Abstract

This meta-analysis aims to examine the association between maternal asthma and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring. A literature search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from electronic database inception to October 2024 for studies on the relationship between asthma and ASD/ADHD. The definition of maternal asthma was “asthma existing prior to childbirth”. The primary outcome was the incidence of ASD/ADHD in the offspring. This meta-analysis incorporated 5 cohort studies and 7 case-control studies. The statistical results suggested that there is a higher incidence of ASD (odds ratio (OR) = 1.36, 95% confidence interval (95%CI) = 1.28–1.44, P < 0.001) and ADHD (OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.37–1.51, P < 0.001) in offspring with maternal asthma compared to the control group. The subgroup analysis revealed that there was no difference in ASD incidence between maternal asthma group and control group in subgroup of female (OR = 1.81, 95%CI = 0.72–4.25, P = 0.205). However, in subgroup of male, the incidence of ASD was higher in the maternal asthma group than the control group (OR = 1.28, 95%CI = 1.01–1.61, P = 0.04). Furthermore, an elevated incidence of ADHD was observed in the maternal asthma group compared to the control group, both in male offspring (OR = 1.36, 95%CI = 1.30–1.42, P < 0.001) and female offspring (OR = 1.45, 95%CI = 1.38–1.53, P < 0.001) subgroups. This study indicates that maternal asthma may have a potential association with ASD and ADHD in the offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders typically emerge in early childhood and are characterized by impairments in personal, social, academic, and occupational functioning1. Increasing evidence suggests that maternal immune activation plays a role in the etiology of these disorders2. Maternal asthma—defined in this study as asthma existing prior to childbirth—is a known trigger of maternal immune activation, which may adversely affect fetal neurodevelopment3. Findings from animal studies, human observational research, and reviews have all suggested a potential association between maternal asthma and neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring4,5,6,7. However, no prior meta-analysis has systematically evaluated this relationship. Given the high prevalence of both asthma and ASD/ADHD and absence of relevant meta-analysis, we conducted this meta-analysis to assess the association between maternal asthma and the risk of ASD/ADHD in offspring8,9.

Methods

The objective of this study was to investigate the potential correlation between maternal asthma and the subsequent development of ASD and ADHD in the offspring. The following electronic databases, which covered studies from the inception of the database to October 2024, were retrieved in the course of this investigation: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The search formula used a combination of free terms and medical subject headings terms, mainly including: (asthma) AND (ASD OR autism spectrum disorders OR autism spectrum disorder OR ADHD OR attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity OR attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder OR attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorders). Detailed search strategies are provided in the Supplementary Search Strategy. The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024583889).

Inclusion criteria:

-

(1)

The maternities in the exposed group suffered from asthma.

-

(2)

The maternities in the control group were free of asthma.

-

(3)

The outcome was the prevalence of ASD/ADHD in the offspring.

-

(4)

The study designs belong to cohort studies or case-control studies.

Exclusion criteria:

-

(1)

The full text or data of the studies was not available.

-

(2)

The article was not written in English.

-

(3)

If the article had been updated, the most comprehensive or latest article was selected to be included.

-

(4)

Maternal asthma commenced following childbirth in the study.

Data extraction

Two assessors independently extracted data from eligible studies, with a third assessor responsible for resolving any discrepancies. The extracted data encompassed authors, publication year, country, study design, participant characteristics (gender, evaluation tool, diagnostic criteria), length of follow-up, adjusted factors, number of participants, and prevalence of ASD/ADHD in the offspring.

Based on previous studies, this study defined maternal asthma as asthma existing prior to childbirth.

Assessment of quality

Two independent assessors conducted quality assessment. In case of discrepancies, a third assessor intervened to resolve them. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale, a tool for quality assessment, was used to evaluate cohorts and case-control studies based on selection, comparability, and outcomes. Studies scoring 6 or higher were deemed high quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 12.0. The relationship between maternal asthma and offspring ASD/ADHD was examined by calculating effect sizes with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the odds ratio (OR). A positive association between maternal asthma and offspring ASD/ADHD prevalence was identified when OR > 1, while a negative association was observed when OR < 1. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the chi-square test and expressed as I2, where 0% indicated no heterogeneity, 1–25% low heterogeneity, 26–50% moderate heterogeneity, and 51–100% high heterogeneity. To account for potential heterogeneity among studies due to factors such as maternal age, race, income, parity, and education, a random-effects model was utilized to enhance the reliability of the statistical findings. If more than five articles were included, publication bias and sensitivity analyses were planned. The sensitivity analysis aimed to assess result stability, while publication bias was assessed using Begg’s test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance denoted by P < 0.05. A GRADE analysis was conducted by the GRADEpro, and the certainty of evidence was categorized into four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low.

Result

Studies selection

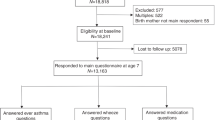

The search followed an established strategy and identified 2187 terms across four electronic databases. No additional terms were sourced elsewhere. After eliminating duplicate records, 964 articles remained. Upon reviewing titles and abstracts, 932 articles were excluded. A detailed assessment of the remaining 32 articles revealed that 12 met the criteria, while 20 were exclude4,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. The 20 excluded studies were not included for the following reasons: 6 were reviews, 2 had been updated, 10 did not present significant findings, and 2 had missing data on the outcomes. Refer to Fig. 1 for a detailed overview of the process.

Study characteristics

Table 1 presented the key characteristics of the twelve studies included in this meta-analysis, comprising five cohort studies and seven case-control studies. Among these, eight studies investigated ASD, while four focused on ADHD, spanning publication years from 2005 to 2024. The research was conducted in various countries: the United States (n = 5), Taiwan (n = 2), China (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), multicenter (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), and Australia (n = 1). The maternal asthma group encompassed over 2507/1/2025000 individuals, whereas the control group comprised more than 5.5 million individuals. Diagnosis of ASD and ADHD, as well as medication prescriptions, were the primary outcome measures in most studies. Some studies utilized assessment tools such as the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS) and autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R) to standardize the evaluation of offspring with ASD, as outlined in Table 1. Pharmacological management of maternal asthma encompassed inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, inhaled β₂-agonists, and oral corticosteroids. Adjustment for various factors, including sex, birth year, maternal age, race, education, parity, and smoking, was conducted in the majority of studies, with detailed information provided in Supplementary Tables 1-1, Supplementary Table 1-1 and Supplementary Table 1-3.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of case-control and cohort studies was completed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. All of these included studies were high quality studies, with scores ranging from 6–8. Refer to Supplementary Table 2 for the cohort study and Supplementary Table 3 for the case-control study.

ASD

The eight studies examined the correlation between maternal asthma and ASD in offspring. The pooled effect sizes revealed a heightened risk of ASD in offspring of mothers with asthma compared to the control group (OR = 1.36, 95%CI = 1.28–1.44, P < 0.001, I2 = 46.7%, Fig. 2). Subgroup analyses were performed based on gender. Among male offspring, the incidence of ASD was significantly elevated in the maternal asthma group compared to the control group (OR = 1.28, 95%CI = 1.01–1.61, P = 0.04, Fig. 3a). Conversely, in the female subgroup, there was no significant difference in ASD prevalence between the maternal asthma group and the control group (OR = 1.81, 95%CI = 0.72–4.25, P = 0.205, Fig. 3b). The GRADE analysis for the meta-analysis of the association between maternal asthma and ASD in offspring rated the certainty of evidence as low.

ADHD

In four studies examining the correlation between maternal asthma and offspring ADHD, a higher prevalence of ADHD was observed in the maternal asthma group compared to the control group (OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.37–1.51, P < 0.001, I2 = 74.2%, Fig. 4). Subgroup analyses for male and female offspring revealed a higher prevalence of ADHD in the maternal asthma group compared to the control group for both male (OR = 1.36, 95%CI = 1.30–1.42, P < 0.001, Fig. 5a) and female (OR = 1.45, 95%CI = 1.38–1.53, P < 0.001, Fig. 5b) offspring subgroups. The GRADE analysis for the meta-analysis of the association between maternal asthma and ADHD in offspring rated the certainty of evidence as very low.

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses

The Begg’s test of forest plots assessing maternal asthma with ASD in the offspring was found to reveal no significant publication bias (P = 0.902, SFig. 1). After the exclusion of each study individually, sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the results exhibit stability (SFig. 2).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 5 cohort studies and 7 case-control studies, compared to the control group, maternal asthma increased the risk of ASD and ADHD in the offspring. The pooled effect sizes revealed a higher risk of ASD (OR = 1.36, 95%CI = 1.28–1.44) and ADHD (OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.37–1.51) in offspring of mothers with asthma compared to the control group. Although all 12 included studies were rated as high quality, the GRADE analysis classified the evidence certainty as low for the meta-analysis of ASD and very low for meta-analysis of ADHD because of study design and heterogeneity. The possible mechanisms were as follows:

Maternal serotonin is transported into placental cells through the 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) transporter and organic cation transporter 3, crossing the placental barrier to reach the fetal circulation21. Serotonin plays a vital role in the structural and functional development of the fetal brain, particularly in neuronal proliferation and synaptogenesis22,23,24. In maternal asthma, immune activation leads to elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6), which promotes the diversion of tryptophan metabolism toward kynurenine at the expense of serotonin synthesis, resulting in decreased maternal serotonin levels25,26,27,28,29,30. During the initial stages of fetal neural development, serotonin is of maternal origin31,32. Therefore, maternal serotonin deficiency reduces fetal serotonin levels, impairing hippocampal and prefrontal cortex development and disrupting brain circuit formation, thereby contributing to neurodevelopmental disorders33. ASD model mice exhibited significantly reduced 5-HT levels compared to controls34. Certain individuals with ASD exhibited notable symptom amelioration upon administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, potentially linked to serotonin level regulation35,36. It is also postulated by some researchers that maternal IL-6 may cross the immature fetal blood-brain barrier (BBB), triggering fetal IL-6 and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and elevated levels could further disrupt synaptic development and functionality37,38,39.

In addition to IL-6, interleukin-17A (IL-17A) may also impact neurodevelopment. Maternal immune activation and elevated IL-6 levels are shown to elevate IL-17A levels, which can traverse the placental barrier to reach fetal circulation40,41. IL-17A triggers excessive neutrophil activation, leading to the production and release of oxidative and inflammatory mediators that have the potential to disrupt the BBB, initiating neuroinflammatory responses in the brain42. Direct injection of IL-17A into fetal ventricles had been found to activate microglia and enhance their phagocytic activity, resulting in cortical developmental abnormalities and autism-like behaviors in offspring43. Conversely, injecting IL-17A antibodies into pregnant mothers to inhibit the IL-17A signaling pathway had shown partial improvement in autism-like behaviors in offspring44.

Offspring of mothers with asthma exhibit an elevated risk of developing asthma, indicating a potential genetic component in asthma susceptibility45. Strong associations are identified between asthma and ADHD throughout the genome, with multiple shared loci, including CISD246. The presence of CISD2 is closely linked to the proper functioning of mitochondria which play a crucial role in energy metabolism and the regulation of cellular homeostasis47,48,49,50,51. The absence of CISD2 can result in mitochondrial degeneration52. Mitochondrial dysfunction may impede oxidative phosphorylation, leading to inadequate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis53. Given the high energy demands of the developing brain, this deficiency can disrupt neural development54. Moreover, insufficient ATP impairs synthesis of glutathione, the principal intracellular redox buffer, thereby undermining antioxidant defenses and exacerbating oxidative‑stress–mediated mitochondrial and neuronal injury55,56,57. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a prevalent metabolic abnormality in individuals with ASD, suggesting a potential link to neurodevelopmental disorders58,59.

When considering maternal history of asthma, beyond the aforementioned genetic factors, long-term environmental risk factors warrant critical examination. Chronic exposure to air pollutants, particularly particulate matter less than 2.5 (PM2.5), is associated with elevated asthma prevalence60. Offspring may inherit not only genetic susceptibility but also shared environmental exposures. PM2.5 has been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction and compromise the BBB. Furthermore, PM2.5 exposure promotes systemic release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may traverse the disrupted BBB and impair neurodevelopment61,62. In cases of asthma during pregnancy, the intrauterine impact of pharmacological interventions cannot be overlooked. β₂-adrenergic receptor agonists, a mainstay of asthma management, were linked to increased ASD risk in offspring with prolonged in utero exposure compared to unexposed controls in a case-control study63. However, conflicting evidence exists, as other studies found no significant association between prenatal exposure to asthma medications and ASD/ADHD incidence12,64. Currently, no clear consensus exists regarding the intrauterine effects of gestational asthma medications; thus, further large-scale observational studies and controlled animal experiments are warranted to evaluate their specific impacts independent of maternal asthma pathophysiology. To delineate the etiological contributions of genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and pharmacological impacts on offspring ASD/ADHD risk, this study should conduct subgroup analyses comparing maternal history of asthma to asthma during pregnancy. Regrettably, the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria for maternal asthma across included studies rendered the planned subgroup analyses unfeasible.

Changes in the gut microbiota has been identified as a significant potential factor in neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. Maternal asthma may be associated with the composition of the maternal gut microbiome through the gut-lung axis65,66. Studies found that in asthma patients, not only was the microbial composition of the airways altered, but the gut microbiota was also affected, with a reduction in both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus levels67,68. Similarly, reduced levels of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus has been observed in children with ASD, with this anomaly being vertically transmitted from mother to offspring69,70,71. These alterations can compromise intestinal barrier integrity, allowing bacterial metabolites and inflammatory factors to enter systemic circulation and affect brain development. Bifidobacterium plays a role in regulating short-chain fatty acid levels, which can influence neurotransmitter synthesis71. Moreover, individuals diagnosed with ASD often experience gastrointestinal symptoms, suggesting a possible connection between neurodevelopmental disorders and the brain-gut axis72.

Subgroup analyses revealed a higher prevalence of ADHD in the maternal asthma group compared to the control asthma group for both male and female offspring. In the male subgroup, the prevalence of ASD was also higher in the offspring of mothers with asthma than in the control group, whereas no significant difference in ASD prevalence was observed between the two groups in the female subgroup. This disparity might be attributed to the limited number of studies and random variation, as the OR for this subgroup analysis was 1.81(95%CI = 0.72–4.25) based on only two studies. Additionally, diagnostic criteria for ASD are predominantly defined by male specimens, who typically exhibit more externalizing behaviors, while females tend to display internalizing symptoms that may resemble anxiety and depression, potentially leading to underdiagnosis compared to males73,74. The extreme male brain theory posits that elevated testosterone levels play a crucial role in the development of ASD75. Conversely, the female protective effect theory suggests that females may have higher genetic/mutational load76,77,78. Some researchers had posited that the Y chromosome could potentially serve as a risk factor for ASD, whereas the presence of the additional X chromosome in females might elevate the threshold for neurodevelopmental disorders79,80. These factors could elucidate the absence of a substantial correlation between maternal asthma and the risk of ASD in female progeny.

The foremost strength of this study lies in its distinction as the first meta-analysis investigating the association between maternal asthma and offspring risks of ASD/ADHD. The diagnosis of diseases is primarily based on standardized assessment tools and clinical evaluation, which enhances the credibility and accuracy of the findings. Furthermore, the studies incorporated in the analysis demonstrate high quality. This study also provides a multifaceted analysis of the underlying mechanisms, offering a comprehensive exploration from diverse perspectives. Nevertheless, limitations exist. A major limitation of this study is the failure to differentiate between maternal history of asthma and asthma during pregnancy, thereby precluding rigorous assessment of potential associations between genetic, long-term environmental risk, clinical management, and offspring ASD/ADHD risk. The meta-analysis is constrained by the limited number of studies included. Furthermore, the reliance on observational data from cohort and case-control studies may undermine the conclusion’s reliability for the lower levels of evidence inherent. The missing of some critical data remains a significant limitation of this study. Additionally, the use of diverse diagnostic tools across studies in the ASD and ADHD analyses contributed to high heterogeneity.

By demonstrating the association between maternal asthma and neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring, this study underscores the clinical imperative for early identification and screening of high-risk offspring, optimization of asthma management during pregnancy and targeted preventive strategies and surveillance for high-risk families, which may carry substantial clinical relevance.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis concludes that the maternal asthma is a risk factor for ASD/ADHD in offspring with the risk may being influenced by offspring sex.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ASD:

-

autism spectrum disorder

- ADHD:

-

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- 5-HT:

-

5-hydroxytryptamine

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- BBB:

-

blood-brain barrier

- IL-17A:

-

interleukin-17A

- ATP:

-

adenosine triphosphate

- PM2.5:

-

particulate matter less than 2.5

- No.:

-

number

- NA:

-

not available

- ADOS:

-

autism diagnostic observation schedule

- ADI-R:

-

autism diagnostic interview-revised

- DSM:

-

diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- ICD:

-

international classification of diseases;

- NDI:

-

neighborhood disadvantage index.

References

de Lima, T. A. et al. Differential diagnosis between autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disorders with emphasis on the preschool period. World J. Pediatr. 19, 715–726 (2023).

Han, V. X. et al. Maternal immune activation and neuroinflammation in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 564–579 (2021).

Holgate, S. T. Innate and adaptive immune responses in asthma. Nat. Med. 18, 673–683 (2012).

Croen, L. A. et al. Family history of immune conditions and autism spectrum and developmental disorders: Findings from the study to explore early development. Autism Res. 12, 123–135 (2019).

Schwartzer, J. J. et al. Behavioral impact of maternal allergic-asthma in two genetically distinct mouse strains. Brain Behav. Immun. 63, 99–107 (2017).

Tamayo, J. M. et al. The influence of asthma on neuroinflammation and neurodevelopment: From epidemiology to basic models. Brain Behav. Immun. 116, 218–228 (2024).

Tamayo, J. M. et al. Maternal allergic asthma induces prenatal neuroinflammation. Brain Sci. 12, 1041 (2022).

Hirota, T. & King, B. H. Autism spectrum disorder: A review. Jama 329, 157–168 (2023).

Salari, N. et al. The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 49, 48 (2023).

Croen, L. A. et al. Inflammatory conditions during pregnancy and risk of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open. Sci. 4, 39–50 (2024).

Croen, L. A. et al. Maternal autoimmune diseases, asthma and allergies, and childhood autism spectrum disorders: A case-control study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 159, 151–157 (2005).

Gong, T. et al. Parental asthma and risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring: A population and family-based case-control study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 49, 883–891 (2019).

Hisle-Gorman, E. et al. Prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal risk factors of autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr. Res. 84, 190–198 (2018).

Ho, Y. F. et al. Maternal asthma and asthma exacerbation during pregnancy and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A population-based cohort study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 33, 3841–3848 (2024).

Instanes, J. T. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring of mothers with inflammatory and immune system diseases. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 452–459 (2017).

Li, D. J. et al. Associations between allergic and autoimmune diseases with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder within families: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 19, 4503 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Parental asthma occurrence, exacerbations and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 82, 302–308 (2019).

Lyall, K. et al. Maternal immune-mediated conditions, autism spectrum disorders, and developmental delay. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 1546–1555 (2014).

Nielsen, T. C. et al. Association between cumulative maternal exposures related to inflammation and child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A cohort study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 38, 241–250 (2024).

Yu, X. et al. Prenatal air pollution, maternal immune activation, and autism spectrum disorder. Env. Int. 179, 108148 (2023).

Kliman, H. J. et al. Pathway of maternal serotonin to the human embryo and fetus. Endocrinology 159, 1609–1629 (2018).

Bijata, M. et al. Synaptic remodeling depends on signaling between serotonin receptors and the extracellular matrix. Cell Rep. 19, 1767–1782 (2017).

Migliarini, S. et al. Lack of brain serotonin affects postnatal development and serotonergic neuronal circuitry formation. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 1106–1118 (2013).

Sodhi, M. S. & Sanders-Bush, E. Serotonin and brain development. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 59, 111–174 (2004).

Chesné, J. et al. IL-17 in severe asthma. Where do we stand?. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 1094–1101 (2014).

Correia, A. S. & Vale, N. Tryptophan metabolism in depression: A narrative review with a focus on serotonin and kynurenine pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8493 (2022).

Erhardt, S. et al. The kynurenine pathway in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropharmacology 112, 297–306 (2017).

Marini, M. et al. Expression of the potent inflammatory cytokines, granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-6 and interleukin-8, in bronchial epithelial cells of patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 89, 1001–1009 (1992).

Ramírez, L. A. et al. A new theory of depression based on the serotonin/kynurenine relationship and the hypothalamicpituitary- adrenal axis. Biomedica 38, 437–450 (2018).

Teunis, C., Nieuwdorp, M. & Hanssen, N. Interactions between tryptophan metabolism, the gut microbiome and the immune system as potential drivers of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and metabolic diseases. Metabolites 12, 514 (2022).

Côté, F. et al. Maternal serotonin is crucial for murine embryonic development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 329–334 (2007).

Melnikova, V. et al. Prenatal stress modulates placental and fetal serotonin levels and determines behavior patterns in offspring of mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 13565 (2024).

Hanswijk, S. I. et al. Gestational factors throughout fetal neurodevelopment: The serotonin link. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5850 (2020).

Guo, Y. P. & Commons, K. G. Serotonin neuron abnormalities in the BTBR mouse model of autism. Autism Res. 10, 66–77 (2017).

Hollander, E. et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for repetitive behaviors and global severity in adult autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 292–299 (2012).

Williams, K. et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, Cd004677 (2013).

Banks, W. A., Kastin, A. J. & Broadwell, R. D. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation 2, 241–248 (1995).

Wei, H., Alberts, I. & Li, X. Brain IL-6 and autism. Neuroscience 252, 320–325 (2013).

Zawadzka, A., Cieślik, M. & Adamczyk, A. The role of maternal immune activation in the pathogenesis of autism: A review of the evidence, proposed mechanisms and implications for treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11516 (2021).

Fujitani, M. et al. Maternal and adult interleukin-17A exposure and autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 13, 836181 (2022).

Wong, H. & Hoeffer, C. Maternal IL-17A in autism. Exp. Neurol. 299, 228–240 (2018).

Nadeem, A. et al. Oxidative and inflammatory mediators are upregulated in neutrophils of autistic children: Role of IL-17A receptor signaling. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 90, 204–211 (2019).

Sasaki, T., Tome, S. & Takei, Y. Intraventricular IL-17A administration activates microglia and alters their localization in the mouse embryo cerebral cortex. Mol. Brain 13, 93 (2020).

Choi, G. B. et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 351, 933–939 (2016).

Lim, R. H., Kobzik, L. & Dahl, M. Risk for asthma in offspring of asthmatic mothers versus fathers: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 5, e10134 (2010).

Zhu, Z. et al. Shared genetics of asthma and mental health disorders: A large-scale genome-wide cross-trait analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 54, 1901507 (2019).

Bravo-Sagua, R. et al. Calcium transport and signaling in mitochondria. Compr. Physiol. 7, 623–634 (2017).

Cadenas, E. & Davies, K. J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 29, 222–230 (2000).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Cisd2 mediates mitochondrial integrity and life span in mammals. Autophagy 5, 1043–1045 (2009).

Gleichmann, M. & Mattson, M. P. Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1261–1273 (2011).

Jeong, S. Y. & Seol, D. W. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep. 41, 11–22 (2008).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Cisd2 deficiency drives premature aging and causes mitochondria-mediated defects in mice. Genes. Dev. 23, 1183–1194 (2009).

Citrigno, L. et al. The mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis in autism spectrum disorders: Current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5785 (2020).

Hall, C. N. et al. Oxidative phosphorylation, not glycolysis, powers presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms underlying brain information processing. J. Neurosci. 32, 8940–8951 (2012).

Frye, R. E. & James, S. J. Metabolic pathology of autism in relation to redox metabolism. Biomark. Med. 8, 321–330 (2014).

Manivasagam, T. et al. Role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in autism. Adv. Neurobiol. 24, 193–206 (2020).

Rose, S. et al. Mitochondrial and redox abnormalities in autism lymphoblastoid cells: a sibling control study. Faseb j. 31, 904–909 (2017).

Legido, A., Jethva, R. & Goldenthal, M. J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 20, 163–175 (2013).

Rossignol, D. A. & Frye, R. E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 290–314 (2012).

Chen, S. et al. Global associations between long-term exposure to PM(2.5) constituents and health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 474, 134715 (2024).

Li, K. et al. Early-life exposure to PM2.5 leads to ASD-like phenotype in male offspring rats through activation of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 274, 116222 (2024).

Shou, Y. et al. A review of the possible associations between ambient PM2.5 exposures and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 174, 344–352 (2019).

Croen, L. A. et al. Prenatal exposure to β2-adrenergic receptor agonists and risk of autism spectrum disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 3, 307–315 (2011).

Liang, H. et al. In utero exposure to β-2-adrenergic receptor agonist and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 847–856 (2017).

Aslam, R. et al. Link between gut microbiota dysbiosis and childhood asthma: Insights from a systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 3, 100289 (2024).

Hufnagl, K. et al. Dysbiosis of the gut and lung microbiome has a role in asthma. Semin. Immunopathol. 42, 75–93 (2020).

Marsland, B. J., Trompette, A. & Gollwitzer, E. S. The gut-lung axis in respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 12(Suppl 2), S150–S156 (2015).

Zimmermann, P. et al. Association between the intestinal microbiota and allergic sensitization, eczema, and asthma: A systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 467–485 (2019).

Iglesias-Vázquez, L. et al. Composition of gut microbiota in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 12, 792 (2020).

Iovene, M. R. et al. Intestinal dysbiosis and yeast isolation in stool of subjects with autism spectrum disorders. Mycopathologia 182, 349–363 (2017).

Rosenberg, E. & Zilber-Rosenberg, I. Reconstitution and transmission of gut microbiomes and their genes between generations. Microorganisms 10, 70 (2021).

Restrepo, B. et al. Developmental-behavioral profiles in children with autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring gastrointestinal symptoms. Autism Res. 13, 1778–1789 (2020).

Kallitsounaki, A. & Williams, D. M. Autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria/incongruence. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 3103–3117 (2023).

Pisula, E. et al. Behavioral and emotional problems in high-functioning girls and boys with autism spectrum disorders: Parents’ reports and adolescents’ self-reports. Autism 21, 738–748 (2017).

Li, M., Usui, N. & Shimada, S. Prenatal sex hormone exposure is associated with the development of autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2203 (2023).

Schumann, C. M. et al. Possible sexually dimorphic role of miRNA and other sncRNA in ASD brain. Mol. Autism 8, 4 (2017).

Werling, D. M. & Geschwind, D. H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 26, 146–153 (2013).

Xia, Y. et al. Transcriptomic sex differences in postmortem brain samples from patients with psychiatric disorders. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadh9974 (2024).

Berry, A. S. F. et al. A genome-first study of sex chromosome aneuploidies provides evidence of Y chromosome dosage effects on autism risk. Nat. Commun. 15, 8897 (2024).

Ferri, S. L., Abel, T. & Brodkin, E. S. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 20, 9 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author contributed significantly to the conception and development of the present paper. J.Z. and J.C. designed the research process, searched the database for corresponding articles and drafted the meta-analysis. Q.Z. and L.Y. extracted useful information from the articles above. H.H. and J.Y. used statistical software for analysis. Z.C. polished this article. All the authors had read and approved the manuscript and ensured that this was the case. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, as this study is a meta-analysis based on previously published data from global databases.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Chen, J., Zhang, Q. et al. Association between maternal asthma and ASD/ADHD in offspring: A meta-analysis based on observational studies. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 32 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00440-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00440-y