Abstract

The chemical and physical properties of advanced nuclear fuels, particularly in the moderately high temperature regime relevant for fuel storage, remain largely understudied. In this work, we combine in situ high-temperature (high-T) experiments with ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to investigate the behavior of UN under thermally oxidizing conditions. The phase composition and the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) were determined by in situ high-T X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectroscopy. UO2 was identified as the only major intermediate phase, while minor α-U2(N,O)3+x phases detected in the bulk and β-U2N3 on UN surface. A significantly higher CTE was observed under oxidizing conditions (12.3 × 10-6 at 500 K). AIMD simulations, supported by in situ XRD and Raman spectroscopy, attribute this increase to UN lattice distortion, rather than to oxygen diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In pursuit of a safer nuclear fuel cycle, alternative fuel options, including metal alloys, molten salts, and ceramics, are a subject of much interest. While traditional oxide-based fuels currently dominate the market, alternative fuels have the potential to revolutionize existing and emerging reactor technologies1. Uranium mononitride (UN) is one alternative ceramic fuel proposed for a wide range of applications, including fast reactors, tri-structural isotropic (TRISO) fuels, and even a replacement for light water reactor (LWR) fuel2,3,4. Improved thermophysical and neutronic properties make UN a potentially accident-tolerant fuel (ATF)4,5,6,7,8.

Considerable research has been dedicated to the behavior and properties of UN at the extreme conditions reflective of reactor operation (e.g., high temperature and high radiation), but relatively few studies consider how UN behaves at the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle9,10,11,12,13,14. Demonstrating control of UN, or its spent nuclear fuel (SNF) form, under various storage conditions is a critical safety benchmark for fuel qualification. While storage conditions will vary widely, from interim cask to deep geological repository, in general, one can expect conditions that are less extreme than reactor operation but more extreme than ambient, depending on the final fuel burnup and thus the concentration of fission products15,16. In the event of failure of an engineering barrier, exposure to groundwater under reducing or oxidative conditions is possible, studying the response of UN to these conditions is an important starting point towards (dis)qualifying certain storage conditions. Furthermore, given the propensity of UN to oxidize to UO2+x phases at ambient conditions, the most likely strategy for managing UN SNF is through controlled oxidation to more stable oxide forms before its storage or permanent disposal. It is worth noting that UN SNF will likely undergo accelerated degradation due to the altered material properties resulting from fission product buildup. Thus, understanding and controlling this oxidation pathway of UN is critically important for fuel storage considerations, but it represents only the first step towards understanding the behavior of actual UN SNF.

Two topics stand out as particularly important when studying UN behavior under thermally oxidative conditions: (a) phase evolution and (b) thermal expansion, both of which require in situ methods such as high-temperature (high-T) X-ray diffraction (XRD) to be directly studied. The former has important implications for radioisotope aqueous transport, thermally energetic events, and gas evolution under accident conditions or possible geological disposal conditions. The latter will inform canister designs and engineering modeling for the spent fuel assemblies. Acquiring this fundamental knowledge will help address the broader questions on predicting the fuel behaviors during accident scenarios and handling of UN at the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle, including whether it should be directly stored and disposed of or converted to more thermodynamically stable oxide forms or engineered wasteform materials. Understanding UN behavior under these storage-relevant, thermally oxidative’ conditions is therefore a crucial step towards effectively monitoring UN fuel throughout its entire lifecycle, from cradle to grave, although this is only the first step as SNF UN must also be investigated.

Herein, we report the phase evolution and thermal expansion of UN under thermally oxidative conditions from room temperature to 773 K. Using in situ high-T XRD, the phase evolution and lattice distortion of the UN phase were directly probed during oxidation, while in situ Raman spectroscopy was used as a complimentary method to study minor surface species. These in situ techniques enable the reinterpretation and correction of previous ex situ studies. The thermal expansion coefficient of UN under oxidative conditions was determined from the temperature-dependent unit cell parameters, integrated and interpreted by an ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) investigation of oxygen-bearing UN.

Results

In situ high-T XRD

XRD data was refined to extract the relative phase fractions at each temperature step. This analysis showed the main oxidation pathway of UN to be: UN → UΟ2+x → α-U3O8, with the appearance of a minor fluorite-structured phase growing concurrently with UO2+x formation (Fig. 1). Oxidation to UO2+x (fluorite structure, unit cell parameter 5.449(6)Å at 625 K) had an onset of 473 K and completed at ~683 K with full decomposition of UN, beyond which the oxidation to U3O8 occurred. At ~550 K, splitting of the UO2+x peaks (Fig. S3) revealed the presence of a minor phase, which was successfully modeled as a fluorite-structured phase with a smaller unit cell (approx. 5.341(2) Å at 625 K) than UO2+x. The slight discontinuity at 600 K marks where the sample stage had to be adjusted, due to sample movement.

The thermal expansion of the UN phase was tracked until the complete disappearance of the phase at 683 K (Fig. 2). At room temperature, the unit cell parameter a0 was found to be 4.8961(1) Å, higher than the literature value (4.883 Å) by 0.16%, potentially due to the inclusion of carbon and/or oxygen substitutional impurities from the synthesis process17. The unit cell parameter of UN prior to its complete decomposition at 683 K was determined to be 4.9220(19) Å. At higher temperatures, the combination of sample movement (due to Kapton® distortion) and the reduced UN fraction led to higher uncertainties in the refined structural models, as can be seen in Fig. 2.

An empirical correlation between temperature and the unit cell parameter was extracted from the data and described by Eq. 1:

The mean coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) was calculated using the same data. The fractional expansion of the unit cell was plotted as a function of temperature change (Fig. 4b), with L0 = a0 = 4.8961(1) at T0 = 303 K. Equation 2 shows the first-order, temperature-dependent function that was extracted, describing the CTE of UN.

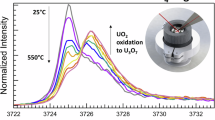

In situ high-T Raman spectroscopy

Figure 3a shows Raman spectra taken of UN powder during heating. There is very little data in the open literature on characterizing UN with Raman spectroscopy, but Lopez-Honorato et al. used DFT to predict that the UN structure will be Raman inactive in its ideal form and demonstrated this experimentally18,19. Indeed, our Raman spectra below 373 K do not show any Raman bands, consistent with Raman inactive pristine UN. Above 373 K, several bands start to develop around 180 cm−1, 330 cm−1, 475 cm−1, and 620 cm−1. The band at 620 cm-1 is often associated with interstitial oxygen clustering in UO2+x, such as U4O920,21. The other three bands are similar to those reported by Lopez-Honorato et al. in trigonal β-U2N3, measured using 633 nm excitation19. Between 373 K and 573 K, carbon D and G bands are observed in the region of 1300–1600 cm−1, indicating carbon impurities in the initial UN sample. These impurities likely come from the carbothermic reduction-nitridation process, where a complex multistep process decarburizes UC to UN and releases free carbon, which decomposes given sufficient time22. No evidence for the presence of UO3 was observed, with no characteristic band at 845 cm−123,24. The polymorphs γ-UO3 and δ-UO3 have also been observed with characteristic peaks at 766 cm−1 and 532 cm−1, both also missing from Raman spectra observed in this study24,25,26.

As the temperature increased, the broad background bands centered at 800 cm−1 and 1050 cm−1 diminished. These initial bands are background due to scattering from within the instrument and are only observed when no other Raman bands are present. Above 498 K, a new band between 700–800 cm−1 began to form, and above 573 K, it began to broaden, resembling the group of bands observed in U3O8. After heating to 1073 K, near full conversion to U3O8 is observed (Fig. 3b). In some cases where changes in the Raman spectra were observed at lower temperatures than in the high-T XRD, it is possible that additional energy from the Raman excitation laser accelerated the oxidation. A map taken at room temperature after heating to 423 K shows regions with no Raman peaks (likely still UN), and regions with peaks characteristic of U3O8 and U4O9 (Fig. S4 and S5).

Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations

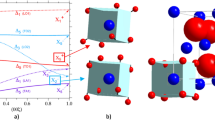

The computed unit cell parameters of pure UN and UN with an oxygen substitutional impurity in a nitrogen vacancy are shown in Fig. 4a. The AIMD calculated unit cell parameters are underestimated (less than 1% deviation) relative to the experimental data gathered during this study and other in situ experiments17,27,28. The tendency of AIMD to underestimate absolute unit cell parameters is well documented but, crucially, this does not affect the accuracy of the relative change in unit cell, which are the relevant value for CTE calculations29. Therefore, the underestimated values were not a concern in this study. The standard deviation of the unit cell parameter systematically increases with temperature due to increased thermal fluctuations. Interestingly, the addition of an oxygen impurity has a negligible effect on the unit cell parameter over the whole temperature range. This is because oxygen fits perfectly in the nitrogen site, due to comparable atomic sizes, leading to no lattice distortion. A similar observation has been made by Kotomin and Mastrikov based on 0 K density functional theory (DFT) calculations30. This agrees with the experimental data compiled by Hayes et al., which show that oxygen and carbon impurities affect UN’s unit cell parameter at room temperature by less than 0.1%17.

a Calculated unit cell parameters of pure UN (red) as well as UN with ON (blue) as calculated from the ab initio molecular dynamics simulations, compared to experimental data (black). The shaded area indicates error bars corresponding to one standard deviation of the time-averaged values. b Projected thermal expansion calculated from experimental and computational data.

Using Eqs. 6 and 7, the first-order, temperature-dependent function was extracted, describing the CTE of UN:

while for UN with an oxygen substitution impurity:

As is obvious in Fig. 4(b), the mean CTE for both computational values are nearly identical with each other and much smaller than the experimental data in this work. It should be emphasized that since a single oxygen defect was described in a supercell consisting of 216 atoms, the atomic concentration of oxygen in this system is 1/216 = 0.46% (i.e. 590 ppm), which is expected to be substantially higher than the equilibrium concentration of ON in UN, around 100 ppm31.

Discussion

The oxidation pathway of UN under air has been studied with varying results, typically including some phase assemblage including UO2, UO3, U3O8, and/or U2N332. The variety of methods, conditions, and samples used make it difficult to draw broad conclusions. Our past study on the thermal oxidation of UN suggested the formation of UO3 as an intermediate oxidation product, while in other studies only UO2 or U3O8 are reported10,11,33,34. U2N3 has been observed in some studies as a surface phase, typically the α polymorph, sandwiched between UN and UO29,33,34,35. Notably, many studies rely on techniques that do not directly probe the phase assemblage during heating. For example, UO3 was hypothesized from a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) study, which used similar thermal oxidation conditions, where such a phase cannot be directly confirmed but rather back calculated33. From this study, we can reject such a hypothesis. This combination of in situ high-T XRD and the past TGA studies suggested that the observation of “UO3” during TGA may be a mass-equivalent UO2-based mixture with the inclusion of nitrogen gas or other X-ray amorphous phases. This was confirmed by the identification of UN, UO2+x, and α-U3O8 at various temperatures with no signs of UO3 (Fig. 5).

The UO2+x peaks correspond to a smaller lattice than expected for UO2 (Table S2). This is likely due to a combination of N dissolution into the UO2 lattice, oxygen non-stoichiometry, and the ingrowth of a minor phase early on. This phase manifested as a subtle broadening of the low-Q UO2+x peaks at low temperatures and a more obvious splitting at higher temperatures. Using XRD alone, it is impossible to conclusively identify this minor phase (Fig. 1a, black; Fig. S3), given the small number of reflections. However, it was successfully modeled as a fluorite-type structure with a unit cell parameter of 5.3369(16) Å at 655 K. Interestingly, this is closer to the reported unit cell parameter of UN2 (5.30266(3) Å at 273 K), another uranium nitride compound albeit one that is not reported to form during the oxidation of UN. However, UN2 has a similar structure to α-U2N3, which could be regarded as a 2 × 2 × 2 UN2 supercell with a quarter of the N atoms removed, and the minor peaks which distinguish their diffraction patterns are often not visible36,37,38,39,40. Limited experimental and computation work has suggested that the two phases exist as a solid solution on the continuum from U2N3+x to UN2-x, subtly evidenced by shifting unit cell parameters41,42,43. Unlike UN2, α-U2N3 is commonly reported to form during the oxidation of UN, thus it is more likely that a phase with stoichiometry of α-U2N3+x is responsible for the unknown reflections in the XRD data. To further complicate the identification of this intermediate phase and help explain the mismatch in unit cell parameters, oxygen dissolution under these experimental conditions is a distinct possibility, and XRD is unable to distinguish between O and N44,45. Several studies of UNx oxidation have identified U-N-O phases as intermediates on the way to UO2, including U(O,N)2+x and U2(N,O)3+x, although their characterization beyond XPS is lacking45,46,47,48. Therefore, we conclude that the phase responsible for these XRD reflections is most likely to be the α-U2(N,O)3+x phase.

We were curious to see if other unexpected species were present at levels too low to be detected by the bulk-sensitive XRD, especially surface species, so we turned to Raman spectroscopy. The three peaks observed at ~180 cm−1, 330 cm−1, and 475 cm−1 are very close to the computed Raman spectra of trigonal β-U2N3, reported by Lopez-Hororato (Fig. 6)19. Interestingly, only β-U2N3 was modeled and identified by Lopez-Hororato, even though there are multiple reasons that α-U2N3 is far more commonly cited as a decomposition product of UN, and without a reference for the Raman spectra of α-U2N3, we cannot definitively rule out its presence on the surface. First, β-U2N3 is considered a high-temperature phase, not predicted to appear at low temperatures where UN oxidation is often occurring, although these phase boundaries are poorly understod49,50. In addition, the α-U2N3 crystal structure shares an underlying array of face-centered cubic U atoms with UN and UO2 (in contrast with the α-Mn2O3 type body-centered cubic structure of β-U2N3), allowing it to grow epitaxially on the surface forming a layer between the two, as has been observed in single-crystal experiments9,35,51. For these reasons, we would expect to see α-U2N3 on the surface of UN during oxidation and not β-U2N3, similar to what other in situ studies of UN oxidation have seen9,10. However, the dissolution of oxygen into this phase is again a possibility, but little research has been done to illuminate the effect this might have on structure and temperature of formation. Additionally, Tagawa and Masaki reported the slightly different stoichiometries of the two phases, with β-U2N3 transforming to α-U2N3 above a 1.75 N/U ratio, meaning β-U2N3 is the nitrogen-poor polymorph43,52. Given that the Raman data shows this phase appearing at lower temperatures than the α-U2N3+x phase identified via XRD (373 vs 544 K), it is possible that under these early experimental conditions, the N/U ratio at the surface favors the β-U2N3 polymorph as significant decomposition and release of N has not taken place yet.

There were two additional peaks observed at ~620 cm−1 and ~466 cm−1 in the same locations where the three β-U2N3 peaks were observed, suggesting multiple phases are present. Stoichiometric UO2 has a Raman peak at 445 cm−1 that shifts to higher wavenumbers with increasing O/U ratio up to UO2.34 (U4O9), accompanied by the formation of a band at 620–640 cm−1 due to oxygen defect clustering. The presence of these bands alongside the β-U2N3 bands supports the idea of UN/U2N3 /UO2+x layers forming on the surface (Fig. 6). Between 373 K and 573 K, a group of broad bands in the range 1300–1600 cm−1 is observed (Fig. 3). The bands are centered around ~1360 cm−1 and 1600 cm−1 and can be assigned to the D and G bands of carbon. The presence of carbon bands may indicate that some initial carbon (either free or substitutional) was present in the UN before it burned off upon heating. This is consistent with literature reports of a slightly increased UN unit cell parameter when carbon impurities are present, matching our slightly elevated unit cell parameter, and the possibility of free carbon remaining from the synthesis pathway17,22.

While the observation of two different phases by XRD and Raman spectroscopy might seem contradictory, when taken together they paint a picture of the overall phase evolution of UN during thermal oxidation. Equation 5 describes this pathway:

The first phase to appear is the N-poor β-U2N3 polymorph, beginning at 373 K when there is limited free N around from the decomposition of UN. Whether occurring in trace amounts as a surface phase or manifesting as a local distortion without long range order is not clear, hence its designation in brackets, but either way the phase is not apparent in the XRD. At slightly higher temperatures (544 K) an α-U2N3 structured phase emerges, identified by XRD as α-U2(N,O)3+x. It is difficult to determine whether this phase arises from the trigonal β-U2N3 or forms independently, as little information is available on the phase transition between the two. However, it is possible that β-U2N3-type distortion evolves into cubic α-U2(N,O)3+x, particularly as the stoichiometry shifts to favor the N-rich polymorph. These uncertainties highlight gaps in our understanding of UN decomposition phases, particularly during different N and O partial pressures, and will hopefully stimulate more research on the topic to further clarify this important pathway.

The thermal expansion of a material, defined as a change in volume in response to temperature, can be measured (1) using dilatometry, which measures the overall expansion of a bulk material in length, or (2) diffraction which tracks the unit cell expansion53. Given the evolving phase composition of the samples herein, only the latter is suitable for calculating the CTE of UN during thermal oxidation. Existing data on the thermal expansion of UN is sparse and in many cases decades old, with diffraction data even rarer10,17,28,54,55. We have summarized available data in Fig. 7 and Table 1 below. Although there are discrepancies in the unit cell parameters of UN at room temperature from various reports, the thermal expansion coefficients (indicated by the slope of curves in Fig. 7) are similar, even at extremely high temperatures. Most studies choose to focus on the high temperatures that are relevant to reactor operating conditions and accident scenarios. A closer look at the lower temperature regime reveals a discrepancy in thermal expansion between this work and existing data sets.

To further investigate this anomaly, the CTE for each data set was calculated from diffraction data using Eqs. 6 and 7. The reported uncertainty is from the regression fitting, as the error in diffractometry data was not reported in many cases and is insignificant in comparison. In addition, dilatometry data for UN thermal expansion have been compiled, as it is somewhat more abundant in the literature. While dilatometry does not provide unit cell parameters, it generates a CTE that can be compared directly with that calculated from diffraction data. Table 1 summarizes the directly obtained CTE from dilatometry and the calculated CTE from diffraction.

The CTE calculated from the diffraction measurements in this work is notably higher than prior literature data, across techniques and samples, while the computational data is much closer to previously measured CTE values. While a systematic error in measurement cannot be ruled out, as the primary Kapton containment distorted during heating, the sample-to-detector distance was refined when major shifts occurred and did not vary systematically (Table S1), so it is unlikely to account for this anomalously high CTE. The existence of high C impurities was also considered as a possible explanation, given that C substitutions do impact the starting unit cell parameters and some physical properties22,56. However, C impurities ranging from thousands of ppm (Kempter and Elliot, 1959) to 200 ppm (Liu et al. 2023) are reported for other UN studies, yet yield the same CTE, so this was also discarded as a hypothesis10,55. To further confirm this, using the same AIMD methodology we calculated the lattice expansion for a UN supercell with C substitutional impurities, and saw no impact on the CTE (Fig. S6). A closer inspection of the diffraction data sets reveals an alternative explanation—the atmosphere during heating. All previous studies, focusing on high temperatures, used inert atmospheres during thermal expansion to prevent the total oxidation of UN. In contrast, the current work is the only diffraction study performed under an oxidizing atmosphere. While this is limiting in the sense that CTE could only be studied at lower temperatures, it has raised the question of whether the thermal expansion of UN is fundamentally different under oxidizing atmospheres. Understanding when and why this anomalous expansion is taking place could be a critical input for meso-scale modeling of nuclear fuels during realistic, multi-phase scenarios. For example, platforms such as BISON use material property inputs, including thermal expansion, to predict nuclear fuel performance under various reactor configurations and conditions57,58,59. Refining these inputs to account for the anomalous expansion will improve predictions of UN behavior, provided its occurrence can be clearly defined and understood. This phenomenon could be due to O diffusion into the UN lattice or from the impact of the decomposition phases which emerge during thermal oxidation, neither of which occurs under inert atmospheres.

AIMD was used to investigate the first hypothesis, by comparing the thermal expansion of pure UN and oxygen-substituted UN. While some thermodynamic modeling suggests that oxygen dissolution into UN under equilibrium conditions is relatively low, the presence of carbon impurities could significantly increase oxygen solubility60. Previous computational work has shown that O impurities in UN, both interstitial and substitutional, are energetically favorable and that interstitial substitutions significantly expand the surrounding lattice and accelerate defect migration30,61,62. However, Kotomin and Mastrikov found that the energy difference between oxygen incorporation in nitrogen vacancies (ON) and interstitial sites (Oi) is approximately 3.46 eV. This significant energy difference means that the concentration ratio of [Oi]/[ON] is extremely small, especially at the relatively low temperatures relevant to the current study, implying that oxygen predominantly occupies nitrogen vacancies30. Our AIMD thus focused on substitutional oxygen impurities but found nearly identical thermal expansion for pure UN and oxygen-substituted UN, indicating that the distinct UN thermal expansion behavior observed experimentally in this work is not attributable to the presence of substitutional oxygen impurities in their own right (Fig. 4).

An alternative explanation is that the act of decomposition, i.e. the ingrowth of U2(N,O)3+x phases or the off-gassing of N, is responsible for the elevated CTE. Both α-U2N3 and β-U2N3 were detected by in situ high-T XRD and Raman spectroscopy, in the bulk and on the surface of the thermally oxidizing UN sample. The impact of physically mixed phases such as this on the microscale properties, including CTE, has been studied extensively in the context of ceramic composites. Of particular relevance, a mismatch between the CTE of the two phases in a physical mixture can also induce stress during heating and impact the CTE63,64. Zhao et al. demonstrated that CTE mismatch of Al and Y2Mo3O12 in 55–64 vol% composites resulted in distortion to the Y2Mo3O12 lattice, due to compressive and tensile strains which evolved over the temperature gradient65. While data on the thermal expansion of UN decomposition products is rare, using data from Silva et al., it is possible to estimate a rough CTE of α-U2N3, which is much higher than that of UN (results in Table 1)39. This large CTE mismatch may influence the thermophysical properties of the bulk UN with the induced stress translating to elevated lattice swelling over the temperature range, but a more detailed understanding of the high-temperature properties of UN2-x phases, and their interaction with UN, is necessary to definitively draw this conclusion.

Alternatively, structural defects like vacancies and interstitials, have been shown to affect the unit cell parameter of phases, with Manzier et al. showing a linear correlation between defect concentration and lattice swelling in CdTe materials66,67,68. N off-gassing during thermal oxidation of UN could cause lattice swelling in a similar way, as it accumulates in small amounts interstitially or creates vacancies. It is also possible that a combination of N vacancies and increasing temperature are causing a distortion from the cubic rock-salt-type UN structure to a lower symmetry phase, prior to full decomposition to the α-U2(N,O)3+x phase. This hypothesis is bolstered by the detection of β-U2N3 during this experiment, a non-cubic, non fcc uranium nitride phase detected at lower temperatures than the α-U2(N,O)3+x phase. Its appearance demonstrates the possibility of lower-symmetry phases or distortions occurring early on during the thermal oxidation of UN, perhaps due to interstitial O or N at the correct partial pressures, which could be responsible for the anomalous thermal expansion detected here. Anisotropic distortion in rock salt structures is well studied, and can be intentionally induced by the introduction of defects or cation mixing69,70. A decrease in symmetry, for example to a tetragonal phase (I4/mmm, chosen for simplicity) as shown in Fig. 8, can be detected by a change in peak shape or the emergence of minor reflections71. Indeed, a subtle shift in the slope of the peak positions was detected at around 500 K (Fig. S7), indicating a possible distortion from the Fm-3m symmetry to the lower symmetry I4/mmm phase. A slightly distorted, tetragonal UN unit cell was fit to this data, with a similar goodness of fit (Fig. 8, Table S4), as one example of a possible lowered symmetry phase. It was noted that the molar volume of the tetragonal phase was consistently lower than that of the cubic phase. This indicates that at higher temperatures, if this distortion emerged but the phase was considered with an incorrect higher symmetry, it could lead to the systematic overestimation of the thermal expansion, leading to the seemingly anomalous CTE of UN particularly above 500 K. Future experiments controlling the oxygen partial pressure or using techniques more sensitive to the position of O and N atoms, could shed light on this potential distortion and if it is related to the early appearance of the β-U2N3 phase.

Methods

In situ high-temperature X-ray diffraction

The UN sample synthesis has been described previously in the literature, and the same feedstock material and synthesis were used for this study33. The carbothermic reduction and subsequent nitridation result in slight oxygen and carbon impurities in the lattice. Based on correlations in the literature between lattice parameter and carbon impurities, we can estimate approximately 1000 ppm of C in the UN lattice17. Samples were ground in an N2-atmosphere glovebox (0.3 ppm > O2 and 0.01 ppm > H2O atmosphere) with a mortar and pestle for XRD analysis. Given the radiological hazard presented by U, all manipulations were carried out in a monitored radiation laboratory. Approximately 10 mg of sample was pressed between two pieces of Kapton® (polyimide) tape, which was subsequently cut into thin strips, stacked, and placed into a 2 mm outer-diameter (wall thickness of 0.2 mm) quartz capillary. Quartz wool was loosely packed on either end of the capillary to allow contact with the open atmosphere during the experiment but constrain the sample in the center of the containment. Still, under anoxic conditions, the sample-loaded quartz tube was sealed in Mylar® (polyester) bags for transport to the synchrotron facility. The sample was only exposed to air for approximately 10 min prior to data collection, to minimize oxidation prior to measurement. In situ high-T XRD was collected at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) Brockhouse XRD High Energy Wiggler Beamline, using 60 keV incident X-rays with a 60-second exposure time.

The sample was heated from 273 to 773 K with a step of 10 K and a 15-second thermal hold at each temperature step prior to a 60-second diffraction exposure. The furnace thermocouple was in direct contact with the primary Kapton layer. A powdered Ni sample was used a temperature calibrant, using the same outer 2 mm quartz capillary, furnace, and temperature profile as the experimental sample, but without the Kapton layer, finding an average temperature deviation of 3.7 K (Fig. S1)72. Due to the thermal distortion of Kapton® at high temperatures ( > 575 K), the sample moved positions during the experiment and the sample stage position had to be adjusted. These adjustments took approximately one minute to complete and did not interrupt the heating. Temperature points 424 ~ 454 K and 706 ~ 726 K were discarded due to significant sample movement. Upon reaching 773 K, the sample was held isothermally for 15 min with XRD patterns collected every minute, and then the sample was cooled to room temperature with the same temperature step and scanning conditions.

Calculations of the coefficient of thermal expansion

The unit cell parameters were used to calculate the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of the UN phase during thermal expansion. The GSAS-II software package was used to refine the XRD data and extract unit cell parameters and crystalline phase fractions at each temperature step73. Thus, even as the UN decomposes and the material becomes polyphasic, the CTE is still calculated for only the UN phase. Using these unit cell parameters, the mean coefficient of thermal expansion (αm) for UN was obtained using Eq. 6

where L is the unit cell parameter at temperature T, and L0 is the unit cell parameter at T0 (300 K). The data was then fit to a 2nd-order polynomial with an intercept at 0 (Equations S1-S2), and the temperature-dependent CTE was extracted and described by Eq. 7:

The data was fit using OriginPro74. We chose to calculate the mean CTE rather than the instantaneous CTE to more easily compare across different techniques, as it is more widely used53,75.

In situ high-temperature Raman spectroscopy

Raman data was collected with a Thermo Scientific DXR2xi Raman confocal microscope (Thermo Scientific, USA) using a 455 nm laser for excitation. The spectral range was 50–3500 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The laser was focused through a 50× objective. Power was adjusted to 3–6 mW and the exposure time was 0.2-1 s. At least 60 scans at each time point were averaged. High temperature spectra were collected using a Linkam TS1500 heating stage (Linkam Scientific, UK), ramping to the target temperature at 50 K/min up to 1073 K, under a 5 mL/min flow of air. Raman spectra were collected after heating had been paused for at least 10 min, as refocusing the Raman laser was necessary after heating. A temperature calibration up to 673 K was performed using Si standards, and found temperatures were within 16 K (Fig. S2)76,77. The quicker ramp rate was utilized due to the added time necessary to refocus and collect data at each temperature.

Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations

The AIMD calculations conducted in this study are carried out using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), employing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA) for the exchange-correlation functional78,79,80,81. Projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials are used for uranium, nitrogen, and oxygen82. The valence electron configuration for uranium includes 6s2 6p6 6d2 5f2 7s2 (14 electrons), while nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon have valence configurations of 2s2 2p3 (5 electrons), 2s2 2p4 (6 electrons), and 2s2 2p2 (4 electrons) respectively. To handle partial occupancies, the first-order smearing method of Methfessel and Paxton is applied with a smearing width of 0.1 eV83.

Ferromagnetic UN is modeled using 3 × 3 × 3 supercells (216 atoms) with and without an oxygen and carbon impurities in a nitrogen vacancy (i.e., ON and CN according to the Kröger-Vink notation) to study the impact of oxygen and carbon on the thermal expansion of UN. Kocevski et al. demonstrated that this ferromagnetic ordering is an appropriate model for UN at 0 K as well as at finite temperatures27,28. Kotomin and Mastrikov have shown that ON is the most energetically favorable oxygen defect in bulk UN, and is, thus, expected to be the most prevalent30. It is expected that the same is true for carbon. The plane-wave cutoff energy was set to 520 eV, and the energy convergence criterion for electronic optimization was set to 10−4 eV. Brillouin-zone integrations are performed at the Γ point. The supercells have been equilibrated within the NPT ensemble at zero pressure and temperatures of 300, 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 K for 7 ps, where the lattice constant has been averaged over the last 5 ps.

Data availability

Data for this article, including 2D diffraction data are available at GitHub, at GitHub - GuoGroupWSU/uranium_mononitride_degradation.

References

Andersson, D. A., Stanek, C. R., Matthews, C. & Uberuaga, B. P. The Past, Present, and Future of Nuclear Fuel. MRS Bull. 48, 1154–1162 (2023).

Fletcher, J. F. & Greenborg, J. Nitride fuels for fast breeder reactors: fuel cycle considerations.; BNWL-606; Battelle Pacific Northwest Labs., Richland, WA (United States), 1968. https://doi.org/10.2172/4543207.

Terrani, K. A., Jolly, B. C. & Harp, J. M. Uranium Nitride Tristructural-Isotropic Fuel Particle. J. Nucl. Mater. 531, 152034 (2020).

Streit, M. & Ingold, F. Nitrides as a Nuclear Fuel Option. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25, 2687–2692 (2005).

Speidel, E. O., Keller, D. L. Fabrication and properties of hot-pressed uranium mononitride; BMI-1633, EURAEC-706, 4674236; 1963; p BMI-1633, EURAEC-706, 4674236.

Szpunar, B., Ranasinghe, J. I., Malakkal, L. & Szpunar, J. A. First Principles Investigation of Thermal Transport of Uranium Mononitride. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 146, 109636 (2020).

Mishchenko, Y., Patnaik, S., Wallenius, J. & Adorno Lopes, D. Thermophysical Properties and Oxidation Behaviour of the U0.8Zr0.2N Solid Solution. Nucl. Mater. Energy 35, 101459 (2023).

Mishchenko, Y., Patnaik, S., Charatsidou, E., Wallenius, J. & Lopes, D. A. Potential Accident Tolerant Fuel Candidate: Investigation of Physical Properties of the Ternary Phase U2CrN3. J. Nucl. Mater. 568, 153851 (2022).

He, L. et al. Phase and Defect Evolution in Uranium-Nitrogen-Oxygen System under Irradiation. Acta Materialia 208, 116778 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Thermal Expansion and Steam Oxidation of Uranium Mononitride Analysed via in Situ Neutron Diffraction. J. Nucl. Mater. 575, 154215 (2023).

Sooby, E. S. et al. Steam Oxidation of Uranium Mononitride in Pure and Reducing Steam Atmospheres to 1200 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 560, 153487 (2022).

OSAWA, Y. Oxidation and Gas Release Behavior of UC, U(C,N) and UN at High Temperature. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 6, 182–193 (1969).

Antill, J. E. & Myatt, B. L. Kinetics of the Oxidation of UN and U(CO) in Carbon Dioxide, Steam and Water at Elevated Temperatures. Corros. Sci. 6, 17–23 (1966).

Rizk, J. T. et al. Mechanistic Nuclear Fuel Performance Modeling of Uranium Nitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 155604 (2025).

American Nuclear Society Special Committee on Generic Standards for Disposal of High-Level Radioactive Waste. Recommendations on Postclosure Aspects of Generic Standards for the Permanenet Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel and High-Level and Transuranic Radioactive Wastes in the United States, (2023).

Ewing, R. C. Long-Term Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel. Nat. Mater. 14, 252–257 (2015).

Hayes, S. L., Thomas, J. K. & Peddicord, K. L. Material Property Correlations for Uranium Mononitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 171, 262–270 (1990).

Carvajal Nunez, U. Synthesis and Characterization of Advanced Nuclear Fuels. 2014. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:b8586668-eee8-43b2-9da8-88596d3f2079.

Lopez-Honorato, E. et al. Raman Spectroscopy of Uranium Nitride Kernels. J. Nucl. Mater. 595, 155050 (2024).

Desgranges, L., Baldinozzi, G., Simon, P., Guimbretière, G. & Canizares, A. Raman Spectrum of U4 O9: A New Interpretation of Damage Lines in UO2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 455–458 (2012).

Elorrieta, J. M., Milena-Pérez, A., Vigier, J.-F., Bonales, L. J. & Rodríguez-Villagra, N. New Insights into the Structural Transition from UO2+x to U3O7 by Quantitative Raman Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 28394–28402 (2022).

MUROMURA, T. & TAGAWA, H. Synthesis of High Purity Uranium Mononitride from Oxide through Carbide. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 17, 57–66 (1980).

Palacios, M. L. & Taylor, S. H. Characterization of Uranium Oxides Using in Situ Micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Appl Spectrosc. 54, 1372–1378 (2000).

Pointurier, F. & Marie, O. Use of Micro-Raman Spectrometry Coupled with Scanning Electron Microscopy to Determine the Chemical Form of Uranium Compounds in Micrometer-Size Particles. J. Raman Spectrosc. 44, 1753–1759 (2013).

Sweet, L. E., Henager, C. H., Hu, S., Johnson, T. PNNL-20951: Investigation of Uranium Polymorphs, 2011. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3073.0004.

Spano, T. L., Shields, A. E., Niedziela, J. L., Miskowiec, A. Unexpected Features in the Optical Vibrational Spectra of δ-UO3. Front. Nucl. Eng. 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnuen.2022.995292.

Kocevski, V., Rehn, D. A., Cooper, M. W. D. & Andersson, D. A. First-Principles Investigation of Uranium Mononitride (UN): Effect of Magnetic Ordering, Spin-Orbit Interactions and Exchange Correlation Functional. J. Nucl. Mater. 559, 153401 (2022).

Kocevski, V. et al. Finite Temperature Properties of Uranium Mononitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 576, 154241 (2023).

Tsuru, Y., Shimazu, M., Shiono, M. & Morinaga, M. Evaluation of Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Perovskite Oxides Using Ab-Initio Molecular Dynamics with Small Cell Sizes for Materials Design. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 49, 045701 (2010).

Kotomin, E. A. & Mastrikov, Y. A. First Principles Modeling of Oxygen Impurities in UN Nuclear Fuels. J. Nucl. Mater. 337, 492–495 (2008).

Muta, H., Kurosaki, K., Uno, M. & Yamanaka, S. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Uranium Nitride Prepared by SPS Technique. J. Mater. Sci. 43, 6429–6434 (2008).

Watkins, J. K., Gonzales, A., Wagner, A. R., Sooby, E. S. & Jaques, B. J. Challenges and Opportunities to Alloyed and Composite Fuel Architectures to Mitigate High Uranium Density Fuel Oxidation: Uranium Mononitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 553, 153048 (2021).

Goncharov, V. G. et al. Energetics of Oxidation and Formation of Uranium Mononitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 569, 153904 (2022).

Watkins, J. K., Butt, D. P. & Jaques, B. J. Microstructural Degradation of UN and UN-UO2 Composites in Hydrothermal Oxidation Conditions. J. Nucl. Mater. 518, 30–40 (2019).

Sole, M. J. & Van Der Walt, C. M. Oxidation and Deformation Studies of Uranium Nitride by Electron Microscopy. Acta Metall. 16, 501–510 (1968).

AbdulHameed, M., Beeler, B., Galvin, C. O. T. & Cooper, M. W. D. Assessment of Uranium Nitride Interatomic Potentials. J. Nucl. Mater. 600, 155247 (2024).

Silva, G. W. C. et al. Microscopic Characterization of Uranium Nitrides Synthesized by Oxidative Ammonolysis of Uranium Tetrafluoride. Chem. Mater. 20, 3076–3084 (2008).

Ma, L., Silva, C., Yeamans, C., Cerefice, G., Czerwinski, K. Microscopic and Spectroscopic Characterization of the Uranium Dinitride (UN2) Synthesized Using a Low Temperature Fluoride Route. MAM 2007, 13.

Silva, G. W. C. et al. Reaction Sequence and Kinetics of Uranium Nitride Decomposition. Inorg. Chem. 48, 10635–10642 (2009).

Dell, R. M., Wheeler, V. J. & Bridger, N. J. Hydrolysis of Uranium Mononitride. Trans. Faraday Soc. 63, 1286–1294 (1967).

Long, Z. et al. UN2−x Layer Formed on Uranium Metal by Glow Plasma Nitriding. J. Alloy. Compd. 620, 289–293 (2015).

Obodo, K. O. & Braun, M. Nitrogen Non-Stoichiometric Stabilization of UN2. Solid State Commun. 254, 21–25 (2017).

Yeamans, C. B. Synthesis of Uranium Fluorides from Uranium Dioxide with Ammonium Bifluoride and Ammonolysis of Uranium Fluorides to Uranium Nitrides. Doctor of Philosophy, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, (2008).

Sood, D. D., Agarwal, R. & Venugopal, V. Phase Diagram Calculations of the U Pu N System with Carbon and Oxygen Impurities. J. Nucl. Mater. 247, 293–300 (1997).

Henry, J. L. & Blickensderfer, R. The Quaternary System U-C-0-N at 1700 C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 52, 534–539 (1969).

Zhong, H. et al. The Microstructure and Oxidation Behavior of the N-Doped Modified Layers on Uranium Surface Prepared by Pulsed Laser Irradiating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 501, 144229 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. In Situ Electronic Structure Analysis of Water-Corroded UNx in High Vacuum. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 199, 239–252 (2025).

Sugihara, S. & Imoto, S. Hydrolysis of Uranium Nitrides. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 6, 237–242 (1969).

Hiroaki, T. Phase Relations and Thermodynamic Properties of the Uranium-Nitrogen System. J. Nucl. Mater. 51, 78–89 (1974).

Benz, R. & Bowman, M. G. Some Phase Equilibria in the Uranium-Nitrogen System1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88, 264–268 (1966).

Dell, R. M., Wheeler, V. J. & McIver, E. J. Oxidation of Uranium Mononitride and Uranium Monocarbide. Trans. Faraday Soc. 62, 3591–3606 (1966).

Tagawa, H. & Masaki, N. X-Ray and Density Studies of Nonstoichiometric Uranium Sesquinitride. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 36, 1099–1103 (1974).

ASTM E228-22. Standard Test Method for Linear Thermal Expansion of Solid Materials with a Push-Rod Dilatometer, 2023. https://compass.astm.org/document/?contentCode=ASTM%7CE0228-22%7Cen-US&proxycl=https%3A%2F%2Fsecure.astm.org&fromLogin=true.

Benz, R., Balog, G. & Baca, B. H. High. Temp. Sci. 15, 221 (1970).

Kempter, C. P. & Elliott, R. O. Thermal Expansion of 〈UN〉, 〈UO2〉, 〈UO2·ThO2〉, and 〈ThO2. J. Chem. Phys. 30, 1524–1526 (1959).

Di, Y., He, Z. & Wang, J. New Insights into the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of UN1-xCx from First-Principles Calculations. J. Nucl. Mater. 571, 153991 (2022).

Williamson, R. L. et al. BISON: A Flexible Code for Advanced Simulation of the Performance of Multiple Nuclear Fuel Forms. Nuclear Technology 2021, 207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2020.1836940.

Cunningham, K. Modeling UO2 and Un Fuel Fission Gas Release Instances in Bison for Microreactor Applications. M.S., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States -- Massachusetts, 2024. https://www.proquest.com/docview/3171635812/abstract/A387BADEEF424619PQ/1 (accessed 2025-09-23).

Perez, D. M. et al. An Evaluation of the Nuclear Fuel Performance Code BISON.

Lyubimov, D. Y. U., Androsov, A. V., Bulatov, G. S. & Gedgovd, K. N. Thermodynamic Modeling of Oxygen Dissolution in Uranium Mononitride at 900–1400 K. Radiochemistry 56, 496–500 (2014).

Kotomin, E. A., Mastrikov, Y. A., Rashkeev, S. N. & Van Uffelen, P. Implementing First Principles Calculations of Defect Migration in a Fuel Performance Code for UN Simulations. J. Nucl. Mater. 393, 292–299 (2009).

Bocharov, D., Gryaznov, D., Zhukovskii, Y. F. & Kotomin, E. A. Ab Initio Simulations of Oxygen Interaction with Surfaces and Interfaces in Uranium Mononitride. J. Nucl. Mater. 435, 102–106 (2013).

André, D., Levraut, B., Tessier-Doyen, N. & Huger, M. A Discrete Element Thermo-Mechanical Modelling of Diffuse Damage Induced by Thermal Expansion Mismatch of Two-Phase Materials. Computer Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 318, 898–916 (2017).

Hsueh, C.-H. & Becher, P. F. Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Unidirectional Fiber-Reinforced Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 71, C438–C441 (1988).

Zhou, C. et al. Thermal Mismatch Strain Induced Disorder of Y 2 Mo 3 O 12 and Its Effect on Thermal Expansion of Y 2 Mo 3 O 12 /Al Composites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 11778–11785 (2017).

Mainzer, N. et al. Influence of Structural Defects on Lattice Parameter and Measured Composition of Hg1−xCdxTe Epilayers. J. Cryst. Growth 197, 542–546 (1999).

Wang, K. & Reeber, R. R. The Role of Defects on Thermophysical Properties: Thermal Expansion of V, Nb, Ta, Mo and W. Mater. Sci. Eng.: R: Rep. 23, 101–137 (1998).

Chen, N., Wang, Y., He, H. & Lin, L. Effects of Point Defects on Lattice Parameters of Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 54, 8516–8521 (1996).

Wang, Y. et al. Unraveling the Nature and Role of Layered Cation Ordering in Cation-Disordered Rock-Salt Cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19838–19848 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Structural Evolution in Disordered Rock Salt Cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 24296–24309 (2024).

Berardan, D., Meena, A. K., Franger, S., Herrero, C. & Dragoe, N. Controlled Jahn-Teller Distortion in (MgCoNiCuZn)O-Based High Entropy Oxides. J. Alloy. Compd. 704, 693–700 (2017).

Thermophysical Properties of Matter- the TPRC Data Series; Touloukian, Y. S., Ho, C. Y., Eds.; Thermal Expansion Metallic Elements and Alloys; Defense Technical Information Center, 1975; Vol. 12.

Toby, B. H. & Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS-II: The Genesis of a Modern Open-Source All Purpose Crystallography Software Package. J Appl Cryst 2013, 46, 544–549.

Origin(Pro), Version 2024. OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA.

Standard Test Method for Linear Thermal Expansion of Solid Materials by Thermomechanical Analysis.

Cui, J. B., Amtmann, K., Ristein, J. & Ley, L. Noncontact Temperature Measurements of Diamond by Raman Scattering Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 83, 7929–7933 (1998).

Sugawa, S., Yokogawa, R., Arai, Y., Yonenaga, I. & Ogura, A. Temperature Dependence of Raman Peak Shift in Single-Crystalline Si-Rich Sige. Meet. Abstr. MA2022-02, 1238 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics for Liquid Metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of Ab-Initio Total Energy Calculations for Metals and Semiconductors Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Computational Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient Iterative Schemes for Ab Initio Total-Energy Calculations Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-Precision Sampling for Brillouin-Zone Integration in Metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Frye, J. H. & Cunningham, J. E. ORNL-3670: Metals and Ceramics Division Annual Progress Report for Period Ending June 30, (1964).

Taylor, K. M. & McMurtry, C. H. Synthesis and Fabrication of Refractory Uranium Compounds, Summary Report- May 1959 through December 1960. Atomic Energy Comission 1961, ORO-400.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research (RES) under award No. 31310023M0011. NSY and ECK acknowledge the support under a University Nuclear Leadership Program Graduate Fellowship, award number DE-NE0009089. Research presented in this article was also supported by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program via projects 20180007DR and 20220053DR at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). LANL, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is managed by Triad National Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract number 89233218CNA000001. This work is also partially funded by Westinghouse Electric Company. This research made use of the resources of the High-Performance Computing Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under Contract No. DE-AC07-05ID14517. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Graham King for his assistance and expertise at the Brockhouse XRD High Energy Wiggler Beamline, at the Canadian Light Source, a national research facility of the University of Saskatchewan, which is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Government of Saskatchewan, and the University of Saskatchewan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Y.: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft; S.K.: investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; M.A.: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; E.C.K.: methodology; A.vV.: investigation, resources, writing—review and editing; M.D.W.: investigation, writing—review and editing; B.M.: investigation; H.X.: investigation, writing—review and editing; J.T.W.: resources, writing—review and editing; B.B.: investigation, resources, writing—review and editing; J.M.C.: funding acquisition, resources, writing—review and editing; X.G.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing (CRediT – Contributor Role Taxonomy).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaw, N.S., Karcher, S., AbdulHameed, M. et al. Thermal expansion and degradation of uranium mononitride under high-temperature oxidative conditions. npj Mater Degrad 9, 165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00708-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00708-1