Abstract

One of the goals of science is to understand the relation between a whole and its parts, as exemplified by the problem of certifying the entanglement of a system from the knowledge of its reduced states. Here, we focus on a different but related question: can a collection of marginal information reveal new marginal information? We answer this affirmatively and show that (non-) entangled marginal states may exhibit (meta)transitivity of entanglement, i.e., implying that a different target marginal must be entangled. By showing that the global n-qubit state compatible with certain two-qubit marginals in a tree form is unique, we prove that transitivity exists for a system involving an arbitrarily large number of qubits. We also completely characterize—in the sense of providing both the necessary and sufficient conditions—when (meta)transitivity can occur in a tripartite scenario when the two-qudit marginals given are either the Werner states or the isotropic states. Our numerical results suggest that in the tripartite scenario, entanglement transitivity is generic among the marginals derived from pure states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entanglement1 is a characteristic of quantum theory that profoundly distinguishes it from classical physics. The modern perspective considers entanglement as a resource for information processing tasks, such as quantum computation2,3,4,5,6, quantum simulation7, and quantum metrology8. With the huge effort devoted to scaling up quantum technologies9, considerable attention has been given to the study of quantum many-body systems10,11, specifically the ability to prepare and manipulate large-scale entanglement in various experimental systems.

As the number of parameters to be estimated is huge, entanglement detection via the so-called state tomography is often impractical. Indeed, significant efforts have been made for detecting entanglement in many-body systems10,11 using limited marginal information. For example, some tackle the problem using properties of the reduced states12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, while others exploit directly the data from local measurements24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Despite their differences, they can all be seen as some kind of entanglement marginal problem (EMP)36, where the entanglement of the global system is to be deduced from some (partial knowledge of the) reduced states.

The entanglement of the global system, nonetheless, is not always the desired quality of interest. For instance, in scaling up a quantum computer, one may wish to verify that a specific subset of qubits indeed get entangled, but this generally does not follow from the entanglement of the global state (recall, e.g., the Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger states37). Thus, one requires a more general version of the problem: Given certain reduced states, can we certify the entanglement in some other target (marginal) state? We call this the entanglement transitivity problem (ETP). Since the global system is a legitimate target system, ETPs include the EMP as a special case.

As a concrete example beyond EMPs, one may wonder whether a set of entangled marginals are sufficient to guarantee the entanglement of some other target subsystems. If so, inspired by the work38 on nonlocality transitivity of post-quantum correlations39, we say that such marginals exhibit entanglement transitivity. Indeed, one of the motivations for considering entanglement transitivity is that it is a prerequisite for the nonlocality transitivity of quantum correlations, a problem that has, to our knowledge, remained open.

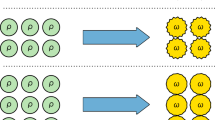

More generally, one may also wonder whether separable marginals alone, or with some entangled marginals could imply the entanglement of other marginal(s). To distinguish this from the above phenomenon, we say that such marginals exhibit metatransitivity. Note that any instance of metatransitivity with only separable marginals represents a positive answer to the EMP. Here, we show that examples of both types of transitivity can indeed be found. Moreover, we completely characterize when two Werner-state40 marginals and two isotropic-state41 marginals may exhibit (meta)transitivity.

Results

Formulation of the entanglement transitivity problems

Let us first stress that in an ETP, the set of given reduced states must be compatible, i.e., giving a positive answer to the quantum marginal problem42,43. With some thought, one realizes that the simplest nontrivial ETP involves a three-qubit system where two of the two-qubit marginals are provided. Then, the problem of deciding if the remaining two-qubit marginal can be separable is an ETP different from EMPs.

More generally, for any n-partite system S, an instance of the ETP is defined by specifying a set \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}=\{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}:i=1,2,\ldots ,k\}\) of k marginal systems Si (each in its respective state \({\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\)) and a target system \({{{\rm{T}}}}\,\notin\, {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\). Here, \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) is a strict subset of all the 2n possible combinations of at most n subsystems, i.e., k < 2n. Then, \({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}:=\{{\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\}\) exhibits entanglement (meta)transitivity in T if for all joint states ρS compatible with σ, the reduced state ρT is always entangled while (not) all given \({\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\) are entangled. Formally, the compatible requirement reads as: \({{{{\rm{tr}}}}}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}\backslash {{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}({\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}})={\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\) for all \({{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}\in {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) where S\Si denotes the complement of Si in the global system S.

Notice that for the problem to be nontrivial, there must be (1) some overlap among the subsystems specified by Si’s, as well as with T, and (2) the global system S cannot be a member of \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\). However, the target system T may be chosen to be S and if all \({\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\) are separable, we recover the EMP36 (see also refs. 19,23 for some strengthened version of the EMP). Hereafter, we focus on ETPs beyond EMPs, albeit some of the discussions below may also find applications in EMPs.

Certification of (meta)transitivity by a linear witness

Let \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}(\rho )\) be an entanglement witness26, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}(\rho )\,\ge \,0\) for all separable states in T, and \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}(\rho ) \,<\, 0\) for some entangled states. We can certify the (meta)transitivity of \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) in T if a negative optimal value is obtained for the following optimization problem:

where \({{{\rm{tr}}}}({\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}})=1\) is implied by the compatibility requirement and “ ≽ ” denotes matrix positivity. Then, \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}\) detects the entanglement in T from the given marginals in \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\).

Consider now a linear entanglement witness, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}({\rho }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}})={{{\rm{tr}}}}\left[{\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}({W}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\otimes {{\mathbb{I}}}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}\backslash {{{\rm{T}}}}})\right]\) for some Hermitian operator WT, where \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}={{{{\rm{tr}}}}}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}\backslash {{{\rm{T}}}}}({\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}})\) is the reduced state of ρ in T. In this case, Eq. (1) is a semidefinite program44. Interestingly, its dual problem44 can be seen as the problem of minimizing the total interaction energies among the subsystems Si while ensuring that the global Hamiltonian is non-negative, see Supplementary Note 1.

Hereafter, we focus, for simplicity, on T being a two-body system. Then, a convenient witness is that due to the positive-partial-transpose (PPT) criterion45,46, with \({W}_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}={\eta }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{{{\Gamma }}}\), where ηT ≽ 0 and Γ denotes the partial transposition operation. Further minimizing the optimum value of Eq. (1) over all ηT such that \({{{\rm{tr}}}}({\eta }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}})=1\) gives an optimum λ* that is provably the smallest eigenvalue of all compatible \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{{{\Gamma }}}\) (see Supplementary Note 1). Hence, λ* < 0 is a sufficient condition for witnessing the entanglement (meta)transitivity of the given σ in T.

Three remarks are now in order. Firstly, the ETP defined above is straightforwardly generalized to include multiple target systems {Tj: j = 1, …, t} with \({{{{\rm{T}}}}}_{j}\,\notin\, {{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) for all j. A certification of the joint (meta)transitivity is then achieved by certifying each Tj separately. Secondly, other entanglement witnesses26 may be considered. For instance, to certify the entanglement of a two-body ρT that is PPT47, a witness based on the computable cross-norm/ realignment (CCNR) criterion48,49,50,51, may be employed. Finally, for a multipartite target system, a witness tailored for detecting the genuine multipartite entanglement in ρT (see, e.g., Refs. 14,16) is surely of interest.

A family of transitivity examples with n qubits

As a first illustration, let \(\left|{{{\Psi }}}^{+}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|10\right\rangle +\left|01\right\rangle )\) and consider:

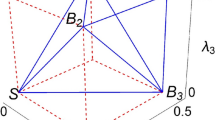

which is a two-qubit reduced state of \({{{\Omega }}}_{n}(\gamma )=\gamma \left|{W}_{n}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {W}_{n}\right|+(1-\gamma )\left|{0}^{n}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {0}^{n}\right|\), i.e., a mixture of \(\left|{0}^{n}\right\rangle\) and an n-qubit W state \(\left|{W}_{n}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{n}\left|{1}_{j}\right\rangle\), where 1j denotes an n-bit string with a 1 in position j and 0 elsewhere. Now, imagine drawing these n qubits as vertices of a tree graph52 with (n − 1) edges, see Fig. 1, such that every edge corresponds to a pair of qubits in the state ρn(γ), that is,

where \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) represents the set of edges. Then we prove the following result:

Theorem 1

For any tree graph with n vertices that satisfies Eq. (3), \({{{\Omega }}}_{n}(\gamma )=\gamma \left|{W}_{n}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {W}_{n}\right|+(1-\gamma )\left|{0}^{n}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {0}^{n}\right|\) is the unique global state and all the two-qubit reduced states are ρn(γ).

The details of its proof can be found in Supplementary Notes 2. Thus, these ρn(γ) exhibit transitivity for any of the \(\frac{(n-1)(n-2)}{2}\) pairs of qubits that are not linked by an edge. Indeed, the symmetry of Ωn(γ) implies that all its two-qubit marginals are ρn(γ), and the smallest eigenvalue of ρn(γ)Γ is \({\lambda }^{* }=\frac{(n-2\gamma )-\sqrt{{(n-2\gamma )}^{2}+4{\gamma }^{2}}}{2n} \,<\, 0\) for γ ∈ (0, 1].

We should clarify that the transitivity exhibited by ρn(γ) requires a tree graph only in that it represents the minimal amount of marginal information for the global state to be uniquely determined. Any other n-vertex graph with equivalent marginal information or more leads to the same conclusion.

These examples involve only entangled marginals. Next, we present examples where some of the given marginals are separable. In particular, we provide a complete solution of the ETPs with the input marginals being a Werner state40 or an isotropic state41.

Metatransitivity from Werner state marginals

A Werner state40 Wd(v) is a two-qudit density operator invariant under arbitrary U ⊗ U unitary transformations, where U belongs to the set of d-dimensional unitaries \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{d}\) for finite d. Let \({P}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{d}({P}_{{{{\rm{as}}}}}^{d})\) be the projection onto the symmetric (antisymmetric) subspace of \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\). Then we can write qudit Werner states as the one-parameter family40

Consider a pair of Werner states σ = {Wd(vAB), Wd(vAC)} that are the marginals of some joint state ρABC. Then the Werner-twirled state53 \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}=\int d{\mu }_{U}(U\otimes U\otimes U){\rho }_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}{(U\otimes U\otimes U)}^{{\dagger} }\), where μU is a uniform Haar measure over \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{d}\), is trivially verified to be a valid joint state for these marginals. Moreover, \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\) has a Werner state Wd(vBC) as its BC marginal.

Importantly, the aforementioned twirling bringing ρABC to \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\) is achievable by local operations and classical communications (LOCC). Since LOCC cannot create entanglement from none, if the BC marginal \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}\) of \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\) is entangled, so must the BC marginal ρBC of ρABC. Conversely, since \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\) is a legitimate joint state of the given marginals σ, if \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}\) is separable, by definition, the given marginals σ cannot exhibit transitivity. Without loss of generality, we may thus restrict our attention to a Werner-twirled joint state \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\). Then, since a Werner state Wd(v) is entangled if and only if (iff)40 \(v\in [0,\frac{1}{2})\), combinations of Werner state marginals Wd(vAB) and Wd(vAC) leading to \({\widetilde{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}={W}_{d}({v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}})\) with \({v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}} \,<\, \frac{1}{2}\) must exhibit entanglement (meta)transitivity.

Next, let us recall from Ref. 54 the following characterization: three Werner states with parameters \(\overrightarrow{v}=({v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}},{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}},{v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}})\) are compatible iff the vector \(\overrightarrow{v}\) lies within the bicone given by \(f(\overrightarrow{v})\,\ge \,g(\overrightarrow{v})\) and \(3-f(\overrightarrow{v})\,\ge \,g(\overrightarrow{v})\), where \(f(\overrightarrow{v})={v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}+{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}+{v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}\) and \(g(\overrightarrow{v})=\sqrt{3{({v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}-{v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}})}^{2}+{(2{v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}-{v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}-{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}})}^{2}}\). To find the (meta)transitivity region for (vAB, vAC), it suffices to determine the boundary where the largest compatible \({v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}=\frac{1}{2}\). These boundaries are found (see Supplementary Note 3) to be the two parabolas \({({v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}-{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}-\frac{1}{2})}^{2}=2(1-{v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}})\) and \({({v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}+{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}-\frac{1}{2})}^{2}=4{v}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}{v}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}\), mirrored along the line vAB + vAC = 1, as shown in Fig. 2. It also shows the compatible regions of (vAB, vAC) obtained directly from Ref. 54, and the desired (shaded) regions exhibiting the (meta)transitivity of these marginals. In particular, the lower-left region corresponds to (a) while the top-left and bottom-right regions correspond to (b) in Fig. 4. Remarkably, these results hold for arbitrary Hilbert space dimension d ≥ 2 (but for d = 2, the lower-left shaded region does not correspond to compatible Werner marginals).

For d ≥ 3 the compatible region for the pair is enclosed by the solid red line, but for d = 2 it is restricted to the portion above the dotted line. The blue curves (being parts of two parabolas) describe boundaries where the largest compatible vBC is \(\frac{1}{2}\). Regions exhibiting (meta)transitivity are shaded in (gray) cyan.

Metatransitivity from isotropic state marginals

An isotropic state41 is a bipartite density operator in \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\) that is invariant under \(U\otimes \overline{U}\) (or \(\overline{U}\otimes U\)) transformations for any unitary \(U\in {{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{d}\); here, \(\overline{U}\) is the complex conjugation of U. We can write qudit isotropic states as a one-parameter family41

where \(\left|{{{\Phi }}}_{d}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{d}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 0}^{d-1}\left|j\right\rangle \left|j\right\rangle\) and p gives the fully entangled fraction55,56 of \({{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{d}(p)\).

Consider now a pair of isotropic marginals \({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}=\{{{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{d}({p}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}),{{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}_{d}({p}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}})\}\) as the reduced states of some joint state τABC. Then the “twirled” state \({\widetilde{\tau }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}=\int d{\mu }_{U}(\overline{U}\otimes U\otimes U){\tau }_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}{(\overline{U}\otimes U\otimes U)}^{{\dagger} }\), which has a Werner state marginal Wd(vBC) in BC, is easily verified to be a valid joint state for the given marginals. As in the case of given Werner states marginals, it suffices to consider \({\widetilde{\tau }}_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}\) in determining the region of (pAB, pAC) that demonstrates metatransitivity.

To this end, note that two isotropic states and one Werner state with parameters \(\overrightarrow{p}=({p}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}},{p}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}},{v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}})\) are compatible iff54 the vector \(\overrightarrow{p}\) lies within the convex hull of the origin \({\overrightarrow{p}}_{0}=(0,0,0)\) and the cone given by \({\alpha }_{+}\,\le \,1+\frac{1}{d}(\beta +1)\) and \(d{\alpha }_{+}-\beta \,\ge \,d\sqrt{{\left({\alpha }_{+}+\beta \right)}^{2}+\left(\frac{d+1}{d-1}\right){\alpha }_{-}}\), where α± = pAB ± pAC and β = 2(vBC − 1). To find the metatransitivity region for (pAB, pAC) we again look for the boundary where the largest compatible \({v}_{{{{\rm{BC}}}}}=\frac{1}{2}\), which we show in Supplementary Note 4 to be \(4{p}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}{p}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}={({p}_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}+{p}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}-1+\frac{1}{d})}^{2}\). The resulting regions of interest are illustrated for the d = 3 case in Fig. 3, and they correspond to (b) in Fig. 4.

The compatible region for the pair is enclosed by the solid red line. The blue curves (shown for the case of d = 3) marks the boundary where the largest compatible vBC is \(\frac{1}{2}\). Regions exhibiting metatransitivity are shaded in gray, which shrink with increasing d, as the upper red curve flattens towards the dashed black line and the blue curves approach the two axes.

Metatransitivity with only separable marginals

Curiously, none of the infinitely compatible pairs of marginals given above result in the most exotic type of metatransitivity, even though there are known examples where separable marginals imply a global entangled state (see, e.g., refs. 12,24,25,36). In the following, we provide examples where the entanglement of a subsystem is implied by only separable marginals. This already occurs in the simplest case of a three-qubit system. Consider the rank-two mixed state \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{ABC}}}}}=\frac{1}{4}\left|{\chi }_{1}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {\chi }_{1}\right|+\frac{3}{4}\left|{\chi }_{2}\right\rangle \,\left\langle {\chi }_{2}\right|\) where

It can be easily checked that the AB and BC marginals of χABC are PPT, which suffices46 to guarantee their separability, while Eq. (1) with the PPT criterion can be used to confirm that AC is always entangled. Thus, this example corresponds to (c) in Fig. 4. Likewise, examples exhibiting different kinds of transitivity can also found in higher dimensions (with bound entanglement47) or with more subsystems, see Supplementary Note 5 for details.

Here, we present one such example to illustrate some of the subtleties of ETPs in a scenario involving more than three subsystems. Consider the four-qubit pure state

One can readily check that its AB, BC, and CD marginals are PPT and are thus separable. At the same time, one can verify using Eq. (1) with the PPT criterion that these three marginals together imply the entanglement of all the three remaining two-qubit marginals. Thus, this corresponds to (d) in Fig. 4.

At this point, one may think that the entanglement in the AC marginal already follows from the given AB and BC marginals, analogous to the tripartite examples presented above. This is misguided: the CD marginal is essential to force the AC marginal to be entangled. Similarly, the AB marginal is indispensable to guarantee the entanglement of BD. Thus, the current metatransitivity example illustrates a genuine four-party effect that cannot exist in any tripartite scenario. For completeness, an example exhibiting the same four-party effect but where all input two-qubit marginals are entangled is also provided in Supplementary Note 5.

Metatransitivity from marginals of random pure states

Naturally, one may wonder how common the phenomena of (meta)transitivity is. Our numerical results based on pure states randomly generated according to the Haar measure suggest that transitivity is generic in the tripartite scenario: for local dimension up to five, all sampled pure states have only non-PPT marginals and demonstrate entanglement transitivity. However, with more subsystems, (meta)transitivity seems rare. For example, among the 105 sampled four-qubit states, only about 7.32% show transitivity while about 3.38% show metatransitivity. For a system with even more subsystems or with a higher d, we do not find any example of (meta)transitivity from random sampling (see Table 1 for details).

Next, notice that for the convenience of verification, some explicit examples that we provide actually involve marginals leading to a unique global state. However, uniqueness is not a priori required for entanglement (meta)transitivity. For example, among those quadripartite (meta)transitivity examples found for randomly sampled pure states, >73% of them (see Supplementary Note 5) are not uniquely determined from three of its two-qubit marginals (cf. refs. 57,58,59). In contrast, most of the tripartite numerical examples found appear to be uniquely determined by two of their two-qudit marginals, a fact that may be of independent interest (see, e.g., refs. 60,61,62,63).

Discussion

The example involving noisy W-state marginals demonstrate that the transitivity can occur for arbitarily long chain of quantum systems. This leads us to consider metatransitivity with only separable marginals. Beyond the example given above, we present also in Supplementary Note 5 a five-qubit example with four separable marginals and discuss some possibility to extend the chain. For future work, it could be interesting to determine if such exotic metatransitivity examples exist at the two ends of an arbitrarily long chain of multipartite system. For the closely related EMP, we remind that an explicit construction for a state with only two-body separable marginals and an arbitrarily large number of subsystems is known23 (see also ref. 36).

So far, we have discussed only cases where both the input marginals and the target marginal are for two-body subsystems. If entanglement can be deduced from two-body marginals, it is also deducible from higher-order marginals that include the former from coarse graining. Hence, the consideration of two-body input marginals allows us to focus on the crux of the ETP. As for the target system, we provide—as an illustration—in Supplementary Note 5 an example where the three two-qubit marginals of Fig. 1(b) imply the genuine three-qubit entanglement present in BCD. Evidently, there are many other possibilities to be considered in the future, as entanglement in a multipartite setting is known1,26 to be far richer.

Our metatransitivity examples also illustrate the disparity between the local compatibility of probability distributions and quantum states. Classically, probability distributions P(A, B) and P(B, C) compatible in P(B) always have a joint distribution P(A, B, C) (this extends to the multipartite case for marginal distributions that form a tree graph64). One may think that the quantum analogue of this is: compatible ρAB and ρBC must imply a separable joint state, and hence a separable ρAC. However, our metatransitivity example (as with nontrivial instances of tripartite EMPs), illustrates that this generalization does not hold. Rather, as we show in Supplementary Note 8, a possible generalization is given by classical-quantum states ρAB and ρBC sharing the same diagonal state in B—in this case, metatransitivity can never be established.

Evidently, there are many other possible research directions that one may take from here. For example, as with the W-states, we have also observed transitivity in n ≤ 3 ≤ d ≤ 6 for qudit Dicke states65,66,67, which seems to be also uniquely determined by its (n − 1) bipartite marginals. To our knowledge, this uniqueness remains an open problem and, if proven, may allow us to establish examples of transitivity for an arbitrarily high-dimensional quantum state that involves an arbitrary number of particles. From an experimental viewpoint, the construction of witnesses specifically catered for ETPs are surely welcome.

Finally, notice that while ETPs include EMPs as a special case, an ETP may be seen as an instance of the more general resource transitivity problem (CYH, GNT, YCL), where one wishes to certify the resourceful nature of some subsystem based on the information of other subsystems. In turn, the latter can be seen as a special case of the even more general resource marginal problems68, where resource theories are naturally incorporated with the marginal problems of quantum states.

Methods

Metatransitivity certified using separability criteria

As mentioned before, we can certify the entanglement (meta)transitivity of a given set of marginals in a bipartite target system T by demonstrating the violation of the PPT separability criterion. We can show this by solving the following convex optimization problem:

which directly optimizes over the joint state ρS with marginals \({\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\) such that the smallest eigenvalue λ of \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{{{\Gamma }}}\) is maximized. Because a bipartite state that is not PPT is entangled45,46, if the optimal λ (denoted by λ⋆ throughout) is negative, the marginal state in T of all possible joint states ρS must be entangled.

In the Supplementary Notes, we compute the Lagrange dual problem to Eq. (1) with a linear witness WT. A similar calculation for Eq. (8) shows that it is equivalent to a dual problem with \(W={\eta }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}}^{{{\Gamma }}}\), where ηT being an additional optimization variable subjected to the constraint of ηT ≽ 0 and \({{{\rm{tr}}}}({\eta }_{{{{\rm{T}}}}})=1\).

Meanwhile, to certify genuine tripartite entanglement in the target tripartite marginal T, we use a simple criterion introduced in ref. 69. Consider the density operator ρAB on \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{m}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{n}\) to be an m × m block matrix of n × n matrices ρ(i, j). Let \(\widetilde{{\rho }_{AB}}\) denote the realigned matrix obtained by transforming each block ρ(i, j) into rows. The CCNR criterion48,49 dictates that for separable σAB, \(\parallel \widetilde{{\sigma }_{{{{\rm{AB}}}}}}{\parallel }_{1}\le 1\).

Now, let A∣BC denote a bipartition of a tripartite system ABC into a bipartite system with parts A and BC. Finally, for any tripartite state ρABC on \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{d}\), define

where TX means a partial transposition with respect to the subsystem X. It was shown in ref. 69 that for any biseparable ρABC, we must have

This means that if any of M(ρABC), N(ρABC) is larger than \(\frac{1+2d}{3}\), ρABC must be genuinely tripartite entangled.

Therefore in the metatransitivity problem, we can use this, cf. Eq. (8) for the bipartite target system, for detecting genuine tripartite entanglement. This is done by minimizing M and N of the target marginal and taking the larger of the two minima. To this end, note that the minimization of the trace norm can be cast as an SDP70. Further details can be found in Supplementary Notes 1.

Certifying the uniqueness of a global compatible (pure) state

A handy way of certifying the (meta)transitivity of marginals \(\{{\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{i}}\}\) known to be compatible with some pure state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is to show that the global state ρS compatible with these marginals is unique, i.e., ρS is necessarily \(\left|\psi \right\rangle \,\left\langle \psi \right|\). This can be achieved by solving the following SDP:

The objective function here is the fidelity of ρS with respect to the pure state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\). If this minimum is 1, then by the property of the Uhlmann-Jozsa fidelity71, we know that the only compatible ρS is indeed given by \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\!\left\langle \psi \right|\).

For the numerical results that show how typical transitivity is for the bipartite marginals of a pure global state, the marginals are obtained from a uniform random n-qudit state, which is obtained by taking the first column of a dn-dimensional Haar-random unitary.

Data availability

All relevant data supporting the main conclusions and figures of the document are available upon reasonable request. Please refer to Gelo Noel Tabia at gelonoel-tabia@gs.ncku.edu.tw.

Code availability

Code for generating the numerical results are available upon reasonable request. Please refer to Gelo Noel Tabia at gelonoel-tabia@gs.ncku.edu.tw.

References

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865–942 (2009).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Jozsa, R. & Linden, N. On the role of entanglement in quantum-computational speed-up. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 459, 2011–2032 (2003).

Vidal, G. Efficient classical simulation of slightly entangled quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 147902 (2003).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

McArdle, S., Endo, S., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Benjamin, S. C. & Yuan, X. Quantum computational chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015003 (2020).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Pezzè, L., Smerzi, A., Oberthaler, M. K., Schmied, R. & Treutlein, P. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

Ladd, T. D. et al. Quantum computers. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010).

De Chiara, G. & Sanpera, A. Genuine quantum correlations in quantum many-body systems: a review of recent progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 074002 (2018).

Cirac, J. I. Entanglement in many-body quantum systems. Man.-Body Phys. Ultracold Gases: Lect. Notes Les. Houches Summer Sch.: Vol. 94, July 2010 94, 161 (2012).

Tóth, G. Entanglement witnesses in spin models. Phys. Rev. A 71, 010301 (2005).

Navascués, M., Owari, M. & Plenio, M. B. Power of symmetric extensions for entanglement detection. Phys. Rev. A 80, 052306 (2009).

Jungnitsch, B., Moroder, T. & Gühne, O. Taming multiparticle entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 190502 (2011).

Sawicki, A., Oszmaniec, M. & Kuś, M. Critical sets of the total variance can detect all stochastic local operations and classical communication classes of multiparticle entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 86, 040304 (2012).

Sperling, J. & Vogel, W. Multipartite entanglement witnesses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 110503 (2013).

Walter, M., Doran, B., Gross, D. & Christandl, M. Entanglement polytopes: Multiparticle entanglement from single-particle information. Science 340, 1205–1208 (2013).

Chen, L., Gittsovich, O., Modi, K. & Piani, M. Role of correlations in the two-body-marginal problem. Phys. Rev. A 90, 042314 (2014).

Miklin, N., Moroder, T. & Gühne, O. Multiparticle entanglement as an emergent phenomenon. Phys. Rev. A 93, 020104(R) (2016).

Bohnet-Waldraff, F., Braun, D. & Giraud, O. Entanglement and the truncated moment problem. Phys. Rev. A 96, 032312 (2017).

Harrow, A. W., Natarajan, A. & Wu, X. An improved semidefinite programming hierarchy for testing entanglement. Commun. Math. Phys. 352, 881–904 (2017).

Gerke, S., Vogel, W. & Sperling, J. Numerical construction of multipartite entanglement witnesses. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031047 (2018).

Paraschiv, M., Miklin, N., Moroder, T. & Gühne, O. Proving genuine multiparticle entanglement from separable nearest-neighbor marginals. Phys. Rev. A 98, 062102 (2018).

Tóth, G., Knapp, C., Gühne, O. & Briegel, H. J. Optimal spin squeezing inequalities detect bound entanglement in spin models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 250405 (2007).

Tóth, G., Knapp, C., Gühne, O. & Briegel, H. J. Spin squeezing and entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 79, 042334 (2009).

Gühne, O. & Tóth, G. Entanglement detection. Phys. Rep. 474, 1–75 (2009).

Gittsovich, O., Hyllus, P. & Gühne, O. Multiparticle covariance matrices and the impossibility of detecting graph-state entanglement with two-particle correlations. Phys. Rev. A 82, 032306 (2010).

de Vicente, J. I. & Huber, M. Multipartite entanglement detection from correlation tensors. Phys. Rev. A 84, 062306 (2011).

Bancal, J.-D., Gisin, N., Liang, Y.-C. & Pironio, S. Device-independent witnesses of genuine multipartite entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 250404 (2011).

Li, M., Wang, J., Fei, S.-M. & Li-Jost, X. Quantum separability criteria for arbitrary-dimensional multipartite states. Phys. Rev. A 89, 022325 (2014).

Liang, Y.-C. et al. Family of bell-like inequalities as device-independent witnesses for entanglement depth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 190401 (2015).

Baccari, F., Cavalcanti, D., Wittek, P. & Acín, A. Efficient device-independent entanglement detection for multipartite systems. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021042 (2017).

Lu, H. et al. Entanglement structure: entanglement partitioning in multipartite systems and its experimental detection using optimizable witnesses. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021072 (2018).

Frérot, I. & Roscilde, T. Optimal entanglement witnesses: a scalable data-driven approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 040401 (2021).

Frérot, I., Baccari, F. & Acín, A. Unveiling quantum entanglement in many-body systems from partial information. PRX Quantum 3, 010342 (2022).

Navascués, M., Baccari, F. & Acín, A. Entanglement marginal problems. Quantum 5, 589 (2021).

Greenberger, D. M., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Zeilinger, A. Bell’s theorem without inequalities. Am. J. Phys. 58, 1131–1143 (1990).

Coretti, S., Hänggi, E. & Wolf, S. Nonlocality is transitive. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100402 (2011).

Popescu, S. & Rohrlich, D. Quantum nonlocality as an axiom. Found. Phys. 24, 379–385 (1994).

Werner, R. F. Quantum states with Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen correlations admitting a hidden-variable model. Phys. Rev. A 40, 4277–4281 (1989).

Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, P. Reduction criterion of separability and limits for a class of distillation protocols. Phys. Rev. A 59, 4206–4216 (1999).

Klyachko, A. A. Quantum marginal problem and N-representability. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 36, 72–86 (2006).

Tyc, T. & Vlach, J. Quantum marginal problems. Eur. Phys. J. D. 69, 209 (2015).

Boyd, S. & Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Peres, A. Separability criterion for density matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1413–1415 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states: necessary and sufficient conditions. Phys. Lett. A 223, 1–8 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Mixed-state entanglement and distillation: is there a "Bound” entanglement in nature? Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5239–5242 (1998).

Rudolph, O. Further results on the cross norm criterion for separability. Quantum Inf. Process. 4, 219–239 (2005).

Chen, K. & Wu, L.-A. A matrix realignment method for recognizing entanglement. Quantum Info Comput. 3, 193–202 (2003).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed quantum states: linear contractions and permutation criteria. Open Syst. Inf. Dyn. 13, 103–111 (2006).

Shang, J., Asadian, A., Zhu, H. & Gühne, O. Enhanced entanglement criterion via symmetric informationally complete measurements. Phys. Rev. A 98, 022309 (2018).

Bender, E. A. & Williamson, S. G. Lists, Decisions and Graphs, 171 (UC San Diego, 2010).

Eggeling, T. & Werner, R. F. Separability properties of tripartite states with U⨂U⨂U symmetry. Phys. Rev. A 63, 042111 (2001).

Johnson, P. D. & Viola, L. Compatible quantum correlations: Extension problems for werner and isotropic states. Phys. Rev. A 88, 032323 (2013).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. General teleportation channel, singlet fraction, and quasidistillation. Phys. Rev. A 60, 1888–1898 (1999).

Albeverio, S., Fei, S.-M. & Yang, W.-L. Optimal teleportation based on bell measurements. Phys. Rev. A 66, 012301 (2002).

Jones, N. S. & Linden, N. Parts of quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 71, 012324 (2005).

Huber, F. & Gühne, O. Characterizing ground and thermal states of few-body hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 010403 (2016).

Wyderka, N., Huber, F. & Gühne, O. Almost all four-particle pure states are determined by their two-body marginals. Phys. Rev. A 96, 010102(R) (2017).

Linden, N., Popescu, S. & Wootters, W. K. Almost every pure state of three qubits is completely determined by its two-particle reduced density matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 207901 (2002).

Linden, N. & Wootters, W. K. The parts determine the whole in a generic pure quantum state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 277906 (2002).

Diósi, L. Three-party pure quantum states are determined by two two-party reduced states. Phys. Rev. A 70, 010302(R) (2004).

Han, Y.-J., Zhang, Y.-S. & Guo, G.-C. Compatibility relations between the two-party reduced and global tripartite density matrices. Phys. Rev. A 72, 054302 (2005).

Wolf, M. M., Verstraete, F. & Cirac, J. I. Entanglement and frustration in ordered systems. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 01, 465–477 (2003).

Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 93, 99–110 (1954).

Wei, T.-C. & Goldbart, P. M. Geometric measure of entanglement and applications to bipartite and multipartite quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 68, 042307 (2003).

Aloy, A., Fadel, M. & Tura, J. The quantum marginal problem for symmetric states: applications to variational optimization, nonlocality and self-testing. N. J. Phys. 23, 033026 (2021).

Hsieh, C.-Y., Tabia, G. N. M., Yin, Y.-C. & Liang, Y.-C. Resource marginal problems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.03523 (2022).

Li, M., Wang, J., Shen, S., Chen, Z. & Fei, S.-M. Detection and measure of genuine tripartite entanglement with partial transposition and realignment of density matrices. Sci. Rep. 7, 17274 (2017).

Ben-Tal, A. & Nemirovskii, A. Lectures on Modern Convex Optimization: Analysis, Algorithms, and Engineering Applications. MPS-SIAM series on optimization (SIAM, 2001).

Liang, Y.-C. et al. Quantum fidelity measures for mixed states. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 076001 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Antonio Acín and Otfried Gühne for their helpful comments. CYH is supported by ICFOstepstone (the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Co-fund GA665884), the Spanish MINECO (Severo Ochoa SEV-2015-0522), the Government of Spain (FIS2020-TRANQI and Severo Ochoa CEX2019-000910-S), Fundació Cellex, Fundació Mir-Puig, Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR1381 and CERCA Programme), the ERC AdG CERQUTE, and the AXA Chair in Quantum Information Science. We also acknowledge support from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grants Nos. 107-2112-M-006-005-MY2, 109-2627-M-006-004, 109-2112-M-006-010-MY3), and the National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.N.T., C.Y.H., and Y.C.L. formulated the problem and developed the theoretical ideas. G.N.T., Y.C.L., and Y.C.Y. carried out the numerical calculations. All explicit examples are due to G.N.T. and K.S.C. G.N.T. and Y.C.L. prepared the manuscript with help from K.S.C. and C.Y.H. All authors were involved in the discussion and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabia, G.N.M., Chen, KS., Hsieh, CY. et al. Entanglement transitivity problems. npj Quantum Inf 8, 98 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00616-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00616-1