Abstract

Quantum key distribution (QKD), which promises secure key exchange between two remote parties, is now moving toward the realization of scalable and secure QKD networks (QNs). Fully connected, trusted node-free QNs have been realized based on entanglement distribution, in which the low key rate and the large overhead make their practical application challenging. Here, we experimentally demonstrate a fully connected multi-user QKD network based on a wavelength-multiplexed measurement-device-independent (MDI) QKD protocol. By combining the MDI-QKD protocol with integrated optical frequency combs, we achieve an average secure key rate of 267 bits per second for about 30 dB of link attenuation per user pair—more than three orders of magnitude higher than previous entanglement-based works. More importantly, we realize communication between two different pairs of users simultaneously. Our work paves the way for the realization of large-scale QKD networks with full connectivity and simultaneous communication capability among multiple users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum key distribution (QKD)1,2,3,4,5,6,7 allows secret key exchange between two remote parties with unconditional information security guaranteed by the laws of quantum physics. In practice, QKD implementations still deviate from the ideal description due to the imperfection of realistic devices that can open side channels for eavesdroppers8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Measurement-device-independent (MDI) QKD18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 removes all side channels on the detection side. Several efforts have been made to improve its practical performance, including long-distance26,27, high key rate28,29, and field tests30,31,32. Compared with the recent twin-field (TF) QKD33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 which can overcome the rate-distance limit, MDI-QKD requires no global phase tracking of distant sources and less phase stabilization of the optical path. Therefore, it is considered as a practical upgrade for next-generation QKD systems. Recently, chip-based MDI-QKD, including high-speed transmitter chip42,43 and on-chip untrusted relay44,45 has attracted much attention due to its scalability of device fabrication, small footprint, and low cost.

To date, various topologies of QKD networks (QNs) have been developed in large domains46,47,48,49,50,51,52. The goal of QN is to provide wide area connectivity and high key rate without compromising security. The point-to-multipoint quantum access network based on Bennett-Brassard-1984 (BB84) protocol53, allows multiple users to share receivers or sources and has been realized in configurations with passive optical splitters and active optical switches that establish a temporary quantum channel between two particular users at a time. MDI-QKD is the time-reversal of entanglement-based QKD, and it is naturally suitable for extension to multi-user star-type metropolitan QNs. In 2016, the first MDI-QN with an optical switch31 was realized, where a specific pair of users can exchange keys at the same time. Recently, a fully connected, trusted node-free QN scheme based on wavelength-multiplexed entanglement distribution has been proposed and realized54. This pioneering work has triggered the recent growing interest in combining entanglement-based Bennett-Brassard-Mermin-1992 (BBM92) QKD with classical wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) technology55,56,57. However, the low key rate as well as the large overhead makes the practical deployment and application of this scheme challenging.

In this work, we propose and experimentally demonstrate a fully connected multi-user MDI-QN where all users in the network can exchange secure keys. The novelties of our work are as follows: 1. From the protocol perspective, we go beyond the traditional point-to-point QKD architecture (including BB84, BBM92, and MDI protocols) and realize a fully connected QN without trusted nodes. Moreover, our scheme allows the experimental realization of genuine secure key distribution among different users simultaneously, which is not realized in the fully connected entanglement-based QNs54,55,56,57. 2. From the hardware perspective, we use the dissipative Kerr soliton (DKS) optical frequency comb58,59,60 generated from integrated silicon nitride (Si3N4) microring resonator (MRR) as the light source, which provides multiple highly coherent frequency lines in a wide bandwidth (~120 nm), covering the S, C, and L bands with 100 GHz frequency spacing, thus greatly reducing the resource overhead. 3. From the system performance and results perspective, we obtain an average secure key rate of 267 bps with about 30 dB of link attenuation, which is about three orders of magnitude higher than previous fully connected trusted node-free QN demonstrations54,55,56,57. More importantly, we achieve simultaneous secure key exchange between two different pairs of users with a rate of 0.1 Hz under about 30 dB of attenuation per user pair, which is not achievable in the previous fully connected entanglement-based QNs with the time-division multiplexing (TDM) method54,55,56,57.

Results

The experimental scheme

The schematic of our four-user fully connected MDI-QN is shown in Fig. 1. The link layer of the fully connected QN is formed among four users (A, B, C, D) by using six communication links. The colors of different links represent different wavelength channels (top panel of Fig. 1). The physical layer is shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 1. Each user employs a transmitter including an optical frequency comb (OFC), a wavelength demultiplexer (DEMUX), encoders, and a wavelength multiplexer (MUX) to randomly generate encoded qubits of different wavelengths. These encoded qubits are then sent over a single optical fiber to the untrusted relay server, which contains multiple DEMUXs and Bell-state measurement (BSM) modules, including beam splitters and single-photon detectors (SPDs). Our scheme can be extended to an n-user fully connected MDI-QN. If the number of users n is even (odd), we need n − 1 (n) frequency lines, which can be competently provided by a single DKS optical frequency comb with its broad frequency spectrum. At the central untrusted relay server, n(n − 1)/2 BSM modules are required. Although cryogenically cooled SPDs are resource-intensive, the recently developed waveguide-integrated superconducting SPD array45,61,62 provides an excellent solution where a single cryostat can accommodate multiple BSM modules. Compared to the entanglement-based QNs54,55,56,57, a significant amount of overhead is saved on the detection side, since each user needs SPDs along with the cryostat that are spatially separated.

At the link layer, each independent communication link establishes the correlation between two remote users using Bell-state measurement (BSM). The colors represent the wavelengths of the encoded qubits. At the physical layer, each user of the MDI-QN uses a transmitter containing an optical frequency comb (OFC), a wavelength demultiplexer (DEMUX), encoders, and a wavelength multiplexer (MUX) to randomly generate encoded qubits with different wavelengths. At the central untrusted relay server, the encoded qubits are routed by the DEMUXs to different BSM modules to establish the shared secret keys among the users in this MDI-QN.

DKS optical frequency comb

We perform a proof-of-principle demonstration of a four-user fully connected MDI-QN. The layout of our experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2. We use an integrated Si3N4 microring resonator (MRR) with a waveguide cross section of about 1.6 μm × 0.8 μm for DKS optical comb generation (Ligentec). The radius of the MRR is about 230 μm, corresponding to a free spectral range of about 100 GHz. The average Q-factor is about 1.08 × 106. As shown in Fig. 2a, two continuous-wave (CW) lasers (Pump laser and Aux laser) are amplified by erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs) and coupled to the MRR to realize a dual-driven scheme63,64,65. The Aux laser is used to balance the intracavity heat and to facilitate access to the soliton states. By carefully adjusting the frequency detuning between the pump laser and the resonance of the microresonator, the DKS optical comb is generated. The comb has a bandwidth of about 120 nm (from 1480 to 1600 nm), which almost covers the S, C, and L bands (Fig. 2b). Thanks to the dual-driven scheme and the passive isolation of the Si3N4 microresonator, the soliton state of the comb is stable for a long time, which is essential for long-term QKD applications. See Section 1 of Supplementary Information for details of the DKS comb. Each frequency line of the DKS optical frequency comb has excellent coherence and can be considered as a single CW laser in our experiment. We select three frequency lines as four-user light sources from the comb via three WDMs, corresponding to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) 100 GHz DWDM grid at channel 35 (CH35), channel 43 (CH43), and channel 59 (CH59). Then, three 10 GHz bandwidth fiber Bragg grating (FBG) filters are used to clean the frequency spectra of the comb lines (Fig. 2e–g). A 1 × 4 coupler divides each frequency line into four portions, and MUXs combine light of different wavelengths into one fiber. Several long fiber spools (2.5 km, 5 km, and 7.5 km) are used to introduce random global phase and eliminate single-photon interference (Fig. 2d).

a An integrated silicon nitride (Si3N4) microring resonator generates the DKS comb via a dual-driven scheme involving two pump lasers and a feedback loop. The insets (b, c) are the optical spectrum and the electrical beat note of the 4-soliton state acquired by an optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) and an electrical spectrum analyzer (ESA), respectively. d Three comb lines separated by WDMs act as light sources for four users. The insets (e, f, g) are the optical spectra of selected comb lines measured by the OSA. A combination of three 1 × 4 couplers and four MUXs is used to route the light of different wavelengths to the users. Each user possesses an encoder consisting of two intensity modulators (IMs) and a phase modulator (PM) that generates time-bin encoded qubits. The following variable optical attenuators (VOAs) are used to attenuate the pulses to the single-photon level and simulate channel loss. h Encoded qubits with different wavelengths are routed to different BSM modules by DEMUXs at the untrusted relay server. All photons are detected by superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs). See text for details.

MDI-QKD protocol and encoding

We use time-bin qubits to encode the bit information via modulated weak coherent pulses (Fig. 2d). Time-bin qubits are immune to random polarization rotations in fibers, making them suitable for fiber-based quantum communication. In Pauli Z basis, time-bin qubits are encoded as early, \(\left\vert e\right\rangle\) or late, \(\left\vert l\right\rangle\) for bit values of 0 or 1. In Pauli X basis, the bit values are encoded in their coherent superpositions, \(\left\vert +\right\rangle =(\left\vert e\right\rangle +\left\vert l\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\left\vert -\right\rangle =(\left\vert e\right\rangle -\left\vert l\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), representing bit values of 0 and 1, respectively. The encoder generates the time-bin qubits with a pulse duration of about 0.8 ns, and the time separation between \(\left\vert e\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert l\right\rangle\) is about 10 ns. The Z-basis qubits are used for key generation, and the X-basis qubits are used for parameter estimation. In each encoder, the first intensity modulator, IM1, carves the CW light from the DKS comb into a series of narrow pulses, and the second intensity modulator, IM2, implements the decoy-state protocol. The four-intensity decoy-state protocol66,67 has four different intensity states, one signal intensity z in Z basis and three decoy intensities y, x, o in X basis. A phase modulator (PM) applies a 0 or π phase to the later time bin for encoding the X-basis states. In this work, we load the random intensity electrical pulses sequence generated from the arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) on the modulators to encode information. The following VOAs are used to attenuate the pulses to the single-photon level and simulate channel loss.

Four-user BSM

At the four-user untrusted relay server (Fig. 2h), the encoded qubits are routed to six BSM modules depending on their wavelength. Thus, each pair of users implements BSM simultaneously and independently. The encoded qubits are projected onto the Bell state \(\left\vert {\Psi }^{-}\right\rangle =(\left\vert el\right\rangle -\left\vert le\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), using a beam splitter (BS) and two superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs). A field-programmable gate array-based coincidence logic unit with a temporal resolution of about 156 ps is used to record and analyze the photon detection signals.

Six communication links between four users are identified as AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD, respectively. To achieve high-quality BSM, qubits from different users must be indistinguishable in all degrees of freedom (DOF). For temporal DOF, three pairs of users (AB, AC, and AD) are aligned by tuning the relative delays between the electrical signals from the AWG channels. The time differences of the other three pairs (BC, BD, and CD) are compensated by precise optical fiber splicing. Polarization controllers (PCs) are used to eliminate the polarization distinguishability of photons at BSM modules. We investigate the indistinguishability of photons from different users by observing the high visibility of Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interference. The visibility of each pair of users is above 46.0% (see Section 2 of Supplementary Information for details).

After obtaining the highly indistinguishable time-bin encoded qubits, the next step is to perform BSM on them to realize MDI-QKD. The coincidence counts between two different detectors in different time bins correspond to coincidence counts between \({\left\vert e\right\rangle }_{D1}\) (D1 detects a photon in an early bin) and \({\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{D2}\) (D2 detects a photon in a late bin), or coincidence counts between \({\left\vert l\right\rangle }_{D1}\) and \({\left\vert e\right\rangle }_{D2}\). Such a coincidence detection projects two photons onto \(\left\vert {\Psi }^{-}\right\rangle\) to realize the BSM. In this process, the coherence of the light source is crucial, since a successful BSM relies on the coherent superpositions between the early and late time bins. The DKS optical comb has excellent coherent properties and is therefore well suited for this task. We show the comb states' evolution in Fig. 3a. In Fig. 3b–e, we show the HOM interference and Bell-state interference results with different comb states. Before the formation of the soliton comb, in the region of the chaotic state (indicated by green line in Fig. 3a), we obtain the low-visibility HOM interference (VHOM = 28.6% ± 0.6%) and poor-quality BSM result (VBSM = 8.8% ± 0.5%) shown in Fig. 3b, c due to the multiple frequency components and low coherence. Once the soliton state is reached, the high visibility indicates excellent coherence and shows no dependence on the number of solitons. In Fig. 3d, e, we show the high-quality results of the HOM (VHOM = 46.7% ± 0.6%) and BSM (VBSM = 45.6% ± 0.4%) for the highly coherent 4-soliton state of DKS comb. For the MDI-QKD based on two-photon interference as we performed here, the temporal separations between adjacent bins are about 10 ns, and maintaining coherence within this period is crucial. We now directly measure the linewidth of the single comb line with the delayed self-heterodyne method. In Fig. 9 of Supplementary Information, we obtain 1.4 MHz and 0.11 MHz for the chaotic state and soliton state comb lines, indicating excellent coherent property of soliton combs (see Section 6 of Supplementary Information for details).

a The power change of the frequency comb with wavelength detuning between the pump laser and the resonance of MRR, showing the evolution of the soliton steps of DKS comb. b, c The results of HOM interference (blue circles) and BSM (red circles) with chaotic state of the comb generation, indicated by the green vertical line (marked with I) in (a). d, e The results of HOM interference (blue circles) and BSM (red circles) with 4-soliton state of the comb generation, indicated by the red vertical line (marked with II) in (a). The excellent coherence of the DKS comb enables the high-visibility interference in HOM and BSM.

Key generation and simultaneous communication

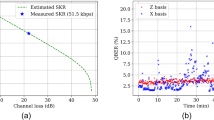

Then, we implement a four-intensity decoy-state MDI-QKD protocol among four users simultaneously in the fully connected MDI-QN. The finite-key analysis with the Chernoff bound27,67,68,69 is used. The four-intensity parameters are optimized by exploiting the joint constraints on statistical fluctuations with a failure probability of 10−10. For the total channel loss of 30 dB, the intensities of four states are z = 0.636, y = 0.204, x = 0.054, and o = 0, and the corresponding probabilities of four states are pz = 0.754, py = 0.036, px = 0.188, and po = 0.022, respectively. Details of the secure key rate analysis are provided in Section 3 of Supplementary Information. In our experiment, the MDI-QN operates simultaneously for a time duration of 8.3 h with a total of 3 × 1012 sent pulses at a clock rate of 100 MHz for each user pair. After post-processing, the secure key rate results are shown in Fig. 4. With a total loss of about 30 dB (equivalent to about 150 km of standard single-mode fiber with the propagation loss of 0.2 dB/km), the key rates between different users in our MDI-QN are shown in Fig. 4a. In Fig. 4b, we show the zoom-in view of the secure key rate results between user A and the rest of the users in the network, users B, C, D. Similar results between users B/C/D and the rest of the users are shown in Fig. 4c–e. Note that we obtain these results without using any active optical switches to change the network topology, demonstrating the advantages of a fully connected QKD network. The average user pair key rate in the MDI-QN is 267 bps, which is about three orders of magnitude higher than previous fully connected QN demonstrations54,55,56,57.

a The solid line shows theoretical simulations, and the triangular symbols show experimental results of different user pairs with a total transmission loss of about 30 dB. The top-right (b, c) and bottom-left (d, e) insets are the zoomed-in views of results for different user pairs with a linear scale.

More importantly, our fully connected QN has the capability of simultaneous communication between different users, i.e., multiple pairs of users can communicate at the same time. To achieve this goal, we extract four-fold coincidence counts from the raw key data for six pairs of users, representing that two pairs of users (AB&AC, AB&AD, AB&BC, …, BD&CD) simultaneously obtain successful \(\left\vert {\Psi }^{-}\right\rangle\) projections within the coincidence time window (1 ns). As shown in Fig. 5, the average four-fold coincidence counts (CC4−fold) are 3033 in 8.3 h at about 30 dB attenuation, corresponding to 0.1 Hz. We emphasize that this type of simultaneous communication between different pairs of users is not possible in the entanglement-based implementation of the fully connected QNs with the TDM method54,55,56,57, since in the previous works, only one pair of entangled photons was measured at a time, and thus only two-fold coincidence counts were detected.

Discussion

In this work, we have proposed and demonstrated a fully connected, trusted node-free, four-user measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution network using an integrated frequency comb for the light source. The novelties of our work can be seen by comparing our work with the well-known protocols and existing QKD networks: 1. The security of our work, especially on the detection side, is guaranteed by the MDI protocol, going beyond the traditional multi-user QKD network based on trusted nodes. 2. The system performance of our work is significantly improved, thus making a decisive step towards the realization of a practical multi-user QKD network. We obtain an average secure key rate of 267 bps with about 30 dB of link attenuation, which is about three orders of magnitude higher than previous entanglement-based demonstrations54,55,56,57. 3. Our work not only has higher key rate, but also allows practical application of QKD in a fully connected network structure, such as real-time voice telephone with one-time pad encryption48. More importantly, we achieve simultaneous secure key exchange between two different pairs of users with a rate of 0.1 Hz under about 30 dB attenuation per user pair, which is not achievable in the previous entanglement-based fully connected QNs. As to the simultaneous key exchange, we emphasize that this functionality has never been shown. One possible, yet different, exception might be quantum conference key agreement, using multiphoton states as a resource51. The simultaneous communication between multiple users will significantly improve with the increase of the system clock rate. For example, the simultaneous raw key rate of the two user pairs is on the order of 104 Hz for a 1 GHz clock rate and 10 dB channel loss. 4. Furthermore, our work has the advantage of hardware efficiency. As the light source for the users, we employ the dissipative Kerr soliton optical frequency comb, which provides abundant highly coherent light resources spanning a broad bandwidth with only two external lasers, and thus has the advantage of reducing the laser resources. Here we compare two solutions for the light source: laser or OFC. Compared with an N-user laser-based system, which requires O(N2) lasers, an OFC-based system needs only O(N) frequency-locked OFCs.

Despite these important results, there are several aspects that need to be further improved in our system: 1. Employing the independent integrated DKS comb for each user and implementing the frequency locking among individual comb frequency lines. Ideally, each user should own an independent comb as a multiple-wavelength light source. One potential difficulty is to make each comb identical in the frequency domain. To solve this, one may need frequency dissemination and high-precision frequency translation with side-band modulation, or implement Kerr-induced synchronization70. Recently, we71 and along with another group72 have realized multiple channel HOM interference, which is a firm step toward the goal of realizing MDI-QKD with independent OFCs. 2. Implementing independent secure key exchange between any pair of users by using an independent encoder for each frequency line of each user. 3. Using real fibers to replace VOAs, which simulated channel loss, and realizing network field tests under a real-world environment. The first and second points are within reach with current technology, given the rapid development of integrated photonics in recent years. For each user, integrated turnkey soliton combs73,74, whose spectrum can cover multiple communication bands, allow a large number of users to access the network. Note that all users will add an encoder when a new user is added to the network. This is the hardware requirement for a fully connected network, demanding new technology advancements. Integrated electronic circuits vastly increase processing power and reduce the size and cost of computers, and thereby enable the rapid development of the Internet and modern computing systems. Analogous to integrated electronic circuits, high-quality photonic integrated circuits will ease the burden on hardware consumption of quantum networks in the near future. Recent progress in the fabrication of wafer-scale, high-quality thin films of LN-on-insulator has made it possible to produce high-performance integrated nanophotonic modulators75 in a scalable way. We expect that these types of chip-scale, plug-and-play encoders provide excellent solutions for the upgrade and will become an important component in the QKD network. For the untrusted relay server, waveguide-integrated SNSPDs with high integrated density62 has been realized and will greatly reduce the overhead of detection. Given the rapid development of semiconductor APDs76,77, one may use the array of them at the server’s site. In our system, the clock rate is 100 MHz and the pulse width is 0.8 ns. To further enhance the performance of the system, one can increase the clock rate. The pulse width will be narrower with the increase of the clock rate. The time jitter of the pulse and the dispersion compensation in fibers need to be considered carefully. The key rate will be further doubled using time-resolved BSM45. What’s more, more pairs of simultaneous communications can be achieved by reducing the channel loss and increasing the system clock rate, which can be solved by increasing the measurable maximum count rate of the detectors, and many efforts 61,78,79,80,81,82 have been made to solve it. For the third point, many previous laboratory and field QKD implementations have provided valuable experience against environmental disturbance to field fibers. For example, a high-speed feedback system was developed for compensating polarization drifting31,34,37. And the reference-frame-independent protocol with polarization-compensation-free method83 has demonstrated the improvement of network robustness to environmental disturbances. In addition, we also propose a hardware-efficient protocol using the time-division multiplexing (TDM), as detailed in Section 5 of Supplementary Information. Users can complete the communication with a relatively simple setup and less resource consumption at the expense of a reduction in the duty cycle of the system. The performance can be enhanced by improving the clock rate and alternative protocols33,84,85,86,87,88.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bennett, C. H. & Brassard, G. Quantum cryptography: public key distribution and coin tossing. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computers, Systems, and Signal Processing 175 (Elsevier, 1984).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002).

Scarani, V. et al. The security of practical quantum key distribution. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1301–1350 (2009).

Braunstein, S. L. & Pirandola, S. Side-channel-free quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 130502 (2012).

Xu, F., Ma, X., Zhang, Q., Lo, H.-K. & Pan, J.-W. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 025002 (2020).

Pirandola, S. et al. Advances in quantum cryptography. Adv. Opt. Photonics 12, 1012–1236 (2020).

Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 661–663 (1991).

Brassard, G., Lütkenhaus, N., Mor, T. & Sanders, B. C. Limitations on practical quantum cryptography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1330 (2000).

Fung, C.-H. F., Qi, B., Tamaki, K. & Lo, H.-K. Phase-remapping attack in practical quantum-key-distribution systems. Phys. Rev. A 75, 032314 (2007).

Xu, F., Qi, B. & Lo, H.-K. Experimental demonstration of phase-remapping attack in a practical quantum key distribution system. N. J. Phys. 12, 113026 (2010).

Tang, Y.-L. et al. Source attack of decoy-state quantum key distribution using phase information. Phys. Rev. A 88, 022308 (2013).

Makarov, V., Anisimov, A. & Skaar, J. Effects of detector efficiency mismatch on security of quantum cryptosystems. Phys. Rev. A 74, 022313 (2006).

Lütkenhaus, N. Security against individual attacks for realistic quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. A 61, 052304 (2000).

Zhao, Y., Fung, C.-H. F., Qi, B., Chen, C. & Lo, H.-K. Quantum hacking: experimental demonstration of time-shift attack against practical quantum-key-distribution systems. Phys. Rev. A 78, 042333 (2008).

Gerhardt, I. et al. Full-field implementation of a perfect eavesdropper on a quantum cryptography system. Nat. Commun. 2, 1–6 (2011).

Lydersen, L., Akhlaghi, M. K., Majedi, A. H., Skaar, J. & Makarov, V. Controlling a superconducting nanowire single-photon detector using tailored bright illumination. N. J. Phys. 13, 113042 (2011).

Weier, H. et al. Quantum eavesdropping without interception: an attack exploiting the dead time of single-photon detectors. N. J. Phys. 13, 073024 (2011).

Lo, H.-K., Curty, M. & Qi, B. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 130503 (2012).

Ma, X. & Razavi, M. Alternative schemes for measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. A 86, 062319 (2012).

Da Silva, T. F. et al. Proof-of-principle demonstration of measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution using polarization qubits. Phys. Rev. A 88, 052303 (2013).

Rubenok, A., Slater, J. A., Chan, P., Lucio-Martinez, I. & Tittel, W. Real-world two-photon interference and proof-of-principle quantum key distribution immune to detector attacks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 130501 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 130502 (2013).

Liu, H. et al. Experimental demonstration of high-rate measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over asymmetric channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 160501 (2019).

Tang, Z. et al. Experimental demonstration of polarization encoding measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 190503 (2014).

Liu, J.-Y. et al. Experimental demonstration of five-intensity measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over 442 km. Phys. Rev. A 108, 022605 (2023).

Tang, Y.-L. et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over 200 km. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 190501 (2014).

Yin, H.-L. et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over a 404 km optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 190501 (2016).

Comandar, L. et al. Quantum key distribution without detector vulnerabilities using optically seeded lasers. Nat. Photon. 10, 312–315 (2016).

Woodward, R. I. et al. Gigahertz measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution using directly modulated lasers. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 58 (2021).

Tang, Y.-L. et al. Field test of measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 21, 116–122 (2015).

Tang, Y.-L. et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over untrustful metropolitan network. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011024 (2016).

Cao, Y. et al. Long-distance free-space measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 260503 (2020).

Lucamarini, M., Yuan, Z. L., Dynes, J. F. & Shields, A. J. Overcoming the rate–distance limit of quantum key distribution without quantum repeaters. Nature 557, 400–403 (2018).

Chen, J.-P. et al. Twin-field quantum key distribution over a 511 km optical fibre linking two distant metropolitan areas. Nat. Photon. 15, 570–575 (2021).

Pittaluga, M. et al. 600-km repeater-like quantum communications with dual-band stabilization. Nat. Photon. 15, 530–535 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Twin-field quantum key distribution over 830-km fibre. Nat. Photon. 16, 154–161 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Field test of twin-field quantum key distribution through sending-or-not-sending over 428 km. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 250502 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Twin-field quantum key distribution without phase locking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 250802 (2023).

Zhou, L., Lin, J., Jing, Y. & Yuan, Z. Twin-field quantum key distribution without optical frequency dissemination. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–8 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental twin-field quantum key distribution over 1000 km fiber distance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 210801 (2023).

Chen, J.-P. et al. Sending-or-not-sending with independent lasers: Secure twin-field quantum key distribution over 509 km. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 070501 (2020).

Wei, K. et al. High-speed measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution with integrated silicon photonics. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031030 (2020).

Semenenko, H. et al. Chip-based measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Optica 7, 238–242 (2020).

Cao, L. et al. Chip-based measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution using integrated silicon photonic systems. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 011001 (2020).

Zheng, X. et al. Heterogeneously integrated, superconducting silicon-photonic platform for measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Adv. Photonics 3, 055002 (2021).

Elliott, C. Building the quantum network. N. J. Phys. 4, 46–46 (2002).

Peev, M. et al. The SECOQC quantum key distribution network in Vienna. N. J. Phys. 11, 075001 (2009).

Chen, T.-Y. et al. Field test of a practical secure communication network with decoy-state quantum cryptography. Opt. Express 17, 6540–6549 (2009).

Sasaki, M. et al. Field test of quantum key distribution in the Tokyo QKD network. Opt. Express 19, 10387–10409 (2011).

Chen, Y.-A. et al. An integrated space-to-ground quantum communication network over 4,600 kilometres. Nature 589, 214–219 (2021).

Proietti, M. et al. Experimental quantum conference key agreement. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe0395 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. A fully-connected three-user quantum hyperentangled network. Quantum Front. 2, 4 (2023).

Fröhlich, B. et al. A quantum access network. Nature 501, 69–72 (2013).

Wengerowsky, S., Joshi, S. K., Steinlechner, F., Hübel, H. & Ursin, R. An entanglement-based wavelength-multiplexed quantum communication network. Nature 564, 225–228 (2018).

Joshi, S. K. et al. A trusted node-free eight-user metropolitan quantum communication network. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0959 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. 40-user fully connected entanglement-based quantum key distribution network without trusted node. PhotoniX 3, 1–15 (2022).

Wen, W. et al. Realizing an entanglement-based multiuser quantum network with integrated photonics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 024059 (2022).

Herr, T. et al. Temporal solitons in optical microresonators. Nat. Photon. 8, 145–152 (2014).

Kippenberg, T. J., Gaeta, A. L., Lipson, M. & Gorodetsky, M. L. Dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Science 361, eaan8083 (2018).

Wang, F. et al. Quantum key distribution with on-chip dissipative Kerr soliton. Laser Photonics Rev. 14, 1900190 (2020).

Beutel, F., Gehring, H., Wolff, M. A., Schuck, C. & Pernice, W. Detector-integrated on-chip qkd receiver for GHz clock rates. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 40 (2021).

Haussler, M. et al. Scaling waveguide-integrated superconducting nanowire single-photon detector solutions to large numbers of independent optical channels. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 94, 013103 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Soliton bursts and deterministic dissipative Kerr soliton generation in auxiliary-assisted microcavities. Light. Sci. Appl. 8, 50 (2019).

Lu, Z. et al. Deterministic generation and switching of dissipative Kerr soliton in a thermally controlled micro-resonator. AIP Adv. 9, 025314 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Sub-milliwatt-level microresonator solitons with extended access range using an auxiliary laser. Optica 6, 206–212 (2019).

Zhou, Y.-H., Yu, Z.-W. & Wang, X.-B. Making the decoy-state measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution practically useful. Phys. Rev. A 93, 042324 (2016).

Jiang, C., Yu, Z.-W., Hu, X.-L. & Wang, X.-B. Higher key rate of measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution through joint data processing. Phys. Rev. A 103, 012402 (2021).

Curty, M. et al. Finite-key analysis for measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–7 (2014).

Zhang, Z., Zhao, Q., Razavi, M. & Ma, X. Improved key-rate bounds for practical decoy-state quantum-key-distribution systems. Phys. Rev. A 95, 012333 (2017).

Moille, G. et al. Kerr-induced synchronization of a cavity soliton to an optical reference. Nature 624, 267–274 (2023).

Yan, W. et al. Ten-channel Hong–Ou–Mandel interference between independent optical combs. Chin. Opt. Lett. 23, 042701 (2025).

Huang, L. et al. Massively parallel Hong-Ou-Mandel interference based on independent soliton microcombs. Sci. Adv. 11, eadq8982 (2025).

Stern, B., Ji, X., Okawachi, Y., Gaeta, A. L. & Lipson, M. Battery-operated integrated frequency comb generator. Nature 562, 401–405 (2018).

Shen, B. et al. Integrated turnkey soliton microcombs. Nature 582, 365–369 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Comandar, L. C. et al. Gigahertz-gated InGaAs/InP single-photon detector with detection efficiency exceeding 55% at 1550 nm. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 083109 (2015).

Yan, Z., Shi, T., Fan, Y., Zhou, L. & Yuan, Z. Compact InGaAs/InP single-photon detector module with ultra-narrowband interference circuits. Adv. Dev. Instrum. 4, 0029 (2023).

Münzberg, J. et al. Superconducting nanowire single-photon detector implemented in a 2D photonic crystal cavity. Optica 5, 658–665 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. A 16-pixel interleaved superconducting nanowire single-photon detector array with a maximum count rate exceeding 1.5 GHz. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 29, 1–4 (2019).

Rambo, T. M., Conover, A. R. & Miller, A. J. 16-element superconducting nanowire single-photon detector for gigahertz counting at 1550-nm. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14086 (2021).

Li, W. et al. High-rate quantum key distribution exceeding 110 Mb s−1. Nat. Photon. 17, 416–421 (2023).

Grünenfelder, F. et al. Fast single-photon detectors and real-time key distillation enable high secret-key-rate quantum key distribution systems. Nat. Photon. 17, 422–426 (2023).

Fan-Yuan, G.-J. et al. Robust and adaptable quantum key distribution network without trusted nodes. Optica 9, 812–823 (2022).

Ma, X., Zeng, P. & Zhou, H. Phase-matching quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031043 (2018).

Zeng, P., Zhou, H., Wu, W. & Ma, X. Mode-pairing quantum key distribution. Nat. Commun. 13, 3903 (2022).

Zhu, H. T. et al. Experimental mode-pairing measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution without global phase locking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 030801 (2023).

Xie, Y.-M. et al. Breaking the rate-loss bound of quantum key distribution with asynchronous two-photon interference. PRX Quantum 3, 020315 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Experimental quantum communication overcomes the rate-loss limit without global phase tracking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 250801 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants No. 2022YFE0137000 and 2019YFA0308704), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grants No. BK20240006 and BK20233001), the Leading-Edge Technology Program of Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. BK20192001), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grants No. 2021ZD0300700 and 2021ZD0301500), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grants No. 2024300324), and the Nanjing University-China Mobile Communications Group Co., Ltd. Joint Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y., X.Z., W.W., L.L., and X.-S.M. designed the experiment. W.Y., X.Z., W.W., Y.D., and X.-S.M. performed the experiment. W.Y., X.Z., and X.-S.M. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. S.Z., Y.L., and X.-S.M. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41534_2025_1052_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information: A measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution network using optical frequency comb

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, W., Zheng, X., Wen, W. et al. A measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution network using optical frequency comb. npj Quantum Inf 11, 97 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01052-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01052-7

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive multi-party quantum key exchange in dynamic networks using GHZ states

Quantum Information Processing (2025)