Abstract

Radiation-induced segregation (RIS) is a non-equilibrium phenomenon that can significantly alter local composition and degrade material properties. Although extensive research has focused on RIS near grain boundaries, much less attention has been given to RIS near nanosized cavities, including voids and gas-filled bubbles, which are primary contributors to material swelling. Compared with grain boundaries, cavities exhibit unique characteristics as defect sinks, such as spherical geometry, potentially higher density, and shorter distances between sinks. Although conventional one-dimensional (1D) models can capture basic features of RIS near isolated cavities, our calculations showed that they failed to reproduce experimental RIS profiles near closely spaced bubbles, an arrangement commonly observed in irradiated materials due to heterogenous bubble nucleation. In this study, we combined two-dimensional (2D) simulations with atom probe tomography (APT) experiments to investigate RIS near helium bubbles in a Ni50Fe50 model alloy. The 2D simulations achieved good agreement with the experimental data. Moreover, we identified a non-linear coupling effect between neighboring bubbles: Ni segregation between two bubbles was higher than that from a single bubble, but lower than the linear sum of two isolated bubbles. These results demonstrate that the 2D RIS model is essential for simulating complex RIS behavior near cavities, thereby enabling more accurate predictions of microstructural evolution and property changes in materials under extensive irradiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Irradiation of materials can cause the segregation of alloying elements near point defect sinks, such as grain boundaries (GBs), dislocations, and cavities. This non-equilibrium phenomenon, known as radiation-induced segregation (RIS), occurs when solute atoms preferentially couple with fluxes of interstitials or vacancies migrating towards sinks1. RIS has been extensively studied near GBs through experimental and modeling approaches2,3,4,5,6. However, only a few studies have focused on RIS near nanosized cavities, including voids and bubbles, which are commonly observed in materials under extreme environments, such as intense radiation, high strain rates, and elevated temperatures. In particular, cavity formation is the primary reason for radiation-induced swelling, a key degradation mechanism for nuclear materials1,7,8. RIS may result in substantial composition changes near cavities, altering local lattice constant, stress fields, and diffusion coefficients9,10,11. These changes could significantly influence cavity formation and stability, thus directly impacting the swelling of materials under irradiation. Therefore, systematically investigating RIS near cavities is essential for predicting the material performance under extensive irradiation.

Advanced characterization techniques, such as Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) or Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS), and Atom Probe Tomography (APT), have been applied to measure RIS near cavities. For instance, Kombaiah et al. employed STEM-EDS to measure RIS around helium bubbles in Fe-Cr-Ni austenitic stainless steels, revealing a nickel enrichment and chromium depletion at the bubble surfaces8. However, the STEM-based techniques are limited by substantial uncertainties due to electron beam projection. In contrast, APT reconstructs element distribution in three-dimension (3D) with ultrahigh chemical sensitivity (~ 10 particles per million), making it a promising tool for resolving RIS near nanoscale features like bubbles. For example, Wang et al. conducted an investigation of helium bubble formation in Ni-based concentrated solid solution alloys (CSAs)12. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to quantify bubble sizes and densities, while APT enabled precise characterization of element segregation around the bubbles. Their findings indicated that certain alloying elements, such as Fe and Pd, are more effective in suppressing bubble growth.

Despite advancements in characterization, model development for simulating RIS near cavities remains limited. Most existing models are based on one-dimensional (1D) formulations originally designed for RIS near GBs8,9,12,13,14. For instance, Okamoto et al. proposed a simplified kinetic model to compute steady-state RIS and segregation-induced strain near voids13. This simulated strain field achieved good agreement with the measurement via strain-contrast TEM images. However, to rigorously validate the RIS models, it is necessary to directly compare simulated and measured composition profiles.

Furthermore, several key differences between nanosized cavities and GBs underscore the limitations of conventional 1D models and highlight the need for more advanced RIS simulations for cavities. First, GBs are typically idealized as 2D planes spaced far apart1,15. Therefore, the interaction between GBs can be neglected, allowing GBs to be treated as boundaries of the simulation domain in the 1D model. In contrast, cavities tend to nucleate at preferred sites like dislocations and grain boundaries, leading to high local cavity densities with small separations (even of a few nanometers). Under these conditions, RIS fields from nearby cavities may overlap and interact16,17. Second, adjacent cavities may vary in diameters and surface curvatures, resulting in different equilibrium point defect concentrations at the cavity surfaces due to the Gibbs-Thomson effect18. Third, gas-filled bubbles usually contain high internal pressures, which further influence local point defect concentrations. Lastly, unlike GBs, which pre-exist before irradiation, cavities nucleate and grow dynamically under irradiation, inherently coupling with the segregation process. Therefore, traditional 1D RIS models that work well for GBs are likely insufficient to capture the complex RIS behavior near nanosized cavities.

RIS simulations are typically based on two mechanisms: inverse Kirkendall (IK) mechanism and the solute drag mechanism. The IK mechanism refers to the irradiation-induced generation and diffusion of point defects toward defect sinks, resulting in concentration gradients of solute elements. Most mean-field rate-theory models designed to explain RIS behaviors rely on this mechanism and have successfully reproduced RIS profiles near GBs in various metallic alloys2,3,4,5,6,19. For example, Perks et al. were the first to employ one of the most widely used IK models to accurately predict the magnitude and direction of RIS in austenitic stainless steel6. Therefore, this model is often referred to as the “Perks model”. Allen et al. refined the original Perks model to improve predictions of RIS near GBs in austenitic Fe-Cr-Ni alloys5. Their modified inverse Kirkendall model incorporates pair interaction energies, ordering energies, and local atomic configurations to calculate diffusion parameters. More recently, Wharry et al. further extended the IK framework to study RIS near GBs in body-centered cubic (BCC) ferritic-martensitic Fe-Cr alloys3. Unlike the original Perks model, which considered only vacancy diffusivity differences, this new model incorporates both vacancy and interstitial diffusivity differences across solute elements. In Fe-Cr alloys, the direction of RIS is governed by the relative magnitudes of the diffusion coefficient ratios. These ratios intersect at a characteristic “crossover” temperature: below this temperature, Cr enrichment occurs predominantly via interstitial mechanisms, whereas above it, Cr depletion is primarily driven by vacancy-mediated diffusion. The solute drag mechanism involves the formation of defect-solute complexes, particularly between solute atoms and vacancies, which can migrate toward sinks and thereby drive solute segregation. While this mechanism has been incorporated into some IK frameworks, it has a negligible effect on both the transition from Cr enrichment to Cr depletion and the overall segregation magnitude. Ab initio-based diffusion theory calculations by Tucker et al.20 for the face-centered cubic (FCC) Ni-Fe system indicate that the rate of defect dissociation consistently exceeds the rate of defect-solute association, thus making the solute drag mechanism unfavorable across all temperatures. Consequently, in this work, the IK mechanism is considered the dominant diffusion mechanism, and the solute drag effect is neglected.

In this study, TEM was employed to quantify the density and size of nanoscale cavities in the single-crystal Ni50Fe50 alloy irradiated by He ions. Leveraging recent advances in APT12,21, elemental segregation near the cavities was characterized with high spatial and chemical resolution. Our calculations found that 1D RIS models were inadequate for capturing RIS behavior between closely spaced cavities. To address this limitation, a two-dimensional (2D) IK model was developed, and the simulation results were directly compared with APT measurements. The 2D model achieved good agreement with experimental RIS data. Moreover, for the first time, we discovered a non-linear coupling effect of RIS between neighboring cavities. Finally, we discussed the limitations of the current modeling framework. For consistency, nanoscale cavities are referred to as helium bubbles throughout the rest of the paper. Note that the methodology developed in this work is equally applicable to voids and other gas-filled bubbles.

Results

Comparison between 1D and 2D IK model

Previous works have applied a 1D spherical model to simulate RIS behavior near bubbles and voids8,9,12,13,14. Our calculation showed that this approach can capture some basic trends of RIS near an isolated bubble. As detailed in the Supplementary Materials Section 1 (Fig. S1), RIS reaches a maximum magnitude at intermediate temperatures (~500 °C), while suppressed at both lower and higher temperatures. The temperature dependence is consistent with that reported near GBs. Supplementary Materials Section 2 (Fig. S2) showed that RIS near the bubble surface increases with irradiation dose and eventually saturates, similar to GB behaviors3,13.

However, the 1D model exhibits significant limitations when simulating RIS between closely spaced bubbles, which are frequently observed in irradiated materials. As illustrated by the TEM image and APT reconstructions in Fig. 1, bubbles are commonly found in close proximity in our Ni50Fe50 sample, and their distribution is clearly non-uniform at the microscale. Nevertheless, a necessary assumption of the 1D model is the homogenous bubble distribution. Based on this assumption, the relationship between the radius of spherical simulation domain, \({R}_{f}\), and the bubble density, \({\rho }_{c}\), can be expressed as:

where \({V}_{{total}}\) is the total material volume and \({N}_{{total}}\) is the total number of bubbles. It becomes evident that to investigate RIS between bubbles which are close to each other, \({R}_{f}\), which equals half the distance between two bubbles, must be reduced, consequently raising the bubble density to high and even unrealistic values. This issue stems from the uniform bubble distribution assumption, which often deviates from actual bubble distribution in irradiated materials. Since bubbles prefer to nucleate heterogeneously near nucleation sites, like dislocation loops and grain boundaries, bubbles may be closely spaced locally even when the overall bubble density remains low. In such scenarios, the 1D model artificially restricts the available diffusion region around each bubble, thereby limiting the number of atoms reaching the bubble surface and yielding unphysical results.

To illustrate the limitation quantitatively, Fig. 2 compares Ni segregation at the bubble surface as a function of inter-bubble distance, calculated using both the 1D spherical model and the 2D IK model. Calculations were conducted at a total dose of 0.8 dpa, a dose rate of \({3.2\times 10}^{-4}\) dpa/s, a radius of bubble \({R}_{b}=2.25{nm}\), and an irradiation temperature of 500 °C, which are consistent with the experimental conditions. Note that \({R}_{f}\) in Fig. 2 corresponds to half of the bubble distance. At large separations (e.g., \({R}_{f}\ge 20{nm})\), the calculated Ni concentration at the bubble surface is approximately 88 at.% (atomic percent) for both models, and the magnitude of Ni segregation is nearly independent of \({R}_{f}\). However, as \({R}_{f}\) decreases to smaller values (e.g., less than 10 nm), the Ni segregation in the 1D model sharply declines, and becomes negligible when the distance between bubbles approaches zero. This trend contradicts the 2D IK model results, shown in blue in Fig. 2, as well as the experimental findings in “Direct comparison between 2D simulation results and APT measurements“, both of which indicate that RIS between closely spaced bubbles is significant and even increases with decreasing separation. These unphysical results from the 1D model underscore its inherent limitation, as it fails to account for the heterogeneous bubble distributions within the matrix.

Ni concentration at the bubble surface of both the 1D spherical model and the 2D IK model as a function of the half-center distance between two adjacent bubbles \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{f}}}\), at a total dose of 0.8 dpa, a dose rate of \({3.2\times 10}^{-4}\) dpa/s, and 500 °C. The simulated bubble radius \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{b}}}\) is 2.25 nm.

Direct comparison between 2D simulation results and APT measurements

As demonstrated in the previous section, the 1D model cannot simulate RIS between closely spaced bubbles. In irradiated materials, however, bubbles often nucleate heterogeneously, leading to locally high bubble densities and small bubble separations. Under these conditions, it is essential to assess whether RIS around one bubble influences neighboring bubbles, and whether a simulation can reliably reproduce the RIS field between multiple bubbles.

To address these questions, we first applied the 2D modified IK model to a case of two closely spaced bubbles. Based on APT measurement, the diameters of the two bubbles are 5.2 nm and 4.4 nm, respectively, with a center-to-center separation of 5.8 nm. The simulation was conducted using the same dose, dose rate, and temperature as in the experiment described in “Comparison between 1D and 2D IK model“. The bubbles were positioned along the central axis of the simulation box, with the box length set to 82 nm, as determined by the method in “Simulation setup of the 1D and 2D modified IK model”. Figure 3a presents the APT reconstruction of the two bubbles, and Fig. 3b shows the corresponding simulated Ni atomic concentration map. Figure 4a–c compares the 1D Ni atomic concentration profiles obtained from APT measurement and extracted from the 2D simulation, using the averaging method described in "Averaging method for direct comparison between simulation results and APT measurement". The gray regions denote bubble positions, and the dashed lines mark their surfaces. Each sub-figure corresponds to a different ROI diameter, i.e., 5 nm, 7 nm, and 10 nm, while maintaining a fixed ROI length of 26 nm. Varying the ROI diameters enables us to assess the comparison’s robustness and to improve statistical reliability. The error bars reflect the uncertainty of APT composition measurements, primarily due to statistical fluctuations in detected atom counts. In general, smaller ROI diameters result in fewer atom counts, increasing the uncertainty magnitude.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the simulation results show good agreement with APT measurements using ROIs of different sizes. Specifically, the APT measurements reveal a 3–4 at.% decrease in Ni concentration at the bubble surface when the ROI diameter increases from 5 nm to 7 nm, and a similar 3–4 at.% reduction from 7 nm to 10 nm. This trend is well captured by the simulation, demonstrating that the averaging method described in "Averaging method for direct comparison between simulation results and APT measurement" effectively links the 2D simulation with the APT measurements. Another intriguing phenomenon is the enhanced RIS magnitude between two bubbles, where the Ni concentration exceeds that at positions equidistant from the bubble surface but on the outer side. For instance, in Fig. 4b, the Ni concentration at the midpoint between the two bubbles (at z = 18.1 nm), where the distance to both bubble surfaces is 2.9 nm, reaches 68.9 at.%. In contrast, at locations with the same distance to the respective bubble surfaces but on the outer sides (at z = 7.1 nm and z = 28.3 nm), the Ni concentrations are only 61.6 at.% and 60.9 at.%, respectively. The increase in segregation exceeds 7 at.% Ni composition and accounts for \(23.8 \%\) (calculated by \(\frac{7{at}. \% }{79.3{at}. \% -50{at}. \% }\)) of the maximum segregation at z = 10.0 nm (i.e., at the bubble surface). Such a substantial difference suggests a strong coupling effect of adjacent bubbles to increase RIS in the regions between them.

To evaluate how well the model generalizes, we applied the model to a second case involving a larger separation between bubbles, i.e., 11.0 nm apart. As shown in Fig. 5a, the diameters of the two bubbles are 4.4 nm and 3.2 nm, respectively. The simulation was performed under the same conditions as the first case. Figure 5b displays the simulated Ni concentration map and Fig. 5c compares the Ni concentration line profile obtained from APT with that extracted from the simulation.

a 3D APT reconstruction of two bubbles with a separation distance of 11.0 nm within a ROI of 5 nm diameter. The diameters of the bubbles are 4.4 nm and 3.2 nm, respectively; b 2D simulated Ni concentration map; c ROI diameter = 5 nm; The grey regions represent the helium bubbles. Dashed lines indicate the bubble surfaces.

As shown in Fig. 5c, the simulation results also match well with the experimental measurements, and the coupling effect between bubbles remains evident in this case. For instance, in Fig. 5c, the Ni concentration at the midpoint between the two bubbles (at z = 18.4 nm) is 59.7 at.%. In contrast, at equidistant positions on the opposite sides of the bubbles (at z = 3.0 nm and z = 32.6 nm), the Ni concentrations are 54.9 at.% and 54.5 at.%, respectively. The increase in segregation exceeds 5.0 at.% Ni composition and accounts for \(16.2 \%\) (calculated by \(\frac{5.0{at}. \% }{80.9{at}. \% -50{at}. \% }\)) of the maximum segregation at z = 8.5 nm in the ROI. The coupling effect is slightly smaller than that observed in the first case because the distance between bubbles increases. Note that in region z < 8.5 nm, the simulated curve declines more rapidly than the experimental measurements. This discrepancy arises because the first bubble in this case is the second bubble in the earlier case, with the RIS magnitude on this side influenced by the neighboring bubble through the coupling effect.

To further validate the 2D model, we applied it to a single bubble case and compared the results with the 1D model. As summarized in Supplementary Materials Sections 1 and 2 (Fig. S1, S2), both models exhibit similar trends with respect to irradiation temperature, dose, and dose rate. We also examined the influence of bubble size on simulated RIS. As shown in Fig. S5, the RIS magnitude increases monotonically with bubble size, consistent with the higher sink strength of larger bubbles. All the calculations demonstrate the validity of the 2D RIS model.

Discussion

As shown in the Results, the 2D IK model demonstrates good agreement with RIS measurements using APT. This validated model now enables us to systematically investigate the interactions of RIS between nearby bubbles by varying their separations. As shown in Fig. 6, two bubbles with identical diameters of 4.5 nm were positioned along the central axis of the simulation box, with the box length set to 200 nm. Like previous cases, the simulation was performed with a total dose of 0.8 dpa, a dose rate of \(3.2\times {10}^{-4}\) dpa/s, an irradiation temperature of 500 °C, and using the input parameters listed in Table 1. We varied the bubble center-to-center separation from 2 nm to 20 nm. Figure 6a illustrates the simulated Ni concentration map for the case where the two bubbles are 3 nm apart. The Ni concentration between the bubbles is clearly higher compared to the outer side at the same distance from the bubble surfaces, indicating a strong coupling of RIS between two bubbles.

To quantify the coupling effect, Fig. 6b compared the Ni concentration at the midpoint of the two bubbles with different bubble separation (blue circles) with the Ni composition near a single bubble at an equivalent distance from the bubble surface (green circles). Note that in the two-bubble case, this distance corresponds to half of the bubble separation. All Ni concentrations present were averaged over a 5 nm-wide bar orientated perpendicular to the central axis to ensure consistency with previous calculations. The results clearly show that Ni segregation between two bubbles is consistently higher than that near a single bubble, regardless of separation distance. An intuitive explanation is that the RIS magnitude between two bubbles is simply the sum of the contributions from each bubble, i.e., due to linear superposition. However, careful analysis revealed that this simple explanation is not always correct. To test this, we also plotted the sum of RIS magnitudes from two isolated bubbles as red circles in Fig. 6b. When the bubbles are sufficiently far apart (e.g., separation > 20 nm, corresponding to >10 nm in Fig. 6b), the RIS between bubbles (blue circles) is only slightly lower than the summed values (red circles). The discrepancy (e.g., 0.7 at.% at 20 nm) is negligible, suggesting that the linear superposition is a reasonable approximation at large bubble separation. However, the discrepancy clearly increases as the bubbles get closer, exceeding 5 at.% as the bubble distances become less than 4 nm (corresponding to 2 nm in Fig. 6b), demonstrating that the liner superposition approximation breaks down due to non-linear coupling of RIS. This non-linearity arises from the competition for solute atoms between close space bubbles. At small separations, the diffusion fields of the two bubbles overlap significantly, so solute atoms in the intervening are attracted toward both sinks. This competition reduces the local availability of solute atoms, limiting RIS. In contrast, solute atoms outside the overlapping region diffuse predominantly toward the nearest bubble with minimal influence from the other bubbles. Consequently, the RIS magnitude in the overlapping region is higher than that near a single bubble but lower than the sum of the two, highlighting the importance of non-linear interactions at short distances.

Prior studies showed that RIS near isolated cavities (e.g., Ni enrichment) can decrease effective vacancy diffusivities, thus reduce vacancy absorption and slowing down cavity growth7,9. Between adjacent cavities, the non-linear coupling effect identified in this work will lead to an expanded RIS region with even higher segregation, which further suppresses vacancy absorption and cavity formation. Therefore, the more accurate RIS calculation enabled by our 2D model directly contributes to more accurate predictions of cavity formation and material swelling8,10,11,12.

Dislocations are another common type of defect that can serve as sinks for point defects. Their preferential absorption of interstitials often leaves behind excess vacancies, which can nucleate and grow into cavities. Consequently, irradiation-induced cavities and dislocations are often co-located. Additionally, dislocations can also introduce RIS, so their proximity to bubbles may substantially modify the RIS near bubbles. Figure 7 presents a representative case. In Fig. 7a, two helium bubbles were reconstructed by APT, with diameters of 4.8 nm and 4.6 nm and a separation of 17.7 nm. Figure 7b presents the corresponding 2D simulation of Ni concentration. The 1D RIS profile extracted from the 2D model is compared with the corresponding APT measurement in Fig. 7c. While the simulated RIS profile matches well with the experiment in the outside regions (i.e., position z < 11 nm and z > 38.2 nm), a notable discrepancy appears between the two bubbles. Specifically, the experimental Ni profile is asymmetric. The Ni concentration is higher than the simulation near the first bubble but lower near the second bubble, indicating a shift in the RIS profile toward the first bubble.

a 3D APT reconstruction of two bubbles with a separation distance of 17.7 nm within a ROI of 5 nm diameter. The diameters of the two bubbles are 4.8 nm and 4.6 nm, respectively. b 2D simulated Ni concentration map; c Comparison of 1D Ni concentration line profiles obtained from APT along the line connecting the centers of the two bubbles with results from 2D IK model simulations. The grey regions represent the helium bubbles. Dashed lines indicate the bubble surface.

To investigate the causes for the discrepancies, the iso-Ni concentration surfaces were reconstructed in 3D. As shown in Fig. 8, green surfaces denote regions with Ni concentration exceeding 68 at.%, and the bubble positions are marked with yellow circles. A loop-shaped feature is observed passing through the first bubble and extending between these two bubbles. The loop feature is likely a dislocation loop. Since the dislocation also introduces RIS, its proximity to the first bubble likely enhances the Ni segregation near the first bubble while reducing it near the second, given the mass conservation. This case highlights the complexity of simulating RIS in regions containing multiple defects. The interaction and overlap of segregation fields from different defect types necessitate more advanced modeling approaches that explicitly account for coupled RIS effects to accurately predict segregation behavior in irradiated materials.

The developed 2D IK-RIS framework can be directly extended to other closely spaced defect sinks, such as GBs in nanocrystalline materials. As shown in Fig. 9a, hexagonal nanograins were tessellated within a 60 nm simulation domain, with individual grain side lengths of 20 nm and 18 nm. GBs are indicated by white lines. The simulation was performed up to a total dose of 8.0 dpa at a dose rate of \(3.2\times {10}^{-4}\) dpa/s and an irradiation temperature of 500 °C, using the input parameters listed in Table 1. Periodic boundary conditions were applied to all domain boundaries. Point defect concentrations at GBs were fixed at thermal equilibrium values provided in Eqs. (13) and (14), without the modifications for cavities with inner pressure and the Gibbs-Thomson effect given in Eqs. (17) and (18). All other numerical settings were kept consistent with the previous cavity simulations.

a Schematic of the simulation domain with GBs marked by white lines, along with the corresponding mesh. The simulation box has a lateral dimension of 60 nm, with individual grain side lengths of 20 nm and 18 nm. b Ni concentration at 0.8 dpa, c at 4.0 dpa, and d at 8.0 dpa. The triple-junction and the midpoint of GBs are labeled as A and B, respectively, and highlighted with yellow circles. e Evolution of Ni concentration at Point (blue circles s) and B (red circles) as a function of dose.

As shown in Fig. 9b–d, for various irradiation doses, the magnitude of RIS near triple-junctions (Point A) is consistently lower than that at the midpoint of the GBs (Point B). To quantify this trend, the Ni concentrations at Points A and B under different doses are plotted in Fig. 9e. Specifically, at 0.8 dpa (Fig. 9b), the Ni concentrations at Points A and B are 58.62 at.% and 71.66 at.%, respectively. At 4.0 dpa (Fig. 9c), the corresponding concentrations increase to 69.69 at.% and 79.43 at.%, and at 8.0 dpa (Fig. 9d), to 74.91 at.% and 79.31 at.%. At low doses, the RIS at Point B increases more rapidly than that at Point A, and the difference in Ni compositions between the two points increases with dose. After approximately 4 dpa, the RIS at Point B reaches saturation, while the RIS at Point A continues to grow. It is clear that the RIS near triple junctions is reduced as compared to the midpoint of GBs.

The underlying mechanism is similar to the non-linear coupling effect identified between closely spaced cavities. Near the triple-junctions, solute atoms can diffuse toward three intersecting GB sinks, resulting in competition among GBs for the limited solute atoms and a locally reduced RIS magnitude. After the RIS near the GB midpoints saturates, the remaining available solute atoms continue to diffuse toward the triple junction, leading to the continued segregation at Point A.

Importantly, such RIS behaviors near triple junctions cannot be captured by conventional 1D RIS model, and only 2D or even 3D models can resolve this non-linear coupling effect. Because RIS near grain boundaries is closely linked to critical degradation mechanisms such as intergranular corrosion and stress corrosion cracking1, the improved accuracy of RIS calculation enabled by our 2D model will enhance the ability to assess and predict these degradation processes.

Despite achieving good agreement with the APT measurements, the 2D modified IK model can be further improved. First, the current approach does not account for the He bubble growth, which occurs concurrently with element diffusion and segregation. On one hand, Ni segregation around bubbles can form a shell that impedes vacancy diffusion to the bubble surface, thereby slowing bubble growth. On the other hand, bubble growth reduces bubble inner pressure and surface curvature, constantly changing the point defect concentration at the bubble surface. Consequently, the vacancy concentration gradient near the bubble surface decreases, which slows vacancy diffusion and ultimately reduces the magnitude of RIS. Therefore, it is essential to develop an integrated model that can simulate RIS and bubble growth simultaneously. Phase-field methods, such as the Wheeler-Boettinger-McFadden (WBM) model22 and the Kim-Kim-Suzuki (KKS) model23, have shown promise in simulating microstructure evolution under irradiation24,25,26,27,28. Combining these approaches with the inverse Kirkendall model could be a promising path forward.

Second, as demonstrated in many studies28,29, 2D simulations can be regarded as cross-sections of the 3D material. Specifically, our 2D RIS simulation represents a slice through the bubble centers, effectively modeling the bubbles as cylindrical rather than spherical in 3D. This limitation is inherent to most 2D simulations, which is why comparisons are made using the 1D averaged RIS profile between the 2D simulation and the 3D experimental data in this work. Despite this limitation, the averaging method enables meaningful, quantitative comparisons. The 2D model remains valid for investigating the curvature effect on RIS and the coupling effect between closely spaced bubbles. As a result, our approach has successfully reproduced experimental 1D RIS profiles and captured key RIS characteristics. To achieve more accurate RIS predictions, the development of 3D models is needed. Such models would enable detailed, pointwise comparisons of RIS fields between simulations and experiments.

In summary, we combined a 2D modified IK model with APT experiments for investigating RIS near nanosized bubbles in the Ni50Fe50 single crystal alloy. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

1. The 2D modified IK model simulations were directly comparable to APT experimental measurements on the nanoscale, demonstrating a good agreement and validating the inverse Kirkendall effect as the dominant mechanism of Ni segregation in Ni50Fe50 alloys.

2. While the conventional 1D model can capture basic characteristics of RIS near isolated bubbles, its assumption of uniform bubble distribution often contradicts experimental findings, yielding unphysical results when bubbles are closely spaced. In contrast, the 2D model developed in this work accounts for heterogeneous bubble distributions and short separations, providing a more realistic representation of RIS behavior.

3. A non-linear coupling effect of RIS between neighboring bubbles was identified. Element segregation between two bubbles is enhanced compared to a single bubble but lower than the linear sum of two bubbles due to competition for solute atoms in the overlapping diffusion fields. Enabled by the 2D simulation framework, a similar effect was also observed near GB triple junctions.

These findings provide a deeper understanding of RIS behavior near bubbles and enable more accurate simulations of RIS in irradiated Ni-based alloys. Notably, the 2D simulation framework developed here is also applicable to other alloy systems, such as ferritic-martensitic steels, as well as to other closely spaced defect sinks like grain boundaries in nanocrystalline materials. Since composition changes near bubbles can strongly influence local defect kinetics and bubble growth, the enhanced RIS simulation capabilities established in this work will improve our ability to predict microstructure evolution and material swelling, contributing to the design of more radiation-tolerant materials for nuclear applications.

Methods

Material fabrication, ion irradiation, and TEM characterization

Single-crystal, FCC Ni50Fe50 was chosen as a model alloy because of its simple microstructure and available point defect diffusivities. The bulk Ni50Fe50 used in this study was synthesized by arc melting and drop casting, employing elemental metals of >99.9% purity30. To form helium bubbles, bulk specimens were irradiated with 200 keV He+ ions using a 200 kV Danfysik Research Ion Implanter at the Ion Beam Materials Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory. The helium ion flux was \(2\times {10}^{13}\) ions/(cm2∙s), with a total fluence of \(5\times {10}^{16}\) ions/cm2. During irradiation, the specimen temperature was maintained at 500 °C and monitored using thermocouples. The irradiation temperature was selected as it is close to the swelling peak temperature observed in ion-irradiated Ni at dose rates ranging from \(8\times {10}^{-5}\) dpa/s to \(1.6\times {10}^{-3}\) dpa/s31. In our experiment, the dose rate was \(3.2\times {10}^{-4}\) dpa/s, thus, we anticipated obvious bubble formation that would facilitate the post-irradiation examination.

TEM was employed to image helium bubbles in the irradiated specimens. Thin lamellae (∼120 nm thick) were prepared using the standard focused-ion beam (FIB) lift-out procedure with an FEI Nova 200 dual-beam FIB. TEM analysis was conducted using a 300 kV FEI Titan instrument. Helium bubbles were characterized using the through-focus technique based on the Fresnel contrast mechanism, where bubbles appeared as bright spots in under-focused conditions and dark spots in over-focused conditions. To quantify the volume swelling, the lamella thicknesses were measured using electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS). The primary source of uncertainty in the swelling calculations came from the sample thickness measurement (~±10%)32. The average bubble diameter measured was 4.5 nm, with a total bubble density of \(6.34\times {10}^{-5}\,{{nm}}^{-3}\), a swelling ratio of \(0.39\pm 0.04\, \%\), and a sink density of 0.0045 \({{nm}}^{-1}\). For more details about material fabrication and TEM analysis, please refer to ref. 33.

RIS characterization using APT

Although STEM-based analytical methods, including EELS and EDS are powerful tools for measuring local composition with high spatial resolution, they present limitations when applied to RIS characterization near nanoscale structures like helium bubbles. As both EELS and EDS rely on the transmission of an electron beam through the sample, the measured composition is averaged along the entire beam path, which can introduce significant errors, especially for small bubbles buried in the specimen. In contrast, APT provides three-dimensional composition measurement with much higher chemical sensitivity (~10 particles per million), allowing for more accurate characterization of elemental segregation near bubbles34. During APT experiments, high-voltage or laser pulses are applied to a needle-shaped specimen, causing individual atoms to be ionized and field-evaporated from the surface. A position-sensitive detector captures the ionized atoms, and their 3D coordinates are reconstructed based on their impact position and evaporation sequence. Simultaneously, time-of-flight measurements determine the mass-to-charge ratio of the ions, enabling elemental identification21.

Figure 10 shows an example of an APT reconstruction of a Ni50Fe50 specimen containing helium bubbles. As demonstrated in previous works, nanosized cavities, including bubbles and voids, would appear as high-atom-density regions in the APT reconstruction because of local tip curvature increases near nanosized cavities. Consequently, these local density increases can be used to identify bubble positions. In Fig. 10a, b, bubbles are highlighted by white iso-density surfaces, defined at a threshold density value = \(52{atoms}/{{nm}}^{3}\) based on the literature. It is important to note that the density here is not the true atom density in materials, but rather a value derived from atom counts in the APT reconstruction. To facilitate quantitative comparisons with RIS simulation, a cylindrical region-of-interest (ROI) (marked by yellow) was applied to extract 1D composition profiles near bubbles (Fig. 10a). Additionally, the 1D local atom density profile was used to identify the locations and sizes of bubbles12,21. Figure 10b shows the enlarged ROI containing two bubbles and Fig. 10c is the corresponding density profile. The axis of this cylindrical ROI is parallel with the line connecting the centers of the two bubbles. According to the literature21, nanosized cavities (including bubbles) would be exhibited as a high-atom-density region due to aberrations in the APT reconstruction process, resulting in peaks along the 1D atom density profile. The peak widths were taken as the bubble diameters, and the distance between the two peaks were taken as the distance between two bubbles. As shown in Fig. 10c, the two bubbles have diameters of 4.4 nm and 3.2 nm, respectively, with a separation of approximately 11.0 nm. Our APT data was collected using a CAMECA LEAP 4000X HR system, operating in laser mode at 45 K with a pulse repetition rate of 200 kHz, a detection rate of 0.004 atoms per pulse, and a laser energy of 70 pJ. The data analysis was conducted using the IVAS toolkit within the AP Suite 6 software.

a APT reconstruction with bubbles indicated by white iso-density surfaces. Cylindrical ROI (indicated in yellow) passing through two bubbles for calculating 1D atomic density profiles. The scale bar is 20 nm. b Enlargement of the cylindrical ROI of two bubbles in the Ni50Fe50 alloy. The separation distance is 11.0 nm within the ROI (diameter=5 nm). The diameters of the two bubbles are 4.4 nm and 3.2 nm. c The corresponding 1D local reduced density profile for these bubbles. The grey regions represent the helium bubbles. Dashed lines indicate the bubble surface.

Modified inverse Kirkendall model

Our RIS calculations were conducted based on the framework of Perks’ IK model6. As shown below, the coupled partial differential equations of atomic concentration of the alloying elements and point defects in Ni50Fe50 are solved as a function of space and time.

In these equations, \(t\) is the time. \({X}_{{Ni}({or\; Fe})}\) and \({X}_{v({or\; i})}\) represent atomic concentration of alloying elements and point defects (i.e., vacancy and interstitial), respectively. Since there are only two alloying elements, the sum of Ni and Fe atomic concentrations is always 100%. Therefore, the element concentration gradients are related by \(\nabla {X}_{{Ni}}=-\nabla {X}_{{Fe}}\), and only Eqs. (2–4) need to be solved. The correlation between atomic concentrations and volumetric concentrations (C) can be expressed as:

where \(\Omega\) is the average atomic volume of the alloy.

The thermodynamic factor \(\alpha\) that converts the element concentration gradient to the chemical potential gradient is given by:

where \({\gamma }_{{Ni\; or\; Fe}}\) is the activity coefficients of solute elements. While the thermodynamic factor is often assumed to be one for dilute alloys, it needs to be calculated for concentrated systems. In this work, \(\alpha\) is calculated using the Termo-Calc software35 for Ni50Fe50 alloy at 500 °C, resulting in a value of 2.45.

According to Manning’s random alloy theory36, partial diffusivities (\({d}_{k-p}\)) can be expressed as:

where \(k=\{{Ni},{Fe}\}\) for an element and \(p=\{v,{i}\}\) for either vacancies or interstitials. \({z}_{p}\) is the number of nearest neighbor sites (coordination number) for different types of point defects. For the Ni50Fe50 alloy of FCC structure, \({z}_{v}={z}_{i}=12\). \({f}_{{kp}}\) is the correlation factor and is set as 0.727 for both vacancies and interstitials. The hopping frequency \({\omega }_{{kp}}\) is calculated based on the equation:

where \({\omega }_{{kp}}^{0}\) is the pre-exponential frequency, \({E}_{{kp}}^{m}\) is the point defect’s migration energy of the \(k\) element, \({k}_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant, and \(T\) is the temperature in Kelvin. The last term \({\lambda }_{p}\) in Eq. (8) is the distance between point defects and their nearest neighboring sites, and it can be calculated as:

where the coefficient \({A}_{p}\) depends on the diffusion mechanism and the crystal structure, and \(a\) is the lattice constant. For alloys with FCC structure, \({A}_{v}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}{and}\,{A}_{i}=\frac{1}{2}\). In summary, the partial diffusivities (\({d}_{k-p}\)) can also be expressed in Arrhenius form:

where \({d}_{k-p}^{0}\) is the pre-exponential factor of specific element \(k\) and point defect \(p\).

On the right-hand side of Eqs. (2–3), the bracketed terms account for the point defect fluxes, \({\varepsilon K}_{0}\) represents the effective point defect generation, and \({R}_{{iv}}{X}_{v}{X}_{i}\) represents the loss of point defects due to recombination. According to the SRIM calculation, the dose rate \({K}_{0}=3.2\times {10}^{-4}\) dpa/s, and the damage efficiency \(\varepsilon\) is estimated to be 3.0% based on previous studies12,37. The recombination coefficient \({R}_{{iv}}\) in the system is determined using the formula:

where \({r}_{{iv}}\) is the recombination radius and estimated in the same way as in refs. 1,19.

Was et al.38 highlighted that variations in interstitial diffusion coefficients among alloying elements may significantly influence RIS. However, many previous RIS calculations assumed uniform interstitial migration energies for all elements, largely due to the lack of accurate migration energy data in the studied alloys5,6,39. Recently, Zhao et al.40 and Zhang et al.41 systematically calculated the formation and migration energies of point defects in Ni-based CSAs using the ab initio method, enabling us to differentiate the contribution of vacancies and interstitials to RIS near helium bubbles.

The initial concentrations for vacancies and interstitials are set to their thermal equilibrium values, as described in Eqs. (13) and (14), while Ni and Fe atoms are uniformly distributed within the simulation domain (represented by \({\Omega }_{s}\) in Fig. 11):

where \({S}_{v,i}^{f}\) represents the formation entropies and \({E}_{v,i}^{f}\) represents the formation energies.

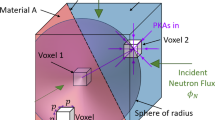

The blue sphere (\({\Omega }_{{\rm{b}}}\)) represents the 1D bubble, while the grey region (\({\Omega }_{{\rm{s}}}\)) represents the diffusion domain. The boundaries \(\partial {\Omega }_{{\rm{b}}}\) and \(\partial {\Omega }_{{\rm{s}}}\) correspond to the bubble surface and the simulation domain boundary, respectively. \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{b}}}\) and \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{f}}}\) denote the average bubble radius and half of the average distance between bubbles, respectively.

At boundaries of the simulation domain (represented by \({\partial \Omega }_{s}\) in Fig. 11), zero gradient boundary conditions are applied to vacancies and interstitials:

Cavities, including both voids and gas bubbles, are typically assumed to be neutral sinks, with point defect concentration at the bubble surface (represented by \(\partial {\Omega }_{b}\) in Fig. 11) remaining at their thermal equilibrium values. It is worth noting that the point defect concentrations near bubble surfaces are different from those in the bulk, since the bubble surface tension and He gas pressure inside can alter the local thermal equilibrium. In this study, the concentrations of point defects at the bubble surface are calculated by Eqs. (17) and (18), which have been modified to account for the Gibbs-Thomson effect and gas pressure within the bubbles1,42:

where \({X}_{v,i}^{0}\) is equilibrium point defect concentrations in the bulk, \(p\) is the bubble gas pressure, \(\sigma\) is the surface energy, and \(R\) is the bubble radius. The bubble gas pressure can be estimated by the helium atom density inside bubbles33. Based on the equation of state in ref. 43, the gas pressure inside helium bubbles with an average diameter of \(4.5\) nm, is about \(7\) Gpa. To the best of our knowledge, no accurate surface energies in the Ni50Fe50 alloy have been reported. However, the surface energies of pure Ni and pure Fe are quite close, with \({\sigma }_{{Ni}}=2.45{J}/{m}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{{Fe}}=2.48{J}/{m}^{2}\)44\(.\) Therefore, we take the average \(\sigma =2.47{J}/{m}^{2}\) for the Ni50Fe50 alloy. As indicated by Eqs. (17, 18), the vacancy concentration is higher at smaller bubbles, whereas the interstitial concentration exhibits the opposite trend.

The boundary conditions specify zero element flux at the bubble surface, while periodic boundary conditions are applied at the simulation domain boundaries to ensure mass conservation. A summary of all input parameters is provided in Table 1. To assess the influence of parameter uncertainties on the calculation results, a sensitivity analysis is conducted, with detailed results presented in Supplementary Materials Section 3 (Figs. S3, S4). The sensitivity analysis identifies the migration energies and the perfectors for point defect diffusion coefficients as the top two most sensitive parameters. Moreover, interstitial migration energies exert a stronger influence than vacancy migration energies for both Ni and Fe. This underscores the importance of modifying the original Perks model to incorporate element-specific interstitial diffusivities for accurate RIS simulation.

Simulation setup of the 1D and 2D modified IK model

We solved the IK model in both 1D and 2D to illustrate the impact of model dimensions on the RIS simulation. In the 1D calculation, we must assume bubbles are of the same size and homogeneously distributed in the materials, as shown in Fig. 11. Given the spherical geometry of bubbles, the calculation was conducted on a spherical domain using spherical coordinates. As shown in Fig. 11, a blue sphere representing the helium bubble is located at the center of the simulation domain. The terms \({R}_{b}\) and \({R}_{f}\) denote the average bubble radius and half of the distance between bubbles, respectively. Based on the measured average bubble diameter and bubble density in "Material fabrication, ion irradiation, and TEM characterization", \({R}_{b}\) and \({R}_{f}\) were set to be 2.25 nm and 15.56 nm, respectively. Because of the spherical symmetry, the concentrations of point defects and elements only vary along the radial direction. The origin of the calculation was set on the bubble surface, and the finite difference method was employed to solve the IK model with a uniform grid along the radial direction. The partial differential equation solver pdede in MATLAB was employed for the numerical calculations.

The 2D modified IK model was solved using the Multiphysics Object Oriented Simulation Environment (MOOSE), a finite-element, multi-physics framework developed by Idaho National Laboratory45. MOOSE offers an intuitive, extensible user interface that abstracts complex numerical methods, enabling the integration of advanced nonlinear solvers. Besides built-in operators, users can add custom calculation modules, known as “kernels”, to model special physical processes. For our RIS simulation, we added two kernels: one for the inverse Kirkendall mechanism and another for the Frankel pair recombination.

A square simulation domain with side length L was used for the 2D simulation. The domain size was chosen to match the sink density of the 2D simulation with that of the real 3D materials. As bubble surfaces are the only defect sinks considered in our model, the sink density in 3D and 2D is calculated as follows:

where \({S}_{{bubbles}}\) represents the total area of bubble surfaces, \({V}_{{total}}\) represents the volume of bulk material. Similarly, \({C}_{{bubbles}}\) represents the total circumference of bubbles in the 2D domain, and \({S}_{{total}}\) represents the total domain area. As shown in "Material fabrication, ion irradiation, and TEM characterization", the measured sink density of our sample is 0.0045 \({{nm}}^{-1}\), which was used to calculate the appropriate domain size \(L\). For example, to simulate a single bubble with an average diameter of 4.5 nm, the side length \(L\) is determined using \({Sink\; Density}=0.0045\,{{nm}}^{-1}=\frac{\pi \times 4.5{nm}}{{L}^{2}}\), yielding \(L=56.05{nm}\).

The 2D domain and the corresponding mesh map used for finite element calculation are shown in Fig. 12. An isotropic structured mesh with 0.4 nm resolution is applied within a 4 nm radius around the bubble surface, gradually transitioning to a coarser unstructured mesh with 4 nm width at the simulation box boundaries in order to enhance computational efficiency. This meshing strategy is appropriate given the highly localized nature of RIS, whose magnitude decays rapidly with distances from defect sinks. The initial normalized time step is set to \(\Delta {t}^{* }=\frac{\Delta t}{{Total\; time}}={10}^{-10}\), and adaptive time-stepping is employed to further optimize computation efficiency. Unless otherwise specified, all simulations use the same mesh setup.

a The simulation domain contains a single helium bubble with a diameter of 4.5 nm centered within the domain and all boundaries are indicated by specific symbols. b The corresponding mesh map includes both structured and unstructured meshes, optimized to balance computational accuracy and efficiency.

For simulating RIS near GBs, the 2D computational domain and the corresponding finite-element mesh are illustrated in Fig. 9a. A fine unstructured triangular mesh with a spatial resolution of 0.25 nm was applied throughout the entire domain, and the same adaptive time-stepping strategy described previously was employed. In addition, the RIS magnitudes at the triple-junction (Point A) and the mid-point (Point B) along the GB were obtained directly from the nodal values at those locations, rather than through any spatial averaging process.

Averaging method for direct comparison between simulation results and APT measurement

As described in “RIS characterization using APT”, cylindrical ROIs were used to extract 1D element concentration profiles across bubbles. It is important to note that the measured concentration at each point represents an average over a disk perpendicular to the ROI axis, with radius r matching the cylindrical ROI and the disc width d = 0.5 nm as defined in the IVAS software. This averaging process is represented by Eq. (20):

where \(\bar{X}(z)\) is the average concentration at position z along the 1D profile, \(V\) is the disc volume, and \(X(x,y,{z})\) is the true local concentration at a specific point \((x,y,{z})\).

To directly compare the simulated composition profile with the measurement, it is necessary to apply a similar averaging process to the simulated concentration map. In 2D simulations, the ROI is represented by a rectangular region that corresponds to the projection of the cylindrical ROI onto the simulation domain. Unlike APT, the simulation does not have a resolution constraint along the z-axis, the step size here can be minimized as much as desired. Thus, the averaged concentration in the simulation is given by:

where \(\bar{X}(z)\) is the average concentration at position z, \(X(x,z)\) is the concentration at a specific point \((x,{z})\), and \(L=|{x}_{2}-{x}_{1}|\) is the width of the rectangular region.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Was, G. S. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science, Springer New York, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3438-6 (2017).

Wiedersich, H., Okamoto, P. R. & Lam, N. Q. A Theory of radiation-induced segregation in concentrated alloys*, (1979).

Wharry, J. P. & Was, G. S. The mechanism of radiation-induced segregation in ferritic–martensitic alloys. Acta Mater. 65, 42–55 (2014).

Duh, T. S., Kai, J. J., Chen, F. R., Wang, L. H. Numerical simulation modeling on the effects of grain boundary misorientation on radiation-induced solute segregation in 304 austenitic stainless steels. www.elsevier.nl/locate/jnucmat (2001).

Allen, T. R. & Was, G. S. Modeling radiation-induced segregation in austenitic Fe–Cr–Ni alloys. Acta Mater. 46, 3679–3691 (1998).

English, C. A., Murphy, S. M. & Perks, J. M. Radiation-induced segregation in metals. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 86, 1263 (1990).

Allen, T. R. et al. Swelling and radiation-induced segregation in austentic alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 342, 90–100 (2005).

Kombaiah, B., Edmondson, P. D., Wang, Y., Boatner, L. A. & Zhang, Y. Mechanisms of radiation-induced segregation around He bubbles in a Fe-Cr-Ni crystal. J. Nucl. Mater. 514, 139–147 (2019).

Wolfer, W. G. & Mansur, L. K. The capture efficiency of coated voids. J. Nucl. Mater. 91, 265–276 (1980).

Mansur, L. K. Void Swelling in Metals and Alloys Under Irradiation: An Assessment of the Theory. Nucl. Technol. 40, 5–34 (1978).

Brailsford, A. D. An effect of solute segregation on void growth in irradiated dilute alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 56, 7–17 (1975).

Wang, X. et al. Understanding effects of chemical complexity on helium bubble formation in Ni-based concentrated solid solution alloys based on elemental segregation measurements. J. Nucl. Mater. 569, 153902 (2022).

Okamoto, P. R. & Wiedersich, H. Segregation of alloying elements to free surfaces during irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 53, 336–345 (1974).

Johnson, R. A. & Lam, N. Q. Solute segregation to voids during irradiation. Phys. Rev. B 15, 1794–1800 (1977).

He, Y. et al. Engineering grain boundaries at the 2D limit for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 11, 57 (2020).

Singh, B. N., Leffers, T., Green, W. V. & Victoria, M. Nucleation of helium bubbles on dislocations, dislocation networks and dislocations in grain boundaries during 600 MeV proton irradiation of aluminium. J. Nucl. Mater. 125, 287–297 (1984).

Brimbal, D., Décamps, B., Barbu, A., Meslin, E. & Henry, J. Dual-beam irradiation of α-iron: Heterogeneous bubble formation on dislocation loops. J. Nucl. Mater. 418, 313–315 (2011).

Perez, M. Gibbs-Thomson effects in phase transformations. Scr. Mater. 52, 709–712 (2005).

Xia, L. D. et al. Radiation induced grain boundary segregation in ferritic/martensitic steels. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 148–154 (2020).

Tucker, J. D., Najafabadi, R., Allen, T. R. & Morgan, D. Ab initio-based diffusion theory and tracer diffusion in Ni–Cr and Ni–Fe alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 405, 216–234 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. Interpreting nanovoids in atom probe tomography data for accurate local compositional measurements. Nat. Commun. 11, 1022 (2020).

Wheeler, A. A., Boettinger, W. J. & McFadden, G. B. Phase-field model for isothermal phase transitions in binary alloys. Phys. Rev. A 45, 7424–7439 (1992).

Kim, S. G., Kim, W. T. & Suzuki, T. Phase-field model for binary alloys. Phys. Rev. E 60, 7186–7197 (1999).

Millett, P. C. & Tonks, M. Phase-field simulations of gas density within bubbles in metals under irradiation. Comput Mater. Sci. 50, 2044–2050 (2011).

Hu, S. et al. Phase-field modeling of gas bubbles and thermal conductivity evolution in nuclear fuels. J. Nucl. Mater. 392, 292–300 (2009).

Semenov, A. A. & Woo, C. H. Modeling void development in irradiated metals in the phase-field framework. J. Nucl. Mater. 454, 60–68 (2014).

Li, Y., Hu, S., Sun, X. & Stan, M. A review: applications of the phase field method in predicting microstructure and property evolution of irradiated nuclear materials. NPJ Comput. Mater. 3, 16 (2017).

Aagesen, L. K. et al. A phase-field model for void and gas bubble superlattice formation in irradiated solids. Comput Mater. Sci. 215, 111772 (2022).

Hu, S. et al. Formation mechanism of gas bubble superlattice in UMo metal fuels: Phase-field modeling investigation. J. Nucl. Mater. 479, 202–215 (2016).

Jin, K. et al. Effects of Fe concentration on the ion-irradiation induced defect evolution and hardening in Ni-Fe solid solution alloys. Acta Mater. 121, 365–373 (2016).

Menzinger, F. & Sacchetti, F. Dose-rate dependence of swelling and damage in ion-irradiated nickel. J. Nucl. Mater. 57, 193–197 (1975).

Zhang, H.-R., Egerton, R. F. & Malac, M. Local thickness measurement through scattering contrast and electron energy-loss spectroscopy. Micron 43, 8–15 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of Fe concentration on helium bubble formation in NiFex single-phase concentrated solid solution alloys. Materialia 5, 100183 (2019).

Miller, M. K. & Forbes, R. G. The Local Electrode Atom Probe, in: Atom-Probe Tomography, Springer US, Boston, MA: pp. 229–258 (2014).

Andersson, J.-O., Helander, T., Höglund, L., Shi, P. & Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, computational tools for materials science. Calphad 26, 273–312 (2002).

Manning, J. R. Correlation Factors for Diffusion in Nondilute Alloys. Phys. Rev. B 4, 1111–1121 (1971).

Was, G. S. & Allen, T. Radiation-induced segregation in multicomponent alloys: Effect of particle type. Mater. Charact. 32, 239–255 (1994).

Was, G. S. et al. Assessment of radiation-induced segregation mechanisms in austenitic and ferritic–martensitic alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 411, 41–50 (2011).

Allen, T. R., Busby, J. T., Was, G. S. & Kenik, E. A. On the mechanism of radiation-induced segregation in austenitic Fe–Cr–Ni alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 255, 44–58 (1998).

Zhao, S., Stocks, G. M. & Zhang, Y. Defect energetics of concentrated solid-solution alloys from ab initio calculations: Ni 0.5 Co 0.5, Ni 0.5 Fe 0.5, Ni 0.8 Fe 0.2 and Ni 0.8 Cr 0.2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 24043–24056 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Osetsky, Y. N. & Weber, W. J. Tunable Chemical Disorder in Concentrated Alloys: Defect Physics and Radiation Performance. Chem. Rev. 122, 789–829 (2022).

Yu, H.-C., Yeon, D.-H., Li, X. & Thornton, K. Continuum simulations of the formation of Kirkendall-effect-induced hollow cylinders in a binary substitutional alloy. Acta Mater. 57, 5348–5360 (2009).

Kortbeek, P. J. & Schouten, J. A. Equation of state of fluid helium to very high pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 95, 4519–4524 (1991).

Skriver, H. L. & Rosengaard, N. M. Surface energy and work function of elemental metals. Phys. Rev. B 46, 7157–7168 (1992).

Permann, C. J. et al. MOOSE: Enabling massively parallel multiphysics simulation. SoftwareX 11, 100430 (2020).

Messina, L., Nastar, M., Garnier, T., Domain, C. & Olsson, P. Exact ab initio transport coefficients in bcc Fe-X (X= Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, P, Si) dilute alloys. Phys. Rev. B 90, 104203 (2014).

Messina, L., Schuler, T., Nastar, M., Marinica, M.-C. & Olsson, P. Solute diffusion by self-interstitial defects and radiation-induced segregation in ferritic Fe–X (X=Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, P, Si) dilute alloys. Acta Mater. 191, 166–185 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-NE0009426. Material characterization was supported by the Energy Dissipation to Defect Evolution (EDDE) Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the DOE Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under contract number DE-AC05-00OR22725. Electron microscopy and APT were conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory's Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (CNMS), which is a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility. We are deeply grateful to Dr. Karren More and Dr. Jonathan Poplawsky from Oak Ridge National Laboratory for their invaluable support and guidance with the APT experiments and analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinyuan Xu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xingyu Liu: Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. William J. Weber: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Yanwen Zhang: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Xing Wang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Liu, X., Weber, W.J. et al. Combining 2D simulations with atom probe tomography to investigate radiation-induced segregation near nanoscale cavities. npj Mater Degrad 10, 14 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00727-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00727-y