Abstract

Chromium ditelluride, CrTe2, is an attractive candidate van der Waals material for hosting 2D magnetism. However, how the room-temperature ferromagnetism of the bulk evolves as the sample is thinned to the single-layer limit has proved controversial. This, in part, reflects its metastable nature, vs. a series of more stable self-intercalation compounds with higher relative Cr:Te stoichiometry. Here, exploiting a recently developed method for enhancing nucleation in molecular-beam epitaxy growth of transition-metal chalcogenides, we demonstrate the selective stabilisation of high-coverage CrTe2 and Cr2+εTe3 epitaxial monolayers. Combining X-ray magnetic circular dichroism, scanning tunnelling microscopy, and temperature-dependent angle-resolved photoemission, we demonstrate that both compounds order magnetically with a similar TC. We find, however, that monolayer CrTe2 forms as an antiferromagnetic metal, while monolayer Cr2+εTe3 hosts an intrinsic ferromagnetic semiconducting state. This work thus demonstrates that control over the self-intercalation of metastable Cr-based chalcogenides provides a powerful route for tuning both their metallicity and magnetic structure, establishing the CrxTey system as a flexible materials class for future 2D spintronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The MX2 transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs, M=transition metal, X={S,Se,Te}) are one of the most prominent current classes of 2D materials1,2,3. However, despite the wide array of crystal structures and transition metal d-electron occupancies that can be realised across this family4, most TMDs are non-magnetic. In contrast, magnetic order has been more notable in the layered halides such as CrI3, or ternary chalcogenides such as CrGeTe3 or Fe3GeTe2, where long-range magnetic order has been found to persist to the bi- or even monolayer (ML) limit5,6,7. Nonetheless, for materials simplicity, as well as structural and fabrication compatibility for the formation of integrated heterostructures, it remains of strong interest to develop intrinsic 2D magnetic systems within the TMD family.

One of the most promising candidates is CrTe2. While this compound is only metastable, Freitas et al.8 successfully demonstrated the synthesis of bulk 1T-CrTe2 samples by de-intercalating K from KCrTe2. The de-intercalated samples exhibit itinerant ferromagnetism with a Curie temperature (TC) of 310 K. This suggests a robust ferromagnetic order in this quasi-2D layered system, raising hopes to maintain long-range order down to the single-layer thickness limit. However, studies of the evolution of its magnetic order with sample thickness have proved controversial to date. Lingjia et al.9 fabricated multi-layer 1T-CrTe2 by chemical vapor deposition (CVD), finding an unconventional increase in the reported Curie temperature with decreasing film thickness down to ≈8 nm, but with a TC in 130 nm-thick samples only around half that of the bulk crystals. Combined first-principles and Monte Carlo calculations have suggested that ferromagnetism should be stable in the ML limit10, albeit with a strongly reduced TC, and with a significant tunability with applied strain, electron and hole doping, and varying the number of layers. There have been several attempts to study this ML regime in samples grown by molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE). Zhang et al.11 reported the observation of a persistent ferromagnetic order, with TC above room temperature in few-layer films, and dropping to 200 K in the ML. However, the samples investigated had an anomalously large in-plane lattice constant. In contrast, from spin-polarised scanning tunnelling microscopy experiments, Xian et al.12 concluded that ML-CrTe2 orders antiferromagnetically, although with an unknown Néel temperature, TN. Further studies of the putative magnetic order of ML-CrTe2 are thus urgently required.

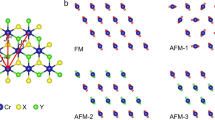

A challenge is the metastable nature of this compound. In an ionic picture, the Cr ions in CrTe2 would be expected in a nominal 4+ configuration. This would lead to an unstable d2 charge count. The compound would thus be expected to preferentially form in a bilayer configuration, with additional Cr atoms intercalating within the van der Waals gap to move towards the stable Cr d3 (Cr3+) configuration (Fig. 1a, b). Indeed, a variety of intercalated Cr1+δTe2 phases are known to exist (Cr2Te3, Cr3Te4, Cr5Te8), depending on the partial occupancy of intercalated Cr atoms. Lasek et al.13,14 have previously demonstrated a strong sensitivity of the stabilised CrTe phase to the growth conditions used as well as post-growth annealing, with a marked propensity for transformation to the self-intercalated phases, and only small ML patches of CrTe2 obtained. The more Cr-rich intercalated phases have been shown to exhibit clear magnetic signatures15,16,17,18, making it challenging to isolate and characterise the intrinsic magnetic properties of ML-CrTe2.

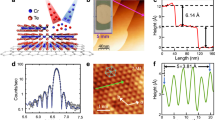

a Side view of the crystal structure of ML-CrTe2 and ML-Cr2Te3 on an HOPG substrate. b Schematic of the formation of the Cr1+δTe2 phases with Cr atoms self-intercalating within the van der Waals gap of CrTe2. c, d RHEED patterns of samples grown at a substrate temperature of (c) Ts = 400 °C and (d) Ts = 700 °C [Cr cell temperature: 1025 °C], and (e) corresponding intensity profiles extracted from the shaded regions in (c, d). The extracted in-plane lattice constants (stars in (i)) are consistent with CrTe2 and [Cr2Te3, Cr3Te4], respectively. f, g AFM images for the samples shown in (c, d). h AFM line profiles corresponding to the lines shown in (f, g), revealing the different thickness of the monolayer islands, again consistent with CrTe2 and [Cr2Te3, Cr3Te4], respectively. i Obtained growth phase diagram of CrxTey as a function of substrate and Cr effusion cell temperature, as determined from lattice constant measurements from RHEED. Stars indicate the in-plane lattice constants as measured from samples for which the corresponding RHEED and AFM images are shown in (c, d, f, g).

In this work, we present a controlled methodology for realising the MBE growth of different CrxTey phases with enhanced coverage and phase purity. Utilising an ion-assisted method19 to enhance the nucleation of the growing film, we realise much higher coverage of nearly phase-pure CrTe2 and Cr2+εTe3 MLs, allowing their subsequent investigation by X-ray absorption, photoemission, and scanning-probe spectroscopies. Through this, we identify that both compounds order magnetically in the ML limit, but with markedly distinct magnetic and electronic structures.

Results

Epitaxial growth of phase-selective CrxTey

Figure 1 shows the growth of ML CrxTey epitaxial layers via MBE, with control over the stoichiometry obtained by tuning the growth conditions used. We show in Fig. 1c, d, f, g reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements from samples grown on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) substrates (see Methods), at a substrate temperature of Ts = 400 °C and Ts = 700 °C, respectively. Clear diffraction streaks from the growing epilayer as well as the underlying substrate are evident. Due to the presence of rotationally randomly aligned grains of the growth substrate, we observe both [0, n] and [n, n] type diffraction orders here (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Comparing the location of the film streaks for the samples grown at different temperature (Fig. 1e), it is clear that a lower growth temperature leads to epilayer diffraction streaks which are located at a larger wavevector (corresponding to a smaller in-plane lattice constant) than for the epilayer streaks for the sample grown at the higher substrate temperature. From fitting the extracted line profiles across multiple grown samples, we find lattice constants of a = 3.66 ± 0.04 Å (a = 3.88 ± 0.02 Å) for the samples grown at Ts = 400 °C (700 °C), respectively. These values are within experimental error of the in-plane lattice constant expected for 1T-CrTe2 (3.69 Å) and the Cr-intercalated phases, Cr2Te3 and Cr3Te4(3.93 Å), respectively13.

Consistent with this, our AFM measurements (Fig. 1f–h) indicate a clear impact of substrate temperature on the as-grown epi-islands. At Ts = 400 °C, while limited adatom mobility restricts edge diffusion, resulting in irregular island shapes, the substrate is nearly entirely covered with a single epilayer, with just occasional bilayer patches visible, and a few gaps to the substrate below. Conversely, at the higher substrate temperature, enhanced adatom surface diffusion leads to more triangular island shapes20, but a lower surface coverage, indicating a slower growth rate. The slower growth rate is attributed to the lower sticking coefficient of Cr and Te at the elevated temperature. To confirm this, we have examined the growth of Cr2Te3 at an even higher growth temperature of 800 °C, where the polymorph is stable, but where we observed a significant further reduction in total coverage as compared to the growth at 700 °C, as well as the formation of spotty RHEED images. The latter may indicate a lack of Te supply at these most elevated temperatures, despite the high Te:Cr ratio utilised during the growth, potentially leading to the formation of Cr clusters at the growth surface. We thus restrict our growth to lower temperatures in the following.

Extracted AFM height profiles from the first epilayer to the substrate below (Fig. 1h) yield average ML step heights of 0.95 ± 0.08 nm and 1.48 ± 0.09 nm for the samples grown at Ts = 400 °C and 700 °C, respectively. The former is consistent with the AFM step height typically obtained for the first ML of an MX2 TMD. We note that AFM typically overestimates the layer thickness due to distinct tip-sample and tip-substrate interactions, and the possible differences of the effects of air exposure on the different layers, but the good agreement with typically-observed TMD ML heights again indicates that our samples grown at Ts = 400 °C are 1T-CrTe2 MLs. To confirm this more quantitatively, the step height of the MLs were measured using scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) (Supplementary Fig. 2). We find a measured height of 1.0 ± 0.1 nm, consistent with the theoretical value of 1.0 nm calculated using density functional theory once an electronic contribution is considered (see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Methods section for calculation details). In contrast, a higher minimum step height observed for the higher temperature growths again points to the fact that growth proceeds immediately to the formation of a self-intercalated phase under these conditions. We note that the small additional height over the CrTe2 ML, as well as the small step to the bilayer patches visible in Fig. 1f, indicates growth of a quintuple layer Te-CrTe-CrTe structure as shown in Fig. 1a, rather than the fabrication of a full bilayer of CrTe2 with additional Cr self-intercalation (Fig. 1b). We refer to the former as an ML of the self-intercalated structure in the following.

The above findings are broadly in line with those reported by Lasek et al.13, but we are able to stabilise the CrTe2 phase at higher substrate temperatures and with much larger island sizes across the substrate. This is because our samples are grown using co-evaporation of a minute quantity of Ge from an electron-beam evaporator (see Methods). We have recently shown how the exposure of the substrate to the flux of excited Ge ions from such a source induces substrate defects, which dramatically enhance the nucleation of the growing epilayer19. Indeed, under the same growth conditions used here but without co-exposure to the Ge ions, we find significantly more limited coverage of CrTe2 even with an extended growth duration, with growth occurring primarily along the substrate step edges (see Supplementary Fig. 5). The use of our ion-assisted nucleation strategy here is thus essential to obtain larger-area and significantly more uniform growth of ML-CrTe2, and leads to a significantly enhanced growth window, yet with negligible incorporation of Ge into the growing film (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

As discussed above, and shown in Fig. 1i, even with our assisted nucleation method, we can only stabilise CrTe2 at relatively low growth temperatures. Even at these low growth temperatures, we already observe a small tendency for increased Cr flux during the growth to promote self-intercalation, which leads to a gradual increase in the lattice constant and bilayer formation. However, at higher growth temperatures, the lattice constant is not affected significantly by changes in Cr flux, as the phase transformation to the bilayer compound has already taken place. This highlights the importance of carefully controlling both the growth temperature and Cr flux to stabilize ML-CrTe2.

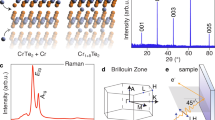

While the obtained lattice constants and AFM step heights allow the ready identification of 1T-CrTe2, they do not allow a reliable determination of the stoichiometry of the self-intercalated phases grown at higher temperatures, which all host similar in-plane lattice constants and ML-layer heights to each other. We thus adopt atomic-scale imaging using STM, which is sensitive to the different lateral periodicities of the self-intercalated Cr ions for the different stoichiometries13. As shown in Fig. 2b, c, for a sample grown with a substrate temperature of Ts = 600 °C and a low Cr cell temperature of 1015 °C, a set of islands with largely uniform heights is found distributed across the sample. Atomic-resolution imaging (Fig. 2c) shows a disordered lattice, but with an average additional super-periodicity of \((\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3})R3{0}^{\circ }\) evident in the patches visible in the STM topography and in fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis. This is consistent with the additional periodicity expected for intercalated Cr atoms in the van der Waals gap for a Cr2Te3 phase (Fig. 2a). Similar periodicity is found at any island investigated, allowing us to identify the dominant phase here as Cr2Te3, although with some site disorder evident. We thus refer to this phase as Cr2+εTe3. Including electronic contributions, the measured step height of these islands is 1.3 ± 0.1 nm, again consistent with the predictions from density functional theory of 1.3 nm for a Cr2Te3 ML (see Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, when using a higher Cr cell temperature of 1100 °C during the growth (Fig. 2d–f), we find higher multi-layer coverage and much more pronounced variations across the sample surface. Some regions (Fig. 2e) again show a \((\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3})R3{0}^{\circ }\) order, but with greater local-scale order and uniformity than for the sample grown with lower Cr flux. The difference in disorder between the samples grown with different Cr fluxes is reflected in the Fourier transform of STM images (in Figs. 2c, e). For the high Cr cell temperature sample, the peaks corresponding to the \((\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3})R3{0}^{\circ }\) periodicity are very sharp, indicating a highly ordered crystal, whereas those for the disordered structure grown with a lower Cr cell temperature are much more diffuse. Other regions on the same high Cr flux sample show a (2 × 1) superstructure (Fig. 2f), indicative of Cr3Te4. This points to an intrinsic phase separation into more Cr-rich and Cr-poor regions which—while it may lead to greater crystalline order on a local scale—leads to undesired mesoscopic variations in the stoichiometry. For the remainder of this work, we thus restrict our studies to the low Cr flux regime, where Cr2+εTe3 is found across the sample surface.

a Schematic top view (projected along [0001]) and side view (projected along \([2\overline{1}\overline{1}0]\) and \([10\overline{1}0]\) respectively) of the crystal structure of a Cr2Te3 and Cr3Te4 ML. The self-intercalated Cr atoms are shown in pink. b–f STM images at 1.6 K of CrxTey MLs synthesized using a Cr effusion cell temperature of (b, c) 1015 °C and (d–f) 1100 °C: (b, d) overview measurements; (c, e, f) high resolution measurements from the regions shown in (b, d), with corresponding magnified views (inset) and Fourier transforms shown. The Fourier images show Bragg peaks corresponding to the CrTe2 lattice (green circles). In addition, the regions in (c) and (e) show an additional \((\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3})R3{0}^{\circ }\) superstructure order, corresponding to Cr2Te3, while (f) shows a (2 × 1) superstructure, consistent with Cr3Te4 (highlighted by orange circles in the FFT). Ball models show the proposed atomic structure of the islands. Tunnelling setpoints: (b) Vs = 900 mV, Is = 50 pA, (c) and inset Vs = −300 mV, Is = 75 pA, (d) Vs = 900 mV, Is = 60 pA, (e) and inset Vs = −200 mV, Is = 100 pA, (f) and inset Vs = −200 mV, Is = 100 pA.

Dichotomy in magnetic order and electronic structure

To investigate the intrinsic magnetic order of such Cr2+εTe3 MLs, as well as our CrTe2 samples, we employed X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD). We show XAS measurements in Fig. 3a, b performed using circularly-left and -right polarised light over the photon energy range from 560 to 600 eV. Consistent with previous studies of bulk compounds and thin films, the Te M5 edge which occurs in this energy range does not have a strong intensity21,22,23,24, contributing at most a small shoulder on the low photon energy side of the Cr L3 peak. Our measurements are thus dominated by the Cr L2,3 absorption edge, providing a sensitive, element-specific probe of magnetic order in our ML samples. In an applied magnetic field of 1T, our Cr2+εTe3 MLs exhibit a distinctly resolvable magnetic dichroism (Fig. 3a), consistent with that recently reported for other CrTe MLs with a similar in-plane lattice constant to our Cr2+εTe3 samples here11,16. Its form is similar to the XMCD observed in other nominally Cr3+ 2D magnet families such as CrGeTe3, CrSiTe3, and CrI324,25,26, pointing to a dominant spin moment and small orbital moment. Tracking the peak asymmetry of the measured XMCD at the Cr L3-edge as a function of applied magnetic field (Fig. 3c), we find a clear hysteretic behaviour with a saturation field of ~0.5 T, and a coercive field of ~0.1T. This unambiguously confirms that ML-Cr2+εTe3 exhibits long-range ferromagnetic order. In contrast, the XMCD signal that we observe for ML-CrTe2 (Fig. 3b) is both weaker than for its self-intercalated cousin, and it displays an almost linear dependence on the applied field (Fig. 3c). Within our sampling density, we find no resolvable magnetic hysteresis (see also Supplementary Fig. 7) which, in contrast to prior reports11, suggests that CrTe2 does not have a ferromagnetic order in the ML limit. Nonetheless, a clearly resolvable dichroic signal in the applied field still points to the formation of a well-developed local moment in ML-CrTe2, a point which we return to below.

a, b Total-electron yield XAS measurements performed using left- and right-circularly polarised X-rays (μ±), measured from (a) Cr2+εTe3 and (b) CrTe2 monolayer samples across the Cr L2,3 absorption edge at 10 K in a 1 T applied magnetic field. The corresponding XMCD asymmetry [\(({I}^{{\mu }^{-}}-{I}^{{\mu }^{+}})/({I}^{{\mu }^{-}}+{I}^{{\mu }^{+}})\)] is shown below. c Peak-to-peak span of the XMCD L3-edge asymmetry (Δ(XMCD Asymm.), see Supplementary Fig. 4) as a function of the applied magnetic field. Arrows indicate the direction of the magnetic field ramping.

To further explore these contrasting magnetic signatures, we performed additional spectroscopic characterisation of our samples. Figure 4a shows the measured low-temperature electronic structure of our Cr2+εTe3 MLs from angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES). Consistent with previous reports16, we find a pair of dispersive states in the vicinity of the Fermi level, similar to the spin-orbit split Te 5p states observed in related compounds24,27. Somewhat flatter states are obtained at higher energies of E−EF ≈ 1.5 eV. Resonant photoemission measurements (ResPES, Supplementary Fig. 8) allow us to identify the latter as having dominantly Cr atomic character. In a simple picture, this is consistent with a nominal Cr3+ charge state, and hence a half-filled spin-polarised Cr t2g band, being pushed below the Fermi level by the exchange splitting with the formation of a magnetic moment. Nonetheless, we note that this Cr-derived state is still rather dispersive in our measurements, while our ResPES measurements indicate significant Cr partial density of states which extends over essentially the entire valence band region, both pointing to a marked CrTe hybridisation. This is in line with significant ligand hybridisation observed in other Te-based 2D magnets24,28 and is qualitatively consistent with our XAS measurements (Fig. 3a), which are rather smeared out, without a significant pre-peak structure, thus suggesting a significant d-p admixture.

a ARPES measurements of a 1 ML Cr2+εTe3 sample measured at T = 10 K. A magnified view in the vicinity of the Fermi level is shown with enhanced contrast inset, revealing the top of a pair of hole-like valence bands in close proximity to EF. b Measured dI/dV spectrum from an equivalent sample in scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (Vs = 120 mV, Is = 400 pA, lock-in amplitude 3 mV, measured at 1.6 K). A small semiconducting gap is found around the Fermi level. c Cr L3-edge Δ(XMCD Assym.) as a function of temperature, measured in an applied field of 0.1 T. The loss of the dichroism signal in the measured XMCD indicates a ferromagnetic transition temperature of ~150 K.

The band top of the dispersive states at lower binding energies approach, but do not quite reach, the Fermi level (Fig. 4a). While a suppression of the intensity close to the band top, likely arising from ARPES matrix element variations, means locating the precise band top is challenging from these measurements, our corresponding spectroscopy measurements performed with low-temperature STM (Fig. 4b) confirm a gapped state around the Fermi level (see also corresponding quasiparticle interference measurements in Supplementary Fig. 9). We note that previous measurements16 found the dispersive states to cross the Fermi level, leading to a metallic state. We attribute this discrepancy to a likely role of Cr off-stoichiometry from the nominal Cr2Te3 composition. Here, however, our combined tunnelling and photoemission measurements allow us to unambiguously assign the ground state of ML-Cr2+εTe3 as a narrow-gap semiconductor. We find only modest changes in the electronic structure (see Supplementary Fig. 10) when heating the sample above the magnetic TC, as judged from the temperature (~150 K) at which the observed XMCD signal becomes indistinguishable from the background level (Fig. 4c). There is thus no collapse of the exchange splitting, ruling out any significant Stoner character of the observed magnetic order in this system, supporting recent conclusions that the magnetic order in the ML limit of Cr2Te3 is of local-moment character16.

We show in Fig. 5a, the equivalent low-temperature electronic structure measured for our CrTe2 MLs. In contrast to Cr2+εTe3, this system hosts a much flatter band ca. 1 eV below the Fermi level, which our ResPES measurements indicate has dominant Cr character (Supplementary Fig. 8). Dispersive states cross the Fermi level close to 0.5 Å−1. This is consistent with tunnelling spectra from our STM measurements (Fig. 5b), which show a metallic sample, and with theoretical expectations of metallicity for a 1T-phase CrTe2 ML29,30 but is in contrast to the situation for Cr2+εTe3. We note that our ResPES measurements again point to a finite hybridisation with the Cr throughout the valence band region, extending here up to the Fermi level.

a ARPES measurements of a 1 ML-CrTe2 sample measured at T = 8 K. The inset shows metallic states crossing the Fermi level, consistent with (b) measured dI/dV spectrum from scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (Vs = 50 mV, Is = 100 pA, lock-in amplitude 800 μV, measured at 1.6 K). c ARPES measurements at T = 210 K, and (d) corresponding temperature-dependent EDCs extracted at the Γ point, showing (e) a clear temperature-dependent anomaly at T ≈ 140 K. f, g Atomically resolved STM measurements at 1.6 K (f) and associated FFT analysis (g) of ML-CrTe2 (Vs = 250 mV, Is = 250 pA for (f) and inset), showing an underlying structural periodicity associated with a (1× 2) modulation (yellow circle) with an additional real-space zig-zag pattern associated with a (2 × 1) supermodulation (blue circle), respectively. These have been previously associated with the antiferromagnetic spin configuration, as shown schematically in (h)12.

Discussion

As for Cr2+εTe3 our measured electronic structure appears qualitatively similar at low and higher temperatures (Fig. 5a, c). Together with our XMCD measurements and our ResPES measurements (Supplementary Fig. 8), we thus conclude that a rather well-developed local Cr moment persists across the measured temperature range in ML-CrTe2, with the dominantly Cr-derived band being located well below the Fermi level for all temperatures; external field-driven polarisation of this moment can explain the measured XMCD signal in Fig. 3b, c. Nonetheless, our temperature-dependent ARPES measurements (Fig. 5c–e) do show modest temperature-dependent band shifts of the states at E−EF ≈ −2 eV, setting in at a temperature of around 140 K. In CrGeTe324,31, similar temperature-dependent shifts have also been observed, onsetting at the magnetic ordering temperature and serving as a marker of superexchange-type interactions24. Our temperature-dependent ARPES measurements thus suggest that the Cr spins order here below a temperature of ca. 140 K, while our XMCD measurements indicate that this order is not ferromagnetic in nature. Instead, this suggests an antiferromagnetic order, as proposed in recent spin-polarised STM measurements12. Consistent with this, we show atomically resolved STM measurements from our own CrTe2 samples in Fig. 5f. A clear zig-zag pattern is observed, which gives rise to additional peaks in the Fourier transformation corresponding to a (2 × 1) (blue circle in Fig. 5g) (see also Supplementary Fig. 11). Consistent with prior work12, we assign this additional periodicity to magnetic contrast, reflecting a zig-zag type antiferromagnetic order (Fig. 5h).

Our spectroscopic measurements thus point to a strong dichotomy in the electronic and magnetic properties of binary CrTe MLs with control of the Cr stoichiometry. We have established ML-CrTe2 as an antiferromagnetic metal with a Néel temperature of ≈ 140 K, while ML-Cr2+εTe3 hosts a ferromagnetic semiconducting ground state with similar TC ≈ 145 K. In this respect, we conclude that the Cr-based transition-metal chalcogenides are an ideal platform for realising tunable magnetic states in the ML limit. Exploiting assisted nucleation and fine control of growth temperatures and fluxes in molecular-beam epitaxy growth, we have furthermore realised routes to selectively stabilise high-coverage MLs of metastable CrTe2 and Cr2+εTe3 to enable potential exploitation of this tunability.

Methods

Molecular-beam epitaxy

ML CrTe alloys were synthesized on HOPG substrates utilizing a DCA R450 MBE system with a base pressure of ~1 × 10−10 mbar. HOPG substrates were selected due to their van der Waals structure, compatible crystal symmetry, conductive nature, and microscopically uniform surface, making them suitable for both the epitaxial growth and subsequent spectroscopic characterisation. However, the samples have small in-plane grains with random azimuthal orientation, leading to complete azimuthal averaging in our subsequent ARPES measurements.

Cr and Te were evaporated using effusion cells at temperatures of 1015–1100 °C and 425 °C, respectively, achieving a CrTe flux ratio of ~1:200. The HOPG substrates were cleaved using scotch tape immediately before being loaded into the MBE load lock. Prior to the growth, they were outgassed in the growth chamber at 800 °C for ~25 minutes. A controlled growth mechanism was achieved via the co-evaporation of small quantities of Ge ions from an e-beam evaporator. This process facilitates higher growth rates and more uniform growth by creating additional nucleation sites on the growth substrate19. Here, a Ge flux of 1 nA was used, as measured by a flux monitor built into the e-beam source. In situ RHEED was utilized to monitor surface quality and phase formation. After the growth, the samples were cooled in the presence of a Te flux to prevent Te vacancy formation.

Sample characterisation

After the growth, samples were characterised by atomic force microscopy (AFM Park Systems NX10, operating in non-contact mode) and, for some samples, also by STM. The AFM was located in an Ar-filled glovebox, with the samples transferred to the glovebox immediately after removing them from the MBE vacuum system. STM was performed in a home-built low-temperature STM operating in ultra-high vacuum. All measurements were performed at the base temperature of ≈1.6 K. The samples were transferred to the STM via a vacuum suitcase, without exposing their surface to non-UHV conditions. Bias voltages are applied to the sample, with the tip at virtual ground. Tunneling spectra g(V) are recorded using the standard lock-in technique. Angle-resolved photoemission was performed using our lab system, with the samples transferred in situ under UHV from the MBE to the photoemission system. Measurements were conducted using a SPECS PHOIBOS 150 hemispherical electron analyzer, with a photon energy of 21.2 eV (He Iα from a helium discharge lamp). The beam spot size was approximately 0.8 mm. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy and resonant phototemission measurements (with associated XAS) were performed using the I09 beamline of Diamond Light Source. Samples were transferred from our growth system to the measurement system using a vacuum suitcase.

XMCD measurements were performed at the I10 beamline of Diamond Light Source, UK. Prior to removing the samples from the growth system, they were capped with ~1 nm (estimated from the RHEED streak intensity dropping to ~40%) of tellurium deposited at room temperature, followed by deposition of a ~2 nm amorphous selenium layer, as estimated by when the Te RHEED streaks disappear. This protects the samples from oxidation during transfer to the beamline. The caps were thin enough, however, that we could measure XAS directly through the capping layer using total-electron yield detection. The experiments utilized monochromatic synchrotron radiation with 100% left- and right-circular polarization over the energy range of 500 to 600 eV. The magnetic field is applied along the incident beam direction. Measurements were conducted with the field applied normal to the sample, at a temperature of 10 K. Consequently, our results reflect the out-of-plane component of the magnetization.

Density functional theory

DFT calculations of CrxTey and CrTe2 + graphene were performed using Quantum ESPRESSO32,33 with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional34 and projector augmented wave pseudopotentials.

For the structural relaxations, a 6 × 6 × 1 k-grid was used, with an energy cutoff of 40 Ry = 544 eV. The lattice constants and atomic positions were allowed to vary until the force on each atom was lower than 1 × 10−3 Rydberg atomic units = 0.01eV/Å. A DFT-D3 correction35 was included to account for van der Waals interactions between layers. To minimise interactions between unit cells, 30 Å of vacuum was added in the c-axis direction. No magnetism was included in the calculations as it is not expected to have a large effect on the structural parameters of the unit cells.

For the estimation of the electronic contribution to the island step heights measured with STM, measurements were simulated with the Tersoff-Hamann approximation36 using the results of a non-self-consistent field calculation with a 16 × 16 × 1 k-grid and a 40 Ry energy cutoff. The resulting real-space density of states integrated over energy was averaged over x and y to determine its decay as a function of z, the distance from the layer’s surface. A value of 5 × 10−6 was chosen as a threshold, and the corresponding z heights for CrxTey and graphene surfaces were compared to provide a prediction of the apparent height difference.

All structure plots were made using the Vesta software37.

Data availability

The research data underpinning this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/fb50f526-1535-42e7-b545-0e8926b02e5b38.

References

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1 (2017).

Schneider, C., Glazov, M. M., Korn, T., Höfling, S. & Urbaszek, B. Two-dimensional semiconductors in the regime of strong light-matter coupling. Nat. Commun. 9, 2695 (2018).

Chen, X., Lian, Z., Meng, Y., Ma, L. & Shi, S.-F. Excitonic complexes in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 14, 8233 (2023).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263 (2013).

Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270 (2017).

Gong, C. et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265 (2017).

Fei, Z. et al. Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778 (2018).

Freitas, D. C. et al. Ferromagnetism in layered metastable 1T-CrTe2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 176002 (2015).

Meng, L. et al. Anomalous thickness dependence of Curie temperature in air-stable two-dimensional ferromagnetic 1T-CrTe2 grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nat. Commun. 12, 809 (2021).

Yao, M. et al. Control of the magnetic anisotropy and Curie temperature of monolayer 1T-CrTe2 for room temperature application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 011409 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Room-temperature intrinsic ferromagnetism in epitaxial CrTe2 ultrathin films. Nat. Commun. 12, 2492 (2021).

Xian, J.-J. et al. Spin mapping of intralayer antiferromagnetism and field-induced spin reorientation in monolayer CrTe2. Nat. Commun. 13, 257 (2022).

Lasek, K. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of transition metal (Ti-, V-, and Cr-) tellurides: from monolayer ditellurides to multilayer self-intercalation compounds. ACS Nano 14, 8473 (2020).

Lasek, K. et al. Van der Waals epitaxy growth of 2D ferromagnetic Cr(1+δ)Te2 nanolayers with concentration-tunable magnetic anisotropy. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9, 011409 (2022).

Chaluvadi, S. K. et al. Uncovering the lowest thickness limit for room-temperature ferromagnetism of Cr1.6Te2. Nano Lett. 24, 7601–7608 (2024).

Zhong, Y. et al. From Stoner to local moment magnetism in atomically thin Cr2Te3. Nat. Commun. 14, 5340 (2023).

Chua, R. et al. Room temperature ferromagnetism of monolayer chromium telluride with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103360 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Air-stable 2D Cr5Te8 nanosheets with thickness-tunable ferromagnetism. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107512 (2022).

Rajan, A. et al. Epitaxial growth of large-area monolayers and Van der Waals heterostructures of transition-metal chalcogenides via assisted nucleation. Adv. Mater. n/a, 2402254 (2024).

Rajan, A., Underwood, K., Mazzola, F. & King, P. D. C. Morphology control of epitaxial monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 014003 (2020).

Duffy, L. et al. Magnetic proximity coupling to Cr-doped Sb2Te3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 95, 224422 (2017).

Burn, D. M. et al. Cr2Te3 thin films for integration in magnetic topological insulator heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 9, 10793 (2019).

Fujita, R. et al. X-ray spectroscopy for the magnetic study of the van der Waals ferromagnet CrSiTe3 in the few-and monolayer limit. 2D Mater. 9, 045007 (2022).

Watson, M. D. et al. Direct observation of the energy gain underpinning ferromagnetic superexchange in the electronic structure of CrGeTe3. Phys. Rev. B 101, 205125 (2020).

Achinuq, B. et al. Covalent mixing in the 2D ferromagnet CrSiTe3 evidenced by magnetic X-ray circular dichroism. Phys. Status Solidi 16, 2100566 (2022).

Huang, B. et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 544 (2018).

Antonelli, T. et al. Orbital-selective band hybridisation at the charge density wave transition in monolayer TiTe2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 98 (2022).

Bigi, C. et al. Covalency, correlations, and interlayer interactions governing the magnetic and electronic structure of Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 108, 054419 (2023).

Abuawwad, N., dos Santos Dias, M., Abusara, H. & Lounis, S. Noncollinear magnetism in two-dimensional CrTe2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 454001 (2022).

Ataca, C., Şahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Stable, single-layer MX2 transition-metal oxides and dichalcogenides in a honeycomb-like structure. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 8983 (2012).

Trzaska, L. et al. Charge doping into spin minority states mediates doubling of TC in ferromagnetic CrGeTe3. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 4 (2025).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Tersoff, J. & Hamann, D. R. Theory of the scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. B 31, 805 (1985).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. Vesta 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272 (2011).

Kushwaha, N. et al. From ferromagnetic semiconductor to anti-ferromagnetic metal in epitaxial Cr_xTe_y monolayers (dataset). University of St Andrews Research Portal. https://doi.org/10.17630/fb50f526-1535-42e7-b545-0e8926b02e5b

Acknowledgements

We thank Philip Murgatroyd for useful discussions and Martin McLaren for technical support. We gratefully acknowledge support from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Grant Nos. EP/X015556/1, EP/X015599/1, and EP/M023958/1) and the Leverhulme Trust (Grant no. RL-2016-006). We thank Diamond Light Source for access to Beamlines I10 (Proposal MM33239) and I09 (Proposal SI38049), which contributed to the results presented here. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. and A.R. developed the growth methodology and fabricated and characterised the samples. N.K. performed and analysed the ARPES measurements, O.A. the STM measurements, N.K., B.E., L.T., G.v.d.L., and A.R. the XMCD measurements, and N.K., A.R., J.R., and C.S. the XPS and ResPES measurements. D.B., T.-L.L., and P.B. maintained the Diamond I09 and I10 beamlines and provided experimental support; P.D.C.K., P.W., and A.R. directed the project; N.K., O.A., P.W., P.D.C.K., and A.R. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kushwaha, N., Armitage, O., Edwards, B. et al. From ferromagnetic semiconductor to antiferromagnetic metal in epitaxial CrxTey monolayers. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 50 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00772-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00772-5