Abstract

Quantum dots in silicon are a promising architecture for semiconductor quantum computing due to a high degree of electric control and compatibility with existing silicon fabrication processes. Although electron charge and spin are prominent methods for encoding the qubit state, valley states in silicon can also store quantum information via valley-orbit coupling with protection against charge noise. By observing coherent oscillations between valley states in a Si/SiGe double quantum dot device tuned to the two-electron charge configuration, we measure the valley energy splitting in both quantum dots individually. We further demonstrate two-axis quantum control of the valley qubit using gated pulse sequences with X and Z rotations occurring within a fast operation time of 300 ps. This control is used to completely map out the surface of the Bloch sphere in a single phase-space plot that is subsequently used for state and process tomography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum dots are a leading architecture for scalable quantum computing in silicon.1,2,3,4,5 While electrons in quantum dots can often be approximated as particles in potential wells, the electronic band structure cannot be ignored. In particular, the low-lying valley states in silicon greatly affect electron physics in silicon-based heterostructures.6,7 In the case of Si/SiGe quantum dots, the energy splitting between out-of-plane valley states can be suppressed in the presence of disorder at the Si/SiGe interface.8,9,10,11 For electron charge- and spin-based qubit implementations, an excited valley state that is nearly degenerate with the ground state represents an unwanted avenue for quantum information loss.12,13,14 On the other hand, the valley states have properties that could be exploited to form a qubit basis with several desirable traits. First, such a valley qubit can be electrically manipulated and measured through valley-orbit coupling with no need for a magnetic field gradient.15,16,17 Second, since there exists a broad window of quantum dot gate voltages that do not impact the valley splitting, a valley-encoded qubit would have protection against charge noise, the leading source of decoherence in charge and spin qubits.18,19 Finally, gate operation times are determined by the valley splitting, which can be on the order of 10 GHz.20,21 In this article, we demonstrate quantum control of a valley qubit in a Si/SiGe double quantum dot by mapping out the surface of the Bloch sphere with sub-nanosecond gate operations. To benchmark the valley qubit performance, we perform quantum process tomography on rotations about the z axis and measure gate fidelities of 79–93%.

Results

Device characterization

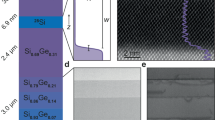

Experiments were performed on an accumulation-mode double quantum dot fabricated on a high-mobility Si/SiGe wafer (Fig. 1a). Two dots are formed in the lower current channel where voltages applied to the five local gates control dot energies and coupling strengths. The left (right) dot energy can be tuned with the application of voltage to the plunger gate VL (VR), and the inter-dot coupling is controlled by barrier gate M. Dot charge sensing is achieved by passing a current through the upper channel that contains a gate-defined single-electron transistor (SET). Peaks in QPC transconductance correspond to electrons hopping in or out of either dot, and the sign of each peak indicates whether or not the charge transition occurred in the left dot (positive) or the right dot (negative). Here we focus on the (1,1) ↔ (2,0) charge transition as the qubit operation point; in other words, there is one electron in the left dot and a second is allowed to tunnel between dots (Fig. 1b). This transition yielded the best operation, although valley oscillations were also seen at the (1,0) ↔ (0,1) transition in an earlier work.20

Device structure and coherent valley oscillations. a Scanning electron micrograph of the double QD device used in this study, before deposition of the top gate. b Charge stability diagram as a function of plunger voltages, measured by QPC transconductance, in the operation region. Indices (i, j) indicate electron occupation in the left and right dots. Arrows represent the general starting points and pulse directions used to drive valley precession. c Oscillations of 5.5 GHz between left dot valley states when pulsing from (1,1) to (2,0). d Oscillations of 7.8 GHz between right dot valley states when pulsing from (2,0) to (1,1)

Coherent valley oscillations

To observe coherent valley oscillations in the left dot, the system is initialized in the (1,1) charge configuration corresponding to the right dot ground state |Rv1〉. Then a trapezoidal voltage pulse with ~200 ps rise time is applied simultaneously to VL and VR (with opposite polarities) to modify the system detuning \({\it{\epsilon }} \equiv V_{\mathrm{R}} - V_{\mathrm{L}}\), or the relative energy of the two quantum dots. The ramp rate is slow enough that there are no transitions to excited states for all detunings \({\it{\epsilon }} \;<\; 0\). As the detuning is increased to positive values, there is an anticrossing between the lowest two levels at \({\it{\epsilon }} \approx 0\). Here the state experiences a Landau-Zener transition into a superposition of the two lowest energy states, each state itself a superposition of all four charge-valley states, with state coefficients determined by the pulse ramp rate.22 Due to valley-orbit coupling, the state evolves smoothly into a superposition of the two left dot valley levels \(\psi = 1/\sqrt 2 \left( {\left| {L_{{\mathrm{v}}1}} \right\rangle + e^{i\phi }\left| {L_{{\mathrm{v}}2}} \right\rangle } \right)\) as the detuning is further increased. When the pulse reaches its maximum detuning, the state undergoes Larmor precession between the left dot valley states with a frequency determined by the valley splitting. As the pulse returns to the initialization point, the left dot valley state phase difference ϕ is mapped to charge states |Lv1〉 and |Rv1〉 to facilitate quantum state readout with the charge sensor. The measured current oscillations as a result of the operation, averaged over roughly 5 × 106 pulse realizations for each pulse width tp, reflect a changing ϕ between valley states (Fig. 1c). This pulse technique is also used to probe the right dot valley states by initializing in the left dot and pulsing to negative detuning (Fig. 1d). A lower bound for the coherence time \(T_2^ \ast\) can be obtained from the characteristic decay time of the oscillations, which for large pulse heights is found to be over 7 ns (Fig. 1c). This value is a significant improvement over standard charge qubit coherence times and comparable to that of hybrid qubits,23 and can be attributed to the charge noise protection afforded by valley states.

It is useful to stress that projective read-out of the valley states only relies upon the dot occupation. In Fig. 1c, following phase accumulation at the height of the pulse, the system is brought back to negative detunings where the states |Lv1〉 and |Lv2〉 evolve smoothly to charge occupation states |Rv1〉 and |Lv1〉, respectively (see Fig. 2c). Thus, the relatively small valley splitting is transformed into a large energy difference that is readily measured by charge sensing on the right dot. The presence of an electron in the right dot immediately after the pulse implies that the qubit was in the lower valley state, while the absence of an electron in the right dot indicates that the qubit was in the upper valley state. While the valley splitting can be modified by spin states when a quantum dot contains multiple electrons, the charge-based read-out sensitivity is not affected.

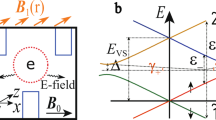

Ramsey spectroscopy of the (1,1) → (2,0) transition. a Precession between the ground and first excited states of the system, induced by a 3-stage Ramsey pulse, as a function of middle-stage pulse width tp and pulse height \({\it{\epsilon }}_p\). b Fourier transform of a and a fit to a four-state model (overlaid dots). Error bars are obtained from the root mean squared error of the fit. c Reconstructed energy levels as a function of detuning using the fit from b. The calculated Hamiltonian matrix elements are Δ1 = 1.8 GHz, Δ2 = 12.7 GHz, Δ3 = 15.6 GHz, and Δ4 = 2.0 GHz, as well as valley splittings δL = 4.55 GHz and δR = 15.74 GHz (see methods for model Hamiltonian). Inset: the pulse form, measured on an oscilloscope, of a typical Ramsey pulse

Ramsey spectroscopy

The full four-state Hamiltonian (consisting of two charge states, each with two valley states) can be reconstructed with Ramsey spectroscopy.24 For this experiment, pulses are only applied to VR; additionally, the voltage on the right barrier gate BR was decreased to reduce tunneling from (1,1) to (1,0). Changing the QD tuning inevitably changes the static dot locations in the device as well as the valley splitting, so we expect to see modified valley oscillation frequencies. The voltage pulse begins as before with a ramp to a sufficiently positive detuning point, chosen to yield the highest visibility valley oscillations when performing a trapezoidal pulse. As a result of the first pulse stage, the qubit state has been transformed into \(\left| { - y} \right\rangle = \left( {\left| {L_{{\mathrm{v}}1}} \right\rangle - i\left| {L_{{\mathrm{v}}2}} \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\). In the middle stage of the operation, the detuning is brought to an arbitrary point \({\it{\epsilon }}_p\) where the state is allowed to precess for time tp. Finally the state is brought back to the positive detuning point and then to the initialization point \({\it{\epsilon }}_0\) for readout. This pulse scheme allows for high-visibility precession between the two lowest lying energy levels (Fig. 2a), and the frequency of precession can be directly converted into an energy gap. All four energy levels can be determined by plotting the energy gap as a function of \({\it{\epsilon }}_{\mathrm{p}}\) (Fig. 2b). Left- and right-dot valley splittings δL = 4.55 GHz and δR = 15.7 GHz were extracted with this procedure. Important for high-coherence quantum control, the two low-energy states have a “sweet spot” at the anticrossing \({\it{\epsilon }} = 20\,{\mathrm{\mu eV}}\) where the system is first-order insensitive to charge noise, as well as two “extended sweet spots” at large positive and negative detunings where the valley splittings become largely independent of gate voltage (Fig. 2c). This result emphasizes that the valley splitting varies from dot to dot. In six devices with identical geometry, fabricated on HRL epi-wafers, the splitting ranged from 10 μeV to 60 μeV. Additionally, local confinement gate voltages can modify the splitting by up to 20% in these devices.

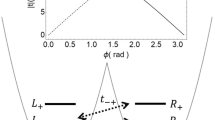

Fast two-axis control

Two-axis quantum control of the valley qubit was implemented on the left dot valley states, using a fast three-stage DC-gated pulse scheme23 (Fig. 3c). After initialization into |Rv1〉 at \({\it{\epsilon }}_0\), the first stage of the pulse brings the detuning to the anticrossing at \({\it{\epsilon }}_x\). The effective two-state Hamiltonian at \({\it{\epsilon }}_x\) is 2Δ1σx and the qubit state will precess between the left and right dot ground states for the duration of the pulse stage, tθ. On the Bloch sphere in the charge basis, this corresponds to rotations of the qubit state about the x axis with polar angle given by θ = 2Δ1tθ/ℏ in the diabatic limit. In the second pulse stage, the detuning is brought to point \({\it{\epsilon }}_z\) and held for time tϕ. During this time the state will precess about the z axis of the Bloch sphere in the valley basis, with azimuthal angle given by ϕ = δLtϕ/ℏ. The last stage of the pulse brings the detuning back to \({\it{\epsilon }}_x\) for a time tθ, equal to that of the first pulse stage. Similar to the first pulse stage, this operation performs x-axis rotations and maps the phase ϕ of the valley qubit state to charge states that can be read out at \({\it{\epsilon }}_0\). Since the 200 ps pulse rise time is not fast compared to the state evolution in this stage, the rotations actually occur about an axis that makes an angle α ≈ π/4 with the x axis in the x–z plane (Fig. 3e). By fixing operation points \({\it{\epsilon }}_x\) and \({\it{\epsilon }}_z\) and varying the time spent at those points during the pulse sequence, the qubit state is swept over the entire surface of the Bloch sphere (Fig. 3a, b). This method of complete quantum control has been achieved optically in self-assembled InGaAs quantum dots,25 and has not yet been demonstrated in gate-defined semiconductor quantum dots. In Fig. 3a, holding tθ fixed at 0.22 ns and varying tϕ represents Z rotations after an X rotation of 3π/2. Naturally, since the rotation about x brings the qubit state to the Bloch sphere equator, subsequent Z rotations have maximum amplitude (Fig. 4d, red line). Similarly, at time tθ = 0.5 ns the qubit state is rotated to back to state |+z〉 = |Lv1〉 at the north pole of the Bloch sphere, where Z rotations have a minimal effect on the state (Fig. 4d, blue line). The X and Z rotations have frequencies of 2.5 GHz and 4.6 GHz, respectively, which agree with the qubit energy splitting at the operation points. Since operations take place in “sweet spots”, the detrimental effects of charge noise on coherence are minimized.

Quantum control of the valley qubit. a, b Measured and simulated oscillations with a dynamical projection axis determined by tθ, demonstrating a complete map of the Bloch sphere surface. Independent oscillations as functions of pulse widths are visible with frequencies of 4.6 GHz and 2.5 GHz. A linear background is subtracted from the data. c Pulse form used for two-axis state rotations. Pulse heights are fixed at \({\it{\epsilon }}_x\) and \({\it{\epsilon }}_z\) and the pulse widths tθ and tϕ are varied. d Theoretical prediction of the measured probability |−z〉|U(θ, ϕ)|z〉|2 with U(θ, ϕ) given by the product of Eqs (1–3). See Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2 for more details. e A schematic of the three pulse stages. In stage 1 (blue), the state is rotated about x by angle θ. In stage 2 (red), the state is rotated about z by angle ϕ, and in stage 3 (cyan) the state is rotated about a tilted axis by angle θ', where θ' = θ by design

State tomography of Z rotations. a–c Red dots represent state projections when the qubit is initialized in state |−y〉 (θ = π/2), and blue dots indicate an initial state of |+z〉 (θ = 2π). Data is extracted from Fig. 3a and solid traces are fits to a decaying exponential with a 4.6 GHz frequency. d Normalized trajectories of the qubit state on the Bloch sphere during Z rotations, using the fits from state tomography

It is important to emphasize that the mapping from valley phase to charge configuration in Fig. 3a is dependent on tθ. The operation performed on the qubit state in stage i of the pulse can be written as a unitary transformation given by

where θ and ϕ are polar and azimuthal angles on the Bloch sphere, σi are Pauli matrices, and α = π/4 in Eq. (3) is the angle the stage 3 rotation axis makes with the x axis. Using these expressions, the measured projection after the pulse can be written as 〈−z|U(θ, ϕ)|z〉, where U(θ, ϕ) = U3(θ)U2(ϕ)U1(θ). The corresponding probability of finding the qubit to be in the excited valley state is sinusoidal in ϕ, and oscillations vanish when θ is an even multiple of π, in good agreement with the data. The model is further improved by adding rotation axis deviations in pulse stages 1 and 2 of π/10 and π/30 (Fig. 3d). As a result, each trace at fixed ϕ represents projective measurements of a state with initialization determined by tθ, measured along an axis also set by tθ.

Valley qubit operation fidelities

Fidelities of qubit operations can be computed with quantum process tomography (QPT).26 True QPT would entail initializing into four linearly independent basis states and separately measuring the x, y, and z projections of the final state after a gate operation. Although the information given by our dynamical projection approach does not constitute a complete set of state tomography, a less rigorous calculation of QPT can be obtained by matching the data with the theoretical model in Fig. 3d and then reconstructing the qubit state from the measured probabilities accordingly (Fig. 4). For instance, at θ = π/2 the y projection is being measured while at θ = 3π/2 the x projection is probed. Missing components, like the x and y projections of the qubit state when initialized in state |+z〉 = |Lv1〉, are approximated from traces where oscillations are minimized at θ = 2π and 4π. Due to the heavily suppressed tunneling rate from (1,1) to (1,0), we further assume that electrons do not tunnel out of the dots during qubit operations, which allows us to map the upper and lower limits of the measured transconductance directly to the probability of the qubit to be in state |−z〉. Since Z rotation processes take place at large values of detuning, they offer a metric for the degree of charge noise protection the valley states have to offer; accordingly, we are most interested in the fidelities of Z rotations (Fig. 5). Comparisons between calculated process matrices χ from QPT with those associated with perfectly executed operations χideal show good qualitative agreement.

Quantum process tomography for valley (Z) rotations. a, c, e Measured process matrices based on a fit of state tomography data. The color of each matrix element bar denotes complex phase: blue is real, red is imaginary. b, d, f Ideal process matrices for comparison. Calculated fidelities \(\cal{F} = \mathrm{Tr}( \chi _{\mathrm{ideal}}\chi)\) are \({\cal{F}}_{\pi /2} = 0.85 \pm 0.02\), \({\cal{F}}_{\pi} = 0.79 \pm 0.02\), and \({\cal{F}}_{2\pi } = 0.93 \pm 0.01\)

Discussion

Quantitatively, the gate fidelities defined as \(\cal{F} = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\chi _{{\mathrm{ideal}}}\chi } \right)\) for π/2, π, and 2π rotations are respectively 85%, 79%, and 93%. The decreases in fidelity of the smaller rotations when compared to the full 2π rotation can be understood by the trajectory of the qubit state. From state tomography, it is clear that the actual rotation axis is tilted away from the z axis by about 10 degrees. The identity (2π) process matrix is insensitive to the choice of rotation axis, whereas the NOT (π) process matrix is maximally sensitive. Since the fidelity of the 2π process is greater than the fidelities of the smaller rotations, this suggests that the fidelity is limited by rotation axis errors and not by decoherence. See Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3 for a more detailed discussion on error sources. Attenuation and pulse-shaping considerations may be able to alleviate this effect in future work, although a crucial variable that controls decoherence and rotation axis error is the choice of operation point \({\it{\epsilon }}_z\). Analysis of the energy level diagram suggests that the energy splitting is still slowly converging in the region of \({\it{\epsilon }}_z\), leading to a nonzero first-order sensitivity to charge noise as well as a non-negligible charge coupling that contributes to the undesired rotation axis tilt. This conclusion is further supported by the measured coherence time during Z rotations of 1.5 ns, smaller than the value of \(T_2^ \ast\) obtained from trapezoidal pulse experiments and much smaller than typical valley relaxation times.27 Pulsing further into the region of detuning-invariant energy splitting would certainly lead to improved gate fidelities and coherence times.

In summary, we have shown that a semiconductor qubit formed from valley states in silicon can be electrically controlled to perform independent rotations about two orthogonal axes. Sub-nanosecond operation times, determined by valley splitting, range from 200 ps to 300 ps. Although the performance of this particular valley qubit is inferior to the similarly operated hybrid qubit system in terms of coherence times,28 proper pulse engineering and readout can in principle lead to fidelities greater than 90% at multiple charge configurations. This work explores the utility of valley degrees of freedom as alternatives to electron charge and spin for storing and manipulating quantum information in silicon, and further investigates methods for limiting charge noise-induced decoherence.

Methods

Sample preparation

From top to bottom, the semiconductor wafer layers are a 2 nm silicon cap, a 30–50 nm SiGe spacer, and a 10 nm silicon quantum well, grown on a SiGe graded buffer on a silicon wafer. A peak mobility of 7 × 105 cm2/V s and electron density of 4 × 1011 cm−2 was measured on a separately fabricated Hall bar. Device depletion gates were fabricated through e-beam evaporation of Ti/Au, followed by atomic layer deposition of 100 nm Al2O3. An aluminum global top gate was evaporated above the insulating layer. Ohmic contacts to the quantum well were made by phosphorous ion implantation.

Measurement

All measurements were performed in a dilution refrigerator operating at a base temperature of 36 mK. Voltage pulses were generated by an Agilent 81134 A pulse generator with a repetition rate of 7.5 MHz and applied to gate VR. The signal-to-noise ratio of charge sensing was improved by applying a sinusoidal dithering voltage to the plunger gates and reading the modulated QPC signal with a lock-in amplifier (Stanford Research Systems 830).

Theory

Energy levels of the four-state system were calculated assuming a Hamiltonian in the charge basis {|Rv1〉, |Rv2〉, |Lv1〉, |Lv2〉} of the form

The energy difference between the lowest two eigenstates of Eq. (4) as a function of detuning was solved analytically and the Ramsey spectroscopy data was fit to the energy difference expression to obtain values for matrix elements δL, δR, and Δi.

Numerical simulations of the qubit response to detuning pulses were obtained with the master equation that relates the system density matrix ρ to the Hamiltonian in Eq. (4):

After the pulse, the system was allowed to evolve freely at \({\it{\epsilon }} = {\it{\epsilon }}_0\) for 2 ns, and time-averaged values of density matrix elements were obtained over the last 2 ns to reproduce the inherent time averaging of the charge sensor measurement. Decoherence due to charge noise was included in the simulations. The probability of the qubit to be in state |Lv2〉 is obtained from ρ and calibrated to the recorded current so that the amplitude of the decaying oscillations is equal to 0.5 at t = 0.

Quantum process tomography

The system density matrix was constructed from the results of state tomography (Fig. 4a–c). The y and z projections of the qubit state were directly obtained from Fig. 3a, and the x projection was inferred by subtracting a phase of π/2 from the y projection. Quantum process tomography requires four linearly independent input states, which we chose to be |Lv1〉, |Lv2〉, |x〉 and |y〉.26 The output state that results from a quantum process on any input state ρ is given by

where χmn is the process matrix and Am is a vector containing the basis for density matrix operators. The elements of χ are solved using maximum likelihood estimation in a form that ensures χmn is positive and Hermitian.29 As an initial guess, χmn is solved by linear inversion of Eq. (6).30 To obtain error bars for process fidelities, we perform QPT at different reference times during rotations and calculate the standard deviation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computing with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120–126 (1998).

Petersson, K. D., Petta, J. R., Lu, H. & Gossard, A. C. Quantum coherence in a one-electron semiconductor charge qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 246804 (2010).

Veldhorst, M. et al. A two-qubit logic gate in silicon. Nature 526, 410–414 (2015).

Watson, T. F. et al. A programmable two-qubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature 555, 633–637 (2018).

Jock, R. M. et al. A silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor electron spin-orbit qubit. Nat. Commun. 9, 1768 (2018).

Hanson, R., Kouwenhoven, L. P., Petta, J. R., Tarucha, S. & Vandersypen, L. M. Spins in few-electron quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 1217–1265 (2007).

Zwanenburg, F. A. et al. Silicon quantum electronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 961–1019 (2013).

Schaffler, F. High-mobility Si and Ge structures. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 12, 1515 (1997).

Friesen, M., Eriksson, M. A. & Coppersmith, S. N. Magnetic field dependence of valley splitting in realistic Si/SiGe quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 202106 (2006).

Friesen, M., Chutia, S., Tahan, C. & Coppersmith, S. N. Valley splitting theory of SiGe/Si/SiGe quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 75, 115318 (2007).

Culcer, D., Hu, X. & Sarma, S. D. Interface roughness, valley-orbit coupling, and valley manipulation in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 82, 205315 (2010).

Goswami, S. et al. Controllable valley splitting in silicon quantum devices. Nat. Phys. 3, 41–45 (2007).

Yang, C. H. et al. Spin-valley lifetimes in a silicon quantum dot with tunable valley splitting. Nat. Commun. 4, 2069 (2013).

Zhang, L., Luo, J.-W., Saraiva, A., Koiller, B. & Zunger, A. Genetic design of enhanced valley splitting towards a spin qubit in silicon. Nat. Comm. 4, 2396 (2013).

Friesen, M. & Coppersmith, S. N. Theory of valley-orbit coupling in a Si/SiGe quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 81, 115324 (2010).

Gamble, J. K., Eriksson, M. A., Coppersmith, S. N. & Friesen, M. Disorder-induced valley-orbit hybrid states in Si quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035310 (2013).

Veldhorst, M. et al. Spin-orbit coupling and operation of multivalley spin qubits. Phys. Rev. B 92, 201401(R) (2015).

Culcer, D., Saraiva, A. L., Koiller, B., Hu, X. & Sarma, S. D. Valley-based noise-resistant quantum computing using Si quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 126804 (2012).

Mi, X., Kohler, S. & Petta, J. R. Landau-Zener interferometry of valley-orbit states in Si/SiGe double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 98, 161404(R) (2018).

Schoenfield, J. S., Freeman, B. M. & Jiang, H. Coherent manipulation of valley states at multiple charge configurations of a silicon quantum dot device. Nat. Commun. 8, 64 (2017).

Mi, X., Peterfalvi, C. G., Burkard, G. & Petta, J. R. High-resolution valley spectroscopy of Si quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 176803 (2017).

Petta, J. R., Lu, H. & Gossard, A. C. A coherent beam splitter for electronic spin states. Science 327, 669–672 (2010).

Kim, D. et al. Quantum control and process tomography of a semiconductor quantum dot hybrid qubit. Nature 511, 70–74 (2014).

Shi, Z. et al. Fast coherent manipulation of three-electron states in a double quantum dot. Nat. Commun. 5, 3020 (2014).

Press, D., Ladd, T. D., Zhang, B. & Yamamoto, Y. Complete quantum control of a single quantum dot spin using ultrafast optical pulses. Nature 456, 218–221 (2008).

Chow, J. M. et al. Randomized benchmarking and process tomography for gate errors in a solid-state qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 090502 (2009).

Kawakami, E. et al. Electrical control of a long-lived spin qubit in a Si/SiGe quantum dot. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 666–670 (2014).

Kim, D. et al. High-fidelity resonant gating of a silicon-based quantum dot hybrid qubit. npj Quant. Inform. 1, 15004 (2015).

James, D. F., Kwiat, P. G., Munro, W. J. & White, A. G. Measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052312 (2001).

Childs, A. M., Chuang, I. L. & Leung, D. W. Realization of quantum process tomography in NMR. Phys. Rev. A 64, 012314 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jason Petta of Princeton University and Nathan Bishop of the Laboratory for Physical Sciences at the University of Maryland for supplying the semiconductor qubit community with standardized epitaxial wafers. N.E.P. acknowledges support from the Julian Schwinger graduate fellowship. This work was supported by U.S. ARO through Grant. No. W911NF1410346.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.E.P. and H.W.J. performed measurements. N.E.P. carried out simulations and data analysis with assistance from J.D.R. L.F.E. grew the Si/SiGe wafer. J.S.S. fabricated the device. H.W.J. supervised the project. N.E.P. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Penthorn, N.E., Schoenfield, J.S., Rooney, J.D. et al. Two-axis quantum control of a fast valley qubit in silicon. npj Quantum Inf 5, 94 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0212-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0212-5

This article is cited by

-

Universal quantum control of an atomic spin qubit on a surface

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Review of performance metrics of spin qubits in gated semiconducting nanostructures

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

-

Silicon-based qubit technology: progress and future prospects

Bulletin of Materials Science (2022)

-

Semiconductor qubits in practice

Nature Reviews Physics (2021)

-

Fast spin-valley-based quantum gates in Si with micromagnets

npj Quantum Information (2021)