Abstract

Multiple factors affect the absorption of orally administered levodopa, the gold standard for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) expresses the enzyme tyrosine decarboxylase (tyrDC), which metabolizes levodopa into dopamine and thereby may influence its absorption in patients with PD. This study investigated the association between fecal E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels and the pharmacokinetics of orally administered levodopa in 21 patients with PD. Our results revealed a significant association between elevated fecal levels of E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels and reduced peak plasma levodopa concentrations. Additionally, among patients receiving levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel treatment, strong positive correlations were observed between E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels in fecal samples and those from the tip of the jejunal tube. Further prospective studies are required to explore the potential role of gut microbiota as a therapeutic target in patients with PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability. The number of patients with PD is growing rapidly and is projected to exceed 12 million worldwide by 20401. PD is pathologically characterized by the degeneration and depletion of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to reduced dopamine levels in the striatum2. Because dopamine cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, treatment for PD involves the administration of levodopa, a precursor of dopamine, to replenish the depleted dopamine levels in the striatum. Despite the availability of various pharmacological interventions to alleviate PD symptoms, levodopa remains the cornerstone of PD therapy, offering the most effective symptomatic relief3. However, orally administered levodopa is extensively metabolized peripherally, primarily by aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), which reduces the amount of levodopa reaching the brain, limiting its therapeutic efficacy. Even when administered in combination with carbidopa, the AADC inhibitor, levodopa has a short half-life of approximately 90 min4. Moreover, as PD pathology progresses, the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and depletion of presynaptic dopamine stores in the striatum lead to a closer correlation between plasma levodopa concentrations and striatal dopamine levels5. Therefore, understanding the factors affecting levodopa absorption and optimizing its bioavailability is crucial for effective symptom management in patients with PD.

Levodopa is absorbed into the bloodstream via a large neutral amino acid transporter, primarily in the upper jejunum. Absorption of orally administered levodopa is influenced by various factors in the gastrointestinal tract, from the oral cavity to the small intestine. Endoscopic evaluation has shown that patients experiencing the delayed-on phenomenon have a higher incidence of swallowing dysfunction and residual medication in the pharynx6. Delayed gastric emptying can impair levodopa absorption. Peak plasma levodopa concentrations were delayed in patients with delayed gastric emptying, as demonstrated by the results of the 13C-octanoic acid expiration breath test7. Our recent studies have shown that the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors or magnesium oxide may reduce the bioavailability of levodopa due to its pharmacokinetic properties8,9. In addition, meal timing, competition for levodopa transport by large neutral amino acids contained in dietary proteins, and Helicobacter pylori infection reportedly influence the efficacy of levodopa10,11,12.

Gut microbiota may also influence the absorption of levodopa. Approximately half of the patients with PD had small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), with an odds ratio of 5.22 for the prevalence of SIBO compared to healthy controls13. Moreover, SIBO-positive patients with PD had longer daily off times than SIBO-negative patients, and the eradication of SIBO resulted in improved motor fluctuations14, suggesting an association between small intestinal bacterial status and PD symptoms. Recently, Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis), an intestinal bacterium, was found to express tyrosine decarboxylase (tyrDC), an enzyme that metabolizes levodopa to dopamine15,16. In patients with high levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in the small intestine, orally administered levodopa may be metabolized in the gut, potentially reducing its bioavailability and consequently diminishing its therapeutic effect. Additionally, patients with moderate responsiveness to levodopa have higher abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in their feces compared to patients with good responsiveness17. However, the relationship between levodopa pharmacokinetics and the levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene has not been thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, previous studies on E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels in patients with PD have relied on fecal samples. No studies have examined these factors using samples from the upper jejunum, where levodopa absorption occurs.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between the levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in fecal samples and the pharmacokinetics of orally administered levodopa in patients with PD. Furthermore, in patients receiving levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) treatment via a jejunal tube (J tube), we aimed to compare the levels of E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels between samples obtained from the tip of the J tube and fecal samples to assess whether fecal samples accurately reflect the microbial environment of the small intestine.

Results

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients evaluated for oral levodopa administration

Twenty-one patients undergoing oral levodopa treatment (female, n = 12 and male, n = 9) were included in this study. Their median age was 72.00 (68.00–74.00) years [median (interquartile range)], and the median disease duration was 7.00 (6.00–9.00) years. Clinical characteristics of the patients, results of the pharmacokinetic analysis, and quantification of E. faecalis and tyrDC gene abundances are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

The mean abundance of E. faecalis was 2.60 × 10−7 (0.33 × 10−7–65.61 × 10−7), while the mean abundance of the tyrDC gene was 8.37 × 10−7 (3.08 × 10−7–36.08 × 10−7). Both exhibited significant variability among patients. Therefore, the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene were used for analysis and visualization. We confirmed that the statistical outcomes of group comparisons and correlation analyses were consistent between the relative abundance of E. faecalis and E. faecalis abundance, as well as between the relative abundance of tyrDC and tyrDC gene abundance.

Associations between E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels and relevant parameters

A significant positive correlation was observed between relative E. faecalis abundance and relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.604, p = 0.004; Supplementary Fig. 2). Levodopa Cmax demonstrated a significant negative correlation with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = −0.529, p = 0.015; Fig. 1a). Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance was significantly negatively correlated with levodopa Cmax (r = −0.509, p = 0.020; Fig. 1b). On the other hand, levodopa AUC showed no significant correlation with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = −0.357, p = 0.113) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = −0.344, p = 0.127) (Fig. 1c, d). Additionally, levodopa Tmax was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.404, p = 0.069) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.329, p = 0.145) (Fig. 1e, f). The daily dose of levodopa was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.401, p = 0.070) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.228, p = 0.209) (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). Similarly, LEDD was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.232, p = 0.309) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.349, p = 0.121) (Supplementary Fig. 3C, D). Disease duration was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.390, p = 0.080) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.005, p = 0.982) (Supplementary Fig. 3E, F). BMI was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.177, p = 0.442) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.061, p = 0.793) (Supplementary Fig. 3G, H). In addition, the concomitant use of anti-parkinsonian medications other than levodopa did not result in significant differences in relative E. faecalis abundance or relative tyrDC gene abundance (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Levodopa Cmax was significantly negatively correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = –0.529, p = 0.015) (a) and relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = –0.509, p = 0.020) (b). Levodopa AUC showed no significant correlation with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = –0.357, p = 0.113) (c) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = –0.344, p = 0.127) (d). Additionally, levodopa Tmax was not significantly correlated with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = 0.404, p = 0.069) (e) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = 0.329, p = 0.145) (f). AUC, area under the plasma concentration-time curve; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; E. faecalis, Enterococcus faecalis; Tmax, time to reach the maximum concentration; tyrDC, tyrosine decarboxylase.

To further investigate the association between E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels and levodopa pharmacokinetics, the plasma concentration ratio of levodopa to carbidopa was calculated. An increase in relative E. faecalis abundance was associated with a significant decrease in the ratio of the Cmax of levodopa to that of carbidopa (r = −0.517, p = 0.018; Fig. 2a). Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance exhibited a significant negative correlation with the ratio of the Cmax of levodopa to that of carbidopa (r = −0.612, p = 0.004; Fig. 2b). In contrast, no significant correlations were observed between the ratio of the AUC of levodopa to that of carbidopa and either relative E. faecalis abundance (r = −0.058, p = 0.802) or relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = −0.273, p = 0.231). These results suggest that E. faecalis and tyrDC contribute to the reduction in levodopa Cmax via levodopa metabolism.

The ratio of the Cmax of levodopa to that of carbidopa showed significant negative correlations with relative E. faecalis abundance (r = –0.517, p = 0.018) (a) and relative tyrDC gene abundance (r = –0.612, p = 0.004) (b). Cmax maximum plasma concentration, E. faecalis Enterococcus faecalis, tyrDC tyrosine decarboxylase.

Comparison of two groups based on levodopa pharmacokinetic results

Due to the limited sample size in this study, multivariate analysis was not feasible. Instead, we compared two groups based on levodopa pharmacokinetics to examine potential influencing factors. Measurements of plasma levodopa concentrations showed that the median maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of levodopa was 9.12 (5.77–10.47) μmol/L, while the median area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) was 11.44 (8.43–12.78) μmol·h/L. Based on these results, the patients were categorized into four groups for comparison: first, those with levodopa Cmax < 9 μmol/L (low levodopa Cmax group) were compared to those with levodopa Cmax ≥ 9 μmol/L (high levodopa Cmax group). Further, patients with levodopa AUC < 11.5 μmol h/L (low levodopa AUC group) were compared to those with levodopa AUC ≥ 11.5 μmol h/L (high levodopa AUC group).

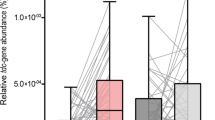

The high levodopa Cmax group (n = 10; 9 females, 1 male) had a higher proportion of female patients than the low levodopa Cmax group (n = 11; 3 females, 8 males) (p = 0.008). Age was comparable between the low levodopa Cmax group [72.00 (67.50–76.50) years] and the high levodopa Cmax group [72.00 (71.25–73.75) years] (p = 0.804). The time to reach the maximum concentration (Tmax) of levodopa was significantly shorter in the high levodopa Cmax group [30.00 (18.75‒30.00) min] than in the low levodopa Cmax group [45.00 (45.00‒90.00) min] (p = 0.002), while carbidopa Tmax did not significantly differ between the two groups (p = 0.468). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in other parameters, including disease duration, Hohen and Yahr stages, BMI, and LEDD (Supplementary Table 1). In the high levodopa Cmax group, the relative abundance of E. faecalis [−24.67 (−25.66 to −23.15)] was significantly lower than that in the low levodopa Cmax group [−17.22 (−19.77 to −10.36)] (p = 0.002; Fig. 3a). Similarly, the relative abundance of the tyrDC gene was significantly lower in the high levodopa Cmax group [−21.33 (−23.51 to −20.67)] compared to the low levodopa Cmax group [−18.08 (−19.51 to −16.63)] (p = 0.005; Fig. 3b).

In the high levodopa Cmax group, the relative abundance of E. faecalis (a) and relative abundance of the tyrDC gene (b) were significantly lower than in the low levodopa Cmax group (p = 0.002 and p = 0.005, respectively). c In the high levodopa AUC group, relative E. faecalis abundance was significantly lower than in the low levodopa AUC group (p = 0.041). d Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance was lower in the high levodopa AUC group than in the low levodopa AUC group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.067). Box-and-whisker plots represent the median (line) and interquartile range. AUC area under the plasma concentration-time curve, Cmax maximum plasma concentration, E. faecalis Enterococcus faecalis, tyrDC tyrosine decarboxylase.

In a between-group comparison of levodopa AUC, the proportion of female patients was also significantly higher in the high levodopa AUC group (9 of 10) than in the low levodopa AUC group (3 of 11) (p = 0.008). Age was slightly, although not significantly, higher in the high levodopa AUC group [72.50 (72.00–74.00) years] than in the low levodopa AUC group [69.00 (65.50–74.00) years] (p = 0.272). Tmax values of levodopa and carbidopa did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.058 and p = 0.085, respectively) (Supplementary Table 2). In the high levodopa AUC group, relative E. faecalis abundance [−24.01 (−25.49 to −22.19)] was significantly lower than in the low levodopa AUC group [−17.95 (−20.97 to −13.52)] (p = 0.041; Fig. 3c). Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance was lower in the high levodopa AUC group [−21.29 (−23.51 to −20.03)] than in the low levodopa AUC group [−18.61 (−20.58 to −17.11)], although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.067; Fig. 3d).

Comparison of E. faecalis abundance and tyrDC gene levels stratified by sex

A comparison between male and female patients was conducted because of the significant differences observed between the high and low levodopa Cmax groups, as well as the high and low levodopa AUC groups. Age did not differ significantly between female [72.00 (71.75–74.00) years] and male patients [69.00 (67.00–74.00) years] (p = 0.668). Female patients had significantly lower body weight [49.15 (47.12–55.35) kg] than male patients [66.00 (55.80–72.80) kg] (p = 0.013), while no significant difference in BMI was observed between female patients [20.77 (18.41–23.32) kg/m2] and male patients [24.19 (20.67–25.55) kg/m2] (p = 0.227). In female patients, levodopa Cmax was 10.41 (9.29–12.39) μmol/L, and levodopa AUC was 12.71 (11.65–13.12) μmol·h/L, both of which were significantly higher than levodopa Cmax [4.88 (4.57–7.30) μmol/L] and AUC [6.95 (6.68–8.58) μmol h/L] in male patients (p = 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively). Further, levodopa Tmax was significantly shorter in female patients [30.00 (26.25–33.75) min] than in male patients [45.00 (45.00–90.00) min] (p = 0.008). In contrast, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the ratio of levodopa Cmax to carbidopa Cmax (p = 0.088) or the ratio of levodopa AUC to carbidopa AUC (p = 0.776). Furthermore, relative E. faecalis abundance was not significantly different between female patients [−23.28 (−25.58 to −17.05)] and male patients [−19.47 (−21.88 to −17.22)] (p = 0.320; Supplementary Fig. 5A). Similarly, no significant difference was observed in relative tyrDC gene abundance between female patients [−20.96 (−21.91 to −19.82)] and male patients [−18.08 (−20.19 to −17.01)] (p = 0.118; Supplementary Fig. 5B). Other clinical parameters, including disease duration and LEDD, also showed no significant differences between male and female patients (Supplementary Table 3).

Comparison of E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels in J tube samples and fecal samples in patients receiving LCIG treatment

Because levodopa is mainly absorbed in the upper small intestine, evaluating the intestinal environment is important. This study compared the small intestinal and fecal environments in patients receiving LCIG treatment. Seven patients receiving LCIG treatment (female, n = 4 and male, n = 3) were included in this study. Their median age was 78.00 (71.00–78.50) years, while disease duration was 15.00 (11.50–16.50) years. The duration of LCIG treatment was 2.00 (1.50–5.00) years, and the maintenance dose of LCIG was 3.00 (2.30–3.35) mL/h. Relative E. faecalis abundance showed a significantly strong positive correlation between fecal and J tube samples (r = 0.786; p = 0.048; Fig. 4a). Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance was significantly and strongly correlated between fecal and J tube samples (r = 0.821; p = 0.034; Fig. 4b). These findings indicate that the presence of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in fecal samples reflects the environment of the upper jejunum, the primary site of levodopa absorption.

a Relative E. faecalis abundance showed a significantly strong positive correlation between fecal and J tube samples (r = 0.786, p = 0.048). b Similarly, relative tyrDC gene abundance was significantly and strongly correlated between fecal and J tube samples (r = 0.821, p = 0.034). E. faecalis Enterococcus faecalis, tyrDC tyrosine decarboxylase.

Discussion

This study focused on two key objectives: first, to examine the relationship between the levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in fecal samples and the pharmacokinetics of levodopa in patients undergoing oral levodopa therapy; second, to compare the levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene between fecal and J tube samples in patients receiving LCIG treatment. The results demonstrated that fecal levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene were significantly associated with levodopa Cmax. Furthermore, strong positive correlations were observed between fecal and J-tube samples for both E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels.

In the low levodopa Cmax group, the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene were significantly elevated, both of which further showed a significant negative correlation with levodopa Cmax. A recent study also reported that tyrDC gene levels in feces are negatively associated with the degree of increase in plasma levodopa concentrations following a levodopa challenge test17, suggesting that E. faecalis and tyrDC gene abundances in the small intestine may contribute to levodopa degradation and reduce its peak plasma concentration. In this study, levodopa Tmax was shorter in the high levodopa Cmax group than in the low levodopa Cmax group, although no significant correlation was observed between levodopa Tmax and the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene. Gastric emptying is the rate-limiting step in levodopa absorption; delayed gastric emptying is associated with prolonged levodopa Tmax18. These findings also suggest that patients with well-functioning upper gastrointestinal tracts, which allow for the rapid delivery of levodopa to the absorption site, may have lower levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene in the intestine. In addition, another study indicated that fecal tyrDC gene levels significantly increased over 2 years in patients with PD19; however, whether this affects the pharmacokinetics of levodopa remains unclear. Therefore, further longitudinal studies are needed to validate the relationship between levodopa absorption and intestinal levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene.

Intestinal E. faecalis and tyrDC are potential novel therapeutic targets for enhancing the bioavailability of levodopa, as indicated by this study and previous reports15,16,17. Due to the abnormal proliferation of Enterococcus species in patients with SIBO20, orally administered levodopa may be metabolized to dopamine in the small intestine before its systemic absorption in patients with SIBO-positive PD. Eradication of SIBO with rifaximin improves motor fluctuations in patients with PD14. However, the mechanism underlying this improvement remains unclear, as no significant changes in levodopa pharmacokinetics were observed before or after SIBO eradication14. Moreover, the L-tyrosine analog (S)-α-fluoromethyltyrosine (AFMT) has been identified as a selective inhibitor of tyrDC-mediated levodopa decarboxylation without affecting AADC15. The concomitant use of AFMT increased levodopa Cmax in mice15. In the future, AFMT or similar inhibitors targeting intestinal decarboxylases may be promising adjunctive therapies for patients receiving levodopa.

Plasma concentrations of both carbidopa and levodopa were measured in this study. The results demonstrated that the ratio of levodopa Cmax to carbidopa Cmax significantly increased as the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene decreased. A previous study in rats reported a significant negative correlation between the levodopa to carbidopa ratio and tyrDC gene abundance in both the jejunum and blood16. This study further corroborated the correlation between the levodopa to carbidopa ratio in plasma and the levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene levels in patients with PD, suggesting a role for tyrDC-mediated metabolism of levodopa.

Although female patients exhibited a significantly higher levodopa Cmax and AUC than male patients, no significant differences were observed between them in relative E. faecalis abundance, relative tyrDC gene abundance, or the levodopa to carbidopa ratio in plasma. These findings imply that intestinal E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene levels are more closely associated with levodopa pharmacokinetics than patient sex.

Patients using PPIs or other acid-suppressing medications were excluded. Our recent study showed that esomeprazole, a commonly used PPI, reduced the levels of levodopa in the plasma without affecting those of carbidopa8. In addition, previous studies have reported a predominance of the genus Enterococcus in individuals using PPIs compared to non-users21 and a significant increase in the genus Enterococcus or family Enterococcaceae after 2–4 weeks of PPI administration22,23. Although it remains unclear whether PPI administration directly affects E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels, it may be advisable to avoid unnecessary PPI use in patients with PD to prevent potential reductions in their plasma levodopa levels.

The strength of this study is that plasma levodopa concentrations were measured in patients with PD after minimizing factors that could affect levodopa pharmacokinetics, allowing for a focused analysis of the association between the resulting pharmacokinetic parameters and E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels. Furthermore, in patients receiving LCIG treatment, a strong correlation was found between E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels in fecal samples and in the small intestine, which is the primary absorption site of levodopa. These findings suggest that fecal analysis may be useful for investigating the relationship between levodopa pharmacokinetics and gut microbiota in future studies.

A major limitation of this study is the small sample size of the patient cohort, indicating the need for further validation of the results in a larger population. Additionally, the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene exhibited a significant negative correlation with levodopa Cmax, whereas no significant correlation was observed with levodopa AUC. In this study, plasma concentrations were measured for up to 3 h following oral levodopa administration, which may have been insufficient for accurate AUC evaluation. Notably, the median carbidopa Tmax was 120 min, potentially contributing to the observed discrepancy between the ratios of Cmax and AUC of levodopa to those of carbidopa. More extensive assessments of levodopa pharmacokinetics after oral administration are needed to evaluate levodopa AUC accurately. Moreover, we did not assess levodopa pharmacokinetics in patients receiving LCIG treatment. In our previous study involving six patients receiving LCIG treatment, we found no clear association between E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene levels, measured from bacterial cultures at the tip of the J tube and plasma concentrations of levodopa24. Factors such as the position of the J tube tip and fasting state can influence levodopa pharmacokinetics during LCIG treatment25,26. Further studies with larger patient cohorts and controlled conditions are needed to clarify the relationship between levodopa pharmacokinetics and E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels in patients receiving LCIG treatment. In addition, this study did not assess tyrDC activity. Given that tyrDC gene levels may not necessarily reflect tyrDC enzymatic activity, future studies should investigate tyrDC activity and its role in levodopa metabolism. Finally, this study did not examine gut microbiota other than E. faecalis. The significant correlation observed between the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene suggests that a substantial proportion of gut tyrDC gene expression originates from E. faecalis. However, other bacteria, such as Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus brevis, Clostridium sporogenes, and some Bifidobacteria species, have also been reported as potential metabolizers of levodopa16,27,28,29,30,31. Therefore, a more comprehensive analysis of the gut microbiota is warranted.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that fecal levels of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene levels are associated with levodopa Cmax in patients receiving oral levodopa. Furthermore, E. faecalis and tyrDC gene levels exhibited significant positive correlations in fecal and J tube samples collected from patients receiving LCIG treatment. These findings may be valuable for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for the tyrDC gene and advancing personalized treatment strategies through gut microbiota profiling in patients with PD.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study prospectively recruited patients with PD receiving oral levodopa or LCIG treatment at Ehime University Hospital between September 2021 and November 2023. All enrolled patients were diagnosed with PD according to the UK Brain Bank Clinical Diagnostic Criteria32.

In patients receiving oral levodopa treatment, the pharmacokinetics of levodopa and carbidopa were evaluated following the administration of a levodopa/carbidopa formulation, and fecal samples were collected. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) a history of chronic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, hepatic dysfunction, or renal dysfunction; (ii) a history of gastrointestinal tract surgery; (iii) use of antibiotics within the past month; (iv) use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), potassium-competitive acid blockers, or histamine H2-receptor antagonists within the past month; or (v) concomitant administration of magnesium oxide or gastrointestinal prokinetic agents. The following patient data were collected: age, sex, disease duration, Hoehn and Yahr stage, body weight, body mass index (BMI), daily dose of levodopa, and levodopa-equivalent daily dose (LEDD)33.

J tube samples were collected from patients receiving LCIG treatment during routine tube replacement. Fecal samples were also collected from the same patients. Data on patient age, sex, disease duration, duration of LCIG treatment, and maintenance LCIG dose were recorded.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research Ethics of Ehime University (approval number: 2108023) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided written informed consent before participation.

Sample collection and DNA extraction from fecal samples and J tube tips

Fecal samples were collected using a fecal collection kit (Metabolokeeper; TechnoSuruga Lab, Shizuoka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In patients receiving LCIG treatment, the tips of the J tube after approximately 6 months of use were obtained at the time of replacement.

DNA was extracted using the ISOSPIN Fecal DNA kit (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) for fecal samples and the DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) for J tube tips in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using the THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) on an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene of E. faecalis (forward: CGCTTCTTTCCTCCCGAGT; reverse: GCCATGCGGCATAAACTG) and the tyrDC gene (forward: CGTACACATTCAGTTGCATGGCAT; reverse: ATGTCCTACTCCTCCTCCCATTTG) were used as previously described15. Primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene of all bacteria (forward: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG; reverse: ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG) were used as an internal control16. Real-time PCR amplification was performed using a total volume of 20 μL per reaction mixture containing 20 ng of template genomic DNA, 10 μL of THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix, and 6 pmol each of forward and reverse primers. The amplification was performed under the following reaction conditions: an initial incubation for 30 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles for 5 s at 95 °C and for 35 s at 60 °C. All qPCR analyses were performed in triplicate for each sample, and mean Ct values were calculated. The Ct[E. faecalis] and Ct[tyrDC gene] values were corrected using the internal control (Ct[16S]), and the Ct[16S–E. faecalis] and Ct[16S–tyrDC gene] values were calculated as the relative abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene, respectively. In addition, the 2−ΔΔCt method34 was used to calculate the 2−(Ct[E. faecalis]−Ct[16S]) and 2−(Ct[tyrDC gene]−Ct[16S]) values as the abundances of E. faecalis and the tyrDC gene, respectively.

Determination of levodopa and carbidopa concentrations in plasma

Plasma concentrations of levodopa and carbidopa were assessed starting at 9:00 a.m., at least 12 h after the last meal, following oral administration of the levodopa formulation. Blood samples were collected via an indwelling catheter before 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after the oral administration of a single tablet containing 100 mg levodopa and 10 mg carbidopa.

The collected blood samples were centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The separated plasma was stored at −80 °C until analysis in our laboratory at Ehime University. High-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection was used to quantify levodopa and carbidopa in plasma, as described in our previous study9.

Statistical analysis

The Cmax and Tmax were determined, and the AUC up to 3 h after oral administration of a single tablet containing 100 mg levodopa and 10 mg carbidopa was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The two groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to assess the correlation between two variables. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.4.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Dorsey, E. R. & Bloem, B. R. The Parkinson pandemic—a call to action. JAMA Neurol. 75, 9–10 (2018).

Fearnley, J. M. & Lees, A. J. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 114, 2283–2301 (1991).

Pringsheim, T. et al. Dopaminergic therapy for motor symptoms in early parkinson disease practice guideline summary: a report of the AAN guideline subcommittee. Neurology 97, 942–957 (2021).

Deleu, D., Northway, M. G. & Hanssens, Y. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of drugs used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 41, 261–309 (2002).

Nutt, J. G. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of levodopa. Mov. Disord. 23, S580–S584 (2008).

Fukae, J. et al. Impact of residual drug in the pharynx on the delayed-on phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 7, 273–278, (2020).

Doi, H. et al. Plasma levodopa peak delay and impaired gastric emptying in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 319, 86–88 (2012).

Miyaue, N., Yabe, H. & Nagai, M. Effect of concomitant use of esomeprazole on levodopa pharmacokinetics and clinical symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 465, 123202 (2024).

Miyaue, N., Yabe, H. & Nagai, M. Concomitant use of magnesium oxide significantly decreases absorption of levodopa preparations in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. 9, 100227 (2023).

Baruzzi, A. et al. Influence of meal ingestion time on pharmacokinetics of orally administered levodopa in parkinsonian patients. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 10, 527–537 (1987).

Carter, J. H., Nutt, J. G., Woodward, W. R., Hatcher, L. F. & Trotman, T. L. Amount and distribution of dietary protein affects clinical response to levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 39, 552–556 (1989).

Pierantozzi, M. et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced reduction of acute levodopa absorption in Parkinson’s disease patients. Ann. Neurol. 50, 686–687 (2001).

Li, X., Feng, X., Jiang, Z. & Jiang, Z. Association of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Pathog. 13, 25 (2021).

Fasano, A. et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 28, 1241–1249 (2013).

Maini Rekdal, V., Bess, E. N., Bisanz, J. E., Turnbaugh, P. J. & Balskus, E. P. Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science 364, eaau6323 (2019).

van Kessel, S. P. et al. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases restrict levels of levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 10, 310 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between microbial tyrosine decarboxylase gene and levodopa responsiveness in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology 99, e2443–e2453 (2022).

Pfeiffer, R. F., Isaacson, S. H. & Pahwa, R. Clinical implications of gastric complications on levodopa treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 76, 63–71 (2020).

van Kessel, S. P., Auvinen, P., Scheperjans, F. & El Aidy, S. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylase associates with clinical variables in a longitudinal cohort study of Parkinsons disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 115 (2021).

Pyleris, E. et al. The prevalence of overgrowth by aerobic bacteria in the small intestine by small bowel culture: relationship with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 57, 1321–1329 (2012).

Imhann, F. et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut 65, 740–748 (2016).

Llorente, C. et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat. Commun. 8, 837 (2017).

Freedberg, D. E. et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter specific taxa in the human gastrointestinal microbiome: a crossover trial. Gastroenterology 149, 883–885.e889 (2015).

Yamanishi, Y. et al. Impact of intestinal bacteria on levodopa pharmacokinetics in LCIG therapy. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 9, 362–368, (2022).

Miyaue, N., Yabe, H., Nomoto, M. & Nagai, M. Effect of percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy tube placement on levodopa pharmacokinetics. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 75, 1753–1755 (2019).

Miyaue, N. et al. Fasting state is one of the factors associated with plasma levodopa fluctuations during levodopa‒carbidopa intestinal gel treatment. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 91, 55–58 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Heterologous expression and characterization of tyrosine decarboxylase from Enterococcus faecalis R612Z1 and Enterococcus faecium R615Z1. J. Food Prot. 77, 592–598 (2014).

Zhang, K. & Ni, Y. Tyrosine decarboxylase from Lactobacillus brevis: soluble expression and characterization. Protein Expr. Purif. 94, 33–39 (2014).

Zhu, H. et al. Crystal structure of tyrosine decarboxylase and identification of key residues involved in conformational swing and substrate binding. Sci. Rep. 6, 27779 (2016).

van Kessel, S. P. et al. Gut bacterial deamination of residual levodopa medication for Parkinson’s disease. BMC Biol. 18, 137 (2020).

Cirstea, M. S. et al. A novel pathway of levodopa metabolism by commensal Bifidobacteria. Sci. Rep. 13, 19155 (2023).

Hughes, A. J., Daniel, S. E., Kilford, L. & Lees, A. J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 181–184 (1992).

Schade, S., Mollenhauer, B. & Trenkwalder, C. Levodopa equivalent dose conversion factors: an updated proposal including opicapone and safinamide. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 7, 343–345 (2020).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology Research and the Japanese Society of Clinical Pharmacology. The authors thank Madoka Kubo for technical assistance with the measurement of levodopa and carbidopa plasma concentrations. We also thank the gastroenterologists who assisted in collecting the tips of the J tubes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M. conceived and designed the study; N.M., Y.I., Y.Y., and R.A. acquired the data; N.M., H.Y., and S.L. analyzed the data; N.M. drafted the paper; H.Y., S.L., Y.I., Y.Y., R.A., Y.S., M.M., and M.N. critically revised the paper. All authors read and reviewed the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miyaue, N., Yamamoto, H., Liu, S. et al. Association of Enterococcus faecalis and tyrosine decarboxylase gene levels with levodopa pharmacokinetics in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 49 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00903-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00903-6