Abstract

The rapid increase in global meat demand has placed significant pressure on traditional meat production. This has led to the emergence of the cultured meat industry as a promising alternative offering sustainable and ethical solutions. This study explored the efficacy of chick embryo extract (CEE) as a potential economic supplement. Specifically, we aimed to identify the optimal culture conditions for chicken muscle satellite cells (CMSCs) using CEE and evaluate their effects on cell proliferation and differentiation. The CEE+horse serum (HS) condition was found to be the most effective for CMSC proliferation, with a significant increase in the expression of myogenic transcription factors. CMSCs cultured in 30% CEE + 3% HS-containing differentiation medium (CEE + 3%HS-DM) showed higher expression of myogenic differentiation markers and formed thicker myotubes compared to the CMSCs cultured in the 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-containing differentiation medium (5% FBS-DM). Notably, CMSCs differentiated in CEE + 3%HS-DM displayed consistently aligned myotubes in the predominant direction. In contrast, myotubes in the 5% FBS-DM showed less directional preference. To investigate 3D myofiber formation on plant-based scaffolds, CMSCs were cultured on a decellularized green onion scaffold. CMSCs successfully attached and differentiated into myofibers, with significantly enhanced attachment and differentiation observed in CMSCs cultured in CEE + 3%HS-DM compared to those in 5% FBS-DM. These results demonstrate that CEE + 3%HS-DM is suitable for CMSC differentiation and 3D myotube formation, providing a promising culture system for sustainable cultured meat production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid population growth, accompanied by economic development and new dietary trends in developing countries, is driving significant increases in animal protein demand1,2. As the largest protein producer, conventional meat production faces various environmental concerns and the risk of new infectious diseases. The dependence on animal exploitation and slaughter also raises ethical concerns regarding animal welfare3,4,5. Owing to these issues, there is a growing interest in the development and industrialization of cultured meat as a sustainable solution. The term ‘cultured meat’ refers to meat produced through cell culture in a controlled environment using tissue engineering or 3D printing technologies6,7,8. Cultured meat production is still in its early stages, and high costs and inefficient technologies remain, thereby hindering its application and commercialization. To meet the commercial demand, industrial-scale production of cultured meat depends heavily on cell propagation. Therefore, optimizing the proliferation rate and differentiation capabilities of cells during the culturing process is essential.

Culture media and supplements are essential for cell culture. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) is an important supplement required for cell survival and growth. FBS contains essential components for cell attachment, growth, and maintenance, including serum albumin, fetuin, hormones, and growth factors9. Because FBS is obtained from the fetuses of slaughtered pregnant female bovines, its limited supply leads to high costs, making it a major barrier to the large-scale commercialization of cultured meat9. Accordingly, in the last six decades researchers have been trying to alternate FBS with different sources include hormone10, bovine colostrum or platelet lysate11, chick embryo extract (CEE)12, sericin protein13,14 and plant origin15. Among these alternatives, CEE has been shown to effectively promote the proliferation and differentiation of myogenic cells16,17,18,19,20,21. During the development of an embryo into a chick inside an egg, various substances necessary for cell and muscle growth are expressed22,23. Therefore, it is likely that CEE contains several growth factors that promote cellular growth. Moreover, because eggs are relatively easy to obtain and inexpensive compared to conventional culture supplements, CEE has the potential to serve as a substitute for FBS. Chicken muscle satellite cells (CMSCs) were selected as the target cell type due to their critical role in skeletal muscle regeneration and growth. CMSCs are adult stem cells residing between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of muscle fibers, and they possess high proliferative potential and the ability to differentiate into myotubes24,25,26. These properties make CMSCs an ideal model for evaluating the potential of culture media to support muscle cell proliferation and differentiation. Overall, this study aimed to establish optimal culture conditions using CEE, and to evaluate whether CEE can serve as a viable substitute for FBS.

Results

Optimization of CEE concentration for CMSC culture

Given that CEE is a potential substitute for FBS21, we aimed to determine the optimal CEE conditions and assess their effect on the culture of CMSCs. To determine the optimal CEE concentration, CMSCs were cultured in media supplemented with seven different concentrations of CEE (3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40%), with a 15% FBS-containing medium serving as the control group for comparison. The cell proliferation rate gradually increased up to 30% CEE concentration but subsequently decreased at 40% CEE (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). This trend was observed at both 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and 72 h, where the proliferation rate steadily increased up to 30% CEE, but then significantly declined at 40% CEE (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1b). Among the seven concentrations of CEE, the proliferation rate was highest at 20% and 30% CEE (p < 0.01); however, it reached only about half of that observed in the control group (Fig. 1b). Based on the proliferation rate data, we initially selected 20% and 30% CEE for subsequent experiments. Further experiments were conducted using these two concentrations, and one concentration was selected based on the results.

a Morphological images of CMSCs in each group. Scale bars, 200 μm. b Proliferation rate of CMSCs according to the variations in the concentration of CEE at 72 h (n = 5). Values are presented as the mean ± SE. a-f Different letters represent statistically significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.01).

Establishment of optimal culture conditions for CMSCs

Even at the optimal CEE concentration, the proliferation rate of the CMSCs cultured with CEE did not reach that observed in the presence of FBS. To address this limitation, we developed modified culture conditions by supplementing CEE with a small amount of serum and evaluated its effects on the proliferation of CMSCs. In our previous study, we demonstrated that HS combined with CEE exerted a synergistic effect on CMSCs21. Therefore, we used HS and FBS as serum supplements. The proliferation rates of CMSCs were compared at different time points (48 and 72 h) under varying CEE concentrations, as well as different concentrations of FBS and HS (Supplementary Fig. 2). As expected, the proliferation rate of CMSCs increased with the addition of serum to the CEE-containing medium compared to those cultured with CEE alone (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, under serum-supplemented CEE culture conditions, the cell morphology appeared more elongated compared to that of the CEE only groups (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Notably, among the treatment conditions, the highest proliferation rates of CMSCs were observed in cultures supplemented with 30% CEE and either 1% FBS (referred to as the CEE + FBS group) or 3% HS (referred to as the CEE + HS group). These two conditions resulted in proliferation rates comparable to those of the control group (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Morphological images of CMSCs in each group. Scale bars, 200 μm. b Proliferation rate of CMSCs according to serum addition to CEE at 72 h (n = 5). c Immunofluorescence images of Pax7 in CMSCs. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and proliferation marker Pax7 (red). Scale bars, 50 μm. d The ratio of Pax7+/DAPI+ cells shown in the Immunofluorescence images (n = 3). e Protein levels of Pax7 and MyoD in CMSCs. f Quantification of Pax7 and MyoD protein levels relative to GAPDH (n = 3). g Gene expression levels of PAX7, MYOD1, and MYF5 in CMSCs (n = 3). For (b, d, f, g), the significant difference between treatments was identified by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. The data are presented as mean ± SE. a-d Different letters represent statistically significant differences among treatment groups (ns: not significant; p < 0.01).

Next, we compared the expression patterns of myogenic transcription factors between control and serum-supplemented CEE groups. In the CEE + FBS and CEE + HS groups, most cells were positive for Pax7, a marker of muscle satellite cells, with expression levels higher than those in the control group (Fig. 2c, d). In contrast, in the CEE only group, approximately 30% of the cells were not stained for Pax7 (Fig. 2d). Accordingly, Pax7 protein expression levels were higher in serum-supplemented CEE conditions than in the control group (Fig. 2e). However, there were no significant differences (p < 0.01) in MyoD protein expression levels between the conditions (Fig. 2e, f). qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the early myogenic marker genes, MYOD1 and MYF5 exhibited the highest expression levels in the CEE + HS group (Fig. 2g). Collectively, while CEE alone was significantly less effective than FBS in supporting CMSC proliferation, its combination with a small amount of HS exhibited a synergistic effect, leading to comparable proliferation rates to 15% FBS-containing condition. These results indicate that CEE, particularly in combination with HS, is a potential alternative to FBS for CMSC culture.

CEE + HS condition promotes myogenic differentiation more effectively than CEE + FBS

Next, we investigated the effects of CEE on CMSC differentiation. Interestingly, despite being applied as a proliferation medium, CEE + HS cultures exhibited distinct signs of myogenic differentiation. After 72 h of differentiation, MYHC, a myofiber marker, was detected in the CEE + FBS and CEE + HS groups, but not in the CEE only group (Fig. 3a). Quantification of the MYHC-stained surface area revealed an average expression of approximately 1% in the CEE + FBS condition and about 4% in the CEE + HS condition (Fig. 3b). To assess the extent of myoblast fusion, we calculated the fusion index, which is defined as the proportion of nuclei within MYHC-positive myotubes. The fusion index was more than three times higher in the CEE + HS group (approximately 25%) compared with that in the CEE + FBS group (approximately 7%) (Fig. 3c). Additionally, CK activity was higher in the CEE + HS group than in the CEE + FBS group (Fig. 3d), further confirming that CEE + HS was more conducive to the differentiation of CMSCs into myotubes. We also examined additional myogenic differentiation markers, including MYOG, MYH1C, and MYH1E (Fig. 3e–g). While MYOG expression was similar across all groups, MYH1C and MYH1E were most highly expressed in the CEE + HS group. These results indicate that the CEE + HS condition was more effective than the CEE + FBS condition for the myogenic differentiation of CMSCs.

a Immunofluorescence images of MYHC in CMSCs. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and skeletal muscle differentiation marker MYHC (red). Scale bars, 50 μm. b Muscle cell differentiation was determined by calculating the % Area of MYHC using ImageJ (n = 3). c Muscle cell differentiation was determined by calculating the fusion index manually (n = 3). d Creatine Kinase (CK) activity in the CMSCs cultured under different conditions (n = 2). e–g Gene expression levels of MYOG, MYH1C, and MYH1E in CMSCs (n = 3). For (b–g), the significant difference between treatments was identified by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. The data are presented as mean ± SE. a-d Different letters represent statistically significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.01).

CEE + 3%HS-DM enhances CMSC differentiation and well-aligned myotube formation

Initially, six culture conditions (1%, 3%, 5% FBS and 1%, 3%, 5% HS without CEE) were compared based on morphology and differentiation marker expression (Supplementary Fig. 3). Among these, the 5% FBS-containing medium exhibited the highest level of myotube formation and differentiation marker expression (Supplementary Fig. 3a and 3b) and was therefore selected as the control differentiation medium (5% FBS-DM).

Next, we attempted to optimize differentiation conditions for CMSCs using CEE-containing medium. Since the CEE + HS condition supported robust proliferation (Fig. 2), we examined whether it could also promote differentiation. CMSCs cultured under this medium indeed formed myotubes (Fig. 3). Based on these results, we developed a differentiation medium consisting of 30% CEE and 3% HS (CEE + 3%HS-DM).

To induce differentiation, the basal medium was changed from DMEM/F12 to high-glucose DMEM and supplemented with insulin in both the 5% FBS-DM and CEE + 3%HS-DM groups. Insulin infusion has been shown to acutely increase the expression of key differentiation markers and to promote myotube hypertrophy and enhanced fusion in concert with Wnt signaling27,28,29. Based on these established effects, insulin was included in all differentiation conditions to support myogenic differentiation. For accurate comparison across groups, insulin was added uniformly, while only the concentrations of FBS and HS were varied, with all other conditions kept constant. CMSCs were first cultured in proliferation medium (15% FBS-containing medium) for three days to achieve 90–100% confluency, followed by five days of culture under two differentiation conditions: 5% FBS-DM and CEE + 3%HS-DM (Fig. 4a). Compared with 5% FBS-DM, CEE + 3%HS-DM promoted the formation of more and larger myotubes (Fig. 4b). Muscle differentiation markers were expressed at significantly higher levels in CEE + 3%HS-DM than in 5% FBS-DM (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, CEE + 3%HS-DM facilitated the formation of thicker myotubes and exhibited a significantly higher fusion index compared to 5% FBS-DM (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4d, e). Additionally, CEE + 3%HS-DM maintained a high level of CK activity throughout the differentiation period (Fig. 4f).

a Schematic of the CMSC differentiation experiment. b Morphological images of differentiated CMSCs in each group. Scale bars, 100 μm. c Gene expression levels of differentiation markers in CMSCs (n = 3). d Immunofluorescence images of MYHC in CMSCs. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and myotubes were stained with skeletal muscle differentiation marker MYHC (red). Scale bars, 50 μm. e The differentiation rate of CMSC was determined by calculating the fusion index manually (n = 5). f CK activity in the CMSCs by differentiation date cultured under different conditions (n = 2). g The OrientationJ-based directional analysis color survey indicates the direction of CMSCs cultured with 5% FBS-DM and CEE + 3%HS-DM at 5 days. Each color corresponds to a different alignment angle. Scale bars, 500 μm. The data shown in (c, e, f) are presented as mean ± SE. The asterisks represent statistically significant differences in expression levels (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Next, we examined the alignment of the differentiated myotubes, as muscle cells have the inherent ability to align during growth30,31. Cells cultured in 5% FBS-DM exhibited inconsistent alignment, whereas those in CEE + 3%HS-DM showed relatively unidirectional alignment (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 4). Taken together, these results indicate that CEE + 3%HS-DM enhances myotube formation, alignment, and overall differentiation of CMSCs.

CEE + 3%HS-DM enhances scaffold stability, cell viability, and myotube formation in a 3D culture system

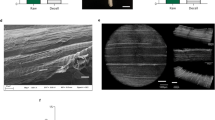

To investigate whether CEE + 3%HS-DM was also effective in 3D myotube formation, we compared its ability to promote myotube development using a 3D scaffold. For the 3D culture of CMSCs, we prepared plant-derived scaffolds from the decellularization of green onion, celery, perilla leaf, and spinach (Fig. 5a). The ultrastructure of the decellularized cellulose scaffolds revealed that the surface of the green onion scaffold exhibited a unidirectional texture, which was expected to facilitate the unidirectional alignment of the CMSCs (Fig. 5b). By contrast, the celery scaffold exhibited a porous structure with thin walls, whereas the perilla leaf and spinach scaffolds had rough surfaces with no distinct structural features other than pores, making them less suitable for promoting myotube alignment (Fig. 5b). Therefore, we seeded CMSCs onto a green onion scaffold and cultured them under both 5% FBS-DM and CEE + 3%HS-DM conditions to assess the feasibility of 3D culture. CMSCs cultured in 5% FBS-DM exhibited poor attachment to the scaffold, whereas those in CEE + 3%HS-DM showed significantly enhanced attachment and myotube formation (Fig. 5c). This was further supported by the scaffold weight changes before and after cell attachment (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Schematic of the plant-derived scaffold fabrication process. b FE-SEM images of plant-derived scaffolds. Scale bars, 100 μm. c FE-SEM images of the green onion scaffold seeded with CMSCs. Scale bars, 20 μm (above)/10 μm (below). d Live/dead staining images of CMSCs seeded on green onion scaffold. Representative images were selected from areas enriched with attached cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. e Representative immunofluorescence images of CMSCs seeded on green onion scaffold. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and myotubes were stained with phalloidin (green) and skeletal muscle differentiation marker MYHC (red). Scale bars, 25 μm.

Next, we evaluated the cell viability to compare the culture stability within the scaffolds. Cells cultured under 5% FBS-DM conditions exhibited higher cell death, whereas those in CEE + 3%HS-DM conditions showed minimal cell death, indicating improved stability under the CEE + 3%HS-DM conditions (Fig. 5d). MYHC and F-actin staining further confirmed that CMSCs attached more efficiently to the green onion scaffold under CEE + 3%HS-DM condition (Fig. 5e). These findings suggest that CEE + 3%HS-DM enhances cell attachment, viability, and myotube formation, providing a more favorable culture environment in a 3D system.

Discussion

In this study, we established optimal culture and differentiation conditions for CMSCs using CEE and HS as alternatives to FBS. CEE alone showed a significantly lower performance than the FBS-containing medium, but when combined with HS, it achieved comparable results. When CMSCs were treated with 30% CEE alone, the cell proliferation rate was approximately 50% of that observed in the control FBS-containing medium. Although various growth factors in CEE may have beneficial effects on cell proliferation12,23,32,33, the combination of CEE with FBS or HS resulted in a more significant increase in cell proliferation. FBS and HS contain key components, such as albumin, glucose, and calcium34, which are essential for cell survival and proliferation. Albumin activates the Akt signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in inhibiting apoptosis35. Glucose activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to promote cell survival and proliferation36,37. Additionally, an increase in the intracellular calcium concentration promotes cell cycle re-entry and enhances stem cell proliferation38. CEE alone may lack these essential components, which likely limits its ability to support cell proliferation as effectively as FBS- or HS-containing media. This limitation highlights the need for further research to analyze the composition of CEE and optimize the culture conditions to enhance its efficacy in promoting cell growth.

In addition to its effect on CMSC proliferation, CEE + HS enhanced myogenic differentiation. Therefore, the CEE + HS condition had a bivalent effect on CMSC culture, with two distinct effects on proliferation and differentiation. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a factor that exhibits a similar bivalent effect. Under typical cell culture conditions, IGF-1 induces proliferation during the first 24–36 h, followed by the promotion of myogenic differentiation39. IGF-1 plays a crucial role in skeletal muscle formation during chicken embryonic development by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, which enhances myoblast proliferation and initiates differentiation of muscle satellite cells40,41,42,43,44. In a previous report, CMSCs cultured in CEE-containing media exhibited an elongated morphology, indicative of differentiation, compared to those cultured in a medium containing FBS45. These findings suggest that CEE not only supports proliferation but also plays a significant role in enhancing differentiation. Notably, this study showed that the CEE + HS group had the highest levels of both CMSC proliferation and differentiation. HS derived from mature tissues appear to be more suitable differentiation inducers. Cysteine, suggested to be a component of HS but not detected in FBS34, has been shown in several studies to promote differentiation46,47,48. Additionally, reported that HS enhances the differentiation of mouse glial precursor cells more effectively than FBS. Collectively, these findings supported the hypothesis that HS promotes differentiation when combined with CEE.

Myoblast fusion is a critical process for muscle growth, regeneration, and repair and is essential for the formation of functional muscle fibers49,50. Compared with the 5% FBS-DM group, the CEE + 3%HS-DM group exhibited thicker myotubes, higher expression of myogenic differentiation markers, and significantly greater myoblast fusion. In addition, CK activity was significantly higher in the CEE + 3%HS-DM group, suggesting enhanced energy metabolism during muscle differentiation. CK is a key enzyme that converts creatine to phosphocreatine and acts as an energy reservoir for rapid ATP production in vertebrates. CK levels increase during skeletal muscle differentiation and are closely associated with the tissue creatine content and energy demand51,52,53. Thus, elevated CK activity is a reliable indicator of enhanced muscle differentiation. Furthermore, CMSCs cultured in CEE + 3%HS-DM exhibited unidirectional alignment, which is crucial for muscle differentiation. The unidirectional alignment of myofibers plays a vital role in the formation of functional muscle tissue54,55. CEE + 3%HS-DM conditions were also suitable for the attachment and differentiation of CMSCs in 3D cultures using plant scaffolds. During myogenesis, myoblasts align and fuse to form myotubes, subsequently arranging their internal cellular components into structured sarcomeres composed of MYHC and actin, which are crucial for coordinated muscle contraction and force generation30,31. To enhance the myoblast alignment and facilitate myotube formation, we used the linear cellulose structure of a green onion scaffold. CMSCs cultured in CEE + 3%HS-DM remained viable, adhered well to the green onion scaffolds, and successfully formed aligned myotubes. Plant-derived scaffolds are relatively easy to obtain, biocompatible, and cost-effective, making them highly suitable for cultured meat production56. Several studies have also explored the use of decellularized plant scaffolds for cellular agriculture. For example, Cheng et al.57 demonstrated that decellularized plant tissues supported myogenic cell alignment and differentiation, and Murugan et al.58 showed that a decellularized asparagus scaffold promoted proliferation and myogenic differentiation while replicating structural features of meat. However, adherence of animal cells to plant scaffolds is limited. This is because plant cells have a thick cellulose-based cell wall and lack extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as collagen and laminin, which are abundant in animal cells59. In animal cells, the RGD motif in ECM proteins plays a crucial role in facilitating cell adhesion by interacting with integrins60,61. This ECM-integrin interaction triggers the activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which promotes focal adhesion turnover and enables cells to firmly anchor themselves to specific locations within the tissues62. Additionally, PI3K/Akt activation supports the formation and remodeling of F-actin stress fibers63, which further activate the yes-associated protein (YAP)/transcriptional activator with the PDZ domain (TAZ) signaling pathway, contributing to cell adhesion and differentiation64,65.

Here, we demonstrated that CEE, derived from chick embryos and likely rich in ECM proteins66, enhanced CMSC adhesion to a plant-derived scaffold and promoted well-aligned myotube formation under CEE + 3%HS-DM conditions, despite both FBS and CEE being animal-derived components. Although CEE alone exhibits low efficiency, its combination with HS produces a synergistic effect that improves cell culture, differentiation, attachment, and myotube formation. During embryonic development, cell adhesion and migration are essential for tissue formation and are accompanied by abundant expression of ECM proteins66. Because CEE is extracted from chicken embryos, it likely contains high concentrations of ECM proteins, which may facilitate the secure attachment and alignment of muscle cells60,61,67. Thus, the abundant ECM proteins in the CEE may be considered key factors in promoting the alignment of myofibers differentiated from satellite cells. However, further studies are required to elucidate the precise underlying mechanisms. Collectively, this study demonstrated that CEE enhanced both the proliferation and differentiation of CMSCs while improving cell adhesion and differentiation on plant-derived scaffolds. We identified the CEE + HS condition as the most suitable for CMSC culture, as it effectively regulates both proliferation and differentiation. Notably, CEE + 3%HS-DM promoted the unidirectional alignment of myotubes, highlighting its potential for enhancing muscle tissue organization. These findings indicate that CEE has the potential to replace traditional serum components, facilitating large-scale proliferation and differentiation of CMSCs. However, as CEE alone did not achieve proliferation rates comparable to those observed with FBS, further research is necessary to optimize the culture conditions for improved efficiency. Additionally, the effectiveness of CEE + 3%HS-DM in enhancing cell adhesion and differentiation in 3D cultures underscores its potential application in 3D tissue engineering. The adoption of CEE in combination with HS as a replacement for FBS could open new possibilities for sustainable and scalable commercialization of cultured meat. However, being animal-derived, it still raises ethical concerns, consumer acceptance issues, and potential batch-to-batch variability. Serum-free and chemically defined media are being developed as fully animal-free alternatives68,69, but they remain costly and technically challenging. Importantly, CEE remains cost-competitive compared to FBS. Thus, CEE may serve as a practical strategy to reduce FBS dependency while complementing ongoing efforts toward sustainable, defined media. Further investigations into the underlying mechanisms and optimization strategies are crucial for advancing research in the cultured meat industry.

Methods

Isolation and culture of CMSCs

CMSCs were isolated from the leg muscles of E18 chicken fetuses (Ross 308). Briefly, muscle tissues were obtained from the thigh muscles of chicken fetuses. The collected muscle tissues were then transferred to a sterile Petri dish and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; LB004-02, Welgene, Korea) containing 10% penicillin-streptomycin (PS; 15140-122, Gibco, USA). In this step, non-muscle tissues, such as blood vessels, cartilage, and adipose tissue, were removed. The muscle tissues were minced with sharp scissors and digested in a solution containing 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (25200-072, Gibco, USA), 2 mg/mL Collagenase D (11088858001, Roche, Germany), and 1 U/mL Dispase II (4942078001, Roche, Germany) in DMEM/F12 (11320-033, Gibco, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C. After digestion, the mixture was filtered through 100 μm and 70 μm cell strainers, then neutralized with a medium containing DMEM/F12, 15% FBS (SH30919.03, HyClone, USA), and 1% PS. Following centrifugation at 1100 rpm for 5 min, ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysing buffer (A10492-01, Gibco, USA) was added to the pellet and incubated for 5 min at 4 °C.

The solution was neutralized using a neutralizing medium and centrifuged. The cell pellets were resuspended in a culture medium, which consisted of DMEM/F12 containing 15% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin glutamine (PSG; 10378-016, Gibco, USA), and 5 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 13256-029, Gibco, USA). The cells were then seeded into a gelatin-coated cell culture dish and incubated for 1 h in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation for 1 h, the satellite cells present in the supernatant were separated from the fibroblasts attached to the bottom of the cell culture dish, collected, and transferred to another culture dish. CMSCs were passaged every 3 days, and the exact passage day and split ratio were determined based on cell density. Passages 2–4 were used in the experiments. The cells were verified to be free from mycoplasma contamination using BioMycoX Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (D-25, CellSafe, Korea) (Fig. S6).

Preparation of CEE

CEE was prepared from E10 chicken embryos (Ross 308). Initially, the eggs were thoroughly cleaned with alcohol, and chicken embryos were carefully extracted. The embryos were washed three times using media consisting of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% PS. After washing, the embryos were disrupted using a 30 mL syringe and combined with an equal volume of media. The mixture was then stirred for 2 h and then immediately stored at −80 °C. For further processing, the sample was thawed and centrifuged at 3200 × g for 5 min to collect the supernatant. The supernatant was subsequently centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 1 h and stored at −80 °C until use. Approximately 4–5 mL of CEE is obtained from one E10 chicken embryo; therefore, ~60–70 eggs are required to prepare 1 L of medium containing 30% CEE. The preparation cost of CEE was approximately 180,000–200,000 KRW per 500 mL.

Establishing culture conditions for CMSCs

To evaluate the effects of CEE supplementation at varying concentrations of FBS and HS (16050-130, Gibco, USA) on CMSCs, we prepared 14 different culture conditions. These included combinations of 0%, 1%, 2%, and 3% FBS or HS added to media containing either 20% or 30% CEE.

Evaluation of cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (M6494, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 48 and 72 h. In brief, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4 × 103 cells per well and cultured for 48 and 72 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with MTT solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After incubation, the medium was removed, and dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well. Cells were gently pipetted to ensure thorough mixing, followed by incubation for 10 min at room temperature (RT). The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate absorbance spectrophotometer (1681150, Bio-Rad, USA).

Immunofluorescence

CMSCs were cultured on a glass bottom confocal dish (211350, SPL, Korea), and scaffolds were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the samples were permeabilized and blocked with a blocking solution consisting of 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at RT. The following primary antibodies and dilutions were used: anti-Pax7 (1:50 dilution; PAX7, DSHB, USA), anti-MYHC (1:50 dilution; MF20, DSHB, USA), Phalloidin (1:200 dilution; MAN0001777, Invitrogen, USA) at 4 °C overnight. Phalloidin was used to stain the actin filaments and confirm the presence of F-actin. After washing with a washing solution containing 0.3% Triton X-100, the primary antibodies were visualized using Alexa Fluor 488- or 568-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cell nuclei were stained with 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 5 min at RT. Fluorescence images were captured using a super-resolution confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 800, Carl Zeiss).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured CMSCs using the TRIzol reagent (15596026, Invitrogen, USA) according to the appropriate protocol with 1 × 106 cells. The RNA samples were then quantified using a Nanodrop spectrometer (13-400-518, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) based on the absorbance at 260 nm/280 nm. For cDNA library synthesis, 1 μg of the extracted RNA was used for reverse transcribed with SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (18080-044, Invitrogen, USA), 10 mM dNTP Mix (18427-013, Invitrogen, USA), and Oligo (dT) 12–18 Primer (18418-012, Invitrogen, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using TOPrealTM SYBR Green qPCR PreMIX (RT500M, Enzynomics, Korea), and the expression levels of target genes were analyzed using the LightCycler® PCR 96 Instrument (05815916001, Roche, Germany). GAPDH was used as an endogenous control to normalize gene expression. Primer sequences for the target genes used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Western blot

Total protein was isolated using RIPA buffer (RC2002-050-00, Biosesang, Korea) supplemented with protease inhibitor (A32953, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) from 3 × 106 cells. The protein concentration was determined using a DC Protein Assay Kit (5000112, Bio-Rad, USA). The proteins isolated from cells were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 12% acrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk in Tris buffer solution with 0.5% Tween-20 (TBST) at RT for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with secondary antibodies at RT for 1.5 h. The primary antibodies used were against GAPDH (1:5000 dilution; MA5-15738, Invitrogen, USA), Pax7 (1:1000 dilution; PAX7, DSHB, USA), and MyoD (1:1000 dilution; 18943-1-AP, Proteintech, USA). The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies used were goat anti-mouse IgG (31430, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (31460, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). All target protein levels were normalized to GAPDH, and protein bands were visualized using an ECL Kit (32106, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and captured using ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad, USA) and Image Lab software (Bio-Rad, USA).

Differentiation of CMSCs into myotube

CMSC differentiation was induced by replacing the culture medium with a differentiation medium when the cells reached 90–100% confluency. The differentiation medium for the control group (5% FBS-DM) consisted of DMEM/High glucose (SH30243.01, HyClone, USA) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% PSG, and 1 μg/mL insulin (I9278, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). For the experimental group (CEE + 3%HS-DM), the differentiation medium was composed of DMEM/High glucose containing 30% CEE, 3% HS, 1% PSG, and 1 μg/mL insulin. The cells were cultured for 5 days to undergo differentiation, and the medium was replaced daily.

Creatine kinase activity assay

To determine the creatine kinase (CK) activity in CMSCs following creatine treatment, a Creatine Kinase Activity Assay Kit (ab155901, Abcam, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative CK activity was calibrated based on the NADH standard curve.

Evaluation of cell alignment

Alignment was assessed 5 days after exposure to the differentiation media. Differentiated CMSCs were imaged using an inverted microscope (CKX41; Olympus, Japan). Using OrientationJ, we determined the alignment by analyzing the orientation of individual microfilaments within the image. Additionally, a color survey was generated for each image to facilitate the visualization of the microfilament orientation. The angular distribution of microfilaments was derived from this data. The OrientationJ plug-in was downloaded from http://bigwww.epfl.ch/demo/orientation/ for FIJI-ImageJ 1.8.0_17270,71.

Preparation of plant-derived scaffold

Four plant tissues (green onions, celery, spinach, and perilla leaves) were selected as potential scaffolds for CMSCs differentiation. The tissues were washed three times for 10 min each with distilled water and then cut into pieces. Next, the tissue pieces were treated with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 72 h, and the SDS solution was replaced every 24 h. This treatment was performed using an agitator to ensure the thorough penetration of the SDS solution. After 72 h of treatment, the tissues were washed three times with distilled water to remove SDS and shaken overnight. Subsequently, they were immersed in 70% ethanol and shaken for 48 h. After ethanol treatment, the tissues were washed three times with 3rd distilled water to completely remove any remaining ethanol. Finally, the decellularized tissue samples were stored at −80 °C and lyophilized overnight. Before use, the samples were stored at −20 °C.

Seeding CMSCs on a plant-derived scaffold

Uniformly sized scaffolds were created using sterilized scissors and placed on a 24-well plate. Subsequently, 1 mL of an anti-adherence rinsing solution (07010, STEMCELL Technologies, Canada) was added to each well of a 24-well plate and incubated at RT for 30 min. The scaffolds were placed on a plate. Afterward, 1 × 107 CMSCs were resuspended in a medium consisting of Matrigel (356230, Corning, USA) and proliferation medium at a 1:10 ratio, resulting in a 50 μL volume, and seeded onto the scaffold surface. PBS was added to the surrounding wells to prevent the scaffold from drying. After a 16 h cell seeding period, an additional 1 mL of proliferation medium was placed entirely submerged in the scaffold. After 24 h, the proliferation medium was replaced with a differentiation medium. The medium was replaced every 48 h for a period of 12–14 days.

To obtain a sample image, scaffolds were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 3-4 h at RT. Samples were then dehydrated in increasing ethanol concentrations (50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 99%) for 15 min each and left for 1–2 h at −20 °C and then overnight at −80 °C. The samples were then lyophilized and imaged using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; SU8010, Hitachi, Japan).

Viability assessment of seeded CMSCs on a scaffold

The scaffolds cultured in differentiation medium for 14 days were stained using a LIVE/DEAD™ Cell Imaging Kit (R37601, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Hydrolyzed compounds permeable to the cell membrane are converted to the fluorescent anion calcein, which enables the detection of live cells. Dead cells were identified using an ethidium homodimer, which stains cells that are impermeable to the dye because of compromised cell membranes. Images were obtained using an inverted microscope (CKX41, Olympus, Japan) equipped with a fluorescent lamp (U-RFL-T, Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., USA). Statistical differences were assessed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. The results are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical

All experimental and animal care procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Jeonbuk National University (NON2022-032-002), Republic of Korea. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of Jeonbuk National University and compliant with ARRIVE guidelines.

Data availability

We declare that all data relevant to this study are contained in this paper and its supplementary information.

References

Berners-Lee, M., Kennelly, C., Watson, R. & Hewitt, C. Current global food production is sufficient to meet human nutritional needs in 2050 provided there is radical societal adaptation. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 6, 52 (2018).

Post, M. J. Cultured meat from stem cells: challenges and prospects. Meat Sci. 92, 297–301 (2012).

Bhat, Z. F., Kumar, S. & Bhat, H. F. In vitro meat: a future animal-free harvest. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 782–789 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Surveillance of foodborne disease outbreaks in China, 2003–2017. Food Control 118, 107359 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Challenges and possibilities for bio-manufacturing cultured meat. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 97, 443–450 (2020).

Post, M. J. et al. Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nat. Food 1, 403–415 (2020).

Bhat, Z. F. & Fayaz, H. Prospectus of cultured meat—advancing meat alternatives. J. food Sci. Technol. 48, 125–140 (2011).

Post, M. J. Cultured beef: medical technology to produce food. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94, 1039–1041 (2014).

Chelladurai, K. S. et al. Alternative to FBS in animal cell culture—an overview and future perspective.Heliyon 7, e07686 (2021).

Hayashi, I. & Sato, G. H. Replacement of serum by hormones permits growth of cells in a defined medium. Nature 259, 132–134 (1976).

Van der Valk, J. et al. Optimization of chemically defined cell culture media–replacing fetal bovine serum in mammalian in vitro methods. Toxicol. Vitr. 24, 1053–1063 (2010).

Mulugeta, F. et al. Evaluation of chicken embryo extract and egg yolk extract as alternatives to basic cell culture medium supplement. BMC Res. Notes 17, 269 (2024).

Isobe, T. et al. Cryopreservation for bovine embryos in serum-free freezing medium containing silk protein sericin. Cryobiology 67, 184–187 (2013).

Wydooghe, E. et al. Replacing serum in culture medium with albumin and insulin, transferrin and selenium is the key to successful bovine embryo development in individual culture. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 26, 717–724 (2014).

Pazos, P. et al. Culturing of cells without serum: lessons learnt using molecules of plant origin. ALTEX-Altern. Anim. Exp. 21, 67–72 (2004).

Shefer, G., Van de Mark, D. P., Richardson, J. B. & Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Satellite-cell pool size does matter: defining the myogenic potency of aging skeletal muscle. Dev. Biol. 294, 50–66 (2006).

Danoviz, M. E. & Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells: background and methods for isolation and analysis in a primary culture system. In Myogenesis. Methods in Molecular Biology. (ed. DiMario, J.), Vol 798, 21–52 (Humana Press, 2012).

Shahini, A. et al. Efficient and high yield isolation of myoblasts from skeletal muscle. Stem Cell Res. 30, 122–129 (2018).

Oh, T. H. & Markelonis, G. J. Dependence of in vitro myogenesis on a trophic protein present in chicken embryo extract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77, 6922–6925 (1980).

Bałaban, J. et al. Effects of graphene oxide nanofilm and chicken embryo muscle extract on muscle progenitor cell differentiation and contraction. Molecules 25, 1991 (2020).

Hong, T. K. & Do, J. T. Generation of chicken contractile skeletal muscle structure using decellularized plant scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 3500–3512 (2024).

Jebessa, E. et al. Characterization of miRNA and their target gene during chicken embryo skeletal muscle development. Oncotarget 9, 17309 (2018).

Christman, S., Kong, B., Landry, M. & Foster, D. Chicken embryo extract mitigates growth and morphological changes in a spontaneously immortalized chicken embryo fibroblast cell line. Poult. Sci. 84, 1423–1431 (2005).

Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 9, 493 (1961).

Musarò, A. & Carosio, S. Isolation and culture of satellite cells from mouse skeletal muscle. In Adult Stem Cells. Methods in Molecular Biology. (eds. Di Nardo, P., Dhingra, S. & Singla, D.). Vol 1553, 155–167 (Humana Press, 2017).

Lee, J. E., Yoon, S. H., Shim, K. S. & Do, J. T. Regulatory landscapes of muscle satellite cells: from mechanism to application. Int. J. Stem Cells 18, 237–253 (2025).

Lee, E. J. et al. The role of insulin in the proliferation and differentiation of bovine muscle satellite (Stem) cells for cultured meat production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 4109 (2025).

Dhindsa, S. et al. Acute effects of insulin on skeletal muscle growth and differentiation genes in men with type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 181, K55–K59 (2019).

Rochat, A. et al. Insulin and wnt1 pathways cooperate to induce reserve cell activation in differentiation and myotube hypertrophy. Mol. Biol. cell 15, 4544–4555 (2004).

Chargé, S. B. & Rudnicki, M. A. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 84, 209–238 (2004).

Sanger, J. W., Wang, J., Fan, Y., White, J. & Sanger, J. M. Assembly and dynamics of myofibrils. BioMed Res. Int. 2010, 858606 (2010).

Jonchère, V. et al. Gene expression profiling to identify eggshell proteins involved in physical defense of the chicken egg. BMC Genom. 11, 1–19 (2010).

Pajtler, K. et al. Production of chick embryo extract for the cultivation of murine neural crest stem cells. JoVE 45, 2380 (2010).

Yun, S. H. et al. Analysis of commercial fetal bovine serum (FBS) and its substitutes in the development of cultured meat. Food Res. Int. 174, 113617 (2023).

Jones, D. T. et al. Albumin activates the AKT signaling pathway and protects B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells from chlorambucil-and radiation-induced apoptosis. Blood, J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 101, 3174–3180 (2003).

Yu, J. S. & Cui, W. Proliferation, survival and metabolism: the role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling in pluripotency and cell fate determination. Development 143, 3050–3060 (2016).

Zhou, Y. & Liu, F. Coordination of the AMPK, Akt, mTOR, and p53 pathways under glucose starvation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14945 (2022).

Amaya, M. J. et al. Role of calcium signaling in stem and cancer cell proliferation. In Trends in Stem Cell Proliferation and Cancer Research (eds. Resende, R. & Ulrich, H.) 93–137 (Springer, 2013).

Florini, J. R., Ewton, D. Z. & Coolican, S. A. Growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocr. Rev. 17, 481–517 (1996).

Yu, M. et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) promotes myoblast proliferation and skeletal muscle growth of embryonic chickens via the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 39, 910–922 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Effect of IGF1 on myogenic proliferation and differentiation of bovine skeletal muscle satellite cells through PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Genes 15, 1494 (2024).

Fu, S., Yin, L., Lin, X., Lu, J. & Wang, X. Effects of cyclic mechanical stretch on the proliferation of L6 myoblasts and its mechanisms: PI3K/Akt and MAPK signal pathways regulated by IGF-1 receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1649 (2018).

Ma, Y., Fu, S., Lu, L. & Wang, X. Role of androgen receptor on cyclic mechanical stretch-regulated proliferation of C2C12 myoblasts and its upstream signals: IGF-1-mediated PI3K/Akt and MAPKs pathways. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 450, 83–93 (2017).

Senesi, P., Luzi, L., Montesano, A., Mazzocchi, N. & Terruzzi, I. Betaine supplement enhances skeletal muscle differentiation in murine myoblasts via IGF-1 signaling activation. J. Transl. Med. 11, 1–12 (2013).

Schnorrer, F. & Dickson, B. J. Muscle building: mechanisms of myotube guidance and attachment site selection. Dev. Cell 7, 9–20 (2004).

Elkafrawy, H. et al. Extracellular cystine influences human preadipocyte differentiation and correlates with fat mass in healthy adults. Amino acids 53, 1623–1634 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. L-Cysteine promotes the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells via the CBS/H2S pathway. Neuroscience 237, 106–117 (2013).

Fedoroff, S. & Hall, C. Effect of horse serum on neural cell differentiation in tissue culture. vitro 15, 641–648 (1979).

Kuang, S., Kuroda, K., Le Grand, F. & Rudnicki, M. A. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell 129, 999–1010 (2007).

Abmayr, S. M. & Pavlath, G. K. Myoblast fusion: lessons from flies and mice. Development 139, 641–656 (2012).

Wyss, M. & Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 80, 1107–1213 (2000).

Jaynes, J. B., Johnson, J. E., Buskin, J. N., Gartside, C. L. & Hauschka, S. D. The muscle creatine kinase gene is regulated by multiple upstream elements, including a muscle-specific enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 62–70 (1988).

Han, Q. et al. Restoring cellular energetics promotes axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Metab. 31, 623–641.e628 (2020).

Jana, S., Leung, M., Chang, J. & Zhang, M. Effect of nano-and micro-scale topological features on alignment of muscle cells and commitment of myogenic differentiation. Biofabrication 6, 035012 (2014).

Kino-Oka, M. et al. Automating the expansion process of human skeletal muscle myoblasts with suppression of myotube formation. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 15, 717–728 (2009).

Hickey, R. J., Modulevsky, D. J., Cuerrier, C. M. & Pelling, A. E. Customizing the shape and microenvironment biochemistry of biocompatible macroscopic plant-derived cellulose scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 3726–3736 (2018).

Cheng, Y.-W., Shiwarski, D. J., Ball, R. L., Whitehead, K. A. & Feinberg, A. W. Engineering aligned skeletal muscle tissue using decellularized plant-derived scaffolds. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6, 3046–3054 (2020).

Murugan, P. et al. Decellularised plant scaffolds facilitate porcine skeletal muscle tissue engineering for cultivated meat biomanufacturing. npj Sci. Food 8, 25 (2024).

Seymour, G. B., Tucker, G. & Leach, L. A. Cell adhesion molecules in plants and animals. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 21, 123–132 (2004).

Pierschbacher, M. D. & Ruoslahti, E. Cell attachment activity of fibronectin can be duplicated by small synthetic fragments of the molecule. Nature 309, 30–33 (1984).

Pytela, R., Pierschbacher, M. D. & Ruoslahti, E. Identification and isolation of a 140 kd cell surface glycoprotein with properties expected of a fibronectin receptor. Cell 40, 191–198 (1985).

Fabry, B., Klemm, A. H., Kienle, S., Schäffer, T. E. & Goldmann, W. H. Focal adhesion kinase stabilizes the cytoskeleton. Biophys. J. 101, 2131–2138 (2011).

Qian, Y. et al. PI3K induced actin filament remodeling through Akt and p70S6K1: implication of essential role in cell migration. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 286, C153–C163 (2004).

Pocaterra, A. et al. Fascin1 empowers YAP mechanotransduction and promotes cholangiocarcinoma development. Commun. Biol. 4, 763 (2021).

Dupont, S. Role of YAP/TAZ in cell-matrix adhesion-mediated signalling and mechanotransduction. Exp. Cell Res. 343, 42–53 (2016).

Walma, D. A. C. & Yamada, K. M. The extracellular matrix in development. Development 147, dev175596 (2020).

Duffy, R. M., Sun, Y. & Feinberg, A. W. Understanding the role of ECM protein composition and geometric micropatterning for engineering human skeletal muscle. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 44, 2076–2089 (2016).

Stout, A. J. et al. Simple and effective serum-free medium for sustained expansion of bovine satellite cells for cell cultured meat. Commun. Biol. 5, 466 (2022).

Kolkmann, A. M., Van Essen, A., Post, M. J. & Moutsatsou, P. Development of a chemically defined medium for in vitro expansion of primary bovine satellite cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 895289 (2022).

Püspöki, Z., Storath, M., Sage, D. & Unser, M. Transforms and operators for directional bioimage analysis: a survey. In Focus on Bio-Image Informatics. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology. (eds. De Vos, W., Munck, S. & Timmermans, J. P.). Vol 219, 69–93 (Springer, 2016).

Rezakhaniha, R. et al. Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in the arterial adventitia using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 11, 461–473 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00208330 and RS-2024-00340604) and the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (IPET), funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (Grant No. 322006-05-04-CG000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K.: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization. Y.K. contributed as the first author of this study. J.L.: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Visualization. J.P.: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation. J.T.D.: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision. J.P. and J.T.D. contributed equally as co-corresponding authors of this study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, Y., Lee, J., Park, J. et al. Chick embryo extract-driven culture system enhances chicken muscle satellite cell differentiation and 3D myotube formation. npj Sci Food 9, 243 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00605-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00605-6