Abstract

Substantia nigra hyperechogenicity (SNH) assessed by transcranial sonography (TCS) is a neuroimaging biomarker of Parkinson’s disease (PD), but its actual location and spatial changes are poorly understood. We aimed to evaluate the location and spatial progression of SNH in PD utilizing TCS-MR fusion imaging. This prospective study enrolled eighty-four PD patients and sixty-two controls. The plane with the largest area of red nucleus, the plane with the largest area of SNH, and the plane where the red nucleus is just out of view were selected and segmented, respectively, and echogenicity indices were calculated. SNH could present in SN, dorsal band of SN, red nucleus, and ventral tegmental area, and had two orientations. In the left midbrain, the anterior-posterior orientation had longer disease duration, larger SNH area, and higher Hoehn-Yahr stage than medial-lateral orientation. The anterior-posterior orientation and accumulation in various nuclei of SNH may serve as promising neuroimaging markers for PD progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease worldwide, and its global burden has more than doubled over the past two decades1. PD is characterized by the gradual degradation of dopaminergic neuromelanin-containing cells in the substantia nigra (SN) pars compacta (SNc), as well as diminished striatal dopaminergic function associated with increasing iron accumulation in the SN1. Substantial nigra hyperechogeneity (SNH) assessed by transcranial sonography (TCS) is a neuroimaging biomarker of PD with high sensitivity and specificity2,3. However, current methods for evaluating SNH rely on qualitative (grading echogenicity of SN from I-V) or semi-quantitative assessment (outlining the area of SNH) by the radiologist’s inspection. This subjective approach can lead to variability in results due to the individual experience of the radiologist4.

TCS lacks the ability to accurately delineate the boundaries of the SN and the red nucleus, or to localize the internal sub-anatomic structures of the SN due to limitations in ultrasound resolution. In contrast, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with high resolution can effectively distinguish between various brain structures. SNH is believed to be linked to iron deposition; functional MRI studies have shown that striatal dopaminergic denervation occurs initially, followed by abnormal iron metabolism, and ultimately changes in neuromelanin changes in the SNc5,6. Iron accumulation in PD progresses from the ventral to dorsal gradient7. An overlapping area of TCS and quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of PD patients indicates that SNH may be located beyond the SN8. However, this observation warrants further investigation as the spatial distribution of SNH in PD has not been comprehensively explored.

Fusion imaging combines the unique features of various imaging technologies to enhance overall imaging capabilities. TCS-MR fusion imaging, which dates back to 2005 and was proposed by Kern et al.9, has undergone significant advancements. Fuerst et al. achieved automatic and robust registration of both freehand ultrasound slices and volumes with MRI images by utilizing Linear Correction of Linear Combination (LC2)10, a method that was validated by the MICCAI Challenge 2018 for the Correction of Brain shift with Intra-Operative UltraSound11. Our previous study utilized real-time TCS-MR fusion imaging for image-guided surgery in high-grade glioma cases12. Recently, studies on neurodegenerative diseases have demonstrated that TCS-MR fusion imaging allows for the localization and assessment of echogenic changes in deep brain nuclei4, as well as the evaluation of brain electrode location following deep brain stimulation13,14. This leads us to propose that TCS-MR fusion imaging can accurately pinpoint SNH in patients with PD and investigate the spatial progression of SNH.

Results

Feasibility of fusion imaging, demographics and clinical characteristics

The overall workflow of fusion imaging and region of interest (ROI) segmentation is depicted in Fig. 1. Data registration and matching were completed within 5 min for all subjects. Successful volume navigation was achieved after proper registration in all cases. Two patients experienced failed image fusion due to involuntary movement of their limbs or head. Ultimately, a total of eighty-four consecutive PD patients (62.73 ± 9.21 years, 61.9% men) and sixty-two controls (59.61 ± 10.04 years, 75.8% men) were included in this study. The patient selection flow-gram is available in Supplementary Fig. 1. The average scan time with fusion imaging was 10.41 ± 0.30 minutes. Among the PD patients, the mean disease duration was 7.24 ± 0.54 years, the mean Hoehn and Yahr (H-Y) stage was 2.62 ± 0.08, with an equal split distribution between early- and middle-late-stage, and the mean Unified PD Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III) score was 37.76 ± 1.67. Detailed demographic and clinical information are summarized in Table 1.

MRI magnetic resonance imaging, TCS transcranial sonography, ROI region of interest, plane SN1 the plane with the largest area of red nucleus on MRI, plane SN2 the plane with the largest area of substantia nigra hyperechogenicity, plane SN3 the plane where the red nucleus is barely identified or no longer visible.

TCS findings

The Kappa and interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values for SN grading and aSNH calculation were 0.89 and 0.86, respectively. In the PD group, the average midbrain area was 5.17 ± 0.72 cm2, with SNH+ accounting for 78.6%, left SNH+ accounting for 69.0%, right SNH+ accounting for 44.0%. The medians of left area of SNH (aSNH), right aSNH, and aSNHmax were 0.225 (0~0.68) cm2, 0 (0~0.59) cm2, and 0.24 (0~0.68) cm2, respectively. Additionally, the median aSNH/area of midbrain (S/M) ratio was 6.32% (0~31.2). Statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in overall SN stage (P = 0.013), left SN stage (P = 0.001), left aSNH (P = 0.002), aSNHmax (P = 0.006), and the ratio of S/M (P = 0.004) (Table 1).

Fusion imaging findings and Greyscale median analysis

Following image fusion, ROIs of the SN and red nuclei were accurately segmented in the TCS image. The ICC score for ROI segmentation was 0.84. There were significant differences in the echogenicity of the bilateral SN1 and SN3, as well as the maximum echogenicity of SN1, between PD patients and healthy controls. The mean echogenicity indices of the left SN1 and SN3, right SN1 and SN3, and the maximum echogenicity of SN1 in the PD group were higher compared to those in the control group (all P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was utilized to assess the diagnostic accuracy of various parameters for PD. The area under the curve (AUC) for echogenicity of left SN1 and SN3, right SN1 and SN3, left aSNH, aSNHmax, maximum echogenicity of SN1, and S/M were presented in Fig. 2. Among these parameters, the echogenicity of left SN1 exhibited the highest diagnostic efficacy for PD, with an AUC of 0.821 (P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.739 ~ 0.903). A cut-off value of 15.42 generated high sensitivity (95.9%) and moderate specificity (70.2%) in diagnosing PD (Supplementary Table 1).

Spatial localization and variations of SNH

The boundaries of the hyperechoic area were delineated, revealing that heperechogenicity can be present in areas beyond the SN, such as the dorsal band of SN (DBSN), red nucleus, and VTA (Figs. 3 and 4). In the left midbrain of the PD group, there were 8 hyperechoic regions in the SN, 13 in the DBSN, 30 in both the SN and DBSN, 4 in the SN and red nuclei, 2 in the SN, DBSN, and red nuclei simultaneously, and 1 in the SN and VTA. The hyperechoic areas in the right midbrain included 13 in the SN, 1 in the DBSN, 11 in both the SN and DBSN, 2 in the SN and red nuclei, 1 simultaneously in the SN, DBSN, and red nuclei, and 1 in the DBSN and red nuclei. Further details can be found in Table 2.

A patient with Parkinson’s disease (Hoehn and Yahr stage 3, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III score: 53 points), whose hyperechonic region (yellow arrow in (A)) is defined to the right substantia nigra. Yellow region of interest (ROI) indicates substantia nigra, red ROI indicates red nucleus, blue ROI indicates hyperechonic region in the right substantia nigra. A Fusion image; B ROI segmentation on magnetic resonance image; C corresponding zoom-in region in (B); D ROI segmentation on transcranial sonographic image; E corresponding zoom-in region in (D).

A patient with Parkinson’s disease (Hoehn and Yahr stage 2, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III score: 38 points), whose hyperechonic region (yellow arrow in (A)) involves the right substantia nigra and dorsal band of substantia nigra. Yellow region of interest (ROI) indicates substantia nigra, red ROI indicates red nucleus, blue ROI indicates hyperechonic region in the substantia nigra, pink ROI indicates hyperechonic region in the dorsal band of substantia nigra. A Fusion image; B ROI segmentation on magnetic resonance image; C corresponding zoom-in region in (B); D ROI segmentation on transcranial sonographic image; E corresponding zoom-in region in (D).

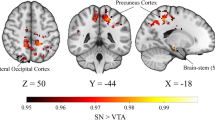

By utilizing slice-to-slice analysis through fusion imaging, the hyperechoic signal generation direction can be categorized into two orientations: medial-lateral and anterior-posterior. The former means indicates that the hyperechoic region stretches along the long axis of the SN, while the latter suggests that the hyperechoic region extends parallel to the short axis of the SN (Fig. 5). Furthermore, considering the 3D nature of the midbrain, we separated it into rostral and caudal levels based on established literature where the red nucleus is just out of view15. In the left midbrain, 58.6% of hyperechoic regions were exclusively observed in the rostral level, 39.7% were present in both rostral and caudal levels, and only one case was identified solely in the caudal level. For the right midbrain, these percentages were 84.2% and 13.2%, respectively, with one instance found only in the caudal level (Table 2).

A–D Medial-lateral orientation. A The superimposition image of MRI and TCS; B side-by-side display of MRI and TCS image; C corresponding zoom-in region on TCS image, yellow arrows indicate substantia nigra hyperechogenicity, which is stretches along the long axis of the substantia nigra; D anatomical sketch. E–H Anterior-posterior orientation. E The superimposition image of MRI and TCS; F side-by-side display of MRI and TCS image; G corresponding zoom-in region on TCS image, yellow arrows indicate substantia nigra hyperechogenicity, which is extends parallel to the short axis of the substantia nigra; H anatomical sketch.

Then, PD patients with SNH were divided into two groups based on their development orientations. In the left midbrain, there were 39 cases in the medial-lateral group and 19 in the anterior-posterior group. Significant differences were observed in disease duration, H-Y stage, aSNH, average pixel and echogenicity indices of hyperechoic region, rostral and caudal levels of SNH, and nuclei involved between the two groups. The anterior-posterior group, compared to medial-lateral group, had a longer disease duration, a larger hyperechoic region area and pixel, and a higher percentage of middle-late-stage patients. In the right midbrain, there were 30 cases in the medial-lateral group and 8 in the anterior-posterior group. Apart from the difference in echogenicity of hyperechoic region in SN, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in any of the variables. The UPDRS-III differences in the two groups on both sides were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Details are available in Table 2.

Correlation analysis

Given that the TCS and TCS-MR fusion imaging findings between the PD and healthy controls differed primarily in the left midbrain, Spearman correlation analysis was utilized to explore the relationships between imaging findings in the left side. The analysis found a positive correlation between the area of left SNH and various factors such as disease duration, echogenicity of SN1, SN2, and pixel of SNH. Additionally, correlations were observed between different SN pixel counts, hyperechoic signals, and total SNH pixel count. However, no statistically significant correlations were found between pixel count and echogenicity of ROIs, H-Y stage, disease duration, UPDRS-III, and age (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, the relationship between spatial changes in the left SNH and clinical parameters was investigated using Spearman correlation analysis. Results showed positive correlations between the orientation of left SNH and various variables such as disease duration, H-Y stage, aSNH, rostral and caudal levels, and SNH pixel count. Negative correlation was observed between rostral and caudal levels of SNH and UPDRS-III score. The details are presented in Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 6.

Logistic regression analysis

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify potential clinical risk factors associated with the orientation of the SNH. In the left midbrain, the univariate analysis revealed that disease duration [odds ratio (OR) = 1.188, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.024 ~ 1.378, P = 0.023] and H-Y stage (OR = 0.276, 95% CI = 0.083 ~ 0.918, P = 0.036) were identified as potential risk factors. However, the multivariate analysis indicated that only disease duration (OR = 1.172, 95% CI = 1.004 ~ 1.369, P = 0.045) was a significant risk factor for the anterior-posterior orientation of the left SNH. In contrast, no clinical risk factor was found to be associated with the orientation of the right SNH (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, TCS-MR fusion imaging was utilized to precisely pinpoint hyperechoic signals in patients with PD and to quantify the echogenicity of SN using digital image analysis. The results indicated that accurate localization of midbrain nuclei on TCS images was possible through TCS-MR fusion imaging navigation. The echogenicity indices of left SN1, measured using ImageJ, outperformed SNH area and S/M ratio in diagnosing PD, suggesting its potential as a valuable tool in clinical settings. Furthermore, the study revealed that hyperechoic signals could arise in nuclei other than SN, and that the progression of SNH followed an anterior-to-posterior, rostral-to-caudal pattern as the disease advanced. The anterior-to-posterior orientation and accumulation of hyperechoic regions in various nuclei may serve as promising neuroimaging markers for tracking disease progression in PD patients.

A meta-analysis reported a wide range of sensitivity (48.7~93.4%) and specificity (55.2~92.0%) for diagnosing PD using various cut-off values (area of SNH ranging from 0.14 to 0.25 cm2)16. How to improve biomarkers for diagnosis and progression tracking is a hot topic given the global burden of PD. Although several studies have reported the application of TCS-MR fusion imaging in the neurology field, the exploration of this technique in PD diagnosis has not been thoroughly investigated. Skoloudik et al. employed TCS-MR fusion imaging to evaluate the SN echogenicity in 21 early-onset PD patients, 22 Wilson’s disease patients, and 24 healthy controls, showing higher SN echogenicity in early-onset PD patients17. Our study corroborates these findings. However, the TCS-MR registration and ROI selection are crucial for future digital analyses. Prior studies have proposed methods for semi-automatic segmentation of the midbrain and automatic segmentation of the SNH on 3D TCS datasets18,19. Subsequently, TCS images were automatically registered to MRI using the Iterative Closest Points algorithm and LC28. In the research conducted by Kozel4 and Školoudík17, TCS and MR images were automatically registered through the Virtual Navigator, with the ROI of SN was manually positioned as an elliptical section (area: 50 mm2) within the echogenic region on the fused images. The elliptical shape and fixed area of 50 mm2 may not accurately represent the shape and size of the SN, and manual ROI placement relies heavily on subjective perception. In our study, we facilitated automatically registration through Virtual Navigator, and generated coordinate position relations to automatically determine the precise position and shape of the SN and red nucleus on TCS, providing a more accurate representation of their current state. We discovered that, in comparison to the area of left SNH and S/M, two indexes commonly used in PD diagnosis20, the echogenicity of the left SN yielded the highest AUC, implying that digital analysis of SN using TCS-MR fusion imaging could be a more effective and alternative method than manually SNH identification, which aligns to prior study21.

This study found a higher prevalence of SNH in healthy controls compared to previous research. This discrepancy may be partly attributed to the older age of the control group, as the area of SNH was found to increase over time in healthy volunteers, suggesting a dynamic process20. The etiology of increased hyperechogenicity in the SN region remains unclear, studies have shown a link between iron accumulation5 and basal ganglia calcification22 with neurodegeneration in PD patients. Research on a 6-hydroxydopamine induced rat model of PD and postmortem brains demonstrated ferric ion accumulation and microglia proliferation in the SNH region23,24. While susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) can quantify iron content in brain tissue, no significant connection was found between SWI area and SNH area25. In this study, the pixel (pixels can be approximated as area sizes) of SN1 and total SNH, and hyperoechogenicity in SN on TCS were segmented and calculated from the positional information, which were positively correlated with each other. However, there was no significant association between pixel of SN1 and area of SNH (which aligns with Prasuhn’s results25), or between pixel of SN1 and echogenicity of SN1 and SNH. These results indirectly suggest that SNH enlargement was associated with the range of iron deposition, while the echogenic index of the SN does not.

With the progression of PD, the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons follows a certain spatiotemporal distribution pattern. Initially, striatal dopaminergic denervation occurs, followed by abnormal iron metabolism, and ultimately changes in neuromelanin within the SNc5. The degeneration of neuromelanin progresses from the posterolateral to the anteromedial region of SN over time26. Nevertheless, the research on the spatial distribution of SNH remains limited. In this study, we employed image post-processing software to identify, segment, and analyze the precise localization of midbrain nuclei (including SN, red nucleus, and VTA) and aberrant hyperechoic region on MRI and TCS superimposed images. The findings indicated that not all hyperechoic signals labeled as “SNH” are located within the SN, they are also present in the DBSN, red nucleus, and VTA. This further validates Ahmadi’s results, which identified SNH within the SNc, rostral VTA, and parabrachial pigmented nucleus in PD patients8. Additionally, two distinct orientations of SNH extension were identified: medial-lateral and anterior-posterior. Correlation analysis results showed no obvious association between SNH area and H-Y stage or UPDRS-III score, consistent with prior study27. However, a positive correlation was observed with disease duration, rostral and caudal levels of SNH, echogenicity of SN1 and SN3, pixel count of SNH, as well as involved nuclei. Further investigation demonstrated that in the left midbrain, the anterior-posterior orientation was associated with later H-Y stage, longer disease duration, larger hyperechogenicity area, and broader involvement of nuclei. The rostral and caudal levels of SNH were positively correlated with SNH orientation, disease duration, SNH area and pixel count, and involved nuclei. Logistic regression analysis indicated disease duration is an independent risk factor for anterior-posterior orientation. These findings illustrated that as PD progressed, there is a spatial progression of left SNH from anterior to posterior, rostral to caudal, and from less to greater, reflecting the pattern of neuronal degradation. The presence of an antero-posterior oriented SNH may serve as a new neuroimaging marker of tracking disease advancement in PD. However, this spatial pattern was not as evident in the right midbrain, possibly due to the participants being right-handed and exhibiting left-hemispheric dominance of nigrostriatal dysfunction. The asymmetrical neurodegeneration initially weakens the dominant hemisphere’s nigrostriatal system28, indicating that right-handedness could potentially heighten the susceptibility to PD pathology through variations activation levels of basal ganglia motor circuits, with the left nigrostriatal system showing higher baseline activity29.

Some limitations need to be addressed. A major concern is that all patients were clinically diagnosed rather than pathologically confirmed, highlighting the potential for misdiagnosis or omission. While an experienced neurologist conducted the diagnoses, challenges in PD diagnosis persistit30. Secondly, the equipment used could not reconstruct a three dimensional (3D) volumetric structure due to its limited resolution and the constraints of 2D-tracked TCS, which hindered observation of some midbrain and SN sub-structure. In the future, strengthening medical and engineering collaboration using high-resolution devices and advanced 3D imaging technologies may yield new insights into this area of research. Furthermore, manual ROI segmentation may have introduced bias, despite the rater being trained and showing consistency in ICC test results. Fortunately, our team has successfully implemented automatic segmentation of the midbrain and SNH with artificial intelligence31,32. This advancement paves the way for the next step: achieving automatic segmentation of nuclei and ROI in fusion images. However, the single-center cross-sectional design and limited sample size restrict the observation of longitudinal evolution of SNH throughout the course of PD disease. Future multi-center investigations and longitudinal studies are required to validate methodology reproducibility and delve into potential pathological mechanisms of SNH spatiotemporal change patterns.

The results presented here suggest that not all hyperechoic signals are presented in the substantia nigra, TCS-MR fusion imaging is a valuable tool for precisely locating deep brain nuclei and hyperechoic regions in patients with PD, and echogenicity of the left SN1 can generate high diagnostic power for PD using digital image analysis. In PD patients, the advancement of SNH follows an anterior to posterior, rostral to caudal spatial pattern in the left midbrain.

Methods

Patient selection and study design

Patients meeting the criteria set by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society33 who were treated in the Department of Dyskinesia and underwent both brain MRI and TCS examination were prospectively recruited from November 2023 to May 2024. Eligible participants were individuals with PD, aged 18 years and above, with clear brain MRI images and a TCS result. Exclusion criteria included Parkinson syndrome caused by other cerebral diseases, insufficient medical history, inconclusive TCS results, and patients with implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes, stem cell therapy, or pallidotomy. The control group consisted of age- and gender-matched healthy volunteers from the same medical center.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Ethics Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. KY2022-015-04). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Trail registration: Chinese Clinical Trail Registry Identifier: ChiCTR1900021846.

Brain MRI examination

Brain MR images were acquired using a 3T MRI machine (Ingenia CX, Philips, Best, the Netherlands). The protocol included 3D T1-weighted imaging (WI), axial T2WI, axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and axial SWI. Prior to the MRI examination, an automatic tracker with four points was affixed to the patient’s forehead. During the scan, it is essential for the MRI positioning image to include the automatic tracker. After the scan, the position of the tracker on the patient’s forehead should be marked, after which the tracker can be removed, and the patient returned to the ward. The axial sections were obtained parallel to the standard reference plane between the anterior and posterior commissures, with SWI covering the foramen magnum to the vertex. The SWI was obtained using a 3D multi-gradient echo with the following parameters: 88 ms repetition time, multiple echo times of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 ms, 0.38 ×0.38 ×2 mm3 voxel size, 192 ×192 field of view, 384 ×384 matrix, 119 slices, 2.5 mm slice thickness, and 10° flip angle.

TCS examination

All participants underwent TCS within one week of their brain MRI using an ultrasound machine (Aplio i900, Canon, Japan) with an I6SX1 phased array probe (2.0~3.0 MHz) operated by an experienced sonographer (W. Z.). The TCS procedure followed the protocol outlined in our previous study2. The echogenicity of the SN was rated based on the criteria established by Bartova et al.34, where a grade of ≥III indicated SNH+. Two expert sonographers (W. Z. and W. H.), each with over 10 years of neuroimaging experience and blinded to clinical information, evaluated SN grading and hyperechoic regions of the SN. The aSNH was measured by circling and calculating hyperechoic signal in the ipsilateral temporal window. If bilateral hyperechoic signal were present, they were recorded separately; aSNHmax was adequate to the larger aSNH of the two sides (right or left), or in case of an insufficient bone window on one side. The ratio of aSNH to the area of midbrain (S/M) was calculated using the formula: S/M = [(left aSNH + right aSNH)/area of midbrain] * 100%. The Kappa consistency test and ICCs were employed to test interobserver agreement for SN grading and aSNH calculation, respectively.

TCS-MR fusion imaging

The ultrasound machine was equipped with Virtual Navigator procedures, which comprised a position sensing unit mounted on the ultrasound unit, a magnetic field transmitter (MFT), and a sensor attached to the probe via a specific holder. Before fusion imaging, reattach the aforementioned automatic tracker to the patient’s forehead, ensuring that its position and orientation were consistent with those during the MRI scan. The maximum distance between the MFT and the ultrasound machine was 66 cm, while the maximum distance and height difference between the MFT and the tracker were 28 cm and 30 cm, respectively. The scanning procedure was in accordance with previous studies4,13,17. The patient’s head position was initially registered with the tracking system, resulting in a near-exact match between the patient’s head position (equivalent to the real-time TCS image coordinates) and the MRI dataset. The MRI and TCS images were then precisely overlaid using a fine-tuning process. To do this, the frozen MRI and overlapped TCS images could be dragged manually on the monitor. Special attention was paid to precise superimposition of the following structures, which were clearly visible on both MRI and TCS listed in the same order, as previously reported13: the third ventricle and frontal horns, the middle and posterior cerebral arteries ipsilateral to insolation, the pineal gland, the midbrain and quadrigeminal cistern, and the aqueduct (Supplementary Fig. 1). Repeat this procedure until the optimal superimposition is achieved, which is then maintained thanks to continuous position tracking with the two sensors installed on the patient’s head and the ultrasound transducer at a signal quality of 9~10 points. During a real-time TCS examination, the MRI volume automatically scrolls to display corresponding planes with the Virtual Navigator. The patient’s head remains stationary throughout the procedure. Images shown during the examination consist of both TCS and MRI images, which can be viewed side-by-side or overlapped. Fusion imaging was performed by a radiologist (C. H.) who was blinded to clinical information, following two weeks of fusion imaging training prior to the experiment. Dynamic video footage from the basal ganglia level to the pontine level was captured for further analysis.

Region of interest selection and Greyscale median analysis

Due to the current lack of software configurations on ultrasound equipment for synchronous outlining ROI of arbitrary shape and size on MRI and TCS images in fusion mode, ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) was utilized. Initially, the desired ROIs were segmented on MRI and then displayed simultaneously on TCS using coordinate position relationship5,35. A single investigator (H.B. L.) conducted greyscale median analysis of the ROI without knowledge of the visual results, following standardization procedure as previously reported36. Three planes on TCS corresponding to MRI were selected for greyscale median analysis based on fusion images and anatomic landmarks: the plane with the largest area of the red nucleus on MRI, the plane with the largest aSNH, and the plane where the red nucleus is barely identified, referred to as planes of SN1, SN2, and SN3, respectively. Planes SN1 and SN3 denote rostral and caudal levels, as per a previous study15. ROIs of SN and red nucleus in plane SN1, SN, red nucleus, and hyperechogenic signal in plane SN2, and SN in plane SN3 were segmented. Different colors were used to mark hyperechoic signals within plane SN2 occurring in nuclei other than those containing the SN. Pixel and echogenicity values of different ROIs were documented. The maximum echogenicity indices of SN1 were compared to determine the higher echogenicity of the two sides (right or left), or in cases of an inadequate bone window on one side. After a 2-week interval, images from 20 participants were randomly selected for repeat segmentation, and the results underwent an ICC test.

Clinical data collection

Age, gender, disease duration, body mass index, and history of drinking and smoking were collected from all participants. Each individual with PD underwent a detailed series of neurological examinations, which included the UPDRS-III and H-Y staging (early stage: H-Y staging ≤2.5; middle-late stage: H-Y staging ≥3). These neuropsychological examinations were completed by a single neurologist (F. N.), with more than five years of experience handling patients with movement disorders. In cases where a definitive diagnosis could not be made, a senior specialist (X.M. W.) with over 10 years of experience in treating movement disorders patients would provide the diagnosis. Prior to the clinical assessments, patients had refined from taking antiparkinsonian medications for at least 12 h.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was determined using the primary objective (evaluation the procedure’s viability) and referring previous study4. A sample size of 45 was defined assuming a success rate of 95%, a confidence level of 95%, and a margin of error of 5%. The inclusion of 84 participants in the PD group provides sufficient power to account for missing data due to insufficient bone windows. The measurement data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, whereas discrete variables are expressed as percentages. Differences between groups were compared using unpaired independent t-tests for continuous variables with normal distributions, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables without normal distribution, and the Pearson chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Individual missing data were imputed linearly from adjacent measurements rather than deleted. ROC curves were plotted, and the AUC, as well as the sensitivity and specificity, were calculated for the cutoff points used to diagnose PD. Spearman correlation analysis was used to explore the associations between variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were applied to assess the relationship between clinical variables and fusion imaging findings, variables with a significant trend (P < 0.1) in the univariate analysis were entered in the multivariable analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., USA).

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article available from the corresponding author under reasonable request.

References

Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459–480 (2019).

Hou, C. et al. A nomogram based on neuron-specific enolase and substantia nigra hyperechogenicity for identifying cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 14, 3581–3592 (2024).

Berg, D. et al. Transcranial sonography in movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 7, 1044–1055 (2008).

Kozel, J. et al. Echogenicity of Brain Structures in Huntington’s Disease Patients Evaluated by Transcranial Sonography - Magnetic Resonance Fusion Imaging using Virtual Navigator and Digital Image Analysis. Ultraschall Med. 44, 495–502 (2023).

Biondetti, E. et al. The spatiotemporal changes in dopamine, neuromelanin and iron characterizing Parkinson’s disease. Brain 144, 3114–3125 (2021).

Lakhani, D. A. et al. Diagnostic utility of 7T neuromelanin imaging of the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 13 (2024).

Bergsland, N. et al. Ventral posterior substantia nigra iron increases over 3 years in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 34, 1006–1013 (2019).

Ahmadi, S. A. et al. Analyzing the co-localization of substantia nigra hyper-echogenicities and iron accumulation in Parkinson’s disease: A multi-modal atlas study with transcranial ultrasound and MRI. NeuroImage. 26, 102185 (2020).

Kern, R. et al. Multiplanar transcranial ultrasound imaging: standards, landmarks and correlation with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 31, 311–315 (2005).

Fuerst, B. et al. Automatic ultrasound-MRI registration for neurosurgery using the 2D and 3D LC(2) Metric. Med. Image Anal. 18, 1312–1319 (2014).

Xiao, Y. et al. Evaluation of MRI to Ultrasound Registration Methods for Brain Shift Correction: The CuRIOUS2018 Challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 777–786 (2020).

Wu, D. F. et al. Using Real-Time Fusion Imaging Constructed from Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging for High-Grade Glioma in Neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 125, e98–e109 (2019).

Walter, U. et al. Magnetic resonance-transcranial ultrasound fusion imaging: A novel tool for brain electrode location. Mov. Disord. 31, 302–309 (2016).

Ahmadi, S. A. et al. 3D transcranial ultrasound as a novel intra-operative imaging technique for DBS surgery: a feasibility study. Int. J. Comput. Assist Radio. Surg. 10, 891–900 (2015).

Lee, H. et al. Differential Effect of Iron and Myelin on Susceptibility MRI in the Substantia Nigra. Radiology 301, 682–691 (2021).

Heim, B. et al. Differentiating Parkinson’s Disease from Essential Tremor Using Transcranial Sonography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 1115–1123 (2022).

Skoloudik, D. et al. Digitized Image Analysis of Insula Echogenicity Detected by TCS-MR Fusion Imaging in Wilson’s and Early-Onset Parkinson’s Diseases. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 842–848 (2020).

Ahmadi, S. A. et al. Midbrain segmentation in transcranial 3D ultrasound for Parkinson diagnosis. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 14, 362–369 (2011).

Pauly, O. et al. Detection of substantia nigra echogenicities in 3D transcranial ultrasound for early diagnosis of Parkinson disease. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 15, 443–450 (2012).

Hagenah, J. et al. Life-long increase of substantia nigra hyperechogenicity in transcranial sonography. Neuroimage 51, 28–32 (2010).

Skoloudik, D. et al. Transcranial sonography of the substantia nigra: digital image analysis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 35, 2273–2278 (2014).

Shi, C. H. et al. A novel RAB39B gene mutation in X-linked juvenile parkinsonism with basal ganglia calcification. Mov. Disord. 31, 1905–1909 (2016).

Berg, D. et al. Microglia activation is related to substantia nigra echogenicity. J. Neural Transm. 117, 1287–1292 (2010).

Liu, Z. et al. Iron deposition in substantia nigra: abnormal iron metabolism, neuroinflammatory mechanism and clinical relevance. Sci. Rep. 7, 14973 (2017).

Prasuhn, J. et al. Neuroimaging Correlates of Substantia Nigra Hyperechogenicity in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 1191–1200 (2022).

Biondetti, E. et al. Spatiotemporal changes in substantia nigra neuromelanin content in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 143, 2757–2770 (2020).

Zhu, S. et al. Clinical Features in Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Hyperechogenicity in Substantia Nigra: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 18, 1593–1601 (2022).

Iranzo, A. et al. Left-hemispheric predominance of nigrostriatal deficit in isolated REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 94, e1605–e1613 (2020).

Melamed, E. et al. Taking sides: is handedness involved in motor asymmetry of Parkinson’s disease? Mov. Disord. 27, 171–173 (2012).

Tolosa, E. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 20, 385–397 (2021).

Kang, H. Y. et al. A comprehensive benchmarking of a U-Net based model for midbrain auto-segmentation on transcranial sonography. Comput Methods Prog. Biomed. 258, 108494 (2025).

Kang, H. et al. Automatic Transcranial Sonography-Based Classification of Parkinson’s Disease Using a Novel Dual-Channel CNXV2-DANet. Bioengineering 11, 889 (2024).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Bartova, P. et al. Transcranial sonography in movement disorders. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc Czech Repub. 152, 251–258 (2008).

Lehericy, S. et al. 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging: a closer look at substantia nigra anatomy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 29, 1574–1581 (2014).

Yu, J. L. et al. A comparison of ultrasound echo intensity to magnetic resonance imaging as a metric for tongue fat evaluation. Sleep 45, zsab295 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study has received the funding by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82271995); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2025ZNSFSC1753); Luzhou Science and Technology Program (No. 2024JYJ047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chao Hou: conception, study design, drafting, and funding support. Wei Zhang: data collection and analysis, and data interpretation. Hong-bing Li, Shuo Li, and Fang Nie: data collection and analysis. Xue-mei Wang: conception, data collection, and revision. Wen He: revision, final approval, and funding support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, C., Zhang, W., Li, HB. et al. Spatial variations and precise location of substantia nigra hyperechogenicity in Parkinson’s disease using TCS-MR fusion imaging. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 78 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00910-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-00910-7