Abstract

Tremor is a well-recognized sign of Parkinson’s disease (PD), yet its long-term evolution remains unclear, particularly regarding the relationship between resting and action tremor. This retrospective study examined resting and action tremor using specific UPDRS-III subitems in 301 PD patients treated with bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS), assessed preoperatively and at one-year follow-up, with 108 and 57 patients re-evaluated at ten and 15 years, respectively. Most patients (61.8%) had both tremor types, with smaller subsets showing isolated resting (14.3%), action (10.6%), or no tremor (13.3%). Resting tremor responded better to L-Dopa, STN-DBS, and their combination than action tremor (p < 0.05) and remained stable long-term. In contrast, action tremor worsened over time, particularly in tremor-dominant and mixed phenotypes (p < 0.05). A moderate association between tremor types was observed OFF-medication (ρ = 0.59), weakening under treatment (ρ = 0.23/0.30). Action tremor also correlated weakly with bradykinesia and rigidity (ρ = 0.19/0.21). Overall, these differences suggest distinct pathophysiology and neural circuits for resting and action tremor in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tremor is a hallmark clinical sign of Parkinson’s disease (PD), affecting about 75% of patients and representing one of the most distressing symptoms1,2. The classic PD tremor is present at rest, typically oscillating at 4–6 Hz, and affecting the upper limbs3. PD patients may also exhibit action tremor (i.e., postural and/or kinetic tremor), either alone or in combination, which in some cases can have an important functional impact on movements4. Compared to resting tremor, action tremor in PD is characterized by higher frequency oscillations (4–9 Hz) and emerges during voluntary muscle contraction5. Despite these clinical distinctions, there is no clear consensus on the pathophysiological link between resting and action tremor, which are often considered as a single entity in PD6. Hence, it remains uncertain whether resting and action tremor in PD represent strictly interconnected clinical manifestations or rather reflect independent hyperkinetic disorders6.

A more precise clinical interpretation of resting and action tremor would benefit from a detailed investigation and comparison between their short- and long-term response (longitudinal progression) to specific therapeutic interventions, in a large and homogeneous cohort of people with PD. For this purpose, a possible strategy could be to examine how resting and action tremor react to deep-brain stimulation (DBS) therapy in addition to dopaminergic treatment. DBS is a well-established therapeutic approach for managing motor signs and complications in PD, acting on both dopaminergic neurotransmission and dopamine-independent neural networks7,8. DBS is also effective for drug-resistant tremor in PD9. Furthermore, unlike dopaminergic therapy, DBS can modulate neural networks by selectively targeting fiber tracts within the activated therapeutic volume10. Therefore, DBS provides the opportunity to disentangle resting and action tremor by selectively modulating neural circuits in PD.

Previous studies examining the possible link between resting and action tremor have mostly relied on cross-sectional designs involving heterogeneous cohorts of early-moderate PD patients, with or without pharmacological treatment, thus leading to rather inconsistent findings5,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Moreover, none have investigated and compared longitudinal (short- and long-term) changes of resting and action tremor in PD following DBS procedures. This approach could enhance the current pathophysiological understanding of resting and action tremor and possibly guide innovative targeted therapeutic interventions in PD.

In this retrospective, observational study, we aimed to clarify the relationship between resting and action tremor in PD by analyzing them separately in a large cohort of patients treated with subthalamic nucleus DBS (STN-DBS) and clinically followed up to 15 years after surgery. We first investigated therapeutic responses of resting and action tremor to L-Dopa and STN-DBS by assessing patients before and after surgery under different treatment conditions. Then, we examined their short- and long-term progression as well as their association with the other cardinal motor signs of PD, including bradykinesia and rigidity, under optimized treatment conditions (ON-medication at baseline and ON-medication/ON-stimulation post-surgery). Tremor severity was evaluated using composite scores derived from specific UPDRS-III items, both in the overall cohort (PD-ALL) and in subgroups with akinetic-rigid (PD-AR) and tremor-dominant or mixed phenotypes (PD-TREM).

Results

Among the 417 patients with PD who underwent bilateral STN-DBS between 1993 and 2010, 116 were excluded due to loss to follow-up, incomplete medical records, or failure to meet inclusion criteria. The final cohort consisted of 301 patients evaluated at baseline and at one-year, 108 at ten-year, and 57 at 15-year follow-up. Table 1 summarizes the main demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline and follow-up assessments after STN-DBS surgery.

The distribution of tremor subtypes at baseline revealed that most PD patients (186 subjects, 61.8%) exhibited resting and action tremor in combination. A smaller proportion (43 subjects, 14.3%) experienced exclusively resting tremor, while a lower percentage (32 subjects, 10.6%) had only action tremor. The remaining patients (40 subjects, 13.3%) did not display any form of tremor.

Therapeutic responses to L-Dopa and STN-DBS

Resting tremor was more effectively reduced by both dopaminergic therapy (−95.7%) and the combination of dopaminergic therapy with STN-DBS (−94.4%) compared to STN-DBS alone (−74.7%). In contrast, no significant difference was observed between dopaminergic therapy alone and its combination with STN-DBS. Similarly, action tremor showed greater improvement with dopaminergic therapy (−82.3%) and the combination of dopaminergic therapy with STN-DBS (−86.8%) than with STN-DBS alone (−62.7%). Once again, the response of action tremor to dopaminergic therapy was comparable whether administered alone or in combination with STN-DBS (Table 2).

When comparing the treatment response of resting and action tremor, resting tremor exhibited a more favorable response to all therapeutic approaches, including dopaminergic therapy, STN-DBS, and their combination, compared to action tremor (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Bar graphs show the percentage reduction in the composite scores of resting and action tremor following dopaminergic therapy (L-DOPA), subthalamic nucleus deep-brain stimulation (STN-DBS), and their combined treatment (L-DOPA + STN-DBS). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between resting and action tremor improvements within each treatment condition (*p < 0.05).

Short- and long-term progression after STN-DBS

The comparison of resting tremor severity between baseline and follow-up assessments revealed no significant changes in PD-ALL, PD-AR, or PD-TREM (Fig. 2a, d). Differently, while action tremor remained stable one year after surgery, it showed a mild but significant worsening in the long-term, specifically at ten- and 15-year follow-ups, compared to baseline in both PD-ALL and PD-TREM. No significant changes in action tremor severity were observed over time in PD-AR (Table 3; Fig. 2b, e).

a–c Changes in composite scores of resting and action tremor, and their percentage variation in the overall cohort of patients. d–f Same analyses stratified by clinical phenotype: PD-AR (akinetic-rigid) and PD-TREM (tremor-dominant/mixed). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (**p < 0.001, *p < 0.05).

When analyzing the relative progression at specific time points, action tremor worsened significantly at ten- and 15 years compared to resting tremor in PD-ALL and PD-TREM, but not in PD-AR. At one-year follow-up, the percentage change in both resting and action tremor was similar across all subgroups (Table 3; Fig. 2c, f). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the mean absolute values of resting and action tremor indices at baseline and follow-up assessments.

Clinical correlations

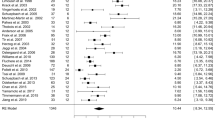

The Spearman correlation analysis revealed a moderate association between resting and action tremor in the OFF-medication condition (ρ = 0.59, p < 0.001), which weakened in the ON-medication (ρ = 0.25, p < 0.001) and in the combined ON-medication and ON-stimulation conditions (ρ = 0.32, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3a–c). Additionally, action tremor showed a weak but significant correlation with both bradykinesia (ρ = 0.185, p < 0.001) and rigidity (ρ = 0.205, p < 0.001), whereas resting tremor did not correlate with the other cardinal motor signs of PD (all p > 0.05) (Fig. 3d, e).

Association of resting and action tremor under different therapeutic conditions (a–c), as well as the relationship between action tremor and bradykinesia (d) and rigidity f). ON medication/ON stimulation data reflect pooled measures from all available postoperative time points (1-, 10-, and 15-year follow-ups).

Discussion

By analyzing a large cohort of PD patients treated with STN-DBS and followed longitudinally for up to 15 years after surgery, this retrospective observational study has shown that resting and action tremor respond differently to therapeutic interventions, follow separate long-term trajectories, and are only partially correlated. These findings challenge the notion that resting and action tremor represent a single entity in PD11,12,13,14,15,18,19 but rather support the alternative hypothesis of partially distinct neural pathways and pathophysiological mechanisms20,21,22.

Our findings demonstrate that resting and action tremor respond differently to L-Dopa and STN-DBS, in line with previous research5,23. Both improved significantly with dopaminergic therapy, either alone or with STN-DBS, confirming the known dopamine sensitivity of tremor in PD, especially at high L-Dopa doses24,25. The strong response observed in our patients may be due to the supramaximal L-Dopa challenge used during clinical assessments.

When directly comparing therapeutic responses, resting tremor showed a more favorable outcome to L-Dopa, STN-DBS, and their combination than action tremor. The marked improvement of resting tremor with L-Dopa likely reflects its effects on dopaminergic pathways in the basal ganglia. Indeed, the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the retro-rubral area and their projections to the STN and globus pallidus are key contributors to resting tremor pathophysiology in PD26,27. Supporting this, neurotoxin-induced primate models of PD may develop resting tremor after damage to these projections28,29. By contrast, action tremor showed only a moderate response to L-Dopa, suggesting a limited role of dopaminergic denervation. Animal models of action tremor, primarily mimicking essential tremor (ET), typically involve damage to the cerebello-thalamo-cortical circuit28. L-Dopa effects on action tremor might result from disinhibition of specific thalamic nuclei (i.e., Vim) secondary to dopaminergic denervation16,30. Accordingly, the lower efficacy of L-Dopa on action tremor may reflect its limited effect on thalamic dopamine receptors, while resting tremor benefits from a dual action on both the basal ganglia and the thalamus. Lastly, another possible explanation is greater involvement of non-dopaminergic systems, such as the serotonergic pathways, in action tremor than resting tremor, though data remain inconsistent16,31. Hence, action tremor may reflect concurrent changes in dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic pathways.

Our study also shows that resting and action tremor in PD respond differently to STN-DBS, with greater improvement in resting tremor, supporting its stronger association with basal ganglia dysfunction. In line with our findings, previous studies have found DBS of STN and globus pallidus pars interna (GPi) equally effective for resting tremor in PD9,32. Moreover, microelectrode recordings have revealed STN neuron synchronization at resting tremor frequency33. By contrast, Vim and dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRTT) are the most effective stimulation targets for action tremor9,32, and patients with intractable action tremor, despite STN- or GPi-DBS, may benefit from a Vim “rescue lead”34.

DBS likely reduces tremor by disrupting neural oscillations within affected networks3,35. The lower efficacy of STN-DBS on action tremor may therefore reflect limited engagement of the DRRT and cerebellothalamic circuit. Indeed, unlike Vim-DBS, it is not possible to induce ataxia through STN-DBS, likely due to reduced access to these pathways36. Furthermore, supporting the crucial role of cerebellar dysfunction in action tremor20,21,22, transcranial magnetic stimulation of the cerebellum selectively resets postural but not resting tremor22, whereas primary motor cortex (M1) stimulation resets both37. These observations highlight the role of electrode location and suggest that contact variability may influence STN-DBS effects on different tremor types.

While resting and action tremor initially followed similar trajectories after STN-DBS, they diverged at ten- and 15-year follow-up. This divergence, along with distinct therapeutic responses, further corroborates the hypothesis that resting and action tremor in PD rely on distinct neuronal networks and pathophysiological mechanisms. The sustained improvement of resting tremor indicates a preferential and more effective interaction of STN stimulation with its underlying circuits. Past evidence has suggested that early DBS in PD might slow resting tremor progression38, potentially triggering networking reorganization through DBS-induced synaptic plasticity39,40. Alternatively, the long-term efficacy on resting tremor may reflect its well-known non-linear and natural progression, often decreasing or disappearing in advanced disease stages41,42. This paradoxical evolution could stem from adaptive changes or the breakdown of a critical oscillatory node due to disease progression41. In contrast, the mild worsening of action tremor over time may reflect progressive entrainment of neurons into oscillatory circuits, exacerbating tremor. Additionally, adaptive responses to chronic STN-DBS may occur, as seen in ET, where Vim-DBS efficacy can decrease over time43,44. This suggests that oscillatory networks can develop habituation/tolerance or reorganize to bypass DBS effects, indicating that tremor circuits remain dynamic and capable of reshaping their activity in response to external modulation45,46.

The analysis of tremor progression across clinical phenotypes pointed out that the divergent trajectories observed in the overall cohort were primarily driven by PD-TREM. This may be due to the low tremor severity in PD-AR, limiting the detection of distinct temporal patterns. Alternatively, neuropathological differences between phenotypes may underlie these findings, driving phenotype-specific tremor progression. In line with this hypothesis, PD subtypes typically follow distinct clinical courses and prognoses47,48. Pathological and neuroimaging studies have revealed shared striatal-thalamo-cortical dysfunction but different patterns of dopaminergic degeneration. Specifically, PD-AR involves the ventrolateral substantia nigra, whereas PD-TREM shows broader degeneration affecting the medial substantia nigra, caudate, and retro-rubral area49,50. Furthermore, PD-TREM typically shows abnormal cerebello-thalamo-cortical activity and increased functional connectivity with the cortico-basal ganglia network51,52. These data emphasize the interplay between basal ganglia and cerebellar circuits in tremor generation, as outlined in the “dimmer-switch model”19,30,53.

Resting and action tremor were more strongly correlated in the OFF-medication and OFF-stimulation conditions but less associated in the ON-medication and ON-stimulation conditions. These findings further support the hypothesis that resting and action tremor partially share neural networks, differently affected by therapies and disease progression. Furthermore, in agreement with previous literature53, we found no association between resting tremor and the other cardinal motor signs of PD, reinforcing its distinct pathophysiology. Again, in line with prior findings11, action tremor showed mild associations with bradykinesia and rigidity. While the link with bradykinesia is intuitive, given the impact of action tremor on voluntary movements54, its connection with rigidity is less clear. Previous authors have reported that PD patients without action tremor exhibit less rigidity55. Additionally, it has been hypothesized that the cogwheel phenomenon in rigidity may reflect subclinical tremor56. However, evidence remains limited, and the still incomplete understanding of rigidity pathophysiology further complicates the interpretation of its relationship with action tremor in PD.

A final comment concerns tremor subtype distribution, which confirmed that resting tremor is the most frequent tremor type (76.1%), either alone or with action tremor, consistent with its role as a cardinal motor sign of PD. Similarly, action tremor was observed in 72.4% of patients, underscoring its frequent coexistence with resting tremor11,12,16,17. Moreover, 10.6% of patients had isolated action tremor, typically observed in ET, supporting a possible link between these two disorders57. Our findings align with previous prevalence data on tremor classification in PD58. As in our cohort, this classification is based on the isolated or combined presence of resting and action tremor, and additionally considers their respective oscillation frequencies58. Notably, our patients with only action tremor had no prior ET diagnosis, emphasizing that action tremor can be intrinsic to PD. Given the clinical overlap, the possibility that action tremor in PD arises from the later development of ET cannot be excluded. However, current evidence supports the conversion from ET to PD, but not vice versa59. It remains unclear whether this represents a unidirectional disease conversion or a shared underlying pathology that predisposes individuals to both conditions59,60. In line with this observation, Lewy body pathology has been found in the noradrenergic locus coeruleus in 15–24% of ET patients61. This structure, which is connected to the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum, is also significantly impaired in PD62. Disrupted noradrenergic projections may impair the Purkinje cells' inhibitory output, contributing to tremor63. Overall, the distribution of tremor subtypes highlights the need for more focus on understanding action tremor as a distinct PD feature.

Our study has some limitations. First, the lack of a control group prevents determining whether the long-term suppression of resting tremor reflects its natural decline with disease progression. However, if resting tremor naturally decreases over time while action tremor persists or worsens, this would further support their divergent trajectories. Second, all patients were evaluated under optimized treatment conditions, limiting the ability to disentangle pharmacological, surgical, and disease-related effects. However, OFF-stimulation assessments were impractical due to poor tolerability, uncertain washout duration, and the risk of severe STN-DBS withdrawal syndrome. The masking effect of therapy in the postoperative period also precluded reliable reassessment of clinical phenotypes. Nonetheless, the consistent tremor progression across baseline phenotypes supports the validity of the initial classification. Third, the UPDRS and the MDS-UPDRS do not distinguish the re-emergent component of postural tremor. However, given the similarities to resting tremor5,64, any influence on action tremor analysis was likely minimal. Lastly, our cohort of patients included highly selected DBS-eligible subjects, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, this study reveals distinct therapeutic responses, different trajectories, and limited reciprocal association between resting and action tremor in PD, supporting partially separate pathophysiological mechanisms. Based on our findings and previous data, resting and action tremor likely arise from distinct but interconnected oscillators within a spatially distributed tremor network26. Central oscillators for resting tremor may reside in the basal ganglia, while those for action tremor reside in the cerebellar network. These oscillators modulate a common final pathway within the cerebello-thalamo-cortical circuit, with both thalamus and M1 serving as critical convergence points45. Future research should focus on integrating neurophysiological approaches that target specific brain regions with advanced structural and functional neuroimaging techniques to elucidate the role of key nuclei and pathways in the pathophysiology of resting and action tremor in PD.

Methods

Study design and ethical considerations

This retrospective cohort study was conducted following the STROBE guidelines (Supplementary Material 1). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional research board of Grenoble Alpes University Hospital, ensuring compliance with ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion.

Patient selection and eligibility criteria

The study included PD patients who underwent bilateral STN-DBS at the Grenoble Alpes University Hospital (France). Eligibility for surgery was determined based on the UK Brain Bank criteria for idiopathic PD, the presence of motor complications such as fluctuations or levodopa-induced dyskinesia despite optimized pharmacological treatment, age below 75 years, the absence of dementia, major psychiatric disorders, or relevant structural abnormalities on brain MRI. Patients with a history of neurosurgical brain procedures, DBS targeting sites other than STN, surgical complications, implantation of more than two electrodes, or lead misplacement were excluded.

Clinical assessments

All participants underwent a thorough neuropsychiatric evaluation at baseline (before surgery), along with an L-Dopa challenge. Baseline and follow-up assessments at one, ten, and 15 years after surgery were performed using standardized scales including: the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) up to 2011, and the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision (MDS-UPDRS) thereafter; the Hoehn and Yahr scale (H&Y); the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (MDRS); and the Frontal Score (a composite measure totaling up to 50 points, derived from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the Verbal Fluency Test, and the Graphic and Motor Series). To ensure consistency, the MDS-UPDRS-III scores were converted to the UPDRS-III using standardized formulas65. This conversion was applied exclusively for descriptive purposes, as only individual items with direct correspondence across the two scales were used for all analyses. Moreover, the clinical phenotype of each patient was classified prior to surgery in the OFF-medication condition, using previously-reported methods66. Baseline assessments were performed in both the OFF- (i.e., ≥12-h withdrawal of dopaminergic medication) and ON-medication conditions (i.e., one hour after administration of a suprathreshold dose of L-Dopa), while post-surgery evaluations were conducted under optimized therapeutic conditions (i.e., ON-medication and ON-stimulation).

Data collection and statistical analysis

Data were collected at baseline, and at one, ten, and 15 years following STN-DBS surgery. Information was extracted from medical records and stored in a customized database for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the distribution of patients with resting and action tremor, whether isolated or combined, and those without tremor at baseline under the OFF-medication condition. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data distribution, and given the non-normality of the data, non-parametric methods were applied throughout.

The primary outcome was the assessment of resting and action tremor response to various therapeutic approaches (L-Dopa, STN-DBS, L-Dopa + STN-DBS) in the short-term follow-up. To this aim, patients were assessed at baseline and at one-year follow-up under different therapeutic conditions (OFF- and ON-medication at baseline; OFF-medication/OFF-stimulation, OFF-medication/ON-stimulation, ON-medication/OFF-stimulation, and ON-medication/ON-stimulation after surgery). The Skillings–Mack and Wilcoxon tests were first applied to analyze the tremor response to each treatment (L-Dopa vs STN-DBS, L-Dopa vs STN-DBS + L-Dopa, and STN-DBS vs STN-DBS + L-Dopa). Then, the Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests were also used to compare whether the response to these therapies differed between resting and action tremor.

The secondary outcome focused on the longitudinal assessment of resting and action tremor in PD-ALL (entire cohort of PD patients) and in subgroups based on baseline clinical phenotypes (patients with an akinetic-rigid phenotype – PD-AR, and those with a tremor or mixed phenotype – PD-TREM). This was evaluated at baseline, one year, ten years, and 15 years after surgery, under optimal treatment conditions (i.e., ON-medication and ON-medication/ON-stimulation, before and after surgery, respectively). The severity of resting and action tremor was assessed at baseline and each follow-up visit using specific composite scores, calculated from individual items that are equivalent and directly comparable across the UPDRS and MDS-UPDRS scales. Specifically, these scores were derived from the sum of the following UPDRS/MDS-UPDRS part III items: item 20/3.17 (assessed at the head, upper, and lower extremities) for resting tremor (range 0–20); item 21/3.15–3.16 (including both postural and kinetic tremor at the upper extremities) for action tremor (range 0–8). For patients assessed with the MDS-UPDRS after 2011, the highest score between the two action tremor items (3.15 and 3.16) was used to maintain consistency with the UPDRS system, where item 21 evaluates both postural and kinetic tremor together. The Skillings–Mack test and the Wilcoxon test were used to compare composite scores of resting and action tremor over time (i.e., at baseline, one year, ten years, and 15 years after surgery). Moreover, given the different absolute value ranges, the percentage change from baseline in resting tremor was compared with that of action tremor at each time point using the Mann–Whitney test.

Finally, the Spearman’s rank correlation test was applied to explore clinical correlations, focusing on the reciprocal relationship between resting and action tremor, as well as their association with other cardinal motor signs in PD, including bradykinesia and rigidity. To assess bradykinesia and rigidity, two composite scores were calculated by summing the corresponding items from the UPDRS-III/MDS-UPDRS-III: item 22/3.3 for rigidity (neck and extremities, range 0–20), and items 23/3.4, 24/3.5, 26/3.8, and 31/3.14 for bradykinesia (range 0–28).

Missing data were handled by using a pairwise deletion method. For all statistical tests, the significance level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). To control the false discovery rate and minimize the risk of Type I errors, the Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied only in analyses where the initial statistical test indicated significance and multiple comparisons were performed. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied to the full set of p-values in each analysis involving multiple comparisons when the initial statistical test yielded a significant result. Specifically, the number of comparisons included in the correction was three for analyses comparing treatment conditions (L-Dopa, STN-DBS, and STN-DBS + L-Dopa), and six for those comparing measures at different time points (baseline, one year, ten years, and 15 years). All p-values reported as significant in the manuscript are adjusted values.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS package (IBM-SPSS Inc., USA).

Data availability

The dataset used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to sensitive data will be restricted to preserve privacy.

References

Gigante, A. F. et al. Rest tremor in Parkinson’s disease: body distribution and time of appearance. J. Neurol. Sci. 375, 215–219 (2017).

Heusinkveld, L. E., Hacker, M. L., Turchan, M., Davis, T. L. & Charles, D. Impact of tremor on patients with early stage Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 9, 628 (2018).

Abusrair, A. H., Elsekaily, W. & Bohlega, S. Tremor in Parkinson’s disease: from pathophysiology to advanced therapies. Tremor Hyperkinet. Mov.12, 29 (2022).

Louis, E. D. & Machado, D. G. Tremor-related quality of life: a comparison of essential tremor vs. Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 729–735 (2015).

Dirkx, M. F., Zach, H., Bloem, B. R., Hallett, M. & Helmich, R. C. The nature of postural tremor in Parkinson disease. Neurology 90, e1095–e1103 (2018).

Hallett, M. & Deuschl, G. Are we making progress in the understanding of tremor in Parkinson’s disease?. Ann. Neurol. 68, 780 (2010).

Hollunder, B. et al. Mapping dysfunctional circuits in the frontal cortex using deep brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 573–586 (2024).

Neudorfer, C. et al. Lead-DBS v3.0: mapping deep brain stimulation effects to local anatomy and global networks. NeuroImage 268, 119862 (2023).

Wong, J. K. et al. STN versus GPi deep brain stimulation for action and rest tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 578615 (2020).

Neumann, W.-J., Horn, A. & Kühn, A. A. Insights and opportunities for deep brain stimulation as a brain circuit intervention. Trends Neurosci. 46, 472–487 (2023).

Gigante, A. F. et al. Action tremor in Parkinson’s disease: frequency and relationship to motor and non-motor signs. Eur. J. Neurol. 22, 223–228 (2015).

Gupta, D. K., Marano, M., Zweber, C., Boyd, J. T. & Kuo, S.-H. Prevalence and relationship of rest tremor and action tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Tremor Hyperkinet. Mov. 10, 58 (2020).

Louis, E. D. et al. Clinical correlates of action tremor in Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 58, 1630–1634 (2001).

Rana, A. Q. et al. Is action tremor in Parkinson’s disease related to resting tremor?. Neurol. Res. 36, 107–111 (2014).

Rana, A. Q. & Saleh, M. Relationship between resting and action tremors in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 7, 232–237 (2016).

Pasquini, J. et al. Progression of tremor in early stages of Parkinson’s disease: a clinical and neuroimaging study. Brain 141, 811–821 (2018).

Gupta, D. & Kuo, S.-H. Prevalence and patterns of rest, postural and action tremor in drug-naïve Parkinson’s disease (P2.066). Neurology 90, P2.066 (2018).

Duval, C. Rest and postural tremors in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 70, 44–48 (2006).

Helmich, R. C., Janssen, M. J. R., Oyen, W. J. G., Bloem, B. R. & Toni, I. Pallidal dysfunction drives a cerebellothalamic circuit into Parkinson tremor. Ann. Neurol. 69, 269–281 (2011).

Abdulbaki, A., Kaufmann, J., Galazky, I., Buentjen, L. & Voges, J. Neuromodulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease: the effect of fiber tract stimulation on tremor control. Acta Neurochir.163, 185–195 (2021).

Duanmu, X. et al. Aberrant dentato-rubro-thalamic pathway in action tremor but not rest tremor: a multi-modality magnetic resonance imaging study. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 4160–4171 (2023).

Ni, Z., Pinto, A. D., Lang, A. E. & Chen, R. Involvement of the cerebellothalamocortical pathway in Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 68, 816–824 (2010).

Raethjen, J. et al. Parkinsonian action tremor: interference with object manipulation and lacking levodopa response. Exp. Neurol. 194, 151–160 (2005).

Wirth, T. et al. Parkinson’s disease tremor differentially responds to levodopa and subthalamic stimulation. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 10, 1639–1649 (2023).

Zach, H. et al. Dopamine-responsive and dopamine-resistant resting tremor in Parkinson disease. Neurology 95, e1461–e1470 (2020).

Helmich, R. C. The cerebral basis of Parkinsonian tremor: a network perspective. Mov. Disord. 33, 219–231 (2018).

Jellinger, K. A. Neuropathology of sporadic Parkinson’s disease: evaluation and changes of concepts. Mov. Disord. 27, 8–30 (2012).

Pan, M.-K., Ni, C.-L., Wu, Y.-C., Li, Y.-S. & Kuo, S.-H. Animal models of tremor: relevance to human tremor disorders. Tremor Hyperkinet. Mov. 8, 587 (2018).

Porras, G., Li, Q. & Bezard, E. Modeling Parkinson’s disease in primates: the MPTP model. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a009308 (2012).

Dirkx, M. F. et al. Dopamine controls Parkinson’s tremor by inhibiting the cerebellar thalamus. Brain J. Neurol. 140, 721–734 (2017).

Loane, C. et al. Serotonergic loss in motor circuitries correlates with severity of action-postural tremor in PD. Neurology 80, 1850–1855 (2013).

Chandra, V., Hilliard, J. D. & Foote, K. D. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of tremor. J. Neurol. Sci. 435, 120190 (2022).

Amtage, F. et al. High functional connectivity of tremor related subthalamic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol.120, 1755–1761 (2009).

Azghadi, A., Rajagopal, M. M., Atkinson, K. A. & Holloway, K. L. Utility of GPI+VIM dual-lead deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease patients with significant residual tremor on medication. J. Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.3171/2021.4.JNS21502 (2021).

Chiken, S. & Nambu, A. Mechanism of deep brain stimulation: inhibition, excitation, or disruption?. Neuroscientist 22, 313–322 (2016).

Deuter, D. et al. Amelioration of Parkinsonian tremor evoked by DBS: which role play cerebello-(sub)thalamic fiber tracts?. J. Neurol. 271, 1451–1461 (2024).

Lu, M.-K. et al. Resetting tremor by single and paired transcranial magnetic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor. Clin. Neurophysiol.126, 2330–2336 (2015).

Hacker, M. L. et al. Effects of deep brain stimulation on rest tremor progression in early stage Parkinson disease. Neurology 91, e463–e471 (2018).

Kuo, S.-H. et al. Deep brain stimulation and climbing fiber synaptic pathology in essential tremor. Ann. Neurol. 80, 461–465 (2016).

Paek, S. B. et al. Frequency-dependent functional neuromodulatory effects on the motor network by ventral lateral thalamic deep brain stimulation in swine. Neuroimage 105, 181–188 (2015).

Garcia Ruiz, P. J., Ruiz Lopez, M. & Feliz, C. E. On the reversibility of parkinsonian tremor. Brief review and hypothesis. Neurologia 37, 74–76 (2022).

Toth, C., Rajput, M. & Rajput, A. H. Anomalies of asymmetry of clinical signs in parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 19, 151–157 (2004).

Bai, Y. et al. Loss of long-term benefit from VIM-DBS in essential tremor: a secondary analysis of repeated measurements. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 28, 279–288 (2022).

Lu, G. et al. Outcomes and adverse effects of deep brain stimulation on the ventral intermediate nucleus in patients with essential tremor. Neural Plast. 2020, 2486065 (2020).

Fasano, A. & Helmich, R. C. Tremor habituation to deep brain stimulation: underlying mechanisms and solutions. Mov. Disord. 34, 1761–1773 (2019).

Tiefenbach, J. et al. Loss of efficacy in ventral intermediate nucleus stimulation for essential tremor. World Neurosurg. 185, e1177–e1181 (2024).

Rajput, A. H., Voll, A., Rajput, M. L., Robinson, C. A. & Rajput, A. Course in Parkinson disease subtypes. Neurology 73, 206–212 (2009).

Kipfer, S., Stephan, M. A., Schüpbach, W. M. M., Ballinari, P. & Kaelin-Lang, A. Resting tremor in Parkinson disease: a negative predictor of levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Arch. Neurol. 68, 1037–1039 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Akinetic-rigid and tremor-dominant Parkinson’s disease patients show different patterns of intrinsic brain activity. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 23–30 (2015).

Eggers, C., Kahraman, D., Fink, G. R., Schmidt, M. & Timmermann, L. Akinetic-rigid and tremor-dominant Parkinson’s disease patients show different patterns of FP-CIT single photon emission computed tomography. Mov. Disord. 26, 416–423 (2011).

Muthuraman, M. et al. Cerebello-cortical network fingerprints differ between essential, Parkinson’s and mimicked tremors. Brain 141, 1770–1781 (2018).

Prasad, S., Saini, J., Bharath, R. D. & Pal, P. K. Differential patterns of functional connectivity in tremor dominant Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor plus. J. Neural Transm. 131, 781–789 (2024).

Helmich, R. C., Hallett, M., Deuschl, G., Toni, I. & Bloem, B. R. Cerebral causes and consequences of Parkinsonian resting tremor: a tale of two circuits?. Brain 135, 3206–3226 (2012).

Forssberg, H., Ingvarsson, P. E., Iwasaki, N., Johansson, R. S. & Gordon, A. M. Action tremor during object manipulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.15, 244–254 (2000).

Milanov, I. Clinical and electromyographic examinations of Parkinsonian tremor. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 6, 229–235 (2000).

Findley, L. J., Gresty, M. A. & Halmagyi, G. M. Tremor, the cogwheel phenomenon and clonus in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 44, 534–546 (1981).

Tarakad, A. & Jankovic, J. Essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease: exploring the relationship. Tremer Hyperkinet. Mov. 8, 589 (2018).

Gironell, A. et al. Tremor types in Parkinson disease: a descriptive study using a new classification. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 4327597 (2018).

Louis, E. D. & Ottman, R. Is there a one-way street from essential tremor to Parkinson’s disease? Possible biological ramifications. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 1440–1444 (2013).

Yoo, S.-W. et al. Exploring the link between essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease. Npj Park. Dis. 9, 1–8 (2023).

Mavroudis, I. & Petridis, F. Neuropathological findings in essential tremor. Folia Neuropathol. https://doi.org/10.5114/fn.2024.140569 (2024).

Bari, B. A., Chokshi, V. & Schmidt, K. Locus coeruleus-norepinephrine: basic functions and insights into Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 15, 1006–1013 (2020).

Louis, E. D. et al. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain J. Neurol. 130, 3297–3307 (2007).

Swinnen, B. E. K. S., de Bie, R. M. A., Hallett, M., Helmich, R. C. & Buijink, A. W. G. Reconstructing re-emergent tremor. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 10, 1293–1296 (2023).

Goetz, C. G., Stebbins, G. T. & Tilley, B. C. Calibration of unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores to Movement Disorder Society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores. Mov. Disord. 27, 1239–1242 (2012).

Kang, G. A. et al. Clinical characteristics in early Parkinson’s disease in a central California population-based study. Mov. Disord.20, 1133–1142 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to Pierre Pollak, Patricia Limousin, Claire Ardouin, Paul Krack, and Alim Louis Benabid for their outstanding contribution to the medical care of the participants in this study. This study did not receive external funding. A.Z.’s research activity was supported by the European funding “PNRR-MR1-2022-12376921, Next Generation EU (PNRR M6C2) Investment 2.1 Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research of the NHS”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z., A.S., and E.M. contributed to the conception and design, and data analysis of the study; A.Z., M.P., F.C., F.B., A.C., S.M., P.P., E.S., S.C., and V.F. contributed to the data acquisition; A.Z., A.S., and E.M. contributed to drafting the text or preparing the figures. S.M., P.P., E.S., S.C., and V.F. contributed to the critical review of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to the present study. E.M. has received honoraria for consulting services from Medtronic and Abbott, as well as grant support from France Parkinson. A.C. has received research grants from Medtronic. V.F. has received honoraria from AbbVie and Medtronic for consulting services and lecturing. E.M. is an editor for npj Parkinson’s Disease. E.M. was not involved in the journal’s review of, or decisions related to, this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zampogna, A., Suppa, A., Patera, M. et al. Resting and action tremor in Parkinson’s disease: pathophysiological insights from long-term STN-DBS. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01130-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01130-9