Abstract

Food fortification is an effective strategy to combat vitamin A deficiency. Gari, a cassava-based West African food product, is an interesting product to fortify with vitamin A, but the low stability of vitamin A poses a challenge. We showed that toasted wheat bran can stabilise vitamin A as retinyl palmitate (RP) during storage of RP-fortified gari to a limited extent. After four weeks of accelerated storage, the RP retention of gari with toasted wheat bran was 34 ± 9% whereas this was only 19.4 ± 0.3% for gari without bran. When comparing different fortification strategies, including RP addition, red palm oil addition and the use of yellow cassava, red palm oil addition was shown the most promising strategy. After eight weeks of accelerated storage, the vitamin A retention was more than four times higher for red palm oil-fortified gari (22.6 ± 0.1%) than for the two other fortification strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gari is a dry granular product obtained by fermenting and roasting ground cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). The process of converting raw cassava roots into gari, also called garification, has several advantages as it decreases the content of toxic hydrogen cyanide and increases the shelf life of the highly perishable cassava roots1,2. However, gari has a low nutritional value as it consists mainly of carbohydrates (86–91% dry matter (dm)) and is poor in essential minerals and vitamins, including vitamin A2,3,4. Gari is an important staple food in Ghana, Nigeria and other West African countries5. In this region, micronutrient deficiencies, including vitamin A deficiency, are highly prevalent6,7,8. Micronutrient deficiencies can cause severe adverse health effects. Vitamin A deficiency, in particular, can lead to blindness, an impaired immune system and other negative health effects8,9.

Food fortification has already been proven to be an effective strategy for preventing vitamin A deficiency, but the food product of choice determines its effectiveness. Ideally, an affordable food product which is consumed by all population groups should be chosen10,11. Gari fulfils these requirements and several studies have already investigated the fortification of gari with vitamin A. Amongst these studies, two fortification strategies can be distinguished, being the addition of ingredients rich in β-carotene (provitamin A) such as red palm oil, moringa seeds and orange-fleshed sweet potato, and biofortification by developing new β-carotene-rich cassava varieties, also called yellow cassava1,11,12,13,14. When looking at fortifying other food products, adding preformed vitamin A, mainly as retinyl palmitate (RP), is a widely applied strategy15,16,17. Nevertheless, we found no studies investigating the fortification of gari with RP.

Next to increasing the vitamin A content through addition of β-carotene-rich ingredients, RP or biofortification, ensuring a high vitamin A stability is crucial for effective food fortification. Stability is especially important in gari since gari can be stored for several months at ambient temperature. Unfortunately, RP and β-carotene degrade very rapidly under these conditions1,15. Bechoff et al.1 showed that about 54% of the initially present β-carotene in red palm oil-fortified gari was degraded after 80 days of storage at 33 °C. For biofortified gari, the stability of β-carotene was even lower as 87% of the initially present β-carotene was degraded under these conditions. To the best of our knowledge, no attempts to improve the stability of vitamin A in fortified gari by adding stabilising agents have been reported.

In a previous study, we showed that cereal bran can be used as a cost-effective vitamin A-stabilising agent with different cereal bran types having a different ability to stabilise vitamin A18. However, this stabilising effect was observed using model systems consisting of vitamin A in the form of RP, oil and cereal bran. It remains unknown whether the stabilisation will be maintained in a real food system, such as gari. The first objective of this study is therefore to investigate the potential of wheat and rice bran to stabilise RP in gari during accelerated storage. Hereto, three different bran samples are used: heat-treated rice bran, toasted wheat bran and native wheat bran. Based on our previous studies, a higher RP stability is expected in the bran-containing gari samples and native wheat bran is expected to be the least effective stabilising agent due to the presence of endogenous lipase activity19. The best stabilising effect is predicted for toasted wheat bran, given its high antioxidant capacity and the absence of endogenous lipase activity20. Next to the stabilising potential of cereal bran, three different fortification strategies, including the addition of RP, the addition of red palm oil and the use of biofortified yellow cassava will be compared in terms of vitamin A content and stability. This forms the second objective of this study. The information gained in this study can help to formulate guidelines and establish effective strategies for the fortification of gari with vitamin A that can be applied by local gari producers. Implementing the fortification of gari with vitamin A can help reduce the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency.

Results and discussion

The potential of cereal bran to stabilise RP during storage of gari

The RP retention as a function of storage time for RP-fortified gari samples without bran addition and with the addition of native wheat bran, heat-treated rice bran and toasted wheat bran is shown in Fig. 1. The initial vitamin A content of these four samples ranged from 2.5–3.8 µg retinol equivalents (REeq) per gram gari. RP degradation occurred relatively fast in the first week and then slowed down gradually. When comparing the different bran types, toasted wheat bran showed the best RP stabilisation, followed by heat-treated rice bran and then native wheat bran. This ranking corresponds to the RP stabilisation as observed in model systems in our previous studies19,20. However, for the gari samples the differences between the different samples are small and not always significant. In addition, the difference in RP retention between the control sample, without bran addition, and the samples with bran addition was relatively small. After one week of accelerated storage, no significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between the samples. For all four samples, between 43 and 55% of RP was retained after one week. After two and four weeks of storage, a clear stabilising effect was observed for the sample with toasted wheat bran. The RP retention for this gari sample was 53 ± 5% and 34 ± 9% after two and four weeks, respectively. For the sample without bran addition, the RP retention was only 36 ± 5% after two weeks and 19.4 ± 0.3% after four weeks of accelerated storage. However, these differences were not significant (p < 0.05) due to the relatively high batch-to-batch variation. After eight weeks of storage, about 2 to 10% of RP was retained in all samples. The RP retention was 1.9 ± 1.2%, 4.9 ± 0.9%, 7.2 ± 0.2% and 10.4 ± 1.1% for the gari sample with native wheat bran, without bran, with heat-treated rice bran and with toasted wheat bran, respectively. Hereby, the RP retention of the sample with toasted wheat bran was twice as high and significantly higher than the RP retention of the control sample without bran (p < 0.05).

Gari production was done in duplicate, and RP analysis was also done in duplicate, resulting in a 2 × 2 setup. Error bars represent standard deviations of duplicate gari production followed by accelerated storage. The initial vitamin A contents of the gari samples were 3.80 ± 0.02 µg retinol equivalents (REeq)/g (no bran), 3.2 ± 0.3 µg REeq/g (native wheat bran), 3.22 ± 0.07 µg REeq/g (toasted wheat bran) and 2.5 ± 0.2 µg REeq/g (heat-treated rice bran).

Based on these results, we can conclude that only toasted wheat bran can noticeably stabilise RP during gari storage. The stabilisation of RP by toasted wheat bran can be explained by the high antioxidant capacity of wheat bran and the absence of wheat bran endogenous enzymes due to toasting. This stabilisation mechanism was investigated in depth in our previous studies19,20,21. However, in gari, the RP-stabilising effect of cereal bran is limited, especially compared to the stabilising effect observed in our previous study where RP-enriched oil was mixed with toasted wheat bran19. The reason for this is assumed to be twofold. Firstly, the concentration of RP in the fortified gari is about a factor of 250 lower than the RP content of the model system consisting of 0.16% RP, 19.84% soy oil and 80.00% cereal bran, used in our previous study19. In another study, we showed that a high RP concentration combined with a high lipid content causes RP to act as a pro-oxidant, accelerating its own oxidation and lipid oxidation. Moreover, a negative correlation was observed between lipid oxidation and RP stability. This pro-oxidative effect is, to a certain extent, counteracted by bran antioxidants, such as polyphenols, phenolic acids and tocopherols, resulting in a pronounced RP stabilisation21,22,23. Given the low RP concentration and the low lipid content of the fortified gari, the pro-oxidative effect of RP is assumed to be absent here. This can, in part, explain the limited stabilising effect of cereal bran. It is therefore important to investigate the RP stability in the food matrix of interest fortified with the desired concentration of RP. Secondly, it is possible that the gari matrix as such stabilises RP to a certain extent, resulting in a less pronounced effect on RP stability when bran is added.

When comparing the RP stability in gari to other fortified food products, both lower and higher RP retentions compared to the RP retention in gari have been reported in the literature. Kim et al.15 reported an 85% RP loss in RP-fortified cornflakes after four weeks of storage at ambient temperature. When stored at an elevated temperature of 45 °C, RP degradation occurred faster and about 85% was already lost after two weeks. When comparing the RP stability observed in the study of Kim et al.15 with the RP stability in gari, it can be stated that RP shows good RP stability in the gari matrix. After two weeks of storage at 60 °C and 70% relative humidity, about 65% RP was lost in the fortified gari. This is lower than the RP loss observed in the study of Kim et al.15, even though the storage conditions in the study of Kim et al.15 were milder. However, other studies also reported higher RP retentions. For example, Lee et al.17 reported an RP retention higher than 90% in fortified rice after six weeks of storage at 35 °C and 80% relative humidity. Despite the milder storage conditions, the RP stability in the fortified rice is presumably higher than in gari. Nevertheless, comparing storage experiments performed at different temperatures and different relative humidities is challenging, especially when the storage temperature exceeds 40 °C. The Arrhenius plot can be used to calculate the reaction rate at different temperatures, whereby a temperature increase of 10 °C corresponds to a doubling of the reaction rate24. However, it has been shown that above 40 °C, other oxidation mechanisms can occur, which impedes the use of the Arrhenius equation. Furthermore, the combined effect of temperature and humidity further complicates the extrapolation to ambient conditions25. Despite this, we can conclude that the gari matrix as such provides a moderate RP stability, making gari a good food product of choice for RP fortification. It is hypothesised that the low RP concentration and the low oil content of gari prevent fast RP and lipid oxidation, resulting in good RP stability. In addition, the gari matrix might provide physical protection against oxidation. However, there is still room to improve the RP stability. The RP stability could be further improved by optimising packaging and storage conditions. RP oxidation can be prevented by limiting the contact with oxygen using vacuum or modified atmosphere packaging. In addition, storing gari at low temperatures can be done to slow down RP degradation, although this is expected to be difficult in practice26,27. Next to storage and packaging conditions, advanced RP stabilisation techniques such as microencapsulation could be explored28,29.

Apart from the RP stability, the gari quality and sensory characteristics are important. When looking at the effect of cereal bran addition on the quality characteristics of gari, no significant differences were observed (Table 1). All investigated gari samples had a moisture content lower than 12% and an ash content lower than 2.75%, which is in accordance with the Codex Alimentarius guidelines on gari quality30. However, the TTA was slightly lower than the specified minimum of 0.6%, which suggests the fermentation time should have been increased. Moreover, all gari samples showed a swelling capacity of around a factor three, which indicates good gari quality5. When looking at the colour, the gari samples enriched with cereal bran, particularly wheat bran, had a visually observed darker colour. The colour of both native and toasted wheat bran is darker than the colour of gari, with toasted wheat bran having the most intense dark brown colour due to the Maillard reaction during toasting. However, no significant differences in colour were measured. The colour change, likely together with other sensory attributes, is assumed to be the main limitation for applying cereal bran as a stabilising agent.

Despite the limited effect of cereal bran addition on the gari quality, no pronounced stabilising effect of cereal bran on RP was observed during the storage of gari (Fig. 1). Toasted wheat bran was the only bran sample that showed a small but significant potential to stabilise RP. However, this stabilisation should be verified at ambient storage conditions. Unfortunately, wheat bran is typically not locally produced in Ghana, which likely implies a higher ingredient cost. To circumvent this, the use of other locally sourced cereals could be explored. However, given the limited effect of cereal bran addition on the RP stability, it is possible that the investment cost would not make up for the improvement in RP stability and the impact on gari sensory aspects. To investigate this, a financial analysis should be carried out. Next to the production process for RP-fortified gari used in this study, the addition of a small amount of a mixture of RP, oil and cereal bran with a high RP concentration as an additive to gari could be another valuable fortification strategy. Hereby, cereal bran is used to stabilise RP in the additive which is highly concentrated in RP. Hence, the focus, in this case, is on RP stabilisation during storage of the additive rather than RP stabilisation during gari storage. Moreover, the amount of cereal bran added to gari would be much lower in this case compared to the amount added to the gari prepared in this study. This will reduce both the effect on sensory aspects as well as the investment cost.

Comparison of three strategies for the production of vitamin A-fortified gari

The local production of RP-fortified gari will be challenging as the RP used in this study is chemically synthesised on an industrial scale and not easily accessible to local producers. Therefore, two other fortification strategies were investigated. These include the addition of red palm oil to gari and the use of biofortified yellow cassava. Both red palm oil and yellow cassava are rich in provitamin A, mainly present as β-carotene1. In addition, both ingredients are locally produced in Ghana and, more broadly, in West Africa. This implies that both strategies could be feasible for local, small-scale gari producers. As the addition of cereal bran only had a limited effect on the RP stability, the use of cereal bran to stabilise vitamin A, in the form of β-carotene present in red palm oil and yellow cassava, will not be further investigated.

In Fig. 2, the vitamin A retention, expressed as a percentage of the initial RP or β-carotene content, is shown as a function of the storage time. Based on these results, it can be concluded that the red palm oil-fortified gari provided the highest vitamin A stability. After one week of accelerated storage, 94 ± 15% of vitamin A was retained for red palm oil-fortified gari, whereas the vitamin A retention was only 48 ± 9% for RP-fortified gari and 54 ± 1% for yellow cassava gari. After eight weeks of storage, the vitamin A retention for red palm oil fortified gari was 22.6 ± 0.1%, which was more than four times higher compared to the two other fortification strategies. In the literature, a limited number of studies were found that investigated the stability of β-carotene in red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari1,31,32,33. For RP-fortified gari, on the other hand, no studies were found. In the study of Abiodun et al.31, only yellow cassava gari was investigated and β-carotene retentions ranging from 47–72% were observed after two months of storage at ambient conditions. In the study of Bechoff et al.1, both fortification strategies were compared. A β-carotene retention of around 70% was observed for red palm oil-fortified gari stored for four weeks at 40 °C. For yellow cassava gari, a substantially lower β-carotene retention of 23% was measured after four weeks of storage. Although a lower storage temperature was used in the study of Bechoff et al.1, resulting in higher β-carotene retention, the higher β-carotene stability observed in red palm oil-fortified gari compared to yellow cassava gari is in line with our results. This can presumably be attributed to the presence of natural antioxidants in red palm oil and the protective effect of the oil matrix on β-carotene34.

The gari samples were stored for eight weeks at 60 °C and 70% relative humidity. Gari production was done in duplicate and vitamin A analysis was also done in duplicate, resulting in a 2 × 2 setup. Error bars represent standard deviations of duplicate gari production followed by accelerated storage. The initial vitamin A content of RP- fortified gari was 3.80 ± 0.02 µg retinol equivalents (REeq) per gram gari, using a conversion factor of 1.83:1. The initial vitamin A content of red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari was 1.88 ± 0.08 µg REeq/g and 2.5 ± 0.5 µg REeq/g, respectively, using a conversion factor of 6:1 for β-carotene. When using a conversion factor of 2.4:1 for red palm oil-fortified gari and 4.5:1 for yellow cassava gari, the initial vitamin A content was 4.7 ± 0.2 µg REeq/g and 3.3 ± 0.6 µg REeq/g, respectively.

Not only the vitamin A retention but also the vitamin A content is important to evaluate the effectiveness of the investigated fortification strategies. To this end, the RP or β-carotene content of the fortified gari samples was converted to retinol equivalents (REeq). This is, however, challenging as largely different conversion factors have been reported for β-carotene35. This is partly due to the effect of the food matrix on the bioavailability of β-carotene36. Moreover, little is known about the bioavailability of RP in the gari matrix. Using different conversion factors can substantially affect the resulting conclusions. To illustrate this, the vitamin A content (µg REeq/g gari) of red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari was calculated using two different conversion factors for β-carotene. For RP-fortified gari, one µg REeq corresponds to 1.83 µg RP37. When the generally accepted conversion factor of 6 µg β-carotene per µg REeq was used for red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari, the RP-fortified gari sample had the highest initial vitamin A content (3.80 ± 0.02 µg REeq/g), followed by the yellow cassava gari (2.5 ± 0.5 µg REeq/g) and the red palm oil-fortified gari (1.88 ± 0.08 µg REeq/g). Assuming a portion size of 50 g, one portion of RP-fortified gari, yellow cassava gari or red palm oil-fortified gari provides respectively about 27%, 18% or 13% of the recommended daily vitamin A intake. The vitamin A content is here compared with the recommended daily intake as this value was used to calculate the amount of vitamin A added to the gari. It should be noted that a calculation based on and a subsequent comparison with the estimated average requirement would be more appropriate38. However, after one week of accelerated storage, the differences in vitamin A content between the three different samples were reduced and the vitamin A content of all gari samples ranged between 1.3 and 1.8 µg REeq/g. After eight weeks of accelerated storage, this content was further reduced to 0.1–0.4 µg REeq/g, with the red palm oil-fortified gari having the highest vitamin A content. Different conclusions can be drawn when using the β-carotene conversion factors determined by Zhu et al.11 and La Frano et al.39, specifically determined for red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari. Hereby, one µg REeq corresponded to 2.4 µg β-carotene in red palm oil-fortified gari or 4.5 µg β-carotene in yellow cassava gari11,39. The difference in conversion factor might be explained by the presence of oil in the red palm oil-fortified gari, which can enhance the uptake of β-carotene. In addition, the possible inclusion of β-carotene in plant cell walls might reduce its bioaccessibility in yellow cassava gari40,41. Using these conversion factors, red palm oil-fortified gari had the highest initial vitamin A content (4.7 ± 0.2 µg REeq/g), followed by RP-fortified gari (3.80 ± 0.02 µg REeq/g) and yellow cassava gari (3.3 ± 0.6 µg REeq/g). This content corresponds to 34%, 27% and 24% of the recommended daily vitamin A intake per portion of 50 g, respectively. After one week of storage, the vitamin A content decreased to 4.4 ± 0.5 µg REeq/g, 1.8 ± 0.4 µg REeq/g and 1.8 ± 0.3 µg REeq/g for red palm oil-fortified gari, RP-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari, respectively. After eight weeks, 1.06 ± 0.04 µg REeq/g was retained in red palm oil-fortified gari, whereas less than 0.2 µg REeq/g was retained for the two other fortification strategies. Overall, it can be stated that the initial vitamin A content of the fortified gari samples ranged from 1.9 to 4.7 µg REeq/g, taking into account different β-carotene conversion factors. This aligns with the study of Bechoff et al.1, who measured an initial vitamin A content ranging from 2–3 µg REeq/g for red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari. Aruna et al.14 obtained a substantially higher vitamin A content for gari fortified with moringa seed powder.

Based on the results discussed above it can be concluded that the used conversion factors largely affect the final results in terms of vitamin A content. To make a statement about the effectiveness of the three investigated fortification strategies, human intervention studies are therefore required. Nevertheless, it can be stated that the red palm oil-fortified gari provided the best vitamin A stability. In addition, local production of red palm oil in Ghana and other West African countries makes this fortification strategy a feasible approach for small-scale producers. However, apart from the vitamin A content and stability, quality and sensory aspects are crucial determinants for consumer acceptance. Therefore, the main quality characteristics were analysed and a sensory analysis was performed.

In Table 2, an overview of the quality characteristics measured for regular gari, red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari is given. For all three gari samples, the moisture content, the ash content and TTA fell within the range specified in the Codex Alimentarius guidelines30. In addition, the pH and swelling capacity for the fortified gari samples did not differ significantly from the regular gari (p < 0.05). All gari samples had a swelling capacity factor of around three, which is desirable. The particle size for yellow cassava gari was significantly smaller than for regular, unfortified gari and red palm oil-fortified gari (p < 0.05). Most importantly, the colour of the fortified gari samples was significantly more yellow than the regular gari, as measured by the b-value. This was, however, not surprising given the intense orange colour of β-carotene. The L-value for the fortified samples was slightly lower compared to the regular gari. This indicates a less bright colour for the fortified gari, although the difference was not significant (p < 0.05).

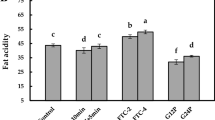

Next to the analysis of the quality characteristics, a sensory analysis was performed. The average scores attributed during this sensory analysis are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3. As shown in Table 3, the taste and smell of both fortified gari samples were rated significantly lower than the regular gari. In addition, the colour of the yellow cassava gari was given a significantly lower score than the regular gari. The colour of red palm oil-fortified gari was also scored lower than the regular gari, yet not significantly lower (p < 0.05). This is likely due to the more yellow colour of the fortified samples. For the mouthfeel and sourness, no significantly different scores were given for the three gari types. When looking at the overall appearance of the fortified gari samples (Fig. 3), both samples were scored lower than the regular gari for both preparation methods. Although when prepared as if the gari would be used for gari with beans or shito, the attributed scores were not significantly different from the regular gari. For the preparation of gari soakings, on the other hand, the fortified gari samples were rated significantly lower. Consequently, it is advisable to use the fortified gari for the preparation of gari with beans or shito rather than for soakings.

Overall appearance of three gari samples prepared with the addition of a small amount of water as if it would be for gari with beans/shito (A), and with the addition of a large amount of water as if it would be for soakings (B). The three gari samples included regular gari (control), gari with red palm oil and gari made from yellow cassava. An untrained panel of 77 participants scored the samples based on a hedonic scale, whereby 1 is the lowest and 9 is the highest score. Samples indicated with a different letter are significantly different (p < 0.05).

The results from the sensory analysis corresponded well with the main conclusion from the focus group discussion. During this discussion, the overall appearance of the regular gari was rated the highest and attributed an average score of 8.3. The fortified samples were rated slightly lower. The red palm oil-fortified gari and yellow cassava gari were given an average score of 7.8 and 7.3, respectively. Despite the slightly lower scores, the participants indicated that they would be more willing to buy the fortified gari because of its associated health benefits. When comparing the obtained results regarding the gari quality and sensory aspects with existing literature, similar observations are described in the literature13,42. As stated by Adinsi et al.13, the main gari characteristics affected by fortification include colour and odour, whereas other characteristics, such as swelling capacity, texture and sourness, are not affected. Despite the negative impact of vitamin A fortification on the quality and sensory attributes, consumers with previous knowledge of fortification tend to associate the yellow colour of fortified gari with health benefits such as a positive influence on eyesight42. Consequently, as stated by Bechoff et al.42, campaigns to inform consumers about the health benefits of gari fortification are crucial and might overcome the limited negative effect on sensory attributes.

In conclusion, the goal of this study was to explore different strategies to fortify gari, a cassava-based West African food product, with vitamin A whereby obtaining a high vitamin A stability during storage was the main focus. In the first part of this study, the potential of cereal bran to stabilise RP during gari storage was investigated. Unfortunately, cereal bran addition only resulted in a limited improvement of the RP stability. This effect was significant but small for toasted wheat bran. For native wheat bran and heat-treated rice bran, RP stabilisation was not observed. Therefore, it is advised to use cereal bran to stabilise RP in a highly concentrated food additive consisting of RP, oil and cereal bran rather than during storage of the fortified food product itself. In the second part, three different strategies for the fortification of gari were tested. These strategies included the addition of RP, the addition of red palm oil and the use of yellow cassava. Amongst these three approaches, the incorporation of red palm oil is the most promising fortification strategy. This approach resulted in the highest vitamin A stability during accelerated storage. Moreover, the effect of red palm oil addition on the gari quality and sensory aspects was limited. In addition, as red palm oil is locally produced in many African countries, this fortification strategy is easily applicable for small-scale local producers. However, more research is needed to accurately estimate the vitamin A degradation in red palm oil-fortified gari during storage at ambient conditions.

Materials and methods

Materials

White cassava roots (Manihot esculenta Crantz) were obtained from local farmers (Ashanti region, Ghana). Yellow cassava roots were provided by the Crop Research Institute of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (Fumesua, Ghana). Commercial wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.) bran were from Dossche mills (Deinze, Belgium) and Mars (Olen, Belgium), respectively. Prior to use, wheat bran was milled to an average particle size of 322 ± 4 µm using a Cyclotec 1093 Sample Mill (FOSS, Högenas, Sweden) with a 0.5 mm sieve. After milling, a part of the wheat bran was toasted for 30 min in an oven (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) at 170 °C as described by Jacobs et al.43. Rice bran was heat-treated at the supplier and had an average particle size of 290 ± 13 µm. Both the heat treatment of wheat and rice bran were sufficient to inactivate peroxidase, the most heat-stable enzyme in cereal bran, which was verified by measuring the peroxidase activity according to Bergmeyer44. Red palm oil was supplied by Bange farms (Ejisu-Krapa, Ghana) and soy oil was from Vandemoortele (Izegem, Belgium). Prior to use, impurities in soy oil, including surface-active components, were removed as described in Bahtz et al.45, with some minor modifications. To this end, 50 mL soy oil was shaken with 10 g Florisil® (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 2 hours and filtered.

Retinyl palmitate (RP) ( > 93% purity) and retinyl acetate (99.7% purity) were from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). β-Carotene (0.8 mg/L acetone) was from DHI (Hørsholm, Denmark). Chloroform, methanol and methyl tert-butyl ether were from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), acetonitrile and ammonium acetate were from VWR (Haasrode, Belgium), and ethyl acetate and acetone were from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Solvents used for the analysis of RP and β-carotene were HPLC-grade.

Gari production

The processing of cassava roots into gari was initiated within 12 hours after harvest. White (47–75 kg) or yellow cassava roots (38–41 kg) were manually peeled, washed and mechanically ground. The white (33–36 kg) or yellow (19–21 kg) cassava mash was loaded into a polypropylene sack and subjected to simultaneous spontaneous fermentation and dewatering for 40 hours using a hydraulic press. The fermented cassava grits was sieved (mesh size 1.40 mm) to remove fibers and divided into portions of 1 kg for roasting. Each portion of 1 kg was roasted for 17 minutes on a cook stove with a stainless-steel plate, heated by a wood fire. During roasting, the temperature of the stainless-steel plate was monitored with an infrared thermometer at a distance of three to five centimeters from the plate to limit temperature variations during the roasting of the different batches.

For gari samples fortified with RP, RP was first dissolved in soy oil and mixtures consisting of 6.7 g RP-enriched soy oil (0.05% RP in oil) and 26.8 g cereal bran on dry matter basis were prepared. These mixtures were added to 1 kg of fermented cassava grits after 10 minutes of roasting. At this point in the roasting process, the gari is not yet completely dry, which facilitates the adhesion of RP and bran to the gari particles. Moreover, a comparison of the measured vitamin A content of the RP-fortified gari samples (2.5–3.8 µg REeq/g) and the calculated vitamin A content (3.5 µg REeq/g) showed that RP degradation during the last 7 minutes of roasting was limited. Three different cereal bran samples were used: native wheat bran, toasted wheat bran and heat-treated rice bran. A control sample without bran, gari to which 6.7 g RP-enriched soy oil (0.05% RP in oil) was added after 10 minutes of roasting, was also included. The level of RP addition was calculated based on an average portion size of 50 g and a daily intake of 700 µg/day, the average recommended daily intake for men and women38. The amount of RP added to the fortified gari corresponds to 25% of the recommended daily intake per portion. For the gari samples fortified with red palm oil, 6.7 g of red palm oil was added after 10 minutes of roasting. No vitamin A was added for yellow cassava samples as vitamin A, in the form of β-carotene, is present in yellow cassava. An unfortified gari sample without cereal bran, RP or β-carotene added was also produced using white cassava.

For each sample type, the entire gari production process was performed in duplicate to account for day-to-day variability. For each production trial, the processing steps up to sieving were performed with the entire cassava quantity. After sieving, the fermented cassava grits was divided into portions of one kg to which red palm oil, RP-enriched soy oil and/or cereal bran were added. Consequently, the different sample types produced on the same day were fermented as one batch. After production, the gari samples were stored at −80 °C in plastic bags. An estimated yield calculation of the gari production process can be found in Table S1.

Analysis of gari quality characteristics

The moisture content, ash content, pH, total titratable acidity (TTA), colour, swelling capacity and particle size of the produced gari samples were evaluated as these physicochemical properties give an indication of the gari quality. The moisture content and ash content were determined according to AACC Method 44-15.02 and AACC Method 08-01.01, respectively46. To measure the pH, 1.00 g gari was suspended in 50 mL deionised water and the pH of this suspension was recorded. Next, this suspension was titrated with 0.1 M NaOH until a pH of 8.5 to determine the TTA. The TTA was calculated based on the volume 0.1 M NaOH needed to reach a pH of 8.5 assuming the main acid present in gari is lactic acid. The colour of the gari samples was measured according to the L*a*b colour system with a chroma meter (CR-410, Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The L-value gives an indication of the brightness of the sample, whereas the b-value provides an indication of the yellowness. The particle size of the gari was determined by sieving as described by Jacobs et al.47. Hereto, 20.0 g gari was sieved for 30 minutes using a Vibratory Sieve Shaker (Retsch, Aartselaar, Belgium) at a frequency of 1.5 s−1 with sieves of mesh size 2.00 mm, 1.00 mm, 500 µm and 250 µm. The average particle size was calculated based on the mass of gari remaining on each sieve. The swelling capacity was determined according to Bainbridge et al.48, with some minor modifications. Hereto, a 50 mL measuring cylinder was filled to the 10 mL mark with gari and deionised water was added to the 50 mL mark. The cylinder was inverted two times immediately after water addition and two times after two minutes of soaking. After soaking for 30 minutes, the final volume of the gari was recorded. The swelling capacity factor was calculated as the ratio of the final to the initial volume of gari.

Accelerated storage experiments

The gari samples produced as described above were divided into six portions of approximately 20 g each. One portion was frozen at −80 °C and this sample corresponded to a storage time of zero weeks (starting point). The other five portions were stored in the dark in open, plastic containers (d: 4.6 cm, h: 8 cm) for 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8 weeks in a climate chamber (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) at 60 °C and 70% relative humidity. These storage conditions were chosen based on our previous study18. Moreover, it is advised to avoid storage temperatures exceeding 60 °C as other lipid oxidation mechanisms might occur at higher temperatures49,50. After the indicated storage time, the gari samples were stored at −80 °C before analysis of the RP or β-carotene content.

Quantification of retinyl palmitate (RP) and β-carotene

Quantification of retinyl palmitate (RP)

RP was extracted from the stored gari samples and the gari samples that were not stored using chloroform/methanol (Chl/MeOH) as extraction solvent. To this end, the extraction procedure described in Van Wayenbergh et al.51 was adapted to a sample amount of 10 g. Modification was necessary given the low RP content of the fortified gari and the need to monitor the RP content during storage with high accuracy. To 10.0 g RP-fortified gari, 1.0 mL internal standard (50 µg retinyl acetate/mL methanol), 1.0 mL chloroform and 73 mL Chl/MeOH (1/1, volume-to-volume (v/v)) were added. After shaking (90 min, 175 strokes per minute (spm), room temperature (RT)) and centrifugation (2000g, 10 min, 20 °C), the supernatant was decanted, and the residue was re-extracted with 75 mL Chl/MeOH (1/1, v/v). After shaking (90 min, 175 spm, RT) and centrifugation (2000g, 10 min, 20 °C), the supernatant was decanted, and both extracts were pooled. Milli-Q water (45 mL) was added to the pooled extracts to induce phase separation. This phase separation was achieved by shaking (30 min, 175 spm, RT) and centrifugation (2000g, 10 min, 20 °C). The upper methanol/water layer was removed, and the lower chloroform layer was filtered over sodium sulphate. Next, chloroform was evaporated using the rotational evaporator (40 °C). The residue was redissolved in 5.0 mL acetone/methanol (7/3, v/v) and filtered (0.45 µm) into an amber glass vial. RP was analysed with reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection as described in Van Wayenbergh et al.51 The HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was equipped with a Kinetex C18 column (5 µm, 150 x 4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) and consisted of an LC-20AT pump, a DGU-20A5 degasser, a SIL-20AC HT autosampler (10 °C), a CTO-20AC column oven (30 °C) and an SPD-10Avp UV-VIS detector (325 nm). A tertiary gradient elution with methanol, MilliQ water and methanol/methyl tert-butyl ether (50/50, v/v) was used at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection volume was set at 10 µL. OriginPro 2018 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) was used to separate the RP peak from a partially overlapping peak, presumably originating from the gari matrix, present in the HPLC profiles. The RP content (µg/g) of the samples was determined based on a calibration curve and the RP retention (%) was calculated as:

Quantification of β-carotene

β-carotene was extracted from the gari samples fortified with red palm oil and the samples made with yellow cassava according to the procedure developed in Van Wayenbergh et al.51 using Chl/MeOH as extraction solvent, with minor adaptations. To 0.50 g gari, 10 mL methanol, 5 mL chloroform and 1.0 mL Milli-Q water were added. After vortexing (30 s), 5 mL chloroform and 5 mL Milli-Q water were added, followed by vortexing for 30 s and centrifugation (750 g, 10 min, 20 °C). The upper methanol/water phase was removed and the lower chloroform phase was transferred to a clean tube. The residue was re-extracted with 10 mL Chl/MeOH (1/1, v/v) and 3 mL Milli-Q water. After vortexing (30 s) and centrifugation (750 g, 10 min, 20 °C), the phases were separated as described above. The above-mentioned extraction steps were repeated a second time. All chloroform extracts were pooled, and the solvent was evaporated with the rotational vacuum concentrator (2-25 CDplus, Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany) at 40 °C and 2 mbar. The residue was redissolved in 5.0 mL acetone/methanol (7/3, v/v) and filtered (0.45 µm) into an amber glass vial.

β-carotene was quantified by HPLC-UV analysis according to the method described in Gheysen et al.52. Hereto, the HPLC system and column as specified earlier were used. The temperature of the autosampler was set at 10 °C, the oven temperature at 30 °C, the detector’s wavelength at 436 nm, the injection volume at 40 µL and the flow rate at 0.7 mL/min. Tertiary gradient elution was used with methanol/ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.2, 0.5 M) (80/20, v/v), acetonitrile/Milli-Q water (90/10, v/v) and ethyl acetate. OriginPro 2018 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) was used to separate the β-carotene peak from a partially overlapping peak present in the HPLC profile. β-carotene was quantified using a calibration curve set up in the range of 0–1 µg/mL and the β-carotene retention was calculated.

Sensory evaluation of vitamin A-fortified gari

A sensory evaluation was conducted to test the consumer acceptability of the vitamin A-fortified gari. Hereto, consumers were served five gari samples, including two with and three without cereal bran addition. However, in this study, only the sensory evaluation of the three gari samples without bran will be discussed. These samples included a control sample consisting of regular, unfortified gari, a sample fortified with red palm oil and a sample made with yellow cassava. The two samples with bran addition are left out here as the analysis of the vitamin A stability during storage did not reveal a strong stabilising effect of cereal bran. The samples fortified with red palm oil and yellow cassava were chosen for sensory evaluation as these fortification strategies are the most feasible in practice. An untrained panel of 77 high school students (T.I. Ahmadiyya Senior High School, Kumasi, Ghana) was asked to score the gari samples on five attributes (colour, smell, taste, mouthfeel, and sourness) according to a 9-point hedonic scale. Hereby, ‘1’ corresponds to ‘extremely dislike’ and ‘9’ corresponds to ‘extremely like’. In addition, the participants were asked to score the overall appearance of the fortified gari with the addition of a small amount and a large amount of water. These two preparation methods correspond to typical gari-based dishes: gari with beans or shito (a sauce made with fish and peppers), and soakings, respectively.

In addition to the sensory analysis, a focus group discussion was held with seven gari producers from the Ashanti region, Ghana. The producers were served the same gari samples as discussed above for the sensory analysis and were asked to rate the overall appearance of the samples based on a 9-point hedonic scale. Afterwards, the given scores were discussed.

Statistical analysis

Gari production followed by accelerated storage was performed in duplicate. The quantification of RP or β-carotene was also performed in duplicate for each sample, resulting in a 2×2 setup. Standard deviations on the RP or β-carotene retention therefore represent standard deviations of duplicate gari production followed by accelerated storage. The analysis of the gari quality characteristics was also performed in duplicate. Standard deviations on the quality characteristics thus represent standard deviations of duplicate gari production. For the data on vitamin A retention during storage and the analysed quality characteristics, statistical differences were tested by one-way analysis of variance, with a comparison of mean values using the Tukey test (α = 0.05) (JMP Pro 16, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

For the results from the sensory evaluation, statistical differences were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, followed by a Dunn test. Hereby, the former test was used to investigate if there were significant differences (α = 0.05) between the different samples and the latter was used to test which samples significantly differed from each other (α = 0.05) (JMP Pro 16, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the KU Leuven Research Data Repository (RDR) at https://doi.org/10.48804/ALTRWW.

Abbreviations

- Chl:

-

chloroform

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- MeOH:

-

methanol

- REeq:

-

retinol equivalents

- RP:

-

retinyl palmitate

- RT:

-

room temperature

- spm:

-

strokes per minute

- TTA:

-

total titratable acidity

- v/v:

-

volume-to-volume ratio

References

Bechoff, A. et al. Carotenoid stability during storage of yellow gari made from biofortified cassava or with palm oil. J. Food Compos. Anal. 44, 36–44 (2015).

Akely, P. M. T., Gnagne, E. H., To Lou, G. M. L. T. & Amani, G. N. G. Varietal influence of cassava on chemical composition and consumer acceptability of gari. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 56, 1239–1246 (2021).

Gegios, A. et al. Children consuming cassava as a staple food are at risk for inadequate zinc, iron, and vitamin A intake. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 65, 64–70 (2010).

Montagnac, J. A., Davis, C. R. & Tanumihardjo, S. A. Nutritional value of cassava for use as a staple food and recent advances for improvement. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 8, 181–194 (2009).

Oduro, I., Ellis, W. O., Dziedzoave, N. T. & Nimako-Yeboah, K. Quality of gari from selected processing zones in Ghana. Food Control 11, 297–303 (2000).

Bailey, R. L., West, K. P. & Black, R. E. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 66, 22–33 (2015).

Han, X., Ding, S., Lu, J. & Li, Y. Global, regional, and national burdens of common micronutrient deficiencies from 1990 to 2019: A secondary trend analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. eClinicalMedicine 44, 101299 (2022).

WHO. Global prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in populations at risk 1995-2005. World Heal. Organ. 55 (2009).

Wiseman, E. M., Bar-El Dadon, S. & Reifen, R. The vicious cycle of vitamin A deficiency: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 3703–3714 (2017).

Chadare, F. J. et al. Conventional and food-to-food fortification: An appraisal of past practices and lessons learned. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 2781–2795 (2019).

Zhu, C. et al. Red palm oil-supplemented and biofortified cassava gari increase the carotenoid and retinyl palmitate concentrations of triacylglycerol-rich plasma in women. Nutr. Res. 35, 965–974 (2015).

Atuna, R. A., Achaglinkame, M. A., Accorley, T. A. S. & Amagloh, F. K. Cassava orange-fleshed sweetpotato composite gari: A potential source of dietary vitamin A. Front. Nutr. 8, 646051 (2021).

Adinsi, L. et al. Sensory and physicochemical profiling of traditional and enriched gari in Benin. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 3338–3348 (2019).

Aruna, T. E. et al. Evaluation of Nutritional Value and Sensory Properties of Moringa oleifera Seed Powder Fortified Sakada (A Cassava-Based Snack). J. Food Chem. Nanotechnol. 7, 54–59 (2021).

Kim, Y. S., Strand, E., Dickmann, R. & Warthesen, J. Degradation of vitamin A palmitate in corn flakes during storage. J. Food Sci. 65, 1216–1219 (2000).

Klemm, R. D. W. et al. Vitamin A fortification of wheat flour: Considerations and current recommendations. Food Nutr. Bull. 31, 47–61 (2010).

Lee, J., Hamer, M. L. & Eitenmiller, R. R. Stability of retinyl palmitate during cooking and storage in rice fortified with Ultra Rice(TM) fortification technology. J. Food Sci. 65, 915–919 (2000).

Van Wayenbergh, E. et al. Cereal bran protects vitamin A from degradation during simmering and storage. Food Chem. 331, 127292 (2020).

Van Wayenbergh, E., Blockx, J., Langenaeken, N. A., Foubert, I. & Courtin, C. M. Conversion of Retinyl Palmitate to Retinol by Wheat Bran Endogenous Lipase Reduces Vitamin A Stability. Foods 13, 80 (2023).

Van Wayenbergh, E., Coddens, L., Langenaeken, N. A., Foubert, I. & Courtin, C. M. Stabilisation of vitamin A by cereal bran: importance of the balance between antioxidants, pro-oxidants and oxidation sensitive components. J. Agric. Food Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04585 (2023).

Van Wayenbergh, E., Langenaeken, N. A., Verheijen, J., Foubert, I. & Courtin, C. M. Mechanistic understanding of the stabilisation of vitamin A in oil by wheat bran: the interplay between vitamin A degradation, lipid oxidation, and lipase activity. Food Chem. 436, 137785 (2024).

Goufo, P. & Trindade, H. Rice antioxidants: Phenolic acids, flavonoids, anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, tocopherols, tocotrienols, c-oryzanol, and phytic acid. Food Sci. Nutr. 2, 75–104 (2014).

Onipe, O. O., Jideani, A. I. O. & Beswa, D. Composition and functionality of wheat bran and its application in some cereal food products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 50, 2509–2518 (2015).

Naveršnik, K. & Jurečič, R. Humidity-corrected Arrhenius equation: The reference condition approach. Int. J. Pharm. 500, 360–365 (2016).

Sullivan, J. C., Budge, S. M. & St-Onge, M. Modeling the primary oxidation in commercial fish oil preparations. Lipids 46, 87–93 (2011).

Fávaro, R. M. D., Iha, M. H., Mazzi, T. C., Fávaro, R. & Bianchi, M. D. L. P. Stability of vitamin A during storage of enteral feeding formulas. Food Chem. 126, 827–830 (2011).

Hemery, Y. M. et al. Storage conditions and packaging greatly affects the stability of fortified wheat flour: Influence on vitamin A, iron, zinc, and oxidation. Food Chem. 240, 43–50 (2018).

Gonçalves, A., Estevinho, B. N. & Rocha, F. Microencapsulation of vitamin A: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 51, 76–87 (2016).

Loveday, S. M. & Singh, H. Recent advances in technologies for vitamin A protection in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19, 657–668 (2008).

Codex Alimentarius. Standard for gari CXS 151-1989. at (2019).

Abiodun, O. A., Ayano, B. & Amanyunose, A. A. Effect of fermentation periods and storage on the chemical and physicochemical properties of biofortified cassava gari. J. Food Process. Preserv. 44, 1–8 (2020).

Eyinla, T. E., Maziya-Dixon, B., Alamu, O. E. & Sanusi, R. A. Retention of Pro-Vitamin A content in products from new biofortified cassava varieties. Foods 8, 1–14 (2019).

Aragón, I. J., Ceballos, H., Dufour, D. & Ferruzzi, M. G. Pro-vitamin A carotenoids stability and bioaccessibility from elite selection of biofortified cassava roots (Manihot esculenta, Crantz) processed to traditional flours and porridges. Food Funct. 9, 4822–4835 (2018).

Mba, O. I., Dumont, M. J. & Ngadi, M. Palm oil: Processing, characterization and utilization in the food industry - A review. Food Biosci. 10, 26–41 (2015).

Van Loo-Bouwman, C. A., Naber, T. H. J. & Schaafsma, G. A review of vitamin A equivalency of β-carotene in various food matrices for human consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 111, 2153–2166 (2014).

Desmarchelier, C. & Borel, P. Overview of carotenoid bioavailability determinants: From dietary factors to host genetic variations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 69, 270–280 (2017).

SCF. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on the tolerable upper intake level of Preformed Vitamin A (retinol and retinyl esters) (2002).

EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin A. EFSA J. 13, 4028 (2015).

La Frano, M. R., Woodhouse, L. R., Burnett, D. J. & Burri, B. J. Biofortified cassava increases β-carotene and vitamin A concentrations in the TAG-rich plasma layer of American women. Br. J. Nutr. 110, 310–320 (2013).

Ke, Y. et al. Effects of cell wall polysaccharides on the bioaccessibility of carotenoids, polyphenols, and minerals: an overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1–14 https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2089626 (2022).

Yonekura, L. & Nagao, A. Intestinal absorption of dietary carotenoids. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 51, 107–115 (2007).

Bechoff, A., Chijioke, U., Westby, A. & Tomlins, K. I. Yellow is good for you’: Consumer perception and acceptability of fortified and biofortified cassava products. PLoS One 13, 1–22 (2018).

Jacobs, P. J., Hemdane, S., Delcour, J. A. & Courtin, C. M. Dry heat treatment affects wheat bran surface properties and hydration kinetics. Food Chem. 203, 513–520 (2016).

Bergmeyer, H. U. Methods of enzymatic analysis. (Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie G.m.b.H., 1974).

Bahtz, J. et al. Adsorption of octanoic acid at the water/oil interface. Colloids Surf. B. 74, 492–497 (2009).

AACC. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. (St. Paul, MN, USA: American Association of Cereal Chemists, 2000).

Jacobs, P. J., Hemdane, S., Dornez, E., Delcour, J. A. & Courtin, C. M. Study of hydration properties of wheat bran as a function of particle size. Food Chem. 179, 296–304 (2015).

Bainbridge, Z., Tomlins, K., Wellings, K. & Westby, A. Methods for assessing quality characteristics of non-grain starch staples, part 2: Field methods. (Chatham, Kent, United Kingdom: Natural Resources Institute, 1996).

Frankel, E. N. Stability methods. In Lipid oxidation 165–186 (Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing, 2012).

Mancebo-Campos, V., Fregapane, G. & Desamparados Salvador, M. Kinetic study for the development of an accelerated oxidative stability test to estimate virgin olive oil potential shelf life. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 110, 969–976 (2008).

Van Wayenbergh, E., Verheijen, J., Langenaeken, N. A., Foubert, I. & Courtin, C. M. A simple method for analysis of vitamin A palmitate in fortified cereal products using direct solvent extraction followed by reversed-phase HPLC with UV detection. Food Chem. 404, 134584 (2023).

Gheysen, L. et al. Impact of Nannochloropsis sp. dosage form on the oxidative stability of n-3 LC-PUFA enriched tomato purees. Food Chem. 279, 389–400 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Samuel Owusu-Takyi and his team from the Kumasi Institute of Tropical Agriculture (KITA) for providing the gari processing equipment and to the students and staff of KITA and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) for their help with the gari production and sensory analysis. The authors would also like to thank Redeemer Agbolegbe for his help with the laboratory analysis. Eline Van Wayenbergh wishes to thank the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, Brussels, Belgium) for a position as a PhD fellow (Grant number: 11H5720N). Niels A. Langenaeken wishes to thank the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, Brussels Belgium) (Grant number: 12A8723N) and Internal Funds KU Leuven (PDMT1/21/021) for a position as a postdoctoral research fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.V.W., A.A.B., N.A.L., W.O.A., I.F., I.O. and C.M.C. contributed to the conceptualization of the research design and used methodology. E.V.W., J.B. and A.A.B. were responsible for the experimental analysis and data collection, under the supervision of I.F., I.O. and C.M.C. E.V.W. performed data visualization and wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed the original draft and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Wayenbergh, E., Boakye, A.A., Baert, J. et al. Vitamin A stability during storage of fortified gari produced using different fortification strategies. npj Sci Food 8, 102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00350-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00350-2