Abstract

Recent studies suggest that the tetragonal phase of the Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) bilayer nickelate, La3Ni2O7 or La2PrNi2O7, which is stabilized under high pressures, is responsible for high-temperature superconductivity (HTSC). In this context, realization of the tetragonal phase at ambient pressure could be a rational step to achieve the goal of ambient-pressure HTSC in the nickelate system. By employing the concept of Goldschmidt tolerance factor, we succeed in stabilizing the tetragonal phase by aluminum doping together with post annealing under moderately high oxygen pressure. X-ray and neutron diffractions verify the tetragonal I4/mmm structure for the post-annealed samples La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (0.3 ≤ x ≤ 0.5). The Al-doped samples, including the tetragonal ones, show semiconducting properties, carry localized magnetic moments, and exhibit spin-glass-like behaviors at low temperatures, all of which can be explained in terms of charge carrier localization. Furthermore, high-pressure resistance measurements on post-annealed samples reveal that even a low Al doping (x = 0.05) suppresses superconductivity almost completely. This work gives information about the effect of nonmagnetic impurity on metallicity as well as superconductivity in bilayer nickelates, which would contribute to understanding the superconducting mechanism in RP nickelates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent discovery of high-Tc superconductivity (HTSC) at about 80 K in the pressurized bilayer perovskite nickelate, La3Ni2O7, represents a remarkable advance in the field of superconductivity research1,2,3. Unlike the infinite-layer nickelate superconductor discovered in 20194, where the electronic configuration of nickel is nearly 3d9 (Ni1+), the bilayer nickelate has an electronic configuration of 3d7.5 (Ni2.5+). The apical oxygen site between the NiO2 bilayers is almost fully occupied, in contrast with the absence of apical oxygen in the infinite-layer system. The oxygen occupancy not only greatly alters the Ni valence state, but also gives rise to strong interlayer coupling within the bilayers, the latter of which is widely accepted to be crucial for the emergence of HTSC1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Currently, one of the major challenges in the research of nickelate superconductors is to realize bulk HTSC at ambient pressure, such that in-depth experimental investigations on the HTSC can be carried on. Note that while the pressure-quench protocol has successfully stabilized the high-pressure superconducting phase in Bi0.5Sb1.5Te315, this approach has not yet been replicated in nickelate superconductors16.

The bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 is an n = 2 member of the Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) series17,18,19,20,21, Lan+1NinO3n+1, where n is the number of perovskite LaNiO3 layers in between rocksalt-type LaO layers. At ambient pressure, the NiO6 octahedra in La3Ni2O7 are distorted and rotated, resulting in an orthorhombic structure with space group Amam (No. 63) (this space group is based on a nonstandard setting, such that the c axis retains to be the longest one, consistent with the longest c axis in the tetragonal structure)21. Upon applying pressure, La3Ni2O7 undergoes phase transitions to another orthorhombic structure (Fmmm, No. 69)1 and further to a tetragonal structure (space group I4/mmm, No. 139)22,23. Importantly, the out-of-plane Ni−O−Ni bond angle of those high-pressure stabilized structures turns out to be 180°, which effectively enhances the interlayer coupling. Moreover, a structural transition from Amam directly to I4/mmm at about 11 GPa was observed in La2PrNi2O724, concurrently with the emergence of superconductivity. A similar structural transformation into I4/mmm tetragonal phase accompanying with appearance of bulk superconductivity is also observed in the trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O1025, which further corroborates the close relationship between crystal structure and HTSC. Very recently, it was found that compressively strained bilayer-nickelate thin films, which show superconductivity at ambient pressure26,27,28, also adopt a tetragonal structure27. All the information above stimulates the research towards stabilization of the tetragonal structure, which at least serves as an initial step to ultimately realize ambient-pressure HTSC in bulksamples of the bilayer nickelate.

The concept of Goldschmidt tolerance factor29, defined by \(\tau =\frac{{r}_{{\rm{La}}}+{r}_{{\rm{O}}}}{\sqrt{2}({r}_{{\rm{Ni}}}+{r}_{{\rm{O}}})}\), where τ refers to the ionic radii of the constituent ions, gives a clue to obtain the target tetragonal phase. In the view of crystal chemistry, the tolerance factor basically describes the stability as well as the tendency of lattice distortion in the perovskite-like block layers30. Using the effective ionic radii31, and taking \({r}_{{\rm{Ni}}}^{2.5+}=({r}_{{\rm{Ni}}}^{2+}+{r}_{{\rm{Ni}}}^{3+})/2=0.625\) Å for La3Ni2O7, one obtains τ = 0.916, suggesting that the perovskite-like layers are significantly compressed by the rocksalt LaO layers, which accounts for the orthorhombic distortion at ambient pressure. If the τ value increases towards 1.0 through suitable chemical substitutions, one expects that the tetragonal phase could be stabilized at ambient pressure. Indeed, a tetragonal bilayer RP phase in Sr-Ni-O system was realized through Al doping32,33, and via high-pressure synthesis34, where the τ value is nearly 1.0. The theoretical calculations35 suggest that the Fmmm structure can be stabilized at ambient pressure by replacing the La3+ ion with a larger cation, either Ba2+ or Ac3+. Ac3Ni2O7 is also predicted to crystallize in the tetragonal I4/mmm structure36. Unfortunately, the element Ac is almost unavailable because of its strong radioactivity and, on the other hand, the allowed solubility limit of Ba in La3Ni2O7 is too small to increase the τ value appreciably37,38. Considering the efficiency of Al doping in stabilizing La-Ni-O trilayer structures39 and its substantial doping capacity in related RP phases32,39, partial substitution of Ni sites with smaller cations Al3+ (\({r}_{{\rm{Al}}}^{3+}=0.535\) Å) might be a viable approach. Although the Al-doping definitely induces disorder, it still can serve as a probe to investigate the effect of nonmagnetic disorder on Anderson localization as well as potential superconductivity.

In this paper, we report our successful realization of the tetragonal phase in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ. Single-phase samples were obtained in the Al doping range of 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5. While all the as-prepared samples remain orthorhombic, the orthorhombicity tends to decrease with the Al doping. After post annealing under moderately high oxygen pressure, strikingly, the samples with 0.3 ≤ x ≤ 0.5 finally become tetragonal. The detailed crystal structure of the typical samples of x = 0.4 was determined by X-ray and neutron powder diffractions. Transport and magnetic measurements under ambient pressure demonstrate that Al doping induces strong carrier localization. High-pressure resistance studies reveal a rapid suppression of superconductivity in La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (x = 0.05, 0.1, and 0.4).

Results and discussion

Polycrystalline samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6) were prepared by solid-state reactions with using a sol-gel produced precursor18,24. All the samples with x ≤ 0.5 remain to be monophasic, as checked by powder X-ray diffractions (XRD), yet impurity phases appear for the sample of x = 0.6. This means that the Al solubility limit is about x = 0.5 under current synthesis conditions. The as-prepared monophasic samples were annealed at 500 ∘C under ~10 MPa oxygen atmosphere, the outcome of which is called post-annealed samples. Details of the sample preparation and treatment are provided in Methods. The chemical composition and homogeneity were checked by energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy. The results show homogeneous composition that is almost identical to the nominal stoichiometry within the measurement uncertainty for cations including the dopant Al [Figure S1 in the Supporting Information (SI)].

Figure 1a–c show the XRD results for the as-prepared samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5). All the XRD peaks can be well indexed with the Amam structure21, and no secondary phase is detectable. The lattice parameters are calculated by least-squares fit of the reflections indexed, which are plotted as functions of Al content x in Fig. 1c. One sees that the c axis is reduced significantly by the Al doping, which is attributed to the smaller size of Al3+ ions compared with Ni2.5+ ions. Meanwhile, the a and b axes only change slightly, and they tend to get closer with the Al doping. The orthorhombicity, defined by ϵ = 2(b − a)/(b + a) × 100%, decreases from 1.00% for x = 0 to 0.61% for x = 0.5, which aligns with the increase of the tolerance factor. Nevertheless, our aim for the tetragonal structure is not achieved yet in those as-prepared samples.

Characterization of as-prepared a–c and post-annealed d–f samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (0≤ x ≤0.5) by powder X-ray diffractions. In panel (e), the peaks marked by asterisks are attributed to a new phase formed during the annealing (see the text and SI). Plots (c) and (f) show lattice parameters as functions of Al content x. The error bars are smaller than the symbols.

In order to obtain the target tetragonal phase, we tried to increase the oxygen content by annealing the samples under high oxygen pressure (see Methods for the details). The result is presented in Fig. 1d–f. For the non-doped sample of x = 0, first of all, the intensity of (220) reflection at 2θ ≈ 47.4∘ is obviously reduced [Fig. 1e], and an additional peak nearby (marked with asterisks) appears, indicating formation of a new phase. A similar observation was also reported very recently40. The new phase (here we call it β phase) can be best fitted with a tetragonal I4/mmm unit cell: a = 3.8552(1) Å and c = 20.2120(8) Å, both of which are very close to those of the tetragonal La3Ni2O7 phase reported very recently41,42. The weight fraction of the β phase is 75.4%, as opposed to 24.6% for the remaining α phase. The α phase has the normal orthorhombic bilayer Amam structure, with almost identical lattice parameters of the as-prepared sample (Figure S2 in SI). For the sample of x = 0.1, the two-phase Rietveld analysis yields similar lattice parameters for the α and β phases, yet shows a reversed result (80.5% and 19.5%, respectively) for their weight percentages. The fraction of new phase for x = 0.2 is near the XRD detection limit, say 1–5 wt.%, because only discernibly small signal from the new phase is seen.

For the heavily-doped samples of 0.3 ≤ x ≤ 0.5, interestingly, the original (020) and (200) reflections (on the basis of an orthorhombic lattice) merge into a single peak [(110) reflection in the tetragonal lattice, Fig. 1e], suggesting formation of the target tetragonal structure. Note that this tetragonal phase is different from the β phase mentioned above (see below). Figure 1f displays the lattice parameters as functions of Al doping, which clearly shows the structural evolution from orthorhombic to tetragonal at x ≈ 0.3. The result contrasts with that of the as-prepared samples [Fig. 1c], underscoring the importance of annealing under high oxygen pressure.

To determine the oxygen stoichiometry, we performed thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) measurements on selected representative samples [shown in Figure S3 in SI]. The results demonstrate a clear enhancement in thermal stability with increasing Al doping concentration, as evidenced by reduced weight loss percentages [5.82% (x = 0) to 0.58% (x = 0.4) for as-prepared samples, 5.98% (x = 0) to 0.89% (x = 0.4) for post-annealed samples]. The result also shows that post-annealed samples consistently exhibit higher oxygen content than as-prepared counterparts. For La3Ni1.9Al0.1O7−δ samples, analysis of the weight-loss plateaus corresponding to La3Ni1.9Al0.1O6.4543 yields oxygen contents of about 6.87 (as-prepared) and 7.00 (post-annealed). The improved oxygen content and thermal stability in Al-doped systems suggest that Al incorporation may effectively stabilize the oxygen sublattice during thermal treatment.

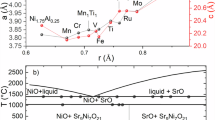

The crystallographic data of the tetragonal phase were obtained by the Rietveld analysis based on the XRD slow-scan data. The XRD refinement profiles for the typical samples of x = 0.4 are displayed in Figure S3, and the resulted data are presented in Table S1, both of which are deposited in the SI. Note that the c-axis value of 20.4620(4) Å of the tetragonal sample of x = 0.4 is even obviously larger than that of the β phase of x = 0. It is also larger than that of the so-called 1313 phase (another polymorph of La3Ni2O7, crystallizing in a hybrid monolayer-trilayer structure44,45,46). To highlight the differences, in Fig. 2b we plot the axial ratios, c/ap, where \({a}_{{\rm{p}}}=\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{{a}^{2}+{b}^{2}}\) in the case of an orthorhombic phase, as functions of c axis for various nominal “327” phases44,45,47,48,49. As is seen, the Al-doped tetragonal or orthorhombic phase has a similar axial ratio with those of the superconducting La3Ni2O7 under high pressures1, and with those of La-site doped La3Ni2O747,48,49. However, the c/ap value of the β phase is the smallest among the series. Thus the non-doped tetragonal β phase might possess substantially different structures which lead to absence of superconductivity even under high pressures41.

a Rietveld refinement profiles of the neutron diffractions for the as-prepared (top) and post-annealed (bottom) samples of La3Ni1.6Al0.4O7−δ. The insets show bond distances and angles in the NiO6 bilayers. b The axial ratios c/ap as functions of c for the bilayer and monolayer-trilayer (1313) nickelates. The simple perovskite unit, \({a}_{{\rm{p}}}=\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{{a}^{2}+{b}^{2}}\), is employed to effectively compare the tetragonal phases with orthorhombic ones.

To more precisely determine the oxygen positions and occupancies, we conducted neutron powder diffraction (NPD) measurements on both the as-prepared and the post-annealed samples of x = 0.4, as shown in Fig. 2a. The refined results, summarized in Table 1, reveal that the oxygen occupancies at the O1 site (i.e., the apical site between NiO2 planes) increases from 0.90(2) in the as-prepared to 0.98(3) in the post-annealed samples. Notably, refinement of the post-annealed sample using a model that includes interstitial oxygen (adopting the configuration observed in La2NiO4+δ where excess oxygen resides between LaO layers50,51) yields a higher Rwp value (8.8%), suggesting absence of interstitial oxygen here. As illustrated in the insets of Fig. 2a, the Ni−O1−Ni bond angle changes expectedly from 167.7(9)∘ (in the Amam phase) to 180∘ (in the I4/mmm phase), expectedly increasing the interlayer coupling. At the same time, the Ni−O3−Ni bond also becomes straight in the tetragonal phase, which enhances the hybridization between Ni-\(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and O-2px/y. Albeit with the Al doping, contrastingly, the Ni−O bond distances in the NiO6 octahedra do not change significantly. Based on the bond distances, the bond valence sums (BVS)52 calculated (without consideration of the Al doping) are 2.55 and 2.62, respectively, for the as-prepared and post-annealed samples, consistent with the increase of oxygen content. Finally, the c/ap value increases a little with post annealing, in sharp contrast with the very low value of the β phase in the post-annealed La3Ni2O7. The realization of the tetragonal phase at ambient pressure here can be basically understood in terms of the concept of Goldschmidt tolerance factor τ. First, τ is increased by the Al doping because of the difference in the ionic radii of Ni2.5+ and Al3+. Second, τ is further increased by the increase of oxygen occupancy at the O1 site. Thus, the Al doping and oxygenation have a synergistic effect on τ, which makes the tetragonal phase finally stabilized.

Electrical resistivity measurements at ambient pressure on La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ demonstrate absence of superconducivity in all samples, as shown in Fig. 3. One sees that the resistivity increases rapidly with Al doping, and the Al-doped samples show semiconducting or insulating behaviors. The result suggests strong carrier localization induced by Al-doping disorder. The low-temperature resistivity basically follows variable-range hopping (VRH) formula ρ(T) = ρ0exp(T0/T)1/D, where D refers to the dimension in the electron hopping [Figure S4 in SI]53. The two-dimensional VRH better fits the data, suggesting that disorder effects are confined to the NiO2 planes. One also note that the resistivity of the post-annealed samples is systematically reduced, which inversely implies that the oxygen vacancy in the as-prepared samples also contributes the carrier localization20. For the as-prepared undoped sample, an anomaly at ~125 K can be detected, similar to the earlier reports in La3Ni2O6.92 polycrystalline sample18,20. The anomaly has been recently identified as the density-wave (DW) transition1,54. This DW-like transition is smeared out at x = 0.1, and becomes indiscernible for x ≥ 0.2. The result indicates that the Al doping destroys the DW order either39. For the post-annealed samples, no signature of DW transition is present even in the undoped parent compound, primarily due to phase transformation into the β phase, similar to the very recent report41.

Figure 4 shows the magnetic susceptibility data measured under a magnetic field of μ0H = 0.1 T for all samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ. The undoped samples exhibit relatively low values of magnetic susceptibility (~0.001 emu/mol) with a weak temperature dependence. At high temperatures above ~100 K, the susceptibility decreases with decreasing temperature, suggesting existence of antiferromagnetic correlations. Upon Al doping, the magnetic susceptibility increases systematically, and the high-temperature χ(T) data for x > 0.1 basically follows the extended Curie-Weiss formula, χ = χ0 + C/(T + θW), where χ0, C, and θW represent the temperature-independent term, the Curie constant, and the paramagnetic Curie-Weiss temperature, respectively. The data fitting in the temperature range of 150–300 K [Fig. 4b, d] yields the three parameters, which are presented in Table S2 in the SI. The χ0 values are all around 0.001 emu/mol, basically identical to the χ value of the undoped samples. The Curie constant increases progressively with Al doping, and the derived effective magnetic moments(μeff) increase from 0.48 (x = 0.2) to 1.01 (x = 0.5) μB/Ni for the as-prepared samples. A similar trend is also observed for the post-annealed samples with x > 0.2. At low temperatures, one sees that the FC and ZFC data bifurcate for Al-doped samples, suggesting freezing of localized spins. Evidenced of the spin freezing is also given by the magnetic hysteresis at the lowest temperature measured (Figure S5 in the SI). While oxygen annealing increases the absolute susceptibility values very slightly, the magnetic parameters remain nearly unchanged, demonstrating that Al doping rather than oxygen content dominates the magnetic modifications, mirroring observations in Zn-doped cuprates where nonmagnetic impurities induce moments independent of oxygen-content variations55,56.

To investigate the potential pressure-induced superconductivity in Al-doped La3Ni2O7−δ, we performed temperature-dependent resistance measurements on the undoped sample La3Ni2O7−δ (pure orthorhombic phase after oxygen-annealing at 400 ∘C) and post-annealed samples (x = 0.05, 0.1, and 0.4) under pressures. As shown in Fig. 5a, the undoped sample displays a superconducting transition at Tc ≈ 80 K, consistent with previous reports1,2,3. The observed broad transition might arise from sample inhomogeneity and/or weak links between crystalline grains. The x = 0.05 sample [Fig. 5b] maintains semiconducting behavior at low pressures but shows a pronounced resistance drop below 12 K at 24.8 GPa. This drop is probably associated with the emergence of a superconducting transition. In contrast, the x = 0.1 sample [Fig. 5c] and tetragonal phase x = 0.4 sample [Figure S7 in SI] keep semiconducting/insulating behavior within measured pressure range and have large resistance values even over 20 GPa, implying stronger carrier localization with increased Al doping. Furthermore, the orthorhombic x = 0.05 sample annealed at the lower temperature of 400 ∘C remains insulating at 24.7 GPa [Figure S8 in SI], likely due to insufficient oxygen content. These results indicate that a low Al substitution at ~2.5% can effectively destroy superconductivity in this system.

Temperature dependence of resistance under pressures for La3Ni2O7−δ a, La3Ni1.95Al0.05O7−δ b, and La3Ni1.9Al0.1O7−δ c. Tc is determined as the interception between two linear extrapolations below and above the superconducting transition. The inset in b shows an enlargement of the R(T) for x = 0.05 sample at 24.8 and 27.9 GPa below 50 K. phases with orthorhombic ones.

Figure 6 plots the ambient-pressure electrical resistivity at 100 K, ρ100K, and the effective magnetic moments derived above as functions of Al content. The ρ100K value increases almost exponentially with the Al doping, independent of the oxygenation by post annealing (although the resistivities are nearly two orders of magnitude reduced) and the crystal-structure transformation. The result indicates that the Al dopant dominates the carrier localization. Remarkably, such a localization can be weakened by the A-site chemical substitution, as suggested from a latest report57. Note that free local moments are absent in the undoped samples, while the Al-doped samples do carry local magnetic moments. The effective magnetic moments originate from Al doping, similar to the case in cuprates55,56,58. As shown in Fig. 6, the calculated values of effective moments, assuming that each Al atom induces a spin-1/2 localized moment, align closely with the experimental ones. This supports the interpretation that Al3+ locally disrupts the magnetic order in the NiO2 planes. The inset of Fig. 6 shows that Tc decreases rapidly as Al doping increases in La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ, similar to the effect of Zn doping in YBa2Cu3−xZnxO7−δ59. Given that nonmagnetic scattering brgaieaks Cooper pairs and significantly suppresses Tc in unconventional superconductors60,61, the dramatic reduction of Tc by a small amount of nonmagnetic impurity provides strong evidence for unconventional superconductivity in La3Ni2O7−δ.

Electrical resistivity at 100 K (left axis) and effective magnetic moments (right axis) as functions of Al doping in La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ. The black dashed lines are guides to the eye, and the dash-dotted line represents the expected effective moments induced by Al doping. The yellow trapezoidal area merely indicates the experimental parameter range (0.3 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) where the I4/mmm tetragonal phase was observed in this study. The inset demonstrates the relationship between Tc and doping content in La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ at ~25 GPa and YBa2Cu3−xZnxO7−δ at ambient pressure59.

In summary, we have successfully realized the tetragonal phase of bilayer nickelate at ambient pressure by Al doping together with post annealing in oxygen atmosphere (\({P}_{{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\approx\) 10 MPa). The stabilization of the tetragonal structure can be basically understood with the concept of Goldschmidt tolerance factor. We also found that the post-annealed undoped sample partially transforms into another tetragonal phase–the β phase. This β phase is significantly different from the Al-doped tetragonal one in the light of the axial ratio c/ap. Note that the c/ap value of the latter is similar to that of the superconducting bilayer nickelate under high pressures. Thus, our work provides an initial step towards the ultimate realization of bulk HTSC at ambient pressure.

The aluminum doping also serves as a probe in the system, which significantly alters the physical properties. Even at a low doping level, the system evolves from a bad metal to a semiconductor, and significantly suppresses pressure-induced superconductivity. The resistivity increases almost exponentially with the Al doping, indicating that the Al doping induces strong disorder. Notably, the Al doping also induces local magnetic moments, a phenomenon reminiscent of nonmagnetic doping effect in cuprate superconductors. It would be worthwhile to dope with an element in proximity to nickel to lower the localization effect in the future.

Methods

Polycrystalline samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.6) were synthesized by solid-state reactions using a sol-gel produced precursor18,24. Stoichiometric mixture of the source materials, La(NO3)3⋅6H2O (99.9% Aladdin), Ni(NO3)2⋅6H2O (99.99% Aladdin), and Al(NO3)3⋅9H2O (99.99% Aladdin), were dissolved in the glycol and deionized water with addition of appropriate amount of citric acid. The mixed solution was continuously stirred in a water bath (90 ∘C) for 4 h, and homogeneous green gel resulted. The gel was slowly heated to 500 ∘C in air, and then further heated to 800 ∘C, holding for 10 h to eliminate organic components. The resulted precursor was ground and pressed into pellets, and the pellets were sintered in air at 1080–1150 ∘C for 50 h, which produces single-phase samples of La3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ. In order to obtain the tetragonal phase, the as-prepared samples were post annealed at 500 ∘C for 30 h in 10 MPa oxygen atmosphere.

Powder XRD data were collected on a PANalytical diffractometer (Empyrean Series 2) with Cu-Kα1 radiation. TGA measurements were accomplished in HQT-3, using a 10% H2/Ar gas flow of 3 mL/min with a 20 ∘C/min rate up to 740 ∘C. The NPD measurements were carried out on the high-resolution neutron diffractometer at the Key Laboratory of Neutron Physics, Institute of Nuclear Physics and Chemistry, China Academy of Engineering Physics. The wavelength of the neutron was λ = 1.8846 Å. The crystal structure was refined by Rietveld analysis using the GSAS-II package62. The chemical composition was determined using EDX spectroscopy on a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-3700N) equipped with Oxford Instruments X-Max spectrometer. Electrical resistivity was measured on a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS-9) using standard four-electrodes method. The magnetic properties were measured on a Quantum Design Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS3). Resistance measurements under pressures were performed in a diamond anvil cell (DAC) using Daphne oil 7373 as the presssure-transmitting medium3, pressure is determined at room temperature using the ruby fluorescence method63.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in polycrystalline La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011040 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269–1273 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624–627 (2019).

Shen, Y., Qin, M. & Zhang, G.-M. Effective bi-layer model hamiltonian and density-matrix renormalization group study for the High-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 127401 (2023).

Lechermann, F. et al. Electronic correlations and superconducting instability in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201121 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Electronic structure, dimer physics, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic tendencies in the bilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L180510 (2023).

Yang, Y., Zhang, G. & Zhang, F. Interlayer valence bonds and two-component theory for high-Tc superconductivity of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201108 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. s±-wave pairing and the destructive role of apical-oxygen deficiencies in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 236002 (2023).

Sakakibara, H., Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Possible high Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure through manifestation of a nearly half-filled bilayer hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 106002 (2024).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J. J., Stewart, G. R., Hennig, R. G. & Hirschfeld, P. J. Structural transitions, octahedral rotations, and electronic properties of A3Ni2O7 rare-earth nickelates under high pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 38 (2024).

Geisler, B. et al. Optical properties and electronic correlations in La3Ni2O7 bilayer nickelates under high pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 89 (2024).

Lu, C., Pan, Z., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Interlayer-coupling-driven high-temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 146002 (2024).

Qu, X. et al. Bilayer t − J − J⊥ model and magnetically mediated pairing in the pressurized nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036502 (2024).

Deng, L. et al. Creation, stabilization, and investigation at ambient pressure of pressure-induced superconductivity in Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3. PNAS 122, e2423102122 (2025).

Xu, M. et al. Pressure-dependent “insulator-metal-insulator” behavior in Sr-doped La3Ni2O7. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2400078 (2024).

Drennan, J., Tavares, C. & Steele, B. An electron microscope investigation of phases in the system La-Ni-O. Mater. Res. Bull. 17, 621–626 (1982).

Zhang, Z., Greenblatt, M. & Goodenough, J. Synthesis, structure, and properties of the layered perovskite La3Ni2O7−δ. J. Solid State Chem. 108, 402–409 (1994).

Sreedhar, K. et al. Low-temperature electronic properties of the Lan+1NinO3n+1 (n = 2, 3, and ∞) system: Evidence for a crossover from fluctuating-valence to fermi-liquid-like behavior. J. Solid State Chem. 110, 208–215 (1994).

Taniguchi, S. et al. Transport, magnetic and thermal properties of La3Ni2O7−δ. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 64, 1644–1650 (1995).

Ling, C., Argyriou, D., Wu, G. & Neumeier, J. J. Neutron diffraction study of La3Ni2O7: Structural relationships among n = 1, 2, and 3 phases Lan+1NinO3n+1. J. Solid State Chem. 152, 517–525 (2000).

Wang, L. et al. Structure responsible for the superconducting state in La3Ni2O7 at high-pressure and low-temperature conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7506–7514 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Identification of superconductivity in bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 under high pressure up to 100 GPa. Natl. Sci. Rev. nwaf220 (2025).

Wang, N. et al. Bulk high-temperature superconductivity in pressurized tetragonal La2PrNi2O7. Nature 634, 579–584 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Superconductivity in pressurized trilayer La4Ni3O10−δ single crystals. Nature 631, 531–536 (2024).

Ko, E. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935–940 (2025).

Zhou, G. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 K in (La, Pr)3Ni2O7 films. Nature 640, 641–646 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state transport in compressively strained La2PrNi2O7 thin films. Nat. Mater. 24, 1221–1227 (2025).

Goldschmidt, V. M. Die gesetze der krystallochemie. Naturwissenschaften 14, 477–485 (1926).

Li, Z. et al. Stabilizing perovskite structures by tuning tolerance factor: Formation of formamidinium and cesium lead iodide solid-state alloys. Chem. Mater. 28, 284–292 (2016).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic-radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Kharlamova, I. et al. Ruddlesden-popper phases Sr3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ and some doped derivatives: Synthesis, oxygen nonstoichiometry and electrical properties. Solid State Ion. 324, 241–246 (2018).

Yilmaz, H. et al. Realization of a classical ruddlesden popper type bilayer nickelate in Sr3Ni2−xAlxO7−δ with unusual Ni4+. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 92–100 (2024).

Yamane, K. et al. High-pressure synthesis of bilayer nickelate Sr3Ni2O5Cl2 with a tetragonal crystal structure. Acta Cryst. C 81, 259–263 (2025).

Rhodes, L. C. & Wahl, P. Structural routes to stabilize superconducting La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 044801 (2024).

Wu, S. et al. Ac3ni2o7 and La2Aeni2O6F (Ae = Sr, Ba): Benchmark materials for bilayer nickelate superconductivity https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.11713. 2403.11713 (2024).

Zhang, Z. & Greenblatt, M. Synthesis, structure, and physical-properties of La3−xMxNi2O7−δ (M = Ca2+, Sr2+, Ba2+, 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.075). J. Solid State Chem. 111, 141–146 (1994).

Aggarwal, L. & Božović, I. The quest for high-temperature superconductivity in nickelates under ambient pressure. Materials 17, 2546 (2024).

Periyasamy, M. et al. Effect of electron doping on the crystal structure and physical properties of an n = 3 Ruddlesden–Popper compound La4Ni3O10. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 2671–2684 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Damage of bilayer structure in La3Ni2O7−δ induced by high pO2 annealing https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.01501. 2502.01501 (2025).

Shi, M. et al. Prerequisite of superconductivity: SDW rather than tetragonal structure in double-layer La3Ni2O7−x. Nat. Commun. 16, 9141 (2025).

Liu, Q. et al. Emergence of tetragonal phase in oxygen-annealed Co-doped La3Ni2O7+δ. J. Solid State Chem. 351, 125528 (2025).

Ran, G. et al. Is La3Ni2O6.5 a bulk superconducting nickelate? ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 66857–66864 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Polymorphism in the Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate La3Ni2O7: discovery of a hidden phase with distinctive layer stacking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3640–3645 (2024).

Wang, H., Chen, L., Rutherford, A., Zhou, H. & Xie, W. Long-range structural order in a hidden phase of Ruddlesden-Popper bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Inorg. Chem. 63, 5020–5026 (2024).

Puphal, P. et al. Unconventional crystal structure of the high-pressure superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 146002 (2024).

Jiao, K. et al. Enhanced conductivity in Sr doped La3Ni2O7−δ with high-pressure oxygen annealing. Physica C 621, 1354504 (2024).

Feng, J. et al. Unaltered density wave transition and pressure-induced signature of superconductivity in Nd-doped La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, L100507 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Chemical versus physical pressure effects on the structure transition of bilayer nickelates. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 1 (2025).

Rodriguez-Carvajal, J., Fernandez-Diaz, M. & Martinez, J. Neutron diffraction study on structural and magnetic properties of La2NiO4. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 3, 3215 (1991).

Aguadero, A. et al. In situ high temperature neutron powder diffraction study of oxygen-rich La2NiO4+δ in air: correlation with the electrical behaviour. J. Mater. Chem. 16, 3402–3408 (2006).

Brown, I. D. & Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta. Crystollogr. B 41, 244–247 (1985).

Shklovskii, B. I. & Efros, A. L.Electronic properties of doped semiconductors, vol. 45 (Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, 1984).

Liu, Z. et al. Evidence for charge and spin density waves in single crystals of La3Ni2O7 and La3Ni2O6. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 66, 217411 (2023).

Mahajan, A. V., Alloul, H., Collin, G. & Marucco, J. F. 89Y NMR probe of Zn induced local moments in YBa2(Cu1−yZny)3O6+x. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3100–3103 (1994).

Zagoulaev, S., Monod, P. & Jégoudez, J. Magnetic and transport properties of Zn-doped YBa2Cu3O7 in the normal state. Phys. Rev. B 52, 10474–10487 (1995).

Yilmaz, H. et al. Floating zone growth of large tetragonal Ruddlesden-Popper bilayer nickelate YySr3-yNi2-xAlxO7 single crystal. Commun. Phys 8, 408 (2025).

Ishida, K., Kitaoka, Y., Yamazoe, K., Asayama, K. & Yamada, Y. Al NMR probe of local moments induced by an Al impurity in High-Tc cuprate La1.85Sr0.15CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 531–534 (1996).

Tarascon, J. et al. Structural and physical properties of the metal (M) substituted YBa2Cu3−xMxO7 perovskite. Phys. Rev. B 37, 7458 (1988).

Anderson, P. W. Theory of dirty superconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 11, 26–30 (1959).

Millis, A., Sachdev, S. & Varma, C. Inelastic scattering and pair breaking in anisotropic and isotropic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 37, 4975 (1988).

Toby, B. H. & Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS-II: the genesis of a modern open-source all purpose crystallography software package. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 46, 544–549 (2013).

Mao, H., Xu, J. & Bell, P. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank Wu-Zhang Yang and Zhi Ren for their help in the electrical resistivity measurement. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12494593, 12494592 and 12034017), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1403202, 2022YFA1402200 and 2023YFA1406101) and the CAS Superconducting Research Project under Grant No. [SCZX-0101].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H.C. designed the project; J.Y.L. synthesized the materials and measured transport and magnetic properties; K.X.Y. and Y.N.Z. conducted the high-pressure resistance measurements; H.L. and B.J.L. measured the NPD data; J.X.L. measured the TGA data; J.Y.L. and Y.Q.L. carried out the structural characterizations (XRD and NPD) and performed data analysis with the support of G.H.C., H.Q.Y., K.X.Y., X.Y.Z., J.X.L. and Y.N.Z.; G.H.C., J.Y.L., and Y.Q.L. wrote the paper with inputs from all coauthors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, JY., Lin, YQ., Ye, KX. et al. Stabilization of Tetragonal Phase and Aluminum-Doping Effect in a Bilayer Nickelate. npj Quantum Mater. 11, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00830-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00830-y