Abstract

The essential requirement for fault-tolerant quantum computation (FTQC) is the total protocol design to achieve a fair balance of all the critical factors relevant to its practical realization, such as the space overhead, the threshold, and the modularity. A major obstacle in realizing FTQC with conventional protocols, such as those based on the surface code and the concatenated Steane code, has been the space overhead, i.e., the required number of physical qubits per logical qubit. Protocols based on high-rate quantum low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes gather considerable attention as a way to reduce the space overhead, but problematically, the existing fault-tolerant protocols for such quantum LDPC codes sacrifice other factors. Here, we construct a new fault-tolerant protocol to meet these requirements simultaneously based on more recent progress on the techniques for concatenated codes rather than quantum LDPC codes, achieving a constant space overhead, a high threshold, and flexibility in modular architecture designs. In particular, under a physical error rate of 0.1%, our protocol reduces the space overhead to achieve the logical CNOT error rates 10−10 and 10−24 by more than 90% and 96%, respectively, compared to the protocol for the surface code. Furthermore, our protocol achieves the threshold of 2.5% under a conventional circuit-level error model, substantially outperforming that of the surface code. The use of concatenated codes also naturally introduces abstraction layers essential for the modularity of FTQC architectures. These results indicate that the code-concatenation approach opens a way to significantly save qubits in realizing FTQC while fulfilling the other essential requirements for the practical protocol design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The realization of fault-tolerant quantum computation (FTQC) requires the total protocol design to meet all the essential factors relevant to its practical implementation, such as the space overhead, the threshold, and the modularity. The recent development of constant-overhead protocols1,2,3,4,5,6,7 substantially reduces the space overhead, i.e., the required number of physical qubits per logical qubit, compared to the conventional protocols such as those based on the surface code8,9 and the concatenated Steane code10. In particular, the most recent development4 based on the concatenation of quantum Hamming codes10,11 is promising for the implementation of FTQC since ref. 4 explicitly clarifies the full details of the protocol for implementing logical gates and efficient decoders, making it possible to realize universal quantum computation in a fault-tolerant way. Toward the practical implementation, however, it is indispensable to optimize the original protocol in ref. 4 to improve its threshold, which is, by construction, at least as bad as the concatenated Steane code. Furthermore, even a proper quantitative evaluation of the original protocol in ref. 4 was still missing due to the lack of the numerical study of the protocols based on the quantum Hamming codes.

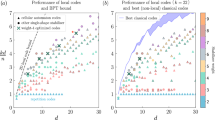

In this work, we construct an optimized fault-tolerant protocol by substantially improving the protocol in ref. 4, achieving an extremely low space overhead and a high threshold to simultaneously outperform the surface code. The optimization is performed based on our quantitative evaluation of the performance of the fault-tolerant protocols for various choices of quantum error-correcting codes (see Tables 1 and 2), which we carried out in a unified way under a circuit-level depolarizing error model following the convention of ref. 12. Our numerical study makes it possible to optimize the combination of the quantum codes to be concatenated. Our numerical results show that the threshold of the original protocol for quantum Hamming codes in ref. 4 is ~10−8. To improve the threshold, our protocol uses the C4/C6 code13, which achieves the state-of-the-art high threshold and is recently realized in experiments14, at the physical level; on top of the C4/C6 code, our protocol concatenates the quantum Hamming codes at the larger concatenation levels to achieve the constant space overhead. Under a physical error rate of 0.1%, compared to the conventional protocol for the surface code, our protocol reduces the space overhead to achieve the logical error rate 10−10 and 10−24 by more than 90% and 96%, respectively (see Fig. 1). The threshold of our protocol is 2.5%, which substantially outperforms that of the surface code (see Table 2). These results establish a basis for the practical fault-tolerant protocols, especially suited for the architectures with all-to-all two-qubit gate connectivity, which is partially achieved experimentally in neutral atoms15, trapped ions16,17, and theoretically proposed in optics18,19,20.

The figure plots the space overheads and logical error rates of the proposed protocol (▴) and the surface code (•). The logical error rate is calculated under a circuit-level depolarizing error model at a physical error rate 0.1%. The dash-dotted lines represent the logical error rate 10−10 and the corresponding space overhead, i.e., 162 physical qubits per logical qubit for our protocol. The dashed lines represent the logical error rate 10−24 and the corresponding space overhead, i.e., 373 physical qubits per logical qubit for our protocol. Our protocol reduces the space overhead to achieve the logical error rates 10−10 and 10−24 by more than 90% and 96%, respectively, compared to the protocol for the surface code.

Results

Setting

We construct a space-overhead-efficient fault-tolerant protocol by optimizing the protocol presented in ref. 4. The original protocol in ref. 4 is based on the concatenation of a series of quantum Hamming codes with increasing code sizes. Quantum Hamming code is a family of quantum codes \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{r}\) parameterized by r ∈ {3, 4, …}, consisting of Nr = 2r − 1 physical qubits and Kr = Nr − 2r logical qubits with code distance 310,11, which is written as an [[Nr, Kr, 3]] code. By concatenating the quantum Hamming code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l}}\) for a sequence \({({r}_{l} = l+2)}_{l = 1,2,\ldots }\) of parameters at the concatenation level l ∈ {1, …, L}, we obtain a quantum code consisting of \(N=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{l = 1}^{L}{N}_{{r}_{l}}\) physical qubits and \(K=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{l = 1}^{L}{K}_{{r}_{l}}\) logical qubits. Its space overhead, defined by the ratio of N and K2, converges to a finite constant factor η∞ as

where η∞ is given by η∞ ≈ 364. However, the threshold of the protocol based on this quantum code is given by ~10−8, as shown in Supplementary Information. As discussed in ref. 4, instead of rl = l + 2, we can also take an arbitrary sequence \({({r}_{l})}_{l = 1,2,\ldots }\) satisfying \({\eta }_{\infty }=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{l = 1}^{\infty }\frac{{N}_{{r}_{l}}}{{K}_{{r}_{l}}} < \infty\) to achieve the constant space overhead, and our choice of rl will be clarified below.

We optimize this original protocol by replacing the physical qubits of the original protocol with logical qubits of a finite-size quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{0}\) (called an underlying quantum code). With this replacement, we aim to improve the threshold determined at the physical level while maintaining the constant space overhead at the large concatenation levels. Here, the logical error rate of the logical qubits of the underlying quantum code should be lower than the threshold of the original protocol so that the original protocol can further suppress the logical error rate. If the underlying quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{0}\) has N0 physical qubits and K0 logical qubits, the overall space overhead is given by

which remains a constant value given by \({\eta }_{\infty }^{{\prime} }=\frac{{N}_{0}}{{K}_{0}}{\eta }_{\infty }\) as long as we use a fixed code as the underlying quantum code.

For our protocol, we propose the following code construction:

-

As an underlying quantum code, we use the C4/C6 code13 as first \({L}^{{\prime} }\) levels of the concatenated code, where the 4-qubit code denoted by C4(=[4, 2, 2]) is concatenated with the 6-qubit code denoted by C6(= [6, 2, 2]) for \({L}^{{\prime} }-1\) times.

-

On top of the underlying quantum code, i.e., at the concatenation levels \({L}^{{\prime} }+1,{L}^{{\prime} }+2,\ldots ,L\), we concatenate quantum Hamming codes \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l}}\) for an optimized choice of the sequence \({({r}_{l})}_{l = 1,2,\ldots }\) of parameters, where \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l}}\) is used at the concatenation level \({L}^{{\prime} }+l\).

The C4/C6 code is adopted as the underlying quantum code since it achieves the state-of-the-art high threshold. To avoid the increase of overhead, we use a non-post-selected protocol of the C4/C6 code in ref. 13 rather than a post-selected one that excludes the error-detected events.

To estimate the space overhead and the threshold, we evaluate the logical CNOT error rate of the fault-tolerant protocols based on the C4/C6 code and the quantum Hamming codes. The logical CNOT error rate is evaluated at each concatenation level using the Monte Carlo sampling method in refs. 21,22, which is based on the reference entanglement method13,23. By convention, we describe the noise on physical qubits by a circuit-level depolarizing error model (see “Methods” for the details of the simulation method and the error model). In the simulation, we assume no geometrical constraints on manipulating quantum gates, which is applicable to neutral atoms15, trapped ions16,17, and optics18,19,20. Our numerical results show that by using the C4/C6 code as the underlying quantum code, our protocol achieves a high threshold 2.5% (see Table 2), where we use the non-post-selected protocol of the C4/C6 code rather than the post-selected one in ref. 13. We optimize the combination of the quantum codes, i.e., the choice of parameters \({L}^{{\prime} }\), L, and rl, based on our simulation results so as to reduce the space overhead. In particular, the optimized parameters that we found are \({L}^{{\prime} }=5\), L = 9, and r1 = 5, r2 = 6, r3 = r4 = 7 (see Table 1). Note that the quantum codes \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{3},{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{4}\) in the original protocol of ref. 4 are skipped to improve the space overhead of our protocol. The quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{7}\) is used twice since the quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{8}\) in level-9 is not expected to reduce the logical error to 10−24. To avoid the combinatorial explosion arising from the combinations of these parameters, we performed a level-by-level numerical simulation at each concatenation level (see “Methods” for the details). With this technique, our simulation makes it possible to flexibly optimize the combination of the quantum codes to be concatenated for designing our protocol.

Large-scale resource estimation

Under a physical error rate of 0.1%, we compare the space overhead of our proposed protocol to achieve the logical CNOT error rates 10−10 and 10−24 with a conventional protocol for the surface code. Note that another conventional protocol using the concatenated Steane code cannot suppress the logical error rate under the physical error rate 0.1% since the threshold is larger than 0.1% (see Table 2). Factoring of a 2048-bit integer using Shor’s algorithm24 requires the logical error rate 10−10 (ref. 25), which is relevant to the currently used cryptosystem RSA-204826,27. The logical error rate ~10−24 is a rough estimate of the logical error rate of classical computation (see Methods for the details of these estimations).

As shown in Fig. 1, the surface code requires the space overhead ~1.7 × 103 and ~10.2 × 103 to achieve the logical error rates ~10−10 and ~10−24, respectively. On the other hand, our protocol only requires the space overheads ~162 and ~373 to achieve the same logical error rates, saving the space overheads by more than 90% and 96%, respectively, compared to the surface code. Note that our protocol achieves constant space overhead while the protocol for the surface code (as well as that for the concatenated Steane code) has growing space overhead; thus, in principle, the advantage of our protocol can be arbitrarily large as the target logical error rate becomes small. However, our contribution here is to clarify that our protocol indeed offers a space-overhead advantage by orders of magnitude in the practical regimes.

Comparison on underlying quantum codes

The quantum code for our protocol, shown in Table 1 is obtained by optimizing the underlying quantum code, and under the physical error rate 0.1%, our optimized choice of the underlying quantum code turns out to be the level-5 C4/C6 code. Here, we show this optimization procedure in more detail. For this optimization, we compare four candidate quantum codes: the C4/C6 code13, the surface code8,9, the concatenated Steane code28, and the C4/Steane code. The C4/Steane code is newly constructed in this work by concatenating the [4, 2, 2] code (i.e., the C4 code) with the Steane code (see Supplementary Information for details). For each underlying code, we optimize the concatenation level or the distance of the underlying code and the series of the quantum Hamming codes, and compare the required overall space overhead to achieve the logical error rate 10−24.

In Fig. 2 and Table 2, we compare the thresholds of these four underlying quantum codes and the space overheads of the overall quantum codes obtained by concatenating the underlying codes with the series of quantum Hamming codes to achieve the logical error rate 10−24 at the physical error rates p ∈ [0.01%, 1%]. In Fig. 2, we call the concatenated code of X and the series of quantum Hamming codes as X/Hamming for X ∈ {C4/C6, surface, Steane, C4/Steane}. For a fair comparison, we performed the numerical simulation of implementing logical CNOT gates for all four codes under the aforementioned circuit-level depolarizing error model. For the decoding of the surface code, we use the minimum-weight perfect matching decoder29,30, and for the other concatenated codes, we use a hard-decision decoder to cover practical situations where the efficiency of implementing the decoder matters (see Supplementary Information for more details). Conventionally, the threshold for the surface code is evaluated by implementing a quantum memory (i.e., the logical identity gate)12, but for a fair comparison, we here evaluate that by the logical CNOT gate, which is implemented by lattice surgery31,32 and is simulated using the method in ref. 33 (see Supplementary Information for details). Similarly, ref. 28 evaluates the threshold for the concatenated Steane code by implementing the logical identity gate, but we evaluate that by the transversal implementation of the logical CNOT gate. Note that the thresholds evaluated by the logical CNOT gate may be worse than those by the logical identity gate32, but our setting of the numerical simulation is motivated by the fact that the realization of quantum memory by just implementing the logical identity gate is insufficient for universal quantum computation. We also remark that various numerical simulations have been performed in the literature under different error models from ours, e.g., for the surface code in refs. 34,35, for the concatenated Steane code in refs. 22,34, and for the C4/C6 code in refs. 13,36, but our contribution here is to perform the numerical simulation of all the codes under the same circuit-level error model in a unified way to make a direct, systematic comparison.

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, the C4/C6/Hamming code has the minimum space overhead for physical error rates p ∈ [0.01%, 1%]. At the same time, the space overheads of the Surface/Hamming and C4/Steane/Hamming codes are of the same magnitude as that of the C4/C6/Hamming code for a low physical error rate p ~0.01%.

Comparison with the quantum low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes

We have so far offered a quantitative analysis of our protocol based on the code-concatenation approach. We here compare this approach with another existing approach toward low-overhead FTQC based on the high-rate quantum LDPC codes originally proposed in refs. 1,2,3.

The crucial difference between our approach, based on concatenated codes, and the approach based on quantum LDPC codes is modularity. In the approach of quantum LDPC code, one needs to realize a single large-sized code block. To suppress the logical error rate more and more, each code block may become arbitrarily large, yet an essential assumption for the fault tolerance of the quantum LDPC codes is to keep the physical error rates constant2,3. In experiments, problematically, it is in principle challenging to arbitrarily increase the number of qubits in a single quantum device without increasing physical error rates37,38. By contrast, in the code-concatenation approach, we can realize a fixed-size code at each level of the code concatenation by putting finite efforts into improving a quantum device; that is, each fixed-size code serves as a fixed-size abstraction layer in the implementation that is stored in a single module. As shown in ref. 4, as we increase the concatenation levels, the logical error rates are suppressed doubly exponentially, whereas the required number of gates for implementing each gadget grows much more slowly. Once the error rates are suppressed by a concatenated code at some concatenation level, the low error rate of each logical gate provides a margin for using more logical gates (i.e., tolerating more architectural overhead) to implement FTQC at the higher concatenation levels, which provides flexibility for scalable architecture design. For example, once we develop finite-size devices implementing the fixed-size code, we can further scale up FTQC by combining these error-suppressed devices by using quantum channels to connect these devices and implement another fixed-size code to be concatenated at the next concatenation level. These quantum channels can be noisier than the physical gates in each device since the quantum states that will go through the channels are already encoded. In this way, our code-concatenation approach offers modularity, an essential requirement for the FTQC architectures.

Apart from the modularity, another advantage is that our protocol, based on concatenated codes, can implement logical gates faster than the existing protocols for quantum LDPC codes. In the protocol for quantum LDPC codes in refs. 2,3, almost all gates, including most of the Clifford gates, are implemented by gate teleportation using auxiliary code blocks; to maintain constant space overhead, gates must be applied sequentially, which incurs the polynomial time overhead. Other Clifford gate schemes are proposed based on code deformation5 and lattice surgery6, but they also introduce additional overheads. In particular, the code deformation scheme may introduce an additional time overhead that may be worse than the gate teleportation method5. The lattice surgery scheme requires a large patch of the surface code, which makes the space overhead of the overall protocol non-constant if we want to attain low time overhead6. Apart from these schemes for logical gate implementations, a stabilizer measurement scheme for a constant-space-overhead quantum LDPC code in thin planar connectivity is presented in ref. 7. This protocol implements a quantum memory (i.e., the logical identity gate), but to implement universal quantum computation in a fault-tolerant way, we need to add the components to implement state preparation and logical gates, which incur the overhead issues in the same way as the above. More recent protocols in refs. 39,40 aim to improve the implementability of quantum LDPC codes, but in the same way, these protocols can only be used as the quantum memory; problematically, it is currently unknown how to realize logical gates with these protocols, and it is also unknown how to achieve constant-space-overhead FTQC based on these protocols without sacrificing their implementability. In contrast with these protocols, our protocol can implement universal quantum computation within constant space overhead and quasi-polylogarithmic time overhead, by using the concatenated code rather than quantum LDPC codes, as shown in ref. 4.

We remark that, due to this difference, it is not straightforward to obtain numerical results on the existing protocols for the high-rate quantum LDPC codes in the same setting as our protocol; however, if one develops more efficient protocols achieving universal quantum computation using the high-rate quantum LDPC codes, the current numerical results on comparing our protocol with those of the surface code and the concatenated Steane code also serve as a useful baseline for further comparison, which we leave for future work. We also point out that in the current status, even if one wants to implement constant-space-overhead FTQC using quantum LDPC codes, one eventually needs to use concatenated codes in combination. In particular, as shown in refs. 2,3, the existing constant-space-overhead fault-tolerant protocols for such quantum LDPC codes rely on concatenated codes for preparation of logical \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) states, e.g., by using the encoding procedure implemented by the concatenated Steane code41. Thus, even though a part of the protocol using the high-rate quantum LDPC codes may be efficient, the part relying on the concatenated codes may become a bottleneck in practice, which should be taken into account in future work for a fair comparison of the overall protocols.

Discussion

In this work, we have constructed a low-overhead, high-threshold, modular protocol for FTQC based on the recent progress on the code-concatenation approach in ref. 4. To design our protocol, we have performed thorough numerical simulations of the performance of fault-tolerant protocols for various quantum codes, under the same circuit-level error model in a unified way, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2 and Tables 1 and 2. Based on these numerical results, we have proposed an optimized protocol, which we have designed by seeking an optimized combination of the underlying quantum code at the physical level and the series of quantum Hamming codes at higher concatenation levels. The proposed protocol (Table 1) uses a fixed-size C4/C6 code at the physical level to attain a high threshold and, on top of this underlying quantum code, concatenates the quantum Hamming codes to achieve the constant space overhead. This proposed protocol achieves a substantial saving of the space overhead compared to that of the surface code (Fig. 1), has a higher threshold of 2.5% than those of the surface code and the concatenated Steane code (Table 2), and offers modularity owing to the code-concatenation approach.

At the same time, as shown in Fig. 2, our results show that other choices of the underlying quantum code can achieve a similar space overhead to the C4/C6 code depending on the physical error rate; in particular, we find that the surface code and the C4/Steane code that we have developed in this work can achieve a similar space overhead compared to the C4/C6 code at the physical error rate 0.01%. This result implies that the underlying code can be further optimized by considering other factors of the fault-tolerant quantum computation, such as the connectivity. Since our protocol is based on concatenated codes, the proposed protocol has flexibility in the choice of the underlying quantum code and the sequence of quantum Hamming codes to be concatenated, which will also be useful for further optimization of fault-tolerant protocols depending on the advances of experimental technologies in the future.

We have constructed our fault-tolerant protocol without assuming geometrical constraints on quantum gates. Non-local interactions are indispensable to avoid the growing space overhead of FTQC on large scales, which has been a major obstacle to implementing FTQC. By combining the swapping technique in ref. 42 with the protocol shown in ref. 4, we can implement the constant space overhead protocol with two-dimensional nearest-neighbor gates or one-dimensional next-nearest-neighbor gates (reference43 shows that polylogarithmic space overhead is required for d-dimensional implementation of protocols with quantum LDPC codes for any d, but this limitation does not apply to protocols with concatenated codes39). However, it is unclear whether the constant space overhead protocol can be implemented using one-dimensional nearest-neighbor gates without sacrificing the distance of codes at each concatenation level (see also footnote d in ref. 44). By contrast, all-to-all connectivity of physical gates is indeed becoming possible in various experimental platforms, such as neutral atoms15, trapped ions16,17, and optics18,19,20; in such cases, the proposed protocol substantially reduces the space overhead compared to the surface code, as shown in Fig. 1. Consequently, our protocol lends increased importance to such physical platforms with all-to-all connectivity; at the same time, the technological progress on the experimental side may also lead to extra factors to be considered for practical FTQC protocols, and our results and techniques constitute a basis for further optimization of the fault-tolerant protocols in these platforms.

Lastly, we remark that the fault-tolerant protocol requires auxiliary qubits to extract the syndrome of the quantum code and prepare the magic states. Since ref. 4 shows the full fault-tolerant protocol, which leaves the space overhead constant even including the auxiliary qubits, our proposed protocol also achieves the constant space overhead, including the auxiliary qubits, in the asymptotic regime. However, the original protocol in ref. 4 is not optimized to reduce the number of auxiliary qubits, so it still remains unclear if the space overhead, including auxiliary qubits, may be significantly better than the conventional protocols based on the surface code at a finite regime. One way to circumvent this problem is to reduce the number of auxiliary qubits by using the flag qubits21,45,46,47,48,49,50. The fault-tolerant protocol constructed in ref. 4 uses a variant of Knill’s error correction gadget, which uses a copy of the code block for the fault-tolerant syndrome extraction (see Fig. 3a). On the other hand, the flag-qubit protocol shown in ref. 46 requires two auxiliary qubits for the fault-tolerant syndrome extraction of the quantum Hamming codes (see Fig. 3b). The idea of flag qubits is extended to the error correction of arbitrary stabilizer codes47,48 and the fault-tolerant gate operations21,49,50. Based on these ideas, it is essential to optimize the entire fault-tolerant protocol, as has been recently done for many-hypercube codes in ref. 51. We leave it as future work to optimize the full fault-tolerant protocol using the idea of the flag qubits to reduce the number of auxiliary qubits and evaluate its performance.

a A variant of Knill’s error correction gadget for the Steane code4,13. A copy of the code block is used for the fault-tolerant syndrome extraction. The symbols \(\left\vert \bar{0}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \bar{+}\right\rangle\) in the circuit represent the logical zero and plus states, respectively. b The flag-qubit fault-tolerant Z syndrome extraction of the Steane code using two auxiliary qubits49,64. This circuit, followed by the fault-tolerant X syndrome extraction, which is similarly constructed, constitutes the error correction gadget.

Methods

In Methods, after summarizing the notations, we first describe the error model used in the numerical simulation and the Monte Carlo simulation method to evaluate the logical CNOT error rate. Then, we provide the details of our estimation of the required logical error rate of quantum computation, based on the evaluation of the CNOT gate counts of the quantum circuit implementing Shor’s algorithm for 2048-bit RSA integer factoring and the required error rates for the classical computation. Finally, we present our method for estimating the logical CNOT error rate of the large-scale concatenated codes using the small-scale level-by-level simulation results at each concatenation level.

Notation

The computational basis (also called the Z basis) of a qubit \({{\mathbb{C}}}^{2}\) is denoted by \(\{\left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle \}\), and the complementary basis (also called the X basis) \(\{\left\vert +\right\rangle ,\left\vert -\right\rangle \}\) is defined by \(\left\vert \pm \right\rangle :=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \pm \left\vert 1\right\rangle )\). By the convention of ref. 52, we use the following notation on 1-qubit and 2-qubit unitaries:

where the 1-qubit and 2-qubit unitaries are shown in the matrix representations in the computational bases \(\{\left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle \}\subset {{\mathbb{C}}}^{2}\) and \(\{\left\vert 0\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 0\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert 1\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle \otimes \left\vert 1\right\rangle \}\subset {{\mathbb{C}}}^{2}\otimes {{\mathbb{C}}}^{2}\), respectively. See also ref. 53 for terminology on FTQC.

Error model

In this work, the stabilizer circuits for describing the fault-tolerant protocols are composed of state preparations of \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\), measurements in the Z and X bases, single-qubit gates I, X, Y, Z, H, S, and a two-qubit CNOT gate. Each of these preparation, measurement, and gate operations in a circuit is called a location in the circuit. By the convention of ref. 12, we use a circuit-level depolarizing error model. In this model, independent and ideally distributed (IID) Pauli errors randomly occur at each location, i.e., after state preparations and gates, and before measurements. By convention, we ignore the error and the runtime of polynomial-time classical computation used for decoding in the fault-tolerant protocols.

The probabilities of the errors are given using a single parameter p (called the physical error rate) as follows. State preparations of \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) are followed by X and Z gates, respectively, with probability p. Measurements in Z and X bases follow X and Z gates, respectively, with probability p. One-qubit gates I, X, Y, Z, H, S are followed by one of the 3 possible non-identity Pauli operators {X, Y, Z}, each with probability p/3. A two-qubit gate CNOT is followed by one of the 15 possible non-identity Pauli products acting on 2 qubits \({\{{\sigma }_{1}\otimes {\sigma }_{2}\}}_{({\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2})\in {\{I,X,Y,Z\}}^{2}}\setminus \{I\otimes I\}\), each with probability p/15. We also investigate different error models, where the Pauli error rate on the identity gate I is changed from p/3 to γ/3, where γ is taken to be γ = p/2 and γ = p/10. As shown in Fig. 4, our protocol, shown in Table 1 significantly reduces the space overhead compared to that for the surface code in these error models (see Supplementary Information for more details).

The figure plots the space overheads and logical error rates of the proposed protocol shown in Table 1 (▴ for γ = p, ▾ for γ = p/2 and ◂ for γ = p/10) and the surface code (• for γ = p, ■ for γ = p/2 and ♦ for γ = p/10). The plots for the error model γ = p are the same as shown in Fig. 1. The logical error rate is calculated under a circuit-level depolarizing error model at a physical error rate 0.1%. The dash-dotted and lines represent the logical error rate 10−10 and 10−24, respectively. Our protocol reduces the space overhead compared to the protocol for the surface code in a similar magnitude as in the error model used in Fig. 1.

Simulation to evaluate logical CNOT error rates

In our numerical simulation, we evaluate the logical CNOT error rate using the Monte Carlo sampling method presented in refs. 21,22, which is based on the reference entanglement method13,23. For a quantum code consisting of N physical qubits and K logical qubits, the circuit that we use for the Monte Carlo sampling method is illustrated in Fig. 5, where we assume that random Pauli errors occur at each location of the circuit according to the error model described above. In particular, starting from two error-free logical Bell states, we repeatedly apply a gate gadget of the logical CNOT⊗K gate, followed by an error correction gadget, which is repeated ten times. For all the quantum codes (which are Calderbank-Shor-Steane (CSS) codes in this work) except for the surface code, we implement the logical CNOT gates transversally and use Knill’s error correction gadget13 for error correction. Note that Steane’s error correction gadget53,54 may also have a similar performance to Knill’s, but in practice, Knill’s error correction gadget is more robust to leakage errors than Steane’s55 and thus is preferable to use if possible. We also note that the addressable CNOT gate can be performed via gate teleportation using a certain stabilizer state56, and the threshold of the distillation of a logical stabilizer state is much larger than that of the logical CNOT gate. Therefore, we expect the threshold of the addressable CNOT gate is comparable with that of the transversal CNOT gate. For the surface code, by convention, we use the lattice surgery31,32 to implement the logical CNOT gates, which includes the error correction. Note that the transversal implementation of the logical CNOT gate is also possible for the surface code57, but we performed our numerical simulation based on the lattice surgery since the lattice surgery is more widely used in the literature on resource estimation for FTQC, such as refs. 58,59, and the threshold of the lattice surgery CNOT is better than the transversal CNOT, as shown in ref. 57. Then, we apply the error-free logical Bell measurement on the output quantum state. Any measurement outcomes that do not result in all zeros for the kth logical qubits in four code blocks are counted as logical errors on the kth logical qubit for k ∈ {1, …, K}. We evaluate the logical CNOT error rate by dividing the empirical logical error probability in the simulation by ten and averaging over the K logical qubits. Since the quantum circuit in Fig. 5, including Pauli errors, is composed of Clifford gates, the sampling of measurement outcomes is efficiently simulated by a stabilizer circuit simulator; in particular, our simulation is conducted with STIM60.

In this simulation, starting from two error-free logical Bell states, we apply a gate gadget of the logical CNOT⊗K gate, followed by the error correction gadget ten times, using a noisy circuit. For the surface code, we use the lattice surgery31,32 to implement logical CNOT gates, which includes the error correction. For the other codes, we implement logical CNOT gates transversally and use Knill’s error correction gadget13 for error correction. Finally, we apply the error-free logical Bell measurement on the output quantum state to estimate the logical error rate. The symbol with XK (ZK) denotes the measurements in X (Z) basis for all the K logical qubits in a code block.

Logical error rate required for 2048-bit RSA integer factoring

The security of the RSA cryptosystem is ensured by the classical hardness of integer factoring, and factoring 2048-bit integers given as the product of two similar-sized prime numbers, which is called RSA integers in ref. 25 leads to breaking RSA-2048. Previous works have investigated efficient algorithms for RSA integer factoring based on Shor’s algorithm24. In particular, ref. 25 proposes an n-bit RSA integer factoring algorithm using 0.3n3 + 0.0005n3lg n Toffoli gates. Since a Toffoli gate can be decomposed into 6 CNOT gates and single-qubit gates52, this algorithm can be implemented by 1.8n3 + 0.003n3lg n CNOT gates. For n = 2048, it requires ~1010 CNOT gates. Thus, we require a logical error rate ~10−10 to run this algorithm.

Required error rate for classical computation

The required error rate for classical computation is estimated by taking an inverse of the number of elementary gates in a large-scale classical computation that is currently available. In particular, we consider a situation where the supercomputer Fugaku61 is run for a month. The peak performance at double precision of Fugaku in the normal mode is given as 488 petaflops ~5 × 1017 s−1 61. If we run it for 1 month ~2.6 × 106 s, then the number of elementary gates is roughly estimated as ~1024. Thus, an upper bound of the logical error rate of classical computation is roughly estimated as ~10−24.

Estimation of logical error rates of large-scale quantum codes from small-scale level-by-level simulations

In this work, we use an underlying quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{0}\) concatenated with a series of quantum Hamming codes \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{1}},{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{2}},\ldots ,{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{L}}\). The logical error rate of the overall quantum code under the physical error rate p is evaluated from the level-by-level numerical simulation as

where P0(p) is the logical error rate of \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{0}\) under the physical error rate p, and \({P}_{{r}_{l}}^{({r}_{l+1})}(p)\) is that of the quantum Hamming code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l}}\). Note that the protocol depends on the quantum code concatenated above (i.e., \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l+1}}\)), thus the logical error rate of the level-l protocol depends on rl and rl+1 (see ref. 4 for the details). For the top code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{L}}\), we implement the protocol such that we can concatenate the quantum code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{L}+1}\) if needed. Thus, the logical error rate on the top code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{L}}\) is evaluated as \({P}_{{r}_{L}}^{({r}_{L}+1)}\). This estimation gives the upper bound of the logical error rate in the cases where the logical CNOT gates (rather than initial-state preparation of \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\), single-qubit Pauli and Clifford gates, and measurements in Z and X bases) have the largest error rate in the set of elementary operations for the stabilizer circuits, which usually holds true since the gadget for the CNOT gate is the largest. The logical error rates P0(p) and \({P}_{{r}_{l}}(p)\) for each l ∈ {1, …, L} are estimated by the numerical simulation using the circuit described in Fig. 5. See Supplementary Information for more details.

With our numerical simulation, we obtain the parameters of the following fitting curves of the logical error rates (see Supplementary Information for more details). For the quantum Hamming code \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{r}_{l}}\) with parameter rl, due to distance 3, Pr(p) is approximated for \({r}_{l}\in \{3,4,5,6,7\},{r}_{l+1}\in \{{r}_{l}+1,\ldots ,\max ({r}_{l}+1,7)\}\) by the following fitting curve

The logical error rate of the level-l C4/C6 code, denoted by \({P}_{{C}_{4}/{C}_{6}}^{(l)}(p)\), is approximated by a fitting curve

where Fl is the Fibonacci number defined by F1 = 1, F2 = 2, and Fl = Fl−1 + Fl−2 for l > 213. The threshold \({p}_{{C}_{4}/{C}_{6}}^{({\rm{th}})}\) for the C4/C6 code is estimated by

The logical error rate of the surface code with code distance d, denoted by \({P}_{{\rm{surface}}}^{(d)}(p)\), is approximated by a fitting curve

Based on the critical exponent method in ref. 62, the threshold \({p}_{{\rm{surface}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\) of the surface code is estimated as a fitting parameter of another fitting curve given by

The logical error rate of the level-l concatenated Steane code, denoted by \({P}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{(l)}(p)\), is approximated for l ∈ {1, 2} by a fitting curve

For l ≥ 3, due to the limitation of computational resources, we did not directly perform the numerical simulation to determine \({a}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{(l)}\) in (17), but using the results for l ∈ {1, 2} in (17), we recursively evaluate the logical error rates \({P}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{(l)}(p)\) of level-l concatenated Steane code as

The threshold \({p}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\) of the concatenated Steane code is estimated by that satisfying \({P}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{(2)}({p}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})})={p}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\), i.e.,

The logical error rates of the level-l C4/Steane codes for l ∈ {1, 2}, denoted by \({P}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{(l)}(p)\), are approximated by fitting curves

where \({a}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{(1)}\) is given by \({a}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{(1)}={A}_{{C}_{4}/{C}_{6}}{B}_{{C}_{4}/{C}_{6}}\) from the logical error rate of the level-1 C4/C6 since the level-1 C4/Steane code coincides with the level-1 C4/C6 code. For l ≥ 3, similar to the concatenated Steane code, logical error rates \({P}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{(l)}(p)\) of the level-l C4/Steane code are evaluated by

Since the C4/Steane code at concatenation levels 2 and higher becomes the same as the concatenated Steane code, the threshold \({p}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\) of the C4/Steane code is determined by the physical error rate that can be suppressed below \({p}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\) at level 2, estimated as that satisfying \({P}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{(2)}({p}_{{C}_{4}/{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})})={p}_{{\rm{Steane}}}^{({\rm{th}})}\), i.e.,

Using the fitting parameters of these fitting curves obtained from the level-by-level numerical simulations, we evaluate the overall logical error rate according to (10).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/sy3104/concatenated_code_threshold.

Code availability

The source codes for the simulation of the underlying codes (except for the surface code) and the quantum Hamming codes are available in GitHub and can be accessed via this link https://github.com/sy3104/concatenated_code_threshold.

References

Kovalev, A. A. & Pryadko, L. P. Fault tolerance of quantum low-density parity check codes with sublinear distance scaling. Phys. Rev. A 87, 020304 (2013).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. Quantum Info Comput. 14, 1338–1372 (2014).

Fawzi, O., Grospellier, A. & Leverrier, A. Constant overhead quantum fault-tolerance with quantum expander codes. In: 2018 IEEE 59th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS). 743–754 (IEEE, 2018).

Yamasaki, H. & Koashi, M. Time-efficient constant-space-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation. Nat. Phys. 20, 247–253 (2024).

Krishna, A. & Poulin, D. Fault-tolerant gates on hypergraph product codes. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011023 (2021).

Cohen, L. Z., Kim, I. H., Bartlett, S. D. & Brown, B. J. Low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computing using long-range connectivity. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn1717 (2022).

Tremblay, M. A., Delfosse, N. & Beverland, M. E. Constant-overhead quantum error correction with thin planar connectivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 050504 (2022).

Bravyi, S. B. & Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum codes on a lattice with boundary https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9811052 (1998).

Dennis, E., Kitaev, A., Landahl, A. & Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452–4505 (2002).

Steane, A. M. Simple quantum error-correcting codes. Phys. Rev. A 54, 4741 (1996).

Hamming, R. W. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 29, 147–160 (1950).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Knill, E. Quantum computing with realistically noisy devices. Nature 434, 39–44 (2005).

Paetznick, A. et al. Demonstration of logical qubits and repeated error correction with better-than-physical error rates. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.02280 (2024).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041058 (2021).

Egan, L. et al. Fault-tolerant control of an error-corrected qubit. Nature 598, 281–286 (2021).

Yamasaki, H., Fukui, K., Takeuchi, Y., Tani, S. & Koashi, M. Polylog-overhead highly fault-tolerant measurement-based quantum computation: all-gaussian implementation with Gottesman-Kitaev-Preskill code. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.05416 (2020).

Bourassa, J. E. et al. Blueprint for a scalable photonic fault-tolerant quantum computer. Quantum 5, 392 (2021).

Litinski, D. & Nickerson, N. Active volume: an architecture for efficient fault-tolerant quantum computers with limited non-local connections. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.15465 (2022).

Goto, H. Step-by-step magic state encoding for efficient fault-tolerant quantum computation. Sci. Rep. 4, 7501 (2014).

Goto, H. Minimizing resource overheads for fault-tolerant preparation of encoded states of the steane code. Sci. Rep. 6, 19578 (2016).

Schumacher, B. Sending entanglement through noisy quantum channels. Phys. Rev. A 54, 2614 (1996).

Shor, P. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. 124–134 (IEEE Computer Society, 1994).

Gidney, C. & Ekerå, M. How to factor 2048 bit rsa integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits. Quantum 5, 433 (2021).

Rivest, R. L., Shamir, A. & Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 21, 120–126 (1978).

Barker, E. & Dang, Q. Nist special publication 800-57 part 1, revision 4. NIST, Tech. Rep. Vol. 16 (NIST Computer Security Resource Center, 2016).

Steane, A. M. Overhead and noise threshold of fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A 68, 042322 (2003).

Higgott, O. Pymatching: A python package for decoding quantum codes with minimum-weight perfect matching. https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.13082 (2021).

Higgott, O. & Gidney, C. Sparse blossom: correcting a million errors per core second with minimum-weight matching. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.15933 (2023).

Horsman, D., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Van Meter, R. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. N. J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Vuillot, C. et al. Code deformation and lattice surgery are gauge fixing. N. J. Phys. 21, 033028 (2019).

Gidney, C. Stability experiments: the overlooked dual of memory experiments. Quantum 6, 786 (2022).

Cross, A. W., Divincenzo, D. P. & Terhal, B. M. A comparative code study for quantum fault tolerance. Quantum Info Comput. 9, 541–572 (2009).

Chamberland, C. & Ronagh, P. Deep neural decoders for near term fault-tolerant experiments. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 044002 (2018).

Goto, H. & Uchikawa, H. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with a soft-decision decoder for error correction and detection by teleportation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2044 (2013).

Xu, Q. et al. Constant-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation with reconfigurable atom arrays. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.08648 (2023).

Fellous-Asiani, M. et al. Optimizing resource efficiencies for scalable full-stack quantum computers. PRX Quantum 4, 040319 (2023).

Pattison, C. A., Krishna, A. & Preskill, J. Hierarchical memories: Simulating quantum ldpc codes with local gates. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.04798 (2023).

Bravyi, S. et al. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.07915 (2023).

Christandl, M. & Müller-Hermes, A. Fault-tolerant coding for quantum communication. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 70, 282–317 (2022).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with local gates. J. Mod. Opt. 47, 333–345 (2000).

Baspin, N., Fawzi, O. & Shayeghi, A. A lower bound on the overhead of quantum error correction in low dimensions. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.04317 (2023).

Svore, K. M., Divincenzo, D. P. & Terhal, B. M. Noise threshold for a fault-tolerant two-dimensional lattice architecture. Quantum Info Comput. 7, 297–318 (2007).

Yoder, T. J. & Kim, I. H. The surface code with a twist. Quantum 1, 2 (2017).

Chao, R. & Reichardt, B. W. Quantum error correction with only two extra qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 050502 (2018).

Chamberland, C. & Beverland, M. E. Flag fault-tolerant error correction with arbitrary distance codes. Quantum 2, 53 (2018).

Chao, R. & Reichardt, B. W. Flag fault-tolerant error correction for any stabilizer code. PRX Quantum 1, 010302 (2020).

Chao, R. & Reichardt, B. W. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with few qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 42 (2018).

Chamberland, C. & Cross, A. W. Fault-tolerant magic state preparation with flag qubits. Quantum 3, 143 (2019).

Goto, H. High-performance fault-tolerant quantum computing with many-hypercube codes. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp6388 (2024).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Gottesman, D. An introduction to quantum error correction and fault-tolerant quantum computation. In: Quantum information science and its contributions to mathematics. Proceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathematics. Vol. 68, 13–58. http://www.ams.org/books/psapm/068/ (2010).

Steane, A. M. Active stabilization, quantum computation, and quantum state synthesis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 2252–2255 (1997).

Knill, E. Scalable quantum computing in the presence of large detected-error rates. Phys. Rev. A 71, 042322 (2005).

Glancy, S., Knill, E. & Vasconcelos, H. M. Entanglement purification of any stabilizer state. Phys. Rev. A 74, 032319 (2006).

Sahay, K., Lin, Y., Huang, S., Brown, K. R. & Puri, S. Error correction of transversal CNOT gates for scalable surface code computation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.01393 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Even more efficient quantum computations of chemistry through tensor hypercontraction. PRX Quantum 2, 030305 (2021).

Yoshioka, N., Okubo, T., Suzuki, Y., Koizumi, Y. & Mizukami, W. Hunting for quantum-classical crossover in condensed matter problems. 10, 45 (2023).

Gidney, C. Stim: a fast stabilizer circuit simulator. Quantum 5, 497 (2021).

Fujitsu Limited. Specifications - Supercomputer Fugaku. https://www.fujitsu.com/global/about/innovation/fugaku/specifications/ (2018).

Wang, C., Harrington, J. & Preskill, J. Confinement-higgs transition in a disordered gauge theory and the accuracy threshold for quantum memory. Ann. Phys. 303, 31–58 (2003).

Draper, T. G. & Kutin, S. A. qpic. https://github.com/qpic/qpic (2016).

Reichardt, B. W. Fault-tolerant quantum error correction for Steane’s seven-qubit color code with few or no extra qubits. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 015007 (2020).

Acknowledgements

S.Y. was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 23KJ0734, FoPM, WINGS Program, the University of Tokyo, and DAIKIN Fellowship Program, the University of Tokyo. S.T. was supported by JST [Moonshot R&D][Grant Number JPMJMS2061], JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23KJ0521, and FoPM, WINGS Program, the University of Tokyo. H.Y. was supported by JST PRESTO Grant Number JPMJPR201A, JPMJPR23FC, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K19970, and MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT QLEAP) JPMXS0118069605, JPMXS0120351339. The quantum circuits shown in this paper are drawn using QPIC63.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y., S.T. and H.Y. contributed to the conception of the work, the analysis and interpretation in the work, and the preparation and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, S., Tamiya, S. & Yamasaki, H. Concatenate codes, save qubits. npj Quantum Inf 11, 88 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01035-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01035-8

This article is cited by

-

Fault-tolerant quantum computation with polylogarithmic time and constant space overheads

Nature Physics (2026)

-

Fault-tolerant operation and materials science with neutral atom logical qubits

npj Quantum Information (2025)