Abstract

High-strength pipeline steels are susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement (HE), with inclusions exacerbating this vulnerability. This study employed deoxidation to regulate inclusion/matrix interfacial properties, converting them into functional units that act as deep hydrogen traps and promote acicular ferrite (AF) nucleation. The atomic-scale structure, chemical characteristics, and hydrogen trapping capacity of inclusion/matrix interfaces exhibiting “mosaic” and “core-shell” microstructures were systematically investigated using aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry. Results reveal that both oxygen vacancies in inclusion/matrix interfaces and tensile strain fields in the matrix contribute to hydrogen trapping at incoherent interfaces. The TiO/Fe interface in “core-shell” inclusions exhibits stronger trapping capability than Ti₂O₃/Fe interface in “mosaic” inclusions. These interfaces also enhance AF nucleation and grain refinement, improving HE resistance and synergistic toughening. These findings provide a novel strategy for developing HE-resistant high-strength steels by interface engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen energy plays a crucial role in achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals by driving a revolution in energy production and consumption, thereby facilitating the development of a clean, low-carbon, safe, and efficient energy system1,2,3. Within the entire hydrogen energy chain, which encompasses production, storage, transportation, and utilization, hydrogen storage and transportation have emerged as critical bottlenecks hindering the advancement of hydrogen energy technologies4,5,6. During long-term exposure to hydrogen-containing environments, high-strength steels are prone to increased hydrogen-induced brittleness or reduced toughness, a phenomenon known as hydrogen embrittlement (HE)7,8,9, which can ultimately result in hazardous accidents10,11,12,13.

HE in high-strength steels is closely related to hydrogen permeation, diffusion, and accumulation within the steel matrix14,15,16. The development of HE-resistant steels focuses on introducing microstructural features within the grains that inhibit hydrogen accumulation at grain boundaries or around large inclusions17,18,19. Recently, strategies leveraging intragranular microstructures to mitigate HE have gained increasing attention and validation, including the use of nano carbon/nitride precipitates20,21,22,23, oxygen-enriched nanoclusters24, mixed-metal nanoprecipitates25,26, and local compositional heterogeneity27,28. These approaches primarily exploit the unique structural and chemical characteristics of microstructure-steel matrix interfaces to trap hydrogen or promote the formation of localized soft phases that hinder HE crack propagation.

For nano-scale carbon/nitride precipitates, the hydrogen trapping effect at coherent and semi-coherent interfaces with the steel matrix is primarily governed by vacancies29,30 and the strain field31,32. There has been controversy regarding whether incoherent interfaces can effectively trap hydrogen. Some studies suggest that incoherent precipitates such as TiC, NbC, and VC do not serve as efficient hydrogen traps33,34, while others argue that these precipitates act as deeper hydrogen traps35. Zhang et al. 36 further clarified this debate by proposing that incoherent interfaces can effectively trap hydrogen when carbon or sulfur vacancies induce tensile strain in the adjacent steel matrix; conversely, in the absence of such vacancies and under compressive strain, hydrogen is repelled. Moreover, external tensile strain at the interface may induce carbon vacancies or interstitial atoms, enhancing hydrogen trapping capacity by lowering hydrogen solution energy37,38,39. Therefore, hydrogen trapping behavior at interfaces is closely linked to the presence of vacancies and strain in the matrix, a phenomenon observed not only at nano-precipitate/matrix interfaces but also at larger ferrite/cementite boundaries40,41. It has been confirmed that interfaces with vacancies and without tensile strain on the matrix side can trap hydrogen effectively30; however, whether interfaces lacking vacancies but exhibiting tensile strain on the matrix side also facilitate hydrogen trapping remains unclear.

In addition to the aforementioned strategies for mitigating HE, another class of second-phase particles in steel, spheroidized and dispersed micro- to nano-scale inclusions, can also serve as hydrogen traps to reduce HE susceptibility42,43. Studies have reported that modified inclusions can improve resistance to hydrogen-induced cracking in steels44,45. Our research group has applied oxide metallurgy techniques, including micro-Mg treatment, to functionalize inclusions in X70 pipeline steel, resulting in significant enhancement of HE resistance46,47,48. Similar to precipitates, a critical and challenging question remains: can HE in high-strength steels be mitigated by deliberately designing and controlling the interfacial structure, as well as the chemical and mechanical properties, between inclusions and the steel matrix? To date, no relevant studies have thoroughly addressed this topic.

To address this objective, two APL X70 pipeline steels were fabricated by controlling the degree of deoxidation in molten steel and applying micro-Mg treatment. The steel without Al addition (designated as TM) primarily contained multi-interface “mosaic” inclusions, whereas the steel with 0.0085% Al addition (designated as TMA) predominantly featured dual-interface “core-shell” inclusions. The microstructures of these interfaces were characterized using high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), while hydrogen trapping and diffusion behaviors at the inclusion interfaces were quantitatively analyzed through micro-electrochemical hydrogen permeation, time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS), scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM), and thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS). Furthermore, the effect of oxygen vacancies at the interfaces on hydrogen trapping was investigated via electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) and first-principles calculations. This study clarified the atomic-scale mechanisms underlying the mitigation of HE susceptibility in high-strength steel by controlling the interfacial properties between inclusions and the steel matrix. Additionally, a metallurgical strategy was proposed to synergistically enhance toughness and HE resistance without compromising strength. These findings provide a theoretical foundation and empirical data to guide the design and control of micro-interfaces in inclusions, thereby advancing the development of high-strength, HE-resistant steels.

Results

Microstructure of the two tested steels

The microstructure images and EBSD analysis of the two tested steels are shown in Fig. 1. The microstructures primarily consist of polygonal ferrite (PF), with smaller amounts of AF and granular bainite (GB). Compared to TM steel, TMA steel exhibits a higher proportion of AF, a lower proportion of PF, and finer average grain sizes. The average grain sizes are measured as 2.6 μm for TM steel and 1.9 μm for TMA steel, while the average Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) values are 0.314 and 0.365, respectively. The average KAM values are derived from the frequency distribution diagram (Fig. 1i), with higher values indicating greater dislocation density. Notably, both steels undergo identical rolling processes after casting, differing only in their deoxidation treatments. Therefore, the increased dislocation density observed in TMA steel is likely a result of grain refinement rather than differences in processing.

Preliminary characterization of inclusions in the two tested steels

The macroscopic distribution, typical planar and cross-sectional morphologies, and elemental distributions of inclusions in TM and TMA steels are illustrated in Fig. 2. In both steels, inclusions are predominantly spherical or spheroidal; however, the inclusions in TMA steel are smaller in size compared to those in TM steel. In TM steel, inclusions mainly consist of a Ti-O matrix embedded with Mg-Al-O and Mn-S phases, referred to as “mosaic” inclusions (Fig. 2a). In contrast, inclusions in TMA steel primarily feature a Mg-Al-O core surrounded by a Ti-O shell, termed “core-shell” inclusions (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the interfaces between inclusions and the steel matrix in both steels are predominantly Ti-O/Fe interfaces. Subsequent analyses will therefore focus primarily on these two types of interfaces.

a Macroscopic distribution of inclusions in TM steel. (a1) Planar microscopic morphology and elemental distribution of “mosaic” inclusions in TM steel. (a2) Cross sectional morphology of inclusions in TM steel. (a3) Cross sectional morphology and elemental distribution in (a2). b Macroscopic distribution of inclusions in TMA steel. (b1) Planar microscopic morphology and elemental distribution of “core-shell” inclusions in TMA steel. (b2) Cross sectional morphology of inclusions in TMA steel. (b3) Cross sectional morphology and elemental distribution in (b2).

A quantitative analysis of the composition, size, and quantity of inclusions in TM and TMA steels is conducted (Fig. 3a, b). In TM steel, the proportion of “mosaic” inclusions increases with inclusion size, with inclusions larger than 5 μm predominantly exhibiting the “mosaic” structure. In contrast, in TMA steel, inclusions sized between 1 and 3 μm mainly display a “core-shell” structure, while the number of “core-shell” inclusions larger than 3 μm decreases significantly. These findings suggest that weak deoxidation during smelting promotes the formation of “mosaic” inclusions, whereas strong deoxidation favors the development of “core-shell” inclusions. Additionally, the total number of inclusions in TMA steel exceeds that in TM steel, with almost no inclusions larger than 5 μm observed in TMA steel.

Furthermore, it is well established that micro- and nano-sized particles formed through oxide metallurgical processes effectively promote the nucleation of AF49. To quantitatively evaluate the influence of “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions on AF nucleation, the number and percentage of inclusions facilitating AF nucleation in TM and TMA steels are statistically analyzed (Figure 3c). Figure 4 presents SEM images illustrating AF nucleation induced by the two types of inclusions in the tested steels, along with corresponding EDS mappings of the inclusions. In both steels, the effectiveness of inclusions in inducing AF nucleation (denoted as EAF) is defined by Eq. (1):

where \({N}_{{\rm{AF}}}\) represents the number of inclusions capable of inducing AF nucleation, and \({N}_{{\rm{t}}}\) is the total number of inclusions, both those that can and cannot induce AF. The effectiveness of AF nucleation (EAF) initially increases with inclusion size, then decreases. “Core-shell” inclusions sized 1–3 μm exhibit the highest nucleation capability, while “mosaic” inclusions between 2 and 4 μm are most effective. Moreover, “core-shell” inclusions in TMA steel demonstrate superior AF nucleation effectiveness with an EAF of 49%, compared to 39% for “mosaic” inclusions in TM steel.

Analysis of interfaces between inclusions and steel matrix

The morphology and compositional distribution of FIB specimens from the longitudinal sections of the “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions, along with HAADF-STEM images and their corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns at the two Ti-O/Fe matrix interfaces, are presented in Fig. 5. No microvoids are observed at the interfaces between the Ti-O inclusions and the Fe matrix. FFT analysis identifies the matrix of the “mosaic” inclusions as Ti2O3 (Fig. 5e), whereas the “shell” of the “core-shell” inclusions is determined to be TiO (Fig. 5g). Notably, TiO exhibits a superlattice structure characterized by a 12-fold periodic ordering along the [422] TiO direction. HAADF-STEM imaging further reveals that the two interfaces are either stepped or irregularly curved. Atomic-scale imaging shows a well-defined atomic arrangement on one side of the interface, while the opposite side displays only lattice fringes. Moreover, significant angular misalignment of atomic orientations is observed across the interfaces. These findings indicate that both Ti-O/Fe matrix interfaces are incoherent.

a–c Identify, lift out, and FIB thinning of the inclusion (in the case of TMA specimen). d Morphologies and composition distribution of “mosaic” inclusion. e HAADF-STEM image of Ti2O3/Fe interfaces in ① area of (d). f Morphology and composition distribution of “core-shell” inclusion. g HAADF-STEM image of TiO/Fe interfaces in ② area of (f). h SAED image of Ti2O3/Fe interfaces. i SAED image of TiO/Fe interfaces.

Various zone axes are systematically rotated to further investigate the orientation relationship (OR) between different Ti-O phases and the Fe matrix. Diffraction patterns with unclear lattice points are discarded, and representative composite selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns are selected. The SAED results are presented in Fig. 6h, i. The lattice misfit (δ) and average interfacial energy (\(\bar{\sigma }\)) values are summarized in Table 1, with the specific calculation methods referenced in the literature50. Lattice misfit and average interfacial energy are critical parameters for evaluating the effectiveness of heterogeneous nucleation at an interface51,52. According to literature53, an interface is considered incoherent when the lattice misfit δ exceeds 0.25 and the average interfacial energy \(\bar{\sigma }\) falls between 0.5 J/m2 and 1 J/m2. Similarly, as reported in ref. 54, interfaces with \(\bar{\sigma }\) < 0.32 J/m2 are coherent, those with 0.32 J/m2 < \(\bar{\sigma }\) < 0.60 J/m2 are semi-coherent, and those with 0.60 J/m2 < \(\bar{\sigma }\) < 1.10 J/m2 are incoherent. In this study, the average interfacial energies (\(\bar{\sigma }\)) of the TiO/Fe and Ti2O3/Fe interfaces are determined to be 1.03 J/m2 and 0.63 J/m2, respectively, indicating that both Ti-O/Fe interfaces are incoherent.

The strain state results of Ti-O/Fe matrix interfaces

The strain state of the matrix adjacent to the interfaces is evaluated by directly analyzing atomic column positions in atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM images. Strain distributions across ROIs at the Ti2O3/Fe and TiO/Fe interfaces are quantitatively mapped and presented in Fig. 6. Statistical analysis indicates that near the TiO boundary, the lattice exhibits an average tensile strain of 2.7% along the [101] direction and 1.5% along the [110] direction. In contrast, at the Ti2O3 interface, the lattice shows average tensile strains of 1.3% and 0.8% along the [101] and [110] directions, respectively. Combining these results with the calculated degrees of incoherency for both interfaces, it can be concluded that the magnitude of interface tensile strain is positively correlated with the degree of incoherency.

EELS results of Ti-O/Fe matrix interfaces

The EELS analysis of the Ti L2,3 core-loss edges is conducted both within the interior of inclusions and at their interfaces with the Fe matrix (Fig. 7). For the “mosaic” inclusions, no energy shift is observed when comparing the Ti L2,3 peaks, 459.6 eV for Ti L2 and 464.9 eV for Ti L3, between the Ti2O3 interior and its interface. In contrast, for the “core-shell” inclusions, the Ti L2,3 peaks at the TiO/Fe interface (459.2 eV for Ti L2 and 464.5 eV for Ti L3) shift by approximately 0.3 eV to lower energy relative to the peaks within the TiO interior (459.5 eV for Ti L2 and 464.8 eV for Ti L3). Previous studies55 suggest that such an energy shift indicates a reduction in the Ti valence state. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer the presence of oxygen vacancies on the TiO side of the TiO/Fe interface, whereas the Ti2O3 side of the Ti2O3/Fe interface appears free of oxygen vacancies, potentially related to the superlattice structure of TiO.

DFT calculations of hydrogen solution energy at the Ti-O/α-Fe interfaces

To investigate the aggregation behavior of hydrogen atoms and evaluate hydrogen trapping capacities across different interfacial chemistries, simplified periodic models are constructed for Ti2O3/α-Fe and TiO/α-Fe interfaces without oxygen vacancies, as well as TiO/α-Fe interfaces with oxygen vacancies (Fig. 8). The results indicate that for oxygen vacancy-free interfaces, the hydrogen solution energies (Esol) at three interstitial sites are negative for both Ti2O3/α-Fe (–0.21 ± 0.05 eV) and TiO/α-Fe (–0.39 ± 0.05 eV) interfaces, with the TiO/α-Fe interfaces exhibiting a lower Esol. When an oxygen vacancy is introduced at the TiO/α-Fe interface, the Esol further decreases to -0.51 eV, indicating enhanced hydrogen trapping capacity.

Precipitates in the two tested steels

Precipitates, as common second-phase particles in steel, are also characterized in this study. The macroscopic distribution and quantitative statistics of precipitates in TM and TMA steels are presented in Fig. 9, while their chemical compositions are summarized in Table 2. Precipitates are observed both within grains and along grain boundaries, exhibiting a uniform size distribution ranging from 20 to 100 nm. They predominantly appears as spherical shapes, mainly NbC, as well as ellipsoidal or quasi-ellipsoidal forms, primarily (Nb, Ti)C. The composition and quantity of precipitates are found to be nearly identical in both steels (Fig. 9g).

Results of HE susceptibility and fracture toughness

The stress-strain curves and mechanical properties of the two steels under pure N2 and H2 atmospheres are presented in Fig. 10a and Table 3, respectively. Under a pure N2 environment, the elongation at break (δ0) of both steels is comparable, while TMA steel exhibits higher yield strength and ultimate tensile strength. However, in a pure H2 environment, TM steel shows a significantly greater loss of plasticity, with a HE index (IHE) of 15.9%, which is more than twice that of TMA steel at 6.1%.

Fracture toughness (KIc) and its degradation index (\({I}_{{{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{Ic}}}}\)), measured for both steels, are calculated using Eq. (2) and presented in Fig. 10b.

where \({K}_{{\rm{Ic}}}^{0}\) and \({K}_{{\rm{Ic}}}^{{\rm{H}}}\) represent the fracture toughness of the uncharged and hydrogen-charged specimens, respectively. A larger KIc svalue indicates superior fracture toughness, while a smaller toughness degradation index \({I}_{{{\rm{K}}}_{{\rm{Ic}}}}\) signifies reduced loss of toughness after hydrogen charging. Both steels demonstrate relatively low toughness degradation following hydrogen charging. Compared to TM steel, TMA steel exhibits higher fracture toughness and lower toughness degradation, indicating better resistance to HE.

Macroscopic and microscopic hydrogen permeation results

To evaluate the hydrogen trapping efficiency of individual “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions, inclusions of similar size are selected for microscopic hydrogen permeation testing. FE-SEM images and EDS mappings of the inclusions are presented in Fig. 11. Figure 12 shows the macroscopic and microscopic hydrogen permeation curves for the two types of inclusions and their corresponding steel matrices. The microscopic saturation currents (I∞) are determined as follows: for the “mosaic” inclusion and TM steel matrix, 3.72 × 10–7 ± 1.71 × 10–8 A and 1.78 × 10–8 ± 1.12 × 10–9 A, respectively; and for the “core-shell” inclusion and TMA steel matrix, 1.35 × 10–7 ± 8.49 × 10–9 A and 1.60 × 10–8 ± 1.03 × 10–9 A, respectively. The saturation currents of the matrices are essentially identical, while those of the inclusions are significantly higher, with the “mosaic” inclusion exhibiting a greater I∞ than the “core-shell” inclusion.

The kinetic parameters of hydrogen permeation, derived from the macroscopic hydrogen permeation curves of the two steels, are presented in Table 4. Compared to TM steel, TMA steel exhibits a smaller effective hydrogen diffusion coefficient (Deff) and a longer breakthrough time (tL), indicating a stronger capability to impede hydrogen diffusion. Furthermore, TMA steel shows higher hydrogen diffusion flux (J∞L) and macroscopic saturation current (I∞), corresponding to an increased content of diffusible hydrogen.

TDS results

The TDS curves, activation energy (Ed) fitting curves, and resolved hydrogen contents for TM and TMA steels reveal three distinct hydrogen desorption peaks at different heating rates, corresponding to temperature intervals of approximately 150–300 °C, 350–450 °C, and 450–550 °C, respectively (Fig. 13). The activation energies for the low, medium, and high-temperature peaks are approximately 16.3, 61.2, and 76.4 kJ/mol for TM steel, and 15.9, 62.5, and 115.3 kJ/mol for TMA steel, respectively. While the low- and medium-temperature peaks exhibit similar activation energies in both steels, a significant difference is observed at the high-temperature peak. Typically, low-temperature hydrogen desorption peaks correspond to reversible hydrogen traps such as dislocations, vacancies, and microvoids56,57,58. Activation energies exceeding 60 kJ/mol, as seen in the medium and high-temperature peaks, indicate irreversible hydrogen traps59. In this study, the medium-temperature activation energies align well with reported values for NbC precipitates (63–68 kJ/mol)60, suggesting that these peaks arise from hydrogen trapping at precipitates. The pronounced disparity in high-temperature activation energies between the two steels likely stems from microstructural differences in inclusions, which will be examined in detail later.

a The TDS curves of TM steel at 100 K/h heating rate. (a1 ~ a3) The TDS curves of TM steel at different heating rates from 200 K/h to 400 K/h. b TDS curves of TMA steel at 100 K/h heating rate. (b1 ~ b3) The TDS curves of TMA steel at different heating rates from 200 K/h to 400 K/h. c Ed fitting curves of different desorption peaks of TM steel. d Ed fitting curves of different desorption peaks of TMA steel. e Resolved hydrogen contents of different desorption peaks in TM and TMA steels.

To quantitatively assess the hydrogen content within various traps in the two tested steels, the TDS peak areas are integrated from curves obtained at a heating rate of 100 K/h (Fig. 13a, b), with the results are presented in Fig. 13e. TMA steel exhibits significantly higher hydrogen content than TM steel at both the low- and high-temperature peaks. This increased hydrogen uptake is attributed to TMA steel’s refined grain structure, higher fraction of AF, elevated dislocation density, and greater inclusion density. In addition, the hydrogen content at the medium-temperature peak is comparable for both tested steels and is relatively lower than the contents observed at the low- and high-temperature peaks, indicating a consistent influence of precipitates on hydrogen trapping. Therefore, the subsequent discussion will exclude the effects of precipitates. In other words, the higher total hydrogen content observed in TMA steel can be primarily attributed to its microstructural features and the increased density of inclusions.

Quasi in-situ silver decoration results

To visually observe hydrogen diffusion and trapping processes, a silver decoration experiment is conducted. The EDS mappings illustrating the distribution of silver particles around inclusions in both TM and TMA steels, before and after hydrogen charging, are presented in Fig. 14. After equal hydrogen charging times, silver particles are clearly observed at the interfaces between inclusions and the steel matrix in both steels. Notably, a greater accumulation of silver is found at the TiO/Fe interfaces of the “core-shell” inclusions in TMA steel, indicating that these “core-shell” inclusions possess a stronger hydrogen trapping capability than the “mosaic” inclusions.

TOF-SIMS results

To accurately quantify the hydrogen trapped at different Ti-O/Fe interfaces, TOF-SIMS analyses are performed on the inclusions and their surrounding matrix. Unfortunately, the hydrogen content at the Ti-O/Fe interfaces is too low to be clearly visualized in the 1H distribution mappings. The ROIs of the micro-interfaces are reconstructed and analyzed using TOFWERK software, and the corresponding mass spectra for these ROIs are presented in Fig. 15. The results show that the TiO/Fe interfaces (2.28 ± 0.17) of the “core-shell” inclusions can trap more hydrogen than the Ti2O3/Fe interfaces (1.52 ± 0.08) of the “mosaic” inclusions. These findings are consistent with the results from the TDS tests (Fig. 13e) and the silver decoration experiments (Fig. 14).

In situ SKPFM results

In-situ SKPFM is employed to indirectly assess the hydrogen trapping capability of different interfaces in the two types of inclusions. The variations in Volta potential for the “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions, along with their surrounding steel matrix surfaces, under various hydrogen charging durations are illustrated in Fig. 16. Corresponding FE-SEM images and EDS mappings of the inclusions are provided in Fig. 17. The Volta potential profiles along the indicated arrow directions for both inclusions are extracted before and after hydrogen charging, and the interface potentials were compared relative to the Fe matrix (Fig. 16b, d). The results show that both inclusions exhibit lower potentials than the Fe matrix both before and after hydrogen charging. After 120 min of hydrogen charging, the potentials of both the inclusions and the Fe matrix increase; however, the rise in potential at the TiO/Fe interface of the “core-shell” inclusion is more pronounced than that at the Ti2O3/Fe interface of the “mosaic” inclusion. This indicates that the TiO/Fe interface has a stronger hydrogen trapping capability than the Ti2O3/Fe interface, which is consistent with the SIMS experimental results40,61.

a “mosaic” inclusion morphology of SKPFM scanning and potential mappings before and after hydrogen charging. b Line scanning potential results along the blue arrow in (a). c “core-shell” inclusion morphology of SKPFM scanning and potential mappings before and after hydrogen charging. d Line scanning potential results along the blue arrow in (c).

Discussion

Hydrogen is widely recognized to preferentially accumulate near non-metallic inclusions and/or at their interfaces with the steel matrix62,63,64,65. This study supports that understanding through silver decoration tests, which visually confirm hydrogen enrichment at such sites (Fig. 14). Comparative analysis of hydrogen trapping behavior between “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions reveals several key findings: (1) Both types of inclusions exhibit higher microscopic I∞ values than the surrounding steel matrix (Fig. 12a), indicating that inclusions serve as principal sites for hydrogen trapping, where hydrogen atoms are attracted and retained. Once saturation equilibrium is reached at the inclusion/matrix interfaces, the diffusible hydrogen surrounding these inclusions contributes to an oxidation current detected at the electrode, confirming localized hydrogen enrichment at these interfaces. (2) “Core-shell” inclusions display lower microscopic I∞ values compared to “mosaic” inclusions due to their enhanced capacity for irreversible hydrogen trapping (Fig. 13c, d). This superior trapping efficiency corresponds to a higher saturation threshold for irreversibly bound hydrogen (Fig. 13e and Fig. 15), which consequently reduces the concentration of surrounding diffusible hydrogen and results in a diminished microscopic I∞ response. Furthermore, numerous researchers have attributed the hydrogen trapping capabilities of various interface types primarily to their atomic-scale characteristics, including chemical factors such as atomic vacancies29,30, as well as structural features like misfit dislocations20, lattice strain66, and related properties. In the present study, a comparison between “mosaic” inclusions featuring a Ti2O3/Fe interface, formed under weaker deoxidation conditions in TM steel, and “core-shell” inclusions with a TiO/Fe interface, resulting from stronger deoxidation in TMA steel, reveals that the latter exhibits a significantly stronger hydrogen trapping ability (Figs. 13, 15, and 16). This enhanced performance can be attributed, in part, to the nature of the oxide-metal interface: unlike the high-valence Ti2O3/Fe interface, the low-valence TiO/Fe interface induces greater tensile strain on the adjacent steel matrix due to its higher degree of incoherency, thereby facilitating more effective hydrogen trapping. This phenomenon partially accounts for the more pronounced silver (Ag) aggregation observed at the “core-shell” inclusion/matrix interfaces compared to the “mosaic” inclusions during silver decoration tests; On the other hand, beyond the tensile strain field, the TiO/Fe interface on the side of the “core-shell” inclusions also contains oxygen vacancies; the synergistic effect of these oxygen vacancies (Fig. 7) and the tensile strain (Fig. 6) further enhances the hydrogen trapping capability at TiO/Fe interfaces. First-principles calculations further confirm that oxygen vacancies can lower the hydrogen solution energy at the inclusion/Fe matrix interface (Fig. 8), thereby enhancing its hydrogen trapping capability. Building on this, TDS testing reveals hydrogen desorption energies of 76.4 kJ/mol for TM steel, primarily containing “mosaic” inclusions, and 115.3 kJ/mol for TMA steel, mainly composed of “core-shell” inclusions (Fig. 13). These results align with the observed differences in hydrogen trapping performance, indicating that “core-shell” inclusions provide deeper hydrogen traps compared to their “mosaic” counterpart.

Previous studies have demonstrated that micro- and nano-sized inclusions can act as heterogeneous nucleation sites, promoting the formation of AF in steel49,67. AF is widely recognized as a beneficial microstructure that enhances the toughness of steel68,69. Specifically, titanium oxides have been shown to facilitate AF formation70,71,72, and higher interfacial energy has been found to further promote AF nucleation73. In the present study, as shown in Fig. 18, both “mosaic” and “core-shell” inclusions, regulated by the degree of deoxidation, function as “functional units” that not only facilitate AF nucleation but also serve to trap hydrogen and suppress its accumulation along grain boundaries, thereby reducing the susceptibility of high-strength pipeline steel to HE. Despite the higher dislocation density observed in TMA steel (Fig. 1), its reduced susceptibility to HE is primarily attributed to the superior hydrogen trapping capability of the “core-shell” inclusions. Simultaneously, these “functional units” also contribute to grain refinement by promoting the nucleation of AF (Fig. 3), thereby enhancing the toughness of the steel matrix. Once cracks initiate and begin to propagate within the matrix, diffusible hydrogen can be effectively trapped by the dispersed inclusions, which prevents the crack tip from reaching the critical hydrogen concentration required for sustained propagation, thus mitigating the risk of crack advancement. Additionally, the presence of AF serves to further inhibit crack growth, thereby reducing HE susceptibility and synergistically improving the overall toughness of the high-strength pipeline steel.

In summary, inclusions traditionally considered detrimental to steel performance can be transformed into micro/nanoscale “functional units” by tailoring their interfacial properties, chemical, structural, and mechanical, through micro-Mg treatment and controlled deoxidation processes. On one hand, oxygen vacancies and tensile strain fields at the inclusion/steel matrix interface serve as effective hydrogen trapping sites, functioning as deep traps that significantly enhance the HE resistance of pipeline steels. On the other hand, micro- and nanoscale inclusions can promote the nucleation of AF through interfacial strain, leading to grain refinement and improved toughness of high-strength pipeline steels under high-pressure hydrogen environments. These findings present a novel strategy for developing steels with synergistically enhanced HE resistance and mechanical toughness.

Methods

Materials

The two types of tested steels used in this study were self-produced high-strength pipeline steels, treated with Ti-Mg and deoxidized with 0 wt.% Al (designated as TM steel) and 0.0085 wt.% Al (designated as TMA steel), respectively. Their main chemical compositions and fundamental mechanical properties are presented in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. All the mechanical properties meet the performance requirements of X70 pipeline steel.

Microstructure observation and second phases analysis

The microstructures were examined using an optical microscope (OM, Zeiss Axioplan 2), a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Thermo Fisher Apreo S HiVac), and complementary electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis. Quantitative statistics of inclusions were conducted by analyzing an area of 3 mm2 for both tested steels using FE-SEM, which also facilitated the examination of the relationship between inclusions and acicular ferrite (AF). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) specimens of inclusions were prepared via focused ion beam (FIB) cutting. Inclusion characterization was performed using FE-SEM at 15 kV and a JEOL JEM-ARM200CF microscope operating at 200 kV. Based on HAADF-STEM images, strain values in the matrix at different inclusion interfaces were measured and compared, and strain maps were generated along both the [101] and [110] crystallographic directions. EELS of the inclusion interface and the inclusion itself was performed using a Gatan OneView Camera. For precipitate analysis, TEM foils were prepared via the carbon replica method and examined using a JEM-F200 (CF-HR) microscope operating at 200 kV.

HE susceptibility and fracture toughness evaluation

Slow strain rate tensile (SSRT) tests were conducted to evaluate the HE susceptibility of the two tested steels in a 10 MPa pure H2 environment at a strain rate of 1 × 10⁻6 s⁻1. Tensile specimens with gauge dimensions of 15 mm × φ3 mm were machined in accordance with the ASTM E8/E8M standard74. Prior to testing, the hydrogen pressure was maintained for 24 h, after which the SSRT experiments were performed immediately. The HE susceptibility index (IHE) of the steels was determined based on the degree of ductility loss in pure hydrogen and calculated using Eq. (3)75:

where \({\delta }_{{\rm{N}}}\) and \({\delta }_{{\rm{H}}}\) represent the elongations from SSRT tests conducted in pure nitrogen and pure hydrogen environments, respectively. To ensure experimental accuracy, all SSRT tests were repeated three times.

Fracture toughness tests were conducted in accordance with the ASTM E399-20a standard76 using compact tension (CT) specimens. The pre-cracking procedure was performed at a frequency of 1 Hz with a stress ratio of 0.3, and the pre-crack length was set to 2.54 mm. Displacement control was applied at a rate of 0.01 mm/min, while crack opening displacement was measured to determine the loading displacement. Tests were carried out under both uncharged hydrogen and electrochemically pre-charged hydrogen conditions. The hydrogen charging solution consisted of 0.1 mol/L NaOH and 0.22 g/L CH4N2S, with a current density of 5 mA/cm2 applied for 12 h. The fracture toughness tests were carried out immediately after the pre-charged hydrogen.

Hydrogen permeation tests

The hydrogen permeation tests in this study were conducted at both macroscopic and microscopic levels. Specimens measuring 30 mm × 20 mm × approximately 1 mm were prepared, with both sides sanded and polished. The macroscopic hydrogen permeation tests followed the procedure outlined in ref. 77. Three key kinetic parameters were determined from these tests: the hydrogen diffusion flux (J∞L), the effective hydrogen diffusion coefficient (Deff), and the subsurface hydrogen concentration (c0) at the cathode side.

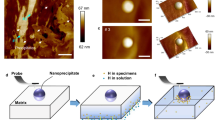

The microscopic hydrogen permeation tests employed a custom-designed device developed by the research group to evaluate hydrogen desorption at individual inclusions. As illustrated in Fig. 19, the setup consisted of two chambers positioned on either side of the specimen. The hydrogen charging chamber on the left contained a mixture of 0.1 mol/L H2SO4 and 0.56 g/L Na4P2O7 (a poisoning agent), while the right side served as the hydrogen detection chamber, featuring a modified capillary three-electrode electrolytic cell78,79. This electrolytic cell was filled with deoxygenated 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution. The capillary port was precisely aligned with pre-marked inclusions on the specimen surface, with a hydrogen charging area of 1 mm2 and a current density of 10 mA/cm2. The oxidation current at the anode was recorded using an electrochemical workstation, generating a current-time curve. The test concluded once the oxidation current stabilized. To ensure data reliability, each test was repeated at least three times under identical conditions.

TDS tests

The activation energy (\({E}_{d}\)) of hydrogen traps was measured using a TDS (HTDS 003, R-DEC) equipped with a quadrupole mass spectrometer (Q-mass Microvision2) at multiple heating rates of 100, 200, 300, and 400 K/h. Cylindrical specimens (φ10 mm × 20 mm) were immersed in a 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution for electrochemical hydrogen charging at a current density of 1 mA/cm2 over a duration of 96 h. Immediately after completing hydrogen charging, the samples were transferred to the TDS for analysis. \({E}_{d}\) was calculated using Eq. (4)30,80:

where \({T}_{p}\) denotes the desorption peak temperature, and \(\varPhi\) is the heating rate (K/h), R is the gas constant, is 8.314 J⋅mol–1⋅K–1.

Quasi in-situ silver decoration tests

The silver decoration tests, based on the redox reaction between hydrogen atoms and Ag⁺ ions, visualized hydrogen pathways through the deposition of silver particles. For detailed experimental procedures, please refer to ref. 81.

TOF-SIMS tests

Depth profiles of inclusions and the surrounding matrix were analyzed using TOF-SIMS with a TESCAN Amber Ga FIB-SEM microscope equipped with a C TOF-SIMS detector. The specimens used had identical dimensions, electrolyte composition, and current density as those employed in the microscopic hydrogen permeation tests, with a charging duration of 4 h. TOF-SIMS analyses were performed immediately following hydrogen charging. A Cobra Ga⁺ ion beam (30 keV, 500 pA) was used to scan an 8 μm × 8 μm area under an operating pressure of 10–9 mbar. Calibration was performed utilizing 1H⁻ and 16O⁻ ions. Hydrogen intensities were quantified by analyzing multiple regions of interest (ROIs) at inclusion interfaces using TOFWERK software.

In situ SKPFM tests

In-situ SKPFM measurements were performed in tapping mode using an atomic force microscope (Bruker Dimension Icon, Germany). The specimens, electrolyte solutions, and current densities were consistent with those used in microscopic hydrogen permeation tests. The Volta potential difference between the specimen surface and the probe tip (SCM-PIT-V2, antimony-doped silicon, tip radius <25 nm, force constant ~3.0 N/m, resonance frequency ~75 kHz) was measured in situ both before and after hydrogen charging, and was defined as:

where \({\varphi }_{{tip}}\) and \({\varphi }_{{specimen}}\) denote the work functions of the tip and specimen, respectively, and e represents the elementary charge82,83. Previous studies have demonstrated that hydrogen lowers the work function of metal surfaces84,85. In this study, the tip’s work function remained constant, while increased hydrogen uptake by the specimen corresponded to a decrease in surface work function and a larger \(\triangle {V}_{{CPD}}\). The SKPFM measurements were conducted in air at 20 ± 0.5 °C with a relative humidity of 38 ± 1%.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The hydrogen solution energy at various Ti-O/matrix interfaces, including the effects of oxygen vacancies, was calculated using DFT following methodologies outlined in the relevant literature86,87. DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP), where valence electron interactions were modeled via the projector augmented-wave method. Electron behavior was described using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. Computational parameters included a plane-wave energy cutoff of 400 eV, Gaussian smearing of 0.1 eV for metallic systems, a self-consistent field convergence criterion of 1 × 10-4 eV per atom, and atomic relaxation until residual forces were below 0.02 eV/Å. The Brillouin zone was sampled using the Monkhorst-Pack method, with a 4 × 4 × 2 k-point grid for the TiO/α-Fe system and a 1 × 4 × 1 k-point grid for the Ti2O3/α-Fe system. The entire system was treated as ferromagnetic, with a vacuum layer thickness of 15 Å. In the interface models, atoms in the surface layers were fully relaxed, while atoms in the remaining layers were fixed.

The solution energy of a hydrogen atom was calculated as follows88:

where \({E}_{{trap}+H}\) and \({E}_{{trap}}\) represent the total energies of the crystal structures with and without hydrogen, respectively, and \({E}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) denotes the total energy of the hydrogen molecule.

Data availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

Code availability

The raw/processed code required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

References

Abe, J. O., Popoola, A. P. I., Ajenifuja, E. & Popoola, O. M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 44, 15072–15086 (2019).

Arsad, A. Z. et al. Hydrogen energy storage integrated hybrid renewable energy systems: a review analysis for future research directions. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 17285–17312 (2022).

Sun, B. H. et al. Current challenges in the utilization of hydrogen energy - a focused review on the issue of hydrogen-induced damage and embrittlement. Adv. Appl. Energy 14, 100168 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. From the perspective of new technology of blending hydrogen into natural gas pipelines transmission: mechanism, experimental study, and suggestions for further work of hydrogen embrittlement in high-strength pipeline steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 8071–8090 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Hydrogen and ethanol: Production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 27330–27348 (2021).

Widera, B. Renewable hydrogen implementations for combined energy storage, transportation and stationary applications. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 16, 100460 (2020).

Ogawa, Y. H., Noguchi, K. & Takakuwa, O. Criteria for hydrogen-assisted crack initiation in Ni-based superalloy 718. Acta Mater. 229, 117789 (2022).

Kim, C. M., Kim, Y. P. & Kim, W. S. Influence of gaseous components and pressures on hydrogen embrittlement of natural gas pipeline. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 31, 3691–3695 (2017).

Meng, B. et al. Hydrogen effects on X80 pipeline steel in high-pressure natural gas/hydrogen mixtures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42, 7404–7412 (2017).

Mohtadi-Bonab, M. A., Szpunar, J. A., Basu, R. & Eskandari, M. The mechanism of failure by hydrogen induced cracking in an acidic environment for API 5 L X70 pipeline steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 40, 1096–1107 (2015).

Asadipoor, M., Pourkamali Anaraki, A., Kadkhodapour, J., Sharifi, S. M. H. & Barnoush, A. Macro-and microscale investigations of hydrogen embrittlement in X70 pipeline steel by in-situ and ex-situ hydrogen charging tensile tests and in-situ electrochemical micro-cantilever bending test. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 772, 138762 (2020).

Singh, V., Singh, R., Arora, K. S. & Mahajan, D. K. Hydrogen induced blister cracking and mechanical failure in X65 pipeline steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 44, 22039–22049 (2019).

Jack, T. A. et al. Investigation of the hydrogen induced cracking behaviour of API 5 L X65 pipeline steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 17671–17684 (2020).

Huang, F. et al. Hydrogen-induced cracking susceptibility and hydrogen trapping efficiency of different microstructure X80 pipeline steel. J. Mater. Sci. 46, 715–722 (2011).

Ohaeri, E., Eduok, U. & Szpunar, J. Relationship between microstructural features in pipeline steel and hydrogen assisted degradation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 96, 496–507 (2019).

Shi, R. J. et al. Quantitative investigation on deep hydrogen trapping in tempered martensitic steel. J. Alloy. Compd. 854, 157218 (2021).

Chu, J. H. et al. Characterization of precipitation, evolution, and growth of MnS inclusions in medium/high manganese steel during solidification process. Mater. Charact. 194, 112367 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Distribution behavior of inclusions in compact-strip-produced martensitic steel and its influence on mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 142, 98–111 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Effect of MnS inclusions on plastic deformation and fracture behavior of the steel matrix at high temperature. Vacuum 174, 109209 (2020).

Shi, R. J. et al. Atomic-scale investigation of deep hydrogen trapping in NbC/α-Fe semi-coherent interfaces. Acta Mater. 200, 686–698 (2020).

Yan, Q., Yan, L. C., Pang, X. L. & Gao, K. W. Hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement in 15-5PH stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 205, 110416 (2022).

Zhang, S. Q. et al. Synergistic effects of Nb and Mo on hydrogen-induced cracking of pipeline steels: a combined experimental and numerical study. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 158, 156–170 (2023).

Zhang, S. Q. et al. Synergistic effects of Ta and Mo on the hydrogen embrittlement resistance in ultra-high strength hot stamping steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 872, 144956 (2023).

Xing, W. W. et al. First-principles studies of hydrogen behavior interacting with oxygen-enriched nanostructured particles in the ODS steels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 18506–18519 (2014).

Masoud, M. et al. Design of high-strength martensitic steels by novel mixed-metal nanoprecipitates for high toughness and suppressed hydrogen embrittlement. Mater. Des. 234, 112323 (2023).

Sun, H. L. et al. Optimizing the hydrogen embrittlement resistance by tuning the structures of Cu-rich nanoprecipitates in high strength martensite stainless steels. Acta Mater. 246, 118722 (2023).

Sun, B. H. et al. Chemical heterogeneity enhances hydrogen resistance in high-strength steels. Nat. Mater. 20, 1629–1634 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Wu, W. J. & Li, J. X. Simultaneous improvement of hydrogen embrittlement resistance and tensile strength of quenching and partitioning steel through dense multiple interfaces. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 58, 1372–1385 (2024).

Ma, Y. et al. A first-principles study on the hydrogen trap characteristics of coherent nano-precipitates in α-Fe. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 27941–27949 (2020).

Takahashi, J., Kawakami, K. & Kobayashi, Y. Origin of hydrogen trapping site in vanadium carbide precipitation strengthening steel. Acta Mater. 153, 193–204 (2018).

Mei, X. Y., Yan, Y. & Qiao, L. J. Research on hydrogen embrittlement behavior of L-PBF 18Ni (300) maraging steel by experiments and numerical simulations. Acta Mater. 256, 119141 (2023).

Zhang, S. Q. et al. The significant effect of tantalum on the hydrogen-induced cracking of pipeline steel: Morphology, hydrogen permeation, and theoretical studies. Corros. Sci. 200, 110213 (2022).

Wei, F. G., Hara, T. & Tsuzaki, K. Nano-preciptates design with hydrogen trapping character in high strength steel. Adv. Steels: Recent Scenario in Steel Sci. Tech. 87-92 (2011).

Wei, F. G. & Tsuzaki, K. Hydrogen absorption of incoherent TiC particles in iron from environment at high temperatures. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 35, 3155–3163 (2004).

Chen, Y. S. et al. Observation of hydrogen trapping at dislocations, grain boundaries, and precipitates. Science 367, 171–175 (2020).

Zhang, B. L. et al. Atomic-scale insights on hydrogen trapping and exclusion at incoherent interfaces of nanoprecipitates in martensitic steels. Nat. Commun. 13, 3858 (2022).

Nematollahi, G. A., Pezold, J. V., Neugebauer, J. & Raabe, D. Thermodynamics of carbon solubility in ferrite and vacancy formation in cementite in strained pearlite. Acta Mater. 61, 1773–1784 (2013).

Guziewski, M., Coleman, S. P. & Weinberger, C. R. Atomistic investigation into interfacial effects on the plastic response and deformation mechanisms of the pearlitic microstructure. Acta Mater. 180, 287–300 (2019).

Yu, S. H. et al. Effects of lamellar structure on tensile properties and resistance to hydrogen embrittlement of pearlitic steel. Acta Mater. 172, 92–101 (2019).

Zhang, B. L. et al. Improving the hydrogen embrittlement resistance by straining the ferrite/cementite interfaces. Acta Mater. 270, 119850 (2024).

Niu, R. L. et al. Hydrogen-enhanced deformation in pearlite. Acta Mater. 281, 120327 (2024).

Peng, Z. X. et al. Comparative study of non-metallic inclusions on the critical size for HIC initiation and its influence on hydrogen trapping. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 12616–12628 (2020).

Peng, Z. X. et al. Improving HIC resistance of pipe-steel by Ti/Mg treatment with insights into hydrogen migration. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 33 (2024).

Cheng, W. S., Song, B. & Mao, J. H. Effect of Ce content on the hydrogen induced cracking of X80 pipeline steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 15303–15316 (2023).

Wang, Y. F., Hu, S. Y., Tian, Z. Q. & Cheng, G. X. Quantitative assessment of the hydrogen induced cracking for 2.25 Cr-1Mo-0.25 V steel under electrochemical charging conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 124, 105343 (2021).

Wen, Q. Y. et al. Improving hydrogen induced cracking resistance of high strength acid-resistant submarine pipeline steels via trace-Mg treatment. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 14808–14821 (2023).

Lang, F. J. et al. Hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement (HE) susceptibility of X70 grade high-strength, acid-resistant, submarine pipeline steel with Mg treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 623–638 (2023).

Hu, R. Z. et al. Unveiling the mechanism behind irregular inclusions triggering no HIC cracks in steels. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 110 (2024).

Liu, F. C. et al. Microstructural refinement by the formation of acicular ferrite on Ti-Mg oxide inclusion in low-carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 824, 141795 (2021).

Wang, Z. J., Zhang, W. N., Li, Y. W., Wang, G. D. & Liu, H. T. Heterogeneous nucleation of M2B-type borides (M=Cr, Fe) attached to TiB2 and Ti (C, N) particles in as-cast high borated steel. Mater. Charact. 169, 110588 (2020).

Takahashi, J., Kawakami, K. & Kawasaki, K. Study on complex precipitation kinetics in Cr- and Cu-added nitriding steels by atom probe tomography. Acta Mater. 169, 88–98 (2019).

Jiang, L. et al. Influence of length-scales on spatial distribution and interfacial characteristics of B4C in a nanostructured Al matrix. Acta Mater. 89, 327–343 (2015).

Porter, D. A., Easterling, K. E. & Easterling, K. E. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys (Revised Reprint) 143-148 (CRC Press, 2009).

Chen, T. et al. Temperature dependent dispersoid stability in ion-irradiated ferritic-martensitic dual-phase oxide-dispersion-strengthened alloy: coherent interfaces vs. incoherent interfaces. Acta Mater. 116, 29–42 (2016).

Cao, N. et al. Doping strain induced bi-Ti3+ pairs for efficient N2 activation and electrocatalytic fixation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2877 (2019).

Metalnikov, P., Eliezer, D. & Ben-Hamu, G. Hydrogen trapping in additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 811, 141050 (2021).

Chen, L., Xiong, X., Tao, X., Su, Y. J. & Qiao, L. J. Effect of dislocation cell walls on hydrogen adsorption, hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement resistance. Corros. Sci. 166, 108428 (2020).

Li, W. G. et al. Enhancement of hydrogen embrittlement resistance in 310S austenitic stainless steel through ribbon-like δ-ferrite. Corros. Sci. 233, 112086 (2024).

Tal-Gutelmacher, E., Eliezer, D. & Abramov, E. Thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS)-application in quantitative study of hydrogen evolution and trapping in crystalline and non-crystalline materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 445, 625–631 (2007).

Wallaert, E., Depover, T., Arafin, M. & Verbeken, K. Thermal desorption spectroscopy evaluation of the hydrogen-trapping capacity of NbC and NbN precipitates. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 45, 2412–2420 (2014).

Rohwerder, M. & Turcu, F. High-resolution Kelvin probe microscopy in corrosion science: scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) versus classical scanning Kelvin probe (SKP). Electrochim. Acta 53, 290–299 (2007).

Jin, T. Y., Liu, Z. Y. & Cheng, Y. F. Effect of non-metallic inclusions on hydrogen-induced cracking of API5L X100 steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 8014–8021 (2010).

Thomas, A. & Szpunar, J. A. Hydrogen diffusion and trapping in X70 pipeline steel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 2390–2404 (2020).

Qin, W. et al. Key factors affecting hydrogen trapping at the inclusions in steels: a combined study using microprint technique and theoretical modeling. Corros. Sci. 200, 110239 (2022).

Luu, W. C. & Wu, J. K. Effects of sulfide inclusion on hydrogen transport in steels. Mater. Lett. 24, 175–179 (1995).

Kawakami, K. & Matsumiya, T. Numerical analysis of hydrogen trap state by TiC and V4C3 in bcc-Fe. ISIJ Int 52, 1693–1697 (2012).

Wang, X., Wu, Z. H., Zhang, N. N., Wang, C. & Yuan, G. An improved toughness process for high-temperature hot-rolled HSLA steel via inclusion-induced acicular ferrite nucleation. Mater. Lett. 360, 135969 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. On the determining role of acicular ferrite in V-N microalloyed steel in increasing strength-toughness combination. Mater. Charact. 118, 446–453 (2016).

Shi, L. et al. Improved toughness and ductility in ferrite/acicular ferrite dual-phase steel through intercritical heat treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 590, 7–15 (2014).

Byun, J. S., Shim, J. H., Cho, Y. W. & Lee, D. N. Non-metallic inclusion and intragranular nucleation of ferrite in Ti-killed C-Mn steel. Acta Mater. 51, 1593–1606 (2003).

Homma, H., Ohkita, S., Matsuda, S. & Yamamoto, K. Improvement of HAZ toughness in HSLA steel by introducing finely dispersed Ti-oxide. Weld. Res. Suppl. 66, 301–305 (1987).

Yamamoto, K., Hasegawa, T. & Takamura, J. Effect of boron on intra-granular ferrite formation in Ti-oxide bearing steels. ISIJ Int 36, 80–86 (1996).

Babu, S. S. The mechanism of acicular ferrite in weld deposits. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 8, 267–278 (2004).

ASTM E8/E8M-21. Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2021).

Zhou, N. et al. Effect of heat treatment on the hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of selective laser melted 18Ni-300 maraging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 885, 145622 (2023).

ASTM E399-20a. Standard Test Method for Linear-Elastic Plane-Strain Fracture Toughness KIc of Metallic Materials. (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2020).

Ge, F. Y. et al. Effect of tensile stress on the hydrogen permeation of MS X65 pipeline steel under sulfide films. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 12419–12431 (2020).

Lu, S. W., Hu, Q., Liu, J. & Huang, F. Parameter optimization for capillary microelectrode preparation. J. Wuhan. Univ. Sci. Technol. 42, 100–105 (2019).

Wang, X. Y., Huang, F., Hu, Q., Zhang, J. W. & Liu, J. Galvanic corrosion behavior of welded joint in marine atmosphere environment based on capillary microcell. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 1 (2024).

Moshtaghi, M., Safyari, M. & Mori, G. Combined thermal desorption spectroscopy, hydrogen visualization, HRTEM and EBSD investigation of a Ni-Fe-Cr alloy: The role of hydrogen trapping behavior in hydrogen-assisted fracture. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 848, 143428 (2022).

Xiao, H. et al. Sequential kinetic analysis of the influences of non-metallic inclusions on hydrogen diffusion and trapping in high-strength pipeline steel with Al-Ti deoxidisation and Mg treatment. Corros. Sci. 195, 110006 (2022).

Melitz, W., Shen, J., Kummel, A. C. & Lee, S. Kelvin probe force microscopy and its application. Surf. Sci. Rep. 66, 1–27 (2011).

Ma, Z. X., Xiong, X. L., Chen, L. & Su, Y. J. Quantitative calibration of the relationship between Volta potential measured by scanning Kelvin probe force microscope (SKPFM) and hydrogen concentration. Electrochim. Acta 366, 137422 (2021).

Evers, S., Senöz, C. & Rohwerder, M. Hydrogen detection in metals: a review and introduction of a Kelvin probe approach. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 14, 014201 (2013).

Jiang, B. L. et al. Combined effects of irradiation and hydrogen on the mechanical and corrosion performances of the ferrite in duplex phase steels. J. Nucl. Mater. 572, 154069 (2022).

Liu, P. et al. Influences of (Al, Ca, Si, Nb, Mn)-oxy-sulfide inclusions on corrosion degradation for newly designed 17-4 martensitic PH steel in simulated geothermal environments. Corros. Sci. 237, 112279 (2024).

Wang, N., Sun, F., Zhou, Q., Liao, D. M. & Yan, Y. W. First-principles study on hydrogen diffusion mechanism of α-Al2O3/Ti2O3 interface. Fusion. Eng. Des. 142, 40–44 (2019).

Stefano, D. D. et al. First-principles investigation of hydrogen interaction with TiC precipitates in α-Fe. Phys. Rev. B. 93, 184108 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U21A20113; 52231003), and Hubei Provincial Central Government Guided Local Science and Technology Development Project (2023CGB004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft; F.H.: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review & editing, Supervision; A.E., S.S., and Q.H.: Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing; L. L. and H.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology; Z.P. and S.Z.: Methodology, Data curation; J.L.: Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision; L.Q.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Huang, F., Elsabbagh, A.M. et al. Interfacial engineering of inclusions for synergistic toughening and hydrogen embrittlement resistance in high-strength pipeline steels. npj Mater Degrad 9, 160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00702-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00702-7