Abstract

α-MnTe, an A-type collinear antiferromagnet, has recently attracted significant attention due to its pronounced spin splitting despite having net zero magnetization, a phenomenon unique for a new class of magnetism dubbed altermagnetism. In this work, we develop a minimal effective Hamiltonian for MnTe based on realistic orbitals near the Fermi level at both the Γ and A points based on group representation theory, first-principles calculations, and tight-binding modeling. The Hamiltonian exhibits qualitatively distinct electron transport characteristics between these high-symmetry points and for different in-plane Néel vector orientations along the \([11\bar{2}0]\) and \([1\bar{1}00]\) directions. Although the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) is believed to be not important in altermagnets, we show the dominant role of SOC in the spin splitting and valence electrons of MnTe. These findings provide critical insights into altermagnetic electron transport in MnTe and establish a model playground for future theoretical and experimental studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Manipulation and detection of magnetic order parameters in antiferromagnets have been a challenge in spintronics for decades1,2. The main difficulty is that most collinear antiferromagnets respect a combination symmetry operation of a half-translation transformation t1/2 or an inversion operation \({\mathcal{P}}\) with a time-reversal transformation \({\mathcal{T}}\), called the \({t}_{1/2}{\mathcal{T}}\) or the \({\mathcal{PT}}\) symmetry, leading to trivial transport properties, such as the absence of intrinsic anomalous Hall effect and spin-transfer torque. Besides conventional antiferromagnets, altermagnets, as a new variant of antiferromagnets, possess collinear Néel order parameters with zero net magnetization but break the \({t}_{1/2}{\mathcal{T}}\) and \({\mathcal{PT}}\) symmetry3,4,5. The non-relativistic spin group of an altermagnet is distinct from that of both ferromagnetism and conventional antiferromagnetism6,7,8,9,10, so that it leads to the bands of the opposite-spin sublattices in reciprocal space not coinciding and can only be connected through a real-space rotation transformation. Thus, altermagnets are fundamentally distinct from conventional collinear antiferromagnets. The combination of the zero net magnetization of antiferromagnets with the spin-splitting characteristics of ferromagnets enables altermagnets not only to generate \({\mathcal{T}}\)-odd spin transport characteristics, including intrinsic anomalous Hall effect2,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, spin-splitting torque18,19,20,21, and tunneling magnetoresistance22, but also to achieve magnetic stability due to the absence of demagnetizing fields and ultrafast spin dynamic features at terahertz scales23,24,25.

Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) is often considered to be irrelevant or insignificant for the electronic and magnetic properties in an altermagnet because the non-relativistic spin splitting with zero net magnetization is regarded as the main characteristic therein4,16,18. The type of spin splitting in altermagnets, such as planer or bulk d-, g-, and i-wave, should be uniquely determined by the type of collinear antiferromagnetic ordering and the crystal symmetry in an altermagnet26. However, SOC does play a crucial role in many antiferromagnets not only for the topological non-trivial band structures27,28,29,30 but also for the detection and manipulation of the Néel-vector orientation3,31,32,33,34. SOC is known to induce spin mixing and band splitting, such as Rashba-Dresselhaus effect35,36 in non-magnetic materials with the inversion symmetry breaking. The locking between electron spin and momentum under SOC leads to spin-galvanic effect with uniform spin accumulation. In an antiferromagnet, this effect can generate opposite spin-orbital torques on the opposite-spin sublattices, achieving the control of antiferromagnetism31,33. Furthermore, magnetic anisotropy brought about by SOC can alter the symmetry originally determined by the non-relativistic antiferromagnetic system. To this end, analyzing the non-relativistic magnetic ordering and crystal symmetry is not sufficient to catch the full features of the spin splitting in the band structure. Both the strength of SOC and magnetic anisotropy is important in antiferromagnetic and altermagnetic spintronics.

α-MnTe possesses both the altermagnetic characteristics with the absence of \({t}_{1/2}{\mathcal{T}}\)/\({\mathcal{PT}}\) symmetry and the strong SOC originating from the Te atoms, so that it has recently garnered widespread attention. Early studies37,38,39,40,41 indicated that bulk MnTe is a p-type semiconductor and layered in-plane antiferromagnetic ordering with the Néel temperature TN ≈ 310K. Recently, numerous interesting electronic, magnetic and transport phenomena have been found in MnTe, including large spin splitting12,42,43,44,45, lifting of Kramers spin degeneracy3,44,46,47, the controllable magnetic anisotropy42,48, large anisotropic magnetoresistance and planer Hall effect3,49,50,51,52, and intrinsic anomalous Hall effect12,17. These diverse properties of MnTe have attracted significant attention in both fundamental physics and device applications. However, the connection between these spintronic phenomena and the physical mechanism is unclear. The main reason is that in the Brillouin zone of the hexagonal α-MnTe, the valence bands at the Γ and A point display quite distinct behaviors and are both very close to the valence band maximum or the Fermi level3,53. Therefore, the transport properties, mainly determined by the electrons near the Fermi level, can be completely different under different conditions.

In this article, we systematically analyzed the band structures of α-MnTe near the Fermi level at the Γ point and the A point, respectively, based on the first-principles band structures, analytical tight-binding models, and group theory discussion. The analytical k ⋅ p effective Hamiltonians with SOC at the Γ point and the A point were obtained under two different in-plane Néel vector directions \([11\bar{2}0]\) and \([1\bar{1}00]\) respectively. The derived effective Hamiltonian fits well to the first-principles band structures, and all the independent parameters indicated by the group theory were determined. The strong anisotropic Fermi surfaces at the Γ point, originating from the SOC are distinct with different Néel vector orientations.

Results

First principles band structures

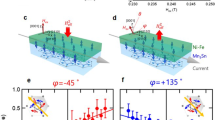

α-MnTe has NiAs-type lattice structure. It is a nonsymmorphic space group \(G={P}_{{6}_{3/mmc}}\) (No. 194). The lattice structure and the Brillouin zone of MnTe are shown in Fig. 1a, b. Both Mn and Te form hexagonal lattices in the plane. A-type collinear antiferromagnetic order is built by Mn. Easy plane anisotropy is suggested experimentally49,50, and the anisotropy in the plane is negligibly small (<0.05 meV per unit cell). Each local moment on the magnetic Mn atom thus can point along \([11\bar{2}0]\) direction (the x direction) (Fig. 1c) or \([1\bar{1}00]\) direction (the y direction) (Fig. 1d) with close probability. Due to the opposite direction of Mn’s magnetization in neighboring layers, two Te atoms, labeled as TeA and TeB, and marked by green and brown, respectively, to be distinguished from each other.

The lattice structure of α-MnTe under a the main view and c, d top views. b the Brillouin zone of MnTe with all high-symmetric k-points. Purple balls represent Mn atoms. Green and yellow balls represent Te atoms in A and B sublattices, respectively. In a, the local magnetic moments on Mn with layered antiferromagnetic ordering lie in the xy-plane. In c, d, the Néel vectors are along x and y directions, respectively.

The band structures for MnTe are shown in Fig. 2. The band gap is about 0.7 eV, indicating the semiconducting behavior. The WF-based Hamiltonian has the same eigenvalues as those obtained by first-principles calculations from 0.5 eV below the Fermi energy to the valence band maximum (VBM). This also indicates that electrons from Mn are away from the Fermi energy, so that only p-orbitals of the Te electrons need to be taken into account when we study spintronic properties. The Γ and A points are both close to VBM. In addition, bands with the Néel vector aligned along the x and y directions have distinct behaviors when SOC is included, shown in Fig. 2b, c. We should separately discuss them in detail.

a Without spin–orbit coupling (SOC), with SOC included and with the Néel vector aligned along b the x direction and c the y direction, respectively. Insert in (a) shows the k-point path in a hexagonal Brillouin zone for the plotting band structure. The Fermi energy, which is the valence band maximum (VBM), is set to zero.

Non-SOC paramagnetic phase

The quotient group G/T of MnTe’s space group G with respect to its translation group T is isomorphic to D6h. It has 24 symmetry operations with the generators \(\{{3}_{0001}^{-}| 0\}\), {20001∣1/2}, {2110∣0}, and \({\mathcal{I}}=\{-1| 0\}\). According to the orbital-resolved band structure plot in Fig. 3a, the valence band around the Γ-point at the Fermi surface is dominated by the single pz orbital. In this paramagnetic state, real spin s is irrelevant, so that sub-Hilbert space is two-dimensional expanded by A/B pseudospin, which is labeled as σ. In this representation, these generators are \(\{{3}_{0001}^{-}| 0\}={\sigma }_{0}\), {20001∣1/2} = σx, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}=-{\sigma }_{x}\), and \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\).

a, b The band structures with Te(5p) orbital component near a the Γ point and b the A point, respectively. The k-point path is shown in c. d Two degenerate states at A point, the symmetrized A–B sublattices with up spin \(\left\vert S\uparrow \right\rangle\) and the anti-symmetrized A–B sublattices with down spin \(\left\vert A\downarrow \right\rangle\). e the band structure in the kxky plane where \(k_{z}=0.45\frac{2\pi }{c}\) (near \(\tilde{A}=(0,0,0.45)\)) in the reciprocal space. Red and blue curves represent spin up and down bands, respectively. f The energy surface for the valence band in kx-ky plane near \(\tilde{A}\) point. The red and blue dots represent the spin up and down, respectively. The units of k-points is Å−1.

Representation is different at the point A = (0, 0, 1/2) which sits right on top of the Γ point. The little group of A is still D6h, so they share the same generators. But the fractal translations in this nonsymmorphic group matters away from the Γ point. Furthermore, the DOS around the A point [Fig. 3a] shows dominance from the px and py orbitals. Using τ to represent the px/py pseudospin, representations of these generators are \(\{{3}_{0001}^{-}| 0\}={\sigma }_{0}(-\frac{1}{2}{\tau }_{0}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i{\tau }_{y})\), {20001∣1/2} = iσyτ0, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}={\sigma }_{x}{\tau }_{z}\), and \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\).

The band structure of the paramagnetic state without spin–orbit coupling can be derived. The full table irreducible representation is in the Table I of the Supplementary Materials. It is, however, worthwhile to discuss the one-dimensional trivial representation A1g: \({D}_{{A}_{1g}}(g)=1\) for any operation g. At the Γ point, other than the trivial representation σ0s0, another irreducible representation is σx. The fourfold degeneracy of \(\left\vert {p}_{zA}\uparrow \right\rangle ,\left\vert {p}_{zB}\uparrow \right\rangle ,\left\vert {p}_{zA}\downarrow \right\rangle ,\left\vert {p}_{zB}\downarrow \right\rangle\) is thus lifted, with each identified by the eigenvalues ±1 of σx. These correspond to the symmetrized (\(\left\vert S\right\rangle\)) and anti-symmetrized (\(\left\vert A\right\rangle\)) states between A and B sublattices; \(\left\vert S(A)\right\rangle ={p}_{zA}\pm {p}_{zB}\). Each band has a twofold spin degeneracy. This is consistent with the DFT calculations. The valence band top at the Γ point is the spin-degenerate anti-bonding states with the symmetrized \(\left\vert S\right\rangle\). In contrast, only the identity matrix σ0τ0s0 expands the trivial irreducible representation at the A point. As a result, all eight bands are degenerate in the paramagnetic state without spin–orbit coupling. Using the full irreducible representation Table I in the Supplementary Materials, one can easily construct the full non-magnetic Hamiltonian of MnTe effective around the Γ and A points, but they are not the main goal here.

Non-SOC AFM phase

The band structure changes when the A-type antiferromagnetic order is introduced. Without spin–orbit coupling, spin and the orbital space can be rotated independently, so that this magnetic state satisfies spin point group 26/2m2m1m. This group is isomorphic to D6h group, but the generators are \(\{{3}_{0001}^{-}| 0\},\,\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\},\,\{{2}_{0001}| 1/2\}{{\mathcal{R}}}_{\pi }\), and \({\mathcal{I}}\). Here \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{\pi }\) is the spin flip operator. At the absence of spin–orbit coupling, one has the liberty of choosing an arbitrary spin quantization axis and the physics is unchanged. For simplicity, let’s use z as the spin quantization axis of Mn layer, then \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{\pi }\) can be either \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{1}={e}^{-i\pi {s}_{x}/2}=-i{s}_{x}\) or \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{2}={e}^{-i\pi {s}_{y}/2}=-i{s}_{y}\). Its irreducible representations are listed in Table 1.

At the Γ point, according to the discussion above, anti-bonding states with eigenstate −1 of σx are split from bonding states; the latter are far from the Fermi level and many other Mn and Te bands are sandwiched in between. We are thus only interested in the minimal Hamiltonian in the two-dimensional sub-Hilbert space expanded by anti-bonding states \(\{\left\vert S\uparrow \right\rangle ,\left\vert S\downarrow \right\rangle \}\). This is consistent with the result obtained by the tight-binding theory in Supplementary Materials. Projection to the corresponding eigenstates, σysz and σzsz, both vanish since they are relevant only in the transition between bonding and anti-bonding states. As a result, only the trivial irreducible representation A1g is relevant, and the Hamiltonian of this valence state is given by

Here, terms c1,2,3 are directly constructed from Table 1. Although immediately next to the Γ point, the DFT results in Fig. 2a can be captured by these three terms, the band structure shows non-quadratic non-monotonous band along the Γ−K/M line away from the Γ point. This is an important feature since the real Fermi surface might cut the valence band top away from the Γ point. Along Γ−K/M line the little group symmetry is much reduced than the Γ point, so the higher-order k corrections cannot rely on the irreducible representation in Table 1. We notice that on the Γ−K−M plane the band exhibits a 6-fold rotational symmetry. Therefore c4 term is included, which is identical to \({k}^{6}{\sin }^{6}\theta \cos 6\phi\) in the spherical coordinate. This is a spinless Hamiltonian, meaning the band is degenerate. This fact is consistent with the band structure in Fig. 2a. Along any direction from the Γ point, bands are always spin degenerate. If altermagnet is narrowly defined as the spin splitting in the absence of spin–orbit coupling, MnTe is not an altermagnet, at least from the transport perspective, once the Γ point is dominant.

At A point, σxτ0sz term of A1g irreducible representation splits the 8-fold degenerate bands into two 4-fold degenerate manifolds, depending on the eigenvalues of this matrix. px and py pseudospins are always degenerate due to the presence of \(\{{3}_{0001}^{-}| 0\}\) operation. The anti-symmetrized A–B sublattices with up spin (\(\left\vert A\uparrow \right\rangle\)) and the symmetrized A–B sublattices with down spin (\(\left\vert S\downarrow \right\rangle\)) are degenerate. On the other hand, symmetrized A–B sublattices with up spin (\(\left\vert S\uparrow \right\rangle\)) and the anti-symmetrized A– B sublattices with down spin (\(\left\vert A\downarrow \right\rangle\)) are also degenerate, but significantly split from the former. The latter is close to the Fermi energy as indicated by the DFT result. Under A-type antiferromagnetic ordering, the mixture of sublattice and spin degrees of freedom is a key feature of bands at the A point due to alternating phases of p-orbitals along \(\left[0001\right]\) direction as shown in Fig. 3d. The symmetrized A–B sublattices within the unit cell is identical to the anti-symmetrized state between Te atoms from two neighboring unit cells along \(\left[0001\right]\). However the spin state of these two equivalent interpretations are opposite due to alternating Mn spins along \(\left[0001\right]\). Let’s use a new pseudospin ω to indicate this two-fold degeneracy between \(\left\vert S\uparrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert A\downarrow \right\rangle\). Although not exactly the real spin operator, it is still a pseudo-vector like the real spin. The minimal Hamiltonian is expanded by four-dimensional matrices ωiτj. Projecting onto this sub-Hilbert space, only terms commuting with σzτ0sz could stay. All other terms enable interband transitions to the cluster of bands far below the valence band top. The resulting effective Hamiltonian is therefore

This effective Hamiltonian is consistent with the DFT result. At A–Γ line, kx = ky = 0 so no splitting is expected. As shown in Fig. 3b, at A–L3 line, kx = kz = 0, the Hamiltonian is reduced to \({H}_{{\rm{non}}-{\rm{SOC}}}^{A-{L}_{3}}={c}_{1}{k}_{y}^{2}-{c}_{3}{k}_{y}^{2}{\tau }_{z}\), so that splitting between px and py is observed. The same is expected along A–H1 line with ky = kz = 0, where \({H}_{{\rm{non}}-{\rm{SOC}}}^{A-{H}_{1}}={c}_{1}{k}_{x}^{2}+{c}_{3}{k}_{x}^{2}{\tau }_{z}\). Along all these high-symmetry lines, spin splitting is absent due to the irrelevance of ω in the Hamiltonian. DFT shows bulk g − wave spin splitting only at low symmetry areas in the Brillouin zone [Fig. 3e, f]. One should note that the spin-dependent second-ordered c4 term is not enough to describe the bulk g − wave spin splitting with three-fold symmetry. Since the spin splitting next to A point does not push the bands above the energy of the A point, apparently, it may not impact transport properties effectively. In addition, SOC and the corresponding in-plane magnetic anisotropy can reduce the symmetry, and the higher-order terms are not as significant. Therefore, we did not further introduce higher-order terms here.

From the tight-binding theory, we analytically derived all the terms permitted by the symmetry constraints in Eqs. (1) and (2) (see Supplementary Materials for details). In the absence of SOC, the valence band maximum at the Γ point is an anti-bonding state between the A and B sublattices and remains spin-degenerate. At the A point, the states become degenerate, corresponding to \(\left\vert S\uparrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert A\downarrow \right\rangle\) states of both px and py orbitals. These findings are all consistent with the symmetry analysis, thereby validating our tight-binding model.

SOC AFM with Néel vector along \([11\bar{2}0]\)

Significant spin splitting in MnTe is actually facilitated by the spin–orbit coupling. When the spin–orbit coupling is turned on, due to the co-rotation of both orbital and spin coordinates, the lattice symmetry is reduced and different antiferromagnetic orderings give distinct band structures. According to the DFT calculation, two antiferromagnetic orders with different in-plane directions of the Néel vectors should be considered. When the Néel lies in \([11\bar{2}0]\) direction (x direction in Fig. 1c, d), the inversion \({\mathcal{I}}\) is still a symmetry, but C3 and C6 symmetries are broken. The little groups at the Γ and A points are both isomorphic to D2h = D2 ⊗ Z2, where \({Z}_{2}=\{E=\{1| 0\},{\mathcal{I}}\}\), and \({D}_{2}=\{\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\},\{{2}_{0001}| 1/2\},\{{2}_{1\bar{1}00}| 1/2\},E=\{1| 0\}\}\). Usually once the magnetic ordering is concerned, the time-reversal operation \({\mathcal{T}}\) would appear in the space group. Interestingly, in the current case, \({\mathcal{T}}\) is not a symmetry operation even in combination with other unitary rotations. So the magnetic space group is the same as the conventional Fedorov space group. Absence of the time-reversal symmetry thus naturally leads to the Hall effect in the absence of the external magnetic field or net magnetization3.

At the Γ point acting on the pz orbitals, the symmetry operations are {20001∣1/2} = σxsz, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}={\sigma }_{x}{s}_{x}\), \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\). While at the A point acting on the px,y orbitals, {20001∣1/2} = iσyτ0sz, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}={\sigma }_{x}{\tau }_{z}{s}_{x}\), and \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\). The character table is given in Table 2. For simplicity, only terms commute with σx and σxτ0sx at the Γ and A points, respectively, are listed. These operations keep the Hilbert space within the subspace given by the degenerate eigenstates required by their trivial irreducible representations.

At the Γ point, all remaining terms keep the anti-bonding state invariant, thus the σ-component can be neglected. Only the spin rotations are relevant. As a result, all allowed terms in addition to the non-SOC effective Hamiltonian are kxkysz, kykzsx, and kxkzsy. They are contributions from the SOC. The tight-binding calculation indicates that only kxkysz term is relevant when kz is tiny. The effective Hamiltonian is thus given by

Here, as suggested in the authors’ earlier work3, a quartic SOC term \(\left({\delta }_{1}{k}_{x}^{3}{k}_{y}+{\delta }_{2}{k}_{y}^{3}{k}_{x}\right){s}_{z}\) is included to enable the non-monotonous band around the Γ point. This result is consistent with the spin-resolved band from DFT calculation. All terms with sz are combined with kxky, so that the valence band around the Γ point is spin polarized along \(+\hat{z}\) direction in the II/IV quadrants and along \(-\hat{z}\) in the I/III quadrants, as shown in Fig. 4b. The degenerate lines with zero are for all the sz terms are two lines kx = 0 and ky = 0. Fig. 4b also shows that the subvalence band has the opposite spin direction. Importantly, the tight-binding calculation shows that γ1 term is a first-order correction in SOC. The large SOC of 0.5 eV in Te thus explains the large spin splitting around the Γ point. The energy maximum is located at four points symmetrically in four quadrants. Considering its p-type semiconductor nature, the Fermi surface formed by the valence band forms four hole pockets, which are mirror symmetric with each other and exhibit strong anisotropic characteristics as well as spin orientation, leading to a wealth of anisotropic transport properties. This result has been well discussed in the authors’ earlier work3.

With the Néel vector aligned along the \([11\bar{2}0]\) (x) direction, The band structure with Te(5p) orbital component a near the Γ point, c along the Γ-A-Γ k-point path, and d near A point. b the energy surface for the top two valence bands in kx-ky plane near the Γ point. The red and blue arrows on each dot represent the +sz and −sz spin directions, respectively. The units of k-points is Å−1.

We employed the conjugate gradient method54 to fit all the coefficients of the effective Hamiltonian obtained from our analysis. DFT bands in an ellipsoidal region of the Brillouin zone around the Γ or A point were chosen for the fitting. Considering that the SOC bands from DFT are obtained through self-consistent field calculations, the non-SOC potentials for different Néel vectors may vary slightly. Therefore, we performed separate fittings for the coefficients of the non-SOC part of the bands for different Néel vectors. In particular, due to the significant impact of SOC on the bands and the presence of important spin-splitting features apart from the Γ point, we adopted the transformation of \({k}_{x}\to \frac{1}{a}\sin {k}_{x}a,{k}_{y}\to \frac{1}{a}\sin {k}_{y}a\) to fit the coefficients of the part of SOC near the Γ point. The fitting parameters were obtained as c1/a2 = 0.0306 eV, c2/c2 = −0.492 eV, c3/a4 = −0.0497 eV, c4/a6 = 0.0047 eV, γ1/a2 = 0.353 eV, δ1/a4 = −0.381 eV, δ2/a4 = 0.0870 eV.

At the A point, the same ω matrices are used to represent the pseudospin of the degenerate basis \(\left\vert S+\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert A-\right\rangle\). Different as the non-SOC AFM case, here the spin space itself is no longer SU(2) invariant. \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) states are determined by the eigenstates of sx instead, i.e., \({s}_{x}\left\vert \pm \right\rangle =\pm \left\vert \pm \right\rangle\). Allowed independent SOC terms are τz, \({k}_{x,y,z}^{2}{\tau }_{z}\), kxkyτx,y, kzτx,yωy, kykzτ0,z, kxτ0,zωx, kxkzτx,y, and kyτx,yωx. The tight-binding calculation indicates the Hamiltonian given by

An interesting term is τz, which opens up a gap at the A point between px and py orbitals. That is a result of the broken C3 symmetry. px and py orbitals are independent. But tight-binding shows that the gap 2γ0 is of the second order of SOC. DFT bands identify this gap as 3 meV, shown in Fig. 4d. It is thus negligibly small. The fitting parameters from the DFT band results were obtained as c1/a2 = −1.089 eV, c2/c2 =−0.120 eV, c3/a2 = −0.615 eV, c4/ac = −0.312 eV, γ0 = 0.0013 eV, γ1/a = −0.110 eV, γ2/a = −0.0161 eV, γ3/c = 0.0663 eV, γ4/a2 = −0.217 eV, γ5/ac = −0.116 eV.

SOC AFM with Néel vector along \([1\bar{1}00]\)

Once the Néel vector is along \([1\bar{1}00]\) direction (or y direction), the SOC terms would be different. The fundamental difference compared to \([11\bar{2}0]\) case is the symmetry group. In this case, the quotient group G/T = M is a magnetic point group. \(M={C}_{2h}\oplus {\mathcal{T}}({D}_{2h}-{C}_{2h})={m}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }m\). It contains {1∣0}, \({\mathcal{I}}\), {20001∣1/2}, {m0001∣1/2}, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}{\mathcal{T}}\), \(\{{2}_{1\bar{1}00}| 1/2\}{\mathcal{T}}\), \(\{{m}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}{\mathcal{T}}\), and \(\{{m}_{1\bar{1}00}| 1/2\}{\mathcal{T}}\). Generators of the groups are \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}{\mathcal{T}}\), {20001∣1/2} and \({\mathcal{I}}\).

In this case, at the Γ point, {20001∣1/2} = σxsz, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}{\mathcal{T}}={\sigma }_{x}{s}_{x}i{s}_{y}K=-{\sigma }_{x}{s}_{z}K\), \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\). ; at the A point, {20001∣1/2} = iσyτ0sz, \(\{{2}_{11\bar{2}0}| 0\}{\mathcal{T}}={\sigma }_{x}{\tau }_{z}{s}_{x}i{s}_{y}K=-{\sigma }_{x}{\tau }_{z}{s}_{z}K\), and \({\mathcal{I}}=-{\sigma }_{x}\). The character table is shown in Table 3. Remarkably, the trivial irreducible representation at the Γ point contains SOC corrections of σ0sz and σxsz. The effective Hamiltonian in the Hilbert space expanded by the anti-bonding state thus contains terms such as \({k}_{x}^{2}{s}_{z}\), \({k}_{y}^{2}{s}_{z}\), \({k}_{z}^{2}{s}_{z}\). Other allowed SOC terms include kykzsy and kxkzsx. The tight-binding model suggests that only \({k}_{x}^{2}{s}_{z}\) and \({k}_{y}^{2}{s}_{z}\) are relevant.

Spins around are thus again polarized along \(\pm \hat{z}\) direction. Tight-binding results suggest that \({\gamma }_{1}=2{\gamma }_{1}^{{\prime} }\) and λ1 = 1, indicating a π/4 rotation of the band structure relating to \({H}_{[11\bar{2}0]}^{\Gamma }\). The energy surfaces shown in Fig. 5b generally match this rotational relationship. However, the \([1\bar{1}00]\) case follows different group symmetry with the \([11\bar{2}0]\) case at the Γ point, so that there is no constraint of the values of \({\gamma }_{1},{\gamma }_{1}^{{\prime} }\) and λ1. Thus, in detail, the fitting parameters based on DFT band results were obtained as c1/a2 = 0.0178 eV, c2/c2 = −0.513 eV, c3/a4 = −0.0480 eV, c4/a6 = 0.0045 eV, \({\gamma }_{1}^{{\prime} }/{a}^{2}=0.153\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }/{a}^{4}=0.0571\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\delta }_{2}^{{\prime} }/{a}^{4}=0.0273\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), λ1 = 1.31 and λ2 = 6.15. λ1 is not 1 and λ2 is not equal to λ1. This indicates that the degenerate lines with zero for all the sz term are not the simple straight lines kx = ±ky, but arcs with mirror symmetries along kx = 0 and ky = 0.

With the Néel vector aligned along the \([1\bar{1}00]\) (y) direction, The band structure with Te(5p) orbital component a near the Γ point, c along the Γ-A-Γ k-point path, and d near A point. b the energy surface for the top two valence bands in kx-ky plane near the Γ point. The red and blue arrows on each dot represent the +sz and −sz spin directions, respectively.

At the A point, \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) states, the spin part for the two basis for ω matrices are now determined by the eigenstates of sy instead, i.e., \({s}_{y}\left\vert \pm \right\rangle =\pm \left\vert \pm \right\rangle\). In contrast to the case at the Γ point, many terms are allowed at the A point, including τy,z, kxkyτx, kykzτ0,y,zωz, kxkzτxωz, kzτ0,y,zωy, kyτxωx, and kxτ0,y,zωx. The tight-binding suggests the following effective Hamiltonian

The fitting parameters from the DFT bands are c1/a2 = −1.089 eV, c2/c2 = −0.132 eV, c3/a2 = −0.615 eV, c4/ac = −0.317 eV, \({\gamma }_{0}^{{\prime} }=0.0013\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\gamma }_{1}^{{\prime} }/a=-0.103\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\gamma }_{2}^{{\prime} }/a=-0.0596\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\gamma }_{3}^{{\prime} }/c=0.0696\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\gamma }_{4}^{{\prime} }/{a}^{2}=0.288\,\,{\rm{eV}}\), \({\gamma }_{5}^{{\prime} }/ac=0.0061\,\,{\rm{eV}}\). The zero-ordered term \({\gamma }_{0}={\gamma }_{0}^{{\prime} }\) is confirmed by both the tight-binding model and the DFT bands. \({\gamma }_{4}\approx {\gamma }_{4}^{{\prime} }\) also indicates that \({H}_{[1\bar{1}00]}^{A}\) generally follows a π/4 rotation of the SOC part of the band structure relating to \({H}_{[11\bar{2}0]}^{A}\). The first-order coefficients \({\gamma }_{2}/{\gamma }_{2}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }_{3}/{\gamma }_{3}^{{\prime} }\) and the second-order one \({\gamma }_{5}/{\gamma }_{5}^{{\prime} }\) determines the anisotropic dispersion away from non-SOC C3 symmetry. In both cases, the magnitudes of these coefficients are at least one-order of magnitude smaller than those of the corresponding ordered coefficients at the Γ point. Both the DFT bands [Fig. 4d and Fig. 5d] and the band fitting results display the tiny anisotropic behavior within several meV.

Discussion

It is very difficult to determine whether the VBM of MnTe is located around the Γ or the A point since their relative energy difference is highly sensitive to external environments, including strain, impurities, temperature, etc. The calculated position of VBM is also sensitive to the exchange-correlation functionals3. Here, we focus on the shape and spin properties of the Fermi surfaces when the VBM is located around the Γ and the A point, respectively, under p-doping.

Once the VBM is located around the Γ, the Fermi surfaces look significantly different when the Néel vector is aligned along the \([11\bar{2}0]\) and \([1\bar{1}00]\) direction, as shown in Fig. 6a, b. In the case of \([11\bar{2}0]\), four VBM k-points are presented according to the energy surfaces shown in Fig. 4b. Under p-doping environment, four hole pockets are symmetrically distributed across the four quadrants, mirroring each other with respect to kx = 0 and ky = 0 [Fig. 6a]. The pockets in I/III quadrants has the opposite spin direction to those in II/IV quadrants, and all four pockets are spin polarized along sz direction. The net magnetization of the Fermi surfaces is zero, but the anisotropic distribution of the Fermi surfaces leads to anisotropic conductivity. The authors’ earlier work3 predicted a giant \({\mathcal{T}}\)-even planer Hall effect with the maximum Hall angle near 30% for this case of Fermi surfaces.

Fermi surfaces in four cases: around the Γ point, Néel vector along (a) \([11\bar{2}0]\) and (b) \([1\bar{1}00]\) respectively; around the A point, Néel vector along (c) \([11\bar{2}0]\) and (d) \([1\bar{1}00]\) respectively. The Fermi energies for all the four cases are 0.01 eV lower than the VBM. Red and blue color represent the spin components. e, f The intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivity for the case of \([11\bar{2}0]\) and \([1\bar{1}00]\), respectively. The energy of VBM is set to zero.

In the case of \([1\bar{1}00]\), the energy maximum occur at two points, which are located on the line ky = 0 and are symmetric with respect to the Γ point, as shown in Fig. 5b. Thus, only two corresponding hole pockets appears symmetrically at +x and −x regions along ky = 0 [Fig. 6b]. Surprisingly, both pockets have the same spin polarization along sz direction so that the valence electron is fully spin polarized even though it is a collinear antiferromagnet. This is consistent with the effective Hamiltonian in Eq. (5). All spin-dependent terms therein are sz related, and the coefficients are even functions of both kx and ky. The anisotropic and spin-polarized Fermi surfaces originate from SOC, and bring about not only the anisotropic conductivity but also the spin-polarized current. Strong spin-transfer torque with strong spin scattering between itinerant electrons polarized along sz given local magnetic moments on Mn along sy are expected. The strong planer Hall response is also expected in terms of the anisotropic Fermi surfaces and would be the primary focus in future work. In both cases, the energy window for the strong anisotropic Fermi surfaces is about 0.08 eV, which is adequate for the p-doping to against thermal fluctuation.

When the VBM is located around A, the valence bands for the two cases of Néel vector appear very similar since the impact from SOC is limited. To this end, in both cases, the Fermi surface generally exhibits a hexagram structure, as shown in Fig. 6. The spin component, following the non-SOC band structure, shows the bulk g-wave spin splitting at low symmetry areas, and the spin direction follows the Néel vector direction, so that the spin properties are dominated by the non-relativistic altermagnetic feature. Figure 6e, f gives the intrinsic anomalous Hall conductivities \({\sigma }_{xy}^{A}\) based on both the WF-based tight-binding model and the effective Hamiltonian. In the case of \([11\bar{2}0]\), \({\sigma }_{xy}^{A}\) is always zero because of the inversion symmetry and isomorphic D2h group at the A point. In the case of \([1\bar{1}00]\), \({\sigma }_{xy}^{A}\) is non-zero when the chemical potential crosses the bands at the A point. Due to the extremely weak in-plane magnetic anisotropy mentioned in the section, the Néel vector of MnTe can be aligned by the applied in-plane magnetic field. The anisotropic anomalous Hall conductivity can thus be verified by modulating the direction of the in-plane magnetic field. However, the detectable energy window for non-zero \({\sigma }_{xy}^{A}\) is only on the order of 0.01 eV, corresponding to the energy window to establish the altermagnetic spin splitting feature in spintronic measurement, so that it is highly susceptible to external environmental factors such as thermal fluctuation and impurities. It is consistent with the experimental measurement of the spontaneous anomalous Hall conductivity of MnTe as only ~0.02 S/cm12.

In summary, we resolved the band structures of α-MnTe near the VBM at the Γ point and the A point. The group representation theory, first-principles calculations, and the tight-binding theory give a consistent effective Hamiltonian around high-symmetry points of MnTe. Compared to direct k ⋅ p theory, our model Hamiltonian is built upon realistic bases. We showed that spin–orbit coupling is essential in generating spin splitting at high-symmetric points and high-symmetric lines. The effective Hamiltonian could be used in future studies of electron, spin, and orbital transports of MnTe and other transition metal chalcogenides with the same structure. The spin-polarized Fermi pockets could give non-trivial magnetoresistance and even possible electron pairing states.

Methods

First principles calculations

The electronic band structures of MnTe were obtained based on density-functional theory (DFT) calculations with projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials55,56, implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation (VASP) package57,58. The generalized gradient approximation in Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof formation59 was used as the exchange-correlation energy. We employed the Hubbard U method in the Liechtenstein implementation60 of U = 4.0 eV, J = 0.9 eV on Mn(3d) orbitals to include the on-site strong-correlation effects of the localized 3d electrons. An energy cutoff of 600 eV was used for the plane-wave expansion throughout the calculations. The Γ-centered 12 × 12 × 8 k-mesh is sampled in the Brillouin zone for self-consistent calculations. The experimental lattice parameters of a = 4.171Å and c = 6.686Å49 are used. The SOC was included when we considered the AFM phase with the Néel vectors along the x and y directions

After we obtained the eigenstates and eigenvalues, a unitary transformation from the plane-wave basis to the localized Wannier function (WF) basis was performed to construct the tight-binding Hamiltonian by using the band disentanglement method61 implemented in the Wannier90 package62. Only Te(5p) orbitals are chosen for the projection.

General group representation theory

To understand all valence bands and facilitate future transport studies, the effective Hamiltonian of MnTe will be constructed using the representation theory of the space group, spin group, and magnetic group. Only Te(5p) orbitals are taken into account. Each unit cell contains two Te atoms. The Hilbert space is thus expanded by the basis of atomic orbitals ϕl from A, B sublattices:

where Rj are Bravais lattice vectors and τα with α = A, B are basis of two sublattices. For MnTe, \({\tau }_{A}=\frac{2}{3}{{\bf{a}}}_{1}+\frac{1}{3}{{\bf{a}}}_{2}-\frac{1}{4}{{\bf{a}}}_{3}\) and \({\tau }_{B}=\frac{1}{3}{{\bf{a}}}_{1}+\frac{2}{3}{{\bf{a}}}_{2}+\frac{1}{4}{{\bf{a}}}_{3}\). Under a generic symmetry operation {g∣τ}, a lattice point from one unit cell could be transferred to another, so that \(\{g| \tau \}{\tau }_{\alpha }=g{\tau }_{\alpha }+\tau ={\tau }_{\beta }+{{\bf{R}}}^{{\prime} }\). To ensure \(\{g| \tau \}\left\vert {\psi }_{\alpha }^{{\bf{k}},l}\right\rangle\) is a linear superposition of \(\left\vert {\psi }_{\alpha }^{{\bf{k}},l}\right\rangle\) with the same k, g must belong to the little group of k, i.e., gk = k + K, where K is a lattice vector of the reciprocal space. It can be shown that \(\{g| \tau \}\left\vert {\psi }_{\alpha }^{{\bf{k}},l}\right\rangle ={{\mathcal{D}}}_{\gamma }{(g)}_{l{l}^{{\prime} }}{e}^{-i{\bf{k}}\cdot {{\bf{R}}}^{{\prime} }}\left\vert {\psi }_{\beta }^{{\bf{k}},{l}^{{\prime} }}\right\rangle\), where \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{\gamma }(g)\) is the irreducible representation γ of g in the atomic basis. Therefore, the representation of {g∣τ} is

where the factor \({e}^{-i{\bf{k}}\cdot {{\bf{R}}}^{{\prime} }}\) is important in the discussion of nonsymmorphic crystals63,64 away from the Γ point.

A Hamiltonian \(H={\sum }_{{\bf{k}}}h({\bf{k}})\left\vert {\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\vert\) must be invariant under a symmetry operator g such that \(\left\langle g{\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\vert h(g{\bf{k}})\left\vert g{\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle =\left\langle {\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\vert h({\bf{k}})\left\vert {\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle\). Given the representation of symmetry group under the basis \(\{\left.{\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle \}\): \(\left\vert g{\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle =D(g)\left\vert {\psi }^{{\bf{k}}}\right\rangle\), the invariance indicates D(g)h(g−1k)D−1(g) = h(k). Due to the group representation homomorphism, only generators of the little group need to be considered to construct the effective Hamiltonian h(k). If both the matrices hi and fi(k)—a polynomial of k- expand the same irreducible representation of the little group, their direct product must contain the trivial irreducible representation satisfied by the Hamiltonian. Therefore, one can construct the effective Hamiltonian \(h({\bf{k}})=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{d}{h}_{d}{f}_{d}({\bf{k}})\), where d is the dimension of the representation.

Once symmetry operations include the time-reversal operation \({\mathcal{T}}\) that flips the crystal momentum, the condition for invariance is different. For a generic symmetry operation \(g={g}_{0}{\mathcal{T}}\), where g0 is the unitary component, its representation of can be written as \(D(g)=D({g}_{0}{\mathcal{T}})K\). Here, D is unitary and K is a complex conjugate. Invariance of the Hamiltonian requires \(D({g}_{0}{\mathcal{T}}){H}^{* }(-{g}_{0}^{-1}{\bf{k}}){D}^{-1}({g}_{0}{\mathcal{T}})=H({\bf{k}})\) instead. Later, we will show that the AFM state with the Néel vector along \([1\bar{1}00]\) is exactly this case, while the Néel vector along \([11\bar{2}0]\) belongs to the simple case in the above paragraph.

Tight-binding theory

The symmetric analysis provides all allowed terms in the effective Hamiltonian. However, some terms might vanish due to accidental degeneracy, and some terms are tiny due to weak spin–orbit coupling perturbation. To confirm the band structure with orbital basis predicted by the symmetry analysis and select relevant terms, a tight-binding Hamiltonian is constructed (see Supplementary Materials for details). The full k-dependent Hamiltonian is

where \({H}_{{\rm{Te-Te}}}^{{\bf{k}}}\) is the hopping between all three p orbitals of two sublattices of Te atoms. Up to third neighbor hopping are taken into account, and the hopping integrals are determined by the Slater-Koster rules65,66. \({H}_{{\rm{Te-Mn}}}^{{\bf{k}}}\) is the nearest neighboring hopping between p–d orbitals. Subjected to the trigonal crystal field symmetry, d-orbitals of Mn are split to three levels with degenerate dxz/dyz orbitals, degenerate \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}/{d}_{xy}\) orbitals, and a non-degenerate z2 orbital. Without loss of symmetry, only \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) is considered in the tight-binding model. Due to the local magnetic moment of Mn, majority and minority spins have different spin-preserving hopping amplitudes, but the Slater-Koster rule for each spin is still respected. In addition, \({H}_{{\rm{Mn-Mn}}}^{{\bf{k}}}\) accounts only for the on-site energy of the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital, and thus the dispersion within the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)-orbital subspace is neglected. HSOC is the on-site SOC of Te atoms.

Integrating over the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) by the Schrieffer-Wolff transformation67,68, an effective Hamiltonian solely in terms of p-electrons can be derived as

Here \(\Delta {H}_{{\rm{Te-Te}}}^{{\bf{k}}(2)}=\frac{{H}_{{\rm{Te-Mn}}}^{{\bf{k}}}{H}_{{\rm{Te-Mn}}}^{{\bf{k}}\dagger }}{{\epsilon }_{p}-{\epsilon }_{d}}\), where εp and εd are the energies of Te p and Mn d levels, respectively. Minimal Hamiltonian at the Γ and A points can be derived by further application of the Schrieffer-Wolff transformation \({H}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{{\bf{k}}}={H}_{0}^{{\bf{k}}}+{V}^{{\bf{k}}}\frac{1}{{\varepsilon }_{0}-{H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}}{V}^{{\bf{k}}\dagger }\), where \({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}\) is the Hamiltonian of the Hilbert space to be integrated out. In the previous transformation \(\Delta {H}_{{\rm{Te-Te}}}^{{\bf{k}}(2)}\) above, \({d}_{{z}^{2}}-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) hopping is neglected so that \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) is dispersionless and \({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}={H}_{{\rm{Mn-Mn}}}^{{\bf{k}}}={\varepsilon }_{d}\). However, now p-orbitals to be integrated out are dispersive, so \({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}\) has a matrix form. Here we write \(\frac{1}{{\varepsilon }_{0}-{H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}}\) as \(\frac{1}{({\varepsilon }_{0}-\Lambda )-({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}-\Lambda )}\) and Taylor expand \(({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}-\Lambda )\), where Λ is the diagonal part of \({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}\). We found that in order to derive an effective Hamiltonian with the correct symmetry, higher-order terms of \(({H}^{{\prime} {\bf{k}}}-\Lambda )\) must be kept. Details of the tight-binding theory can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Šmejkal, L., MacDonald, A. H., Sinova, J., Nakatsuji, S. & Jungwirth, T. Anomalous Hall antiferromagnets. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 482–496 (2022).

Yin, G. et al. Planar Hall effect in antiferromagnetic MnTe thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 106602 (2019).

Šmejkal, L., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Beyond conventional ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism: a phase with nonrelativistic spin and crystal rotation symmetry. Phys. Rev. X 12, 031042 (2022).

Šmejkal, L., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Emerging research landscape of altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. X 12, 040501 (2022).

Yuan, L.-D., Wang, Z., Luo, J.-W., Rashba, E. I. & Zunger, A. Giant momentum-dependent spin splitting in centrosymmetric low-Z antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 102, 014422 (2020).

Yuan, L.-D., Wang, Z., Luo, J.-W. & Zunger, A. Prediction of low-Z collinear and noncollinear antiferromagnetic compounds having momentum-dependent spin splitting even without spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 014409 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Enumeration and representation theory of spin space groups. Phys. Rev. X 14, 031038 (2024).

Xiao, Z., Zhao, J., Li, Y., Shindou, R. & Song, Z.-D. Spin space groups: full classification and applications. Phys. Rev. X 14, 031037 (2024).

Cheong, S.-W. & Huang, F.-T. Altermagnetism classification. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 38 (2025).

Feng, Z. et al. An anomalous Hall effect in altermagnetic ruthenium dioxide. Nat. Electron. 5, 735–743 (2022).

Gonzalez Betancourt, R. et al. Spontaneous anomalous Hall effect arising from an unconventional compensated magnetic phase in a semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 036702 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Emergent zero-field anomalous Hall effect in a reconstructed rutile antiferromagnetic metal. Nat. Commun. 14, 8240 (2023).

Han, L. et al. Electrical 180∘ switching of Néel vector in spin-splitting antiferromagnet. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn0479 (2024).

Reichlova, H. et al. Observation of a spontaneous anomalous Hall response in the Mn5Si3 d-wave altermagnet candidate. Nat. Commun. 15, 4961 (2024).

Šmejkal, L., González-Hernández, R., Jungwirth, T. & Sinova, J. Crystal time-reversal symmetry breaking and spontaneous Hall effect in collinear antiferromagnets. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8809 (2020).

Kluczyk, K. P. et al. Coexistence of anomalous Hall effect and weak magnetization in a nominally collinear antiferromagnet MnTe. Phys. Rev. B 110, 155201 (2024).

González-Hernández, R. et al. Efficient electrical spin splitter based on nonrelativistic collinear antiferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 127701 (2021).

Bose, A. et al. Tilted spin current generated by the collinear antiferromagnet ruthenium dioxide. Nat. Electron. 5, 267–274 (2022).

Bai, H. et al. Observation of spin splitting torque in a collinear antiferromagnet RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 197202 (2022).

Karube, S. et al. Observation of spin-splitter torque in collinear antiferromagnetic RuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 137201 (2022).

Šmejkal, L., Hellenes, A. B., González-Hernández, R., Sinova, J. & Jungwirth, T. Giant and tunneling magnetoresistance in unconventional collinear antiferromagnets with nonrelativistic spin-momentum coupling. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011028 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Terahertz-field-driven magnon upconversion in an antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 20, 788–793 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Terahertz field-induced nonlinear coupling of two magnon modes in an antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 20, 801–806 (2024).

Leenders, R. A., Afanasiev, D., Kimel, A. V. & Mikhaylovskiy, R. V. Canted spin order as a platform for ultrafast conversion of magnons. Nature 630, 335–339 (2024).

Roig, M., Kreisel, A., Yu, Y., Andersen, B. M. & Agterberg, D. F. Minimal models for altermagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 110, 144412 (2024).

Mong, R. S. K., Essin, A. M. & Moore, J. E. Antiferromagnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 81, 245209 (2010).

Wang, J. Antiferromagnetic topological nodal line semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081107 (2017).

Šmejkal, L., Mokrousov, Y., Yan, B. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 242–251 (2018).

Chang, C.-Z., Liu, C.-X. & MacDonald, A. H. Colloquium : Quantum anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 011002 (2023).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Barthem, V., Colin, C., Mayaffre, H., Julien, M.-H. & Givord, D. Revealing the properties of Mn2Au for antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Commun. 4, 2892 (2013).

Bodnar, S. Y. et al. Writing and reading antiferromagnetic Mn2Au by Néel spin-orbit torques and large anisotropic magnetoresistance. Nat. Commun. 9, 348 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. Manipulation of the altermagnetic order in CrSb via crystal symmetry. Nature 638, 645–650 (2025).

Rashba, E. Semiconductors with a loop of extrema. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 201, 4–5 (2015).

Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Phys. Rev. 100, 580–586 (1955).

Adachi, K. Magnetic anisotropy energy in nickel arsenide type crystals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 16, 2187–2206 (1961).

Squire, C. F. Antiferromagnetism in some manganous compounds. Phys. Rev. 56, 922–925 (1939).

Uchida, E., Kondoh, H. & Fukuoka, N. Magnetic and electrical properties of manganese telluride. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 11, 27–32 (1956).

Komatsubara, T., Murakami, M. & Hirahara, E. Magnetic properties of manganese telluride single crystals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 18, 356–364 (1963).

Efrem D’Sa, J. et al. Low-temperature neutron diffraction study of MnTe. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 285, 267–271 (2005).

Faria Junior, P. E. et al. Sensitivity of the MnTe valence band to the orientation of magnetic moments. Phys. Rev. B 107, L100417 (2023).

Osumi, T. et al. Observation of a giant band splitting in altermagnetic MnTe. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115102 (2024).

Hajlaoui, M. et al. Temperature dependence of relativistic valence band splitting induced by an altermagnetic phase transition. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314076 (2024).

Belashchenko, K. Giant strain-induced spin splitting effect in MnTe, a g-wave altermagnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 086701 (2025).

Krempaský, J. et al. Altermagnetic lifting of Kramers spin degeneracy. Nature 626, 517 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Broken Kramers degeneracy in altermagnetic MnTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036702 (2024).

Moseley, D. H. et al. Giant doping response of magnetic anisotropy in MnTe. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 014404 (2022).

Kriegner, D. et al. Multiple-stable anisotropic magnetoresistance memory in antiferromagnetic MnTe. Nat. Commun. 7, 11623 (2016).

Kriegner, D. et al. Magnetic anisotropy in antiferromagnetic hexagonal MnTe. Phys. Rev. B 96, 214418 (2017).

Wang, C. M., Du, Z. Z., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Absence of the anomalous Hall effect in planar Hall experiments. Phys. Rev. B 108, L121301 (2023).

Gonzalez Betancourt, R. D. et al. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in altermagnetic MnTe. npj Spintron. 2, 45 (2024).

Krause, M. & Bechstedt, F. Structural and magnetic properties of MnTe phases from ab initio calculations. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 26, 1963–1972 (2013).

Fletcher, R. Function minimization by conjugate gradients. Comput. J. 7, 149–154 (1964).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes forab initiototal-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: orbital ordering in Mott-Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52, R5467–R5470 (1995).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309 – 2310 (2014).

Wu, H. et al. Nonsymmorphic symmetry-protected band crossings in a square-net metal PtPb4. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 31 (2022).

Rong, H. et al. Realization of practical eightfold fermions and fourfold van Hove singularity in TaCo2Te2. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 29 (2023).

Slater, J. C. & Koster, G. F. Simplified LCAO method for the periodic potential problem. Phys. Rev. 94, 1498–1524 (1954).

Konschuh, S., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Tight-binding theory of the spin-orbit coupling in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 82, 245412 (2010).

Schrieffer, J. R. & Wolff, P. A. Relation between the Anderson and Kondo Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. 149, 491–492 (1966).

Liu, C.-C., Jiang, H. & Yao, Y. Low-energy effective Hamiltonian involving spin-orbit coupling in silicene and two-dimensional germanium and tin. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195430 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. and H.F.H. contributed equally to this work. J.X.Y. and J.Z. conceived the idea. T.T. analyzed the tight-binding model. J.Z. performed a group theory discussion. H.F.H. and J.X.Y. performed DFT calculations, WF-based Hamiltonian, and prepared figures. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takahashi, K., Huang, HF., Yu, JX. et al. Symmetry and minimal Hamiltonian of nonsymmorphic collinear antiferromagnet MnTe. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 70 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00784-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00784-1