Abstract

Understanding neurobiological similarities among individuals with psychosis risk symptoms can improve early identification and intervention strategies. We aimed to (i) identify neurobiologically similar psychosis risk subgroups by integrating resting-state functional connectivity and psychosis risk symptom data and (ii) discern discriminating symptom profiles and brain connectivity patterns in the identified sub-groups. Our sample (N = 922) was extracted from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a community group of individuals aged 12–21 years, with fMRI and self-reported psychopathology data. Analyses were conducted separately for youth and early adults. We constructed a two-layer network using pair-wise similarity distances between participants based on resting-state fMRI and psychosis risk symptoms measured with the PRIME screen. We then performed community detection via a multiplex stochastic block model to identify subject clusters. We identified 2 blocks or communities for both the youth (n = 458 and 179) and early adult (n = 173 and 112) groups. Connection parameter estimates of the neuroimaging layer were nearly identical between blocks for both age groups whereas there was significant variation for the symptom layer. Psychopathology symptom and brain system segregation profiles were consistent across age groups. The youth block (n = 458) with higher salience network segregation values had higher mean psychosis risk symptom scores while the early adult block (n = 173) with lower salience network segregation had higher mean psychosis risk symptom scores. By integrating global similarities in brain connectivity and psychosis risk symptoms, we identified distinct subgroups. These groups exhibit different symptom profiles and network segregation in youth and early adults, suggesting variations in developmental paths for psychosis spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The psychosis prodrome, a period that can range from a few weeks to several years, precedes the full onset of schizophrenia1. Several attempts have been made to predict the prodromal period and the prognosis of schizophrenia in high-risk individuals leveraging models incorporating clinical, environmental, or neurocognitive factors2,3,4. In studies that examine the neurobiological underpinnings of schizophrenia, patients with schizophrenia exhibit structural deficits in gray matter regions, with cortical thinning in the frontal, temporal, anterior cingulate, and insular cortices4,5,6. These regions either comprise the salience network, which is involved in the selection of relevant stimuli7, or they play a significant role in facilitating and modulating the network’s activation and connectivity. Structural deficits in these regions have also been observed in individuals with high risk for developing psychosis5,6. However, such deficits are not specific to schizophrenia and can be indicative of other neuropsychiatric disorders5.

Functional neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia have revealed abnormal connectivity patterns within the salience network and its closely associated regions, including those that comprise the default mode network (DMN), frontoparietal network (FPN), and dorsal attention network (DAN5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13). There is evidence that impaired salience network-driven switching between these networks is specifically dysfunctional in high risk (HR) subjects and in prodromal subjects, especially those with attenuated psychotic symptoms10,14,15. In essence, the salience network acts as a “gatekeeper” or “switch” between networks that reflect internally and externally directed attention. Furthermore, anti-correlation between the DMN and the salience network was found to be reduced10,13, which can be indicative of the confusion of internally and externally focused states and the disruption of cognition—a hallmark of psychotic disorders13.

Studies have employed network analyses to investigate psychopathology symptoms16,17,18,19. Graph-based models from such studies consist of nodes that represent psychopathological variables and edges that represent the conditional dependencies between two given variables. These models are effective at specifying symptoms that convey the highest level of clinical information, and they can explain phenomena such as psychiatric comorbidities through the topology of their networks20. However, they do not identify psychiatric subtypes or participant groups that are most at risk of psychopathology.

Robust evidence shows that unsupervised, data-driven methods—especially cluster and latent class analyses—successfully identify reproducible cognitive and symptom subgroups within youth and young adults at clinical high risk (CHR) or in early psychosis, with the most consistent and clinically meaningful distinction observed between “cognitively impaired” and “spared” subtypes that frequently predict functional outcomes but inconsistently predict psychosis conversion21,22,23,24,25,26. Data-driven latent class/profile models focused on symptom-based subgrouping reliably identify emotional vs. motivational deficit patterns, and these are predictive of broader clinical severity and poorer functional outcomes24,25,26. Recent approaches such as multilevel clustering show promise in incorporating both neuroimaging and clinical data to reveal neurobiological subgroups with distinct functional connectivity, gray matter patterns, and symptom correlates, especially within large cohorts27,28.

Community detection is a possible approach for discovering psychiatric subtypes within larger participant groups. In this approach, clustering is performed on network (or graph) structures with nodes that represent individual participants and edges that represent a measure of similarity between a given subject pair. Compared to traditional clustering methods, community detection has not received as much attention in psychiatric literature29. Existing work using community detection has observed that early onset schizophrenia patients lack a default mode intrinsic connectivity network present in age matched controls30, but the small sample size of the study (n = 26) limited the conclusions that could be drawn from their results30,31. Community detection has also shown promise in distinguishing between healthy individuals and those with schizophrenia using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data32, although this method does not allow for the examining of the functional patterns underlying this separation. A study by Taya and colleagues demonstrates that community detection using resting-state fMRI can be effective even when there is no underlying “ground truth” communities to which results can be compared33. We build upon this by evaluating the use of community detection on fMRI data coupled with psychopathology symptoms to elucidate psychosis risk subtypes from data without “ground truths”.

The goal of our study was to identify neurobiologically similar participant groups by integrating data spanning resting state functional connectivity and self-reported psychosis risk symptoms. We further aimed to discern the discriminating symptom profiles and resting state brain connectivity patterns in the communities we identified. To mitigate the sample size constraints encountered in several neuroimaging studies31, we leveraged the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC) as our subject pool; the PNC dataset contains fMRI and psychopathology history data from over 1000 youth participants34.

Methods and materials

Participants

The PNC consists of adolescents and early adults35. Since late adolescence is a critical period in brain development, it is particularly vulnerable for the onset of psychosis and other psychopathology symptoms36,37. To better encapsulate this crucial phase in our subject network, we conducted our analyses separately for youth (ages 12–17) and early adults (ages 18–21). These age groups were established during the collection of the PNC data, as recruitment was conducted differently for each group. Full details of the recruitment procedure are described elsewhere38. We obtained the PNC data from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) after required data access and IRB approvals. This study was exempt approved by UNC IRB #19-1935. The data obtained included information from 9498 participants ages 8–21 who underwent a detailed cognitive and psychopathology assessment35. At enrollment, 1445 of these participants also underwent multimodal neuroimaging34. Our sample (N = 1158) consists of participants ages 12–21, for whom self-reported subject informant data was acquired. Participants ages 8–11 were excluded from our sample as only collateral informant data was acquired35. We partitioned our data into two subsets: a youth sample consisting of 833 participants ages 12–17 and an early adult sample consisting of the remaining 325 participants ages 18–21 years. For our study, we integrated resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI; neuroimaging layer) and positive psychosis risk symptoms (symptom layer) into a multi-layer network to identify communities that were similar.

Demographic and psychopathology symptoms in the PNC were assessed using GOASSESS, a structured computerized instrument developed from a modified version of the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia35. Psychosis risk symptoms were measured using the ordinally structured, 12 item revised PRIME screen39 which measures positive sub-psychosis symptoms on a 7-point scale ranging from “0” (definitely disagree) to “6” (definitely agree). Psychopathology symptom data consists of 115 individual item-level responses for 16 major psychopathology domains; response options were binary: either positive (the participant answered “yes”) or negative (the participant answered “no”).

We excluded participants with missing data for the psychosis risk items, contributing to a final sample size of 922 (637 youth subjects and 285 early adult subjects). This is approximately a 20.4% reduction on our initial sample size. Table 1 presents demographic summary statistics for the final sample, including a breakdown of the youth and early adult subsets. There were 87 participants with psychopathology symptom responses that were reported as “unknown” in our final sample. All unknown responses belonged to one of the 15 domains with binary response values, with none belonging to the psychosis risk symptom items. We assumed each unknown response to be negative; this was shown to have minimal effect on validity40.

Image acquisition and preprocessing

Imaging data for PNC subjects were acquired on a 3 Tesla Siemens TIM Trio whole-body scanner. The image acquisition parameters are described elsewhere34. We preprocessed the neuroimaging data obtained from dbGAP using the CONN toolbox (CONN 21a) running on MATLAB version R2018a41. Structural images underwent segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Preprocessing of the functional images included realignment and unwarping, slice-timing correction, co-registration to structural images, spatial normalization, and motion outlier identification. White matter, cerebrospinal fluid, ART-based scrubbing, six realignment parameters, and the experimental conditions were included as confound regressors. A temporal band-pass filter was used to remove BOLD frequencies below 0.01 Hz or above 0.1 Hz. These bounds are pragmatic defaults to account for scanner drift and physical aliasing while maintaining the brain signal of interest, especially when the repetition time is short42,43,44. Outlier volumes were defined as having greater movement than 0.9 mm or a global signal z-score greater than 3.0. We excluded subjects with more than 20% of volumes removed from subsequent analyses, resulting in a filtered sample of 926 subjects (640 youth and 286 early adults).

Matrix construction

Functional time series were obtained using the Gordon parcellation. The cerebral cortex was divided into 333 functionally defined regions of interest (ROIs), which were then partitioned into multiple resting-state networks45. Weighted FC matrices were constructed for each subject, with edges representing the Fisher z-transformed correlations between the functional time series for each ROI pair.

Multiplex network construction

We constructed a two-layer multiplex network based on pair-wise similarity distances between subjects. The two possible links (connections) between subjects are their similarities in resting-state FC (neuroimaging layer) and responses to the psychosis risk symptom assessment (symptom layer); altered coordination between the salience network and other brain regions may be associated with prodromal symptoms10. The construction of each network, including descriptions of the distance measures used, is detailed in the Supplementary Methods. Separate networks were constructed for the youth and early adult subgroups.

Community detection

We fit a multiplex stochastic block model (SBM) to each multi-layer network. The SBM is a generative model used to describe the structure of random graphs, finding practical use in community detection46. It assumes that nodes in a network can be partitioned into multiple blocks (communities). Unlike other commonly used community detection techniques, such as hierarchical clustering and modularity optimization methods, the SBM provides probability distributions to parameterize the connections (edge weights) between and within each community. A formulation of the multiplex SBM and its estimation process are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analyses

We used the estimateMultiplexSBM function from the sbm R package to fit our models47, and we subsequently analyzed the participant groups obtained from this procedure. All analyses were performed using Python (v3.9.7) and Jupyter Notebooks (v6.4.5) on the Longleaf computer cluster at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The NumPy (v1.22.4), pandas (v1.3.4), SciPy (v1.7.1), scikit-learn (v0.24.2), statsmodels (v0.14.4), and pingouin (v0.5.5) libraries were used for data preprocessing and statistical computation. The Matplotlib (v3.8.1), seaborn (v0.11.2), and Plotly (6.3.0) libraries were used for data visualization.

Brain system segregation

A measure of system segregation, a promising biomarker for psychopathology48,49,50, was computed to examine the level of distinction between different functional networks in the brain51,52,53. Brain system segregation quantifies the degree to which brain regions within the same network are more strongly connected to each other than to regions in other networks. In line with previous implementations51,54, we measured segregation as the difference between mean within-system (\({\bar{Z}}_{w}\)) and mean between-system (\({\bar{Z}}_{b}\)) connectivity divided by mean within-system connectivity:

As such, a high system segregation value indicates that the brain networks each tend to partake in unique and specialized functions53. Conversely, a low system segregation value suggests that the networks are functionally integrated, often partaking in similar tasks or tasks that are interdependent upon another53. We calculated \({\bar{Z}}_{w}\) and \({\bar{Z}}_{b}\) using correlations from participants’ FC matrices. We excluded negative functional connectivity values by setting them to zero, as this has been shown to improve the reliability of graph measures55,56,57,58. Segregation was evaluated for all participants in both age groups. We first computed segregation values for each of the salience network, DMN, FPN, and DAN. These four core networks are closely linked, and abnormal segregation between the salience network and the other three networks is associated with psychosis symptoms10. In our computation, \({\bar{Z}}_{w}\) represents the mean of all pairwise edges (correlations) between nodes (ROIs) of the same network, and \({\bar{Z}}_{b}\) represents the mean of all edges between nodes of the respective network and all other nodes. We later computed pairwise measures between all possible pairings of the four core networks. In this scenario, \({\bar{Z}}_{w}\) represents the mean of all edges within each of the two separate networks, and \({\bar{Z}}_{b}\) represents the mean of all edges connecting nodes between the two target networks.

Psychopathology symptom analyses

Responses to psychosis risk symptom items were averaged for each subject. Cross-validation of the clustering was conducted using psychopathology symptom responses. Since psychiatric comorbidities are common in patients with psychosis/schizophrenia, successful clustering of the participants should yield significant differences in psychopathology symptoms that do not directly measure psychosis risk between blocks59. Supplementary Table S1 presents mean psychopathology symptom scores in the study sample. We examined block-wise means to identify any differences in symptom scores using appropriate statistical tests (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Results

Youth sample

Block demographics

Table 2 presents demographic summary statistics broken down by block. Distributions of race and gender across age groups and blocks are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. Youth Block 1 contains considerably more Black participants than White participants, but this is reversed in Block 2. We found a significant association between gender, age group (youth and early adults), and community (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 15.96, p = 1.15 × 10–3 < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1). Among youth, associations between gender and community (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 3.38, p = 6.61 × 10–2 ≥ 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1) and race and community were not significant (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 3.26, p = 3.53 × 10–1 ≥ 0.05).

Parameter estimates

As presented in Fig. 1C, the within-block parameter estimates (means and variances) for the neuroimaging layer are nearly identical for the two youth blocks (\(\mu \approx 0.30\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\approx 0.04\)). These values are also close to the estimate for the connection parameter between blocks 1 and 2 (\(\mu \approx 0.29\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\approx 0.04\)). In contrast, there is considerably more variation in the symptom layer, suggesting that the clustering by the variational EM algorithm (please see Supplementary Methods) was influenced more by the symptom layer than the neuroimaging layer.

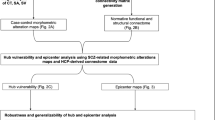

A diagram of the data pipeline is shown in (A). We integrated participant data spanning1 resting state functional connectivity (FC) within the salience brain network and2 responses to the psychosis risk symptom assessment items. Pair-wise similarity distance measures were computed between participants to produce a weighted graph (network) with a neuroimaging layer and a (psychosis risk) symptom layer. A multiplex SBM was fit to the multi-layer network via a variational expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. This process was conducted twice, once for the youth and again for the early adults. The selection process for the optimal number of blocks (Q) is shown in (B). We selected the optimal Q for each subject group (youth and early adults) using the Integrated Completed Likelihood (ICL) criterion. We evaluated values of Q ranging from one to seven and selected the models that converged with the highest ICL. Convergence was not reached when Q was greater than five for the youth and three for the early adults. We found Q : = 2 to be optimal for both the youth and early adults, producing ICLs of –231,381.11 and 40,699.73, respectively. A connection parameter estimates table for the multiplex SBMs is shown in (C). We report the mean and variance of the within- and between-block estimates for each layer in each age group’s model. We also report the log-likelihoods of the models.

Sensitivity analyses

We fit a simple SBM using only the symptom layer (please see Supplementary Methods) and compared estimates for the connection means of the simple SBM and the multiplex SBM. The simple SBM connection means still show considerable variation (Supplementary Fig. S6), indicating that the variation among the symptom layer parameter estimates in the multiplex SBM is not strongly influenced by the joint community detection of the two layers. However, the simple SBM consisted of several more blocks (Q = 29) than the multiplex SBM.

To examine if community detection results from the multiplex SBM are robust to the distance metric used in the construction of the neuroimaging layer, we fit a multiplex SBM to a neuroimaging layer constructed using pairwise Euclidean distances. We found that it produced the same connection parameter estimates for the symptom layer as the original multiplex SBM fit to a neuroimaging layer constructed using pairwise Pearson dissimilarities (Supplementary Fig. S7). The two multiplex SBM models also produced identical block assignments for the youth subjects.

Brain system segregation

We evaluated brain system segregation for four different pairings of functional networks: (pairing 1) the salience network and all other ROIs, (pairing 2) the DMN and all other ROIs, (pairing 3) the FPN and all other ROIs, (pairing 4) the DAN and all other ROIs. All mean segregation values were positive (Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted [BH-adj.] p < 0.05; Fig. 2), indicating that within-network connectivity tended to be stronger than between-network connectivity for the evaluated functional network pairings. Group comparisons of the four measures were significant in both communities (Block 1: F = 31.88, p = 4.39×10–20 < 0.05; Block 2: F = 8.32, p = 1.90 × 10–5 < 0.05; Fig. 2). Segregation for the salience network was the highest (Fig. 2). All pairwise post-hoc comparisons (two-tailed t-tests) involving the salience network were significant (BH-adj. p < 0.05) for Block 1, but only the comparison between the salience network and DAN (SAL-DAN) was significant for Block 2 (Fig. 2C). Permutation tests (please see Supplementary Methods) for these comparisons were not statistically significant at p < 0.05 for any of the segregation measures (Supplementary Table S4).

A visualization of the block-wise distributions of segregation values is shown in (A). Statistically significant comparisons between pairs of segregation measures within a given block are indicated by asterisks (*, **, or ***). A single asterisk (*) denotes a p-value within the interval, (0.05, 0.01]. A double asterisk (**) denotes a p-value within the interval, (0.01, 0.001]. A triple asterisk (***) denotes a p-value less than 0.001. A table with block-wise segregation statistics (means and standard deviations) is shown in (B). A symmetric matrix with post-hoc comparison (two-tailed t-test) results for one-way ANOVAs that assess differences between the four segregation measures is shown in (C). An ANOVA was conducted separately for Block 1 (F = 31.88, p = 4.39 × 10–20) and Block 2 (F = 8.32, p = 1.90 × 10–5) of the youth. Significant pair-wise t-test results (BH-adj. p) are bolded and italicized. These significant pair-wise comparisons are denoted by the asterisks (*, **, or ***) in (A). Significance was determined based on a threshold of 0.05. The Benjamini–Hochberg method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

We further examined segregation values for pairwise groupings of the four core networks. This resulted in comparisons of an additional six network pairings: (pairing 5) the salience network and the DMN, (pairing 6) the salience network and the FPN, (pairing 7) the salience network and the DAN, (pairing 8) the DMN and the FPN, (pairing 9) the DMN and the DAN, and (pairing 10) the FPN and the DAN (Supplementary Fig. S4). These comparisons were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table S4).

Psychopathology symptoms

For the two youth communities, psychopathology symptoms scores were higher for the attention deficit hyperactive domain (ADD), depression (DEP), the generalized anxiety domain (GAD), mania (MAN), the oppositional defiant domain, specific phobias (PHB), and the social anxiety domain (SOC; Fig. 3A). Of these seven domains, four (DEP, GAD, MAN, and SOC) are known to be closely linked with psychosis59. Block 1 had higher values for all symptom measures assessed. The two blocks exhibited the strongest differences in ADD (BH-adj. p = 5.47 × 10–13), MAN (p = 6.54 × 10–11), and the psychosis domain (PSY; BH-adj. p = 4.65 × 10–11), but 14 out of the 15 psychopathology domains assessed showed significant differences (BH-adj. p < 0.05), with the exception of agoraphobia (Supplementary Table S2).

The mean positive (“yes”) response count per subject for each of the 15 psychopathology domains that do not directly measure psychosis risk is shown in (A). The means are scaled to range from 0 to 1 to better visualize the differences between blocks. A red “X” is placed next to the label for the Agoraphobia (AGR) domain, as it was the only psychopathology domain to not show a significant difference in symptom scores between the two blocks. The comparisons for all other psychopathology domains were statistically significant (BH-adj. p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S2). The distributions of the mean response values for the psychosis risk items are shown in (B). As presented in the plot, there is a significant difference in mean psychosis risk response between the two blocks based on permutation tests (p = 2.00 × 10–4 < 0.05; Supplementary Methods). A table displaying the abbreviation, number of item-level responses, and response value type (binary or ordinal) for each psychopathology domain is shown in (C).

Youth in Block 1 (n = 458) had a mean value of 1.2 (SD = 1.1) for psychosis risk symptoms (Fig. 5B), whereas for Block 2 (n = 179) the mean was 0.0 (SD = 0). This difference was significant based on permutation tests (p = 2.00 × 10–4 < 0.05; Supplementary Methods). The simple SBM (fit only to the symptom layer) partially reproduces this block-wise distribution of psychosis risk symptoms, as Block 29 (n = 179) of the simple SBM is identical to Block 2 of the multiplex SBM. However, unlike the multiplex SBM, the simple SBM does not consolidate the remainder of its communities into a single block with a positive mean psychosis risk score (Supplementary Fig. S7). Overall, there is a relatively strong concordance between the block assignments of the simple and multiplex SBMs, as reflected by a significant Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) based on permutation tests (ARI = 0.343; p ≪ 0.001 < 0.05).

Block 1 of the multiplex SBM had higher salience network segregation than Block 2 (Fig. 2) as well as significant post-hoc segregation comparisons involving the salience network (Fig. 2C), suggesting an association between psychosis risk symptoms and abnormal salience network segregation among youth.

Early adult sample

Block demographics

There is a higher proportion of African Americans in Block 1 than Block 2 in the early adult group (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). However, the association between race and community is not significant (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 4.75, p = 1.91 × 10–1 ≥ 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1). Consistent with youth, we did not find a significant association between gender and community among early adults (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 0.74, p = 3.91 × 10–1 ≥ 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1).

Parameter estimates

Similar to our findings within the youth subgroup, all connection parameters for the neuroimaging layer are nearly identical (\(\mu \approx 0.30\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\approx 0.04\); Fig. 1C). The early adult connection parameters are also close to those observed in the youth subgroup, suggesting a lack of change in salience network functional activity between youth and early adulthood. Once more, we found considerably more variation in the mean and variance of the symptom layer edge weights, which was also supported by a sensitivity analysis fitting a simple SBM to only the symptom layer (please see Supplementary Methods). The estimates for the connection means of the simple SBM still show considerable variation (Supplementary Fig. S6) but with several more blocks (Q = 14). We also fit a multiplex SBM to a neuroimaging layer constructed using pairwise Euclidean distances for the early adult subgroup and found that it did not alter the connection parameter estimates for the symptom layer (Supplementary Fig. S7), consistent with the results from the youth subset.

Brain system segregation

Group comparisons of the four segregation measures were significant in both early adult communities (Block 1: F = 2.89, p = 3.49 × 10–2 < 0.05; Block 2: F = 5.65, p = 8.29 × 10–4 < 0.05; Fig. 4). The segregation patterns of the early adult communities closely mirror those of the youth communities: salience network segregation tended to be higher than the segregation values for each of the DMN, FPN, and DAN (Fig. 4). Consistent with the observation among youth, the four segregation measures have positive means for the early adults (BH-adj. p < 0.05; Fig. 4). However, all pairwise post-hoc comparisons (two-tailed t-tests) involving the salience network were not significant (BH-adj. p ≥ 0.05), apart from the comparison between the salience network and DAN in Block 2 (BH-adj. p = 4.96 × 10–2 < 0.05; Fig. 4C). In fact, only three of the 12 post-hoc comparisons were significant for the early adult communities, a departure from the trend observed among youth (Fig. 4C). However, permutation tests of between-community differences in mean brain system segregation were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table S5).

A visualization of the block-wise distributions of segregation values is shown in (A). Statistically significant comparisons between pairs of segregation measures within a given block are indicated by asterisks (*, **, or ***). A single asterisk (*) denotes a p-value within the interval, (0.05, 0.01]. A double asterisk (**) denotes a p-value within the interval, (0.01, 0.001]. A triple asterisk (***) denotes a p-value less than 0.001. A table with block-wise segregation statistics (means and standard deviations) is shown in (B). A symmetric matrix with post-hoc comparison (two-tailed t-test) results for one-way ANOVAs that assess differences between the four segregation measures is shown in (C). An ANOVA was conducted separately for Block 1 (F = 2.89, p = 3.49 × 10–2 < 0.05) and Block 2 (F = 5.65, p = 8.29 × 10–4 < 0.05) of the early adults. Significant pair-wise t-test results (BH-adj. p) are bolded and italicized. These significant pair-wise comparisons are denoted by the asterisks (*, **, or ***) in (A). Significance was determined based on a threshold of 0.05. The Benjamini–Hochberg method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

We also examined between-community differences in mean segregation for the six additional network pairings, as described for the youth. The difference between Blocks 1 and 2 for the salience network and FPN pairing was negative and statistically significant based on permutation testing, though it did not survive multiple comparisons correction (observed difference = –0.06, p = 0.02 < 0.05, BH-adj. p = 0.38 ≥ 0.05). All other network comparisons were not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. S5 & Table S5).

Psychopathology symptoms

The psychopathology symptom profiles of the early adult communities resemble those of the youth communities, with blocks 1 and 2 showing the strongest differences in ADD (BH-adj. p = 2.06 × 10–5), MAN (p = 1.40 × 10–5), and PSY (BH-adj. p = 2.06 × 10–5). All 15 of the psychopathology domains assessed exhibited significant differences between the two blocks (BH-adj. p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S3). As observed among the youth, multiple participants clustered in Block 1 (n = 173) reported psychosis risk symptoms (mean 0.9, SD 0.9; Fig. 5B), whereas participants in Block 2 (n = 112) reported no psychosis risk symptoms (mean 0, SD 0). This difference was statistically significant based on permutation tests (p = 2.00 × 10–4 < 0.05; Supplementary Methods).

The mean positive (“yes”) response count per subject for each of the 15 psychopathology domains that do not directly measure psychosis risk is shown in (A). The means are scaled to range from 0 to 1 to better visualize the differences between blocks. All 15 of the assessed domains showed significant differences in psychopathology symptom scores between the two blocks (BH-adj. p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S3). The distributions of the mean response values for the psychosis risk items are shown in (B). As presented in the plot, there is a significant difference in mean psychosis risk response between the two blocks based on permutation tests (p = 2.00 × 10–4 < 0.05; Supplementary Methods). A table displaying the abbreviation, number of item-level responses, and response value type (binary or ordinal) for each psychopathology domain is shown in (C).

The community detection results from the simple SBM (fit only to the symptom layer) are relatively concordant with the results from the multiplex SBM, reflected by a significant ARI based on permutation tests (ARI = 0.140; p ≪ 0.001 < 0.05). Block 14 (n = 112) of the simple SBM is also identical to Block 2 of the multiplex SBM (Supplementary Fig. S7), but the communities from the simple SBM with positive mean psychosis risk scores are not consolidated. The agreement between the simple and multiplex SBM block assignments—in both the youth and early adult subgroups—further indicates that the clustering was influenced more by the symptom layer than the neuroimaging layer.

Contrary to the pattern among youth, Block 1—which has higher mean psychosis risk symptom scores—has lower salience network segregation than Block 2 (Fig. 4). Additionally, none of the pairwise post-hoc comparisons for Block 1 that involve the salience network are significant (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

To identify neurobiologically similar participant sub-groups, we fit multiplex SBMs to two-layer networks constructed using PNC participants’ psychopathology histories and resting state FC within the salience network. Overall, we find consistent patterns in brain system segregation and responses to psychopathology symptom items between youth aged 12–17 and early adults aged 18–21. Furthermore, for both the youth and early adults, we find stark between-subgroup differences in psychopathology symptom item responses but minimal differences in brain system segregation.

Psychopathology history is more influential than functional brain activity for psychiatric subtyping

Among both the youth and early adults, community detection was driven more by psychopathology history over pair-wise distance measures of resting state functional activity. This imbalance can possibly be attributed to the sources of data used to construct each network layer; fMRI data used to construct the neuroimaging layer is susceptible to several sources of noise: subject motion, instrumentation artifacts such as magnetic field fluctuations, and physiological noise such as variations in heart rate and respiration60,61,62,63. Head motion, for example, induces non-neural fluctuations that inflate or distort apparent correlations between regions. This has been shown to degrade resting state network detectability and reliability of FC maps in clinical cohorts with substantial movement61,62. Cardiorespiratory fluctuations also modulate BOLD signals and can differ systematically between patients and controls; without modeling, these differences have been shown to project onto FC estimates, possibly mimicking or masking disease effects61,63. Optimal quality control methods that aim to mitigate these sources of noise can be specific not just to data quality but also to disease type64,65. These methods can also hamper any detectable signal61,62,63,66, affecting the SNR. A low SNR reduces the reliability of FC estimates, attenuating true disease effects60,67,68. This presents a challenge for the use of functional neuroimaging in clinical subtyping, as the contamination from various sources of noise may deem it too global of a biomarker for identifying individual differences relevant to psychopathology.

Our model incorporated fMRI data in the form of pairwise distance measures comprising a multigraph layer. These distances were either Pearson dissimilarity scores or Euclidean distances computed using resting state functional connectivity from all ROIs associated with the salience network. Our community detection results were mostly invariant to the type of distance measure, but both the Pearson dissimilarity and Euclidean distance measure the linear relationship between two vectors. In addition, we compressed the entirety of a network’s functional activity into a single scalar quantity ranging from zero to one, which may not adequately encapsulate a present signal. It is possible that use of a more sophisticated distance measure or embedding scheme could better capture the fMRI signal. Geodesic distance measures, for example, have found success in improving participant identification from fMRI data69,70. Furthermore, methods that incorporate task-based fMRI or dynamic fMRI—hypothesis-driven acquisition techniques that capture changes in brain interactions over time—have demonstrated accurate individual identification using brain state-specific FC “fingerprints”71,72,73. These approaches can provide an improved SNR over resting-state fMRI and enhance the discriminability of distinct subject groups74, ultimately yielding deeper insights into the neurobiological characteristics of psychosis spectrum disorders.

It is important to note that, although the identified subject communities (blocks) in our study showed little variation in functional brain activity relative to psychosis risk symptoms, incorporating the neuroimaging layer added value to the community detection process. In both age groups, removing the neuroimaging layer resulted in the identification of vastly many blocks. This was in stark contrast to the two blocks identified when both the neuroimaging and symptom layers were included. The results obtained from using both layers align more with findings from previous neuropsychiatric studies that cluster participants, which report two to four subtypes75,76,77,78,79. Therefore, the global signal from functional brain activity potentially anchors a latent structure to biologically plausible constraints, serving as a form of regularization that prevents model overfitting to unmeaningful variations in symptoms.

The stronger influence of psychopathology histories over the clustering has implications for clinical diagnostics. Though modest effect sizes of neuroimaging markers has been suggested as a limiting factor for reliable classification of individual cases80, the joint application of psychopathology symptoms and functional imaging can aid in the discovery of psychosis risk subtypes as proven in other forms of psychopathology like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression81. Functional imaging in conjunction with psychopathology symptoms can thus serve as a pathognomonic “fingerprint” for clinical diagnosis.

Consistency of functional brain activity between adolescents and young adults

Both the youth and early adults have a similar pattern of brain system segregation distributions for the four between-network measures assessed, possibly indicating a lack of change in the specialization of functional brain activity during the transition from adolescence to very early adulthood. It is well documented that brain networks become more segregated during normal adolescent development, more closely resembling the functional activity patterns observed in young adults82,83,84,85. This is particularly the case for networks associated with higher cognitive or emotional functions, such as the salience network, DMN, FPN, and DAN83,84,85. Previous studies involving the PNC have detected increases in both brain system segregation and the modularity of structural networks from youth to early adulthood83,86. However, these studies incorporated participants of all ages (8–22 years) in the analysis without separating the sample into discrete age groups. These studies did not assess differences in sub-populations among participants of a similar age range.

Subgroup identification of the youth and early adult samples underscores differences in functional neurodevelopment between psychosis risk subgroups. In both age groups, Block 1 contains higher mean scores for psychosis risk symptoms, indicating a possible psychosis HR sub-population. When assessing segregation measures for each of the four major networks, we find that—among youth—the HR block exhibits higher salience network and FPN segregation, lower DMN segregation, and similar DAN segregation compared to the other subgroup (Block 2). However, among early adults, the HR block exhibits lower salience network and FPN segregation and higher DMN segregation; the DAN segregation is still similar compared to Block 2. These results suggest different neurodevelopmental trajectories for different subpopulations that are dependent on psychosis risk. As such, not all networks may become more segregated during maturation from adolescence to adulthood; a given network could become more segregated, or—conversely—more integrated, depending on an individual’s psychiatric subtype. Therefore, psychosis risk symptoms may confound the relationship between brain system segregation and the development from adolescence to early adulthood.

The salience network and psychosis

Among youth, the block with higher salience network segregation had higher psychosis risk symptoms. However, among early adults, it was the block with lower salience network segregation that had higher psychosis risk symptoms. These findings suggest that the role of the salience network in psychosis risk may evolve during adolescence and early adulthood. Aberrant interactions between the salience network and other regions are a hallmark of psychosis5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In our youth subgroup, between-community comparisons of brain system segregation for the salience network paired with other networks were not significant. However, in the early adult subgroup, we observed that the comparison for segregation between the salience network and FPN was significant and had the strongest effect size between the two detected communities. Altered functional connectivity of the FPN is known in first episode psychosis and is a trait-specific marker in schizophrenia87, warranting further study of the interaction between these two brain networks. Given the wide range of experiences associated with the pre-psychotic and prodromal stages in psychosis1,88, there may be multiple distinct neurobiological patterns with which abnormal salience network segregation coincides. One such pattern in adolescence may involve heightened salience network segregation, which—when coupled with psychopathology symptoms—may serve as a biomarker for a particular psychosis risk subtype.

Our findings are consistent with a growing body of research indicating that under-segregation of the triple networks—the DMN, salience network, and FPN—is associated with progression into early stages of psychosis during adolescence. In the general population, brain networks tend to become more modular and segregated from adolescence to early adulthood53,89,90,91. However, in CHR converters, the DMN progressively declines in local efficiency92. Moreover, individuals with first episode psychosis exhibit DMN hypoconnectivity and dyscoupling of the salience network with the DMN and FPN10,14,15. These patterns align with our findings, in which the early adult block with lower salience network segregation also had higher psychosis risk symptoms. Additionally, youth with subthreshold symptoms are reported to exhibit “older-like” brain patterns of increased functional specialization90,91,93. This is reflected in our sample, where youth with higher salience network segregation exhibited higher psychosis risk symptoms.

Overall, while further investigation may be required to validate the patterns observed in our results, our study adds to the growing body of evidence for the vital role of the salience network and the differences in neurodevelopmental trajectories in psychosis. Considering the infrequent use of community detection for clinical subtyping in psychiatric literature29, our study showcases the potential of community detection for identification of HR sub-populations.

Limitations and future directions

The limitations of our study primarily arise from our use of the PNC as a subject pool. The PNC is a community sample rather than a clinical sample, so it is unclear whether the clustering and subsequently observed block-wise patterns are generalizable to clinical populations. The presence of increased psychosis risk symptoms alone does not classify the sample as CHR. However, the psychopathology symptom patterns observed within subgroups identified in our study—specifically comorbid symptoms in communities with higher psychosis risk symptoms—mirror those observed within established CHR cohorts such as Youth Mental Health Risk and Resilience Study (YouR-Study21), the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS94,95,96), and the PSYSCAN project97. For example, in these CHR cohorts, the prevalence of depressive disorders is notably high at 41%, which is greater than the prevalence within healthy controls97. In our study, the block identified with elevated psychosis risk symptoms exhibited higher mean scores for depressive symptoms, which were almost twice as high compared to the other block in both the youth (Supplementary Table S2) and early adult subgroups (Supplementary Table S3). Future studies should focus on examining CHR samples to further validate these findings.

We were unable to perform analyses on participants ages 8–11 due to the lack of self-reported symptoms. We also did not have access to psychiatric diagnoses for any of the participants. Access to such data can help refine community detection by discerning HR sub-populations based on positive clinical diagnoses. Without access to these ground truth labels, we used responses to assessment items that did not directly measure psychosis risk for validation of our community detection. This is not an ideal approach, as psychiatric comorbidities are not always present in HR individuals, and it is possible that participants may not have disclosed certain symptoms due to stigma. Lastly, our investigation did not evaluate genetics as a risk factor for psychopathology symptoms. Genomic variables of psychosis risk can potentially be used to construct a third layer in our multiplex network to further delineate biological subtypes of psychosis and psychiatric comorbidities, as psychiatric disorders manifest along genetic continua and share common sources of genetic risk98.

Conclusions

Our study subtyped PNC participants using an approach used sparsely in psychiatric literature. The results offer insights into the joint use of psychopathology history and functional brain activity in the identification of psychiatrically at-risk youth. Our findings also add nuance to the changes in functional activity from adolescence to early adulthood and suggest a significant role for the salience brain network in psychosis. However, direct implications for psychosis itself require further investigation.

Data availability

PNC data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the U.S. National Institutes of Health database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gap through dbGaP accession phs000607.v3.p2. Data from dbGaP are available to qualified researchers upon obtaining relevant data access approvals. The code for the analyses can be accessed via the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/iyeraditya26/psychosis_risk_subgroups_pnc.git.

References

Larson, M. K., Walker, E. F. & Compton, M. T. Early signs, diagnosis and therapeutics of the prodromal phase of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother. 10, 1347–59 (2010).

Montemagni, C., Bellino, S., Bracale, N., Bozzatello, P. & Rocca, P. Models predicting psychosis in patients with high clinical risk: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 11, 223 (2020).

Strobl, E. V., Eack, S. M., Swaminathan, V. & Visweswaran, S. Predicting the risk of psychosis onset: advances and prospects: predicting the risk of psychosis onset. Early Interv. Psychiatry 6, 368–79 (2012).

Glahn, D. C. et al. Meta-analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 774–81 (2008).

Palaniyappan, L. & Liddle, P. F. Does the salience network play a cardinal role in psychosis? An emerging hypothesis of insular dysfunction. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 37, 17–27 (2012).

Chung, Y. & Cannon, T. D. Brain imaging during the transition from psychosis prodrome to schizophrenia. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203, 336–41 (2015).

Menon, V. Salience network. in Brain Mapping. 597–611 (Elsevier, 2015). https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B978012397025100052X.

Bulbul, O., Kurt, E., Ulasoglu-Yildiz, C., Demiralp, T. & Ucok, A. Altered resting state functional connectivity and its correlation with cognitive functions at ultra high risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 321, 111444 (2022).

Del Fabro, L. et al. Functional brain network dysfunctions in subjects at high-risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 128, 90–101 (2021).

Bolton, T. A. W. et al. Triple network model dynamically revisited: lower salience network state switching in pre-psychosis. Front. Physiol. 11, 66 (2020).

Anticevic, A. et al. Amygdala connectivity differs among chronic, early course, and individuals at risk for developing schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1105–16 (2014).

Fryer, S. L. et al. Deficient suppression of default mode regions during working memory in individuals with early psychosis and at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Front. Psychiatry 4, 92 (2013).

Wotruba, D. et al. Aberrant coupling within and across the default mode, task-positive, and salience network in subjects at risk for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1095–104 (2014).

Kim, A. et al. Triple-network dysconnectivity in patients with first-episode psychosis and individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Investig. 19, 1037–45 (2022).

O’Neill, A., Mechelli, A. & Bhattacharyya, S. Dysconnectivity of large-scale functional networks in early psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 579–90 (2019).

Chung, Y. C. et al. Network analysis of trauma in patients with early-stage psychosis. Sci. Rep. 11, 22749 (2021).

Isvoranu, A. M., Borsboom, D., Van Os, J. & Guloksuz, S. A Network approach to environmental impact in psychotic disorder: brief theoretical framework. SCHBUL 42, 870–3 (2016).

Murphy, J., McBride, O., Fried, E. & Shevlin, M. Distress, impairment and the extended psychosis phenotype: a network analysis of psychotic experiences in an us general population sample. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 768–77 (2018).

Schlesselmann, A. J. et al. A network approach to trauma, dissociative symptoms, and psychosis symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 49, 559–68 (2023).

Contreras, A., Nieto, I., Valiente, C., Espinosa, R. & Vazquez, C. The study of psychopathology from the network analysis perspective: a systematic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 88, 71–83 (2019).

Haining, K. et al. Characterising cognitive heterogeneity in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis: a cluster analysis with clinical and functional outcome prediction. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 272, 437–48 (2022).

Healey, K. M. et al. Latent profile analysis and conversion to psychosis: characterizing subgroups to enhance risk prediction. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 286–96 (2018).

Wenzel, J. et al. Cognitive subtypes in recent onset psychosis: distinct neurobiological fingerprints? Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 1475–83 (2021).

Gupta, T., Cowan, H. R., Strauss, G. P., Walker, E. F. & Mittal, V. A. Deconstructing negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis: evidence for volitional and diminished emotionality subgroups that predict clinical presentation and functional outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 47, 54–63 (2021).

Valmaggia, L. R. et al. Negative psychotic symptoms and impaired role functioning predict transition outcomes in the at-risk mental state: a latent class cluster analysis study. Psychol. Med. 43, 2311–25 (2013).

Zhang, T. et al. Clinical subtypes that predict conversion to psychosis: a canonical correlation analysis study from the ShangHai At Risk for Psychosis program. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 54, 482–95 (2020).

Tang, X. et al. Identifying neurobiological heterogeneity in clinical high-risk psychosis: a data-driven biotyping approach using resting-state functional connectivity. Schizophrenia 11, 13 (2025).

Dwyer, D. B. et al. Clinical, brain, and multilevel clustering in early psychosis and affective stages. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 677 (2022).

Agelink Van Rentergem, J. A., Bathelt, J. & Geurts, H. M. Clinical subtyping using community detection: limited utility?. Int. J. Methods Psych. Res. 32, e1951 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. Brain network informed subject community detection in early-onset schizophrenia. Sci. Rep. 4, 5549 (2014).

Szucs, D. & Ioannidis, J. P. Sample size evolution in neuroimaging research: an evaluation of highly-cited studies (1990–2012) and of latest practices (2017–2018) in high-impact journals. NeuroImage 221, 117164 (2020).

Nallusamy, K. & Easwarakumar, K. S. Classifying schizophrenic and controls from fMRI data using graph theoretic framework and community detection. Netw. Model Anal. Health Inf. Bioinform. 12, 19 (2023).

Taya, F., De Souza, J., Thakor, N. V. & Bezerianos, A. Comparison method for community detection on brain networks from neuroimaging data. Appl Netw. Sci. 1, 8 (2016).

Satterthwaite, T. D. et al. Neuroimaging of the Philadelphia neurodevelopmental cohort. NeuroImage 86, 544–53 (2014).

Satterthwaite, T. D. et al. The Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort: a publicly available resource for the study of normal and abnormal brain development in youth. NeuroImage 124, 1115–9 (2016).

Gogtay, N., Vyas, N. S., Testa, R., Wood, S. J. & Pantelis, C. Age of onset of schizophrenia: perspectives from structural neuroimaging studies. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 504–13 (2011).

Leibenluft, E. & Barch, D. M. Adolescent brain development and psychopathology: introduction to the special issue. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 93–5 (2021).

Calkins, M. E. et al. The Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort: constructing a deep phenotyping collaborative. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56, 1356–69 (2015).

Kobayashi, H. et al. A self-reported instrument for prodromal symptoms of psychosis: testing the clinical validity of the PRIME Screen—Revised (PS-R) in a Japanese population. Schizophr. Res. 106, 356–62 (2008).

Rosen, A. F. G., Moore, T. M., Calkins, M. E., Gur, R. C. & Gur, R. E. Effects of skip-logic on the validity of dimensional clinical scores: a simulation study. Psychopathology 52, 358–66 (2019).

Nieto-Castanon, A. Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN (Hilbert Press, 2020). https://www.hilbertpress.org/link-nieto-castanon2020.

Zhang, Y. et al. Shorter TR combined with finer atlas positively modulate topological organization of brain network: a resting state fMRI study. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 34, 174–89 (2023).

Tong, Y., Hocke, L. M. & Frederick, B. B. Low frequency systemic hemodynamic “noise” in resting state BOLD fMRI: characteristics, causes, implications, mitigation strategies, and applications. Front. Neurosci. 13, 787 (2019).

Huotari, N., et al. Sampling rate effects on resting state fMRI metrics. Front. Neurosci. 13, 279 (2019).

Gordon, E. M. et al. Generation and evaluation of a cortical area parcellation from resting-state correlations. Cereb. Cortex 26, 288–303 (2016).

He, M., Lu, D., Xu, J. & Xavier, R. M. Community detection in weighted multilayer networks with ambient noise. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.00486 (2021).

Chiquet. J., Donnet, S. & Barillon P. sbm: Stochastic Blockmodels [Internet]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sbm (2023).

Collin, G. et al. O10.5. Abnormal modular organization of the functional connectome predicts conversion to psychosis in clinical high-risk youth. Schizophr. Bull. 44, S104–S104 (2018).

Duan, J. et al. Dynamic changes of functional segregation and integration in vulnerability and resilience to schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 2200–11 (2019).

Iglesias-Parro, S., Ruiz De Miras, J., Soriano, M. F. & Ibáñez-Molina, A. J. Integration–segregation dynamics in functional networks of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 57, 1748–62 (2023).

Chan, M. Y., Park, D. C., Savalia, N. K., Petersen, S. E. & Wig, G. S. Decreased segregation of brain systems across the healthy adult lifespan. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1415122111 (2014).

Cohen, J. R. & D’Esposito, M. The segregation and integration of distinct brain networks and their relationship to cognition. J. Neurosci. 36, 12083–94 (2016).

Wig, G. S. Segregated systems of human brain networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 981–96 (2017).

Martin, S., Williams, K. A., Saur, D. & Hartwigsen, G. Age-related reorganization of functional network architecture in semantic cognition. Cereb. Cortex 33, 4886–903 (2023).

Wang, J. H. et al. Graph theoretical analysis of functional brain networks: test-retest evaluation on short- and long-term resting-state functional MRI data. PLoS ONE 6, e21976 (2021).

Chen, G., Chen, G., Xie, C. & Li, S. J. Negative functional connectivity and its dependence on the shortest path length of positive network in the resting-state human brain. Brain Connect. 1, 195–206 (2011).

Meunier, D., Achard, S., Morcom, A. & Bullmore, E. Age-related changes in modular organization of human brain functional networks. NeuroImage 44, 715–23 (2009).

Buckner, R. L. et al. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 29, 1860–73 (2009).

Buckley, P. F., Miller, B. J., Lehrer, D. S. & Castle, D. J. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 383–402 (2009).

Liu, T. T. Noise contributions to the fMRI signal: an overview. NeuroImage 143, 141–51 (2016).

Weiler, M. et al. Evaluating denoising strategies in resting-state functional magnetic resonance in traumatic brain injury (EpiBioS4Rx). Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 4640–9 (2022).

Andronache, A. Impact of functional MRI data preprocessing pipeline on default-mode network detectability in patients with disorders of consciousness. Front. Neuroinform. 7, http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fninf.2013.00016/abstract (2013)

Li, Y. T. et al. Impact of physiological noise in characterizing the functional MRI default-mode network in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 41, 166–81 (2021).

Scheel, N. et al. Evaluation of noise regression techniques in resting-state fMRI studies using data of 434 older adults. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1006056 (2022).

Wunderlich, S. et al. Denoising strategies of functional connectivity MRI data in lesional and non-lesional brain diseases. Radiol. Imaging http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.01.22.25320407 (2015).

Lamouroux, A., Coloigner, J., Maurel, P., Farrugia, N. & Lioi, G. Evaluating lesion-specific preprocessing pipelines for rs-fMRI in stroke patients: Impact on functional connectivity and behavioral prediction. Imaging Neurosci. 3, IMAG.a.6 (2025).

Griffanti, L. et al. Effective artifact removal in resting state fMRI data improves detection of DMN functional connectivity alteration in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, http://journal.frontiersin.org/Article/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00449/abstract (2015).

Dipasquale, O. et al. Comparing resting state fMRI de-noising approaches using multi- and single-echo acquisitions. PLoS ONE 12, e0173289 (2017).

Venkatesh, M., Jaja, J. & Pessoa, L. Comparing functional connectivity matrices: a geometry-aware approach applied to participant identification. NeuroImage 207, 116398 (2020).

Abbas, K. et al. Geodesic distance on optimally regularized functional connectomes uncovers individual fingerprints. Brain Connect. 11, 333–48 (2021).

Hannum, A., Lopez, M. A., Blanco, S. A. & Betzel, R. F. High-accuracy machine learning techniques for functional connectome fingerprinting and cognitive state decoding. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 5294–308 (2023).

Finn, E. S. et al. Can brain state be manipulated to emphasize individual differences in functional connectivity? NeuroImage 160, 140–51 (2017).

Curic, D., Kalasapura Venugopal Krishna, S., Davidsen, J. Efficacy of functional connectome fingerprinting using tangent-space brain networks. Neuroscience http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.01.17.633606 (2025).

Lemée, J. M. et al. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging versus task-based activity for language mapping and correlation with perioperative cortical mapping. Brain Behav. 9, e01362 (2019).

Ellis, C. A., Miller, R. L. & Calhoun, V. D. Identifying neuropsychiatric disorder subtypes and subtype-dependent variation in diagnostic deep learning classifier performance. Bioinformatics http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2022.10.27.514124 (2022).

Chand, G. B. et al. Two distinct neuroanatomical subtypes of schizophrenia revealed using machine learning. Brain 143, 1027–38 (2020).

Clementz, B. A., et al. Identification of distinct psychosis biotypes using brain-based biomarkers. AJP 173, 373–84 (2016).

Ballem R. et al. Mapping the psychosis spectrum – imaging neurosubtypes from multi-scale functional network connectivity. Neuroscience https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.11.637551 (2025).

Andrés-Camazón, P. et al. Neurobiology-based cognitive biotypes using multi-scale intrinsic connectivity networks in psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia 11, 45 (2025).

First, M. B., et al. Clinical applications of neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. AJP 175, 915–6 (2018).

Henderson, T. A. et al. Functional neuroimaging in psychiatry—aiding in diagnosis and guiding treatment. What the American Psychiatric Association does not know. Front. Psychiatry 11, 276 (2020).

Gu, S., et al. Emergence of system roles in normative neurodevelopment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13681–6 (2015).

Satterthwaite, T. D. et al. Heterogeneous impact of motion on fundamental patterns of developmental changes in functional connectivity during youth. NeuroImage 83, 45–57 (2013).

Jolles, D. D., Van Buchem, M. A., Crone, E. A. & Rombouts, S. A. R. B. A comprehensive study of whole-brain functional connectivity in children and young adults. Cereb. Cortex 21, 385–91 (2011).

Fair, D. A. et al. Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104(Aug), 13507–12 (2007).

Baum, G. L. et al. Modular segregation of structural brain networks supports the development of executive function in youth. Curr. Biol. 27, 1561–1572.e8 (2017).

Briend, F., Armstrong, W. P., Kraguljac, N. V., Keilhloz, S. D. & Lahti, A. C. Aberrant static and dynamic functional patterns of frontoparietal control network in antipsychotic-naïve first-episode psychosis subjects. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 2999–3008 (2020).

Althwanay, A., AlZamil, N. A., Almukhadhib, O. Y., Alkhunaizi, S., Althwanay, R. Risks and protective factors of the prodromal stage of psychosis: a literature review. Cureus. https://www.cureus.com/articles/31577-risks-and-protective-factors-of-the-prodromal-stage-of-psychosis-a-literature-review (2020).

Tooley, U. A. et al. The age of reason: functional brain network development during childhood. J. Neurosci. 42, 8237–51 (2022).

Power, J. D., Fair, D. A., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. The development of human functional brain networks. Neuron 67, 735–48 (2010).

Rubia, K. Functional brain imaging across development. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 22, 719–31 (2013).

Cao, H. et al. Progressive reconfiguration of resting-state brain networks as psychosis develops: Preliminary results from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS) consortium. Neuroscience http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/179242 (2017).

Di Martino, A. et al. Unraveling the miswired connectome: a developmental perspective. Neuron 83, 1335–53 (2014).

Addington, J. et al. Clinical and functional characteristics of youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis who do not transition to psychosis. Psychol. Med. 49, 1670–7 (2019).

Addington, J. et al. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS 2): the prodromal symptoms. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203(May), 328–35 (2015).

Addington, J., et al. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 665–72 (2007).

Tognin, S. et al. PSYSCAN multi-centre study: baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of the clinical high risk for psychosis sample. Schizophr 11, 66 (2025).

Andreassen, O. A., Hindley, G. F. L., Frei, O. & Smeland, O. B. New insights from the last decade of research in psychiatric genetics: discoveries, challenges and clinical implications. World Psychiatry 22, 4–24 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Our appreciation goes to Dr. Jason Xu from the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health for his invaluable consultations on the statistical models used in this research. This project was supported in part through a grant from The Rockefeller University Heilbrunn Family Center for Research Nursing awarded to R.M.X.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I. contributed to the methods, performed data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the initial version of and subsequent revisions to the manuscript. W.S. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, initial drafting and subsequent revisions to the manuscript. E.D. contributed substantially to the project’s conception, design and methods, supervised neuroimaging data analysis and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. R.M.X., the senior and corresponding author, secured project funding, supervised the project and made substantial contributions to its conception, design, methodology, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation as well as drafting and critically revising the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iyer, A., Stanford, W., Dayan, E. et al. Salience network segregation and symptom profiles in psychosis risk subgroups among youth and early adults. Schizophr 11, 142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00687-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00687-x