Abstract

This study aimed to examine variations in iron deposition, neuromelanin (NM) content, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate-glutamine complex (Glx) levels within the nigrostriatal pathway in early-stage Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients with and without Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD). Twenty-two early-stage PD patients with RBD (PD-RBD), 33 without RBD (PD-nRBD), and 36 healthy controls (HC) were prospectively recruited and underwent 3 T MRI and 1H-MRS scans. GABA levels in the left basal ganglia were elevated in PD-nRBD versus HC (P = 0.014), whereas they were decreased in the PD-RBD relative to the PD-nRBD (P = 0.018). Iron deposition and NM content in the bilateral substantia nigra (SN) showed no differences between PD subgroups. Despite similar SN iron and NM content, the GABAergic system alteration provides novel insights into the pathophysiology of RBD in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD) is characterized by recurrent dream-enacting behaviors, leading to abnormal sleep-related motor behaviors, and the absence of muscle atonia during REM sleep1. RBD is strongly associated with α-synucleinopathies and serves as a prodromal marker for Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other synucleinopathies2,3,4. Meanwhile, RBD is a common non-motor symptom in PD patients, with a prevalence as high as 77%5. Compared to PD patients without RBD, those with RBD exhibit more severe motor and non-motor symptoms, along with a poorer quality of life and worse prognosis6. Moreover, a long-term cohort study has demonstrated that the prevalence of RBD increases over time following a PD diagnosis, and that RBD does not improve with dopaminergic treatment7.

The damage to the nigrostriatal system plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of PD8. Both PD patients and idiopathic RBD patients show a reduction in neuromelanin (NM) volume and signal intensity9,10,11 and higher iron deposition in the substantia nigra (SN)12. A few recent studies have explored NM signal intensity of the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex in PD patients with RBD showing that the signal intensity and contrast were lower in PD with RBD than those without RBD13,14. However, to our knowledge, it remains unclear whether the alterations of iron and NM in SN are involved in RBD of PD patients. On the other hand, the initiation and maintenance of REM sleep is closely linked to glutamatergic/γ-aminobutyric acidergic neurons in the brainstem. Previous animal studies showed that the reduction of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentration in the nucleus raphe magnus and the ventral gigantocellular is related to RBD15. A recent in vivo study demonstrated that glutamatergic signaling is altered in PD patients with RBD, despite the fact that no glutamatergic metabolite changes were observed16. However, the changes in brain GABA levels in PD patients with and without RBD remain unknown. Elucidating the changes in iron, NM, GABA, and glutamate (Glu) of RBD in PD patients may provide deeper insights into the pathophysiological processes underlying the neural mechanisms associated with RBD in PD.

Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) and NM-sensitive magnetic resonance image (NM-MRI) are well-established imaging methods to quantify iron deposition and NM content separately. NM-MRI signal intensity in the SN is closely correlated with the number of NM-containing neurons and provides quantitative information about NM concentration17,18,19. Additionally, MR spectroscopy (MRS) provides a non-invasive imaging method to assess neuro-metabolites in vivo, offering insights into intracellular metabolic states. Spectral editing sequences such as the Meshcher-Garwood Point Resolved Spectroscopy (MEGA-PRESS) approach provide an advanced MRS technique that can be used to quantify GABA and glutamate-glutamine complex (Glx) levels in vivo20.

This study tested the hypothesis that alterations in iron deposition, NM content, and the balance of the glutamatergic/GABAergic system within the nigrostriatal pathway may be associated with the presence of RBD in patients with early-stage PD.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects

A total of 99 subjects were enrolled, including 59 PD patients and 40 age- and sex-matched health controls (HCs). Eight subjects (4 PD and 4HCs) were excluded for failing to meet the quality metrics of the MEGA-PRESS spectra:fitting errors should be less than 15% and full width at half maximum (FWHM) values should be below 15 Hz. The Cramer-Rao lower bounds (CRLB) of GABA and Glx <20% were chosen for further investigation (Supplementary Table S1). Consequently, the final cohort comprised 55 early-stage PD patients (with a Hoehn-Yahr stage 1–2.5) and 36 HCs. Based on the RBD questionnaire-Hong Kong (RBDQ-HK) scale, the PD patients were classified into two subgroups: 22 PD with RBD (PD-RBD) and 33 PD without RBD (PD-nRBD). Since the NM-MRI sequence was scanned at the end of the entire protocol, some subjects were unable to complete it or the data was not usable due to motion artifacts. Therefore, NM-MRI data were only available for 84 of the 91 subjects (36/36 HCs, 29/33 PD-nRBD, and 19/22 PD-RBD).

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. No differences were found in sex (p = 0.095) and age (p = 0.247) among the three groups. The disease duration, age at onset, levodopa equivalent daily dose and motor subtypes distribution showed no differences between PD-nRBD and PD-RBD groups. MDS-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part I scores (p = 0.039) and RBDQ-HK scores (p < 0.001) were significantly lower in the PD-nRBD group compared to the PD-RBD group. No significant differences were observed in other recorded clinical scales including motor symptoms (rigidity, bradykinesia and tremor) and non-motor symptoms such as cognitive function, depression, quality of life, and sleep quality between the two PD subgroups (all p > 0.05). Within the PD-RBD group, RBD symptom duration was 4.09 ± 2.37 years, and 54.5% (12/22) of patients were identified as post-motor-onset RBD.

Differences in the iron, NM, GABA, and Glx measurements

Compared to HC, both the PD-RBD and PD-nRBD groups showed significantly higher iron content in the left SN (all p < 0.05) and lower CRNM in bilateral SN (all p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed between PD-RBD and PD-nRBD groups for either iron or NM measurements in the SN.

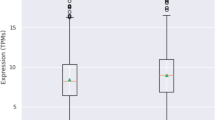

MEGA-PRESS quality metrics (fitting error and FWHM) showed no significant differences among the groups, and no significant differences were found in the fractions of gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) within the VOI (Table 1). After adjusting for the effects of age, sex, and fraction of GM, GABA + /water levels in the left basal ganglia region were significantly different among the groups. Post hoc analysis revealed that PD-nRBD had significantly higher GABA + /water levels in the left basal ganglia compared to the HC group (PD-nRBD: 2.970 ± 0.498 (i.u) vs HC: 2.627 ± 0.471 (i.u), p = 0.014); the PD-RBD group showed significantly lower GABA + /water levels than PD-nRBD group (PD-RBD: 2.578 ± 0.363 (i.u) vs PD-nRBD: 2.970 ± 0.498 (i.u), p = 0.018), but no significant difference when compared with the HC group (p > 0.05). There was no significant difference in Glx/water level within the left basal ganglia among three groups (p > 0.05). All group comparison results for iron, NM, GABA, and Glx were conducted with Bonferroni correction and are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Iron deposition (left: a, right: b) and neuromelanin contrast ratio (left: c, right: d) in the SN. The GABA (e) and Glx (f) levels in the left basal ganglia among HC, PD-nRBD, and PD-RBD. Abbreviations: MRI magnetic resonance imaging, MRI magnetic resonance spectroscopy, HC healthy control, PD-nRBD Parkinson’s disease patients without Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder, PD-RBD Parkinson’s disease patients with Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder, SN substantia nigra, GABA γ-aminobutyric acid, Glx glutamate-glutamine complex, institutional units, i.u ns, no significance.

The differential diagnostic performance of GABA for PD with or without RBD

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed that the GABA + /water level in the left basal ganglia effectively differentiated PD patients with and without RBD, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.744 (95% CI: 0.608, 0.852) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Correlations between GABA level in basal ganglia and age

Spearman correlation analysis revealed no significant correlation between GABA level in basal ganglia and age in the entire PD group, PD subgroups (PD-nRBD and PD-RBD), or HC (Supplementary Table S2). In partial correlation analyses controlling for fraction of GM, GABA level in the basal ganglia likewise demonstrated no significant correlation with age (all p > 0.05).

Correlations between GABA level in basal ganglia and non-motor clinical scales and disease severity

In the entire PD cohort, Spearman correlation revealed a significant negative association between basal ganglia GABA levels and HAMD-17 scores (rho = −0.358, p = 0.008). This association persisted in partial correlation analyses after controlling for age (r = −0.303, p = 0.28) and further multivariate correction for age, sex, disease duration, age at onset, and fraction of GM (r = −0.360, p = 0.011) (Supplementary Fig. S1). A significant inverse association between GABA level in basal ganglia and depression severity (HAMD-17 scores) was also observed in PD-nRBD group (Spearman: rho = −498, p = 0.003; age-controlled partial correlation: r = −0.516, p = 0.002; multivariate-controlled partial correlation: r = −0.628, p < 0.001), but not in PD-RBD group (all p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S3).

No significant correlation between GABA+ level in basal ganglia and RBDQ-HK was observed in either the PD-RBD or PD-nRBD groups. However, a significant negative association was observed between GABA levels in the basal ganglia and RBDQ-HK in all PD patients (Spearman: rho = −340, p = 0.11; age-controlled partial correlation: r = −0.274, p = 0.047; multivariate-controlled partial correlation: r = −0.283, p = 0.049) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In all PD patients, GABA levels in the basal ganglia showed a significant positive correlation with cognitive ability in both Spearman correlation analysis (rho = 0.268, p = 0.048) and multivariate-adjusted partial correlation controlling for age, sex, age at onset, disease duration and fraction of GM (r = 0.282, p = 0.049) (Supplementary Fig. S1), but no significant correlation was observed in PD-RBD and PD-nRBD groups.

Furthermore, GABA levels in the basal ganglia showed no significant associations with motor severity (MDS-UPDRS-III scores), quality of life (PDQ-39), or sleep dysfunction (PDSS) either in Spearman correlation or partial correlation analyses (all p > 0.05).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate iron, neuromelanin and GABA/Glx alterations in the nigrostriatal system using QSM, NM-MRI, and MEGA-PRESS in early-stage PD patients with and without RBD. The results indicate that, while there are no differences in iron and NM content in the SN between PD-RBD and PD-nRBD patients, left basal ganglia GABA levels are reduced in PD-RBD patients compared to PD-nRBD patients. These findings suggest that despite comparable nigral iron and NM content, basal ganglia GABA levels exhibit divergent alterations in early-stage PD patients with versus without RBD that are elevated in PD-nRBD yet normalized in PD-RBD group. This symptom related GABAergic abnormality provides novel insights into RBD pathophysiology in PD.

Both the PD-nRBD and PD-RBD groups showed higher iron deposition in the left SN and lower CRNM in bilateral SN compared to the HC group. However, no significant differences were observed between the PD-RBD and PD-nRBD groups in these measures. These results are consistent with those reported in previous studies21,22. Elevated iron levels and dopaminergic neuron degeneration in the SN are common pathophysiological features of PD, regardless of comorbidities, including non-motor symptoms21. Mašková et al. found SN echogenicity which may reflect the iron content does not differ between PD with/without RBD23. Additionally, idiopathic RBD, as a prodromal stage of PD, also exhibits increased iron levels and reduced NM signal intensity in the SN11,12. However, in this study, differences in iron deposition between the HC and PD subgroups were observed only in the left SN, not in the right SN. This may be attributed to the predominantly affected side in the recruited cohorts, as 23 of the 33 PD-nRBD patients and 16 of the 22 PD-RBD patients exhibited right-sided dominance. Postmortem and neuroimaging studies have shown greater neuronal loss in the contralateral side of brain relative to the predominantly affected side of the body24,25. Additionally, all PD patients in this study were in the early stages (Hoehn-Yahr stage 1–2.5), which may also account for the insignificant findings in the right SN.

In the MRS investigation, PD-nRBD patients exhibited significantly higher GABA levels in the left basal ganglia compared to the HC group. This finding is consistent with animal studies that showed a significant increase in GABA levels in the affected striatum, as measured by MRS26,27,28. In a non-human primate model of PD, isolated specimens from the injured striatum also showed significantly higher GABA concentrations in the affected striatum compared to the contralateral side and the blank control group29. Experimental studies demonstrated that dopaminergic denervation upregulates glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) mRNA expression and enhances GAD enzymatic activity30,31. As the rate-limiting enzyme in GABA synthesis, this GAD-mediated cascade consequently elevates GABA production in the striatum. Although it remains unclear that elevated GABA in the basal ganglia is the direct reflection or a compensatory change followed by dopaminergic denervation28. What is certain is that an increase in GABA levels in the basal ganglia is an early change in PD. Subsequently, MRS measurements of striatal GABA levels could allow for the detection of early nigrostriatal defects prior to outright neurodegeneration27. However, previous in vivo MRS studies on GABAergic changes in PD have not reached a consensus. Specifically, Elmaki et al.32 demonstrated that, compared with HCs, PD patients exhibit significantly lower GABA levels in the left basal ganglia. In contrast, O’Gorman et al.33 reported higher GABA levels in the basal ganglia of PD patients. This discrepancy may be attributed to the heterogeneity of PD, as previous studies have generally examined PD as a whole rather than focusing on its subtypes, and these studies didn’t report the non-motor symptoms in their PD cohorts. Further investigations are warranted to validate the trajectory of GABA level in PD patients with different statuses and subtypes and whether the alteration in striatum GABA level could be used as a sensitive biomarker for PD diagnoses.

Interestingly, PD-RBD patients exhibited notably lower GABA levels in the basal ganglia compared to PD-nRBD patients, but no significant difference was observed when compared to the HC group in this study. That is to say, GABA levels in the basal ganglia are elevated in PD patients without RBD but normalized in PD patients with RBD. We speculated that the normalization of GABA level in basal ganglia in PD-RBD is GABAergic dysfunction relative to the PD-nRBD may reflect the direct impact of pathological progression or compensatory failure on the GABAergic system of the basal ganglia. Previous research showed the increase of GABA in the striatum may be a strategy to protect neurons from excitotoxic injury after the exhaustion of striatum dopamine28,34. In the early PD or the stage without RBD, the GABAergic system in the basal ganglia may undergo compensatory upregulation to counteract the circuit imbalance caused by dopamine deficiency. This upregulation may be a protective mechanism that maintains relatively normal motor function or delays certain non-motor symptoms such as RBD. PD patients with RBD symptoms exhibit a more aggressive progression of neurodegeneration35. Thus, the presence of RBD in PD patients may signify greater pathological burden within basal ganglia structures which leads to exhaustion of early compensatory mechanisms, resulting in a reduction of GABA levels from a compensatory elevated state towards a range approximating normal levels in PD-RBD. Our finding indicates the basal ganglia GABAergic function may differ depending on the presence or absence of RBD symptom which provides crucial neurochemical evidence for the heterogeneity of PD. The existence of RBD may delineate a PD subtype characterized by more extensive pathological involvement36. Notably, previous research has demonstrated a pooled RBD prevalence of 46% in PD patients, with its occurrence associated with older age and longer disease duration37. In the current study, we focused specifically on early-stage PD patients (Hoehn-Yahr stages 1–2.5). With the progression of disease and the increasing of age, the PD-nRBD patients may potentially develop RBD. Therefore, a longitudinal study is imperative to explore the dynamic pattern of GABAergic system alteration in PD patients.

In line with Doppler et al.’s findings16, we also did not observe differences in Glx levels in the PD-RBD group when compared to either PD-nRBD group or the HC group. However, this does not imply that the glutamatergic system is unaffected, as alterations in glutamatergic signaling at the receptor level may still occur in PD-RBD patients, despite normal Glx concentration16. From a methodological perspective, using the 3 T MEGA-PRESS sequence, we could only quantify the content of Glx (the combination of Glu and Gln) rather than directly quantifying Glu levels. Therefore, the negative Glx findings in this study do not rule out potential differences in Glu levels in the left basal ganglia among the three groups. Future studies employing ultra-high-field imaging, such as 7 T, are necessary to quantitatively explore Glu levels in PD patients with or without RBD.

Previous research demonstrated that the aging-related trajectory of GABA across the lifespan is characterized by a fairly quick increase in GABA during development, followed by a flattening during adolescence and by a subsequent slow decrease with aging38. In the present study, we explored the association between age and basal ganglia GABA levels in PD and HC and found no significant correlations. This discrepancy could result from the relatively narrow range of age and small sample size. Future studies should include large samples across different age groups to investigate age-related changes in GABA with the basal ganglia.

In this study, we performed an exploratory correlation analysis between GABA levels—the only measurement that differed between PD patients with and without RBD—and clinical scales including non-motor features and motor severity in the entire PD cohort and PD subgroups. Notably, in all early-stage PD patients, decreased GABA levels in the left basal ganglia were significantly correlated with the severity of RBD, nevertheless, this correlation wasn’t observed in PD-RBD group. The significant negative correlation between GABA and RBDQ-HK scores observed across the entire PD cohort must be interpreted with considerable caution. This association is highly susceptible to confounding by group status (PD-RBD vs. PD-nRBD), a phenomenon known as Simpson’s paradox. The substantial difference in both mean GABA levels and mean RBDQ-HK scores between PD-RBD and PD-nRBD patients is the primary driver of this aggregate-level correlation. Our subgroup analyses (though limited by sample size) suggest that this linear correlation pattern does not hold consistently within the PD-RBD or PD-nRBD groups individually. This indicates that the whole-group correlation likely reflects the group separation rather than a simple relationship between GABA and RBD symptom severity. Moreover, the ROC analysis in the present study showed that the GABA + /water level cannot effectively distinguish PD-nRBD from PD-RBD (AUC = 0.744). But in clinical research, the benzodiazepine clonazepam, known to improve sleep disorders in PD patients, has been shown to enhance brain GABAergic neurotransmission39,40. Therefore, the association between the GABA levels and RBD symptoms in PD patients warrants further investigation. Future studies should address the following key aspects: (1) employ sufficiently large samples to determine whether reduced GABA levels exhibit a threshold effect on severity of RBD symptom; (2) recruit longitudinal cohorts of PD-nRBD to clarify: (a) whether the association between GABA and RBD symptoms exists prior to RBD onset; (b) whether reduced GABA levels can predict the occurrence of RBD in those patients who subsequently develop to PD-RBD; and (3) conduct longitudinal studies in PD-RBD patients to determine whether reduced GABA levels demonstrate a severity relationship with RBD.

Additionally, the severity of depression appeared to increase as GABA levels in the basal ganglia decreased in PD patients. A clinical trial demonstrated that a positive allosteric modulator of GABA type A receptors reduces depressive symptoms41. Moreover, cognitive function was positively correlated with GABA levels. Previous studies found that decreased GABA levels are associated with executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment42 and that the positive allosteric modulator of GABA type A receptors attenuates the cognitive deficits in rats43. These findings support the view that the GABAergic system is closely associated with the non-motor symptoms in PD44. Regulating the GABA signaling could be a new therapeutic approach to alleviate the non-motor burdens, and the role of GABA in PD management warrants further investigation.

This study has several potential limitations. First, RBD symptoms were assessed using the RBDQ-HK scores instead of polysomnography with synchronized audiovisual recordings, which is the gold standard for confirming RBD. Second, this is a cross-sectional study; the results of this study need further confirmation with longitudinal research. Third, idiopathic RBD patients were not included, which may limit our ability to interpret the underlying mechanisms of PD-RBD. Moreover, our MRS data were acquired solely in the left basal ganglia. Future studies should assess bilateral glutamatergic/GABAergic dynamics to comprehensively elucidate the pathological changes in PD-RBD.

In conclusion, GABA levels in the basal ganglia exhibit divergent patterns in early PD patients with versus without RBD. Compared to changes in iron deposition or dopaminergic neuron loss, GABA levels appear to play a more prominent role in the manifestation of RBD symptoms at this stage. These findings indicate that the GABAergic system alteration provides novel insights into the pathophysiology of RBD symptoms in PD.

Methods

Subjects and clinical assessment

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. All subjects agreed to participate in the study and written informed consent was obtained. PD patients were consecutively recruited from the Movement Disorders Clinic of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine from October 2023 to October 2024 based on the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) clinical diagnostic criteria for PD45 and the modified Hoehn-Yahr stage46,47 ranging from 1 to 2.5 with the exclusion criteria: (1) a history of central neural system diseases such as brain tumor, head trauma or any other type of psychiatric disorders; (2) a history of medication known to cause parkinsonism or affect clinical assessment; and (3) any contraindications to MRI.

Clinical data were collected for all patients, including the age at onset, disease duration, levodopa equivalent daily dose, modified Hoehn and Yahr stage, and MDS-UPDRS parts I to IV. The severity of motor symptoms, including rigidity (3.3), bradykinesia (3.4–3.8), and tremor (3.15–3.17), was assessed based on specific MDS-UPDRS-III items. The motor subtypes including tremor dominant (TD), postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD) and indeterminate were recorded based on the MDS-UPDRS scores48. Non-motor symptoms such as cognitive function, depression, quality of life, and sleep quality were evaluated using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17), 39-Item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), and Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS). RBDQ-HK49 was used to assess RBD symptoms. This questionnaire contained 13 items and had a best cut-off score of 18/19 for diagnosing RBD. It has been validated as a reliable tool with reasonable specificity and sensitivity for detecting RBD49. In this study, PD patients were classified into two groups based on their RBDQ-HK scores: PD with RBD (PD-RBD, RBDQ-HK score ≥19) and PD without RBD (PD-nRBD, RBDQ-HK score <19).

All HCs were recruited from the health examination center from October 2023 to November 2024 according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) no personal or family history of neurological or psychiatric diseases; (2) no history of taking psychotropic drugs; (3) no cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease; and (4) no contraindications for MRI. All HCs were assessed for cognitive impairment using the MoCA, and only those with scores ≥26 were included in the study50.

Magnetic resonance data acquisition

All MR data were acquired using a 3.0 T scanner (Elition X, Philips Healthcare) with a 32-channel head coil. All MR data of PD patients were collected in the medicine-off state (med-off, 12 h discontinuation of levodopa). A 3D 5-echo strategically acquired gradient echo (STAGE) imaging protocol was employed to obtain the QSM data, with the following parameters: TE1 = 3.0 ms, ΔTE = 4.7 ms, TR = 27 ms, flip angles (FA) = 30° and 6°, pixel bandwidth = 362 Hz, field of view = 256 × 192 × 150 mm³, slice thickness = 1.34 mm, and original spatial in-plane resolution = 0.67 × 1 mm², which was subsequently interpolated to 0.67 × 0.67 mm². The total scanning time was 7 min, including both FA scans. A 3-echo 3D GRE sequence with magnetization transfer contrast (MTC-GRE) was used to acquire NM-MRI with the following parameters: TE1 = 5.2 ms, ΔTE = 10 ms, TR = 57.5 ms, flip angle = 30°, bandwidth = 128 Hz/pixel, matrix size = 384 × 288, slice thickness = 2 mm, and original spatial in-plane resolution = 0.67 × 0.67 mm².

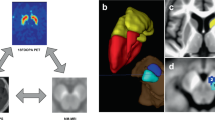

The T1-weighted (T1W) image (FA = 30°) acquired using the STAGE protocol served as the anatomical reference for positioning the MRS voxel. Spectra were collected from a single voxel located in the left basal ganglia region, which includes the caudate nucleus (CN), putamen (PUT), and globus pallidus (GP) (Fig. 3), regions associated with the occurrence of RBD in PD51. MRS data were acquired using the MEGA-PRESS sequence52 with the following parameters: voxel size = 30 × 30 × 30 mm³ (left basal ganglia); TR/TE = 2000/68 ms; 1024 points with a spectral width of 2000 Hz; number of signal averages = 288 (both ON and OFF spectra were repeated by 144 times), readout duration = 512 ms; VAPOUR (variable power radiofrequency pulses with optimized relaxation delays) water suppression; edit on/off frequencies = 1.89/7.46 ppm; 9 dynamics with 16 signal averages per dynamic, acquisition time = 9 min 54 s.

Abbreviations: PDWI proton density weighted image, T1WI T1 weighted image, FA flip angle, STAGE strategically acquired gradient echo, QSM quantitative susceptibility mapping, DGM deep gray matter, GM gray matter, WM white matter, GABA + /water γ-aminobutyric acid level relative to water, Glx/water glutamate-glutamine level relative to water, NM-MR neuromelanin sensitive magnetic resonance image, CRNM contrast ratio of neuromelanin.

QSM reconstruction and analysis

The QSM data was reconstructed using STAGE 2.7 software (SpinTech MRI, Bingham Farms, MI, USA) based on the methods introduced by Chen et al.53 and Wang et al.54. In this study, 8 deep gray matter (DGM) regions including bilateral CN, PUT, GP, and SN were automatically segmented as regions of interest (ROIs) based on the method established in the previous study55 (Fig. 3). The masks of CN, PUT, and GP for individual participants were used to refine the gray matter (GM) mask during MRS processing. The mean susceptibility values of the bilateral SN were evaluated as indicators of iron content level.

NM-MRI processing and analysis

The bilateral SN and background regions in NM-MRI images were automatically segmented using the midbrain template created by Jin et al.55 based on a dynamic programming algorithm56. The crus cerebri were used for the background region (Fig. 3). The intensity of SN neuromelanin and the background was measured following the methodology outlined in a previous study57. Specifically, the contrast ratio (CR) of the bilateral SN neuromelanin was calculated as follows: \({{CR}}_{\mathrm{NM}}=\frac{\left({S}_{\mathrm{SN}}\,-\,{S}_{\mathrm{background}}\right)}{{S}_{\mathrm{background}}},\) where \({S}_{\mathrm{SN}}\) represents the mean signal intensity of the SN, and \({S}_{{background}}\,\) represents the mean signal intensity of the background region.

MEGA-PRESS processing

MEGA-PRESS data were processed and analyzed using the GANNET 3.1 software (https://github.com/markmikkelsen/Gannet)58. Specific processing steps included 3 Hz line broadening, frequency and phase correction, outlier rejection, time averaging, eddy current correction59, and subtraction of the “on” and “off” spectra to obtain the edited difference spectrum. The edited difference spectrum was modeled to quantify GABA (referred to as GABA + ) and Glx signals relative to water (institutional units, i.u.)60. The edited signal at 3.02 ppm (parts per million) contains not only the contribution form GABA but also the macromolecules and homocarnosine, therefore labeled as GABA + 61. The MEGA-PRESS spectra were visually inspected for spectral artifacts. The CRLB was determined by Monte Carlo simulations to assess the accuracy of the fitting62. The CRLB values (using a cut-off of <20%) for GABA and Glx were obtained and used as quality measures of postprocessing model fitting (Supplementary materials). Only those spectra with fitting errors less than 15% and FWHM values below 15 Hz were included in the subsequent analyses. The details including scanner hardware, acquisition and processing parameters used for in vivo MRS are summarized in Supplementary Table S4, in accordance with experts’ recommendations63. An example spectrum acquired from the left basal ganglia is shown in Fig. 3. The initial masks for GM, WM, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the MRS voxel were generated using SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/download/). This process involved registering the MRS voxel to the 3D T1W image and segmenting the 3D T1W image into GM, WM, and CSF. Subsequently, the DGM was segmented as described in the QSM data processing section to generate the mask for subcortical structures. The initial GM, WM, and CSF masks were then combined with the DGM mask derived from the automatic segmentation of QSM data to create a refined GM region using the SimpleITK package64 in Python 3.8. Finally, the volume fractions of GM, WM, and CSF within the MRS voxel were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, Python, and MedCalc. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data normality. Differences in age, sex and motor subtypes distribution between groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance or chi-squared test. Comparisons of clinical data between groups were performed using independent-sample t-tests for normally distributed variables and nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney U test) for non-normally distributed variables. Differences in QSM, NM-MRI and MEGA-PRESS measurements across groups were evaluated using the general linear model, with age, sex, and/or the fraction of GM in the spectra voxel as covariates. Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons. A ROC curve was generated to evaluate the performance of the GABA + /water ratio in distinguishing PD patients with or without RBD. Age-related change of GABA level in basal ganglia was assessed with Spearman’s correlations and partial correlation analysis. Additionally, existing literature44 implicates GABA in PD-related non-motor pathophysiology, Spearman’s correlations and partial correlation analysis were conducted to exploratively assessed the correlation between GABA level in basal ganglia and both the non-motor symptom scales and disease severity within PD subgroups (PD-RBD, PD-nRBD) and the full PD cohort. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schenck, C. H., Bundlie, S. R., Ettinger, M. G. & Mahowald, M. W. Chronic behavioral disorders of human REM sleep: a new category of parasomnia. Sleep 9, 293–308 (1986).

Miglis, M. G. et al. Biomarkers of conversion to α-synucleinopathy in isolated rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder. Lancet Neurol. 20, 671–684 (2021).

Boeve, B. F. et al. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain 130, 2770–2788 (2007).

Stefani, A. et al. From mechanisms to future therapy: a synopsis of isolated REM sleep behavior disorder as early synuclein-related disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 20, 19 (2025).

Baumann-Vogel, H. et al. REM sleep behavior in Parkinson disease: frequent, particularly with higher age. PLoS ONE15, e0243454 (2020).

Rolinski, M. et al. REM sleep behaviour disorder is associated with worse quality of life and other non-motor features in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 85, 560–566 (2014).

Sixel-Döring, F., Zimmermann, J., Wegener, A., Mollenhauer, B. & Trenkwalder, C. The eEvolution of REM sleep behavior disorder in early Parkinson disease. Sleep 39, 1737–1742 (2016).

Kordower, J. H. et al. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 136, 2419–2431 (2013).

Huddleston, D. E. et al. In vivo detection of lateral-ventral tier nigral degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38, 2627–2634 (2017).

Pyatigorskaya, N. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers to assess substantia Nigra damage in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx149 (2017).

Biondetti, E. et al. Spatiotemporal changes in substantia nigra neuromelanin content in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 143, 2757–2770 (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Quantitative evaluation of iron content in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 35, 478–485 (2020).

García-Lorenzo, D. et al. The coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex in rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 136, 2120–2129 (2013).

Nobileau, A. et al. Neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging changes in the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex in patients with typical and atypical Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 38, 479–484 (2023).

Iranzo, A. The REM sleep circuit and how its impairment leads to REM sleep behavior disorder. Cell Tissue Res. 373, 245–266 (2018).

Doppler, C. E. J. et al. Glutamate signaling in patients with Parkinson disease with REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 102, e209271 (2024).

Trujillo, P., Aumann, M. A. & Claassen, D. O. Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI as a promising biomarker of catecholamine function. Brain 147, 337–351 (2023).

Kitao, S. et al. Correlation between pathology and neuromelanin MR imaging in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroradiology 55, 947–953 (2013).

Cassidy, C. M. et al. Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI as a noninvasive proxy measure of dopamine function in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5108–5117 (2019).

Mullins, P. G. et al. Current practice in the use of MEGA-PRESS spectroscopy for the detection of GABA. NeuroImage 86, 43–52 (2014).

Shin, C., Lee, S., Lee, J. Y., Rhim, J. H. & Park, S. W. Non-motor symptom burdens are not associated with iron accumulation in early Parkinson’s Disease: a quantitative susceptibility mapping study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 33, e96 (2018).

Mašková, J. et al. Comparative study of the substantia nigra echogenicity and 123I-Ioflupane SPECT in patients with synucleinopathies with and without REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. Med. 70, 116–123 (2020).

Mašková, J. et al. Comparative study of the substantia nigra echogenicity and (123)I-Ioflupane SPECT in patients with synucleinopathies with and without REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. Med. 70, 116–123 (2020).

Kempster, P. A., Gibb, W. R., Stern, G. M. & Lees, A. J. Asymmetry of substantia nigra neuronal loss in Parkinson’s disease and its relevance to the mechanism of levodopa related motor fluctuations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 52, 72–76 (1989).

Claassen, D. O. et al. Cortical asymmetry in Parkinson’s disease: early susceptibility of the left hemisphere. Brain Behav. 6, e00573 (2016).

Chassain, C. et al. Metabolic changes detected by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo and in vitro in a murin model of Parkinson’s disease, the MPTP-intoxicated mouse. J. Neurochem. 105, 874–882 (2008).

Coune, P. G. et al. An in vivo ultrahigh field 14.1 T 1H-MRS study on 6-OHDA and α-synuclein-based rat models of Parkinson’s disease: GABA as an early disease marker. NMR Biomed. 26, 43–50 (2013).

Gao, H.-C. et al. Metabolic changes detected by ex vivo high resolution 1H NMR spectroscopy in the striatum of 6-OHDA-iInduced Parkinson’s rat. Mol. Neurobiol. 47, 123–130 (2013).

Huang, L. et al. Comparative study of striatum GABA concentrations and magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in Parkinson’s disease monkeys. BMC Neurosci. 20, 42 (2019).

Segovia, J., Tillakaratne, N. J., Whelan, K., Tobin, A. J. & Gale, K. Parallel increases in striatal glutamic acid decarboxylase activity and mRNA levels in rats with lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway. Brain Res. 529, 345–348 (1990).

Soghomonian, J. J. & Laprade, N. Glutamate decarboxylase (GAD67 and GAD65) gene expression is increased in a subpopulation of neurons in the putamen of Parkinsonian monkeys. Synapse 27, 122–132 (1997).

Elmaki, E. E. A., Gong, T., Nkonika, D. M. & Wang, G. Examining alterations in GABA concentrations in the basal ganglia of patients with Parkinson’s disease using MEGA-PRESS MRS. Jpn J. Radio. 36, 194–199 (2018).

O’Gorman Tuura, R. L., Baumann, C. R. & Baumann-Vogel, H. Beyond dopamine: GABA, glutamate, and the axial symptoms of Parkinson disease. Front. Neurol. 9, 806 (2018).

Matthews, C. C., Zielke, H. R., Wollack, J. B. & Fishman, P. S. Enzymatic degradation protects neurons from glutamate excitotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 75, 1045–1052 (2000).

Zhou, Y., Liu, X. & Xu, B. Research progress on the relationship between Parkinson’s disease and REM sleep behavior disorder. JIN 23. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jin2309166 (2024).

Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Zeighami, Y., Dagher, A. & Postuma, R. B. Clinical criteria for subtyping Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers and longitudinal progression. Brain 140, 1959–1976 (2017).

Maggi, G., Vitale, C., Cerciello, F. & Santangelo, G. Sleep and wakefulness disturbances in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis on prevalence and clinical aspects of REM sleep behavior disorder, excessive daytime sleepiness and insomnia. Sleep. Med. Rev. 68, 101759 (2023).

Porges, E. C., Jensen, G., Foster, B., Edden, R. A. & Puts, N. A. The trajectory of cortical GABA across the lifespan, an individual participant data meta-analysis of edited MRS studies. Elife 10. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62575 (2021).

Jung, Y. & St Louis, E. K. Treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 18, 50 (2016).

Brickley, S. G., Franks, N. P. & Wisden, W. Modulation of GABAA receptor function and sleep. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2, 51–57 (2018).

Gunduz-Bruce, H. et al. Trial of SAGE-217 in patients with major depressive disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 903–911 (2019).

Fu, X. et al. Decreased GABA levels of the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex are associated with executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1220122 (2023).

Souza, A. J. et al. An alpha 5-GABA(A) receptor positive allosteric modulator attenuates social and cognitive deficits without changing dopamine system hyperactivity in rats exposed to valproic acid in utero. Autism Res. 17, 1534–1544 (2024).

Alharbi, B. et al. Role of GABA pathway in motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a bidirectional circuit. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29, 205 (2024).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Jankovic, J. et al. Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. Parkinson Study Group. Neurol. 40, 1529–1534 (1990).

Zhao, Y. J. et al. Progression of Parkinson’s disease as evaluated by Hoehn and Yahr stage transition times. Mov. Disord. 25, 710–716 (2010).

Stebbins, G. T. et al. How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale: Comparison with the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov. Disord. 28, 668–670 (2013).

Li, S. X. et al. Validation of a new REM sleep behavior disorder questionnaire (RBDQ-HK). Sleep. Med. 11, 43–48 (2010).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Yin, Z. et al. Contribution of basal ganglia activity to REM sleep disorder in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 95, 947–955 (2024).

Mescher, M., Merkle, H., Kirsch, J., Garwood, M. & Gruetter, R. Simultaneous in vivo spectral editing and water suppression. NMR Biomed. 11, 266–272 (1998).

Chen, Y., Liu, S., Wang, Y., Kang, Y. & Haacke, E. M. STrategically Acquired Gradient Echo (STAGE) imaging, part I: creating enhanced T1 contrast and standardized susceptibility weighted imaging and quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Imaging 46, 130–139 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. STrategically Acquired Gradient Echo (STAGE) imaging, part II: correcting for RF inhomogeneities in estimating T1 and proton density. Magn. Reson. Imaging 46, 140–150 (2018).

Jin, Z. et al. Automatic detection of neuromelanin and iron in the midbrain nuclei using a magnetic resonance imaging-based brain template. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 2011–2025 (2022).

Jiang, J., Haacke, E. M. & Dong, M. Dependence of vessel area accuracy and precision as a function of MR imaging parameters and boundary detection algorithm. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 25, 1226–1234 (2007).

Jokar, M. et al. Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease by combining neuromelanin and iron imaging features using an automated midbrain template approach. NeuroImage 266, 119814 (2023).

Edden, R. A., Puts, N. A., Harris, A. D., Barker, P. B. & Evans, C. J. Gannet: a batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid–edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 40, 1445–1452 (2014).

Near, J. et al. Frequency and phase drift correction of magnetic resonance spectroscopy data by spectral registration in the time domain. Magn. Reson. Med. 73, 44–50 (2015).

Harris, A. D., Puts, N. A. J. & Edden, R. A. E. Tissue correction for GABA-edited MRS: considerations of voxel composition, tissue segmentation, and tissue relaxations. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 42, 1431–1440 (2015).

Gao, F. et al. Edited magnetic resonance spectroscopy detects an age-related decline in brain GABA levels. NeuroImage 78, 75–82 (2013).

Cavassila, S., Deval, S., Huegen, C., van Ormondt, D. & Graveron-Demilly, D. Cramér-Rao bound expressions for parametric estimation of overlapping peaks: influence of prior knowledge. J. Magn. Reson. 143, 311–320 (2000).

Lin, A. et al. Minimum reporting standards for in vivo magnetic resonance Spectroscopy (MRSinMRS): experts’ consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 34, e4484 (2021).

Lowekamp, B. C., Chen, D. T., Ibáñez, L. & Blezek, D. The design of SimpleITK. Front. Neuroinform. 7, 45 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82471949 and 82271954) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (24ZR1446600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z.: data collecting, methodological design, formal analysis, manuscript writing, and figure editing; P.H.: methodological design, neurological examinations and manuscript consulting/advisory; P.L., Y.L., Z.J., and Q.Y.: data collecting and manuscript consulting/advisory; X.S., Y.L., and Z.C.: data analysis and manuscript consulting/advisory; P.W. and J.W.: figure editing and manuscript consulting/advisory; F.L., E.M.H., and Y.C.: manuscript consulting/advisory; S.C.: conceptualization of the study and manuscript consulting/advisory; N.H. and F.Y.: methodology, writing-review and editing, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, project administration. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Huang, P., Liu, P. et al. GABA outperforms iron and neuromelanin in detecting nigrostriatal alterations in early-stage Parkinson’s disease with RBD. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 229 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01096-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01096-8