Abstract

This study compared the effects of cooking processes (including steaming, boiling, hot-air roasting and microwaving) on the nutrients of Dioscorea opposita planting in sandy soil (SSCY) and loessial soil (LSCY). The contents of crude fiber and reducing sugar increased significantly during cooking for SSCY, whereas those of LSCY remained unchanged. A significant decline in allantoin content was observed in boiled yams (approximately 6.0% for SSCY and 14.1% for LSCY, respectively). Moreover, the differences in chemical compositions between SSCY and LSCY were compared using non-targeted metabolomics. Totally, 656 differential metabolites of LSCY were identified, including lipids, nucleotides, amino acids and derivatives, and organic acids, which might be the key reason why LSCY exhibits higher nutritional values than SSCY. This research contributed to understanding the systematic metabolic changes during planting and the molecular mechanisms influencing the quality formation, providing the theoretical references for the more scientific consumption of Chinese yam.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Yam (family: Dioscoreaceae, over 600 species), an annual or perennial climbing plant with edible rhizome or underground tuber originated principally from Africa (especially West Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire) and Asia (primarily in China, Japan and Korea)1. Globally, the planting area of yam across the world was ~10.6 million hectare, and the annual production reached to ~89.3 million tons in 2023 (FAOSTAT)2. The total production of yam in China was ~11.344 million tons in 2022 and 10.987 million tons in 2023. Chinese yam (Dioscroea opposita Thunb., “Shanyao” in Chinese) has been one of the well-known edible and pharmaceutical foods in China, widely cultivated and distributed in China, mainly in northeastern, central and southeastern regions3. Yam tuber is rich in starch, protein, polysaccharides, sapogenins, allantoin, polyphenols, flavonoids, minerals (e.g., Ca, P, K, Na etc.), and other active components4,5, which is distinguished by the nutritional value and biological activities, including antioxidant6, anti-aging7, anti-viral8, immunomodulatory9, anti-cancer5, hypoglycemic effects10.

The soil exerts a significant influence on the composition and nutrients in plants11,12. The south of Wenxian county is adjacent to the Yellow River, leading to the sandy soil. Close to Taihang Mountain, the soil in the north of Wenxian mainly consists of loessial soil13,14. According to different planting regions, D. opposita in Wenxian mainly divided into Chinese yam growing in sandy soil (SSCY) and loessial soil (LSCY). Among the different culinary processes, boiling and steaming are the most common daily cooking methods of D. opposita under home conditions. Nowadays, the cooking processes have been optimized to maintain the nutrients and improve the quality of foods. The innovative technologies used in food processing have emerged, such as high-pressure processing, vacuum spray, ultrasound, microwave, and hot-air roasting etc15. Microwave (MW) heats, dries and defrosts foods by exposing it to electromagnetic radiation in a frequency range of 300 MHz to 300 GHz and wavelength between 1 m and 1 mm, which is a common and green technology in food processing16. The hot-air roasting technology allows the circulation of hot air at a high-temperature flow rate (140−200 °C) surround the food, which induces a fast mass transfer in a transient state inside the food, and gradually dehydrates the foods15. Therefore, the modern food processing not only reduces processing time, cost, and nutrition loss, but also maintains environmental-friendly and high sensory quality17.

However, cooking significantly influences on the texture, nutrition and chemical composition of foods. Improper cooking methods could lead to loss of nutrients in food, for example, prolonged high-temperature frying might lead to vitamin C loss. Guo et al.18 found that the roasting and frying process significantly affected the contents of nutritional and potentially harmful components in peanuts, including fructose, starch, saturated fatty acids, and flavonoids. Roncero-Ramos et al.19 investigated the effects of culinary treatments (boiling, microwaving, grilling, and frying) on composition and antioxidant capacity of mushrooms, and suggested that microwaving and grilling were considered as best process to maintain the nutrients. According to Xu et al.20, cooking methods (including steaming, microwave heating, boiling and stir-frying) significantly reduced anthocyanin and total glucosinolates in red cabbage. Although red cabbages consumed as salad could maintain the highest nutrition, considering cooking habits of Asian cuisine, stir-frying and boiling process significantly decreased the contents of total phenolic, vitamin C, and DPPH radical-scavenging activity.

D. opposita is commonly prepared at home through steaming, boiling, or hot-air roasting. Therefore, the effects of different cooking methods (steaming, boiling, hot-air roasting, and microwaving) on the nutrition (moisture, ash, fat, reducing sugar, protein, crude fiber, allantoin, flavonoids, polyphenols, ascorbic acid) of D. opposita growing in different soil types (sandy and loessial soils) were studied. Furthermore, the impacts of sandy soil and loessial soil on the composition and levels of primary and secondary metabolites of D. opposita were studied using UPLC-MS/MS-based widely targeted metabolomics. This research by revealing the effects of different cooking methods on the retention rates of nutrients in D. opposita (e.g., proteins, vitamins, and minerals etc.), provides a scientific basis for healthy consumption of D. opposita. It holds significant theoretical and practical value for enhancing public health, promoting the upgrading of the food industry, and advancing the Healthy China Strategy.

Results

Moisture

The moisture contents of SSCY and LSCY in different culinary treatment including steaming, boiling, roasting and microwaving are shown in Table 1. The results suggested that sandy soil with lower density and higher porosity might increase the water content. Steaming and boiling can provide moisture to food, resulting in higher moisture contents. This might be attributed to food cooked in water or water vapor that penetrated into the food matrix20. Additionally, yams with a high starch content exhibited greater swelling power and water-holding capacity as the temperature increases11. The hot-air roasting and microwaving processes led to a significant reduction in moisture content. In hot-air roasting, food is processed at temperature of 150−200 °C, the moisture on the surface of food is rapidly evaporated, and moisture in center of food migrates to the surface at the same time. The mechanism of microwave cooking is that the heat generates through internal molecular friction and collision inside the foods, as well as extensive heating from the external conduction or convection17. In microwaving, the friction, diffusion and collision of water molecular in foods accelerates, and the bound water could remove by microwave heating. Therefore, the results indicated that hot-air roasting and microwaving evaporate away a large amount of water, which are consistent with previous results that the moisture of yellow yam (Dioscorea cayenensis) decreased after roasting and microwaving21.

Protein

Yams contain about 6.0%−8.0% crude protein, with dioscorin, a storage protein, making up 80%−85% of the soluble protein content22. Yam protein exhibits excellent biological activity including antioxidant, immunological, anti-inflammatory. Generally, the content of protein decreased after cooking, which might be due to the heat treatment causing the dissolution of smaller peptides and amino acids in foods23. Silva do Nascimento et al.24 found that the bioactive peptides generated by the in vitro digestion of yam protein could help prevent bacterial infections and chronic diseases. Cooking often results in the denaturation of proteins and inactivation of protease inhibitors in Chinese yam, making it easily digested and avoiding allergic reactions to specific proteins in the human body.

Reducing sugar

According to our previous study11, the contents of starch in SSCY and LSCY were 64.80 ± 0.96 g/100 g D.W. and 74.60 ± 1.34 g/100 g D.W., respectively. Noda, Kobayashi, and Suda25 suggested that lower soil temperatures significantly impact starch accumulation and its properties. Maintaining consistent temperature in sandy soil can be challenging due to its high porosity, which is why SSCY tends to accumulate less starch compared to LSCY. According to Wang & Zhan26, growing wheat in loam soil can enhance the cultivar’s ability to synthesize starch, with amylose accumulation occurring later than that of amylopectin. The total polysaccharide contents (without starch) of SSCY and LSCY were approximately 3.28 g/100 g D.W. and 2.42 g/100 g D.W., respectively, which were determined by phenol-sulfuric acid method.

The reducing sugar contents were determined by copper reduction methods, and are shown in Table 1. The immediate rise in temperature during cooking inside the tubers could have resulted in the thermo-chemical breakdown of starch and other researchers have also reported the conversion of starch to sugars during microwave cooking and steam heating27,28,29. According to Ogliari et al.30, formation of monosaccharides and disaccharides occurred through the starch decomposition, which could increase the reducing sugar content in yam tuber. However, the reducing sugar contents of LSCY during cooking remained relatively unchanged, which indicated that starch of LSCY were less sensitive to heating. According to our previous study11, the amylose contents of SSCY and LSCY were ~39.72% and 31.57%, respectively. The decomposition of amylose was found to be more facile than that of amylopectin.

Crude fiber

Crude fiber, a polysaccharide abundant in fruits, vegetables and legumes, contains limited nutritional value and is not readily digestible or efficiently utilized by human body. The intake of dietary fiber helps reduce the risk of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and other diseases, thereby promoting overall well-being31. In Table 1, no significant difference was found in crude fiber between SSCY (0.62% ± 0.18%) and LSCY (0.54% ± 0.19%). The contents of crude fiber in SSCY were significantly increased after different cooking treatments, and crude fiber content in LSCY remains constant, indicating that the amylose in yams potentially influenced the nutritional alteration that occurs during the cooking process.

Fat

As shown in Table 1, steaming and microwaving processes significantly reduced the fat content of Chinese yam. Heating could influence the oxidation of fat32, and chemical alterations such as oxidation, thermal decomposition and condensation of lipids in food occurred at temperature exceeding 190 °C33. Steaming proved to be more efficient in lowering fat levels than microwaving, indicating that the moist heat from steaming may promote fat degradation or increase its solubility. In the microwaving process, the electromagnetic waves caused the chemical alterations in yams, decreasing fat content significantly. Unsaturated fatty aldehydes are the main products of fatty acid oxidation, and could be further oxidized to form volatile compounds with shorter carbon chains. According to our previous study, yam tubers decomposed to volatile compositions during heating process, such as acids, ketones, esters, and alcohols etc.34. The oxidation process of unsaturated fatty acids is considered as a typical free radical oxidation reaction. The double bonds in the unsaturated fatty acid could easily produce olefin radicals and hydrogen radicals. They could react with oxygen or peroxyhydroxyl radicals to form peroxyl radicals (ROO·) or peroxides (ROOH), which could be further cleaved to oxidize under heating conditions forming small molecular compounds with shorter carbon chains35.

Ash

Crude ash refers to the inorganic residue of food after heating and the remaining components mainly are the total amount of minerals. Therefore, ash content is one of the vital indicators for accessing the nutritional value of food. As shown in Table 1, the ash contents of SSCY and LSCY were ~2.86% and 3.08%, respectively. Similar values have been reported in previous study on yam flour (Dioscorea alata L)36. The results showed that steaming, hot-air roasting and microwaving increased the ash significantly, and boiling reduced the ash content significantly. The decreases of ash content in B-SSCY and B-LSCY was probably owing to the loss of water-soluble inorganic salts (e.g., Cl-, NO3- and SO42- etc.). Crude ash is closely related with Ca, P, Na, Cl, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn and other inorganic elements. Adepoju et al.37 reported that soaking of food items in water resulted in loss of minerals.

Mineral elements

The content of mineral elements depends on a variety of pre- and post-harvest conditions, including the maturity stage, soil type, and agronomic conditions such as soil composition, fertilization, irrigation, and weather38. Table 2 illustrates the effects of soil environment (sandy soil and loessial soil) on the mineral contents of Chinese yam. The tubers, peels, corresponding soils from top soil (0–20 cm depth) and deep soil (60–100 cm depth) were compared. Generally, the particle size of top soil is smaller than that of deep soil. Sandy soil, opposite of clay soil, is light and porous, whereas loessial soil with high clay content, is slightly sticky and cohesive.

The contents of Mg and Na in LSCY (2.80 mg/g and 1.58 mg/g, respectively) were significantly higher than SSCY (2.50 mg/g and 0.93 mg/g, respectively). Wang et al.39 found that potassium content in the tubers of D. alata was ~11833.23 μg/g D.W., which was lower than K content in D. opposita (14.68 mg/g for SSCY and 15.68 mg/g for LSCY). Therefore, D. opposita could be a better source of potassium for helping to reduce blood pressure and lower the risk of osteoporosis.

The results showed that the most abundant minerals detected in peels of SSCY and LSCY (SSCYP and LSCYP, respectively) were potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium, which were much higher amount of minerals than tubers. The higher mineral content in D. opposita epidermis compared to the fleshy tissue can be explained by multiple physiological and structural mechanisms. As a protective barrier, the epidermis may actively absorb or adsorb minerals. Epidermal cells likely possess more transport proteins (e.g., ion channels and H+-ATPases) that actively transport and store minerals in the epidermis13. The epidermis contains abundant fibrous structures (e.g., cellulose and lignin), which physically adsorb minerals through electrostatic interactions or surface binding. The cuticle and waxy layer secreted by epidermal cells further immobilize soil-derived minerals (e.g., Fe³+, Ca²+), preventing leaching and enhancing mineral retention. During growth, the epidermis directly interfaces with soil minerals. After root absorption, minerals might be preferentially transported to the epidermis as a defense strategy: calcium (Ca), iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) strengthen cell wall rigidity and enhance oxidative stress resistance against pathogens or mechanical damage.

Subsequently, the mineral elements in soils (top and deep) were determined to further understand the relationships among tubers, peels and soils. The results showed that loessial soil contained abundant mineral elements, which significantly higher than sandy soil. According to Tiller et al.40, the particle sizes and clay content showed impacts on soil organic matter content. Although the mineral elements in loessial soil were much greater than sandy soil, the differences in the mineral content of the tubers were not significant. The absorption mechanism of D. opposita might exhibit selectivity, indicating that even in mineral-rich soil, it might only absorb the required amount of minerals. Additionally, as a storage organ, the tuber might have its own regulatory mechanisms to maintain mineral homeostasis. Moreover, yams cultivated in sandy soil might enhance their absorption efficiency by boosting root secretion of organic acids to activate minerals in the soil, thereby compensating for the mineral deficiency characteristic of sandy soils10.

Allantoin

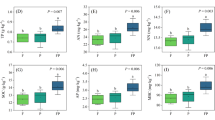

Allantoin is a natural compound with a variety of pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory41, antihypertensive42, antitumor and antioxidant activities5. It has been widely used to evaluate the quality of Chinese yam. Figure 1a showed the effects of different cooking methods on allantoin contents in SSCY and LSCY. The allantoin contents of SSCY and LSCY were ~0.84% and 0.64%, respectively. Compared with raw yam tubers, the allantoin contents increased during steaming and hot-air roasting, and decreased during boiling and microwaving. The observed significant decline in the allantoin content of boiling yams (0.79% for B-SSCY and 0.55% for B-LSCY) was ascribed to the dissolution of allantoin during boiling.

The content of allantoin (a), ascorbic acid (b), polyphenols (c), and flavonoids (d) in raw and processed D. opposita growing from sandy and loessial soils. “*” represent significant differences (P < 0.05) between processed SSCY and raw SSCY. “+” represent significant differences (P < 0.05) between processed LSCY and raw LSCY.

Vitamin C

Ascorbic acid, a well-known vitamin essential for the various functions of the human body43. Additionally, ascorbic acid was used to prevent the enzymatic browning for the fresh-cut yams to improve the nutritional and sensory properties. Figure 1b showed that the contents of ascorbic acid in SSCY and LSCY were 0.092% and 0.095%, respectively, and no significant difference was observed. The results revealed that four different cooking processes increased the ascorbic acid significantly.

However, vitamin C is susceptible to the environment, such as oxygen concentration, temperature, light, pH, water activity and presence of metallic ion44. Thermal treatment was known to be able to accelerate oxidation and degrade ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid (further to 2,3-diketogulanic acid)20. Therefore, the spectrophotometric methods for the determination of ascorbic acid at 245 nm showed the defaults that conjugated-diene, saturated monoene and some other compounds were generated during cooking processes. Besides, according to Jaeschke, Marczak, & Mercali44, the impact of temperature on degradation rate of ascorbic acid was lower than the expected. During the cooking process, the disruption of cell walls releases more vitamin C that was originally less detectable, resulting in an increased measured content. Alternatively, D. opposita might contain substantial amounts of dehydroascorbic acid (a precursor of ascorbic acid), which converts to ascorbic acid under cooking.

Polyphenols and flavonoids

Polyphenols are widely found in most plants, such as nuts, cocoa and tea, which are involved in plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses, and potential health promoting effects (including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor properties)45. The cooking processes induce a reduction in polyphenols attributable to several factors, such as temperature, light, processing conditions, and industrial settings23. Figure 1c exhibits the effects of four different cooking processes on the content of phenolic compounds in SSCY and LSCY. The content of the polyphenols in SSCY and LSCY were 0.257% and 0.183%, and decreased significantly after processing, which indicated that polyphenols were unstable due to the fact that they may undergo chemical and biochemical reactions during food processing and storage.

Flavonoids are common secondary metabolites in vegetables and fruits46. The flavonoid contents of raw and processed Chinese yams are presented in Fig. 1d. SSCY and LSCY contained the relatively low flavonoids (0.07% and 0.04%, respectively). The content of flavonoids increased significantly during cooking, which were consistent with the findings of previous study18.

Total metabolites identification of metabolite analysis

In order to comprehensively understand the compositions of metabolite in D. opposita growing in sandy soil and loessial soil, non-targeted metabolomics analysis were employed to explore the effects of soil types on the metabolites Chinese yam. Totally, 1115 metabolites were identified by UPLC-MS/MS non-targeted metabolomics approach, including 265 lipids, 113 amino acids and derivatives, 96 terpenoids, 78 alkaloids, 75 organic acids, 71 flavonoids, 56 phenols, 56 glycolipids, 44 nucleotides and derivatives, 39 phenolic acids, 37 saccharides, 29 lignans and coumarins, 20 alcohols, 20 vitamins, 17 ketones, 9 quinones, 5 tannins and 85 others (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, the classification and proportions of metabolites in D. opposita including SSCY and LSCY are summarized in Fig. 2a. D. opposita mainly obtained lipids, amino acids and derivatives, terpenoids, alkaloids and organic acids.

Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) were performed to compare the overall differences between SSCY and LSCY. As shown in Fig. 2b, PCA could clearly separate the SSCY and LSCY from the QC samples. Based on the first principal component (PC1, 66.94%) and the second principal component (PC2, 18.83%), the SSCY and LSCY were clearly divided into two categories, suggesting that each group had a distinct metabolite profile. Moreover, the QC samples displayed high clustering, indicating the method had good stability and repeatability.

Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was then performed to find relatively homogeneous clusters of metabolites through a log10 transformation of peak areas (shown in Fig. 2c). D. opposita growing in sandy soil (SSCY) and loessial soil (LSCY) were clearly divided into two classes on the heatmap, indicating significant differences in metabolites, which were consistent with the results of PCA. The results indicated that the significant differences in metabolic profiles might be related to the soil environment of Chinese yam13.

Multivariate analysis of metabolites

A total of 656 differential metabolites were identified between SSCY and LSCY (363 upregulated and 293 downregulated) (Fig. 3), which could be divided into 18 different categories. The differences of the metabolites between SSCY and LSCY were compared, and the upregulated and downregulated metabolites are summarized in Fig. 3b (metabolites in SSCY as control). LSCY significantly increased the contents of 182 primary metabolites, including 122 lipids, 15 nucleotides and derivatives, 28 amino acids and derivatives, and 17 organic acids, as well as 167 secondary metabolites, mainly including 30 flavonoids, 18 alkaloids, 39 terpenoids, 29 glycolipids. Figure 3b showed that lipids (122), terpenoids (39), flavonoids (30), glycolipids (29), and amino acids and derivatives (28) were dominant upregulated differential metabolites in LSCY. These results demonstrate that the metabolites between SSCY and LSCY were significantly different.

Loessial soil, with high clay content, demonstrates strong water and nutrient retention capabilities and high availability of mineral elements such as K, Ca and Fe. However, its compact texture and poor aeration restrict root growth and slow tuber expansion, which might induce the synthesis of stress-responsive secondary metabolites (e.g., lipids and amino). Additionally, the slow decomposition of organic matter in loessial soil facilitates the colonization of specific functional microorganisms (e.g., Actinobacteria), potentially promoting the accumulation of stress-resistant compounds in Chinese yams10,11,13.

Differential metabolite analysis

The 20 differential metabolites with the highest VIP (indicating the contribution of metabolites to the group) of each group were analyzed by hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. 4). Compared with SSCY, LSCY showed the higher significant differences on lipids (Fig. 4a), amino acids and derivatives (Fig. 4b), terpenoids (Fig. 4c), alkaloids (Fig. 4d) and flavonoids (Fig. 4e). The lipids of free fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LysoPE), glycerol ester, and sphingolipids were examined, which showed that the contents of PEG-2, MAG (18:4), PC (20:4/20:5), monoolcin and prostaglandin E1 significant increased when D. opposita were planted in loessial soil. According to Yang et al.13, the contents of the primary metabolites in D. opposita Thunb. cv. Tiegun including free fatty acids, glycerol ester, LysoPE, LysoPC, and sphingolipid were increased significantly, which were the foundation of important functional and biochemical properties of Chinese yam.

Amino acids and derivatives are not only important nutrients for the human body, but also have various pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant, immune stimulation, and anti-inflammatory activities47,48. The Amino acids and derivatives of ELK, L- (+) -Citrulline, Tyr-Tyr, DL-Arginine and L-Pyroglutamic acid were upregulated in LSCY, with 24.43-, 1.87-, 4.12-, 1.93-, and 2.19-fold increments, respectively (Fig. 4b). Elk-1 plays an important role in the regulation of cellular proliferation and apoptosis, thymocyte development, glucose homeostasis and brain function49. Citrulline can be converted into arginine in the body, which could replenish arginine stores and support NO synthesis.

In the process of long-term evolution, plants have produced a large number of secondary metabolites with rich types and variable structures, which are important material bases for plant adaptability and diversity50. Secondary metabolites in medicinal and edible homologous plants serve as vital indicators for evaluating medicinal material quality. Secondary metabolism plays an important role in the adaptation of plants to their environments, particularly by mediating bio-interactions and protecting plants from herbivores, insects, and pathogens3. Terpenoids, flavonoids and alkaloids of plant exhibit prominent medicinal and economic values, such as the well-known anti-malarial drug artemisinin and the narcotic drug morphine. The expression of most terpenoids and flavonoids were increased, especially acoric acid, trillin, paederosidic acid, nobiletin and tangeritin (Fig. 4c and e).

KEGG annotation and enrichment analysis of differential metabolites

To comprehend the effects of soil types on metabolites in D. opposita, the relevant enrichment pathways of 656 differential metabolites was carried out using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. As shown in Fig. 5, 19 primarily metabolic pathways were identified the differences between SSCY and LSCY, which were distributed in “metabolic pathways” (71.15%) and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (68.57%) and “biosynthesis of amino acids” (75.00%). The results revealed that the “purine metabolism”, “histidine and glutathione metabolism”, “lysine and steroid biosynthesis” was significantly enriched, and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, “biosynthesis of amino acids and unsaturated fatty acids” and “phenylpropanoid biosynthesis” were highly enriched. Interestingly, the major metabolic pathways were related to the “biosynthesis of amino acids”.

Purine metabolism plays a critical role in plant growth and development, stress response, and stress tolerance. For instance, the synthesis of purine nucleotides is closely tied to the production of nucleic acids, proteins, and enzymes in plants. Glutathione is a major antioxidant in all forms of life and an indicator of cellular oxidative stress. In its reduced form, glutathione is metabolized in multiple ways, leading to the biosynthesis of mercapturonate, glutamate, glycine, cysteine and other amino acids.

The pathway enrichment of purine metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids, steroid biosynthesis, and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids are closely related with the synthesis of lipids, amino acids and their derivatives, terpenoids, alkaloids and flavonoids in LSCY. Therefore, the difference of soil environment could stimulate the expression of related metabolic and synthesis pathways, which is the primary reason why LSCY exhibits a higher nutritional value compared with SSCY.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of different culinary processes and soil types on the nutrients and metabolites of D. opposita. The results showed that the protein and fat were lost during cooking, but the contents of reducing sugar and ash increased significantly after heating. After four different cooking processes (steaming, boiling, hot-air roasting and microwaving), the contents of phenolic compounds reduced significantly, while the contents of flavonoids increased significantly. No significant difference was found in the mineral elements from SSCY and LSCY, and the most abundant mineral was potassium, indicating that D. opposita could be identified as a potassium-supplementing food. The mineral content in loessial soil was significantly higher than that in sandy soil, which could be fundamental to the nutritional values of LSCY. Further research can be conducted on the contents of various bioactive compositions, including saponin, batatasins, and dioscin etc.

Furthermore, a comprehensive non-targeted metabolomics approach was used to determine the metabolic differences between LSCY with SSCY. The results indicated that soil types had a distinguish influence on the metabolites of D. opposita. The soil environments primarily affected the contents of lipids (24.54%), amino acids and derivatives (9.30%), terpenoids (8.38%), alkaloids (7.16%) and organic acids (5.95%). KEGG analysis revealed that the “metabolic pathways”, “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, “biosynthesis of amino acids, unsaturated fatty acids, and phenylpropanoid” were active when planted the loessial soil. Therefore, the results suggested that cooking methods and soil types (sandy soil and loessial soil) significantly influenced the nutritional components and metabolites in D. opposita on the various basis. Further research on targeted metabolomics across various cooking processes in relation to the prevention of specific diseases is required.

Methods

Materials and chemicals

Fresh Chinese yam (D. opposita) growing in sandy soil (SSCY) and loessial soil (LSCY) were purchased from Bao He Tang (Jiaozuo) Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. in November 2021. Ascorbic acid was purchased from Hubei Xiansheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Allantoin was supplied by J&K Scientific Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Gallic acid and rutin were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. All other reagents were purchased from Aladdin Scientific Corporation. All chemicals used were analytical grade.

Preparation of samples

The fresh Chinese yam from sandy soil (SSCY) was peeled, washed in deionized water, and cut into uniform segments (~3 cm in length), and divided into five groups. One of them remained raw (SSCY) and the rest were cooking in four different methods, including steaming (S-SSCY), boiling (B-SSCY), hot-air roasting (R-SSCY) and microwaving (M-SSCY). Culinary conditions were as follows: ① Steaming: yam samples (500 g/batch) were steamed in a steamer for 20 min; ② Boiling: yam samples (500 g/batch) were boiled in deionized water at 100 °C for 20 min. ③ Hot-air roasting: yam samples (500 g/batch) were roasted in an hot-air fryer (V518-S, Joyoung Co. Ltd., China) at 180 °C for 20 min; ④ Microwaving: yam samples (500 g/batch) were microwaved in a microwave oven (X3-233A, Midea Group Co. Ltd., China) at 900 W for 20 min. After cooling, all yam samples (raw and processed) were sliced (2–3 mm) and oven-dried at 60 °C for 6 h, ground into powder, and stored in vacuum desiccator over P2O5 for further study. Although there is less nutrient loss in powder form, to eliminate the influence of time on nutrient loss, the experiments were completed within a month.

The fresh Chinese yam from loessial soil (LSCY) was carried out as the same processes, and named as LSCY, S-LSCY, B-LSCY, R-LSCY and M-LSCY respectively.

Nutritional compositions

The contents of moisture, protein, reducing sugar, crude fiber, fat, and ash in D. opposita were determined according to Chinese national food safety standards (GB 5009.3-2016, GB 5009.5-2016, GB 5009.7-2016, GB/T 5009.10-2003, GB 5009.6-2016, and GB 5009.4-2016, respectively). The results were expressed as g/100 g dry weight (D.W.).

Mineral elements

The peels of SSCY and LSCY (named SSCYP and LSCYP, respectively) were collected, dried at 50 °C to constant weight and ground into power. The contents of Ca, Mg, K, Na, P, Al and Fe in SSCY and LSCY were determined by Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (NexION 5000 G, PerkinElmer, USA) according to Chinese national food safety standards: Determination of multi-elements in food (GB 5009.268-2016).

During harvesting D. opposita in fields, the corresponding soil from top soil (0–20 cm depth) and deep soil (60–100 cm depth) were collected. The top sandy soil (TSS), top loessial soil (TLS), deep sandy soil (DSS) and deep loessial soil (DLS) were dried at 60 °C and ground into powder. The contents of Ca, Mg, K, Na, P, Al and Fe in soil samples were determined by Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) according to Chinese national environment protection standard: Soil and sediment-determination of 19 total metal elements-Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HJ1315-2023).

Allantoin

Each sample (50 mg) was extracted by ethanol (10 mL) and 15% methanol (10 mL) in conjunction with ultrasonic treatment using a KQ-500DE sonicator (Kunshan Ultrasonic Instruments, Co. Ltd., Kunshan, China) at 50 kHz for 30 min. During the ultrasonic process, the temperature was kept constant by continuously adding ice. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 8000 ×g for 5 min and filtered by a syringe filter (0.45 μm). According to the method described by Liu et al.5, the allantoin content was determined using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260, Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) with an analytical column (Eclipse XDB-C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 0.5 μm, Agilent, USA). Solvents A and B were consisted of water and methanol using a gradient elution of flow rate with 1 mL/min at 35 °C. Linear gradient maintained 10% (B) for 7 min and changed from 10% to 100% in 1 min and keep in 100% for 7 min. The HPLC chromatogram was identified by retention time. The temperature of the column was maintained at 30 °C and detected by VWD at 210 nm.

Total ascorbic acid

Each sample (1.0 g) was extracted with 2 mL solution of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 12 h, and then centrifuged at 10000 ×g for 10 min. The supernatant (1 mL) was mixed with 0.2 mL of DTC reagent (0.4 g thiourea, 0.05 g copper sulfate, 3 g 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, and 90 g sulfuric acid were dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water), heated at 37 °C for 3 h. Then 65% H2SO4 (1.50 mL) was added, and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. Used 10% TCA as the blank sample, and measured the absorbance at 245 nm (TU-1901, Puxi General Instrument, Co. Ltd, Beijing, China).

Total polyphenol

The total polyphenol content of D. opposita was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method according to the method described by Liu et al.4. Briefly, 1.0 g sample was extracted with 30 mL of 70% ethanol for 60 min using a KQ-500DE sonicator (Kunshan Ultrasonic Instruments, Co. Ltd., Kunshan, China). The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 ×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Subsequently, 0.3 mL of supernatant was mixed with 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 2 mL of Na2CO3 (7.5%, w/v). The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (TU-1901, Puxi General Instrument, Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). The total polyphenol was calibrated using the linear equation and expressed as gallic acid equivalent (GAE).

Flavonoids

Flavonoids in D. opposita was measured based on the method described by Guo, et al.18. Each sample (1.0 g) was mixed with 30 mL of 70% ethanol at 50 °C for 120 min, and then centrifuged at 4000 ×g for 10 min. The supernatant was concentrated at 45 °C to 10 mL. The supernatant (2 mL) was mixed with 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrite solution, 0.3 mL of 10% aluminum nitrate solution, and 4.0 mL of 4% sodium hydroxide solution. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm and rutin was used to produce the calibration curve.

Metabolomic analysis

According to Wang et al.51, SSCY and LSCY were peeled, washed in deionized water, and sliced into pieces (2–3 mm). The pieces were freeze-dried to constant weight, ground in a high-speed disintegrator and sifted through a 40-mesh sieve. Samples (100 mg) were individually ground with liquid nitrogen and the homogenate was resuspended with prechilled 80% methanol and 0.1% formic acid by well vortex. The samples were incubated on ice for 5 min and then were centrifuged at 15,000 ×g, 4 °C for 20 min. Some of supernatants were diluted to final concentration containing 53% methanol by LC-MS grade water. The samples were subsequently transferred to a fresh Eppendorf tube and then were centrifuged at 15,000 ×g, 4 °C for 20 min. Finally, the supernatant was injected into the LC-MS/MS system for analysis. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by mixing experimental samples in equal volumes and were analyzed using the instrument before, during, and after the LC-MS/MS injection runs of the experimental samples. The QC prior to injection is used to monitor the instrument status before sample introduction and balance the chromatography-mass spectrometry system. The QC samples inserted during sample detection were employed to evaluate system stability throughout the experimental process and perform data quality control analysis. The QC sample after sample detection underwent segmented scanning, and the secondary spectra obtained from both experimental samples and QC were utilized for metabolite identification. QC samples were prepared by mixing 20 µL each of SSCY and LSCY extracts. QC sample was performed for every three samples to ensure the repeatability of the measurement process.

UHPLC-MS/MS analyses were performed using a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap Q ExactiveTM HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) in Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Samples of 2 μL were injected onto a Hypesil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) using a 17 min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The eluents for the positive polarity mode were eluent A (0.1% formic acid in Water) and eluent B (Methanol). The eluents for the negative polarity mode were eluent A (5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0) and eluent B (Methanol).The solvent gradient was set as follows: 2% B, 1.5 min; 2-100% B, 12.0 min; 100% B, 14.0 min;100-2% B, 14.1 min;2% B, 17 min. Q ExactiveTM HF mass spectrometer was operated in positive/negative polarity mode with spray voltage of 3.2 kV, capillary temperature of 320 °C, sheath gas flow rate of 40 arb and aux gas flow rate of 10 arb.

The data was processed using Compound Discoverer 3.1 (Thermo Fisher Sientific Inc., USA), and the parameters for quantitation of each metabolite were as follows: retention time tolerance, 0.2 min; actual mass tolerance, 5 ppm; signal intensity tolerance, 30%; minimum intensity, 100,000; signal/noise ratio, 3. The data were analyzed by mzCloud, mzVault and Masslist database. Metabolite identification was performed utilizing the public metabolites databases including HMDB (https://www.hmdb.ca/), PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and MassBank (https://www.massbank.jp/).

Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed at metaX (a flexible and comprehensive software for processing metabolomics data). The data were unit variance scaled (also known as Z-score normalization/auto-scaling). This method standardizes the data of SSCY and LSCY metabolites, according to the mean and standard deviation of the original data. The processed data accord with the standard normal distribution, that is, the mean value is 0 and the standard deviation is 1. We applied univariate analysis (t-test) to calculate the statistical significance (P-value). The metabolites with VIP > 1 and P-value < 0.05 and fold change ≥ 2 or FC ≤ 0.5 were considered to be differential metabolites. Volcano plots were used to filter metabolites of interest which based on log2 (Fold Change) and -log10 (P-value) of metabolites by ggplot2 in R language. The differential metabolites between SSCY and LSCY were annotated using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Compound database (http://www.kegg. jp/kegg/compound/), and then, the annotated metabolites were mapped to the KEGG Pathway database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/pathway.html) to obtain detailed pathway information. Pathways with significantly regulated metabolites were subjected to metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA). The P-values from the hypergeometric tests were used to assess their significance.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and each sample was performed at least three repeated determinations, and the results were presented as the mean values ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Duncan’s multiple-range tests (P < 0.05) were conducted to determine the significant differences among mean values.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Abiodun, O. A., Adegbite, J. A. & Oladipo, T. S. Effect of soaking time on the pasting properties of two cultivars of Trifoliate yam (Dioscorea dumetorum) flours. Pak. J. Nutr. 8, 1537–1539 (2009).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Crops and Livestock Products. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Chinese yam (Dioscorea): nutritional value, beneficial effects, and food and pharmaceutical applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 134, 29–40 (2023).

Kamal, M. M., Ali, M. R., Shishir, M. R. I. & Mondal, S. C. Thin-layer drying kinetics of yam slices, physicochemical, and functional attributes of yam flour. J. Food Process Eng. 43, 13448 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Antioxidant and antitumor activities of the extracts from chinese yam (Dioscorea opposite Thunb.) flesh and peel and the effective compounds. J. Food Sci. 81, 1553–1564 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Isolation, characterization and antioxidant activity of yam polysaccharides. Foods 11, 800 (2022).

Wang, X., Huo, X., Liu, Z., Yang, R. & Zeng, H. Investigations on the anti-aging activity of polysaccharides from Chinese yam and their regulation on klotho gene expression in mice. J. Mol. Struct. 1208, 127895 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Dioscin’s antiviral effect in vitro. Virus Res. 172, 9–14 (2013).

Ma, F. et al. Polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita Thunb.: isolation, structural characterization, and anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects against hepatocellular carcinoma. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agri. 10, 43 (2023).

Li, Q., Li, W., Gao, Q. & Zou, Y. Hypoglycemic effect of Chinese Yam (Dioscorea opposita rhizoma) Polysaccharide in different structure and molecular weight. J. Food Sci. 82, 2487–2494 (2017).

Ma, F. et al. Characterisation comparison of polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita thunb. growing in sandy soil, loessial soil and continuous cropping. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 776–785 (2019).

Bambina, P. et al. 1H NMR-based metabolomics to assess the impact of soil type on the chemical composition of Nero d’Avola red wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 5823–5835 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Widely targeted metabolomics reveals the effects of soil on the metabolites in Dioscorea opposita thunb. Molecules 28, 4925 (2023).

Huang, F., Hu, B., Cheng, F. & Wang, H. Analysis on heavy metal pollution of soil and rhizome Dioscorea in Wenxian Jiaozuo (Chinese). J. Henan Polytech. Univ. 28, 123–126 (2009).

Téllez-Morales, J. A., Rodríguez-Miranda, J. & Aguilar-Garay, R. Review of the influence of hot air frying on food quality. Meas.: Food 14, 100153 (2024).

Zhou, S., Chen, W. & Fan, K. Recent advances in combined ultrasound and microwave treatment for improving food processing efficiency and quality: a review. Food Biosci. 58, 103683 (2024).

Yi, M. et al. Effect of microwave alone and microwave-assisted modification on the physicochemical properties of starch and its application in food. Food Chem. 446, 138841 (2024).

Guo, C. et al. Influence of different cooking methods on the nutritional and potentially harmful components of peanuts. Food Chem. 316, 126269 (2020).

Roncero-Ramos, I., Mendiola-Lanao, M., Perez-Clavijo, M. & Delgado-Andrade, C. Effect of different cooking methods on nutritional value and antioxidant activity of cultivated mushrooms. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 68, 287–297 (2017).

Xu, F. et al. Domestic cooking methods affect the nutritional quality of red cabbage. Food Chem. 161, 162–167 (2014).

Adepoju, O. T., Boyejo, O. & Adeniji, P. O. Effects of processing methods on nutrient and antinutrient composition of yellow yam (Dioscorea cayenensis) products. Food Chem. 238, 160–165 (2018).

Lu, J. et al. Yam protein ameliorates cyclophosphamide-induced intestinal immunosuppression by regulating gut microbiota and its metabolites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 279, 135415 (2024).

García-Herrera, P. et al. Nutritional and phytochemical composition of mediterranean wild vegetables after culinary treatment. Foods 9, 1761 (2020).

Silva do Nascimento, E. et al. Identiffcation of bioactive peptides released from in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of yam proteins (Dioscorea cayennensis). Food Res. Int. 143, 110286 (2021).

Noda, T., Kobayashi, T. & Suda, I. Effect of soil temperature on starch properties of sweet potatoes. Carbohydr. Polym. 44, 239–246 (2001).

Wang, W. & Zhan, H. Effect of soil texture on starch accumulation and activities of key enzymes of starch synthesis in the kernel of ZM9023. Agri.Sci. China 7, 686–691 (2008).

Raigond, P. et al. Composition of different carbohydrate fractions in potatoes: Effect of cooking and cooling. StarchStärke 73, 2100015 (2021).

Singh, A. et al. Effect of cooking methods on glycemic index and in vitro bioaccessibility of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) carbohydrates. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 127, 109363 (2020).

Lewthwaite, S. L., Sutton, K. H. & Triggs, C. M. Free sugar composition of sweet potato cultivars after storage. N.Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 25, 33–41 (1997).

Ogliari, R. et al. Chemical, nutritional and sensory characterization of sweet potato submitted to different cooking methods. Int. J. Res. GRANTHAALAYAH 8, 147–156 (2020).

Barber, T. M., Kabisch, S., Pfeiffer, A. F. H. & Weickert, M. O. The health benefits of dietary fibre. Nutrients 12, 3209 (2020).

Offem, J. O., Egbe, E. O. & Onen, A. I. Changes in lipid content and composition during germination of groundnuts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 62, 147–155 (1993).

Liu, W. et al. Influence of cooking techniques on food quality, digestibility, and health risks regarding lipid oxidation. Food Res. Int. 167, 112685 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of Maillard reaction products derived from Dioscorea opposita polysaccharides. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 149, 111833 (2021).

De Dios Miguel, T., Duc Vu, N., Lemaire, M. & Duguet, N. Biobased aldehydes from fatty epoxides through thermal cleavage of β-hydroxy hydroperoxides. ChemSusChem 14, 379–386 (2020).

Yalindua, A., Manampiring, N., Waworuntu, F. & Yalindua, F. Y. Physico-chemical exploration of yam flour (Dioscorea alata L.) as a raw material for processed cookies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1968, 012004 (2021).

Adepoju, O. T., Adekola, Y. G., Mustapha, S. O. & Ogunola, S. I. Effect of processing methods on nutrient retention and contribution of cassava (manihot spp) to nutrient intake of Nigerian consumers. Afr. J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 10, 2099–2111 (2010).

Jayanty, S. S., Diganta, K. & Raven, B. Effects of cooking methods on nutritional content in potato tubers. Am. J. Potato Res. 96, 183–194 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of functional components, biological activities, and minerals of yam species (Dioscorea polystachya and D. alata) from China. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 168, 113964 (2022).

Tiller, M., Reading, L., Dawes, L., Miska, M. & Egodawatta, P. Effects of particle size fractions and clay content for determination of soil organic carbon and soil organic matter. Soil Tillage Res. 252, 106568 (2025).

Florentino, I. F. et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Memora nodosa and allantoin in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 186, 298–304 (2016).

Chen, M. F. et al. Antihypertensive action of allantoin in animals. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 690135 (2014).

Zhao, X. et al. Ascorbic acid prevents yellowing of fresh-cut yam by regulating pigment biosynthesis and energy metabolism. Food Res. Int. 157, 111424 (2022).

Jaeschke, D. P., Marczak, L. D. F. & Mercali, G. D. Evaluation of non-thermal effects of electricity on ascorbic acid and carotenoid degradation in acerola pulp during ohmic heating. Food Chem. 199, 128–134 (2016).

De Lana, V. S. et al. Impact of processing on polyphonols content in food: a nutritional and statistical analysis of Brazilian menus. Food Res. Int. 196, 115115 (2024).

Cao, Y. et al. The antihypertensive potential of flavonoids from Chinese herbal medicine: a review. Pharmacol. Res. 174, 105919 (2021).

Iordache, A. M. et al. Comparative amino acid profile and antioxidant activity in sixteen plant extracts from transylvania, romania. Plants 12, 103390 (2023).

Zhang, H., Lu, Q. & Liu, R. Widely targeted metabolomics analysis reveals the effect of fermentation on the chemical composition of bee pollen. Food Chem. 375, 131908 (2022).

Thiel, G., Backes, T. M., Guethlein, L. A. & Rössler, O. G. Critical protein-protein interactions determine the biological activity of Elk-1, a master regulator of stimulus-induced gene transcription. Molecules 26, 103390 (2021).

An, L. et al. Comprehensive widely targeted metabolomics to decipher the molecular mechanisms of Dioscorea opposita thunb. cv. Tiegun quality formation during harvest. Food Chem. X 21, 101159 (2024).

Want, E. et al. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat. Protoc. 8, 17–32 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by [Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province] [grant number: 232301420099]; [Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project] [grant number: 242102310442]; [Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province] [grant number: 252300420164]; [Foundation of Educational Committee of Henan Province] [grant number: 24A550001]. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Zhang: Investigation, Writing-review & editing; X. Sun: Investigation, Writing-original draft; A. Lu: Formal analysis; J. Lai: Investigation, Formal analysis; Y. Yang: Data curation; J. Zhang: Funding acquisition, Supervision; A. E. Jaouhari: Formal analysis, Methology; J. Zhu: Funding acquisition, Resources; F. Ma: Conceptualization, Project Administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Sun, X., Lu, A. et al. Effects of different cooking methods and soil environment on the nutrition of Dioscorea opposita Thunb. npj Sci Food 9, 128 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00499-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00499-4