Abstract

Vanadium dioxide (VO2) is a prototypical material that undergoes a structural phase transition (SPT) from a monoclinic (M1) to rutile (R) structure and an insulator-to-metal transition (IMT) when heated above 340 K or excited by an ultrafast laser pulse. Due to the strong electron–electron and electron–lattice interactions, modeling the ultrafast IMT in VO2 has proven challenging. Here, we develop an efficient theoretical approach to the light-induced phase transitions by combining a tensor network ansatz for the electrons with a semiclassical description of the nuclei. Our method is based on a quasi-one-dimensional model for the material with the important multiorbital character, electron–lattice coupling, and electron–electron correlations being included. We benchmark our method by showing that it qualitatively captures the ground state phase diagram and finite-temperature phase transitions of VO2. Then, we use the hybrid quantum-classical tensor network approach to simulate the dynamics following photoexcitation. We find that the structure can transform faster than the harmonic phonon modes of the M1 phase, suggesting lattice nonlinearity is key in the SPT. We also find separate timescales in the evolution of dimerization and tilt lattice distortions, as well as the loss and subsequent partial restoration behavior of the displacements, explaining the complex dynamics observed in recent experiments. Moreover, decoupled SPT and IMT dynamics are observed, with the IMT occurs quasi-instantaneously. Our model and approach, which can be extended to a wide range of materials, reveal the unexpected non-monotonic transformation pathways in VO2 and pave the way for future studies of non-thermal phase transformations in quantum materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The strong interactions within and between the electronic, lattice, and spin degrees of freedom in strongly correlated materials lead to a wide range of emergent properties and phase transitions but also make them difficult to understand. One of the archetypal strongly correlated materials, vanadium dioxide (VO2) is a transition-metal compound which undergoes a first-order transition from the insulating phase to the metallic phase at Tc ≈340 K and ambient pressure1,2,3,4. Coinciding with this insulator-to-metal transition (IMT), a structural phase transition (SPT) also occurs from the low-temperature distorted monoclinic (M1) phase to the high-temperature undistorted rutile (R) stucture5,6,7. Due to the strong correlations between the internal charge, orbital, and lattice degrees of freedom, the underlying mechanism of these transitions in VO2 is still under debate8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In particular, it remains unclear whether the transition is best described as a Peierls-like transition driven by the structure change of lattice16 or as a Mott-like transition driven by the electron–electron correlations17.

On the other hand, nonequilibrium phase transitions in materials induced by ultrafast light pulses are attracting considerable attention and represent a rapidly developing field in condensed matter physics18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, as they offer an efficient way to tune and control material properties on ultrafast timescales. In VO2, intense laser pulses can suddenly change the potential energy surface of the lattice through electronic excitation and drive the ultrafast SPT and IMT26,27. As, in principle, the lattice and electronic degrees of freedom can respond on different timescales, the light-induced phase transition has become one of the key tools to address the nature of IMT28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Early experiments highlighted the role of lattice distortions in the light-induced IMT26,44, but more recent studies suggest that the IMT is faster than the SPT and emphasize the importance of electron–electron correlations45,46,47,48. In a recent experiment49, the complete structural and electronic nature of light-induced phase transitions in VO2 have been resolved at their fundamental timescales using ultra-broadband few-femtosecond spectroscopy. In addition to a quasi-instantaneous IMT, a much more complex pathway in the light-induced phase transitions was observed.

However, in contrast to these experimental advances, there have been very limited theoretical studies on the nonequilibrium phase transition in VO2. This is naturally due to the complexity of treating even the normal thermal transition in VO2, and so most studies have used simplified static models46,47,50 or structural only models37 to interpret the transient signatures. Only recently has time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) been applied to the problem51,52, but the use of DFT to describe VO2 has often been controversial due to the neglect of electron–electron interactions. The complexity of uncovering the important couplings from DFT has also motivated the use of simplified models in the past53. Furthermore, these works predict transformation times that are strongly dependent on the excitation fraction and initial temperature, an effect not seen in recent ultrafast X-ray diffraction studies37,54,55.

To overcome these limitations and provide a more transparent model, here we present a tensor network study of the light-induced phase transitions using a simplified quasi-one-dimensional model for VO2, taking into account the important physical ingredients: the multiorbital character, electron–lattice coupling, and electron–electron correlations. We show that this model qualitatively captures the equilibrium properties of VO2 by calculating the ground state phase diagram and finite-temperature phase transitions. When the light pulse is applied to the system, a hybrid quantum-classical tensor-network method is used to simulate the dynamics. We find that the structure can transform faster than the corresponding harmonic phonon modes of the M1 phase, suggesting the nonlinearity of lattice potential is key in the SPT. We also find separate timescales for the evolution of dimerization and tilt distortions in the lattice dynamics, and that the displacements exhibit a loss and subsequent partial restoration behavior, which can provide an explanation for the complex dynamics observed in ref. 49. Moreover, decoupled SPT and IMT dynamics are observed, where the initial M1 structure transforms to the R one in tens of femtoseconds, while the IMT occurs quasi-instantaneously. These results support the recent experimental findings and provide key insights into the light-induced phase transitions in VO2. Our model and approach, which treat the electronic degrees of freedom in a true many-body way, can be extended to other systems like charge-density wave systems or charge transfer salts in which strong electron–electron and electron–lattice interactions are key, and thus will advance the study of light-induced phenomena far beyond VO2.

Results

Model

Our model for VO2 is inspired by the earlier static model of ref. 53. In VO2, the vanadium 3d orbitals hybridize and split under the action of the crystal field. The relevant orbitals to the IMT and SPT are the a1g singlet and \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) doublet (equivalently and often referred to as such in the literature, d∣∣ singlet, and π* doublet). Since the crucial aspect is the distinction between a1g and \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbitals based on their bonding character with the ligands and response to the atomic displacements, like ref. 53, we consider only one \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbital to simplify the theoretical model without losing the important physics of VO2. As the Peierls instability of VO2 mainly occurs along the cR axis connecting adjacent vanadium ions through the dimerization and tilting displacement, which splits the a1g orbital into subbands and shifts the \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbital, it is widely accepted that VO2 can be described by a one-dimensional a1g band embedded in a three-dimensional background of \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) states17. For instance, it has been shown that for the optical response, VO2 behaves like an effective one-dimensional electronic compound56,57, while structural studies also support that the transition can be described in this reduced state37,58. Thus, we model the vanadium dioxide as a quasi-one-dimensional system, for which the lattice displacement X ≡ (X1, X2) is introduced to capture the dimerizing displacement along the cR axis and the band-splitting tilting displacement perpendicular to the cR axis, respectively; see Fig. 1. The total Hamiltonian for this simplified model of VO2 with the coupling to lattice degrees of freedom is given by

The quasi-one-dimensional treatment of the \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) states may renormalize the interaction strength due to the changed density of states, but will not affect the underlying important interactions with the lattice and a1g orbitals. As we will shortly show, we treat the electronic component fully quantum mechanically, while treating the nuclei classically, leading to a “semi-quantum” approach.

Here the red (blue) spheres represent vanadium (oxygen) atoms. In the rutile R phase (left), the vanadium atoms are located at the center of the octahedrons made of oxygen atoms. The finite X1 and X2 lattice distortions characterize the monoclinic M1 phase (right), where the X1 component captures the dimerization along the cR axis, and the X2 component acts as a tilting perpendicular to the cR axis.

Concretely, the purely electronic component reads

where a = 1, 2 denotes the a1g and \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbital, respectively, and ca,σ,i is the annihilation operator for electron at site i with orbital a and spin σ. The nearest-neighbor intra-orbital hopping is given by ta, while t12 is the onsite inter-orbital hopping. Here, εa and U describe the onsite energy potential and Hubbard repulsive interaction, respectively. We have the particle-number operator ni = ∑a=1,2na,i and na,i = ∑σ=↑,↓na,σ,i with \({n}_{a,\sigma ,i}\equiv {c}_{a,\sigma ,i}^{\dagger }{c}_{a,\sigma ,i}\). The system is at quarter-filling.

The lattice distortion can be modeled through the classical potential energy53

which is obtained from the Landau functional for improper ferroelectrics expanded up to the sixth order in the lattice displacements to accurately recover the first-order nature of the transition. Here, L is the number of lattice sites. The first term and the last term are fully rotationally symmetric in the X1-X2 plane. On the other hand, the term proportional to β1 favors a lattice distortion only along one of these two directions, whereas the term proportional to β2 favors a distortion with ∣X1∣ = ∣X2∣. In the case of VO2, both the displacements X1 and X2 are nonzero (i.e., there are both dimerization and tilt in the displacements), hence we should have β2 > β1.

Finally, for the electron–lattice coupling, we have

The first term describes the dimerization induced by the displacement X1 along the cR axis and is controlled by the coupling constant g, while the second term with strength δ represents the crystal field splitting generated by the tilting displacement X2. The coupling to X1 is linear at leading order, whereas the coupling to X2 is quadratic since the opposite variations of the hybridization between the \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbital and the closer/further oxygen ligands at linear order in X2 cancel each other, but their sum is nonzero at second order53. Note that the total Hamiltonian is invariant under the transformations X1,2 → − X1,2 and possesses a Z2 × Z2 symmetry.

The simplified quasi-one-dimensional model (1) allows us to study both the equilibrium properties and light-induced nonequilibrium quantum dynamics of VO2 within the well-established tensor network framework. We emphasize that, with this model, our goal is to qualitatively reproduce the physics of VO2, especially the light-induced nonequilibrium phase transitions, without any ambition for quantitative agreement. For this, like ref. 53, we assume that the bands for a1g and \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbitals have the same bandwidth and center of gravity (i.e., ε1 = ε2 = 0) to reduce the number of Hamiltonian parameters. We set the half-bandwidth to 1 eV, i.e., t1 = t2 = 0.5 eV, and the inter-orbital hopping coefficient as t12 = 0.1 eV, which is small compared with the intra-orbital hopping and allows for the redistribution of orbital populations during the light-induced quantum dynamics. For the Hubbard interaction, we choose U = 0.6 eV to generate a zero-temperature energy landscape that is similar to the one shown in ref. 53 with two local minima and the global minimum at finite X. A too large or too small Hubbard interaction will lead to an energy landscape with either only one local minimum or the wrong global minimum. Compared to ref. 53, our Hubbard interaction is smaller due to the quasi-one-dimensional nature of our model with a correspondingly different density of states. However, we again note that our model treats the electron correlations exactly, which is essential for a robust description of the light-induced dynamics. For the lattice potential parameters, we use the same values as proposed in ref. 53, i.e., α = 0.155 eV, β1 = 1.75 × 10−3 eV, β2 = 2β1, and γ = 6.722 × 10−4 eV. Finally, we choose the electron–lattice coupling strength as g = 0.528 eV and δ = 0.2 eV, such that the transition temperature from the M1 phase to the R phase is close to the experimental value. These values are close to the electron–lattice couplings used in ref. 53.

We note that our definition of lattice potential parameters and electron–lattice couplings in units of energy implies that the displacements X1 and X2 are expressed in a dimensionless way, as only the product of displacement and the (unknown) couplings affect the overall energy. Fortunately, the underlying length scale (on the order of 0.1 Å) is not relevant for distinguishing the R phase (X1 = X2 = 0) and the M1 phase (X1 ≠ 0 and X2 ≠ 0).

Ground-state phases

Having introduced the simplified quasi-one-dimensional model, we now present the corresponding equilibrium properties both at zero and finite temperature. These results show that our model captures the essential physics of VO2, justifying the later dynamics studies. We first determine the ground state phases. We solve the model Hamiltonian (1) using tensor network methods within the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. To determine the ground state phases, we calculate the zero-temperature adiabatic potential Φeff(X) for each fixed displacement X, which is renormalized by the electronic energy

Here the electronic energy (i.e., the last two terms) is obtained by employing the infinite density matrix renormalization group (iDMRG) method59,60; see Methods. The quarter-filling is ensured in the numerical simulation by introducing good quantum numbers. Due to the Z2 × Z2 symmetry of the system under transformations X1,2 → − X1,2 (domain inversion), we focus on the region with X1, X2 > 0.

The results are shown in Fig. 2. There are two minima in the zero-temperature energy landscape (due to the Z2 × Z2 symmetry, the local minima at finite X are actually fourfold degenerate). One local minimum is located at the origin point X1 = X2 = 0 and corresponds to the undistorted R phase. On the other hand, the global minimum is located at X1 ≈ 2.05 and X2 ≈ 1.65, describing the distorted M1 insulating ground state at zero temperature. From this, we conclude that the simplified quasi-one-dimensional model (1) captures the essential physics of VO2 and provides a good playground to qualitatively study its properties.

Due to the Z2 × Z2 symmetry of the system, we only show the results for the region with X1, X2 > 0, where the internal energy has two minima, one located at X1 = X2 = 0 corresponding to the undistorted R phase, and another located at X1 ≈ 2.05 and X2 ≈ 1.65 corresponding to the distorted M1 phase. Here the maximal bond dimension 1000 is used to produce this energy landscape, for which the converged internal energy density of the insulating M1 phase (global minimum) is ≈ −0.71941 eV, and we have Φeff(0, 0) ≈− 0.71804 eV for the R phase (this value can be further improved by increasing the maximal bond dimension due to its metallic nature, but the local minimum property of the point X = 0 is unaffected; see the Supplementary Information).

Phase transition at finite temperature

The key defining feature of VO2 is, of course, the transition from the low-temperature M1 phase to the high-temperature R phase, but reproducing this thermal transition theoretically is nontrivial. Here we use the matrix product operator (MPO) time evolution technique61,62 in combination with the purification method63 to show that the simplified quasi-one-dimensional Hamiltonian (1) can reproduce this finite-temperature phase transition and estimate the corresponding transition temperature. We note that in this method, the finite-temperature state is obtained from the infinite-temperature state by imaginary time evolution; see Methods. To ensure the quarter-filling, we use good quantum numbers in the numerical simulation and start from a canonical infinite-temperature ensemble with fixed particle-number density and finite system size64. While lattice entropy has been suggested to be important to the phase transition in VO2 previously37,58, for simplicity here we ignore this factor and focus on the electronic contribution when studying the thermal phase transition. Including lattice entropy would, however, serve to further reduce the transition temperature.

We calculate the adiabatic potential Φeff at temperature T and study the temperature evolution of the free energies

for the two local minima we obtained at zero temperature53. Since the imaginary time evolution starts from the infinite temperature at which the entropies S∞ are the same for both R and M1 phases, the entropy at temperature T can be calculated through

Here the infinite-temperature entropy S∞ can be further eliminated by considering the difference between the free energies of R and M1 phases:

with ΔΦeff(T) ≡ Φeff(XR, T) − Φeff(XM1, T) and \(\Delta S(T)=-\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{T}^{\infty }{\rm{d}}{T}^{{\prime} }\,(1/{T}^{{\prime} })\partial \Delta {\Phi }_{{\rm{eff}}}({T}^{{\prime} })/\partial {T}^{{\prime} }\). This quantity is what we are actually interested in.

The finite-temperature results are presented in Fig. 3, where the imaginary time evolution is carried out with time step δβ = 0.05 eV−1 (β = 1/kBT is the inverse temperature). Since the calculation for the entropy difference ΔS requires us to perform the differential and integration with respect to the temperature, we interpolate the adiabatic potential ΔΦeff(β) using polynomial functions. The obtained free energy difference from MPO time evolution with maximal bond dimension D = 2000 for the system size L = 20 is shown in Fig. 3a. The negative ΔF at high temperature indicates that the system is in the R phase, and there is a transition from the low-temperature M1 phase (ΔF > 0), with the transition temperature Tc ≈ 1131 K being identified by ΔF = 0 for the used system size and maximal bond dimension.

a Free energy difference ΔF between the R and M1 phases as a function of the inverse temperature β for system size L = 20. The corresponding transition temperature Tc = 1/kBβc ≈ 1131 K is obtained by solving the equation ΔF(β) = 0. The insert shows the bare adiabatic potential difference ΔΦeff, where the dots are obtained from the numerical simulation, while the line is the interpolation via polynomial function. We set the maximal bond dimension as D = 2000 in this plot. b Finite size extrapolation for transition temperature Tc using the function Tc(L) = a + b/Lc with a ≈1055 K, b ≈57292 K, and c ≈2.2170. The maximal bond dimension is fixed as D = 2000. c Extrapolation of transition temperature Tc in the maximal bond dimension D for system size L = 20 using the function Tc(D) = a + b/Dc with a ≈810 K, b ≈ 122306 K, and c ≈0.7819. Here the imaginary time step in the numerical simulation is set as δβ = 0.05 eV−1.

We perform an extrapolation in L and D to estimate the transition temperature Tc for large system size and maximal bond dimension; see Fig. 3b, c. In the extrapolation of system size with fixed maximal bond dimension D = 2000, the change in transition temperature, as in the usual cases, decreases as we increase the system size, justifying the extrapolation function, from which the Tc for L → ∞ is only lowered by ≈76 K compared with the value for L = 20. On the other hand, the maximal bond dimension D has a more notable influence on Tc, as the changes of ΔF are very slow in low temperatures, i.e., the temperature is more sensitive to ΔF in this region. For the system size L = 20, the transition temperature for D → ∞ is lowered by ≈321 K compared with the value for D = 2000. Combining these two effects, we obtain an estimation for the transition temperature for our used parameters as Tc ≈ 734 K.

We would like to mention that the above estimated transition temperature actually should be higher than the exact value. On the one hand, the MPO imaginary time evolution method may lose its accuracy in the long time limit (i.e., the low-temperature region), which makes it hard to obtain the exact transition temperature; see Methods. Choosing a smaller time step or larger bond dimension would increase the accuracy, but it is much more computationally costly. On the other hand, including the lattice entropy would also substantially reduce the transition temperature. Hence, the above estimated value gives only a rough estimation of the transition temperature, but shows that the overall energetic trends are captured correctly. We note that the main object of this work is to investigate the physics of light-induced phase transitions in VO2. Although the estimated value for Tc is around a factor of two higher when compared with the experimental value, our simplified model (1) still qualitatively captures the phase transition from the low-temperature M1 phase to the high-temperature R phase, hence providing the foundation for studying the light-induced phase transitions. Moreover, as we show in Supplementary Information, the light-induced quantum dynamics for our parameters, which lead to an estimation of Tc ≈ 734 K, are almost the same as compared to a system with Tc = 0. Hence, in this parameter range, the deviation in transition temperature from the experimentally realized value will not affect the light-induced phase transitions qualitatively.

Light-induced quantum dynamics

Having shown that our quasi-one-dimensional model can qualitatively capture the essential physics of VO2, especially the finite-temperature phase transition, we next study the light-induced phase transition from the initial M1 insulating phase to the long-time R metallic phase. We start from the equilibrium M1 phase at zero temperature as numerous experiments have shown a negligible change in the photoinduced dynamics upon changing the initial temperature45,55, while static measurements also show minimal changes in the overall structure when cooled65.

We excite the system using a pump pulse with the electric field

which is centered at time t0,pump and has central frequency ωpump and temporal width σpump. The pump pulse couples to the electronic degrees of freedom through the Peierls substitution \({t}_{\alpha }\to {t}_{\alpha }{e}^{{\rm{i}}{A}_{{\rm{pump}}}(t)}\) with the phase

where d is the lattice constant, \({\rm{erf}}(z)=(2/\sqrt{\pi })\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{z}{\rm{d}}t\,{e}^{-{t}^{2}}\) is the error function, and we have \({t}_{\pm }=[{\rm{i}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{pump}}}^{2}{\omega }_{{\rm{pump}}}\pm (t-{t}_{0,{\rm{pump}}})]/\sqrt{2}{\sigma }_{{\rm{pump}}}\). With the pump pulse, the displacement X also becomes time-dependent due to the electron–lattice coupling.

We use the hybrid quantum-classical tensor-network method to simulate the dynamics of the system; see Methods. In this method, within each time step δt, the quantum electronic degrees of freedom \(| \psi \left.\right\rangle\) are evolved according to the many-body Schrödinger equation using the infinite time-evolving block decimation (iTEBD) method66,67, while the lattice degrees of freedom X are treated classically using the Ehrenfest theorem. For the lattice evolution, we also introduced a phenomenological damping term proportional to the velocity \(\dot{{\bf{X}}}\) to model the lattice disordering observed in recent X-ray diffraction experiments37,54,55. The damping strength is controlled by the coefficient ξ; see Methods. We note that treating the quantum electronic and classical lattice degrees of freedom separately is similar to the real-time TD-DFT68 used recently to model VO251,52. However, in our hybrid quantum-classical tensor-network method, the electron–electron correlations are handled in a true many-body way, which enables capturing the full interaction effects.

Photoinduced structural phase transition

We first study the structural phase transition of VO2 induced by the pump pulse. We consider a pulse with wavelength 800 nm, width 6 fs, and centered at 20 fs. The electric field strength ranges from 0.5 to 1 V/Å. Note that for VO2 with lattice constant d ≈ 3 Å, the electric field of strength E0,pump = 1 V/Å corresponds to a Peierls substitution phase of strength A0,pump = 1.88. In the following, we will use A0,pump to represent the pulse strength.

Figure 4 shows the time evolution of lattice displacements X1 and X2 with damping coefficient ξ = 1.316 eV ⋅ fs, chosen as a minimal value which removes the unphysical structural revivals beyond 100 fs delay, corresponding to the resolution of the best diffraction measurements55. The responses reflect well the mean ultrafast lattice dynamics observed in VO2 in both ultrafast X-ray diffraction37,54,55 and ultrafast electron diffraction69. Especially, for the considered pulse strength the displacements X1 and X2 quickly transform to zero within the total simulation time ~80 fs, indicating the ultrafast photoinduced SPT from the distorted M1 phase to the undistorted R phase.

However, there are also several interesting features in the structural dynamics at short timescales not previously observed. The first is the overall timescale of the structural transition appears unrelated to the corresponding phonon modes when the system is excited below the transition threshold (see the Supplementary Information). In particular, X1 transforms at around the same time as the phonon mode would suggest (half period ≈21 fs, crossing expected at ≈41 fs), but X2 transforms considerably faster (half period ≈44 fs, crossing expected at ≈64 fs). We note that the introduced phenomenological damping, applied in both cases, is necessary to accurately describe the dynamics of the transition as observed with X-ray diffraction37 but is not observed for phonons in the M1 phase27, and so we artificially slow the phonon mode here. Thus the transition likely outpaces the phonon even more. This suggests that, in contrast to assumptions in numerous studies44,47,48, the structural transition timescale is not limited by the normal phonon mode frequencies but, in fact, samples a significant portion of the nonlinear lattice potential. This nonlinearity means the common approach of using the timescale of the transition alone to assign a structural or electronic origin by comparison to known Raman modes could be highly misleading, not only for VO2 but for light-induced phase transitions generally.

The second notable effect is that X1 relaxes faster than X2, i.e., the dimerization also relaxes prior to the tilt. This is broadly in-line with the two-step structural phase transition mechanism proposed by Baum et al.28, but while the pico-to-nanosecond timescale proposed there is at odds with later diffraction measuremens37,54,69, here the change occurs many orders of magnitude faster and is consistent with these recent diffraction measurements. This separation is also consistent with recent TD-DFT calculations51.

Another remarkable feature of the lattice dynamics is that the displacements X1 and X2 undergo a transient revival with opposite signs for significant excitation levels. These findings can provide an explanation for the complex dynamics observed in ref. 49, one of the only studies with a resolution sufficient to resolve dynamics significantly below 100 fs. In this work, the a1g band was found to exhibit a double-peak oscillatory structure at tens of femtoseconds in the time evolution. It was pointed out that the oscillation cannot be explained by the coherent electronic effect since the scattering time for electrons is much faster than this behavior, leaving these coherent lattice effects as the leading explanation, in good agreement with our results here. We note that for larger damping coefficient ξ, a stronger light pulse is required to observe the transient revival behavior of lattice displacements, but overall the dependence on pulse energy is quite weak, in contrast to recent TD-DFT calculation51,52 but in agreement with recent X-ray diffraction measurements54.

Photoinduced electronic insulator-metal transition

We now turn our attention to the IMT. Since it is hard to track the time-dependent occupations of single-particle states and the corresponding closure of the gap in a many-body method like iTEBD, here we instead study this phenomenon using the time-dependent optical conductivity and look for the collapse of the optical band gap. To calculate the time-dependent optical conductivity, in addition to the pump pulse, we further apply a weak probe pulse \({A}_{{\rm{probe}}}(t)={A}_{0,{\rm{probe}}}\exp [-{(t-{t}_{0,{\rm{probe}}})}^{2}/2{\sigma }_{{\rm{probe}}}^{2}]\cos [{\omega }_{{\rm{probe}}}(t-{t}_{0,{\rm{probe}}})]\) centered at time t0,probe = t* and track the variation of the current due to the presence of probe pulse, i.e., 〈Jprobe(t)〉, using the pump-probe based method proposed in ref. 70, which identifies the response of the system with respect to the later probe pulse; see Methods. Then the time-dependent optical conductivity at time t* is given by

where Jprobe(ω) and Aprobe(ω) are the Fourier transformations of 〈Jprobe(t)〉 and Aprobe(t), respectively. Numerically, a damping factor \(\exp (-\eta t)\) is introduced in the Fourier transformations, which effectively eliminates the long-time data and is also necessary to distinguish the Drude component of the spectral weight. With this term, a finite-time simulation of the probe current within a sufficient time window is enough to observe the behavior of optical conductivity; see the Supplementary Information for the justification of our calculation of optical conductivity. We also note that if there is no pump pulse, Eq. (11) gives the optical conductivity at equilibrium.

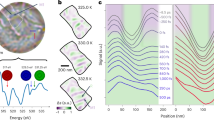

In Fig. 5, we show the optical conductivity with and without the pump. For the initial M1 phase at equilibrium, we apply a weak and narrow probe pulse of frequency ℏωprobe = 10 eV centered at t0,probe = 0.658 fs with width σprobe = 0.0658 fs and amplitude A0,probe = 0.01 (i.e., a near-delta function), which does not change the properties of the system qualitatively. Due to the finite time step in the iTEBD numerical simulation, there is a small deviation from zero for the current, even in the absence of external fields. For this, we also subtract this fictitious current from 〈Jprobe(t)〉. The resulting current density induced by the probe pulse is shown in Fig. 5a, giving an optical conductivity with no amplitude at low frequencies and a first peak located at ℏω ≈ 1.1 eV, which identifies the insulating nature of the initial M1 phase; see Fig. 5c.

a, b The current density 〈jprobe(t)〉 due to the presence of probe pulse with frequency ℏωprobe = 10 eV, width σprobe = 0.658 fs, and amplitude A0,probe = 0.01. The center time t0,probe of the probe pulse is 0.0658 fs for (a) and 26 fs (blue) or 39 fs (orange) for (b). For the cases with pump, we only plot the current up to time ~20 fs after the probe pulse centered at t*. For longer times, the numerical errors are not ignorable (see Supplementary Information). c, d The real part of the optical conductivity obtained from 〈jprobe(t)〉 shown in (a) and (b), respectively. For the pump pulse, the amplitude is chosen as A0,pump = 1.88, and other parameters are the same as in Fig. 4. The iTEBD simulation is performed using a time step δt = 3.29 × 10−3 fs and maximal bond dimension D = 1000, and we set η = 0.15 fs−1 in the numerical Fourier transformation.

On the other hand, the optical conductivity exhibits a sharply different behavior following excitation by the pump pulse. Fig. 5b shows the current density 〈jprobe(t)〉 for the probe pulses centered at t0,probe = 26 and 39 fs, times at which the lattice of VO2 is still distinct from the R structure (cf. Fig. 4). Other parameters of the probe pulses remain the same as in the pump-free case. The collapse of the optical band gap [Fig. 5d] shows the metallicity of the system by at least t = 26 fs. This photoinduced electronic IMT is much faster than the SPT and can be considered as a quasi-instantaneous transformation, which is consistent with both 60-fs resolution time-and-angle resolved photoemission experiments46 and with more recent ultrafast reflectivity/absorption studies, which show electronic transitions as fast as 10 fs47,48,49. The decoupling nature of SPT and IMT in the light-induced nonequilibrium states also highlights the important role of electron–electron correlations in driving the electronic transitions, which are indeed Mott-like instead of driven by the Peierls instability. This effect is equally treated in the simplified quasi-one-dimensional model (1) with the electron–lattice coupling and handled in a many-body way.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have performed a tensor network study of the light-induced phase transitions in VO2. A simplified quasi-one-dimensional model was proposed to capture the corresponding essential physics, with all the important ingredients such as multiorbital character, electron–lattice coupling, and electron–electron correlations being included. We have shown that this model can qualitatively describe the equilibrium properties of VO2, such as the zero-temperature ground state phase diagram and finite-temperature phase transitions, which can provide insights into the studies of vanadium dioxide.

Under the action of an ultrafast light pulse, we found a number of interesting structural and electronic behaviors. In agreement with a range of recent studies, we found that the electronic transition precedes the structural transitions47,48,49, supporting a Mott-like origin for the transition. However, we also found that the structure transforms faster than the harmonic phonon modes of the M1 phase, suggesting the nonlinearity of lattice potential is key in the SPT, and the simple timescale arguments used to assign a structural or electronic nature to the transition from the previous studies26,47,48 do not necessarily apply for the more extreme case of light-induced phase transitions. This may have ramifications for light-induced phase transitions far beyond VO2. Additionally, we found separate timescales for the evolution of dimerization and tilt distortions in the lattice dynamics, in broad agreement with older models of VO228 but here several orders of magnitude faster, in agreement with the timescales observed in more recent X-ray diffraction studies54,55. Finally, we also observed a loss and subsequent restoration behavior of the structural displacements, which can provide an explanation for the complex dynamics recently found in the highest time-resolution studies to date49. Overall our results are fully consistent with the most recent and highest time-resolution studies of both the electronic27,46,47,48,49 and structural37,54,55,69 components of the transition, despite only explicitly treating the mean displacements of the dimers and including ultrafast disordering37,55 through a phenomenological damping term. Future work will include systematic studies to find whether or not the IMT can be induced without also introducing the associated SPT33, which would be a clear marker of the Mott behavior, and examining to what degree the phase transition can be controlled using optical pulses54. Our work sheds important light on the nature of the light-induced phase transition in VO2 at the shortest timescales, and challenges assumptions about signatures of decoupled electronic and structural phase transitions more generally.

Beyond VO2, our model and the tensor-network approach to solve the many-body electronic wavefunctions coupled to classic nuclei can also be extended to study light-induced phenomena in other quantum materials. Naturally, it is applicable to other dioxide compounds (e.g., CrO2, TiO2, NbO2, and so on), which exhibit interesting light-induced behaviors71 but also to cases like one-dimensional charge-density wave systems72 or cuprate ladder systems73. It could thus be used to shed light, for instance, on the mechanism behind the structural coherent control recently observed in one-dimensional charge-density wave systems where two-independent distortions are believed to be important74. The main constraints of our approach are that the correlated electron system is treated as one-dimensional and the coupling to lattice locally, but additional bands and other lattice potentials can easily be included. This means the model is directly applicable to a wide range of systems like mixed valency planar transition-metal compounds and charge transfer salts75. We especially note that, for some organic superconductors, our ability to treat nonlinear phononics could be highly valuable in studying effects like light-induced superconductivity76. These possibilities demonstrate the generality of our approach and form promising lines for study in the future.

Methods

DMRG simulation of the zero-temperature adiabatic potential energy

We employ the iDMRG algorithm proposed in ref. 60 to calculate the zero-temperature adiabatic potential energy (5), which initializes the DMRG environments and performs the updates using the finite-size DMRG algorithm for a unit cell of L sites at the beginning. Then the system size is increased between the DMRG sweeps by inserting a unit cell into each of the environments. The translation invariance is recovered when the iDMRG iteration of sweeps and growing environments converges to a fixed point, at which the environments describe infinite half-chains.

In our numerical simulation of the model (1), we consider a unit cell of four sites, and each site contains one a1g orbital electron and one \({e}_{g}^{\pi }\) orbital electron. The particle-number and magnetization U(1) symmetries are also considered to enhance the performance of iDMRG numerical simulations. We use the product state \(| {\uparrow }_{{a}_{1g}}{\downarrow }_{{e}_{g}^{\pi }}{\downarrow }_{{a}_{1g}}{\uparrow }_{{e}_{g}^{\pi }}\left.\right\rangle\) as the initial trial wave function for the unit cell in the iDMRG simulation and gradually increase the bond dimension during sweeps. The maximal bond dimension used to produce Fig. 2 is 1000, for which the energies at most displacements X are converged very well except for those near X = 0 due to the metallic nature of the phase. However, as we show in the Supplementary Information, further increasing the maximal bond dimension will not change the result that the zero-temperature energy landscape has a global minimum at X1 ≈ 2.05, X2 ≈ 1.65 and a local minimum at X = 0. Hence the results obtained in this work are unaffected.

Finite-temperature simulation

To study the finite-temperature phase transition of VO2, we need to calculate the equilibrium state of the system in the (here, unnormalized) canonical ensemble

with HN being the projection of Hamiltonian onto the Hilbert subspace \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{N}\equiv \{| {\boldsymbol{n}}\left.\right\rangle { = \bigotimes }_{i}| {n}_{i}\left.\right\rangle | {\sum }_{i}{n}_{i}=N\}\) with total particle number N. For the quarter-filling considered in this work, we have N being the system size L. We consider a purification of the density matrix ρβ,N for numerical facilitation63

which is defined in the doubled Hilbert space \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{N}\otimes {{\mathcal{H}}}_{N,{\rm{aux}}}\) and satisfies \({{\rm{Tr}}}_{{\rm{aux}}}| {\rho }_{\beta /2,N}\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.{\rho }_{\beta /2,N}| ={\rho }_{\beta ,N}\). Here the auxiliary Hilbert space \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{N,{\rm{aux}}}\) is isomorphic to the physical Hilbert space \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{N}\). Starting from the purification \(| {\rho }_{0,N}\left.\right\rangle\) of the infinite-temperature ensemble, we can employ the imaginary time evolution to obtain the purification for the finite-temperature state ρβ,N:

Then the thermal expectation value of an observable O is given by

Since it is impossible to calculate the exponential e−βH/2 directly, we need to divide the total imaginary time evolution into a lot of small time steps δβ and calculate the exponential e−δβH approximately in each time step. In this work, we use the MPO WII method proposed in refs. 61,62 to perform this task. As the imaginary time evolution does not change the particle number, we can ensure the quarter-filling of the system by considering the infinite-temperature state in the canonical ensemble

Matrix product-state (MPS) methods to construct this canonical infinite-temperature ensemble were proposed in ref. 64. Compared to the grand-canonical infinite-temperature ensemble that is simply described by the identity matrix, the resulting MPS representation of \(| {\rho }_{0,N}\left.\right\rangle\) is highly nontrivial and the corresponding maximum bond dimension increases with the system size, which limits the system size we can simulate efficiently. However, with this state, we can simply focus on the numerical time evolution and does not need to tune the chemical potential to guarantee the desired particle filling. Moreover, the phase transition between M1 and R phases then can be directly identified by comparing the Helmhotz free energy F = Φeff − TS.

The errors in our finite-temperature simulation come from the finite imaginary time step, maximal bond dimension, and system size. For the finite time step δβ, the error per site of the MPO WII method in each time step is independent of the system size and is given by \({\mathcal{O}}(\delta {\beta }^{2})\) for the evolved purification state61,62. Therefore, the free energy F has an error \({\mathcal{O}}(\delta {\beta }^{4})\) in each time step, and the corresponding accumulated error for the total evolved time β/2 is given by ~βδβ3, which may have a notable influence in the low-temperature region and affect the transition temperature. On the other hand, Fig. 3b, c give us insights into the errors from finite maximal bond dimension and system size, which can be estimated via the extrapolation. Compared to the system size, the maximal bond dimension is more relevant for the transition temperature. Therefore, to improve the accuracy of the finite-temperature simulation, we need to consider smaller time steps and larger bond dimensions, which increases the computational challenges.

As the transition temperature of VO2 is not so high, the minimally entangled typical thermal state (METTS)77,78 could be a possible alternative method for improving the finite-temperature calculation, which, however, requires many samples to converge to a precise result and needs remarkable computational resources. Including the ignored lattice entropy in this work by considering the phonon-phonon interactions could also improve the finite-temperature results, which is more complicated and is beyond the goal of this work for studying light-induced phase transitions.

Hybrid quantum-classical tensor-network method

To simulate the light-induced quantum dynamics, we decompose the time evolution of the system into two parts, i.e., the quantum electronic and classical lattice degrees of freedom. For the evolution of electronic state \(| \psi \left.\right\rangle\), we use the Born–Oppenheimer approximation within each time step δt, i.e., the lattice distortions are approximated as fixed, while the electronic degrees of freedom are treated dynamically. The use of the Born–Oppenheimer approximation is justified via the extremely fast electron–electron scattering in VO249,56, which allows the electron distribution to equilibrate far faster than the lattice motion. Then the electronic equation of motion is given by the Schrödinger equation and can be written as

which can be simulated numerically by the iTEBD method. We note that we used the natural units in the numerical simulation, for which some of the simulation parameters, like the time step δt, become irrational numbers in the international system of units.

On the other hand, for the lattice dynamics, we use the classical approximation and invoke the Ehrenfest theorem for the lattice degrees of freedom

where M is the effective mass of ions, which is set as 10.8241 eV ⋅ fs2, and ξ is a damping coefficient tuned to model the lattice disordering observed in recent X-ray diffraction experiments37,54,55. The forces Fi are obtained through the Hellmann–Feynman theorem and explicitly read

and

see the Supplementary Information for details. With the equations of motion (17) and (18), both the light-induced structural and electronic dynamics of VO2 can be simulated. The convergence and robustness of our results is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Calculation of optical conductivity

Given the knowledge of the time-evolved electronic wave function \(| \psi (t)\left.\right\rangle\) under the action of an external field A(t), the temporal evolution of the current, defined as \(\langle J(t)\rangle =\left\langle \right.\psi (t)| J(t)| \psi (t)\left.\right\rangle\) with

can be readily obtained, and we can extract the optical conductivity from this current.

For the systems at equilibrium, we can set the external field A(t) to be the weak probe pulse Aprobe(t), and the corresponding current is denoted as 〈Jprobe(t)〉. Since the wave function \(| \psi (t)\left.\right\rangle\) describes the influence of Aprobe on the ground state, the optical conductivity at equilibrium can be calculated through this current using Eq. (11).

This scheme can be extended to calculate the optical conductivity for a nonequilibrium system driven by the pump pulse. To this end, we employ the pump-probe-based method proposed in ref. 70, where the temporal evolution of the system is traced twice in order to identify the response of the system with respect to the later probe pulse. The procedure is as follows. First, the time-evolution process induced by the pump pulse Apump(t) in the absence of probe pulse is evaluated, which describes the nonequilibrium development of the system, and we have the current 〈Jpump(t)〉. Second, in addition to the pump pulse, we also introduce the weak probe pulse Aprobe(t) centered at time t*, which leads to the current 〈Jtotal(t)〉. The subtraction of 〈Jpump(t)〉 from 〈Jtotal(t)〉 produces the variation of the current due to the presence of probe pulse, i.e., 〈Jprobe(t)〉, with which the time-dependent optical conductivity at time t* can be calculated through Eq. (11).

Data availability

The data supporting the results in this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code supporting the results in this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mott, N. F. The basis of the electron theory of metals, with special reference to the transition metals. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A 62, 416 (1949).

Morin, F. J. Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the Neel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 34 (1959).

Liu, K., Lee, S., Yang, S., Delaire, O. & Wu, J. Recent progresses on physics and applications of vanadium dioxide. Mater. Today 21, 875 (2018).

Shao, Z., Cao, X., Luo, H. & Jin, P. Recent progress in the phase-transition mechanism and modulation of vanadium dioxide materials. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 581 (2018).

Andersson, G., Paju, J., Lang, W. & Berndt, W. Studies on vanadium oxides. I. Phase analysis. Acta Chem. Scand. 8, 1599 (1954).

Andersson, G., Parck, C., Ulfvarson, U., Stenhagen, E. & Thorell, B. Studies on vanadium oxides. II. The crystal structure of vanadium dioxide. Acta Chem. Scand. 10, 623 (1956).

Goodenough, J. B. Direct cation–cation interactions in several oxides. Phys. Rev. 117, 1442 (1960).

Biermann, S., Poteryaev, A., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Georges, A. Dynamical singlets and correlation-assisted Peierls transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 026404 (2005).

Eyert, V. VO2: a novel view from band theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 016401 (2011).

Brito, W. H., Aguiar, M. C. O., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Metal-insulator transition in VO2: a DFT + DMFT perspective. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 056402 (2016).

Nájera, O., Civelli, M., Dobrosavljević, V. & Rozenberg, M. J. Resolving the VO2 controversy: Mott mechanism dominates the insulator-to-metal transition. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035113 (2017).

Nájera, O., Civelli, M., Dobrosavljević, V. & Rozenberg, M. J. Multiple crossovers and coherent states in a Mott-Peierls insulator. Phys. Rev. B 97, 045108 (2018).

Kim, S., Kim, K., Kang, C.-J. & Min, B. I. Correlation-assisted phonon softening and the orbital-selective Peierls transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195106 (2013).

Lahneman, D. J. et al. Insulator-to-metal transition in ultrathin rutile VO2/TiO2(001). npj Quantum Mater. 7, 72 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Orbital-selective Mott and Peierls transition in HxVO2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 95 (2022).

Goodenough, J. B. The two components of the crystallographic transition in VO2. J. Solid State Chem. 3, 490 (1971).

Zylbersztejn, A. & Mott, N. F. Metal-insulator transition in vanadium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 11, 4383 (1975).

Nasu, K. Photoinduced Phase Transitions (World Scientific, 2004).

Fausti, D. et al. Light-induced superconductivity in a stripe-ordered cuprate. Science 331, 189 (2011).

Giannetti, C. et al. Ultrafast optical spectroscopy of strongly correlated materials and high-temperature superconductors: a non-equilibrium approach. Adv. Phys. 65, 58 (2016).

de la Torre, A. et al. Colloquium: nonthermal pathways to ultrafast control in quantum materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 041002 (2021).

Koshihara, S. et al. Challenges for developing photo-induced phase transition (PIPT) systems: from classical (incoherent) to quantum (coherent) control of PIPT dynamics. Phys. Rep. 942, 1 (2022).

Rajpurohit, S., Simoni, J. & Tan, L. Z. Photo-induced phase-transitions in complex solids. Nanoscale Adv. 4, 4997 (2022).

Tang, R., Boi, F. & Cheng, Y.-H. Light-induced topological phase transition via nonlinear phononics in superconductor CsV3Sb5. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 78 (2023).

Ejima, S., Lange, F. & Fehske, H. Entanglement analysis of photoinduced η-pairing states. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 232, 3479 (2023).

Cavalleri, A., Dekorsy, T., Chong, H. H. W., Kieffer, J. C. & Schoenlein, R. W. Evidence for a structurally-driven insulator-to-metal transition in VO2: a view from the ultrafast timescale. Phys. Rev. B 70, 161102 (2004).

Wall, S. et al. Ultrafast changes in lattice symmetry probed by coherent phonons. Nat. Commun. 3, 721 (2012).

Baum, P., Yang, D.-S. & Zewail, A. H. 4D visualization of transitional structures in phase transformations by electron diffraction. Science 318, 788 (2007).

Kübler, C. et al. Coherent structural dynamics and electronic correlations during an ultrafast insulator-to-metal phase transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 116401 (2007).

Liu, M. et al. Terahertz-field-induced insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide metamaterial. Nature 487, 345 (2012).

Cocker, T. L. et al. Phase diagram of the ultrafast photoinduced insulator-metal transition in vanadium dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155120 (2012).

Tao, Z. et al. Decoupling of structural and electronic phase transitions in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166406 (2012).

Morrison, V. R. et al. A photoinduced metal-like phase of monoclinic VO2 revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Science 346, 445 (2014).

Wegkamp, D. & Stähler, J. Ultrafast dynamics during the photoinduced phase transition in VO2. Prog. Surf. Sci. 90, 464 (2015).

O’Callahan, B. T. et al. Inhomogeneity of the ultrafast insulator-to-metal transition dynamics of VO2. Nat. Commun. 6, 6849 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Imaging metal-like monoclinic phase stabilized by surface coordination effect in vanadium dioxide nanobeam. Nat. Commun. 8, 15561 (2017).

Wall, S. et al. Ultrafast disordering of vanadium dimers in photoexcited VO2. Science 362, 572 (2018).

Otto, M. R. et al. How optical excitation controls the structure and properties of vanadium dioxide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 450 (2018).

Lee, D. et al. Isostructural metal-insulator transition in VO2. Science 362, 1037 (2018).

Fu, X. et al. Nanoscale-femtosecond dielectric response of Mott insulators captured by two-color near-field ultrafast electron microscopy. Nat. Commun. 11, 5770 (2020).

Vidas, L. et al. Does VO2 host a transient monoclinic metallic phase? Phys. Rev. X 10, 031047 (2020).

Sood, A. et al. Universal phase dynamics in VO2 switches revealed by ultrafast operando diffraction. Science 373, 352 (2021).

Johnson, A. S. et al. Ultrafast X-ray imaging of the light-induced phase transition in VO2. Nat. Phys. 19, 215 (2022).

Cavalleri, A. et al. Femtosecond structural dynamics in VO2 during an ultrafast solid-solid phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 237401 (2001).

Pashkin, A. et al. Ultrafast insulator-metal phase transition in VO2 studied by multiterahertz spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 83, 195120 (2011).

Wegkamp, D. et al. Instantaneous band gap collapse in photoexcited monoclinic VO2 due to photocarrier doping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 216401 (2014).

Jager, M. F. et al. Tracking the insulator-to-metal phase transition in VO2 with few-femtosecond extreme UV transient absorption spectroscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9558 (2017).

Bionta, M. R. et al. Probing the phase transition in VO2 using few-cycle 1.8 μm pulses. Phys. Rev. B 97, 125126 (2018).

Brahms, C. et al. Decoupled few-femtosecond phase transitions in vanadium dioxide. Preprint at arXiv:2402.01266 (2024).

Yuan, X., Zhang, W. & Zhang, P. Hole-lattice coupling and photoinduced insulator-metal transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035119 (2013).

Xu, J., Chen, D. & Meng, S. Decoupled ultrafast electronic and structural phase transitions in photoexcited monoclinic VO2. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd2392 (2022).

Liu, H.-W. et al. Unifying the order and disorder dynamics in photoexcited VO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2122534119 (2022).

Grandi, F., Amaricci, A. & Fabrizio, M. Unraveling the Mott-Peierls intrigue in vanadium dioxide. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013298 (2020).

Johnson, A. S. et al. All-optical seeding of a light-induced phase transition with correlated disorder. Nat. Phys. 20, 970 (2024).

de la Pena Munoz, G. A. et al. Ultrafast lattice disordering can be accelerated by electronic collisional forces. Nat. Phys. 19, 1489 (2023).

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Electrodynamics of the vanadium oxides VO2 and V2O3. Phys. Rev. B 77, 115121 (2008).

Gatti, M., Sottile, F. & Reining, L. Electron-hole interactions in correlated electron materials: Optical properties of vanadium dioxide from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195137 (2015).

Budai, J. D. et al. Metallization of vanadium dioxide driven by large phonon entropy. Nature 515, 535 (2014).

White, S. R. Density matrix formulation for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863 (1992).

McCulloch, I. P. Infinite size density matrix renormalization group, revisited. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/0804.2509 (2008).

Zaletel, M. P., Mong, R. S. K., Karrasch, C., Moore, J. E. & Pollmann, F. Time-evolving a matrix product state with long-ranged interactions. Phys. Rev. B 91, 165112 (2015).

Paeckel, S. et al. Time-evolution methods for matrix-product states. Ann. Phys. 411, 167998 (2019).

Verstraete, F., García-Ripoll, J. J. & Cirac, J. I. Matrix product density operators: simulation of finite-temperature and dissipative systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 207204 (2004).

Barthel, T. Matrix product purifications for canonical ensembles and quantum number distributions. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115157 (2016).

Kucharczyk, D. & Niklewski, Z. Accurate X-ray determination of the lattice parameters and the thermal expansion coefficients of VO2 near the transition temperature. J. Appl. Cryst 12, 370 (1979).

Vidal, G. Efficient simulation of one-dimensional quantum many-body systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 040502 (2004).

Vidal, G. Classical simulation of infinite-size quantum lattice systems in one spatial dimension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 070201 (2007).

Lian, C., Guan, M., Hu, S., Zhang, J. & Meng, S. Photoexcitation in solids: first-principles quantum simulations by real-time TDDFT. Adv. Theory Simul. 1, 1800055 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. Transient dynamics of the phase transition in VO2 revealed by mega-electron-volt ultrafast electron diffraction. Nat. Commun. 14, 1265 (2023).

Shao, C., Tohyama, T., Luo, H.-G. & Lu, H. Numerical method to compute optical conductivity based on pump-probe simulations. Phys. Rev. B 93, 195144 (2016).

Nie, Z. et al. Following the nonthermal phase transition in niobium dioxide by time-resolved harmonic spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 243201 (2023).

Demsar, K., Biljaković, J. & Mihailovic, D. Single particle and collective excitations in the one-dimensional charge density wave solid K0.3MoO3 probed in real time by femtosecond spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 800 (1999).

Müller, T. F. A., Anisimov, V., Rice, T. M., Dasgupta, I. & Saha-Dasgupta, T. Electronic structure of ladder cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 57, R12655 (1998).

Horstmann, J. G. et al. Coherent control of a surface structural phase transition. Nature 583, 232 (2020).

Zeller, H. R. in Festkörper Probleme (ed. Queisser, H.) (Pergamon, 1973).

Buzzi, M. et al. Photomolecular high-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031028 (2020).

White, S. R. Minimally entangled typical quantum states at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 190601 (2009).

Stoudenmire, E. M. & White, S. R. Minimally entangled typical thermal state algorithms. New J. Phys. 12, 055026 (2010).

Hauschild, J. & Pollmann, F. Efficient numerical simulations with tensor networks: tensor network Python (TeNPy). SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.5 (2018).

Fishman, M., White, S. R. & Stoudenmire, E. M. The ITensor software library for tensor network calculations. SciPost Phys. Codebases https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysCodeb.4 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The iDMRG and finite-temperature calculation were performed using the TeNPy library79, and the iTEBD was implemented based on the ITensor library80. A.S.J. acknowledges the support of the Ramón y Cajal Program (Grant RYC2021-032392-I) and the Spanish AIE (projects PID2022-137817NA-I00 and EUR2022-134052), while IMDEA Nanociencia acknowledges support from the “Severo Ochoa” Program for Centers of Excellence in R&D (MICIN, CEX2020-001039-S). T.G. acknowledges funding by the Gipuzkoa Provincial Council (QUAN-000021-01), by the Department of Education of the Basque Government through the IKUR strategy, and through the project PIBA_2023_1_0021 (TENINT), by the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) through Proyectos de Generación de Conocimiento PID2022-142308NA-I00 (EXQUSMI), by the BBVA Foundation (Beca Leonardo a Investigadores en Física 2023). The BBVA Foundation is not responsible for the opinions, comments, and contents included in the project and/or the results derived therefrom, which are the total and absolute responsibility of the authors. R.W.C. acknowledges support from the Polish National Science Centre (NCN) under the Maestro Grant No. DEC-2019/34/A/ST2/00081. ICFO group acknowledges support from: ERC AdG NOQIA; MCIN/AEI (PGC2018-0910.13039/501100011033, CEX2019-000910-S/10.13039/501100011033, Plan National FIDEUA PID2019-106901GB-I00, Plan National STAMEENA PID2022-139099NB-I00 project funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR” (PRTR-C17.I1), FPI); QUANTERA MAQS PCI2019-111828-2); QUANTERA DYNAMITE PCI2022-132919 (QuantERA II Program co-funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 program under Grant Agreement No 101017733), Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation of the Spanish Government through the QUANTUM ENIA project call—Quantum Spain project, and by the European Union through the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan—NextGenerationEU within the framework of the Digital Spain 2026 Agenda; Fundació Cellex; Fundació Mir-Puig; Generalitat de Catalunya (European Social Fund FEDER and CERCA program, AGAUR Grant No. 2021 SGR 01452, QuantumCAT\ U16-011424, co-funded by ERDF Operational Program of Catalonia 2014-2020); Barcelona Supercomputing Center MareNostrum (FI-2023-1-0013); EU Quantum Flagship (PASQuanS2.1, 101113690); EU Horizon 2020 FET-OPEN OPTOlogic (Grant No 899794); EU Horizon Europe Program (Grant Agreement 101080086—NeQST), ICFO Internal “QuantumGaudi” project; European Union’s Horizon 2020 program under the Marie-Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 847648; “La Caixa” Junior Leaders fellowships, “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434): CF/BQ/PR23/11980043. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union, European Commission, European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA), or any other granting authority. Neither the European Union nor any granting authority can be held responsible for them. U.B. is also grateful for the financial support of the IBM Quantum Researcher Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z., U.B., and A.S.J. conceived the project. L.Z., U.B., M.R., T.G., R.W.C., M.L., and A.S.J. developed the theoretical model. L.Z. conducted the numerical simulations. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Bhattacharya, U., Recasens, M. et al. Tensor network study of the light-induced phase transitions in vanadium dioxide. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 32 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00751-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00751-w

This article is cited by

-

Decoupled few-femtosecond phase transitions in vanadium dioxide

Nature Communications (2025)