Abstract

Executing quantum algorithms using Majorana zero modes—a major milestone for the field of topological quantum computing—requires a platform that can be scaled to large quantum registers, can be controlled in real time and space, and a braiding protocol that uses the unique properties of these exotic particles. Here, we demonstrate the first successful simulation of a Majorana-based, fault-tolerant quantum algorithm to solve the Bernstein-Vazirani problem in two-dimensional magnet-superconductor hybrid structures from initialization to read-out of the final many-body state. Utilizing the Majorana zero modes’ topological properties, we introduce an optimized braiding protocol for the algorithm and a scalable architecture for its implementation with an arbitrary number of qubits. We visualize the algorithm protocol in real time and space by computing the non-equilibrium density of states, which is proportional to the time-dependent differential conductance, and the non-equilibrium charge density, which assigns a unique signature to each final state of the algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological superconductors harbor Majorana zero modes (MZMs), which have been proposed as a promising platform for the realization of fault-tolerant quantum computing due to their non-Abelian braiding statistics and robustness against disorder and decoherence effects1,2,3. Magnet-superconductor hybrid (MSH) systems, consisting of magnetic adatoms placed on the surface of s-wave superconductors, have been shown to be a suitable material platform for the design of topological superconducting phases, providing strong evidence for the existence of MZMs in one-4,5,6,7 and two-dimensional8,9,10,11 systems. To theoretically test the feasibility of MZMs for the implementation of topologically protected quantum algorithms in MSH systems, it is necessary to translate established quantum algorithms12,13,14,15,16 into braiding protocols for Majorana zero modes17, and successfully simulate these in real time and space. While this has been achieved for the Clifford gates—the fundamental building blocks of topologically protected quantum algorithms—in N = 2 qubit systems on various material platforms17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, the crucial extension to more complex quantum algorithms and larger (N > 2) qubit systems has not yet been achieved. Of particular interest here is the question of whether Majorana-based quantum algorithms can be employed to solve the Bernstein-Vazirani (BV) problem13,14, requiring that a hidden number s, encoded into an oracle function Us, can be read out from the final state of an N-qubit system after a single query of the oracle. While experimental attempts to implement the BV algorithm in non-topological systems33,34,35,36,37,38 have been reported, no demonstration of its feasibility and scalability in topologically protected, MZM-based systems, has been provided to-date.

In this article, we demonstrate the successful solution of the BV problem by simulating a Majorana-based, fault-tolerant quantum algorithm from initialization to read-out in an N = 3 qubit MSH system. To this end, we combine the proposal for MZM braiding via the manipulation of the magnetic structure in MSH systems—motivated by electron-spin resonance-scanning tunneling microscopy (ESR-STM) experiments, demonstrating that individual spins in small magnetic clusters can be flipped39,40,41,42—with theoretical advances in simulating time-dependent phenomena in superconductors23,24,32. This combination enables us to simulate the MZM-based quantum algorithm to solve the BV problem and compute its success probabilities on experimentally relevant time and length scales. We show how the choice of a network architecture allows us to initialize the system in various pure N-qubit many-body states, both in the even- and odd-parity sectors. Moreover, we demonstrate that the hidden number s can be experimentally read out from the spatial form of the charge density after fusing MZM pairs at the conclusion of the BV algorithm. Finally, we visualize the entire BV algorithm in time and space by using the time-, energy-, and spatially-resolved non-equilibrium density of states, Nneq43, to image the MZM world lines. Our results establish for the first time the feasibility of implementing topologically protected quantum algorithms in MSH systems, providing an important step towards the realization of topological quantum computing.

Results

Theoretical methods

As a platform for the implementation of the BV algorithm, we use MSH structures, consisting of a network of magnetic adatoms placed on the surface of a two-dimensional (2D) superconductor, which are described by the Hamiltonian

Here, \({c}_{{\bf{r}},\beta }^{\dagger }\) creates an electron with spin β at site r, -te denotes the nearest-neighbor hopping parameter on a 2D square lattice, μ is the chemical potential, α is the Rashba spin-orbit coupling between nearest-neighbor sites r and r + δ, Δ is the s-wave superconducting order parameter, J is the magnetic exchange coupling between the magnetic adatom with spin SR at site R and the conduction electrons, and \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}={({\sigma }_{x},{\sigma }_{y},{\sigma }_{z})}^{T}\) is the vector of Pauli matrices. As the hard superconducting gap suppresses Kondo screening44,45, we consider the magnetic adatoms as classical spins, whose orientation at a time t is given by SR(t).

Below we choose parameters such that (i) the MSH network is topological when the magnetic adatom moments possess a ferromagnetic (FM) out-of plane alignment, but is trivial when the moments exhibit an antiferromagnetic (AFM) in-plane order, and (ii) the MZM localization length is significantly smaller than the network size we can consider computationally. To move the MZMs in space, we rotate the magnetic moments between the FM and AFM alignments, with the MZMs being always located at the end of the topological (FM) regions. This rotation of magnetic moments, which in principle can be achieved using ESR-STM techniques39,40,41,42 (for a detailed discussion, see ref. 32), is characterized by a rotation time TR to rotate a single moment by π/2 between in- and out-of-plane alignment. To ensure the adiabaticity of the entire BV algorithm, we choose a rotation time TR ≫ ℏ/Δt where Δt is the topological gap in the system (for details, see “Methods” section). Below, all times are given in units of τe = ℏ/te.

For an N qubit system, the BV algorithm13,14 encodes a hidden number s = 0, . . . , 2N−1 in an oracle function Us, which is translated into a specific braiding protocol of the MZMs. The time evolution of the entire system’s many-body wave-function \(\left\vert \Psi (t)\right\rangle\) under the braiding protocol is computed using a recently developed non-equilibrium formalism23,32 (for details, see “Methods” section). Starting point for all our simulations is the topologically trivial, even-parity ground state of the system, \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\), in which all spins of the MSH network are aligned AFM in-plane; thus \(\left\vert \Psi (t=0)\right\rangle =\left\vert GS\right\rangle\). By changing the spin orientation in certain segments of the network from in-plane AFM to out-of-plane FM, the system becomes topological and is initialized into one of the 2N pure (many-body) qubit states \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) at time t = ti. The application of the BV algorithm, as reflected in the braiding protocol, then yields \({{\rm{BV}}}_{s}\left\vert n\right\rangle =\left\vert n\oplus s\right\rangle\). To evaluate the success of the BV algorithm, we define the time-dependent transition probability pn(t) = ∣〈Ψ(t)∣n〉∣2. Thus, pn(ti) = 1 describes the successful initialization of the system into a desired initial state \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\), and pn⊕s(tc) = ∣〈Ψ(tc)∣n⊕s〉∣2 = ∣〈Ψ(tc)∣BVs∣n〉∣2 = 1 reflects a perfect implementation of the BV algorithm which concludes at time t = tc. While a classical computer requires N queries of the oracle to find the hidden number s with absolute certainty, a quantum computer requires a single query, being able to obtain s from a comparison of the initial \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) and final \(\left\vert n\oplus s\right\rangle\) states. As we show below, the read-out of these states can be experimentally achieved by measuring the local charge density (for details, see “Methods” section)

after fusion of MZM pairs, as it directly reflects a pair’s occupation, and thus allows to uniquely identify all 2N many-body states of an N qubit system.

Finally, we visualize the entire BV algorithm from initialization to fusion using the energy-, time-, and spatially-resolved non-equilibrium density of states Nneq(r, σ, t, ω), which is proportional43 to the time-dependent differential conductance dI(V, r, t)/dV measured in STM experiments (for details, see “Methods” section).

To identify a hidden number s using the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm, one proceeds in three steps: (i) initialization of the system in a many-body state \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\), (ii) execution of the BV algorithm as represented by a MZM braiding protocol, (iii) read-out of the final state \(\left\vert n\oplus s\right\rangle\). Below, we will discuss each step separately to elucidate how the system’s architecture affects its initialization and the implementation of the BV algorithm.

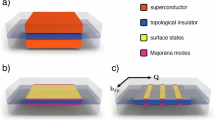

Gate architecture

While T-structures (see Fig. 1a) have previously been discussed as the basic computing architecture18, it was recently proposed that more compact, folded MSH networks (see Fig. 1b, c) provide several advantages as they enable additional braiding operations and the use of spatial symmetries to efficiently implement quantum gates32. Below, we therefore consider the network architectures shown in Fig. 1b, c for the simulation of the BV algorithm in N = 2 and 3 qubit systems, respectively. These structures can be generalized to large N qubit systems by using the unit cell structure shown in Fig. 1d as the building block.

a–c MSH architectures for the simulation of the Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm. Spin orientations are represented by white arrows (white dots representing an out-of-plane orientation), and the zero-energy Nneq (color scale) reveals the existence of MZMs at the end of the topological (FM) rungs. d Unit cell (shown in full color, adjacent unit cells are shown in opaque) to generalize the MSH architecture to a (large) N qubit system. e Nneq for several times during the initialization process along a single rung in the MSH structure. Initialized state \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) as a function of the chemical potential for the f N = 2 and g N = 3 qubit systems. Parameters are (μ, α, Δ, JS) = (−3.93, 0.45, 1.2, 2.6)te, Γ = 0.03te with an execution time of 4000τe for the initialization process.

Initialization

The initialization of the system into a many-body qubit eigenstate \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\) starts from the even-parity ground state of the trivial phase, denoted by \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\), in which the spins possess an AFM in-plane alignment. To initialize the system in a topological many-body state, we create three (four) topological rungs in the MSH network of Fig. 1b (Fig. 1c), each of which exhibits two MZMs at its ends, by rotating the spins consecutively to an out-of-plane FM alignment, starting in the center of the rung. The non-equilibrium density of states for one of the rungs for several times during this initialization process is shown in Fig. 1e. The resulting many-body eigenstate of the MSH network in the Fock notation is denoted by \(\left\vert n\right\rangle ={\left\vert {l}_{1}{l}_{2}...\right\rangle }_{F}\), with li ∈ {0, 1} describing the occupation of the MZM pair on the ith rung, and depends not only on the system’s chemical potential, μ, but also on the specific MSH architecture as shown in Fig. 1f, g for the N = 2 and N = 3 qubit architecture, respectively. While the initialization in all cases starts from \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\), an occupation of an individual Majorana pair different from zero occurs when the ferromagnetic moment of the initialized topological rung is sufficiently strong to break a Cooper pair, resulting in a local phase transition that changes the parity of the superconducting ground state (for further details, see Supplementary Note 1). This is similar to the local phase transition that an s-wave superconductor undergoes when the scattering strength of a single44,46,47,48 or multiple magnetic impurities49,50 exceeds a critical value. Due to the spatial symmetry of the N = 3 qubit system (Fig. 1c), two of the four rungs simultaneously undergo a phase transition and thus change their occupation in the initialization process, implying that the possible many-body states after initialization are always in the even-parity sector. In contrast, for the N = 2 qubit system (Fig. 1b), only two of the three rungs possess the same spatial symmetry, and hence the many-body states after initialization can either be in the even- or odd-parity sector, depending on whether an even (0 or 2) or odd (1 or 3) number of rungs undergoes the phase transition. Thus, by starting from a single trivial state \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\) and utilizing the spatial symmetry of the MSH architecture, one can initialize the system into specific topological many-body states \(\left\vert n\right\rangle\), both in the even- and odd-parity sectors.

BV algorithm

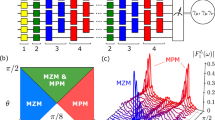

The BV algorithm is decomposed into a Hadamard gate that creates a superposition of all qubit states, an Oracle function that encodes the hidden number s, and a second Hadamard gate that reverses the superposition of qubit states (see Fig. 2a). We generalize the Hadamard gate for an N qubit system with 2N + 2 MZMs by employing \(N\sqrt{X}\) gates as sketched in Fig. 2b (see Supplementary Note 2). Here, the \(\sqrt{X}\)-gate (\(\sqrt{Z}\)-gate) represents a braid of two MZMs from adjacent pairs (the same pair). This N-qubit generalized Hadamard gate results in an equal-weight superposition of all 2N pure N-qubit states involving complex phases (see Supplementary Note 2) and is thus non-Hermitian H ≠ H†. We therefore need to employ H† as the second Hadamard gate in the BV algorithm, which is realized by inverting the directions of the MZM braids in H. We note that this generalization of the Hadamard gate not only significantly reduces the number of required braiding operations and allows for their simultaneous execution, but also realizes a unique generalization to N ≥ 2 qubit systems, in contrast to previous proposals using combinations of \(\sqrt{X}\)- and \(\sqrt{Z}\)-gates3,17 (see Supplementary Note 2). Finally, we note that the braiding protocol for the oracle function Us satisfies the generalized form \({U}_{s}\left\vert n\right\rangle ={(-1)}^{{\bf n}\cdot \hat{A}\cdot {\bf s}}\left\vert n\right\rangle\), where the matrix \(\hat{A}\) is determined by the specific realization of the Hadamard gate (for details, see Supplementary Note 2).

a Schematic of the Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm for N qubits (with 2N + 2 MZMs). Braiding protocol for b the N-qubit generalized Hadamard gate using \(N\sqrt{X}\)-gates, and c the oracle function Us for N = 2, 3 qubits using Z-gates. Real space braiding processes for d the generalized Hadamard gate for an N = 2 qubit system, and e the oracle function for an N = 3 qubit system with s ∈ {001, 010, 100, 111}. Time-dependent transition probabilities for the f N = 2 qubit system with s = 11, and the g N = 3 qubit system with s = 001, starting from the initialization time ti. Parameters are μ = −3.913te (−3.93te), (α, Δ, JS) = (0.45, 1.2, 2.6)te with execution times of 2200τe (3200τe) for the generalized Hadamard gate and 1980τe (2460τe) for the oracle for the N = 2 (N = 3) qubit system.

The folded MSH networks shown in Fig. 1b, c (in contrast to the conventional T-structure) allow for an efficient implementation of the MZM braiding protocols shown in Fig. 2b, c. In particular, the generalized Hadamard gate for the N = 2 qubit system can be implemented by rotating 4 MZMs by 180∘ clockwise (see Fig. 2d)—thus simultaneously realizing two \(\sqrt{X}\) gates—while the Z-gates for the oracle are implemented by moving an MZM pair along a plaquette (see Fig. 2e). Both of these implementations allow for faster execution times as they preserve the distance between the MZMs.

The mapping \({{\rm{BV}}}_{s}\left\vert n\right\rangle =\left\vert n\oplus s\right\rangle\) holds both in the Fock (occupation) notation (\({\left\vert ...\right\rangle }_{F}\)), as well as in the logical qubit state notation (\({\left\vert ...\right\rangle }_{q}\)), with the value of s given in the respective notation. However, there exists some freedom in choosing the translation between these two notations. Here, in the even-parity sector for N = 3, we set \({\left\vert 0000\right\rangle }_{F}={\left\vert 000\right\rangle }_{q}\), and a value of “1” in the ith position of s is assigned when a Z-gate is performed on the ith pair of MZMs (unless otherwise stated, s is given in the logical qubit notation below). This completely determines the mapping between these two notations shown in Table 1 (for additional details, and the mapping for the N = 2 qubit systems, see Supplementary Note 2).

To test the braiding protocol in Fig. 2 for the simulation of the BV algorithm, we consider two cases: (i) an N = 2 qubit system, initialized into the odd-parity state \(\left\vert n\right\rangle ={\left\vert 111\right\rangle }_{F}={\left\vert 11\right\rangle }_{q}\) and s = 11, and (ii) an N = 3 qubit system initialized into the even-parity state \(\left\vert n\right\rangle ={\left\vert 0110\right\rangle }_{F}={\left\vert 011\right\rangle }_{q}\) and s = 001; the corresponding time-dependent probabilities pn(t) and pn⊕s(t) for these two cases are shown in Fig. 2f, g, respectively. Starting from \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\), we obtain for both cases pn(ti) = 1 (within numerical uncertainty), implying that the system is initialized into the desired state at t = ti. The two peaks in the probabilities (see black arrows) denote the times right after the first generalized Hadamard gate is completed (and the superposition of all N-qubit states is achieved), and right before the second generalized Hadamard gate begins. The expected value for the probabilities at these times is \(| \left\langle n\right\vert H\left\vert n\right\rangle {| }^{2}=1/{2}^{N}\) (see horizontal dashed line), in good agreement with our results. After the completion of the BV algorithm at t = tc , we obtain pn⊕s(tc) = 0.997 and pn⊕s(tc) = 0.998 for the cases shown in Fig. 2f, g, respectively. Since these probabilities, as well as those for all other values of s (see Supplementary Note 3) are within the error correction threshold51,52, our results establish the first successful simulation of the BV algorithm in MSH systems. Note that the small reduction of the success probabilities from unity arises from the weak, but non-zero hybridization between the MZMs32, referred to as Pauli errors, which can be corrected using the approaches discussed in ref. 53.

Fusion and read-out

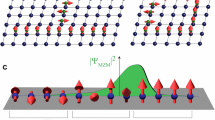

The experimental read-out of the final state \(\left\vert n\oplus s\right\rangle\) can be achieved by measuring the charge density arising from the fusion of MZM pairs, as it directly reflects their occupation based on the fusion rule γ × γ = 1 + ψ, where γ represents the MZMs, 1 the vacuum, and ψ the electron3. After the completion of the BV algorithm, fusion is achieved by rotating the spins in the topological rungs to an AFM in-plane alignment, starting from the ends of the topological rungs and continuing towards their centers, as schematically shown in Fig. 3a. In Figs. 3b–d, we present spatial plots of the charge density difference, Δρ(r, tf) = ρ(r, tf) − ρGS(r), after the completion of the fusion process at t = tf. By subtracting the charge density ρGS of the ground state \(\left\vert GS\right\rangle\), we can immediately read out the hidden number \(\left\vert s\right\rangle\) in the Fock basis (and then convert it to the logical basis using Table 1), by assigning a value of 1 (0) to each MZM pair whose fusion results in a non-zero (zero) residual charge. For example, the BV algorithm for s = 001 results in a charge density after fusion (see Fig. 3b) that is nonzero on rungs 1 and 2, and vanishing on rungs 3 and 4, thus yielding \(\left\vert s\right\rangle ={\left\vert 1100\right\rangle }_{F}={\left\vert 001\right\rangle }_{q}\) (see Table 1), as expected. Similarly, we can identify \(\left\vert s\right\rangle\) from the charge density on each rung for s = 010 (Fig. 3c) and s = 100 (Fig. 3d). A plot of the time-dependent charge density difference along rung 1 is shown in the inset of Figs. 3b; it demonstrates that the charge remains localized after the completion of the fusion process, as the fusion point is also an intersection point of three rungs, which traps the charge and thus facilitates its experimental detection (in contrast to MZM fusion along a rung with no intersection point for the N = 2 qubit system, see Fig. 2d and Supplementary Note 4). We thus demonstrated that the hidden number s can be read-out experimentally by measuring the charge density after fusion.

a Spatial plot of Nneq during the fusion process for the N = 3 qubit system. b–d Spatial form of the charge density difference, Δρ(r), after the completion of the fusion process for b s = 001, c s = 010, and d s = 100. Inset of b shows the time dependence of Δρ(r) along rung 1. e Majorana world lines for the N = 3 qubit system from initialization to readout, with the real space projection axis shown as a dashed yellow line in a. Vertical dotted lines indicate the start and end times for the generalized Hadamard gates and the oracle. Parameters are (μ, α, Δ, JS) = (− 3.93, 0.45, 1.2, 2.6)te, Γ = 0.03te with execution times of 3200τe for the generalized Hadamard gate, 2460τe for the oracle, and 4800τe for the initialization and fusion.

Spatial imaging of Majorana world lines

We visualize the entire BV algorithm from initialization to fusion via the energy-, time- and spatially-resolved non-equilibrium density of states Nneq(r, σ, t, ω)43 (for details, see “Methods” section). The full time dependence of the spatially resolved zero-energy Nneq for the cases of Fig. 2f, g is provided in Supplementary Movies 1 and 2, respectively (see also Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 in Supplementary Note 5), demonstrating, as expected, that at any time, the MZMs are localized near the edges of the topological regions. By projecting Nneq onto the real space axis shown in Fig. 3a, we image the Majorana world lines, visualizing the entire BV algorithm in time and space, as shown in Fig. 3e (a full 3D rendering of the world lines for the cases of Fig. 2f, g is shown in Supplementary Movies 3 and 4, respectively). To provide insight into the actual timescale for the execution of the BV algorithm, we note that while the experimentally observed topological gaps vary substantially between different MSH systems54, the largest reported value to date is approximately 1.5 meV55. By equating this value to the topological gap in our system, we obtain an execution time of the BV algorithm of approximately 1.6 ns (see upper x-axis in Fig. 3e). This time scale is significantly smaller than the coherence time T2 ≈ 300 ns realized in ESR-STM experiments42, which sets the upper time limit for a successful execution of the algorithm.

Detecting faulty implementations

The question naturally arises to what extent faulty implementations of the BV algorithm with pn⊕s(tc) < 1 can be experimentally detected. To investigate this question, we consider two faulty scenarios: (I) we detune the generalized Hadamard gate, by changing its execution time such that, while the BV algorithm is still adiabatic, the state created after the application of the generalized Hadamard gate is not an equal superposition of pure qubit states (see Supplementary Note 2), and (II) by significantly reducing the execution time of the entire BV algorithm by a factor of 5, which leads to excitations between the MZMs and bulk states and thus renders the BV algorithm non-adiabatic. The time-dependent probabilities for both scenarios with s = 001 are shown in Fig. 4a, b, respectively, revealing significantly reduced success probability of pn⊕s(tc) = 0.78 (scenario I) and pn⊕s(tc) = 0.0167 (scenario II). These are directly reflected in the spatial form of Δρ: while for the perfect, adiabatic BV algorithm for s = 001, a non-zero charge distribution after fusion exists only on rungs 1 and 2 (see Fig. 3b), the imperfect scenarios I and II now also yield non-zero charges on rungs 3 and 4 (see Fig. 4c, d, respectively). In addition, for scenario II, a non-zero Δρ(r) emerges even away from the fusion point, thus discriminating it not only from the perfect case, but also from scenario I. Moreover, scenarios I and II can also be distinguished using the time- and energy-dependent Nneq (see Fig. 4e, f), at a specific site in the MSH network indicated by the yellow dot in Fig. 4c. In both cases, the MZM moves through this site during the BV algorithm, with the maximum intensity indicated by a dashed white line. However, for the adiabatic scenario I, the MZM remains well separated from the bulk states, while for the non-adiabatic scenario II, a hybridization between the MZM and the bulk states is clearly visible (see white dashed line in Fig. 4f). We thus conclude that the form of Δρ as well as that of Nneq distinguishes not only the faulty implementation of the BV algorithm from a perfect one, but also identifies the origin of the faulty realization—detuning versus non-adiabaticity.

Time-dependent transition probabilities for s=111 and a a detuned generalized Hadamard gate (scenario I), and b a non-adiabatic implementation with a significantly reduced execution time of the BV algorithm (scenario II). Δρ(r) after completion of the fusion process for s = 100 and c scenario I, and d scenario II. Energy-resolved non-equilibrium local density of states at the site marked by the yellow dot in c for e scenario I and f scenario II, showing the movement of one of the Majorana zero modes through this site. Parameters are (μ, α, Δ, JS) = (−3.93, 0.45, 1.2, 2.6)te, Γ = 0.01te and execution times of 36800τe (640.0τe) for the generalized Hadamard gate, 2460τe (496τe) for the oracle, and 4800τe(960τe) for the initialization and fusion processes for scenario I (II). For scenario I, the detuning was achieved by choosing TR, ΔTR = (1600, 320)τe, in contrast to the perfect generalized Hadamard gate used for the results shown in Fig.3 with TR, ΔTR = (1000, 20)τe.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the successful simulation of the topologically protected BV algorithm from initialization to read-out in 2D MSH systems using Majorana zero modes. We showed that starting from the ground state of the topologically trivial system, it is possible to initialize the system into various topological even- and odd-parity states through the interplay of the MSH architecture and the system’s chemical potential. We demonstrated how the hidden number s in the logical qubit bases can be straightforwardly encoded in the braiding protocol representing the oracle, allowing us to arrive at an efficient translation between the Majorana-based Fock notation and the logical qubit notation for the many-body states. We proposed a new approach to efficiently and uniquely generalize the Hadamard gate to N≥2 qubit systems using simultaneously executed \(\sqrt{X}\)-gates, thus ensuring that the execution time of the Hadamard gate is independent of N. We also showed that after the conclusion of the BV algorithm and the fusion of the MZM pairs, the hidden number s can be read out from the spatial form of the excess charge density, Δρ. We demonstrated that the entire BV algorithm is visualized in time and space via the non-equilibrium density of states, Nneq, which allowed us to directly image the Majorana world lines. Finally, we showed that the form of Δρ and Nneq allows us to discriminate between perfect and faulty implementations of the BV algorithm, and identify the origin of the latter. Our results thus provide the proof of concept that topologically protected, complex quantum algorithms can be successfully simulated in MSH structures.

While experimental challenges and approaches to the implementation of the above braiding scheme have been discussed before32, several theoretical questions remain open and need to be addressed in the future. Of particular importance here are the effects of decoherence, noise, and quasi-particle poisoning—i.e., the presence of unpaired electrons—on the successful simulation of the algorithm. Our preliminary work on single X- and Z-gates has shown that in MSH systems, the effect of quasi-particle poisoning is negligible if the braiding process is conducted in the adiabatic limit. A further discussion of this and other pertinent issues is reserved for future work.

Methods

Creation of the topological computation basis

The Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) can be rewritten in the Bogoliubov-de Gennes (BdG) form

where HBdG possesses a particle-hole symmetry, which can be expressed as \({H}_{{\rm{BdG}}}=-{\tau }_{x}{H}_{{\rm{BdG}}}^{* }{\tau }_{x}\) with τx being the Pauli X-matrix in particle-hole space. At t = 0, the Bogoliubov transformation

diagonalizes the Hamiltonian

with En ≥ 0. The ground state \(\left\vert \Omega \right\rangle\) of the system is the quasiparticle vacuum defined via \({d}_{n}\left\vert \Omega \right\rangle =0\forall n\). We construct it from the vacuum of the c-operators \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\)18,56 via

where the normalization is given by \({\mathcal{N}}=| {{\det }}(\hat{V})|\), where \({[\hat{V}]}_{jn}={V}_{jn}\) in Eq. (4). As the Hamiltonian considered here conserves fermion parity, we restrict ourselves to either the even or the odd parity sector, i.e. \(P={\sum }_{n}\langle {d}_{n}^{\dagger }{d}_{n}\rangle =0\,{\rm{or}}\,1\,{\rm{mod}}\,2\). The states in our topological computation basis with N qubits, i.e. N + 1 Majorana pairs, are thus

Here, \({d}_{j}^{\dagger }\) creates an electron in the jth Majorana pair (i.e., this pair becomes occupied), and the occupation of the (N+1)'th Majorana pair is chosen such that the fermion parity P of all 2N states is fixed to be either even (P = 0) or odd (P = 1). Which one of the Majorana pairs is chosen as the parity-conserving one is arbitrary.

Time evolution of states

The time-evolved quasiparticle operators are given by

with the time-evolution operator

Using the time-dependent BdG equations, the time-evolved quasiparticle operators are given by

where

with the elements of the matrices \(\hat{U},\hat{V}\) given by \({[\hat{U}]}_{in}={U}_{in}\) and \({[\hat{V}]}_{in}={V}_{in}\) in Eq. (10). As such, we can write the time-evolved quasiparticle vacuum as

with the normalization \({\mathcal{N}}(t)=| \det (V(t))|\). The phase α stems from the time evolution of the true vacuum. However, this phase is gauged away in our gauge-invariant formulation of physical quantities, such as the transition probabilities. Hence, the time-evolved states in our logical basis are given by

Transition probabilities

The probability for transitions between states \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle ={\left\vert {n}_{1}\cdots {n}_{N}{n}_{N+1}\right\rangle }_{F}(t)\) and \(\left\vert {\psi }^{{\prime} }(0)\right\rangle ={\left\vert {n}_{1}^{{\prime} }\cdots {n}_{N}^{{\prime} }{n}_{N+1}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle }_{F}(0)\) takes the form

This probability can be computed using the Onishi Formula56,57 and the Bogoliubov transformations from Eqs. (4) and (10) via

Charge density

The electronic charge density at site r for spin σ in the state \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) is given by ρ(r, σ) = −enr,σ , where

Numbering the sites and other degrees of freedom from 1 to ND, we define the spinors

which are related via the Bogoliubov-de Gennes transformation as

where the elements of the matrices \(\hat{U}\), \(\hat{V}\) are given by \({[\hat{U}]}_{in}={U}_{in}\) and \({[\hat{V}]}_{in}={V}_{in}\) in Eq. (10). We have for the ground state \(\left\vert \Omega \right\rangle\)

and thus

The charge density is then given by the ND diagonal elements of the lower right block of this matrix, and thus

The time-evolved charge density is obtained by using the time-evolved Bogoliubov-de Gennes equations, and the resulting time-evolved matrix M(t)

The time-dependent charge density is then obtained from

as

Time dependence of spin rotations

The rotation of the spins in the network is governed by two time scales during each step of the algorithm: a rotation time TR to rotate one individual spin by a polar angle of π/2, and a delay time ΔTR before the next spin starts rotating. We use spherical coordinates to describe each spin’s orientation in space, such that

Therein, we use the function

so that the transition from 0 to π/2 for the polar angle is executed smoothly. For instance, the initialization of the spins Si on one rung of length 2L + 3, numbered from 0 to 2L + 2, from in-plane antiferromagnetic alignment to out-of-plane ferromagnetic alignment is executed by the following time dependence of the polar angles

which rotates the center spin out-of-plane first, followed by the next two adjacent spins after the delay time ΔTR, and so forth until all spins are rotated out-of-plane. The azimuthal angle ϕ is chosen for each spin such that its in-plane orientation is perpendicular to the direction of the network chain at that site, i.e., for a horizontal segment \(\phi =\frac{\pi }{2}\), for a vertical segment ϕ = 0. All other parts of the processes are executed with similar rotation protocols.

Non-equilibrium local density of states

The time-dependent processes discussed in the main text can be experimentally visualized by measuring the time-dependent differential conductance dI(V, r, t)/dV in scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) experiments. We previously showed that, in analogy to the equilibrium case, this quantity is proportional to the non-equilibrium density of states defined as \({N}_{neq}({\bf{r}},\sigma ,t,\omega )=-\frac{1}{\pi }{\rm{Im}}{G}^{r}({\bf{r}},{\bf{r}},\sigma ,t,\omega )\)43. Here, the time- and frequency-dependent retarded Green's function \({\hat{G}}^{r}\) is calculated from the differential equation

Data availability

Original data are available at 10.5281/zenodo.17329912.

Code availability

The codes that were employed in this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083 (2008).

Sarma, S. D., Freedman, M. H. & Nayak, C. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. npj Quantum Inf. 1, 15001 (2015).

Beenakker, C. W. J., Search for non-Abelian Majorana braiding statistics in superconductors, SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 15, https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.15 (2020).

Nadj-Perge, S. et al. Observation of Majorana fermions in ferromagnetic atomic chains on a superconductor. Science 346, 602 (2014).

Ruby, M. et al. End states and subgap structure in proximity-coupled chains of magnetic adatoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 197204 (2015).

Pawlak, R. et al. Probing atomic structure and Majorana wavefunctions in mono-atomic Fe-chains on superconducting Pb-surface. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 16035 (2016).

Kim, H. et al. Toward tailoring Majorana bound states in artificially constructed magnetic atom chains on elemental superconductors. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar5251 (2018).

Palacio-Morales, A. et al. Atomic-scale interface engineering of Majorana edge modes in a 2D magnet-superconductor hybrid system. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav6600 (2019).

Ménard, G. C. et al. Two-dimensional topological superconductivity in Pb/Co/Si(111). Nat. Commun. 8, 2040 (2017).

Kezilebieke, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 588, 424 (2020).

Bazarnik, M. et al. Antiferromagnetism-driven two-dimensional topological nodal-point superconductivity. Nat. Commun. 14, 614 (2023).

Deutsch, D. & Jozsa, R. Rapid solution of problems by quantum computation. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 439, 553 (1992).

Berthiaume, A. & Brassard, G. in Workshop on Physics and Computation. 195–199 (IEEE Computer Society, 1992).

Bernstein, E. & Vazirani, U. Quantum complexity theory. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1411 (1997).

Grover, L. K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. in Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, STOC ’96. 212–219 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1996).

Shor, P. W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 41, 303 (1999).

Kraus, C. V., Zoller, P. & Baranov, M. A. Braiding of atomic Majorana fermions in wire networks and implementation of the Deutsch-Jozsa algorithm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 203001 (2013).

Alicea, J., Oreg, Y., Refael, G., von Oppen, F. & Fisher, M. P. A. Non-abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1d wire networks. Nat. Phys. 7, 412 (2011).

Halperin, B. I. et al. Adiabatic manipulations of Majorana fermions in a three-dimensional network of quantum wires. Phys. Rev. B 85, 144501 (2012).

Sekania, M., Plugge, S., Greiter, M., Thomale, R. & Schmitteckert, P. Braiding errors in interacting Majorana quantum wires. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094307 (2017).

Harper, F., Pushp, A. & Roy, R. Majorana braiding in realistic nanowire Y-junctions and tuning forks. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 033207 (2019).

Tutschku, C., Reinthaler, R. W., Lei, C., MacDonald, A. H. & Hankiewicz, E. M. Majorana-based quantum computing in nanowire devices. Phys. Rev. B 102, 125407 (2020).

Mascot, E. et al. Many-body Majorana braiding without an exponential Hilbert space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 176601 (2023).

Hodge, T., Mascot, E., Crawford, D. & Rachel, S. Characterizing dynamic hybridization of Majorana zero modes for universal quantum computing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 096601 (2025).

Amorim, C. S., Ebihara, K., Yamakage, A., Tanaka, Y. & Sato, M. Majorana braiding dynamics in nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 91, 174305 (2015).

Aasen, D. et al. Milestones toward Majorana-based quantum computing. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031016 (2016).

Karzig, T. et al. Scalable designs for quasiparticle-poisoning-protected topological quantum computation with Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 95, 235305 (2017).

Zhou, T. et al. Fusion of Majorana bound states with mini-gate control in two-dimensional systems. Nat. Commun. 13, 1738 (2022).

Sanno, T., Miyazaki, S., Mizushima, T. & Fujimoto, S. Ab Initio simulation of non-Abelian braiding statistics in topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 103, 054504 (2021).

Hyart, T. et al. Flux-controlled quantum computation with Majorana fermions. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035121 (2013).

Li, J., Neupert, T., Bernevig, B. A. & Yazdani, A. Manipulating Majorana zero modes on atomic rings with an external magnetic field. Nat. Commun. 7, 10395 (2016).

Bedow, J., Mascot, E., Hodge, T., Rachel, S. & Morr, D. K. Simulating topological quantum gates in two-dimensional magnet-superconductor hybrid structures. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 99 (2024).

Du, J. et al. Implementation of a quantum algorithm to solve the Bernstein-Vazirani parity problem without entanglement on an ensemble quantum computer. Phys. Rev. A 64, 042306 (2001).

Brainis, E. et al. Fiber-optics implementation of the Deutsch-Jozsa and Bernstein-Vazirani quantum algorithms with three qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 157902 (2003).

Londero, P. et al. Efficient optical implementation of the Bernstein-Vazirani algorithm. Phys. Rev. A 69, 010302 (2004).

Peng, X. et al. "Spectral implementation” for creating a labeled pseudo-pure state and the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm in a four-qubit nuclear magnetic resonance quantum processor. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 3579 (2004).

Debnath, S. et al. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature 536, 63 (2016).

Wright, K. et al. Benchmarking an 11-qubit quantum computer. Nat. Commun. 10, 5464 (2019).

Yang, K. et al. Electrically controlled nuclear polarization of individual atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1120 (2018).

Yang, K. et al. Coherent spin manipulation of individual atoms on a surface. Science 366, 509 (2019).

Phark, S.-H. et al. Electric-field-driven spin resonance by on-surface exchange coupling to a single-atom magnet. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302033 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Universal quantum control of an atomic spin qubit on a surface. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 48 (2023).

Bedow, J., Mascot, E. & Morr, D. K. Emergence and manipulation of non-equilibrium Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states. Commun. Phys. 5, 281 (2022).

Balatsky, A. V., Vekhter, I. & Zhu, J.-X. Impurity-induced states in conventional and unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 373 (2006).

Heinrich, B. W., Pascual, J. I. & Franke, K. J. Single magnetic adsorbates on s-wave superconductors. Prog. Surf. Sci. 93, 1 (2018).

Sakurai, A. Comments on superconductors with magnetic impurities. Prog. Theor. Phys. 44, 1472 (1970).

Salkola, M. I., Balatsky, A. V. & Schrieffer, J. R. Spectral properties of quasiparticle excitations induced by magnetic moments in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 55, 12648 (1997).

Bazaliy, Y. B. & Jones, B. A. Magnetic impurity in a superconductor: local phase transitions and finite size effects. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 5561 (2000).

Morr, D. K. & Stavropoulos, N. A. Quantum interference between impurities: creating novel many-body states in s-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 67, 020502 (2003).

Morr, D. K. & Yoon, J. Impurities, quantum interference, and quantum phase transitions in s-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 73, 224511 (2006).

Raussendorf, R. & Harrington, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with high threshold in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 190504 (2007).

Stace, T. M., Barrett, S. D. & Doherty, A. C. Thresholds for topological codes in the presence of loss. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 200501 (2009).

Aasen, D. et al. Roadmap to fault tolerant quantum computation using topological qubit arrays. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.12252 (2025).

Lo Conte, R., Wiebe, J., Rachel, S., Morr, D. K. & Wiesendanger, R. Magnet-superconductor hybrid quantum systems: a materials platform for topological superconductivity. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 47, 453 (2024).

äck, B. et al. Observation of a Majorana zero mode in a topologically protected edge channel. Science 364, 1255 (2019).

Ring, P. & Schuck, P. The Nuclear Many-Body Problem, 1st edn., 1864–5879 (Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 1980).

Onishi, N. & Yoshida, S. Generator coordinate method applied to nuclei in the transition region. Nucl. Phys. 80, 367 (1966).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award No. DE-FG02-05ER46225. We would like to acknowledge helpful discussions with C. Lutz, E. Mascot, S. Rachel, and R. Wiesendanger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. performed the theoretical calculations. D.K.M. devised the project and supervised the theoretical calculations. D.K.M. and J.B. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bedow, J., Morr, D.K. Solving the Bernstein-Vazirani problem using Majorana-based topological quantum algorithms. npj Quantum Inf 11, 180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01120-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01120-y