Abstract

Front-of-pack nutrition labels (FOPNL) like the Nutri-Score aim to guide healthier food choices, but their focus on limited nutritional parameters may overlook key health-promoting compounds. This study analyzed 54 commercial soluble cocoa powders from the Spanish market—covering 19 brands and Nutri-Score categories A to D—using untargeted metabolomics (HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS) and univariate and multivariate statistical analysis. PCA and PLS2 analyses showed no clear clustering by Nutri-Score categories, while ANOVA and post-hoc tests revealed limited metabolic differences, highlighting a mismatch between Nutri-Score classification and the actual chemical diversity of soluble cocoa products. Nutri-Score ratings primarily reflect macronutrient balance but fail to account for health-promoting metabolites. In several cases, products richer in bioactive compounds were penalized with lower Nutri-Scores, underscoring a limitation of this system when applied to complex food matrices. These findings highlight the need for more comprehensive labeling approaches that integrate metabolomic insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cocoa, derived from the fruit of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao), is processed into products such as cocoa paste, cocoa powder, and chocolate, which are widely consumed and highly valued. In Europe, per capita consumption of cocoa and its products reached 5 kg in 2022, with an expected annual growth rate of ~4.5% between 2023 and 2030 (https://bit.ly/3FM6TTx, accessed on August 2, 2025). In Spain, per capita consumption was 3.21 kilograms in 2023, with chocolate being the most consumed product (1.2 kg per person per year), followed by soluble cocoa (800 g per person per year) (https://bit.ly/4e0nwrh, accessed on August 2, 2025), representing 34% of total cocoa product consumption (https://bit.ly/3FM6TTx, accessed on August 2, 2025). Soluble cocoa or soluble cocoa powder, is a product made from cocoa powder treated with alkaline salts via alkalinization or “dutching” to improve solubility, darkens color, and reduces bitterness. Powdered cocoa should not exceed 25% by weight of cocoa powder in the dry mixture and must contain more than 20% by weight of cocoa butter. If it contains less than 20%, it must be labeled as “reduced-fat”. On the other hand, chocolate powder is a mixture of cocoa powder with sugars and/or sweeteners, containing at least 29% by weight of cocoa powder based on dry matter. This mixture may also include spices, flavorings and additives: salt (NaCl) like flavor enhancer, acidity regulators, anti-caking agents, bulking agent, emulsifiers, stabilizers, sweeteners, and thickeners1. Beyond taste, cocoa is recognized for health benefits including cardiovascular support, improved insulin sensitivity, anti-inflammatory effects, gut microbiota modulation, and cognitive enhancement, largely due to its polyphenols, particularly flavanols2. The European Commission, supported by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), has approved the health claim: “Cocoa flavanols help maintain the elasticity of blood vessels, which contributes to normal blood flow”3. Cocoa is especially rich in flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin, and procyanidins), with concentrations relatively high4, though phenolic content varies with origin, processing and product type5. Many cocoa derived foodstuffs contain added ingredients, such as sugars, flours, sweeteners, and salt, resulting in substantial variability in their nutritional profiles. For this reason, it is essential to implement labeling systems that help consumers identify and choose healthier cocoa-based foodstuffs.

To promote healthier eating habits and improve public health, governments worldwide have implemented various strategies, including front-of-pack nutrition labeling (FOPNLs). These labels are endorsed by both national and international public health organizations as effective tools for providing consumers with accessible and simplified nutritional information. FOPNLs serve as an incentive for food manufacturers to reformulate foodstuffs by reducing unhealthy ingredients, such as added sugars and salt. Among the most widely implemented FOPNL systems is the Nutri-Score, a color-coded label that assesses the overall nutritional quality of foodstuffs using a five-tier scale (from dark green to dark orange nearly red) accompanied by letters from A to E. Developed to help consumers make more informed and healthier food choices, the Nutri-Score also encourages manufacturers to improve the nutritional composition of their products to achieve a better rating6. The system assigns positive points (0 to 55) for nutrients of concern (energy, sugars, saturated fats, and salt) and negative points (−17 to 0) for beneficial components (fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, rapeseed, walnut and olive oil, fiber and proteins). The final score, ranging from -17 (healthiest) to 55 (least healthy), determines the product’s Nutri-Score classification (Fig. S1), which is also adjusted by food category (Table S1).

Although Nutri-Score has been adopted in several European Union countries, including France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, it faces opposition in countries like Italy and Poland7,8, and the European Commission may abandon mandatory implementation due to lack of consensus (https://bit.ly/45Gjli7, accessed on August 2, 2025). Critics highlight its scientific limitations, including insufficient differentiation of fat types9, disregard for health-promoting compounds, such as phenolic and neglect of food processing levels, which may favor reformulated, highly processed products over minimally processed, nutrient-dense foods. As a result, relying solely on Nutri-Score may not provide consumers with adequate for informed dietary choices10.

To address these concerns, metabolomics has emerged as a promising tool for analyzing food composition and identifying biomarkers of nutritional quality and authenticity. Using both targeted and untargeted approaches, and advanced techniques, such as mass spectrometry, it provides detailed profiles of macronutrients and small-molecule compounds, capturing the effects of composition, processing, and storage on foodstuffs characteristics and potential health benefits5,11,12. Thus, this research aims to evaluate the Nutri-Score system’s ability to classify soluble cocoa foodstuffs accurately, considering their nutritional and compositional complexities, and integrating metabolomic data with nutritional information to determine whether the system reflects compounds linked to health benefits.

Results

Soluble cocoa chemical profile

Before performing statistical analysis, the chemical profile of the soluble cocoa samples was explored using an automated MS/MS-based approach with MS2query. The predominant chemical super classes identified by the Natural Product Classifier (NPC) in both positive and negative ionization modes are shown in Fig. S2 (Supplementary information). Several chemical super classes were present in both modes with similar proportions, while, as expected, some were specific to one ionization mode. These super classes included small peptides, oligopeptides, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, glycerophospholipids, triterpenoids, tryptophan alkaloids, fatty acids and their conjugates, fatty amides, pseudoalkaloids, monoterpenoids, saccharides, coumarins, phenylpropanoids, phenylethanoids, nicotinic acid alkaloids, and sesquiterpenoids. A more detailed breakdown of the composition, highlighting the top NPC classes detected in each ionization mode, is provided in Fig. S3 (Supplementary information). The chemical space analysis confirmed that our analytical method effectively captured the complexity of the soluble cocoa samples.

Multivariate statistical analysis

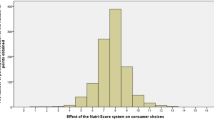

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Fig. 1) –integrating metabolomic data with nutritional properties: cocoa content, carbohydrates, fiber, sugars, protein, total fat, saturated fat, total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoids an antioxidant capacity–did now show clustering based on Nutri-Score categories.

The next step was to investigate the data using a supervised method. When optimizing components and variables to generate the partial least squares regression (PLS2) model, only one component was needed to separate samples. However, two components were included to provide two dimensions and facilitate the interpretation. Nevertheless, we focused on metabolites and variables of the first component. In this regard, 44 metabolites were selected from dataset X (“metabolites”), while only one variable was selected from dataset Y (“properties”), with “proteins” being the only variable in Y needed to differentiate the samples. However, a more complex model was applied, forcing the minimum number of variables in X to 15 and in Y to 4, aiming to explore the relationships between metabolites and cocoa nutritional and health properties. Finally, 33 variables from X and 10 from Y were included in the first component of the PLS2 model. To ensure robustness, a stability assessment of the selected variables was performed using 10-fold cross-validation with 100 repetitions. Only variables with stability values greater than 80% were retained in the model. These criteria support the reliability of the identified associations, even though predictive accuracy was not the focus of the analysis.

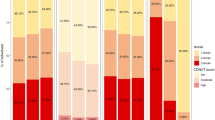

The scores plot from the final PLS2 is shown in Fig. 2. Samples did not cluster according to Nutri-Score categories, as some with Nutri-Score C grouped with those rated D or B. However, a clearer separation was observed based on cocoa content. Samples tended to cluster from right to left according to decreasing cocoa content.

In the loading plot (Fig. 3), variables, such as fats, saturated fats, proteins, fiber, TPC total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity were positioned on the right side of the plot. This distribution indicated that samples located on the right had a higher content of these compounds and a higher antioxidant capacity. In contrast, carbohydrates and sugars were located on the left side, indicating that samples in this region had higher contents of these nutrients. A detailed distribution of the samples according to their protein, fat, and sugar content is shown in Fig. S4 (Supplementary information), while comprehensive data on nutritional composition, antioxidant properties, and Nutri-Score classification are presented in Table S2 (Supplementary information).

F feature. Features are detailed in Table 1.

Additionally, the metabolites of the first component were also located on the right side of the plot, reflecting a positive correlation with fats, saturated fats, proteins, fiber, TPC, total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity. Accordingly, the samples situated in this area also exhibited a higher abundance of these metabolites. Additionally, the heatmap (Fig. 4) showed that the discriminant metabolites exhibited strong positive correlations with cocoa content, protein, TPC, fiber, total fat, and saturated fat. These metabolites were also positively associated with total flavonoids and antioxidant capacity. In contrast, they displayed negative correlations with carbohydrate and sugar content.

Tentative annotation or NPClassifier chemical classes of the discriminant metabolites are detailed in Table 1. The tentatively identified compounds included pyroglutamic acid, pyrocatechuic acid, N-acetylleucine, sorbitol, N-acetylphenylalanine, docosahexanoic acid (DHA), vanillic acid glucoside, FA 18:1 + 3 O, camptothecin, hexenyl primeveroside, and nicotinic acid. Additionally, other tentatively identified metabolites included representatives of hydroxy fatty acids, quinazoline alkaloids, branched-chain fatty acids, cinnamic acid derivatives, pregnane steroids, dipeptides, and flavonols.

An ANOVA test was conducted to evaluate whether the discriminant metabolites selected by the PLS2 model differed significantly among Nutri-Score categories. The results are presented in Table 2. Six metabolites showed significant differences, including F12 identified as sorbitol, and F33 classified within the chemical group of cinnamic acid and derivatives. Post-hoc Tukey analyses indicated that these differences occurred mainly between Nutri-Score B and categories C and D (Fig. S5).

Discussion

This is the first study to apply untargeted metabolomics to integrate metabolomic data into the evaluation of nutritional labeling systems. The findings suggest that the Nutri-Score system may not adequately capture the variability in metabolite composition and nutritional profiles across these foodstuffs. Notably, in the PCA combining metabolomic and nutritional data, as later corroborated in the PLS2 analysis, no clear clustering was observed according to Nutri-Score categories, indicating a potential mismatch between Nutri-Score classification and the actual chemical diversity of soluble cocoa products. Moreover, ANOVA and post-hoc tests revealed significant metabolic differences among Nutri-Score categories, further corroborating this mismatch.

While Nutri-Score has been praised for its superior performance compared to other FOPNL and its positive impact on healthier food choices, its limitations should not be underestimated. Notably, the system does not consider the presence of several nutrients and bioactive compounds, such as specific types of fiber, oxylipins, fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, anthocyanins, polyphenols, and other nutritionally relevant constituents, which are particularly relevant for assessing the nutritional quality of cocoa-derived products. Flavonoids, for instance, are abundant in cocoa and have been extensively linked to health benefits, such as antioxidant activity and protective effects on cardiovascular and cognitive health2,13. However, Nutri-Score does not account for these compounds in its algorithm. In contrast, other nutrient profiling systems, like the Food Compass Score (FCS), integrate a broader range of attributes—including phytochemicals (total flavonoids among them), sweeteners, processing level, and fat quality—providing a more comprehensive assessment of overall food healthfulness14. As a result, soluble cocoa foodstuffs with a high cocoa content, despite being rich in these beneficial components, may receive less favorable Nutri-Score ratings, often due to their fat content, overlooking their potential health-promoting benefits.

Specifically, among the discriminant metabolites identified between the different types of soluble cocoa foodstuffs, several small peptides stand out for their potential health effects. Pyroglutamic acid (Table 1, F4) has demonstrated neurological activity, including improvements in memory recall, learning and anxiety regulation. In rodent studies, it has also shown antidepressant and analgesic properties15. Another peptide, N-acetylleucine (Table 1, F11), has shown significant benefits in alleviating symptoms of ataxia in rare neurodegenerative disorders. Clinical trials report improvements in motor function, cognitive symptoms, and quality of life, along with statistically significant reductions in disease progression over both short- and long-term treatment periods16,17. Similarly, N-acetylphenylalanine (Table 1, F17) and some of its derivatives have shown promise in preclinical osteoarthritis research, both in vitro18 and in animal models19.

Regarding phenolic acids, pyrocatechuic acid (Table 1, F8), also known as 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid, has been shown to enhance antioxidant enzyme activity, reduce oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, and ameliorate hypertension and atherosclerosis by lowering inflammation in vitro models20. Although the health effects of vanillic acid glucoside (Table 1, F27) have not been directly studied, its related aglycone, vanillic acid, has demonstrated multiple beneficial effects in preclinical studies, particularly in metabolic and inflammatory conditions, as well as neuroprotection21,22. Luteolin-7-O-glucoside (Table 1, F53), a flavone, is also supported by preclinical evidence for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and tissue-repair activities23,24, although its efficacy may vary depending on biological context and disease target.

Camptothecin (Table 1, F32), by contrast, has been widely studied for its anticancer properties25. Nicotinic acid or niacin (Table 1, F79) offers well-documented health benefits, including improved lipid profiles, cardiovascular protection, and reduced risk of heart attack and stroke. It is also essential for cellular metabolism as a precursor to the coenzymes NAD and NADP, prevents pellagra, and shows potential neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects26.

Moreover, Nutri-Score does not consider the presence of sweeteners in solid foods (though it does in beverages), despite their long-term health effects remain poorly understood27. For instance, a sugar-free cocoa product that contains only 48% defatted cocoa (4.5% fat) along with maltodextrin, rice flour, resistant dextrin 10%, gluten-free barley malt extract, flavorings, sweeteners, emulsifier, anti-caking agent (E341), and salt (Table S3, M7) might receive a Nutri-Score A. In contrast, a 100% cocoa powder product made solely with cocoa and a natural acidity regulator (potassium carbonate) but a normal fat content (21% fat) (Table S3, M51), may receive a Nutri-Score C, despite containing no additional ingredients and offering greater nutritional density.

Another critical limitation of the Nutri-Score algorithm is its disregard for the degree of food processing. This is particularly relevant for cocoa-derived foodstuffs, where factors, such as fat content or added sugars can disproportionately influence ratings without reflecting the health benefits of bioactive compounds like flavanols. As a result, sugar-free cocoa foodstuffs containing sweeteners and a long list of ingredients may achieve a favorable Nutri-Score A, despite being highly processed. This discrepancy highlights the need for a more holistic evaluation of nutritional quality to ensure the Nutri-Score accurately guides consumers toward healthier choices.

Furthermore, Nutri-Score does not differentiate between vegetable and animal fats and penalizes products for their saturated fat content, energy, sugars, and salt. However, studies suggest that cocoa fats may provide protective effects against lipid accumulation and liver inflammation28. Despite these potential health benefits, Nutri-Score fails to account for the presence and role of beneficial fatty acids, even though fats are essential for physiological functions, including the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Notably, recent research has identified the presence of oxylipins—bioactive lipid mediators, such as phytoprostanes and phytofurans—in cocoa-based foodstuffs, particularly in dark chocolate. These plant-derived oxylipins are gaining attention for their immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties29. More broadly, oxylipins have been recognized for their bioactivity and potential nutritional significance when ingested through the diet30. As a consequence of these oversights, consumers may mistakenly perceive normal-fat cocoa as less healthy than their low-fat counterparts, despite the presence of health-promoting fatty acids and lipid mediators.

Specifically, within the lipid category, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (Table 1, F25) stands out as a critical nutrient with well-established benefits for brain, eye, cardiovascular, and metabolic health31. Although there are no specific studies on FA 18:1 + 3 O (Table 1, F29), the health-promoting effects of oleic acid (FA 18:1) are well-documented, particularly for cardiovascular and inflammatory health32. Nonetheless, the biological activity of FA 18:1 + 3 O may differ due to oxidative modifications and therefore should be evaluated independently.

Ultimately, overlooking these methodological limitations of Nutri-Score could lead to decreased consumption of foods that, despite receiving lower ratings, may represent valuable components of a balanced and nutritious diet, both from a nutritional and sensory perspective10. In contrast, more comprehensive profiling systems, such as the FCS incorporate a broader array of health-relevant factors, including nutrient ratios, processing level, specific lipids, phytochemicals like flavonoids and carotenoids, and even sweeteners, offering a more nuanced evaluation of food healthfulness14. In this context, metabolomics offers a powerful complementary approach to traditional nutrition labeling. By enabling the comprehensive identification and quantification of hundreds of small molecules, metabolomics allows for a more comprehensive characterization of food composition. This approach not only helps reveal bioactive components associated with health outcomes but also enhances our understanding of the effects of food processing, storage, and formulation on nutritional quality33,34.

Our findings demonstrate that current front-of-pack labeling systems, such as the Nutri-Score do not fully capture the nutritional complexity of foods with bioactive compounds, such as soluble cocoa powders. While Nutri-Score ratings primarily reflect macronutrient balance, they fail to recognize the presence of health-promoting metabolites, leading to inconsistencies between label category and actual nutritional potential. Products richer in bioactive compounds were often penalized with lower Nutri-Scores, underscoring a critical limitation of this system when applied to complex food matrices. These results highlight the need for more comprehensive labeling approaches that integrate metabolomic insights, thereby providing consumers and policymakers with a more accurate tool to guide healthier food choices.

Methods

Soluble cocoa samples

Fifty-four soluble cocoas were selected in 2022 based on the list of the best and worst soluble cocoas reported by the Organization of Consumers and Users (OCU) in Spain (http://bit.ly/4g6QAyz, accessed on August 2, 2025). All samples were purchased from eight different supermarkets in the Spanish market, representing 19 different brands and four distinct score Nutri-Score categories (A–D). Specifically, the study included 9 samples with Nutri-Score A, 7 with B, 22 with C and 16 with D (Table S2, S3). No sample with Nutri-Score category E was included because the list provided by OCU did not contain any cocoa products in this category and, furthermore, we have not found any soluble cocoa with that Nutri-Score in the Spanish market.

Sample preparation

Metabolites were extracted from cocoa powder using ultrasound-assisted extraction, as described by Razola-Díaz et al.35. In brief, cocoa samples were initially defatted with hexane (10 ml hexane per 1 g of cocoa powder), vortexed for 1 min, sonicated in an ultrasound bath (Bandelin, Sonorex, RK52, Berlin, Germany) for 5 min, centrifuged (OHAUS, FC5718R, Germany) at 9960 rcf for 5 min, and evaporated under nitrogen. The procedure was repeated twice.

The extraction was then performed by adding 5 ml of a mixture of acetone/water/acetic acid (70/29.5/0.5%, v/v/v), vortexing for 2 min, sonicating in an ultrasound bath at 35 kHz for 5 min, and centrifuging at 9960 rcf for 5 min. Supernatants were collected, filtered through regenerated cellulose filters (0.2 μm, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and stored at −18 °C until further analysis. Equal aliquots (10 µl) of each cocoa extract were pooled to prepare a quality control (QC) sample, which was used to monitor the analytical performance.

Analysis of TPC, total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity

The TPC of cocoa samples was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method36 in 96-well microplates. Briefly, 600 μL of distilled water, 10 μL of sample, and 50 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent were added to each well. After 10 min, the mixture was homogenized, followed by the addition of 150 μL of 20% Na₂CO₃ and the volume was made up to 1 mL with water. Plates were incubated in the dark for two hours, and absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a Synergy Mx Monochromator-Based Multi-Mode Microplate reader, by Bio-Tek Instruments (Winooski, VT, USA). TPC was calculated from a gallic acid calibration curve. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

Total flavonoid content was measured using the aluminum chloride colorimetric modifying assay of Rodríguez-Pérez et al. (2016)36. Briefly, 100 μL of sample, 140 μL of methanol, and 60 μL of aluminum chloride solution were added to each well. The reaction was incubated in the dark for 30 min, after which absorbance was measured at 425 nm using the microplate reader described above. Total flavonoid content was calculated from a quercetin calibration curve. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mg quercetin equivalents (QE).

The antioxidant capacity was measured using the DPPH radical scavenging assay, previously applied by the authors36. In brief, 20 μL of each extract at varying concentrations. were added to 980 μL of a DPPH solution (50 μmol/L). The mixtures were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, 200 μL of each mixture was transferred to a microplate well, and absorbance was recorded at 516 nm. A calibration curve was constructed to determine the residual DPPH concentration in each well, and the percentage of remaining DPPH was plotted against extract concentration to calculate the EC50 value, defined as the amount of extract required to reduce the initial DPPH concentration by 50%. All measurements were performed in triplicate. Since lower EC₅₀ values indicate higher antioxidant capacity, the results were multiplied by –1 for consistency, so that higher values correspond to stronger antioxidant activity.

Untargeted-based metabolomics using HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS

Untargeted metabolomic analysis was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-TOF-MS). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a BRUKER AUTOFLEX TOF mass spectrometer operated in reverse-phase mode (RP). The column used was an ACQUITY UPLC BEH Shield RP18 (1.7 μm, 2,1 × 100 mm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA).

The mobile phases used were methanol (solvent A) and acidified water with 1% acetic acid (solvent B). A linear gradient elution program was applied over a total run time of 25 min. The gradient started at 5% A and 95% B, reaching 35% A and 65% B in 15 minutes. At minute 18, the mobile phase reached 100% A, which was maintained until minute 20. The system was then re-equilibrated to initial conditions (5% A, 95% B) by minute 21 and held until minute 25.

Chromatographic conditions included a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min and a column temperature of 40 °C. Mass spectrometry was performed with electrospray ionization (ESI) operated in both positive and negative modes. Calibration of exact mass was performed automatically using sodium formate, which was injected the beginning of each injection to ensure the mass accuracy required for compound identification. Detection was carried out considering a mass range of 50–1300 m/z and using a capillary voltage of + 4500 V, a dry gas temperature of 220 °C, a dry gas flow of 9.0 L/min, a nebulizer pressure of 3.0 bar, and spectra rate of 10 Hz. Moreover, automatic MS/MS experiments were performed using nitrogen as the collision gas, with the collision energy adjusted to 7 eV.

Processing of metabolomics data

Raw data files were converted to the open format (*.mzML) using MSConvert (v.3.0.24214-8766070)37 and subsequently deconvoluted. Data was processed following a previously published workflow38. MS-DIAL (v.4.9.221218)39 was used to extract retention times (RT), m/z values, and peak areas, applying specific parameters (Table S4).

To correct for signal intensity drift, the data was normalized using the Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) function based on QC sample intensities distributed throughout the analytical run. QC values were smoothed using a single-degree least squares fit, and resulting coefficients were interpolated with a cubic spline. The dataset was then aligned to the corrected results39.

Normalized datasets were further processed using the R-based package “notame”40. Filters were applied to remove background ion drift, low-detection features (QC limit = 0.8, group limit = 0.8) and low-quality features. Data normalization was performed using probabilistic quotient normalization (PQN), which first involves integral normalization and then scaling the test spectrum by dividing all variables by the median quotient of each variable relative to the reference spectrum (typically the median of control samples)41. Additionally, the metabolite peak areas were normalized using pinobanksin, which was added to all samples as an internal standard.

Statistical analysis: multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was conducted using the R-based package “mixOmics”. Pareto scaling was applied to the dataset, followed by PCA for unsupervised analysis. PCA integrated metabolomic data (positive and negative ionization modes) together with nutritional properties (cocoa content, carbohydrates, fiber, sugars, protein, total fat, saturated fat, TPC, total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity). The properties included in the analysis were those available on product labeling, along with additional indicators particularly relevant for cocoa products, namely antioxidant capacity, TPC, and total flavonoids. Partial least squares regression (PLS2) was then employed to identify relationships between data matrices X—corresponding to metabolites (positive and negative ionization modes)—and Y—corresponding to nutritional properties (cocoa content, carbohydrates, fiber, sugars, protein, total fat, saturated fat, TPC, total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity). PLS2 is a supervised multivariate method, particularly useful in metabolomics as it can handle collinear and noisy variables while providing intuitive graphical representations for model interpretation42. In this study, PLS2 was applied in an exploratory manner to examine associations between metabolomic features and nutritional properties, rather than for predictive purposes.

Annotation

Annotation of discriminant variables from the PLS2 model was performed by comparing data against the curated MS-DIAL library (updated on August 8th, 2024) for both positive and negative ionization modes. MS2query (v.1.4.0)43 was employed to identify analogs and classify compounds using NPClassifier44. Identifications with scores above 0.6 were considered for level 3 annotation, in line with metabolomics guidelines45.

A molecular network (MN) was constructed using the Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) workflow46 on GNPS (https://gnps.ucsd.edu, accessed on August 2, 2025)47. MS-DIAL-processed data were exported to GNPS, and MNs were generated. Data was filtered by removing all MS/MS fragment ions within +/− 17 Da of the precursor m/z. MS/MS spectra were window filtered by choosing only the top 6 fragment ions in the ± 50 Da window throughout the spectrum. The precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 0.05 Da and the MS/MS fragment ion tolerance to 0.05 Da. A MN was then created where edges were filtered to have a cosine score above 0.70 and more than six matched peaks. Further, edges between two nodes were kept in the network if and only if each of the nodes appeared in each other’s respective top ten most similar nodes. Finally, the maximum size of a molecular family was set to 100, and the lowest scoring edges were removed from molecular families until the molecular family size was below this threshold. The spectra in the network were then searched against GNPS spectral libraries47,48. The library spectra were filtered in the same manner as the input data. All matches kept between network spectra and library spectra were required to have a score above 0.7 and at least six matched peaks. The DEREPLICATOR was used to annotate MS/MS spectra49. Additional edges generated in MS-DIAL were supplemented into the MN.

Both datasets were cross-referenced to enrich the MN using Cytoscape (v.3.10.2)50. Related compounds were linked based on the similarities in their MS/MS spectra, and results were visualized as MNs, supporting the annotation process.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the findings of this study, ensuring the replicability of all analyses and visualizations presented in the study, are publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1593021951. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. All input data are open access. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and No 1925/2006 and repealing several Directives and Regulations. Off. J. Eur. Union L304, 18–63 EU (2011).

Palma-Morales, M., Melgar-Locatelli, S., Castilla-Ortega, E. & Rodríguez-Pérez, C. How healthy is it to fortify cocoa-based products with cocoa flavanols? A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 12, 1376 (2023).

European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/539 of 31 March 2015 authorising a health claim made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health, and amending Regulation (EU) Off. J. Eur. Union L90, 22–24 (2015).

Ried, K., Fakler, P. & Stocks, N. P. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008893.pub3 (2017).

Palma-Morales, M., Rangel-Huerta, O. D., Díaz, C., Castilla-Ortega, E. & Rodríguez-Pérez, C. Integration of network-based approaches for assessing variations in metabolic profiles of alkalized and non-alkalized commercial cocoa powders. Food Chem.: X 23, 101651 (2024).

Merz, B. et al. Nutri-Score 2023 update. Nat. Food 5, 102–110 (2024).

Peters, S. & Verhagen, H. Publication bias and nutri-score: a complete literature review of the substantiation of the effectiveness of the front-of-pack logo nutri-score. PharmaNutrition 27, 100380 (2024).

Panczyk, M. et al. Food front-of-pack labelling and the nutri-score nutrition label-poland-wide cross-sectional expert opinion study. Foods 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12122346 (2023).

Julia, C. et al. Discriminating nutritional quality of foods using the 5-Color nutrition label in the French food market: consistency with nutritional recommendations. Nutr. J. 14, 100 (2015).

Włodarek, D. & Dobrowolski, H. Fantastic foods and where to find them—advantages and disadvantages of nutri-score in the search for healthier food. Nutrients 14, 4843 (2022).

Bozza, D. et al. Untargeted metabolomics approaches for the characterization of cereals and their derived products by means of liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. Open 6, 100168 (2024).

Mialon, N., Roig, B., Capodanno, E. & Cadiere, A. Untargeted metabolomic approaches in food authenticity: a review that showcases biomarkers. Food Chem. 398, 133856 (2023).

Martin, M. Á & Ramos, S. Impact of cocoa flavanols on human health. Food Chem. Toxicol. 151, 112121 (2021).

Mozaffarian, D. et al. Food compass is a nutrient profiling system using expanded characteristics for assessing healthfulness of foods. Nat. Food 2, 809–818 (2021).

Mutlu, O. et al. Effects of pyroglutamyl peptides on depression, anxiety and analgesia in mice. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 10, 56–62 (2021).

Bremova-Ertl, T., Fields, T., Factor, M., Martakis, K. & Strupp, M. Results of a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial with N-acetyl-L-leucine for niemann-pick disease type C (PL5.001). Neurology 102, 3585 (2024).

Kaya, E. et al. Acetyl-leucine slows disease progression in lysosomal storage disorders. Brain Commun. 3, fcaa148 (2021).

Pagani, S. et al. The N-Acetyl phenylalanine glucosamine derivative attenuates the inflammatory/catabolic environment in a chondrocyte-synoviocyte co-culture system. Sci. Rep. 9, 13603 (2019).

Glasson, S. S., Blanchet, T. J. & Morris, E. A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 1061–1069 (2007).

Juurlink, B. H. J., Azouz, H. J., Aldalati, A. M. Z., AlTinawi, B. M. H. & Ganguly, P. Hydroxybenzoic acid isomers and the cardiovascular system. Nutr. J. 13, 63 (2014).

Magiera, A., Kołodziejczyk-Czepas, J. & Olszewska, M. A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of vanillic acid in human plasma, human neutrophils, and non-cellular models in vitro. Molecules 30, 467 (2025).

Ghaderi, S. et al. Underlying mechanisms behind the neuroprotective effect of vanillic acid against diabetes-associated cognitive decline: An in vivo study in a rat model. Phytother. Res. 38, 1262–1277 (2024).

Rehfeldt, S. C. et al. Neuroprotective effect of luteolin-7-o-glucoside against 6-OHDA-induced damage in undifferentiated and RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2914 (2022).

De Stefano, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory and proliferative properties of luteolin-7-o-glucoside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1321 (2021).

Li, F., Jiang, T., Li, Q. & Ling, X. Camptothecin (CPT) and its derivatives are known to target topoisomerase I (Top1) as their mechanism of action: did we miss something in CPT analogue molecular targets for treating human disease such as cancer? Am. J. Cancer Res. 7, 2350–2394 (2017).

Lin, L. et al. Association of dietary niacin intake with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2018. Sci. Rep. 14, 28313 (2024).

Fidler Mis, N. et al. Sugar in infants, children and adolescents: a position paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 65, 681–696 (2017).

Chang, H.-Y. et al. The preliminary results for evaluating cocoa butter’s hepatoprotective effects against lipid accumulation and inflammation in adult male rats chronically fed ethanol. Bioengineering 9, 526 (2022).

León-Perez, D. et al. Bioactive plant oxylipins-based lipidomics in eighty worldwide commercial dark chocolates: effect of cocoa and fatty acid composition on their dietary burden. Microchem. J. 157, 105083 (2020).

Rao, D. & Wu, S. Food oxylipins: Formation, distribution, analysis and implications for health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 159, 104968 (2025).

Li, J., Pora, B. L. R., Dong, K. & Hasjim, J. Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid and its bioavailability: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 9, 5229–5243 (2021).

Sales-Campos, H., Souza, P. R., Peghini, B. C., da Silva, J. S. & Cardoso, C. R. An overview of the modulatory effects of oleic acid in health and disease. Mini Rev. Med Chem. 13, 201–210 (2013).

Wu, W. et al. Emerging applications of metabolomics in food science and future trends. Food Chem. X 16, 100500 (2022).

García-Cañas, V. & Simó, C. In Reference Module in Food Science (Elsevier, 2019).

Razola-Díaz, M. D. et al. Exploring the nutritional composition and bioactive compounds in different cocoa powders. Antioxidants 12, 716 (2023).

Rodríguez-Pérez, C. et al. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction and pressurized liquid extraction of phenlic compounds from Moringa oleifera leaves by multiresponse surface methodology. Electrophoresis 37, 1938–1946 (2016).

Kessner, D., Chambers, M., Burke, R., Agus, D. & Mallick, P. ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 24, 2534–2536 (2008).

Rangel-Huerta, O. D. et al. Metabolomics workflow for quality control of differently-processed pre-cooked chicken fillets. Food Chem. 370, 131006 (2022).

Tsugawa, H. et al. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 12, 523–526 (2015).

Klåvus, A. et al. “notame”: Workflow for Non-Targeted LC-MS Metabolic Profiling. Metabolites 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10040135 (2020).

Dieterle, F., Ross, A., Schlotterbeck, G. & Senn, H. Probabilistic Quotient Normalization as Robust Method to Account for Dilution of Complex Biological Mixtures. Application in 1H NMR Metabonomics. Anal. Chem. 78, 4281–4290 (2006).

Stocchero, M. et al. PLS2 in Metabolomics. Metabolites 9, 51 (2019).

de Jonge, N. F. et al. MS2Query: reliable and scalable MS2 mass spectra-based analogue search. Nat. Commun. 14, 1752 (2023).

Kim, H. W. et al. NPClassifier: a deep neural network-based structural classification tool for natural products. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2795–2807 (2021).

Sumner, L. W. et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 3, 211–221 (2007).

Nothias, L.-F. et al. Feature-based molecular networking in the GNPS analysis environment. Nat. Methods 17, 905–908 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with global natural products social molecular networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 828–837 (2016).

Horai, H. et al. MassBank: a public repository for sharing mass spectral data for life sciences. J. Mass Spectrom. 45, 703–714 (2010).

Mohimani, H. et al. Dereplication of microbial metabolites through database search of mass spectra. Nat. Commun. 9, 4035 (2018).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Palma-Morales, M., Rangel-Huerta, O. & Rodríguez-Pérez, C. Untargeted metabolomics approaches challenge the Nutri-Score FOPNL system in soluble cocoa products dataset. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15930219 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This paper and the results presented constitute part of Marta Palma Morales’ doctoral thesis, which is performed as part of the Nutrition and Food Science Doctorate Program of the University of Granada. She was supported by a contract to the Junta de Andalucía-Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación Research Project: P21_00777 (April 2023–January 2024), and a research fellowship from the Government of Spain (FPU22/02472). We would like to ackowledge SpectraMinds for its support in the data analysis. Oscar Daniel Rangel-Huerta is founder of SpectraMinds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P.M., O.D.H. and C.R.P. conceptualized the study. M.P.M conducted the statistical analysis, with secondary review from O.R.H. M.P.M drafted the manuscript, and O.D.H., R.U. and C.R.P. critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. M.P.M., O.D.H., R.U. and C.R.P. supervised the body of work. Funding C.R.P. All authors read the final paper and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Palma-Morales, M., Rangel-Huerta, O.D., Urrialde, R. et al. Untargeted metabolomics approaches challenge the nutri-score FOPNL system in soluble cocoa products. npj Sci Food 10, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00649-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00649-8