Abstract

Impulse control disorders (ICD) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients mainly occur as adverse effects of dopamine replacement therapy. Despite several known risk factors, ICD development cannot yet be accurately predicted at PD diagnosis. We aimed to investigate the predictability of incident ICD by baseline measures of demographic, clinical, dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography and single nucleotide polymorphisms data of medication-free PD patients, obtained from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI; n = 311) and Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC; n = 72) longitudinal datasets. We trained machine learning models to predict incident ICD at any follow-up assessment. The highest predictive performance (AUC = 0.66) was achieved by clinical features only. We observed significantly higher performance (AUC = 0.74) when classifying patients who developed ICD within four years from diagnosis compared with those tested negative for seven or more years. Overall, prediction accuracy for later ICD development at the time of PD diagnosis is limited, but increases for shorter time-to-event predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Impulse control disorders (ICD) affect about 15–30% of the Parkinson’s disease (PD) population1. Examples of ICD include hypersexuality, pathological gambling, binge eating and compulsive shopping, and are regarded as adverse effect of dopamine replacement therapy (DRT)1. Besides DRT, various demographic (e.g., male sex, younger age of PD onset, education level), clinical (e.g., depression, sleep disorders, personal and/or family history of behavioral addictions), and genetic risk factors2 have been associated with ICD development. So far, none of these factors are used clinically because of insufficient predictive ability beyond group-level comparisons.

Recent studies have used machine learning (ML) to predict ICD incidence at individual level3,4,5,6. The best performing models achieved 75–85% accuracy in predicting a positive ICD screen between annual patient visits. Reported predictors across studies varied, but included demographics, disease duration, past presence of ICD, depression, antidepressant use and DRT. Additionally, two studies reported significantly higher performance when adding genetic data3,7, while two other studies did not5,6. These studies present promising evidence regarding the potential of ICD risk prediction throughout the disease trajectory. However, from a clinical perspective it is essential to predict ICD development before the initiation of DRT. This would allow personalized assessment of the premorbid vulnerability for ICD, and hence would enable clinicians to weigh the risk in deciding on DRT prescription to reduce the risk of ICD development.

ICD is associated with dysregulation of dopamine levels in the striatum. Previous imaging studies using dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography (DAT-SPECT), have consistently shown lower striatal DAT binding in individuals with PD and co-morbid ICD than those without ICD8,9,10. However, it still remains unclear whether the observed differences are due to pre-existing neural characteristics, effects of prolonged DRT or alterations associated with ICD development1. Nevertheless, significantly lower striatal DAT availability, measured by specific binding ratios (SBRs), was observed to precede ICD development in a small clinical sample11. Adequately powered longitudinal studies in drug-naïve patients are needed to understand whether these changes may represent biomarkers of premorbid vulnerability to ICD9.

Here, we aimed to develop ML models to predict future ICD development using clinical, DAT-SPECT, and genetic variables obtained from PD patients before the start of dopaminergic medication. We hypothesized that DAT-SPECT has added value to clinical variables in predicting ICD development. This information could be useful during the clinical management of PD.

Results

Participants

The final sample consisted of 378 patients (PPMI n = 311, Amsterdam UMC n = 67; Fig. 1). Disease severity at baseline was higher in the Amsterdam UMC sample for both motor and non-motor symptoms, and the follow-up duration was higher in the PPMI sample. The prevalence of ICD at any follow-up was 32.0% (PPMI: 32.5%, Amsterdam UMC: 29.9%) (Table 1).

Univariate group analyses

The ICD group had a lower age at onset and a higher proportion of severe apathy symptoms at baseline, compared with the No ICD group (see Table 2 and supplemental Table S2). The ICD group showed a lower LEDD score at follow-up, with a lower levodopa dosage but a significantly higher dopamine agonist dosage. The lower age at onset and lower LEDD at follow-up were specific to the PPMI sample when inspecting the Cohort*Group interaction (see supplemental Table S3). Moreover, in the Amsterdam UMC cohort the ICD group showed higher MDS-UPDRS part III scores, lower MMSE score, and higher depressive, anxiety and apathy symptom severity. There were no significant differences between the No ICD and ICD group on specific binding ratio’s, radiomic texture features and genetic features after controlling for FDR (supplemental Tables S4–S6).

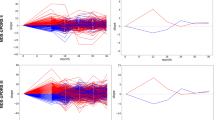

Pre-registered ML analyses

Cross-validated classification metrics of the different models on the combined dataset (PPMI+ Amsterdam UMC) are presented in Table 3. For the models including only clinical variables, the RF, LR and MLP models were significant against chance (AUC = 0.66 ± 0.05, p < 0.05), while GB did not (AUC = 0.57 ± 0.06, p = 0.86). The most important predictors of ICD were (higher) anxiety and (lower) age of onset, with MDA = 0.07 ± 0.05 and MDA = 0.04 ± 0.04, respectively (Fig. 2). Standalone radiomic and latent features models were not significantly better than chance (AUC ~ 0.50 ± 0.06, p > 0.05). Clinical features model performance dropped considerably when adding DAT-SPECT features (RF model with radiomic features: AUC = 0.60 ± 0.06, LR and MLP classifiers with latent features: AUC = 0.63 ± 0.06). Anxiety, age of onset and three radiomic features showed equally high permutation importance (MAD = 0.03 ± 0.04) (Fig. 2). All models trained on the PPMI dataset and tested on the Amsterdam UMC dataset were not significantly better than chance (p > 0.05; Supplementary Table S7).

Results of the models with additional inclusion of SNPs from the PPMI cohort are shown in Table 4. Highest performance was achieved by the RF classifier, however no significant improvement was observed with the addition of genetic data (AUC = 0.69 ± 0.06) to the Clinical (AUC = 0.68 ± 0.06) or Clinical+Radiomics (AUC = 0.69 ± 0.06) models. The highest feature importance was observed for anxiety (MDA = 0.08 ± 0.05) and age of onset (MDA = 0.06 ± 0.05). Two radiomic features presented positive MDA = 0.01 ± 0.04, while for the other selected features and the genetic variants MDA was zero or negative (Fig. 2). Standalone genetic feature models were not significantly better than chance (AUC ~ 0.50 ± 0.08, p > 0.05).

Performance of predicting positive screens for specific ICDs vs No-ICD with models trained on clinical features were as follows: gambling - AUC = 0.57 ± 0.17 (p = 0.985); hypersexuality - AUC = 0.74 ± 0.06 (p = 0.001); compulsive buying - AUC = 0.62 ± 0.09 (p = 0.005); binge eating - AUC = 0.67 ± 0.09 (p = 0.004). No improvement was observed with the addition of radiomic features. Notably, sex was the most important predictor of hypersexuality (MDA = 0.12 ± 0.04). Anxiety (MDA = 0.8 ± 0.07), followed by age of onset (MDA = 0.6 ± 0.05), were important predictors for the other ICDs, while PD stage presented some importance in binge eating prediction (MDA = 0.3 ± 0.05).

Post-hoc ML analyses

As the prediction of an event further into the future may be more difficult, we performed a post-hoc analysis including ICD positive patients that had developed ICD within 4 years after baseline, while those that developed ICD after 4 years were removed from the analyses. We considered the year 4 to be a reasonable cut-off, that has been widely used in previous studies12,13. We contrasted this subgroup with individuals that did not show any positive screen for 7 or more years after baseline. The year 7 cut-off was selected to include an ICD negative subgroup of comparable size to the ICD-positive subgroup, while also maintaining a consistent screening-negative status across multiple follow-ups. No alternative follow-up durations were tested. All models achieved significantly higher performances (p < 0.05) compared to the pre-registered analysis, up to AUC = 0.74 ± 0.05 (Table S11-S12).

Since DRT is considered the primary risk factor of ICD development, we additionally included medication received at the time of ICD positive screening as predictor (LEDD at follow-up, as well as usage of levodopa, dopamine agonists, MAO-B and COMT inhibitors (yes or no)). All models achieved significantly higher performances compared to the models of the pre-registered analysis (p < 0.05), up to AUC = 0.71 ± 0.06, with LEDD at follow-up being important (MDA = 0.02 ± 0.04), along with age at onset (MDA = 0.04 ± 0.04) and anxiety (MDA = 0.03 ± 0.04; Table S13).

Lastly, we evaluated ML models to classify PD vs Healthy Controls to confirm the quality of the extracted radiomic and latent features. We used the imaging data of the 378 PD samples of the pre-registered analysis and the 180 HCs of the PPMI. The models achieved excellent performance of AUC = 0.99 ± 0.02 (Table S14).

Discussion

In this study we sought to investigate the ability of ML models, trained on clinical, DAT-SPECT and genetic data obtained at the time of PD diagnosis, to predict the future development of ICDs after starting DRT. We observed a moderate performance of the preregistered models using baseline clinical variables in predicting ICD positive screen at any time follow-up assessment (AUC = 0.66 ± 0.05). The most important predictors were the severity of anxiety and age of PD onset. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no improvement in the predictive performance of the models when either DAT-SPECT features or SNPs were added. In an effort to increase the relevance of our results we performed two post-hoc analyses. First, we used a modified sample including patients who developed ICD within 4 years from diagnosis and those who tested negative for seven or more years, which boosted the performance up to AUC = 0.74 ± 0.05. Additionally, we tested adding dopaminergic medication use at the time of ICD development as predictor variable, which also significantly increased the performance up to AUC = 0.71 ± 0.06.

The most important contribution of our study to the existing knowledge is the evaluation of molecular neuroimaging in the prediction of future ICD development, at the time of PD diagnosis and before DRT initiation. Previous DAT-SPECT studies have identified significantly lower striatal DAT binding in PD patients with ICD at the group level8,9,10,11. However, whether this reduction is a consequence of either DRT or ICD, or predates ICD development, and thus could be used as a predictive biomarker on the individual level, remained unclear. Here, we extracted radiomic features that were previously shown to be more sensitively associated with future PD outcomes, compared to the conventional SBRs12,14, but these did not improve the performance of the ML model, showing negligible predictive ability of DAT-SPECT at the individual level. The same trend was also observed with the models including latent features derived from the autoencoder. We did however, observe excellent classification accuracy (AUC = 0.99 ± 0.02) when trying to classify PD versus healthy controls, meaning that the extracted features contain relevant information about the PD pathophysiology. While the previous findings provided important early indications of a potential premorbid dopaminergic vulnerability11, our substantially larger and more heterogeneous cohort did not show significant baseline striatal DAT differences between future ICD+ and ICD– patients. This discrepancy may reflect methodological differences across studies as well as the wider uncertainty inherent in smaller samples, suggesting that any premorbid DAT effect is likely subtle. Moreover, other imaging studies linking reduced striatal DAT binding to ICDs have included all available imaging scans from the follow-up assessments8,10, raising the possibility that dynamic dopaminergic changes over time may still play a meaningful role in predicting ICD development. However, such longitudinal ML modelling was beyond the scope of our study.

Recent studies have highlighted the promise of ML to predict ICD incidence at the individual level3,4,5,6, albeit showcasing a great variability in the methodology used (PD sample, predictor and target variables, validation setting) and, consequently, with model performances ranging between AUCs = 0.65–0.85. In our study we observed a classification performance AUC = 0.66 for the clinical features subset, that lies within the lower boundary of the previously reported performances. However, there are major methodological differences between this and the previous studies. First, previous studies used data from all available assessments up to the point of ICD development for their models. In contrast, we aimed at assessing the predictive performance of data obtained around the time of PD diagnosis, and this might have reduced the predictive effect, especially when the time interval to ICD development is greater. Only Faouzi et al.5 have reported a baseline model with AUC = 0.75. However, this model had presence of ICD at baseline as the most important predictor, while we excluded PD cases with a positive ICD screen at baseline from the analyses, as these are likely false positives as no DRT had commenced. Second, previous studies have also used DRT as predictor, which turned out to be the most significant predictor, in line with a wealth of previous evidence that have directly linked ICD incidence to DRT1,15. Indeed, we were able to replicate these findings when adding DRT use at the time of ICD development as predictor. However, we do not consider these models useful in terms of their clinical applicability, since they would rely on the knowledge of future data beforehand.

In our study, we did not observe any contribution from the genetic data to the models. Previous studies have provided mixed results regarding the predictive value of SNPs for ICD development. Erga et al.7 and Jesus et al.16 reported significant improvements when adding genetic features to their ML models, trained on the Norwegian ParkWest study sample and a Spanish dataset, respectively. Kraemmer and colleagues3 reported an AUC of 0.65 with clinical variables only, and an AUC of 0.76 with clinical features and 13 SNPs, denoting a significant improvement in ICD prediction, in the PPMI dataset. In contrast, Faouzi et al.5 who examined 50 SNPs previously proposed as risk factors of ICD, did not observe a significant improvement in the predictive performance of their models in the PPMI dataset. Redenŝek et al.6 also reported a negative result on a local Slovenian PD sample. While these contradictory results may stem from the poor generalizability of models trained and evaluated on small datasets, they could also highlight broader limitations of candidate-gene approaches, which have demonstrated low reproducibility and are increasingly being replaced by genome-wide and polygenic methods. Indeed, the follow-up GWAS by Weintraub et al.4 including PPMI, 23&Me, and local UPenn datasets did not replicate the SNPs reported in the earlier candidate-gene study3, highlighting the challenges and instability of hypothesis-driven SNP selection for ICD prediction. Interestingly, the clinical-genetic model proposed by Weintraub et al.4 demonstrated relatively high classification performance in ICD prediction (AUC = 0.72), however the two SNPs included in their model were not significant predictors of ICD. Additional work using polygenic risk scores17,18 reported negative results regarding their contribution in ICD prediction. Consistent with the more robust evidence, our study suggests that the specific candidate variants examined here do not enhance prediction when added to the clinical features in our dataset.

This is the first study that combined multiparametric data obtained around the time of PD diagnosis to predict ICD development before initiation of DRT. In most ML models, anxiety severity was the most important predictor, supporting prior findings that higher anxiety levels precede ICD development16,19. Neuropsychiatric symptom severity is also reported to be associated with future cognitive and motor decline20,21. These results highlight the need for neuropsychiatric screening at PD diagnosis to identify patients at ICD risk. However, our study shows that presence of anxiety—whether or not combined with other clinical, DAT-SPECT or genetic information—is not sufficient to predict ICD development at the individual level. Thus, our results do not justify altering dopaminergic treatment for patients presenting with these characteristics. As observed in this and previous studies5, higher accuracy could be achieved when predicting closer to ICD onset. This indicates that psychoeducation and frequent monitoring is essential both at the time of dopaminergic treatment initiation and in the period after. Overall, our study reveals the limitations of using baseline data alone to predict ICDs, reaffirming the role of DRT as the major risk factor of ICD. This establishes an important practical boundary as baseline data models do not seem sufficient to guide dopaminergic treatment decisions. More generally, any model intended to inform prescribing would require prospective validation, as altering treatment based on predicted risk introduces a distribution shift relative to the data on which the model was trained. Therefore, before any predictive model could be used to modify clinical management, its utility would need to be tested in a biomarker-stratified or model-informed clinical trial.

Recent reports demonstrated significant differences between ICD positive and negative PD patients in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures, such as decreased functional connectivity within and between dopaminergic neuronal circuitries, periventricular white matter hyperintensities and widespread white matter tract damage, and aberrant brain topological organization22,23,24. Such measures might be of interest to include in future prediction studies.

ML modelling needs adequate sample sizes to achieve good predictive performance, thus our results might have been influenced by the relatively low sample size. Although the inclusion of different datasets is vital for evaluating the models generalization capabilities, this has increased the heterogeneity in two main ways. First, the heterogeneity due to the variability in the assessments/examinations scales used between sites. To address this, we harmonized clinical rating scales and applied normalization to the voxel intensities of the DAT-SPECT images to reduce scale-related inconsistencies. Second, the heterogeneity in the clinical status of PD, which is a chronic disease with variable progression pathways, as the Amsterdam UMC sample includes more progressed cases compared to the PPMI sample. This was particularly evident in the non-significant performances obtained when the models trained on the PPMI dataset alone were tested on the Amsterdam UMC dataset (see supplemental Table S7). Since, our focus was primarily on evaluating the models’ ability to predict ICD from a statistical perspective, e.g., to understand the factors that contribute to this prediction, rather than developing a fully implementable clinical decision tool, our conclusions are based mainly on the cross-validation metrics. Another limitation is that fewer follow-up assessments were obtained for the Amsterdam UMC sample.

In conclusion, our study shows that clinical variables, and presence of anxiety in particular, of DRT-naive PD patients might indicate vulnerability for future ICD development, but these are not sufficient to provide accurate predictions at level of the individual patient to optimize the clinical management. Neither DAT-SPECT or genetic data improved the predictability over demographic and clinical variables.

Methods

Pre-registration and reporting

This study was pre-registered at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/g82j3). The reporting of the prediction models adheres to the TRIPOD + AI guidelines25 (supplemental material S1).

Participants

Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) is an ongoing, longitudinal cohort study that follows individuals with PD, individuals at risk of developing PD and healthy controls (HCs) with yearly, extensive assessments for over ten years using clinical, neuroimaging, and biological data26. We selected a subsample that adhered to the following criteria: a) diagnosed with PD (including the pathogenic variants GBA and LRRK2, b) enrollment prior to 2015 (to increase likelihood of adequate follow-up duration), c) an abnormal baseline DAT-SPECT scan, and d) absence of a positive screen for ICD or impulse control behavior (ICB) at baseline. All participants provided written informed consent and did not use DRT at baseline.

We enrolled patients referred to the Amsterdam University Medical Center (Amsterdam UMC) outpatient clinic for movement disorders that had one or more follow-up assessments as part of four different longitudinal studies;

-

1.

Amsterdam 1: this retrospective study (previously described in ref.11) collected data between May 2008 and December 2011. Briefly, the original cohort consisted of 31 de novo PD patients that underwent DAT-SPECT imaging, subsequently initiated dopaminergic therapy and were assessed on development of ICD approximately three years later through questionnaires and phone interviews.

-

2.

Amsterdam 2: this retrospective study collected data between May 2008 and July 2012. The original cohort consisted of 116 participants that filled out neuropsychiatric symptom questionnaires and information on medication use and quality of life at on average 3.8 years after diagnosis.

-

3.

Amsterdam 3: this prospective study (previously described in ref. 27) collected baseline data between February 2010 and November 2012. The original cohort consisted of 20 non-demented individuals with PD that underwent extensive clinical assessment at time of diagnosis and approximately three years later.

-

4.

Amsterdam 4: this prospective study was initiated to study the predictors and development of ICDs in PD, with baseline data collection between August 2014 and October 2018. The original sub-cohort consisted of 31 de novo PD patients that underwent DAT-SPECT imaging at baseline, and additional extensive clinical assessment at baseline, six-months, one year, two years and four years follow-up.

Participants at baseline a) were de novo for DRT, b) underwent a DAT-SPECT scan, and c) were free of ICD/ICB. All participants provided written informed consent, obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethical Committee.

Impulse control disorder classification

ICD/ICB was screened using the questionnaire for ICD (QUIP) and the QUIP-rating scale (QUIP-RS), for PPMI and Amsterdam UMC samples, respectively, using the published optimal cut-offs28,29,30. Individuals with PD were classified as ICD positive if they scored above the cut-off for hypersexuality, binge eating, pathological gambling, or compulsive buying at any follow-up time-point. The time to ICD development was defined as the earliest follow-up assessment that a participant developed an ICD or ICB. Individuals that screened positive for ICB (punding, hobbyism, and walkabouts (for the QUIP) or dopamine dysregulation syndrome (for the QUIP-RS)) but not for ICD, were excluded from the analysis. Individuals were classified as no-ICD if they screened negative across all time-points.

Clinical measurements

Clinical measurements and employed harmonization steps across the PPMI and Amsterdam UMC samples are outlined in Table 5. We used information for disease stage, motor symptom severity, severity of depression, anxiety and apathy symptoms, and global cognitive function. A REM sleep behavioral disorder (RBD) screener was available only for the PPMI sample. We calculated the levodopa-equivalent daily dose (LEDD) at each time-point as earlier described in ref. 31.

DAT-SPECT image acquisition

In the PPMI sample, [123I]FP-CIT SPECT was used to measure presynaptic striatal dopamine transporter density. Patients were pre-treated with stable iodine to reduce the thyroid uptake of [123I]FP-CIT. Four hours ( ± 30 min) before image acquisition, 123I-DaTscanTM was intravenously administered in a dose between 111-185 mBq. Raw projection data was acquired into a 128 × 128 matrix with low-energy high resolution parallel hole collimators using a circular step and shoot mode with each step moving 3 degrees for a total of 60 projections per detector (180 degrees rotation per detector) for dual head systems, 30 seconds per projection, with a 20% energy window centered on 159 keV ( ± 10%) for 123IDaTscan™ and acquisition zoom of 1.23.

SPECT raw projection data was imported to a HERMES (Hermes Medical Solutions, Skeppsbron 44, 111 30 Stockholm, Sweden) system for iterative (HOSEM) reconstruction. The HOSEM reconstructed files were then transferred to the PMOD (PMOD Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland) where Attenuation correction ellipses where drawn on the images and a Chang 0 attenuation correction was applied images utilizing a site specific mu that was empirically derived from phantom data acquired during site initiation for the trial. Once attenuation correction was completed a standard Gaussian 3D 6.0 mm filter was applied.

In the Amsterdam UMC sample, [123I]FP-CIT SPECT was used to measure presynaptic striatal dopamine transporter density. Patients orally received potassium perchlorate to block thyroid update of free radioactive iodide. Three hours before image acquisition, [123I]FP-CIT was intravenously administered in a dose of approximately 185 MBq (specific activity >185MBq/nmol; radiochemical purity >99%; produced according to good manufacturing practices criteria at GE Healthcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Static images were subsequently obtained for 30 min (60 × 30 s views per head over a 180° orbit on a 128 × 128-pixel matrix) using a dual-head gamma camera (E.Cam; Siemens, Munich, Germany) with a fan-beam collimator. Image reconstruction was performed using a filtered back projection with a Butterworth filter (order 8, cut-off 0.6 cycles/cm).

Image post-acquisition processing and segmentation

We spatially normalized the DAT-SPECT volumes to Montreal Neurologic Institute coordinates with SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) using a previously published template32. A histogram matching method33, was utilized to normalize voxel intensities to reduce inter-subject/site differences. We delineated eight volumes of interest (VOIs), namely ventral striatum, anterior putamen, posterior putamen and caudate nucleus (all left and right) using FSL’s Structural Striatal Atlas34. As pre-registered, thalamic ROIs were also segmented with FSL atlas, but they were not used in the analysis due to very low signal-to-noise ratio. The cerebellum was manually delineated and used as reference region (representing non-specific binding) in SBRs calculation.

Specific binding ratios, radiomics and deep learning (latent) features extraction

We defined the striatal SBR using Eq. 1;

where, I is the average voxel intensity.

We used the Pyradiomics library35 to extract 1232 radiomic features from each striatal VOI, considering the original, as well as derived volumes using Wavelet decompositions and laplacian of gaussian filters. We used a fixed bin-width option for image discretization prior to feature extraction, to maintain the relative difference between the discretized image contrasts, as significantly lower DAT striatal uptake was previously reported in individuals with an ICD9,10. We considered the average intensity ranges of each region in this process, to ensure that the number of bins of the discretized VOIs ranged between 16 and 130, as recommended by the pyradiomics developers. We extracted 18 first order statistics, 24 features from the Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), 16 features from the Gray Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM), 16 features from the Gray Level Size Zone (GLSZM), and 14 features from the Gray Level Dependence Matrix (GLDM), from original image, as well as from 8 different wavelet decompositions and 5 different LoG sigma levels (1–5 mm), resulting into a total of 1232 features per VOI.

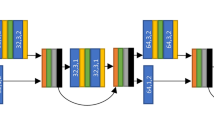

We implemented a 3D deep autoencoder in Tensorflow/Keras 2.0 DL python library (https://keras.io/), by adjusting the architecture previously described in ref. 13, to extract latent from the striatal regions. The autoencoder network was trained on cropped volumes defined with a fixed-size bounding box of 32 x 32 x 24 voxels applied to the segmented striatum on the preprocessed scans. Image intensities of the cropped volumes were further normalized to [0–1] range. The DAT-SCANS of the healthy controls were also included to increase the sample size. Artificial image augmentation was also employed by horizontal flipping (left < ->right) of a random fraction of the input images within each training batch. The network’s encoder part consisted of three consecutive blocks, each including a 3 × 3 × 3 convolutional layer with a leaky rectified linear unit (Leaky ReLU), followed by a batch normalization layer, and a 2 × 2 × 2 max-pooling layer. The decoder part of the network consisted of three consecutive blocks, including a batch normalization layer, a 3 × 3 × 3 convolutional layer with ReLU activation and 2 × 2 × 2 upsampling layers. A final 3D convolution layer without activation was used on top. A fully connected layer with 1024 nodes was used in the network bottleneck. Model training considered Adam optimization and the Mean Squared Error loss. The trained model bottleneck was used to extract 1024 latent features from the PD images for the subsequent models.

Genetic information

PPMI genetic data were obtained with NeuroX genotyping array and whole Exome sequencing. We used the PLINK 1.9 software (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/) to extract 16 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of 13 genes, previously associated with increased risk of ICD development2,3,4,6; DRD1 (rs5326), DRD2/ANKK1 (rs1800497), DRD3 (rs6280), OPRM1 (rs1799971, rs677830), OPRK1 (rs702764), SLC22A1 (rs628031), NRG1 (rs3924999), DDC (rs1451375, rs3837091), HTR2A (rs6313), TPH2 (rs4290270, rs7305115), COMT (rs4680), NOS1 (rs2682826) and GRIN2B (rs7301328).

Machine learning

We trained logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), gradient boosting (GB) and multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifiers with scikit-learn library (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/) in Python (version 3.9), using the clinical features subset alone, the clinical+radiomic features subset and the clinical+latent features subset. Two additional models considering clinical+genetic, and clinical+genetic+radiomic features were evaluated on the PPMI dataset only, as the Amsterdam UMC sample did not include genetic data. We excluded participants with missing SNP data. Missing values of clinical features were imputed with scikit-learn iterative imputer. All input values were standardized to zero mean and unit variance. We employed two-step feature selection to keep a smaller subset of radiomic features. First, we reduced the dimensionality of the radiomic feature space to a predefined number of 50 features using the minimum redundance-maximum relevance algorithm. We subsequently identified the optimal feature subset using logistic regression with l1 penalty. Models were tested with stratified 5-fold cross-validation, repeated 10 times. Feature imputation, standardization and selection transformations were separately learnt from training and applied to testing dataset splits. Nested 5-fold cross-validations and grid-search were utilized for hyperparameter tuning. Additionally, we trained the models on the PPMI and tested on the Amsterdam UMC samples. Classification performance was assessed with balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under curve (AUC). Permutation feature importances (30 permutations), were calculated to measure the contribution of each input feature to the fitted models’ statistical performance, with the mean decrease in accuracy (MDA) metric. An overview of the methodology is depicted in Fig. 3.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.236). We performed univariate independent samples t-tests, to compare demographic and clinical information of the PPMI and Amsterdam UMC datasets. For skewed distributions and categorical variables, we used Mann-Whitney or Fisher’s exact tests, respectively. To assess differences between ICD vs No-ICD groups, we used linear/logistic regression with the clinical features or SBRs as dependent variable and group as fixed factor. We additionally performed linear regression including cohort and its interaction with group as covariate of interest, and age, sex and education level as additional covariates. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)37. We tested ML models’ statistical significance against chance with permutation testing. We performed pairwise comparisons of classification performances across models and feature subsets either using the paired-samples t-tests, in case of identical train-test splits, corrected for repeated k-fold cross-validation38,39, or the Welch’s t-test in case of non-identical train-test splits. All significance levels were set to a = 0.05.

Data availability

Data used in the preparation of this article was obtained on 1-9-2023 from the PPMI database (http://www.ppmi-info.org/access-dataspecimens/download-data) RRID:SCR_006431. For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org. The Amsterdam UMC dataset is not publicly available according to GDPR.

Code availability

Codes are available at www.github.com/sciqd/Learn_2_control.

References

Vriend, C. The neurobiology of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: from neurotransmitters to neural networks. Cell Tissue Res. 373, 327–336 (2018).

Dulski, J., Uitti, R. J., Ross, O. A. & Wszolek, Z. K. Genetic architecture of Parkinson’s disease subtypes - Review of the literature. Front Aging Neurosci. 14, 1023574 (2022).

Kraemmer, J. et al. Clinical-genetic model predicts incident impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 87, 1106–1111 (2016).

Weintraub, D. et al. Genetic prediction of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 9, 936–949 (2022).

Faouzi, J. et al. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease From Clinical and Genetic Data. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med Biol. 3, 96–107 (2022).

Redenšek, S., Jenko Bizjan, B., Trošt, M. & Dolžan, V. Clinical and Clinical-Pharmacogenetic Models for Prediction of the Most Common Psychiatric Complications Due to Dopaminergic Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease. Int J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 496–504 (2020).

Erga, A. H. et al. Dopaminergic and Opioid Pathways Associated with Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 9, 109 (2018).

Navalpotro-Gomez, I. et al. Nigrostriatal dopamine transporter availability, and its metabolic and clinical correlates in Parkinson’s disease patients with impulse control disorders. Eur. J. Nucl. Med Mol. Imaging 46, 2065–2076 (2019).

Martini, A. et al. Dopaminergic Neurotransmission in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease and Impulse Control Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of PET and SPECT Studies. Front. Neurol. 9, 1018 (2018).

Smith, K. M., Xie, S. X. & Weintraub, D. Incident impulse control disorder symptoms and dopamine transporter imaging in Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 87, 864–870 (2016).

Vriend, C. et al. Reduced dopamine transporter binding predates impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 29, 904–911 (2014).

Rahmim, A. et al. Improved prediction of outcome in Parkinson’s disease using radiomics analysis of longitudinal DAT SPECT images. Neuroimage Clin. 16, 539–544 (2017).

Hosseinzadeh, M. et al. Prediction of cognitive decline in parkinson's disease using clinical and DAT SPECT imaging features, and hybrid machine learning systems. Diagnostics (Basel) 13, 1691 (2023).

Rahmim, A. et al. Application of texture analysis to DAT SPECT imaging: Relationship to clinical assessments. Neuroimage Clin. 12, e1–e9 (2016).

Weintraub, D. & Claassen, D. O. Impulse Control and Related Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Int Rev. Neurobiol. 133, 679–717 (2017).

Jesús, S. et al. Integrating genetic and clinical data to predict impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 28, 459–468 (2021).

Ihle, J. et al. Parkinson’s disease polygenic risk score is not associated with impulse control disorders: A longitudinal study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 75, 30–33 (2020).

Faouzi, J., Couvy-Duchesne, B., Bekadar, S., Colliot, O. & Corvol, J. C. Exploratory analysis of the genetics of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease using genetic risk scores. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 86, 74–77 (2021).

Ricciardi, L., Lambert, C., De Micco, R., Morgante, F. & Edwards, M. Can we predict development of impulsive-compulsive behaviours in Parkinson’s disease? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 89, 476–481 (2018).

Hinkle, J. T., Perepezko, K., Gonzalez, L. L., Mills, K. A. & Pontone, G. M. Apathy and Anxiety in De Novo Parkinson’s Disease Predict the Severity of Motor Complications. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 8, 76–84 (2021).

Meng, D., Jin, Z., Wang, Y. & Fang, B. Longitudinal cognitive changes in patients with early Parkinson’s disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 2259–2266 (2023).

Roussakis, A. A., Lao-Kaim, N. P. & Piccini, P. Brain Imaging and Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 19, 67 (2019).

Hernadi, G. et al. White matter hyperintensities associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 13, 10594 (2023).

Gan, C. et al. Aberrant brain topological organization and granger causality connectivity in Parkinson’s disease with impulse control disorders. Front Aging Neurosci. 16, 1364402 (2024).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, e078378 (2024).

Initiative, P. P. M. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 629–635 (2011).

Trujillo, J. P. et al. Impaired planning in Parkinson’s disease is reflected by reduced brain activation and connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 3703–3715 (2015).

Weintraub, D. et al. Validation of the questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 24, 1461–1467 (2009).

Weintraub, D. et al. Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease-Rating Scale. Mov. Disord. 27, 242–247 (2012).

Evans, A. H. et al. Scales to assess impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease: Critique and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 34, 791–798 (2019).

Jost, S. T. et al. Levodopa Dose Equivalency in Parkinson’s Disease: Updated Systematic Review and Proposals. Mov. Disord. 38, 1236–1252 (2023).

García-Gómez, F. J. et al. [Elaboration of the SPM template for the standardization of SPECT images with 123I-Ioflupane]. Rev. Esp. Med Nucl. Imagen Mol. 32, 350–356 (2013).

Salas-Gonzalez, D., Górriz, J. M., Ramírez, J., Illán, I. A. & Lang, E. W. Linear intensity normalization of FP-CIT SPECT brain images using the α-stable distribution. Neuroimage 65, 449–455 (2013).

Tziortzi, A. C. et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage 54, 264–277 (2011).

van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 77, e104–e107 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2021 [Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 57, 289–300 (1995).

Nadeau, C. & Bengio, Y. Inference for the generalization error. Mach. Learn. 52, 239–281 (2003).

Bouckaert, R., Frank, E., Dai, H., Srikant, R. & Zhang, C. Evaluating the replicability of significance tests for comparing learning algorithms. Adv. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., Proc. 3056, 3–12 (2004).

Laansma, M. A. et al. International Multicenter Analysis of Brain Structure Across Clinical Stages of Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 36, 2583–2594 (2021).

Hentz, J. G. et al. Simplified conversion method for unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale motor examinations. Mov. Disord. 30, 1967–1970 (2015).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. psychiatry 4, 561–571 (1961).

Yesavage, J. A. & Sheikh, J. I. 9/Geriatric depression scale (GDS) recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. gerontologist. 5, 165–173 (1986).

Maust, D. et al. Psychiatric rating scales. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 106, 227–237 (2012).

Spielberger, C. D., Goruch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. & Jacobs, G. Manual for the state-trait inventory STAI (form Y). Mind Garden, Palo Alto, CA, USA. (1983).

van Steenoven, I. et al. Conversion between mini-mental state examination, montreal cognitive assessment, and dementia rating scale-2 scores in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 29, 1809–1815 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in whole (Grant number MJFF-022801) by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research (MJFF). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript. PPMI – a public-private partnership – is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, and funding partners; 4D Pharma, Abbvie, AcureX, Allergan, Amathus Therapeutics, Aligning Science Across Parkinson's, AskBio, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, BIAL, BioArctic, Biogen, Biohaven, BioLegend, BlueRock Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calico Labs, Capsida Biotherapeutics, Celgene, Cerevel Therapeutics, Coave Therapeutics, DaCapo Brainscience, Denali, Edmond J. Safra Foundation, Eli Lilly, Gain Therapeutics, GE HealthCare, Genentech, GSK, Golub Capital, Handl Therapeutics, Insitro, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine, Lundbeck, Merck, Meso Scale Discovery, Mission Therapeutics, Neurocrine Biosciences, Neuron23, Neuropore, Pfizer, Piramal, Prevail Therapeutics, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Sun Pharma Advanced Research Company, Takeda, Teva, UCB, Vanqua Bio, Verily, Voyager Therapeutics, the Weston Family Foundation and Yumanity Therapeutics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.V.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Image processing, Image analysis, Machine Learning analysis, Writing original draft. T.vB.: Data curation, Investigation, Univariate Analysis, Writing original draft, Writing review & editing. G.vW., J.B., D.W., H.B., O.vdH.: Validation, Writing review & editing, C.V.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.B. is a consultant at GE Healthcare (all related payments to the institute). D.W. receives research funding and salary support from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for serving on the Executive Steering Committee of the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative study. The authors declare no other financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vamvakas, A., Van Balkom, T., Van Wingen, G. et al. Prediction of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease through a longitudinal machine learning study. npj Parkinsons Dis. 12, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01248-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01248-w