Abstract

Fish sauce is a popular aquatic condiment with a unique flavor. This study aims to efficiently prepare a no-salt-added fish sauce from yellowfin tuna dark meat and characterize its flavor profiles. The enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation conditions in preparing fish sauce were optimized first based on single-factor and response surface experiments. The fish sauce obtained had an amino acid nitrogen content of 0.603 g/100 mL and a salt content of 0.128%, and showed favorable improvement in appearance, odor, and taste. HS-GC-IMS analysis revealed that more esters with pleasant aromas and fewer aldehydes with fishy odors were produced during fish sauce processing. Furthermore, two potential umami peptides were identified from fish sauce through LC–MS/MS and virtual screening, both of which were embedded within the T1R1 subunit via hydrogen bonding. These results provide a theoretical basis for the efficient production of no-salt-added fish sauce and high-value utilization of yellowfin tuna dark meat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fish sauce is a traditional aquatic condiment with a clear amber-colored liquid1. Due to its unique aroma, umami, and high nutritional value, fish sauce has been widely consumed in Asia and gradually accepted worldwide2. Traditional fish sauce is usually made by mixing fish with salt at a 2:1 or 3:1 (w/w) ratio, and then fermenting for 9–24 months3. The osmotic effect of high salinity kills or suppresses spoilage microorganisms but also inhibits the metabolic activity of other microorganisms, causing them to take longer to establish their dominance4. During a long fermentation period, endogenous enzymes and halophilic microorganisms break down the proteins and lipids of fish through various metabolic pathways, contributing to the specific flavor of fish sauce5. Considering the long fermentation period of the traditional fermentation process5 and the health risks posed to consumers by high salt content6, there is a pressing need for the development of a no-salt-added fish sauce with a shorter preparation cycle.

Several rapid-preparation methods, such as adding exogenous enzymes and inoculating microbial starters, have been explored to accelerate the fish sauce fermentation process while reducing the amount of salt added1,4,7,8. The anchovy fish sauce with an addition of 20% salt (w/w) was successfully prepared by enzymatic hydrolysis with a compound enzyme, followed by natural fermentation for 7 months8, of which the natural fermentation process was shortened. Moreover, fish sauce made from blue round scad was fermented by Tetragenococcus muriaticus for 45 days with an addition of 18% salt (w/w)4. These rapid-preparation methods could reduce the fermentation time to some extent, but most of the total fermentation process still took over 10 days3,7. Notably, Gao et al.2 prepared a no-salt-added fish sauce by first hydrolyzing tilapia fish heads with flavourzyme for 3 h, followed by inoculation with Kluyveromyces marxianus for a 7-day fermentation. Likewise, inoculating Aspergillus oryzae after enzymatic hydrolysis could shorten the fermentation time of no-salt-added anchovy fish sauce to 3 days9. These studies suggest that a combination of enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial inoculation would be an appropriate choice to accelerate the processing of no-salt-added fish sauce further.

Aroma is one of the key quality parameters to control when developing fish sauce products, as it plays a vital role in shaping the overall flavor of fermented foods10. Traditional fish sauce normally takes a long time to ensure aroma development. Due to the strong ability of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) to convert amino acids and fatty acids into multiple volatile metabolites, aroma modification by LAB fermentation can compensate for the shortcomings in the aroma of rapidly prepared fish sauce11. The fish sauce inoculated with Lactobacillus fermentum yielded higher levels of aromatic compounds like alcohols and esters than those without inoculation12. Similar results were observed in mackerel seasoning fermented with Latilactobacillus sakei5. These studies indicated that initial hydrolysis of fish protein by adding exogenous enzymes, followed by inoculating LAB for fermentation, may be a better option to achieve the desired protein degradation effect and ameliorate the aroma of fish sauce within a short time.

Umami is an outstanding characteristic taste of fish sauce11. In general, umami is not only produced from umami molecules like organic acids, nucleotides, and amino acids but also from peptides13. Among them, the umami taste of peptides is induced by binding to umami receptors, with the heterodimer T1R1/T1R3 being the primary receptor for the umami taste signals13. At present, varieties of umami peptides, such as KEVKEEPAEAVGD from Chouguiyu14, DGV from dry-cured Spanish mackerels15, and four peptides from fermented Atlantic cod16, have been found in fermented fish products except fish sauce, which supports that umami peptides contribute significantly to the umami taste of fermented fish products. Although umami compounds in fish sauce have been investigated previously, among which are exclusive to organic acids, amino acids, and nucleotides7,11,12, research on the umami presentation mechanism of fish sauce from the perspective of umami peptides is still limited.

Yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) is a significant component of global fish and seafood resources due to its economic and nutritional values17. The processing of yellowfin tuna generates many by-products, of which dark meat is one of the most important by-products18,19. Dark meat generally amounts to 5.8–6.8% of yellowfin tuna’s body weight and is usually discarded, causing environmental pollution and resource waste18. Currently, several studies have reported fish sauce production using fish by-products (bone, head, and roes)1,12,20. Dark meat contains rich protein and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which can be recovered to prepare fish sauce for human consumption19. Thus, this study selected yellowfin tuna dark meat as the raw material for the rapid preparation of no-salt-added fish sauce. The process parameters of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation were optimized using single-factor and response surface experiments, and the aroma profiles and possible umami presentation mechanism of fish sauce were further explored. Our findings could provide theoretical guidance for the efficient processing of no-salt-added fish sauce and the comprehensive utilization of tuna by-products.

Results and discussion

Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis conditions

Regarding the influence of enzyme dosage on the degree of hydrolysis (DH) of yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate, five distinct dosages: 2%, 2.4%, 2.8%, 3.2%, and 3.6% were studied. During this process, all other parameters were kept constant, including the temperature of 55 °C and pH of 7.5. As shown in Fig. 1A, the DH of yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate significantly increased with increasing enzyme dosage from 2% to 2.8% (P < 0.05). However, DH equilibrated at higher enzyme dosages (2.8–3.6%, P > 0.05), which may be due to the protein being fully utilized by the enzyme at a certain enzyme dose, causing only a slight increase in DH21.

A Effect of enzyme dosage on DH. B Effect of pH on DH. C Effect of temperature on DH. D Response surface plot of DH in terms of enzyme dosage vs. pH. E Response surface plot of DH in terms of enzyme dosage vs. temperature. F Response surface plot of DH in terms of pH vs. temperature. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM in each group (n = 3). Means with different letters differ significantly at P < 0.05.

In the case of pH, five values (6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, and 8.5) were examined. Other parameters, including an enzyme dosage of 2.8% and a temperature of 55 °C, remained unchanged. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, DH increased with an increase in pH from 6.5 to 8 (P < 0.05), followed by a significant decrease as pH was further increased to 8.5 (P < 0.05). pH will affect the rate of enzymatic hydrolysis by influencing protease activity 22. Thus, trypsin activity was limited when the pH increased beyond the optimal pH (7.0–8.0), leading to a decrease in DH23.

In investigating the effect of temperature on DH, five values (45, 50, 55, 60, and 65 °C) were examined. During these experiments, other parameters, including enzyme dosage (2.8%) and pH (7.5), were kept constant. DH significantly grew when the temperature was raised from 45 to 55 °C (P < 0.05) and then sharply declined with the increasing temperature (P < 0.05, Fig. 1C). This decrease in DH is due to excessively high temperatures, which are not conducive to enzyme activity21. Thus, enzyme dosages of 2.4%, 2.8%, and 3.2%; pH of 7.5, 8, and 8.5; and temperatures of 50, 55, and 60 °C were selected for the subsequent experiments.

The RSM method was adopted to further determine the optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions, and the influences of enzyme dosage (X1), pH (X2), and temperature (X3) on the DH of yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate were shown in Table 1. The quadratic model expression for the response DH was presented as follows:

The results of an ANOVA test of this model are shown in Table S1. The model’s correlation coefficient (R2) was 0.9813, a P-value of the model < 0.0001, and the lack of fit term was insignificant, indicating that the model was reasonable and available for predicting DH. 3D surfaces of interactive effects of enzyme dosage, pH, and temperature on the DH are illustrated in Fig. 1D and E. The model-predicted enzymatic hydrolysis conditions that maximized DH to optimal values (47.912%) were enzyme dosage of 3.2%, pH at 8.3, and temperature of 53.3 °C. The actual measured value of DH obtained at optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions was 47.878 ± 0.16%, which was comparable to the predicted value generated by the model. These results indicated that the optimized model can be successfully applied to predict the DH of the actual enzymatic hydrolysis process. The enzyme dosage of 3.2%, pH at 8.3, and temperature of 53.3 °C were used for further experiments.

Optimization of fermentation conditions

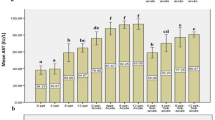

The effect of glucose dosage (0.1–1.9%) on the amino acid nitrogen (AA-N) content of fish sauce was first investigated, while the inoculation size and fermentation time were kept at 5% and 5 days, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A, there was an obvious increase in AA-N content as glucose dosage increased from 0.1% to 1.3% (P < 0.05). Subsequently, the increasing glucose dosage (1.3–1.9%, P < 0.05) sharply decreased the AA-N content. The adequate addition of glucose provided sufficient energy for the growth and metabolism of L. fermentum, but excessive glucose led to high osmotic pressure in the fermented solution and thus inhibited the growth of L. fermentum24.

A Effect of glucose dosage on AA-N content. B Effect of inoculation size on AA-N content. C Effect of fermentation time on AA-N content. D Response surface plot of AA-N content in terms of glucose dosage vs inoculation size. E Response surface plot of AA-N content in terms of glucose dosage vs. fermentation time. F Response surface plot of AA-N content in terms of inoculation size vs. fermentation time. G Changes of TVC during the fermentation process. H Changes of pH during the fermentation process. I Changes in the total acid content during the fermentation process. J Changes of TS-N content during the fermentation process. K Changes of AA-N content during the fermentation process. L Changes of TVB-N content during the fermentation process. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM in each group (n = 3). Means with different letters differ significantly at P < 0.05.

The effect of different inoculation sizes (2–8%) on the AA-N content of fish sauce was investigated at the following fixed conditions: glucose dosage of 1.0%, and fermentation time of 5 days. In Fig. 2B, the AA-N content increased slowly as the inoculation size was increased from 2% to 5% (P < 0.05) and then decreased as the inoculation size was further increased to 8% (P < 0.05). The excessive inoculation size would lead to rapid nutrient consumption by L. fermentum in the early fermentation stage, inhibiting its growth and metabolism in the later stages, which was not conducive to the release of AA-N25.

The effect of different fermentation times (1–7 days) on the AA-N content of fish sauce was investigated at a glucose dosage of 1.0% and inoculation size of 5%. The AA-N content raised from 0.369 ± 0.002 to 0.453 ± 0.002 g/100 mL as the fermentation time was increased from 1 to 4 days (P < 0.05, Fig. 2C). With the further extension of fermentation time, the AA-N content significantly reduced to 0.97-fold, 0.96-fold, and 0.95-fold of the maximum value on the 4th day (P < 0.05), since the small peptides and free amino acids in fish sauce were further decomposed into nitrogen oxides26. Thus, glucose dosages of 1%, 1.3%, and 1.6%; inoculation sizes of 4%, 5%, and 6%; and fermentation times of 3–5 days were selected for the subsequent experiments.

A Box-Behnken design with three factors and three levels was further used to determine the optimal fermentation conditions for fish sauce to obtain the highest AA-N content (Table 2). The regression equation for AA-N content to three different fermentation parameters, glucose dosage (X1), inoculation size (X2), and fermentation time (X3), was as follows:

The ANOVA was used to estimate the significance of the fit of the quadratic multiple regression equation for the experimental data (Table S2). The R2 and R2adj values of the fitted model were 0.9738 and 0.9401, respectively. Meanwhile, the F-value of the model was 28.91 with a P-value < 0.0001, and the lack of fit was not significant, indicating that the model with a better fit was stable and statistically significant. The 3D response surface plots (Fig. 2D–F) were generated using the full model resulting from the regression equation. Based on the results of response surface fitting, the optimal fermentation conditions were determined to be: glucose dosage of 1.02%, inoculation size of 5.99%, and time of 4.68 days. Under these conditions, the AA-N content was measured to be 0.603 ± 0.036 g/100 mL, which closely approximated the theoretical value (0.604 g/100 mL). These findings demonstrated that the fermentation conditions derived through response surface optimization are accurate and reliable.

Changes in chemical properties during fermentation

To further study the mechanism of L. fermentum fermentation of fish sauce, the dynamic changes of chemical properties, including total viable count (TVC), pH, total soluble nitrogen (TS-N), total acid, AA-N, and total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N), were studied under optimal fermentation conditions.

The Changes in TVC of L. fermentum during the fermentation are shown in Fig. 2G. The TVC of L. fermentum exhibited a significant increase from the initial 7.05 lg CFU/mL to 7.82 lg CFU/mL (the maximum value) after 1-day fermentation (P < 0.05). During the prolonged fermentation to 4.68th day, the TVC decreased to 0.89-fold, 0.87-fold, 0.83-fold, and 0.83-fold of the maximum value (7.82 lg CFU/mL, 1st day) at the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 4.68th day (P < 0.05). This indicated that the inoculated L. fermentum went through logarithmic, stationary, and decline phases during the fermentation process of fish sauce27. In the early stages of fermentation, L. fermentum adapted to the living environment over time, along with sufficient and suitable nutrients for microbial growth, resulting in a sharp increase in TVC28. In the later stages, the depletion of nutrients and/or metabolic by-products that accumulate in the fermentation environment may be responsible for the decrease in TVC of L. fermentum over time29.

The growth and metabolism of microorganisms are closely associated with changes in pH and total acid content, which eventually influence the flavor of fish sauce30. As can be seen in Fig. 2H, I, the total acid content in fish sauce increased significantly from day 0 to day 1 (P < 0.05), while the pH value decreased significantly (P < 0.05). Those acids were primarily made up of lactic acid and other acids generated by L. fermentum12. Even though protein degradation during fermentation may be accompanied by the production of small amounts of alkaline substances (e.g., TVB-N, produced by amino acid deamidation), these alkaline substances quickly combine with organic acids in the fermentation broth to form ammonium salts (e.g., ammonium lactate), which cannot raise the pH significantly31. Therefore, the accumulation of acids ultimately dominates the pH decrease. The fermentation broth was somewhat acidic owing to the accumulation of acids from 2 to 4.68 days of fermentation, which might inhibit microbial activity 32, leading to slower changes in the magnitude of the total acid content and pH (P < 0.05). This trend was similar to the previous studies on the fermentation process of fish sauce prepared from channel catfish bone20. The pH dropped to a minimum value of 4.57 ± 0.01, and the total acid rose to a maximum value of 2.50 ± 0.02 g/L at 4.68 days of fermentation, giving fish sauce a rich flavor.

The TS-N content is one of the crucial components in determining the quality of fish sauce30, and the AA-N content reflects the degree of protein hydrolysis during the fermentation process of fish sauce7. The TS-N and AA-N contents in the fish sauce gradually increased during fermentation (P < 0.05, Fig. 2J, K) due to the extracellular proteases secreted by microorganisms33. The Chinese national standards for fish sauce (GB/T 42463-2023) state that the TS-N and AA-N contents in the qualified fish sauce product must be higher than 0.5 g/100 mL and 0.4 g/100 mL, respectively. At the end of 4.68 days of fermentation, the contents of TS-N and AA-N in fish sauce reached the maximum values of 0.99 ± 0.01 g/100 mL and 0.60 ± 0.01 g/100 mL, respectively, which met the standard of commercial fish sauce.

TVB-N is an alkaline nitrogen-containing substance generated in animal foods due to protein degradation by endogenous enzymes and specific spoilage bacteria during the process of corruption34. TVB-N is widely recognized as an important indicator of seafood freshness and spoilage, with higher TVB-N values indicating higher levels of corruption35. The initial TVB-N content in fish sauce was 21.00 ± 2.80 mg/100 mL, and the content gradually increased to 58.53 ± 1.47 mg/100 mL in 4.68 days (P < 0.05, Fig. 2L). The results of this study further confirmed previous studies that fermentation resulted in increased TVB-N1,33. The TVB-N content of sardine fish sauce after 180 days of fermentation was 4.08 times higher than before fermentation7. Moreover, the TVB-N contents of shrimp sauce and Iranian fish sauce produced through traditional fermentation were 236.27 and 266.2 mg/100 mL, respectively33,36. In this study, the TVB-N content in rapidly prepared fish sauce was considerably lower than that of these traditionally fermented fish sauces, indicating their higher freshness and safety. These results further suggest that the combination of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation with LAB is of great value in the rapid preparation process of fish sauce.

Salt content of fish sauce

The salt content in fish sauce at the end of fermentation was determined to be 0.128 ± 0.004% (data not shown). The salt content of Budu, a Malaysian commercial fish sauce made by traditional fermentation of anchovy for 12 months, was detected to be 21.7%37. Likewise, the salt content of the Korean traditional fermented fish sauce was reported to be 25%. In addition, two low-salt fish sauces (<20% salt) were made from silver pomfret and blue round cod with 15% and 18% salt added, respectively38,39. The shorter preparation cycle eliminates the need for adding salt to prevent the growth of spoilage microorganisms, contributing to the lower salt content of rapidly prepared fish sauce than traditional commercial fish sauce and low-salt fish sauce. More importantly, the WHO recommends a salt intake of no more than 5 g (approximately 2 g sodium) per person per day for adults6 because of the health risks posed to consumers by high salt content. The lower salt content makes the rapidly prepared fish sauce produced from yellowfin tuna dark meat more consistent with healthy dietary requirements5.

Sensory evaluation

In terms of appearance, the FS group was clearer and had a darker brown color compared to the control and FH groups (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B shows the sensory descriptive characteristics of the control, FH, and FS groups based on the QDA test. The brown color, aroma, caramel, sour, and umami scores obtained by the FS group were relatively high, while the ammonia, rancid, fishy, and bitter scores were relatively low. The increased sour score of the FS group was attributed to the accumulation of organic acids during carbohydrate metabolism in L. fermentum40. The developed sour further masked the bitterness caused by the enzymatic hydrolysis of dark meat proteins, resulting in a diminished bitter score of the FS group40. The anchovy fish sauce, rapidly prepared by enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae, still retained a certain fishy smell9. It is noteworthy that the fishy smell of the FS group improved considerably during the fermentation process with L. fermentum, compensating for the rapid fermentation’s inability to eliminate undesirable odors5. These results suggested that the FS group showed favorable appearance, odor, and taste improvement after enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, and was overall satisfactory.

A Pictures of control, FH, and FS groups. B Sensory profiles of control, FH, and FS groups. Control: the yellowfin tuna dark meat–water mixture without enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation treatment, FH: the yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions, FS: the fish sauce prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation conditions.

HS-GC-IMS spectrum analysis of fish sauce

HS-GC-IMS, an emerging technique for food flavor analysis, has gained popularity due to its high sensitivity, fast response, and visually distinguishing variations41. In the present study, HS-GC-IMS was used to compare the differences in volatile organic compounds (VOCs) among the control, FH, and FS groups to further understand the flavor formation mechanism in the fish sauce during enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation with LAB. From the 3D-topographic plot in Fig. 4A, the VOCs of the three groups exhibited large differences. In Fig. 4B, the total VOCs of the three groups have been plotted as a 2D vertical view spectrum for better horizontal comparison. The differential spectra (Fig. 4C) of other groups were obtained by subtracting the spectrum of the control group as a reference. The concentration of some VOCs decreased in the FH group compared to the control group, which may be because some VOCs were unstable in a heated environment and tended to decompose during enzymatic hydrolysis42. More red dots were present in the FS group than in the FH group, indicating that more VOCs were produced in the FS group after fermentation. In addition, there was a decrease in the concentration of some other VOCs, which might be attributed to the fact that fermentation can eliminate the bad flavor of food43,44.

A The 3D-topographic plots. B The 2D-topographic plots (vertical view). C The 2D-topographic plots (difference view). D The gallery plot fingerprint spectra (“M” and “D” indicated monomers and dimers of the same compound, and the numbered peaks indicated unidentified peaks). E–K Heatmap visualization of the volatile compounds in different groups. L The PCA analysis plot. Control: the yellowfin tuna dark meat–water mixture without enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation treatment, FH: the yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions, FS: the fish sauce prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation conditions.

Comparative analysis of HS-GC-IMS fingerprints of fish sauce

The gallery plot was utilized to quantitatively characterize VOCs (Fig. 4D). A total of 105 VOCs (excluded dimer) were detected, all showing response signals in all three groups but at different levels. 83 VOCs (excluded dimer) were identified by matching with the database, and the remaining 22 VOCs cannot be fully identified due to database limitations. The identified VOCs were classified into 9 categories as follows: aldehydes (20), esters (15), alcohols (12), ketones (14), acids (4), pyrazines (3), furans (4), hydrocarbons (9) and others (3) (Table S3).

Aldehydes are thought to contribute to the fishy taste of aquatic products owing to their low thresholds45. After enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, the concentrations of (E)-2-octenal, nonanal, octanal, hexanal, pentanal, acrolein, (E)-2-heptanol, and (E)-2-pentenal decreased greatly (Fig. 4E). Among them, hexanal, octanal, and nonanal were also detected in yellowfin tuna surimi as fishy odor VOCs46. Heptanal is known to exert a greasy, spicy, and musty odor at a high concentration. The large amounts of heptanal found in Agaricus blazei fish soup resulted in a lower “Smell” score than that received by other edible fungi fish soups47. (E)-2-octenal, acrolein, (E)-2-heptenal, and (E)-2-pentenal were described as having a fatty, fishy, grassy, and offensive odor, respectively48. These results suggested that the combination of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation showed a strong capacity to reduce some specific aldehydes associated with the unpleasant odor of fish sauce. Interestingly, the methional content was considerably higher in the FS group than in the other two groups. Methional was reported to act as a positive allosteric modulator of human umami taste receptor T1R1/T1R349, and was also detected in steamed sturgeon meat50. A notable elevation of methional content was detected for the first time in this study during the preparation of fish sauce, which may promote the expression of fresh flavor in fish sauce.

Esters impart a desirable fruity taste to meat products and are usually produced by the non-enzymatic esterification of alcohols and organic acids or by enzymatic catalysis mediated by microorganisms51. As shown in Fig. 4F, most ester compounds in the FS group increased greatly after fermentation. Likewise, fish sauce made from Nile tilapia fish head inoculated with L. fermentum produced relatively higher levels of esters after fermentation12, suggesting esters contribute to the unique flavor of fish sauce. The increase in esters was critical in forming the refreshing and pleasant aroma of fish sauce, which can effectively mask the rotten odor of fermented fish products43, thereby contributing to the high sensory acceptability of the FS group.

Alcohol compounds are generated by the oxidative decomposition of oils and fats42. 3-methyl-1-butanol and 2-ethyl-1-hexanol are known for their malty and floral notes, respectively, while 1,8-cineole possesses a camphor and cool herbal note52,53. Their levels were greatly increased in the FS group compared to the FH group, revealing that L. fermentum fermentation increased 3-methyl-1-butanol, 1,8-cineole, and 2-ethyl-1-hexanol levels (Fig. 4G). An increase in 3-methyl-1-butanol was also detected in sea bass after 20 days of fermentation53. Alcohols were found in various fish sauces but had little impact on the overall flavor of fish sauce, owing to their generally high thresholds4,12,20.

Ketones are mainly produced by amino acid degradation or unsaturated fatty acid oxidation41. A total of 14 ketones were identified in this study, with a substantial decrease in 1-octen-3-one in the FS group (Fig. 4H). 1-octen-3-one possesses an earth and mushroom flavor and has been recognized as an odor-causing compound associated with fishy odor54. Furthermore, the signal intensity of 4-methyl-2-pentanone was considerably higher in the FS group than in the control and FH groups, which may be responsible for the characteristic flavor of milk and sweet butter in fish sauce3.

Hydrocarbons are produced from alkyl radicals through lipid auto-oxidation processes20. Although nine hydrocarbons were identified in all three groups (Fig. 4I), their contribution to the characteristic flavor of fish sauce may be limited owing to their high thresholds. Volatile acid compounds, including pentanoic acid, propionic acid, 2-methylpropanoic acid, and acetic acid, were detected in the control, FH, and FS groups (Fig. 4J). The content of these acids showed a significant increase after fermentation, reaching their maximum value in the FS group. Likewise, abundant acids were observed in various reported fish sauce products, such as fish sauce made from blue round scad, channel catfish bone, and Nile tilapia fish head4,12,20. Despite the trend of increasing acid content observed after fermentation, they had little effect on the overall flavor of fish sauce owing to their high thresholds55.

The rest of the compounds in fish sauce include furans, pyrazines, and others (Fig. 4K). Compared to the control group, 2-pentyl furan was lower in the FH and FS groups. These reductions would be desirable since 2-pentyl furan contributes to a pungent “vegetable-like” odor rather than the intended “meat-like”56. The concentration of 2-butylfuran increased after enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, contributing to the formation of a mild, sweet, and spicy flavor in the fish sauce57. Moreover, dipropyl disulfide has cooked cabbage and onion flavors53, and the increase in dipropyl disulfide concentration in the FS group could contribute to fish sauce’s pleasant flavor.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of VOCs

PCA was used to analyze the similarity of VOCs in the control, FH, and FS groups identified by HS-GC-IMS. As shown in Fig. 4L, the cumulative contribution rate of the first two principal components of the groups was 97% (PC1 for 61%, PC2 for 36%), indicating that HS-GC-IMS could efficiently identify the differences in VOCs among the three groups. From the degree of aggregation and dispersion of the groups, it could be seen that the VOCs among the three groups had great differences. Overall, the combination of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation was a desirable method for rapidly preparing fish sauce with good flavor, as evidenced by increased esters with pleasant aromas and reduced aldehydes with fishy odors in the obtained fish sauce.

Identification of umami peptides from fish sauce

Umami peptides significantly contribute to the taste profile of fermented products58. Although several umami peptides have been previously identified from various fermented fish products, there is still a gap in research on umami peptides obtained from fish sauce15,16. This study identified 357 peptides from the fish sauce (Fig. S1A), of which 342 peptides with scores above 40 were selected as screening results to ensure the reliability of the data. Figure 5A showed that peptides with molecular weights (MWs) between 500–1000 Da were the most abundant, followed by peptides with MWs above 1500 Da, while peptides with MWs of 500–100 Da or <500 Da were present in smaller quantities. The umami intensities of peptides are related to their MWs, and umami peptides are typically small MW peptides less than 1500 Da59,60. Therefore, the abundant peptides with a MW of less than 1500 Da were the most likely important umami-presenting substances for fish sauce in the present study.

A The MW distribution of the detected peptides with a score above 40. B Amino acid composition of the detected peptides with a score above 40. C Virtual screening results based on toxicity, MW, allergenicity, water solubility, stability, and bitterness of peptides. D The stereo diagram of AEREIVRDIKEK into the T1R1/T1R3 active-site cavity. E The 3D binding mode of AEREIVRDIKEK to T1R1/T1R3. F The 2D molecular docking of the binding of AEREIVRDIKEK to T1R1/T1R3. G The stereo diagram of NWDDMEK into the T1R1/T1R3 active-site cavity. H The 3D binding mode of NWDDMEK to T1R1/T1R3. I The 2D molecular docking of the binding of NWDDMEK to T1R1/T1R3.

From the amino acid distribution results (Fig. 5B), the hydrophobic amino acid residues constituted a high proportion (52.8%) of the total amino acids in the peptides obtained from fish sauce. Most of the reported umami peptides contained hydrophobic amino acids, which served to enhance the umami expression of umami peptides61,62. Further analysis of the amino acid composition of peptides revealed that the percentages of Val, Leu, Pro, His, and Asp were in the top five of 19 amino acids, which were 13.8%, 9.3%, 9.1%, 9%, and 7.8%, respectively. Asp is a key amino acid component for umami peptides, and Pro, as a sweet amino acid, can cooperate with umami amino acids to form flavor63,64. In addition, as another recognized umami amino acid, Glu accounted for 2.7% of the total amino acids in the obtained peptides, contributing to the umami of fish sauce to some extent.

Virtual screening of the potential umami peptides

Virtual screening techniques can be used to screen for umami peptides rapidly63. 136 peptides with a MW above 1500 Da were eliminated first in this study, and the remaining 206 peptides (60.2%) entered the next stage of screening (Fig. 5C). Toxicity is a key indicator of peptides65, and all of these 206 peptides were predicted to be non-toxic. From a food safety perspective, the subsequent analyses ignored 84 peptides predicted to be allergenic. Stability and water solubility have been considered limiting factors affecting the perceived taste strength of umami peptides16. Only 49 peptides (14.3%) were predicted to have good water solubility and stability, and they were further analyzed for their umami characteristics. After the layer-by-layer screening described above, 19 (5.6%) peptides were finally shortlisted as potential umami peptide candidates for further analysis.

The sensory activities of 19 potential umami peptides were further evaluated using the BIOPEP-UWM tool, and the results are shown in Table 3. Active fragments affect the flavor of small peptides, and the higher the frequency of occurrence, the stronger the sensory activity of peptides66. The peptide with the highest frequency of umami fragments was NWDDMEK (0.714), followed by AEREIVRDIKEK (0.5). Their mass spectra and chemical structure are shown in Fig. S1B–E. To date, the same amino acid sequences of these two peptides have not been reported in the BIOPEP-UWM database, indicating they are novel members of the umami peptide family. Thus, these two potentially novel umami peptides were selected to further predict the umami characteristics through molecular docking.

Interaction mechanisms of umami peptides and T1R1/T1R3

Umami perception in the human body begins with the binding of umami substances to umami taste receptors, among which T1R1/T1R3 located in the anterior part of the tongue serves as the primary receptors for umami67. The extracellular Venus flytrap domain (VFTD) of the T1R1 subunit was primarily responsible for the gustatory perception of umami peptides, with the T1R3 subunit in charge of additional ancillary features68,69. Therefore, the T1R1 receptor lumen was selected as the active region for further molecular docking in this study (Fig. S2A, B). Figure 5D–I showed the results for molecular docking of umami peptides AEREIVRDIKEK and NWDDMEK with T1R1/T1R3. Both two peptides were embedded in the T1R1 subunit and exhibited docking energies of −13.7 and −10.9 kcal/mol, respectively. The umami peptides AEEHVEAVN from chicken breast soup and GESMTDGF from porcine type I collagen have been reported to bind with the VFTD of the T1R1 with the energy of −9.69 and −8.6 kcal/mol, respectively70,71. Compared with these two known umami peptides, the lower docking energies of AEREIVRDIKEK and NWDDMEK indicated their substantial binding forces with T1R1/T1R3 receptors and the possible existence of potent umami tastes.

Besides comparing affinity energy, it is also required to investigate the binding modes of peptides with T1R1/T1R3. As shown in Fig. 5D–F, the umami peptide AEREIVRDIKEK formed seven hydrogen bonds with six amino acid residues (Gly49, Phe68, Glu70, Asp108, His308, and Met375) of T1R1/T1R3, with key residues Glu70 contributing two hydrogen bonds. The umami peptide NWDDMEK interacted with seven amino acid residues (Glu70, His71, Asp147, Ala170, Arg277, Arg281, and Ser306) of T1R1/T1R3 to form nine hydrogen bonds, with Arg277 being particularly involved in three hydrogen bonds (Fig. 5G–I). It was evident that hydrogen bonding played a key role in facilitating the robust interaction between the two umami peptides and T1R1/T1R3, consistent with previous research65,72. Furthermore, both AEREIVRDIKEK and NWDDMEK could bind to the Glu70 binding site, which was the most critical binding site65. These results were also in line with the conclusion that Glu residue was the key residue in the active site, as earlier demonstrated by Dong et al.73. In addition, it was observed that NWDDMEK formed three hydrogen bonds with Arg277 residue. Similarly, Zhang et al.71 revealed the important role of Arg277 in the interaction of six umami peptides with T1R1 subunits. In particular, some of the binding residues identified in this study, including Gly49, His71, Asp108, Asp147, Ala170, and Ser306, have been definitively reported to be active residues in the T1R1-peptide complex, where the umami peptides were derived from porcine bone soup64, chicken breast soup71, and tuna skeletal myosin61. In summary, AEREIVRDIKEK and NWDDMEK may be the potential umami-presenting substances for fish sauce and offer more insight into the umami research of fish sauce. However, further investigation and validation of the umami characteristics of the two peptides after synthesis are still required.

In this study, the efficient preparation technology (a combination of compound enzyme hydrolysis and L. fermentum fermentation) and flavor profiles of no-salt-added fish sauce made from yellowfin tuna dark meat were reported for the first time. The results showed that the optimum enzymatic hydrolysis and L. fermentum fermentation conditions could be adopted to produce a high-quality fish sauce with a salt content of 0.128% and an AA-N content of 0.603 ± 0.036 g/100 mL. The obtained fish sauce has a good aroma, as evidenced by an increase in esters with pleasant aromas and the reduction of aldehydes with fishy odors. Furthermore, the prominent umami in fish sauce may be due to the release of umami peptides during the preparation process, with AEREIVRDIKEK and NWDDMEK standing out for their potential umami attributes. Overall, this study provided a new way for efficient fish sauce production and better insights into the potential applications of fish by-products.

Methods

Materials and reagents

Yellowfin tunas were commercially captured and dissected from the South China Sea (17°24′N, 110°36′E) by Hainan Orca Sea Fishing Service Co., Ltd. Fresh yellowfin tuna dark meat was collected and stored at −80 °C. Trypsin and alcalase were provided by Yangshao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Henan, China) and Lonct Enzymes Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China), respectively. Lactobacillus fermentum (L. fermentum, accession no. BNCC194173) was obtained from Henan Microbiological Culture Collection Center (Henan, China). MRS broth and MRS agar medium were purchased from Guangdong Huankai Microbial Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Other chemicals used were all of analytical grade.

Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis conditions

In our previous work (unpublished data), the compound enzyme (trypsin/alcalase compound ratio (w/w) = 2:1) showed an excellent enzymatic hydrolysis effect (highest DH) on yellowfin tuna dark meat, and thus it was used in the present study for enzymatic hydrolysis. Yellowfin tuna dark meat was ground in a meat grinder and sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min. Then, the treated dark meat was mixed with distilled water at a solid–liquid ratio of 1:4. After a certain dosage of the enzyme (w/w) was added, the mixture was adjusted to the desired pH, and then subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis at controlled temperatures for 4 h as per our experimental design. Finally, the obtained yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate was heated in a water bath at 90 °C for 10 min to terminate the hydrolysis reaction.

According to the method reported by Yang et al.74 and the optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions suggested by the manufacturer, the enzyme dosage (2–3.6%), pH levels (6.5~8.5), and temperature (45–65 °C) were systematically investigated to optimize the enzymatic hydrolysis conditions of yellowfin tuna dark meat. The DH of the yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate was used as the evaluation index. One factor was changed in each experiment, while other factors were kept unchanged.

According to the Box-Behnken principle of the response surface, the enzyme dosage (X1), pH (X2), and temperature (X3) were selected as the investigation factors based on the single-factor experiment results, and DH was used as the response value for optimization experiments. Seventeen runs with five center points were carried out randomly (Table 1).

Optimization of fermentation conditions

L. fermentum was anaerobically incubated in the MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h. After centrifugation for 10 min at 6000 r/min and 4 °C, L. fermentum was resuspended in 0.9% sterile saline water (w/v) at a CFU of 107/mL and used as a starter culture. A certain dosage of glucose was added to yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate and sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min. The sterilized yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate was then mixed with L. fermentum at a certain dosage and fermented at 37 °C for a certain time. At the end of the fermentation, the fish sauce was obtained by filtering the fermentation supernatant with gauze and sterilizing it at 115 °C for 15 min.

Following previous reports on fish sauce inoculation and fermentation conditions5,75, glucose dosage (0.1–1.9%), inoculation size (2–8%), and fermentation time (1–7 days) were systematically investigated to optimize the fermentation conditions of fish sauce. The individual impact of each variable on the AA-N content of fish sauce was assessed by altering one factor at a time while keeping the other two factors constant.

Based on the results of single-factor experiments, the glucose dosage (X1), inoculation size (X2), and time (X3) were selected as the investigation factors, and the AA-N of fish sauce was the response value for optimization experiments. Seventeen experiments based on the Box-Behnken design were performed to optimize the fermentation conditions of fish sauce (Table 2).

Determination of chemical properties

The total acid and AA-N contents of samples were determined with reference to GB5009.235-2016 (China). The TS-N content was determined by an automatic Kjeldahl apparatus (KJELTEC 8400, Foss TecatorAB, Hogans, Sweden) according to GB5009.5-2016 (China). DH was calculated using the Eq. (1):

The growth of L. fermentum in the fish sauce was evaluated using the plate count method. Decimal dilutions of the fish sauce were prepared in sterile peptone water (0.1%, w/w), and 1 mL of an aliquot of the appropriate dilution was inoculated on the MRS agar medium. Then, all the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The results were expressed as colony-forming units per milliliter of the fish sauce (lg CFU/mL).

The pH of fish sauce was measured by a pH meter (Mettler Toledo 8603, Switzerland).

The TVB-N content was determined using the method previously described by Du et al.1 with some modifications. Fish sauce (10 mL) was mixed with 75 mL of distilled water in a distillation tube, and then 1.0 g of MgO was added. The TVB-N content of fish sauce was determined by titration with 0.1 mol/L HCl solution using an automatic Kjeldahl apparatus (KJELTEC 8400, Foss TecatorAB, Hogans, Sweden).

Determination of salt content

The salt content of fish sauce was determined by the Mohr method according to the GB 5009.44-2016 (China).

Sensory analysis

The sensory characteristics of fish sauce prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation conditions (FS) were conducted by quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA)9, with the yellowfin tuna dark meat–water mixture without enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation treatment (control), and the yellowfin tuna dark meat hydrolysate prepared under optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions (FH) as comparison groups. Our institution (Hainan University, Haikou, China) did not require ethical permission for the sensory evaluation on food to evaluate food sensory, and this experiment was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from ten panelists (five men and five women, aged 20–30), and training in the sensory descriptions of fish sauce was conducted before the sensory evaluation. Different sensory attributes of fish sauce (brown color, aroma, bitter, sour, rancid, fishy, umami, caramel, and ammonia) were then evaluated using this trained sensory panel. Sensory evaluation was conducted in a sensory lab with individual booths and illuminated by natural light. The score scale ranged from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no perceptible intensity and 10 representing extreme intensity of an attribute.

Analysis of VOCs by HS-GC-IMS

Changes in VOCs of fish sauce at different processing stages were investigated using a flavor Spec1H1-00053 HS-GC-IMS (G.A.S, Dortmund, Germany) according to Wang et al.76. The control, FH, and FS samples (3.00 g) were weighed and placed in a 20 mL headspace vial, respectively, and incubated at 60 °C for 15 min. The headspace gas (500 μL) was then driven into the column (WAX, 15 m, 0.53 mm ID) by the autosampler (60 °C) with N2 according to the set program: the flow rate was 2 mL/min initially, 10 mL/min at 10 min, 100 mL/min at 20 min, and finally 150 mL/min at 30 min. After GC separation, the analytes were ionized in the IMS ionization chamber (positive ion mode). Finally, the VOCs were identified by comparing the retention index (RI) and drift time (Dt).

Identification of peptides by LC–MS/MS

Peptide analysis of fish sauce was performed using a Q-Exactive Plus coupled to an EASY-nanoLC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to Gu et al.67. The fish sauce sample was ultrafiltered (10 kDa), desalted, and separated using an RP-C18 column (0.15 mm × 150 mm, 5 µm, Column Technology Inc) at a flow rate of 0.25 µL/min. Water (containing 0.1% formic acid) was used as mobile phase A, and water (consisting of 0.1% formic acid and 84% acetonitrile) was used as mobile phase B. The chromatographic gradient was as follows: 0–50 min, 96–50% A; 50–54 min, 50–0% A; 54–60 min, 0% A. The data-dependent acquisition was performed on the Orbitrap analyzer in positive mode with profile analysis, and the MS spectra were searched against the UniProt FASTA databases by MaxQuant software.

Virtual screening of potential umami peptides

First, the peptides with a score above 40 and MW <1500 Da were selected for subsequent virtual screening. Peptide candidates were further shortlisted using the ToxinPred tool (https://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/toxinpred/index.html) (non-toxicity), AllerTOP v. 2.0 tool (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/) (non-allergen), Innovagen tool (https://www.innovagen.com/proteomics-tools) (good water solubility), and Expasy-protparam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) (stability). UMPred-FRL (https://pmlabstack.pythonanywhere.com/UMPred-FRL) was used in parallel with the preliminary screening of umami peptides. Finally, BIOPEP-UWM (https://biochemia.uwm.edu.pl/biopep-uwm/) was used to predict and calculate the novelty and occurrence frequency of sweet, bitter, umami, salty, and sour fragments in potential umami peptides.

Homology modeling of umami receptor T1R1/T1R3 and molecular docking

The 3D structure of T1R1/T1R3 was established through homology modeling. The sequence of T1R1/T1R3 was retrieved from the UniProtKB database (https://www.UniProt.org/). Homologous modeling (Fig. S2A) was performed by the SWISS-MODEL server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) with the fish taste receptor T1R2a-T1R3 (PDB ID: 5X2M) chosen as the template. The model was verified by the Ramachandran plot chart (Fig. S2B) exported by SAVES v6.0 (https://services.mbi.ucla.edu/SAVES) and subsequently used for molecular docking.

The potential umami peptides were docked to T1R1/T1R3 using Autodock Tools 1.5.6. Since the T1R1 structural domain of the flytrap is the primary recognition area for umami peptides61,77, the size of the docking box was set to 66 Å × 72 Å × 86 Å with 0.375 Å spacing, and the coordinates of the active center were defined as x = 47.00 Å, y = 23.15 Å, and z = 44.35 Å. Finally, the molecular docking results were visually analyzed using PyMol.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out in triplicate, representing the data as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Design-Expert V8.0.6 (State-East, Minneapolis, USA) was used to perform quadratic multivariate fitting on the Box-Behnken design results. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the significance of the model (P < 0.05), and the corresponding surface results were then calculated using multiple quadratic regression equations. Statistical analysis for other data was performed using ANOVA one-way analysis in SPSS software 26.0 (IBM, New York, USA) with the Tukey post-test (P < 0.05) for statistical significance.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Du, Y. et al. Changes in the chemical properties and metabolite profiling of fish sauce prepared from underutilized large yellow croaker roes during fermentation at different temperatures. Food Res. Int. 179, 114030 (2024).

Gao, P., Xia, W., Li, X. & Liu, S. Use of wine and dairy yeasts as single starter cultures for flavor compound modification in fish sauce fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2300 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Novel insight into flavor and quality formation in naturally fermented low-salt fish sauce based on microbial metabolism. Food Res. Int. 166, 112586 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Microbial community changes induced by a newly isolated salt-tolerant Tetragenococcus muriaticus improve the volatile flavor formation in low-salt fish sauce. Food Res. Int. 156, 111153 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Effect of lactic acid bacteria on mackerel (Pneumatophorus japonicus) seasoning quality and flavor during fermentation. Food Biosci. 41, 100971 (2021).

WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for Adults and Children (WHO, 2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Quality characteristics of sardine (Sardina pilchardus) fish sauce produced using five kinds of material. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 34, 100801 (2023).

Han, J. et al. Comparative analysis of key precursors and metabolites involved in flavor formation of different rapid-fermented Chinese fish sauces based on untargeted metabolomics analysis. Food Chem. 433, 136998 (2024).

Sun, J. et al. Effect of fermentation by Aspergillus oryzae on the biochemical and sensory properties of anchovy (Engraulis japonicus) fish sauce. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 133–141 (2016).

Cai, H. et al. Lactic acid bacteria in fermented fish: enhancing flavor and ensuring safety. J. Agric. Food Res. 16, 101206 (2024).

Zhu, W. et al. Changes in taste substances during fermentation of fish sauce and the correlation with protease activity. Food Res. Int. 144, 110349 (2021).

Gao, P., Li, L., Xia, W., Xu, Y. & Liu, S. Valorization of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fish head for a novel fish sauce by fermentation with selected lactic acid bacteria. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 129, 109539 (2020).

Chang, R. et al. Ion-exchange purification, nano-HPLC-MS/MS identification and molecular dynamics simulation of novel umami peptides from fermented grain wine (Huangjiu). J. Food Compos. Anal. 125, 105822 (2024).

Yang, D. et al. Taste mechanism of umami peptides from Chinese traditional fermented fish (Chouguiyu) based on molecular docking using umami receptor T1R1/T1R3. Food Chem. 389, 133019 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Identification and comparison of umami-peptides in commercially available dry-cured Spanish mackerels (Scomberomorus niphonius). Food Chem. 380, 132175 (2022).

Zou, H. et al. Combination of virtual screening, machine learning, molecular dynamics simulations and sensory evaluation to discover novel umami peptides from fermented Atlantic cod. Food Biosci. 59, 104250 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Effects of quality enhancement of frozen tuna fillets using ultrasound-assisted salting: physicochemical properties, histology, and proteomics. Foods 13, 525 (2024).

Yu, H. et al. Novel Se-enriched α-glucosidase inhibitory peptide derived from tuna dark meat: preparation, identification and effects on IR-HepG2 cells. Food Biosci. 60, 104357 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Analysis of nutrient and fatty acid composition of different by-products of yellowfin tuna in South China Sea. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 45, 1–9 (2024).

Gao, P. et al. Co-inoculation of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus 1 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae 31 for a salt-free fish sauce production from channel catfish (Ietalurus punetaus) bone. Food Biosci. 50, 102137 (2022).

Wu, Q., Qin, D., Cao, H. & Bai, Y. Enzymatic hydrolysis of polysaccharide from Auricularia auricula and characterization of the degradation product. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 162, 127–135 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Preparation and identification of antioxidant peptides from Quasipaa spinosa skin through two-step enzymatic hydrolysis and molecular simulation. Food Chem. 445, 138801 (2024).

Hao, L. et al. Enzymatic hydrolysis optimization of yak whey protein concentrates and bioactivity evaluation of the ultrafiltered peptide fractions. Molecules 29, 1403 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Optimization of fermentation process of pomegranate peel and Schisandra chinensis and the biological activities of fermentation broth: antioxidant activity and protective effect against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in HaCaT cells. Molecules 26, 3432 (2021).

Heng, X. et al. Study on synergistic fermentation of bean dregs and soybean meal by multiple strains and proteases. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 154, 112626 (2022).

Zhu, L. et al. Metabolomics mechanism of traditional soy sauce associated with fermentation time. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 11, 297–304 (2022).

Pius Bassey, A. et al. Untargeted metabolomics unravels the effects of ginkgolide B-producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and co-induced fermentation of ginkgo kernel juice and their underlying vascular endothelial cell protection activity. Food Res. Int. 197, 115168 (2024).

Sripokar, P., Klomklao, S., Hansen, E. B., Maneerat, S. & Panyo, J. The impact of autolysis times prior to salting and salt concentrations on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of Ka-pi-plaa, Thai fermented fish paste produced from beardless barb. J. Agric. Food Res. 22, 102037 (2025).

Gao, P. et al. Application of Wickerhamomyces anomalus and Pichia fermentans to improve the aroma of fermented sour fish. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 192, 115725 (2024).

Park, S. et al. Changes in the physicochemical properties and metabolites of Myeolchi-jeot (salted-fermented anchovy) based on fermentation time. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 177, 114456 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Effect of fermentation conditions on the formation of ammonium salt in soy sauce. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 153, 112492 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. The flavour of wheat gluten hydrolysate after Corynebacterium Glutamicum fermentation: effect of degrees of hydrolysis and fermentation time. Food Chem. 458, 140238 (2024).

Gao, R. et al. Correlation between dominant bacterial community and non-volatile organic compounds during the fermentation of shrimp sauces. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 12, 233–241 (2023).

Zheng, B. et al. Quality improvement on half-fin anchovy (Setipinna taty) fish sauce by Psychrobacter sp SP-1 fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 97, 4484–4493 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Changes in protein and volatile flavor compounds of low-salt wet-marinated fermented Golden Pomfret during processing. Food Chem. 456, 140029 (2024).

Zarei, M. et al. Chemical and microbial properties of mahyaveh, a traditional Iranian fish sauce. Food Control 23, 511–514 (2012).

Lestari, S. D. et al. Bacterial community structure, predicted metabolic activities, and formation of volatile compounds attributed to Malaysian fish sauce flavour. Food Chem. 426, 136568 (2023).

Han, J. et al. An isolated salt-tolerant Tetragenococcus halophilus 2MH-3 improved the volatile flavor of low-salt fermented fish sauce by regulating the microbial community. Food Res. Int. 196, 115052 (2024).

Li, C., Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Wu, Y. & Chen, S. Improvement of the quality and safety of low-salt fish sauce by reconstruction of microbial community through cooperative fermentation of starters. Food Res. Int. 205, 115972 (2025).

Li, X. -a et al. Compensative role of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria in physical properties and taste profiles of dry sausage with partial substitution of NaCl by KCl. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 199, 116115 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Effect of different processing steps in the production of beer fish on volatile flavor profile and their precursors determined by HS-GC-IMS, HPLC, E-nose, and E-tongue. Food Chem. X 23, 101623 (2024).

Yang, N. et al. Analysis of volatile flavor substances in the enzymatic hydrolysate of Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom and its Maillard reaction products based on E-Nose and GC-IMS. Foods 11, 4056 (2022).

Cao, C. et al. Effects of fermentation with Tetragenococcus halophilus and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii on the volatile profiles of soybean protein hydrolysates. Foods 12, 4513 (2023).

Liang, Z. et al. Physicochemical properties and volatile profile of mung bean flour fermented by Lacticaseibacillus casei and Lactococcus lactis. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 163, 113565 (2022).

Dai, W. et al. Effect of chitosan-epigallocatechin gallate coating on volatile flavor compounds retention in bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis) fillets during chilled storage. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 169, 114027 (2022).

Chen, J., Tang, H., Wang, M., Wei, H. & Ou, C. Explorative study for the rapid detection of adulterated surimi using gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry. Food Chem. 439, 138083 (2024).

Lv, Y. et al. Flavor characteristics of large yellow croaker soup served with different dried edible fungi. Food Chem.: X 21, 101059 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Characterization of the effect of different cooking methods on volatile compounds in fish cakes using a combination of GC-MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem.: X 22, 101291 (2024).

Toda, Y. et al. Positive/negative allosteric modulation switching in an umami taste receptor (T1R1/T1R3) by a natural flavor compound methional. Sci. Rep. 8, 11796 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Influence of thermal processing on flavor and sensory profile of sturgeon meat. Food Chem. 374, 131689 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. GC-MS, GC-IMS, and E-Nose analysis of volatile aroma compounds in wet-marinated fermented golden pomfret prepared using different cooking methods. Foods 13, 390 (2024).

Luo, X. et al. Differences in flavor characteristics of frozen surimi products reheated by microwave, water boiling, steaming, and frying. Food Chem. 372, 131260 (2022).

Nie, S. et al. Discrimination and characterization of volatile organic compound fingerprints during sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicas) fermentation by combining GC-IMS and GC-MS. Food Biosci. 50, 102048 (2022).

Guo, Q. et al. Identification of odor-causing compounds in six species of odor-producing microalgae separated from drinking water source with distinct fishy odor: insight into microalgae growth and odor characteristics. Chemosphere 350, 141043 (2024).

Li, C., Chen, S., Huang, H., Li, J. & Zhao, Y. Improvement mechanism of volatile flavor in fermented tilapia surimi by cooperative fermentation of Pediococcus acidilactici and Latilactobacillus sakei: quantization of microbial contribution through influence of genus. Food Chem. 449, 139239 (2024).

Li, X. & Liu, S. Impacts of thermal treatment, xylose and cysteine addition on aroma compounds profile in lactic acid bacterium fermented pork hydrolysates. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 152, 112368 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Study on the factors affecting the sauce-flavor compounds of soybean paste in fermentation. Food Biosci. 59, 103872 (2024).

An, F. et al. Identification, taste characterization, and molecular docking study of a novel microbiota-derived umami peptide. Food Chem. 404, 134583 (2023).

Xu, X., Zheng, Y., Song, H., Gong, L. & Pan, W. The effects of enzymatic hydrolysis degree of bovine bone marrow extract on flavor generation via the Maillard reaction. J. Food Meas. Charact. 13, 521–535 (2019).

Rhyu, M. & Kim, E. Umami taste characteristics of water extract of Doenjang, a Korean soybean paste: low-molecular acidic peptides may be a possible clue to the taste. Food Chem. 127, 1210–1215 (2011).

Zhao, S. et al. Combining molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation to discover four novel umami peptides from tuna skeletal myosin with sensory evaluation validation. Food Chem. 433, 137331 (2024).

Shen, Q., Sun, L., He, Z., Xie, J. & Zhuang, Y. Isolation, taste characterization and molecular docking study of novel umami peptides from Lactarius volemus (Fr.). Food Chem. 401, 134137 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Umami peptides screened based on peptidomics and virtual screening from Ruditapes philippinarum and Mactra veneriformis clams. Food Chem. 394, 133504 (2022).

Liang, L. et al. Characteristics of umami peptides identified from porcine bone soup and molecular docking to the taste receptor T1R1/T1R3. Food Chem. 387, 132870 (2022).

Zhao, W., Zhang, Q., Su, L. & Yu, Z. Taste characteristics and umami mechanism of novel umami peptides from hen egg proteins. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 181, 114778 (2023).

Bu, Y. et al. Characterization and structure–activity relationship of novel umami peptides isolated from Thai fish sauce. Food Funct. 12, 5027–5037 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. Screening and characterization of novel umami peptides in Cheddar cheese using peptidomics and bioinformatics approaches. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 194, 115780 (2024).

Toda, Y. et al. Two distinct determinants of ligand specificity in T1R1/T1R3 (the umami taste receptor). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36863–36877 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Identification of novel umami peptides from yeast extract and the mechanism against T1R1/T1R3. Food Chem. 429, 136807 (2023).

Gu, Y. et al. Virtual screening and characteristics of novel umami peptides from porcine type I collagen. Food Chem. 434, 137386 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Identification of novel umami peptides in chicken breast soup through a sensory-guided approach and molecular docking to the T1R1/T1R3 taste receptor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 7803–7811 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Identification of umami peptides based on virtual screening and molecular docking from Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Food Funct. 14, 1510–1519 (2023).

Dong, Y. et al. Unraveling umami complexity: from exploring umami peptides in fermented soybean curd to molecular elucidation of taste mechanisms. Food Biosci. 59, 103951 (2024).

Yang, M. et al. Preparation, isolation and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from extruded-expanded tuna bone meal. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 228, 118038 (2025).

Gao, P. et al. Evaluation of exogenous lactic acid bacteria, yeasts and staphylococci for flavor improvement of channel catfish frame hydrolysate. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 213, 117032 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Changes in physicochemical properties, moisture distribution and volatile flavor compounds of yellow catfish: the roles of dominant spoilage bacteria. Food Biosci. 56, 103331 (2023).

Zhang, J., Sun-Waterhouse, D., Su, G. & Zhao, M. New insight into umami receptor, umami/umami-enhancing peptides and their derivatives: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 88, 429–438 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 32360578).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hui Yu: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, and writing—original draft. Caiye Qu: Methodology, data curation, and validation. Pai Peng: Data curation and validation. Meiting Xian: Formal analysis and validation. Zhiqiang Guo: Validation, supervision, and funding acquisition. Eunice Mutethya: supervision, and writing—review and editing. Juan Xiao: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Qu, C., Peng, P. et al. Preparation of no-salt-added fish sauce with aroma and umami coexistence from yellowfin tuna dark meat. npj Sci Food 9, 222 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00582-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00582-w