Abstract

Germanium quantum dots in strained Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructures exhibit fast and coherent hole qubit control. Nevertheless, a full theoretical understanding of their underlying physics is lacking due to the absence of a systematic method of accounting for inhomogeneous strain, whose effects often overwhelm the bare spin-orbit coupling in the Luttinger Hamiltonian. Here we seek to remedy this shortcoming by addressing the effects of random alloy disorder and gate-induced strain on the operation of planar Ge hole spin qubits. In good agreement with experimental numbers, our hybrid approach to realistic device modeling suggests that the resultant strain inhomogeneity make a strong contribution to the linear-k spin-orbit coupling1, which is Dresselhaus-like and eventually dominates hole spin EDSR; and there exist specific in-plane B-field and and the microwave drive (\({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\)) orientations for maximum hole spin EDSR Rabi frequency. State-of-the-art atomistic tight binding calculations via nano-electronic modeling (NEMO3D) are in agreement with the k ⋅ p description.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computing2,3,4 with semiconductor spin qubits5,6,7 has burgeoned over the past two decades8,9,10, owing to their prospective scalability from the elementary few-qubit systems to large arrays11,12,13. Quantum dots14 synthesized in Group IV materials are good candidates for spin qubits15,16, having the advantage of excellent compatibility with the semiconductor fabrication industry11. Silicon and germanium are of particular interest, as the possibility of having net-zero nuclear spin via isotopic purification17,18,19,20,21,22, and the absence of piezoelectric phonons23,24, can lead to long qubit coherence. Recently, quantum computing with holes in Si and Ge has garnered tremendous interest25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, dovetailing with the collective effort towards achieving all-electrical control of spin qubits32,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Compared to magnetic fields, electric fields are easier to apply locally and enable low-power qubit control with faster gate speeds. Holes in the p-type valence band (VB) of Si and Ge are characterized by an effective spin-3/2 and exhibit a large intrinsic spin-orbit coupling (SOC)43,44,45,46,47,48. The role of SOC in all electrical qubit control is well established49,50,51,52. Germanium as a material platform exhibits strong Fermi-level pinning close to the VB edge53,54, which means that hole qubits can be realized within reasonable gate bias ranges in experiments. Additionally, this enables the formation of Ohmic contacts for semiconductor-superconductor hybrid applications30,55,56,57,58,59,60, playing a significant factor in scaling up spin qubit systems.

SOC in hole systems mediates anisotropy and tunability of the g-tensor32,37,61, which can have beneficial effects for qubit coherence33,62,63,64. Therefore, for fast and coherent spin qubit manipulation, holes may offer advantages16,65 over electron systems, where operational speed is often sacrificed for coherence66,67, and reliance on micromagnets complicates scaling up35,68,69,70. Strained germanium quantum wells (QWs)71,72,73 and silicon complementary metal oxide semiconductor28,74 are particularly suited for high-frequency hole qubit experiments demonstrating fast and coherent electrical control27,30,33,36,75,76,77,78. Strained Ge QWs in undoped heterostructures have been at the forefront of the recent experimental effort in holes29,54, ranging from universal single qubit and two-qubit logic31,79,80, singlet-triplet hole qubit77, a four-qubit germanium processor81 to shared control of a large crossbar QD array82. With high hole mobilities of ≈106 cm2/(V s)83,84 and a low effective mass of 0.05 me85, strained Ge QWs in Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructures allow the formation of large, low-disorder hole quantum dots86.

Whereas the theory of Ge and Si hole qubits has evolved apace, with advances in the understanding of electrically driven spin resonance (EDSR)87,88,89, coherence62,90,91, relaxation25,92, g-factor anisotropy and singlet-triplet qubit control39,93, the variations in dot size, strain distribution, and energy dispersion across the many existing qubit architectures have made it difficult to develop a unified theoretical approach. Experiments have shown a high variability in the properties of hole spin qubits, which is believed to be due to the inhomogeneous strain field to which they are exposed, as revealed by X-ray diffraction microscopy94. Inhomogeneous strain in Ge quantum dots, which arises from random alloy disorder, lattice mismatch at the interface, and gate electrode contraction, leads to additional inversion asymmetry95,96,97. The resultant SOC is extremely important for realistic device modeling, as it can overwhelm the bare SOC from the Luttinger Hamiltonian1,97,98. It results, for example, in g-factor anisotropy and g-tensor modulation, qubit energy level variations99, and anisotropic noise sensitivity64. In the context of silicon holes, ref. 32 showed that non-uniform strain arising from thermal contraction of the gate electrodes has a sizable effect on the SOC and g-tensor in hole quantum dots. At the same time, recent analytical and numerical models have captured the non-trivial interplay between intrinsic SOC and external electrical control52,100,101. However, qubit operational timescales remain underestimated in theory compared to experimental observations. Moreover, a flexible approach that can systematically account for the device-specific local non-uniformity is at present lacking in the field. For example, tight-binding simulations can reasonably describe the atomistic strain inhomogeneity in Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructure, but the key contribution to the SOC of the gate electrodes is overlooked. At the same time, while the linear-k SOC in Ge hole QDs resulting from strain gradients has recently been investigated in ref. 98 using the finite element method (FEM), this description is also incomplete without an accurate account of atomic-scale inhomogeneities.

In light of these challenges, in this work, we adopt a device-specific approach to comprehensively describe the effect of realistic strain inhomogeneity on coherent control of planar Ge hole qubits. In our approach, the strain originating from the random alloy disorder is obtained using the valence force field (VFF) method, which calculates the equilibrium position of the atoms in a multimillion-atom Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructure. The strain due to the gate electrodes atop the heterostructure is obtained from the thermal expansion modeling of the device in COMSOL Multiphysics. The resultant atomistic strain non-uniformity is added to the k ⋅ p effective mass model of the hole quantum dot. Our methodology can incorporate both perpendicular (out-of-plane) and parallel (in-plane) magnetic field operations of the hole spin qubit; however, the main focus of this work will be on the in-plane magnetic field operation of Ge hole qubits. This choice is motivated by the recent experiments in refs. 64,102, where it is established that the in-plane alignment of the applied B field plays a significant role in optimizing the coherence of Ge hole spin qubits. Note that, in contrast to the large bare Zeeman splitting in an out-of-plane applied B, the small g-factor of holes in an in-plane magnetic field entirely originates from SOC100,101, which in turn renders the g-tensor engineering of holes extremely sensitive to the precision of the B field orientation in experiments102,103.

The central findings of this work are as follows: (i) while the semi-analytical model incur much less computational cost than a full numerical tight binding or FEM analysis, it enables the addition of both short-range atomistic and long-range gate-induced strain for the calculated single-hole qubit Rabi frequency to benchmark well against experiments, (ii) the calculated qubit Rabi frequency shows important variation with the respective orientation between the applied in-plane magnetic field B∥ and the alternating ac electric field \({\hat{E}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\), mediated by SOC due to both random alloy disorder and gate-induced strain.

The outline of this paper is as follows. In the section titled “k ⋅ p model with inhomogeneous strain,” the effective mass k ⋅ p model is described, focusing on the implications of the uniaxial strain assumption on planar Ge hole qubit EDSR. Next, the tight-binding simulation of the planar Ge hole quantum dot atomistic wave function is outlined, and the resultant EDSR calculation is presented. A full strain profile is developed subsequently. In the section titled “Hole qubit operation in the presence of inhomogeneous strain,” the key mechanism of full-electrical qubit control in the presence of non-uniform strain is discussed. We end with our conclusions and outlook.

Results

k ⋅ p model with inhomogeneous strain

The k ⋅ p formalism describes the energy dispersion of holes in the topmost VBs of III-V semiconductors. The resultant Luttinger-Kohn Hamiltonian104 has the form:

where Jx, Jy, Jz signify the spin-3/2 Dirac matrices, γ1, γ2, γ3 are the Luttinger parameters, “c.p.” stands for cyclic permutation of the indices x → y → z → x, and anticommutation is denoted by {A, B} = (AB + BA)/2. The six-fold degeneracy of the VB at the Γ point is lifted due to the intrinsic SOC (l = 1, s = 1/2). The resultant total angular momentum eigenstates: four-fold j = 3/2 and two-fold j = 1/2 are separated by the large spin-orbit gap of Ge (Δ0 = 325 meV). The topmost VB states in the \(\left\vert j,{m}_{j}\right\rangle\) basis \(\left\{{\left\vert \frac{3}{2}\frac{3}{2}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{HH}}},{\left\vert \frac{3}{2}-\frac{3}{2}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{HH}}},{\left\vert \frac{3}{2}\frac{1}{2}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{LH}}},{\left\vert \frac{3}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\right\rangle }_{{\rm{LH}}}\right\}\) are given by the 4 × 4 picture in Eq. (1). The subscripts signify the heavy-hole (HH) and light-hole (LH) sub-bands at finite k. In the presence of an external in-plane magnetic field, the single-hole quantum dot spin qubit Hamiltonian is:

where Vconf is the Ge quantum dot (QD) confinement due to the gates and the type-I band alignment in the Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructure. The QD is defined below the top gate (TG), the electric field of which is denoted by Fz. The external B induced \({H}_{Z}=2\kappa {\mu }_{B}{\bf{B}}\cdot {\bf{J}}+2q{\mu }_{B}{\bf{B}}\cdot {\mathcal{J}}\) consists of the bulk isotropic (κ) and anisotropic (q) Zeeman interactions. Note that J = (Jx, Jy, Jz) and \({\mathcal{J}}=({J}_{x}^{3},{J}_{y}^{3},{J}_{z}^{3})\). The vector potential A due to the applied B rectifies the canonical momentum k, giving rise to additional SOC terms.

The strain Hamiltonian Hε originates due to the transformation between strained \(r^{\prime}\) and unstrained r coordinates:\(\,\,r^{{\prime} }_{\alpha }={r}_{\alpha }+{\sum }_{\beta }{\varepsilon }_{\alpha \beta }{r}_{\beta }\). This is required to describe the strained Ge band structure in terms of the known k ⋅ p material parameters of unstrained Ge. One can calculate Hε in the lowest order of perturbation theory as the Bir-Pikus-Luttinger-Kohn Hamiltonian:

where tr ε signifies the trace of the strain tensor with components εαβ. Note that in the case of spatially varying strain, there exist additional diagonal terms in Eq. (3), proportional to ∇2εαα(r)I4×4, {kα, εαβ(r)}kβI4×4 and εαβ(r)kαkβI4×4, respectively97. We have explicitly checked that these terms make a negligible contribution to our results. Moreover, our results are derived based on the k ⋅ p model incorporating Eq. (3), are in good agreement with the tight-binding calculation, which, in contrast to the Bir-Pikus picture, includes the full inhomogeneity of the strain profile. The deformation potentials have the following values: a = −2 eV, b = −2.16 eV, d = −6.06 eV105.

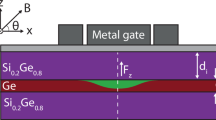

In a planar Ge hole quantum dot, such as the gate-defined QD in Fig. 1a, the out-of-plane QD confinement is much stronger than the lateral confinement. This produces a large heavy-hole-light-hole gap ΔHL ~ 50 meV, and the QD ground state becomes predominantly heavy-hole in nature. The structural inversion asymmetry (SIA) originates from the top gate field Fz, which, in conjunction with the intrinsic SOC and the external B induced Zeeman and orbital terms, contributes to the fast electrical control of the hole spin qubit100.

a With realistic gatestack, b cross-section of the design showing the 10 nm thick Ge layer between the lower and upper Ge/Si0.2Ge0.8 layers of thickness 60 nm and 10 nm, respectively. The first layer of Al source and drain gates (20 nm thick) sits atop the heterostructure, followed by a dielectric Al2O3 layer (17 nm), and a second layer of Pd/Ti electrodes (5/35 nm). The hole quantum dot forms directly under the Pd/Ti top gate(TG), as indicated by the oval shape in the Ge layer in (b). The angular orientations of the applied in-plane magnetic field B and the ac electric field \({\tilde{E}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\) with respect to the [100] crystallographic axis are denoted by θ and ϕ, respectively.

To evaluate the wave function of the hole quantum dot spin qubit, HQD is expanded in the {ψl(x), ψm(y), ψn(z)} basis, which comprises the eigenstates of a parabolic potential of radius ad in x–y, and an infinite well potential in z of length Lz = 10 nm. The n, m, l indices take integer values. Convergence of results for different gauge choices is achieved for a simulation size of n, l, m ∈ [1, 4]100. The final 256 × 256 matrix is numerically diagonalized to calculate the energy levels of the hole quantum dot: \({H}_{QD}\left\vert {\Psi }_{QD}\right\rangle ={\lambda }_{E}\left\vert {\Psi }_{QD}\right\rangle\). The heavy hole type qubit levels can be expressed as \(\left\vert {\Psi }_{QD}^{GS}\right\rangle =\left(f(x,y,z)\left\vert \frac{3}{2}\right\rangle +\,\text{LH admixtures}\,\right)\) and \(\left\vert {\Psi }_{QD}^{ES}\right\rangle =\left(g(x,y,z)\left\vert -\frac{3}{2}\right\rangle +\,\text{LH admixtures}\,\right)\), with Zeeman splitting ΔE. The atomistic hole qubit wave function can be evaluated via a tight-binding calculation, as outlined in the next section.

An applied a.c. electric field \(e{\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}(t)\cdot {\bf{r}}\) in resonance with the Larmor frequency ν = ΔE/h, π-rotates the hole spin via the electric dipole spin resonance (EDSR). The EDSR Rabi frequency is calculated as \({f}_{\pi }=\left\langle {\Psi }_{QD}^{GS}\right\vert e{\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}(t)\cdot {\bf{r}}\left\vert {\Psi }_{QD}^{ES}\right\rangle\). Following the Fig. 1a notations for \({\bf{B}}={B}_{\parallel }\left(\cos \theta ,\,\sin \theta ,\,0\right)\) and \({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}(t)={E}_{ac}\cos (2\pi {f}_{L}t)\left(\cos \phi ,\,\sin \phi ,\,0\right)\), and considering the simple case without inhomogeneity, it can be assumed that the strain in the 10-nm-wide QW is uniaxial with εxx = εyy = −0.6%. The calculated EDSR Rabi frequency for a smaller hole quantum dot of radius ad = 20 nm is maximum when \({\bf{B}}\parallel {\hat{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\), for both low (∣B∣ = 200 mT) and high (∣B∣ = 670 mT) magnetic field strength (Fig. 2e, f). In other words, the angular orientation of the in-plane magnetic field and the ac microwave drive w.r.t. x∥[100], given by θ and ϕ, respectively, affects the EDSR Rabi frequency through the scalar product relation: \({f}_{\pi }\propto \cos (\theta -\phi )\).

The angles of B and \({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\) w.r.t. the [100] axis are denoted by θ and ϕ, respectively. At Fz = 1.5 MV/m (a–d) and Fz = 15 MV/m (e–h) top-gate fields, with uniaxial strain assumption, fπ is evaluated for a smaller dot first, a, e ad = 20 nm, ∣B∣ = 200 mT, b, f ad = 20 nm, ∣B∣ = 670 mT; and then for a larger dot, c, g ad = 45 nm, ∣B∣ = 200 mT, d, h ad = 45 nm, ∣B∣ = 670 mT. Here, ad signifies the dot radius, and ∣B∣ denotes the magnitude of the applied magnetic field. As suggested by the color bars, the EDSR Rabi frequency improves with increasing the dot radius as well as the applied B strength. fπ(θ, ϕ) largely follows the trend of the dot product \({\bf{B}}\cdot {\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\). As shown in (d, h), for a large dot at a higher magnetic field, the strong orbital vector potential terms cause the fπ(θ, ϕ) trend to deviate from the dot product \({\bf{B}}\cdot {\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\) relation. The microwave drive amplitude is given by Eac = 10 kV/m.

The EDSR Rabi frequency can be calculated as \({f}_{\pi }=\frac{{\alpha }_{R3}{\bf{B}}\cdot {\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}}{{\Delta }^{2}}\) in the lowest energy heavy-hole subspace (hh1) using the Schrieffer–Wolff (SW) transformation44,88,100, where the spin-orbit coefficient αR3 originates from the SIA k-cubic Rashba 2D Hamiltonian: \({\alpha }_{R3}\left(\{{k}_{+}^{2},{k}_{-}\}{\sigma }_{+}-\{{k}_{-}^{2},{k}_{+}\}{\sigma }_{-}\right)\); and Δ denotes the splitting between the qubit levels (hh1) and the next orbital levels (hh2). For a larger dot of radius ad = 45 nm, the EDSR Rabi frequency complies with the dot product formula at low ∣B∣ (Fig. 2g); however, fπ(θ, ϕ) is non-trivial at higher ∣B∣ (Fig. 2f). This is due to the vector potential terms, which scale linearly with the magnetic field strength and the QD size (e.g., \({\bf{A}}=\frac{1}{2}{\bf{B}}\times {\bf{r}}\) in the symmetric gauge), and have a sizable effect on the SOC mediated hole qubit operation of large Ge hole QDs at high magnetic field. As described in ref. 100, the quasi-2D limit would be unable to fully capture the orbital-B effect in the lowest order of perturbation theory, due to the interplay of out-of-plane and in-plane degrees of freedom.

Tight-binding calculation

The assumption of uniaxial strain in the previous section has limited applicability in realistic devices, where hole qubit operation is significantly influenced by local features in the vicinity of the quantum dot. Using the tight-binding (TB) method, the hole qubit wave function can be calculated as a linear combination of atomic orbitals at each lattice site. Here, the multimillion-atom 3D nano-electronic modeling tool (NEMO3D) is implemented to calculate the hole QD eigen-energies and the eigen-functions, which relies on a nearest-neighbor empirical tight binding model106. The VFF calculation is incorporated into the NEMO3D tool, such that the resultant wave function encapsulates the effect of random alloy disorder.

The tight binding methodology entails selecting a basis consisting of different orbitals (such as s, p, d, and s* in the case of sp3d5s*) centered around each atom, which also form the basis for the Hamiltonian, which assumes the form:

Here \({c}_{i,\nu }^{\dagger }({c}_{i,\nu })\) is the creation(annihilation) operator of an orbital ν localized on an atom i. The terms signify the onsite orbital energies, intra-atomic orbital coupling, and inter-atomic orbital coupling, respectively106. The summation of the last term is restricted to nearest neighbors only. ϵ and t are treated as empirical fitting parameters for different materials and bond types, and they are expressed in terms of energy constants of σ and π bonds between the different atomic orbitals. In NEMO3D, the Keating model of the VFF method is applied to calculate the equilibrium position of atoms in the Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructure107. Contrasting to the continuum elastic theory-based models, the resultant strain profile in NEMO3D captures the random alloy disorder, i.e., the effect of the random positioning of the Si atoms in the “buffer” SiGe layers subjected to the inter-atomic potential. For a 10 nm wide Ge QW with 60 nm Si0.2Ge0.8 buffer simulated below and 10 nm Si0.2Ge0.8 above, a snippet of the VFF calculated atomic displacement field at equilibrium is shown in Fig. 3a. Importantly, due to interdiffusion98, εzz relaxes to 0.5% over the length of ~3 nm at the Si0.2Ge0.8/Ge interface. The fluctuation of εxy, εxz, εyz results in na on-zero shear strain gradient in the QW (Fig. 3b). For ∣B∣ = 670 mT, the tight-binding simulation of the hole EDSR Rabi frequency follows a different trend than that of the uniaxial strain model. In fact, Fig. 3c signifies the emergence of an asymmetric product relation: \({f}_{\pi }\propto \sin (\theta +\phi )\). The different optimum orientation of fπ compared to the uniaxial k ⋅ p calculation indicates a different SOC mechanism for hole EDSR to the cubic Rashba or the orbital-B, originating from the random alloy disorder in realistic devices. The wave function obtained from TBA includes the effect of random alloy disorder, and notably, the maximum fπ shows a ~5× improvement in Fig. 3c over the uniaxial strain calculation (Fig. 2d, h).

a With random alloy disorder induced displacement vector field data of Ge atoms, calculated via the valence force field method. On the top panel, displacement amplitudes over a 150 × 150 × 10 nm3 box around the quantum dot with in-plane radius ad = 45 nm and quantum well width Lz = 10 nm are shown. A small section at the center of the dot is magnified to elaborate the randomness close to the buffer interfaces, as well as the variation of the displacement magnitudes across the quantum well. b Variation of the uniaxial strain tensor components εxx, εyy, εzz, and shear strain tensor components εxy, εxz, εyz with z (across the QW). c NEMO3D simulation of hole EDSR Rabi frequency at the top-gate field Fz = 1.5 MV/m (top) and Fz = 15 MV/m (bottom). The external magnetic field is ∣B∣ = 670 mT. The fπ(θ, ϕ) trend shows a stark difference compared to the uniaxial case. The microwave drive amplitude is ∣Eac∣ = 10 kV/m.

Non-uniform strain due to gate electrodes

While the tight-binding simulation takes into account the inhomogeneity of the quantum dot confinement as well as the short-range strain fluctuations, it does not incorporate effects stemming from the contraction of the metal gate-stack atop the heterostructure. Besides, large-scale tight-binding simulations would incur a huge computational cost. In this work, a simpler and faster method based on the k ⋅ p model is adopted, where the atomistic strain due to the random alloy disorder and the gate-induced strain at cryogenic temperature are added as a spatially varying profile εαβ(x, y, z) in Hε (Eq. 3). A single Ge dot is modeled after ref. 30 with the following gatestack parameters: 20 nm thick Al electrodes annealed atop the QW as source and drain to manipulate hole occupancy in the Ge layer, followed by a 17 nm layer of dielectric Al2O3. The final layer consists of Ti/Pd metal electrodes of thickness 5/35 nm, defining the quantum dot confinements. A qualitative sketch of the gatestack is given in Fig. 1b. Thermal strain arises at cryogenic experimental conditions due to the difference in contraction between the gatestack and the heterostructure, which is calculated using the FEM enabled in the thermal expansion and heat transfer modules of COMSOL Multiphysics with appropriate layered geometry and accurate material parameters. In Fig. 4, the thermal strain is superimposed on the strain due to random alloy disorder, highlighting the short-range and long-range fluctuations in the strain tensor components94.

The spatial profile of the strain tensor components εij(x, y) in the Ge layer (z = 60 nm cut) of the device in Fig. 1 due to random alloy disorder as well as gate contraction. The features along the y-axis here are due to the Al source and drain electrodes, as shown in Fig. 1 schematic. The atomic granularity comes from the random alloy disorder, while the long-range feature due to the gate contractions is signified by the COMSOL mesh data superimposed atop the atomistic VFF data.

Hole qubit operation in the presence of inhomogeneous strain

Complete knowledge of the inhomogeneous strain profile εαβ(x, y, z) becomes important in the context of hole qubit properties mediated by SOC. The assumption of a uniaxial strain tensor only renormalizes the heavy hole-light hole gap in theory, but does not capture important phenomena in realistic devices: e.g., large anisotropy or site dependence of the g tensor102,108. Recently, Si and Ge hole qubits have reported improved control and fidelity in a multidot system by harnessing the strain inhomogeneity across the QDs and precise magnetic field orientation64,102,109,110. With inhomogeneous strain, the EDSR Rabi frequency is calculated with the revised strain matrix elements of the k ⋅ p model: \(\left\langle {\Psi }_{l}(x){\Psi }_{m}(y){\Psi }_{n}(z)\right\vert {\varepsilon }_{\alpha \beta }(x,y,z)\left\vert {\Psi }_{l{\prime} }(x){\Psi }_{m{\prime} }(y){\Psi }_{n{\prime} }(z)\right\rangle\). Following the 3d k ⋅ p model description, in the {Ψl(x), Ψm(y), Ψn(z)} basis with the simulation size n, l, m ∈ [1, 4], the resultant Hε Hamiltonian is a 256 × 256 matrix. The modified eigenstates and eigenvalues of the total Hamiltonian in Eq. (2) capture the effect of cumulative non-uniformity. The fπ obtained lies in the range ~(30–300) MHz, with at least an order of magnitude improvement over the uniaxial assumption, and in much better agreement with experiments. The fπ(θ, ϕ) variation is shown in Fig. 5b.

For a circular dot of radius ad = 45 nm, a the qubit g-factor is anisotropic and exhibits a large ~π/4 rotation of the principal axes. For all subfigures a–e, the top and bottom panels signify results for Fz = 1.5 MV/m and Fz = 15 MV/m, respectively. b At ∣B∣ = 670 mT, fast EDSR is predicted with gate time ~10 ns, and a similar fπ(θ, ϕ) trend to the tight binding calculation is observed. Here, ∣Eac∣ = 10 kV/m. c The ∝ ∣B∣2 variation of the hole qubit dephasing rate (\({({T}_{2,RTN}^{* })}^{-1}\)) due to the random telegraph noise from a single charge defect, with uniaxial strain (red) and inhomogeneous strain (green). The single charge defect is assumed to be situated at \((50\sqrt{2},50\sqrt{2},0)\). d The linear variation of the EDSR Rabi frequency fπ w.r.t. the magnetic field strength ∣B∣. In the presence of strain inhomogeneity (denoted by “ih” on the green axes), fπ is ~100× higher than the uniaxial strain scenario (red). e Relaxation rate (Γ1) as a function of magnetic field strength.

Planar hole quantum dots can often be described in the quasi-2D limit (Lz ≪ ad), since the large heavy hole-light hole gap implies that, along with the top gate and orbital-B induced HH-LH matrix elements, inhomogeneous strain can also be treated perturbatively.

For a circular quantum dot, the hole EDSR Rabi frequency in the quasi-2D limit is evaluated as:

In Eq.(5), the first term is the structural inversion asymmetric (SIA) Rashba, and strain inhomogeneity results in the next four terms, via both SIA linear-k Rashba \({\epsilon }_{xy}^{{\prime} }{k}_{x}{\sigma }_{y}+{\epsilon }_{yx}^{{\prime} }{k}_{y}{\sigma }_{x}\) and bulk inversion asymmetric Dresselhaus \({\epsilon }_{xx}^{{\prime} }{k}_{x}{\sigma }_{x}+{\epsilon }_{yy}^{{\prime} }{k}_{y}{\sigma }_{y}\) interactions1. Here \({\epsilon }_{ij}^{{\prime} }\) consists of the strain gradients ∂ε/∂r, and the angular functions \({f}_{i}^{\theta ,\phi }\) describe the fπ dependence on the respective magnetic field and microwave drive angles θ and ϕ. Using the SW transformation, detailed expressions for \({\alpha }_{R3},\,{\epsilon }_{ij}^{{\prime} }\) and the angular functions \({f}_{i}^{\theta ,\phi }\) can be calculated (see Supplementary). The subsequent \({f}_{i}^{\theta ,\phi }\) plots suggest that the EDSR rate dependence on the B and \({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{{\rm{ac}}}\) orientation boils down to the following relation:

where, \({f}_{\pi }^{0}=({\alpha }_{R}| B| | {E}_{ac}| )/{\Delta }^{2}\), with the accumulated Rashba coefficient \({\alpha }_{R}=\left({\alpha }_{R3}+{\epsilon }_{R}^{{\prime} }\right)\). Dimensionless ratios \({r}_{1}={\epsilon }_{{D}_{xy}}^{{\prime} }/{\alpha }_{R}\) and \({r}_{2}={\epsilon }_{{D}_{yx}}^{{\prime} }/{\alpha }_{R}\) denote the relative contribution of the Dresselhaus SOC w.r.t. the Rashba SOC. When strain inhomogeneity is absent, r1, r2 and \({\epsilon }_{R}^{{\prime} }\) become zero, and αR is maximum when ∣θ−ϕ∣ = (n−1)π; matching the result in Fig. 2. Note that fitting the plot in Fig. 2h would require a perturbative analysis in higher order of B to account for the orbital effect.

In summary, inhomogeneous strain induces the linear-k Rashba contribution \({\epsilon }_{R}^{{\prime} }\) as well the \({\epsilon }_{{D}_{xy}}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\epsilon }_{{D}_{yx}}^{{\prime} }\) linear-k Dresselhaus contributions, with Dresselhaus terms ultimately dominating the EDSR Rabi frequency when a realistic strain profile is considered. The large g-factor anisotropy, as well as rotation of the principal g-tensor, is observed when strain non-uniformity is present (Fig. 5a). Gate-induced thermal strain is responsible for the significant tuneability of the qubit g-tensor, making certain gate optimization possible32. Figure 5b demonstrates the strong presence of the Dresselhaus SOC at low as well as high top-gate fields. The variation of the qubit timescales with magnetic field strength is plotted next, with Fig. 5c showing that inclusion of the full strain profile results in a higher RTN dephasing rate \({({T}_{2,RTN}^{* })}^{-1}\), with roughly a ∝ B2 dependence. The EDSR Rabi frequency varies linearly with the magnetic field strength (Fig. 5d), and with strain inhomogeneity, fπ improves by a factor of >10× over uniaxial strain calculation. At the same time, the phonon-mediated relaxation rate Γ1 increases nonlinearly with ∣B∣ (Fig. 5e). For a more complete understanding of the hole spin qubit decoherence, in a future publication, we will carry out an extended study of the effect of an ensemble of defects with the full strain profile, along the lines of ref. 111. With uniform uniaxial strain, the effect of the top-gate field on fπ is significant100. At an optimal Fz = 15 MV/m the EDSR Rabi frequency is improved by an order of magnitude compared to that at Fz = 1.5 MV/m (Fig. 5d), while the change in relaxation and RTN dephasing rates w.r.t. Fz is smaller. However, in the presence of strain inhomogeneity, the strain-induced SOC dominates, hence similar results are obtained for low and high top-gate fields for all of the timescales.

Discussion

We have modeled a hole quantum dot in the Ge layer of a Ge/Si1−xGex heterostructure using both the k ⋅ p and the tight binding frameworks independently, to analyze the effect of a realistic strain profile on the spectrum and operation of planar Ge hole qubits. We have identified that realistic strain inhomogeneity produces non-vanishing shear strain gradients across the Ge quantum dot, which leads to a k-linear Dresselhaus interaction, among other features. Our tight-binding calculation shows ~ 5x increase in the maximum EDSR Rabi frequency. In our k ⋅ p model, including both random alloy disorder-induced strain via VFF calculation and metal gate-induced strain via COMSOL, we demonstrate>10x improved hole EDSR Rabi frequency compared to the uniaxial strain assumption, in better agreement with experimental observations.

We have successfully accomplished our primary objective of integrating disorder and strain into the theoretical modeling of planar Ge hole qubits and gaining deeper insights into the resulting variability. This work advances the field in two significant and novel ways: (1) in the invariant decomposition of the spin density matrix for spin-3/2 holes45 feature quadrupole terms ∝ J2, unique for holes with no counterpart in spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) systems. The quadrupole terms are responsible for the heavy hole-light hole splitting and heavy hole-light hole coupling. For planar Ge heavy hole qubits operated at a top-gate field, the quadrupole terms give rise to Rashba SOC. In addition to this, the spatially varying strain has a non-trivial interaction with the quadrupole, which dominantly governs the spin dynamics of holes. The conceptual novelty of our work is that by efficiently adding the realistically disordered strain field across the QD, the 3d model captures the non-trivial mixing and the resultant inhomogeneous electric field the qubit experiences while resonant driving, and identifies the most dominant physical mechanism in hole qubit operation. (2) Existing models, such as the finite-element-based k.p approach in ref. 1 employs a FEM-based k.p model, which successfully allows for the thermal contraction of the metal gatestack, but doesn’t include the atomic-scale fluctuation due to random alloy disorder. Tight-binding calculation-based modeling considers the alloy disorder, but so far has not taken gate contraction into account. Our approach combines both: by embedding atomistic disorder within a realistic 3d strain profile obtained from a thermomechanical model, we capture the full spectrum of inhomogeneities for the first time. This enables us to identify the precise spatial mechanisms that dominate Ge hole spin qubit behavior under realistic driving fields. More importantly, the validity of effective 2D models with inhomogeneous strain is determined by the length scale of strain field variation. If strain varies on a larger length scale (gate-induced strain, for example, varies on a length scale compared to QW dimensions), the smooth gradient implies a valid perturbative treatment. However, the realistic strain profile includes both long-range and atomic-scale variations, which necessitates a full 3d approach.

Improving on these insights requires an extended benchmarking study over multiple architectures. Multiphysics calculations of planar Ge heterostructures with various buffer widths, SiGe compositions, or randomness would be vital in future studies of hole spin qubits. In this regard, we present an additional case study of a double-dot setup (Supplementary Fig. 3) in Ge in the Supplementary Note 1. We calculate a realistic inhomogeneous strain profile across the double dot for different buffer SiGe widths (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also show the different degrees of the in-plane g-tensor rotation for the two QDs (Supplementary Fig. 4), capturing dot-to-dot variation of hole qubit properties and constituting building blocks for optimizing Δg induced oscillation, two-axis control, and entanglement. A direct extension of our model could comprehensibly describe large g-tensor modulation and rotation of Si single dot hole qubits, as well as double-dot Si hole systems. Similarly, nanowires and hut-wire qubits in Si and Ge systems can be modeled using an appropriate set of basis states and dot dimensions in our code.

Methods

Most of the results are obtained by theoretical analysis, following the effective mass approximation theory. For the perturbative analysis of electron dipole spin resonance (EDSR), we use the SW transformation on the 3d k ⋅ p Hamiltonian. The Supplementary Note 1 details more information on the analytical formulas of this procedure.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Abadillo-Uriel, J. C., Rodríguez-Mena, E. A., Martinez, B. & Niquet, Y.-M. Hole-spin driving by strain-induced spin-orbit interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 097002 (2023).

Benioff, P. The computer as a physical system: a microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers as represented by Turing machines. J. Stat. Phys. 22, 563–591 (1980).

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Deutsch, D. & Penrose, R. Quantum theory, the Church-Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proc. R. Soc. London A Math. Phys. Sci. 400, 97–117 (1985).

Kane, B. E. A silicon-based nuclear spin quantum computer. Nature 393, 133–137 (1998).

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120–126 (1998).

Elzerman, J. M. et al. Single-shot read-out of an individual electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 430, 431–435 (2004).

Petta, J. R. et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science 309, 2180–2184 (2005).

Hanson, R., Kouwenhoven, L. P., Petta, J. R., Tarucha, S. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Spins in few-electron quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 1217–1265 (2007).

Chatterjee, A. et al. Semiconductor qubits in practice. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 157–177 (2021).

Vandersypen, L. M. K. et al. Interfacing spin qubits in quantum dots and donors—hot, dense, and coherent. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 34 (2017).

Lawrie, W. et al. Quantum dot arrays in silicon and germanium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 080501 (2020).

Van Riggelen, F. et al. A two-dimensional array of single-hole quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 044002 (2021).

DiVincenzo, D. P. The physical implementation of quantum computation. Fortschr. Phys. 48, 771–783 (2000).

Zwanenburg, F. A. et al. Silicon quantum electronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 961 (2013).

Scappucci, G. et al. The germanium quantum information route. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 926–943 (2021).

Itoh, K. et al. High purity isotopically enriched 70Ge and 74Ge single crystals: Isotope separation, growth, and properties. J. Mater. Res. 8, 1341–1347 (1993).

Itoh, K. M. et al. High purity isotopically enriched 29Si and 30Si single crystals: isotope separation, purification, and growth. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 6248 (2003).

Yoneda, J. et al. A quantum-dot spin qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9%. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 102–106 (2018).

Tyryshkin, A. M. et al. Electron spin coherence exceeding seconds in high-purity silicon. Nat. Mater. 11, 143–147 (2012).

Prechtel, J. H. et al. Decoupling a hole spin qubit from the nuclear spins. Nat. Mater. 15, 981–986 (2016).

Bosco, S. & Loss, D. Fully tunable hyperfine interactions of hole spin qubits in Si and Ge quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 190501 (2021).

Cardona, M. & Peter, Y. Y. Fundamentals of semiconductors Vol. 619 (Springer, 2005).

Tahan, C. & Joynt, R. Relaxation of excited spin, orbital, and valley qubit states in ideal silicon quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075302 (2014).

Hu, Y., Kuemmeth, F., Lieber, C. M. & Marcus, C. M. Hole spin relaxation in Ge–Si core–shell nanowire qubits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 47–50 (2012).

Chesi, S., Wang, X. J. & Coish, W. Controlling hole spins in quantum dots and wells. Eur. Phys. J. 129, 1–16 (2014).

Maurand, R. CMOS silicon spin qubit. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–6 (2016).

Bohuslavskyi, H. et al. Pauli blockade in a few-hole PMOS double quantum dot limited by spin-orbit interaction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 193101 (2016).

Vukušić, L. et al. Single-shot readout of hole spins in Ge. Nano Lett. 18, 7141–7145 (2018).

Hendrickx, N. et al. Gate-controlled quantum dots and superconductivity in planar germanium. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–7 (2018).

Lawrie, W. I. L. et al. Spin relaxation benchmarks and individual qubit addressability for holes in quantum dots. Nano Lett. 20, 7237–7242 (2020).

Liles, S. et al. Electrical control of the g tensor of the first hole in a silicon MOS quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 104, 235303 (2021).

Piot, N. et al. A single hole spin with enhanced coherence in natural silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1072–1077 (2022).

Camenzind, L. C. et al. A hole spin qubit in a fin field-effect transistor above 4 Kelvin. Nat. Electron 5, 178 (2022).

Pioro-Ladriere, M. et al. Electrically driven single-electron spin resonance in a slanting Zeeman field. Nat. Phys. 4, 776–779 (2008).

Pribiag, V. et al. Electrical control of single hole spins in nanowire quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 170–174 (2013).

Voisin, B. et al. Electrical control of g-factor in a few-hole silicon nanowire MOSFET. Nano Lett. 16, 88–92 (2016).

Srinivasan, A. et al. Electrical control of the sign of the g factor in a GaAs hole quantum point contact. Phys. Rev. B 94, 041406 (2016).

Hung, J.-T., Marcellina, E., Wang, B., Hamilton, A. R. & Culcer, D. Spin blockade in hole quantum dots: Tuning exchange electrically and probing Zeeman interactions. Phys. Rev. B 95, 195316 (2017).

Marcellina, E. et al. Electrical control of the Zeeman spin splitting in two-dimensional hole systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 077701 (2018).

Venitucci, B. & Niquet, Y.-M. Simple model for electrical hole spin manipulation in semiconductor quantum dots: Impact of dot material and orientation. Phys. Rev. B 99, 115317 (2019).

Gao, F. et al. Site-controlled uniform Ge/Si hut wires with electrically tunable spin–orbit coupling. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906523 (2020).

Rashba, E. & Sherman, E. Y. Spin-orbital band splitting in symmetric quantum wells. Phys. Lett. A 129, 175–179 (1988).

Winkler, R. Spin-orbit Coupling Effects in Two-Dimensional Electron and Hole Systems Vol. 191 (Springer, 2003).

Winkler, R. Spin density matrix of spin-3/2 hole systems. Phys. Rev. B 70, 125301 (2004).

Culcer, D., Lechner, C. & Winkler, R. Spin precession and alternating spin polarization in spin-3/2 hole systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 106601 (2006).

Marcellina, E., Hamilton, A., Winkler, R. & Culcer, D. Spin-orbit interactions in inversion-asymmetric two-dimensional hole systems: a variational analysis. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075305 (2017).

Katsaros, G. et al. Zero field splitting of heavy-hole states in quantum dots. Nano. Lett. 20, 5201 (2020).

Golovach, V. N., Borhani, M. & Loss, D. Electric-dipole-induced spin resonance in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 74, 165319 (2006).

Nadj-Perge, S., Frolov, S., Bakkers, E. & Kouwenhoven, L. P. Spin–orbit qubit in a semiconductor nanowire. Nature 468, 1084–1087 (2010).

Tanttu, T. et al. Controlling spin-orbit interactions in silicon quantum dots using magnetic field direction. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021028 (2019).

Adelsberger, C., Benito, M., Bosco, S., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Hole-spin qubits in Ge nanowire quantum dots: Interplay of orbital magnetic field, strain, and growth direction. Phys. Rev. B 105, 075308 (2022).

Dimoulas, A., Tsipas, P., Sotiropoulos, A. & Evangelou, E. Fermi-level pinning and charge neutrality level in germanium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 252110 (2006).

Sammak, A. et al. Shallow and undoped germanium quantum wells: a playground for spin and hybrid quantum technology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807613 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Coupling a germanium hut wire hole quantum dot to a superconducting microwave resonator. Nano Lett. 18, 2091–2097 (2018).

Vigneau, F. et al. Germanium quantum-well Josephson field-effect transistors and interferometers. Nano Lett. 19, 1023–1027 (2019).

Xu, G. et al. Dipole coupling of a hole double quantum dot in germanium hut wire to a microwave resonator. New J. Phys. 22, 083068 (2020).

Aggarwal, K. et al. Enhancement of proximity-induced superconductivity in a planar Ge hole gas. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, L022005 (2021).

Yu, C. X. et al. Strong coupling between a photon and a hole spin in silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 741–746 (2023).

Valentini, M. et al. Parity-conserving Cooper-pair transport and ideal superconducting diode in planar germanium. Nat Commun. 15, 169 (2024).

Froning, F. et al. Strong spin-orbit interaction and g-factor renormalization of hole spins in Ge/Si nanowire quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013081 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Optimal operation points for ultrafast, highly coherent Ge hole spin-orbit qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 1–8 (2021).

Bosco, S., Hetenyi, B. & Loss, D. Hole spin qubits in Si FinFETs with fully tunable spin-orbit coupling and sweet spots for charge noise. PRX Quantum 2, 010348 (2021).

Hendrickx, N. et al. Sweet-spot operation of a germanium hole spin qubit with highly anisotropic noise sensitivity. Nat. Mater. 23, 920–927 (2024).

Fang, Y., Philippopoulos, P., Culcer, D., Coish, W. & Chesi, S. Recent advances in hole-spin qubits. Mater. Quantum Technol. 3, 012003 (2023).

Awschalom, D. D. & Flatté, M. E. Challenges for semiconductor spintronics. Nat. Phys. 3, 153–159 (2007).

Yang, C. et al. Silicon qubit fidelities approaching incoherent noise limits via pulse engineering. Nat. Electron. 2, 151–158 (2019).

Kawakami, E. et al. Electrical control of a long-lived spin qubit in a Si/SiGe quantum dot. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 666–670 (2014).

Zajac, D. M. et al. Resonantly driven CNOT gate for electron spins. Science 359, 439–442 (2018).

Klemt, B. et al. Electrical manipulation of a single electron spin in CMOS using a micromagnet and spin-valley coupling. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 107 (2023).

Mizokuchi, R., Maurand, R., Vigneau, F., Myronov, M. & De Franceschi, S. Ballistic one-dimensional holes with strong g-factor anisotropy in germanium. Nano Lett. 18, 4861–4865 (2018).

Stehouwer, L. E. et al. Germanium wafers for strained quantum wells with low disorder. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 092101 (2023).

Dsouza, K., Del Vecchio, P., Rotaru, N., Moutanabbir, O. & Vashaee, D. Heavy hole vs. light hole spin qubits: a strain-driven study of SiGe/Ge and GeSn/Ge. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.16734 (2024).

Wei, H., Mizoguchi, S., Mizokuchi, R. & Kodera, T. Estimation of hole spin g-factors in p-channel silicon single and double quantum dots towards spin manipulation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SGGI10 (2020).

Ares, N. et al. Nature of tunable hole g factors in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 046602 (2013).

Wang, K. et al. Ultrafast coherent control of a hole spin qubit in a germanium quantum dot. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–6 (2022).

Jirovec, D. singlet-triplet hole spin qubit in planar Ge. Nat. Mater. 20, 1106–1112 (2021).

Geyer, S. et al. Anisotropic exchange interaction of two hole-spin qubits. Nat. Phys. 20, 1152–1157 (2024).

Hendrickx, N. et al. A single-hole spin qubit. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–6 (2020).

Hendrickx, N., Franke, D., Sammak, A., Scappucci, G. & Veldhorst, M. Fast two-qubit logic with holes in germanium. Nature 577, 487–491 (2020).

Hendrickx, N. W. et al. A four-qubit germanium quantum processor. Nature 591, 580–585 (2021).

Borsoi, F. et al. Shared control of a 16 semiconductor quantum dot crossbar array. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 21–27 (2024).

Dobbie, A. et al. Ultra-high hole mobility exceeding one million in a strained germanium quantum well. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 172108 (2012).

Lodari, M. et al. Lightly strained germanium quantum wells with hole mobility exceeding one million. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 122104 (2022).

Lodari, M. et al. Light effective hole mass in undoped Ge/SiGe quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 100, 041304 (2019).

Lodari, M. et al. Low percolation density and charge noise with holes in germanium. Mater. Quantum Technol. 1, 011002 (2021).

Bulaev, D. V. & Loss, D. Electric dipole spin resonance for heavy holes in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 097202 (2007).

Kloeffel, C., Rančić, M. J. & Loss, D. Direct Rashba spin-orbit interaction in Si and Ge nanowires with different growth directions. Phys. Rev. B 97, 235422 (2018).

Bosco, S. et al. Phase-driving hole spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 197001 (2023).

Fischer, J., Coish, W., Bulaev, D. & Loss, D. Spin decoherence of a heavy hole coupled to nuclear spins in a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 78, 155329 (2008).

Mauro, L., Rodríguez-Mena, E. A., Bassi, M., Schmitt, V. & Niquet, Y.-M. Geometry of the dephasing sweet spots of spin-orbit qubits. Phys. Rev. B 109, 155406 (2024).

Shalak, B., Delerue, C. & Niquet, Y.-M. Modeling of spin decoherence in a Si hole qubit perturbed by a single charge fluctuator. Phys. Rev. B 107, 125415 (2023).

Qvist, J. H. & Danon, J. Anisotropic g-tensors in hole quantum dots: Role of transverse confinement direction. Phys. Rev. B 105, 075303 (2022).

Corley-Wiciak, C. et al. Nanoscale mapping of the 3D strain tensor in a germanium quantum well hosting a functional spin qubit device. Mater. Interfaces 15, 3119–3130 (2023).

Sherman, E. Y. & Lockwood, D. Spin relaxation in quantum dots with random spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 72, 125340 (2005).

Bindel, J. R. et al. Probing variations of the Rashba spin–orbit coupling at the nanometre scale. Nat. Phys. 12, 920–925 (2016).

Secchi, A. & Troiani, F. Envelope-function theory of inhomogeneous strain in semiconductor nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 110, 045420 (2024).

Rodríguez-Mena, E. A. et al. Linear-in-momentum spin orbit interactions in planar Ge/GeSi heterostructures and spin qubits. Phys. Rev. B 108, 205416 (2023).

Terrazos, L. et al. Theory of hole-spin qubits in strained germanium quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 103, 125201 (2021).

Sarkar, A. et al. Electrical operation of planar Ge hole spin qubits in an in-plane magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 108, 245301 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Electrical operation of hole spin qubits in planar MOS silicon quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 109, 075427 (2024).

Wang, C.-A. et al. Operating semiconductor quantum processors with hopping spins. Science 385, 447–452 (2024).

van Riggelen-Doelman, F. et al. Coherent spin qubit shuttling through germanium quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 15, 5716 (2024).

Luttinger, J. M. & Kohn, W. Motion of Electrons and Holes in Perturbed Periodic Fields. Phys. Rev. 97, 869–883 (1955).

Wortman, J. & Evans, R. Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio in silicon and germanium. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 153–156 (1965).

Klimeck, G. et al. Atomistic simulation of realistically sized nanodevices using NEMO 3-D-Part I: models and benchmarks. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 54, 2079–2089 (2007).

Klimeck, G., Oyafuso, F., Boykin, T. B., Bowen, R. C. & von Allmen, P. Development of a nanoelectronic 3-D (NEMO 3-D) simulator for multimillion atom simulations and its application to alloyed quantum dots. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 3, 601–642 (2002).

John, V. et al. A two-dimensional 10-qubit array in germanium with robust and localised qubit control. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.16044 (2024).

Liles, S. et al. A singlet-triplet hole-spin qubit in planar silicon. Nat. Commun. 15, 7690 (2024).

Rooney, J. et al. Gate modulation of the hole singlet-triplet qubit frequency in germanium. npj Quantum Inf. 11, 15 (2025).

Wang, Z., Gholizadeh, S., Hu, X., Das Sarma, S. & Culcer, D. Dephasing of planar Ge hole spin qubits due to 1/f charge noise. Phys. Rev. B 111, 155403 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by the Australian Research Council Center of Excellence in Future Low-Energy Electronics Technologies (project number CE170100039) and the Fellowship IL230100072.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. (Abhikbrata) wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures. A.S. (Abhikbrata) and P.C. carried out the numerical simulations and analytical calculations. D.C., X.H., and A.S. (Andre) devised and supervised the theoretical modeling. A.R.H. and A.S.D. supervised the experimental application of the project. R.R. supervised the numerical simulation. D.C. conceived the paper. All authors planned and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, A., Chowdhury, P., Hu, X. et al. Effect of disorder and strain on the operation of planar Ge hole spin qubits. npj Quantum Inf 11, 185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01130-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01130-w