Abstract

Graphite under high temperatures and irradiation is central to advanced reactors. We develop a Bayesian calibration framework for graphite property models that explicitly represents model-data mismatch via a Gaussian-process discrepancy. The approach propagates uncertainty from parameters, experimental noise, and model form, with a hierarchical variance structure to capture group and cross-group noise. Using two predictive models across five grades (IG-110, NBG-18, PCEA, NBG-17, 2114) and four properties-irradiation-induced dimension change, creep, Young’s modulus change ratio, and coefficient of thermal expansion change ratio-we obtain average predictive-error reductions of 54%, 65%, 17%, and 17% when discrepancy is included. We illustrate engineering impact with a multiphysics model of a very-high-temperature reactor prismatic reflector brick, analyzing stresses under high fluence and temperature. Accounting for model discrepancy markedly improves predictive accuracy and provides a robust basis for reliable graphite component design in advanced reactors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphite is a key material used in the cores of some currently operating nuclear reactors as well as multiple advanced nuclear reactor types currently being developed, including very-high-temperature reactors (VHTRs), thermal molten-salt reactors, fluoride-salt-cooled high-temperature reactors, and multiple types of microreactors1,2,3,4,5. As such, for safe and reliable reactor operation, it is important to ensure that graphite components can perform their intended functions under long-term exposure to the reactor environment. Due to their location in the reactor core, these components are subjected to high temperatures and high irradiation, often with large spatial gradients in one or both of these quantities. Both temperature and irradiation can cause significant volumetric changes, which can induce elevated stresses if they are nonuniform or if the component is mechanically constrained. Irradiation-induced creep also affects mechanical deformation and can relieve the stresses caused by nonuniform volumetric change. Excessive deformation of the components could interfere with proper coolant flow or the reactor controls6. In addition, this deformation can lead to stresses high enough for fracture, which could also adversely impact reactor operation in similar ways7.

Accurate mathematical models for key graphite thermal and mechanical properties are essential for the finite-element simulations that provide the foundation for component design assessments. Graphite structural components for modern nuclear reactors are constructed of synthetic graphite, which exists in a variety of grades produced by different manufacturers, each having unique characteristics, including grain size and sources of the constituents. The thermal and mechanical properties can vary significantly between graphite grades, and any model for those properties must have a basis in experimental observations. The U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Reactor Technologies graphite research and development program is a major source of such data. It has gathered significant data through its baseline testing of unirradiated graphite and its Advanced Graphite Creep (AGC) testing of irradiated graphite8 in the Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) at Idaho National Laboratory (INL). Additional data are also available from Campbell et al.9, who performed irradiations in the flux trap of the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and evaluated the changes in a predetermined set of physical, mechanical, and thermal properties. Also, the INNOGRAPH experiments have generated data on the irradiation behavior of graphite grades for high-temperature gas reactor applications10. Data from these three sources were used for the work discussed herein.

Multiple calibration efforts have been made in the past to predict graphite properties under high irradiation and temperature conditions11,12,13,14. However, there is a significant scatter in the graphite property data, and any calibration effort needs to quantify the uncertainties in both the model and its parameters as well as the data. A Bayesian approach provides a probabilistic treatment for calibration and enables the quantification of uncertainties stemming from various sources, such as the model parameters, experimental noise, and model discrepancy15. Specifically, model discrepancy, which results from both inadequate model forms and biases in the experimental data, is an important component of the calibration. Following the work of Kennedy and O’Hagan (KOH)16, we accounted for model discrepancy in our Bayesian calibration via a Gaussian process (GP). Correcting for model discrepancy during the calibration can have significant impacts on the component simulation of graphite moderator blocks using the finite-element method. Additionally, data from multiple experimental campaigns are available, each having their own inherent noise level since they targeted different neutron fluence conditions. A hierarchical structure for the variance modeling is essential to capture the noise within a data group (i.e. the data from one experimental campaign) as well as the cross-group noise in the data.

The novel contributions of this effort to graphite property prediction and modeling are threefold: we (1) calibrated—while quantifying all sources of uncertainties—graphite property models considering alternative model forms, four properties, five grades, and three data sources; (2) used a GP model discrepancy term to quantify and correct for biases between the model predictions and experimental data and demonstrated substantially improved predictive performance; and (3) investigated the impact of property prediction at the material level on component performance at the engineering level, especially when accounting for model discrepancy17. We considered data from three campaigns (AGC8, Campbell et al.9, INNOGRAPH10) for four properties (irradiation-induced dimension change [IIDC], creep, Young’s modulus [E] change ratio, coefficient of thermal expansion [CTE] change ratio) and five grades (IG-110, NBG-18, PCEA, NBG-17, 2114) using two models (individually fitted models for the separate properties and the Bradford unified physics-based model18). A full Bayesian analysis with model discrepancy and a hierarchical variance structure was used for calibration. A full Bayesian analysis is described as inferring the model parameters, the GP discrepancy term hyperparameters, and the hierarchical variance structure parameters simultaneously. This is achieved using the no-u-turn sampler (NUTS)19, a variant of the gradient-based Markov chain Monte Carlo, owing to the complexity of posterior distribution. To demonstrate the impact of the model discrepancy term, a multiphysics model of a representative VHTR prismatic core reflector brick is considered, and the stresses resulting from high neutron fluences and temperatures are analyzed.

Results

Material property calibration

We fit graphite property data from three sources: AGC8, Campbell et al.9, and INNOGRAPH10. Four properties are of interest: IIDC, creep, E change, and CTE change. Five graphite grades are of interest: Toyo Tanso IG-110, SGL Carbon NBG-18, SGL Carbon NBG-1720, GrafTech International PCEA, and Mersen 2114. We considered two types of predictive models for these properties: individually fitted and the Bradford et al.18 unified model. We fit these models using two approaches: standard Bayesian and the KOH Bayesian, which explicitly considers model discrepancy as a GP. Additionally, we considered a hierarchical variance structure for the residual because there are multiple data sources with different inherent noise levels in the data. The calibration was performed using a full Bayesian approach, wherein the posterior distribution of the model parameters, GP discrepancy term hyperparameters, and hierarchical variance structure parameters are all jointly inferred. More details on the experimental data sources, predictive models, and calibration approaches are presented in the Methods section. Due to the large number of combinations of graphite grades and properties, detailed results are only presented for the NBG-18 grade and the IIDC property, particularly to show the impacts of the GP model discrepancy term and the hierarchical variance structure. The results for the other grades and properties are summarized in Fig. 4.

Figure 1a, b show the model parameter samples and their correlations from the posterior distribution using the individually fitted and Bradford unified models, respectively. Each figure includes a comparison of the standard Bayesian (i.e., does not consider the GP discrepancy term) and KOH Bayesian (i.e., considers the GP discrepancy term) results. Both standard and KOH Bayesian frameworks result in similar, if not the same, model parameter distributions. However, there are some differences related to the issue of lack of identifiability that occurs when models are calibrated. As discussed in Arendt et al.21, given the nonuniqueness of calibration, lack of identifiability stems from both the model parameters and the GP discrepancy term being adjustable to match the experimental observations. This non-uniqueness makes it difficult to identify the true values of the model parameters during calibration. Given that the impact of identifiability in Fig. 1a, b is small and that this issue is an active area of research22,23,24, addressing the identifiability issue is out of scope of the present work.

a Individually fitted model and (b) Bradford unified physics-based model18. The comparison of the standard Bayesian (blue) and KOH Bayesian (red) results reveals the presence of minor identifiability issues with the calibration process.

The standard deviation of the residual after accounting for the model prediction in the standard Bayesian approach is denoted by σ. The standard deviation of the residual after accounting for the model prediction and GP discrepancy term in the KOH Bayesian approach is denoted by σε. Given that for the NBG-18 grade there are two datasets, namely AGC and INNOGRAPH, there will be two group-level variances and an average variance μσ across the groups. Figure 2a, b present the variance posterior distributions using the individually fitted and Bradford unified physics-based models, respectively. For both the models, σε obtained from the KOH approach is less on average than σ obtained from the standard Bayesian approach for the AGC and INNOGRAPH data. This trend is attributed to the GP model discrepancy term capturing the discrepancy between the model predictions and the experimental data. The magnitude of reduction depends upon both the level of discrepancy between model and experiments as well as the inherent noise in the data. The posterior distribution for μσ is much more diffuse compared to the group-level variance posteriors. This is expected since the μσ posterior encompasses the group-level variances.

Sigma posterior distributions using the (a) individually fitted and (b) Bradford unified physics-based models for predicting IIDC with the NBG-18 grade. The σ posterior was obtained using the standard Bayesian approach and captures the uncertainty due to model discrepancy and experimental noise. In contrast, σε posterior was obtained using the KOH Bayesian approach and supposedly captures the uncertainty due to experimental noise only, as it accounts for the model discrepancy via a GP term. It is therefore intuitive that σε is on average less than σ. Additionally, in each figure there are two σ and σε posteriors corresponding to the two experimental datasets from AGC8 and INNOGRAPH10. The μσ is the variance posterior across both the experimental groups and, therefore, is more diffuse than the group-level variance posteriors.

The predictive performance of the standard Bayesian and KOH Bayesian calibration approaches are shown for IIDC of NBG-18 and IG-110 graphite in Fig. 3. Model predictions at 1150K for NBG-18 (Fig. 3a, b) and 1000K for IG-110 (Fig. 3c, d) are plotted as a function of the fluence, along with experimental data for approximately that temperature. For both models, without the GP discrepancy term the standard Bayesian approach is unable to capture key features in the data. First, at low fluence levels (<0.5 × 1026 n0 m−2), the calibrated models fail to properly account for the negative IIDC values observed in the data. Second, the data demonstrate a turnaround behavior, wherein the initially negative IIDC begins to increase with increasing fluence, and eventually becomes positive at what is termed the crossover point. While the standard Bayesian calibration captures the increasing IIDC values with fluence, it fails to capture the turnaround behavior previously observed in many studies8,9,10, especially for NBG-18 grade at 1150K. In contrast, including the GP discrepancy term through the KOH approach results in both better predictions of IIDC at low fluence values and a distinctive turnaround behavior with the fluence. Additionally, this figure shows the GP discrepancy term by itself along with its predictive entropy, which represents epistemic uncertainty. Low predictive entropy implies low epistemic uncertainty regarding the GP discrepancy term and vice versa. Intuitively, there are regions along the fluence axis where data are associated with low predictive entropy, as shown by the darker regions on the GP discrepancy term. In regions of low data, the GP discrepancy term will have high predictive entropy, and in such regions, the model will contribute the most to the overall prediction.

IIDC predictions made by the (a, c) individually fitted and (b, d) Bradford unified physics-based18 models as a function of fluence for a temperature of 1150K for the NBG-18 grade and 1000K for the IG-110 grade. Results for the standard Bayesian and KOH Bayesian approaches are shown. Including the GP discrepancy term (or GP inadequacy term) via the KOH approach substantially improves the predictive performance compared to the experimental data, especially in terms of capturing the distinctive turnaround behavior. The GP discrepancy term by itself along with the associated predictive entropy (i.e., epistemic uncertainty) are also shown. In regions of high predictive entropy (i.e., lighter regions) the GP term is associated with large epistemic uncertainties due to the lack of data.

Figure 4 shows the calibration results as the error norm versus cross-group (i.e., cross-dataset) variance μσ for all properties, grades, models, calibration approaches, and datasets. As expected, there is a strong linear correlation between the error norm error and μσ. In almost all the cases, the KOH approach has a lower error norm and μσ because it accounts for the model discrepancy via the GP term and leads to more accurate models. Generally, there are large errors and uncertainties in predicting the E change ratio and CTE change ratio due to the nature of the datasets for these properties, which tend to have more noise. For low fluences, IIDC tends to have less noise in the data, whereas for high fluences it has considerable noise. Out of the four properties, creep appears to have the lowest noise and is easier to predict. However, the only creep data available for the fitting are from the AGC8, which targeted low fluences (i.e, <1 × 1026 n0 m−2), and hence the creep versus fluence followed a linear trend that is relatively easier to fit.

Standard Bayesian and KOH Bayesian calibration approaches are represented as circles and squares, respectively, and denoted as “Bayes” and “KOH.” Arrows connect the standard and KOH Bayesian approaches, showing a reduction in error and group-level variance values when using KOH, one each for the four properties for the data point with the maximum reduction. Note that in the standard Bayesian approach, the variance accounts for both model discrepancy and experimental noise. In the KOH Bayesian approach, since the discrepancy is accounted for by the GP term, it is supposed to represent experimental noise and hence is less than that of the standard Bayesian approach. The different properties are distinguished by color. The individually fitted and Bradford unified physics-based models are distinguished by marker size. A single point is shown for each graphite grade (i.e., IG-110, NBG-18, PCEA, NBG-17, 2114), based on multiple datasets (i.e., AGC8, Campbell et al.9, and INNOGRAPH10), but those grades are not identified. Readers should refer to the supplementary material for more information.

Component-level performance impacts

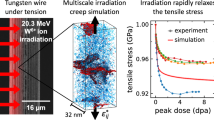

To demonstrate the impact of quantifying the model discrepancy via a GP, a finite-element model of a prototypical graphite reflector brick was analyzed. This reflector brick was subjected to high neutron dose, high temperatures, and temperature gradients. A thermo/mechanical analysis of the reflector was performed using the Grizzly code25, which is based on INL’s Multiphysics Object Oriented Simulation Environment (MOOSE) framework26. Figure 5a shows, for the NBG-18 grade using the individually fitted models, the difference in the maximum principal stresses between a model that considers the GP discrepancy term for all four properties and another that does not. The stress development in the brick is mainly driven by the irradiation effects, specifically the IIDC strain. Inclusion of the GP correction term in the model leads to a change in the predicted stress in the brick. The GP discrepancy term can result in a stress difference (absolute difference) of up to about 16MPa, especially near the control rod channel. This stress-difference plot also shows that using the GP term improves the stress state prediction the most near the large hole in the block that accommodates a reactor control rod. The influence of the GP discrepancy term on the time-dependent maximum principal stress behavior is shown in Fig. 5b. Of all the GP discrepancy terms for the various properties, the one for the IIDC has the largest impact on the time-dependent stress, both because of the importance of IIDC as a driver of stresses and because of the relative magnitude of the GP discrepancy term at high neutron fluences as seen in Fig. 3a. These differences in the predicted stress can greatly impact the predicted onset and propagation of cracking. Note that the location of the maximum principal stress in the reflector brick shifts over time, leading to kinks in the plotted maximum principal stress time history. For example, if at a certain time, location A has the greatest value for maximum principal stress in the entire reflector brick, with the maximum principal stress at this location being 15 MPa and decreasing with time, and the maximum principal stress at another location B is 15 MPa but increasing with time, then the plot showing the maximum principal stress versus time for the reflector brick will show a sudden change in the slope of the curve at this time: slope will change from negative to positive resulting in a kink.

a Spatial distribution of the absolute difference in the maximum principal stress in a graphite (NBG-18 grade) reflector brick model using the individually fitted property models between a model that considers the GP discrepancy term for all four properties and one that does not. This is shown at 14.5 years, when the difference is near its maximum. The GP discrepancy term, via fitting the data better at high neutron fluences, can result in significant stress changes, especially at the boundaries, which are subjected to large temperature and neutron flux gradients. b Time history of the maximum principal stress with and without the GP discrepancy terms for the various properties. The discrepancy term for the IIDC property has the largest influence on the component stress response.

The same analysis of the reflector brick was repeated for the other graphite grades considered in this study (except for 2114, whose data was limited to the low fluence range), and Fig. 6 shows the histories of the maximum absolute value of the difference in the local maximum principal stress between models with and without the GP correction for all four properties for all grades. This plot is presented as a function of both time and fluence. During the initial stage of operation, there is a rapid rise in the temperature of the fuel bricks adjacent to the reflector brick, causing the temperature of the reflector brick to also rise. The non-uniform thermal expansion generates stresses in the brick. Figure 6 shows that the difference in the stresses from the GP corrections starts very small, and increases with time for all the grades, although the difference tends to decrease slightly after about 20 years. The small difference in the stresses during the initial stage is a consequence of the contribution of the GP term to the coefficient of thermal expansion at low fluence being small for all the grades. As time progresses, the IIDC strain, as well as its GP correction term, increases and the influence of the IIDC-induced strain gradient on the stresses also increases. The contribution of the IIDC GP term is the most significant contribution to the component response among the GP terms for all properties considered. Among the grades considered here, the GP correction term has the largest impact on the stress for the NBG-18 grade, while it has the smallest effect on the IG-110 grade. The maximum values of principal stress reached for the IG-110, NBG-18, PCEA, and NBG-17 graphite bricks (for cases when contribution from all GP terms is considered) were 14.8 MPa, 31.6 MPa, 11.6 MPa, and 33.2 MPa, respectively. Considering these peak values of the stresses, the maximum difference in the stresses for between the models with and without the GP correction expressed relative to the maximum values is quite significant: 33% for IG-110, 52% for NBG-18, 43% for PCEA, and 70% for NBG-17. Additional results are presented in the supplementary material Tables S1 to S15.

This plot is presented as a function of both time and maximum fluence for four graphite grades. Note that the 2114 grade is not shown because only low-fluence data is available for that grade. The star and diamond symbols indicate the points when the 1102.23K (maximum temperature in the model) turnaround and crossover fluence values, respectively, are first reached.

Discussion

The mean-squared errors plotted in Fig. 4 indicate that the GP discrepancy term has a significant impact on improving the predictive performance of the property models. Specifically, considering the individually fitted model, the percentage error reductions—averaged across all the grades—from standard to KOH Bayesian approaches are 48.3%, 58.1%, 4.39%, and 6.7% for IIDC, creep, E change ratio, and CTE change ratio, respectively. Considering the Bradford physics-based model18, these values are 60.4%, 72.57%, 28.74%, and 28.12%. The experimental data for E change ratio and CTE ratio are noisier compared to those for IIDC and creep. Hence, the error reductions brought by the GP discrepancy term are highest for IIDC and creep comparatively. Although the Bradford physics-based model has a unifying structural connectivity factor incorporated into the functional forms across all properties, this does not necessarily lead to superior performance. The inherent noise in the data and the multiple data sources and grades complicate the fitting process despite physics elements being incorporated in the models’ functional forms. Ideally, for a perfect model, the magnitude of the GP discrepancy term will be very close to zero across all the experimental configurations. In reality, however, the GP term plays a significant role in promoting the predictive model to match the experimental data amidst the aforementioned complexities with the data. As observed from Fig. 3, in extrapolation regimes, the GP term is associated with large predictive entropies and should not be used because it is data-driven.

A hierarchical variance structure is necessary given that the experimental data come from multiple campaigns at different institutions. This permits a group-level noise to be assigned to each dataset while the cross-group noise is inferred. Specifically, for both the standard and KOH Bayesian approaches, the noise level associated with the AGC data group8 is 1–2 orders of magnitude smaller than that of either the Campbell et al.9 or INNOGRAPH10 data groups. This is due to the AGC experiments targeting a lower fluence regime (i.e., < 1.0 × 1026 n0 m−2) in which most of the properties follow a linear trend with fluence.

The improved predictions from the uncertainty-quantified models can have a significant impact on the design of components for advanced reactors as well as their operational aspects. The simulations using these models provide improved confidence in the predicted thermal-mechanical response of the reflector brick. Accurately predicting the stresses induced within graphite components exposed to the reactor environment is essential for ensuring safe and reliable reactor operation. For example, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code27 provides guidelines based on predicted stresses used during design to assess whether a graphite component will have an acceptably low probability of failure due to fracture. There are similar needs for accurate prediction of stress evolution for planning component inspection and replacement. As has been shown in the component simulation example, the effects of model form discrepancy on the stress states within a graphite component can be significant. The magnitudes of the discrepancies in the predicted stress are non-trivial relative to the tensile strength of these grades, so the choice of whether to include the GP correction could significantly impact fracture predictions. The methods shown here to explicitly quantify model-form discrepancy can be used to significantly improve both the accuracy of component-scale predictions and to quantify the uncertainty of those predictions.

Methods

Experimental data

The experimental data for the graphite properties of the five different grades are from the AGC campaign8, Campbell et al.28, and the INNOGRAPH campaign29. Table 1 shows the combinations of data used for the various models calibrated in this work.

The primary objective of the AGC campaign is to gather irradiation data by irradiating pairs of stressed and unstressed specimens in the ATR at INL using axial flux symmetry8. Four irradiation experiments (i.e., AGC-1, AGC-2, AGC-3, and AGC-4) have been completed, though post-irradiation examination data from AGC-4 are still being collected. The currently available data from the AGC 1–3 campaigns include design temperatures of 673.15 K, 873.15 K, and 1073.15 K at doses up to 0.5 × 1026 n0 m−2. The stressed samples were loaded at three design loads of 13.8 MPa, 17.2 MPa, and 20.7 MPa. The neutron doses in AGC 1–3 were not high enough for turnaround to be observed.

The INNOGRAPH experiments generated data on the irradiation behavior of graphite grades for high-temperature gas reactor applications29. The graphite grades were irradiated at 1023.15 K (INNOGRAPH-1) and 1223.15 K (INNOGRAPH-2). The INNOGRAPH-1A irradiation was conducted at 1023.15 K, accumulating a fluence between approximately 0.75 × 1026 n0 m−2 and 0.75 × 1026 n0 m−2. These samples were then further irradiated in the INNOGRAPH-1B campaign, accumulating a damage of up to 2.0 × 1026 n0 m−2. INNOGRAPH-2A and INNOGRAPH-2B were similarly executed at 750∘ to accumulate a damage of up to 1.25 × 1026 n0 m−2. Unlike the AGC campaigns, the fluence in the INNOGRAPH experiments was high enough for turnaround to be observed, but only thermomechanical properties were measured, and no creep testing was performed.

Campbell et al.28 performed irradiations in the flux trap of the HFIR at ORNL, and the changes in a predetermined set of physical, mechanical, and thermal properties were evaluated. The program also focused on assessing irradiation-induced creep under applied compressive stress. The irradiations were performed at design temperatures of 573.15 K, 723.15 K, 873.15 K, and 1023.15 K, a neutron fluence of up to 3.5 × 1026 n0 m−2, and a nominal applied load of 13.5MPa.

Predictive models

Irradiation and high temperatures activate several degradation mechanisms in nuclear-grade graphites, which result in changes to both the thermomechanical properties and the dimensions of graphite components30,31. This creates the need for dose- and temperature-dependent models to predict the change in the various properties. A common approach for developing such models is to develop a polynomial approximation of property change at discrete temperatures and dosages and interpolating intermediate values10,32. Here, a new set of expressions is proposed to capture both the temperature and dose dependence in a single expression for each individual property. In addition, a unified physics-based model proposed in the literature—and one that has garnered widespread interest—is summarized.

Individually fitted empirical models

In nuclear graphite, an increase in temperature results in an increase in the bulk CTE while under irradiation, and the irradiation-induced change in porosity initially leads to an increase in CTE, later followed by a reduction. The temperature dependence of CTE is based on the work of Windes et al.8,33:

where the parameters a, b, and c must be calibrated. The irradiation dependence of the model is represented via:

where Δα is the change in CTE with respect to the CTE of unirradiated graphite, α0, and the parameters a, b, and c must be calibrated. Under irradiation, the elastic modulus increases rapidly due to irradiation-induced pinning of the crystallite basal planes, followed by a plateauing attributed to the tightening of the microstructure due to reduced porosity and large dimensional changes. Upon further irradiation, a reduction in both Young’s modulus and strength is observed. The temperature dependence of Young’s modulus is represented using a second-order polynomial of the form:

where the parameters a, b, and c must be calibrated. Shibata et al. suggest that the Young’s modulus changes linearly with the irradiation dose before turnaround and quadratically post turnaround32. The irradiation-induced change in Young’s modulus can then be represented as:

where the sigmoid function smoothens the transition between linear and quadratic regimes and a, b, c, d, and f are tunable parameters.

The turnaround dose follows an Arrhenius-like behavior with respect to temperature and can be used to inform the quadratic polynomial form commonly used for fitting the IIDC12:

where Ea represents the activation energy, which is a parameter for model fitting; kB = 8.617333262 × 105 e V K−1 is the Boltzmann constant; and T denotes the irradiation temperature. The other fitting parameters in the expression are a and b.

Kelly and Foreman34 proposed a mechanism that explains how irradiation affects the creep behavior of graphite. They postulated that neutron irradiation creates basal plane pinning and unpinning sites in the crystals. Depending on the irradiation dose and temperature, either full or partial pinning may occur, but since the pinning points are interstitial clusters of 2–6 atoms35, they are annealed (destroyed) by further irradiation. Thus, irradiation releases dislocation lines from their original pinning sites, enabling the crystals to flow as a result of basal plane slip at a rate determined by the rate of pinning and unpinning of dislocations30,36. The linear viscoelastic creep model conforms to the Kelly-Foreman theory of creep with an initially large primary creep coefficient, while the dislocation pinning sites develop to the equilibrium concentration, at which time the creep coefficient has fallen to the steady-state or secondary value. The total creep strain εC is therefore defined as:

where σ denotes the applied stress, E0 represents the initial (pre-irradiated) Young’s modulus, γ is the fast neutron fluence, a and b are constants with a usually being one, and k is the secondary creep coefficient. Experimentally, the primary creep is observed to saturate at approximately the elastic strain, σ/E0. Assuming this is the case reduces the above to:

To account for the temperature dependence of creep, the following functional form is used:

where the parameters a and b must be calibrated from the experimental data.

Bradford and Steer model

Bradford and Steer13,18 introduced a unified physics-based model for irradiated graphite properties that centers around a structural connectivity term defined as:

where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of the normal distribution function and B is a scaling factor that determines the magnitude of the connectivity term. The structural connectivity term is then used to model the changes in various properties. The change is the elastic modulus and is modeled using a Knudsen-type relationship as:

where βG and βF, and ϵG and ϵF, are the Knudsen relationship constants and fractional volume changes associated with the underlying shrinkage and pore generation, and P is the low-dose saturated value of the irradiation pinning term. For the CTE, a linear relationship is used:

where D is a constant and αs is the residual stress annealed CTE.

The underlying shrinkage was based on a crystal shape change parameter represented by Gu and a pore generation term Fp, giving:

where the first term on the right-hand side denotes the underlying shrinkage, which depends on parameters A and k1, which control the magnitude and saturation dose, respectively. The second term accounts for the pore generation dimensional change with constant C determining the magnitude of pore generation, and the Gu term allows for pore closure to occur while the underlying shrinkage has not yet saturated.

The model accounts for the underlying crystal dimensional change rate and the accommodation of porosity distribution and supplements them with a connectivity-pore generation strain rate and densification and pore growth descriptions:

where the rates of saturation of the primary and recoverable creep components are controlled by the dose constants k1 and k2. The first and last terms are primary and secondary creep, and the middle term is recoverable creep. The coefficient β is derived from the irrecoverable strain after thermal annealing. The initial creep modulus changes under irradiation as a result of both structural (S) and radiolytic oxidation (W) changes to the elastic modulus.

Considering constant temperature during irradiation, Saitta et al.14 denoted the structural connectivity term as:

where the variables μSc and σSc are temperature-dependent material parameters. The Young’s modulus can then be represented as:

where Pem is the irradiation pinning parameter for Young’s modulus, kem is the irradiation pinning saturation rate, and the Scr term represents the change in Young’s modulus due to irradiation damage:

where Cem is the Young’s modulus connectivity parameter, βd and βpg are the densification and pore generation parameters, and δvd and δvpg are the densification and pore generation volume changes. Since the densification and pore generation terms were not individually known in the data used, the Scr expression was collapsed into a single term as:

resulting in the following expression:

where a, b, c, and β are the parameters to be fitted. For each grade, μSc and σSc in Equation (14) are fit using the following approach: (1) the temperature clusters in the data set are identified; (2) For each temperature cluster, we deterministically fit the E change property, where μSc and σSc are also tunable parameters; (3) Once we obtained μSc and σSc for the different temperature clusters, we fit each of these as a function of the temperature; and (4) The fitted μSc and σSc as a function of temperature were used across all the four properties for Bayesian calibration with and without the model discrepancy term.

Following from the same expression, the IIDC strain can be represented in terms of the Sc parameter as:

where the parameters to be fitted are a, b, and k.

Saitta et al.14 subdivided the creep into primary, secondary, and recoverable creep components, but given the experimental data available, the primary and recoverable creep components were combined yielding:

where parameters k, α, and β must be experimentally calibrated.

Finally, the CTE expression can be reduced to:

where D captures the gradual change of CTE due to irradiation, P and k capture the pinning behavior and a captures the interaction between creep and CTE. All of these parameters must be fitted from experimental data.

Bayesian calibration with a model discrepancy term and a hierarchical variance structure

Given N experimental data points from G groups, the relation between the model prediction and the jth experimental observation from the gth group is given by16:

where \({\mathcal{D}}\) is the experimental observation given the experimental configuration Θ, \({\mathcal{M}}(.)\) is the model prediction dependent on the experimental configuration and the model parameters θ, and \({\varepsilon }_{i}^{g}\) is the residual. In the above equation δ(.) is the model discrepancy term, which is only a function of the experimental configuration. This term is modeled as a GP to capture any hidden trends in the experimental data not already captured by the model \({\mathcal{M}}(.)\). Note that the dataset grouping is only applied to the residual term \({\varepsilon }_{j}^{g}\) because we are interested in the hierarchical structure for the noise variance. The mean model prediction and the GP discrepancy term are homogenized across all the dataset groups. As such, \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{g}\) corresponds to the experimental noise for the gth group. We further model the logarithm of \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{g}\) to originate from a Gaussian distribution and impose priors on its mean and standard deviation:

where μ0 is set to the logarithm of the standard error for a deterministic fit and \({\mathcal{IG}}(.)\) is an inverse gamma distribution.

The GP discrepancy term is expressed as37:

where m(Θ) and \(k(\Theta ,\,{\Theta }^{{\prime} })\) are the mean and covariance as a function of the experimental configuration and γδ is the vector of GP hyperparameters. The covariance function itself is defined through a kernel function κ(. , . ). Here, we specifically adopted the squared exponential kernel:

where γδ = {τ2, ld, η2} ∀ d ∈ {1, …, D}, with D representing the dimensionality of each experimental configuration. Prior distributions need to be specified over the GP hyperparameters γδ = {τ2, ld, η2}. We use the following priors over the hyperparameters:

The joint posterior over the model parameters θ, GP discrepancy term hyperparameters γδ, within-group noise \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{g}\), cross-group noise mean μσ, and cross-group noise standard deviation σσ is given by:

where \({\mathcal{L}}(.)\) is the likelihood function dependent on the model, experimental data, and experimental configurations and f(.) represents the prior distribution over the quantities of interest to be inferred. The likelihood function is further expressed as:

The prior distribution over the model parameters θ is set to an independent Gaussian with mean as the deterministic fit parameter values and the standard deviations as 10% of the mean values. Figure 7 shows a schematic of the impact of the GP discrepancy term when predicting noisy data with inadequate models.

We are interested in jointly inferring the posterior distribution of the model parameters θ, the group-level noise term \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }^{g}\), the cross-group mean and standard deviation of the noise {μσ, σσ}, and the GP discrepancy term hyperparameters γδ. This leads to the joint posterior distribution being complex and highly nonlinear. As such, we used the NUTS algorithm to draw samples from the joint posterior19,38. We used the Pyro package to perform the Bayesian inference39. For generating the results, we used 1500 burn-in samples and then drew 3000 samples from the posterior distribution. In the NUTS algorithm, we performed both step size and mass matrix adaptation and set the target acceptance probability and maximum tree depth as 0.8 and 10, respectively.

Component-level model

We used a representative prismatic core reflector brick from a VHTR to demonstrate the impact of the calibrated structural graphite material models and assess the importance of model-form assumptions on component-level response. The core design of the reactor reflector brick is based on the Gas Turbine Modular Helium Reactor40. This core configuration has been analyzed by others41,42 to determine the neutron fluxes, fast neutron fluence, gamma heats, and compact powers. The considered reflector brick is adjacent to the annular fuel region of the core and is subjected to high neutron dose, high temperatures, and high-temperature gradients. The computational model was developed using the Grizzly nuclear reactor structural materials and aging application25. A simplified geometry of the brick, without fuel handling and dowel pin holes, was used for this analysis. For the analysis, we considered a two-dimensional model and assumed a generalized plane strain condition, which permits non-zero strains in the axial direction of the brick but requires them to be spatially uniform. The model mesh has 4,140 first-order quadrilateral elements.

We simulated the same reflector brick for each of the graphite grades considered here. The analysis incorporated models for IIDC, CTE, secondary creep, Young’s modulus, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity. The IIDC, CTE, secondary creep, and Young’s modulus were calibrated in this study. It is important to note that while primary creep is important, and is accounted for in calibration of the secondary creep models, it is not included in the component model. Including primary creep is the topic of ongoing development, and is expected to somewhat reduce stresses in the component model. The models for thermal conductivity (k in W m−1 K−1) and specific heat (Cp in J kg−1 K−1) come from Shibata et al.32 and Mauryama et al. and Srinivasan et al.11,43, respectively, and are assumed to be the same for all graphite grades considered here. The CTE data had significant scatter for graphite grades NBG-18, NBG-17, and PCEA, making it challenging to quantify model discrepancy. Therefore, GP discrepancy in the CTE model was considered only for the IG-110 and 2114 graphite grades. Also note that the fits for the 2114 grade are only valid up to neutron fluence 0.55 × 1026 n0 m−2 due to a lack of available data beyond that fluence level, so the block was not simulated for that grade.

The graphite brick model is subjected to fast neutron flux, which varies spatially due to self-shielding. This is prescribed through a spatially varying function in the present work, but it could in general be provided by a neutron-transport model. A thermal analysis of the reflector brick is presented in Bratton et al.44. We used similar thermal boundary conditions: incorporated heat flux into the brick from three faces that are adjacent to the fuel bricks, considered gamma heat generation in the brick, and applied convective heat loss at the brick face radially opposite the fuel bricks. The heat fluxes and the convective heat loss coefficients were set to match the temperature distribution shown in Bratton et al.44. The gamma heat distribution is assumed to be radial only42,44. The analysis reflects the performance of the reflector brick over the course of 30 years. The maximum neutron fluence in the reflector brick at the end of 30 years is about 2.5 × 1026 n0 m−2. Figure 8 shows the temperature and the fast neutron fluence distributions in the reflector brick at the end of 30 years.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to our institutional policies but may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Scarlat, R. O. et al. Design and licensing strategies for the fluoride-salt-cooled, high-temperature reactor (FHR) technology. Prog. Nucl. Energy 77, 406–420 (2014).

Arregui-Mena, J. D. et al. A review of finite element method models for nuclear graphite applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 27, 331–350 (2020).

Price, D., Roskoff, N., Radaideh, M. I. & Kochunas, B. Thermal modeling of an eVinciTM-like heat pipe microreactor using OpenFOAM. Nucl. Eng. Des. 415, 112709 (2023).

Prithivirajan, V. Examining graphite degradation in molten salt environments: A chemical, physical, and material analysis. Tech. Rep. TLR-RES/DE/REB-2024-14, Idaho National Laboratory https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML2423/ML24236A722.pdf (2024).

Lan, T., Peng, X., FengSheng & Tan, W. Seismic modeling and simulation of the graphite core in gas-cooled micro-reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 431, 113714 (2025).

Srinivasan, M. Design and manufacture of graphite components for 21st century small modular reactors. Nucl. Eng. Des. 386, 111568 (2022).

Metcalfe, M. Damage tolerance in the graphite cores of UK power reactors and implications for new build. Nucl. Eng. Des. 406, 112237 (2023).

Windes, W. E., Rohrbaugh, D. T., Swank, W. D. & Cottle, D. L. AGC-3 specimen post-irradiation examination data package report. Tech. Rep. INL/EXT-17-43823, Idaho National Laboratory (2017).

Campbell, A. A., Katoh, Y., Snead, M. A. & Takizawa, K. Property changes of G347A graphite due to neutron irradiation. Carbon 109, 860–873 (2016).

Heijna, M., de Groot, S. & Vreeling, J. A. Comparison of irradiation behaviour of HTR graphite grades. J. Nucl. Mater. 492, 148–156 (2017).

Srinivasan, M., Marsden, B., von Lensa, W., Cronise, L. & Turk, R. Appendices to the assessment of graphite properties and degradation, including source dependence. Tech. Rep. TLR/RES/DE/REB-2021-08, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2021).

Bajpai, P., Prithivirajan, V., Munday, L. B., Singh, G. & Spencer, B. W. Development of graphite thermal and mechanical modeling capabilities in Grizzly. Tech. Rep. INL/RPT-24-78905, Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID (2024).

Davies, M. A. & Bradford, M. A revised description of graphite irradiation induced creep. J. Nucl. Mater. 381, 39–45 (2008).

Saitta, M., Johannes van Zanten, F. & Baylis, S. Physics informed graphite material model. In Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, V001T01A041 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2024).

Dhulipala, S. L. N., Simon, P. C. A., Demkowicz, P. A., Hirschhorn, J. A. & Novascone, S. R. Unpacking model inadequacy: The quantification of silver release from TRISO fuel by considering empirical and mechanistic approaches. J. Nucl. Mater. 610, 155795 (2025).

Kennedy, M. C. & O’Hagan, A. Bayesian calibration of computer models. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 63, 425–464 (2001).

Dhulipala, S. L. N., Bajpai, P., Singh, G. & Spencer, B. W. Bayesian calibration of nuclear graphite property models accounting for model inadequacy and impacts on component performance. Tech. Rep. INL/RPT-25-86883, Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID United States (2025).

Bradford, M. R. & Steer, A. G. A structurally-based model of irradiated graphite properties. J. Nucl. Mater. 381, 137–144 (2008).

Hoffman, M. D. & Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623 (2014).

Béghein, P., Berlioux, G., du Mesnildot, B., Hiltmann, F. & Melin, M. NBG-17–An improved graphite grade for HTRs and VHTRs. Nucl. Eng. Des. 251, 146–149 (2012).

Arendt, P. D., Apley, D. W. & Che, W. Quantification of Model Uncertainty: Calibration, Model Discrepancy, and Identifiability. ASME J. Mech. Des. 134, 100908 (2012).

MacCallum, R. C. & O’Hagan, A. Advances in modeling model discrepancy: Comment on Wu and Browne. Psychometrika 80, 601–607 (2015).

Maupin, K. A. & Swiler, L. P. Model discrepancy calibration across experimental settings. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 200, 106818 (2020).

White, A. & Mahadevan, S. Discrepancy modeling for model calibration with multivariate output. Int. J. Uncertain. Quantification 13, 1–23 (2023).

Spencer, B. W. et al. Grizzly and BlackBear: Structural component aging simulation codes. Nucl. Technol. 207, 981–1003 (2021).

Giudicelli, G. et al. 3.0-MOOSE: Enabling massively parallel multiphysics simulations. SoftwareX 26, 101690 (2024).

American Society of Mecahnical Engineers. Section III. Rules for Construction of Nuclear Facility Components. Division 5. High Temperature Reactors. Tech. Rep. ASME BPVC.III.5-2023, ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (2023).

Campbell, A. A. & Katoh, Y. Summary report on effects of irradiation on material IG-110 – prepared for Toyo Tanso Co., Ltd. Tech. Rep. ORNL/TM-2017/705, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN, United States (2017).

Vreeling, J., Wouters, O. & Van der Laan, J. Graphite irradiation testing for htr technology at the high flux reactor in petten. J. Nucl. Mater. 381, 68–75 (2008).

Campbell, A. A. & Burchell, T. D. Radiation effects in graphite. In Konings, R. J. & Stoller, R. E. (eds.) Comprehensive Nuclear Materials, 398–436 (Elsevier, Oxford, 2020), second edition edn.

Haag, G. Properties of ATR-2E graphite and property changes due to fast neutron irradiation. Tech. Rep. 4183, Institut für Sicherheitsforschung und Reaktortechnik, Jülich, Germany https://juser.fz-juelich.de/record/49235/files/Juel_4183_Haag.pdf (2005).

Shibata, T. et al. Draft of standard for graphite core components in high-temperature gas-cooled reactor. Technical Report JAEA-Research 2009-042, Japan Atomic Energy Agency (2010).

Windes, W., Swank, W. D., Rohrbaugh, D. & Lord, J. AGC-2 graphite preirradiation data analysis report. Tech. Rep. INL/EXT-13-28612, Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID, United States (2013).

Kelly, B. T. & Foreman, A. J. E. The theory of irradiation creep in reactor graphite – The dislocation pinning-unpinning model. Carbon 12, 151–158 (1974).

Martin, D. & Henson, R. The scattering of long wavelength neutrons by defects in neutron-irradiated graphite. Philos. Mag. 9, 659–672 (1964).

Kelly, B. T., Martin, W. H. & Nettley, P. Dimensional changes in pyrolytic graphite under fast-neutron irradiation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 260, 37–49 (1966).

Rasmussen, C. E. Gaussian Processes in Machine Learning (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004).

Neal, R. M. Handbook of Markov chain Monte Carlo, chap. MCMC using Hamiltonian dynamics (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2011).

Bingham, E. et al. Pyro: Deep Universal Probabilistic Programming. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 20, 1–6 (2019).

General Atomics. Gas turbine-modular helium reactor (GT-MHR) conceptual design description report. GA Proj. 7658, 910720 (1996).

MacDonald, P. E. et al. NGNP point design-results of the initial neutronics and thermal-hydraulic assessments during FY-03, Rev. 1. Tech. Rep., Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID (United States) (2003).

Sterbentz, J. W. Calculated neutron and gamma-ray spectra across the prismatic very high temperature reactor core. In Reactor Dosimetry State of the Art 2008, 596–606 (World Scientific, 2009).

Maruyama, T., Kaito, T., Onose, S. & Shibahara, I. Change in physical properties of high density isotropic graphites irradiated in the ‘JOYO’ fast reactor. J. Nucl. Mater. 225, 267–272 (1995).

Bratton, R. Modeling mechanical behavior of a prismatic replaceable reflector block. Tech. Rep. INL/EXT-09-15868, Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lynn B. Munday at Idaho National Laboratory for his technical review of this paper. The authors thank James E. Lainsbury at Idaho National Laboratory for editing this paper. This research is supported through Battelle Energy Alliance LLC under contract no.~DE-AC07-05ID14517 with the U.S. Department of Energy, using funding from the Nuclear Energy Advanced Modeling and Simulations (NEAMS) program. This research made use of the resources of the High-Performance Computing Center at the Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Nuclear Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under contract no.~DE-AC07-05ID14517.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D., P.B., G.S., and B.S. conceived and designed the study. S.D. developed the mathematical framework and the code base for Bayesian calibration of different property models by considering the Gaussian process model discrepancy and a hierarchical variance structure. P.B. curated the experimental data from various graphite campaigns for several grades and properties and conceptualized expressions used in the empirical model. G.S. conducted the component level impact analysis of the graphite property models. B. S. supervised this study and provided critical feedback, and helped shape much of the analysis and manuscript. S.D. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhulipala, S.L.N., Bajpai, P., Singh, G. et al. Bayesian calibration of irradiated graphite property models under high temperatures. npj Mater Degrad 9, 166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00710-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00710-7