Abstract

Intergranular stress corrosion cracking (IGSCC) of austenitic stainless steels remains a critical degradation mechanism in light water reactors (LWRs), driven by coupled mechanical, electrochemical, and microstructural factors. Accurate prediction of crack growth rates (CGR) is essential for effective monitoring and mitigation. Here, we develop a comprehensive machine learning (ML) framework to model CGR in both boiling water reactors (BWRs) and pressurized water reactors (PWRs) using a curated database, integrating experimental measurements with ML-based and physics-informed preprocessing. Categorical boosting (CatBoost) was used for point prediction and uncertainty quantification (UQ) of CGR, and compared with natural gradient boosting (NGBoost), Gaussian process regression (GPR), and TabNet. CatBoost outperformed other models and, when combined with post-hoc calibration, provided reliable uncertainty estimates. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) applied to CatBoost revealed both individual and interaction effects of features on CGR and enabled comparison of CGR behavior between BWR and PWR environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear power contributes ~10% of global electricity generation1, with Light Water Reactors (LWRs)—which use light water as both a coolant and a neutron moderator—accounting for nearly 90% of the electricity generated2. There are two primary types of LWRs: Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs) and Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs), each operating under distinct electrochemical conditions3,4. In Normal Water Chemistry (NWC) of BWRs, the radiolysis of water produces radicals and oxidizing products, increasing the electrochemical potential (ECP)4. However, modern BWRs have transitioned to Hydrogen Water Chemistry (HWC), in which 0.3–2 ppm of dissolved hydrogen is added to suppress radiolysis and reduce the ECP4. In PWRs, an even more reducing environment is achieved by maintaining a dissolved hydrogen concentration of 25–50 cm³ per kg of water (at standard temperature and pressure, STP)4. Additionally, BWRs use high-purity water as coolant, whereas PWRs adjust their coolant chemistry by adding lithium (as lithium hydroxide) and boron (as boric acid)4.

Extensive operational experience has shown that intergranular stress corrosion cracking (IGSCC) has affected austenitic stainless steel (SS) components in both BWR and PWR systems. While widespread IGSCC was reported in BWR piping from the early 1970s through the 1980s5,6, its overall occurrence in LWRs has since declined due to various mitigation measures6. Nevertheless, IGSCC continues to necessitate unscheduled inspections and premature repairs of critical components, resulting in substantial economic losses7,8. More recently, unexpected and extensive IGSCC has been identified in French PWRs9, highlighting the persistent risk. These developments underscore the ongoing need to deepen our understanding of IGSCC, a degradation mechanism driven by complex interactions among mechanical, electrochemical, and microstructural factors. Concurrently, the development of accurate models to predict crack growth rates (CGR) is essential for effective monitoring, mitigation, and risk management.

Ford and Andresen10,11 developed the Plant Life Extension Diagnosis by General Electric (PLEDGE) model by integrating the slip-dissolution mechanism12,13 with empirical fitting to CGR data under varying electrochemical conditions. Macdonald et al.14,15 introduced the Coupled Environmental Fracture Model (CEFM), whose theoretical basis is the differential aeration hypothesis16. Crack propagation in the model is assumed to be driven by the slip-dissolution mechanism, conceptually augmented by hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC)17,18. Initially developed to predict CGR in sensitized Type 304 SSs in BWR environments, the model has since been adapted and customized for the same materials in dilute sulfuric acid solutions19 and Alloys 600 in PWR environments20. Shoji et al. proposed the Fracture and Reliability Research Institute (FRI) model, which is also based on the slip-dissolution mechanism but incorporates unique correlations for crack tip strain rate and solid-state oxidation kinetics21,22. In addition to these mechanistic models, several traditional empirical models have been proposed, which exploit available CGR data to predict crack growth in nickel alloys23,24,25 and austenitic SSs26,27. Although these empirical models do not explicitly account for the underlying physical processes involved, they can serve as an alternative or complement to mechanistic models, particularly given the continuing uncertainty surrounding the governing mechanisms of IGSCC propagation.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising tool for predictive analytics. Unlike mechanistic and traditional empirical models, ML models can efficiently process large datasets and uncover complex relationships between numerous variables with minimal human effort and little reliance on mechanistic assumptions. Despite their potential, only a few studies have applied ML models to predict IGSCC growth rates in LWR environments. Among the earliest examples is the work by Lu et al.28, who developed an artificial neural network (ANN) model to predict CGR in Type 304 SSs under BWR environments. Building on this, Shi et al.29 created an ANN model for the same purpose, incorporating input variables such as stress intensity factor, temperature, solution conductivity, ECP, pH, and degree of sensitization (DoS). Shi et al. further extended this approach to predict CGR in Alloy 600 under PWR environments, adding variables such as cold work level, lithium (Li) and boron (B) concentrations, in addition to those previously considered30. More recently, Wang et al.31 employed various ML models to predict CGR in Types 304 and 316 SSs in PWR environments, utilizing a relatively limited dataset, and considering stress intensity factor, temperature, cold work, yield strength, Vickers hardness, and carbon content.

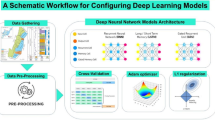

In this work, we focus on modeling the IGSCC growth rate in austenitic SSs under both BWR and PWR environments. Unlike previous studies restricted to specific materials or environments and primarily focusing on CGR prediction, we propose a more comprehensive ML framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1. First, a comprehensive and well-curated database was constructed from multiple sources, with external ML and physical models applied during data preprocessing to enhance data quality. Secondly, a sophisticated ML algorithm, categorical boosting (CatBoost) was trained with root mean squared error (RMSE), negative log-likelihood (NLL), and quantile losses, and evaluated using cross-validation. For comparison, additional algorithms—including natural gradient boosting (NGBoost), Gaussian process regression (GPR), and TabNet—were also evaluated. Next, the uncertainty of predictions from CatBoost models trained with NLL or quantile losses was quantified and evaluated using cross-validation. To this end, post-hoc methods such as linear NLL calibration and conformal prediction (CP) were applied to calibrate CatBoost’s predictive uncertainty, with NGBoost and GPR serving as benchmarks. Lastly, CatBoost, which was found to outperform other models, was interrogated using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) to uncover the correlations between features and the CGR captured by the model. This approach allowed us to successfully gain valuable insights into individual and interaction effects of features on CGR.

Results

Evaluation of model accuracy

The evaluation of model accuracy was conducted using the curated IGSCC dataset comprising BWR and PWR conditions, as summarized in Table 1. Model performance was assessed using a 5-fold cross-validation scheme, applied in two training modes: (1) separate training on the BWR and PWR datasets, and (2) a combined mode, in which BWR and PWR data were merged for training. In separate training, features with constant values within a given dataset were removed—for example, Li and B concentrations were removed in BWR training since their values are zero—whereas in combined training all features were retained, as features constant in one dataset varied in the other. Evaluation was performed for each dataset individually. The main results presented here focus on the CatBoost model trained with RMSE and NLL losses, while results for CatBoost with quantile loss, as well as for NGBoost, GPR, and TabNet are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Figures 2 and 3 present parity plots comparing the predicted and measured CGRs on the validation subsets across 5-fold cross-validation for CatBoost trained with RMSE and NLL (mean-based) losses, respectively. For each model, plots from separated and combined training modes are shown side by side for both BWR and PWR datasets. The diagonal line represents perfect prediction; thus, points closer to the line indicate higher accuracy. Data points are color-coded by environment (BWR vs. PWR) to illustrate each model’s performance for different reactor types. Performance metrics—coefficient of determination (R²) and mean absolute error (MAE)—are reported as mean ± standard deviation across the five folds.

Along with CatBoost trained with quantile loss (Supplementary Fig. 1), the resulting average R² values range from 0.787 to 0.83 for both BWR and PWR data across all loss functions and training modes, indicating that CatBoost explains ~79–83% of the total CGR variance (i.e., variance irrespective of feature values) on unseen data. Given that CGR is known to exhibit substantial variance even for fixed input conditions32, this is a promising result. The corresponding average MAEs are at or below 0.275, corresponding to geometric-mean multiplicative error of ~1.88 (i.e., 100.275). The geometric-mean multiplicative error serves as a representative factor by which predicted CGRs typically differ from measured values, although individual deviations may vary.

Notably, CatBoost achieves the best performance when trained with RMSE loss, outperforming both NLL and quantile losses. RMSE is a simple loss function that directly minimizes the average squared error between predictions and targets, focusing solely on point accuracy. For quantile loss, point estimates are obtained using the 0.5 quantile, corresponding to the conditional median, which—like RMSE—targets only point prediction; however, its performance is slightly worse than that of RMSE. While the conditional median is more robust to skewed noise, such a property does not appear to be prominent in the current dataset. Additionally, CatBoost appears to be more finely tuned for RMSE loss by default. In contrast, the NLL loss is inherently more complex, as it requires joint optimization of both the predicted mean (\(\hat{\mu }\)) and uncertainty (\(\hat{\sigma }\), in practice reparametrized as \(\log \hat{\sigma }\)). This coupling can hinder the accuracy of \(\hat{\mu }\) due to trade-offs with the predicted uncertainty.

Figure 4 compares the performance metrics of all models evaluated in this study across reactor conditions and training modes. NGBoost, GPR, and TabNet (see Supplementary Figs. 2–4 for their parity plots) also achieve satisfactory results, although their performance is inferior to that of CatBoost. Previous studies33,34,35 also showed that CatBoost has consistently demonstrated superior predictive accuracy compared to other models. The strong performance of CatBoost is likely attributable to its ordered boosting technique36, which helps mitigate prediction shift and improves generalization.

The impact of training mode (separated vs. combined) varies across models. Combined training is intended to promote transfer learning by leveraging shared patterns between environments. For CatBoost—regardless of the loss function—performance remains largely consistent between separated and combined training. With RMSE and quantile losses, combining datasets slightly improves average R² on BWR data, though the change remains within the standard deviation range, and the reduction in average MAE is marginal. The gain in average R² likely stems from reductions in a few large residuals. In contrast, NGBoost exhibits consistent performance degradation under combined training, likely due to its limited capacity to handle increased complexity from environment-specific patterns. GPR shows stable performance across training modes, whereas TabNet exhibits slightly improved performance on PWR data under combined training but remains unaffected on BWR data.

Overall, these results suggest limited evidence for positive transfer learning. While the BWR and PWR datasets may not share fully consistent signal patterns, the strong performance of CatBoost under combined training indicates the presence of partially overlapping trends. This is further supported by the finding that NGBoost still performs reasonably well, although it appears less flexible than CatBoost in handling the increased complexity of the combined datasets. However, model performance alone is insufficient to draw firm conclusions—further investigation into the underlying signal similarities is warranted.

Evaluation of uncertainty quantification

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) was carried out using a 5-fold cross-validation strategy, allowing uncertainty to be estimated across the entire dataset while preventing data leakage. For all models, training was performed separately for the BWR and PWR datasets. When post-hoc calibration (i.e., linear NLL calibration or CP) was applied to CatBoost, the training data were further split, with 80% used for model training and 20% reserved for calibration. This calibration set was used to determine parameters or correction factors to adjust the model’s uncertainty estimates. The full training set was subsequently used to retrain the model, applying the previously determined calibration parameters to produce the final uncertainty estimates. While post-hoc calibration is generally designed to adjust uncertainty without retraining, we observed that retraining enhanced point-prediction accuracy with minimal impact on the reliability of uncertainty estimates. The primary results presented here pertain to the CatBoost model using NLL loss, while comparative results for CatBoost model using quantile loss, NGBoost and GPR are included in the Supplementary Materials.

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the 95% prediction intervals generated on the validation folds during 5-fold cross-validation for CatBoost models. In each figure, the black line represents the model’s point predictions of CGR—specifically, the predicted mean. The green shaded area denotes the associated 95% prediction interval. Data points along the x-axis are sorted by increasing predicted CGR to enable clearer visualization of how interval widths vary across the prediction spectrum.

Prediction intervals from CatBoost models, whether trained with NLL (Fig. 5) or quantile loss (Supplementary Fig. 5), consistently underestimate the variability in measured CGRs for both BWR and PWR datasets, as evidenced by empirical coverages falling below the nominal 95% level. This undercoverage likely stems from CatBoost’s high flexibility, which enables tight fits to the training data, allowing for high point estimate accuracy. However, this tight fit can cause models to perceive reduced variability in the target variable, resulting in prediction intervals that are too narrow. The issue is more pronounced with NLL loss, where improvements in point prediction (i.e., reductions in the squared error term) directly incentivize the model to decrease the predicted \(\log \hat{\sigma }\), thereby producing even narrower intervals.

When combined with post-hoc calibration methods, CatBoost models show substantial improvements in empirical coverage, approaching the nominal 95% level for both BWR and PWR datasets. However, CatBoost models trained with quantile loss and calibrated using CP produce asymmetric intervals that fail to adequately capture the underlying uncertainty: the upper bounds are too conservative (i.e., severely overestimated) for low CGR values, while the lower bounds are frequently too optimistic (i.e., severely underestimated) for high CGRs (see Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, CatBoost models trained with NLL loss and calibrated using linear NLL calibration achieve empirical coverages close to the nominal level, with interval widths that more faithfully reflect the observed variability in CGR (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the combination of NLL loss and linear NLL calibration provides a more balanced and robust approach to UQ for CGR prediction, offering well-calibrated intervals without introducing excessive conservatism.

NGBoost produces wider and more reliable intervals than uncalibrated CatBoost, likely at the cost of reduced point accuracy, yet its coverage still falls short of the nominal 95% for both BWR and PWR datasets (Supplementary Fig. 7). GPR, on the other hand, achieves empirical coverage close to the nominal level for both datasets (Supplementary Fig. 8). Its strong uncertainty estimation likely stems from its Bayesian formulation, which assumes smoothness across the feature space, allowing it to generalize well even in underrepresented regions by propagating uncertainty from nearby training points.

Model explanation using SHAP

To ensure reliable explainability, CatBoost with RMSE loss—the model that achieved the highest point prediction accuracy—was analyzed using the TreeSHAP method, which provides fast and accurate computation of SHAP values for tree-based models37. Separate CatBoost models were trained on the full BWR-only and PWR-only datasets to investigate environment-specific behaviors and address a key question: are the mechanisms driving crack propagation in BWRs and PWRs similar, or are they fundamentally different?

Figure 7a, b presents the SHAP summary plots for the BWR and PWR models, respectively. Each point on the plots corresponds to an individual data point in the dataset. For continuous features, the color gradient—from blue (low values) to red (high values)—represents the feature value. The categorical feature, orientation (i.e., crack orientation relative to the applied deformation), does not have an associated color scheme. The SHAP value, plotted along the horizontal axis, indicates the impact of each feature on the model’s prediction: positive values push the prediction higher, while negative values reduce it. Along the vertical axis, features are ordered by their average absolute SHAP values, with higher values positioned at the top. The bar charts in Fig. 7c, d shows these average absolute SHAP values in the respective models, reflecting the relative importance of each feature. While the BWR and PWR models differ in overall feature ranking, several key features—such as ECP, DoS, yield strength (YS), and stress intensity factor (K)—consistently rank among the most important in both environments. Notable differences emerge for features such as conductivity (κ), orientation, test temperature (T), and Cr content.

The SHAP summary plots (Fig. 7a, b) also offer a general view of how individual features influence CGR predictions. Color gradients help illustrate whether increasing a feature value tends to raise or lower the prediction. For instance, ECP, YS, and K demonstrate a consistent trend across both BWR and PWR models, where higher feature values correspond to increased SHAP values and thus higher predicted CGR. In contrast, features such as DoS, κ, pH, and T display varying effect directions between the two models, implying environment-specific influences. However, these visualizations do not capture the full complexity of feature effects.

To explore feature effects in greater detail, selected SHAP dependence plots are presented in Figs. 8–10 and Supplementary Figs. 9–18. Each point represents an individual data instance, with the horizontal axis indicating the feature value and the vertical axis showing the corresponding SHAP value. In Figs. 8–10 and Supplementary Fig. 18, points are color coded to illustrate interactions with a secondary feature, where red denotes high values and blue denotes low values of that feature.

Figure 8 presents SHAP dependence plots for ECP under BWR conditions. In the low-ECP region (ECP<–0.5 VSHE), SHAP values exhibit a wide vertical spread (up to ~1.0), indicating possible interactions with other features. As ECP increases beyond –0.2 VSHE, SHAP values rise sharply with an average slope of ~3.5 per 0.1 VSHE, reflecting a strong positive influence on CGR predictions. The spread at low ECP appears to result from interactions with DoS (Fig. 8a) and/or YS (Fig. 8b), with ECP showing higher SHAP values for non-sensitized (DoS = 0) and cold-worked (high YS) SSs. However, the scarcity of data for non-treated materials (both non-sensitized and non-cold-worked) in this region prevents clear separation of DoS and YS contributions. The interaction between ECP and YS appears more distinct, as the few non-treated data points (blue in both plots) show ECP contributions more consistent with those of sensitized materials. Above –0.2 VSHE, interaction effects appear to diminish, as SHAP values increase consistently with ECP regardless of DoS or YS, at least up to ~0.15 VSHE, beyond which interpretation is limited due to the sparsity of non-treated and cold-worked data.

Under PWR conditions (Supplementary Fig. 9), SHAP values show minimal variation below ~–0.5 VSHE, then increase with ECP up to the maximum value, with an average slope of ~0.16 per 0.1 VSHE. The PWR dataset consists predominantly of cold-worked SSs. For comparison, cold-worked data in BWR conditions (warmer-colored points in Fig. 8b) increase by ~0.9 in SHAP values from ~–0.55 VSHE to 0 VSHE, corresponding to an average slope comparable to the PWR trend. The only intermediate points (at ~–0.2 VSHE) have SHAP values of ~–0.5, slightly below the expected trend but still within the observed PWR scatter of ~0.3. This suggests that the SHAP trend between BWR and PWR conditions could still align in this ECP range for cold-worked SSs, although additional BWR data would be useful to confirm this. SHAP values in the PWR model are generally higher than in the BWR model at overlapping ECP values, but this difference likely arises from the different SHAP baseline values used in the two models.

Figure 9 shows SHAP dependence plots for T in the BWR and PWR models. While the T ranges partially overlap, the SHAP patterns exhibit both similarities and differences. In both models, SHAP values display substantial vertical scatter below 300 °C, primarily due to interactions between T and DoS. For sensitized steels (DoS > 0), no clear trend is observed below ~300 °C in either model, despite differing electrochemical conditions—mostly strongly oxidizing (ECP > –0.05 VSHE) in BWR and reducing (ECP < –0.5 VSHE) in PWR—suggesting that the ambiguous T dependence persists under both conditions. Interestingly, in the PWR model, SHAP values for sensitized steels also increase with T above 300 °C, up to ~340 °C, though data are limited (Fig. 9b). In contrast, for non-sensitized steels (DoS = 0), SHAP values generally rise with T in both models, with a more pronounced increase in PWR (~0.7 from 250 °C to 325 °C; Fig. 9b, c) than in BWR (~0.25 over the same range; Fig. 9a). These patterns are more clearly illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 11, which isolates non-sensitized SSs in both models. In the PWR model, the rise of SHAP values diminishes around 330 °C, above which higher YS tends to be associated with higher SHAP values, whereas lower YS corresponds to lower SHAP values and, in one case, a pronounced drop at the highest T of ~366 °C (Fig. 9c).

Figure 10 presents the SHAP dependence plots for DoS in both the BWR and PWR models. In the BWR model, SHAP values at DoS = 0 display a wide spread, likely reflecting interactions with ECP (Fig. 10a) and/or YS (Fig. 10c). SHAP values generally increase with DoS under oxidizing ECP conditions and low YS (non-cold-worked SSs). In contrast, a few data points indicate that under reducing ECP and high YS (cold-worked SSs), SHAP values tend to decrease with increasing DoS. Because reducing ECP and high YS often co-occur, isolating the individual effects of ECP and YS on the DoS response remains challenging. In the PWR model, SHAP values generally decrease with DoS. Values remain elevated under more oxidizing conditions (Fig. 10b), suggesting an interaction effect between DoS and ECP. Interaction with YS is less conclusive (Fig. 10d), as sensitized specimens in the PWR dataset are also cold-worked, limiting interpretability. The negative correlation between DoS and CGR observed in the PWR model may be associated with high YS or cold work, consistent with trends from the limited cold-worked data in the BWR model.

The effects of κ differ between BWR and PWR environments (Supplementary Fig. 13). In BWR conditions, SHAP values show a pronounced positive correlation with κ, whereas in PWR conditions no clear pattern is observed. κ values are substantially lower in the BWR dataset due to trace-level impurity additions, while higher values in the PWR dataset result from intentional Li and B additions. This range difference may account for the contrasting κ effects in the two environments.

The effect of YS is broadly similar in both environments—positive in direction—but the dependence is less pronounced in BWR conditions (Supplementary Fig. 14). However, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion, as the weaker BWR dependence could still fall within the PWR vertical scatter. Notably, the BWR dataset contains only a limited number of high-YS (cold worked) data points, in contrast to the PWR dataset. This imbalance may also underlie the differing effect of orientation between BWR and PWR models (Supplementary Fig. 15): in BWR conditions, all orientations show little to no effect on CGR, with LR exhibiting a slightly larger—but still weak—impact, whereas in PWR conditions SL and TL orientations cause moderate acceleration in CGR—up to >0.8 in log scale (≈6.3× in linear scale)—compared to non-cold-worked (“0CW”) steels.

The effect of K appears consistent across BWR and PWR conditions (Supplementary Fig. 16), with both models showing a positive correlation and a sharp drop in SHAP values as K approaches the minimum values in each dataset, suggesting the presence of a threshold K (Kth)—likely < 10 MPa√m—below which crack growth does not occur. This threshold effect is more pronounced in the PWR model, possibly because the PWR dataset includes lower K values than the BWR dataset, with SHAP values dropping by more than 1.2 as K decreases below 30 MPa√m, corresponding to a ~16× deceleration in CGR in linear scale. The SHAP dependence for the cyclic loading factor fc suggests that even gentle cyclic loading conditions (fc > 1) could produce a modest acceleration in CGR—up to ~0.45 in log scale (≈2.8× in linear scale)—despite fc being only slightly greater than 1 (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Interestingly, material compositions show relatively narrow ranges of SHAP values, indicating weak effects on CGR in both BWR and PWR models. In the BWR model, Cr exhibits the highest mean SHAP magnitude among compositional features (Fig. 7c). However, Supplementary Fig. 18 suggests that the apparent Cr effect may instead reflect correlations with steel type rather than Cr itself. Because Cr varies more widely than Mo, Nb, or Ti in the dataset, the model may have attributed the small CGR differences associated with steel type to Cr.

Discussion

Prediction of IGSCC growth rates in austenitic SSs under BWR and PWR environments has traditionally relied on mechanistic and empirical models, each with limited applicability. For example, PLEDGE10 and CEFM14,15 were developed for BWR environments, with the latter restricted to sensitized Type 304 SSs. The FRI model21,22 can be extended for both BWR and PWR environments but requires extensive parameter calibration. Empirical models are also available for BWR environments, such as the BWR Vessel and Internals Project (BWRVIP)26, operating within narrow validity domains. Due to the scarcity of mechanistic models for PWR environments, empirical approaches have been increasingly relied upon, such as that provided in the Material Reliability Program report MRP-45827, which estimates CGR within defined material and environmental constraints.

Comparative results (Supplementary Fig. 19) show that CatBoost performs comparably to mechanistic models (e.g., PLEDGE and CEFM) under plant-relevant conditions and provides well-calibrated prediction bounds when combined with the proposed UQ approach (NLL loss and linear NLL calibration). Within their applicable domains, BWRVIP and MRP-458 yielded R² values of 0.273 and 0.540, and MAEs of 0.448 and 0.361, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 20), indicating substantially lower predictive accuracy compared to the ML models tested in this study. These findings highlight the potential of ML as a flexible and accurate alternative for CGR prediction, particularly as more high-quality data become available.

Despite uncertainties surrounding the exact mechanisms governing IGSCC growth in austenitic SSs, the mechanistic effects of certain features have been extensively studied. It is therefore important to assess whether the CatBoost model behavior aligns with existing domain knowledge. The observed increase in CGR with ECP in BWR (Fig. 8) and PWR (Supplementary Fig. 9) environments are consistent with the known role of ECP in promoting anodic dissolution at the crack tip. This occurs via two primary mechanisms: (1) increasing the electrochemical driving force for dissolution due to the potential difference between the crack tip and external crack surface14,15; and (2) promoting acidification at the crack tip38, thereby shifting conditions to be less thermodynamically favorable for passivity. However, as stated by Ford39, anodic dissolution (M → M⁺) may not be solely responsible for crack advance; rather, it is the overall oxidation reaction at the crack tip. When anodic dissolution is limited—e.g., due to low metal ion solubility—significant oxide film growth (M → MO) can also contribute to crack advance. The mechanical properties of this film are not well understood, but it is likely that at higher ECP the oxide is less protective and stable, making it more susceptible to fracture under the stress concentrated at the crack tip.

Interestingly, in BWR environments, at low or reducing ECP values, the ECP contribution appears to interact with DoS (Fig. 8a) and/or YS (Fig. 8b). The specific mechanisms underlying these interactions remain unclear, and additional data are required to isolate them. A few non-treated SS data points exhibited ECP trends consistent with those of sensitized SSs, showing lower contributions than high-YS steels. At low ECP, the overall crack-tip oxidation rate is reduced, likely due to both the lower driving force for anodic dissolution and the presence of a more protective oxide film under thermodynamically favorable conditions for passivity. Regarding the interaction between reducing ECP and YS, an experimental study40 reported that cold work can promote preferential grain-boundary oxidation under reducing ECP conditions, which may explain the elevated ECP contribution observed in the interaction effect for high-YS steels. However, this study examined smooth surfaces rather than crack tips, and thus may not fully capture the localized electrochemical and mechanical conditions governing crack growth.

T influences CGR through multiple pathways: it governs thermally activated processes such as diffusion and oxidation, while also modulating key features including YS, ECP, pH, and κ. For non-sensitized SSs, CGR generally increases with T in both BWR and PWR conditions (Fig. 9). In PWR conditions, the trend between 250 °C and 330 °C resembles Arrhenius behavior, indicating that CGR is dominated by thermally activated processes. Above 330 °C, however, CGR no longer increases with T, deviating from Arrhenius behavior and implying the emergence of a competing process with an opposing effect—possibly a mechanically controlled response. Meisnar et al.41 explained that at higher T, enhanced dislocation mobility relaxes strain gradients and reduces dislocation accumulation in the plastic zone. The reduced strain gradients also suppress vacancy accumulation ahead of the crack tip, mitigating void formation and embrittlement. This mechanical response could become dominant beyond a certain T, causing a decline in CGR. As shown in Fig. 9c, steels with higher YS are less prone to this CGR-declining behavior, as cold work reduces ductility and thus maintains higher strain gradients in the plastic zone, which attract dislocations and facilitate vacancy accumulation near the crack tip. Our results also show a deviation from Arrhenius behavior below ~250 °C, a less-studied regime that is relevant, particularly for stagnant regions or auxiliary systems in LWRs.

For sensitized SSs, non-Arrhenius behavior of CGR below 300°C has been observed in both BWR42 and PWR43 conditions, although underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In BWRs, especially under oxygenated high-ECP conditions, this has been attributed to interactions between T and the water chemistry, such as ECP and κ19. Indeed, Figure 8 shows high CGR sensitivity to small ECP shifts under oxidizing BWR conditions, and Supplementary Fig. 13a shows strong sensitivity of CGR to κ for most BWR data, likely including sensitized steels under oxidizing ECPs. However, this cannot explain the observed non-Arrhenius behavior under strongly reducing PWR conditions43, where ECP and κ have minimal effect on CGR (Supplementary Fig. 9b and Supplementary Fig. 13b). Moreover, Figure 9 shows that the SHAP values—representing the isolated marginal contribution of T—still exhibit a non-linear dependence on T across both BWR and PWR conditions, indicating that additional mechanisms are involved.

Sensitization increases materials’ susceptibility to intergranular corrosion due to Cr depletion at grain boundaries, which may explain the positive correlation between DoS and CGR under oxidizing ECP in BWR conditions (Fig. 10a). Interestingly, CGR decreases with increasing DoS at reducing ECP or in cold-worked SSs (Fig. 10a–d). Constant extension rate testing (CERT)44 also demonstrated a beneficial effect of sensitization in reducing IGSCC susceptibility of cold-worked SSs under reducing environments. The underlying mechanisms, however, remain poorly understood, and further investigation is warranted.

The effects of other key features also align with established mechanistic understanding. The observed increase in CGR with κ in BWR conditions (Supplementary Fig. 13a) can be attributed to enhanced throwing power, allowing oxidation current from crack tip metal dissolution to be balanced by redox reactions over a broader external surface area14,15. However, once κ exceeds a critical threshold, the rate-limiting step shifts to the kinetics of these redox reactions, and further increases in κ no longer enhance CGR14,15. The observed YS effect on CGR (Supplementary Fig. 14) can be attributed to its role in influencing crack-tip plastic strain. According to Shoji et al.21,22, higher YS constrains the plastic zone under a given K, resulting in steeper strain gradients and elevated local strain rates near the crack tip—conditions that promote IGSCC, as previously quantified experimentally (e.g.,45). Regarding orientation, experimental studies have also observed that CGR is consistently higher when the crack plane coincides with the forging or rolling plane27, such as in SL and TL orientations, which align with the observed finding (Supplementary Fig. 15). K determines the stress field and plastic zone size at the crack tip21,22. Higher K values increase stress concentration and plastic zone extent, thereby enhancing crack tip strain and facilitating crack propagation, consistent with the observed K effect on CGR (Supplementary Fig. 16). The existence of a threshold K is debated, as cracks may propagate even through low-K regions in real plant components6. Nevertheless, the presence of a threshold K indicated in the current study is supported by previous modeling and experimental work, which suggested a threshold in the range of ~7–11 MPa√m14,15,29,46,47. Finally, gentle cyclic loading is expected to modestly accelerate CGR relative to constant loading, consistent with the observed fc effect (Supplementary Fig. 17).

The SHAP analysis reveals generally consistent mechanistic trends for critical features across both BWR and PWR environments. However, notable differences in the magnitude of effects and feature interactions also emerge, largely due to data limitations—most notably sparsity in certain conditions and variations in feature distributions and dataset composition. As a result, while the overall CGR-driving mechanisms may share some similarities, applying a single mechanistic or traditional empirical model across both BWR and PWR environments is likely to be challenging; environment-specific parameterizations or adaptations are needed. Encouragingly, CatBoost already demonstrates strong predictive performance on the combined dataset, highlighting its robustness in capturing complex behavior across diverse reactor environments without requiring explicit mechanistic tuning for each.

Several assumptions used in this study are worth discussing. YS was predicted using a CatBoost model trained on an external database compiled by the Material Algorithm Project (MAP)48, and extended to cold-worked conditions through an empirical correlation described in Eq. (2) of the Methods. A substantial portion of the MAP dataset (1372 out of 2180 entries) was excluded, primarily due to unspecified heat treatments. Although such large exclusions may appear concerning, they were necessary as imputation was not feasible. Unlike the IGSCC growth rate dataset—where conservative imputation of heat treatment conditions is reasonable since tested specimens can be assumed fully recrystallized with complete carbide dissolution—the MAP dataset encompasses diverse heat treatments, including conditions that result in incomplete recrystallization and carbide dissolution. A cross-validation experiment confirmed that YS can still be predicted accurately despite the reduced dataset size (Supplementary Fig. 21a). Comparable exclusions have also been applied in previous modeling studies using this database49,50.

The adopted approach does not explicitly account for the sequence in which cold work is applied before testing; however, assuming that the effect of cold work on YS is independent of test temperature, the experimental sequence can reasonably be ignored. Sensitization is also not considered, although its effect on YS has been reported to be relatively small (<10–15%)43. The empirical correlation also omits other parameters relevant to cold work, such as deformation temperature, deformation mode (e.g., rolling, forging), and strain rate, which may further influence YS. Despite these limitations, the method performed well when tested on a subset of the IGSCC growth rate database with known YS (Supplementary Fig. 21b), providing confidence in the predicted YS values.

As detailed in Methods, several assumptions and approximations were also made in estimating electrochemical features. In the absence of detailed impurity information, NaCl was assumed as the representative impurity, and its concentration was inferred from reported room-temperature κ. This estimate was then used to calculate solution κ and pH at test temperatures. While this approach offers a consistent and physically reasonable basis for these estimates, it inevitably introduces uncertainty due to the unknown nature of actual impurities. For ECP estimation, the mixed potential model (MPM) developed by Macdonald15,51, originally formulated for sensitized Type 304 SS under BWR conditions—was applied to other non-sensitized austenitic SSs. Due to the lack of reported flow velocities and hydrodynamic diameters in many sources, representative values were assumed for ECP computation, which may introduce additional uncertainty. Nevertheless, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, the predicted ECP values for various austenitic SSs and environments agree well with experimental measurements, supporting the applicability of the MPM across the database.

The cyclic loading factor fc, computed from cyclic loading parameters (see Methods), allowed the model to differentiate between gentle cyclic and constant loading conditions, capturing the general acceleration effect of gentle cyclic loading on CGR. However, it was derived from crack tip strain rates under fatigue loading, which may not precisely reflect those under gentle cyclic loading. As a result, the magnitude value of fc does not directly indicate proportional changes in CGR—for example, an fc of 1.2 does not necessarily mean CGR is 20% faster than under constant load. This limits mechanistic interpretability of fc in quantifying the effect of gentle cyclic loading.

Next, we discuss the model implementations used in this study. In particular, the models were trained with limited to no hyperparameter tuning: CatBoost and NGBoost were used with default settings, and TabNet underwent only limited tuning, where only batch size and virtual batch size were adjusted. CatBoost’s default hyperparameters are generally well chosen and have frequently been shown to perform robustly33,52. While additional tuning may provide some improvement, it is unlikely to yield substantial gains and could increase the risk of overfitting given our relatively small dataset (<1000). For NGBoost, tuning is challenging because there is a trade-off between point estimate accuracy and uncertainty estimate reliability. The inferior performance of NGBoost in point estimate accuracy compared to CatBoost and GPR may indicate a need for hyperparameter tuning; however, improving accuracy could compromise uncertainty estimates. Therefore, the default settings were retained as a reasonable baseline, consistent with a prior comparative study53. For TabNet, tuning other hyperparameters—such as learning rate, number of decision steps, attention dimensions, sparsity regularization, and gradient clipping—may be beneficial, but was not systematically explored here. GPR was used with a predetermined kernel combination (additive Matern, White, and Dot Product kernels). While this combination is physically suitable for this work, exploring alternative kernel structures may further improve performance. Given that NGBoost, TabNet and GPR were included primarily for comparison, the chosen settings provide a fair basis for benchmarking.

Despite some limitations, this study demonstrates the potential of the ML-based framework to significantly enhance IGSCC growth rate modeling in LWRs. By incorporating a proper UQ approach, this framework enables cautious and informed decision-making for risk assessment and plant safety evaluations. Moreover, UQ is critical for regulatory compliance and industry adoption, where conservative safety margins are required. The model’s explainability enhances transparency, allowing verification against established domain knowledge and facilitating the discovery of new insights that may inspire future mechanistic research. Given these strengths, the framework is well-positioned for real-world application in IGSCC growth rate modeling, while offering a scalable methodology for broader use in material degradation modeling and structural integrity assessments in LWRs.

Methods

Database establishment

To build the IGSCC growth rate database, we reviewed numerous published papers3,32,38,39,42,43,45,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102, reporting results from laboratory tests conducted under simulated reactor environments. Values presented in tables were directly extracted, while those available only in graphical format were digitized using WebPlotDigitizer103.

The primary criterion for the data screening is based on the following correlation:

where \({B}_{{eff}}\) and \(W\) are, respectively, the specimen effective thickness and width, \(a\) is the crack length, \({f}_{K}\) is a factor term, \(K\) is the stress intensity factor, and \({\sigma }_{{ys}}\) represents the specimen yield strength (YS). This criterion ensures that the measured CGR exhibits the linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) behavior, based on the \(K\)/specimen size criterion of various standards67,104,105,106. Although \({f}_{K}\) = 2.5 is recommended67,106, this value is often overly conservative especially for annealed or sensitized SSs; hence, a lower value of 1.27 (or \(4/\pi\)) is sometimes permitted67,104,105. Additionally, the flow stress can sometimes be used in place of YS for \({\sigma }_{{ys}}\)67,105. For cold-worked SSs, increasing cold work reduces the conservatism of the \(K\)/specimen size criteria67. Therefore, during data screening, the material condition (annealed or cold-worked) was taken into account when selecting the appropriate \({f}_{K}\) value. In addition, each data point was evaluated individually to assess whether the CGR behavior conformed to LEFM, particularly when inconsistencies among standards were encountered; a CGR value within a typical range for the given conditions was considered to satisfy LEFM criteria.

Beyond the LEFM criterion, data lacking variables considered essential that could not be reliably estimated were excluded. These include a few data points missing information on electrochemistry-related variables—such as electrochemical potential (ECP), solution pH, conductivity (κ), and dissolved gas or impurity concentrations. While ECP, pH, and κ could be estimated, estimation is not possible if dissolved gas or impurity concentrations are unknown. Additionally, some data did not report crack orientation relative to the direction of externally applied plastic deformation (i.e., cold work). The collected raw data with unprocessed variables are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

The first step of data preprocessing was to ensure consistency and comparability across studies by harmonizing all variables in units prior to modeling. This included CGR, K, YS, degree of sensitization (DoS), test temperature, dissolved gas concentrations, and ECP, which were reported in varying units. For example, CGR was standardized to mm/s, K to MPa√m, and temperature to °C. DoS required particular attention due to inconsistent reporting: some studies reported it as normalized reactivation charge (in C/cm²) from single-loop EPR tests, while others used the Ir/Ia ratio from double-loop EPR tests. Since more sensitized steel data were reported in C/cm² than as Ir/Ia ratios, all DoS values were harmonized to this unit. Additionally, the mechanistic effect of DoS on CGR has historically been studied using C/cm². Conversion of Ir/Ia to C/cm² was performed using the fitted line presented by Majidi et al.107, which plotted DoS in both units. In cases of significant discrepancies in Ir/Ia values for steels with comparable carbon content, sensitization time, and temperature across multiple sources, expert judgment and prior studies108,109 were used to select the most plausible value.

The next step of data preprocessing was to handle missing values among input variables or features, which was performed based on data completeness and feature importance (according to the known knowledge domain). Chemical elements with significant missingness (>50%) and considered to have minimal influence on IGSCC propagation, such as copper and cobalt, were removed. Nitrogen content was retained, as prior work110 showed that it can affect the susceptibility of materials to SCC. Niobium and titanium were largely missing in Types 304 and 316 SS, which make up most of the dataset, but are important indicators of Types 347 and 321 SS and therefore were not removed. For missing minority chemical contents, such as molybdenum in Types 304, 347, or 321; niobium and titanium in Types 304 or 316; or nitrogen in low-nitrogen heats, a low value of 0.001% was imputed to represent trace content. Similarly, unreported minority dissolved gas concentrations (e.g., hydrogen in oxygenated water) were filled with a constant of 1 ppb, reflecting trace background levels. When material composition was not reported, content values were inferred from the mean of the corresponding alloy type in the MAP database48, which contains a diverse set of SS heats. For example, missing values in Type 304 L SS were replaced with the mean composition of 304 L heats in the MAP dataset. For missing heat treatment parameters, i.e., solution annealing temperature and time, 1050 °C for 60 min was conservatively selected for imputation, to account for the requirements for full recrystallization and carbide dissolution. For DoS, missing values were estimated from sensitization temperature and time by referencing steels with comparable carbon contents and sensitization conditions in the selected dataset with reported DoS and in other studies108,109.

Missing values for YS, which reflects the extent of cold work (or applied deformation), were estimated using a CatBoost model built using the MAP database. The original dataset contained 2180 instances, but 1371 were excluded due to missing values for critical metallurgical descriptors (solution treatment time, temperature, and quenching method) to ensure physically consistent modeling of YS. One instance reporting an unusually low ultimate tensile strength (UTS < 50 MPa) at ~600 K, judged to be erroneous, was also excluded. The remaining 808 data points were used for YS modeling and are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Cross-validation on this filtered dataset using CatBoost with default hyperparameters indicates that YS can be predicted accurately (R2 = 0.944 ± 0.007; MAE = 7.499 ± 0.288), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 21a. CatBoost was then trained on the entire filtered dataset (808 entries) to obtain the YS model.

CatBoost trained on the filtered MAP dataset could only predict YS for non-cold-worked SSs. No dataset of sufficient size with complete metallurgical descriptors exists for ML modeling of the cold-work effect on YS. Therefore, we adopted an empirical correlation from MRP-45827, developed to quantify the effect of cold work on YS using a limited dataset, originally expressed as:

where \(\% {\rm{CW}}\) is cold work level and \(255.7\) represents the non-cold-worked YS (likely at room temperature). In this work, 255.7 is replaced with the CatBoost-predicted YS, allowing the cold-worked YS to depend on alloy composition, metallurgical treatments, and test temperature. We tested the accuracy of the adopted approach on a subset of the IGSCC growth rate database with known YS, treated as a held-out test set, and obtained good agreement with R2 = 0.936 and MAE = 44.756, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 21b.

Key electrochemical features, such as solution pH, κ, and ECP, were also largely missing or reported only at room temperature. The pH and κ values at test temperature (T) were estimated by calculating the concentrations of chemical species in solution, accounting for their dissociation and fundamental principles such as electroneutrality and mass balance. Details and validation of this approach are available elsewhere28,111,112. In cases where the reported room temperature κ exceeded that of pure water but the exact composition was unknown—particularly in BWR cases—it was assumed to result from a common trace impurity in reactor coolant, namely NaCl. Its concentration was then estimated, allowing computation of the test temperature κ and pH. The ECP was estimated using the mixed potential model (MPM) developed by Macdonald15,51, which accounts for T and the concentrations of \({{\rm{H}}}^{+}\), \({{\rm{O}}}_{2}\), \({{\rm{H}}}_{2}\), \({{\rm{H}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}\), flow velocity, and pipe hydrodynamic diameter. Flow velocity and pipe hydrodynamic diameter, rarely reported in the sources, were consistently assumed to be 100 cm/s and 50 cm, respectively, following the assumptions adopted in the original MPM15. Although experimental loop hydrodynamic conditions may vary, the assumed values yield a Reynolds number on the order of 10⁶, which is within the typical range of turbulent flow conditions observed in laboratory-scale loop systems51. This approach was validated against experimental measurements for various austenitic SSs and environments, obtained from both the curated IGSCC dataset with known ECP and external sources51,111,113,114,115, showing good agreement (see Supplementary Fig. 22).

Data from “gentle” cyclic loading conditions, typically involving very low frequencies (≤0.001 Hz) and/or long hold times between cycles, were also included. These conditions are often used to measure CGR when crack growth is difficult to generate under constant loading, such as at low temperatures42, high-purity water32, or in non-treated (sensitized or cold-worked) materials62. To quantify the effect of gentle cyclic loading, we defined a factor, \({f}_{c}\), computed as:

[where \(v\) and \(R\) are the load frequency and load ratio, respectively. The term \({t}_{h}\) is the hold time between cycles, while \({A}_{R}\) is a function of \(R\), computed as:

For cyclic loading, \({f}_{c}\) was determined based on the crack tip strain rate given by Andresen and Ford10. For trapezoidal loading (or periodic partial unloading), \({f}_{c}\) was determined using an approximation of average crack tip strain rate during rise time (i.e., \(1/2v\)) and \({t}_{h}\). Under gentle cyclic conditions yielding \({f}_{c} < 1\), \({f}_{c}\) was set to 1.

Several features in the raw dataset (Supplementary Table 1) were excluded because their effects were already represented by retained inputs. For cyclic loading, the stress intensity factor at maximum loading was retained, as it corresponds to K under constant loading conditions, whereas R, v, and th were excluded since their influence is captured by fc. Concentrations of dissolved oxygen, hydrogen, and hydrogen peroxide were omitted because they were used as inputs in the calculation of ECP. Sulfate and chloride concentrations were also excluded, as their effects are captured by the calculated pH and κ at T. Lithium (Li) and boron (B) concentrations were retained due to their effect on crack growth behavior in Alloy 600 under PWR environments, as demonstrated in previous modeling work30. Heat treatment parameters and cold work were omitted because their influence is represented by YS and by crack orientation relative to the applied deformation (as previously defined, orientation). Sensitization conditions were excluded, with DoS representing their effect. This reduced set of variables preserves the main physical factors relevant to CGR while minimizing redundancy.

To mitigate the differences in typical κ values between BWR and PWR environments, κ was log-transformed. The CGR was also transformed to a logarithmic scale due to the wide range of its values, spanning ~10−10 to 10−6. Furthermore, CGR is often assumed to follow a log-normal distribution116,117,118, where the mean (μ)—used as the best point estimate—is defined on the log scale., providing additional justification for using the logarithm of CGR as the modeling target.

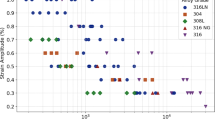

Following rigorous data screening and preprocessing, we established a database comprising 978 data points with 22 selected features. These include mechanical loading parameters (K and fc), environmental conditions (Li, B, T, along with ECP, pH, and κ, all evaluated at T), and material-related variables (chemical composition, YS at T, and orientation). Most features are numerical, except orientation, which is categorical. The dataset is divided into two categories, i.e., BWR (537 instances) and PWR (441 instances), classified by the presence of Li, which reflects the water chemistry and system type. The BWR data include mostly constant loading tests with some gentle cyclic loading (64 instances), involving various heats of Types 304, 316, 347, and 321 SSs. The PWR data consist solely of constant loading tests on Types 304 and 316 SSs. A summary of the database is provided in Table 1.

Model description

To learn from the database and predict the IGSCC growth rate, we employed the categorical boosting (CatBoost) algorithm, developed by Prokhorenkova et al.36. For comparison, several other ML models were evaluated, including natural gradient boosting (NGBoost)119, Gaussian process regression (GPR)120, and TabNet121.

CatBoost utilizes the gradient boosting technique122, in which multiple base predictors (i.e., decision trees) are built sequentially, with each new model correcting the errors of its predecessors. Given a dataset with a feature vector \(x\) and a target variable \(y\), the CatBoost prediction of the \(t\)-th iteration for the \(i\)-th instance, \({\hat{y}}_{i}^{t}\), can be expressed as:

where \({\hat{y}}_{i}^{t-1}\) is the previous prediction, \(\alpha\) is the step size (i.e., learning rate), and \({f}^{t}({x}_{i})\) is the \(t\)-th predictor for the \(i\)-th instance. Each predictor is trained to predict the negative gradient of the loss function (i.e., residuals) from the previous iteration.

A key feature of CatBoost is its innovative ordered boosting technique, which constructs training subsets using random permutations of the dataset36. For each data point, the residual is computed using models trained only on earlier examples in the permutation. This design prevents the model from accessing its own target during training, thereby eliminating target leakage and mitigating prediction shift, an issue commonly encountered in conventional gradient boosting algorithms. CatBoost also handles categorical features using ordered target statistics, which assign target-based encodings to each instance based only on prior data points, further avoiding information leakage.

In this study, the CatBoost Python package36,123 with default hyperparameters (learning_rate = 0.03, depth = 6, l2_leaf_reg = 3, iterations = 1000, etc.) was used. The package supports various loss functions, which can be selected according to the prediction task. For point predictions, the root mean squared error (RMSE) loss is the default setting, defined as:

where \({y}_{i}\) and \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) are the true and predicted target values of \(i\)-th instance in the dataset, and \(n\) denotes the number of instances in the dataset. For uncertainty quantification (UQ), CatBoost supports the negative log-likelihood (NLL, also termed “RMSEwithuncertainty”) and quantile losses. The NLL loss assumes a Gaussian target distribution and enables estimation of both the predicted mean and standard deviation of CGR, expressed as:

The term \({\mathscr{N}}\left({y}_{i},|,{\hat{\mu }}_{i},{\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\right)\) denotes the likelihood, i.e., the value of the normal probability density function evaluated at the observed target \({y}_{i}\), given the predicted mean \({\hat{\mu }}_{i}\) and standard deviation \({\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\). In practice, \({\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\) is reparameterized as \(\log {\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\) during training to ensure positivity and improve numerical stability. The quantile loss is written as:

where \({\rm{ {\mathbb{I}} }}\left(\cdot \right)\) is the indicator function. Models trained with quantile loss provide the lower and upper prediction bounds—typically the \(\alpha /2\) and \(1-\alpha /2\) quantiles of the target variable, denoted \({\hat{y}}_{\alpha /2}\) and \({\hat{y}}_{1-\alpha /2}\), respectively.

NGBoost is an algorithm designed to generate a full conditional probability distribution using the gradient boosting framework119. The key innovation in NGBoost lies in its use of natural gradients, which consider the geometry of the distribution space, ensuring that each update reflects a consistent and meaningful change in the predictive distribution, regardless of parameterization. The loss function, typically a proper scoring rule, is NLL. NGBoost was implemented using the open-source NGBoost Python package119,124. Assuming a normal distribution as the predictive distribution, default hyperparameter values from the official implementation were used: iterations = 500, learning_rate = 0.01, BaseEstimator=DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth = 3), and col_sample = 1.0.

GPR is a probabilistic model for regression within a Bayesian framework120. It produces both a mean prediction and an associated variance under the assumption of a Gaussian distribution, thereby naturally capturing uncertainty arising from data sparsity or variability in underlying patterns. To model the structure of the data, GPR relies on kernel functions, which compute the covariance between input points. In this study, GPR was implemented using the scikit-learn Python package125, with a composite kernel of C(1.0) * Matern + WhiteKernel + C(1.0) * DotProduct. The Matérn kernel captures smooth nonlinear interactions with tunable length scales, the White kernel accounts for observation noise by adding variance to the diagonal of the covariance matrix, and the Dot Product kernel models linear trends between features and the target. The multiplicative constant kernels (C) provide variance scaling, allowing greater flexibility in model fitting. This kernel structure, which has also been employed in prior work53, allows the model to capture diverse relationships between features and the target variable. Kernel hyperparameters (length scales, variances, and noise level) were optimized automatically during training by maximizing the log-marginal likelihood, with n_restarts_optimizer = 8 to reduce sensitivity to local optima. Targets were standardized (normalize_y = True) and a small jitter term (alpha = 1e−6) was added for numerical stability.

TabNet is a deep learning model designed for point estimation on tabular data, using sequential attention to dynamically select relevant features, enabling efficient learning and reducing overfitting121. TabNet was implemented using the pytorch-tabnet package126. As with other deep learning models, TabNet requires hyperparameter tuning; therefore, batch size and virtual batch size were optimized via an exhaustive grid search (batch size: [128, 64, 32]; virtual batch size: [64, 32, 18]), following the recommendation that setting batch size to ~1–10% of the training set size may be beneficial for training stability and performance121. The maximum number of training epochs (max_epochs) was set to 500 to ensure convergence. All other hyperparameters were retained at their default values (learning_rate = 0.02, n_d = 8, n_a = 8, n_steps = 3, gamma = 1.3, lambda_sparse = 1e−3, clip_value = 2.0) with the Adam optimizer.

Post-hoc calibration for UQ

As previously mentioned, CatBoost can provide uncertainty estimates when trained with NLL or quantile losses. However, these initial estimates may be poorly calibrated. To address this, we applied post-hoc calibration to CatBoost models, using a calibration set separate from the training data to compute correction factors or calibration parameters for the uncertainty estimates produced by the trained model.

CatBoost models trained with NLL loss produce both predicted mean \(\hat{\mu }\) and standard deviation \(\hat{\sigma }\) as a measure of uncertainty. Following the method of Palmer et al.127, calibration assumes a linear relationship between the uncalibrated \(\hat{\sigma }\) and the corrected \({\hat{\sigma }}^{{cal}}\), expressed as \({\hat{\sigma }}^{{cal}}=a\hat{\sigma }+b\). The parameters \(a\) and \(b\) are computed by minimizing the following NLL over the calibration set of size \({n}_{{cal}}\):

where \({y}_{i}\) is assumed to be drawn from a normal distribution with mean \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) and standard deviation \(a{\hat{\sigma }}_{i}+b\).

Similarly, models trained with quantile loss yield lower and upper prediction bounds \(\left({\hat{y}}_{\alpha /2},{\hat{y}}_{1-\alpha /2}\right)\), corresponding to the \(\alpha /2\) and \(1-\alpha /2\) quantiles of the target variable. These bounds were calibrated using the conformal prediction (CP) method. The conformity score for the \(i\)-th calibration point, which measures how far the true value \({y}_{i}\) lies outside the predicted interval, is defined as \({s}_{i}=\max \left({\hat{y}}_{(\alpha /2),i}-{y}_{i},\,{y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{(1-\alpha /2),i}\right)\). After computing these scores, the \(\left(1-\alpha \right)\) quantile of the scores, denoted \({q}_{1-\alpha }\), is used to expand the predicted interval for unseen data as \(\left({\hat{y}}_{\alpha /2}-{q}_{1-\alpha },\,{\hat{y}}_{1-\alpha /2}+{q}_{1-\alpha }\right)\). This approach is commonly known as conformalized quantile regression128.

Model training and validation

K-fold cross-validation was employed to ensure objective evaluation of model performance. In this method, the dataset is partitioned into K approximately equal subsets or folds. The model is iteratively trained on K − 1 folds and validated on the remaining fold, with each fold used for validation once. This yields K performance estimates, helping to mitigate bias from data splitting. Within this framework, two training modes were considered: (i) separate training on the BWR and PWR datasets, with constant-value features removed as they provided no information, and (ii) training on the combined BWR–PWR dataset, where all features were retained. Identical fold assignments were maintained across all evaluation schemes. Among the models, only TabNet required manual tuning, where batch size and virtual batch size were optimized using an internal 80/20 split of the training folds. After tuning, the model was retrained on the full set of training folds, while the validation fold was reserved exclusively for performance assessment, ensuring no data leakage. All cross-validation procedures were implemented using the scikit-learn Python library125.

During model training, feature scaling and/or encoding was required for models other than CatBoost. Feature scaling was applied to GPR using MinMaxScaler from the scikit-learn package125, rescaling all numerical features to the [0, 1] range. For NGBoost and GPR, the categorical variable orientation was encoded using one-hot encoding, which creates binary indicator variables for each category, setting the indicator of the active category to 1 and all others to 0. For TabNet, categorical encoding was performed using label encoding, which assigns a unique integer to each category.

To enable post-hoc calibration for UQ in CatBoost, an internal 80/20 split of the training folds was performed: 80% was used to train the base predictive model and compute initial uncertainty estimates, while 20% served as a calibration set. This calibration set was then used to compute correction parameters (e.g., linear scaling factors \(a\) and \(b\) for NLL, or conformity scores \(s\) for CP) without influencing the initial model fit. The model was subsequently retrained on the full training set, and the same calibration parameters were applied to generate final uncertainty estimates. Although post-hoc calibration methods are theoretically intended to adjust uncertainty estimates without retraining, retraining was found to improve point estimate accuracy without compromising the reliability of the uncertainty estimates.

Model evaluation metrics

To quantify the accuracy of model prediction, evaluation metrics including the coefficient of determination (\({{\rm{R}}}^{2}\)) and mean absolute error (\({\rm{MAE}}\)) were used. \({{\rm{R}}}^{2}\) measures the proportion of target variance that can be explained by the model, and can be computed as:

where \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) and \({y}_{i}\) are, respectively, the predicted and actual values of the target variable for the \(i\)-th observation. The symbol \(\bar{y}\) is the average of actual target values across all \(n\) observations. The term \({\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{\left({\hat{y}}_{i}-{y}_{i}\right)}^{2}\) and \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}{\left(\bar{y}-{y}_{i}\right)}^{2}\) reflect the target variance unexplained by the model and total target variance, respectively.

\({\rm{MAE}}\) can be computed as:

Since the values of our target variable (i.e., CGR) were on a logarithmic scale, \({\rm{MAE}}\) corresponds to the geometric-mean multiplicative error—a representative factor by which predicted CGRs differ from measured values on a linear scale.

For UQ, empirical coverage was used to assess the reliability of the predicted confidence intervals. It is defined as the proportion of true target values that fall within the predicted interval. A well-calibrated model should yield empirical coverage close to the nominal level (e.g., 95%). Overconfident models tend to under-cover, while underconfident models tend to over-cover.

Shapley additive explanations

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), proposed by Lundberg and Lee129, is based on Shapley values from cooperative game theory, which fairly distribute a total payoff among players based on their marginal contributions across all possible coalitions. In ML, the players correspond to features in the data, and Shapley values quantify their contributions to the model’s output.

SHAP explains a prediction from a complex ML model via an additive feature attribution formulation, typically written as:

where \(f\left(x\right)\) is the original model’s prediction, and \(g\left({z}^{{\prime} }\right)\) is the surrogate explanation model. The term \({z}^{{\prime} }\in {\left\{\mathrm{0,1}\right\}}^{N}\) is a feature coalition vector with a size of \(N\), where \({z}_{i}^{{\prime} }=1\) if the \(i\)-th feature is present and 0 otherwise. The term \({\phi }_{0}\) is the base value (the model’s output when all features are “missing”), while \({\phi }_{i}\) is the Shapley value, also called SHAP value, of the \(i\)-th feature. SHAP employs various efficient techniques to compute the SHAP values, depending on the type of model being explained. In the current work, we employed TreeSHAP37, which accurately computes SHAP values for tree-based models while significantly reducing computational cost.

Data availability

The datasets used for modeling in this study can be found in the cited literature. The processed and generated data in this study are not publicly available as they are part of ongoing research, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Nuclear Performance Report 2024. https://world-nuclear.org/our-association/publications/global-trends-reports/world-nuclear-performance-report-2024 (2024).

Reference Data Series - Nuclear Power Reactors in the World. https://www.iaea.org/publications/15748/nuclear-power-reactors-in-the-world (2024).

Andresen, P. L, Angeliu, T. M., Young, L. M., Catlin, W. R., Horn, R. M. Mechanisms and kinetics of SCC in stainless steels. In 10th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems-Water Reactors (NACE, 2001).

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Comparison of Boiling Water Reactor and Pressurized Water Reactor Experience with Cracking of Austenitic Stainless Steel. https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1814/ML18142A237.pdf (2018).

Weeks, R. W. Stress Corrosion Cracking in BWR and PWR. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems–Water Reactors (NACE, 1984).

Ehrnstén, U., Andresen, P. L. & Que, Z. A review of stress corrosion cracking of austenitic stainless steels in PWR primary water. J. Nucl. Mater. 588, 154815 (2024).

Stress Corrosion Cracking in Light Water Reactors: Good Practices and Lessons Learned. https://www.iaea.org/publications/8671/stress-corrosion-cracking-in-light-water-reactors-good-practices-and-lessons-learned (2011).

Zhai, Z. Light Water Reactor Sustainability Program - Preparation for Stress Corrosion Crack Initiation Testing of Austenitic Stainless Steels in PWR Primary Water. https://lwrs.inl.gov/content/uploads/11/2024/03/StressCorrosionCrackInitiationTestingAusteniticSS_PWR.pdf (2023).

Rudland, D., Leech, M., Homiack, M. & Nellis, C. Risk-informed assessment of french stress corrosion cracking operational experience relative to the fleet of pressurized water reactors in the United States of America. In Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference vol. 88476, V001T01A074 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2024).

Andresen, P. L. & Peter Ford, F. Life prediction by mechanistic modeling and system monitoring of environmental cracking of iron and nickel alloys in aqueous systems. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 103, 167–184 (1988).

Andresen, P. L. & Ford, F. P. Use of fundamental modeling of environmental cracking for improved design and lifetime evaluation. J. Press Vessel Technol. 115, 353–358 (1993).

Logan, H. L. Film-rupture mechanism of stress corrosion. J. Res. Natl Bur. Stand 48, 99–105 (1952).

Ford, F. P. Mechanisms of environmental cracking in systems peculiar to the power-generation industry. Final Report. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6752626 (1982).

MacDonald, D. D. & Urquidi-MacDonald, M. A coupled environment model for stress corrosion cracking in sensitized type 304 stainless steel in LWR environments. Corros. Sci. 32, 51–81 (1991).

Macdonald, D. D., Lu, P.-C., Urquidi-Macdonald, M. & Yeh, T.-K. Theoretical estimation of crack growth rates in type 304 stainless steel in boiling-water reactor coolant environments. Corrosion 52, 768–785 (1996).

Evans, U. R., Bannister, L. C. & Britton, S. C. The velocity of corrosion from the electrochemical standpoint. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 131, 355–375 (1931).

Briant, C. L. Hydrogen assisted cracking of type 304 stainless steel. Metall. Trans. A 10, 181–189 (1979).

Shen, C. H. & Shewmon, P. G. A mechanism for hydrogen-induced intergranular stress corrosion cracking in alloy 600. Metall. Trans. A 21, 1261–1271 (1990).

Vankeerberghen, M. & Macdonald, D. D. Predicting crack growth rate vs. temperature behaviour of Type 304 stainless steel in dilute sulphuric acid solutions. Corros. Sci. 44, 1425–1441 (2002).

Shi, J., Fekete, B., Wang, J. & Macdonald, D. D. Customization of the coupled environment fracture model for predicting stress corrosion cracking in Alloy 600 in PWR environment. Corros. Sci. 139, 58–67 (2018).

Shoji, T., Suzuki, S. & Ballinger, R. G. Theoretical prediction of SCC growth behavior – threshold and plateau growth rate. In Seventh International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems–Water Reactors 881–891 (NACE International, 1995).

Shoji, T., Lu, Z. & Murakami, H. Formulating stress corrosion cracking growth rates by combination of crack tip mechanics and crack tip oxidation kinetics. Corros. Sci. 52, 769–779 (2010).

Scott, P. M. An Analysis of Primary Water Stress Corrosion Cracking in PWR Steam Generators (IAEA, 1991).

Crack Growth Rates for Evaluating Primary Water Stress Corrosion Cracking (PWSCC) of Thick-Wall Alloy 600 Material (MRP-55) (Electric Power Research Institute, 2002).

Materials Reliability Program: Crack Growth Rates for Evaluating Primary Water Stress Corrosion Cracking (PWSCC) of Alloy 82, 182, a Nd 132 Welds (MRP-115) (EPRI, 2004).

Carter, R. & Pathania, R. Technical basis for BWRVIP stainless steel crack growth correlations in BWRs. In ASME Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference vol. 42843, 327–336 (ASME, 2007).

Materials Reliability Program: Stress Corrosion Crack Growth Rates in Stainless Steels in PWR Environments (MRP-458). www.epri.com (2022).

Lu, P. The Deterministic and Non-deterministic Models for the Predictions of Crack Growth Rates of Type 304 Stainless Steel. Ph.D. Thesis (Pennsylvania State University, United States, 1994).

Shi, J., Wang, J. & Macdonald, D. D. Prediction of crack growth rate in Type 304 stainless steel using artificial neural networks and the coupled environment fracture model. Corros. Sci. 89, 69–80 (2014).

Shi, J., Wang, J. & Macdonald, D. D. Prediction of primary water stress corrosion crack growth rates in Alloy 600 using artificial neural networks. Corros. Sci. 92, 217–227 (2015).

Wang, P., Wu, H., Liu, X. & Xu, C. Machine learning-assisted prediction of stress corrosion crack growth rate in stainless steel. Crystals 14, 846 (2024).

Peter, L. A. IGSCC Crack Propagation Rate Measurement in BWR Environments. Executive Summary of a Round Robin Study. https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/servlets/purl/337268 (1998).

Mamun, O., Wenzlick, M., Sathanur, A., Hawk, J. & Devanathan, R. Machine learning augmented predictive and generative model for rupture life in ferritic and austenitic steels. Npj Mater. Degrad. 5, 20 (2021).

Gackowska-Kątek, M. & Cofta, P. Explainable machine learning model of disorganisation in swarms of drones. Sci. Rep. 14, 22519 (2024).

Fajrul Falaakh, D., Cho, J. & Bum Bahn, C. Machine learning approach for predicting and understanding fatigue crack growth rate of austenitic stainless steels in high-temperature water environments. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 133, 104499 (2024).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 31, (NIPS, 2018).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Ford, F. P., Taylor, D. F., Andresen, P. L. & Ballinger, R. G. Corrosion-Assisted Cracking of Stainless and Low-Alloy Steels in LWR (Light Water Reactor) Environments: Final Report. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6683579 (1987).

Ford, F. P. Quantitative prediction of environmentally assisted cracking. Corrosion 52, 375–395 (1996).

Lozano-Perez, S., Kruska, K., Iyengar, I., Terachi, T. & Yamada, T. The role of cold work and applied stress on surface oxidation of 304 stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 56, 78–85 (2012).

Meisnar, M., Vilalta-Clemente, A., Moody, M., Arioka, K. & Lozano-Perez, S. A mechanistic study of the temperature dependence of the stress corrosion crack growth rate in SUS316 stainless steels exposed to PWR primary water. Acta Mater. 114, 15–24 (2016).

Andresen, P. L. Effects of temperature on crack growth rate in sensitized type 304 stainless steel and alloy 600K. Corrosion 49, 714–725 (1993).

Morton, D., West, E., Moss, T. & Newsome, G. The Temperature functionality of sensitized stainless steel SCC growth in deaerated water. In Proceedings of 20th International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems – Water Reactors (AMPP, 2022).