Abstract

Unmanned vehicles (UV) demand highly secure communication system with high-cost-effectiveness. Bypassing the use of quantum coherent source and active modulations, passive-state-preparation (PSP) continuous-variable quantum key distribution (CVQKD) with thermal source provides a favorable solution for all-day cryptography communication between UVs. However, the field experiment of free-space PSP CVQKD has still not been realized due to the lack of efficient excess noise suppression techniques via high-loss free-space channels. Here, we realize the PSP CVQKD field test over an urban free-space channel with record-breaking attenuation from −12.24 dB to −15.59 dB. Specifically, a novel scheme is proposed to reduce excess noise from PSP, and efficient quantum coherence detection alongside advanced digital signal processing algorithms is developed to achieve low-noise synchronized raw data acquisition. The secure keys are successfully generated, with statistical summation values of 0.85 kbps during the day and 1.52 kbps at night, proving the viability for UV secure communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

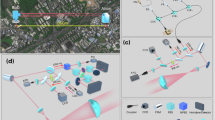

The applications of unmanned vehicles (UVs), including unmanned ground vehicle (UGV), unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), and unmanned surface vehicle (USV), have grown exceptionally due to their mobility and flexibility in networking and formation recently. However, data and control communications between UVs and the control station through wireless channels, which are remotely operated by a human operator or autonomously operated by an onboard computer system, impose great vulnerabilities to various attacks1,2,3. Moreover, the practical application of unmanned vehicles quite restricts the onboard security performance of the communication system, which needs to meet the requirements of simple structure, high integration, super environmental adaptability, and even low cost. The security of UVs has become a critical concern, which has garnered significant attention in recent years4,5,6,7.

Quantum key distribution (QKD)8,9,10,11,12 can distribute random keys with information-theoretical security for remote parties via untrusted channels, which includes two implementation directions, i.e., the discrete-variable QKD (DVQKD) and continuous-variable QKD (CVQKD) schemes. The cryptography communication based on free-space QKD provides an information-theoretically secure solution for UV networking and formation. Nowadays, free-space DVQKD has been widely studied due to its advantages in ultra-long-distance secure communications13,14,15,16. While CVQKD can implement high-key-rate, high-integration, and low-cost communication over relatively lower transmission loss17,18,19 but can achieve strong resistance to background light noise fundamentally due to the use of quantum coherent detections20,21. Several studies on key techniques and experimental demonstrations have also been conducted recently on free-space CVQKD21,22,22,23,24,25,26. However, the previous CVQKD trials all relied on active protocols such as Gaussian-modulated coherent states (GMCS) or Stokes operator coding protocols. For active CVQKD protocol, the modulated quantum states are always prepared actively by using amplitude and phase modulators, and achieving high-speed linear modulation with a high extinction ratio and stability under practical conditions is challenging, especially in integration design. Moreover, in active CVQKD protocol, high-speed on-chip modulators significantly increase costs, manufacturing time, and implementation complexity27, which can not fully meet the requirements of UV secure communications.

To overcome the challenges of traditional GMCS CVQKD with active modulation, B. Qi et al. proposed the passive-state-preparation (PSP) CVQKD protocol using a thermal source in 201828. Since the avoidance of quantum coherent sources and active modulations and the feasibility of secure key generation over metro-area distances27, the PSP CVQKD protocol has shown great potential in QKD networks29,30,31. Recently, F. Ji et al. realized a PSP CVQKD experiment with a 1.09 Gbps key rate32, further demonstrating the potential of the PSP CVQKD protocol in achieving high-key-rate systems. Due to its high resistance to background noise, impressive bit rate capabilities, and low power consumption, the PSP CVQKD system is particularly well-suited for secure communication onboard UVs. However, the above PSP CVQKD experiments are conducted in a laboratory, where the channel complexity is significantly lower than in the field. And all demonstrations of drone-based QKD rely on the active QKD protocol33,34,35. There is still a gap in field trials conducted in free-space channels, primarily due to the absence of effective excess noise suppression techniques via high-loss real free-space channels.

In this article, we conduct a PSP CVQKD field trial for the first time over an urban free-space channel with attenuation from −12.24 dB to −15.59 dB between two buildings during daylight and night. Specifically, we propose an experimental scheme to greatly suppress the excess noise caused by PSP and develop high-efficiency homodyne detection and data sampling to realize shot-noise-limited detection and raw key data acquisition in a high-attenuation environment. Moreover, a machine learning-based modulation-free phase compensation is proposed, and a high-precision acquisition, pointing, and tracking (APT) system is employed, further suppressing the excess noise due to quantum state distortion in transmission and ensuring highly secure key generation rates via fluctuating free-space channels. The results show that the day and night statistical summation secure key rates (SKR) can be generated with 0.85 kbps and 1.52 kbps, respectively. This work demonstrates the feasibility of the all-day PSP CVQKD, which further presents a promising solution for the UV secure communication system based on the superior merits of cost-effectiveness, integration, and adaptability.

Results

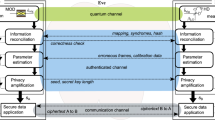

The protocol and its security

In PSP CVQKD, the secure key is generated by utilizing the intrinsic field fluctuations of a thermal source. In this protocol, as shown in Fig. 1, Alice splits the output signal of a thermal source into two spatial modes using a beam splitter (BS). One mode {x1, p1} is sent to Bob after passing through a VOA, while the other mode {xA, pA} is measured locally by Alice using heterodyne detection. Since Alice cannot acquire the information about the quantum signal directly, she must obtain her optimal estimation of the outgoing mode28 from her local measurement results. The modulation variance VA depends on the source intensity, the splitting ratio of the first BS, and the optical attenuation. Bob then demultiplexes the local oscillator (LO) and quantum signals from the received signal using the PBS and performs heterodyne detection to obtain the quadratures xB and pB. Alice and Bob further estimate the parameters using a subset of their correlation data through an unreliable classical channel. To utilize the thermal source efficiently, we replace the balanced BS with an unbalanced BS with a suitable splitting ratio and renew the excess noise model due to passive-state preparation (see Methods for more details). The mutual information between Alice and Bob is affected by the uncertainties derived from Alice’s estimation of the outgoing mode, which can be described as additive excess noise. From the receiver’s view (Eve, Bob), she cannot distinguish the quantum state prepared in PSP CVQKD from the one in traditional GMCS CVQKD27, so is the information that Eve could gain from Bob’s measurement results. Therefore, the security of the PSP CVQKD protocol is guaranteed by its equivalence to both the GMCS QKD and the entanglement-based (EB) CV-QKD protocols. We can apply the standard security proof for traditional GMCS CVQKD to calculate the SKR according to the excess noise. In this paper, the SKR in asymptotic regime is calculated as

where f is the equivalent repetition rate, i.e., the bandwidth of the homodyne detector; PRD is the proportion of revealed data due to digital signal processing (DSP); FER is the frame error rate of the reconciliation step; β is the efficiency of the reconciliation step; IAB is the Shannon mutual information between Alice and Bob; χBE is the Holevo bound between Eve and Bob (see Supplementary Information, Note 1). In practice, it is difficult to prepare a single mode thermal state and match its spectral-temporal mode with the LO. Therefore, a narrow bandpass filter, a polarizer, and an ultra-narrow linewidth CW laser source are employed in this work to get a single mode thermal state and mitigate the risks associated with multi-photon states.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup of the PSP CVQKD system is shown in Fig. 2, where Alice, Bob, and the mirror are positioned at points A, B, and C, respectively. Alice and Bob have to be placed in the same position to get synchronous sample data (see Supplementary Information, Note 2). To get the secure key via an urban free-space channel, we propose an experimental scheme that greatly suppresses the excess noise caused by PSP. This scheme involves developing high-efficiency homodyne detection and data sampling in order to realise shot-noise-limited detection and raw key data acquisition in a high-attenuation environment. Furthermore, we propose the use of a machine learning-based, modulation-free phase compensation method and a high-precision APT system to suppress excess noise due to quantum state distortion in transmission. These system optimisations have significantly reduced total excess noise and increased the maximum tolerable channel attenuation, enabling secure key generation.

a The optical layout and transmitter at Alice’s station; b The optical layout and receiver at Bob’s station; c The mirror. Alice sends a polarization multiplexing light to Bob through a free-space channel. The channel comprises an APT system and a mirror, which aim to place Alice and Bob together to get synchronous sample data. The red, blue, and yellow fibers denote quantum signal, LO, and polarization multiplexing signal, respectively. ASE amplified spontaneous emission, VOA variable optical attenuator, EDFA Er-Doped fiber amplifier, BPF bandpass filter, POL polarizer, PC polarization controller, PMBS polarization maintaining beam splitter, Pow power meter.

On Alice’s side, a commercial amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source (Golight) is utilized as the quantum signal generator, and the broadband thermal light is amplified by an EDFA up to 34.5 dBm. Specifically, the EDFA will not affect the properties of thermal light, so the output can be regarded as an ideal thermal source (see Supplementary Information, Note 3). To reduce the ASE noise and to get a single mode, a 0.4 nm optical bandpass filter is placed after the EDFA with 1550.12 nm central wavelength. Finally, a fiber-pigtailed polarizer is placed after the light source to get a single polarization mode. A polarization controller is employed to ensure the polarization aligns at the following polarization-maintaining beam splitters (PMBS). A CW laser source (NKT Koheras BASIK X15) centered at 1550.12 nm with 100 Hz line width is employed as LO, utilized in the heterodyne detection systems for Alice’s and Bob’s. A PMBS with a 99:1 splitting ratio is used to split the LO, where the weaker mode is sent to Bob to reduce the leakage noise. An unbalanced BS with a 90:10 splitting ratio is utilized to split the thermal state to use the thermal source and reduce the PSP noise efficiently. The weaker mode is modulated with a VOA to get an appropriate equivalent modulation variance and sent to Bob with LO by polarization multiplexing through PBS, while the other mode is measured locally by Alice with heterodyne detection. Here, a 90° optical hybrid (Optoplex) and two balanced homodyne detectors (Thorlabs PDB435AC) are used to implement the heterodyne detection.

On Bob’s side, after passing through a 280 m free-space channel with attenuation from −12.24 dB to −15.59 dB, the spatial light is coupled to the fiber and split by a 99:1 BS. The weaker output is followed by a homodyne detector (Thorlabs PDB435C) that quantifies and records the optical power received by Bob to track changes in channel transmittance. An MPC-201 follows the other output to adjust the polarization manually, and the feedback is provided by monitoring the light intensity of 1% quantum signal after PBS with a high extinction ratio through an optical power meter. To minimize the leakage noise, the polarization controller is adjusted until the power meter’s output is less than −70 dBm, i.e., the lowest signal power that can be detected by the power meter. Due to the significant attenuation in the free-space channel, the LO intensity at the receiver is too weak to reach the shot noise limit. After the received signal is separated into LO and quantum signal by PBS, an EDFA is placed after the LO to amplify the LO signal to reach the shot noise limit. To reduce ASE noise derived from EDFA, a bandpass filter with a central wavelength of 1550.12 nm is employed36.

In our experiment, the data are acquired synchronously by an oscilloscope. During the experiment, the block length is limited by the oscilloscope’s maximum memory and the channel character. Specifically, a 20 GHz bandwidth real-time oscilloscope is employed to over-sample the outputs of Alice’s and Bob’s balanced homodyne detectors with 350 MHz bandwidth. We chose a 200 microseconds detection window and performed a 10 GHz sample rate oversampling on the output signal of the homodyne detector. The shot noise is fixed before the experiment, and the real-time shot noise is revised according to the intensity of the received LO. After Alice and Bob share correlated raw data, the DSP algorithms, including digital filter, frame synchronization, and phase compensation, are employed to directly correlate the sampling points between Alice and Bob and decrease the excess noise. Specifically, precise frame synchronization and phase compensation are necessary for Alice and Bob to generate the final key. Here, a machine learning-based modulation-free phase compensation scheme is proposed to suppress the excess noise of the PSP CVQKD system (see Methods for more details).

The impact of the multiple atmospheric effects mentioned above on the system can be summarized as fluctuations in transmittance and additional excess noise. To maintain coupling efficiency stability in the face of transmittance fluctuations, a high-precision APT system is employed. To suppress the excess noise introduced by the atmospheric effects, we monitor and control the polarization change in real time on Bob’s side and use a machine learning-based phase recovery algorithm to suppress the leakage noise and phase noise. The channel is created between two roofs of the laboratory buildings to get a real urban free-space channel. Alice and Bob are placed on one roof, and the output beam of the transmitter is reflected by a mirror placed on the other roof 140 meters away. In the transmitter, we use a reflective telescope with an aperture of 125 mm to narrow the beam divergence up to 3 mrad, and the receiver uses a telescope with an aperture of 250 mm. A high-precision APT system is integrated at the transmitter and receiver to achieve the best coupling efficiency. In the coarse pointing stage, the transmitter and the receiver send their beacon lasers to each other, and the transmitter and the receiver use a 671 nm red laser and 532 nm green laser as beacon lights, respectively. They will adjust their pointing direction until the other coarse tracking camera can pick up the beacon beam spots. In the fine-pointing stage, the transmitter will send an intense laser beam centered at 1550.12 nm and adjust its pointing direction according to the feedback that the power of the received signal is measured by an optical power meter. After establishing the optimal link, the APT system will keep the link stable through automatic fine tracking. In most cases the APT system performs well and maintains a high transmission. However, due to the unavoidable fluctuation of transmission, it is necessary to re-align the link hourly based on the optical power received at Bob’s station. With the support of these technologies, the APT system can achieve a coupling efficiency of 11.84% (see Supplementary Information, Note 4).

Excess noise suppression

The suppression of excess noise is the key to get the secure key. We will comprehensively introduce the excess noise suppression method in the system and quantify each noise component. Firstly, the excess noise model of the free-space PSP-CVQKD scheme is constructed as follows:

where \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{psp}}},{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{phase}}},{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{leak}}},{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{fad}}},{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{back}}},{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{res}}}\) denotes the excess noises caused by passive-state-preparation, imperfection in phase compensation, polarization leakage, fluctuating transmittance of the fading channel, background noise, and other residual noise, respectively. We will give a complete excess noise analysis, and each component will be quantified.

The PSP noise εpsp significantly limits the performance of PSP CVQKD systems. Here, we analyzed the impact of the BS splitting ratio on the system and utilized the unbalanced BS to replace the balanced BS27,28,29,30,31,32. We analyze the effect of transmittance η1 on PSP noise while changing η1 to keep the equivalent modulation variance constant. It can be observed in Fig. 3a that reducing the transmittance of BS η1 can decrease excess noise εpsp while keeping the equivalent modulation variance unchanged. Moreover, the influence of different thermal source intensities on εpsp is analyzed, where the dashed blue lines and the orange line represent cases where the stronger ASE source is 3dB greater than the weaker one. Obviously, under the same conditions, the weaker of the thermal source, the higher the intensity of the εpsp in the system, and εpsp could be reduced to an acceptable level by adjusting the transmittance η1, which demonstrates the feasibility of PSP CVQKD system with weak ASE source. During the experiment, to minimize the PSP noise, we adjust the transmittance of the first BS η1 from 0.5 to 0.1 and set the modulation variance to 14, and the final PSP noise of the system is suppressed to 0.005 according to evaluation with Equation (9).

a The excess noise due to PSP with strong thermel source (red line) and weak thermel source (blue dashed line). The options for η1 in different is also marked (black dashed line). b The excess noise due to polarization leakage (blue line) and the intensity of LO in the experiment (black dashed line). c The excess noise due to imperfect phase compensation, where the left and right panel denotes the phase noise during daytime and nighttime, respectively. d The excess noise due to the fading channel, where the left and right panel denotes the fading noise during daytime and nighttime, respectively.

To optimize the equivalent modulation variance, the average photon number of a thermal state must be decreased to low intensity, which is easily affected by the leakage light of the strong LO. However, a strong LO is necessary for a CVQKD system to achieve the shot noise limit. In our experiment, a PBS with high isolation is used to reduce the intensity of the leakage LO light; an EDFA placed on Bob’s side is used to amplify the LO intensity, which reduces the demand for sending LO intensity to less than −10dBm. Here, since the measured signal is continuous, we modify the leakage noise formula according to the temporal modes of continuous-mode states37. The leakage noise is calculated by

where 〈NLO〉 is the average photon number of LO sent by Alice; R is the extinction ratio of the optical system; Δt is the integral time of ADC. As shown in Fig. 3b, the leakage noise in the experiment can be suppressed to 0.018 SNU.

Quantum signal transmission through free-space channels inevitably introduces phase changes, directly affecting the result of coherent detection. We evaluate the residual phase noise that cannot be compensated. Our phase compensation algorithm compensates the signal in blocks and the phase change within each block varies. In the Gaussian-modulated coherent-state protocol, the excess noise due to the residual phase noise at the receiver side can be expressed as38:

where T is the transmittance, including the quantum channel and the detector efficiency; VA is the equivalent modulation variance; Vphase is the variance of the residual phase. We randomly selected multiple blocks and calculated their residual phase noise, and the results are shown in Fig. 3c.

A fading channel is where the transmittance varies over time due to effects such as atmospheric turbulence and scattering. Compared to a stable channel, the fading channel introduces additional excess noise, which is given by

where \(Var(\sqrt{\eta })=\langle \eta \rangle -{\langle \sqrt{\eta }\rangle }^{2}\) and VA is the equivalent modulation variance of Alice39. We calculated the system’s fading noise εfad by randomly selecting a 200 μs section, the same as the block length, and calculating its εfad. The analysis results shown in Fig. 3d indicate that the fading noise of the system during the day is higher than during the night. εfad is less than 0.005 SNU in most cases, further demonstrating that the channel transmittance is almost constant within a data block.

Background noise refers to the interference caused by various non-target light sources, especially sunlight. To reduce background noise, a narrow bandpass filter with 1550.12 nm central wavelength was installed at the receiver, and the receiver’s telescope structure was also designed only to receive direct parallel light. Moreover, the ultra-narrow linewidth CW laser used in coherent detection acts as a filter, which further suppress the background noise. However, there was still background noise even after blocking all possible direct sunlight. We observed that the system experiences significant excess noise during two time windows from 8:00 AM to 9:00 AM and 11:30 AM to 1:00 PM, making it impossible to generate secure keys. During the first time window, the CVQKD system is affected by direct sunlight resulting in high background noise. For the second time window, the excess noise is mainly derived from the severe scattering effect of the ground atmosphere. As the sunlight intensifies, the background noise caused by scattering from different objects on the ground increases.

There are other residual noises \({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{res}}}\) in the system, including excess noise due to mode mismatch27, ADC quantization noise40 and so on. The residual noise is so small that it can be ignored.

Experimental results

We performed multiple QKD runs in April and May 2024, including nighttime and daytime, to exploit the ability of the PSP CVQKD system to resist background noise. To account for the impact of the fluctuated channel on the system, we performed an average summation of each data block’s SKR to obtain the system’s average key rate. Suppose that the i-th experiment collected M blocks of data, of which m blocks can obtain a secure key. The statistical summation SKR Ri is calculated according to the SKR of the data block Rn derived from Equation (1) and the proportion of valid block, i.e., the data block that can generate a secure key, Pi = m/M, which can be expressed as

Therefore, we can calculate the statistical summation SKR for each experiment and obtain the average SKR of the system by taking the mean values, which allows us to take the stability of the system into account.

The settings of the key parameters of the experiment are shown in Table 1. Due to the influence of fluctuation in transmittance on the parameters, the table displays the mean values of the SNR and the electrical noise vel calculated under multiple sets of different transmittance data. On May 6th, 8th, and 9th, we performed several QKD experiments at night from 10:00 PM to 2:00 AM. On May 16, 17 and 18, we performed several QKD experiments during the day from 6:00 AM to 1:00 PM. The statistical results of each experimental result are shown in Table 2 to reflect the overall performance of the system, and the SKR and excess noise for each set of data is calculated separately as shown in Fig. 4 (see Supplementary Information, Note 5). The average channel attenuation of the valid data during day and night is −14.23 dB and −14.38 dB, respectively. The channel attenuation mainly consists of a −9.28 dB APT coupling efficiency and additional coupling efficiency vibration due to several atmospheric effects.

The receiver of our CVQKD system is designed primarily to avoid solar background noise through its physical structure and a bandpass filter with 1550 nm central wavelength. Moreover, the coherent detection acts as a 1550.12 nm narrow bandpass filter, so the impact of the background noise on the system is minimal most of the time. However, the statistical summation SKR is 0.85 kbps and 1.52 kbps during the day and night, respectively, which means the stability of the CVQKD system is significantly different. During the daytime, higher temperatures cause stronger turbulence in the atmospheric channel and mechanical vibration caused by various activities, such as vehicles passing by, resulting in channel instability and lower coupling efficiency (see Supplementary Information, Note 6), which leads to a decline in CVQKD system performance.

Discussion

We propose and experimentally realize a PSP CVQKD scheme towards UV secure communication for the first time over an urban free-space channel. Secure keys are successfully generated by optimizing the scheme to reduce PSP noise, developing coherent detection and DSP, and employing a high-precision APT system. The final SKR is generated with statistical summation values of 0.85 kbps and 1.52 kbps at daytime and nighttime, respectively. The experimental demonstrations of QKD in onboard UV communication systems have successfully validated the fundamental principles of secure communication under urban field conditions. It should be mentioned here that the experiment is a proof-of-principle demonstration for the onboard UV quantum secure communication system, so the optical experimental setups in Alice’s and Bob’s sides are not yet assembled with considerations of integration and miniaturization. Deploying a quantum secure communication system requires integrating terminals, which involve integrating the optical path and the APT system. Firstly, a miniaturized APT system must be implemented to ensure stable alignment in dynamic scenarios. Encouragingly, previous studies33,34,35 have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of drone-based QKD systems, paving the way for mobile APT solutions. Secondly, a compact, integrated QKD optical system is essential for scalability and robustness. Recent advances18,41,42 have achieved chip-based QKD implementations, and the PSP QKD system has a simpler architecture than other schemes. This makes it particularly well-suited to further miniaturization into integrated photonic chips. These developments pave the way for a fully functional UV quantum communication terminal in the near future.

A complete quantum secure communication scheme includes the QKD part and the one-time pad (OTP) encryption procedure. As shown in Fig. 5, the scheme consists of the following key steps. Firstly, Alice (control station) and Bob (UVs) get a string of shared secure keys K through the above PSP-CVQKD scheme. Then Alice encrypts the sensitive data, i.e., the plaintext through a bitwise XOR operation with the pre-shared keys, generating the ciphertext. This encrypted payload is then transmitted to Bob via the classical channel. Upon reception, Bob decrypts the message by reapplying the identical XOR operation using the shared secret keys, thereby recovering the original plaintext with information-theoretic security. It should be noted that in the above process, Eve can eavesdrop on both quantum and classical channels. However, the inherent unconditional security of PSP-CVQKD guarantees that Eve can not capture the secret key information. While the information-theoretic security of OTP also ensures confidentiality even against quantum computing threats. So the unconditional security of whole quantum secure communication between the unmanned vehicles can be realized.

The practical deployment of such systems requires addressing several critical challenges inherent in real-world operational environments, which could be further improved in the following studies. For the block length limitation caused by the maximum memory of the oscilloscope, a custom data acquisition card (DAQ) with more memory can be used instead of the oscilloscope to collect data. With the block length increase, the cost of frame synchronization and the finite-size effects will be mitigated, and the result with a larger block length can help us better acquire the characteristic information of the free-space channel. Furthermore, if there are two synchronized DAQs, the mirror in the middle of the channel is no longer needed, which can greatly improve the performance and stability of our CVQKD system. The optical circuit can be further optimized to realize an integrated optical module, which could reduce the excess noise introduced by internal system instability. Developing the transmitted LO (TLO) scheme can further reduce the excess noise introduced by LO leakage and improve system performance while reducing the actual security vulnerabilities of the system. Moreover, to suppress the background noise caused by direct sunlight and the scattering from the object on the ground, the receiver should avoid facing the sun and use a high-elevation angle43. Moreover, different UV platforms impose relatively distinct requirements on QKD systems. For instance, the UAV is a lightweight aerospace platform where low-cost QKD devices and miniaturized APT systems are the top priority. Unmanned surface vehicles (USV) demand more robust QKD devices and high-performance APT systems to ensure stable free-space optical links over long-distance ocean surfaces. The following work may focus on developing these specific platforms by further mitigating state distortion, adapting parameters in real-time, and customizing component configurations to achieve high-performance secure communication across diverse deployment environments.

Methods

Optimized PSP noise model

In previous studies27,28,29,30,31,32, a 50:50 BS was commonly utilized to divide the thermal state into two identical modes for experimental and analytical purposes. To suppress the PSP noise and efficiently use the thermal source, we replace the balanced BS with an unbalanced BS and give a more universal noise model. For simplicity, only the X quadrature is considered, and the P quadrature can be analyzed similarly. As shown in 1, the X quadrature of the optical-mode output from Alice x1 is given by

where η0 is the transmittance of the VOA; η1 is the transmittance of the BS1; xv1 and xv3 is the X quadrature of the vacuum mode introduced by BS1 and the VOA respectively. The X quadrature of the optical-mode detected by Alice is given by

where ηax is the transmittance of the equivalent optical attenuator of the homodyne detector, known as the efficiency of the detector; Eax is the noise of the homodyne detector; xv2 and xv3 is the X quadrature of the vacuum mode introduced by BS2 and the homodyne detector. So Alice’s optimal estimation of x1 is \({\hat{x}}_{{\rm{A}}}={\alpha }_{{\rm{0}}}{x}_{{\rm{A}}}\), where \({\alpha }_{0}=\frac{\langle {x}_{{\rm{1}}}{x}_{{\rm{A}}}\rangle }{\langle {x}_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}\rangle }\)27,28,44. Note that the variance of the quadratures of the vacuum mode is defined as shot noise units, which means each noise component is normalized by shot noise and \(\langle {x}_{{\rm{v1}}}^{2}\rangle =\langle {x}_{{\rm{v2}}}^{2}\rangle =\langle {x}_{{\rm{v3}}}^{2}\rangle =\langle {x}_{{\rm{v4}}}^{2}\rangle =1\). Hence, Alice’s uncertainty about the outgoing mode is given by

where VA = η0n0 is the equivalent modulation variance of the mode sent to Bob; ηa and va are the efficiency and noise variance of Alice’s detector, respectively. The PSP noise can be calculated by εPSP = Δ − 1.

Frame synchronization and phase compensation

After heterodyne detection, Alice and Bob share a set of correlated raw data. For the common DSP algorithms of CVQKD22,24, the frame synchronization and phase compensation between Alice and Bob are performed using the added training frames. Here, we used a fine-grained frame synchronization and machine learning-based modulation-free phase compensation algorithm to obtain the raw data. The frame synchronization method is implemented using only Alice segment measurement results. Firstly, Alice reveals a segment of her measurement results to Bob through a classical channel. After receiving Alice’s measurement results, Bob performs a sliding cross-correlation calculation between the received data and his own, obtaining a set of cross-correlation sequences. Then, Bob compares the maximum value of the cross-correlation sequence with a precalibrated threshold. If the value exceeds the threshold, it indicates that frame synchronization is successful and the synchronization sequence is obtained.

The RNN model is employed in the phase compensation algorithm to capture temporal dependencies between phase shifts, using the past data to predict future phase values. The model training is performed using the phase-drift data acquired from measurement results. Alice and Bob processed a synchronization sequence using a sliding window and generate a series of phase data slices. For each slice, half of the data points are used as input to the RNN model, and the predicted values are used for phase compensation of the next data point. During the training process, 70% of the data slices are used as the training set to optimize the parameters of the RNN network, the remaining data is used as the test set for evaluating the performance of the RNN network after training. In the prediction stage, Alice and Bob first obtain synchronized data through a frame synchronization algorithm and then divide the synchronized data into small segments. For each segment, Bob reveals half of the data to assist Alice in calculating the phase shift, resulting in a sequence of phase shift data. Then, Bob uses the RNN model to input this phase shift data and predict the phase shifts used to perform phase compensation for the unrevealed data. Compared to previous phase recovery algorithms, the new algorithm provides higher phase compensation accuracy and can further suppress the excess noise due to phase drifts in the system (see Supplementary Information, Note 7).

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Dawy, Z., Saad, W., Ghosh, A., Andrews, J. G. & Yaacoub, E. Toward massive machine type cellular communications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 24, 120–128 (2016).

Sun, X., Ng, D. W. K., Ding, Z., Xu, Y. & Zhong, Z. Physical layer security in uav systems: challenges and opportunities. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 26, 40–47 (2019).

Zeng, Y., Zhang, R. & Lim, T. J. Wireless communications with unmanned aerial vehicles: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 54, 36–42 (2016).

Alshaer, N., Moawad, A. & Ismail, T. Reliability and security analysis of an entanglement-based qkd protocol in a dynamic ground-to-uav fso communications system. IEEE Access 9, 168052–168067 (2021).

Alshaer, N. & Ismail, T. Performance evaluation and security analysis of uav-based fso/cv-qkd system employing dp-qpsk/cd. IEEE Photonics J. 14, 1–11 (2022).

Sedjelmaci, H., Senouci, S. M. & Ansari, N. Intrusion detection and ejection framework against lethal attacks in uav-aided networks: A bayesian game-theoretic methodology. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 18, 1143–1153 (2016).

Granjal, J., Monteiro, E. & Silva, J. S. Security in the integration of low-power wireless sensor networks with the internet: a survey. Ad Hoc Netw. 24, 264–287 (2015).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145 (2002).

Grosshans, F. & Grangier, P. Continuous variable quantum cryptography using coherent states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 057902 (2002).

Grosshans, F. et al. Quantum key distribution using Gaussian-modulated coherent states. Nature 421, 238–241 (2003).

Shor, P. W. & Preskill, J. Simple proof of security of the bb84 quantum key distribution protocol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 441 (2000).

Lo, H.-K. & Chau, H. F. Unconditional security of quantum key distribution over arbitrarily long distances. science 283, 2050–2056 (1999).

Liao, S.-K. et al. Satellite-to-ground quantum key distribution. Nature 549, 43–47 (2017).

Liao, S.-K. et al. Space-to-ground quantum key distribution using a small-sized payload on tiangong-2 space lab. Chin. Phys. Lett. 34, 090302 (2017).

Bedington, R., Arrazola, J. M. & Ling, A. Progress in satellite quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 30 (2017).

Agnesi, C. et al. Exploring the boundaries of quantum mechanics: advances in satellite quantum communications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20170461 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Chen, C., Zhuang, Q., Wong, F. N. & Shapiro, J. H. Experimental quantum key distribution at 1.3 gigabit-per-second secret-key rate over a 10 db loss channel. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 025007 (2018).

Zhang, G. et al. An integrated silicon photonic chip platform for continuous-variable quantum key distribution. Nat. Photonics 13, 839–842 (2019).

Guo, H., Li, Z., Yu, S. & Zhang, Y. Toward practical quantum key distribution using telecom components. Fundam. Res. 1, 96–98 (2021).

Wang, S., Huang, P., Wang, T. & Zeng, G. Atmospheric effects on continuous-variable quantum key distribution. N. J. Phys. 20, 083037 (2018).

Wang, S., Huang, P., Wang, T. & Zeng, G. Feasibility of all-day quantum communication with coherent detection. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 024041 (2019).

Usenko, V. C. et al. Stabilization of transmittance fluctuations caused by beam wandering in continuous-variable quantum communication over free-space atmospheric channels. Opt. Express 26, 31106–31115 (2018).

Shen, S.-Y. et al. Free-space continuous-variable quantum key distribution of unidimensional gaussian modulation using polarized coherent states in an urban environment. Phys. Rev. A 100, 012325 (2019).

Ruppert, L. et al. Fading channel estimation for free-space continuous-variable secure quantum communication. N. J. Phys. 21, 123036 (2019).

Wang, S., Huang, P., Wang, T. & Zeng, G. Dynamic polarization control for free-space continuous-variable quantum key distribution. Opt. Lett. 45, 5921–5924 (2020).

Zheng, X.-T., Zhang, Q.-F., Ling, J., Guo, G.-C. & Han, Z.-F. Free-space continuous-variable quantum key distribution under high background noise. npj Quantum Inf. 11, 52 (2025).

Qi, B. et al. Experimental passive-state preparation for continuous-variable quantum communications. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 054065 (2020).

Qi, B., Evans, P. G. & Grice, W. P. Passive state preparation in the gaussian-modulated coherent-states quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. A 97, 012317 (2018).

Huang, P. et al. Experimental continuous-variable quantum key distribution using a thermal source. N. J. Phys. 23, 113028 (2021).

Zhang, M., Huang, P., Wang, P., Wei, S. & Zeng, G. Experimental free-space continuous-variable quantum key distribution with thermal source. Opt. Lett. 48, 1184–1187 (2023).

Luo, H., Wang, Y., Zhong, H., Zuo, Z. & Guo, Y. Passive state preparation continuous variable quantum key distribution in a satellite-mediated link. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 40, 2480–2488 (2023).

Ji, F., Huang, P., Wang, T., Jiang, X. & Zeng, G. Gbps key rate passive-state-preparation continuous-variable quantum key distribution within an access-network area. Photonics Res. 12, 1485–1493 (2024).

Liu, H.-Y. et al. Drone-based entanglement distribution towards mobile quantum networks. Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 921–928 (2020).

Xue, Y. et al. Airborne quantum key distribution: a review. Chin. Opt. Lett. 19, 122702 (2021).

Tian, X.-H. et al. Experimental demonstration of drone-based quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 200801 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Long-distance continuous-variable quantum key distribution over 202.81 km of fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 010502 (2020).

Chen, Z., Wang, X., Yu, S., Li, Z. & Guo, H. Continuous-mode quantum key distribution with digital signal processing. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 28 (2023).

Hajomer, A. A. et al. Long-distance continuous-variable quantum key distribution over 100-km fiber with local local oscillator. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi9474 (2024).

Usenko, V. C. et al. Entanglement of gaussian states and the applicability to quantum key distribution over fading channels. N. J. Phys. 14, 093048 (2012).

Laudenbach, F. et al. Continuous-variable quantum key distribution with gaussian modulation—the theory of practical implementations. Adv. Quantum Technol. 1, 1800011 (2018).

Sibson, P. et al. Chip-based quantum key distribution. Nat. Commun. 8, 13984 (2017).

Kwek, L.-C. et al. Chip-based quantum key distribution. AAPPS Bull. 31, 1–8 (2021).

Shan, X., Sun, X., Luo, J., Tan, Z. & Zhan, M. Free-space quantum key distribution with rb vapor filters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 19 (2006).

Grangier, P., Levenson, J. A. & Poizat, J.-P. Quantum non-demolition measurements in optics. Nature 396, 537–542 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0300703), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2019SHZDZX01), the Key R\&D Program of Guangdong province (Grant No. 2020B0303040002), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62101320).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. conceived the research project. P.H. and H.Y. designed the scheme with assistance from T.W.; H.Y. carried out the experiments with assistance from Z.Z.; X.J. contributed the approach to post-processing. H.Y. and P.H. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, H., Huang, P., Zhou, Z. et al. All-day free-space quantum key distribution with thermal source towards quantum secure communications for unmanned vehicles. npj Quantum Inf 11, 134 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01085-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01085-y