Abstract

Freeze-thaw damage (FTD) prediction is closely related to the durability design of concrete in cold regions. However, current machine learning models for FTD predominantly rely on numerical data, overlooking crucial textual information regarding the FTD process. This limits the prediction accuracy and interpretability of machine learning. To address this, we constructed a comprehensive dataset comprising 1851 samples extracted from 44 publications, which includes both numerical parameters and textual descriptions (i.e., corrosion environments, experimental processes, morphologies, and FTD mechanisms). A multimodal deep learning (MDL) model that integrated natural language processing (NLP) with deep neural networks (DNN) was then developed to predict FTD. The results show that compared with conventional DNN models, the multi-head self-attention model improves the prediction accuracy of concrete mass loss rate and relative dynamic elastic modulus by 8% and 21%, respectively. The visualization indicates that the improvement in the prediction accuracy of the developed MDL model is attributed to the prior knowledge in the textual information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used man-made material globally and accounts for ~7.5% of total anthropogenic CO₂ emissions1. To meet the requirement of the infrastructure construction and renewal, the usage of concrete materials will significantly increase in the coming decades, thereby substantially intensifying the burden on the environment2. Although using some low-carbon concrete can mitigate the increase in the anthropogenic CO₂ emissions3, ensuring concrete durability remains crucial for sustainable infrastructure4. In cold regions, freeze-thaw damage (FTD) is the most common factor to degrade the concrete durability5. Therefore, FTD prediction of concrete relates to the achievement of the sustainable infrastructure in these cold regions.

Traditional approaches for predicting concrete’s frost resistance include empirical regression methods6 and physics-based models7,8. However, empirical methods require extensive experimentation, incurring high labor costs and often yielding formulas applicable only to specific concrete types9. Physics-based models, which involve developing multi-scale, multi-physics numerical simulations based on water transport, phase transitions, and damage evolution, can elucidate FTD mechanisms at the mesoscale or microscale10. However, they frequently encounter convergence issues11.

In contrast, data-driven machine learning (ML) methods, with their capacity to capture high-dimensional nonlinear relationships, have recently emerged as a promising alternative12. Consequently, ML has been widely applied in the durability prediction of concrete in recent years13,14. Early studies demonstrated the potential of artificial neural networks (ANN) for predicting freeze–thaw damage in concrete15,16. Subsequently, Huang et al.17 enhanced ANN performance using a hybrid sparrow search algorithm, improving prediction accuracy by nearly 30%. More advanced ensemble learning models, such as random forest18 and extreme gradient boosting19,20, have since been employed to achieve greater prediction accuracy and robustness by integrating individual model outputs21.

Despite these advances, the performance of ML models heavily depends on the precision of manually engineered features22. The prevailing databases primarily comprise numerical data—cement content, aggregate gradation, number of freeze-thaw cycles, etc.—which restricts both prediction accuracy and model interpretability. In fact, the FTD in concrete is the results of the changes in microstructure, which is a complex physicochemical processes23. Therefore, textual information related to the FTD process of concrete is particularly important.

Although manual extraction of textual features such as those related to raw materials, corrosive environments, and microstructural variations is feasible, it is often constrained by limited domain expertise, subjective bias, and fatigue, thereby reducing data reliability24,25. In recent years, significant advancements have been made in natural language processing (NLP)26,27. NLP has been widely applied in various fields, such as alloy material design28, medical diagnosis29,30, microbial genomics31, and drug design32. In civil engineering, scholars have proposed lightweight large language model (LLM)–based frameworks for automated literature mining to systematically identify research hotspots and trends in sustainable concrete substitute materials33. One study developed an artificial language to represent concrete mixtures and their physicochemical properties, which was subsequently applied to predict compressive strength, evaluate variable importance, and identify chemical reactions34. Another study introduced a multi-agent LLM framework that automates code-compliant reinforced concrete design, ensuring interpretability and verifiability while enabling efficient, accurate, and transparent structural analysis through natural language interaction35. Moreover, researchers have employed text mining and NLP techniques to analyze and standardize unstructured inspection narratives, transforming qualitative comments into structured data that improve the predictive capacity of bridge condition assessment models36. Nevertheless, the potential of NLP for predicting concrete durability remains largely underexplored.

In this study, we constructed a specialized dataset by compiling published investigations, in which the parameters of concrete raw materials are represented numerically, while the freeze-thaw media, test methods, morphological changes, and FTD mechanisms are represented textually. Four multimodal deep learning (MDL) models were developed to predict FTD of concrete, i.e., the evolution in the mass loss rate (MLR) and relative dynamic modulus of elasticity (RDME). These MDL models integrate NLP with deep neural networks (DNN), employing architectures such as long short-term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent units (GRU), LSTM with self-attention (LSTM-SA), and multi-head self-attention (MSA). To achieve the interpretability of the MDL models, A visual method was developed to further reveal how to identify key textual information related to FTD process. It is worth noting that the novelty of the developed MDL models can simultaneously consider the numerical characteristics of concrete raw materials and the key textual information during the FTD process. More importantly, the developed MDL framework exhibits significant scalability, and it can also be applied to predict the durability damage when concrete is subjected to other corrosive environments, such as chloride ingress, sulfate attack, atmospheric carbonation, etc.

Results and discussion

Statistical analysis of dataset

The statistical measures of numerical and categorical features in the dataset are summarized in Table 1, including variable type, unit, minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation (SD). Variables with relatively low standard deviations generally exhibit values clustered around the mean (e.g., C, W/B, NA). In contrast, larger standard deviations indicate a broader spread of values across the distribution.

Figure 1 presents the Pearson correlation matrix for the input and output variables, along with the corresponding significance levels for each feature. The results indicate that the correlation coefficient between NOC and MLR is 0.43, and that between NOC and RDME is -0.46, demonstrating statistically significant correlations between NOC and these output variables. This finding aligns with the general empirical understanding that NOC significantly affects the frost resistance of concrete. Furthermore, all correlations between the input and output variables are below 0.8, suggesting an absence of significant multicollinearity issues. Given the dataset’s complexity, conventional linear regression methods may fail to capture its intricate relationships37. Therefore, the employment of deep learning models is recommended for effective modeling and prediction38.

Implementation process analysis of DNN and MDL models

To demonstrate the critical role of textual information in predicting FTD in concrete, we initially designed a conventional DNN model, whose input layer consists solely of standardized numerical inputs. Building upon this baseline model, we developed a fully automated NLP framework to convert textual information into a format amenable to DNN input. This framework encompasses three stages: tokenization, word embedding, and feature extraction. This method, which integrates word embedding with feature extraction, has become a prevalent approach in modern NLP tasks39. It surpasses traditional techniques, such as the bag-of-words model, by more effectively capturing inter-word relationships, comprehending text sequences, and preserving contextual information40. Notably, the NLP processes for the four distinct text inputs operate independently. In this study, we adopt an early fusion strategy: the 18-dimensional standardized numerical vector is concatenated directly with the 32-dimensional textual feature vector extracted by the NLP module. The resulting fused representation serves as the input to the first hidden layer of the DNN. This direct concatenation not only simplifies the integration process by avoiding additional alignment procedures, but also enables the network to learn joint representations of textual and numerical modalities from the very beginning of training. Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of the MDL model designed and constructed in this study. To clearly distinguish the MDL model from the basic DNN model and simplify model names, all MDL models are named after the feature extraction model used in the NLP framework; for example, LSTM-DNN is abbreviated to LSTM. Detailed descriptions of the NLP framework’s implementation within the MDL model will follow.

In the tokenization phase, all texts in the dataset are split into individual tokens, and unique tokens are counted to construct a vocabulary. Each token is assigned a unique index, with an extra index reserved for padding symbols to facilitate subsequent text processing. Using the constructed vocabulary, all texts are converted into integer vectors. However, variations in text length across samples hinder their combination into a unified tensor shape, potentially reducing training efficiency. To address this, zero-padding was applied to align the text sequences. To minimize unnecessary padding while preserving as much original information as possible, the maximum token count for each of the four text categories was determined post-tokenization and set as the alignment length for that category. Additionally, a masking mechanism was employed to obscure the padding positions, thereby preventing them from interfering with the model’s training process.

However, although tokens have been converted into unique numerical identifiers, these one-dimensional representations cannot capture the complex relationships and semantic nuances between words. Consequently, word embedding techniques are employed. Word embedding maps discrete variables, such as words or phrases, into a continuous vector space. Each token is then assigned a dense vector of fixed dimensions. During model training, these vectors are iteratively optimized to better capture the complex associations and semantic meanings between tokens, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to process and understand text content41. In the word embedding phase, the embedding dimension is a critical hyperparameter. After manual trial and error, the embedding dimension was determined to be 64.

Finally, to effectively capture the key information from the text, we employed four models—LSTM, GRU, LSTM-SA, and MSA—to process the output from the word embedding layer. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of LSTM and GRU in handling sequential data42,43,44. Through manual trial and error, we set the output dimensions of both LSTM and GRU to 32. The self-attention mechanism computes attention weights across all input tokens, thereby quantifying each token’s contribution to the final output, which is particularly beneficial for processing long sequences and preserving global contextual information45. Notably, both the LSTM-SA and MSA models produce second-order tensor outputs, which we subsequently converted into vectors via global max pooling to satisfy the DNN’s input requirements.

Prediction results of DNN and MDL models

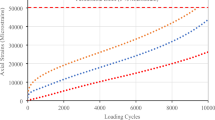

The prediction results of the DNN and MDL models are illustrated in Fig. 3. The absolute mean error on the training and validation datasets in Fig. 3a–e is referred to as the loss and validation loss, respectively. It can be seen that the training process of the MDL models is different from that of the DNN. After 700 epochs of training, the convergence values of the validation loss for the LSTM, GRU, LSTM-SA, and MSA models are all lower than those observed for the DNN model. Because the attention-based models do not rely on such time-step dependencies, the training time of the MSA model is the shortest among these four MDL models (Fig. 3f).

a–e represent the training processes of the simple DNN, LSTM, GRU, LSTM-SA, and MSA models, respectively. f Training time for a single epoch and total training time for different MDL models. g–i represent the Coefficient of determination(R²), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), respectively, for different models in predicting MLR. j–l represent the R², MAE, and RMSE of different models in predicting RDME, respectively. The model performance metrics are the mean values from 5-fold cross-validation.

Figure 3g–l present the average performance metrics of these models on the test set, i.e., coefficient of determination (R²), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). These metrics reflect the models’ prediction accuracy and stability. The results indicate that the four MDL models exhibit significantly higher R² for predicting MLR and RDME compared to the DNN model. This suggests that incorporating textual information describing the freeze-thaw deterioration process of concrete plays an important role in improving the accuracy of FTD predictions. Furthermore, the R² values for the two output variables (i.e., MLR and RDME) in the DNN model show significant differences, whereas the R² values for the MDL models are more consistent. This difference may stem from the distinct physical characteristics of RDME and MLR. RDME is typically influenced by the development of microcracks in concrete and the variation in the pore structure as function of freeze-thaw cycles46,47. In contrast, MLR directly reflects the mass loss of concrete under freeze-thaw cycles at the macro level48. Thus, the RDME prediction is more dependent on the textual data than the MLR prediction since it supplements specific information regarding the microcracks and pore structure in the model.

Figure 4a–e and g–k present the prediction results of various models using parity plots. The results indicate that the prediction performance of the four MDL models exceeds that of the DNN model. In particular, the MSA model enhances the prediction accuracy of MLR and RDME by 8% and 21%, respectively. This improvement is attributed to NLP’s capability to extract and convey key information from textual data, thereby enabling the MDL models to yield more scientifically robust and accurate predictions. Additionally, Fig. 4f, g utilize Taylor diagrams to compare the predictive performance of all models. In the Taylor diagram, polar coordinates centered at the origin represent the standard deviation and correlation coefficient, while polar coordinates centered on the actual data represent the center root mean square error. The results further confirm that the DNN model produces the poorest predictions, while the four MDL models exhibit similar predictive performance, consistent with the conclusions drawn from the parity plots. It is worth noting that the accuracy of concrete FTD predictions is also influenced by sample categories and damage levels.

a−e represent the parity check plots of the MLR prediction results on the test set for the DNN, LSTM, GRU, LSTM-SA, and MSA models, respectively. f Taylor diagram of MLR predictions for different models. g−k represent the parity check plots of the RDME prediction results on the test set for the DNN, LSTM, GRU, LSTM-SA, and MSA models, respectively. l Taylor diagram of RDME predictions for different models.

Figure 5a–f shows the FTD prediction results for samples of different concrete types. The results show that, the DNN model exhibits reduced accuracy for NC samples in MLR predictions compared to FRC and RAC specimens (Fig. 5a–c), while demonstrating particular limitations in RDME predictions for RAC samples (Fig. 5b–f). This phenomenon can be attributed to the presence of multiple baseline groups across various experiments in NC samples, where variations in experimental methods contribute to increased data heterogeneity. Additionally, the unique pore structure of recycled aggregates and the mortar–aggregate interfacial transition zone in RAC samples significantly affect RDME predictions49. Indeed, as these factors are typically conveyed in textual form, the DNN model struggles to capture a consistent FTD pattern. Conversely, the MDL model not only improves prediction accuracy across different sample types, but also effectively mitigates discrepancies in FTD predictions. It is noteworthy that although manually incorporating the fiber category feature into the dataset allowed the DNN model to achieve higher prediction accuracy for FRC samples compared to other sample types, this improvement relied on extensive manual effort. In contrast, the NLP approach integrated into the MDL model proves to be more efficient and cost-effective.

a−c represent the absolute errors, root mean square errors (RMSE), and determination coefficients (R2) for mass loss rate (MLR) prediction in different models on normal concrete (NC), fiber reinforced concrete (FRC), and recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) samples. d−f represent the absolute errors, RMSE, and R2 for RDME prediction in different models on NC, FRC, and RAC samples. g−i represent the absolute errors, RMSE, and R2 for MLR prediction in different models for samples with absolute mass change rates <2.5% and >2.5%. j−l represent the absolute errors, RMSE, and R2 for RDME prediction in different models for samples with RDME <0.8 and >0.8.

Figure 5g–l shows the prediction results of samples with different degrees of FTD. As the severity of FTD in concrete intensifies (manifested as an increase in MLR or a decrease in RDME), the prediction accuracy of the DNN model declines significantly. Particularly for samples with RDME below 0.8, the predictive performance of the DNN model is even inferior to that of simple mean or median prediction methods. A possible explanation is that severely freeze–thaw damaged samples constitute a relatively small fraction of the training dataset, and the degradation mechanism in high-damage states exhibits pronounced nonlinear characteristics, making it challenging for the DNN model to capture the complex evolution of damage effectively. Compared to the DNN model, the MDL model demonstrates superior performance in predicting severely freeze–thaw damaged samples, primarily because pore structure parameters are key determinants of FTD. Moreover, the morphological features in the textual data record the evolution patterns of the structure, and the freeze-thaw mechanism analysis section discusses in detail the influence of mineral admixtures, fibers, and nanomaterials on the pore structure. By integrating multi-source data features, the MDL model gains essential physical insights, thereby enhancing its ability to predict samples with severe FTD.

Visual analysis of MDL models

The above research results indicate that text input plays a universally important role in predicting concrete FTD. However, the internal mechanism by which the MDL model processes textual data remains largely a “black box.” To address this, we propose a visualization method that quantifies the weight of each token within the MDL model, thereby unveiling its internal operations. Given that both LSTM and GRU are sequential models in which each token induces changes in the hidden state (ℎ), we adopt variations in Manhattan distance and cosine similarity between consecutive hidden states as quantitative indicators. A larger value indicates a more drastic change in the hidden state, implying a greater influence of that token on the model’s output. For the LSTM-SA and MSA models, differences in token importance are uncovered by calculating the attention weights assigned to each token.

Figure 6 presents the visualization results of the LSTM model for text processing. The dimensions of the concrete specimen and the term “temperature sensor” are assigned high weights (Fig. 6d), indicating that the model effectively captures key experimental details. “recycled aggregate” and its abbreviation “rca” also exhibit high weights, reflecting the model’s ability to discern category differences between this sample and others. Despite differences in the formatting of key phrases, the model can still identify their similarity and significance. Real-world data often contain non-standardized inputs, and formatting issues may persist even after cleaning50. This fault tolerance greatly enhances the model’s robustness in handling imperfect or noisy text.

a weight heatmap of the experimental method text. b weight heatmap of the morphological description text. c weight heatmap of the freeze-thaw mechanism text. d color-mapped word cloud of the experimental method. e color-mapped word cloud of the morphological description. f color-mapped word cloud of the freeze-thaw mechanism.

Additionally, “c-s-h” and “fine particles” are assigned high weights (Fig. 6e), as both play a crucial role in improving the pore structure of recycled aggregate. The model also emphasizes words such as “slag”, “resistance”, “beneficial”, and “denser” (Fig. 6f), suggesting that it recognizes the positive effect of slag on the freeze–thaw resistance of RAC. It is worth noting that the weight assigned to “fly ash” is significantly lower than that of “slag” (Fig. 6f), and only slag was used in this sample’s mixing ratio. This indicates that, although text and numerical data are processed independently, the model can still identify potential connections between them. As previous studies have shown, RCA tends to accelerate mass loss during freeze–thaw cycling due to its high water absorption and microcrack susceptibility, whereas slag contributes to pore refinement and improved frost resistance51,52. The emphasis of these mechanisms by the MDL model indicates its ability to capture degradation pathways highly relevant to material performance.

Figure 7 presents the visualization results of the MSA model for text processing. The results indicate that the model not only captures microscopic features such as the reduction of internal C-S-H, the decrease in cohesion between mortar and coarse aggregates, and the deterioration of the interfacial transition zone (Fig. 7c) but also identifies the specific impact of waste bricks on concrete FTD from textual data. Specifically, the high attention weights assigned to “waste brick” and “unsuitable” suggest that the model recognizes a potential decline in concrete’s frost resistance due to the presence of waste bricks. Previous studies have shown that the interior of waste brick coarse aggregate (WBCA) is loose and porous, with interconnected capillary pores that promote water ingress and intensify freeze–thaw damage, thereby reducing frost resistance53. Conversely, WBCA also contains closed pores that function like air voids, mitigating ice crystallization and enhancing frost durability54. In particular, the model attends to the term “pre-wetting,” a factor known to reduce the closed-pore content in WBCA and consequently lessen its positive contribution to frost resistance (Fig. 7d). This demonstrates that textual data convey critical information that is difficult to capture through other means; by integrating textual and numerical data, the MDL model facilitates more scientific and precise predictions of concrete FTD. Additional evidence is provided in the supplementary materials.

MDL framework for FTD prediction: contributions, challenges, and future directions

Despite the promising results, several challenges and limitations remain, warranting discussion to contextualize our findings and clarify our contributions. Future work will aim to address these open questions.

The construction of a multimodal dataset that integrates numerical mix-design variables with textual descriptions of freeze–thaw conditions, testing methods, and degradation mechanisms constitutes a key contribution of this study. This integration enables the combined use of structured and unstructured information for durability prediction. However, the dataset remains constrained by limitations in literature collection and data heterogeneity. Restricted access to certain sources and reliance on keyword-based retrieval may have resulted in incomplete coverage of relevant studies, while variations in terminology and reporting standards across publications reduce consistency. Moreover, manual curation of textual information inevitably introduces subjectivity. Future research should adopt more comprehensive literature-mining strategies, such as crawler- or embedding-based retrieval combined with ontology-driven annotation, to broaden coverage and improve reproducibility. Additionally, enriching the dataset with field monitoring data, simulation outputs, multi-scale characterizations, and image-based information (e.g., microstructural or morphological data) would further enhance its representativeness and utility.

We also developed a novel multimodal deep learning framework that integrates numerical parameters with NLP-encoded textual information to predict freeze–thaw damage in concrete. This framework demonstrates the potential of combining heterogeneous data sources to improve both predictive accuracy and interpretability. Nonetheless, the current architecture remains relatively simple, which constrains its ability to capture complex feature interactions, reduces generalizability, and precludes transfer learning. In addition, the visualization methods provide only indirect proxies of the decision-making process and cannot fully reveal the internal reasoning of the models. Future work will therefore focus on strengthening the structural design of the framework, incorporating physics-informed constraints to ensure consistency with established degradation mechanisms, and extending its applicability to other durability challenges such as chloride ingress, sulphate attack, and carbonation.

This study established a comprehensive dataset encompassing concrete mix ratios, freeze–thaw media, experimental methods, morphological descriptions, and freeze–thaw mechanisms. A novel MDL model integrating NLP and DNN was then proposed to predict the MLR and RDME of concrete under freeze-thaw conditions. Visualization method was developed to explain how to effectively identify key information in the text in the MDL model. This innovative framework offers a new solution for predicting the durability damage of concrete exposed to freeze–thaw environments. The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

(1) By integrating fully automated NLP techniques with DNN, this study overcame the limitations of manual text data processing. The textual information, such as freeze-thaw environments, experimental methods, morphological descriptions, and freeze-thaw mechanisms, have been fully utilized. With the incorporation of prior knowledge regarding the FTD process, the MDL models demonstrated a marked improvement in prediction accuracy for samples with severe FTD compared to the conventional DNN model. Among the four MDL models, the MSA model improved prediction accuracy for MLR by 8% and for RDME by 21%.

(2) Visual analyses indicate that the MDL model can effectively capture critical textual information, such as various types of aggregates and the microscopic morphological changes occurring during the freeze–thaw process. Moreover, it reveals a latent relationship between this textual information and the digital inputs, which to some extent elucidates the decision mechanism of the MDL model and offers a novel solution for the scientific prediction of concrete FTD.

Methods

Establishment of the dataset

The dataset used in this study was compiled from 44 peer-reviewed articles published between 2011 and 202422,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97, primarily in leading journals such as Construction and Building Materials and Case Studies in Construction Materials. The inclusion criteria required that each article reported both MLR and RDME under freeze–thaw testing, and provided microscopic morphology images to support mechanistic interpretation. This ensured the consistency and comparability of the dataset. The final dataset consists of 18 numerical variables, four textual variables, and two output variables. The textual data were extracted from relevant sections of the papers, and a typical example of the textual features is presented in Table 2.

In certain contexts, replacing different fiber types with numerical codes rather than applying one-hot encoding may be more efficient, as it avoids the high-dimensional sparsity problem typically encountered when using one-hot encoding for 11 distinct fiber types. To improve scientific rigor and analytical efficiency, the dataset was segmented into five categories based on variations in material composition: normal concrete (NC), fiber-reinforced natural aggregate concrete (FRC), recycled aggregate concrete (RAC), nano-reinforced concrete (NRC), and fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete (FRRAC). Consequently, a new categorical feature column was incorporated into the dataset to represent these groupings. Notably, this column will maintain its original non-numeric format, as it is intended exclusively for use as an identification label in subsequent stratified sampling and other targeted analyses.

Due to the variability in raw material composition among samples, the dataset includes instances of missing data. For instance, the VF feature column in RAC-class samples has missing values. In this study, all missing data are uniformly imputed with zeros. Additionally, some samples lack values for the output variables, indicating that these two critical outputs were not always fully available in the source publications. To ensure data consistency and completeness, samples missing these essential output variables are removed from the dataset. After these adjustments, the dataset comprises 1851 samples.

For the textual data, the initial step is to standardize all text by converting it to lowercase, thereby enabling the model to disregard case differences and accurately recognize words and their synonyms. Subsequently, all punctuation marks, such as commas, colons, and periods, are removed, since they generally do not contribute meaningful information to the model’s understanding.

Deep Neural Network (DNN) and Multimodal deep learning (MDL) models

The DNN model is a type of machine learning model typically composed of a multi-layer architecture in which each layer functions as a nonlinear information processing unit. By simulating the behavior of biological neurons, the model effectively handles complex nonlinear input features and produces accurate predictions of output variables. In this study, we utilized the Keras98 library to construct and train a basic DNN model, along with four MDL models.

In deep learning, a model’s generalization ability is commonly evaluated by partitioning the dataset into a training set and a test set. Parameter optimization is performed on the training set, while the test set is used to assess the model’s generalization capability. We employed the StratifiedShuffleSplit method from the Scikit-learn library to divide the dataset into an 80:20 training-to-test ratio. Notably, stratification was based on manually created concrete category features to ensure that the distribution of different concrete categories in both sets reflected that of the original dataset. Under conditions of limited data, 5-fold cross-validation is critical for stable and reliable model evaluation.

Normalization eliminates the dimensional differences among input variables, thereby accelerating the convergence of machine learning models. In this study, the input variables in the training set were scaled using the following formula:

where Y and X represent the scaled and original data value, respectively; μ is the mean of the original dataset; and σ is the standard deviation of the original dataset. After standardizing the training set, a trained scaler was obtained and subsequently applied to standardize the test set. This approach ensures that the distribution information of the test data is not prematurely exposed during standardization, thereby maintaining fairness and scientific rigor in evaluating the model’s generalization ability.

Selecting appropriate hyperparameter combinations is crucial for constructing a high-performance DNN. In this study, we defined a hyperparameter search space that included the number of hidden layers (three or four), the number of nodes per layer (16, 32, 64, or 128), dropout rate (0.2, 0.3, or 0.4), batch size (64 or 128), number of training epochs (500, 700, or 900), and learning rate (0.01, 0.001, or 0.0005). Although conventional hyperparameter optimization methods—such as grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization—offer certain advantages in specific applications, the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) algorithm has proven more efficient for optimizing large-scale parameter spaces99. Therefore, we employed the TPE method from the Optuna100 library for hyperparameter optimization, with the objective of iteratively minimizing the MAE. The final DNN hyperparameter configuration consisted of three hidden layers with 128, 64, and 32 nodes, a dropout rate of 0.2, the Adam101 optimizer for training, a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 64, and 700 training epochs.

In addition, this study uses MAE, RMSE, and R² as evaluation metrics to assess the prediction accuracy of the DNN model and four MDL models on both the training and testing datasets, in order to prevent underfitting or overfitting. The MAE, RMSE, and R² can be obtained as follows:

where yi represents the true value of the output variable in the dataset, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted value from the model, and \(\bar{y}\) is the mean of the output variable in the dataset.

Visualization method

For both LSTM and GRU architectures, the hidden state h serves as the final output. By quantifying the changes in h induced by each token, we can pinpoint the model’s focus on the text. We measure these variations per word using two metrics. Specifically, the Manhattan distance (MD) captures the cumulative absolute differences across dimensions between consecutive hidden states, reflecting overall activation fluctuations, while the cosine distance (CD) measures changes in the orientation of hidden state h within the semantic space. The formulas for MD and CD are as follows:

where MDj represents the overall absolute change in the hidden state vector at the jth token, and CDj represents the angular difference (direction change) between the hidden state vectors at the jth token and the preceding token. Here, hj denotes the hidden state vector at the j th token, hj-1 denotes the hidden state vector at the (j − 1)th token, hj(i) represents the ith component of the hidden state vector at the jth token, and n is the total number of dimensions in the hidden state vector.

To eliminate scale differences among these metrics, the Manhattan and cosine distance (MD and CD) values are first standardized and then normalized to a fixed range [0,1] to facilitate the generation of a color-mapped word cloud. In this visualization, the sum of the normalized MD and CD—computed separately for the forward and backward directions of the bidirectional LSTM—determines the color mapping, effectively highlighting the tokens that the model focuses on.

Data availability

The curated dataset will be gladly shared with interested researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Detailed descriptions of the model architecture and hyperparameters are also provided in the manuscript.

References

Xiao, J. et al. We use 30 billion tonnes of concrete each year—here’s how to make it sustainable. Nature 638, 888–890 (2025).

York, I. & Europe, I. Concrete needs to lose its colossal carbon footprint. Nature 597, 593–594 (2021).

Scrivener, K., Martirena, F., Bishnoi, S. & Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (LC3). Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 49–56 (2018).

Li, C., Li, J., Ren, Q., Zheng, Q. & Jiang, Z. Durability of concrete coupled with life cycle assessment: review and perspective. Cem. Concr. Compos. 139, 105041 (2023).

Bahafid, S., Hendriks, M., Jacobsen, S. & Geiker, M. Revisiting concrete frost salt scaling: on the role of the frozen salt solution micro-structure. Cem. Concr. Res. 157, 106803 (2022).

Kuosa, H., Ferreira, R., Holt, E., Leivo, M. & Vesikari, E. Effect of coupled deterioration by freeze–thaw, carbonation and chlorides on concrete service life. Cem. Concr. Compos. 47, 32–40 (2014).

Hain, M. & Wriggers, P. Computational homogenization of micro-structural damage due to frost in hardened cement paste. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 44, 233–244 (2008).

Sun, Z. & Scherer, G. W. Measurement and simulation of dendritic growth of ice in cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 40, 1393–1402 (2010).

Rafiei, M. H., Khushefati, W. H., Demirboga, R. & Adeli, H. Neural network, machine learning, and evolutionary approaches for concrete material characterization. ACI Mater. J. 113, 6 (2016).

Peng R-x, Qiu W-l & Teng F. Three-dimensional meso-numerical simulation of heterogeneous concrete under freeze-thaw. Const. Build. Mater. 250, 118573 (2020).

Vu, G. et al. Numerical simulation-based damage identification in concrete. Modelling 2, 19 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Prediction and interpretation of concrete corrosion induced by carbon dioxide using machine learning. Corros. Sci. 233, 112100 (2024).

Deng, Q., Wang, Z., Li, S. & Yu, Q. Salt scaling resistance of pre-cracked ultra-high performance concrete with the coupling of salt freeze-thaw and wet-dry cycles. Cem. Concr. Compos. 146, 105396 (2024).

Zheng, W. & Cai, J. A optimum prediction model of chloride ion diffusion coefficient of machine-made sand concrete based on different machine learning methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134414 (2024).

Liu, K., Zou, C., Zhang, X. & Yan, J. Innovative prediction models for the frost durability of recycled aggregate concrete using soft computing methods. J. Build. Eng. 34, 101822 (2021).

Bayraktar, O. Y. et al. The impact of RCA and fly ash on the mechanical and durability properties of polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete exposed to freeze-thaw cycles and MgSO4 with ANN modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 313, 125508 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Frost durability prediction of rubber concrete based on improved machine learning models. Constr. Build. Mater. 429, 136201 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Prediction of the frost resistance of high-performance concrete based on RF-REF: a hybrid prediction approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 333, 127132 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Analysis and prediction of freeze-thaw resistance of concrete based on machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 108946 (2024).

Gao, X., Yang, J., Zhu, H. & Xu, J. Estimation of rubberized concrete frost resistance using machine learning techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 371, 130778 (2023).

Qiao, L. et al. Interpretable machine learning model for predicting freeze-thaw damage of dune sand and fiber reinforced concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02453 (2023).

Mahbub, R. et al. Text mining for processing conditions of solid-state battery electrolytes. Electrochem. Commun. 121, 106860 (2020).

Zeng, W., Ding, Y., Zhang, Y. & Dehn, F. Effect of steel fiber on the crack permeability evolution and crack surface topography of concrete subjected to freeze-thaw damage. Cem. Concr. Res. 138, 106230 (2020).

Shrestha, A. & Mahmood, A. Review of deep learning algorithms and architectures. IEEE Access 7, 53040–53065 (2019).

Li, Q. et al. A survey on text classification: from traditional to deep learning. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 13, 1–41 (2022).

Panchendrarajan, R. & Zubiaga, A. Synergizing machine learning & symbolic methods: a survey on hybrid approaches to natural language processing. Expert Syst. Appl. 251, 124097 (2024).

Augenstein I. et al. Factuality challenges in the era of large language models and opportunities for fact-checking. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 852–863 (2024).

Pei, Z., Yin, J., Liaw, P. K. & Raabe, D. Toward the design of ultrahigh-entropy alloys via mining six million texts. Nat. Commun. 14, 54 (2023).

Zeng, J., Gensheimer, M. F., Rubin, D. L., Athey, S. & Shachter, R. D. Uncovering interpretable potential confounders in electronic medical records. Nat. Commun. 13, 1014 (2022).

Qiu, P. et al. Towards building multilingual language model for medicine. Nat. Commun. 15, 8384 (2024).

Miller, D., Stern, A. & Burstein, D. Deciphering microbial gene function using natural language processing. Nat. Commun. 13, 5731 (2022).

Özçelik, R., de Ruiter, S., Criscuolo, E. & Grisoni, F. Chemical language modeling with structured state space sequence models. Nat. Commun. 15, 6176 (2024).

Duan, Y. et al. LLM-empowered literature mining for material substitution studies in sustainable concrete. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 221, 108379 (2025).

Mahjoubi, S., Barhemat, R., Meng, W. & Bao, Y. Deep learning from physicochemical information of concrete with an artificial language for property prediction and reaction discovery. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 190, 106870 (2023).

Chen, J. & Bao, Y. Multi-agent large language model framework for code-compliant automated design of reinforced concrete structures. Autom. Constr. 177, 106331 (2025).

Omar, A. & Moselhi, O. Automated data-driven condition assessment method for concrete bridges. Autom. Constr. 167, 105706 (2024).

Roozbeh, M., Babaie-Kafaki, S. & Sadigh, A. N. A heuristic approach to combat multicollinearity in least trimmed squares regression analysis. Appl. Math. Model. 57, 105–120 (2018).

Zhang, X., Sun, J., Zhang, X. & Wang, F. Assessment and regression of carbon emissions from the building and construction sector in China: a provincial study using machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 450, 141903 (2024).

Wang, B., Wang, A., Chen, F., Wang, Y. & Kuo, C.-C. J. Evaluating word embedding models: Methods and experimental results. APSIPA Trans. signal Inf. Process. 8, e19 (2019).

Young, T., Hazarika, D., Poria, S. & Cambria, E. Recent trends in deep learning based natural language processing. ieee Comput. Intell. Mag. 13, 55–75 (2018).

Zhang, C., Tian, Y.-X. & Hu, A.-Y. Utilizing textual data from online reviews for daily tourism demand forecasting: a deep learning approach leveraging word embedding techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 260, 125439 (2024).

Tsai, S.-T., Fields, E., Xu, Y., Kuo, E.-J. & Tiwary, P. Path sampling of recurrent neural networks by incorporating known physics. Nat. Commun. 13, 7231 (2022).

Xia, M., Shao, H., Ma, X. & De Silva, C. W. A stacked GRU-RNN-based approach for predicting renewable energy and electricity load for smart grid operation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 17, 7050–7059 (2021).

Greff, K., Srivastava, R. K., Koutník, J., Steunebrink, B. R. & Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE Trans. neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 28, 2222–2232 (2016).

Li, K. et al. Uniformer: Unifying convolution and self-attention for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 12581–12600 (2023).

Luo, G., Zhao, P., Zhang, Y. & Xie, Z. Performance evaluation of waste crumb rubber/silica fume composite modified pervious concrete in seasonal frozen regions. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1411185 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Mix-proportion design methods and sustainable use evaluation of recycled aggregate concrete used in freeze–thaw environment. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35, 04022401 (2023).

Liu, D., Tu, Y., Sas, G. & Elfgren, L. Freeze-thaw damage evaluation and model creation for concrete exposed to freeze–thaw cycles at early-age. Constr. Build. Mater. 312, 125352 (2021).

Gao, S., Guo, J., Zhu, Y. & Jin, Z. Study on the influence of the properties of interfacial transition zones on the performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133592 (2023).

Chung, S. et al. Comparing natural language processing (NLP) applications in construction and computer science using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA). Autom. Constr. 154, 105020 (2023).

Kazmi, S. M. S. et al. Effect of different aggregate treatment techniques on the freeze-thaw and sulfate resistance of recycled aggregate concrete. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 178, 103126 (2020).

Zhao, R. et al. Freeze-thaw resistance of class F fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 222, 474–483 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. Optimization and utilization of air-entrained recycled brick aggregate concrete under freeze-thaw environment. Case Stud. Construct. Mater. 23, e04941 (2025).

Wang, R., Yu, N. & Li, Y. Methods for improving the microstructure of recycled concrete aggregate: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 242, 118164 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Investigation of the basalt fiber type and content on performances of cement mortar and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133720 (2023).

Nam, J., Kim, G., Lee, B., Hasegawa, R. & Hama, Y. Frost resistance of polyvinyl alcohol fiber and polypropylene fiber reinforced cementitious composites under freeze thaw cycling. Compos. Part B. Eng. 90, 241–250 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Si, Z., Huang, L., Yang, C. & Du, X. Experimental study on the properties of internal cured concrete reinforced with steel fibre. Constr. Build. Mater. 393, 132046 (2023).

Zeng, W., Zhao, X., Zou, B. & Chen, C. Topographical characterization and permeability correlation of steel fiber reinforced concrete surface under freeze-thaw cycles and NaCl solution immersion. J. Build. Eng. 80, 108042 (2023).

Jin, S. J., Li, Z. L., Zhang, J. & Wang, Y. L. Experimental study on the performance of the basalt fiber concrete resistance to freezing and thawing. Appl. Mech. Mater. 584, 1304–1308 (2014).

Fan, X. C., Wu, D. & Chen, H. Experimental research on the freeze-thaw resistance of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 919, 1912–1915 (2014).

Duan, M., Qin, Y., Li, Y. & Zhou, H. Durability and damage model of polyacrylonitrile fiber reinforced concrete under freeze–thaw and erosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 394, 132238 (2023).

Xia, D. et al. Damage characteristics of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete under the freeze-thaw cycles and compound-salt attack. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01814 (2023).

Gong, L., Yu, X., Liang, Y., Gong, X. & Du, Q. Multi-scale deterioration and microstructure of polypropylene fiber concrete by salt freezing. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01762 (2023).

Xiao, D., Guo-Ping, C., Qi, Z., De-liang, D. & Fei-yan, L. An exploration into the frost resistance evaluation indices of airport concrete pavement. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 5, 196 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. Effect of mineral admixture and fiber on the frost resistance of concrete in cold region. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 304, 052085 (2019).

Jiang, L., Niu, D. T. & Bai, M. Experiment study on the frost resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 150, 243–246 (2011).

Meng, C., Li, W., Cai, L., Shi, X. & Jiang, C. Experimental research on durability of high-performance synthetic fibers reinforced concrete: resistance to sulfate attack and freezing-thawing. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120055 (2020).

Wang, T., Xu, J., Meng, B. & Peng, G. Experimental study on the effect of carbon nanofiber content on the durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 250, 118891 (2020).

Wang, T., Xu, J., Bai, E., Lv, Y. & Peng, G. Research on a sustainable concrete synergistic reinforced with carbon fiber and carbon nanofiber: mechanical properties, durability and environmental evaluation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 35366–35386 (2023).

Yuan, S. et al. Research on the frost resistance performance of fully recycled pervious concrete reinforced with fly ash and basalt fiber. J. Build. Eng. 86, 108792 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Bond properties of basalt fiber reinforced polymer (BFRP) bars in recycled aggregate thermal insulation concrete under freeze–thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 329, 127197 (2022).

Yuan, X., Dai, M., Li, M. & Liu, F. Study of the freeze–thaw resistance for composite fiber recycled concrete with sulphate attack exposure. Buildings 13, 1037 (2023).

Zhu, P., Hao, Y., Liu, H., Wang, X. & Gu, L. Durability evaluation of recycled aggregate concrete in a complex environment. J. Clean. Prod. 273, 122569 (2020).

Bogas, J. A., De Brito, J. & Ramos, D. Freeze–thaw resistance of concrete produced with fine recycled concrete aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 115, 294–306 (2016).

Gao, D., Zhang, L., Zhao, J. & You, P. Durability of steel fibre-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 232, 117119 (2020).

Jiang, L., Niu, D., Yuan, L. & Fei, Q. Durability of concrete under sulfate attack exposed to freeze–thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 112, 112–117 (2015).

Liang, N., Miao, Q., Liu, X. & Zhong, Y. Frost-resistance mechanism of multi-scale PFRC based on NMR. Mag. Concr. Res. 71, 710–718 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. The influence of fiber type and length on the cracking resistance, durability and pore structure of face slab concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 282, 122706 (2021).

Hasani, M., Nejad, F. M., Sobhani, J. & Chini, M. Mechanical and durability properties of fiber reinforced concrete overlay: experimental results and numerical simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 268, 121083 (2021).

Tan, Y. & Yu, H. Freeze–thaw durability of air-entrained concrete under various types of salt lake brine exposure. Mag. Concr. Res. 70, 928–937 (2018).

Tavasoli, S., Nili, M. & Serpoush, B. Effect of GGBS on the frost resistance of self-consolidating concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 165, 717–722 (2018).

Xiao, Q. H., Cao, Z. Y., Guan, X., Li, Q. & Liu, X. L. Damage to recycled concrete with different aggregate substitution rates from the coupled action of freeze-thaw cycles and sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 221, 74–83 (2019).

Tarangini, D., Sravana, P. & Rao, P. S. Effect of nano silica on frost resistance of pervious concrete. Mater. Today.: Proc. 51, 2185–2189 (2022).

Wei, D. et al. Potential evaluation of waste recycled aggregate concrete for structural concrete aggregate from freeze-thaw environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 321, 126291 (2022).

Li, G., Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Zhuang, Z. & Lv, Y. Studies of nano-SiO2 and subsequent water curing on enhancing the frost resistance of autoclaved PHC pipe pile concrete. J. Build. Eng. 69, 106209 (2023).

Si, R., Guo, S. & Dai, Q. Durability performance of rubberized mortar and concrete with NaOH-solution treated rubber particles. Constr. Build. Mater. 153, 496–505 (2017).

Wang, J., Dai, Q., Si, R. & Guo, S. Investigation of properties and performances of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber-reinforced rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 193, 631–642 (2018).

Bao, J. et al. Salt-frost scaling resistance characteristics of nano silica-modified recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109674 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Improving the salt frost resistance of recycled aggregate concrete modified by air-entraining agents and nano-silica under sustained compressive loading. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e03170 (2024).

Liu, F., Tang, R., Ma, W. & Yuan, X. Analysis on frost resistance and pore structure of phase change concrete modified by Nano-SiO2 under freeze-thaw cycles. Measurement 230, 114524 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. Normalization techniques in training dnns: Methodology, analysis and application. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 10173–10196 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Synergetic effect of fly ash and ground-granulated blast slag on improving the chloride permeability and freeze–thaw resistance of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 365, 130015 (2023).

Wei, Y., Chen, X., Chai, J. & Qin, Y. Correlation between mechanical properties and pore structure deterioration of recycled concrete under sulfate freeze-thaw cycles: an experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 412, 134794 (2024).

Hu, S. & Yin, Y. Fracture properties of concrete under freeze–thaw cycles and sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 350, 128856 (2022).

Writing-review, H. Z. & Cheng Wei Software, V. Investigation of freeze-thaw mechanism for crumb rubber concrete by the online strain sensor. Measurement 174, 109080 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Effect of silica fume on frost resistance and recyclability potential of recycled aggregate concrete under freeze–thaw environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 134109 (2023).

Xiao, Q., Wu, Z., Qiu, J., Dong, Z. & Shi, S. Capillary water absorption performance and damage constitutive model of recycled concrete under freeze–thaw action. Constr. Build. Mater. 353, 129120 (2022).

Chicho, B. T. & Sallow, A. B. A comprehensive survey of deep learning models based on Keras framework. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2, 49–62 (2021).

Nguyen, H.-P., Liu, J. & Zio, E. A long-term prediction approach based on long short-term memory neural networks with automatic parameter optimization by Tree-structured Parzen Estimator and applied to time-series data of NPP steam generators. Appl. Soft Comput. 89, 106116 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Optuna-DFNN: An optuna framework driven deep fuzzy neural network for predicting sintering performance in big data. Alex. Eng. J. 97, 100–113 (2024).

Khan, A.H., Cao, X., Li, S., Katsikis, VN. & Liao, L. BAS-ADAM: An ADAM based approach to improve the performance of beetle antennae search optimizer. IEEE/CAA J Automat. Sinica. 7, 461−471 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (Grant No. 52222806), Shaanxi Province Science Fund for Distinguished Young youths (Grant No. 2022JC-20), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52341803).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. YFG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing–review & editing. BBG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing-original draft, Writing–review & editing. SHZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing-review & editing. DTN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Guo, B. et al. Multimodal prediction model for concrete freeze-thaw damage based on natural language processing and deep neural network. npj Mater Degrad 10, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00684-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00684-6