Abstract

Superconductivity in La4Ni3O10 has been reported to emerge upon suppression of intertwined spin and charge density wave (SDW/CDW) order, suggesting a possible connection to the pairing mechanism. Here we report a systematic investigation of La4 Ni3−xCux O10+δ (\(0\le x\le 0.7\)), focusing on the evolution of the SDW/CDW order as a function of chemical substitution. Temperature-dependent resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and Hall effect measurements reveal a linear suppression of density wave transition temperature Tdw and a concurrent enhancement of hole concentration with increasing Cu content. At higher substitution levels (\(x > 0.15\)), the transition induced anomaly in the resistivity becomes undetectable while a magnetic signature persists, indicating a partial decoupling of spin and charge components and the possible survival of short-range spin correlations. The absence of superconductivity across the substitution series highlights the importance of additional factors in stabilizing the superconducting state in pressurized La4Ni3O10.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) nickelates (An+1BnO3n+1, where n ≠ 0, ∞) have drawn considerable interest due to their complex electronic, magnetic, and structural behavior, particularly after the reports of high-pressure superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 and La4Ni3O101,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In La4Ni3O10 layered nickelate, the existence of intertwined spin-density wave (SDW) and charge-density wave (CDW) orders have been evidenced by kinks in resistivity and magnetic susceptibility measurements, as well as incommensurate charge/spin superlattice structures using single crystal x-ray and neutron diffraction16,17. A similar coupling of charge and spin modulations has been observed in cuprates and other layered nickelates, where the periodicity of the antiferromagnetic spin order is exactly half that of the charge modulation18,19,20,21,22,23,24. In La4Ni3O10, these density wave phases compete with the emergence of superconductivity under large hydrostatic pressure and are reported to be completely suppressed in the superconducting state. A structural phase transition from monoclinic P21/a to tetragonal I4/mmm occurs right before the emergence of the superconducting phase, with the SDW being a competing order potentially linked to the pairing mechanism2,11.

Although high-pressure studies have played a central role in uncovering superconductivity in bulk Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates, more recent work has shown that epitaxial strain—arising from substrate mismatch—can also stabilize superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films, albeit with a reduced TC13,25. This builds on the earlier reports of superconductivity in nickelates, which was first observed in infinite-layer Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films26,27,28,29,30,31. Further investigation into the interplay between electronic phases, lattice dynamics, and competing orders in these Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates is essential to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning both their superconductivity and density wave behavior. While thin film studies of La4Ni3O10 have yet to report superconductivity or density wave modulation, and pressure remains to date the only demonstrated method of tuning its electronic phases, we propose here a different strategy. Chemical substitution offers an alternative pathway to manipulate these competing orders. In this work, we investigate the effect of Cu substitution on the suppression of density wave states in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ. By partially substituting Ni with Cu, we observe the suppression of the density wave Tdw as well as the magnitude of the resistive signature. The hole-type carrier concentration increases linearly with Cu content, and plateaus once the density wave is fully suppressed. We observe an increase in carrier density that appears to be caused by the delocalization of charge from the suppression of the density wave order. These results demonstrate that chemical substitution effectively decouples the spin and charge components of the density wave order and drives significant carrier delocalization, offering a new handle for tuning the correlated electronic phases in trilayer nickelates.

Results

Transport and microstructure

Temperature-dependent resistivity measurements of La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ for \(0\le x\le 0.27\) are presented in Fig. 1. The density wave transition temperature, Tdw, is defined by the minimum in the first derivative of resistivity16. For the parent compound La4Ni3O10+δ, shown in Fig. 1a, we observed a pronounced kink at \({T}_{{dw}}\approx 132K\), indicating the onset of the SDW/CDW transition. Below this temperature, resistivity slightly increases, consistent with reduced carrier mobility due to the formation of a charge/spin superlattice. A low-temperature upturn in resistivity is also observed, likely resulting from scattering at polycrystalline grain boundaries, as such features are absent in single-crystal measurements of La4Ni3O10+δ32. As Cu content increases, Tdw systematically shifts to lower temperatures. The magnitude of the transition, reflected in both the kink in \(\rho (T)\) and the inverted peak in \(\frac{d\rho }{{dT}}\), diminishes with increasing Cu substitution and becomes nearly undetectable for \(x\ge 0.15\). For comparison, previous studies on electron-doped La4Ni3-xAlxO10 revealed the opposite trend at low substitution levels, where both the transition temperature and magnitude were enhanced33.

a−f Temperature dependent resistivity of La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ for selected doping levels, measured from 0 to 300 K. The black solid line depicts resistivity, while the orange dashed lines show the first derivative in resistivity with respect to temperature. The density wave transition, Tdw, is marked at the minima of \(\frac{d\rho }{{dT}}\) using a vertical red dotted line. As Cu content increases, Tdw shifts to lower temperature and the magnitude of the resistive anomaly progressively weakens. The width of the transition broadens with Cu substitution as well. At approximately \(x=0.15\), the inverted peak seen previously in the first derivative is nearly fully suppressed.

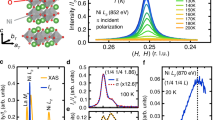

Ambient pressure and temperature scanning transmission electron microscopy of the La4Ni3O10 structure is presented in Fig. 2a. The triple stacking of the perovskite structure can be seen with the out-of-plane vector parallel to the monoclinic b-axis. Figure 2b depicts the lattice parameters versus Cu substitution: a (left axis) and b, c (right axis). Symbols are refined values and dashed lines are linear fits, revealing a monotonic increase of a with x and no variation in b and c. Figure 2c displays the Ni-O-Ni bond angle as a function of x, which decreases approximately linearly with increasing Cu content. The lattice constants and Ni-O-Ni angles were obtained from Rietveld refinements of powder X-ray data. Figure 2d shows the hole concentration determined by Hall measurements (depicted in Figure S1, see the Supplemental Material34) as a function of Cu substitution, revealing a linear increase in carrier density at low x that plateaus for higher x. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), shown in Fig. S2 for x = 0, was used to determine the oxygen content in La4Ni3−xCuxO10+δ; all samples annealed under high oxygen pressure exhibit excess oxygen in Fig. 2d. A gradual increase in δ with increasing Cu content is observed, and for comparison the carrier density expected from δ assuming full ionization is also plotted. However, the delocalization of charge carriers due to suppression of spin- and charge-density wave (SDW/CDW) order cannot be excluded as an additional factor contributing to the enhanced carrier density.

a A high angle annular dark field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy image of an undoped La4Ni3O10+δ polycrystalline sample is shown alongside the monoclinic phase of La4Ni3O10 in the ac-plane. b Lattice parameters versus Cu content: a (left axis, black) and b, c (right axis, orange/brown). Symbols are refined values; dashed lines are linear fits. Colored horizontal arrows indicate the corresponding axes. c Ni-O-Ni bond angle as a function of x; symbols are refined values and the dashed line is a linear fit showing a monotonic decrease with doping. d Carrier concentration n from Hall measurements at 1.8 K (green circles) compared with the value expected from oxygen non-stoichiometry assuming full ionization of excess oxygen (red squares). Blue diamonds show δ from TGA. Dotted lines are linear guides; the green annotations highlight the initial increase of n (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.36) and the subsequent plateau at higher x.

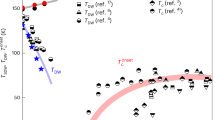

Magnetism and x-T phase diagram across Cu doping

Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out for La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ and are shown in Fig. 3. For the undoped La4Ni3O10+δ, a subtle kink in \(\chi (T)\) is observed near the same temperature as the resistive anomaly, consistent with the onset of the spin-density wave order. As Cu substitution increases, the anomaly gradually shifts to lower temperatures, mirroring the trend observed in the resistivity measurements, and is indicative of a progressive suppression of magnetic order. However, even at higher Cu concentration \(x\ge 0.15\), the anomaly in \(\chi (T)\) remains discernible as its resistive counterpart becomes weak or absent. For \(x > 0.3\), the anomaly disappears, such that no kink can be observed in the susceptibility. The evolution of \(\chi (T)\) thus corroborates the resistivity and supports the interpretation of substitution induced suppression of the SDW order. Figure 4 summarizes the evolution of the density wave transition temperature, Tdw, with respect to Cu content in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ, based on resistivity and magnetic susceptibility measurements, and includes carrier concentration with respect to x. The phase diagram reveals a near linear suppression of Tdw with increasing Cu substitution, with transition temperature values in agreement for both transport and magnetic measurements, confirming that both anomalies originate from a common spin-density wave transition. The onset of the plateau in the carrier concentration coincides with the complete suppression of the density wave transition at \(x\approx 0.3\).

a−f Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility (\(\chi\)) for La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ is shown in solid blue lines. The orange dashed lines represent the temperature-dependent first derivative of the magnetic susceptibility. The density wave transition, extracted from the first derivative, is indicated by the vertical blue dotted lines. The suppression of the transition with increasing Cu content closely mirrors the trend observed in resistivity measurements, however, the transition signature persists for \(x > 0.15\), and the width of the transition doesn’t broaden with Cu substitution, unlike in the resistivity. For \(x > 0.3\), the transition is fully suppressed and no kink is observed in the magnetic susceptibility, as \(\chi\) becomes largely paramagnetic.

Phase diagram of La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ showing the evolution of the density wave transition temperature (Tdw) as a function of Cu content. Blue square markers correspond to values extracted from resistivity data, and orange circle markers from magnetic susceptibility. The resistive transition temperature decreases linearly with Cu substitution and vanishes near x ≈ 0.20, indicating the complete suppression of long-range spin-density wave order, whereas the magnetic transition isn’t fully suppressed until \(x\approx 0.3\). The linear fit shown has a slope of -13.8 K per 1% Cu-substitution, with \({R}^{2}=0.98\). The error bars were taken using the full-width half maximum/minimum of the peak seen in \(\frac{d\rho }{{dT}}\) and \(\frac{d\chi }{{dT}}\). The green star markers represent the carrier concentration, where it increases for \(x < 0.3\) and subsequently plateaus for \(x > 0.3\), which matches the location of the full suppression of density wave phase in the magnetic susceptibility, or when Tdw approaches zero.

Discussion

The suppression of the density wave transition in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ proceeds linearly with Cu substitution, at a rate of approximately −13.8 K per 1% Cu substitution. This behavior is similar to the effects observed in undoped La4Ni3O10 under applied pressure, where the transition is suppressed at a comparable rate of -13K/GPa and vanishes prior to the onset of superconductivity35. Hall effect measurements reveal a significant increase in hole concentration with increasing Cu substitution. While TGA indicates a gradual rise in oxygen nonstoichiometry δ with increasing Cu substitution, the carrier density gain far exceeds what would be expected from oxygen uptake alone, as seen in the theoretical carrier densities in Fig. 2d. Assuming full ionization of excess oxygen, the contribution to hole concentration from δ would yield an increase on the order of 10²⁰ cm⁻³ across the series; however, the measured increase in carrier density reaches 10²² cm⁻³. To isolate the role of oxygen non-stoichiometry, we measured Hall n for two x = 0.06 and two x = 0.12 samples under different δ. For x = 0.06, an as-synthesized specimen under flowing oxygen, La4Ni2.94Cu0.06O9.98 (δ ≈ −0.02), yielded n ≈ 6.7 × 1021 cm-3, whereas a high pressure O2-annealed specimen, La4Ni2.94 Cu0.06O10.085 (δ ≈ +0.085), yielded n ≈ 5.1 × 1021 cm-3. For x = 0.12, La4Ni2.88Cu0.12O9.986 (δ ≈ −0.014) was synthesized under flowing oxygen and yielded n ≈ 8.1 × 1021 cm-3, whereas the high pressure annealed sample, La4Ni2.88 Cu0.12O10.11 (δ ≈ +0.085), yielded n ≈ 8.9 × 1021 cm-3. A simple full ionization estimate predicts Δn ≈ 9 × 1020 cm-3 for the x = 0.06 case, smaller than the measured ∼ 1.7 × 1021 cm-3 and of opposite sign, indicating that δ makes only a subdominant contribution to Hall n at fixed x. For x = 0.12, the change in n with δ (~0.8 × 1021 cm-3) remains small compared to the overall n(x) trend with Cu substitution.

One potential explanation is that the suppression of the SDW/CDW order releases a significant fraction of carriers localized due to strong correlations or trapped in charge ordered states. Similar behavior has been documented in underdoped cuprates, where the nominal hole doping level often overestimates the number of mobile carriers. Hall effect and optical conductivity measurements have consistently shown that the number of mobile carriers is often less than the number of doped holes in stripe-ordered or pseudogapped phases19,36. However, when spin and charge density wave orders are gradually suppressed - via temperature, pressure, magnetic field, or further doping - a linear increase in carrier mobility and concentration is observed. Notably, in YBa2Cu3O6+x, Badoux et al. reported a jump in the Hall number from p to approximately p + 1 near the pseudogap critical point, indicating that the suppression of charge order delocalizes a significant number of previously immobile holes37. Similarly, Cu doping of TiSe2 enhances carrier concentration while suppressing charge density wave as a precursor to the superconducting phase38. These findings underscore that the emergence of enhanced metallicity, and ultimately superconductivity, can stem not only from doped carriers but also from the release of carriers bound in ordered states. This behavior may explain the observations made in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ, where the increase in carrier concentration significantly exceeds what can be explained by oxygen stoichiometry alone, suggesting that the suppression of density wave order plays a central role in carrier delocalization. At high Cu substitution levels (\(x\ge 0.3\)), the carrier concentration begins to plateau, coinciding with the complete suppression of the density wave transition from the disappearance of the magnetic susceptibility anomaly. This suggests that once the spin/charge ordering is fully suppressed, further Cu substitution does not contribute additional mobile carriers. The delocalization of previously localized carriers, associated with the breakdown of SDW/CDW order, reaches its limit in this regime.

A possible reason why superconductivity is not realized in La4 Ni3−xCuxO10+δ is the evolution of the Ni-O-Ni bond angle away from 180°, which theory and experiments on related Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates have linked to enhanced in-plane hybridization and the emergence of superconductivity. In our samples, Rietveld refinements indicate that the Ni-O-Ni angle decreases with Cu substitution, bending further from 180°, which would reduce bandwidth and orbital overlap and therefore disfavor superconducting pairing even as carrier density rises. This contrasts with pressure-tuned systems, where straightening of the Ni-O-Ni linkage has been implicated, highlighting that chemical substitution may push the structural degrees of freedom in the opposite direction. Additional influences may include disorder from Cu on the Ni site and the presence of excess oxygen, either of which can scatter carriers and suppress pairing. Consistent with enhanced elastic scattering, we observe a growth of the residual resistivity and a reduction of RRR with increasing x. To sharpen these structure-property connections, neutron scattering measurements with pair distribution function analysis are underway to more precisely resolve the local Ni-O-Ni angles and to determine the location and coordination environment of the excess oxygen.

A notable divergence occurs at higher Cu concentrations (x > 0.15), where the resistive anomaly associated with the density wave transition is almost completely suppressed, while the kink remains visible in the magnetic susceptibility. This separation suggests a partial decoupling of the spin and charge components of the density wave order at higher Cu concentration. This divergence in CDW and SDW components has been similarly observed in cuprates, for example, in La1.48Nd0.4Sr0.12CuO4, where it was shown that charge density wave sets in a higher temperature than the spin order19,39. These results support the interpretation that the spin-density wave in La4Ni3−x Cux O10+δ may evolve into a robust, disordered or short-range state as the long-range charge order is suppressed, with the magnetic signature remaining detectable. The signature of the charge ordering may be too weak to observe in resistivity measurements, and further temperature dependent TEM studies may depict this ordering in samples with greater Cu-content. At higher Cu-substitution, no superconductivity was observed in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ for \(x\le 0.7\). For \(x\ge 0.7\), La2NiO4 began to form as a secondary phase as seen in Fig. S3 via powder X-ray diffraction, with increasing concentration for greater Cu substitution. Supplementary Fig. S4 shows the energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy data for La4Ni2.25Cu0.75O10+δ, where the addition of the 214 nickelate based on the relative stoichiometry can be seen. This discrepancy between La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ and undoped La4Ni3O10 under pressure underscores the likely importance of the structural phase transition, monoclinic P2₁/a to tetragonal I4/mmm, in stabilizing the superconducting phase, a transformation that is absent in the Cu-substituted series.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Cu substitution in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ systematically suppresses the density wave transition, as evidenced by the progressive weakening and eventual disappearance of resistivity and magnetic susceptibility anomalies associated with the spin-density wave order. The transition temperature Tdw decreases linearly with increasing Cu content, and no signature of a structural phase transition or superconductivity emerges within the substitution range studied. These results underscore the sensitivity of the SDW phase to chemical substitution and suggest that both the suppression of competing orders and a structural transformation may be necessary for superconductivity to emerge in La4Ni3O10. It remains unclear whether the suppression of the SDW/CDW is driven primarily by increased hole concentration or by disorder introduced through random copper substitution, ongoing neutron scattering and cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) experiments will offer direct insight into the evolution of spin and charge ordering, potentially helping to resolve these questions. Future studies combining chemical substitution and pressure could decouple the roles of carrier density and lattice symmetry.

Methods

Sample synthesis

Polycrystalline La4Ni3-xCuxO10-δ was synthesized using the sol-gel method. The starting materials La2O3 (Sigma-Aldrich 99.9%), Cu(NO3)2 · 6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich 99.9%), and Ni(NO3)2 · 6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich 99.9%) were measured in appropriate ratios and dissolved in ~4 M nitric acid with a small amount of citric acid. The mixture was stirred and heated in a 95 °C water bath until a green gel formed. The resulting gels were heated at 250 °C until a fluffy brown powder formed, which was ground and reheated to 800 °C to burn off any remaining organic components. The resulting black powder was pressed into pellets and heated to 1200 °C under 4 bar of O2 for a duration of 24 h. To obtain the correct oxygen stoichiometry, the pellets were annealed at 1100 °C under 36 bar of O2 for 24 h and subsequently furnace cooled.

Powder X-ray diffraction and physical property measurements

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) was carried out using a Bruker D8 Advance Eco diffractometer with LYNXEYE detector and Cu Kα radiation. Pieces of La4Ni3-xCuxO10-δ were ground for several minutes in an agate mortar and pestle to form a fine powder. Hall effect measurements were taken from -3 to +3 T at 1.8 K using a Quantum Design Physical Properties Measurement System (PPMS). Positive-field resistance values were subtracted from negative-field resistance values to remove quadratic terms from the data. DC resistivity measurements between 1.8 K and 300 K were taken using the Quantum Design resistivity module. Electrical contacts were made using silver epoxy and cured at 120 °C. DC magnetic measurements were taken using the Quantum Design vibrating sample magnetometer module. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a TA Instruments TGA 5500, with 95% Ar/5% H2 flow at 2 °C min−1 ramping rate to 800 C. Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy were performed using a Quanta 200 FEG Environmental-SEM.

FIB preparation and TEM/HAADF-STEM imaging

Thin lamellae were prepared by focus ion beam cutting using a Helios NanoLab G3 UC dual-beam focused ion beam and scanning electron microscope (FIB/SEM) system. Sample thinning was accomplished by gently polishing the sample using a 2 kV Ga+ ion beam in order to minimize surface damage caused by the ion beam. Conventional transmission electron microscope (TEM) imaging and atomic resolution high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) STEM imaging were performed on a Titan Cubed Themis 300 double Cs-corrected scanning/transmission electron microscope (S/TEM), operated at 300 kV.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Additional raw data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Superconductivity in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10 under pressure. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021005 (2025).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in polycrystalline La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011040 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269 (2024).

Hou, J. et al. Emergence of high-temperature superconducting phase in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett 40, (2023).

Sakakibara, H. et al. Theoretical analysis on the possibility of superconductivity in the trilayer Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate La 4 Ni 3 O 10 under pressure and its experimental examination: comparison with La3Ni 2 O 7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144511 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Effects of pressure and doping on Ruddlesden-Popper phases Lan+1NinO3n+1. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 185, 147 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigations of key issues on the reproducibility of high- T c superconductivity emerging from compressed La3Ni2O7. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 10, 027801 (2025).

Li, Q. et al. Signature of superconductivity in pressurized La4Ni3O10, Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Superconductivity in pressurized trilayer La4Ni3O10−δ single crystals. Nature 631, 531 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Structural transition, electric transport, and electronic structures in the compressed trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 117403 (2024).

Nagata, H. et al. Pressure-Induced Superconductivity in La4 Ni3 O10+ δ (δ = 0.04 and −0.01). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 095003 (2024).

Ko, E. K. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935 (2025).

Zhou, G. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 K in (La,Pr)3Ni2O7 films. Nature 640, 641 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state transport in compressively strained La2PrNi2O7 thin films. Nat. Mater. 24, 1221 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Intertwined density waves in a metallic nickelate. Nat. Commun. 11, 6003 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Direct visualization of an incommensurate unidirectional charge density wave in La4Ni3O10. Phys. Rev. B 112, 045132 (2025).

Hücker, M. et al. Stripe order in superconducting La2−x Ba x CuO 4 (0.095 ⩽ x ⩽ 0.155. Phys. Rev. B 83, 104506 (2011).

Tranquada, J. M., Sternlieb, B. J., Axe, J. D., Nakamura, Y. & Uchida, S. Evidence for stripe correlations of spins and holes in copper oxide superconductors. Nature 375, 561 (1995).

Tranquada, J. M. et al. Coexistence of, and competition between, superconductivity and charge-stripe order in La1.6−xNd0.4SrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 338 (1997).

Tranquada, J. M. et al. Evidence for unusual superconducting correlations coexisting with stripe order in La1.875Ba0.125CuO 4. Phys. Rev. B 78, 174529 (2008).

Bernal, O. O. et al. Charge-stripe order, antiferromagnetism, and spin dynamics in the cuprate-analog nickelate La 4 Ni 3 O 8. Phys. Rev. B 100, 125142 (2019).

Klingeler, R., Büchner, B., Cheong, S.-W. & Hücker, M. Weak ferromagnetic spin and charge stripe order in La5∕3Sr1∕3NiO4. Phys. Rev. B 72, 104424 (2005).

Kautzsch, L. et al. Incommensurate charge-stripe correlations in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5−xSnx. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 1 (2023).

Osada, M. et al. Strain-tuning for superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films. Commun. Phys. 8, 1 (2025).

Zeng, S. et al. Superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelate La1−x Cax NiO2 thin films. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9927 (2022).

Ding, X. et al. Cuprate-like electronic structures in infinite-layer nickelates with substantial hole dopings, arXiv:2403.07448.

Osada, M. et al. Nickelate superconductivity without rare‐earth magnetism: (La,Sr)NiO2. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104083 (2021).

Sun, W. et al. In situ preparation of superconducting infinite‐layer nickelate thin films with atomically flat surface. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401342 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624 (2019).

Osada, M., Wang, B. Y., Lee, K., Li, D. & Hwang, H. Y. Phase diagram of infinite layer praseodymium nickelate Pr 1−x Sr x NiO 2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 121801 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Flux growth of trilayer La4 Ni3 O10 single crystals at ambient pressure. Cryst. Growth Des. 24, 347 (2024).

Periyasamy, M. et al. Electron doping of the layered nickelate La4Ni3O10 by aluminum substitution: a combined experimental and DFT study. arXiv:2006.12854 (2020).

Supplemental Material at for Hall effect measurements, Thermogravimetric analysis of La4Ni3O10+δ, La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ X-ray diffraction data, Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectra for La4Ni2.25Cu0.75O10+δ.

Khasanov, R. et al. Identical suppression of spin and charge density wave transitions in La4Ni3O10 by pressure. arXiv:2503.04400 (2025).

Padilla, W. J. et al. Constant effective mass across the phase diagram of high-Tc cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 72, 060511 (2005).

Badoux, S. et al. Change of carrier density at the pseudogap critical point of a cuprate superconductor. Nature 531, 210 (2016).

Morosan, E. et al. Superconductivity in CuxTiSe2. Nat. Phys. 2, 544 (2006).

Tranquada, J. M. et al. Neutron-scattering study of stripe-phase order of holes and spins in La1.48Nd0.4Sr0.12CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 54, 7489 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Professor Weiwei Xie for generously sharing her expertise and many insightful discussions on nickelate superconductivity, which sharpened our interpretation of the data and its broader context. We also thank Professor Wenli Bi for her guidance and illuminating conversations on high-pressure superconductivity that informed aspects of our experimental approach and analysis. Their perspectives greatly strengthened this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. synthesized samples, performed x-ray diffraction, electrical and magnetic measurements, and conducted data analysis. D.N. performed thermogravimetric analysis. R.K. performed scanning electron microscopy. G.C. and N.Y. performed transmission electron microscopy. R.C. assisted with data analysis and conceptualization. S.Z. wrote the manuscript. Authors declare that they have no competing interests. All data required to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Ni, D., Ke, R. et al. Suppression of intertwined density waves in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ. npj Quantum Mater. 11, 9 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00838-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-025-00838-4