Abstract

An infection of SARS-CoV-1, the causative agent of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), may be followed by long-term clinical sequala. We hypothesized a greater 20-year multimorbidity incidence in people hospitalized for SARS-CoV-1 infection than those for influenza during similar periods. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a territory-wide public healthcare database in Hong Kong. All patients aged ≥15 hospitalized for SARS in 2003 or influenza in 2002 or 2004 with no more than one of 30 listed chronic disease were included. Demographics, clinical history, and medication use were adjusted for in the inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighted Poisson regression analyses. We identified 1255 hospitalizations for SARS-CoV-1 infection and 687 hospitalizations for influenza. Overall crude multimorbidity incident rates were 1.5 per 100 person-years among SARS patients and 5.6 among influenza patients. Adjusted multimorbidity incidence rate ratio (IRR) was estimated at 0.78 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70–0.86) for SARS patients compared with influenza patients. Analysis by follow-up period shows a potentially greater risk among SARS patients in the first year of follow-up (IRR 1.33, 95% CI 0.97–1.84), with the risk in influenza patients increasing in subsequent years. Subgroup analyses by age and sex showed consistent results with the main analysis that SARS-CoV-1 infection was not followed by a higher incidence of multimorbidity than influenza. Notable differences in the patterns of multimorbidity were identified between the two arms. To conclude, we found no evidence of a higher multimorbidity incidence after hospitalization for SARS than for influenza over the long-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SARS-CoV-1, the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), is an ancestral viral strain of SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-191. Unlike SARS-CoV-2 however, it has not caused remotely as disastrous an impact on humanity as the COVID-19 pandemic did2. The only notable SARS epidemic took place in China in early 2003, before surprisingly dying down in the same year without a noticeable re-emergence3.

Like recent studies on long COVID syndrome and other adverse sequalae4,5, there have been reports concerning prognosis of SARS relative to other respiratory infections, apart from a very high case-fatality rate from SARS, i.e., acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome6. Indeed, survivors of SARS are reported to have an elevated risk of developing long-term conditions, such as dyspnea, pulmonary fibrosis, anxiety and depression6. It is, thus, probable that they are also at a heightened risk of developing multimorbidity, commonly referred to as the cooccurrence of two or more chronic conditions in an individual7,8. The incidence and prevalence of multimorbidity, which is consistently associated with poorer quality of life9, more healthcare utilization10,11, and greater mortality risks12, are highly indicative of the chronic health care burden in a health system10,13. Nevertheless, there is no existing study examining the long-term impact of SARS on the incidence of multimorbidity.

Hong Kong was one of the places affected most significantly by SARS in 2003, with more than 1700 people being infected and nearly 300 people dying from it14, out of a 7-million population. With a unified public healthcare system under the Hospital Authority (HA) and comprehensive digitalized longitudinal clinical records, we aimed to conduct a retrospective cohort study to compare SARS survivors with patients hospitalized for influenza, over an observation period of two decades up to 2022. Given the previous research on the severe adverse sequalae following SARS15, we hypothesize a greater multimorbidity incidence following SARS-CoV-1 infection-related hospitalization compared with an influenza hospitalization which is commonly seen and routinely managed.

Methods

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the clinical records of a territory-wide database covering patients attending public healthcare facilities, which were maintained in the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) of the HA. This database has been used for numerous excellent large-scale epidemiologic studies previously16,17. The HA is the sole provider of public inpatient services and a major provider of public outpatient services in Hong Kong, covering more than 80% of all healthcare service users in the city. The vast majority of patients with chronic diseases are regularly followed up in HA facilities. All disease diagnoses in this study were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes within CDARS. Previous research has validated this coding system’s reliability, with positive predictive values exceeding 85% for various diseases18,19.

Cohort selection

As children under the age of 15 are less representative of the population at risk of developing multimorbidity, our cohort was defined as all people aged 15 or older who were hospitalized for influenza for the first time in 2002 or 2004 (as the influenza arm) or SARS in 2003 (as the SARS arm). Also, since the age distribution of SARS patients, the exposed group of interest, did not significantly skew towards children under 15, we selected this group of influenza patients with a similar demographic profile to enable a fair and meaningful comparison with the SARS group.

Deaths, co-existing influenza and SARS, or the occurrence of multimorbidity (the outcome of interest, please see the next section for more details) on or before the index date were used as exclusion criteria. We defined the index date, i.e., start of observation, as the date of discharge from influenza or SARS hospitalization, and followed the patients until the occurrence of the outcome, i.e., multimorbidity, all-cause mortality, or the end of data availability. To ensure inclusion of serious cases requiring a certain length of hospital stay, we excluded records with the same admission and discharge dates as these records were considered invalid because they indicated transient non-critical admissions or even mild conditions, or potential system input errors. In case of multiple hospitalizations, the latest episode was used as the index hospitalization. The influenza arm of the cohort was identified using the ICD-9-CM code: 487, while the SARS arm was identified from a previously established database maintained by the Department of Health for the purpose of a more comprehensive follow-up of patients20.

Outcome

Multimorbidity was adopted as the primary study outcome, while specific listed chronic conditions were analyzed as secondary outcomes. A widely used list of 30 chronic conditions was used for the definition of multimorbidity21, with the corresponding ICD-9-CM codes shown in S1 Table. The 30 conditions were chosen to encompass a wide variety of diseases requiring different types of care and specialist attention, including alcohol misuse, asthma, atrial fibrillation, chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic pain, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic viral hepatitis B, cirrhosis, dementia, depression, diabetes, epilepsy, hypertension, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, lymphoma, metastatic cancer, multiple sclerosis, myocardial infarction, non-metastatic cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate), Parkinson’s disease, peptic ulcer disease, peripheral vascular disease, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, schizophrenia, severe constipation, and stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). The diagnosis of the second listed chronic condition in the patient was operationalized as the occurrence of multimorbidity.

Statistical analysis

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using multivariable Poisson regression analysis. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to balance between the two arms in terms of the baseline characteristics including age, sex, chronic condition and medicine use (S2 Table) at baseline. We calculated the standard mean difference for continuous variables and the proportion difference for dichotomous variables before and after weighting to examine the balance between the arms. We further included variables with a standard mean (SMD) or proportion difference that were greater than 0.1 in the Poisson regression as covariates. Subgroup analyses were performed separately by sex and age group, i.e., <40 or ≥40 years. Covariates were reweighed in every subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to test for the robustness of findings. First, we included influenza hospitalizations in 2003, coinciding with the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, to consider the outbreak’s potential influence on influenza cases that year. Second, index date was redefined as one year after the discharge date to capture only the post-acute effects. Third, we adopted three diseases as the definition of the multimorbidity outcome. Fourth, we performed multivariable Poisson regression to adjust for covariates instead of using IPTW to weigh the sample based on the covariates. Fifth, we conducted a competing risk regression adjusting for all-cause mortality as a potential competing risk outcome. Sixth, we operationalized antivirals and antibiotics only during the current episode as covariates and repeated the main analysis. Seventh, given the seasonality of influenza, we further stratified the influenza group into peak and non-peak season admissions. According to the Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection, the annual peak influenza seasons in the region occur from January to April and July to August22. We replicated multivariable models with such further stratification to detect any impact of influenza seasonality on the findings. Lastly, we stratified the observation period into less than one year, 1–5 years, 6–10 years and beyond 10 years to observe difference across periods.

All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 and R software version 4.0.5. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was taken as significant in this study.

Results

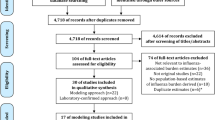

Figure 1 shows the procedures of cohort selection. After excluding patients who met exclusion criteria such as death on or before the index date or living with more than one chronic disease at the baseline, we eventually identified 678 influenza inpatients from 2002 or 2004 and 1255 SARS inpatients from 2003 to be included in the final study cohort.

Cohort characteristics

Patient demographics and the history of chronic conditions and medications were summarized in Table 1. There were 340 (49.5%) males admitted with influenza and 496 (39.5%) males admitted with SARS. The mean age of influenza arm was 58.7 (Standard Deviation [SD] 24.40) and that of SARS group was 38.8 (SD 14.61). Five hundred and twenty-six patients had one chronic condition at baseline. The most common chronic conditions in the influenza group were chronic pulmonary disease (9.9%), hypertension (7.6%), diabetes (4.5%) and asthma (4.5%), while the chronic conditions with a higher proportion within SARS group were chronic pain (2.2%) and hypertension (2.1%). As for medications within one year before index date, most patients in both groups had a history of taking antibacterial drugs (Influenza group:87.3%, SARS group:99.2%) and antiviral drugs (Influenza group:51.2%, SARS group:93.6%). After IPTW, some characteristics like age, sex, and stroke at baseline between the 2 groups were still unbalanced, as indicated by an SMD or proportion difference of >0.1.

Weighted analysis of multimorbidity incidence

A total of 376 influenza inpatients (54.7%), compared to 311 SARS inpatients (24.8%) developed multimorbidity during follow-up. The crude multimorbidity incidence rate per 100 person-years was 5.6 in influenza arm and 1.5 in SARS arm. As shown in Fig. 2, cumulative incidence of multimorbidity among SARS patients increased faster than that of influenza group in approximately the first 2700 days after discharge from hospital while in the subsequent years, the cumulative incidence of multimorbidity in the SARS arm became slightly lower than the influenza arm. Figure 3 showed chord diagrams by influenza and SARS groups exemplifying the relative frequencies (represented by ribbon area) of chronic condition pairings with a deeper color representing a higher frequency. Hypertension-diabetes was the most common chronic condition cooccurrence in both groups. However, the coexistence of depression and chronic pain was much more obvious among SARS inpatients.

As shown in Table 2, after IPTW and multivariable adjustment, patients of the SARS arm was shown to have a significantly lower multimorbidity incidence rate than those of influenza arm (IRR 0.78, 95%CI 0.70–0.86, P < 0.0001). Adjusted subgroup analysis showed no evidence of differences between women between the two arms (IRR 1.00, 95%CI 0.88–1.14, P = 0.9661), while the result for men were similar to the overall result (IRR 0.68, 95%CI 0.57–0.80, P < 0.0001). In age group-stratified analyses, those aged younger than 40 in the SARS arm had a significantly lower risk of multimorbidity than those in the influenza arm (IRR 0.86, 95%CI 0.77–0.96, P = 0.0091). No significant difference was estimated between the arms in those aged 40 years or older (IRR 0.97, 95%CI 0.76–1.23, P = 0.7865).

The results of the analyses of the secondary outcomes are shown in S3 Table. For specific diseases, analysis showed there is a significantly higher incidence of depression, diabetes, non-metastatic cancer, and chronic pain among hospitalized patients with SARS.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis using influenza patients hospitalized in 2003, despite fewer individuals compared to the primary analysis with 2002 and 2004 data, the incidence rate of multimorbidity remained consistent with the primary findings, showing no significant difference between the SARS and influenza groups (S4 Table). Moving the index date to one year after discharge, we found that the risk of multimorbidity was slightly lower in the SARS arm, similar with the results of main and subgroup analysis (S5 Table). In the sensitivity analysis regarding the cooccurrence of three chronic diseases as multimorbidity, results were similar to the main analyses for primary outcome except for the subgroup younger than 40 years (S6 Table). The different result, however, was based on only one outcome event in each of the two arms. No significant differences in multimorbidity incidence rates were observed by using full multivariable Poisson regression instead of IPTW to address the covariates (S7 Table). No notable deviations from the main findings are observed in the sensitivity analyses using a competing risk regression to adjust competing risks from mortality (S8 Table) and considering only antivirals and antibiotics during the current episode as the covariates (S9 Table). As shown in S10 Table, no significant impact from the seasonality of influenza on the main findings was observed (IRR 0.76, 95%CI 0.55–1.04, P = 0.0838). S11 Table shows the stratified results for different observation periods and supports the pattern shown in Fig. 2 that cumulative incidence of multimorbidity among SARS patients increased faster in earlier periods.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of individuals over two decades, we did not identify a higher multimorbidity incidence following a SARS-related hospitalization compared with an influenza-related hospitalization. We showed that multimorbidity incidence after SARS-related hospitalizations increased at a faster pace in the first couple of years, but the difference gradually became negligible over the long follow-up period. Sub-analyses by age and sex were largely consistent with the main findings, with sensitivity analyses using influenza cases from a different period, delaying the index date by one year, using three diseases as the threshold to define multimorbidity, adjusting for competing risks from all-cause mortality, and using an alternative covariates selection and adjustment approach all supporting the robustness of the main results. Nevertheless, we identified notable specific differences in the multimorbidity patterns between the two groups.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the 20-year multimorbidity incidence of SARS survivors in comparison with influenza acquired in similar periods. It adds to other studies reporting on the clinical sequala of SARS23,24 and showed that, over the long term, overall multimorbidity was not higher in SARS survivors than influenza patients. It provides useful information on how acute viral infections with coronavirus may translate into chronic healthcare burden and it also represents a rare scientific inquiry to examine multimorbidity as an outcome which encompasses various diseases and disorders over a prolonged period.

The faster increase in multimorbidity incidence in the first few years of discharge from a SARS episode was likely due to health check-ups or follow-up consultations after the infection because of increased health awareness25. For instance, the higher incidence of diabetes, which typically requires health checks to diagnose, was one of the diseases the incidence rate of which was found to be higher in the SARS arm than in the influenza arm. Indeed, our study identified notable specific differences in the patterns of multimorbidity developing in SARS survivors compared to influenza patients. Specifically, SARS survivors were more prone to conditions like chronic pain, depression, and diabetes, while influenza patients showed greater risks of cardiovascular issues, such as atrial fibrillation and heart failure, as well as neurological conditions like dementia. These differences might reflect SARS’s intense inflammatory effects, potentially driving pain and mental health challenges, whereas influenza may worsen pre-existing cardiovascular and neurological vulnerabilities15,26. Consistent with previous research27, we found that the pattern of chronic pain – depression was more common among those discharged from a SARS episode, suggesting that types of care required over the long run after a respiratory infection may also differ across various sociodemographic and disease groups. These findings have important implications for the long-term management of patients with severe respiratory infections and suggest the need for tailored interventions to address the unique needs of different patient populations. The identification of specific multimorbidity patterns may also guide the development of targeted screening and prevention strategies for certain subgroups of patients28, which could ultimately lead to improved health outcomes and quality of life.

The strengths of this study include the use of a large population-based dataset with a long follow-up period, which allowed us to investigate the long-term consequences of respiratory infections. Additionally, we used a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity that considered a wide range of chronic diseases, which is important as the management of multimorbidity requires a holistic approach. However, our study also has some limitations. First, we were unable to account for unobserved potential confounders such as smoking and other lifestyle factors, which may have affected our results. Second, our study only included individuals who were hospitalized for respiratory infections, and therefore our findings may not be generalizable to patients who were not hospitalized or who were hospitalized for other reasons. Third, we were unable to distinguish between different types of influenza viruses, and therefore our comparison group may not have been entirely homogeneous. Fourth, potential underdiagnosis of chronic diseases due to variations in healthcare utilization patterns may underestimate their prevalence in both groups. However, these variations and potential underestimation are likely similar between them, with limited impact on the validity in our comparative analysis. Last, our study only included individuals Hong Kong where a predominantly ethnic Chinese population resides, and therefore our findings may not be generalizable to other populations or healthcare systems.

In conclusion, our study found that there was no higher long-term incidence of multimorbidity among SARS survivors compared with influenza patients. However, we identified notable differences in the patterns of multimorbidity developed in these two groups, which could be attributed to differences in baseline patient characteristics. These findings highlight the need for tailored interventions and targeted screening strategies to address the unique needs of different patient populations, which could ultimately lead to improved health outcomes and quality of life.

Data Availability

Data is not available as the data custodian has not given permission for data sharing.

References

The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and namingit SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol 5, 536–544 (2020Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

Chan-Yeung, M & Xu, RH SARS: epidemiology. Respirology 8, S9–S14 (2003).

De Feng, D et al. The SARS epidemic in mainland China: bringing together all epidemiological data. Tropical Med. Int. Health 14, 4–13 (2009).

Yong, SJ Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect. Dis. 53, 737–754 (2021).

Wang, F, Kream, RM & Stefano, GB Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit.: Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 26, e928996–1 (2020).

Chan, K et al. SARS: prognosis, outcome and sequelae. Respirology 8, S36–S40 (2003).

Barnett, K et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 380, 37–43 (2012).

Johnston, MC, Crilly, M, Black, C, Prescott, GJ & Mercer, SW Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 182–189 (2019).

Makovski, TT, Schmitz, S, Zeegers, MP, Stranges, S & van den Akker, M Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 53, 100903 (2019).

McPhail, SM Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 9, 143–156 (2016).

Lai, FT et al. Multimorbidity in middle age predicts more subsequent hospital admissions than in older age: a nine-year retrospective cohort study of 121,188 discharged in-patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 61, 103–111 (2019).

Cezard, G, McHale, CT, Sullivan, F, Bowles, JKF & Keenan, K Studying trajectories of multimorbidity: a systematic scoping review of longitudinal approaches and evidence. BMJ Open 11, e048485 (2021).

Lai, FT et al. Sex-specific intergenerational trends in morbidity burden and multimorbidity status in Hong Kong community: an age-period-cohort analysis of repeated population surveys. BMJ Open 9, e023927 (2019).

Organization, W. H. Summary table of SARS cases by country, 1 November 2002-7 August 2003. Wkly epidemiol rec. 78, 310–311 (2003).

Moldofsky, H & Patcai, J Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 11, 1–7 (2011).

Lau, WC et al. Association between dabigatran vs warfarin and risk of osteoporotic fractures among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA 317, 1151–1158 (2017).

Wong, AY et al. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population based study. BMJ 352, h6926 (2016).

Ye, Y et al. Validation of diagnostic coding for interstitial lung diseases in an electronic health record system in Hong Kong. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug. Saf. 31, 519–523 (2022).

Kwok, WC, Tam, TCC, Sing, CW, Chan, EWY & Cheung, C-L Validation of diagnostic coding for asthma in an electronic health record system in Hong Kong. J. Asthma Allergy 16, 315–321 (2023).

Sing, CW, Tan, KCB, Wong, ICK, Cheung, BMY & Cheung, CL Long-term outcome of short-course high-dose glucocorticoids for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a 17-year follow-up in SARS survivors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, 1830–1833 (2021).

Tonelli, M et al. Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 15, 31 (2015).

Centre for Health Protection DoH. Seasonal Influenza: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administration Region; 2023 [Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/14843.html.

O’Sullivan, O Long-term sequelae following previous coronavirus epidemics. Clin. Med. 21, e68–e70 (2021).

Zhang, P et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res. 8, 8 (2020).

Tansey, CM et al. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 1312–1320 (2007).

Macias, AE et al. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine 39, A6–a14 (2021).

Cheng, SK, Wong, CW, Tsang, J & Wong, KC Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Psychol. Med. 34, 1187–1195 (2004).

Lai, FTT et al. Comparing multimorbidity patterns among discharged middle-aged and older inpatients between Hong Kong and Zurich: a hierarchical agglomerative clustering analysis of routine hospital records. Front. Med. 8, 651925 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Hospital Authority for the provision of data. FTTL and ICKW are partially supported by the Laboratory of Data Discovery for Health funded by AIR@InnoHK administered by Innovation and Technology Commission, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FTTL, ICKW, and CW designed and directed this study. FTTL and ICKW had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CW performed the acquisition and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

EYFW has received research grants from the Health Bureau of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Hong Kong Security Bureau, and the Hong Kong Research Grants Council, outside the submitted work. ICKW reports research funding outside the submitted work from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Bayer, GSK, Novartis, the Hong Kong Research Grants Council, the Health Bureau of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, National Institute for Health Research in England, European Commission, and the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia; has received speaker fees from Janssen and Medice in the previous 3 years; and is an independent non-executive director of Jacobson Medical in Hong Kong. FTTL has been supported by the RGC Postdoctoral Fellowship under the Hong Kong Research Grants Council and has received research grants from the Health Bureau of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Hong Kong and HA (UW 20-172). As only anonymized medical records were analyzed no informed consent was required or feasible.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, C., Sing, C.W., Wan, E.Y.F. et al. Multimorbidity incidence following hospitalization for SARS-CoV-1 infection or influenza over two decades: a territory-wide retrospective cohort study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 18 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00424-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00424-y