Abstract

Predetermining the as-grown polarization of ferroelectric thin films is essential to integrate their reliable properties into electronic devices. However, studies have so far focused mainly on the control of the polarization state of a single ferroelectric layer. Here we report a strategy for the artificial modulation of pristine polarization in BiFeO3 bilayer films. We have fabricated multilayers of BiFeO3/SrTiO3/BiFeO3 on single-crystalline SrTiO3 (001) substrates. It is found that the out-of-plane polarization components of the BiFeO3 bilayer can be controlled by modifying the surface terminations of SrTiO3 interlayer and SrTiO3 substrate. Using aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy, we directly visualize the head-to-head and tail-to-tail polarization configurations formed by the BiFeO3 bilayers. Polar discontinuity at the ferroelectric/non-ferroelectric interface is the reason for tuning the orientation of electrical polarization. Our work provides an effective route to design fascinating ferroelectric multilayers with well-defined polarization direction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxide thin films with ferroic orders play crucial roles in present-day electrical and magnetic device applications1,2,3,4,5,6. To integrate the thin films with reliable properties into functional devices, it is necessary to achieve films with well-defined ferroic order parameters. In ferroic families, ferroelectric oxide thin films as one of the most important members, show rich physical properties and promising potential applications in high-density electronics, particularly non-volatile memories7,8,9,10. Previous studies have shown that the pristine state of electrical polarization for ferroelectric oxide layers can be manipulated by means of interfacial termination layers11,12,13,14,15, elemental nonstoichiometry16 and growth parameters (substrate temperature and oxygen partial pressure)17. Several groups have reported that the net charge at the ABO3 perovskite ferroelectric-based heterointerfaces can be used to alter electrostatic boundary conditions of ferroelectric oxide thin films, thereby controlling their ferroelectric polarization states11,12. Efe et al.18 and Spaldin et al.19 discussed the influence of interface chemistry on the polarization states of these thin films and summarized the mechanism of interplay between interfacial layer charges and spontaneous polarizations at different interface situations. This offers tremendous opportunities for artificially designing novel oxide heterostructures with greatly enhanced functionalities.

Perovskite ferroelectric oxide multilayer structures, as compared to ferroelectric single layers, host a rich spectrum of emergent physical phenomena such as polar topological textures20,21,22,23,24 and can exhibit excellent energy-storage properties25. As a well-known multiferroic material26,27,28,29, BiFeO3 (BFO) exhibits stable states of collectively ordered electrical dipoles at room temperature and has been widely studied over the past two decades30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Here we are motivated by prior work to explore lattice distortions and polarization states of the BFO bilayers in the epitaxial multilayer of BFO/SrTiO3 (STO)/BFO grown on STO (001) substrate. The surface terminations of the STO interlayer and the STO substrate are modified by purposefully inserting an ultrathin oxide layer into the BFO/STO interfaces. Through the polarization vector maps superimposed on high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images, we observe that the BFO bilayers form the head-to-head and tail-to-tail polarization configurations. In addition, we find that, unlike the tail-to-tail configuration, the BFO in the head-to-head configuration shows locally enhanced c/a ratios and polarization, which is most likely related to the existence of a compound of Bi and O at the top surface of the sample.

Results

Design and synthesis of BiFeO3/SrTiO3/BiFeO3 multilayers

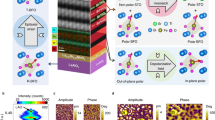

As schematically shown in Fig. 1, two types of BFO/STO/BFO were designed and grown on single-crystalline STO (001) substrates by pulsed laser deposition. The bottom and top BFO layers were grown on different chemical terminations, and the thickness of a single BFO layer was fixed at approximately 15 unit cells. In sample A (Fig. 1a), the (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 (bottom) interface can be created by using TiO2-terminated STO (001) substrates. The (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 (top) interface can be built by depositing a 1.5-unit-cell-thick SrRuO3 (SRO) layer on TiO2-terminated STO interlayer. Since RuO2 is highly volatile, the SRO layer is always self-terminated with the SrO surface38. In sample B (Fig. 1b), the (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 (bottom) interface can be built by depositing 2.5-unit cells-thick SRO layer on TiO2-terminated STO substrates. The (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 (top) interface can be created by utilizing a TiO2 monolayer grown on SrO-terminated STO interlayer. It is worth mentioning that in our designed sample, the A-site or B-site termination is always maintained until an ultrathin SRO layer (from B-site termination to A-site termination) or a TiO2 monolayer (from A-site termination to B-site termination) was employed to modify the initial surface termination of STO. Obtaining the atomic stacking structures at the interfaces by precisely epitaxial synthesis of heterostructures at the atomic scale is essential to test the interface effect on ferroelectric polarization in multilayer systems.

Structural characteristics and ferroelectric properties of the BiFeO3 layers

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image (Supplementary Fig. 1a) of the surface topography for STO (001) substrate and its corresponding 3D view (Supplementary Fig. 1b) show atomically flat terraces, which implies that the TiO2-terminated STO surface was obtained after a buffered HF acid-etch and thermal annealing process39,40. Figure 2a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) θ-2θ scans of both samples A and B at room temperature. Only diffraction peaks from (00l) family planes for the BFO films can be observed, suggesting that all BFO films are epitaxial growth. The Laue fringes around main peaks attest to the structural coherence of the BFO films. It is noteworthy that unlike sample B, there are two sets of main peaks of BFO (denoted by BFO1 and BFO2) in sample A. In addition, from the reciprocal space mapping (RSM) images, we also observe two bright diffraction spots corresponding to the BFO1 and BFO2 in sample A (Fig. 2b) and one bright diffraction spot corresponding to the BFO in sample B (Fig. 2c), respectively. Diffraction spots of all the films and substrates show a nearly identical Qx value, suggesting that the in-plane lattice constant is well matched between the film and STO substrate. Additional phi scans (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) around the (103) planes of the BFO1, BFO2 and BFO, which were measured along the corresponding lattice planes of the STO substrates, feature a four-fold symmetric structure, confirming an in-plane epitaxial relationship with the substrate. The c/a ratios (Supplementary Fig. 3) calculated from XRD scans and RSM results for the BFO1 and BFO2 of sample A and BFO of sample B are 1.032, 1.055, and 1.040, respectively. The emergence of the two sets of diffraction peaks of BFO films in sample A cannot be simply explained by epitaxial strain, since all the BFO films are coherently strained on the substrates. The enhanced c/a ratio might be related to the surface monolayer. In fact, previous studies41,42 have shown that a parasitic bismuth compound (Bi2O3-x) monolayer at the surface can induce the increase of the c/a ratio for an ultrathin BFO film. The formation of such a surface monolayer might arise from the surface reconstruction or relaxation processes43,44. Another reasonable explanation is that the surface monolayer results from an outward migration of the lower BiO plane due to the volatility of Bi. Theoretical calculations41 by Xie et al. demonstrate that the ionic charge of the Bi atoms for the BFO at the Bi2O3-x/BFO interface reduces compared to that of the Bi atoms for the BFO in the film interior. The Bi atoms in Bi2O3-x monolayer show even lower ionic charge. This weakens the attraction between Bi and O atoms and increases their bond length. Consequently, the imbalance between the weaker Bi–O bond near the surface and the stronger bond in the interior BFO film results in the formation of a strong dipole field that counteracts the depolarizing field, thereby enhancing ferroelectric polarization and c-axis lattice parameters. According to our design, the sample A has the BiO-termination surface, which is easier to form the surface monolayer of Bi2O3-x that can result in a significant stretching of local lattices of the BFO films along the out-of-plane direction. The locally enhanced out-of-plane lattice constants were confirmed by the HAADF-STEM imaging in a later section. The rocking curves (Fig. 2d, e) show that the full-width-half-maximum of the BFO1, BFO2 and BFO are 0.051°, 0.052°, and 0.049°, respectively, indicating that the ferroelectric films show high crystalline quality. The obtained thicknesses of all film layers in both samples A and B by fitting X-ray reflectivity (XRR) curves (Supplementary Fig. 4) are consistent with the expected values. Surface topography measurements show that the samples A (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and B (Supplementary Fig. 5b) have the smooth surfaces with the root-mean-square roughness of about 187 pm and 158 pm, respectively. The piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) measurements demonstrate that the upper ferroelectric layers in both samples A (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and B (Supplementary Fig. 5d) show a single out-of-plane polarization component. The hysteresis behaviors (PFM phase signal) and butterfly-like shapes (PFM amplitude signal) of both samples A (Fig. 2f) and B (Fig. 2g) confirm that the BFO films present switchable ferroelectricity at room temperature.

a XRD θ–2θ scans of both samples A (solid red line) and B (solid blue line). RSM images around the (103) STO Bragg peaks for the samples A (b) and B (c). d, e Rocking curves around the (002) diffraction peaks of the BFO1 (top panel) and BFO2 (bottom panel) for sample A (d) and BFO for sample B (e). Out-of-plane PFM phase (top panels) and amplitude (bottom panels) versus voltage hysteresis loops for samples A (f) and B (g).

Chemical composition characterization of interface elements

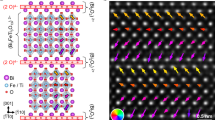

Chemical information for the bottom and top interfaces of both samples A and B has been carefully examined by atomically resolved X-ray energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The EDS elemental maps and signal intensity profiles (Fig. 3a, e) for the bottom interface of sample A reveal that the bottom BFO layer is grown on a TiO2-terminated STO substrate. Note that the bottom BFO layer begins with A-site growth, although some strontium and bismuth intermixing is apparent in the first bismuth layer inside BFO. The EDS elemental maps and signal intensity profiles (Fig. 3b, f) for the top interface of sample A show that the top BFO layer is grown on the SrO-terminated interface and begins with B-site growth. By the EDS elemental maps and signal intensity profiles from the bottom (Fig. 3c, g) and top (Fig. 3d, h) interfaces of sample B, we can identify that the bottom and top BFO layers are grown on SrO-terminated and TiO2-terminated interfaces, respectively. Therefore, we have successfully prepared the BFO bilayer as expected by precisely controlling growth.

Atomically resolved HAADF-STEM images and EDS elemental maps of strontium, titanium, bismuth and overlay signals for the bottom (a) and top (b) interfaces of sample A and bottom (c) and top (d) interfaces of sample B, respectively. EDS intensity profiles of strontium, titanium, bismuth and iron signals across the bottom (e) and top (f) interfaces of sample A and bottom (g) and top (h) interfaces of sample B, respectively. The asterisk refers to the location of the termination layer that is close to the BFO layer at the interface. All the scale bars in a–d are 1 nm.

Polarization state and microstructure analyses of BiFeO3 thin films

To demonstrate the polarization states at the microscopic of the ferroelectric bilayers, we performed atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM imaging on the samples. The cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images of both samples A (Fig. 4a) and B (Fig. 4b) taken along STO [100] zone axis demonstrate atomically sharp interfaces and high-quality epitaxial growth, consistent with the XRD results. The chemical compositions of atomic rows at the interfaces for samples A and B are shown in the enlarged atomic images denoted by colored spheres, which present exactly the same atomic stacking structures as we designed. For BFO systems, the spontaneous polarization vector (\({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{{\rm{s}}}\)) and the relative displacement vector (\({{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{{\rm{Fe}}}\)) of B-site Fe atom with respect to the mass center of the four surrounding A-site atoms satisfy the empirical linear relation \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{{\rm{s}}}=k\,* \,{{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{{\rm{F}}{\rm{e}}}\), where k is a constant for roughly estimating polarization and \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{{\rm{s}}}\) is in the opposite direction of \({{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{{\rm{Fe}}}\)41,45,46,47,48,49,50. The \({{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{{\rm{Fe}}}\) can be directly measured by a two-dimensional Gaussian fitting approach50. Figure 4c, d shows the polarization vector (\({-{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{{\rm{Fe}}}\)) maps of the BFO bilayers in samples A and B, respectively. In sample A, we found that the out-of-plane spontaneous polarization direction of the bottom BFO layer grown on TiO2-terminated STO substrate is upward, while that of top BFO layer grown on SrO-terminated STO interlayer is downward. In sample B, the out-of-plane polarization component of the bottom BFO layer grown on SrO-terminated STO substrate presents a downward direction, whereas that of the top BFO layer grown on TiO2-terminated STO interlayer shows an upward direction. As a result, the head-to-head and tail-to-tail polarization configurations are formed in the multilayer systems. In addition, from the polarization vector maps of both samples A and B, we can clearly observe that the polarization vectors of the BFO layers grown on SrO-terminated layers slightly rotate into the out-of-plane direction compared to those of the BFO layers grown on TiO2-terminated layers. It has been reported that the accumulation of oxygen vacancies at the interfacial layer can promote the ferroelectric polarization of an ultrathin BFO film to rotate toward the out-of-plane direction51. Therefore, this polarization rotation can be ascribed to the introduction of oxygen vacancies at the (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 interface due to the compensation for the extra interface charges.

High-resolution cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images of samples A (a) and B (b) viewed along the STO [100] zone axis. The colored spheres indicate atomic species near the interfaces (inset). c, d Polarization vector maps superimposed on the magnified HAADF-STEM images from the red dashed rectangle regions in a and b, respectively. The yellow arrow shows the polarization vector in each unit cell. Extracted c- and a-axis lattice parameters of samples A (e) and B (g), and the out-of-plane Fe atom displacements and out-of-plane ferroelectric polarization of samples A (f) and B (h) by averaging the position value from each lattice layer along the atomic rows denoted by numbers in a and b. Error bars denote standard deviation.

Further, we make a quantitative analysis on local lattice parameters and ferroelectric polarization of the BFO thin films. Figure 4e, g shows the extracted c- and a-axis lattice parameters from the lattice layers denoted by the corresponding numbers in Fig. 4a, b. The in-plane lattice constants of all BFO layers for both samples A and B are close to that of the STO bulk value (3.905 Å), confirming that all ferroelectric layers are in a fully strained state. For sample A, the out-of-plane lattice constant of top BFO layer increases dramatically from the top interface to the sample surface and eventually tends toward a stable peak value of about 4.12 Å. The out-of-plane lattice constant of the bottom BFO layer exhibits a slight decrease within 2 unit cells near the (SrO)0/(FeO2)– (middle) interface and finally keeps a relatively uniform value of about 4.03 Å in the film interior. For sample B, the out-of-plane lattice constant of top BFO layer has an almost uniform value of about 4.06 Å except for a slight reduction at the top interface, while that of bottom BFO layer displays a very small uptrend from the (TiO2)0/(BiO)+ (middle) interface to the film interior. The c/a ratios extracted from local lattice parameters are quite consistent with that of XRD and RSM results. Figure 4f, h shows the local out-of-plane Fe atom displacements \((\mid{D}_{{\rm{Fe}}}^{\left({\rm{z}}\right)}\mid)\) and out-of-plane ferroelectric polarization of BFO layers for samples A and B, respectively. Strikingly, \(\mid{D}_{{\rm{Fe}}}^{\left({\rm{z}}\right)}\mid\) and the magnitude of out-of-plane polarization components for all BFO layers of both samples A and B exhibit a similar manner to their c (or c/a ratios). At the film interior near the surface of sample A, the out-of-plane polarization can be estimated to be about 82 µC cm−2, nearly 68% greater than that of BFO near the interfaces.

Polar discontinuities at the interfaces

Finally, we explain the polarization behaviors of BFO bilayers by using the polar discontinuity model52,53. The (001) planes in the ABO3 perovskite structure can be regarded as a stack of alternating layers of AO and BO2 planes. BFO contains polar (BiO)+ and (FeO2)– planes, while the neighboring (TiO2)0 and (SrO)0 at the interfaces are the charge-neutral sheets. Thus, two kinds of atomically abrupt interfaces, (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 and (FeO2)–/(SrO)0, between polar and neutral layers can be created. The sheet charge density at the (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 interface is assigned to be + e/0 (e is the electron charge), which induces a nominal extra interface charge of + 0.5e11,54. In general, the charges at the interfaces are redistributed to avoid a polar catastrophe (diverging electrostatic potential). The TiO2 layer at the (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 interface must acquire an extra half an electron per two-dimensional unit cell to maintain the overall structure neutral. The extra interface charges are compensated by mixed-valence Ti states (from Ti4+ to Ti3.5+). Similarly, the sheet charge density at the (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 interface induces a nominal extra interface charge of – 0.5e. The SrO layer at the (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 interface must acquire an extra half a hole per two-dimensional unit cell to maintain charge neutrality. Ultimately, the extra interface charges are compensated by the introduction of the positively charged oxygen vacancies at the interface because Sr has no available mixed-valence states. Actually, even after this charge compensation, there remains a finite electrostatic potential at the interfaces, giving an interface dipole which varies with the interface termination54. Eventually, the interface dipoles pointing from the TiO2 to the interface and pointing from the interface to the SrO are formed at the (BiO)+/(TiO2)0 and (FeO2)–/(SrO)0 interfaces, respectively.

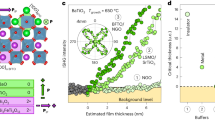

Based on this model, the charge configurations of samples A and B are schematically shown in Fig. 5. For sample A (Fig. 5a), the interface dipoles pointing from the TiO2 to the bottom interface and pointing from middle interface to the SrO are formed due to the nominal positive interface charge of + 0.5e and negative interface charge of – 0.5e at the bottom and middle interfaces, respectively. As a result, an electrostatic potential step pointing from bottom to middle interface forms due to the electrostatic potential difference between the two inequivalent interfaces. As previously reported in BFO/La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 heterostructure11, the total energy of the system is lower when the direction of ferroelectric polarization is in agreement with the sign of this electrostatic potential step. Thus, the out-of-plane component of ferroelectric polarization in the bottom BFO layer is upward. The top BFO layer presents the downward polarization, which can be attributed to the electrostatic potential step between the top interface and the polar surface of sample A. For sample B (Fig. 5b), the polar discontinuities at the bottom and middle interfaces give rise to the interface dipoles pointing from the bottom interface to the SrO and pointing from the TiO2 to the middle interface, respectively. Hence, a potential step forms between the bottom and middle interfaces and eventually results in the downward polarization in the bottom BFO layer. The upward polarization in the top BFO layer results from the electrostatic potential step between the top interface and the polar surface of sample B. It should be emphasized that in this model, the uppermost BiO layer in sample A would be missing half a hole, and the uppermost FeO2 layer in sample B would be missing half an electron to avoid diverging electrostatic potential. Actually, the surface reconstruction is more complicated.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated an effective strategy to control ferroelectric polarization in BFO bilayer films. By precise control of growth at the atomic scale, we can modify the surface terminations of STO interlayers and STO substrates in the multilayers of BFO/STO/BFO grown on TiO2-terminated STO substrates, which have been carefully examined by atomically resolved EDS measurements. Polarization vector maps superimposed on HAADF-STEM images reveal that the out-of-plane polarization direction of each of the ferroelectric layers in the multilayer systems can be controlled independently, thus leading to the formation of head-to-head and tail-to-tail polarization configurations. Moreover, the locally enhanced c/a ratio and out-of-plane polarization component are observed in the head-to-head configuration, which is probably associated with the boundary condition of the sample surface. This work opens the possibility to discover emergent phenomena in the ferroelectric multilayers with pre-designed polarization states and may promote the potential of ferroelectric multilayers for innovative device applications.

Methods

Sample preparation

The epitaxial multilayer systems were deposited on atomically smooth TiO2-terminated single-crystalline STO (001) substrates via pulsed laser deposition. All the film layers were deposited at a growth temperature of 640 °C and an oxygen atmosphere of 10 Pa. During the deposition, a XeCl excimer laser (λ = 308 nm) was employed to strike the ceramic BFO, TiO2, and SRO targets and single-crystal STO target at a fixed energy density of ∼1.5 J/cm2 and a pulse repetition rate of 1 Hz. After the deposition, the films were in-situ annealed for 10 min to improve the crystallinity and then were cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 10 °C/min.

X-ray characterization

The XRD θ-2θ scans, RSM, rocking curves, phi scans and XRR measurements were performed using an X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical X’Pert3 MRD) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation source and a 3D pixel detector.

AFM and PFM measurements

The images of surface topography and PFM measurements were performed at room temperature using a commercial scanning probe microscope (Asylum Research MFP-3D), and the Ti/Pt-coated silicon tips (AC240TM, Olympus) were used in this study.

STEM measurements

Cross-sectional TEM samples were prepared by mechanical polishing and then subjected to argon ion-beam milling (Gatan PIPS 695) with an acceleration voltage of 2.8 kV for quick milling, followed by the final 0.2 kV to electron beam transparent. The HAADF images were obtained using an aberration-corrected STEM (JEOL ARM 300 F) operating at 300 kV. The collection semi-angles for HAADF imaging was in the 54–220 mrad range, and convergence semi-angle was 22 mrad. EDS elemental mapping was collected using a Super-X EDS detector. The position of each atom was determined by a two-dimensional Gaussian peak-fitting method using MATLAB code. The polarization was obtained by measuring the displacement of the B-site Fe atom with respect to the center of the unit cell formed by four surrounding A-site atoms. The direction of the polarization vector is opposite to the displacement vector of the Fe atom.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dawber, M., Rabe, K. M. & Scott, J. F. Physics of thin-film ferroelectric oxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1083–1130 (2005).

Martin, L. W. & Rappe, A. M. Thin-film ferroelectric materials and their applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16087 (2016).

Eerenstein, W., Mathur, N. D. & Scott, J. F. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 442, 759–765 (2006).

Spaldin, N. A., Cheong, S.-W. & Ramesh, R. Multiferroics: past, present, and future. Phys. Today 63, 38–43 (2010).

Bhattacharya, A. & May, S. J. Magnetic oxide heterostructures. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 65–90 (2014).

Wu, S. M. et al. Reversible electric control of exchange bias in a multiferroic field-effect device. Nat. Mater. 9, 756–761 (2010).

Garcia, V. et al. Giant tunnel electroresistance for non-destructive readout of ferroelectric states. Nature 460, 81–84 (2009).

Chanthbouala, A. et al. Solid-state memories based on ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 101–104 (2012).

Jiang, J. et al. Temporary formation of highly conducting domain walls for non-destructive read-out of ferroelectric domain-wall resistance switching memories. Nat. Mater. 17, 49–55 (2018).

Garcia, V. & Bibes, M. Ferroelectric tunnel junctions for information storage and processing. Nat. Commun. 5, 4289 (2014).

Yu, P. et al. Interface control of bulk ferroelectric polarization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 9710–9715 (2012).

Becher, C. et al. Functional ferroic heterostructures with tunable integral symmetry. Nat. Commun. 5, 4295 (2014).

Luca, G. D. et al. Nanoscale design of polarization in ultrathin ferroelectric heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 8, 1419 (2017).

Strkalj, N. et al. In-situ monitoring of interface proximity effects in ultrathin ferroelectrics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5815 (2020).

Gradauskaite, E. et al. Magnetoelectric phase control at domain-wall-like epitaxial oxide multilayers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412831 (2025).

Tian, S. et al. Manipulating the ferroelectric domain states and structural distortion in epitaxial BiFeO3 ultrathin films via Bi nonstoichiometry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 43792–43801 (2018).

Sarott, M. F. et al. Controlling the polarization in ferroelectric PZT films via the epitaxial growth conditions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214849 (2023).

Efe, I., Yan, B. & Trassin, M. Engineering of ferroelectricity in thin films using lattice chemistry: A perspective. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 150503 (2024).

Spaldin, N. A. et al. Layer and spontaneous polarizations in perovskite oxides and their interplay in multiferroic bismuth ferrite. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 154702 (2021).

Das, S. et al. Observation of room-temperature polar skyrmions. Nature 568, 368–372 (2019).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Observation of polar vortices in oxide superlattices. Nature 530, 198–200 (2016).

Li, Q. et al. Subterahertz collective dynamics of polar vortices. Nature 592, 376–380 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Rewritable ferroelectric vortex pairs in BiFeO3. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 43 (2017).

Liu, D. et al. Phase-field simulations of vortex chirality manipulation in ferroelectric thin films. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 34 (2022).

Nguyen, M. D. et al. Toward design rules for multilayer ferroelectric energy storage capacitors – a study based on lead-free and relaxor-ferroelectric/paraelectric multilayer devices. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402070 (2024).

Spaldin, N. A. & Fiebig, M. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science 309, 391–392 (2005).

Ramesh, R. & Spaldin, N. A. Multiferroics: progress and prospects in thin films. Nat. Mater. 6, 21–29 (2007).

Lu, C. et al. Multiferroic oxide thin films and heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 021304 (2015).

Fiebig, M. et al. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16046 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science 299, 1719–1722 (2003).

Choi, T. et al. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Science 326, 977–980 (2009).

Balke, N. et al. Enhanced electric conductivity at ferroelectric vortex cores in BiFeO3. Nat. Phys. 8, 81–88 (2012).

Sando, D. et al. Crafting the magnonic and spintronic response of BiFeO3 films by epitaxial strain. Nat. Mater. 12, 641–646 (2013).

Heron, J. T. et al. Deterministic switching of ferromagnetism at room temperature using an electric field. Nature 516, 370–373 (2014).

Husain, S. et al. Low-temperature grapho-epitaxial La-substituted BiFeO3 on metallic perovskite. Nat. Commun. 15, 479 (2024).

Liou, Y.–D. et al. Deterministic optical control of room temperature multiferroicity in BiFeO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 18, 580–587 (2019).

Paull, O. et al. Anisotropic epitaxial stabilization of a low-symmetry ferroelectric with enhanced electromechanical response. Nat. Mater. 21, 74–80 (2022).

Rijnders, G. et al. Enhanced surface diffusion through termination conversion during epitaxial SrRuO3 growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 505–507 (2004).

Kawasaki, M. et al. Atomic control of the SrTiO3 crystal surface. Science 266, 1540–1542 (1994).

Koster, G. et al. Quasi-ideal strontium titanate crystal surfaces through formation of strontium hydroxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 2920–2922 (1998).

Xie, L. et al. Giant ferroelectric polarization in ultrathin ferroelectrics via boundary-condition engineering. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701475 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Origin of a tetragonal BiFeO3 phase with a giant c/a ratio on SrTiO3 substrates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 937–942 (2012).

Martí, X. et al. Skin layer of BiFeO3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236101 (2011).

Jarrier, R. et al. Surface phase transitions in BiFeO3 below room temperature. Phys. Rev. B. 85, 184104 (2012).

Jia, C.–L. et al. Unit-cell scale mapping of ferroelectricity and tetragonality in epitaxial ultrathin ferroelectric films. Nat. Mater. 6, 64–69 (2007).

Wang, H. et al. Overcoming the limits of the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction by antiferromagnetic order in multiferroic heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904415 (2020).

Huyan, H. et al. Direct observation of polarization-induced two-dimensional electron/hole gases at ferroelectric-insulator interface. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 88 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Controlled growth and atomic-scale mapping of charged heterointerfaces in PbTiO3/BiFeO3 bilayers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 25578–25586 (2017).

Campanini, M. et al. Periodic giant polarization gradients in doped BiFeO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 18, 717–724 (2018).

Nelson, C. T. et al. Spontaneous vortex nanodomain arrays at ferroelectric heterointerfaces. Nano Lett. 11, 828–834 (2011).

Li, L. et al. Observation of strong polarization enhancement in ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nano Lett. 19, 6812–6818 (2019).

Nakagawa, N., Hwang, H. Y. & Muller, D. A. Why some interfaces cannot be sharp. Nat. Mater. 5, 204–209 (2006).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. Y. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Hikita, Y. et al. Termination control of the interface dipole in La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/Nb:SrTiO3 (001) Schottky junctions. Phys. Rev. B 79, 073101 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant nos. 2021YFA1400700, 2020YFA0309100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 12304122, 12174437, 12474096, 12222414, 12334001), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (Grant no. Y2022003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. and C.W. conceived the project and designed the experiments. C.W. and K.J. performed the overall supervision of the work. X.Y., X.W., N.L., T.Y., and R.W. synthesized the samples and performed XRD and PFM measurements. X.Y., L.L., L.W., and X.B. conducted STEM/EDS experiments. M.H., E.-J.G., C.G., and G.Y. provided valuable discussions. X.Y. and C.W. analyzed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the data and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, X., Wang, C., Liao, L. et al. Control of ferroelectric polarization in BiFeO3 bilayer films through interface engineering. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00763-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00763-6