemistry 128, 252–262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2019.04.005 (2019).

Azzouzi, M. E. et al. Moroccan, Mauritania, and senegalese gum Arabic variants as green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in HCl: weight loss, electrochemical, AFM and XPS studies. J. Mol. Liquids 347, 118354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118354 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. Enhancing corrosion resistance of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings on AM50 Mg alloy by inhibitor containing Ba(NO3)2 solutions. Int. J. Minerals Metallurgy Mater. 31, 2048–2061, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-024-2876-x (2024).

Vignesh, K. et al. Structurally modified tetrabromophthalic-based compounds as an anti-corrosion agent in microbial influenced saline systems. Front. Mater. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2025.1508966 (2025).

De Kerf, T., Pipintakos, G., Zahiri, Z., Vanlanduit, S. & Scheunders, P. Identification of corrosion minerals using shortwave infrared hyperspectral imaging. Sensors 22, 407, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22010407 (2022).

AlSalhi, M. S., Devanesan, S., Rajasekar, A. & Kokilaramani, S. Characterization of plants and seaweeds based corrosion inhibitors against microbially influenced corrosion in a cooling tower water environment. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 104513, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104513 (2022).

Muthukrishnan, P., Jeyaprabha, B. & Prakash, P. Adsorption and corrosion inhibiting behavior of Lannea coromandelica leaf extract on mild steel corrosion. Arab. J. Chem. 10, S2343–S2354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.08.011 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-398), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Author S.S. thanks the Management of BSACIST, for the award of “BS Abdur Rahman Junior Research Fellowship” and also authors (S.S., M.V.) are grateful to BSACIST for providing the necessary facility to do the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.V. conceptualization, data curation, methodology, and writing–original draft. S.S. conceptualization, methodology. M.V. investigation, visualization. R.D. Methodology. J.N. visualization. S.D. formal analysis, validation. M.A. resources. R.R. formal analysis, validation. A.R. project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing–review and editing. T.M. Project administration, supervision, validation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vignesh, K., Sujithra, S., Vajjiravel, M. et al. Dual-function of N-substituted tetrabromophthalic inhibitors for eco-friendly control of microbiologically influenced corrosion in industrial cooling systems. npj Mater Degrad 9, 101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00649-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00649-9

This article is cited by

-

A robust superhydrophobic ZnO@diatomite/epoxy coating for long-term corrosion-resistant magnesium alloys in marine environments

Journal of Materials Science (2025)