Abstract

A common wisdom posits that transport of conserved quantities across clean nonintegrable quantum systems at high temperatures is diffusive when probed from the emergent hydrodynamic regime. We show that this empirical paradigm may alter if the strong interaction limit is taken. Using Krylov-typicality and purification matrix-product-state methods, we establish in short-to-intermediate time scales the following observations for the nonintegrable lattice model imitating the experimental Rydberg blockade simulator. Given the strict projection owing to the infinite density-density repulsion V, the Rydberg chain’s energy transport in the presence of a transverse field g is tentatively superdiffusive at infinite temperature featured by an anomalous scaling exponent \(\frac{3}{4}\), indicating the potential existence of a novel dynamical universality class. Imposing, in addition, a growing longitudinal field h causes a putative superdiffusion-to-ballistic transport transition at h ≈ g. Interestingly, all the above results persist for large but finite interactions and temperatures, provided that the strongly interacting condition g, h ≪ kBT ≪ V is fulfilled. Our predictions are testable by current Rydberg quantum simulation facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In quantum dynamics, states of matter can be classified by their universal transport properties, e.g., normal diffusion for nonintegrable systems and ballistic propagation for integrable models1,2,3. In this regard, one question central to nonequilibrium many-body physics, quantum simulation, and statistical mechanics concerns violations or modifications to this standard paradigm stemming from the interplay among distinct energy scales of the problem. For closed setups, there are three such quantities, free and interaction parts of the Hamiltonian and temperature. Most previous literature focused on the influence of moderate interactions on system’s low-temperature transport behaviors4,5. Intriguingly, a recent advance in this context takes a different angle that leads to the finding of Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ)6 spin superdiffusion at infinite temperature in integrable Heisenberg chain with a fine-tuned non-Abelian symmetry7,8,9,10,11. It is noteworthy that here temperature sets the maximum scale, far beyond the scale of the Hamiltonian12,13.

In this work, we consider scenario where the interaction part of the Hamiltonian Hint is first taken to infinity and the subsequent measurements and evaluations are then performed in the infinite-temperature limit while the free part of the Hamiltonian H0 is maintained as the reference point. Physically, such an arrangement corresponds to the strongly interacting condition, \(\frac{{H}_{0}}{L}\ll {k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\ll \frac{{H}_{{\rm{int}}}}{L}\). Here we are chiefly inspired by recent progress on Rydberg blockade experiments14, where the above construction appears to be achievable. Anomalous energy transport in clean Rydberg blockade chain, as will be reported in detail in current work, was first hinted in refs. 15,16 where we extensively discussed randomness-induced dynamical effects in Rydberg array when subject to this strong interaction limit.

Results

Clean constrained model

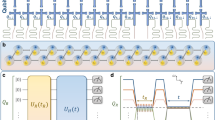

Neutral atoms in optical tweezers with large principal quantum numbers can be photon driven into Rydberg qubits. The generated van der Waals interactions entangle atoms within a blockade sphere, accommodating no more than one Rydberg excitation. Lasers are used to address individual atoms for the onsite qubit operations. Under the correspondence \({b}_{i}^{\dagger }+{b}_{i}={\sigma }_{i}^{x},{b}_{i}^{\dagger }{b}_{i}={n}_{i}=\frac{1}{2}(1-{\sigma }_{i}^{z})\) upon basis \(\left\vert \,\text{g}\,\right\rangle =\left\vert \uparrow \right\rangle ,\left\vert \,\text{r}\,\right\rangle =\left\vert \downarrow \right\rangle\), one canonical hard-core boson model realizable in such Rydberg analog simulators with the nearest-neighbor density-density interaction imitates the nonintegrable quantum spin chain model in the transverse and longitudinal fields14,17,18,19,

where Rydberg blockade means V = ∞, then specifically the constrained model20 reads

with projector P = ∏i(1 − nini+1), thereby preventing two simultaneous excitations for any pair of adjacent atoms21. Rabi frequency and detuning of the coherent laser beam are designated by uniform transverse and longitudinal field strengths g and h, respectively. Throughout this paper, we use hard-core boson and spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) representations interchangeably in the chain model with fixed open boundary conditions, choose g = 1 as the energy unit, and keep ℏ = kB = a = 1.

To highlight the novelty of model (2), we perform a comparative study by contrasting \(\tilde{H}\) with two variants of the blockade model in the literature. For later reference, the first22 is given by

where \({\tilde{X}}_{i}=P({b}_{i}^{\dagger }+{b}_{i})P,{\tilde{Z}}_{i}=P(1-2{n}_{i})P\), and local projector Pi = 1 − ni. While, the second23 is given by

We will proceed in three successive steps to furnish the comparison, from the static spectral and entanglement diagnostics to the dynamic distinctions in energy transport.

Static diagnostics

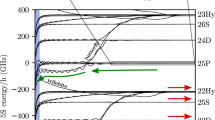

Time-reversal symmetry is preserved in all above four models. For generic nonzero parameters, clean mixed-field spin chain including particularly its infinitely interacting variant \(\tilde{H}\)19 is anticipated to obey eigenstate thermalization hypothesis (ETH)24,25 whose eigenspectrum shall be describable by Gaussian orthogonal ensemble (GOE)26. Using exact diagonalization, we scrutinize spectral properties of model (2) via its level statistics. The level-spacing ratio is defined by \({r}_{n}=\frac{\min \{{\delta }_{n},{\delta }_{n-1}\}}{\max \{{\delta }_{n},{\delta }_{n-1}\}}\) whose mean r ≈ 0.53 if GOE is assumed where δn = En − En−1 with {En} an ascending set of all available eigenvalues27.

Figure 1a shows the scaling of the evolution of r under the increase of h for \(\tilde{H}\). By exploiting reflection symmetry, we pick the odd-parity sector of \(\tilde{H}\) and push the maximum size to L = 29. (Even-parity results are similar.) The calculated spectral statistics exhibit several peculiarities. (i) Within 0 ⩽ h ≲ 1 (relative sign between g, h is immaterial), the system’s energy-level distribution rapidly converges upward and saturates at GOE. (ii) Beyond h ≳ 1.5, this upward trend is more visible as indicated by the vertical up arrow, but longer chains are entailed here to witness the full convergence toward GOE further. (iii) In between, these two GOE plateaus are separated by a sudden dip where r deviates from 0.53 appreciably, signaling a transition between these two thermal regions. As illustrated by the inset of Fig. 1a, the companion finite-size data collapse of r supports the finding of the transition where a critical h ≈ 1.17 can be identified.

a Scaling of mean level-spacing ratio r as a function of h in odd-parity sector of clean open Rydberg blockade chain [model (2)] up to maximum length L = 29. The inset illustrates accompanying data collapse after adjusting horizontal axis to (h − 1.17)L1.8 while maintaining vertical axis to r. b, c r as a function of \(h_{P} (h_{XZ})\) for odd-parity sector of model (3) [(4)]. d Energy transport of model (4) at hXZ = 0.024 [see definition (5) and Fig. 3 below].

Importantly, striking evidence on the transition in \(\tilde{H}\) can be gained from the contrast between r-evolutions in \(\tilde{H}\) and \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\). We repeat the same spectral analysis on \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) in Fig. 1b. As marked there by the right arrow, the saturation process for the r-values of \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) toward GOE is dominated by a trend shifting horizontally to greater values of hP upon increasing L. This continuous move hints that unlike the two thermal phases in \(\tilde{H}\), for \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) there only exists one thermal phase at finite hP28. Despite the fact that models (2) and (3) resemble each other and share the same approximate symmetry in large-h and -hP limits (see below), their Hilbert-space structures are fundamentally different. Our intent is to reveal that \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) is conventional, but \(\tilde{H}\) is highly unconventional. Below, this distinction is cemented further in their dynamics of energy transport.

Incidentally, Khemani et al.23 and Ljubotina et al.22 argued that the h = 0 point of \(\tilde{H}\) (also called the PXP model known to be robustly nonintegrable) is governed by an unknown near-integrability described by \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) with tiny hXZ. We disagree with this claim by showing in Fig. 1c, d that both the spectral and transport properties of \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) with small hXZ are the same as that in the h = 0 point of \(\tilde{H}\). No signature of near-integrability survives in moderate sizes19. (By contrast, Fig. 4 in ref. 22 suggested that at hXZ = 0.024, the energy transport of \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) was ballistic.) From esthetic viewpoint, we advocate that the h = 0 point of \(\tilde{H}\) itself represents the new dynamical universality class that deserves more future investigations.

We continue to investigate the energy-resolved entanglement entropy for the entirety of eigenstates of model (2) versus (3). For each eigenfunction with eigenenergy E, we compute its half-chain von Neumann entropy \({S}_{{\rm{vN}}}=-\,\text{Tr}\,{\rho }_{R}{\log }_{2}{\rho }_{R}\) via reduced density matrix ρR by tracing out degrees of freedom on left half-chain and plot SvN as a function of E.

Figure 2 depicts the qualitative similarity between the spectral parsings of SvN for \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) across regions of small to large values of h, hP. As shown by Fig. 2a, b, e, for thermal phases at small 0 ⩽ h, hP < 1, the entanglement data tend to form a single, smoothing curve following ETH29,30. Figure 2c, d, f, g demonstrates that once h, hP exceed 1, this tendency alters and the whole Hilbert spaces of \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) factorize into smaller subsectors, each resembling the lineshapes of Fig. 2a, b, e but with negligible interference19.

For every eigenstate, a point is drawn whose coordinates are marked by its eigenenergy and entanglement entropy. a–d correspond to h = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5 for \(\tilde{H}\). e–g correspond to hP = 0.5, 1, 1.5 for \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) [Pi∓1 in (3) induce more visible subsectors in f and g].

These subsectors emerging once h, hP ≳ 1 can be roughly tagged by the total number of bosons Nb = ∑ini in the chain. There exist \(\frac{L}{2}\) such groups of subsectors corresponding to \(\frac{L}{2}\) possible values of Nb for a chain of length L under reflection symmetry19. Hence, \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) share exactly the same Nb-symmetry in the infinite-h, hP limits. [Notice that the exact integrable point at infinite h or hP is trivial. It is easy to see that rather than ballistic transport, there is no transport at this integrable (solvable) point.] As the number of tags is proportional to L, such factorization differs from the Hilbert-space fragmentation where this growth is exponential31,32,33,34.

Dynamic scaling exponent from return probability

Contrast between the three thermal phases in \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) manifests when inspecting how the conserved energy is transported across the blockade chain under the unitary time evolution. At high temperatures, transportation of conversed quantity in generic nonintegrable isolated systems is obedient to the diffusive behavior, which is particularly commonplace for the energy propagation.

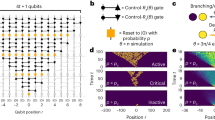

We find this paradigm holds in the thermal phase of \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) but presumably fails in the two thermal phases of \(\tilde{H}\). To examine the transport properties of models (1)–(4) where only energy is conserved, we first utilize the Krylov-typicality technique35,36 to numerically evaluate the connected equal-site time-dependent return probability defined by13 (see Methods section),

where, take \(\tilde{H}\) as an example, \(\langle \cdots \,\rangle := \frac{\,{\text{Tr}}\,[{e}^{-\beta {\tilde{H}}}\cdots \,]}{\,{\text{Tr}}\,[{e}^{-\beta {\tilde{H}}}]},{\rho }_{E}\left(\frac{L}{2},t\right)={e}^{-i{\tilde{H}}t}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{H}}_{i = \frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}{e}^{i{\tilde{H}}t}\) with \(\delta {\rho }_{E}(\frac{L}{2},t):= {\rho }_{E}(\frac{L}{2},t)-\langle {\rho }_{E}(\frac{L}{2},t)\rangle\) representing the density matrix associated to the Hamiltonian density \({\tilde{H}}_{i}:= g{\tilde{X}}_{i}+h{\tilde{Z}}_{i}\) on site \(\frac{L}{2}\), local projector Pi renders the initial energy disturbance concentrated around the chain center allowing a convenient monitoring on how this inhomogeneity gets smeared, \({\mathcal{O}}(\frac{L}{2})={\tilde{H}}_{i = \frac{L}{2}}\), and the inverse temperature \(\beta =\frac{1}{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}\). At long wavelengths, hydrodynamic fluctuations dominate the collective motion involving many particles, giving rise to a universal power-law scaling t−α for the late-time return probability. This dynamic scaling exponent α provides a scheme to classify the transport behaviors into diffusive when \(\alpha =\frac{1}{2}\) or ballistic when α = 1. In between, the transport is subdiffusive if \(0 < \alpha < \frac{1}{2}\) or superdiffusive if \(\frac{1}{2} < \alpha < 1\).

In Fig. 3, we focus attention on \({C}_{L/2}^{E}(t)\) at β = 0 for comparing \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\). Deploy Krylov-typicality approximation by averaging over 1000 independent pure states, we evolve a spectrum of open chains with L = 23 up to 35. For fixed h, hP, after the initial transient oscillations, all curves of different sizes converge to one power-law decay of time. Intriguingly, rather than diffusion, the scaling exponent of the energy transport in \(\tilde{H}\) across the small-h regime is close to \(\frac{3}{4}\), indicating a putative superdiffusion within the early-to-intermediate time window19. Some important caveats about this claim have been at the end of the section. [Controversially, Ljubotina et al.22 tended to claim that the energy transport in the PXP model (the h = 0 point of \(\tilde{H}\)) belonged to the superdiffusive KPZ universality class with a dynamical exponent \(\frac{2}{3}\). However, it was simultaneously written in the caption of Fig. 1 in ref. 22 that “(c) Double-logarithmic plot of the data in (b) shows that power-law convergence to diffusion 1/z = 1/2 is also consistent with the data.” The authors of ref. 22 seemed to find that the numerical data in ref. 22 did not fully support their claim of the KPZ superdiffusion.] As no long-range interactions exist, Lévy flight37 is irrelevant. This exponent \(\frac{3}{4}\) does not belong to the Fibonacci family of the dynamical universality classes38, of which the Gaussian diffusion with exponent \(\frac{1}{2}\) and the KPZ superdiffusion with exponent \(\frac{2}{3}\) are the two eminent members.

The upper (lower) row addresses \(\tilde{H}\,({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} })\). A range of parameters h, hP = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 is organized into 5 columns. The results of system sizes from L = 23–35 converge onto a power law of time, whose exponent from fitting within the short-intermediate time regime is summarized in the bottom-left panel as a function of h (hP) for \(\tilde{H}\,({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} })\).

By contrast, the large-h regime in \(\tilde{H}\) is featured by a ballistic transport typical for integrable systems. On the one hand, this ballistic behavior is unexpected because level statistics in this thermal phase [Fig. 1a] exhibit a tendency toward GOE, thereby being nonintegrable and shall predict a diffusion. Indeed, as a comparison, the lower row of Fig. 3 displays the change to the energy diffusion in \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) driven by hP. This diffusion is consistent with Fig. 1b but contradicts the results of Fig. 5 in ref. 22 where it was shown that the energy transport of \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) converged to the KPZ superdiffusion. On the other hand, \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) are distinct (Figs. 1 and 3) but have the same Nb-symmetry at infinite h, hP (Fig. 2). This integrable point has no transport. So, reasoning assumed Nb-symmetry or integrability is inapplicable to present case either. From transport, the three thermal phases in \(\tilde{H},{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) are all different for the short-intermediate time interval.

The proposed transition between the small- and large-h phases of \(\tilde{H}\) might now be signaled by an evolution between the hypothesized superdiffusive to the ballistic energy transport. In Fig. 3 we show that close to criticality, α ≈ 0.9 when h = 1. Physically, the x, z quantization axes are different due to the infinite-interaction projection. But we find for \(\tilde{H}\) their respective return probabilities are governed by the same exponent, suggesting transport in model (2) is isotropic in spin space19.

Further, we check that entanglement spreadings in both thermal regions of \(\tilde{H}\) are ballistic19, similar to the conventional ETH phases13. Therefore, the computational resource for capturing the long-time dynamics of longer Rydberg chains grows promptly, hinting that it might not be possible for Ljubotina et al.22 to accurately simulate such a long chain (L = 1024) up to such a long period (t = 300) using such a small bond dimension (χ = 256). From Appendix A of ref. 22, we find the issue might arise from the fact that the enhancement of χ in ref. 22 improves both accuracy of the projector P (good) and the unprojected Hamiltonian (bad), hence there might be no monotonic improvement of the simulation in ref. 22 upon increasing χ. (See also ref. 19). Therefore, the main results of ref. 22 might be far from being converged.

Admittedly, in the absence of an appropriate theoretic elucidation of the underlying mechanism, the reported superdiffusive to ballistic transport so far is primarily based on quasiexact numerical simulation that is necessarily limited to fairly small system sizes. In the next section, we attempt to partially address the issue via the tensor network technique. It is found there that the anomalous energy transport in \(\tilde{H}\) could be qualitatively preserved if the present chain lengths get doubled. But it remains entirely possible that due to some overlooked systematic uncertainties, the current accessible short-intermediate-timescale observations may give way to the normal diffusion when getting closer to the genuine asymptotic long-time domain by attacking substantially larger systems.

Likewise, although Fig. 1b suggests that there only exists one dominant thermal phase in \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\), the slow decrease of its transport exponent toward diffusion as evidenced by the lower row of Fig. 3 indicates that the employed system sizes may be too short to access the asymptotic scaling regime. Or, the evolution between the super and the normal diffusion driven by hP is more likely a smooth crossover.

Therefore, great caution needs to be taken when extrapolating the presented results to the thermodynamic limit. In view of the near-term experimental accessibility, these largely early-intermediate-time dynamic observations however may still be worthwhile to stimulate more future explorations along this emerging direction.

Finite-V and finite-T results

We have focused on model (2) which is derived from the more realistic model (1) by first sending V → ∞ and then T → ∞. Now we switch to the purification TEBD method39,40,41 to show that the energy-transport properties found so far are preserved in model (1) at finite V, T, at least within the short-intermediate time scale, thus being experimentally measurable. The essence is to achieve the large-V and high-T condition, g, h ≪ kBT ≪ V. To this end, we fix V = 32 and tune h ∈ [0, 3] and T ∈ [5, 14] in the following matrix-product-state simulation.

Figure 4a–d targets the probable superdiffusion near h = 0. Via computing the return probability at T = 5 by replacing \(\tilde{H}\) with H and setting \({\mathcal{O}}={\sigma }^{x}\) in (5), we illustrate in Fig. 4c up to the maximal bond dimension χ = 1024 that in accord with the top-left panel of Fig. 3, the same type of purported energy superdiffusion characterized by a fitted dynamical exponent \(\frac{3}{4}\) within the short-intermediate time duration arises on an L = 65 Rydberg chain described by model (1). (Finite-size analyses of L = 33, 49, 65 yield the same α19.) Further, Fig. 4j unveils that with fixed χ = 1024, the asserted superdiffusion occurs at T = 7 as well. Thus, a superdiffusive phase might potentially be stabilized in a temperature range T ∈ [5, 7]. Increasing temperature to T = 13 restores the system’s transport to the normal diffusion characterized by \(\alpha =\frac{1}{2}\). In this sense, a super-to-normal diffusion evolution may be assumed to exist in (1) triggered solely by temperature.

a–d Focus on anomalous superdiffusion near pure transverse field limit h = 0. e–h Illustrate the realization of ballistic energy transport after enhancing longitudinal field strength to h = 2.5. i Summarizes dynamical exponents of c–h. Impacts from temperature variation are exemplified through (j, k). For explanations, see text.

The dynamical universality class for the anomalous transport phenomenon is dictated by the scaling exponent and the scaling function. By changing the second operator position in (5) from the chain center to the end, we plot the corresponding spatiotemporal evolutionary contour of \(| {C}_{\beta = 0.2}^{E}|\) in Fig. 4a. Physically, it is reasonable to assume that the correlation function in the hydrodynamic regime satisfies the scaling relation \(| {C}_{\beta = 0.2}^{E}| \propto {t}^{-\alpha }f[(i-{i}_{c})/{t}^{\alpha }]\) with α the scaling exponent and f[⋯] the unknown scaling function. Although the system sizes and time scales achieved in present work do not allow a reliable investigation of the detailed form of the scaling function, in Fig. 4b, we show the preliminary data collapse of the \(| {C}_{\beta = 0.2}^{E}|\) profiles collected at three different moments from Fig. 4a and compare it to a Gaussian fit. With \(\alpha =\frac{3}{4}\) fixed, we find these various data points fall onto a single curve at large i, t, and this line decays rapidly, thus becomes progressively deviating from the Gaussian. This trend is not inconsistent with the claimed superdiffusive behavior predicted by the scaling exponent \(\frac{3}{4}\).

Figure 4e–h targets the case of ballistic energy transport for finite h. Signature of this ballistic diffusion is transparent from Fig. 4h where the return probability at h = 3 exhibits a clean convergent tendency toward the characteristic linear power-law decay with scaling exponent 1 at T = 5 under the enhancement of χ. Therefore, threading a growing longitudinal field while maintaining other parameters intact presumably induces a field-tuned transition between the anomalous superdiffusion at small h [Fig. 4c, d] and the ballistic diffusion at moderate h [Fig. 4g, h]. In addition, by varying T at fixed χ = 1024, Fig. 4k shows that this ballistic behavior persists to T = 7. Conversely, lifting temperature to T = 14 turns the system’s energy propagation to the normal diffusion. Accordingly, at medium h, a temperature-tuned evolution may exist from the ballistic to the diffusive energy transport.

It is worth pointing out that there are two key characteristics of the van der Waals interaction in Rydberg simulator. The first is the constraint (or blockade) effect, arising from the leading, giant nearest-neighbor density-density repulsion. The second is the long-range decaying nature of the van der Waals interaction, whose strength is proportional to R−6 where R is the spatial separation between the two Rydberg atoms. The present work exclusively concerns the limit of strong constraint but neglects all contributions beyond the nearest-neighbor interaction. Besides the above set of parameters, in ref. 19 we also examine the case of V = 100, h ∈ [0, 3], T ∈ [10, 50] that better meets the large-V, high-T condition: g, h ≪ kBT ≪ V. Although the strength of the neglected next-nearest-neighbor van der Waals repulsion equals 0.5 and 1.5625 for these two cases, we find that their energy transport properties are however qualitatively the same, hinting that our main predictions might still be within reach of the real Rydberg simulation facilities. A systematic investigation of the long-range nature of the van der Waals interaction in Rydberg simulator is clearly an important research topic but is currently beyond the scope of our calculations. We are planning to actively pursue this direction in the coming future.

Discussion

Based on large-scale numerical studies of one dimensional Rydberg blockade array, we predict that under strong interaction condition, there seem to exist two distinct types of constrained thermal phases when probed from the short to medium period of relaxation. The first arises in the transverse-field dominated regime whose energy transport is asserted to be superdiffusive featured by a dynamical exponent \(\frac{3}{4}\). The second is stabilized after adding a growing longitudinal field whose energy diffusion appears to be ballistic. Complementary spectral and dynamical analyses suggest that there might exist a transition between the two constrained thermal phases.

An analytical understanding of these numerical findings is currently lacking. Future works can be oriented toward the continual pursuing of the related nonequilibrium phenomenology on sufficiently longer chains or higher dimensions as well as the determination of the scaling function for the superdiffusive phase where the nonlinear fluctuating hydrodynamics42 could be a promising direction.

Ljubotina et al.22 also studied energy superdiffusion at h = 0 limit of model (2). As commented, due to a different scheme they used to realize constraint effects of projector P, Ljubotina et al.22 might encounter convergence issues. Ljubotina et al.22 did not touch upon cases of finite h. So our work is completely independent of ref. 22.

Methods

Energy transport computations

A general strategy for inspecting the transport phenomenon associated to conserved quantity across the system can be visualized as follows. Take the energy transport as an example. As shown by Kim and Huse13 total energy is conserved in closed system and its transport can be studied by first creating a local energy inhomogeneity at the center of the system at the initial time through devising a suitable initial density matrix. Then, under the subsequent unitary time evolution of the Hamiltonian, the spreading of this energy inhomogeneity is captured by the spatial and temporal structures of the connected correlation functions between the time-evolved density matrix and the set of the local Hamiltonian densities on all sites and all bonds. It is worth stressing that the key point in the construction of the initial density matrix is to insert the proper local projection operators so as to render the energy inhomogeneity distribution at the initial time as localized at the system’s center as possible.

For concreteness, we focus temporarily on the Rydberg blockade Hamiltonian repeated below for convenience,

where we introduce the local component of the Hamiltonian (i.e., the Hamiltonian density on site i) as follows,

It is easy to see that one can design two different forms for the initial density matrix corresponding respectively to the two orthogonal terms or channels in (7).

The \(\tilde{X}\) channel. For the \(\tilde{X}\) channel, the initial density matrix can be

which satisfies Tr[ρ(0)] = 1. As the identity operator above corresponds to a static background, one can subtract out it by focusing only on the second term of ρ(0). This defines \(\tilde{\rho }(0)\). At infinite temperature β = 0, the initial energy inhomogeneity distribution is determined by \(\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left[\tilde{\rho }(0){\tilde{H}}_{i}\right]\), which shows that the energy inhomogeneity ε is strictly localized on the central site \(i=\frac{L}{2}\) at t = 0. In fact, at the initial time, ε is strictly localized in the \(\tilde{X}\) channel on the site \(\frac{L}{2}\) because \(\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left({P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{X}}_{\frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}{\tilde{Z}}_{\frac{L}{2}}\right)=0\).

Next, recall the von Neumann equation for the time evolution of the density matrix (ℏ = 1),

then the energy transport is simply governed by \(\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left[\tilde{\rho }(t){\tilde{H}}_{i}\right]\). Or, the connected correlation function for the energy transport is given as follows,

where \({\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)={e}^{-i\tilde{H}t}\left({P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{X}}_{\frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}\right){e}^{+i\tilde{H}t},\langle \cdots \,\rangle =\frac{\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left({e}^{-\beta \tilde{H}}\cdots \,\right)}{\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left({e}^{-\beta \tilde{H}}\right)},\delta {\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)={\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)-\langle {\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)\rangle\), and \(\delta {\tilde{H}}_{i}={\tilde{H}}_{i}-\left\langle {\tilde{H}}_{i}\right\rangle\). Specifically, by setting \(i=\frac{L}{2}\) (as the initial energy inhomogeneity is distributed only on this site), the return probability of the energy transport is defined by

For broader initial inhomogeneity distribution, i should be naturally extended to the sum over a set {i} including all the contributions from the Hamiltonian densities (site and/or bond) whose initial inhomogeneity distribution weights [calculable from taking trace with \(\tilde{\rho }(0)\)] are nonzero. In general, both the normalization constant of the initial density matrix ρ(0) and the infinitesimal perturbation ε might be absorbed into the proper normalization of the connected correlation function. For instance, (11) might be formally normalized as per \(\frac{| {C}_{L/2,\beta }^{E}(t)| }{| {C}_{L/2,\beta }^{E}(0)| }\). Apparently, this normalization procedure does not affect the functional form and the dynamical exponent of a power-law decay in time.

The \(\tilde{Z}\) channel. For the \(\tilde{Z}\) channel, in complete analogy, the initial density matrix reads

At infinite temperature β = 0, the initial energy inhomogeneity ε now is strictly localized in the \(\tilde{Z}\) channel on the central site \(\frac{L}{2}\) because \(\,{\text{Tr}}\,\left({P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{Z}}_{\frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}{\tilde{X}}_{\frac{L}{2}}\right)=0\). Notice that although \({P}_{\frac{L}{2}\pm 1}\) are redundant in (8), they play a key role in (12) to confine the initial energy perturbation in the \(\tilde{Z}\) channel onto the in-between site \(\frac{L}{2}\).

The connected correlation function for the energy transport in this case is given by,

where \({\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)={e}^{-i\tilde{H}t}\left({P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{Z}}_{\frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}\right){e}^{+i\tilde{H}t}\). Specifically, by setting \(i=\frac{L}{2}\) (as the initial energy inhomogeneity is distributed only on this site), the return probability is defined by

Interestingly, we find that although the x, z quantization axes are physically different because the strict projection due to Rydberg blockade is along the z-direction, the transport properties extracted from (11) and (14) are the same19, suggesting the infinite-temperature energy transport of the Rydberg blockade chain is isotropic in the spin space.

The total Hamiltonian density channel. In the literature, most researchers are used to combining all these components together and using the total local Hamiltonian density on the central site as the channel to define the initial density matrix,

It is easy to show that at infinite temperature β = 0, the initial energy inhomogeneity ε is strictly localized on the central site \(\frac{L}{2}\).

The connected correlation function for the energy transport takes the more familiar form under this convention,

where \({\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)={e}^{-i\tilde{H}t}\left({P}_{\frac{L}{2}-1}{\tilde{H}}_{\frac{L}{2}}{P}_{\frac{L}{2}+1}\right){e}^{+i\tilde{H}t}\). Specifically, by setting \(i=\frac{L}{2}\) (as the initial energy inhomogeneity is distributed only on this site), the return probability is defined by

This is precisely the form used in the main text.

Summarizing return probability formulas for different models. Using the same tactic, we can define the return probability formulas for the other three models investigated in the main text.

For the model (3) in the main text, the Hamiltonian is

where the onsite Hamiltonian density

We find the corresponding initial density matrix for \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) could be

The return probability for \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }\) assumes

Here, as usual, \({\rho }_{E}(L/2,t)={e}^{-i{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }t}{\rho }_{E}(L/2,0){e}^{+i{\tilde{H}}^{{\prime} }t}\). As the initial energy inhomogeneity distribution is broader, the second term in (21) now has three contributions,

For the model (4) in the main text, the Hamiltonian is

where the local Hamiltonian density

Note that \({\tilde{H}}_{i}^{{\prime\prime} }\) now has both site and bond terms. For \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime\prime} }\), we choose the corresponding initial density matrix to be onsite, i.e.,

The return probability for \({\tilde{H}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) assumes

For the model (1) in the main text, the Hamiltonian is

Since our primary interest is to target the strong interaction limit, g, h ≪ kBT ≪ V, meaning the contribution of Vnini+1 is negligible, the local Hamiltonian density for H could be assumed to a good approximation as follows,

For H, we choose the corresponding initial density matrix to be onsite, i.e.,

The return probability for H assumes

Data availability

The data set that supports the findings of the present study can be available from the corresponding authors via email upon request.

References

Zotos, X. & Prelovšek, P. Transport in one dimensional quantum systems. In Strong interactions in low dimensions, (eds Baeriswyl, D. & Degiorgi, L.) (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2004) pp. 347–382.

Polkovnikov, A., Sengupta, K., Silva, A. & Vengalattore, M. Colloquium: Nonequilibrium dynamics of closed interacting quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 863 (2011).

Bertini, B. et al. Finite-temperature transport in one-dimensional quantum lattice models. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025003 (2021).

Zotos, X., Naef, F. & Prelovšek, P. Transport and conservation laws. Phys. Rev. B 55, 11029 (1997).

Sirker, J., Pereira, R. G. & Affleck, I. Diffusion and Ballistic Transport in One-Dimensional Quantum Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 216602 (2009).

Kardar, M., Parisi, G. & Zhang, Y.-C. Dynamic Scaling of Growing Interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 889 (1986).

Žnidarič, M. Spin Transport in a One-Dimensional Anisotropic Heisenberg Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 220601 (2011).

Ljubotina, M., Žnidarič, M. & Prosen, T. Spin diffusion from an inhomogeneous quench in an integrable system. Nat. Commun. 8, 16117 (2017).

Scheie, A. et al. Detection of Kardar-Parisi-Zhang hydrodynamics in a quantum Heisenberg spin-1/2 chain. Nat. Phys. 17, 726 (2021).

Wei, D. et al. Quantum gas microscopy of Kardar-Parisi-Zhang superdiffusion. Science 376, 716 (2022).

Keenan, N., Robertson, N. F., Murphy, T., Zhuk, S. & Goold, J. Evidence of Kardar-Parisi-Zhang scaling on a digital quantum simulator. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 72 (2023).

Dupont, M., Sherman, N. E. & Moore, J. E. Spatiotemporal Crossover between Low- and High-Temperature Dynamical Regimes in the Quantum Heisenberg Magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 107201 (2021).

Kim, H. & Huse, D. A. Ballistic Spreading of Entanglement in a Diffusive Nonintegrable System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127205 (2013).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579 (2017).

Chen, C., Chen, Y. & Wang, X. Many-body localization in the infinite-interaction limit and the discontinuous eigenstate phase transition. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 142 (2022).

Chen, C., Chen, Y. & Wang, X. Lieb-Robinson bound for constrained many-body localization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.11363 (2020).

Lesanovsky, I. Many-Body Spin Interactions and the Ground State of a Dense Rydberg Lattice Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 025301 (2011).

Lesanovsky, I. & Katsura, H. Interacting Fibonacci anyons in a Rydberg gas. Phys. Rev. A 86, 041601 (2012).

See Supplementary information for additional derivations and materials.

Chen, C., Burnell, F. & Chandran, A. How Does a Locally Constrained Quantum System Localize? Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 085701 (2018).

Fendley, P., Sengupta, K. & Sachdev, S. Competing density-wave orders in a one-dimensional hard-boson model. Phys. Rev. B 69, 075106 (2004).

Ljubotina, M., Desaules, J.-Y., Serbyn, M. & Papić, Z. Superdiffusive Energy Transport in Kinetically Constrained Models. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011033 (2023).

Khemani, V., Laumann, C. R. & Chandran, A. Signatures of integrability in the dynamics of Rydberg-blockaded chains. Phys. Rev. B 99, 161101 (2019).

Deutsch, J. M. Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system. Phys. Rev. A 43, 2046 (1991).

Srednicki, M. Chaos and quantum thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 50, 888 (1994).

D’Alessio, L., Kafri, Y., Polkovnikov, A. & Rigol, M. From quantum chaos and eigenstate thermalization to statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. Adv. Phys. 65, 239 (2016).

Oganesyan, V. & Huse, D. A. Localization of interacting fermions at high temperature. Phys. Rev. B 75, 155111 (2007).

D’Alessio, L. & Rigol, M. Long-time Behavior of Isolated Periodically Driven Interacting Lattice Systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041048 (2014).

Turner, C. J., Michailidis, A. A., Abanin, D. A., Serbyn, M. & Papić, Z. Weak ergodicity breaking from quantum many-body scars. Nat. Phys. 14, 745 (2018).

Daniel, A. et al. Bridging quantum criticality via many-body scarring. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235108 (2023).

Sala, P., Rakovszky, T., Verresen, R., Knap, M. & Pollmann, F. Ergodicity Breaking Arising from Hilbert Space Fragmentation in Dipole-Conserving Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. X 10, 011047 (2020).

Khemani, V., Hermele, M. & Nandkishore, R. Localization from Hilbert space shattering: From theory to physical realizations. Phys. Rev. B 101, 174204 (2020).

Bastianello, A., Borla, U. & Moroz, S. Fragmentation and Emergent Integrable Transport in the Weakly Tilted Ising Chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 196601 (2022).

Yang, F., Yarloo, H., Zhang, H.-C., Mølmer, K. & Nielsen, A. E. B. Probing Hilbert Space Fragmentation with Strongly Interacting Rydberg Atoms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.13790 (2024).

Steinigeweg, R., Gemmer, J. & Brenig, W. Spin-Current Autocorrelations from Single Pure-State Propagation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 120601 (2014).

Paeckel, S. et al. Time-evolution methods for matrix-product states. Ann. Phys. 411, 167998 (2019).

Zaburdaev, V., Denisov, S. & Klafter, J. Lévy walks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 483 (2015).

Popkov, V., Schadschneider, A., Schmidt, J. & Schütz, G. M. Fibonacci family of dynamical universality classes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12645 (2015).

Vidal, G. Efficient Simulation of One-Dimensional Quantum Many-Body Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 040502 (2004).

Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group in the age of matrix product states. Ann. Phys. 326, 96 (2011).

Karrasch, C., Bardarson, J. H. & Moore, J. E. Finite-Temperature Dynamical Density Matrix Renormalization Group and the Drude Weight of Spin-1/2 Chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 227206 (2012).

Spohn, H. Nonlinear Fluctuating Hydrodynamics for Anharmonic Chains. J. Stat. Phys. 154, 1191 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous Reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions which improve the manuscript a lot. C.C. was supported by a start-up fund from Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the sponsorship from Yangyang Development fund. X.W. was supported by MOST2022YFA1402701 and the NSFC Grant No. 11974244. Y.C. was supported by the SKP of China Grant No. 2022YFA1404204 and the NSFC Grant No. 12274086.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. C.C., X.W., and Y.C. conceived the project. C.C. performed the numerical and analytical calculations. All authors worked on the interpretation of the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Chen, Y. & Wang, X. Superdiffusive to ballistic transport in nonintegrable Rydberg simulator. npj Quantum Inf 10, 90 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00884-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-024-00884-z